Abstract

Background and Aims

Hybrid proline-rich proteins (HyPRPs) represent a large family of putative cell-wall proteins characterized by the presence of a variable N-terminal domain and a conserved C-terminal domain that is related to non-specific lipid transfer proteins. The function of HyPRPs remains unclear, but their widespread occurrence and abundant expression patterns indicate that they may be involved in a basic cellular process.

Methods

To elucidate the cellular function of HyPRPs, we modulated the expression of three HyPRP genes in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cell lines and in potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants.

Key Results

In BY-2 lines, over-expression of the three HyPRP genes with different types of N-terminal domains resulted in similar phenotypic changes, namely increased cell elongation, both in suspension culture and on solid media where the over-expression resulted in enhanced calli size. The over-expressing cells showed increased plasmolysis in a hypertonic mannitol solution and accelerated rate of protoplast release, suggesting loosening of the cell walls. In contrast to BY-2 lines, no phenotypic changes were observed in potato plants over-expressing the same or analogous HyPRP genes, presumably due to more complex compensatory mechanisms in planta.

Conclusions

Based on the results from BY-2 lines, we propose that HyPRPs, more specifically their C-terminal domains, represent a novel group of proteins involved in cell expansion.

Keywords: Cell extension, cell wall loosening, cell wall protein, hybrid proline-rich proteins, HyPRP, lipid transfer proteins, LTP, potato, Solanum tuberosum, tobacco, Nicotiana tabacum, BY-2 cell line

INTRODUCTION

Hybrid proline-rich proteins (HyPRPs) represent a group of putative cell-wall proteins characterized by an unusual domain structure, which was deduced only from the primary amino acid sequence, as no HyPRP has been characterized directly on the protein level. The N-terminal domains resemble typical structural cell-wall proteins, especially a group of proline-rich proteins (PRPs) in which the domains are often repetitive and usually rich in proline. However, HyPRPs do not contain amino acid motifs that are typically found in PRPs (Josè-Estanyol et al., 2004). The N-terminal domains of HyPRPs are highly variable in size and amino acid composition – in some proteins glycine even predominates over proline (Josè-Estanyol et al., 2004; Dvořáková et al., 2007). The primary amino acid sequence of some proline-rich domains indicates possible glycosylation with arabinogalactan polysaccharides (Showalter et al., 2010), but it is not a common feature of the whole family. The C-terminal domain is atypical for structural cell-wall proteins. It is rather hydrophobic and consists of several putative α-helices, which could be transmembrane. However, the presence of eight cysteine residues arranged in a specific pattern indicates that HyPRPs belong to the large superfamily of eight-cysteine motif (8CM) proteins, together with well characterized lipid-transfer proteins (LTPs) and several other groups of extracellular proteins (Josè-Estanyol et al., 2004). The 8CM residues of these proteins are not integrated within the membrane. The 8CM domains usually consist of 90–100 amino acids, where the eight cysteine residues are believed to be essential for the formation of a three-dimensional structure. The tertiary structure of the 8CM domain, which has been determined for LTPs and some other members of the 8CM family, consists of four α-helices held in a compact fold by four disulfide bridges that form a hydrophobic cavity/tunnel inside (Gincel et al., 1994). The cavity of LTPs was shown to bind a variety of lipids and other hydrophobic ligands (Yeats and Rose, 2008). As well as the above-mentioned members of the 8CM superfamily, there are other proteins containing domains with eight conserved cysteines residues, e.g. lectins with cystein-rich hevein domains (Van Damme et al., 2004) or wheat germ agglutinin, characterized by so called toxin-agglutinin fold kept by four cystein bridges (Drenth et al., 1980). However, the cystein pattern, cystein bridging, the hydrophobicity profile and the size of these domains differ significantly from 8CM domains.

HyPRPs form large gene families with up to 52 members in maize (Dvořáková et al., 2007). Expression of HyPRP genes was detected in various stages of plant ontogeny and in various tissues of many seed plant species. The expression was also affected by numerous endogenous and environmental factors (Josè-Estanyol and Puigdomènech, 2000). A comprehensive analysis of 14 potato HyPRP genes showed highly variable, partially overlapping and/or complementary expression patterns in different organs. In arabidopsis, the expression patterns were partially conserved between closely related paralogous genes (Dvořáková et al., 2007), whereas almost identical orthologous HyPRP genes TPRP-F1 and StPRP from tomato and potato exhibited almost completely different expression patterns (Fischer et al., 2002).

The role of HyPRPs as well as their precise localization in the cell wall remains unclear, in contrast to the relatively better characterized families of other structural cell-wall proteins. The function of HyPRPs has been inferred primarily from their expression profiles, so the spectrum of proposed functions reflects the variation of their expression. For example, the HyPRPs DC2·15 (Daucus carota), FaHyPRP (Fragaria ananassa) and CELPs (Nicotiana tabacum) have been suggested to play roles in plant ontogeny and morphogenesis of different organs (Wu et al., 1993; Holk et al., 2002; Blanco-Portales et al., 2004); BnPRP (Brassica napus), CcHyPRP (Cajanus cajan), EARLI1 (Arabidopsis thaliana) and MsPRP2 (Medicago sativa) to play roles in plant responses to multiple stress factors like cold, frost, drought, salinity and heat (e.g. Deutch and Winicov, 1995; Goodwin et al., 1996; Zhang and Schläppi, 2007; Priyanka et al., 2010); and SbPRP (Glycine max), ZmHyPRP (Zea mays ) and MtPPRD1 (Medicago truncatula) to be involved in plant defenses against viral or fungal pathogens (Josè-Estanyol et al., 1992; He et al., 2002; Bouton et al., 2005).

Although many roles have been suggested for HyPRPs in planta, the mechanistic insight into their function in the cell wall has been lacking. According to Blanco-Portales et al. (2004) a C-terminal domain of strawberry FaHyPRP may reside in plasma membrane and the N-terminal part may anchor cell-wall polymeric polyphenols. The function of HyPRPs in the interconnections between the plasma membrane (by the hydrophobic C-terminal domain) and the cell wall (by the N-terminal domain) was also suggested by other authors (Deutch and Winicov, 1995; Goodwin et al., 1996; Holk et al., 2002; Zhang and Schläppi, 2007). The structural reinforcement mediated by such interconnections might protect cells against plasmolysis in various stress reactions (Goodwin et al., 1996). However, as already mentioned, the α-helices of the C-terminal domain are unlikely to be transmembrane. Therefore, we presumed that the domain either interacts with the plasma membrane through some specific binding site or with some molecules within the cell wall. Alternatively, because the N-terminal proline-rich domains are expected to interact with different cell-wall components, HyPRPs might participate in cell wall cross-linking.

To test the hypothesis that HyPRPs act as linkers between the cell wall and plasma membrane or interconnect some components of the cell wall, we prepared a modified gene encoding an HyPRP with a completely deleted N-terminal domain (Fig. 1). The truncated gene encoded just the C-terminal domain, which would functionally compete with the native full-length protein for its hypothetical interactor and thus interfere with the potential linker function of HyPRP. However, over-expression of the truncated HyPRP gene in tobacco BY-2 lines unexpectedly caused increased cell elongation, and therefore we tested an alternative hypothesis that the C-terminal domain of HyPRPs may function in cell expansion as previously described for a member of the related LTP family (Nieuwland et al., 2005). In subsequent experiments, we analysed the mechanism of HyPRP action and the role of N-terminal domains, whose length and amino acid composition was previously found to be a phylogenetically significant feature (Dvořáková et al., 2007). In addition to the functional analysis of HyPRPs in cell cultures, we also studied their role in planta through analysis of the effects of HyPRP over-expression on potato plant phenotype and morphogenesis.

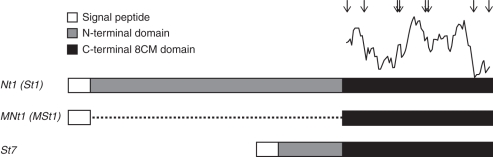

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the HyPRP genes used in the study. The curve above the C-terminal domain shows helix propensity of the sequence (ProtScale–Chou and Fasman algorithm; www.expasy.org; Gaisteiger et al., 2005). Arrows indicate positions of eight conserved cysteine residues. The dotted line indicates the deleted sequence of the N-terminal domain in MNt1 and MSt1 genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of constructs for modulation of HyPRP expression

Gene constructs were prepared for the over-expression of St7 and Nt1 genes and modified St1 (MSt1) and Nt1 (MNt1) genes with deleted sequences coding for N-terminal proline-rich domains. All sequences were amplified using PCR (for primer sequences, see Supplementary Data Table S1, available online) from genomic DNA, isolated according to the procedure of Shure et al. (1983). Alternatively, we used RT-PCR with oligo-dT23 primer and RevertAidTM M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, Burlington, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with total RNA according to Stiekema et al. (1988). The modified St1 (MSt1) and Nt1 (MNt1) genes with deleted sequences coding for N-terminal proline-rich domains consist only of signal sequences and sequences of C-terminal domains. The two separately amplified parts were connected using PCR with specific primers with short sequence extensions. PCR products were cloned into the pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen PCR Cloning kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using TA cloning, or into the vector pBluescriptII KS+ (Fermentas). The final gene constructs/genes were inserted into the binary vector pCP60 (provided by Dr P. Ratet, ISV-CNRS, France; Bolte et al., 2004) between the 35S promoter and nopalin synthase terminator. All constructs were sequenced to verify accuracy.

Cultivation and transformation of plant material

Potato plants (Solanum tuberosum) ‘Désirée’ were cultured in vitro on LS medium (Linsmayer and Skoog, 1965) with 3 % (w/v) sucrose. Plants were cultivated in 16 h/8 h light/dark regime at 120 W m−2, propagated through apical or nodal cuttings, and subcultured every 4–5 weeks. Leaves of 4-week-old potato plants were transformed according to Dietze et al. (1995) using Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain C58C1 with plasmid pGV2260; Deblaere et al., 1985) carrying the binary vector pCP60 with kanamycin resistance and a specified HyPRP gene insert.

Tobacco BY-2 cell culture (Nicotiana tabacum ‘Bright Yellow’; Nagata et al., 1992) was grown in modified MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 3 % (w/v) sucrose. Cell lines were cultured either in a suspension culture in liquid MS medium with continuous shaking, or in the form of calli on MS media solidified with 0·8 % (w/v) agar in the dark at 26 °C. Suspension cultures were subcultured every 7 d by transferring 1·5 mL of the suspension culture into 30 mL of the fresh MS medium; calli were sub-cultured every 3–4 weeks. Transformation of tobacco BY-2 cells as well as potato plants was performed using the same strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying the binary vector pCP60 harbouring different HyPRP genes. Exponential cell suspension (3–4 d after subculturing) was filtered and the cells were resuspended in 30 mL of fresh MS medium. Fifteen microlitres of 40 mm acetosyringone were added to the suspension and thoroughly mixed using a 10 mL pipette with the tip cut off. Three millilitres of Agrobacterium suspension were then added to the cell suspension and co-cultivated for 3 d in the dark at 26 °C. The cells were then washed with 300 mL of 3 % (w/v) sucrose and 100 mL of MS medium supplemented with 100 mg L−1 cefotaxime. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 2–3 mL of liquid MS medium containing cefotaxime and evenly spread onto a Petri dish with solid MS medium containing cefotaxime plus 50 mg L−1 kanamycin. Transformed cells were cultivated for 3–4 weeks in the dark at 26 °C, and the calli which grew were transferred onto fresh MS medium with the same antibiotics. Antibiotics were used only during the first 4–5 weeks after transformation. Suspension cultures used for the phenotype assessment were cultured in the absence of antibiotics.

Evaluation of the phenotype of transgenic tobacco BY-2 cell lines

Images documenting the phenotype of transformed cell lines were obtained using a fluorescent microscope (Olympus Provis AX70 or Olympus BX51), grabbed with a digital TV camera (Sony DXC-950P; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and digitized with Lucia image analysis software (version 5, Laboratory Imaging, Prague, Czech Republic). The length of the cells analysed was measured using Lucia software. Evaluated lines were analysed without knowing their identity. For each cell line, three to five randomly selected frames with a total of 150–250 cells were obtained. The length of all cells in the frames was determined as the maximum dimension in the longitudinal axis of the cell. The mean value of cell length of the wild-type tobacco BY-2 cell control was calculated from the dataset obtained from three individual control lines (C1, C2, C3) to account for internal variability of the cell cultures. Differences between cell lines transformed with each HyPRP gene were tested for significance using statistical software NCSS version 2000 and GLM ANOVA. A variant (BY-2, GFP, St7, Nt1, MNt1) was used as a fixed factor in the model and a single evaluated line as nested factor. The significance level for testing of zero hypothesis was selected at 5 % (α = 0·05). Length differences of individual transgenic lines in the experiment in Fig. 2A were tested by the Mann–Whitney U test (α = 0·05). Cell lines were considered as longer or shorter when significantly different from all three wild-type control lines C1–C3.

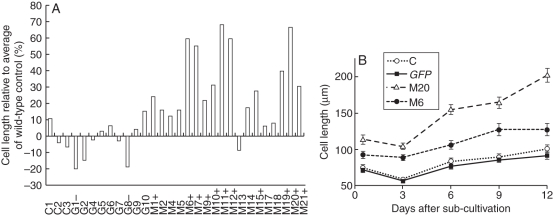

Fig. 2.

Cell elongation in transgenic tobacco BY-2 lines harbouring the MNt1 gene. (A) Average cell lengths in randomly selected lines transformed with the MNt1 and GFP genes are compared with the mean value of 86 µm in wild-type BY-2 cells. Cell lengths on the 7th day of the sub-cultivation interval are compared (3 weeks after the transfer to liquid media). C1–C3, Wild-type BY-2 control lines; G1–G10, lines transformed with the GFP gene; M1–M21, lines transformed with the MNt1 gene. Transgenic lines are considered as longer (indicated with +) or shorter (–) than controls when significantly different from the average cell lengths of all three wild-type lines C1–C3 by Mann–Whitney U test (α = 0·05). (B) Average cell lengths (± s.e.) of selected lines during 7-d sub-cultivation interval and prolonged stationary phase up to the 12th day. Abbreviations: C, wild-type BY-2 control line; GFP, cell line transformed with the GFP gene; M20 and M6, representative cell lines transformed with the MNt1 gene.

For protoplasts preparation, 3- to 5-d-old cells in exponential phase of growth were treated with 1 % (w/v) cellulase ‘Onozuka’ R-10 (Yakult Honsha Co., Tokyo, Japan) and 0·1 % (w/v) pectolyase Y-23 (Kyowa Chemical Products Co., Osaka, Japan) in 0·45 m mannitol and incubated at 24 °C for 3–4 h. The proportion of round-shaped protoplasts and the total cell number were determined at 30-min intervals (a total of 400–700 cells in each interval).

For plasmolysis experiments, cells in exponential phase were incubated in 0·45 m or 0·6 m mannitol for 10 min. To evaluate shrinkage of the protoplast, the cells were stained with fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and calcofluor white to identify the protoplast and the cell wall, respectively (Supplementary Data Fig. S1), and their projected areas were obtained by fluorescence microscopy at ×200 magnification. The projected areas were detected as an intensity level threshold in the blue channel for the whole cell (calcofluor-labelled cell wall) and the green channel for the protoplast (FDA label), both manually adjusted to accurately cover the observed area (software Lucia version 5·0).

Evaluation of expression patterns of HyPRP genes

Expression of HyPRP genes was evaluated by semi-quantitative RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from the upper leaves and roots of potato plants ‘Désirée’ (4-week-old plants grown in vitro) and from tobacco BY-2 cell suspensions in exponential phase (3 d after subculturing) using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription with oligo-T23 primer and RevertAidTM M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Fermentas) was performed starting with equal amounts of RNA (1 µg) pretreated with DNase I according to the manufacturer's instructions. For primers used in PCR, see Supplementary Data Table S1 or Dvořáková et al. (2007). PCR products were separated on agarose gels in the presence of ethidium bromide or GelRed™ nucleic acid stain (Biotium, Hayward, CA, US). Gel images were taken in transmitted UV light using an Olympus C-4040 digital camera.

Nucleotide sequence data can be found in Solanaceae Genomics Network under accession numbers SGN-U268850 (St1), SGN-U272247 (St7) and in GenBank under accession number JF803736 (Nt1).

RESULTS

Gene selection and preparation of HyPRP constructs

Full-length HyPRP genes were isolated from potato (St1 and St7) and from tobacco genomic DNA (Nt1; Fig 1; for protein sequence see Supplementary Data Table S2). St1 and Nt1 genes encode highly similar orthologues belonging to the subgroup of conserved C-type HyPRPs that are characterized by a long, partially hydrophobic N-terminal domain and a broad expression pattern. The C-type subgroup of HyPRPs is represented by two members in potato (Dvořáková et al., 2007). By contrast, St7 is a representative of HyPRPs with short N-terminal domains (about 14 members in potato; Dvořáková et al., 2007) and its expression is restricted to roots. To study the HyPRP function, we prepared modified genes MSt1 and MNt1 encoding the C-type HyPRPs with a completely deleted N-terminal domain (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data Table S2). Cell lines over-expressing the respective HyPRP genes are referred to in the text as Nt1, MNt1, St1, MSt1, St7 lines.

Over-expression of the modified Nt1 gene (MNt1) in tobacco BY-2 cells

The modified MNt1 protein lacking the N-terminal domain was expected to compete with the endogenous wild-type Nt1 for a hypothetical interactor. The phenotype of BY-2 cells transformed with MNt1 driven by the CaMV 35S promoter was compared with those transformed with the GFP gene to evaluate potential effects of the transformation procedure and the initial cultivation on kanamycin selective media. In addition, non-transformed wild-type cell lines derived from calli were used to assess the internal variability of tobacco BY-2 suspensions and the effect of callus-to-suspension transition.

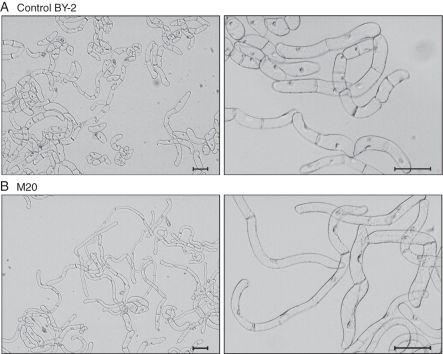

In total, 18 randomly selected MNt1 lines were compared microscopically with nine GFP control lines and three lines of the wild-type controls. The only phenotypic alteration observed in the MNt1 lines was an increase in cell length, which was significant in 11 out of the 18 lines (Fig. 2A). The average cell length was increased by up to 60 % compared with the mean length of 86 µm in wild-type controls. The difference in the cell length was obvious during the whole 7-d sub-cultivation interval as well as during the prolonged stationary phase up to the 12th day (Fig. 2B). The cell width and other morphological parameters of the MNt1 cells did not significantly differ in the majority of the lines (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Morphology of wild-type tobacco BY-2 cells and cells harbouring the MNt1 gene (M20). (A) Suspensions of BY-2 and (B) MNt1 cultures on the 6th day of the sub-cultivation interval at two different magnifications. Bright field. Scale bars = 100 µm.

To evaluate potential correlation between cell elongation and MNt1 expression, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR in two sets of lines; characterized with the most-elongated cells (M6, M7, M11, M12 and M20) and the least-elongated cells, comparable with wild-type BY-2 cells (M2, M4, M13, M17 and M18). Surprisingly, MNt1 transcript levels were relatively high in practically all lines and did not correlate with the cell length (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Interestingly, the two contrasting sets of MNt1 lines differed in the expression of their resident native Nt1 gene, so that the lines with relatively short cells seemed to have down-regulated expression of the Nt1 gene, whereas in four out of five cases the lines with long cells kept the Nt1 transcript at higher level. Thus, the cell elongation appears to correlate with Nt1 expression or theoretically the sum of both genes, indicating that the effects of the truncated and native gene were additive rather than MNt1 competitively inhibiting the function of Nt1.

Over-expression of HyPRP genes with short and long proline-rich domains in tobacco BY-2 cells

Considering that the truncated MNt1 yields a single 8CM motif, we analysed more broadly the impact of HyPRPs and their N-terminal domains on cell elongation. Constructs with two other HyPRP genes were prepared and introduced into tobacco BY-2 cell lines: wild-type tobacco Nt1 gene encoding 262 amino acids in the N-terminal domain, and potato St7 gene encoding a short, 28 amino acids N-terminal domain (Fig. 1; Supplementary Data Table S2). For cell length measurements, ten newly transformed MNt1 lines, four wild-type BY-2 cell sub-lines and six newly generated GFP lines were used as controls.

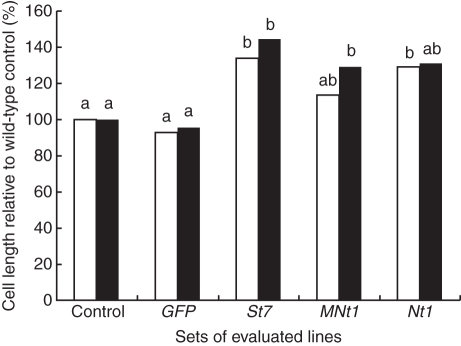

The average cell lengths of ten randomly selected Nt1 lines, five St7 lines and ten MNt1 lines were significantly larger than the cell lengths of GFP and wild-type control lines in at least one of two independent measurements (Fig. 4). No statistically significant differences were found when comparing the lines transformed with the three different HyPRP genes, indicating that the effects of all three tested genes were comparable. The enhanced elongation of cells transformed with the HyPRP genes seen in the suspension culture during the stationary phase of growth was consistently accompanied by reduced fluidity, which was evident when shaking or pipetting the cultures. However, there was no significant difference in the dry weights of the control and HyPRP lines (data not shown). The calli over-expressing HyPRP genes grew larger than those transformed with the GFP gene. This was observed, both directly after transformation and after cloning individual cells from four lines over-expressing any of the three HyPRP genes (see examples in Fig. 5). The average calli areas of four tested lines were significantly larger than the mean callus area of the GFP transformed line (GFP = 100 %; Nt1, 198 %, MNt1, 218 %; St7-1, 280 %; St7-2, 144 %; n = 219–325). The differences in callus size seemed to be primarily related to cell size. The average cell length of twelve 10-d-old calli obtained by cloning was significantly higher in St7-over-expressing cells compared with the GFP ones. The average cell lengths were 112·3 µm and 75·0 µm for St7 and GFP, respectively, which corresponds well with the values determined in suspension cultures.

Fig. 4.

Average cell length of transgenic and control tobacco BY-2 lines. Cell length in the stationary phase of growth was measured in two independent experiments as indicated by black and white columns. Control, the means of four wild-type tobacco BY-2 lines; GFP, the means of six independent lines transformed with the GFP gene; St7, MNt1 and Nt1, the means of five to ten independent lines transformed with genes encoding HyPRPs with different N-terminal domains (St7, short; Nt1, long; MNt1, deleted). Cell lengths are expressed as a percentage of the average cell length in wild-type BY-2 lines (= 100 %). Data columns indicated by different letters are significantly different at α = 0·05 within the repetition; columns that share the same letter do not differ significantly.

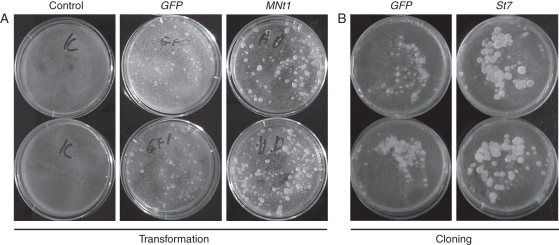

Fig. 5.

Growth of transgenic tobacco BY-2 calli after transformation and cloning. (A) Transformation: representative Petri dishes (two per each variant) with calli of BY-2 cells transformed with GFP and MNt1 genes grown on selective media for 4 weeks after transformation (co-cultivation with Agrobacterium). (B) Cloning: calli (4 weeks old) forming from individual cells of selected GFP and St7 lines growing on a feeder layer of untransformed BY-2 cells (cloning was performed according to Nocarova and Fischer, 2009).

To test for potential changes in the structure and integrity of the cell wall in the HyPRP-over-expressing cell lines, St7-over-expressing and control cell suspensions in exponential phase of growth were treated with the cell wall-degrading enzymes cellulase and pectolyase. In five out of 12 repetitions with three different St7 lines, the protoplast release from St7 cells was faster by up to 30 % compared with the wild-type controls (see example in Supplementary Data Fig. S3). In the remaining cases, the rate of protoplast formation appeared to be similar to that in the wild-type control, but it was never slower. Despite repeated attempts, the factor responsible for variation amongst repetitions and only occasional observation of a difference in protoplast formation was not identified.

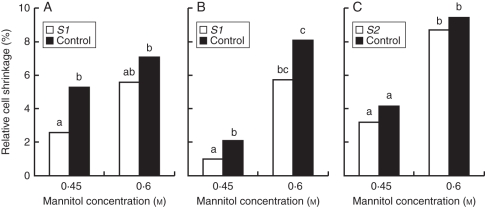

To understand better the mechanism of HyPRP-induced cell expansion, we also tested whether cells over-expressing St7 gene were more or less sensitive to plasmolysis when exposed to a hypertonic solution of 0·6 m mannitol or a near-isotonic solution of 0·45 m mannitol. If HyPRPs (St7) reduce the rigidity of the cell wall, increased elongation would be accompanied with decreased osmotic potential within the cells. If, in contrast, HyPRPs act as linkers between cell wall and plasma membrane, we would expect enhanced resistance to plasmolysis in over-expressing cells. The extent of plasmolysis in individual cells was determined after staining the protoplasts with FDA and the cell walls with calcofluor white (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). The extent of protoplast shrinkage was determined using image analysis software (for details, see Materials and methods). In 0·45 m mannitol, the average frequency of plasmolysed cells in two tested St7 lines was approx. 1·37 times higher than in the wild-type BY-2 line; the ratios between the frequency of plasmolysed cells in St7 and control lines in the three replicate experiments were 52 : 36 %; 32 : 21 % and 34 : 30 %. The extent of protoplast shrinkage measured under both mannitol concentrations was higher in the St7 lines, although the difference was not statistically significant in all repetitions (Fig. 6). As expected, the protoplast shrinkage in both cell lines was higher in the hypertonic solution of 0·6 m mannitol (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Protoplast shrinkage of transgenic and control tobacco BY-2 cells after 10-min exposure to 0·45 m and 0·6 m mannitol. Two lines over-expressing the HyPRP gene St7 are compared with wild-type BY-2 control: (A,B) S1, (B) S2. Protoplast shrinkage was determined by staining the cells with fluorescein diacetate and calcofluor white (Supplementary Data Fig. S1, available online), and using image analysis of the projected areas of the protoplast and the whole cell (details in Materials and Methods). The three graphs represent independent replicates. Data columns indicated by different letters are significantly different at α = 0·05 within the replicate; columns that share the same letter do not differ significantly.

To test the effect of altered medium osmolarity on cell extension further, we cultured a selected HyPRP line (MNt1 line M20) and wild-type tobacco BY-2 line in media supplemented with 7 % sucrose. During the exponential phase of growth, the high sucrose concentration substantially reduced the cell length in both lines when compared with the normal conditions with 3 % sucrose. At the end of the 7-d sub-cultivation interval, MNt1 cells cultured on 7 % sucrose remained significantly shorter by >20 % compared with those on normal media (Mann–Whitney U test; P = 0·00), whereas only a small insignificant difference (P = 0·43) was observed between the length of untransformed cells on media with 7 % and 3 % sucrose. After 9 d of cultivation, about 10 % of MNt1 cells exhibited an anomalous triangular shape on the media with 7 % sucrose, whereas no such cells were observed in the untransformed BY-2 line (Supplementary Data Fig. S4).

Over-expression of HyPRP genes in potato plants

By analogy with the tobacco BY-2 cell lines, potato plants were transformed with the following HyPRP genes: St1 gene with a long N-terminal domain, normally expressed in most organs except mature leaves; modified St1 gene (MSt1) with a deleted proline-rich domain; and St7 gene with a short N-terminal domain expressed preferentially in roots (Dvořáková et al., 2007; Fig. 1). From 10 to 50 transgenic potato lines were obtained after each transformation. Expression of the introduced genes was confirmed in at least ten lines for each transformation by northern hybridization in the case of St1 and by semi-quantitative RT-PCR for MSt1 and St7 genes (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). Nevertheless, detailed morphological analysis, including the height of plants, leaf size and shape, and root architecture, of the transgenic plants did not reveal any visible changes in response to the ectopic over-expression of any of the three genes under the control of the constitutive 35S CaMV promoter.

Since the over-expression of HyPRP genes promoted cell elongation in the BY-2 lines, we measured the length of well-defined root cells in the elongation zone 1 cm away from the root tip of in-vitro-grown potato plants transformed with the MSt1 gene. However, the length of cells in transgenic and control plants did not show significant differences (Supplementary Data Fig. S6).

When no change in the morphological characteristics was detected, there remained the possibility that the expression of introduced genes was compensated for by changes in the expression levels of other genes involved in cell extension, namely, endogenous HyPRP genes, in a way similar to the situation observed in some transgenic tobacco BY-2 lines (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Therefore we analysed the expression of 14 potato HyPRP genes in roots and young leaves of five selected lines with high expression of the introduced genes (Supplementary Data Fig. S7). However, the expression profiles of the HyPRP genes in the transgenic lines and two parallel control plants did not reveal any consistent differences in the transcript levels that would exceed the natural variability of HyPRP gene expression.

DISCUSSION

Over-expression of HyPRP genes is likely to promote elongation of tobacco BY-2 cells

The majority of BY-2 lines transformed with the MNt1, Nt1 or St7 genes exhibited enhanced cell elongation when compared with wild-type BY-2 (Figs 2A, 3 and 4). No such changes were observed in BY-2 lines transformed with an analogous T-DNA carrying the GFP gene, which is regarded not to affect the phenotype of transformed plant materials (Seth and Vierstra, 1998). This indicates that the observed phenotypic changes resulted from HyPRP over-expression and were not related to the transformation and selection procedure per se.

In contrast to our results, Holk and colleagues described enhanced cell expansion in carrot cell cultures with the down-regulated HyPRP gene DC 2·15 and suggested that the protein may be suppressing cell extension (Holk et al., 2002). Since our experiments with over-expression of three different HyPRP genes in BY-2 cells consistently promoted cell elongation, we presume that DC 2·15 either had another specific function or the described phenotypic changes were not directly related to the down-regulated expression of this gene.

Enhanced cell elongation is likely to be the result of cell-wall loosening

The growth of plant cells is generally related to loosening of the cell wall, which allows cell expansion driven by osmotic water uptake (reviewed in Cosgrove, 2005). The enhanced elongation of BY-2 cells over-expressing the HyPRP gene MNt1 was partially compensated for in a medium with increased osmotic potential (7 % sucrose; Supplementary Data Fig. S4), which reduced the osmotic gradient between the medium and the cell and, hence, the driving force required for cell extension. Although the high sucrose treatment most likely had pleiotropic effects, the short-time exposure of BY-2 cells to mannitol provided a more reliable comparison of the cell osmotic potentials. Increased elongation of cells over-expressing HyPRP gene St7 was accompanied by enhanced plasmolysis, indicating a possible reduction in the cell osmotic potential. Furthermore, faster release of protoplasts upon enzymatic digestion in some replications suggested that the cell wall of St7-over-expressing cells may be, at least transiently, thinner or more plastic compared with untransformed BY-2 cells. Based on these results, we propose that the over-expression of HyPRP genes increased the plasticity of the cell wall, thus lowering its ability to resist turgor pressure. Consequently, increased water uptake would increase cell volume and simultaneously reduce the cell osmotic potential.

Loosening of the rigid cell-wall network relies principally on the breaking of hydrogen bonds between cellulose microfibrils and other cell-wall components such as xyloglucans. During acid growth, this loosening is mediated by specialized pH-sensitive non-enzymatic proteins called expansins (reviewed in Cosgrove, 2005). In addition, Nieuwland et al. (2005) demonstrated astonishing participation of non-specific LTPs in pH-independent cell-wall loosening. In contrast to the effect of expansins, expansion of hypocotyls induced by tobacco TobLTP2 remained logarithmic in time, indicating that LTPs do not initiate new pathways for cell-wall extension but rather facilitate the ongoing extension process (Nieuwland et al., 2005). The presence of an LTP-like 8CM domain in HyPRPs suggests that the mode of HyPRP action is likely to be similar to that observed in LTPs.

The presence of a hydrophobic 8CM-containing domain and a hydrophilic proline-rich domain within a single molecule of a typical HyPRP inspired researchers to suggest that HyPRPs may participate in interconnections between the hydrophobic plasma membrane and the hydrophilic cell wall in a manner similar to glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored arabinogalactan proteins (Seifert and Roberts, 2007) or signal-transducing wall-asociated kinases that are involved in many morphogenetic processes including cell expansion (Decreux and Messiaen, 2005). Hypothetical reinforcement of the wall-membrane interconnections by HyPRPs was suggested to protect cells against plasmolysis under environmental stresses (Deutch and Winicov, 1995; Goodwin et al., 1996). In contrast to this hypothesis, we observed a higher tendency for plasmolysis in cells over-expressing the HyPRP gene St7. Thus the protection against environmental stresses mediated by HyPRPs may have a different mode of action, e.g. scavenging of ROS by cysteine residues as suggested by Zhang and Schläppi (2007). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that HyPRPs do indeed interact with both the cell wall and the plasma membrane, the interaction is unlikely to have a significant mechanical function in keeping the two structures in near proximity.

Cell expansion is likely to be mediated by the C-terminal 8CM domain of HyPRP

Over-expression of all three HyPRP genes in tobacco BY-2 cells resulted in enhanced cell elongation, with non-significant differences among the genes with different N-terminal domains (Fig. 4). Therefore the facilitation of cell elongation was probably connected with the C-terminal 8CM domains. The mechanism of HyPRP action might be similar to that described for LTPs. The hydrophobic pocket localized inside the 8CM domain of LTPs was suggested to interact with unknown hydrophobic molecule(s) in the cell wall; the charged complex might interrupt hydrogen bonds between celluloses and hemicelluloses, leading to non-hydrolytic loosening of these cross-links (Nieuwland et al., 2005).

HyPRPs, similarly to expansins, consist of two dissimilar domains, although there is no sequence homology between the two protein families. The functional (putative catalytic) domain of expansins mediates disruption of hydrogen bonds in the cell wall, whereas the binding domain allows interactions with cellulose microfibrils. Since the N-terminal domains of HyPRPs are unlikely to be involved in cell-wall loosening, theoretically they may play a role similar to that of the binding domains of expansins, which prevent diffusion of the protein to the walls of neighbouring cells (Cosgrove, 2000). The N-terminal proline-rich domains of HyPRPs may interact with other components of the cell wall in various ways that were already hypothesized in Dvořáková et al. (2007), but experimental data are missing. The N-terminal domains of Nt1 and St1 contain AP, SP and TP dipeptides. These motives are typically associated with arabinogalactan proteins and are glycosylated with arabinogalactan polysaccharides (Showalter et al., 2010) that could mediate multiple interactions with other cell-wall components. Lys-Pro motifs of some HyPRPs may interact with acid cell-wall polymers such as pectins (Kieliszewski and Lamport, 1994). Serine- and threo9-rich sequences may allow the formation of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of these amino acids. N-terminal domains with high content of hydrophobic and aliphatic amino acids may participate in the formation of hydrophobic interactions as already hypothesized in Dvořáková et al. (2007). Some HyPRP may be also covalently cross-linked with other proline- or hydroxyproline-rich proteins through amino acid motifs Val-Tyr-Pro-Lys or Val-Pro-Tyr-Lys (present in St1 and Nt1 proteins), which are closed to the Pro-Val-Tyr-Lys motif present in some extensins where such motifs are supposed to participate in intermolecular cross-linking (De Loose et al., 1991; Kieliszewski and Lamport, 1994). The type of N-terminal domain interaction is likely to be based mainly on its amino acids composition and motifs (see detailed overview of the whole HyPRP family in Dvořáková et al., 2007). Through different types of interaction, the N-terminal domains may theoretically also participate in fine-tuning of the cell-wall extension processes under different conditions or in different cell types.

Cell elongation induced by HyPRP over-expression may be compensated in planta

In contrast to BY-2 cell lines, no phenotypic changes were observed in potato plants over-expressing any of the three HyPRP genes MSt1, St1 or St7. The lack of phenotypic changes may simply indicate that HyPRP levels are not the limiting factor in cell elongation in planta. Alternatively, enhanced HyPRP levels could induce compensatory or feedback regulation, which is generally believed to play an important role in cell-wall function (Humphrey et al., 2007). The complexity of the plant body is much higher compared with the artificial system of individually growing tobacco BY-2 cells or cell files. In line with our observation, there is no report documenting changes in the cell length in intact plants over-expressing LTP genes; enhanced elongation was only observed in some cell clusters of the spruce embryogenic culture over-expressing the LTP gene Pa18 (Sabala et al., 2000). Stronger compensatory mechanisms may have lead to effective suppression of undesirable cell expansion in the complex plant body. Such control of cell expansion probably involved players other than HyPRP family members because no direct compensation was observed at the expression levels of any of the 14 HyPRP genes analysed.

CONCLUSIONS

Detailed analysis of tobacco BY-2 cells over-expressing HyPRP genes with different types of N-terminal domains suggests that C-terminal domains of HyPRPs are involved in cell-wall loosening, thus allowing cell expansion/elongation. The absence of visible phenotypic alterations in HyPRP-over-expressing potato plants indicates the presence of compensatory mechanisms ensuring proper cell expansion in planta. The mechanism of how HyPRPs act as well as the precise localization of HyPRPs in the cell wall needs further investigation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Jan Marc for language corrections and two anonymous reviewers for suggesting several smart improvements of the manuscript. Funding was provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (LC06004, LC06034, and MSM0021620858) and the Grant Agency of Charles University in Prague (136510).

LITERATURE CITED

- Blanco-Portales R, López-Raéz JA, Bellido ML, et al. A strawberry fruit-specific and ripening-related gene codes for a HyPRP protein involved in polyphenol anchoring. Plant Molecular Biology. 2004;55:763–780. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-1966-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S, Brown S, Satiat-Jeunemaitre B. The N-myristoylated Rab-GTPase m-Rab(mc) is involved in post-Golgi trafficking events to the lytic vacuole in plant cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:943–954. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton S, Viau L, Lelièvre E, Limami AM. A gene encoding a protein with a proline-rich domain (MtPPRD1), revealed by suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH), is specifically expressed in the Medicago truncatula embryo axis during germination. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:825–832. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Loosening of plant cell wall by expansins. Nature. 2000;407:321–326. doi: 10.1038/35030000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nature Reviews. 2005;6:850–861. doi: 10.1038/nrm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblaere R, Bytebier B, Degreve H, et al. Efficient octopine Ti plasmid-derived vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated gene-transfer to plants. Nucleic Acids Research. 1985;13:4777–4788. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.13.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux A, Messiaen J. Wall-associated kinase WAK1 interacts with cell wall pectins in a calcium-induced conformation. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2005;46:268–278. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Loose M, Gheysen G, Tire C, et al. The extensin signal peptide allows secretion of a heterologous protein from protoplasts. Gene. 1991;99:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90038-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch Ch, Winicov I. Post-transcriptional regulation of a salt-inducible alfalfa gene encoding a putative chimeric proline-rich cell wall protein. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;27:411–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00020194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietze J, Blau A, Willmitzer L. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of potato (Solanum tuberosum) In: Potrykus I, Spangenberg G, editors. Gene transfer to plants. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Drenth J, Low BW, Richardson JS, Wright CS. The toxin-agglutinin fold: a new group of small protein structures organized around a four-disulfide core. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1980;255:2652–2655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvořáková L, Cvrčková F, Fischer L. Analysis of the hybrid proline-rich protein families from seven plant species suggests rapid diversification of their sequences and expression patterns. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:412. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-412 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L, Lovas A, Opatrný Z, Bánfalvi Z. Structure and expression of a hybrid proline-rich protein gene in the Solanaceous species, Solanum brevidens, Solanum tuberosum and Lycopersicum esculentum. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2002;159:1271–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Gaisteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, et al. In: Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server: the proteomics protocols handbook. Walker JM, editor. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Gincel E, Simorre JP, Caille A, Marion D, Ptak M, Vovelle F. Three-dimensional structure in solution of a wheat lipid-transfer protein from multidimensional 1H-NMR data: a new folding for lipid carriers. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1994;226:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin W, Pallas JA, Jenkins GI. Transcripts of a gene encoding a putative cell wall-plasma membrane linker protein are specifically cold-induced in Brassica napus. Plant Molecular Biology. 1996;31:771–781. doi: 10.1007/BF00019465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C-Y, Zhang J-S, Chen S-Y. A soybean gene encoding a proline-rich protein is regulated by salicylic acid, an endogenous circadian rhythm and by various stresses. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holk A, Klumpp L, Scherer GFE. A cell wall protein down-regulated by auxin suppressed cell expansion in Daucus carota (L.) Plant Molecular Biology. 2002;50:295–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1016052613196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey TV, Bonetta DT, Goring DR. Sentinels at the wall: cell wall receptors and sensors. New Phytologist. 2007;176:7–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Puigdomènech P. Plant cell wall glycoproteins and their genes. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2000;38:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Ruiz-Avila L, Puigdomènech P. A maize embryo-specific gene encodes a proline-rich and hydrophobic protein. The Plant Cell. 1992;4:413–423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Gomis-Rüth FX, Puigdomènech P. The eight-cysteine motif, a versatile structure in plant proteins. Plant Physiology Biochemistry. 2004;42:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski MJ, Lamport DTA. Extensin: repetitive motifs, functional sites, post-translation codes and phylogeny. The Plant Journal. 1994;5:157–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.05020157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsmayer EM, Skoog F. Organic growth factor requirements of tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1965;18:100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Nemoto Y, Hasezawa S. Tobacco BY-2 cell line as the “HeLa” cell in the cell biology of higher plants. International Review of Cytology. 1992;132:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwland J, Feron R, Huisman BAH, et al. Lipid transfer proteins enhance cell wall extension in tobacco. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2009–2019. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocarova E, Fischer L. Cloning of transgenic tobacco BY-2 cells: an efficient method to analyze and reduce high natural heterogeneity of transgene expression. BMC Plant Biology. 2009;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-9-44 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyanka B, Sekhart K, Reddy VD, Rao KV. Expression of pigeonpea hybrid-proline-rich protein encoding gene (CcHyPRP) in yeast and Arabidopsis affords multiple abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2010;8:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabala I, Elfstrand M, Farbos I, Clapham D, von Arnold S. Tissue-specific expression of Pa18, a putative lipid transfer protein gene, during embryo development in Norway spruce (Picea abies) Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;42:461–478. doi: 10.1023/a:1006303702086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM, Keppler B, Lichtenberg J, Gu D, Welch LR. A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:485–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert GJ, Roberts K. The biology of arabinogalactan proteins. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2007;58:137–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth JD, Vierstra RD. Soluble, highly fluorescent variants of green fluorescent protein (GFP) for use in higher plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 1998;36:521–528. doi: 10.1023/a:1005991617182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shure M, Wessler S, Fedoroff N. Molecular-identification and isolation of the waxy locus in maize. Cell. 1983;35:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiekema WJ, Heidekamp F, Dirkse WG, et al. Molecular-cloning and analysis of 4 potato-tuber messenger-RNAs. Plant Molecular Biology. 1988;11:255–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00027383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJ, Barre A, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. Potato lectin: an updated model of a unique chimeric plant protein. The Plant Journal. 2004;37:34–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H-M, Zou J, May B, Gu Q, Cheung AY. A tobacco gene family for flower cell wall proteins with a proline-rich and cysteine-rich domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:6829–6833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeats TH, Rose JKC. The biochemistry and biology of extracellular plant lipid-transfer proteins (LTPs) Protein Science. 2008;17:191–198. doi: 10.1110/ps.073300108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang I, Schläppi M. Cold responsive EARLI1 type HyPRPs improve freezing survival of yeast cells and form higher order complexes in plants. Planta. 2007;227:233–243. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.