Abstract

Factors that enhance the intrinsic growth potential of adult neurons are key players in the successful repair and regeneration of neurons following injury. Injury-induced activation of transcription factors has a central role in this process because they regulate expression of regeneration-associated genes. Sox11 is a developmentally expressed transcription factor that is significantly induced in adult neurons in response to injury. Its function in injured neurons is however undefined. Here, we report studies that use herpes simplex virus (HSV)-vector-mediated expression of Sox11 in adult sensory neurons to assess the effect of Sox11 overexpression on neuron regeneration. Cultured mouse dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons transfected with HSV-Sox11 exhibited increased neurite elongation and branching relative to naïve and HSV-vector control treated neurons. Neurons from mice injected in foot skin with HSV-Sox11 exhibited accelerated regeneration of crushed saphenous nerves as indicated by faster regrowth of axons and nerve fibers to the skin, increased myelin thickness and faster return of nerve and skin sensitivity. Downstream targets of HSV-Sox11 were examined by analyzing changes in gene expression of known regeneration-associated genes. This analysis in combination with mutational and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays indicates that the ability of Sox11 to accelerate in vivo nerve regeneration is dependent on its transcriptional activation of the regeneration-associated gene, small proline rich protein 1a (Sprr1a). This finding reveals a new functional linkage between Sox11 and Sprr1a in adult peripheral neuron regeneration.

Keywords: transcriptional control, sry, skin delivery, saphenous nerve injury, HSV vector

INTRODUCTION

The intrinsic growth potential of damaged neurons, reflected in part by activation of transcriptional complexes, is recognized as a core component of successful nerve regeneration (Snider, et al., 2002, Sun and He, 2010). Injury-induced expression of transcription factors is critically important since they regulate expression of several genes that profoundly impact the survival and growth potential of injured neurons (Abe and Cavalli, 2008, Jenkins and Hunt, 1991, Lee, et al., 2004, Tsujino, et al., 2000). Of particular interest to our laboratory has been the injury-induced expression of Sox11, a member of the developmentally essential Sry-related HMG box containing transcription factor gene family (Hargrave, et al., 1997). Sox proteins have been shown to function as major regulators of cell fate, survival and differentiation across all developing organ systems (Bhattaram, et al., 2010, Lefebvre, et al., 2007). Their dysfunction likely underlies several genetic diseases, tumorigenesis and cancer progression (Penzo-Mendez, 2010, Wegner, 2009). Sox factors bind the minor groove of DNA via a 79 amino acid high mobility group (HMG) DNA binding domain that interacts in many cases with AT rich sites having a degenerate motif of 5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G-3′ (Badis, et al., 2009, Harley, et al., 1994). Sox regulation of gene transcription also involves activation of a carboxyterminal transactivation domain (TAD) that is thought to facilitate interaction with other coactivators and components of the transcriptional complex (Schepers, et al., 2002, Wiebe, et al., 2003).

Gene knockout studies have shown Sox11 to be essential for embryonic development with widespread affects across cardiac, skeletal, visceral and neuronal systems (Sock, et al., 2004). In developing chick spinal cord neurons Sox11 functions with the closely related Sox4 protein to regulate expression of pan-neuronal genes such as Tuj1 and NF1 (Bergsland, et al., 2006). In developing mice Sox11 supports proliferation and survival of spinal cord, sympathetic and sensory neurons (Bhattaram, et al., 2010, Lin, et al., 2011, Potzner, et al., 2010). Although significantly downregulated at late stages (E18-E20) in developing sensory neurons, Sox11 is significantly increased in response to adult nerve injury, suggesting a role in transcriptional regulation of survival and regeneration-associated genes in the adult (Tanabe, et al., 2003). Support for this role is provided by in vitro and in vivo studies that showed RNAi-mediated targeted knockdown in Sox11 reduces sensory neuron survival and growth of myelinated and unmyelinated axons (Jankowski, et al., 2006, Jankowski, et al., 2009).

Although reduction of Sox11 negatively impacts regeneration, its role following nerve injury, mechanism of action and possible use in promoting adult neuron regeneration remain undefined. To address these issues and to begin to identify transcriptional targets of Sox11 in adult neurons we performed gain of function studies in which cutaneous injection of neurotropic herpes simplex virus (HSV) vectors was used to drive Sox11 expression in peripheral dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons. HSV-mediated Sox11 expression was found to increase neurite growth in cultured DRG neurons and accelerate axon regeneration and functional recovery of peripheral nerves in vivo. In addition, HSV-Sox11 treatment caused a significant increase in the regeneration-associated gene small proline-rich repeat protein 1A (Sprr1a), a protein previously shown to significantly stimulate neurite growth in vitro (Bonilla, et al., 2002). Importantly, luciferase reporter assays, site-directed mutagenesis and chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) assays show a direct regulation of Sprr1a transcription by Sox11.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experiments were conducted using adult (6-8 weeks) male Swiss-Webster (SW) mice (Hilltop Lab Animals, Scottdale, PA) and C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) mice. Animals were housed in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility in a temperature and humidity controlled room on a 12h light/12h dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum. Procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out in accordance with the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Sox11 plasmids and HSV vectors

mSox11 was subcloned from IMAGE clone #63299841 into pCMV-IRES-EGFP (BD Biosciences Clontech, Mountainview, CA) and from this plasmid a CMV-Sox11 fragment containing 166 bp of the Sox11 5’ UTR and 1093 bp of the 3’ UTR was used for constructing HSV-Sox11. Sox11-HA was made by PCR cloning a hemaglutinin (HA) tag in frame using at the 3’ end of the Sox11 cDNA. Sox11-HA was only used in some in vitro experiments since we were unable to identify HA immunolabeling in vivo due to high background. Dr. A. Rizzino (University of Nebraska Medical Center) generously provided plasmids containing an amino FLAG-tagged Sox11 (Sox11F) and a mutant lacking the transactivation domain (Sox-11FΔTAD; described in (Wiebe, et al., 2003)).

HSV constructs containing the hCMV IE promoter were generated following procedures described in (Mata, et al., 2002). The vectors used provide transient human CMV-driven expression of inserted sequences to avoid possible effects of long-term expression of the Sox11 gene. The control vector (HSV-enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) contains two copies of a hCMVp:EGFP cassette targeted to the deleted (Δ) infected cell protein 4 (ICP4) loci of the backbone vector (vHG) (see Fig. 1). Inserts containing the CMV promoter driving Sox11 (hCMV:Sox11) or hemaglutinin (HA)-tagged Sox11 (hCMV:Sox11-HA) were also targeted to the ICP4 loci. Propagation and purification of high titer stocks of HSV-Sox11 and Sox11-HA vectors followed previously described protocols (Goins, et al., 2008, Goins, et al., 2002).

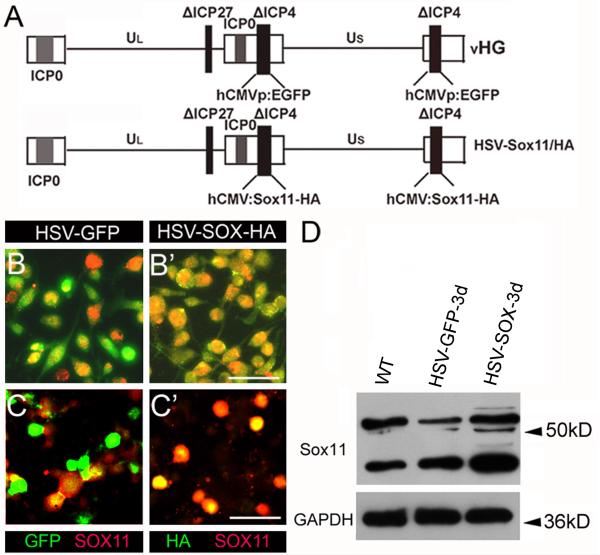

Figure 1. HSV mediated gene transfer of Sox11 in vitro.

A. Genomic structure of HSV vectors used for GFP and Sox11 gene transfer. The control vHG vector contains deletions (Δ) of ICP4 and ICP27 and a hCMVp:eGFP cassette. The hCMV:Sox11 or hCMV:Sox11-HA cassettes were also targeted to the two ICP4 loci. B-C’. GFP fluorescence and antibodies to Sox11 (red) or HA (green) were used to detect HSV vector expression in Neuro2A cells (B-B’) and DRG neurons (C-C’) at 24h after vector addition. Note increase in Sox11 labeling intensity in HSV-Sox11-HA treated cultures (red labeling in B’ and C’) relative to HSV-GFP (B and C) treated cultures. D. Immunoblots assessed Sox11 protein at 3d after HSV-Sox11-HA infection in cultured DRG neurons. Bands just above 50 kD identify Sox11 since they align with bands present in Neuro2A cells transfected with CMV-Sox11 plasmids (not shown). The identity of the major lower band is unknown at this time. Also note that HSV-driven expression of GFP in cultured neurons causes a reduction in Sox11 protein level. This effect was not seen in vivo (see Fig. 3C) and may reflect the high level of GFP protein. Scale bars=50μm. GAPDH used as loading control was unchanged.

In vitro infection and neurite outgrowth assays

Neuro2A cells or primary DRG neurons cultured in chamber slides coated with laminin and polylysine (20ug/ml each) were incubated for 2h with HSV vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 after which fresh medium was added. At 28h and 48h post plating DRG cultures were fixed and immunolabeled with antibodies against activated caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or neuron specific β-tubulin III. Digital images were acquired using a Leica DM4000B microscope and manipulated for brightness and contrast using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). The percentage of neurons bearing neurites and length of β-tubulin III immunoreactive processes was determined using NIH Image J software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD). Greater than 200 randomly selected neurons were analyzed per condition and experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

siRNA transfection and explant analysis

The efficacy of Sprr1a siRNAs was established using 4d-old cultures of DRG neurons transfected with 50nM non-targeting siRNA or a Smartpool of Sprr1a targeting siRNAs (Dharmacon; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO) using Metafectine reagent (Biontex, Martinsried, Germany) following the general protocol described in (Schmutzler, et al., 2011). Cells were incubated 48h with siRNAs, total protein was isolated and western blotting performed using anti-Sprr1a (1:1000, a kind gift from Dr. Stephen Strittmatter, Yale University, New Haven, CT)(Bonilla, et al., 2002)). DRG explant cultures were established as described in (Tonge, et al., 1997) with modifications. Briefly, DRGs of lumbar and thoracic levels were placed on 25mm coverslips coated with 20μg/ml poly-L-lysine, laminin and 30 μl extracellular matrix (ECM) gel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Explants were cultured 24h in F12 medium with 10% FBS and treated with HSV vectors at MOI = 1 for 2h after which fresh medium was added. At 4d post plating explant cultures were treated for 48h with 100 mM non-targeting or Sprr1a siRNAs delivered using Metafectine. Explants were fixed in parallel using 4% PFA, immunolabeled with anti-Tuj1 antibody and the mean length of the 10 longest axons determined. To determine the overall labeling intensity of neurites, electronically captured images were analyzed using the threshold function in Image J software. Data were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA with P<0.05.

HSV inoculation and surgery

Surgical procedures were performed under 2-3% isoflurane anesthesia (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) except where noted. Anesthetized mice were inoculated subcutaneously in the dorsal medial region of the right hind paw with 20μl of HSV-Sox11 or HSV-GFP virus at a concentration of 8×108 plaque-forming units/ml. A crush injury of the saphenous nerve was made 3d after inoculation at mid-thigh level using a small forceps (Dumont #5, Fine Science Tools) that was applied to the nerve twice for 5 sec durations (Bridge, et al., 1994). The injury site was marked with a small amount of the hydrophobic cyanine dye DiI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) applied to the juxtaposed muscle at the crush site. The saphenous nerve was used because it is well characterized anatomically, it only innervates the skin and its innervation field facilitates behavioral testing. Crush injuries were used because they damage nerve fibers but leave the surrounding connective sheath intact, which reduces variability in recovery (Bridge, et al., 1994). Behavioral, anatomical or molecular analyses were performed at 3, 5, 12, and 25 days after injury. Naïve mice did not undergo surgery.

Histomorphology of nerve fibers

Morphological analysis of axon profiles was performed on nerves isolated from animals at 5, 12, and 25 days post crush injury (DPCI). Nerve segments (3mm) were collected following in situ fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min and post-fixed in the same fixative at 4°C overnight. Nerves were stained with 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1M PBS and embedded in Epon 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences) as previously described (Jankowski, et al., 2009). Semi-thin sections were collected, stained with 1% toluidine blue and high-resolution digital images acquired using a Leica DM4000B microscope. Images were manipulated for brightness and contrast using Photoshop 7.0. Counts of myelinated axons from nerve profiles from 4 animals per group were made at each time point. Nerve profiles were also analyzed using the threshold grey-scale level function of NIH Image J software to determine the total myelin sheath area and to estimate axonal diameter and myelin sheath thickness. From these values the g-ratio was calculated as the ratio of axonal diameter /diameter of the axon plus myelin sheath.

Immunocytochemistry

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS. The lumbar L2-L3 DRG, peripheral nerve stump and skin overlying the saphenous nerve innervation field was post-fixed for 2h, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in 0.1M PBS, embedded in Tissue-Tek and sectioned at 20um on a cryostat. Sections were incubated with antibodies to mouse anti-β-tubulin type III (1:1000, Chemicon), rabbit-anti-GAP-43 (1:2500, Abcam), mouse-anti-N52 (1:1500, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), rabbit-anti-PGP9.5 (1:4000, Chemicon), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1:500, Cell Signaling), rabbit-anti-Sox11 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) or rabbit anti-Sprr1a (Bonilla, et al., 2002). Antibody binding was visualized using species-appropriate antibodies conjugated to Cy2 or Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1h at room temperature. Sox11 staining used an antigen retrieval method in which sections were heated in 0.1 M Tris-HCl to 80-90°C (pH9.5) for 10 min. Photomicrographic images were obtained using a Leica fluorescent microscope with attached CCD camera (Wetzlar, Germany) and manipulated for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop software.

To assess skin innervation sections overlying the saphenous nerve field were immunolabeled with the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 to visualize nerve terminals. The length of labeled processes relative to the length of epidermis was determined using NIH Image J software (Scion, Frederick, MD). Images were analyzed from at least ten nonconsecutive sections of the skin using 4 animals per group at each time point analyzed.

Behavioral withdrawal response assays

Functional axon regeneration was evaluated using a nerve pinch test performed in lightly anesthetized animals at 5 and 12 DPCI as described in (Rich, et al., 1984, Seijffers, et al., 2007). Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane, the saphenous nerve was exposed and after establishing a light plane of anesthesia (1% isoflurane), the nerve was lightly pinched with fine forceps, moving distal to proximal toward the injury site. The point of functional regeneration was determined by measuring the distance from the marked injury site to the most distal point of the nerve where a pinch produced a withdrawal response (Rich, et al., 1984). Functional recovery was also evaluated using a skin pinch test at 25 DPCI. Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane for 5 min, switched to 1% isoflurane and the skin overlying the saphenous innervation field pinched with forceps. Positive functional responses were recorded if pinch produced a withdrawal reflex.

Reverse transcriptase PCR

Cultured cells or whole DRG were lysed in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and total mRNA and protein isolated following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA first strand cDNA synthesis was performed using superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time SYBR green labeled PCR reactions were run on an ABI Prism 7000 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and normalized against Gapdh. Primer sequences used were: Sox11 5′-ACCCGGACTGGTGCAAGAC-3′; 5′-CGACTGCTCCATGATCTTCCT-3′, Sprr1a 5′-GCTGTCTATCCTGCTTATGAGTC-3′; 5′-CTTTGGGCAATGTTAAGAGGC-3′ and Gapdh 5′-ATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATTTGA-3′; 5′-ATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTT-3′.

Western immunoblotting

Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay kit (Fisher Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Protein (30 μg) was dissolved in 0.1% SDS, boiled in 5X SDS loading buffer for 10 min, separated on a 10-15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, blocked in 5% skim milk and incubated in primary antibody at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies used were mouse-anti-β-tubulin III (1:1500, Chemicon), rabbit-anti-Sox11 (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotech), rabbit-anti-HA (1:5000, Abcam), rabbit anti-Sprr1a (1:3000; Bonilla et al., 2002) and rabbit-anti-Gapdh (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotech). Horseradish peroxidase coupled secondary antibodies were used for amplification and binding visualized using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Fisher Thermo Scientific).

Mutagenesis and luciferase assays

The TOPO-TA PCR cloning system (Invitrogen) was used to construct pGL-422. A 1626 bp fragment containing 422 bp of the proximal promoter and 1204 bp of exon 1/intron 1 of Sprr1a was amplified using C57BLK6 mouse genomic liver DNA using primers 5′-GCTTCACTAAGAGATAGCAAGCATCC-3′ and 5′-GGTTAGATAGCACTTGGTCCTGG-3′. The insert was sequenced by the Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories at the University of Pittsburgh to confirm identity and subcloned into pGL2-Basic (Promega, Madison, WI) at the SacI/XhoI sites in the multiple cloning region. Plasmids with mutated Sox binding sites (pGLm108, pGLm169 and pGLm1150) were generated using the Quik-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Primers were designed using PrimerX (http://www.bioinformatics.org/primerx/links.html): mut-108 (5′-CTTATTTTTTTACTATGAAAAACTGTTCCCCGCCAACTCTATTACAGAGTTGATGTGGG-3′; 5′-CCCACATCAACTCTGTAATAGAGTTGGCGGGGAACAGTTTTTCATAGTAAAAAAATAAG-3′), mut-169 (5′- TGCCTACAGTTAGTGAACAGTAGCACGCGTTGCTTAAATTATAGCACATTTT-3; 5′-AAAATGTGCTATAATTTAAGCAACGCGTGCTACTGTTCACTAACTGTAGGCA-3′) and mut-1150 (5′-GTTGAGGTTACCTTCTCTTTCCCCGAATCACTAAATTGTCTTTTC-3′; 5′- GAAAAGACAATTTAGTGATTCGGGGAAAGAGAAGGTAACCTCAAC-3′). Clones with mutated residues were verified by DNA sequencing. Transfection of plasmids in Neuro-2A cells grown according to ATCC guidelines was done in 12-well plates with 1 × 105 cells per well using Mirus TransIT-Neural transfection reagent. Cells were harvested 24h post transfection in Promega Passive Lysis Buffer, lysates were centrifuged to remove insoluble material and the supernatant moved to a clean tube. Luciferase activity was measured using a Turner 20/20n automatic luminometer with dual injectors following the Promega Dual-Luciferase Assay protocol. Reporter expression was normalized to co-transfected Renilla luciferase activity and the normalized value (RLUpGL2/RLUpRL-TK) used for statistical analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

ChIP assays were performed using the Upstate Biotechnology (Waltham, MA) protocol following the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Neuro2A cells (4 × 107) transiently transfected with pFLAG-Sox11 were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C after which glycine was added to 125 mM to quench. Cells were lysed in buffer containing 1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Chromatin was sheared by sonication and cell extracts pre-cleared with protein G-agarose beads preadsorbed with salmon sperm DNA. Extracts were diluted in IP buffer and incubated with 5 μg anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma). Immunocomplexes were collected on preadsorbed protein G-agarose beads, washed, eluted and cross-linked complexes reversed by heating at 65°C overnight. No antibody and non-immune mouse IgG (Sigma) were used as controls. DNA from immunoprecipitates was purified using spin columns and incubated with PCR primers designed to amplify regions specific to the predicted Sox binding sites in Sprr1a intron 1 (5′-AGAGCATCTGGGCCAAGTGTGTTT-3 and 5-TGTTCACTAACTGTAGGCAGCACC-3′; 5′-GGTGCTGCCTACAGTTAGTGAACA-3′ and 5′-CTGAAAGCTATCTGGACTGAAGCC-3′). Amplification was carried out using the following conditions: one cycle at 95°C 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C 30s, 62°C 30s and 72°C 30s followed by one 72°C 5 min incubation.

Data analysis

The statistical significance of the difference between treatment groups was determined by a one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA (for neurite outgrowth analysis) or Student's t-test as appropriate using GraphPad Prism4 software (La Jolla, CA). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

HSV-Sox11 drives expression of Sox11 mRNA and protein in vitro

To increase the level of Sox11 expression in DRG neurons in culture and in vivo we cloned the mouse Sox11 cDNA into replication incompetent herpes simplex virus (HSV) vectors (Mata, et al., 2002). The Sox11 cDNA and a Sox11-HA tagged variant were regulated using the human CMV promoter and HSV sequences that contain deletions (Δ) of the ICP4 and ICP27 proteins (Fig.1A). HSV vector function was first tested and dose optimized by treating Neuro2A cells and cultured adult DRG neurons with either HSV-GFP control vector, HSV-Sox11-HA or HSV-Sox11. HSV-Sox11 was found to increase the level of Sox11 above that normally expressed by these cell types. At 24h, HSV-Sox11-HA treated cultures had an increased percentage of Sox11/HA-positive neurons; colabeled Neuro2A cells increased from 26.5% (36/136) to 88.3% (128/137) and colabeled DRG neurons increased from 28.1% (54/192) to 59.2% (128/210) (Fig. 1B-C’). Small, medium and large diameter Sox11- and HA-positive neurons were labeled indicating no preference for HSV uptake across neuron subtypes. HSV-Sox11 treatment also increased Sox11 mRNA level in Neuro2A cells (13.3-fold) and DRG cultures (3.1-fold) (both relative to HSV-GFP control; n=3 for each analysis, p<0.01). Immunoblots of protein from cultured DRG neurons also showed increased Sox11 relative to untreated (wildtype) or HSV-GFP treated neurons (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, on repeated analysis a consistent reduction in Sox11 protein in HSV-GFP infected cultures was noted. This decrease may be in response to the significant increase in eGFP protein, which may inhibit expression or destabilize the Sox11 protein. This effect was not seen in vivo however (see below), which may reflect a less efficient per cell transfection of the virus in the in vivo system.

Sox11 increases neurite elongation and branching in vitro

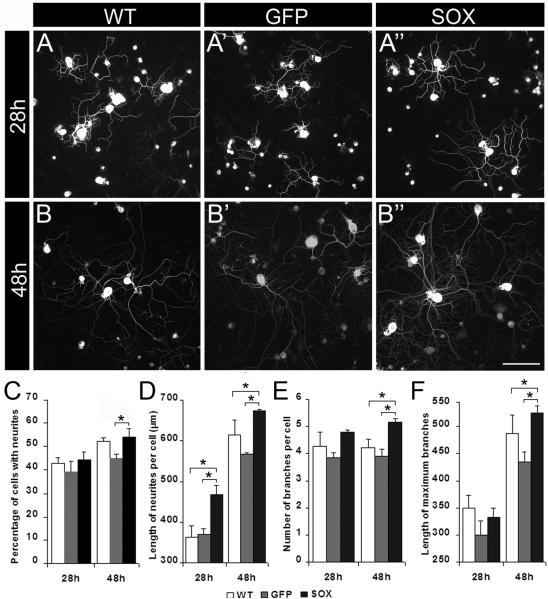

To examine the effect of increased Sox11 on neuron growth properties we first measured neurite projections in DRG neurons transfected with HSV-Sox11 (Fig. 2). At 28h after plating the percentage of HSV-Sox11 treated neurons with neurites was unchanged relative to untreated (wildtype, WT) and HSV-GFP treated cultures (Fig. 2C). The number of branches and the length of the maximum branch were also equivalent at 28h (Fig. 2E, F). The average neurite length (Fig. 2A-A”, 2D) was however significantly greater in HSV-Sox11 treated neurons compared to either WT or HSV-GFP treated groups. At 48 h after plating, HSV-Sox11 treated neurons continued to show enhanced neurite length per cell (Fig. 2B-B”, 2D), they also had greater branching (Fig. 2E) and the length of the maximal branch was greater (Fig. F).

Figure 2. HSV mediated gene transfer of Sox11 promotes neurite extension and branching in vitro.

Representative images show DRG neurons that were untreated (A, B), infected with HSV-GFP (A’, B’) or with HSV-Sox11 vectors (A’’, B’’). Analysis of neurons labeled with anti-β-tubulin III showed HSV-Sox11 increased average neurite length at 28h and 48h post treatment (D, P<0.01). At 48h the number of branches per cell (E) and the length of the longest branch (F) also increased relative to untreated control groups (P<0.05). At 48h, HSV-Sox11 treated neurons had more neurites but only relative to HSV-GFP controls (C, P<0.01); this may reflect a GFP-specific inhibition in cultured neurons. No other difference between WT and HSV-GFP cultures was significant. Data is collected from 3 independent experiments with over 600 cells analyzed per group. Scale bar in B” = 100 μm.

HSV-mediated expression of GFP reduced Sox11 in culture (Fig. 1D). This could potentially reduce neuron survival, which would impact our comparisons of neurite properties. To assess this possibility we compared across treatment groups the expression of activated caspase 3, a protein marker implicated in many models of DRG neuron apoptosis (Gladman, et al., 2010, Jin, et al., 2005). No difference in the percentage of activated caspase 3 was found between groups (3.23% and 2.63% in HSV-GFP; 2.67% and 2.54% in HSV-Sox11 cultures, at 28h and 48h, respectively; at least 1500 cells were analyzed per group, P>0.1) suggesting no effect of eGFP on cell survival.

HSV-Sox11 increases Sox11 expression in DRG neurons in vivo

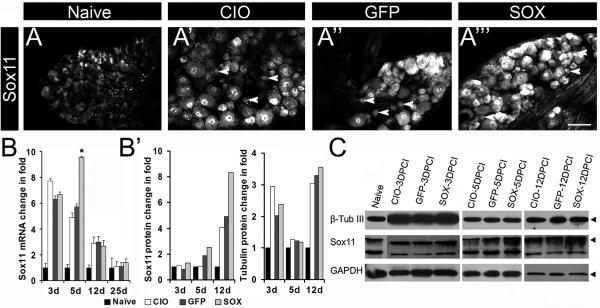

To assess the effect of HSV-Sox11 on nerve regeneration in vivo we injected HSV vectors in the dorsal medial foot skin and measured parameters of regeneration at four timepoints following saphenous nerve crush. We first determined that skin injection of HSV-Sox11 or HSV-GFP was sufficient for retrograde transport of viral vectors to DRG cell bodies. In groups of mice injected with virus but not injured, a 115% increase in Sox11 mRNA in the lumbar L2/L3 ganglia was measured at 5d post injection relative to HSV-GFP controls (n=6, P<0.05), indicating successful vector transport and activity. Other groups of mice were then injected with virus and the saphenous nerve was crushed at 3d after injection. Saphenous nerves and lumbar ganglia were then collected for analysis at 3, 5, 12 and 25 days post crush injury (DPCI). As shown previously (Jankowski, et al., 2009), crush injury increased Sox11 immunoreactivity in nuclei of lumbar L2-L3 DRG neurons (Fig. 3A’-A”’). Neurons in HSV-Sox11 ganglia showed greater cytoplasmic and nuclear labeling relative to crush injury only (CIO) and HSV-GFP treated ganglion, reflecting the increased expression of Sox11 protein. In addition, a significant increase in Sox11 mRNA, above the expected injury only-induced level, was also measured in HSV-Sox11 ganglia at 5 DPCI (Fig. 3B). Similarly, immunoblot analysis showed a clear increase in Sox11 protein at 5 DPCI and 12 DPCI (Fig. 3B’, C). HSV-Sox11 did not significantly affect the level of the injury associated protein •-tubulin III, whose level was equivalent across groups at each of the measured timepoints (see also Appendix Table A1).

Figure 3. HSV-Sox11 increases Sox11 expression in injured peripheral neurons.

DRG from naïve mice and mice with saphenous nerve injury were collected at 5DPCI and immunolabeled with anti-Sox11 (A-A’’’). Increased immunoreactivity occurs in CIO, HSV-GFP and HSV-Sox11 sections relative to naïve sections. Arrowheads indicate smaller neurons that are Sox11-positive. B. Sox11 mRNA increased in all treatment groups relative to naïve with the greatest change in HSV-Sox11 DRG at 5d post injury (P<0.05, n=6). B’-C. Increased levels of Sox11 protein shown by western blot analysis of L2/L3 DRG collected at 3, 5 and 12 DPCI. Sox11 increases in HSV-Sox11 treated mice relative to naïve, CIO or GFP controls. β-TubIII expression was unchanged across treatment groups (B’). Scale bar in A”’ = 100 μm.

Sox11 promotes regeneration of injured axons

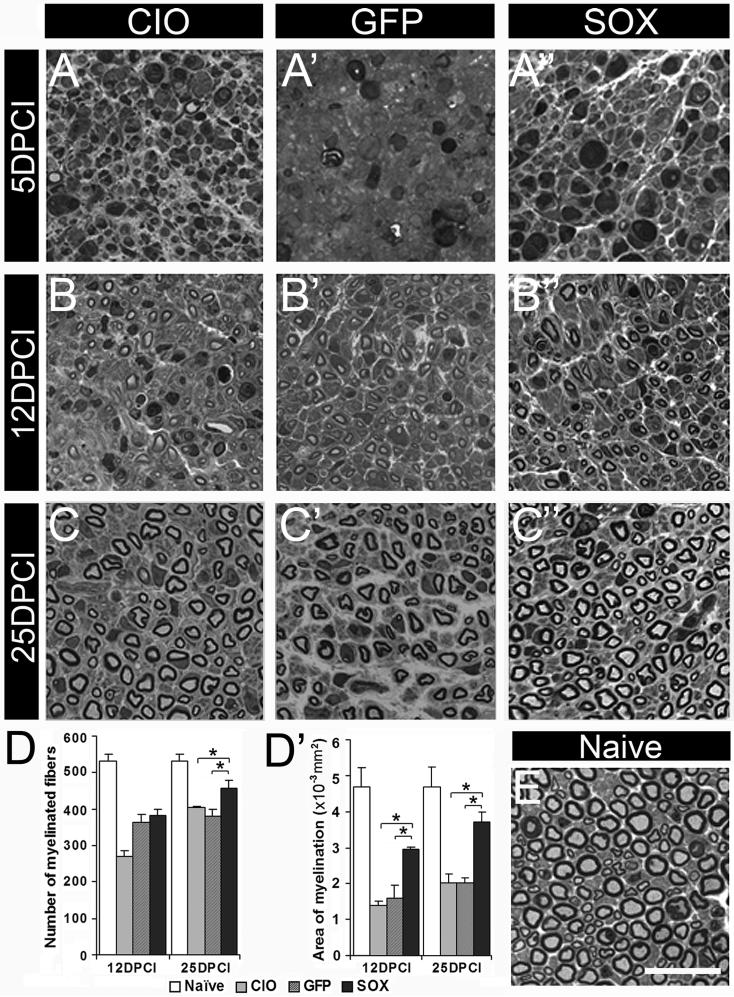

Histomorphometric analysis of cross-sections of crushed nerves from HSV-Sox11 and control treated mice were made to assess myelinated fiber number and myelin thickness. Semi-thin sections collected distal to the injury site were analyzed at 5, 12 and 25 days post crush injury (Fig. 4). Massive fiber degeneration was seen at 5 DPCI (Fig. 4A-A’’), which restricted analysis of myelinated fiber number and myelin to 12 and 25 DPCI. At 12 DPCI there was no difference in the total number of fibers between groups. At 25 DPCI a significant increase in myelinated fiber number was measured in the HSV-Sox11 group relative to the crush injury only (CIO) and HSV-GFP groups (Fig. 4C-C”, D). In addition, the average area of toluidine blue stained myelin (Fig. 4D’) and myelin sheath thickness (Appendix Table 2A) were greater in HSV-Sox11 treated nerves. The increase in myelin thickness was reflected in measures of the g-ratio across treatment groups. The g-ratio is the ratio of axonal diameter /diameter of the axon plus myelin. At 25d post injury the average g ratio was lower in nerves of Sox11 treated mice (0.57) relative to CIO (0.67) and HSV-GFP (0.60) groups (see Appendix Table A2), indicating a general increase in myelin thickness in HSV-Sox11 treated nerve profiles (Fig. 4D’).

Figure 4. Histomorphometric analysis of saphenous nerves.

Light level micrographs of toluidine blue stained transverse semi-thin sections at 3 mm distal to the injury were used to determine the number of myelinated fibers and myelin thickness. Representative images of nerves collected at 5 (A-A’’), 12 (B-B’’) and 25 DPCI (C-C’’) from CIO (A, B, C), HSV-GFP (A’, B’, C’) and HSV-Sox11 groups (A’’, B’’, C’’) are shown. Naïve littermate (E) is included for comparison. At 5d crushed nerves were swollen with degenerating axons with collapsed myelin. A significant increase in both the number of myelinated profiles (D) and average area of myelin (D’) occurs by 25d in nerves of HSV-Sox11 treated animals. n = 4 per group, * P<0.01, determined by two-tailed Student's t-test. Scale bar in E = 20μm.

Sox11 accelerates functional regeneration of nerve fibers to the skin

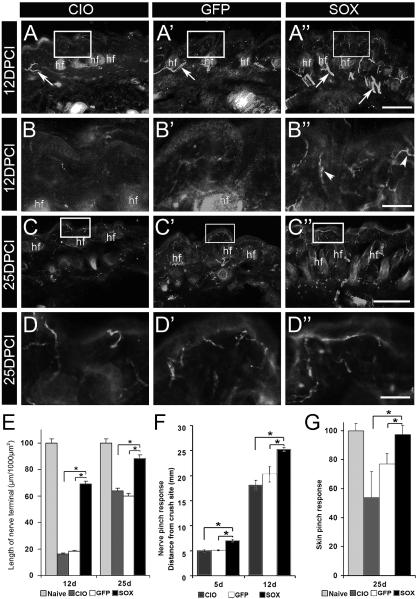

Anatomical and functional indicators of nerve regeneration to the skin were also assessed. Target reinnervation was analyzed using serial sections of skin from the medial aspect of the foot dorsum, an area innervated by the saphenous nerve (Appendix Fig. A1). By 5 DPCI the epidermis of all treatment groups was devoid of fibers positive for the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5, consistent with previous studies of skin reinnervation (Hsieh, et al., 2000, Jankowski, et al., 2009). By 12 DPCI, measures of the sum length of PGP9.5-positive fibers across dermal and epidermal fields of HSV-Sox11 treated mice showed restoration of innervation to approximately 69% of naïve skin (Fig. 5A-B” and E). Significantly fewer nerve fibers were measured in CIO or HSV-GFP control sections. At 25 DPCI, the sum length of terminals in HSV-Sox11 samples was 88% of the naïve innervation density compared to 60% in HSV-GFP sections. The accelerated reinnervation in HSV-Sox11 samples was also consistent with return of sensory function. Responses to light pinching of the exposed saphenous nerve indicated faster regeneration and functional recovery in HSV-Sox11 treated mice (Fig. 5F). Similarly, normal responses to a skin pinch stimulus in the saphenous field were reestablished in HSV-Sox11 mice by 25d compared to HSV-GFP and CIO control groups (Fig. 5G).

Figure 5. HSV-Sox11 enhances nerve regeneration to the skin and functional recovery.

Saphenous nerves were crushed at 3d post HSV inoculation and skin overlying the saphenous innervation field (see Fig. A1) was analyzed. Shown are representative images of sections stained with PGP9.5 taken at low (A-A”, C-C”) and higher (B-B”, D-D”) magnification at 12 (A-B”) and 25 (C-D’’) DPCI. Boxed areas indicate region of magnification. Few dermal fibers (arrows) and virtually no epidermal fibers were visible at 12 DPCI in CIO and HSV-GFP samples (A, A’). However, skin of HSV-Sox injected animals showed numerous fibers in the dermis (arrows, A’’) and approaching the epidermis (arrowheads, B”). At 25 DPCI, epidermal fibers were present in all treatment groups (C-D’’). E. Overall length of PGP9.5-positive fibers relative to epidermal length at 12 and 25 DPCI is greatest in HSV-Sox11 injected skin. F. Nerve responses to pinch assessed at 5 and 12 DPCI showed greater responses in Sox11 treated animals. G. A skin pinch test also showed HSV-Sox11 treatment accelerated functional recovery of skin in the saphenous nerve field at 25 DPCI (n=6 per group). Scale bar in A” and C” = 50 μm, in B” and D” = 15μm; n=6 in F and G. * P<0.01.

The faster functional recovery in HSV-Sox11 mice could reflect changes in the skin due to expression of HSV-Sox11 in surrounding skin cells. However, analysis of Sox11 mRNA in foot skin of HSV-Sox11, HSV-GFP and CIO treated mice at 12d or 25d showed undetectable levels by RT-PCR and ethidium bromide gel electrophoresis (although a strong Gapdh band was present; not shown). The lack of Sox11 mRNA suggests HSV-Sox11 is not expressed at appreciable levels in the adult skin.

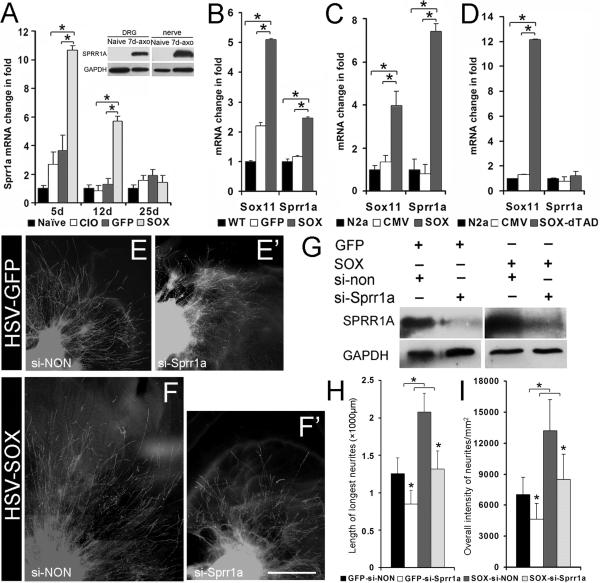

Sox11 increases expression of the regeneration-associated gene Sprr1a

To explore how HSV-Sox11 could enhance nerve regeneration we examined the relative expression of several regeneration-associated genes. Real time RT-PCR analysis of L2/L3 ganglia from mice with crushed nerves treated with either HSV-Sox11 or HSV-GFP showed no substantial difference in ATF3, GAP43, N-cadherin or β-tubulin III mRNA levels (Appendix, Table 1A). However, a significant increase was measured in the regeneration-associated gene, small proline-rich repeat protein 1A (Sprr1a). Sprr1a mRNA and protein have been shown to markedly increase in response to sciatic nerve injury (Fig. 6A, inset, and (Bonilla, et al., 2002, Kartasova and van de Putte, 1988, Marklund, et al., 2006, Starkey, et al., 2009). This increase also occurs following saphenous nerve crush (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, comparison of HSV-Sox11 treated ganglia to CIO and HSV-GFP groups at 5d and 12d after injury showed a significantly greater level of Sprr1a mRNA (Fig. 6A). In addition, treatment of cultured DRG neurons (Fig. 6B) or Neuro2A cells (Fig. 6C) with HSV-Sox11 or pCMV-Sox11 plasmids, respectively, increased Sprr1a mRNA (up to 2.5-fold in cultured DRG neurons and 7-fold in Neuro2A cells). This increase was dependent on functional Sox11 protein since transfection with pSox-11FΔTAD, a plasmid that expresses a Sox11 variant that lacks the carboxyterminal transactivation domain (TAD), failed to increase Sprr1a mRNA (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Sprr1a transcription is required for stimulation of axon growth by Sox11.

A. Saphenous nerve crush increases Sprr1a mRNA in ganglia of HSV-Sox11 treated mice at 5 and 12 DPCI (n=6 at 5DPCI, all other days n=4, asterisks indicate P<0.001). Inset: Western blot shows rise in Sprr1a protein in DRG and sciatic nerve at 7d post sciatic axotomy as previously reported (Bonilla, et al., 2002). B. HSV-Sox11 increases Sprr1a expression in cultured DRG neurons relative to WT and HSV-GFP control groups. Measures were made at 6d postinfection (cultures derived from n=3 mice, P<0.01). C. Neuro2A cells transfected with pCMV-Sox11 plasmid increase Sprr1a mRNA at 24h post transfection (n=3, P<0.01). D. Sprr1a gene activation does not occur in Neuro2A cells transfected with a mutant Sox11 that lacks the transactivation domain (Sox-11FΔTAD) (n=3, asterisks indicate P<0.01). E-I. Sprr1a transcription is required for Sox11 stimulation of axon growth. HSV-GFP or HSV-Sox11 treated DRG explants (E-F’) or dissociated cell cultures (G) were transfected with non-targeting (si-NON; E, F) or Sprr1a targeted siRNAs (si-Sprr1a; E’, F’). HSV-Sox11 explants treated with non-targeting siRNA (F) showed enhanced neurite growth relative to HSV-GFP controls (E). Treatment with siRNA to Sprr1a blocked the Sox11 effect (F’). Western blots in G show effective Sprr1a knockdown in DRG cultures treated with HSV-GFP or HSV-Sox11. Quantification of neurite lengths and intensity of TuJ1-positive neurite labeling are plotted in H and I. * P<0.05.

Activation of Sprr1a is required for most but not all of the stimulatory effect of Sox11 on axon growth

The marked increase in Sprr1a elicited by Sox11 overexpression suggested its transcriptional activation was a significant component of the regenerative changes elicited by Sox11 during nerve regeneration. To further examine this relationship we used siRNA to reduce Sprr1a expression in DRG explant cultures that were transfected with HSV-Sox11 and then assessed axon growth (Fig. 6 E-I). Explant cultures were used because they can be transfected with virus and siRNA and they allow a relatively easy assessment of neurite outgrowth. In addition, the time required for HSV infection (3d) and Sprr1a knockdown (2d) in dissociated cultures would require measures of neurite outgrowth be made at 5d after plating, a time at which accurate analysis would be impossible because of the extensive neurite growth. Analysis of explant cultures treated with either nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 6E, F) or Sprr1a targeted siRNAs (Fig. 6 E’, F’) showed that Sprr1a knockdown significantly reduced the stimulatory effect of Sox11 on neurite outgrowth (Fig. 6H). Interestingly, neurite length in Sprr1a siRNA/HSV-Sox11 treated cultures still exceeded that measured in Sprr1a siRNA/HSV-GFP controls (Fig. 6H, I). Thus, Sox11-mediated transcription of Sprr1a appears to be required for the full stimulatory effect of Sox11 on axon growth but other regeneration-associated genes, which may also be regulated by Sox11, contribute to this process.

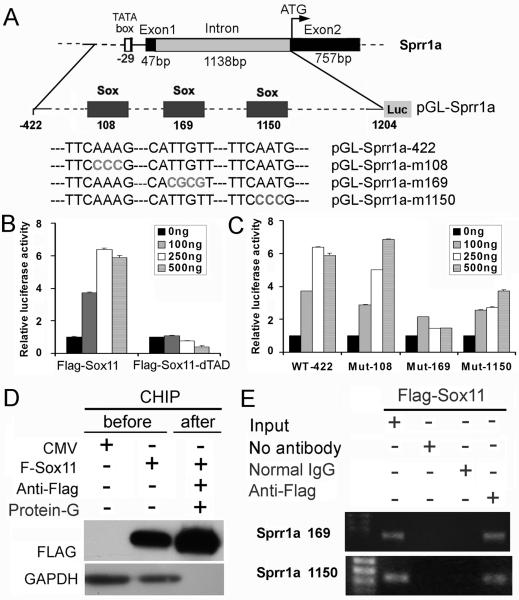

Sox11 binds to sites in Sprr1a intron 1

To examine how Sox11 might modulate transcription of Sprr1a bioinformatic analysis was used to identify putative Sox binding sites in upstream sequences of Sprr1a. We focused analysis on three putative Sox sites within the first intron of Sprr1a identified by screening with the consensus sequence 5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G-3′) (Fig. 7A). Luciferase reporter assays done in Neuro2A cells showed that cotransfection of pCMVSox11 and pGL-Sprr1a-422, a reporter construct containing 1626 bp of the promoter/intron 1 sequence of Sprr1a, increased luciferase activity in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 7B). Importantly, transfection of pSox-11FΔTAD failed to activate the pGL-Sprr1a-422 reporter, indicating an essential requirement of the Sox11 transactivation domain for Sprr1a promoter activation. This finding is in agreement with the cell transfection data in Fig. 6D. To determine if Sox sites in intron 1 were required for pGL-Sprr1a activation, site-directed mutagenesis of core residues at each predicted site (nt108, nt169 and nt1150) was performed followed by luciferase reporter analysis (Fig. 7C). Mutations were found to have dose dependent and site-specific effects; significant reductions occurred in reporter activity of constructs containing mutations made at nt169 and nt1150 whereas mutation at nt108 did not affect Sox11 activity (Fig. 7C). These findings indicate that Sox11 can directly activate Sprr1A transcription and that two sites in intron 1 contribute to this activation.

Figure 7. Sox11 regulates transcription of Sprr1a.

A. Diagram of the Sprr1a promoter/intron construct used in this study. Small grey boxes indicate predicted Sox binding sites at nt108, nt169 and nt1150 with the start of numbering at the transcription start site. Sequences of core nucleotides of wildtype and mutated Sox sites (grey lettering) are shown below. B. pGL-Sprr1a-luciferase plasmids were transfected into Neuro2A cells in combination with 0, 100, 250, 500ng of empty CMV vector, pCMV-Sox11F or pCMVSox-11FΔTAD. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate and normalized to the CMV empty vector whose value was set to 1. C. pGL2-Sprr1a-422 activity is suppressed following mutation of Sox-binding sites at nt169 and nt1150 but not nt108. D. Western blot shows enrichment of Sox-11F protein in ChIP samples immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG antibody. E. ChIP assay shows Sox11 binding to endogenous Sprr1a at nt169 and nt1150 sites. Chromatin extracts from Neuro2A cells transiently expressing Sox-11F were precipitated with no antibody, with non-immune mouse IgG or with FLAG antibody. PCR products from immunoprecipitated chromatin and starting input are shown on ethidium stained agarose gel.

To test for direct binding of Sox11 at nt169 and nt1150 we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. Neuro2A cells were used to express a FLAG-tagged Sox11 protein that was used for immunoprecipitation. Anti-FLAG western blots confirmed the specificity of the FLAG antibody and enrichment of FLAG-Sox11 protein in the anti-FLAG/Protein-G precipitated samples (Fig. 7D). Cross-linked chromatin extracts precipitated with anti-FLAG and processed for PCR amplification of DNA flanking each Sox site showed specific amplification of fragments immediately flanking nt169 and nt1150 (Fig. 7E). Collectively, these results indicate that Sprr1a is a transcriptional target of Sox11 and that its injury-induced transcription is dependent on Sox11 activity.

DISCUSSION

In response to a crush or cut injury peripheral nerves undergo Wallerian degeneration in the distal portion of the nerve and sprouting and axonal regeneration at the proximal site. The injury-induced up-regulation of regeneration-associated genes is essential for these processes to effectively restore nerve structure and function (Costigan, et al., 2002, Makwana and Raivich, 2005, Schmitt, et al., 2003, Snider, et al., 2002, Sun and He, 2010, Xiao, et al., 2002). In this study we asked if skin inoculation with HSV viral vectors that express Sox11 would alter DRG neuron regeneration by ‘priming’ a Sox11-driven transcriptional response program. HSV-Sox11 vectors increased Sox11 expression in the DRG and at anatomical and functional levels, increased the overall rate at which axons regenerated following crush injury. These findings complement previous studies that showed RNAi-mediated knockdown in Sox11 inhibited neurite growth in vitro and regeneration in vivo (Jankowski, et al., 2006, Jankowski, et al., 2009). They also suggest that Sox11 increases the intrinsic growth potential of adult neurons and parallel studies of other regeneration associated proteins such as ATF3 and GAP43 (Hoffman, 2009). For example, overexpression of ATF3 in neurons has been shown to enhance neurite outgrowth of cultured DRG neurons and growth following nerve injury (Bonilla, et al., 2002, Seijffers, et al., 2007). Interestingly, like ATF3, Sox11 is only expressed at relatively low levels (~2-fold) in response to injury of centrally projecting axons (Jankowski, et al., 2006), which are known to regenerate poorly if at all. Thus, Sox11 may be another essential component of an intrinsic transcriptional program whose activation is required to facilitate central terminal regeneration.

The robust expression of Sox11 in developing peripheral neurons and recent studies of Sox11 gene knockin mice support an important role for Sox11 in regulating genes that control neuron survival, proliferation and axon outgrowth (Hargrave, et al., 1997, Lin, et al., 2011, Potzner, et al., 2010). Mice that lack functional Sox11 display inhibition of embryonic axon growth and significant reduction in embryonic neuron survival (Lin, et al., 2011). Similar phenotypes are expressed in adult mice treated with Sox11 siRNAs (Jankowski, et al., 2006, Jankowski, et al., 2009). The significant induction of Sox11 in injured adult neurons and similarity in function suggests that injury may recapitulate at least a portion of a developmentally active transcriptional program in the adult system. That said, developing sensory ganglia do not appear to express Sprr1a protein (Bonilla, et al., 2002), which these data indicate is essential to the Sox11-mediated enhancement. In addition, during neural development Sox11 is typically coexpressed with and has redundant function with Sox4 (Bhattaram, et al., 2010), another Group C Sox family member whose mRNA level we found to be unchanged following adult nerve injury (data not shown). Although this does not exclude a function for Sox4 in regeneration, the absence of transcriptional level coactivation suggests dissociation of these factors in adult neurons and activation of a unique adult specific program.

Transcriptional analysis of regeneration-associated genes modulated by HSV-Sox11 showed a significant increase in Sprr1a transcription. Sprr1a is a member of a multigene family of proteins first identified as major components of the cross-linked cornified envelop of skin keratinocytes (Kartasova and van de Putte, 1988). Increased expression of SPRR family proteins has since been reported in response to stress and tissue injury across multiple organ systems (Vermeij and Backendorf, 2010). In the case of nerve injury, a significant rise in Sprr1a occurs in virtually all types of injured neurons (CGRP-, IB4- and NF200-positive) by 1 wk post-injury (Bonilla, et al., 2002, Starkey, et al., 2009). Sprr1a expression coincides with ATF3 and GAP43 expression and HSV-Sprr1a infection increased outgrowth of cultured DRG neurons (Bonilla, et al., 2002, Starkey, et al., 2009). In addition, reduction in Sprr1a by antisense or antibody blockade decreased neurite growth (Bonilla, et al., 2002). Sprr1a immunoreactivity was most intense in actin-rich domains of the plasma membrane of transfected Cos cells and in cell bodies and axons of DRG neurons (Bonilla, et al., 2002). Interestingly, reactivity was also found in neuronal nuclei following brain injury or axotomy of DRG neurons suggesting functional roles in nuclear as well as cytoplasmic compartments (this study and (Marklund, et al., 2006, Starkey, et al., 2009). Sprr1a has a high content of serine, lysine and glutamine residues (Kartasova and van de Putte, 1988) that could facilitate DNA-binding or protein interactions. Recent studies in skin have also suggested a role for SPRR proteins as protectors against damage from reactive oxygen species during wound healing (Vermeij and Backendorf, 2010). A similar protective function in injured neurons could promote faster regrowth and stabilization of regenerating axons.

The effects of Sox11 overexpression on neurite outgrowth were blocked in neurons in which the rise of Sprr1a was inhibited by Sprr1a siRNAs. Thus the transcriptional activation of Sprr1a by Sox11 is a critical step in nerve regeneration. Sequence analysis identified three putative Sox binding sites in the first intron of Sprr1a. Since it is well known that intronic sequences have elements that can modulate transcriptional activity (Levine and Tjian, 2003), which include the SPRR family proteins involucrin and SPRR2A (Carroll and Taichman, 1992, Fischer, et al., 1998), we asked whether Sox11 regulated Sprr1a promoter activity by binding in intron 1. Luciferase reporter assays showed a dose dependent increase in Sprr1a activity that was absent in assays conducted using a mutated Sox11 protein. In addition, site directed mutagenesis and ChIP binding assays predict that two of the three Sox motifs in Sprr1a intron 1 bind Sox11 and contribute to optimal Sprr1a promoter activity. Interestingly, a recent study of Sox 4 showed that it too binds in an intronic sequence, in this case in the gene encoding the transcription factor Tead2 (Bhattaram, et al., 2010).

As a HMG box containing transcription factor, Sox11 is predicted to bind in the minor groove of DNA and in so doing cause a significant bend in the DNA backbone (Harley, et al., 1994). The ability to bend DNA implies an architectural role for Sox factors in assembling and stabilizing DNA complexes to facilitate efficient transcriptional activity (Harley, et al., 1994, Kondoh and Kamachi, 2010, Wiebe, et al., 2003, Zlatanova and van Holde, 1998). In addition, the C-terminal transactivation domain of Sox11 (Kuhlbrodt, et al., 1998) has also been shown to be essential for gene activation (Wiebe, et al., 2003). This is particularly evident from the present studies that show Sox11 without a TAD is ineffective in stimulating Sprr1a reporter activity. Although other regeneration-associated genes are almost certainly regulated by Sox11, the current findings identify a new linkage between Sox11 and Sprr1a and enhance our understanding of the complex molecular program activated during successful regeneration of adult neurons.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding of the cellular mechanisms that control anatomical and functional recovery following nerve injury is important for providing the most effective therapeutic outcome. Towards this goal, this study evaluated the role of the transcription factor Sox11 in adult nerve regeneration using in vitro and in vivo model systems. Cultured mouse DRG neurons treated with replication incompetent HSV vectors that express Sox11 had greater neurite elongation and branching. For in vivo analysis cutaneous injection of HSV-Sox11 vectors was used to drive expression of Sox11 in DRG neurons prior to saphenous nerve crush. Increased levels of Sox11 correlated with faster axon growth, restoration of skin innervation and return of functional activity relative to naïve and HSV-GFP treated control mice. Mechanistically, these changes are due, at least in part, to the Sox11-mediated transcription of the regeneration-associated gene Sprr1a; an increase in Sprr1a was required for the growth-promoting effect of Sox11. These studies also suggest that delivery of genes that promote nerve regeneration is feasible using HSV type 1 viral vectors that contain genetic modifications that limit replication and control tissue and temporal expression parameters.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The effect of the transcription factor Sox11 on axonal regeneration was evaluated.

Sox11 expression in cultured neurons increased neurite elongation and branching.

Cutaneous delivery of Sox11 via HSV vectors accelerated saphenous nerve regeneration.

Sox11 regulates transcription of the regeneration-associated gene Sprr1a.

Stimulation of neurite growth by Sox11 is dependent on its activation of Sprr1a.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mingdi Zhang for technical assistance and Michael Jankowski, Kathleen Salerno and Brian Davis for helpful advice. This work was supported by NINDS grant #NS059003 to KMA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe N, Cavalli V. Nerve injury signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badis G, Berger MF, Philippakis AA, Talukder S, Gehrke AR, Jaeger SA, Chan ET, Metzler G, Vedenko A, Chen X, Kuznetsov H, Wang CF, Coburn D, Newburger DE, Morris Q, Hughes TR, Bulyk ML. Diversity and complexity in DNA recognition by transcription factors. Science. 2009;324:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1162327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergsland M, Werme M, Malewicz M, Perlmann T, Muhr J. The establishment of neuronal properties is controlled by Sox4 and Sox11. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3475–3486. doi: 10.1101/gad.403406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattaram P, Penzo-Mendez A, Sock E, Colmenares C, Kaneko KJ, Vassilev A, Depamphilis ML, Wegner M, Lefebvre V. Organogenesis relies on SoxC transcription factors for the survival of neural and mesenchymal progenitors. Nat Commun. 2010;1:9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonilla IE, Tanabe K, Strittmatter SM. Small proline-rich repeat protein 1A is expressed by axotomized neurons and promotes axonal outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1303–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01303.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridge PM, Ball DJ, Mackinnon SE, Nakao Y, Brandt K, Hunter DA, Hertl C. Nerve crush injuries--a model for axonotmesis. Exp Neurol. 1994;127:284–290. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll JM, Taichman LB. Characterization of the human involucrin promoter using a transient beta-galactosidase assay. J Cell Sci. 1992;103(Pt 4):925–930. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costigan M, Befort K, Karchewski L, Griffin RS, D'Urso D, Allchorne A, Sitarski J, Mannion JW, Pratt RE, Woolf CJ. Replicate high-density rat genome oligonucleotide microarrays reveal hundreds of regulated genes in the dorsal root ganglion after peripheral nerve injury. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer DF, van Drunen CM, Winkler GS, van de Putte P, Backendorf C. Involvement of a nuclear matrix association region in the regulation of the SPRR2A keratinocyte terminal differentiation marker. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5288–5294. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladman SJ, Ward RE, Michael-Titus AT, Knight MM, Priestley JV. The effect of mechanical strain or hypoxia on cell death in subpopulations of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2010;171:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goins WF, Krisky DM, Wechuck JB, Huang S, Glorioso JC. Construction and production of recombinant herpes simplex virus vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;433:97–113. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-237-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goins WF, Krisky DM, Wolfe DP, Fink DJ, Glorioso JC. Development of replication-defective herpes simplex virus vectors. Methods Mol Med. 2002;69:481–507. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-141-8:481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargrave M, Wright E, Kun J, Emery J, Cooper L, Koopman P. Expression of the Sox11 gene in mouse embryos suggests roles in neuronal maturation and epithelio-mesenchymal induction. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:79–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199710)210:2<79::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harley VR, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN. Definition of a consensus DNA binding site for SRY. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1500–1501. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.8.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman PN. A conditioning lesion induces changes in gene expression and axonal transport that enhance regeneration by increasing the intrinsic growth state of axons. Exp Neurol. 2009;223:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh ST, Chiang HY, Lin WM. Pathology of nerve terminal degeneration in the skin. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:297–307. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jankowski MP, Cornuet PK, McIlwrath S, Koerber HR, Albers KM. SRY-box containing gene 11 (Sox11) transcription factor is required for neuron survival and neurite growth. Neuroscience. 2006;143:501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jankowski MP, Lawson JJ, McIlwrath SL, Rau KK, Anderson CE, Albers KM, Koerber HR. Sensitization of cutaneous nociceptors after nerve transection and regeneration: possible role of target-derived neurotrophic factor signaling. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1636–1647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3474-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankowski MP, McIlwrath SL, Jing X, Cornuet PK, Salerno KM, Koerber HR, Albers KM. Sox11 transcription factor modulates peripheral nerve regeneration in adult mice. Brain Res. 2009;1256:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins R, Hunt SP. Long-term increase in the levels of c-jun mRNA and jun protein-like immunoreactivity in motor and sensory neurons following axon damage. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin HW, Ichikawa H, Fujita M, Yamaai T, Mukae K, Nomura K, Sugimoto T. Involvement of caspase cascade in capsaicin-induced apoptosis of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 2005;1056:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kartasova T, van de Putte P. Isolation, characterization, and UV-stimulated expression of two families of genes encoding polypeptides of related structure in human epidermal keratinocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2195–2203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondoh H, Kamachi Y. SOX-partner code for cell specification: Regulatory target selection and underlying molecular mechanisms. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhlbrodt K, Herbarth B, Sock E, Enderich J, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Wegner M. Cooperative function of POU proteins and SOX proteins in glial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16050–16057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee N, Neitzel KL, Devlin BK, MacLennan AJ. STAT3 phosphorylation in injured axons before sensory and motor neuron nuclei: potential role for STAT3 as a retrograde signaling transcription factor. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:535–545. doi: 10.1002/cne.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefebvre V, Dumitriu B, Penzo-Mendez A, Han Y, Pallavi B. Control of cell fate and differentiation by Sry-related high-mobility-group box (Sox) transcription factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:2195–2214. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine M, Tjian R. Transcription regulation and animal diversity. Nature. 2003;424:147–151. doi: 10.1038/nature01763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L, Lee VM, Wang Y, Lin JS, Sock E, Wegner M, Lei L. Sox11 regulates survival and axonal growth of embryonic sensory neurons. Dev Dyn. 2011 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makwana M, Raivich G. Molecular mechanisms in successful peripheral regeneration. Febs J. 2005;272:2628–2638. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marklund N, Fulp CT, Shimizu S, Puri R, McMillan A, Strittmatter SM, McIntosh TK. Selective temporal and regional alterations of Nogo-A and small proline-rich repeat protein 1A (SPRR1A) but not Nogo-66 receptor (NgR) occur following traumatic brain injury in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mata M, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ. Targeted gene delivery to the nervous system using herpes simplex virus vectors. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:483–488. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00908-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penzo-Mendez AI. Critical roles for SoxC transcription factors in development and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potzner MR, Tsarovina K, Binder E, Penzo-Mendez A, Lefebvre V, Rohrer H, Wegner M, Sock E. Sequential requirement of Sox4 and Sox11 during development of the sympathetic nervous system. Development. 2010;137:775–784. doi: 10.1242/dev.042101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich KM, Yip HK, Osborne PA, Schmidt RE, Johnson EM., Jr. Role of nerve growth factor in the adult dorsal root ganglia neuron and its response to injury. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:110–118. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schepers GE, Teasdale RD, Koopman P. Twenty pairs of sox: extent, homology, and nomenclature of the mouse and human sox transcription factor gene families. Dev Cell. 2002;3:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt AB, Breuer S, Liman J, Buss A, Schlangen C, Pech K, Hol EM, Brook GA, Noth J, Schwaiger FW. Identification of regeneration-associated genes after central and peripheral nerve injury in the adult rat. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmutzler BS, Roy S, Pittman SK, Meadows RM, Hingtgen CM. Ret-dependent and Ret-independent mechanisms of Gfl-induced sensitization. Mol Pain. 2011;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seijffers R, Mills CD, Woolf CJ. ATF3 increases the intrinsic growth state of DRG neurons to enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7911–7920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5313-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snider WD, Zhou FQ, Zhong J, Markus A. Signaling the pathway to regeneration. Neuron. 2002;35:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sock E, Rettig SD, Enderich J, Bosl MR, Tamm ER, Wegner M. Gene targeting reveals a widespread role for the high-mobility-group transcription factor Sox11 in tissue remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6635–6644. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6635-6644.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starkey ML, Davies M, Yip PK, Carter LM, Wong DJ, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ. Expression of the regeneration-associated protein SPRR1A in primary sensory neurons and spinal cord of the adult mouse following peripheral and central injury. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:51–68. doi: 10.1002/cne.21944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun F, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic barriers for axon regeneration in the adult CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanabe K, Bonilla I, Winkles JA, Strittmatter SM. Fibroblast growth factor-inducible-14 is induced in axotomized neurons and promotes neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9675–9686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09675.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tonge DA, Golding JP, Edbladh M, Kroon M, Ekstrom PE, Edstrom A. Effects of extracellular matrix components on axonal outgrowth from peripheral nerves of adult animals in vitro. Exp Neurol. 1997;146:81–90. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsujino H, Kondo E, Fukuoka T, Dai Y, Tokunaga A, Miki K, Yonenobu K, Ochi T, Noguchi K. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) induction by axotomy in sensory and motoneurons: A novel neuronal marker of nerve injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2000;15:170–182. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermeij WP, Backendorf C. Skin cornification proteins provide global link between ROS detoxification and cell migration during wound healing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wegner M. All purpose Sox: The many roles of Sox proteins in gene expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiebe MS, Nowling TK, Rizzino A. Identification of novel domains within Sox-2 and Sox-11 involved in autoinhibition of DNA binding and partnership specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17901–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao HS, Huang QH, Zhang FX, Bao L, Lu YJ, Guo C, Yang L, Huang WJ, Fu G, Xu SH, Cheng XP, Yan Q, Zhu ZD, Zhang X, Chen Z, Han ZG, Zhang X. Identification of gene expression profile of dorsal root ganglion in the rat peripheral axotomy model of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8360–8365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122231899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zlatanova J, van Holde K. Binding to four-way junction DNA: a common property of architectural proteins? FASEB J. 1998;12:421–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.