Abstract

Objective

To understand the scope of semantic impairment in semantic dementia.

Design

Case study.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Patient

A man with semantic dementia, as demonstrated by clinical, neuropsychological, and imaging studies.

Main Outcome Measures

Music performance and magnetic resonance imaging results.

Results

Despite profoundly impaired semantic memory for words and objects due to left temporal lobe atrophy, this semiprofessional musician was creative and expressive in demonstrating preserved musical knowledge.

Conclusion

Long-term representations of words and objects in semantic memory may be dissociated from meaningful knowledge in other domains, such as music.

Semantic dementia (SemD) IS a primary progressive form of aphasia characterized by impaired semantic memory affecting confrontation naming and the interpretation of word and object meaning.1 Two recent cases of relatively preserved musical knowledge in SemD have been reported,2,3 although the absence of detailed analyses limits our ability to learn from these patients. We describe preserved ability to perform music in a 64-year-old semiprofessional harpsichordist with SemD. Analysis of his performance of pieces from the Baroque period that were familiar and unfamiliar to him revealed remarkably preserved musical expression abilities and creativity despite profound difficulty with word and object meaning and significant left anterior temporal atrophy. These observations are consistent with a modular approach to semantic memory that dissociates long-term representations of word and object meaning from meaningful knowledge in other domains, such as music.

REPORT OF A CASE

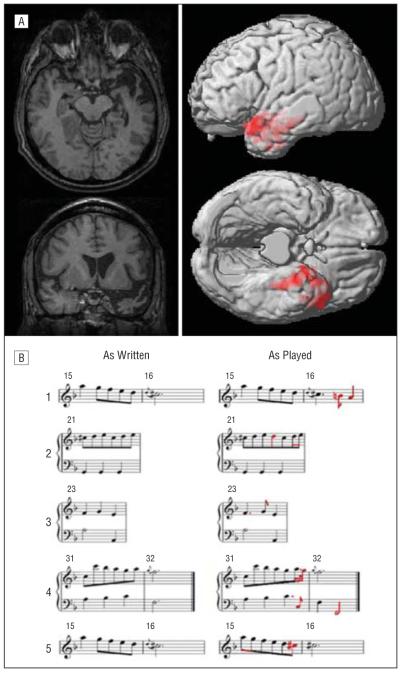

Our proband is a right-handed computer programmer with 20 years of educational attainment. He was diagnosed with SemD at age 59 years, ie, 5 years after symptom onset and 5 years prior to this study. Initial evaluation revealed word-finding difficulty, impaired confrontation naming, poor comprehension of familiar words such as “thumb” and “stool,” and surface dyslexia. Visual-perceptual skills, praxis, episodic memory, and mathematical abilities had been spared. Comprehension of words and objects gradually declined, and word-finding became increasingly limited. At the time of musical assessment on October 3, 2008 (which had been approved by University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board), our proband had virtually no comprehension of oral or written language and was mute. He mishandled objects such as a corkscrew and a tuning fork, appearing not to understand their intended functions. He continued to perform multidigit written calculations rapidly and accurately and easily copied a complex geometric design. His social comportment was generally appropriate, although he had begun to demonstrate mild euphoria, as manifested in actions such as overly exuberant greetings. He followed established daily routines that could be interrupted by his wife without causing him distress. Longitudinal neuropsychological testing is summarized in eTable 1 (http://www.archneurol.com). Quantitative analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging in our proband relative to 15 age-matched control individuals showed significant left anterior temporal cortical atrophy (P<.05 error-corrected familywise; Figure, A and eTable 2).

Figure.

Brain atrophy and musical embellishments in a case of semantic dementia. A, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain of our proband. Images on the left show T1-weighted MRI demonstrating left anterior temporal atrophy, indicated in red. Images on the right show cortical atrophy (P<.05, familywise error-corrected for multiple comparisons) relative to 15 age-matched control individuals using optimized voxel-based morphometry. The brains of our proband and the controls were imaged with a Siemens Trio 3T MRI device (Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) using a 3D spoiled-gradient echo sequence, repetition time=1620 milliseconds, echo time=3 milliseconds, slice thickness=1 mm, flip angle=15°, matrix=195×256, and in-plane resolution=0.9×0.9 mm. All processing was performed using SPM5 statistical parametric mapping software (Wellcome Trust Center Neuroimaging, London, England). The gray matter volume was smoothed with a 4-mm full width–half maximum gaussian kernel to minimize individual gyral variations. Two-sample t tests identified significant cortical atrophy in our proband by contrasting his gray matter volume with that of the controls, including clusters greater than 100 adjacent voxels. Coordinates for each peak meeting statistical criteria were converted to Talairach space (eTable 2). B, Representative transcriptions illustrating nonnotated embellishments made by our proband while sight-reading unfamiliar piece of music from the Baroque period. The left-hand column shows portions of the score available during the proband’s performance; the right-hand column shows notes in red that he played to embellish the score. Part 5 illustrates a different embellishment of the same segment of the piece illustrated in part 1, which he had played 2 months previously.

MUSICAL STUDY OF OUR PROBAND

Our proband had begun playing piano at age 8 and had studied organ throughout college before turning to the harpsichord. He became skilled in Baroque music performance involving embellishments with ornaments (eg, trills andrhythmic variation) that are minimally notated in the score. He participated in master classes, lectured on public radio, and performed for 26 years. Since his retirement at the time of diagnosis, he has played harpsichord for 2 hours daily.

Herein, we report digital recordings of our proband’s performances and analyses of several pieces he played from scores during two 40-minute sessions. These pieces included 9 French Baroque works he had selected, ranging from frequently played favorites to pieces he had not played in more than a decade. These complex and technically demanding pieces were played with rich, varied, skillfully executed ornamentation. Appropriate and expressive phrasing was clearly present. His rhythm was occasionally uneven, but wrong notes were rare.

He also played 7 brief works we provided. Although our proband may have heard these works previously, they were not part of his repertoire and they were unfamiliar to his wife, thus presumably requiring him to sight-read them. In the representative piece we analyze in detail herein, (Minuet in F, no. 3, from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Notebooks for Anna Magdalena Bach), our proband’s error rate was minimal: of a total of 260 notes, he played 1 (0.4%) wrong and omitted 3 (1.2%); his playing was rhythmically unstable in 4 of 32 (12.5%) measures. He produced novel, stylistically appropriate embellishments in 11 (34.4%) of the measures. These included creative and expressive additions of ornamentation (7 instances), rhythmic variation (5 instances), and emphases on melodic or harmonic structure (2 instances). Figure, B shows 4 examples. In measure 16 (part 1), our proband extended the melody line to emphasize a harmonic modulation. In measure 21 (part 2), he enriched texture by filling in melodic gaps and adding rhythmic variation. In measure 23 (part 3), he altered the rhythmic pattern of 3 notes written as equal beats, a stylistic practice known as notes inégales. In measures 31 and 32, which end the piece (part 4), he embellished the melody line and emphasized the closing of the work by repeating each of the 2 final bass-line notes an octave lower. When playing the same piece 2 months later, his embellishments differed. In measures 15 and 16, for example, he originally added notes in measure 16 but not in measure 15 (part 1); in the subsequent performance (part 5), he added notes in measure 15 but not in measure 16 (contrast the “as played” portions of parts 1 and 5).

Our proband also demonstrated his understanding of formal music structure in his embellished performance of a familiar piece (Suite in C Major: Passacaille, by François Couperin) containing an alternating theme-and-variation pattern. He differentiated the notationally identical initial and final presentations of the theme with a retard, ie, a gradual slowing of the tempo to mark the close of the work. His final presentation of the theme was 27% longer than in the initial presentation (16.81 vs 13.12 seconds, respectively). The longer duration of the final presentation represents gradual changes culminating in a lengthened final measure, not simply a consistently slower tempo. The first, penultimate, and final measures of the 8-measure theme lasted 1.46, 1.57, and 1.40 seconds, respectively, when introduced at the beginning of the piece, whereas the corresponding measures lasted 1.25, 1.89, and 4.36 seconds, respectively, when played at the end of the piece. Moreover, our proband emphasized the retard by slowing the ornamentation: the theme’s closing measure contained a rolled chord, which he played at half speed in the final compared with the initial presentation (0.44 vs 0.22 seconds, respectively).

COMMENT

Our proband performed technically demanding, structurally complex compositions in an expressive manner. Beyond the motor skills required in playing a keyboard instrument and the visuoperceptual skills required to read scores, his performance erred minimally with regard to the cognitive skills involved in interpreting symbolic notation. Most significantly, he created novel, varied, stylistically appropriate embellishments that were not specified in the score. This was observed during unfamiliar pieces, emphasizing that his musical knowledge does not depend on episodic memory. Our proband’s varied embellishments throughout the period of the study also demonstrate that his retained musical ability is not procedural (ie, habitually striking keys in response to visual stimuli) but reflect his meaningful and productive control over musical knowledge.

These observations help clarify the nature of semantic memory loss in SemD. Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the semantic impairment in SemD targets a particular type of concept without robbing these patients of all meaningful knowledge. Specifically, patients with SemD, unlike the general population, appear to maintain semantic memory for abstract concepts (such as “justice”) relatively better than concrete object concepts (such as “chair”).4-7 Semantic impairment in SemD thus appears to manifest most markedly regarding visually based concepts such as concrete objects and their names. This may occur partly because of the degradation of visuoperceptual features of object concepts represented in the visual association cortex of the compromised temporal lobe.7,8 Whereas there are many theories of musical meaning, musical semantics depends partly on understanding the structural attributes of a musical piece9-12 without ties to concrete visual referents and thus partly may resemble the semantics of abstract concepts. Consistent with this argument, we found that key elements of musical semantics are preserved in our proband, who has profound difficulty understanding object concepts owing to anterior temporal disease. This unique feature was difficult to discern in previous reports of preserved music in SemD. One case individual continued musical composition and performance for 1 year following the onset of diminished language comprehension but details of his musical and semantic abilities were not provided.2 A second patient with SemD was an untrained musician able to hum familiar, popular songs.3

Neuroimaging studies of the neurobiology of music implicate frontal, parietal, and posterior temporal regions.13 These areas are largely preserved in our proband, particularly in the right hemisphere, and thus are consistent with the possibility that musical knowledge may be relatively preserved in SemD. Preserved knowledge also has been observed in other domains that rely on less-affected cortical areas in SemD. For instance, the meaning of number concepts appears to depend largely on the parietal cortex,14 an area relatively spared in SemD, and competence with number knowledge has been demonstrated in these patients.15,16 These observations, along with those of our case study, are consistent with the hypothesis that knowledge represented in semantic memory is partly modular, dissociating long-term representations of object and word concepts from meaningful knowledge in other domains, such as music.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This case report was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants AG17586, AG15116, NS44266, AG32953, and NS53488).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Weinstein, Koenig, McMillan, Bonner, and Grossman had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Weinstein, Koenig, Bonner, and Grossman. Acquisition of data: Koenig and Grossman. Analysis and interpretation of data: Weinstein,Koeng,Gunawardena,McMillan,and Grossman.Drafting of the manuscript: Weinstein, Koenig, Gunawardena, McMillan, and Grossman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Weinstein, Koenig, and Grossman. Statistical analysis: Weinstein, Koenig, McMillan, and Grossman. Obtained funding: Grossman. Administrative, technical, and material support: Weinstein and Grossman. Study supervision: Koenig and Grossman.

Previous Presentations: Portions of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; April 28, 2009, Seattle, Washington.

Online-Only Material: The eTables are available at http://www.archneurol.com.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Grossman is a consultant for Allon Therapeutics Inc, Forest Laboratories Inc, and Pfizer Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodges JR, Patterson K. Semantic dementia: a unique clinicopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):1004–1014. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller BL, Boone K, Cummings JL, Read SL, Mishkin F. Functional correlates of musical and visual ability in frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:458–463. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hailstone JC, Omar R, Warren JD. Relatively preserved knowledge of music in semantic dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):808–809. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.153130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi H-A, Moore P, Grossman M. Reversal of the concreteness effect for verbs in patients with semantic dementia. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(1):9–19. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breedin SD, Saffran EM, Coslett HB. Reversal of a concreteness effect in a patient with semantic dementia. Cogn Neuropsychol. 1995;11:617–660. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warrington EK. The selective impairment of semantic memory. Q J Exp Psychol. 1975;27(4):635–657. doi: 10.1080/14640747508400525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonner MF, Vesely L, Price C, et al. Reversal of the concreteness effect in semantic dementia. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2009;26(6):568–579. doi: 10.1080/02643290903512305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman M, McMillan C, Moore P, et al. What’s in a name: voxel-based morphometric analyses of MRI and naming difficulty in Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia and corticobasal degeneration. Brain. 2004;127(pt 3):628–649. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koelsch S, Kasper E, Sammler D, Schulze K, Gunter T, Friederici AD. Music, language and meaning: brain signatures of semantic processing. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(3):302–307. doi: 10.1038/nn1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer LB. Emotion and Meaning in Music. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, Illinois: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koelsch S. Neural substrates of processing syntax and semantics in music. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krumhansl CL. An exploratory study of musical emotions and psychophysiology. Can J Exp Psychol. 1997;51(4):336–353. doi: 10.1037/1196-1961.51.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zatorre RJ, Chen JL, Penhune VB. When the brain plays music: auditory-motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(7):547–558. doi: 10.1038/nrn2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehaene S, Piazza M, Pinel P, Cohen L. Three parietal circuits for number processing. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2003;20(3):487–506. doi: 10.1080/02643290244000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern CH, Glosser G, Clark R, et al. Dissociation of numbers and objects in corticobasal degeneration and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2004;62(7):1163–1169. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118209.95423.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappelletti M, Butterworth B, Kopelman MD. Spared numerical abilities in a case of semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39(11):1224–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.