SYNOPSIS

Objectives

In October 2008, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) was diagnosed in a driver who had transported 762 passengers in the District of Columbia metropolitan area during his infectious period. A passenger contact investigation was conducted by the six public health jurisdictions because of concern that some passengers might be infected with HIV or have other medical conditions that put them at increased risk for developing TB disease if infected.

Methods

Authorities evaluated 92 of 100 passengers with at least 90 minutes of cumulative exposure. Passengers with fewer than 90 minutes of cumulative exposure were evaluated if they had contacted the health department after exposure and had a medical condition that increased their risk of TB. A tuberculin skin test (TST) result of at least 5 millimeters induration was considered positive.

Results

Of 153 passengers who completed TST evaluation, 11 (7%) had positive TST results. TST results were not associated with exposure time or high-risk medical conditions. No TB cases were identified in the passengers.

Conclusions

The investigation yielded insufficient evidence that Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission to passengers had occurred. TB-control programs should consider transportation-related passenger contact investigations low priority unless exposure is repetitive or single-trip exposure is long.

In September 2008, a 54-year-old U.S.-born male resident of the District of Columbia (DC) with no history of travel outside of the United States reported a three-month history of cough, night sweats, shortness of breath, weight loss, and fatigue. Initial treatment for community-acquired pneumonia did not resolve symptoms. In October 2008, a tuberculin skin test (TST) result was positive, and chest radiography revealed a left upper-lobe opacity and hilar lymphadenopathy. Sputum examination was positive for acid-fast bacilli, and a nucleic acid amplification test was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) complex.1 The sputum culture grew M. tuberculosis, and the isolate was susceptible to all standard first-line TB drugs (i.e., isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide). The M. tuberculosis genotype was unique in the U.S. National TB Genotyping Service database.2

The patient worked as a driver for a medical transportation company that provided services to passengers whose medical conditions limited their ability to use public transportation. He transported passengers in a four-door sedan to medical appointments in the metropolitan-DC area. The passengers resided in six metropolitan-DC jurisdictions (i.e., DC, two counties in Maryland, and three counties in Virginia). Upon diagnosis, the patient began medical leave to begin treatment and prevent further passenger exposures. In November 2008, the transportation company sent notification letters to the 762 passengers transported by the driver during his estimated six-month infectious period, which began in April 2008 and ended in October 2008.3 However, the transportation company did not release the passengers' ages, disability status, or medical conditions to public health authorities. The lack of information complicated the decision to initiate a passenger contact investigation by public health authorities in the six affected jurisdictions.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend assigning a low priority to transportation-related contact investigations unless ventilation in the mode of transportation is restricted or the exposure is repetitive or long (i.e., more than eight hours of cumulative exposure during a single trip).3 However, few studies have reported on M. tuberculosis transmission in automobiles. The majority of published reports on transportation-related contact investigations have focused on transmission of M. tuberculosis during air travel with long cumulative exposures.4–7 Investigations among contacts to infectious TB disease have two primary objectives: (1) identify and treat contacts with TB disease to prevent additional M. tuberculosis transmission and (2) identify and treat contacts with M. tuberculosis infection to prevent future TB disease.3 Contacts with medical conditions that increase the risk of progression from M. tuberculosis infection to TB disease (e.g., end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, or immunosuppressant medication use) are considered high priority for both evaluation and treatment.3,8

HIV infection is a strong risk factor for TB disease after infection with M. tuberculosis. so contacts with HIV infection are assigned high priority for evaluation during contact investigations. In 2008, an estimated 3% of DC residents were living with HIV infection, exceeding the 1% epidemic threshold in a specific geographic area in the United States.9 Considering the high background prevalence of HIV infection in the metropolitan-DC jurisdictions, and because passengers using the transportation company had unknown medical conditions that limited their ability to use public transportation, authorities were concerned that some passengers might be infected with HIV or have other medical conditions that put them at increased risk for developing TB disease if infected. Additionally, ventilation in the automobile had not been assessed. Therefore, during November 2008 through January 2010, a passenger contact investigation was conducted by the six public health jurisdictions.

METHODS

Because the medical conditions of the passengers were unknown, public health authorities collectively chose a conservative 90-minute cumulative exposure threshold for offering TB evaluation. Passengers with at least 90 minutes of cumulative exposure time to the driver were considered high priority for evaluation. These high-priority passengers were contacted via telephone and interviewed with a standardized data collection form, which included questions about signs and symptoms of TB disease, end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, HIV infection, and immunosuppressant medication use. Regardless of signs and symptoms of TB disease or medical history, authorities referred all passengers with at least 90 minutes of cumulative exposure to the local health department for evaluation.

Passengers with fewer than 90 minutes of cumulative exposure to the driver were not actively contacted, but those who called a health jurisdiction were interviewed using the same form. Passengers initially classified as low priority based on cumulative exposure time but who reported signs or symptoms of TB disease or a medical condition that increased the risk of progression to TB disease (i.e., end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis, HIV infection, or immunosuppressant medication use)3,9 were reclassified as high priority. Passengers with fewer than 90 minutes of cumulative exposure, no self-reported signs or symptoms of TB disease, and no medical risk factors for TB disease were counseled that the risk of M. tuberculosis transmission was probably low; however, passengers who requested testing were referred to the local health department for evaluation.

For passengers without a history of positive TST results or current evidence of TB disease, the evaluation included a TST. On the basis of CDC guidelines, passengers were tested at least eight weeks following their last exposure to the driver and a TST result of at least 5 millimeters induration was considered positive, indicative of M. tuberculosis infection. Passengers who had a positive TST result were referred for further clinical evaluation and chest radiograph to exclude TB disease. Passengers who reported a prior positive TST result or a history of M. tuberculosis infection or TB disease were referred for further clinical evaluation and chest radiograph to exclude current TB disease.3 All passengers with newly identified positive TST results or a history of M. tuberculosis infection without treatment were offered treatment for infection after TB disease had been excluded.

RESULTS

One hundred out of 762 passengers (13%) had at least 90 minutes of cumulative exposure time (Figure). Of these 100 passengers, 92 (92%) were interviewed and eight (8%) could not be located. Of 662 passengers with fewer than 90 minutes of cumulative exposure time, 242 (37%) contacted a health department and were interviewed. Seventy-six of the 242 passengers who contacted a health department (31%) were reclassified as high priority based on medical history; further evaluation was not recommended for the other 166 (69%) low-priority passengers. However, 29 low-priority passengers sought testing despite counseling, and their results are included in the analysis. Of the 168 high-priority passengers interviewed, 124 (74%) completed evaluations. Forty-four (26%) high-priority passengers were excluded from analysis: 19 (11%) had a history of prior latent M. tuberculosis infection, and 25 (15%) had incomplete or no evaluations. The Table presents the characteristics and TST results of 153 passengers who completed evaluations: 124 (81%) high-priority passengers and 29 (19%) low-priority passengers. No passengers who completed evaluations had TB disease diagnosed.

Figure.

Evaluations of passengers who were exposed to a transport driver with infectious TB in six metropolitan areas of the District of Columbia:a November 2008–January 2009

aAs of May 2011

TB = tuberculosis

M. tuberculosis = Mycobacterium tuberculosis

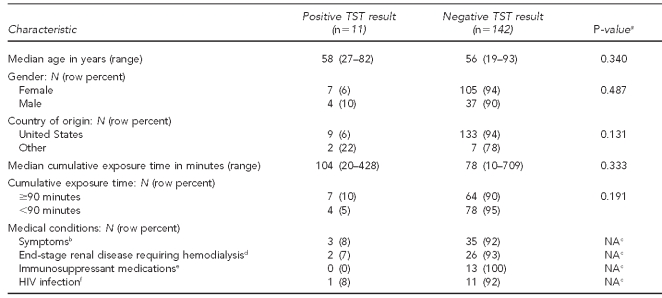

Table.

Tuberculin skin test results for 153 passengers who were exposed to a transport driver with infectious TB, stratified by passenger characteristics, in six metropolitan areas of the District of Columbia: November 2008–January 2009

aP-values correspond to Wilcoxon ranked sum test or the Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

bTB symptoms included coughing up blood, chronic cough >3 weeks, soaking night sweats, chronic fatigue, weight loss, or fever.

cThere was no difference in the percentage of passengers with these conditions and those without these conditions who had positive TST results.

dMissing for one passenger with ≥90 minutes of cumulative exposure

eMedications included >15 milligrams of prednisone or its equivalent for >4 weeks, chemotherapy agents, antirejection drugs for organ transplantation, or tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists.

fMissing for five passengers; two had ≥90 minutes and three had <90 minutes of cumulative exposure

TB = tuberculosis

TST = tuberculin skin test

NA = not applicable

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

A total of 11 (7%) passengers had positive TST results; seven (10%) had at least 90 minutes and four (5%) had fewer than 90 minutes of cumulative exposure time. Positive TST results were not associated with gender, country of origin, exposure time, or presence of specified medical conditions. Eight (73%) of the 11 passengers with positive TST results initiated treatment for latent M. tuberculosis infection. Of the eight passengers who initiated treatment, three (38%) completed treatment.

As of May 2011, more than two years following the investigation, the driver's M. tuberculosis genotype remains unique in the U.S. National TB Genotyping Service database. The contact investigation required an estimated total of 1,200 hours of staff time.

DISCUSSION

Previous published studies have investigated M. tuberculosis transmission aboard military ships, commercial aircraft, passenger trains, commuter vans, and school buses, but none has estimated the risk of M. tuberculosis transmission in an automobile.4–7,10–13 In this investigation, cumulative exposure time was not significantly associated with positive TST results, although the small number of participants limited the study's statistical power to detect such a difference. Therefore, inferences about the scope of M. tuberculosis transmission to passengers stratified by cumulative exposure time to the driver should be limited. However, the 7% prevalence of M. tuberculosis infection among the passengers evaluated was lower than the expected 30% for community contact investigations14 and did not exceed the estimated 5%–9% background prevalence of M. tuberculosis infection for this population.15 The evidence that passengers did not have a higher rate of positive TST results than the background prevalence suggests that M. tuberculosis transmission was rare or did not occur in this transportation setting. Therefore, expansion of the contact investigation to the remaining low-priority passengers was considered unnecessary.

This investigation was conducted, in part, because of the concern that passengers had medical risk factors that conferred an increased risk of progression to TB disease if infected. False-negative results are a known limitation of using TSTs in people with immunosuppression.9 However, more than two years after the driver's diagnosis, no additional cases of TB disease with the driver's strain of M. tuberculosis have been identified among passengers, in the metropolitan-DC area or elsewhere in the United States. Because contacts are most likely to develop TB disease within two years of infection,3,8 the absence of TB disease among passengers provides additional evidence that M. tuberculosis transmission in this setting was unlikely.

CONCLUSIONS

Decisions about initiating transportation-related contact investigations have become more complicated as recent high-profile investigations have focused the attention of the media and public on TB disease.5 However, the value of intensive TB contact investigations in transportation-related settings remains unclear.4,6,7,10–12 This investigation yielded insufficient evidence that M. tuberculosis transmission from the driver to medically fragile passengers occurred. In addition, only 27% of passengers diagnosed with latent M. tuberculosis infection completed treatment, which is well below the national target of 85%.3,16 Despite the low yield, the investigation was resource-intensive, requiring an estimated 1,200 hours of staff time. To focus limited resources, TB-control programs should consider transportation-related passenger contact investigations to be low priority unless ventilation in the mode of transportation is restricted or the exposure is repetitive or long.3

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the health departments and staff for their assistance with the investigation. The authors also thank Ghasi Phillips, Laura Polakowski, and Rakhee Palekar for assistance with data collection; Roque Miramontes for assistance with data collection and technical support for the investigation; and Maryam Haddad and Thomas Navin for their insightful review of the article. Genotyping was performed by Laura Guild, Rebecca Kramer, and Sonia Lugo, with funding by a contract from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Footnotes

This investigation did not require Institutional Review Board review because it was conducted during a response to a public health emergency. The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of CDC or the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(1):7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Notice to readers: new CDC program for rapid genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(2):47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor Z. Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis: recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-15):1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driver CR, Valway SE, Morgan WM, Onorato IM, Castro KG. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with air travel. JAMA. 1994;272:1031–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buff AM, Wiersma P, Sales R, DeVoe P, Marineau K, Harrington T. Investigation of an international traveler with suspected extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis—United States, 2007. Abstract presented at the 57th Annual Conference of the Epidemic Intelligence Service; 2008 Apr 14-18; Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marienau KJ, Burgess GW, Cramer E, Averhoff FM, Buff AM, Russell M, et al. Tuberculosis investigations associated with air travel: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2007-June 2008. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2010;8:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornylo-Duong K, Kim C, Cramer EH, Buff AM, Rodriguez-Howell D, Doyle J, et al. Three travel-related contact investigations associated with infectious tuberculosis, 2007-2008. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2010;8:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiter LJ, Gordin FM, Hershfield E, Horsburgh CR, Jr, Jereb JA, Jordan TJ, et al. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49(RR-6):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of the District of Columbia Department of Health. Washington: Government of the District of Columbia Department of Health; 2009. [cited 2010 Oct 5]. District of Columbia HIV/AIDS epidemiology update 2008. Also available from: URL: http://dchealth.dc.gov/DOH/frames.asp?doc=/doh/lib/doh/pdf/dc_hiv-aids_2008_updatereport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buff AM, Deshpande SJ, Harrington TA, Wofford TS, O'Hara TW, Carrigan K, et al. Investigation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission aboard the U.S.S. Ronald Reagan, 2006. Mil Med. 2008;173:588–93. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.6.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore M, Valway SE, Ihle W, Onorato IM. A train passenger with pulmonary tuberculosis: evidence of limited transmission during travel. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:52–6. doi: 10.1086/515089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horna-Campos OJ, Sanchez-Perez HJ, Sanchez I, Bedoya A, Martin M. Public transportation and pulmonary tuberculosis, Lima, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1491–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.060793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neira-Munoz E, Smith J, Cockcroft P, Basher D, Abubakar I. Extensive transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis among children on a school bus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:835–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816ff7c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States: recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54(45):1161] MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-12):1–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett DE, Courval JM, Onorato I, Agerton T, Gibson JD, Lambert L, et al. Prevalence of tuberculosis infection in the United States population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:348–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-057OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]