Background: Cyanothece produces H2 catalyzed by hydrogenase or nitrogenase.

Results: Photo-H2 is nitrogenase mediated (via PSI) with reductant originating from catabolism and ATP from photophosphorylation.

Conclusion: Forcing additional ATP production by inhibiting NDH-2 increases the photo-H2 production rate at the expense of dark-H2.

Significance: Pathways for accelerating generation of ATP and reductant are identified as targets for further optimization of H2 yield by Cyanothece.

Keywords: Bioenergy, Biofuel, Cyanobacteria, Hydrogenase, NADH, Nitrogenase, Cyanothece, NADH Dehydrogenase, Infrared Illumination, Photo-H2

Abstract

Current biotechnological interest in nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria stems from their robust respiration and capacity to produce hydrogen. Here we quantify both dark- and light-induced H2 effluxes by Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 and establish their respective origins. Dark, anoxic H2 production occurs via hydrogenase utilizing reductant from glycolytic catabolism of carbohydrates (autofermentation). Photo-H2 is shown to occur via nitrogenase and requires illumination of PSI, whereas production of O2 by co-illumination of PSII is inhibitory to nitrogenase above a threshold pO2. Carbohydrate also serves as the major source of reductant for the PSI pathway mediated via nonphotochemical reduction of the plastoquinone pool by NADH dehydrogenases type-1 and type-2 (NDH-1 and NDH-2). Redirection of this reductant flux exclusively through the proton-coupled NDH-1 by inhibition of NDH-2 with flavone increases the photo-H2 production rate by 2-fold (at the expense of the dark-H2 rate), due to production of additional ATP (via the proton gradient). Comparison of photobiological hydrogen rates, yields, and energy conversion efficiencies reveals opportunities for improvement.

Introduction

The biotechnological potential of photobiological hydrogen production by cyanobacteria and algae to renewable fuel production has not yet been realized. However, experimental and theoretical investigations of the maximum attainable rates (1), advances in culturing methods (2, 3), enzyme manipulation (4, 5), and metabolic engineering in model strains (6–8) have provided insight into the fundamental mechanisms and revealed new opportunities and limitations.

Biological hydrogen production can be mediated by either of two broad classes of enzymes, the hydrogenases or the nitrogenases (8–10). Both classes are O2 sensitive, requiring anoxic environments to function maximally (11). Here we shall describe the hydrogen metabolism by Cyanothece, a genus of unicellular, aerobic, nitrogen-fixing (diazotrophic) cyanobacteria. Unlike the heterocyst-forming diazotrophic cyanobacteria (e.g. Nostoc and Anabaena spp.) that spatially separate oxygen-evolving photosynthesis from oxygen-sensitive nitrogen fixation (11), Cyanothece performs strictly regulated temporal separation of photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation (12). This temporal separation ensures that an intracellular anoxic environment conducive to nitrogenase activity is maintained. Deactivation of photosynthesis and an increased cellular respiration are thought to maintain this anoxia (12–14), regulated by an intrinsic circadian rhythm (15, 16), as even nongrowing (stationary phase) cells exhibit this cycling (15, 17). Specifically, it has been shown in Cyanothece ATCC 51142 that one of the 4 copies of psbA, the gene encoding the D1 subunit of Photosystem II, is highly up-regulated throughout the dark phase of the circadian cycle. This isoform of D1 (psbA4) varies significantly from the isoforms expressed during the light phase, especially at the C-terminal residues involved in binding the manganese cluster and allowing O2 evolution (18). It is hypothesized that expression of this isoform and incorporation of the translated D1 protein into the reaction center would lead to a photosystem II (PSII)2 core incapable of evolving O2. Expression of this isoform during the dark phase would allow the cell to retain a viable PSII quaternary framework so that an active D1 can quickly be re-incorporated during the subsequent light phase. Illumination of Cyanothece while this inactive D1 was expressed could afford photobiological H2 production by enzymes normally sensitive to O2. A homolog of this isoform (psbA4) was found in the draft genome of the Cyanothece strain studied herein.

The enzymatic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia in Cyanothece is catalyzed by a molybdenum nitrogenase, the most common and most efficient of the nitrogenase classes. Molybdenum nitrogenase (nitrogenase hereafter) requires 16 ATP and 8 electrons per N2 fixed, with 2 of these electrons diverted to the obligate reduction of H+ to H2. The observed ratio of proton reduction to nitrogen reduction by this class of enzyme is at least 25% (from the reaction stoichiometry) and at maximum 100% (in the absence of N2, where the nitrogenase functions like an ATP-powered hydrogenase, requiring 4 ATP per H2 produced) (7–8). Of note, the alternative nitrogenases (V-nitrogenase and Fe-nitrogenase) found in some strains naturally favor a higher ratio of proton reduction to nitrogen reduction. Cyanothece species accumulate carbohydrate, primarily in the form of glycogen granules, during the day and subsequently degrade this carbohydrate at night to provide the energy and reductant for nitrogenase function and O2 respiration (19). This natural diurnal cycling, efficient conversion of intracellular carbohydrate to energy, efficient respiration and intracellular anoxia, and presence of both classes of hydrogen producing enzymes makes the Cyanothece species among the best candidates for H2 production (20, 21).

Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 is a marine strain that has been reported to possess both the bidirectional hydrogenase (class 3d, bidirectional NAD-linked H2ase) and nitrogenase, but lacks the membrane bound respiratory or “uptake” hydrogenase (class 2a, cyanobacterial uptake hydrogenase) (22), typically found expressed alongside nitrogenase (23). We have, however, identified the complete gene coding for the “uptake” hydrogenase in the strain and have observed its transcription under both photoautotrophic and autofermentative conditions.3 We can therefore assert that all three hydrogen metabolizing enzymes found in cyanobacteria are present in this strain.

NADH and reduced ferredoxin are direct substrates for bidirectional hydrogenases and nitrogenases, respectively, as established by in vitro assays of enzymes from multiple microorganisms (24, 25). The NADH-dependent reduction of H+ to H2 by hydrogenase is often cited as thermodynamically unfavorable, as the standard potential at pH 7 for NAD+/NADH is −320 mV, compared with −420 mV for H+/H2. However, standard conditions refer to 1 bar H2 pressure, conditions that are never found in biological cells. By contrast, the calculated thermodynamic redox potential for H+/H2 is nearly identical to that of NAD+/NADH in a 0.1% H2 atmosphere (1000 ppm or 0.001 bar) (26). Consequently, pyridine nucleotides can serve as efficient reductant sources under biological conditions, especially when H2 backpressure is minimized. In addition to NADH and reduced ferredoxin, NADPH can be utilized indirectly, either by the reduction of NADH catalyzed by the pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase (if expressed and active), or by the reduction of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool via NAD(P)H dehydrogenase and subsequent reduction of ferredoxin through excitation of PSI (Scheme 1).

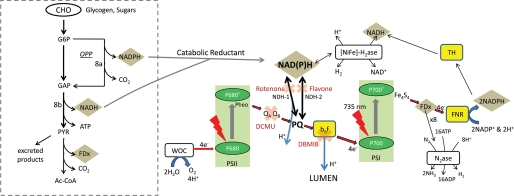

SCHEME 1.

Proposed model for coupling of carbohydrate catabolism to photo-H2 production in Cyanothece where nonphotochemical reduction of PQ by catabolically derived NAD(P)H is the primary source of reductant for PSI-dependent, nitrogenase-mediated photo-H2. Sites of proton pumping coupled to ATP generation are denoted by blue arrows, and sites of inhibitor action are denoted with a red X. An abbreviated scheme of carbohydrate catabolism showing the reduction of NADH by glycolysis and the reduction of NADPH by the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (OPP) is shown in the inset at left. Stoichiometries are not included. Abbreviations: CHO, carbohydrates; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde phosphate; PYR, pyruvate; Ac-CoA, acetyl coenzyme-A; QA and QB, PSII-bound plastoquinone molecules; PQ, the pool of membrane soluble plastoquinones; b6f, cytochrome b6f, FNR, ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase; N2ase, nitrogenase; TH, pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase; [NiFe]-H2ase, bidirectional hydrogenase.

Cyanobacteria are known to possess two NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (NDH) enzymes to exchange reductant between NAD(P)H and the lipid-soluble PQ pool (27–29). NDH type-1 is homologous to Complex I of the respiratory chain of mitochondria and bacteria (the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase). Interestingly, however, of the 14 minimal subunits that form the complex in Escherichia coli, only 11 are found in the genomes of cyanobacteria. The missing subunits (genes nuoE, nuoF, and nuoG) encode the NADH dehydrogenase module, which in E. coli functions as the energy input device, and consequently the mechanism by which cyanobacteria use NAD(P)H via this enzyme is still unknown (30). Experimental evidence has verified that NADPH and NADH can both be oxidized by the complex in purified cyanobacterial membranes (29) and a variety of mechanisms for electron donation to the complex have been supposed; this remains an open question (30). NDH type-1 (NDH-1) is capable of oxidizing both NADH and NADPH and (of importance to the present study) translocates (pumps) protons upon each reducing equivalent (NAD(P)H) exchanged. NDH type-2 is comprised of a single subunit, does not pump protons, and can only oxidize NADH.

The contribution of dark (autofermentative) hydrogen production arising from either hydrogenase- or nitrogenase-mediated pathways has been largely ignored in cyanobacteria. We show herein that hydrogen production in Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 can be of the dark, autofermentative type (primarily via hydrogenase), as well as light induced (via nitrogenase). By utilizing monochromatic excitation sources and detection of dissolved hydrogen, we monitor the kinetics of hydrogen evolution from both light and dark pathways within the same experimental incubation, thus allowing visualization of the independent responses of each pathway (light and dark) to applied stresses. We show that both intracellular reductant and ATP availability are limiting factors for maximal photo-H2 production, and that by increasing reductant availability via dark anaerobic incubation, or by channeling the flow of reductant through one of the specific NADH dehydrogenases to increase ATP availability, we can substantially increase the rate of photo-H2 production.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Growth of Culture

Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 was obtained from the University of Hawaii Culture Collection, where it was maintained as Synechococcus sp. Miami BG 043511 (many Cyanothece species were originally misclassified as Synechococcus (31)). Cultures were grown in ASP2 medium (32) without combined inorganic nitrogen at 30 °C under diurnal conditions (12 h light, 12 h dark) with a light intensity of ∼30 μE s−1 m−2. Cultures were not bubbled with any gases nor shaken.

Dissolved H2 Rate Electrode and Light Emitting Diode Illumination System

The first generation of our home-built H2 microcell is described elsewhere (33). Our second (current) generation electrochemical microcell is also a reverse Clark-type electrode for measuring dissolved H2 concentration (see supplemental “Materials and Methods”). This 2nd generation microcell has an increased sensitivity of ∼2 × 10−9 Coulomb H2, fast response time (100 ms), and microvolume sample chamber (6.5 μl). During measurement, H2 is constantly consumed by oxidation at a Pt/Ir electrode, allowing the instantaneous rate of H2 production to be measured. The microcell responds linearly to H2 and performs for several months using an oversized Ag/AgCl reference electrode (∼0.5 g AgCl) to consume the H+ product of H2 oxidation. In this article, the H2 production rate is presented as the current (nA) arising from the oxidation of dissolved H2. H2 yield was determined by integration with respect to time to yield electrical charge, which was converted to moles of H2 by the second law of Faraday. The microcell is equipped with light emitting diodes (LEDs) at wavelengths of 670 ± 10 and 735 ± 10 nm (FWHM), for exciting both Photosystems (670 nm) or PSI only (735 nm), respectively. The photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) intensity (400–700 nm) of the 670 nm LED at the sample is 1,010 μE and only 2.8 μE for the 735-nm LED. As a result, minimal excitation of PSII from the spectral tail of the 735-nm LED occurs, as confirmed by electrochemical O2 measurements in another Clark-type cell.

Culture Incubation

Stationary phase cells were taken from photoautotrophic growth conditions between 10 and 11 h after onset of the light cycle (circadian “dawn”), concentrated (40-fold) by centrifugation, re-suspended in fresh media, and placed in the 6.5-μl sample chamber of the electrochemical cell. When biochemical inhibitors were added to the cultures, this was done 5 min prior to the concentration and incubation on the hydrogen rate electrode. Inhibitor stocks were made with water or dimethyl sulfoxide as solvent, not ethanol (exogenous ethanol may serve as a reductant source). The cell was covered by a quartz disc and removed from light, where cellular respiration created anoxia within a matter of seconds. Dissolved H2 was continuously consumed as described above. When pulsed illumination was supplied to the culture, it was done using repeated pulses of 10-s duration, separated by 90 s dark time, i.e. 10% duty cycle.

Turbidity and Dry Weight Measurements

Cell density was measured as turbidity by absorbance at 730 nm. Optical densities were measured spectrophotometrically on a Thermo Scientific Evolution 60 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Dry weights of cells were taken by filtering cells through Whatman GF/C glass microfiber filters (1.4 μm pore size) and drying the filters in an 80 °C oven for 24 h.

RESULTS

Differential Excitation and Inhibition of Photosystems I and II

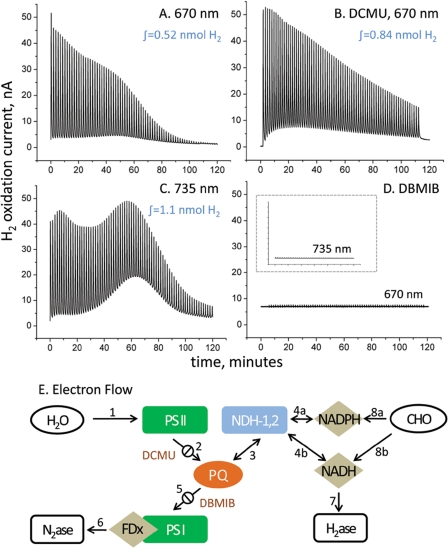

The selective excitation of PSI (denoted 735-photo-H2) and PSII + PSI together (denoted 670-photo-H2) is shown in Fig. 1. Cells were first subjected to 12 h of complete darkness and anoxia prior to the 120 min of pulsed illumination shown. The sharp rise in H2 oxidation current corresponds to the 10 s of illumination during each 100-s light-dark cycle (repeated 72 times). When both photosystems are excited by 670 nm light (Fig. 1A), the H2 production arising from each successive flash gradually decreases, completely ceasing after ∼100 min. H2 production also gradually decreases but more slowly both when near-infrared 735 nm light (Fig. 1C) is used (which only excites PSI) and when PSII is chemically inhibited (Fig. 1B) with DCMU (3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea). DCMU acts as a quinone analog, which binds to the QB pocket of PSII and blocks the transfer of electrons from QA (Scheme 1). The decrease in the absence of O2 production must therefore be due to the depletion of accessible intracellular reductant, which is common to all three conditions. The faster decay seen with light that excites both PSI + PSII is expected due to the O2 sensitivity of nitrogenase, and increases throughout the duration of the photoperiod, consistent with an intracellular buildup of O2 from PSII. 2,5-Dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl p-benzoquinone blocks the plastoquinone binding site on cytochrome b6f and therefore prevents the flow of electrons into PSI. When cells were treated with 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl p-benzoquinone (Fig. 1D) and illuminated with light, photoinduced H2 production is completely eliminated, indicating that the photo-H2 signal is completely dependent on electron transfer through PSI. This illustrates that photo-H2 is entirely nitrogenase mediated, as we would still expect to see 670-photo-H2 via PSII (steps 1 → 2 → 3 → 4b → 7 in Fig. 1E) in the presence of 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl p-benzoquinone if hydrogenase were mediating the process, as PQH2 oxidation by reverse electron flow through the NADH dehydrogenases is likely to occur (34, 35). Furthermore, the fact that H2 yield does not decrease when PSII is inhibited (in fact, the average yield increases 2.35-fold ± 0.75 with DCMU and 2.5-fold ± 1.3 with 735 nm illumination, based on triplicate measurements) indicates that reductant from intracellular catabolism (glycogen) rather than water serves as the immediate electron source for photo-H2 in this strain (steps 8 → 4 → 3 → 5 → 6).

FIGURE 1.

Immediate source of reductant for photo-H2 production in Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 is glycogen. A, red light (λ = 670 nm) excites both PSII and PSI, whereas (C) near-infrared light (NIR, λ = 735 nm) excites PSI only and has no direct effect on PSII. B, DCMU (10 μm) inhibits PSII by blocking reduction of QB. An increase in photo-H2 is observed both when red light is supplied to the culture in the presence of DCMU 2.35-fold ± 0.75 (S.D.) and when NIR light is used for illumination 2.49-fold ± 1.3 (S.D.) due to diminished O2 poisoning from elimination of PSII-dependent O2 evolution. D, 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl p-benzoquinone (DBMIB) (40 μm) blocks transfer of electrons from reduced PQ to PSI, which blocks the nitrogenase-mediated pathway (PSI dependent), but would not prevent H2ase-mediated photo-H2 production via PSII (1 → 2 → 3 → 4b → 7). The lack of photo-H2 with this treatment indicates a photo-H2 pathway entirely mediated by nitrogenase, whereas the low level dark-H2 current is due to hydrogenase. E, a minimal model for photo-H2 production shows possible routes for electron flow to nitrogenase and hydrogenase with reductant originating from the reduced PQ pool (formed from H2O via visible light and PSII) or glycogen (via NADH dehydrogenase). In both cases NIR light and PSI are required to transfer electrons to the level of reduced ferredoxin (substrate for nitrogenase) to observe photo-H2. Hydrogenase-mediated H2 production may occur in the dark via NADH formed via carbohydrate catabolism (8b → 7). H2 electrode calibration: 100 nA = 14.3 μmol of H2 g dry weight−1 h−1.

Interestingly, the fact that we do observe photo-H2 when 670 nm light is used confirms that Cyanothece strains are capable of maintaining lower levels of intracellular O2 during the dark phase of their circadian cycle. This may be due to higher levels of respiration by this strain (although this would “steal” electrons that could reduce protons to H2), or the incorporation of an inactive D1 protein into PSII during dark periods (as described under Introduction). Alternatively, the possibility also exists that the nitrogenase found in Cyanothece exhibits a higher tolerance for O2 and that it is this quality that allows it to produce H2 in response to visible light.

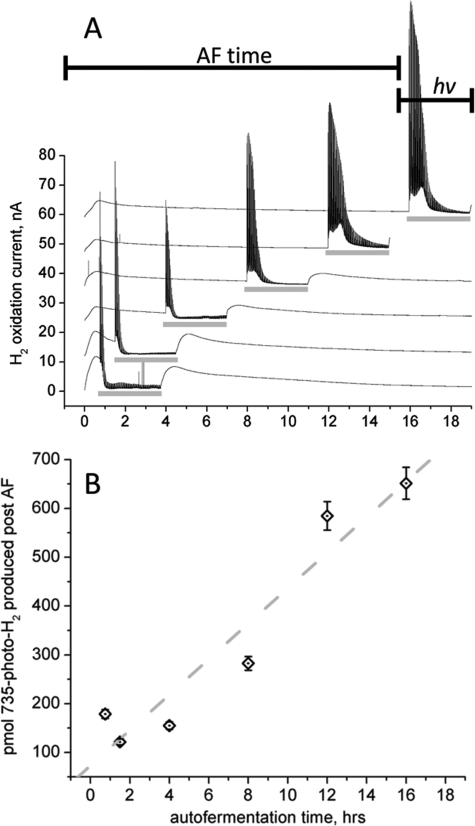

Increased Dark Preincubation Leads to Increased Photo-H2

Fig. 2 illustrates the effect of the dark, anaerobic preincubation period on 735-photo-H2. As above, cells were taken from photoautotrophic growth and placed in the sample chamber of the electrochemical cell. Dark periods (autofermentation) of 0.75, 1.5, 4, 8, 12, and 16 h were allowed before the cells were exposed to 3 h of pulsed illumination with 735-nm light. Fig. 2A shows the rate of H2 production measured for each of these experiments, and Fig. 2B illustrates the yield of 735-photo-H2 produced (as picomoles H2) during each 3-h illumination window. (The integral of the hydrogen production rate is only taken over the 3-h period of illumination.) With increasing dark time supplied to the cells before illumination, the yield of 735-photo-H2 over this fixed 3-h period continuously increases as a linear function of dark time up to 16 h. From the linear regression fit shown in Fig. 2B, the yield of 735-photo-H2 increases by 8.4-fold from time 0 to 16 h. This result shows that during the autofermentation period prior to illumination, intracellular reductant accumulates, presumably by the degradation of glycogen to mono- and disaccharides, the immediate glycolytic precursors, which is subsequently funneled to proton reduction during illumination. Indeed we have directly observed an increase in redox poise of the cells throughout the autofermentative conditions (supplemental Fig. S4). To investigate the effect of biochemical inhibitors on both photo- and dark-H2 production, an experimental design consisting of four periods of pulsed illumination each separated by 4-h dark time was instituted (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of dark, preincubation time (autofermentation, AF) on photo-H2 capacity. Cells were taken from photoautotrophic growth and placed under dark, anaerobic conditions for lengths of time ranging from 0.75 to 16 h before the onset of a 3-h period of pulsed illumination (735 nm LED, represented by the horizontal gray bars). Dissolved H2 was measured as current arising from the oxidation of the dissolved H2. The rate (A) of hydrogen evolution and cumulative yield (B) of 735-photo-H2 arising from the pulsed illumination window are shown. Error bars indicate 5% variability in H2 yield. The horizontal black bars (AF time and hv) represent the time segments for the top trace only (16 h dark). hv, light.

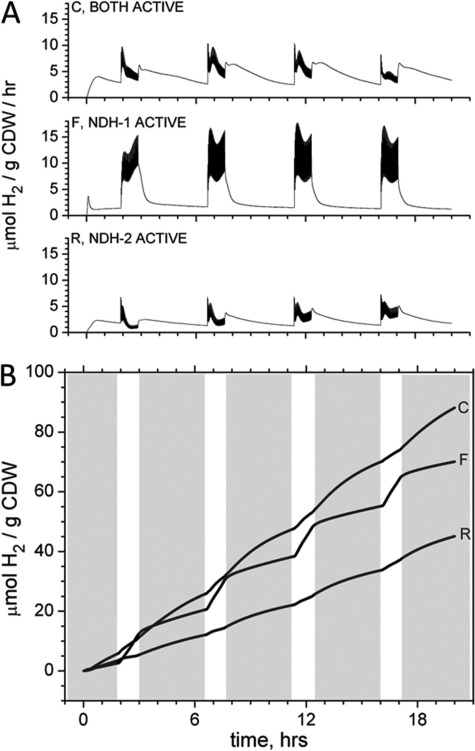

Inhibition of the NADH Dehydrogenases (Types 1 and 2)

Fig. 3 illustrates the effect on the hydrogen production rate (A) and yield (B) when catabolically derived reductant is funneled to PQ reduction through each of the specific NADH dehydrogenases found in the strain. Fig. 3A shows the rate of hydrogen production of (i) control cells, where both enzymes are active, (ii) cells treated with 50 μm flavone, where only NDH-1 is active, and (iii) cells treated with 20 μm rotenone, where only NDH-2 is active. Each condition was subjected to a 20-h incubation with four pulse trains of saturating light at 735 nm (supplemental Fig. S2). The average 735-photo-H2 production rate when cells were treated with flavone was 16.4 μmol of H2 g dry weight−1 h−1, or 2-fold higher than the control rate. This increase occurs at the expense of a 2.5-fold lower dark-H2 production rate. These effects are evident in Fig. 3B, where the cumulative yield of H2 (both dark and light) is plotted as a function of time. These data reveal that the carbohydrate pool, which serves as precursor to cellular reductant for conversion to H2, is shared between the photo-H2 and dark-H2 pathways, as the increased photo-H2 is coupled to a decline in the dark-H2 rate, a redirection of reductant between the pathways.

FIGURE 3.

The effect on H2 production of selective inhibitors of the two NADH dehydrogenases. A, the rate of dissolved H2 production was measured continuously from cells where both NADH dehydrogenases were functional (CTRL, C), where only NDH type-1 was active (50 μm flavone, F), and where only NDH type-2 was active (20 μm rotenone, R). B, the cumulative yield of dark- and photo-H2 evolution is shown, with the four 1-h photoincubation periods (735-photo) indicated by vertical white rectangles. The light-saturated maximal rate of photo-H2 production (extracted from the four photoincubation periods) was observed when only NDH type-1 was active, and was quantified as 16.4 μmol of H2 g of dry weight−1 h−1. This rate increase of 2-fold (compared with the control) was at the expense of a dark-H2 production rate ∼2.5-fold slower. This indicates a shared pool of reductant for both pathways (light and dark).

We also point out the decrease in dark-H2 production in Fig. 3 common to treatment with both flavone and rotenone. Because the rate of glycolysis is regulated by the cellular energy charge (ATP availability) as well as the NADH/NAD+ poise, it is reasonable to expect inhibitors that affect proton pumping and equilibration of the intracellular reductant pools to have upstream effects on glycolysis. The overall decrease in dark-H2 production common to both inhibitors may well be due to a down-regulation of glycolysis in response to increased NAD(P)H, which cannot reduce the plastoquinone pool due to the action of these inhibitors. There also may be some net flux of reductant out of the PQ pool (PQH2 to NADH) leading to dark-H2 production in the native system. When NDH-2 is inhibited with flavone, this reaction would have to proceed via NDH-1 (requiring ATP) and become unfavorable. We believe this explains the observation of decreased dark-H2 prior to the first illumination period with flavone treatment.

In flavone-treated cells, the light saturated rate of 735-photo-H2 production starts to decline after 60 min of pulsed illumination and drops to 50% of the initial rate after ∼2–3 h. This decrease in rate is common to control cells without flavone treatment as well, and is presumably due to the depletion of substrate for nitrogenase (reductant, protons, or ATP). Interestingly, in a similar experiment composed of a 20-h anoxic incubation of a 5-ml sample in sealed glass vials under continuous saturating white light illumination (1.81 milliwatt cm−2 s−1), only 15.7% of the total intracellular carbohydrate was depleted over the 20-h incubation (same experiment length as rate data presented here). Therefore, there exists significant room to improve the light saturated 735-photo-H2 rate, if the dark catabolic rate and subsequent generation of NADH could be enhanced.

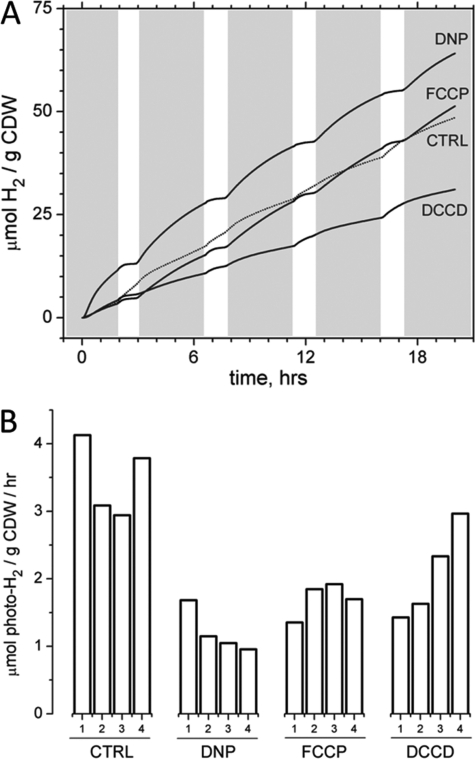

Decreased Capacity for ATP Phosphorylation

Two well documented protonophores were used to collapse the proton gradient and uncouple photophosphorylation from photosynthetic electron transfer. Both 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) and carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) are ionophores that shuttle protons across biological membranes and were used to collapse the proton-motive force responsible for generation of ATP via the F1F0 complex (36). Additionally, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD) was employed to directly inhibit ATP synthesis by blocking the flow of protons through the F0 channel and subsequently prevent phosphorylation of ADP by the F1 complex (37). The disruption of ATP synthesis and its effect on cellular energy charge by each of these inhibitors is shown in Fig. 4. Fig. 4A illustrates the cumulative yield of H2 produced by the cells (both dark-H2 and photo-H2) as a function of time (the white areas indicate the four 60-min pulsed illumination periods, as before). Both FCCP (5 μm) and DNP (50 μm) increase the dark-H2 rate. This increase is attributed to an increased rate of carbohydrate catabolism to compensate for the loss of ATP and collapse of the proton gradient caused by the protonophores. The bidirectional hydrogenase is the expected enzymatic outlet for this increase in dark-H2 via NADH oxidation. By contrast, both protonophores decrease the photo-H2 production rate; the rate approaches 0 at the end of each 1-h pulse train. This decrease is attributed to the loss of ATP production by photophosphorylation, which is essential for nitrogenase-dependent photo-H2 production. This decrease is illustrated as well in Fig. 4B, in which the average photo-H2 rates during the 1-h illumination periods for each of the four pulse trains are shown. All three inhibitors initially decrease the observable photo-H2 by more than 50% (illumination period number 1). Although FCCP and DNP retain their inhibition activity, the inhibition effect of DCCD decreases successively with each subsequent pulse train. Because DCCD is a cross-linker that physically binds to the F0 channel, we hypothesize that the cell can effectively sequester the DCCD by this binding activity. Therefore, by synthesizing more F0 channels, the cell can recover from this initial inhibition. Because DNP and FCCP do not bind to proteins like DCCD does, the cell cannot sequester them, and their capacity for inhibition remains unchanged with time.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of inhibiting membrane-coupled ATP generation on H2 production. Both FCCP (5 μm) and DNP (50 μm) are protonophores (uncouplers of the proton gradient); DCCD (250 μm) blocks proton flow through the F0 channel of ATPase. All three of these inhibitors prevent the potential energy stored in the proton-motive force from being translated into chemical energy as ATP. The cumulative yields of H2 production (A) and individual photo-H2 production rates from the four pulsed illumination windows (B) are shown. Although the cells treated with DNP and FCCP show inhibited photo-H2 capacity, their dark-H2 production rate is increased, consistent with increased glycolytic flux to compensate for stress introduced by the uncouplers.

DISCUSSION

By designing an experimental method that exposes Cyanothece to segments of both illumination and darkness during a single anoxic incubation, our electrochemical H2 sensor can observe (with high kinetic resolution) the response of both H2 producing enzymes to environmental and biochemical stresses and thereby allows the current mechanistic study. As such we are able to determine the relative contributions from hydrogenase and nitrogenase toward light- and dark-H2 production, identify shared pools for both processes, and indicate factors limiting the yield of each.

The complete elimination of photo-H2 production when 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl p-benzoquinone (DBMIB) is added to the sample (inhibiting electron flow through Photosystem I) can be attributed to loss of ATP generation from cyclic electron flow (photophosphorylation) and/or elimination of the production of reduced ferredoxin, based on the known outcome under aerobic conditions (36). Both are obligate substrates for nitrogenase, and the complete elimination of photo-H2 under these conditions indicates that the sole enzyme responsible for photoinduced H2 production in Cyanothece is nitrogenase. Our data illustrate an increased capacity for photo-H2 production with increasing dark preincubation, independent of PSII-dependent water oxidation. This result indicates the tight coupling of photo-H2 to the dark, anaerobic metabolism, where substrate builds up and becomes kinetically more accessible as anaerobic conditions progress. This increased availability of reductant translates into a greater photo-H2 production rate once the pulsed illumination commences. ATP levels fall during dark anoxia (38) and thus only accumulation of reductant can be responsible for this increase due to dark time.

Scheme 1 presents a minimal diagram of reductant and ATP generation to guide interpretation and assignment of the pathways. Under dark anoxia, cells catabolize their glycogen and sugar reserves to produce glucose 6-phosphate, which enters either glycolysis or the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway to produce NADH or NADPH, respectively. Subsequent oxidation of pyruvate by pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase generates reduced ferredoxin in the dark (pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase is the primary source of reduced ferredoxin during dark, anaerobic, and anabolic nitrogen fixation for unicellular nitrogen fixers (8)). NAD(P)H has a reducing potential of −320 mV, substantially less than that of ferredoxin at −415 mV. As the latter is the obligate electron donor for nitrogenase-dependent H2 production, NAD(P)H can only convert into reduced ferredoxin through either (a) being energized by PSI and light, or (b) interconversion by ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase in the dark, a thermodynamically uphill reaction that requires buildup of NAD(P)H. Our results demonstrate the predominance of the former pathway, where catabolically generated NAD(P)H exchanges hydride (reductant) with the PQ pool via either of two NADPH dehydrogenases. This hydride is energized to the level of reduced ferredoxin and free proton (coupled to ATP generation) by photoexcitation of PSI and made available for nitrogenase. This sudden shift in equilibrium between NAD(P)H and reduced ferredoxin and ATP manifests as the sharp increase in hydrogen evolution observed upon illumination.

Hydride exchange from NAD(P)H to the plastoquinone pool can occur in cyanobacteria by either of two NADH dehydrogenases present in the organism: NDH type-1 and NDH type-2. As mentioned earlier, NDH-1 translocates a proton from the stroma to lumen as it reduces plastoquinone (Scheme 1) and thus contributes to the intracellular proton gradient. NDH-2 lacks this ability. The channeling of all hydride flux from NAD(P)H to PQ through NDH-1 (rather than both NDH-1 and NDH-2) would provide the most ATP generation per hydride equivalent exchanged (by the proton pumping of NDH-1) and best accommodate the high ATP demand of nitrogenase. In the case of cells treated with flavone, we indeed see this effect. The maximal sustained (2.5 h) rate of hydrogen production in Cyanothece sp. Miami BG 043511 observed in these experiments was 16.4 μmol of H2 g dry weight−1 h−1 (15.8 ml of H2 liter−1 h−1) with flavone. To ensure that the increase in 735-photo-H2 was not due to an increase in the plastoquinone concentration (arising from regulatory effects of NDH-1 or NDH-2), we measured the PQ pool size and confirmed that it did not change following treatment with either flavone or rotenone (supplemental Fig. S3).

Our findings reveal that of the two factors limiting the rate of nitrogenase mediated 735-photo-H2, reductant limitation is stronger than ATP limitation under most physiological conditions, as evidenced by the increase in 735-photo-H2 production rates with increasing prior dark time where reductant accumulates (supplemental Fig. S4), and by the decrease in H2 production rate as the illumination period exhausts the available pool. Only when cells have ample reductant available is an ATP limitation observed, leading to the observed increase in 735-photo-H2 when reductant flux is forced through NDH-1. Further evidence of reductant limitation as the most severe limitation is that photo-H2 production increases in the presence of exogenous reduced carbon (3.3-fold increase when 685 mm glycerol was added to cells). Our H2 production rate of unsupplemented stationary phase cells is 1.64 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1. Based on carbohydrate degradation and hydrogen production yields after 20 h, our numbers correspond to a 24% energy conversion efficiency of carbohydrate to hydrogen from the strain.

Higher rates have been reported by Borodin and colleagues (21) for the same strain grown in a photobioreactor where actively growing cells were held at a chlorophyll concentration of ∼4 μg/ml (6.3 ml of H2 liter−1 h−1, or calculated to 70 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1). More recently, extremely high rates of 373 and 465 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1 (the latter when supplemented with 50 mm glycerol) have been reported for Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142 (39). If confirmed, these would set a new benchmark, as they are significantly higher than the maximum rates published to date for both heterocystous diazotrophs (167.6 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1 for Anabaena variabilis sp. ATCC 29413 PK84 mutant) (40) and for strains that produce H2 via the bidirectional hydrogenase only (3.1 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1 for Arthrospira maxima (41)). However, our own attempt to replicate the glycerol rate data using the ATCC 51142 strain have yet to confirm these results, and the reported rates exceed the maximum theoretical rate of nitrogenase-mediated H2 production of 40 μmol of H2 mg of Chl−1 h−1 as calculated by Bothe et al. (8) based on maximal carbon fixation rates of roughly 100 μmol mg of Chl−1 h−1 and a C/N ratio of 6 in cyanobacteria.

It is interesting to note that whereas the addition of the protonophores decreases the yield of photo-H2, they substantially increase the dark-H2 production yield. This confirms that the two mechanisms of hydrogen production (light and dark) are catalyzed by different enzymes that respond differently to cellular energy stress. Although the decreased photophosphorylation with membrane uncouplers in the light serves to limit nitrogenase of its key energy source (ATP), under dark conditions this disruption stimulates the cell to accelerate the rate of carbohydrate catabolism and thus increase ATP generation by substrate level phosphorylation (glycolysis) (Scheme 1, step 8b). Faster carbohydrate catabolism under anoxia increases the ratio of NADH:NAD+ within the cell, which the bidirectional hydrogenase serves to alleviate by reducing protons to H2 and regenerating NAD+ (6). The analogous response of increased fermentative hydrogen production in the presence of FCCP was seen in Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 (42) and in the nonphotosynthetic bacterium E. coli when ATP levels were decreased by the introduction of futile ATPases that continually hydrolyze ATP (43).

The model in Scheme 1 presents multiple targets identified herein for improving H2 production to better match the solar cycle and improve the H2 yield. For instance, future improvements to cyanobacterial photo-H2 production via nitrogenases can be anticipated by: 1) maximizing the total pool size of carbohydrate (e.g. by growth in high salt media) and hence NADH and NADPH turnover, 2) increasing the expression of NDH-1 thus increasing both ATP generation and reductant flux from carbohydrate catabolism to PSI, 3) engineering carbohydrate catabolism so that less glycolytic flux and more oxidative pentose phosphate pathway flux occurs thereby producing more reductant for delivery to ferredoxin via PSI, 4) increasing the rate of nitrogenase-mediated H2 production by lowering its ATP demand, and 5) engineering nitrogenase so a larger percentage of electrons reduce H+ instead of N2. In fact, genetic engineering of the molybdenum nitrogenase from the nonphotosynthetic bacterium Azotobacter vinelandii has shown that replacement of a single amino acid in the enzyme results in ∼80% of the electrons being redirected to H2 from N2 (4). Additionally, by disrupting the two genes encoding homocitrate synthase in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, citrate can be incorporated into the FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase, thus favoring H2 production in a N2 atmosphere (5). Last, the knock-out of anaerobic pathways that recycle NADH to NAD+ (i.e. lactate dehydrogenase, as has been done in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (6)) should increase the accessible intracellular reductant pool under anoxia. If coupled to the removal of the two hydrogenases within the cell, this approach could divert a substantially increased flux of reductant to nitrogenase for H2 production. The recent development of a transformation system in Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822 with the use of ssDNA (44) may enable realization of the above mentioned genetic manipulations for further improving H2 production by strains of this genus. These manipulations will undoubtedly help overcome the reductant and ATP limitations we observe from in vivo nitrogenase-dependent H2 production rates.

Additionally, from a biotechnological standpoint, minimizing O2 production from the system has to be a future research focus as well, to realize the potential of photo-H2 pathways. This could involve 1) the search for O2-insensitive nitrogenases, 2) the development of a large scale optical filtering system such that only near-infrared light is transmitted to the bioreactor, and/or 3) the selective expression of an inactive D1 isoform to inactivate PSII-dependent O2 evolution under H2 producing conditions.

In conclusion, Cyanothece strains are promising because of their ability to grow on minimal media without combined nitrogen, their robust energy metabolism during anoxia, their ability to maintain low-oxic intracellular conditions conducive to H2 generating enzymes, and their strong coupling of carbohydrate catabolism to PQ reduction allowing rapid photo-H2 production in response to illumination. Although the net yield of H2 from Cyanothece is not increased over dark fermentative levels by the addition of illumination periods (see control in Fig. 3B), the rate of H2 production from the photo-pathway is significantly increased. Biotechnologically, this affords the most rapid conversion of intracellular reductant (which is shared between the dark and photo-pathways) to H2 (2-fold increase observed here). We imagine a system where reductant could accumulate under anoxia (perhaps in a strain with the hydrogenase knocked out) and then be quickly extracted (by conversion to H2) during an illumination period. The cycle could then be repeated.

Last, nitrogenase-mediated H2 production is unique in being unidirectional and not inhibited by H2 accumulation, a quality not found with the bidirectional hydrogenase. Although significant challenges remain in developing the potential of aquatic microbes for biological hydrogen production, including overall energy conversion efficiencies and scalability concerns, we hope that through the use of the above targets, subsequent studies can further our understanding and bring us closer to realizing the biotechnological potential of nitrogenase-mediated H2 production from Cyanothece.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Todd P. Michael and Dr. Randall Kerstetter for their contributions to obtaining genomic data on the strain, and Dr. Nicholas Bennette and Dr. Kelsey McNeely for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by United States Department of Energy Genomes to Life program Grant DE-PS02-07ER07-13 and Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant AFOSR-MURI-FA9550-05-1-0365.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and additional “Materials and Methods”.

N. J. Skizim and A. Krishnan, manuscript in preparation.

- PSII

- photosystem II

- PQ

- plastoquinone

- NDH

- NAD(P)H dehydrogenase

- LED

- light emitting diode

- E

- einstein

- DCMU

- 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

- DNP

- 2,4-dinitrophenol

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- DCCD

- N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- Chl

- chlorophyll.

REFERENCES

- 1. James B., Baum G., Perez J., Baum K. (2009) Technoeconomic boundary analysis of biological pathways to hydrogen production. Report No. SR-560–46674, p. 207, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carrieri D., Momot D., Brasg I. A., Ananyev G., Lenz O., Bryant D. A., Dismukes G. C. (2010) Boosting autofermentation rates and product yields with sodium stress cycling. Application to renewable fuel production by cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6455–6462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laurinavichene T. V., Kosourov S. N., Ghirardi M. L., Seibert M., Tsygankov A. A. (2008) Prolongation of H2 photoproduction by immobilized, sulfur-limited Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cultures. J. Biotechnol. 134, 275–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barney B. M., Igarashi R. Y., Dos Santos P. C., Dean D. R., Seefeldt L. C. (2004) Substrate interaction at an iron-sulfur face of the FeMo-cofactor during nitrogenase catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53621–53624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Masukawa H., Inoue K., Sakurai H. (2007) Effects of disruption of homocitrate synthase genes on Nostoc sp. strain PCC 7120 photobiological hydrogen production and nitrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7562–7570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McNeely K., Xu Y., Bennette N., Bryant D. A., Dismukes G. C. (2010) Redirecting reductant flux into hydrogen production via metabolic engineering of fermentative carbon metabolism in a cyanobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 5032–5038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKinlay J. B., Harwood C. S. (2010) Photobiological production of hydrogen gas as a biofuel. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21, 244–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bothe H., Schmitz O., Yates M. G., Newton W. E. (2010) Nitrogen fixation and hydrogen metabolism in cyanobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 529–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsygankov A. (2007) Nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. A review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 43, 250–259 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghirardi M. L., Posewitz M. C., Maness P. C., Dubini A., Yu J., Seibert M. (2007) Hydrogenases and hydrogen photoproduction in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 71–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallon J. R. (1992)Tansley Review no. 44. Reconciling the incompatible. N2 fixation and O2. New Phytol. 122, 571–609 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitsui A., Kumazawa S., Takahashi A., Ikemoto H., Cao S., Arai T. (1986) Strategy by which nitrogen-fixing unicellular cyanobacteria grow photoautotrophically. Nature 323, 720–722 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stöckel J., Welsh E. A., Liberton M., Kunnvakkam R., Aurora R., Pakrasi H. B. (2008) Global transcriptomic analysis of Cyanothece 51142 reveals robust diurnal oscillation of central metabolic processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6156–6161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schneegurt M. A., Tucker D. L., Ondr J. K., Sherman D. M., Sherman L. A. (2000) Metabolic rhythms of a diazotrophic cyanobacterium, Cyanothece sp. strain atcc 51142, heterotrophically grown in continuous dark. J. Phycol. 36, 107–117 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitsui A., Suda S. (1995) Alternative and cyclic appearance of H2 and O2 photoproduction activities under nongrowing conditions in an aerobic nitrogen-fixing unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Curr. Microbiol. 30, 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suda S., Kumazawa S., Mitsui A. (1992) Change in the H2 photoproduction capability in a synchronously grown aerobic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. Miami BG 043511. Arch. Microbiol. 158, 1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitsui A., Cao S., Takahashi A., Arai T. (1987) Growth synchrony and cellular parameters of the unicellular nitrogen-fixing marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. strain Miami BG 043511 under continuous illumination. Physiol. Plant. 69, 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Toepel J., Welsh E., Summerfield T. C., Pakrasi H. B., Sherman L. A. (2008) Differential transcriptional analysis of the cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142 during light-dark and continuous-light growth. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3904–3913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schneegurt M. A., Sherman D. M., Nayar S., Sherman L. A. (1994) Oscillating behavior of carbohydrate granule formation and dinitrogen fixation in the cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142. J. Bacteriol 176, 1586–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Min H., Sherman L. A. (2010) Hydrogen production by the unicellular, diazotrophic cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. strain ATCC 51142 under conditions of continuous light. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4293–4301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borodin V. B., Rao K. K., Hall D. O. (2002) Manifestation of behavioral and physiological functions of Synechococcus sp. Miami BG 043511 in a photobioreactor. Mar. Biol. 140, 455–463 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vignais P. M., Billoud B., Meyer J. (2001) Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25, 455–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ludwig M., Schulz-Friedrich R., Appel J. (2006) Occurrence of hydrogenases in cyanobacteria and anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Implications for the phylogenetic origin of cyanobacterial and algal hydrogenases. J. Mol. Evol. 63, 758–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maróti J., Farkas A., Nagy I. K., Maróti G., Kondorosi E., Rákhely G., Kovács K. L. (2010) A second soluble Hox-type NiFe enzyme completes the hydrogenase set in Thiocapsa roseopersicina BBS. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 5113–5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burgdorf T., van der Linden E., Bernhard M., Yin Q. Y., Back J. W., Hartog A. F., Muijsers A. O., de Koster C. G., Albracht S. P., Friedrich B. (2005) The soluble NAD(+)-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenase from Ralstonia eutropha H16 consists of six subunits and can be specifically activated by NADPH. J. Bacteriol. 187, 3122–3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vincent K. A., Parkin A., Armstrong F. A. (2007) Investigating and exploiting the electrocatalytic properties of hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 107, 4366–4413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Howitt C. A., Udall P. K., Vermaas W. F. (1999) Type 2-NADH dehydrogenases in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 are involved in regulation rather than respiration. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3994–4003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooley J. W., Vermaas W. F. (2001) Succinate dehydrogenase and other respiratory pathways in thylakoid membranes of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Capacity comparisons and physiological function. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4251–4258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peschek G. A., Obinger C., Paumann M. (2004) The respiratory chain of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria). Physiol. Plant. 120, 358–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Battchikova N., Eisenhut M., Aro E. M. (2011) Cyanobacterial NDH-1 complexes. Novel insights and remaining puzzles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zehr J. P., Waterbury J. B., Turner P. J., Montoya J. P., Omoregie E., Steward G. F., Hansen A., Karl D. M. (2001) Unicellular cyanobacteria fix N2 in the subtropical north Pacific ocean. Nature 412, 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reddy K. J., Haskell J. B., Sherman D. M., Sherman L. A. (1993) Unicellular, aerobic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria of the genus Cyanothece. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1284–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ananyev G., Carrieri D., Dismukes G. C. (2008) Optimization of metabolic capacity and flux through environmental cues to maximize hydrogen production by the cyanobacterium “Arthrospira (Spirulina) maxima.” Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6102–6113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nixon P. J., Rich P. R. (2006) in Chlororespiratory pathways and their physiological significance. The Structure and Function of Plastids (Wise R. R., Hoober J. K., eds) pp. 237–251, Springer, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klamt S., Grammel H., Straube R., Ghosh R., Gilles E. D. (2008) Modeling the electron transport chain of purple nonsulfur bacteria. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Falkowski P. G., Raven J. A. (1997) Aquatic Photosynthesis, p. viii, Blackwell, Malden, MA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Danon A., Stoeckenius W. (1974) Photophosphorylation in Halobacterium halobium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 1234–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bennette N. B., Eng J. F., Dismukes G. C. (2011) An LC-MS-based chemical and analytical method for targeted metabolite quantification in the model cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Anal. Chem. 83, 3808–3816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bandyopadhyay A., Stöckel J., Min H., Sherman L. A., Pakrasi H. B. (2010) High rates of photobiological H2 production by a cyanobacterium under aerobic conditions. Nat. Commun. 1, 139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dutta D., De D., Chaudhuri S., Bhattacharya S. K. (2005) Hydrogen production by Cyanobacteria. Microb. Cell Fact. 4, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carrieri D., Ananyev G., Costas A. M. G., Bryant D. A., Dismukes G. C. (2008) Renewable hydrogen production by cyanobacteria. Nickel requirements for optimal hydrogenase activity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 33, 2014–2022 [Google Scholar]

- 42. van der Oost J., van Walraven H. S., Bogerd J., Smit A. B., Ewart G. D., Smith G. D. (1989) Nucleotide sequence of the gene proposed to encode the small subunit of the soluble hydrogenase of the thermophilic unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC 6716. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 10098. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koebmann B. J., Westerhoff H. V., Snoep J. L., Nilsson D., Jensen P. R. (2002) The glycolytic flux in Escherichia coli is controlled by the demand for ATP. J. Bacteriol. 184, 3909–3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Min H., Sherman L. A. (2010) Genetic transformation and mutagenesis via ssDNA in the unicellular, diazotrophic Cyanobacteria of the Genus Cyanothece. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., AEM 76, 7641–7645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.