Abstract

Background and Aims

Molecular-based studies of thermotolerance have rarely been performed on wild plants, although this trait is critical for summer survival. Here, we focused on thermotolerance and expression of heat shock transcription factor A2 (HSFA2) and its putative target gene (chloroplast-localized small heat shock protein, CP-sHSP) in two allied aquatic species of the genus Potamogeton (pondweeds) that differ in survival on land.

Methods

The degree of thermotolerance was examined using a chlorophyll bioassay to assess heat injury in plants cultivated under non- and heat-acclimation conditions. Potamogeton HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes were identified and their heat-induction was quantified by real-time PCR.

Key Results

The inhibition of chlorophyll accumulation after heat stress showed that Potamogeton malaianus had a higher basal thermotolerance and developed acquired thermotolerance, whereas Potamogeton perfoliatus was heat sensitive and unable to acquire thermotolerance. We found two duplicated HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes in each species. These genes were induced by heat shock in P. malaianus, while one HSFA2a gene was not induced in P. perfoliatus. In non-heat-acclimated plants, transcript levels of HSFA2 and CP-sHSP were transiently elevated after heat shock. In heat-acclimated plants, transcripts were continuously induced during sublethal heat shock in P. malaianus, but not in P. perfoliatus. Instead, the minimum threshold temperature for heat induction of the CP-sHSP genes was elevated in P. perfoliatus.

Conclusions

Our comparative study of thermotolerance showed that heat acclimation leads to species-specific changes in heat response. The development of acquired thermotolerance is beneficial for survival at extreme temperatures. However, the loss of acquired thermotolerance and plasticity in the minimum threshold temperature of heat response may be favourable for plants growing in moderate habitats with limited daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations.

Keywords: Acquired thermotolerance, chloroplast-localized small heat shock protein (CP-sHSP), gene duplication, heat stress, heat acclimation, heterophylly, geographical distribution, heat shock transcription factor A2 (HSFA2), minimum threshold temperature, pondweed, Potamogeton

INTRODUCTION

High temperature is a major factor limiting plant growth and survival in the field. Thus, organisms respond to temperature elevations immediately by synthesizing various heat shock proteins (HSPs) that act as molecular chaperones to prevent and repair cell damage and maintain homeostasis (Vierling, 1991). Beyond an inherent basal thermotolerance, many organisms acquire thermotolerance after short-term exposure to sub-lethal high temperatures or long-term mild heat stress (Yarwood, 1961; Lin et al., 1984). There is a strong positive correlation between the acquisition of thermotolerance and accumulation of HSPs (Vierling, 1991; Koskull-Döring et al., 2007).

The heat shock response is regulated primarily by the heat shock transcription factor (HSF) family (Schöffl et al., 1998; Baniwal et al., 2004). HSFs bind sequences called heat shock elements (HSEs) in the promoter regions of HSP genes and other heat-inducible genes. The HSE consists of at least three contiguous inverted repeat sequences (nGAAn, nGnAn or nGAnn) (Amin et al., 1988; Schöffl et al., 1998). Plants have more than 20 HSF family members, compared with four in vertebrates and just one in Drosophila and yeast (Nover et al., 2001; Baniwal et al., 2004). Within the HSF family, heat shock transcription factor A2 (HSFA2) expression is most strongly induced by heat stress in tomato and Arabidopsis (Busch et al., 2005; Miller and Mittler, 2006; Koskull-Döring et al., 2007). Five Os-HSFA2 genes are known in rice (Oryza sativa L.), and an analysis of their expression has just begun (Yokotani et al., 2008; Mittal et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). Only one HSFA2 is present in tomatoes (Solanum peruvianum L., Sp-HSFA2) and Arabidopsis thaliana L. (At-HSFA2) (Baniwal et al., 2004). Sp-HSFA2 is induced by Sp-HSFA1, which forms hetero-oligomeric complexes that function in thermotolerance (Scharf et al., 1998; Mishra et al., 2002). Schramm et al. (2006) demonstrated that HSFA2 is the regulator of a subset of stress response genes in Arabidopsis. The At-HSFA2 knockout mutant showed substantially decreased basal and acquired thermotolerance, while the overexpressing mutant displayed increased tolerance (Li et al., 2005; Ogawa et al., 2007). Charng et al. (2007) demonstrated that At-HSFA2 is essential for sustained HSP expression, but not for initial induction of the heat-shock response. Although HSFA2 plays an important role in thermotolerance, it has rarely been examined in plants under natural conditions. Molecular-based wild plant studies of thermotolerance have been performed on chloroplast-localised small HSPs (CP-sHSP), which play a role in thermotolerance by protecting heat-labile components of photosystem II (Joshi et al., 1997; Downs et al., 1998; Barua et al., 2003). Moreover, inter- and intraspecific variation in heat-accumulation of CP-sHSPs is positively correlated with the degree of thermotolerance (Ceanothus, Knight and Ackerly, 2001; Chenopodium, Barua et al., 2003; bentgrass, Wang and Luthe, 2003).

Potamogeton (pondweed) is the largest aquatic monocot genus, with approx. 100 species distributed worldwide (Wiegleb, 1988; Wiegleb and Kaplan, 1998). This genus includes two contrasting ecological groups: homophyllous taxa that are always totally submerged, and heterophyllous amphibious taxa that grow primarily in submerged conditions but can survive temporarily on land in a terrestrial form (Iida et al., 2004, 2009). The structure of the terrestrial leaves is similar to that of land plants, while the submerged leaves have only three cell layers and lack differentiation of the stomatal, cuticle and mesophyll layers (Iida et al., 2007). Many environmental factors, including drought, photoperiod and temperature, affect heterophyllous leaf formation in aquatic plants (reviewed by Wells and Pigliucci, 2000). We conducted drought experiments (water table depth was lowered from 30 cm and maintained 4 cm below the soil face for 4 weeks) under natural summer conditions using two Potamogeton species and their natural reciprocal hybrids from Lake Biwa, Japan. The heterophyllous species Potamogeton malaianus and its maternal hybrid exhibited higher survival rates on land compared with the homophyllous species P. perfoliatus and its maternal hybrid (Iida et al., 2007). The geographical distribution of the two parental plants varies in temperature range; P. perfoliatus tends to grow in cooler climates than P. malaianus (Kadono, 1982). Because plants grown in cooler environments tend to have a limited potential for acclimation to high temperature (Berry and Björkman, 1980), we suspected that the ability to survive on land may depend on the physiological and genetic response to heat levels.

Here, two Potamogeton species with different degrees of survival on land were subjected to comparative physiological and genetic studies of thermotolerance. Cultivation and heat-stress treatment under submerged conditions indicated that unlike heat-tolerant P. malaianus, P. perfoliatus has lower thermotolerance and lacks obvious acquired thermotolerance. Further analysis of HSFA2 and its putative target gene CP-sHSP revealed that two plants developed species-specific changes in heat response during heat acclimation cultivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials and growth conditions

Two pondweed species were collected from several localities in Japan: Potamogeton malaianus Miq. from Lake Biwa (35°7′N, 135°55′E) and Lake Inba (35°44′N, 140°11′E) and P. perfoliatus L. from Lake Biwa, Lake Suwa (36°2′N, 138 °5′E) and Lake Abashiri (43 °6′N, 144 °1′E, brackish water). The plants were maintained and propagated vegetatively from rhizomes in experimental ponds at Kobe University. Winter buds (turions) were harvested in early spring.

Ten winter buds from plants collected from Lake Biwa were transplanted to each basket (W × L × H = 15 × 30 × 15 cm). The baskets were transferred to circulating water tanks (W × L × H = 30 × 60 × 30 cm) and pre-cultivated for 2 months at 25 °C under a 14-h photoperiod with a light intensity of 40 µmol m−2 s−1 (measured at 5-cm water depth). After this initial phase, only the water temperature was changed: non-acclimation conditions (C25: constant 25 °C) or heat-acclimation conditions (A30: alternating 25/30 °C to simulate repeated summer night-time cooling and daytime heating near the water surface, and C30: constant 30 °C) (Supplementary Data Fig. S1, available online).

Chlorophyll bioassay

The degree of thermotolerance was examined using a chlorophyll bioassay (Burke, 1994). Submerged shoots cultivated for 20 d under non-acclimation conditions (C25: constant 25 °C) or heat-acclimation conditions (A30: alternating 25/30 °C and C30: constant 30 °C) were harvested at 0900 h (before the daily temperature elevation under the A30 conditions). They were subjected to a 24-h heat-shock treatment (30, 35, 40 or 45 °C) or no heat treatment (25 °C) in a water bath under a 14-h photoperiod. Immediately thereafter, four leaf discs (diameter 6 mm) were cut from the centre of a submerged leaf and immersed in 100 µL methanol (100 %) at 4 °C overnight in the dark. Using the method of Lichtenthaler (1987), the total chlorophyll content of the methanol extract was calculated as follows from spectrophotometric measurements: Total chlorophyll (μg mL−1) = 1·44 × Absorbance at 665 nm + 24·93 × Absorbance at 652 nm. The change in leaf chlorophyll content (μg cm−2) was compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA); differences between treatments were assessed with Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) test at P = 0·05.

PCR amplification and sequence analysis

Total DNA was isolated as described by Iida et al. (2004). Total RNA isolation and DNA digestion were performed using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit and RNase-Free DNase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, except for the addition of polyethylene glycol 20 000 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) to the extraction buffer (Gehrig et al., 2000). Total RNA (10 µg) was reverse-transcribed using a First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan).

To obtain partial sequences of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes in Potamogeton, PCR was performed using heat shock-treated Potamogeton cDNA (150 ng). Universal primers were designed that target conserved regions in diverse plant species. The primer sequences and annealing temperatures are shown in Supplementary Data Table S1. The transcription start site for HSFA2 was identified by 5′-RACE PCR using Potamogeton-specific primers. Next, using genomic DNA (15 ng) and Potamogeton-specific primers, HSFA2 and CP-sHSP sequences were determined by thermal asymmetric interlaced (TAIL)-PCR (Liu and Whittier, 1995). The amplified products were either sequenced directly or cloned using Target CloneTM (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Sequence analysis was performed using an ABI 3130 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems) with a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (v. 3·1). Multiple sequence alignments and the construction of a phylogenetic tree (neighbour-joining method based on Kimura's two-parameter model) were performed using MEGA version 4·0 (Tamura et al., 2007).

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis

Submerged shoots cultivated for 20 d under C25 and A30 conditions were harvested at 0900 h and subjected to heat-shock treatment (water temperature of 30, 35 or 40 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 h) under light conditions. Leaves were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until further use. Isolated total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo). Diluted cDNA was used for PCR (20 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 60 s at 72 °C; 35 cycles for HSFA2a and 30 cycles for all others) using gene-specific primers (Supplementary Data Table S1).

Real-time PCR of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes was performed using the PCR Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System (Takara). Each PCR reaction contained Thunderbird qPCR Mix (Toyobo), 5 pmol of each primer and a 1 : 10 dilution of cDNA in a final volume of 25 µL. Primer sequences for quantitative PCR are shown in Supplementary Data Table S2. The following amplification programme was used: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, 40 cycles of PCR at 95 °C for 5 s followed by 60 °C for 20 s. Melting curve analysis was completed at 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 15 s and 95 °C for 15 s. A standard curve for each target gene was generated from a dilution series constructed from PCR fragments. The quantity of cDNA was calculated by the second derivative maximum method, and relative quantification of HSFA2 and CP-sHSP expression was normalized using actin mRNA as an internal control.

RESULTS

Comparison of the degree of thermotolerance

Thermotolerance (heat stress injury) in many plant species has been indicated by the temperature sensitivity of chlorophyll synthesis and accumulation, which is quantified as the change in chlorophyll content (chlorophyll bioassay; Burke, 1994, 1998; Tewari and Tripathy, 1999; Burke et al., 2000; O'Mahony et al., 2000). We examined thermotolerance in plants cultivated for 20 d under non-acclimation (C25) and heat-acclimation (A30 and C30) conditions by chlorophyll bioassay. Basal thermotolerance was examined after the heat treatment of C25 plants, because the plants were exposed to heat stress only once. Heat treatment of A30 and C30 plants was also carried out to analyse acquired thermotolerance.

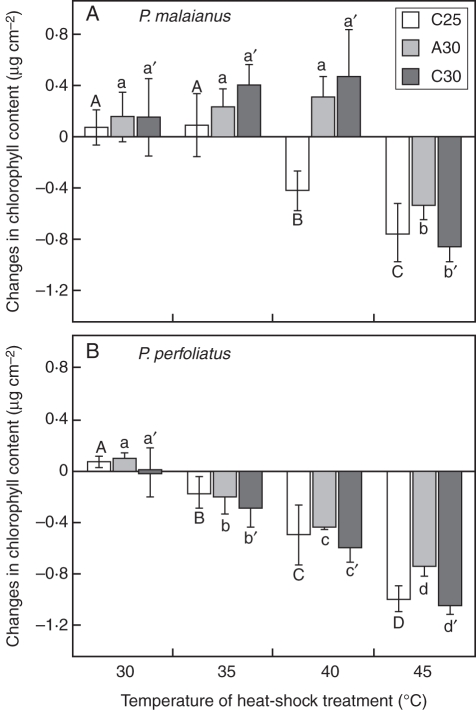

Temperature had a significant effect on chlorophyll content in the two species cultivated under non-acclimation C25 and heat-acclimation A30 and C30 conditions for 20 d (ANOVA, P < 0·0001 for each condition). In P. malaianus, the chlorophyll content of the C25 plants was maintained at the control level (chlorophyll content of non-heated C25 leaves: 2·09 ± 0·10 µg cm−2) at 30 and 35 °C (Fig. 1A). However, the values observed at 40 and 45 °C were lower than those of the control plants, indicating that chlorophyll accumulation was inhibited by heat stress above 35 °C. The chlorophyll content of A30 and C30 was maintained at the control level (non-heated, A30: 1·79 ± 0·14 µg cm−2 and C30: 2·04 ± 0·16 µg cm−2) at 30–40 °C, but declined at 45 °C. The maximum temperature that allowed chlorophyll accumulation shifted from 35 to 40 °C after long-term acclimation. In contrast, the chlorophyll content followed the same pattern in P. perfoliatus cultivated under the three conditions, i.e. it was maintained at the control level (non-heated, C25: 1·86 ± 0·06 µg cm−2, A30: 1·69 ± 0·10 µg cm−2 and C30: 2·27 ± 0·32 µg cm−2) at 30 °C, but was lowered by heat treatment above 35 °C (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Thermotolerance of Potamogeton species examined by chlorophyll bioassay. The change in chlorophyll content was used as an index of thermotolerance, which is calculated as the chlorophyll content of submerged, heat-treated leaves (water at 30–45 °C, 24 h) minus that of non-heated leaves (at 25 °C, control). Heat-stress injury in plants is indicated by the reduction of chlorophyll content. (A) P. malaianus cultivated under non-acclimation (C25: constant 25 °C) conditions was injured by heat shock above 40 °C, while plants cultivated under heat-acclimation (A30: alternating 25/30 °C and C30: constant 30 °C) conditions survived 40 °C heat shock. (B) P. perfoliatus cultivated under both non-acclimation and heat-acclimation conditions was injured by heat shock above 35 °C. Bars indicate the means of five replicates ± s.d. Columns with the same upper-case and lower-case letters are not significantly different at P < 0·05 in temperature series comparisons (Fisher's PLSD).

These results indicate that P. perfoliatus had a lower basal thermotolerance than P. malaianus. Due to the heat-acclimation cultivation, P. malaianus acquired some degree of thermotolerance, while no acquired thermotolerance was detected in P. perfoliatus.

Identification of duplicated HSFA2a genes in Potamogeton

We determined the nucleotide sequences of the promoter and coding regions of HSFA2 in Potamogeton by genomic PCR. Several HSFA2 sequences were obtained from each species of Lake Biwa plants (GenBank accession numbers AB605342–AB605348; Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Two molecular species were identified in both plants. Based on the sequence similarity and tetraploid nature of the plants examined (Harada, 1955), the two sequences were derived from allelic HSFA2 genes, namely HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2. Three sequences obtained from P. malaianus were identified as two variants of Pm-HSFA2a1 and a single Pm-HSFA2a2. Four sequences from P. perfoliatus corresponded to two variants of Pp-HSFA2a1 and Pp-HSFA2a2, respectively. Because there was very little sequence divergence (similarity >99 %) between the HSFA2 variants (Supplementary Data Table S2), hereafter the sequences obtained from P. malaianus (Pm-HSFA2a1-1 and Pm-HSFA2a2) and P. perfoliatus (Pp-HSFA2a1-1 and Pp-HSFA2a2-1) are referred to as representative sequences of HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2 in each species.

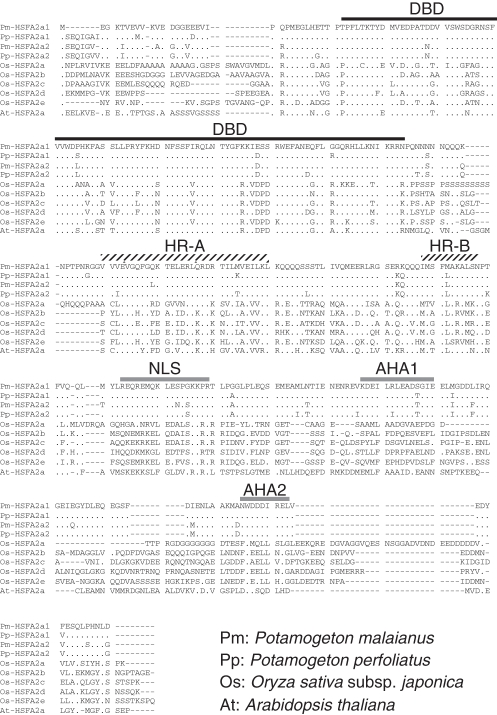

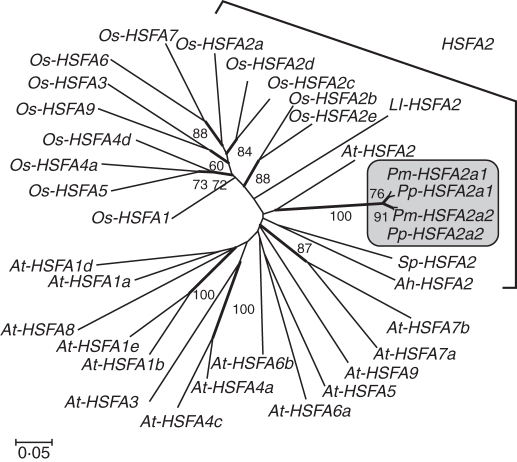

The coding sequence of HSFA2 was interrupted by a single intron (256–258 bp) (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2 showed high sequence similarity in their coding and intron regions (>95 %, Supplementary Data Table S2). The deduced amino acid sequences contained conserved modules, which are typical of HSFA2 (Fig. 2). There were 28–33 amino acid substitutions (90–92 % homology) and 11 of them varied between the two HSFA2 genes. We constructed a phylogenetic tree using the nucleotide sequence of the DNA-binding domain (Fig. 3). Although the amino acid sequence similarity was relatively high (84–66 %) among HSFA2 from different plant families, they did not form a clade in the DNA sequence-based tree. The two Potamogeton HSFA2 genes formed a monophyletic clade with high bootstrap support, and the short branch lengths indicate that HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2 arose via a recent duplication event.

Fig. 2.

Multiple alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of duplicated HSFA2 from P. malaianus (Pm-HSFA2a1 and Pm-HSFA2a2) and P. perfoliatus (Pp-HSFA2a1 and Pp-HSFA2a2). Conserved structures of a class A-HSF are indicated. DBD, DNA-binding domain; HR-A/B, oligomerization domains; NLS, nuclear localization signal; AHA1 and AHA2, functional motifs (aromatic, hydrophobic and acidic amino acids). Amino acids identical to Pm-HSFA2a1 are shown as dots (.); gaps are indicated by a dash (-).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of HSFA genes based on the nucleotide sequence of the DNA-binding domain. Duplicated HSFA2 from P. malaianus (Pm-HSFA2a1 and Pm-HSFA2a2) and P. perfoliatus (Pp-HSFA2a1 and Pp-HSFA2a2) form a monophyletic clade with high bootstrap support based on 1000 replicates. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ah, Arachis hypogaea; Ll, Lilium longiflorum; Os, Oryza sativa subsp. japonica; Sp, Solanum peruvianum. The GenBank accession numbers for the genes are shown in Supplementary Data Table S3.

HSE motifs in the promoter regions of the HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2 genes

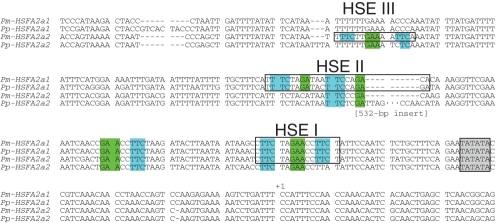

An analysis of the sequence 300–800 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site in Potamogeton HSFA2 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Data Fig. S3) revealed that, compared with the coding regions, the two HSFA2 genes were relatively different in their promoter sequences (86–89 % similarity; Supplementary Data Table S2). Because HSF binding sites are required for the transcription of heat-inducible genes (Amin et al., 1988; Xiao and Lis, 1988; Schöffl et al., 1998), we identified active HSE motifs as palindromic repeats of the head and tail modules, according to Nover et al. (2001).

Fig. 4.

HSE module of duplicated HSFA2 in Potamogeton. Three HSEs (open box), a TATA box (grey box) and the transcriptional start site (+1) are presumed to be within the promoter regions of HSFA2a1 and HSFA2a2 in P. malaianus and P. perfoliatus. Core consensus sequence head (nGAAn, nGAnn or nGnAn) and tail (nTTCn, nnTCn or nTnCn) modules in the active HSE are highlighted on a green or blue background, respectively. Active HSE motifs (palindromic repeats of the head and tail modules) were identified according to Nover et al. (2001). In the Pp-HSFA2a2 promoter, there is no perfect match to the HSE consensus sequences, and a long insertion is located within the HSE II region (532 bp: highlighted on a grey background).

Four active HSE motifs were found in the promoter region (Fig. 4). Three of these motifs (HSE I, II, III) consisted of three or four contiguous inverted repeat sequences that efficiently bound HSFs (Lee et al., 1995; Mishra et al., 2002). Except for Pp-HSFA2a2, HSE I was conserved proximal to the putative TATA box within Potamogeton HSFA2 genes. Additional HSE II motifs (four contiguous inverted repeat sequences) were present in HSFA2a1, but the core sequence (nGAnn) was changed to nCAnn in HSFA2a2. Instead, HSE III (three contiguous inverted repeat sequences) was found in Pm-HSFA2a2. Due to nucleotide substitutions, the two HSEs observed in Pm-HSFA2a2 appeared to be inactive in P. perfoliatus. Specifically, the HSE sequences of Pp-HSFA2a2 (nTTCn) were changed to nTTAn in the HSE I region and to nTTTn in the HSE III region. Furthermore, Pp-HSFA2a2 contained a long insertion (532 bp) in the HSE II region. The insertion sequence was AT-rich (73 %) and conserved in HSFA2a2 of P. perfoliatus from different locations (Supplementary Data Fig. S4). There were no characteristic structures, such as HSEs or transposable elements. The HSE distribution patterns were conserved in plants of each species collected from other localities (Supplementary Data Fig. S3).

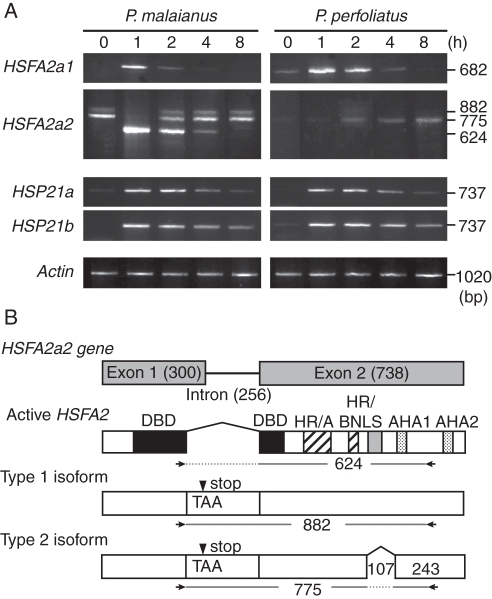

Loss of active HSFA2a2 transcript in heat-sensitive P. perfoliatus

Submerged leaves from C25 plants were subjected to heat shock at a water temperature of 35 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 h (Fig. 5). We obtained either a single HSFA2a1 transcript or three spliced isoforms of HSFA2a2 from RT-PCR. Sequence analysis revealed that the shortest HSFA2a2 transcript (624 bp; active HSFA2a in Fig. 5B) in P. malaianus was identical to the expected mRNA sequence of the properly spliced product, like that of HSFA2a1. In P. perfoliatus, the properly spliced HSFA2a1 transcripts were strongly induced 1 h after heat shock. However, active HSFA2a2 transcripts were absent (Fig. 5A). Prediction of the promoter region (Fig. 4) suggested that subsequent nucleotide substitutions, together with insertion events, may be responsible for the loss of HSFA2a2 heat induction in P. perfoliatus. Further promoter assay and DNA binding studies are necessary to understand thoroughly the loss of Pp-HSFA2a2 expression.

Fig. 5.

Expression of duplicated HSFA2 (HSFA2a1, HSFA2a2) and CP-sHSP (HSP21a, HSP21b) in Potamogeton cultivated under non-acclimation conditions (C25: constant 25 °C). (A) RT-PCR analysis of submerged leaves during heat-shock treatment (water temperature at 35 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 h). Active transcripts of the examined genes were induced by the treatment, except for HSFA2a2 in P. perfoliatus. For HSFA2a2, a 624-bp transcript was found to be the active transcript, while the 882- and 775-bp transcripts were spliced isoforms. Actin served as a loading control. (B) Structures of alternatively spliced HSFA2a2 isoforms (Type 1 and Type 2). Active HSFA2 transcripts have properly spliced mRNA sequences. Both isoforms retain an intron that includes a premature stop codon (arrowhead). The Type 2 isoform has the same structure as the Type 1, except for a 107-bp deletion in the middle of exon 2. Arrows indicate the positions of the primers used for gene-specific amplification (477C and 1320 in Supplementary Data Table S1). Numbers show the length (bp) of specific regions.

Two HSFA2a2 isoforms, Type 1 and Type 2, have premature stop codons and are classified as intron retentions (Fig. 5B), which are common in plant alternative splicing events (Wang and Brendel, 2006). The Type 1 HSFA2a2 isoform observed in P. malaianus was identical to active HSFA2a2 transcripts, except that the intron was retained, and therefore may exist in the pre-spliced state. The Type 2 isoforms were characterized by a 107-bp deletion in the middle of exon 2 (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Data Fig. S2). In Arabidopsis HSFA2, an alternatively spliced form with a premature stop codon was produced and degraded through non-sense-mediated mRNA decay, suggesting post-transcriptional regulation of the active form (Sugio et al., 2009). The Type 2 isoform may also be regulated through such mechanisms.

Identification of the HSFA2 gene target, CP-sHSP

To investigate the effects of HSFA2 expression, we identified the chloroplast-localized small heat shock protein (CP-sHSP), a gene target of HSFA2 regulation during heat stress (Downs et al., 1998; Nishizawa et al., 2006). Two CP-sHSP genes, namely HSP21a and HSP21b, were identified in both species (accession numbers: AB594809–AB594812). Nucleotide sequence similarities were high between the two Potamogeton CP-sHSP genes. The coding region overall (738 bp) had 95 % similarity, while the 5′-untranslated region and promoter region (762 bp) had 93 % similarity, indicating that they were paralogous and derived from a gene duplication event. The amino acid sequences of the Potamogeton CP-sHSP genes resembled those of Arabidopsis and other plant species (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). They were composed of a chloroplast transit peptide and three consensus regions, namely region I and II (in the α-crystallin domain) and the methionine-rich region (region III), which is characteristic of CP-sHSP (Waters and Vierling, 1999). Excluding the transit peptide sequence, amino acid sequences were relatively conserved between the two genes (95 % homology). All examined CP-sHSP genes contained HSE sequence motifs (nGAAnnnTCnnGnAn) approximately 94 bp upstream from the putative TATA box, and were expressed during heat shock at 35 °C (Fig. 5).

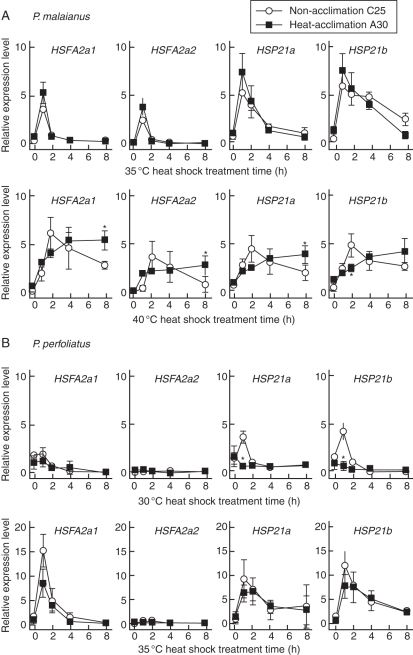

Heat-stress response of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes

To compare heat-stress responses, HSFA2 (HSFA2a1, HSFA2a2) and CP-sHSP (HSP21a, HSP21b) transcript levels were measured by real-time PCR. Non-heat-acclimated (C25) and heat-acclimated (A30) Potamogeton plants were subjected to heat-shock treatment at 30, 35 or 40 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 h (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Heat-stress response of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes in Potamogeton. Plants cultivated under non-acclimation (C25: constant 25 °C) and heat-acclimation (A30: alternating 25/30 °C) conditions were subjected to heat shock (0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 h). The expression levels of transcripts were determined using real-time PCR, and normalized to that of Actin (= 1). Significant differences between non-heated and heat-acclimated plants (asterisks) are observed at 40 °C in heat-tolerant P. malaianus (A) and at 30 °C in heat-sensitive P. perfoliatus (B) (P < 0·05, t-test for each comparison). Data are expressed as the mean values of three individual experiments (n = 3). Error bars indicate s.d.

In heat-tolerant P. malaianus, the genes were induced above the control levels with treatment at 35 and 40 °C (Fig. 6A) but not at 30 °C (data not shown). During treatment at 35 °C, the heat-stress response of the A30 plants resembled that of the C25 plants; HSFA2 and sHSP-cp transcript levels were elevated after 1 h of heat shock and decreased to control levels by 8 h. However, the heat response differed markedly between the two cultivated conditions at 40 °C. The transcript levels of HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes were elevated after 2 h of heat exposure and then gradually reduced in C25 plants, while they were continuously induced during heat-shock treatment in A30 plants. The effects of heat acclimation on all gene transcripts, except HSP21b, were significant 8 h after heat shock.

The real-time PCR assay confirmed the loss of HSFA2a2 transcripts in the heat-sensitive P. perfoliatus. The HSFA2a1 and CP-sHSP genes were induced above control levels under treatment at 30 and 35 °C (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, heat-shock induction of CP-sHSP transcripts at 30 °C was significantly lower in A30 plants than in C25 plants. Both plants showed no differences in transcript levels of HSFA2a1 and the two CP-sHSP genes during 35 °C treatment. Their expression profiles were quite similar to those of P. malaianus (Fig. 6A: 35 °C treatment). They were markedly elevated after 1 h of heat exposure, and gradually decreased to control levels. At 40 °C treatment, expression of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes was barely detectable above control levels during the initial 2 h of heat shock, and the total RNA yield was significantly reduced after 4 h of heat shock (data not shown). In P. perfoliatus, continuous induction of HSFA2a1 and CP-sHSPs did not occur during heat stress at 35 or 40 °C, which was the lethal temperature in the chlorophyll bioassay (Fig. 1B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined thermotolerance and HSFA2 genes in two Potamogeton species, which are closely related but differ in survival on land. A chlorophyll bioassay revealed that the two species differed in thermotolerance. The heterophyllous species P. malaianus had a higher basal thermotolerance and developed acquired thermotolerance, while the homophyllous P. perfoliatus was heat-sensitive and lacked the capacity to acquire thermotolerance (Fig. 1). Moreover, these differences were associated with variation in heat induction of duplicated HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes.

HSFA2 and acquisition of thermotolerance

Because of the complexity of the plant HSF network, our understanding of the heat-stress response and acquired thermotolerance is still limited (Kotak et al., 2007). Recent Arabidopsis research suggests that HsfA1d and HsfA1e are involved in transcriptional regulation of HSFA2 through HSEs in the promoter region (Nishizawa-Yokoi et al., 2011). The At-HSFA2 protein binds to the HSE of target genes, such as HSP25·3-P (CP-sHSP), Hsp101 and ascorbate peroxidase 2, and stimulates their transcription (Nishizawa et al., 2006; Schramm et al., 2006). The HSFA2 knockout mutants markedly reduced transcription levels of target genes during recovery after prolonged heat stress, and caused a decrease in acquired thermotolerance (Baniwal et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Charng et al., 2007). Taking these data together, HSFA2 is thought to be essential for extending the duration of acquired thermotolerance (Charng et al., 2007). Moreover, the extent of basal and acquired thermotolerance is dependent on the expression level of the HSFA2 gene (Ogawa et al., 2007). Although our experimental data were not comprehensive, the species-specific heat-stress responses in Potamogeton resembled those of an Arabidopsis mutant analysis. Excluding Pp-HSFA2a2, Potamogeton HSFA2 genes with canonical HSEs were also induced by heat (Fig. 4). After heat-acclimation cultivation of A30, P. malaianus gains the ability to sustain HSFA2 and CP-sHSP expression (Fig. 6A, heat response at 40 °C) and acquires thermotolerance (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, no such phenotype was observed in P. perfoliatus, which is defective in the heat-induction of the HSFA2a2 gene (Figs 1B and B). In addition, basal thermotolerance is lowered in P. perfoliatus, as also shown in the Arabidopsis HSFA2 knockout mutant (Li et al., 2005; Ogawa et al., 2007). Although the heat-stress response is regulated through complex interactions among cellular mechanisms, our preliminary results indicate that one duplicated HSFA2a in pondweed is likely to be involved in the acquisition of thermotolerance.

Heat acclimation leads to a species-specific response in Potamogeton

Another important aspect of the heat response was represented by the lower threshold temperature required for induction of the heat shock response, or the ‘minimum temperature’ (Fig. 6). In plants and most sessile organisms, the minimum temperature is based on the evolutionary history of each organism (Tomanek and Somero, 1999; Barua and Heckathorn, 2004). During heat-acclimation cultivation, the minimum temperature for heat induction of the HSFA2 and CP-sHSP genes remained the same in P. malaianus, and C25 and A30 plants responded identically to heat shock at 35 °C (Fig. 6A). Alternatively, the minimum temperature increased above 30 °C in P. perfoliatus (Fig. 6B). Some marine animals exhibit plasticity in the minimum temperatures after acclimation to higher temperatures, allowing them to fine-tune their growth conditions (Roberts et al., 1997; Feder and Hofmann, 1999). During heat acclimation, P. perfoliatus was accustomed to daily moderate temperature fluctuations and consequently the induction of CP-sHSPs decreased during heat shock at 30 °C. Heat acclimation has mainly focused on the acquisition of thermotolerance. Our study showed that heat acclimation leads to acquired thermotolerance in heat-tolerant plants and elevates the minimum threshold temperature of the heat response in heat-sensitive plants.

Significance of heat acclimation in adaptation to aquatic temperature environments

Generally, plants optimize their respiration and photosynthetic traits to their growth environment in a process known as temperature acclimation (Berry and Björkman, 1980). During seasonal temperature elevation, the heat-tolerant P. malaianus is capable of maintaining high performance through the acquisition of thermotolerance, while the heat-sensitive P. perfoliatus performs poorly at high temperatures. In P. perfoliatus, net photosynthesis remained constant between 6 and 33 °C, and decreased rapidly above 33 °C (Pilon and Santamaria, 2001). This is consistent with our observation of a temperature threshold lower than 35 °C (Fig. 1B). The degree of heat injury varies depending on intensity, duration, frequency of exposure, rate of temperature changes and capacity for acquired thermotolerance. Terrestrial plants can cope with a high temperature for short periods of time, such as during the mid-afternoon in summer. In the two pondweeds, similar heat responses occurred at 35 °C (Fig. 6), indicating that heat-sensitive P. perfoliatus can survive transient heat elevation.

Most aquatic plants are thought to have originally thrived on land and adapted secondarily to an aquatic habitat (Cook, 1999). Daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations and temperature elevation often occur in shallow water bodies, while in deeper waters temperatures are more stable throughout the year. Heat-tolerant P. malaianus is dominant in shallow water (with temporary exposure on land) in tropical to warm-temperate zones of East Asia (Kadono, 1982). For P. malaianus having heterophyllous states, the ability to acquire thermotolerance is beneficial for survival in its natural habitats. The exclusively submerged P. perfoliatus is widespread in deeper water in temperate to sub-arctic zones of the northern hemisphere and has invaded New Zealand (Wiegleb and Kaplan, 1998; Champion and Clayton, 2000). For P. perfoliatus, the loss of acquired thermotolerance and plasticity of the minimum temperature may be more favourable in an aquatic habitat with limited daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations or relatively low temperatures throughout the year.

Conclusions

Due to its severe effect on biological processes, high temperature is a major environmental factor restricting the distribution of organisms. Although we were not able to prove a causal relationship between the expression of one duplicated HSFA2a gene and acquired thermotolerance, our comparative study on thermotolerance indicated that heat acclimation leads to species-specific physiological changes in heat response. After acquisition of thermotolerance, heat-tolerant plants are able to maintain HSFA2 and CP-sHSPs transcription at a higher level to overcome severe temperature stress. However, the accumulation of HSPs might incur significant nitrogen costs and have detrimental effects on growth (e.g. Heckathorn et al., 1996; Feder and Hofmann, 1999). Interestingly, heat-sensitive plants decrease in threshold temperature of CP-sHSP induction during heat acclimation. Such plasticity may be beneficial in moderate growth environments with only minor elevations in daily temperature. High temperatures generally induce a variety of stress responses in addition to the synthesis of HSPs. Further studies are required to explore the result that the loss of acquired thermotolerance is associated with a decrease in heat stress-related responses, such as that observed in the At-HSFA2 knockout mutant (Schramm et al., 2006). Environmental stress has played a major role in the evolution and diversification of plants. Comparative studies on thermotolerance may help to elucidate the mechanisms of physiological adaptation and ecological and geographical constraints set by temperature.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Mikio Nishimura and Kenji Yamada (National Institute for Basic Biology), and Drs Yasuro Kadono and Kunio Inoue (Kobe University) for helpful discussions. We thank the reviewers for their excellent suggestions to improve the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Amin J, Ananthan J, Voellmy R. Key features of heat shock regulatory elements. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1988;8:3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baniwal SK, Bharti K, Chan KY, et al. Heat stress response in plants: a complex game with chaperones and more than twenty heat stress transcription factors. Journal of Biosciences. 2004;29:471–487. doi: 10.1007/BF02712120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua D, Heckathorn SA. Acclimation of the temperature set-points of the heat-shock response. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2004;29:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Barua D, Heckathorn SA, Downs CA. Variation in chloroplast small heat-shock protein function is a major determinant of variation in thermotolerance of photosynthetic electron transport among ecotypes of Chenopodium album. Functional Plant Biology. 2003;30:1071–1079. doi: 10.1071/FP03106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Björkman O. Photosynthetic response and adaptation to temperature in higher plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 1980;31:491–543. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JJ. Integration of acquired thermotolerance within the developmental program of seed reserve mobilization. In: Cherry JH, editor. Biochemical and cellular mechanisms of stress tolerance in plants. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JJ. Characterization of acquired thermotolerance in soybean seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 1998;36:601–607. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JJ, O'Mahony PJ, Oliver MJ. Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants lacking components of acquired thermotolerance. Plant Physiology. 2000;123:575–587. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch W, Wunderlich M, Schöffl F. Identification of novel heat shock factor-dependent genes and biochemical pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Journal. 2005;41:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion PD, Clayton JS. Border control for potential aquatic weeds. Science for Conservation. 2000;141:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Charng YY, Liu HC, Liu NY, et al. Heat-inducible transcription factor, HsfA2, is required for extension of acquired thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:251–262. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CDK. The number and kinds of embryo-bearing plants which have become aquatic: a survey. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 1999;2:79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Downs CA, Heckathorn SA, Bryan JK, Coleman JS. The methionine-rich low-molecular-weight chloroplast heat-shock protein: evolutionary conservation and accumulation in relation to thermotolerance. American Journal of Botany. 1998;85:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response. Annual Review of Physiology. 1999;61:243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig HH, Winter K, Cushman J, Borland A, Taybi T. An improved RNA isolation method for succulent plant species rich in polyphenols and polysaccharides. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2000;18:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Harada I. Cytological studies in Helobiae, I. Chromosome ideograms and a list of chromosome numbers in seven families. Cytologia. 1955;21:306–328. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn SA, Poeller GJ, Coleman JS, Hallberg RL. Nitrogen availability alters patterns of accumulation of heat-stress induced proteins in plants. Oecologia. 1996;105:413–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00328745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Kosuge K, Kadono Y. Molecular phylogeny of Japanese Potamogeton species in light of noncoding chloroplast sequences. Aquatic Botany. 2004;80:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Yamada A, Amano M, Ishii J, Kadono Y, Kosuge K. Inherited maternal effects on the drought tolerance of a natural hybrid aquatic plant, Potamogeton anguillanus. Journal of Plant Research. 2007;120:473–481. doi: 10.1007/s10265-007-0087-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Miyagi A, Aoki S, Ito M, Kadono Y, Kosuge K. Molecular adaptation of rbcL in the heterophyllous aquatic plant Potamogeton. PLoS ONE. 2009;42:e4633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004633. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004633 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi CP, Kluveva NY, Morrow KJ, Nguyen HT. Expression of a unique plastid localized heat shock protein is genetically linked to acquired thermotolerance in wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:834–841. [Google Scholar]

- Kadono Y. Distribution and habitat of Japanese Potamogeton. The Botanical Magazine Tokyo. 1982;95:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Knight CA, Ackerly DD. Correlated evolution of chloroplast heat shock protein expression in closely related plant species. American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:411–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskull-Döring P, Scharf KD, Nover L. The diversity of plant heat stress transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science. 2007;12:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak S, Larkindale J, Lee U, Koskull-Döring P, Vierling E, Scharf KD. Complexity of the heat stress response in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2007;10:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Hübel A, Schöffl F. Derepression of the activity of genetically engineered heat shock factor causes constitutive synthesis of heat shock proteins and increased thermotolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Journal. 1995;8:603–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8040603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chen Q, Gao X, Qi B, Chen N, Xu S, Chen J, Wang X. AtHsfA2 modulates expression of stress responsive genes and enhances tolerance to heat and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Science in China Series C: Life Sciences. 2005;48:540–550. doi: 10.1360/062005-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods in Enzymology. 1987;148:350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Roberts JK, Key JL. Acquisition of thermotolerance in soybean seedlings. Plant Physiology. 1984;74:152–160. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AL, Zou J, Zhang XW, et al. Expression profiles of class A rice heat shock transcription factor genes under abiotic stresses. Journal of Plant Biology. 2010;53:142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Whittier RF. Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR: automatable amplification and sequencing of insert end fragments from P1 and YAC clones for chromosome walking. Genomics. 1995;25:674–681. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Mittler R. Could heat shock transcription factors function as hydrogen peroxide sensors in plants? Annals of Botany. 2006;98:279–288. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SK, Tripp J, Winkelhaus S, et al. In the complex family of heat stress transcription factors HsfA1 has a unique role as master regulator of thermotolerance in tomato. Genes and Development. 2002;16:1555–1565. doi: 10.1101/gad.228802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D, Chakrabarti S, Sarkar A, Singh A, Grover A. Heat shock factor gene family in rice: genomic organization and transcript expression profiling in response to high temperature, low temperature and oxidative stresses. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2009;47:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa A, Yabuta Y, Yoshida E, Maruta T, Yoshimura K, Shigeoka S. Arabidopsis heat shock transcription factor A2 as a key regulator in response to several types of environmental stress. Plant Journal. 2006;48:535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Nosaka R, Hayashi H, et al. HsfA1d and HsfA1e involved in the transcriptional regulation of HsfA2 function as key regulators for the Hsf signaling network in response to environmental stress. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2011;52:933–945. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L, Bharti K, Döring P, Mishra SK, Ganguli A, Scharf KD. Arabidopsis and the Hsf world: how many heat stress transcription factors do we need? Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2001;6:177–189. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0177:aathst>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa D, Yamaguchi K, Nishiuchi T. High-level overexpression of the Arabidopsis HsfA2 gene confers not only increased thermotolerance but also salt/osmotic stress tolerance and enhanced callus growth. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:3373–3383. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony PJ, Burke JJ, Oliver MJ. Identification of acquired thermotolerance deficiency within the ditelosomic series of ‘Chinese Spring’ wheat. Plant Physiology & Biochemistry. 2000;38:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Pilon J, Santamaria L. Seasonal acclimation in the photosynthetic and respiratory temperature responses of three submerged freshwater macrophyte species. New Phytologist. 2001;151:659–670. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646x.2001.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DA, Hofmann GE, Somero GN. Heat-shock protein expression in Mytilus californianus: acclimatization (seasonal and tidal-height comparisons) and acclimation effects. Biological Bulletin. 1997;192:309–320. doi: 10.2307/1542724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf KD, Heider H, Höhfeld I, Lyck R, Schmidt E, Nover L. The tomato Hsf system: HsfA2 needs interaction with HsfA1 for efficient nuclear import and may be localized in cytoplasmic heat stress granules. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18:2240–2251. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöffl F, Prändl R, Reindl A. Regulation of the heat-shock response. Plant Physiology. 1998;117:1135–1141. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm F, Ganguli A, Kiehlmann E, Englich G, Walch D, Koskull-Döring P. The heat stress transcription factor HsfA2 serves as a regulatory amplifier of a subset of genes in the heat stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2006;60:759–772. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-5750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio A, Dreos R, Aparicio F, Maule AJ. The cytosolic protein response as a subcomponent of the wider heat shock response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:642–654. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4·0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari AK, Tripathy BC. Acclimation of chlorophyll biosynthetic reactions to temperature stress in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Planta. 1999;208:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Tomanek L, Somero GN. Evolutionary and acclimation-induced variation in the heat-shock responses of congeneric marine snails (genus Tegula) from different thermal habitats: implications for limits of thermotolerance and biogeography. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1999;202:2925–2936. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.21.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierling E. The roles of heat shock proteins in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1991;42:579–620. [Google Scholar]

- Wang BB, Brendel V. Genomewide comparative analysis of alternative splicing in plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:7175–7180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602039103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Luthe DS. Heat sensitivity in a bentgrass variant. Failure to accumulate a chloroplast heat shock protein isoform implicated in heat tolerance. Plant Physiology. 2003;133:319–327. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Vierling E. Chloroplast small heat shock proteins: evidence for atypical evolution of an organelle-localized protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1999;96:14394–14399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells C, Pigliucci M. Adaptive phenotypic plasticity: the case of heterophylly in aquatic plants. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 2000;3:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegleb G. Notes on pondweeds: outlines for a monographical treatment of the genus Potamogeton L. Feddes Repertorium. 1988;99:249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegleb G, Kaplan Z. An account of the species of Potamogeton L. (Potamogetonaceae) Folia Geobotanica. 1998;33:241–316. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Lis JT. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science. 1988;239:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.3125608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarwood CE. Acquired tolerance of leaves to heat. Science. 1961;134:941–942. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani N, Ichikawa T, Kondou Y, et al. Expression of rice heat stress transcription factor OsHsfA2e enhances tolerance to environmental stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta. 2008;227:957–967. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.