Abstract

Despite the prevalence of HIV-associated episodic memory impairment and its adverse functional impact, there are no empirically-validated cognitive rehabilitation options for HIV-infected persons. The present study examined the self-generation approach, which is theorized to enhance new learning by elaborating and deepening encoding. Participants included 54 HIV-infected and 46 seronegative individuals, who learned paired word associates in both self-generated and didactic encoding experimental conditions. Results revealed main effects of HIV serostatus and encoding condition, but no interaction. Planned comparisons showed that both groups recalled significantly more words learned in the self-generation condition, and that HIV+ individuals recalled fewer words overall compared to their seronegative counterparts at delayed recall. Importantly, HIV+ participants with clinical memory impairment evidenced comparable benefits of self-generation compared to unimpaired HIV+ subjects. Self-generation strategies may improve verbal recall in individuals with HIV infection and may therefore be an appropriate and potentially effective cognitive rehabilitation tool in this population.

Keywords: Episodic memory, neuropsychological assessment, AIDS dementia complex, generation effect (learning), cognition, cognitive rehabilitation

Introduction

Although the incidence of HIV-associated dementia has fallen since the inception of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), milder forms of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) remain highly prevalent (e.g., Heaton et al., 2010). In fact, recent data suggest that HAND may be more prevalent in individuals with less severe HIV disease in the cART era, with specific increases noted in the rates of executive dysfunction and episodic memory impairment (Heaton et al., 2011). Among individuals with HAND, approximately 50-60% evidence mild-to-moderate deficits in learning and memory (Heaton et al., 2011). Consistent with HIV infection's preferential effects on the frontostriatal neural systems (Ellis, Langford, & Masliah, 2007), the profile of HIV-associated memory deficits is primarily characterized by impairment in strategic encoding and retrieval, with consolidation/retention processes being relatively spared (e.g., Murji et al., 2003). Highlighting their ecological relevance, HIV-associated episodic memory deficits are reliably associated with poorer daily functioning outcomes, such as unemployment (e.g., van Gorp et al., 2007) and medication nonadherence (e.g., Hinkin et al., 2002).

Despite the prevalence of HIV-associated episodic memory impairment and its adverse impact on everyday functioning, there are no conceptually-informed, empirically-validated approaches to remediating memory deficits in this vulnerable population. As such, it may be prudent to implement memory remediation techniques that have emerged from the cognitive rehabilitation literature. A number of interventions have been developed that are based on basic cognitive science, and they yield robust improvements in memory outcomes. Considering the strategic encoding deficits evident in HIV infection, the self-generation approach may be of particular interest.

Self-generated encoding is theorized to facilitate deeper and more elaborative encoding of information, ultimately resulting in enhanced recall (Slamecka & Graf, 1978), a phenomenon referred to as the generation effect. In a common self-generation experiment, participants are presented with word pairs in either a didactic format (i.e., explicitly presented) or a self-generated condition in which an entire stem word is presented didactically, but only the first letter of the second word is presented. To generate the second word, the participant is provided a semantic cue that delineates a relationship between the paired word associates.

Relative to simple didactic presentation, a vast literature now shows that self-generation has a robust effect on both recall and recognition tasks in cognitively normal adults (e.g., Slamecka & Graf, 1978). Although there has been considerable debate over the cognitive mechanisms that moderate the generation effect, candidate hypotheses include the selective rehearsal displacement theory and the transfer-appropriate processing theory (see Bertsch, Pesta, Wiscott, & McDaniel, 2007). Of clinical relevance, self-generation has been effective in ameliorating verbal recall deficits in a variety of neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (e.g., Chiaravalloti & DeLuca, 2002; Basso, Lowery, Ghormley, Combs, & Johnson, 2006), traumatic brain injury (e.g., O'Brien, Chiaravalloti, Arango-Lasprilla, Lengenfelder, & DeLuca, 2007), and mild dementia (e.g., Lipinska, Bäckman, Mäntylä, & Viltanen, 1994). However, the generation effect is not necessarily effective in all clinical populations, including frontotemporal dementia (e.g., Souliez, Pasquier, Lebert, Leconte, & Petit, 1996) and advanced Alzheimer's disease (e.g., Dick, Kean, & Sands, 1989). As such, the present study aimed to explore the effectiveness and cognitive correlates of a self-generation paradigm in HIV infection, with the hypothesis that persons living with HIV will perform better using self-generated encoding compared to a didactic presentation of verbal material to be recalled.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the institution's human research protections program. Participants included 54 HIV-infected and 46 HIV-seronegative individuals with broadly similar risk factors (e.g., substance abuse) recruited from the San Diego community and local HIV clinics. All participants were enrolled in a project that examined the combined effects of HIV and aging on memory; as such, the inclusion criteria across both serostatus groups was age ≥ 50 (“Older”) or ≤ 40 (“Younger”) years (NB. the HIV+ and HIV- groups were nevertheless comparable in age) and completion of the self-generation paradigm. Exclusion criteria were presence of severe psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia), neurological disease (e.g., seizure disorders, stroke, closed head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 15 minutes, and central nervous system neoplasms or opportunistic infections), verbal IQ scores <70 (based on Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR]; Psychological Corporation, 2001), a diagnosis of substance dependence within 1 month of assessment, and a urine toxicology screen positive for illicit drugs (excluding marijuana) or positive breathalyzer test on the day of testing. Table 1 describes the demographic, psychiatric, and medical characteristics of both groups.

Table 1.

Demographic, psychiatric and disease characteristics of the study sample

| HIV – (n=46) | HIV + (n=54) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age (years)a | 47.9 (13.4) | 47.8 (13.4) | 0.803 |

| Education (years)a | 14.1 (2.1) | 13.8 (2.2) | 0.376 |

| Sex (% male) | 58.7% | 77.8% | 0.040 |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 60.9% | 61.1% | 0.980 |

| Psychiatric Characteristics | |||

| Lifetime Major Depressive Disorder (%) | 54.4% | 59.3% | .621 |

| Lifetime Generalized Anxiety Disorder (%) | 4.4% | 25.9% | .003 |

| Lifetime Substance Use Disorder (%) | 67.4% | 64.8% | .786 |

| HIV Disease Characteristics | |||

| Proportion with AIDS (%) | - | 62.3% | - |

| Proportion on HAART (%) | - | 88.7% | - |

| Detectable Plasma Viral Load (%) | - | 17.0% | - |

| Nadir CD4 Countb | - | 164.0 (71.5, 300.0) | - |

| Current CD4 Countb | - | 546.0 (368.3, 801.0) | - |

Note.

Means (SD).

Median (interquartile range).

HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus. AIDS = Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. HAART = Highly active antiretroviral therapy. CD4 = Cluster of differentiation.

Materials and Procedure

After providing written informed consent, participants completed a comprehensive neuropsychological, psychiatric, and medical evaluation for which they received nominal monetary compensation.

Self-generation task

To examine self-generated learning, participants were presented 100 word pair associates (Slamecka & Graf, 1978) through either self-generated or didactic encoding (for further detail, please see Basso, Lowery, Ghormley, Combs, & Johnson, 2006). In brief, the didactic condition was administered such that participants were shown 50 word pairs that they were instructed to read aloud (e.g., autumn-fall). In the self-generation condition, participants received 50 word pairs in which they were presented the first word, but were asked to produce the second word based on its first letter (e.g., autumn-f___) and its lexicosemantic relationship with the stem word (i.e., associate, category, synonym, rhyme, and opposite). Participants were instructed to pay specific attention to the second word of each pair because they would be later asked to recall it. The primary dependent variables of interest were the immediate and 20-minute delayed free recall scores from the self-generation and didactic conditions, as well as recognition scores from both conditions. We tabulated the number of errors made by participants during the act of self-generation (i.e., individual is unable to generate the second word correctly [range of total errors in this sample = 0-21]).

General neuropsychological assessment

Participants completed a neuropsychological battery that adhered to the Frascati research criteria for assessing HAND (Antinori et al., 2007). These tests included: WAIS-III Digit Symbol (total symbols completed), Trail Making Tests A & B (total time to complete), D-KEFS Noun Switching Fluency trial (total words generated), Tower of London-Drexel version (total move score), California Verbal Learning Test 2nd Edition (trial 1 total, trials 1-5 total, long delay total words recalled, total semantic clustering), WMS-III Logical Memory (total immediate recall, total delayed recall), WAIS-III Digit Span (total trials completed), and Grooved Pegboard (completion times) (see Woods et al., 2007). Neurocognitive test scores were converted to clinical ratings in the following domains; information processing speed, verbal fluency, executive functions, learning, memory, motor skills, and attention/working memory (Woods et al., 2004). For the determination of episodic memory impairment in our posthoc analyses, individuals who evidenced a clinical deficit (i.e., T-score < 40) on any primary scores from tests of learning (i.e., Logical Memory immediate recall, and CVLT-II total trials 1-5, total semantic clustering) or delayed memory (i.e., Logical Memory delayed recall or CVLT-II delayed free recall or recognition discriminability) were classified as impaired (see Heaton, Miller, Taylor, & Grant, 2004).

Results

Self-Generation Primary Analyses

The present study examined the effect of self-generated learning in HIV infection using three mixed model ANOVAs to analyze performance on the immediate recall (IR), delayed recall (DR), and recognition trials. The between-subjects factor was HIV serostatus, and across statistical models, the within-subjects factor was the number of words either recalled or recognized under the self-generation or didactic conditions. Given the design of the parent study and the HIV serostatus effects reported in Table 1, age group and sex were included in the models as covariates.

Immediate recall MANOVA

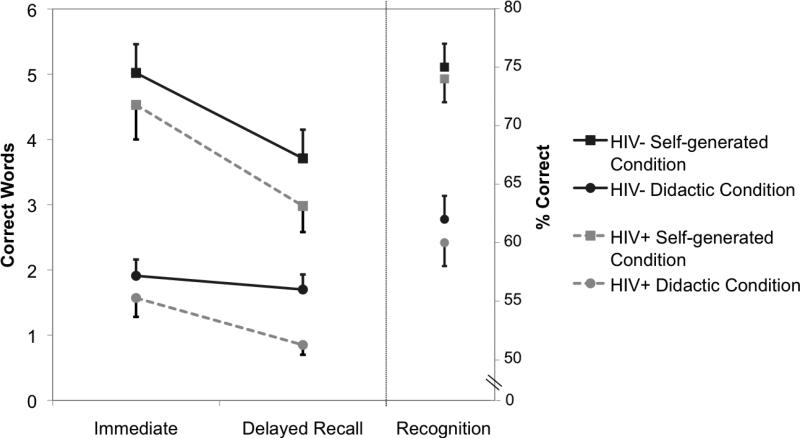

This analysis yielded a main effect of encoding condition (F[1, 96] = 56.64, p<0.001, η2=0.355), whereby individuals recalled more words from the self-generated condition compared to the didactic condition, (t(99) = -8.77, p<0.001, d=1.10). Neither the main effect of serostatus nor the interaction between serostatus and encoding condition were significant (ps>0.10 η2<0.01). (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Line graphs displaying the immediate recall, delayed recall, and recognition tasks across both encoding conditions in the HIV+ (n = 54) and HIV- (n = 46) subjects.

Delayed recall MANOVA

Similarly, this analysis revealed a main effect of encoding condition (F[1, 96]=37.11, p<0.001, η2=0.250), whereby individuals recalled more words from the self-generated condition compared to the didactic condition, (t(99)=-6.92, p<0.001, d=0.89). Additionally, there was a main effect of serostatus (F[1, 96]=4.55, p=0.036, η2=0.069), whereby HIV+ individuals recalled fewer overall words than their seronegative counterparts (t(88.3)=- 2.25, p=0.027, d=0.45). The interaction term was not significant (p>0.10, η2<0.01).

Recognition MANOVA

This analysis also revealed a main effect of encoding condition (F[1, 95]=111.18, p<0.001, η2=0.549), whereby individuals recognized more words from the self-generated condition compared to the didactic condition (t(98)=-11.10, p<0.001, d=0.99). Neither the serostatus nor interaction effects were significant (ps>0.10, η2<0.01).

Effects of HIV-associated memory impairment

Consistent with previous literature on the generation effect (e.g., Basso et al., 2006), we repeated the three MANOVAs described above only within the HIV+ sample, with the dichotomized clinical memory impairment status as the sole between-subjects factor (impaired n=26; normal n=28). (NB. These two groups did not differ on any demographic, disease, or psychiatric variables.) All three analyses revealed main effects of generation condition (all ps<0.001; all η2s>0.139) and no significant main effect of impairment status (all ps>0.10; all η2s<0.01) or interaction between impairment and generation condition (all ps>0.10; all η2s<0.05). Post-hoc paired-samples t-tests demonstrated significant benefits of self-generation in both the HIV+ unimpaired and impaired samples on the immediate recall (unimpaired: d=1.26, p<0.001; impaired: d=0.69, p<0.001), delayed recall (unimpaired: d=1.05, p<0.001; impaired: d=0.84, p<0.001), and recognition (unimpaired: d=1.26, p<0.001; impaired: d=0.60, p<0.001) trials.

Cognitive Mechanisms of Delayed Recall Generation Effect

Finally, we sought to examine the cognitive correlates of the generation effect, which was operationalized as a simple difference score between self-generated and didactic words on delayed recall task in the HIV+ sample. Findings revealed a significant association with verbal fluency rating (Spearman's ρ=0.28; p=0.037), but no other clinical domain rating was significantly correlated with the generation effect difference score (ps>0.05), with the exception of a trend-level finding for the memory domain (Spearman's ρ=0.25; p=0.073).

Discussion

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders remain common despite medical advances to manage the immunovirological aspects of the disease, but there has been little effort to develop effective cognitive neurorehabilitation approaches in this population. Although HIV impacts a wide range of cognitive functions, one might argue that it is particularly important to specifically target deficits in episodic memory, given their prevalence and relevance to everyday functioning. In this vein, the present study sought to examine the validity of the generation effect in an HIV-infected population to determine its potential efficacy as a memory rehabilitation strategy. Our primary results showed a robust main effect of self-generation on immediate and delayed recall as well as recognition of generated words from associated pairs. In other words, participants were better able to recall or recognize words they had produced as part of a word pair compared to words that they were simply asked to read aloud. In fact, as demonstrated in Figure 1, HIV-infected individuals’ performance in the self-generated condition surpassed the performance of their seronegative counterparts on the control didactic condition, suggesting that this strategy ostensibly normalized the HIV-associated memory deficit on this task. This is particularly important given the main effect of HIV status on the delayed recall component of the task, whereby HIV-infected individuals recalled significantly fewer words in total compared to the HIV-seronegative sample. Of note, we did not observe an interaction between encoding condition and clinical memory impairment status among the HIV-infected sample, which suggests that the generation effect is present in the individuals for whom such an intervention is arguably most indicated. These results are consistent with findings in other similar neurological conditions that experience mild-moderate memory deficits, such as multiple sclerosis (e.g., Basso et al., 2006).

A relatively unique contribution of the present study to the self-generation literature is the examination of cognitive correlates of the generation effect described as a difference score, thereby examining the relationship between cognitive domains and the degree to which a given participant benefitted from self-generation. Although memory was modestly correlated (but not statistically significant) with self-generation gains at delayed recall, semantic verbal fluency (noun switching) emerged as the sole significant predictor. Speaking to the specificity of this verbal fluency finding, generation gains at delayed recall were not associated with broader executive dysfunction (e.g., planning, set shifting). Thus, while prior studies have largely focused on the contribution of episodic memory impairment to the better recall performance on self-generated trials (e.g., O'Brien et al., 2007), the executive aspects of semantic verbal fluency may also be important, particularly in terms of within-subject gains. Although one might argue this association could be driven by degradation of semantic memory stores themselves, a subsequent post-hoc analysis showed that the generation difference score was not correlated with a test of semantic memory (i.e., Pyramids and Palm Trees; Spearman's ρ = 0.13; p>0.10). In sum, these data suggest that the self-initiated search and retrieval aspects of generative fluency are more relevant to realizing benefits from self-generation episodic memory paradigms than the integrity of the semantic memory stores themselves.

This study is not without its limitations. First, the results may not generalize to other HIV-infected populations given this cohort's relative immune health and limited demographic diversity. Given the restrictions of the parent grant's inclusion criteria, this concern is particularly salient due to the lack of individuals between the ages 41 and 49, who may be more representative of the epidemic. Second, this study only examined the generation effect using a verbal memory task and therefore further investigation of the generation effect in HIV in other modalities (e.g., sentence completion) is needed. Within this specific task, intrusion errors committed on self-generation trials were not recognized as correct in recall total scores, which is consistent with prior studies, but may have lowered recall scores and therefore underestimated the potential benefits of the paradigm. In addition, the use of a difference score between the didactic and self-generation trials to examine cognitive correlates of the generation effect may be less psychometrically desirable in some was (e.g., less reliable) as compared to a more traditional analysis of the self-generation trial total score. Finally, future studies should seek to broaden the exploration of the generation effect in this population, both in terms of other aspects of memory (e.g., prospective memory) as well as determining its ecological relevance. With respect to the latter, Basso and colleagues (2006) examined the generation effect on a lab-based task of everyday functioning (i.e., generating appointment times for errands) in an MS population, in which they found that allowing participants to generate the target assisted in their ability to remember the details of their appointments at recall and recognition. Beyond the laboratory, the use of self-generation has potential for being a much-needed efficacious cognitive rehabilitation intervention for HIV-associated episodic memory deficits in the clinic, for which there are currently no empirically validated treatments. For example, these data argue for increased patient involvement in generating verbal mnemonic strategies to assist in everyday memory tasks as well as to enhance didactic interventions that target adherence and HIV transmission risk behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program [HNRP] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Scott Letendre, M.D., Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Terry Alexander, R.N., Debra Rosario, M.P.H., Shannon LeBlanc; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., John Hesselink, M.D., Jacopo Annese, Ph.D., Michael J. Taylor, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D., Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D. (Consultant); Neurovirology Component: Douglas Richman, M.D., (P.I.), David M. Smith, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.), Rodney von Jaeger, M.P.H.; Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S., Tanya Wolfson, M.A.

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-MH73419 and T32-DA31098 to Dr. Woods and P30-MH62512 to Dr. Grant. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government. The authors thank Marizela Cameron, Nichole Duarte, Patricia Riggs, and Katie Doyle for their help with study management.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MR, Lowery N, Ghormley C, Combs D, Johnson J. Self-generated learning in people with multiple sclerosis. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12:640–648. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch S, Pesta BJ, Wiscott R, McDaniel MA. The generation effect: A meta-analytic review. Memory & Cognition. 2007;35:201–210. doi: 10.3758/bf03193441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Self-generation as a means of maximizing learning in multiple sclerosis: An application of the generation effect. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;83:1070–1079. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick MB, Kean ML, Sands D. Memory for internally generated words in Alzheimer-type dementia: Breakdown in encoding and semantic memory. Brain and Cognition. 1989;9:88–108. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(89)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: Neuronal injury and repair. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2007;8:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, The CHARTER Group HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, The HNRC Group HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: Differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of Neurovirology. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59:1944–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038347.48137.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinska B, Bäckman L, Mäntyä T, Viltanen M. Effectiveness of self-generated cues in early Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology. 1994;16:809–819. doi: 10.1080/01688639408402695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murji S, Rourke SB, Donders J, Carter SL, Shore D, Rourke BP. Theoretically derived CVLT subtypes in HIV-1 infection: Internal and external validation. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:1–16. doi: 10.1017/s1355617703910010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A, Chiaravalloti N, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Lengenfelder J, DeLuca J. An investigation of the differential effect of self-generation to improve learning and memory in multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2007;17:273–292. doi: 10.1080/09602010600751160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation . Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. Author; San Antonio, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Slamecka NJ, Graf P. The generation effect: Delineation of a phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning & Memory. 1978;4:592–604. [Google Scholar]

- Souliez L, Pasquier F, Lebert F, Leconte P, Petit H. Generation effect in short term verbal and visuospatial memory: Comparisons between dementia of the Alzheimer type and dementia of the frontal lobe type. Cortex. 1996;32:347–356. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(96)80056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gorp WG, Rabkin JG, Ferrando SJ, Mintz J, Ryan E, Borkowski T, McElhiney M. Neuropsychiatric predictors of return to work in HIV/AIDS. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:80–89. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Moran LM, Carey CL, Dawson MS, Iudicello JE, Gibson S, The HNRC Group Prospective memory in HIV infection: Is “remembering to remember” a unique predictor of self-reported medication management? Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2007;23:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Frol AB, Levy JK, Ryan E, Soukup VM, Heaton RK. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26:759–778. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]