Abstract

BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mice show abnormal social, communicatory, and repetitive/stereotyped behaviors paralleling many of the symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. BTBR also show agenesis of the corpus callosum (CC) suggesting major perturbations of growth or guidance factors in the dorsal forebrain [1]. Heparan sulfate (HS) is a polysaccaride found in the brain and other animal tissues. It binds to a wide variety of ligands and through these ligands modulates a number of biological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation, migration and guidance. It is aggregated on fractal-like structures (fractones) in the subventricular zone (SVZ), that may be visualized by laminin immunoreactivity (LAM-ir), as well as by HS immunoreactivity (HS-ir). We report that the lateral ventricles of BTBR mice were drastically reduced in area compared to C57BL/6J (B6) mice while the BTBR SVZ was significantly shorter than that of B6. In addition to much smaller fractones for BTBR, both HS and LAM-ir associated with fractones were significantly reduced in BTBR, and their anterior-posterior distributions were also altered. Finally, the ratio of HS to LAM in individual fractones was significantly higher in BTBR than in B6 mice. These data, in agreement with other findings linking HS to callosal development, suggest that variations in the quantity and distribution of HS in the SVZ of the lateral ventricles may be important modulators of the brain structural abnormalities of BTBR mice, and, potentially, contribute to the behavioral pathologies of these animals.

Keywords: BTBR T+tf/J, autism, heparan sulfates, fractones, laminin, ventricles

1. Introduction

Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have become increasingly common in the past decade and now may involve nearly 1% of young children [2,3,4,5]. Although there is considerable evidence for a strong genetic factor in autism [6], it appears to be polygenic, with hundreds of contributing loci [7,8]. In addition, a range of environmental factors including fetal exposure to teratogens appear to influence rates of ASD [9,10]). The defining symptoms of ASD are behavioral, and, while a number of neural features are known to be associated with these disorders [11,12,13] it is questionable whether these features are sufficiently robust and specific as to suggest underlying neural mechanisms.

The definition of ASD in terms of three major symptom clusters: social interaction deficits, communication deficits, and ritualistic-repetitive behaviors; all typically detectable in early childhood but continuing throughout life [14,15,16], has put an extraordinary emphasis on the development of animal models displaying behaviors that are relevant to these symptoms. In this context, the inbred BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mouse has emerged as a particularly strong model. Adult BTBR mice display low levels of social behavior [17,18,19], including specific avoidance of oriented nose to nose contact [20]; poor social learning in the transmission-of-food-preference assay [18]; lower levels of vocalization [21] and higher levels of repetitive self-grooming [18, 22,23,24] and cognitive stereotypies [25,26], compared to other mouse strains tested. They also show an unusual repertory of pup separation ultrasonic vocalizations [27] as well as adult ultrasonic calls [28]. These changes in BTBR mice may be relatively specific, as they are not attributable to low locomotor activity [29] or a general enhancement in emotional responsivity [18,19,22,30,31,32].

The BTBR mouse also displays some consistent neuroanatomical differences from most other mouse strains, including total absence of the corpus callosum (CC) and reductions in the hippocampal commissure [1,33]). As surgical lesions of CC at postnatal day 7 (PND7) in C57BL/6J (B6) mice do not produce juvenile or adult social changes, or grooming enhancement, the autism-relevant behaviors displayed by BTBR mice are not a direct consequence of callosal damage after this time [22], although it is possible that the lack of a CC between embryonic day 15 (E15) and PND7 might be relevant. However, the magnitude and consistency of these structural changes in BTBR suggest some major perturbation of cell genesis or guidance factors in this strain, and these perturbations may have effects on autistic-like behaviors that do not directly involve the CC.

Heparan sulfates (HS) are a highly diverse and complex family of sulfated glycans responsible for regulation of a wide range of biological processes including growth factor signaling, enzyme activity and cell adhesion [34, 35]. HS proteoglycans (HSPGs) consist of HS chains linked to core proteins. They are located on the cell surface and extracellular matrix of mammalian cells where they exert vital roles in regulating cell behavior. HS side chains bind to a broad range of growth factors, cytokines and morphogens during cell proliferation and differentiation, co-operatively regulating ligand binding and signal transduction. In the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the anterior lateral ventricle (LV), one of two neurogenic zones in adult brain, HS are frequently associated with extracellular matrix structures named fractones. The fractal structure of the latter may facilitate contact with neural stem cells and their progeny [36].

Since HS synthesizing and modifying enzymes are crucial for development of a normal CC [37,38] we hypothesized that there might be some abnormality in the HS system in the brains of acallosal BTBR mice. Moreover, recent studies indicated that mice with conditional knockout of the HS synthesizing enzyme EXT1 (CaMKIICre; Extflox/flox [39]) display abnormal social behaviors. The aim of the current study was to describe HS system abnormalities by evaluation of the density of both HS and LAM associated with fractones in the SVZ of the LV in BTBR and B6 mice. Notably, the ventricles of BTBR mice are distorted, especially in the neurogenic zone of the LVs, in comparison to those of B6 [40], and most other mouse strains. Our analyses therefore included determination of differences in terms of the normal anterior-posterior distribution patterns of HS and LAM, as well as measurement of both LV area and the length of the LV SVZ in the neurogenic zone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Naïve, 10–17 week old male mice were used in this study. Inbred BTBR (n= 5) and B6 (n= 5) mice were bred at the University of Hawaii Laboratory Animal Services from stock originally obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were euthanized with an overdose of Avertin (2,2,2-Tribromoethanol, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO i.p. at approx. 330mg/kg) and their brains were removed from the cranial cavity. The brains were instantaneously frozen in isopentane cooled at −70°C and subsequently stored at −20°C. The animal experimental protocol followed NIH guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Hawaii, protocol # 09-786-2.

2.2. Analysis of N-sulfated heparan sulfate and laminin immunoreactivity

2.2.1. Immunocytochemistry

N-sulfated heparan sulfate- and laminin-immunopositive material was localized in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles of B6 and BTBR mice using single and dual immunofluorescence cytochemistry as described before (Mercier et. al., 2002 [33]). Briefly, the immunostaining was performed on serial 25 µm-thick brain sections (cut with CM1900 Leica cryostat) mounted on Poly-L-lysine (P4707; 1/5; Sigma-Aldrich) coated microscope slides. The serial coronal sections were stored at −20°C until the time of fixation (2 min) in cooled (−60°C) acetone. Then, the slices were incubated with the primary antibodies directed against N-sulfated heparan sulfates (1/500 antibody 10E4, Seikagaku-Cape Cod, East Falmouth) and laminin (1/1,000 L9393, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). Goat anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa-Fluor647, goat anti-mouse IgM conjugated to Alexa-Fluor488 (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen), and donkey anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 488 were used as secondary antibodies (all diluted at 1/400).

2.2.2. Image collection and analysis

The ventricle cross-sectional area and SVZ length were measured in all subjects on images (1392×1040 pixels) taken at 10× magnification using a digital DFC350FX Leica camera mounted on a Leica DMIL epifluorescence microscope set to visualize heparan sulfate immunoreactivity. The area of the LV was measured in pixels with the use of ImageJ (NIH) software by following the ependymal wall of the ventricle with the freehand selection tool. The length of the SVZ was measured using the freehand selection tool along the midline of the HS-positive fractone zone. The results were averaged across at least 3 brain slices (measurements taken bilaterally) per animal, from the same antero-posterior (AP) points (identified with the use of mouse brain atlas, [41]) in all animals (n=5/group). The AP points of interest were AP+1.0, +0.5, 0.0, −0.5 and −1.0, which cover the extent of the neurogenic zone of the LVs. To visualize the differences in LVs area we have performed additional staining of brain sections from the relevant AP levels with cresyl violet (Fig. 1).

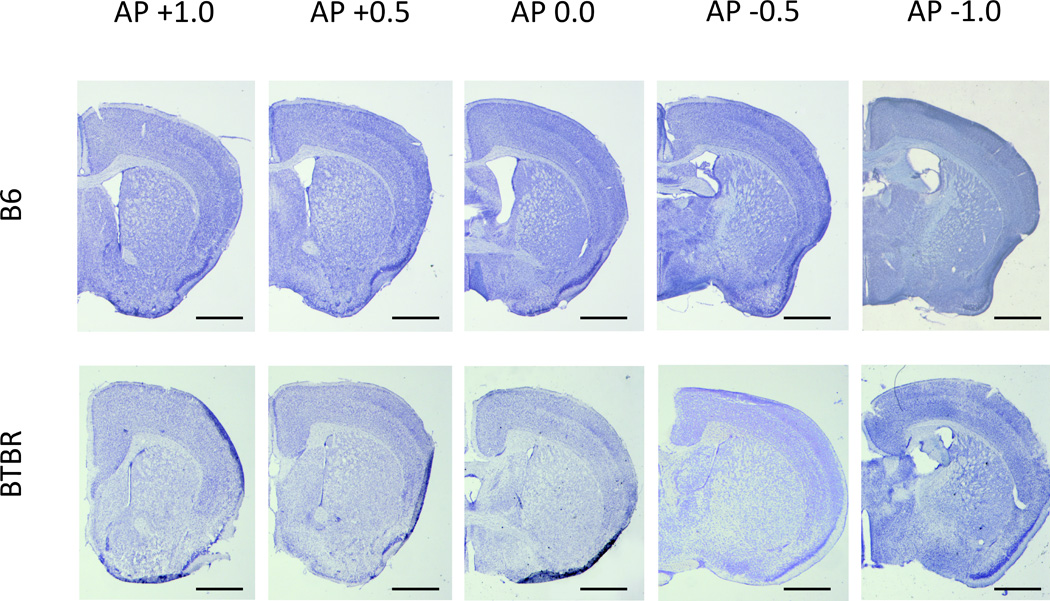

Fig. 1.

Representative cresyl violet stained sections of B6 and BTBR mouse brains at AP points +1.0 through −1.0. Scale bars are 1mm.

Area and intensity of laminin and heparan sulfate immunoreactivity in individual fractones were analyzed for two randomly selected subjects from each group (BTBR or B6) in images taken using a Zeiss Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope at 20× magnification. Each picture was composed of 3 channels (red (650nm) for LAM; green (505–620nm) for HS; and a blank blue channel). Partial images (unmodified, 2048×2048 pixels) were merged to show complete ventricles using Photoshop software (v 7.1; Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and subjected to channel separation (ImageJ software) after merging. The area of individual fractones was measured (in pixels) using the freehand selection tool (ImageJ) on the LAM channel. The intensity of LAM and HS immunostaining were measured on LAM and HS channels (both represented in grayscale, in an arbitrary 1–256 scale) respectively for each fractone. The parameters were scored separately for brain slices representing distinct AP points. All parameters were measured by a single, trained observer.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The normal distribution and homoscedasticity of data was tested (with the use of Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests) before analysis of variance was applied. For assessment of main effects of mouse strain and anterior-posterior distribution on LV area, SVZ length, and individual fractone area and LAM and HS immunoreactivity one-way ANOVA (strain serving as between-subject factor) with repeated measures for different AP points (within-subject factor) was performed with subsequent post-hoc Tukey’s range test for direct comparisons of values. Differences were considered significant if p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Ventricle area and SVZ length

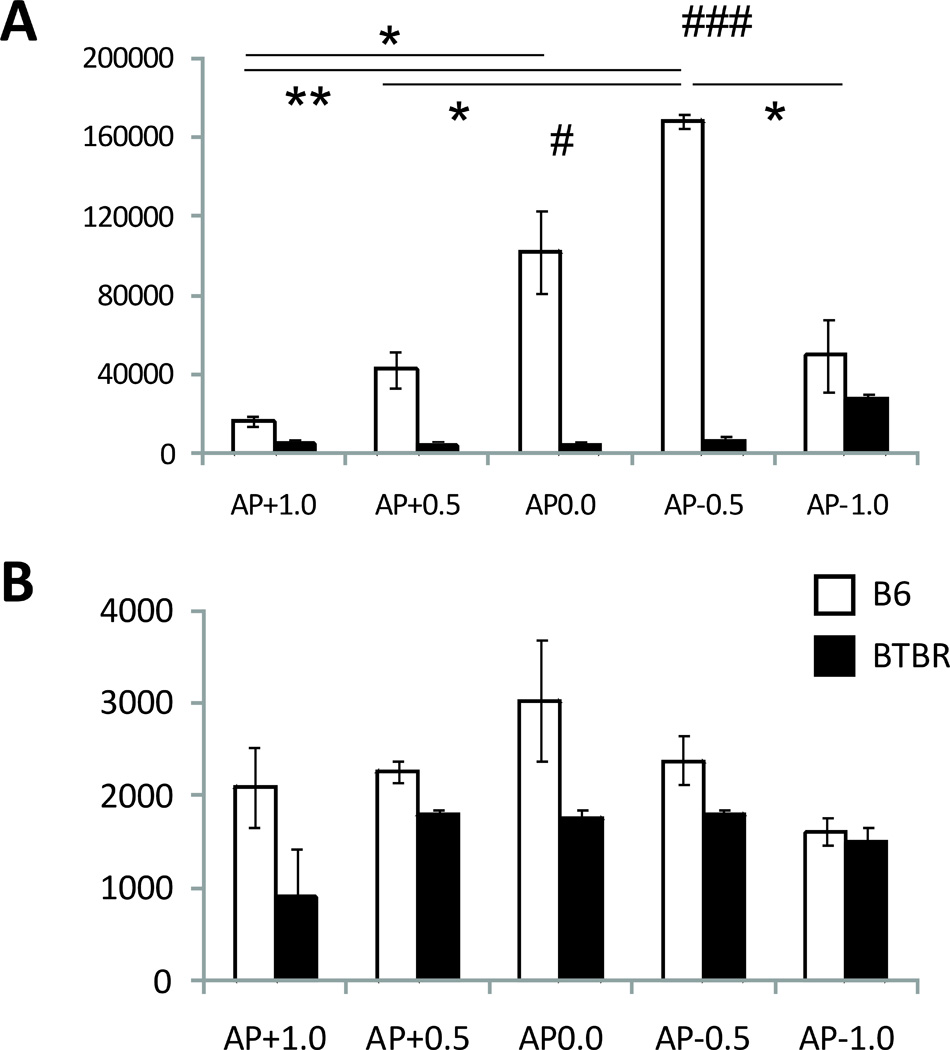

The quantification of differences in the size and shape (Figs. 1 and 2) of LV showed a strikingly reduced volume of LV cavity, and a reduction of about 40% in the length of the SVZ measured in the midline of HS-ir zone in BTBR vs. B6 mice. The BTBR LVs were smaller (F1,4=465,10 p<0.001) and this effect was also AP dependent (F4,12=6.62, p<0.01) with a significant interaction between strain × AP (F4,12=6.79, p<0.01). Post-hoc comparison showed that at AP points 0.0 and −0.5, the LV cavities of B6 were significantly larger than those of BTBR mice (Fig. 2A, p<0.05 and p<0.001 respectively, indicated with #’s). Within strain comparisons showed that the area of LVs significantly increased in B6 mice from AP+1.0 to 0.0 and −0.5 (Fig. 2A, p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively, indicated with *’s) and AP+0.5 to −0.5 (Fig. 2A, p<0.05, indicated with a *) and then dropped at AP-1.0, compared to AP-0.5 (p<0.05, indicated with a *), while in BTBR mice LV area remained constant, increasing (nonsignificantly) only at AP-1.0.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of B6/BTBR differences in lateral ventricles: A. area (in pixels, p<0.001 between strain differences indicated with ###, differences between AP points in B6 indicated with * and **, for p<0.05 and p<0.01 respectively); B. subventricular zone length (in pixels).

Although the effect of mouse strain on the length of the SVZ was significant (F1,4=9.92, p<0.05), the effect of AP and the interaction between the two factors was not. Therefore no detailed post-hoc analysis could be performed to establish if there were any AP-dependent differences in SVZ length between the two strains.

3.2. Size of individual fractones and densities of N-sulfated heparan sulfate (HS) and laminin (LAM)

The three parameters recorded using ImageJ (size of individual fractones, the intensity of laminin and heparan sulfate staining in fractones) as well as the HS/LAM ratio all yielded significant effects of mouse strain.

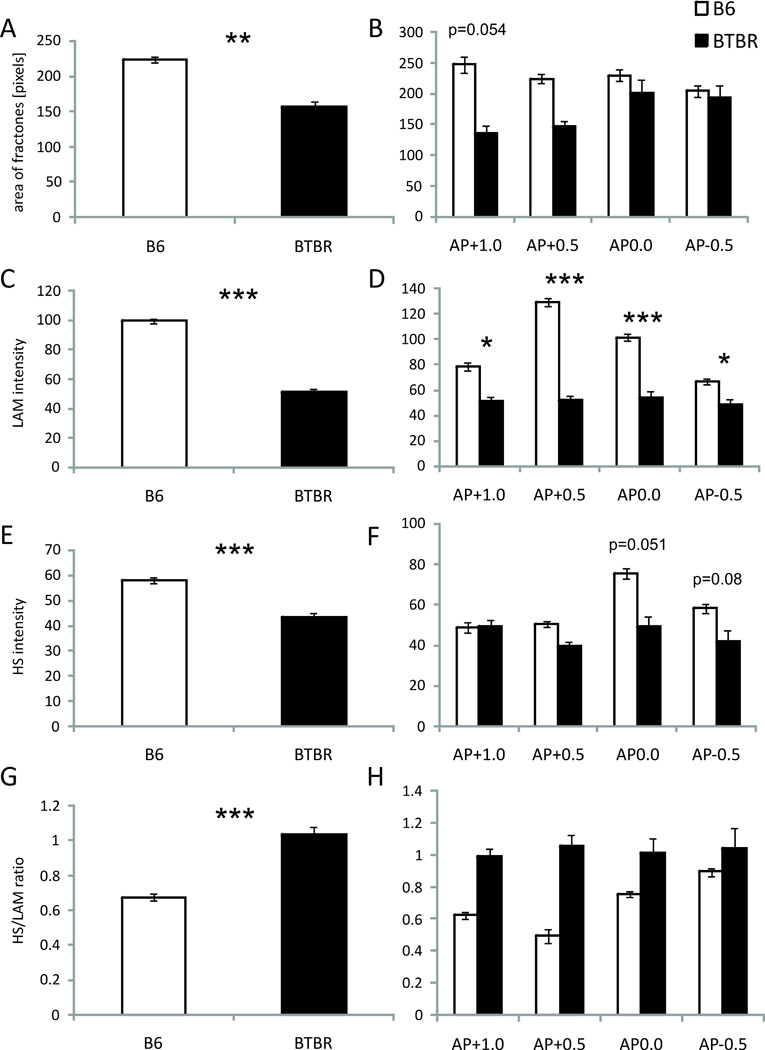

The total number of fractones identified and measured was n=1080 in 2 B6 brains, and n=345 in 2 BTBR brains. The mean area of fractones (measured in pixels, Fig. 3 A–B) was greater in B6 mice than in BTBR (F1,185=10.42, p<0.001, Fig. 3A, indicated with *’s). This effect was independent of AP (F3,555=1.29, p>0.05). The strain × AP interaction was also not significant (F3,555=0.94, p>0.05). Although at AP+1.0 and +0.5 individual fractones seem bigger in B6 mice (Fig. 3B), lack of an interaction of strain × AP did not allow for assessment of statistical significance of these differences.

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of individual fractones (B6 n=1083; BTBR n=345): A. total average size (in pixels, p<0.01 indicated with **); B. Size with respect to AP distribution (in pixels); C. total average intensity of LAM-ir (in grayscale 1–256, p<0.001 indicated with ***); D. Intensity of LAM-ir with respect to AP distribution (in grayscale 1–256, p<0.05 and p<0.001 indicated with * and ***); C. total average intensity of HS-ir (in grayscale 1–256, p<0.001 indicated with ***); D. Intensity of HS-ir with respect to AP distribution (in grayscale 1–256); E. total average ratio of HS to LAM-ir (p<0.001 indicated with ***); F. ratio of HS to LAM-ir with respect to AP distribution.

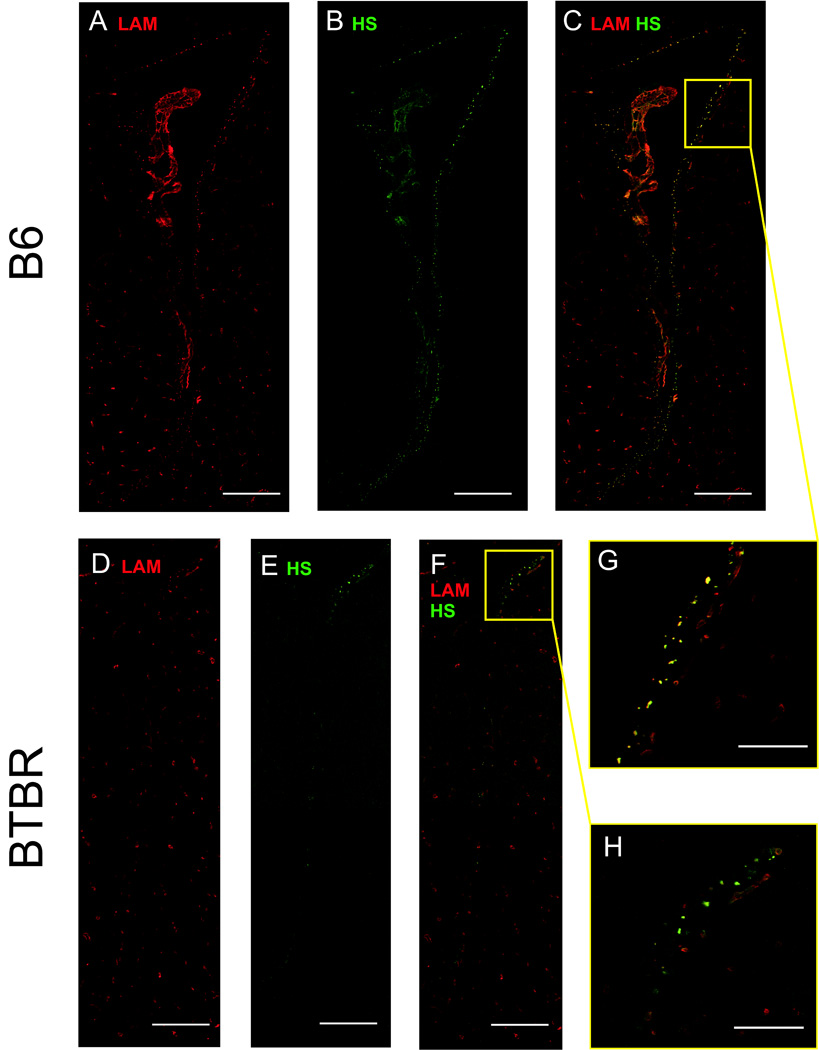

The intensity of laminin (LAM) staining (grayness on the 1–256 scale; Fig. 3 C–D) was also higher in B6 mice than in BTBR (F1,185=100.28, p<0.001, Fig 3A, indicated with *’s, also see Fig. 4 A and E). There was a significant effect of AP (F3,555=6.64, p<0.001). The interaction of strain × AP approached significance (F3,555=2.55, p<0.055) and the post-hoc analysis revealed that the fractones in B6 mouse brains contain more LAM than those found in BTBR mice throughout all AP points (p<0.05 to p<0.001, indicated with *’s). No differences in the intensity of fractone/laminin staining were observed in BTBR mice with regard to AP, but in B6 the highest content of LAM was observed at AP+0.5 (Fig. 3 D), followed by AP0.0, then +1.0 and −0.5, with significant differences between the AP+1.0 and AP+0.5 (p<0.001, not indicated), AP+1.0 and AP0.0 (p<0.001, not indicated), AP+0.5 and AP-0.5 (p<0.001, not indicated) and AP0.0 and AP-0.5 (p<0.001, not indicated).

Fig. 4.

B6 and BTBR lateral ventricles: A–C. B6 lateral ventricle at AP+0.0 as revealed by A. LAM-ir; B. HS-ir; C. both LAM and HS-ir; D–F. BTBR lateral ventricle at AP+0.0 as revealed by D. LAM-ir; E. HS-ir; F. both LAM and HS-ir; G. magnification of the B6 subventricular zone showing individual fractones; H. magnification of the BTBR subventricular zone showing individual fractones. Scale bar for A–C and D–F is 250µm; for G–H, 50 µm

Heparan sulfate (HS) immunoreactivity (-ir) in fractones was compared between strains and across AP points. The comparison yielded significant effect of strain (F1,185=20.13, p<0.001, Fig. 3 E, indicated with *’s, also to be seen on Fig. 4B and F), while the effect of AP approached significance (F3,555=2.50, p<0.059). The interaction of strain × AP did not reach significance (F3,555=2.01, p>0.05). Although lack of a strain × AP interaction precluded assessment of the significance of differences between B6 and BTBR mice at each AP point, there was no suggestion of an AP difference in BTBR mice, while in B6 the highest content of HS-ir occurred in slices from AP 0.0 (Fig. 3 F).

The comparison of average HS to LAM luminosity (HS/LAM ratio) within each investigated fractone revealed several significant differences. There was a significant effect of strain (F1,185=12.75, p<0.001), AP (F3,555=5.14, p<0.05) but no significant interaction of strain × AP (F3,555=0.32, p>0.05). A higher HS/LAM ratio was observed in BTBR mice than in the B6 strain (p<0.001, Fig. 3G, indicated with *’s). No AP-related differences were observed in BTBR mice. In B6 the highest ratio HS/LAM ratio was at AP-0.5.

4. Discussion

Present findings of reduced ventricle area, agenesis of the corpus callosum, and impaired development of the hippocampal commissure in BTBR mice were in accord with earlier reports [1,33,40,42], and also with studies demonstrating reduction or absence of the corpus callosum [43,44,45,46,47,48] and abnormalities in the ventricular system [12,13] in many individuals with ASD. Based on the area measurements made at 5 AP points (+1.0, +0.5, 0.0, −0.5 and −1.0), the volume of the lateral ventricles in BTBR was only about 1/20th of that of B6 mice. This was most evident at mid-AP levels (AP 0.0 and −0.5) of the frontal, neurogenic part of LVs, where the ventricles in most mouse strains are maximal in size; those of BTBR were essentially slits, compressing the choroid plexus. This is in line with data reported by Vidal and colleagues [12] showing that autistic children (aged 6–17) show most profound reduction in lateral ventricle volume in the frontal horns of the ventricles. This could be associated with early hypergrowth of frontal gray and white matter [49,50]. While in our study it was not possible to directly measure choroid plexus size, our observations suggest that the choroid plexus itself may be reduced or damaged in BTBR mice, providing a possible additional mechanism to be included in the BTBR spectrum of differences from other mouse strains in this area of the brain. Recent findings that the choroid plexus epithelium includes cells that may be able to function as neural progenitors, giving rise to neurons and glia [51] suggest a potential importance for this difference. While the length of the lateral ventricle SVZ in BTBR was only about 60% of its length in B6 mice, this measure was proportionately a great deal more normal than was the ventricle area measurement. However, as the SVZ of the lateral ventricles is one of two brain areas that continue to show neurogenesis in the adult brain [52], this reduction does suggest ongoing deficiencies related to neurogenesis in BTBR mice. Indeed, a recent study by Stephenson and colleagues [42] shows impaired neurogenesis along with reduced BDNF expression in the other neurogenic zone active throughout the adult life – the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Whether the adult neurogenesis in the SVZ of LVs in the BTBR mice is also impaired remains to be studied.

The constituents of the SVZ that were measured in the current study - laminin forming the basal lamina of the fractones and N-sulfated heparan sulfates found in association with these structures - were both significantly reduced in BTBR mice. HS appeared to be largely restricted to subpopulations of fractones, with little to no HS-ir observed on LAM-positive blood vessels (Fig. 4, close-ups D and H). Evidence that the reduction in heparan sulfate seen in BTBR mice may be related to additional brain abnormalities in these animals is provided by findings that blocking the biosynthesis of heparan sulfate produces abnormalities in the corpus callosum [37,38] have recently reported that mutant mice lacking heparan sulfotransferases Hs2st or Hs6st1 show a number of changes in the callosum, as well as in the optic chiasm. In particular Hs6st1−/− mice showed callosal agenesis with large knotted Probst-like axon bundles flanking but not crossing the midline, and some ectopic growth of septal axons ventral to the corpus callosum; while Hs2st−/− mice showed midline defects and Probst-like axon whorls but no septal axons ventral to the corpus callosum. A similar pattern of changes was seen in mice lacking the axon guidance molecule Slit2−/−, but not Slit1−/− mice. The interaction of Slit with their Robo receptors requires heparan sulfate [53], but Hs6st1 may also have Slit-independent functions [38]. Conway et. al. [38] suggest that the strong variation in heparan sulfate structure due to modifying enzymes such as Hs2st or Hs6st1 may provide a foundation for great diversity in HS functional effects.

The exact role of the association of HS with fractones is not yet fully understood. In particular, as HS-ir fractones have been reported in the mouse SVZ at embryonic days 9.5 to 12.5, declining thereafter until about PND17 when they are again visible [54], it is not clear that an association with fractones is necessary for the functioning of HS in perinatal development, although the early (before E12) occurrence of certain sulfated isoforms of HS (E10 HS) has been reported to be related to the peak of FGF-8 binding to FGFRs at that stage of development [55].

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans have enormous structural diversity and potentially corresponding functional diversity, modulating the activities of an array of intercellular signaling pathways including fibroblast growth factors and their receptors, and axon guidance factors such as Slit proteins and their Robo receptors [34,38]. As one example, deglycanation of heparan sulfate chains by heparatinase-1 sharply reduces the cell proliferative effects of FGF-2 [56]. Indirect evidence for the possible involvement of FGF-2 in an autism-relevant behavioral phenotype comes from a study on A12 (Atchley) inbred mice, selected for more than 50 generations on the basis of weight gain patterns, which show enhanced expression of FGF-2 in frontal cortex, along with reduced intra-strain social behavior and enhanced grooming stereotypy [57].

If HS similarly influences the binding of other members of the FGF family, its reduction in BTBR mice might be expected to have an even greater range of cell proliferation, guidance, and signaling effects. Ten members of the FGF family have been identified in the mammalian brain [58] with five of these (FGF-3, FGF-8, FGF-15, FGF-17 and FGF-18) expressed by a rostral patterning center; with FGF-8 and FGF-17 having a major role in the development of the cortex, while FGF-15 appears to serve as a negative regulator of their functioning [59]. At least one of them, FGF-17 has been reported to be associated with sociability. FGF-17-deficient mice showed reductions in social behaviors, and reduced c-Fos expression in frontal cortex following social interactions in a novel environment [60].

The link of altered expression of certain growth factors with autistic-like behaviors is further strengthened by studies using a prenatal immune challenge (Poly I:C; given on E9), such as has been hypothesized to model an environmental condition influencing autism [61,62] reported an enhancement of FGF-8 in treated fetuses two days after treatment followed by a precipitous drop later, as well as a significant reduction in dopamine levels. FGF-8 hypomorphic mice also show alterations of the epithalamus, including the habenula and the pineal gland [63] providing a potential link to the sleep disturbances that are very common in autism [64,65]. Reductions in oxytocin, which may be involved in social recognition and social reward [66] are also seen in some hypothalamic nuclei of FGF-8 hypomorphic mice [67].

A recent study by Wei and colleagues [68] showed that juvenile neurogenesis, which is apparently impaired in BTBR mice [42], is also necessary for development of normal social behaviors, adding to a view that sociality is strongly influenced by early modulation of growth and guidance factors in the brain. Reports that mice with conditional knockouts of the HS synthesizing enzyme EXT1 (CaMKII-Cre;Extflox/flox [39]) display abnormal social interactions further support the link between HS and formation of social behavioral patterns. Also, HS was shown to influence cognitive performance, an additional behavioral variable often altered in autism, as administration of HS to ventral pallidum was shown to promote formation of both short and long term memories in rats [69].

The consistency and specificity of autism-relevant behavior changes in BTBR mice (reviewed in Blanchard et. al., [70]) have made these mice a focus for the search for endophenotypes for autism. The present findings that BTBR mice show reductions in fractone-associated HS, with multiple potential downstream effects on brain and behavior, suggest one intriguing area for analysis. To name a few, further studies are required to assess whether similar HS reduction occurs at early developmental stages and to what extent it could be linked with the agenesis of CC observed in BTBR mice. Also since juvenile neurogenesis is required for development of social skills (Wei et al., 2011 [68]) the neurogenic activity of LV SVZ should be studied at different post natal stages, with emphasis on the role of HS and the possible role of compression of choroid plexus in the generation of new neurons.

Highlights.

BTBR T+tf/J mice show reduced lateral ventricle area, and length,

They have substantially less fractone-associated heparan sulfate (HS)

HS binds an array of growth factors and may modulate their expression

Thus HS reductions may alter brain structural and functional development

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Frederic Mercier, who provided information on extracellular matrix factors, and instructed BP and RB in immunohistochemistry. We also thank the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy: Imaging and Histology Core facility, John A. Burns School of Medicine. Supported by NIH MH081845 to RJB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors’ contributions

CB and RB conceptualized the study and helped to draft the manuscript. KM evaluated fractone-associated HS-ir and LAM-ir, and measured LV area, SVZ length, and size of individual fractones, performed statistical analyses, and took primary responsibility for the manuscript. BP and RP prepared brains for analysis and performed immunohistochemistry. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Wahlsten D, Metten P, Crabbe JC. Survey of 21 inbred mouse strains in two laboratories reveals that BTBR T/+ tf/tf has severely reduced hippocampal commissure and absent corpus callosum. Brain Res. 2003;971(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: an update. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maenner MJ, Durkin MS. Trends in the prevalence of autism on the basis of special education data. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1018–1025. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maughan B, Iervolino AC, Collishaw S. Time trends in child and adolescent mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:381–385. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000172055.25284.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter M. Autism research: lessons from the past and prospects for the future. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35:241–257. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-2003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Happé F, Ronald A. The 'fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):287–304. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betancur C. Etiological heterogeneity in autism spectrum disorders: More than 100 genetic and genomic disorders and still counting. Brain Res. 2011;1380:42–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geschwind DH. Genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(9):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufour-Rainfray D, Vourc'h P, Tourlet S, Guilloteau D, Chalon S, Andres CR. Fetal exposure to teratogens: evidence of genes involved in autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(5):1254–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landrigan PJ. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(2):219–225. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328336eb9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courchesne E, Campbell K, Solso S. Brain growth across the life span in autism: age-specific changes in anatomical pathology. Brain Res. 2011;1380:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidal CN, Nicolson R, Boire JY, Barra V, DeVito TJ, Hayashi KM, Geaga JA, Drost DJ, Williamson PC, Rajakumar N, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Three-dimensional mapping of the lateral ventricles in autism. Psychiatry Res. 2008;163(2):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wegiel J, Kuchna I, Nowicki K, Imaki H, Wegiel J, Marchi E, et al. The neuropathology of autism: defects of neurogenesis and neuronal migration, and dysplastic changes. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119(6):755–770. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition, DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baird G, Cass H, Slonims V. Diagnosis of autism. BMJ. 2003;327:488–493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B. Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder. Nature Rev Genet. 2001;2:943–955. doi: 10.1038/35103559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolivar VJ, Walters SR, Phoenix JL. Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarlane HG, Kusek GK, Yang M, Phoenix JL, Bolivar VJ, Crawley JN. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(2):152–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176(1):4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Defensor EB, Pearson BL, Pobbe RL, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. A novel social proximity test suggests patterns of social avoidance and gaze aversion-like behavior in BTBR T+ tf/J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217(2):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scattoni ML, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in adult BTBR T+tf/J mice during three types of social encounters. Genes Brain Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00623.x. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Clarke AM, Crawley JN. Postnatal lesion evidence against a primary role for the corpus callosum in mouse sociability. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(8):1663–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang M, Scattoni ML, Zhodzishsky V, Chen T, Caldwell H, Young WS, et al. Social Approach Behaviors are Similar on Conventional Versus Reverse Lighting Cycles, and in Replications Across Cohorts, in BTBR T+ tf/J, B6, and Vasopressin Receptor 1B Mutant Mice. Front Behav Neurosci. 2007a;1:1. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08/001.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang M, Zhodzishsky V, Crawley JN. Social deficits in BTBR T+tf/J mice are unchanged by cross-fostering with B6 mothers. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007b;25(8):515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Poe MD, Nonneman RJ, Young NB, Koller BH, et al. Development of a mouse test for repetitive, restricted behaviors: relevance to autism. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188(1):178–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson BL, Pobbe RLH, Defensor EB, Oasay L, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Motor and cognitive stereotypies in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10(2):228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scattoni ML, Gandhy SU, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scattoni ML, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in adult BTBR T+tf/J mice during three types of social encounters. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10(1):44–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolivar VJ. Intrasession and intersession habituation in mice: from inbred strain variability to linkage analysis. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92(2):206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benno R, Smirnova Y, Vera S, Liggett A, Schanz N. Exaggerated responses to stress in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse: an unusual behavioral phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197(2):462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pobbe RL, Defensor EB, Pearson BL, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. General and social anxiety in the BTBR T+ tf/J mouse strain. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216(1):446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman JL, Yang M, Turner SM, Katz AM, Bell DB, Koenig JI, et al. Low stress reactivity and neuroendocrine factors in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. Neuroscience. 2010;171(4):1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusek GK, Wahlsten D, Herron BJ, Bolivar VJ, Flaherty L. Localization of two new X-linked quantitative trait loci controlling corpus callosum size in the mouse. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6(4):359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turnbull J, Powell A, Guimond S. Heparan sulfate: decoding a dynamic multifunctional cell regulator. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01897-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishop JR, Stanford KI, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans and triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(3):307–313. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282feec2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerever A, Schnack J, Vellinga D, Ichikawa N, Moon C, Arikawa-Hirasawa E, Efird JT, et al. Novel extracellular matrix structures in the neural stem cell niche capture the neurogenic factor fibroblast growth factor 2 from the extracellular milieu. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2146–2157. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inatani M, Irie F, Plump AS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Yamaguchi Y. Mammalian brain morphogenesis and midline axon guidance require heparan sulfate. Science. 2003;302(5647):1044–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.1090497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conway CD, Howe KM, Nettleton NK, Price DJ, Mason JO, Pratt T. Heparan sulfate sugar modifications mediate the functions of slits and other factors needed for mouse forebrain commissure development. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):1955–1970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2579-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irie F, Yamaguchi Y. Deficiency of heparan sulfate in excitatory neurons causes autism-like behavior in mice. Abstract at the Third International Multiple Hereditary Exostoses Research Conference; 10/29/2009–11/01/2009; Boston. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mercier F, Cho Kwon Y, Kodama R. Meningeal/vascular alterations and loss of extracellular matrix in the neurogenic zone of adult BTBR T+ tf/J mice, animal model for autism. Neurosci Lett. 2011;498(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Second Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephenson DT, O'Neill SM, Narayan S, Tiwari A, Arnold E, Samaroo HD, Du F, Ring RH, Campbell B, Pletcher M, Vaidya VA, Morton D. Histopathologic characterization of the BTBR mouse model of autistic-like behavior reveals selective changes in neurodevelopmental proteins and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Mol Autism. 2011;2(1):7. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Boudos R, DuBray MB, Oakes TR, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum in Autism. NeuroImage. 2007;34(1):61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cody H, Pelphrey K, Piven J. Structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2002;20(3–5):421–438. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egaas B, Courchesne E, Saitoh O. Reduced size of the corpus callosum in autism. Acrh Neurol. 1995;52:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller TA, Kana RK, Just MA. A developmental study of the structural integrity of white matter in autism. NeuroReport. 2007;18(1):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000239965.21685.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanfield AC, McIntosh AM, Spencer MD, Philip R, Gaur S, Lawrie SM. Towards a neuroanatomy of autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;23:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verhoeven JS, De Cock P, Lagae L, Sunaert S. Neuroimaging of Autism. Neuroradiology. 2010;52(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0583-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carper RA, Courchesne E. Localized enlargement of the frontal cortex in early autism. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carper RA, Moses P, Tigue ZD, Courchesne E. Cerebral lobes in autism: early hyperplasia and abnormal age effects. NeuroImage. 2002;12:1038–1051. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Itokazu Y, Kitada M, Dezawa M, Mizoguchi A, Matsumoto N, Shimizu A, et al. Choroid plexus ependymal cells host neural progenitor cells in the rat. Glia. 2006;53(1):32–42. doi: 10.1002/glia.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mudò G, Bonomo A, Di Liberto V, Frinchi M, Fuxe K, Belluardo N. The FGF-2/FGFRs neurotrophic system promotes neurogenesis in the adult brain. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(8):995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0207-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hohenester E. Structural insight into Slit-Robo signalling. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2008;36(Pt 2):251–256. doi: 10.1042/BST0360251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douet V, Mercier F, Arikawa-Hirasawa E. The novel extracellular matrix structures fractones are associated with neurogenesis during development. Juntendo University School of Medicine. 2008;54(3):413. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford-Perriss M, Guimond SE, Greferath U, Kita M, Grobe K, Habuchi H, Kimata K, Esko JD, Murphy M, Turnbull JE. Variant heparan sulfates synthesized in developing mouse brain differentially regulate FGF signaling. Glycobiology. 2002;12(11):721–727. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Douet V, Mercier F. Control of cell division in the adult brain by heparan sulfates in fractones and vascular basement membranes. Nature Proceedings. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jarosik J, Legutko B, Werner S, Unsicker K, von Bohlen Und Halback O. Roles of exogenous and endogenous FGF-2 in animal models of depression. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29(3):153–165. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2011-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reuss B, von Bohlen und Halbach O. Fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in the central nervous system. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;313(2):139–157. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borello U, Cobos I, Long JE, McWhirter JR, Murre C, Rubenstein JL. FGF15 promotes neurogenesis and opposes FGF8 function during neocortical development. Neural Dev. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scearce-Levie K, Roberson ED, Gerstein H, Cholfin JA, Mandiyan VS, Shah NM, et al. Abnormal social behaviors in mice lacking Fgf17. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(3):344–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McAlonan GM, Li Q, Cheung C. The timing and specificity of prenatal immune risk factors for autism modeled in the mouse and relevance to schizophrenia. Neurosignals. 2010;18(2):129–139. doi: 10.1159/000321080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer U, Engler A, Weber L, Schedlowski M, Feldon J. Preliminary evidence for a modulation of fetal dopaminergic development by maternal immune activation during pregnancy. Neuroscience. 2008;154(2):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez-Ferre A, Martinez S. The development of the thalamic motor learning area is regulated by Fgf8 expression. J Neurosci. 2009;29(42):13389–13400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2625-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doyen C, Mighiu D, Kaye K, Colineaux C, Beaumanoir C, Mouraeff Y, et al. Melatonin in children with autistic spectrum disorders: recent and practical data. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(5):231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Souders MC, Mason TB, Valladares O, Bucan M, Levy SE, Mandell DS, et al. Sleep behaviors and sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorders. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1566–1578. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Insel TR. The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuron. 2010;65(6):768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brooks LR, Chung WC, Tsai PS. Abnormal hypothalamic oxytocin system in fibroblast growth factor 8-deficient mice. Endocrine. 2010;38(2):174–180. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9366-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wei L, Meaney MJ, Duman RS, Kaffman A. Affiliative behavior requires juvenile, but not adult neurogenesis. J.Neurosci. 2011;31(40):14335–14345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1333-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Souza Silva MA, Jezek K, Weth K, Müller HW, Huston JP, Brandao ML, Hasenöhrl RU. Facilitation of learning and modulation of frontal cortex acetylcholine by ventral pallidal injection of heparin glycosaminoglycan. Neuroscience. 2002;113:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blanchard DC, Defensor EB, Meyza KZ, Pobbe RLH, Pearson BL, Bolivar VJ, Blanchard RJ. BTBR T+tf/J mice: autism-relevant behaviors and reduced fractone-associated heparan sulfate. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.06.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]