Abstract

Ambient air pollution, including particulate matter, and gaseous pollutants, are important environmental exposures that adversely affect human health. Because of their heritable and reversible nature, epigenetic modifications provide a plausible link between environment and alterations in gene expression that might lead to disease. Epidemiologic evidence supports that environmental exposures in childhood impact susceptibility to disease later in life, supporting that epigenetic changes can impact ongoing development and promote disease long after the environmental exposure has ceased. Indeed, allergic disorders often have their roots in early childhood and early exposure to particulate matter has been strongly associated with the subsequent development of asthma. The purpose of this review is to summarize recent findings on the genetic and epigenetic regulation of responses to ambient air pollutants, specifically respirable particulate matter, and their association with the development of allergic disorders. Understanding these epigenetic biomarkers and how they integrate with genetic influences to translate the biologic impact of particulate exposure is critical to developing novel preventative and therapeutic strategies for allergic disorders.

Keywords: air pollution, particulate matter, genetics, epigenetics, allergy, asthma

Introduction

Environmental air pollution is a serious public health concern throughout the world. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong link between exposure to ambient air pollution and human morbidity and mortality1-3. Major air pollutants include particulate matter, ozone and nitrogen dioxide. The regulation of cellular responses in response to pollutant gases including ozone and sulphur dioxide have been previously reviewed4-6. In this review, we will focus on particulate matter (PM). Chronic exposure to particulate matter is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, neurological disease and asthma7-10. Increased asthma incidence and hospitalization rates for asthma, and higher rates of allergic sensitization have been observed in children exposed to high levels of PM11. Pollutant-induced inflammation and oxidative stress have been implicated as contributors to these negative health effects12, but the mechanisms remain unclear.

Ambient PM is a complex mixture of chemicals and particles, of which the largest single source is traffic related and derived from diesel exhaust. Diesel exhaust particles (DEP) consist of an elemental carbon core with a large surface area to which hundreds of chemicals and transition metals are attached. Particulate matter is classified as coarse (PM10: particles of 10μm or less in aerodynamic diameter), fine (PM2.5: 2.5-0.1μm) or ultrafine (PM0.1: <0.1μm). The majority of DEP are fine or ultrafine particles. Studies have revealed profound adjuvant effects of these particles on the development and intensity of allergic inflammation, which is regulated via genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. In this review, we will summarize recent genetic studies identifying candidate genes conferring susceptibility to allergic diseases in response to particulate matter especially DEP. Furthermore, we will review epigenetic changes induced by DEP exposure, the epigenetic regulation of biological pathways mediating responses to DEP, and their association with clinical outcomes. Finally, we will discuss and propose potential approaches for future genetic and epigenetic studies related to PM exposure.

Effect of DEP exposure on inflammation

Several lines of evidence have shown that PM can act both on the upper and lower airways to initiate and exacerbate cellular inflammation. There are increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and increased numbers of neutrophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of healthy individuals exposed to DEP, and in nasal washes from subjects following nasal provocation challenge with DEP13-15. Acute DEP exposure induced NF-κB-related inflammatory and cytokine gene expression including TNFa, IL8 and IL616.

DEP can also exacerbate in vivo allergic responses. When house dust mite (HDM) was co-administered with DEP into dust mite sensitive human subjects, nasal histamine levels increased three-fold compared to HDM alone and only 20% of the amount of intranasal dust mite normally required resulted in a symptomatic response17. Furthermore, DEP dramatically increased the production of allergen-specific IgE18. In mice, DEP delivered intranasally or intratracheally with allergen results in increased airway inflammation, goblet cell hyperplasia and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR)19, 20. In summary, DEPs can promote sensitization and aggravate airway responses.

DEP can target multiple cell types including human B cells21, eosinophils22, pulmonary alveolar macrophages23, 24, airway epithelial cells and endothelial cells25. DEP can act directly on cells or indirectly by alternatively activating macrophages or dendritic cells (DC). Indeed, mice instilled with DEP increased the number of activated DC in the bronchoalveolar lavage and in the lung26; and DEP-exposed DCs induced Th2 polarization27, 28.

The mechanism by which DEP exposure modulates innate and adaptive immune responses remains unclear. Many of the effects of DEPs are attributed to chemicals in the DEP, including metals, organic compounds and biological fractions29. A hierarchical oxidative stress model has been postulated such that low dose DEP exposure leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which activate an antioxidant response and upregulate detoxifying enzymes12. A higher dose exposure would overwhelm the cell’s cytoprotective system and activate NF-κB/AP-1 mediated signaling, which results in increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-6) and adhesion molecules30. This enhanced inflammation would lead to additional generation of ROS. In support of this model, in vitro studies demonstrated that macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and epithelial cells generated ROS after stimulation by DEP or its chemical constituents11. Furthermore, the proinflammatory and adjuvant effects of DEP in animal and cell culture models were neutralized in part by thiol antioxidants31, 32. Thus, it has been proposed that oxidative stress-induced inflammation is one of the contributors to PM-induced respiratory diseases33. The chemical composition of DEP also affects the immune responses that are induced. Samples with different organic content induce distinct inflammatory allergic phenotypes34, 35, possibly through activating distinct transcriptional regulatory pathways (e.g., AP-1 or NF-κB). Another factor that modifies the biological effects of DEP is particle size. Smaller particles (PM0.1) are more likely to penetrate deeper into the respiratory tract and translocate to extrapulmonary organs through blood stream36.

Genetic influences on the response to PM exposure

There is large variation between individuals in their response to PM exposure and genetic association studies have compared the adverse effect of PM between subjects with specific genotypes in biologically relevant candidate genes. Genes encoding enzymes involved in oxidative stress including GSTM1, GSTP1 and NQO1 were identified as genes conferring genetic susceptibility to ozone exposure with the outcome of asthma4. Polymorphisms in these genes were also identified as risk factors for allergic diseases in response to DEP. In the Cincinnati Childhood Allergy and Air Pollution study (CCAAPS) birth cohort of 570 children, DEP exposure was estimated using a land-use regression mode and it was discovered that high DEP exposure during infancy conferred increased risk for wheezing among GSTP1 Val105 (rs947894) carriers37, 38. In another study, individuals who were sensitive to ragweed and carried the GSTM1 null or the GSTP1 I105 genotype showed the greatest nasal allergic responses after challenge with ragweed and DEP39. These individuals also had greatest response to ragweed after second hand smoke exposure40. When using proximity to high traffic roads as a surrogate measure of exposure, a significant interaction was observed between EPHX1, the microsomal epoxide hydrolase involved in xenobiotic metabolism, GSTP1 genotype, and distance to road. Children carrying EPHX1 genotypes with high predicted enzymatic activity, who also carried the GSTP1 Val/Val genotype and had high traffic exposure were at the highest risk of asthma41.

Genes in inflammatory pathways have also been implicated as genes relevant to the host response to PM. In the Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy (PIAMA) birth cohort, individuals with increased levels of PM2.5 in conjunction with at least one copy of the TLR2 rs4696480 A allele or any of the TLR4 genotypes (rs2770150 TC, rs10759931 GG, rs6478317 GG, rs10759932 CT or CC, and rs1927911 TT) had increased risk of doctor-diagnosed asthma from birth up to 8 years of age42. School children homozygous for TGF-β1 rs1800469T (associated with increased gene expression) had a significantly increased risk of asthma and this association was modified by residential proximity to freeway43.

One major limitation of candidate gene approach is that it relies on previous known functions of genes and pathways44. Also, these studies often have small sample sizes and examine a limited number of variants. In contrast, the genome-wide association method (GWA) is unbiased and examines SNPs across the genome. However, most common variants identified by GWAS confer small incremental risk individually or in combination and explain only a small portion of heritability. Factors contributing to this “missing” heritability have been suggested and include variants with small effects yet to be found, rare variants that are poorly detected with current assays, structural variants such as copy number variants that are not well studied, low power to detect gene-gene interaction, and environment factors that remain undefined 44. Many currently available genome-wide arrays have limited coverage, and pre-designed SNP chips might not contain SNPs in coding or regulatory regions or rare SNPs with significant effects. Thus, combining GWAS and candidate gene approaches may generate more comprehensive and consistent results45.

EPIGENETIC INFLUENCES ON THE RESPONSE TO PM EXPOSURE

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression

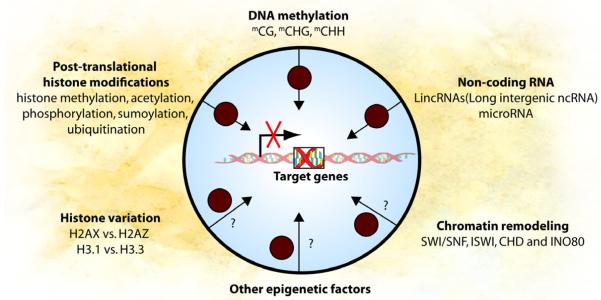

Epigenetics refers to information heritable through cell division other than the DNA sequence itself. During development, cell identities are maintained through epigenetic mechanisms. The developmental state of a cell can be reprogrammed by either somatic cell nuclear transfer or by specific genes in combination, suggesting that the information specifying cell identity is not only heritable, but ultimately reprogrammable46,47. Epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, post-translational histone modification, histone variation, chromatin remodeling and non-coding RNA (Figure 1). DNA methylation refers to the covalent addition of a methyl group to a cytosine (C) residue, and promoter methylation is correlated with gene expression silencing. It occurs mostly in the context of CG dinucleotide, however non-CG methylation has been recently described at CHG and CHH sites (where H is A, C or T)48, 49. In mammalian cells, DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) methylates hemi-methylated parent-daughter duplexes during DNA replication. Methyltransferases DNMT3a and DNMT3b de novo methylate DNA, setting up the methyl-CG landscape of the genome early in development. The mechanism for demethylating DNA remains controversial50. Recently, Ten-Eleven-Translocation (TET) proteins and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) were proposed as a plausible mechanism as the generation of 5hmC by TET proteins is associated with large scale erasure of methylation in primordial germ cells and early embryo51, 52. Hypermethylation of CpG sites located at gene promoters are commonly associated with transcriptional silencing, possibly through precluding the binding of transcription factors to their target sequences and increasing affinity to methylated DNA binding proteins that further recruit other epigenetic modifiers and corepressors53. However, it has been recently demonstrated that during cellular differentiation, reprogramming and cancer development, DNA methylation alterations happen not only at promoters, but also at other regions that are far away from transcription start sites54-56. The biological significance of these DNA methylation changes remains unclear.

Figure 1. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate gene function and are affected by PM exposure.

DNA methylation, post-translational histone modification, histone variation, chromatin remodeling complexes, non-coding RNA and other unidentified epigenetic factors interact with each other to delicately regulate gene function. PM exposure can potentially affect all these epigenetic modifications and result in altered gene expression. PM exposure induces changes in DNA methylation, histone acetylation and microRNA expression that correlate with gene expression differences. Black circles represent PM.

Modification of histones and other epigenetic mechanisms can regulate gene expression conjointly with DNA methylation (Figure 1). The carboxyl ends of histones have specific amino acids that are sensitive to posttranslational modifications including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation and ubiquitination. Open chromatin or euchromatin is characterized by high levels of acetylation and trimethylation of Histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3), lysine 36 (H3K36me3) and lysine 79 (H3K79me3). On the other hand, compact chromatin or heterochromatin is characterized by low levels of acetylation and high levels of Histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3), lysine 27(H3K27me3) and Histone 4 lysine 20 methylation (H4K20me3)57. Different histone variants are found at specific genomic locations and implicated in gene expression regulation and epigenetic memory of cellular states58, 59. Several groups of large chromatin remodeling complexes (i.e. SWI/SNF, ISWI, CHD and INO80) are known to move, destabilize, eject or restructure nucleosomes and modulate gene expression60.

Heterochromatin formation can also be mediated through interactions between long intergenic non-coding RNA (LincRNAs) and chromatin remodeling complexes, resulting in gene expression silencing. Small noncoding RNAs (miRNAs) directly target mRNAs and regulate cognate target gene expression61, 62. All epigenetic mechanisms closely intertwine with each other and regulate the gene expression program of a cell to ensure its proper cellular function.

Epigenetics and environment

The epigenome is an important target of environment-induced modification and may serve as an interface between inherited genome and dynamic environment. Heavy metals, dietary choices and maternal behavior alter DNA methylation and chromatin, and some of these epigenetic changes can be transmitted to subsequent generations6. For example, transmission of asthma risk after maternal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) may continue across two generations63.

Epidemiological studies have linked early environmental exposures, such as in utero starvation and exposure to mold, to long-term health consequences64-66, supporting the theory of the early origin of adult diseases. Epigenetic alterations can occur prenatally, perinatally, and later in life during developmental stages with unique susceptibility to the effects of environmental exposures. Children with in utero exposure to maternal smoking exposure had different repeat element and gene specific methylation compared to unexposed children67, 68. A post-weaning diet lacking in methyl-donors (folic acid, Vitamin B12, methionine and choline) can affect the CpG methylation status of specific genes, and the resulting methylation changes persisted following a return to normal diet, consistent with the stable and heritable nature of DNA methylation69.

The impact of environment on the genome may be best illustrated by twin studies. Remarkably, human monozygotic twins are indistinguishable in their overall content and genomic distribution of global 5mC and histone acetylation during the early years of life (3 years old), whereas older monozygous twins (~50 years old) exhibited remarkable differences, which correlated with differences in gene expression70, highlighting the impact environment has on epigenome.

Epigenetic changes associated with PM exposure

Multiple studies have revealed the effects of PM on the epigenome including human, in vitro, and animal studies (Table 1 and Figure 1). In the umbilical blood DNA of subjects from Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health study, the promoter of ACSL3 gene was hypermethylated and this correlated with increased maternal polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) exposure71. Furthermore, the increased DNA methylation correlated with silencing of ACSL3, which encodes an isozyme of the long-chain fatty-acid-coenzyme A ligase family and plays a key role in lipid biosynthesis and fat acid degradation. Exposing human airway epithelial cell lines to PM10 or DEP induced a global increase in histone H4 acetylation72, 73. Increased histone H4 acetylation at the promoters of IL8 and COX2 was associated with increased expression of these two genes. PM10-enhanced H4 acetylation was mediated in part by oxidative stress as thiol antioxidant inhibition by N-acetyl-L-cysteine ameliorated the effects of PM treatment72. DEP exposure also caused alteration of miRNA expression in human airway epithelial cells grown at air-liquid interface74; 197 of the 313 detectable miRNAs (62.9%) were either up-or down-regulated ≥ 1.5 fold, including many miRNAs associated with responses in inflammatory pathways. Mir-222 and mir-21, which have been implicated in redox signaling and inflammation, were upregulated after exposure to PM10. 75

TABLE 1.

Epigenetic modifications induced by PM exposure.

| Study | Environmental Pollutants |

Epigenetic Modification |

Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Studies | ||||

| Blood samples from participants in the Normative |

PM2.5, black carbon and sulfates |

DNA methylation | Hypomethylation of LINE1 was associated with exposure to traffic particles PM2.5 and black carbon. |

(Baccarelli, Wright et al. 2009) |

| Aging Study DNA from workers in an electric furnace steel plant |

PM10 | DNA methylation | Methylation of LINE1 and Alu negatively associated with level of PM10 exposure. iNOS promoter was hypomethylated after PM10 exposure. |

(Tarantini, Bonzini et al. 2009) |

| Blood samples from participants in the Normative Aging Study |

PM2.5, black carbon and sulfates |

DNA methylation | Hypomethylation of LINE1 and Alu were associated with prolonged exposure to black carbon and sulfate. The association between black carbon and Alu hypomethylation was strengthened by GSTM1 null variant. |

(Madrigano, Baccarelli et al. 2011) |

| DNA from male nonsmoking coke-oven workers and controls |

PAH | DNA methylation | Hypermethylation of LINE1 and Alu and hypomethylation of p53 and H1C1 were observed in non-smoking coke-oven workers. |

(Pavanello, Bollati et al. 2009) |

| Umbilical cord white blood cells and placental from subjects in the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health study |

Maternal PAH exposure from traffic pollution |

DNA methylation | Hypermethyltion of the ACSL3 promoter in umbilical cord blood DNA of offspring was associated with increased maternal PAH exposure. |

(Perera, Tang et al. 2009) |

| DNA from electric furnace steel plant workers |

PM and PM metal components |

microRNA expression |

Mir-222 and mir-21 were upregulated in post- exposure samples. Mir-222 expression positively correlated with lead exposure and mir-21 expression positively correlated with a marker of oxidative stress. |

(Bollati, Marinelli et al. 2010) |

|

| ||||

| In Vitro Studies | ||||

| A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line) |

PM10 | Histone modification |

PM10 treatment induced H4 acetylation at the IL8 promoter and this was associated with increased IL8 expression. |

(Gilmour, Rahman et al. 2003) |

| BEAS-2B (Human bronchial epithelial cell line) |

DEP | Histone modification |

DEP exposure increased H4 acetylation at the COX-2 promoter resulting in increased COX-2 expression. |

(Cao, Bromberg et al. 2007) |

| Human primary bronchial epithelial cells |

DEP | miRNA expression | Exposure to DEP led to altered miRNA expression. |

(Jardim, Fry et al. 2009) |

|

| ||||

| Animal Studies | ||||

| BALB/c mice | DEP | DNA methylation | Chronically inhaled exposure to DEP in Aspergillus fumigatus sensitized mice resulted in hypermethylation of the IFNG promoter and demethylation of the IL4 promoter in CD4+ cells. |

(Liu, Ballaney et al. 2008) |

| Male C57BL/CBA mice |

Ambient air near two steel mills and a major highway |

DNA methylation | Sperm DNA was hypermethylated in exposed mice and the changes persisted following removal from the environmental exposure. |

(Yauk, Polyzos et al. 2008) |

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells regulate effector T cells and have been shown to limit allergic inflammation in response to inhaled allergen76, 77. Foxp3 is the major transcription factor that mediates Treg development and its expression is epigenetically regulated78, 79. In a recent study of children with asthma exposed to high vs. low levels of ambient air pollution, hypermethylation of the FOXP3 locus was observed in the peripheral blood Tregs of asthmatic children exposed to high levels of ambient air pollution compared to the low exposure group. Furthermore, FOXP3 hypermethylation was associated with decreased Treg function and increased asthma morbidity80.

Human population studies have shown that methylation of repeat elements LINE1 and Alu are negatively associated with PM exposure81, 82(Table 1). However, in another study of 718 elderly participants in the Boston area Normative Aging Study, the methylation level of LINE1 but not Alu, decreased after recent exposure to black carbon and PM2.583 ; and an increase of LINE1 and Alu methylation in association with higher exposure to PAH was observed in the peripheral blood lymphocyte DNA from non-smoking coke-oven workers compared to matched control individuals84. Thus, although methylation changes are taking place, the specific changes in methylation may be dependent on factors such as timing and length of exposure, co-exposures, the route(s) of exposure, the target tissue/cell, and host development and genetics. These contributory factors and the mechanisms need to be better clarified.

Animal studies have been useful to evaluate epigenetic modifications following pollutant exposure. Male C57BL/CBA mice breathing ambient air near two steel mills and a major highway for 10 weeks or 16 weeks demonstrated global hypermethylation in sperm DNA compared to those breathing filtered air, and this epigenetic change persisted following removal from the environmental exposure85. In BALB/c mice sensitized by Aspergillus fumigatus, chronic inhaled exposure to DEP promoted Th2 differentiation through hypermethylation of the IFNγ promoter and hypomethylation of IL4 promoter in CD4+ T cells86. Furthermore, altered methylation of promoters of both genes was significantly correlated with changes in IgE levels.

In summary, exposure to DEP or DEP chemicals results in epigenetic changes at repeat elements and specific candidate genes, some of which are strongly correlated with alteration in expression levels. The significance of these epigenetic changes as biomarkers for DEP exposure and the underlying mechanisms require further investigations. Given that the epigenetic changes caused by DEP are inheritable during cell division and can potentially transfer to future generations, it is very important to study the role of epigenetics in the association of early life DEP exposure to allergic disorders later in life.

PROSPECTIVE AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In this review, we discussed the genetic and epigenetic influences on the cellular response to PM, DEP in particular. Although progress has been made, many questions remain (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary and remaining questions.

| What we know | Remaining questions/gaps |

|---|---|

| Biologic effects of DEP | |

| 1. DEP exposure causes inflammatory responses including altered IgE production, airway eosinophilia and airway hypersensitivity. |

1. What are the mechanisms by which the airway mucosal surface mediates the response to DEP to promote the development of allergic disease at different development periods, especially during early life? |

| 2. DEP exposure exacerbates allergic responses induced by allergen. |

2. How does DEP promote allergic sensitization and inflammation? |

|

| |

| Genetic studies | |

| 1. Genetic variants in genes including GSTM1, GSTP1, NQO1, TNF, EPHX1, TLR2 and TLR4 confer genetic susceptibility to PM exposure with the outcome of allergic responses. |

1. How do epigenetics and exposure integrate with genetics? How does this relationship change during different development stages? |

|

| |

| Epigenetic studies | |

| 1. DEP exposure induces changes in global histone modification, DNA methylation and microRNA expression in vitro. |

1. What are the epigenetics changes conferred by DEP exposure? When do they occur developmentally? Who is at most risk? How long do the epigenetic changes last? |

| 2. Exposure to DEP causes changes in DNA methylation and microRNA expression in human samples. |

2. How does DEP induce epigenetic changes? |

| 3. The differentiation of naïve T cell into Th1, Th2, Th17 and Treg cells are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, and these processes are affected by DEP exposure. |

3. How are the differentiation/maturation of cells mediating responses to DEP including T cells regulated epigenetically? |

Genome wide association studies (GWAS) represent a powerful tool for investigating the genetics of common diseases and have successfully identified several genetic variants associated with exposure to air particulates. However, findings from these studies are largely limited to common or imputed single nucleotide polymorphisms, which likely confer small increases in risk87. Rarer variants present in less than 5% of population that are poorly detected by available genotyping arrays possibly have larger effects. In order to more fully define the genetic influence that modifies responses to environmental pollutants, longitudinal studies designed to assess early life exposure are required. Non-SNP variants including copy number variation and copy neutral variation need to be included in future studies. Identification of rare variants by exome or whole genome sequencing, use of shared datasets provided by the 1000 Genomes Project, and the design of meta-studies with consistently well-defined phenotypes across large population sets will greatly advance the development of genetic studies.

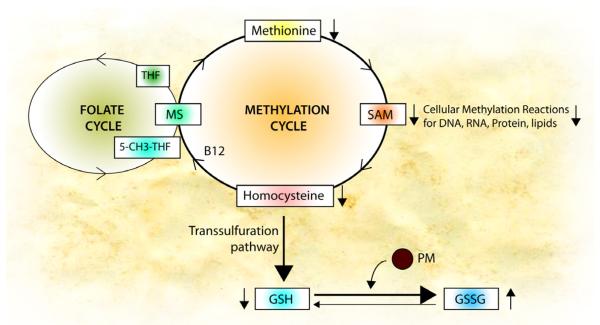

How PM causes epigenetic changes is an intriguing question. Genetic variations in glutathione-s-transferases (GSTP1 and GSTM1) have been identified as potential modifiers of the responses to PM. GSTs represent a major group of detoxification enzymes, and their substrate glutathione (GSH) is produced through transsulfuration pathway from cysteine, which is connected with the methylation cycle and the folate cycle (Figure 2). In conditions with high oxidative stress and low GSH, such as autism88 and severe asthma89, the enhanced need to synthesize GSH could potentially impair biosynthesis of SAM (S-adenoylmethionine, the major methyl donor for most methyltransferases that modify DNA, RNA, histones and other proteins) and perturb DNA methylation90. In support of this, diets lacking sources of methyl-groups (folic acid, B12, choline and betaine) result in global and gene-specific DNA hypomethylation91. DEP exposure itself can contribute to oxidative stress; in vitro exposure to DEP induced a decrease in the cellular GSH:GSSG ratio31. Thus in early life, this may be a mechanism by which PM could affect global and specific gene methylation. One might postulate that PM may influence the methylation cycle by depleting glutathione, thus promoting epigenetic changes. It is also been proposed that oxidative stress can affect global epigenetic patterns by interfering with metabolism, and thereby activating TET and other chromatin modifiers92. Moreover, histone acetylation changes induced by DEP in vitro can be countered in part by the addition of antioxidants72, thus, there may be an opportunity for targeted intervention in high risk infants aimed at disease prevention.

Figure 2. Potential mechanism by which PM affects epigenome.

Oxidative stress generated by PM may interfere the methylation cycle by depleting glutathione, thus promoting epigenetic changes. Levels of SAM (S-adenoylmethionine, the methyl-donor) are maintained by the methylation cycle. After SAM donates its methyl group, it is converted into homocysteine, which recycles back to SAM (SAM- >homocysteine ->methionine ->SAM). This recycling is catalyzed by methionine synthase (MS), which requires an active form of B12 (methylcobalamin) and folate (5-methyl-THF). PM induces oxidation of glutathione (GSH) to GSSG and decreases the levels of homocysteine in the methylation cycle. Thus, cellular levels of methionine and SAM decrease, resulting in reduced methylation of DNA, RNA, protein and lipids.

An epigenetic origin of disease has been suggested based on the observations linking early life exposure with later disease. Birth cohort studies have revealed that early life exposure (before age 1) to DEP leads to persistent wheezing37, 38. It will be necessary to determine the developmental origins of this susceptibility in order to develop interventions aimed at prevention of disease during this critical window in early life. Epigenetic patterns associated with specific environmental pollutants may be useful biomarkers to determine the long-term effects of early exposure to environmental pollutants on human health, although many questions remain to be answered6. Epigenetic modifications may turn on or off gene expression inappropriately; or may mask or unmask DNA sequence variation that has disease consequences. Studies in twins and healthy controls identified genetic variations that were associated with nearby differences in DNA methylation93. In the same study, the heritability estimate in DNA methylation at 96 CpG sites out of 431 CpG sites examined was as high as 94%. Therefore, integrating epigenetics into genetics studies to study their influences on responses to environmental pollutants will greatly help to identify risk factors and better understand the pathogenesis of diseases associated with environmental pollution.

To study epigenetic makers associated with environmental pollutants, the most optimal epigenetic methodology has to be utilized. Research to date has been utilizing methylation of repeat elements as indicators of global methylation. Whether methylation of repeat elements can be used as markers for pathological diseases or specific exposure requires further investigation because the methylation status of these elements is influenced by inter-individual variability and gender specific variation94, 95. With the development of newer technologies, more discovery-oriented approaches can be utilized to identify epigenetic responses to air pollutants. Statistical tools and concepts are being developed to analyze, interpret and compare population-level epigenetic data. Another limitation of environmental epigenomic studies is sample choice. The most common samples studied include blood, buccal cells, cord blood and skin cells. Whether these are legitimate surrogate tissues for airway cells needs to be carefully evaluated. Continued research is necessary to understand how DEP is recognized in the airways and what cellular pathways initiate and mediate innate and adaptive immune responses to DEP that promote adverse health effects.

Abbreviations

- 5hmC

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- CCAAPS

Cincinnati Childhood Allergy and Air Pollution study

- DC

dendritic cell

- DEP

diesel exhaust particles

- DNMT1

DNA methyltransferase 1

- DNMT3a

DNA methyltransferase 3a

- DNMT3b

DNA methyltransferase 3b

- ETS

environmental tobacco smoke

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- HDM

house dust mite

- PAH

polyaromatic hydrocarbon

- PM

particulate matter

- TET

Ten-Eleven-Translocation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19A170235 (GKKH) and R01HL098134 (GKKH).

References

- 1.Zanobetti A, Bind MA, Schwartz J. Particulate air pollution and survival in a COPD cohort. Environmental health: a global access science source. 2008;7:48. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peden D, Reed CE. Environmental and occupational allergies. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;125:S150–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelucchi C, Negri E, Gallus S, Boffetta P, Tramacere I, La Vecchia C. Long-term particulate matter exposure and mortality: a review of European epidemiological studies. BMC public health. 2009;9:453. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang IA, Fong KM, Zimmerman PV, Holgate ST, Holloway JW. Genetic susceptibility to the respiratory effects of air pollution. Thorax. 2008;63:555–63. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.079426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jardim MJ. microRNAs: Implications for air pollution research. Mutation research. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho SM. Environmental epigenetics of asthma: an update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:453–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanobetti A, Baccarelli A, Schwartz J. Gene-air pollution interaction and cardiovascular disease: a review. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2011;53:344–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peden DB. Pollutants and asthma: role of air toxics. Environmental health perspectives. 2002;110(Suppl 4):565–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzivian L. Outdoor air pollution and asthma in children. The Journal of asthma: official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2011;48:470–81. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.570407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigg J. Particulate matter exposure in children: relevance to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009;6:564–9. doi: 10.1513/pats.200905-026RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riedl M, Diaz-Sanchez D. Biology of diesel exhaust effects on respiratory function. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2005;115:221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.047. quiz 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao GG, Wang M, Li N, Loo JA, Nel AE. Use of proteomics to demonstrate a hierarchical oxidative stress response to diesel exhaust particle chemicals in a macrophage cell line. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:50781–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvi S, Blomberg A, Rudell B, Kelly F, Sandstrom T, Holgate ST, et al. Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;159:702–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9709083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenfors N, Nordenhall C, Salvi SS, Mudway I, Soderberg M, Blomberg A, et al. Different airway inflammatory responses in asthmatic and healthy humans exposed to diesel. The European respiratory journal: official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 2004;23:82–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00004603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvi SS, Nordenhall C, Blomberg A, Rudell B, Pourazar J, Kelly FJ, et al. Acute exposure to diesel exhaust increases IL-8 and GRO-alpha production in healthy human airways. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;161:550–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9905052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier KL, Alessandrini F, Beck-Speier I, Hofer TP, Diabate S, Bitterle E, et al. Health effects of ambient particulate matter--biological mechanisms and inflammatory responses to in vitro and in vivo particle exposures. Inhalation toxicology. 2008;20:319–37. doi: 10.1080/08958370701866313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz-Sanchez D, Penichet-Garcia M, Saxon A. Diesel exhaust particles directly induce activated mast cells to degranulate and increase histamine levels and symptom severity. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2000;106:1140–6. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.111144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz-Sanchez D, Tsien A, Fleming J, Saxon A. Combined diesel exhaust particulate and ragweed allergen challenge markedly enhances human in vivo nasal ragweed-specific IgE and skews cytokine production to a T helper cell 2-type pattern. Journal of immunology. 1997;158:2406–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyabara Y, Ichinose T, Takano H, Lim HB, Sagai M. Effects of diesel exhaust on allergic airway inflammation in mice. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1998;102:805–12. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichinose T, Takano H, Miyabara Y, Sadakaneo K, Sagai M, Shibamoto T. Enhancement of antigen-induced eosinophilic inflammation in the airways of mast-cell deficient mice by diesel exhaust particles. Toxicology. 2002;180:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takenaka H, Zhang K, Diaz-Sanchez D, Tsien A, Saxon A. Enhanced human IgE production results from exposure to the aromatic hydrocarbons from diesel exhaust: direct effects on B-cell IgE production. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1995;95:103–15. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terada N, Maesako K, Hiruma K, Hamano N, Houki G, Konno A, et al. Diesel exhaust particulates enhance eosinophil adhesion to nasal epithelial cells and cause degranulation. International archives of allergy and immunology. 1997;114:167–74. doi: 10.1159/000237663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang HM, Ma JY, Castranova V, Ma JK. Effects of diesel exhaust particles on the release of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha from rat alveolar macrophages. Experimental lung research. 1997;23:269–84. doi: 10.3109/01902149709087372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito Y, Azuma A, Kudo S, Takizawa H, Sugawara I. Effects of diesel exhaust on murine alveolar macrophages and a macrophage cell line. Experimental lung research. 2002;28:201–17. doi: 10.1080/019021402753570509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terada N, Hamano N, Maesako KI, Hiruma K, Hohki G, Suzuki K, et al. Diesel exhaust particulates upregulate histamine receptor mRNA and increase histamine-induced IL-8 and GM-CSF production in nasal epithelial cells and endothelial cells. Clinical and experimental allergy: journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999;29:52–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Provoost S, Maes T, Willart MA, Joos GF, Lambrecht BN, Tournoy KG. Diesel exhaust particles stimulate adaptive immunity by acting on pulmonary dendritic cells. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:426–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter M, Karp M, Killedar S, Bauer SM, Guo J, Williams D, et al. Diesel-enriched particulate matter functionally activates human dendritic cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2007;37:706–19. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0199OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue K, Koike E, Takano H, Yanagisawa R, Ichinose T, Yoshikawa T. Effects of diesel exhaust particles on antigen-presenting cells and antigen-specific Th immunity in mice. Experimental biology and medicine. 2009;234:200–9. doi: 10.3181/0809-RM-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romieu I, Moreno-Macias H, London SJ. Gene by environment interaction and ambient air pollution. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:116–22. doi: 10.1513/pats.200909-097RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Xiao GG, Li N, Xie Y, Loo JA, Nel AE. Use of a fluorescent phosphoprotein dye to characterize oxidative stress-induced signaling pathway components in macrophage and epithelial cultures exposed to diesel exhaust particle chemicals. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2092–108. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitekus MJ, Li N, Zhang M, Wang M, Horwitz MA, Nelson SK, et al. Thiol antioxidants inhibit the adjuvant effects of aerosolized diesel exhaust particles in a murine model for ovalbumin sensitization. Journal of immunology. 2002;168:2560–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaimul Ahsan M, Nakamura H, Tanito M, Yamada K, Utsumi H, Yodoi J. Thioredoxin-1 suppresses lung injury and apoptosis induced by diesel exhaust particles (DEP) by scavenging reactive oxygen species and by inhibiting DEP-induced downregulation of Akt. Free radical biology & medicine. 2005;39:1549–59. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li N, Xia T, Nel AE. The role of oxidative stress in ambient particulate matter-induced lung diseases and its implications in the toxicity of engineered nanoparticles. Free radical biology & medicine. 2008;44:1689–99. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens T, Cho SH, Linak WP, Gilmour MI. Differential potentiation of allergic lung disease in mice exposed to chemically distinct diesel samples. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2009;107:522–34. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tal TL, Simmons SO, Silbajoris R, Dailey L, Cho SH, Ramabhadran R, et al. Differential transcriptional regulation of IL-8 expression by human airway epithelial cells exposed to diesel exhaust particles. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2010;243:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemmar A, Hoylaerts MF, Hoet PH, Nemery B. Possible mechanisms of the cardiovascular effects of inhaled particles: systemic translocation and prothrombotic effects. Toxicology letters. 2004;149:243–53. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroer KT, Biagini Myers JM, Ryan PH, LeMasters GK, Bernstein DI, Villareal M, et al. Associations between multiple environmental exposures and Glutathione S-Transferase P1 on persistent wheezing in a birth cohort. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;154:401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.040. 8 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan PH, Bernstein DI, Lockey J, Reponen T, Levin L, Grinshpun S, et al. Exposure to traffic-related particles and endotoxin during infancy is associated with wheezing at age 3 years. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:1068–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilliland FD, Li YF, Saxon A, Diaz-Sanchez D. Effect of glutathione-S-transferase M1 and P1 genotypes on xenobiotic enhancement of allergic responses: randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. Lancet. 2004;363:119–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilliland FD, Li YF, Gong H, Jr., Diaz-Sanchez D. Glutathione s-transferases M1 and P1 prevent aggravation of allergic responses by secondhand smoke. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2006;174:1335–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1424OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salam MT, Lin PC, Avol EL, Gauderman WJ, Gilliland FD. Microsomal epoxide hydrolase, glutathione S-transferase P1, traffic and childhood asthma. Thorax. 2007;62:1050–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.080127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kerkhof M, Postma DS, Brunekreef B, Reijmerink NE, Wijga AH, de Jongste JC, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 genes influence susceptibility to adverse effects of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma. Thorax. 2010;65:690–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salam MT, Gauderman WJ, McConnell R, Lin PC, Gilliland FD. Transforming growth factor- 1 C-509T polymorphism, oxidant stress, and early-onset childhood asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;176:1192–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-561OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michel S, Liang L, Depner M, Klopp N, Ruether A, Kumar A, et al. Unifying candidate gene and GWAS Approaches in Asthma. PloS one. 2010;5:e13894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochedlinger K, Blelloch R, Brennan C, Yamada Y, Kim M, Chin L, et al. Reprogramming of a melanoma genome by nuclear transplantation. Genes & development. 2004;18:1875–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1213504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zemach A, McDaniel IE, Silva P, Zilberman D. Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of eukaryotic DNA methylation. Science. 2010;328:916–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1186366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ooi SK, Bestor TH. The colorful history of active DNA demethylation. Cell. 2008;133:1145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iqbal K, Jin SG, Pfeifer GP, Szabo PE. Reprogramming of the paternal genome upon fertilization involves genome-wide oxidation of 5-methylcytosine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:3642–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wossidlo M, Nakamura T, Lepikhov K, Marques CJ, Zakhartchenko V, Boiani M, et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian zygote is linked with epigenetic reprogramming. Nature communications. 2011;2:241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuroda A, Rauch TA, Todorov I, Ku HT, Al-Abdullah IH, Kandeel F, et al. Insulin gene expression is regulated by DNA methylation. PloS one. 2009;4:e6953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doi A, Park IH, Wen B, Murakami P, Aryee MJ, Irizarry R, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nature genetics. 2009;41:1350–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Seita J, Murakami P, Doi A, Lindau P, et al. Comprehensive methylome map of lineage commitment from haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2010;467:338–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nature genetics. 2009;41:178–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, Mosammaparast N, Wang JK, Lan F, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raisner RM, Hartley PD, Meneghini MD, Bao MZ, Liu CL, Schreiber SL, et al. Histone variant H2A.Z marks the 5′ ends of both active and inactive genes in euchromatin. Cell. 2005;123:233–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, et al. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell. 2010;140:678–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:1057–68. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noonan EJ, Place RF, Pookot D, Basak S, Whitson JM, Hirata H, et al. miR-449a targets HDAC-1 and induces growth arrest in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:1714–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, Liu Z, Zanesi N, Callegari E, et al. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:15805–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li YF, Langholz B, Salam MT, Gilliland FD. Maternal and grandmaternal smoking patterns are associated with early childhood asthma. Chest. 2005;127:1232–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tobi EW, Lumey LH, Talens RP, Kremer D, Putter H, Stein AD, et al. DNA methylation differences after exposure to prenatal famine are common and timing- and sex-specific. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:4046–53. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, Putter H, Blauw GJ, Susser ES, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:17046–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806560105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reponen T, Vesper S, Levin L, Johansson E, Ryan P, Burkle J, et al. High environmental relative moldiness index during infancy as a predictor of asthma at 7 years of age. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology: official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2011;107:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, Gilliland FD. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:462–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0135OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suter M, Abramovici A, Showalter L, Hu M, Shope CD, Varner M, et al. In utero tobacco exposure epigenetically modifies placental CYP1A1 expression. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2010;59:1481–90. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waterland RA, Lin JR, Smith CA, Jirtle RL. Post-weaning diet affects genomic imprinting at the insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf2) locus. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15:705–16. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:10604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perera F, Tang WY, Herbstman J, Tang D, Levin L, Miller R, et al. Relation of DNA methylation of 5′-CpG island of ACSL3 to transplacental exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and childhood asthma. PloS one. 2009;4:e4488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gilmour PS, Rahman I, Donaldson K, MacNee W. Histone acetylation regulates epithelial IL-8 release mediated by oxidative stress from environmental particles. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2003;284:L533–40. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00277.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cao D, Bromberg PA, Samet JM. COX-2 expression induced by diesel particles involves chromatin modification and degradation of HDAC1. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2007;37:232–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0449OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jardim MJ, Fry RC, Jaspers I, Dailey L, Diaz-Sanchez D. Disruption of microRNA expression in human airway cells by diesel exhaust particles is linked to tumorigenesis-associated pathways. Environmental health perspectives. 2009;117:1745–51. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bollati V, Marinelli B, Apostoli P, Bonzini M, Nordio F, Hoxha M, et al. Exposure to metal-rich particulate matter modifies the expression of candidate microRNAs in peripheral blood leukocytes. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:763–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akbari O, Freeman GJ, Meyer EH, Greenfield EA, Chang TT, Sharpe AH, et al. Antigen-specific regulatory T cells develop via the ICOS-ICOS-ligand pathway and inhibit allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Nature medicine. 2002;8:1024–32. doi: 10.1038/nm745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hadeiba H, Locksley RM. Lung CD25 CD4 regulatory T cells suppress type 2 immune responses but not bronchial hyperreactivity. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:5502–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim HP, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1543–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nadeau K, McDonald-Hyman C, Noth EM, Pratt B, Hammond SK, Balmes J, et al. Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;126:845–52. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tarantini L, Bonzini M, Apostoli P, Pegoraro V, Bollati V, Marinelli B, et al. Effects of particulate matter on genomic DNA methylation content and iNOS promoter methylation. Environmental health perspectives. 2009;117:217–22. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Madrigano J, Baccarelli A, Mittleman MA, Wright RO, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, et al. Prolonged Exposure to Particulate Pollution, Genes Associated With Glutathione Pathways, and DNA Methylation in a Cohort of Older Men. Environmental health perspectives. 2011 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baccarelli A, Wright RO, Bollati V, Tarantini L, Litonjua AA, Suh HH, et al. Rapid DNA methylation changes after exposure to traffic particles. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;179:572–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1097OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pavanello S, Bollati V, Pesatori AC, Kapka L, Bolognesi C, Bertazzi PA, et al. Global and gene-specific promoter methylation changes are related to anti-B[a]PDE-DNA adduct levels and influence micronuclei levels in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-exposed individuals. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2009;125:1692–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yauk C, Polyzos A, Rowan-Carroll A, Somers CM, Godschalk RW, Van Schooten FJ, et al. Germ-line mutations, DNA damage, and global hypermethylation in mice exposed to particulate air pollution in an urban/industrial location. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:605–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705896105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu J, Ballaney M, Al-alem U, Quan C, Jin X, Perera F, et al. Combined inhaled diesel exhaust particles and allergen exposure alter methylation of T helper genes and IgE production in vivo. Toxicological sciences: an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2008;102:76–81. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ege MJ, Strachan DP, Cookson WO, Moffatt MF, Gut I, Lathrop M, et al. Gene-environment interaction for childhood asthma and exposure to farming in Central Europe. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;127:138–44. 44 e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.James SJ, Cutler P, Melnyk S, Jernigan S, Janak L, Gaylor DW, et al. Metabolic biomarkers of increased oxidative stress and impaired methylation capacity in children with autism. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2004;80:1611–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fitzpatrick AM, Teague WG, Burwell L, Brown MS, Brown LA. Glutathione oxidation is associated with airway macrophage functional impairment in children with severe asthma. Pediatric research. 2011;69:154–9. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee DH, Jacobs DR, Jr., Porta M. Hypothesis: a unifying mechanism for nutrition and chemicals as lifelong modulators of DNA hypomethylation. Environmental health perspectives. 2009;117:1799–802. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:5293–300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang L, Chia NC, Lu X, Ruden DM. Hypothesis: Environmental regulation of 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine by oxidative stress. Epigenetics: official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2011;6 doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boks MP, Derks EM, Weisenberger DJ, Strengman E, Janson E, Sommer IE, et al. The relationship of DNA methylation with age, gender and genotype in twins and healthy controls. PloS one. 2009;4:e6767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.El-Maarri O, Becker T, Junen J, Manzoor SS, Diaz-Lacava A, Schwaab R, et al. Gender specific differences in levels of DNA methylation at selected loci from human total blood: a tendency toward higher methylation levels in males. Human genetics. 2007;122:505–14. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El-Maarri O, Walier M, Behne F, van Uum J, Singer H, Diaz-Lacava A, et al. Methylation at global LINE-1 repeats in human blood are affected by gender but not by age or natural hormone cycles. PloS one. 2011;6:e16252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]