Abstract

Antenatal corticosteroid (AC) treatment is given to pregnant women at risk for preterm birth to reduce infant morbidity and mortality by enhancing lung and brain maturation. However, there is no accepted regimen on how frequently AC treatments should be given and some studies found that repeated AC treatments can cause growth retardation and brain damage. Our goal was to assess the dose-dependent effects of repeated AC treatment and estimate the critical number of AC courses to cause harmful effects on the auditory brainstem response (ABR), a sensitive measure of brain development, neural transmission and hearing loss. We hypothesized that repeated AC treatment would have harmful effects on the offspring’s ABRs and growth only if more than 3 AC treatment courses were given. To test this hypothesis, pregnant Wistar rats were given either a high regimen of AC (HAC), a moderate regimen (MAC), a low regimen (LAC), or saline (SAL). An untreated control (CON) group was also used. Simulating the clinical condition, the HAC dams received 0.2 mg/kg Betamethasone (IM) twice daily for 6 days during gestation days (GD) 17-22. The MAC dams received 3 days of AC treatment followed by 3 days of saline treatment on GD 17-19 and GD 20-22, respectively. The LAC dams received 1 day of AC treatment followed by 5 days of saline treatment on GD 17 and GD 18-22, respectively. The SAL dams received 6 days of saline treatment from GD 17-22 (twice daily, isovolumetric to the HAC injections, IM). The offspring were ABR-tested on postnatal day 24. Results indicated that the ABR’s P4 latencies (neural transmission time) were significantly prolonged (worse) in the HAC pups and that ABR’s thresholds were significantly elevated (worse) in the HAC and MAC pups when compared to the CON pups. The HAC and MAC pups were also growth retarded and had higher postnatal mortality than the CON pups. The SAL and LAC pups showed little or no adverse effects. In conclusion, repeated AC treatment had harmful effects on the rat offspring’s ABRs, postnatal growth and survival. The prolonged ABR latencies reflect slowed neural transmission times along the auditory nerve and brainstem auditory pathway. The elevated ABR thresholds reflect hearing deficits. We concluded that repeated AC treatment can have harmful neurological, sensory and developmental effects on the rat offspring. These effects should be considered when weighing the benefits and risks of repeated AC treatment and when monitoring and managing the prenatally exposed child for possible adverse effects.

Keywords: Antenatal corticosteroids (AC), Auditory brainstem response (ABR), Barker hypothesis, Betamethasone, Hearing loss, Neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI), Preterm birth, Steroid diabetes

1. Introduction

Preterm birth and low birth weight are serious health problems because they are associated with increased infant morbidity and mortality [2]. The prevalence of preterm birth is about 12-13% of all births or about 400,000 babies per year in the United States [37]. Antenatal corticosteroid (AC) treatment, using the synthetic glucocorticoid Betamethasone, is given to pregnant women at risk for preterm birth to reduce the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome and intracranial hemorrhages by enhancing lung and brain maturation [24,59]. A National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Panel concluded that antenatal corticosteroid therapy is indicated for women at risk of premature delivery with few exceptions because it results in a substantial decrease in neonatal morbidity and mortality [2]. Initially, the accepted treatment regimen was a single course comprised of two Betamethasone injections given 24 hr apart. Because of a concern that the drug’s effects on fetal lung maturation diminishes over time, the vast majority of obstetricians began prescribing repeated courses of Betamethasone at weekly intervals. This is currently being done without evidence demonstrating benefit [67]. The impact of repeated AC treatment is highly important because it is given to virtually every woman at risk for preterm delivery [67].

The efficacy and safety of any prenatal treatment are of paramount importance. Yet, there is no accepted regimen on how frequently AC treatments should be given. At least four different regimens are being used in clinical trials. In one regimen, AC therapy is given only once; whereas in the others, AC therapy is repeated weekly [19,95,96], biweekly [1] or twice [3] from as early as 23 weeks to as late as 32 weeks of gestation. Some pregnant women have received as many as 9 treatment courses of 2 injections per course for a total of 18 AC injections [19,95,96]. Yet, there is concern that repeated AC treatment harms infant development if too much is given [67]. For example, human studies found that repeated AC treatments reduced birth weights and/or head circumferences [19,35,95,96], reduced brain cortex convolutions [65], decreased placental growth [83], increased the incidence of cerebral palsy [95], and caused attention problems at 2 years of age [25]. One study reported that merely two AC courses perturbed respiratory adaptation in preterm infants [70]. Similarly, repeated courses of postnatal corticosteroids can cause brain pathology, cerebral palsy and/or neurodevelopmental problems in children [8,57,66,69,86,99]. In contrast, some human studies on repeated AC treatment found no significant effects on birth weights and/or head circumferences [31,88], neurodevelopmental behavior [57] or neural transmission time as evidenced by the auditory brainstem response (ABR) [4,5,19].

Animal studies are more consistent in finding harmful effects from pre- or postnatal AC treatments. The offspring effects include impaired brain myelination and impaired neurologic development [6,23,29,33,47,58,63], altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function [9,30], decreased hippocampus neuron numbers [93], hyperglycemia [68], impaired sciatic axonal growth [73], impaired retinal maturation [73,74], impaired myelination of optic nerve axons [29], altered behaviors [9,33,45], reduced fecundity [30] and reduced brain weights [33,48,54]. In addition, recent animal studies found abnormal auditory function as a result of fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids [11,44,50]. The presence of glucocorticoid receptors in the cochlea and other auditory regions provides a means for such effects [12,32,44,101].

Combined, the human and animal studies raise concern that the negative consequences of repeated AC treatments may be brain damage and other health disorders. Despite this concern, the practice of giving repeated AC treatment continues in clinical trials and general obstetrical practice. For example, a recent clinical trial concluded that 4 or more AC courses are harmful to the unborn infant but that 3 courses are acceptable [96]. The problem with this conclusion is that the clinical trial was terminated early because of the fetal growth restriction in the repeated AC group. This early termination resulted in a lack of statistical power and an inability to firmly establish 3 courses of AC as a safe dosing regimen. Also, a safe dosing regimen should not be based solely on birth weight and the need for postnatal respiratory support, as with this latter study. Instead, safe dosing should be based on comprehensive neurological assessment as well as long-term outcomes such as neurodevelopmental impairments (NDI) and the “fetal programming” effects of child- and adult-onset health disorders such as hypertension, diabetes, enhanced age-related neural degeneration, mental and behavioral disorders, and shortened life span which can arise from elevated prenatal steroid levels [7,85,98]. It is critical therefore to use outcome variables that assess brain damage and “fetal programming” effects to firmly determine (A) how much AC treatment is too much and (B) the short- and long-term morbidities caused by too much AC treatment. These are critical issues because knowing how much AC treatment is too much will help prevent unnecessary damage to unborn children in the future. Knowing the life-long morbidities will improve the detection and management of children who have already been harmed by too much AC treatment.

With these issues in mind, our goal was to conduct a preliminary animal study that would explore how much AC treatment is too much and to characterize the adverse effects on the nervous system as evidenced by the ABR. The ABR is a sensitive measure of brain development and sensory function that is used to assess hearing and neurological function [13,16-19,21]. It is also an indirect measure of brain myelination [82]. We specifically sought to test the hypothesis that a moderate regimen of 3 AC courses causes no harm to the offspring’s ABR and other outcome variables but that a regimen greater than 3 AC courses would cause harm. Three AC courses has particular importance because it recently has been given in about 85% of preterm cases [75] and has been considered safe by an NIH clinical trial [96].

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and treatments

2.1.1. Animals and husbandry

Wayne State University’s animal investigation committee approved the procedures for this study. Institutional and NIH guidelines were followed.

Female Wistar rats, 10 weeks of age, were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and mated individually in breeding cages. The presence of a sperm plug was designated as gestational day one (GD 1). The pregnant females were then placed in separate polycarbonate cages (25 × 45 × 20 cm). These females were randomly assigned to one of the five treatment groups described below. Dams had free access to food and water. Food consumption and maternal weights were assessed weekly. All animals were housed at ~53% relative humidity and at ~22°C. Day of birth was designated postnatal day one (PND 1). Within 24 hours after delivery, pups were counted and weighed. On PND 2, each litter was culled to 8 pups consisting of 4 male and 4 female offspring when possible. We did not use a surrogate fostering procedure because a previous study showed that repeated AC injections did not affect mothers nursing their pups [68], because fostering pups can modify the consequences of prenatal treatments [61], and because of financial limitations. Pups were weaned on PND 21 and ABR-tested on PND 24.

2.1.2. Treatment conditions and group sizes

The five treatment groups consisted of an untreated control group (CON), a saline treated control group (SAL), a low antenatal corticosteroid group (LAC), a moderate antenatal corticosteroid group (MAC), and a high antenatal corticosteroid group (HAC). The LAC group received 1 AC course because this was the traditionally accepted amount given to pregnant women at risk for preterm delivery [67,96]. The MAC group received 3 AC courses because this is hypothetically the maximum amount that can be given without causing significant harm to unborn human infants [96]. The HAC group received 6 AC courses because this dose approaches the maximum amount given in an NIH clinical trial where as many as 9 AC courses were given [19,96] and because more than 6 AC courses in the rat caused 100% offspring mortality in our pilot study. The SAL group was a placebo group that controlled for maternal handling and injection stress, a condition which can elevate maternal glucocorticoids and adversely affect the rat offspring’s hearing [50]. The CON group was the untreated and unhandled control group to which all other groups were compared. Assignment of the pregnant dams to the various treatment groups was done randomly rather than by matching the dams by weight, although the dams were not mated until they achieved a weight of at least 275 g.

Because of limited financial resources and the principle of reducing animal usage [78], the CON group was borrowed from a concurrent study in our laboratory [16-18]. The CON group consisted of n=23 litters. Because we had some non-viable litters and non-pregnancies, we produced only n=5, 6, 8 and 9 viable litters for the SAL, LAC, MAC and HAC groups, respectively. One CON, 1 SAL, 4 MAC and 3 HAC dams delivered non-viable litters.

Because the human clinical trial used the intramuscular (IM) route for the injections and Betamethasone (BETA) as the corticosteroid treatment, both were used for our animal study. We selected Wistar rats because this strain is commonly used in prenatal corticosteroid studies [97,98]. For pregnant rats receiving AC treatments, each daily treatment consisted of 0.2 mg/kg BETA given twice daily with the first injection at 0900 hr and the second injection at 1500 hr. This is the same dose used in the human clinical trial where one course of AC treatment consisted of two separate injections of 0.2 mg/kg, diluted to 1 mg/ml. Past rat studies successfully used perinatal corticosteroid doses in this range [11,23,87,97]. Moreover, the maternal blood glucocorticoid levels following repeated AC administration at these doses during the last gestational week in rats are highly similar to those seen when repeated AC is given during the 24-34 week gestational window in humans [80,81]. In human clinical trials, AC treatments are spaced at 1 week intervals [19]. Because 1 gestational day for a rat is equivalent to ~6.3 days gestation in the human [34], spacing treatments to the pregnant rat at 1 day intervals closely mimicked the human situation. For pregnant rats receiving saline treatments, each daily treatment consisted of isovolumetric IM injections of normal saline given twice daily with the first injection at 0900 hr and the second injection at 1500 hr. Animal weights and injection volumes were calculated on a daily basis. Injection sites were rotated to reduce soreness.

The treatment period for our pregnant rats was the last week of pregnancy because repeated AC treatments for humans are given during the late stage of pregnancy and studies have used the last week of rat pregnancy as a model for the human clinical condition [11,87,94,97]. Even more relevant to our interests, recent studies showed that elevated maternal glucocorticoid levels through AC treatment [11,44] and handling stress [50] during the last week of pregnancy resulted in abnormal auditory function in the rat offspring. For our rats, the treatment period was from GD 17-22 inclusively, where birth occurs on GD 23. The LAC group received 1 day of BETA treatments on GD 17 followed by 5 days of saline treatments from GD 18-22. The MAC group received 3 days of BETA treatments from GD 17-19 followed by 3 days of saline treatments from GD 20-22. The HAC group received 6 days of BETA treatments from GD 17-22. The SAL control group received 6 days of saline treatments from GD 17-22. Thus, the SAL, LAC, MAC and HAC dams had equal numbers of injections (6 consecutive treatment days with 2 injections/day). All females were handled identically in all other respects as well, including weighing, cage cleaning, etc.

2.2. ABR procedure

2.2.1. Offspring selection and numbers

For ABR testing, we selected 1 male and 1 female offspring per litter from the CON group when possible. To compensate for the smaller litter numbers in the other groups and to add stability to our data, we selected as many as 4 pups per litter and used equal number of males and females per litter when possible. Selecting males and females from each litter allowed the testing of sex-dependent differences. Other than choosing at least 1 male and 1 female offspring per litter when possible and limiting the number of offspring to 4 per litter, the offspring were randomly chosen for ABR testing.

Of the 23 CON litters, 22 litters had 1 male and 1 female offspring each and the remaining litter had 1male for a total of n=45 offspring that were ABR-tested. Of the 5 SAL litters, 3 litters had 2 males and 2 females, 1 litter had 1 male and 2 females, and another litter had 3 males and 1 female for a total of n=19 offspring tested. Of the 6 LAC litters, 5 litters had 2 males and 2 females, and 1 litter had 3 males for a total of n=23 offspring tested. Of the 8 MAC litters, 3 litters had 2 males and 2 females each, 2 litters had 1 male and 1 female each, 2 litters had 2 males each, and 1 litter had 3 males and 1 female for a total of n=24 offspring tested. From the 9 HAC litters, 4 litters had 2 males and 2 females each, 2 litters had 1 male and 1 female each, 2 litters had 2 males and 1 female each, and 1 litter had 1 male and 2 females for a total of n=29 offspring tested. Thus, a grand total of n=140 pups were ABR-tested of which 69 and 71 were males and females respectively. Within each litter the ABR, body temperature and body weight data on PND24 from all male and female littermates were averaged to produce a single male and a single female score to obviate problems associated with within-litter effects [43]. Because the data from 2 or more males (or females) per litter were averaged, the subsequent number of data points for statistical analyses of each PND24 outcome variables were as follows: CON had n=23 males and 22 females, SAL had n=5 males and 5 females, LAC had n=6 males and 5 females, MAC had n=6 males and 8 females, and HAC had 9 males and 9 females. Imbalances in the number of males and females within each litter were dictated by which offspring survived until the time of ABR testing. Pups were ABR-tested on PND 24 to simulate prior ABR developmental toxicology studies [16-18]. The rat ABR is well-developed by PND 24 [21].

2.2.2. ABR testing

Prior to ABR recording, each animal was given 100 mg/kg of the anesthetic ketamine (i.p.). Ketamine influences ABR latencies and amplitudes, but the effects are minor and the ABR quality is excellent [14]. Rectal temperature was monitored because temperature can influence the ABR [77] (Model 43TD, Yellow Springs Instruments Co., Yellow Springs, Ohio 45387, USA). A water-circulating heating pad was used to regulate and maintain normothermia by raising or lowering the temperature of the circulating water (Model TP500, Gaymar Industries, Orchard Park, New York 14127, USA). Regulating body temperature is important because body temperature can influence the ABR [90].

The ABR was differentially recorded between two subcutaneous platinum E-2 needle electrodes. The active electrode was inserted at the vertex, the reference electrode below the left ear, and the ground electrode below the right ear. Evoked potentials were collected by a Bio-logic Navigator (Bio-logic Corp., Mundelein, Illinois 60060, USA) and amplified 300,000 times with a digital bandpass of 300-3000 Hz. Electrode impedances ranged from 0-9 k′Ω. At least 256 responses were averaged. Recordings were made in an electrically shielded, double-walled sound attenuation chamber (Allotech, Inc., Raleigh, North Carolina 27603, USA). Binaural, „open field’ tone pips in the ascending order of 2000 Hz, 4000 Hz, 8000 Hz and 16000 Hz were delivered through a TDH-39P headphone positioned in front of the animal (rise/fall time = 0.5 ms, plateau = 10.0 ms, polarity = alternating, repetition rate = 19.0/sec, stimulus intensity = 15 to 100 dB peSPL). The tone pip frequencies of 2000 to 16000 Hz covered the range of greatest hearing sensitivity in the rat and permitted an assessment of frequency-dependent effects.

2.2.3. ABR latencies (neural transmission time)

The ABR is a series of action potentials and postsynaptic potentials. The rat ABR is composed of four components (labeled P1 to P4) occurring within 6 ms of stimulus onset [20,21]. Although the neurogenerators of the rat’s ABRs have not been determined, in the mouse they reflect neural activity chiefly from the auditory nerve (P1), the cochlear nucleus (P2), the superior olivary complex (P3), and the lateral lemniscus and/or inferior colliculus (P4) [41]. The latency of each ABR component was measured as the time from the computer’s triggering of the earphone to a wave’s positive peak, including a 0.3 ms acoustic transit time between the earphone and the animal’s pinnae. Two experimenters, who were „blind’ as to each animal’s treatment condition, scored the latencies of ABR waves P1, P2, P3 and P4. When scorers disagreed (rarely), the scores are averaged. The primary outcome variable was the P4 latency, a measure of neural transmission time along the auditory nerve and brainstem auditory pathway inclusively, in response to the 100 dB stimuli. The secondary outcomes were the P1 latency and the P1 to P4 interpeak latency (P1-P4 IPL) in response to the 100 dB stimuli. The P1 latency measures the auditory (peripheral) nerve’s transmission time and the P1- P4 IPL measures the brainstem (central) transmission time. These secondary outcome variables allowed us to determine if treatment effects on the P4 latency had peripheral and/or central origins [13,17].

2.2.4. ABR thresholds

ABR thresholds were determined by the method of limits [13,17]. Here, serial ABRs were gathered to a range of stimulus intensities starting at 100dB and then descending to 80, 60, 50, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, and 15 dB as the ABR threshold was reached and passed. To establish ABR threshold more precisely, 2 and 3 dB changes in stimulus intensity levels were tested around the ABR’s threshold (as determined by visual detection) and multiple ABR traces (2 to 5) were collected at each near-threshold intensity level to enhance scoring reliability. Threshold was defined as the lowest intensity to elicit a reliably scored ABR component. An experimenter, who was ‘blind’ as to each animal’s treatment condition, scored the ABR thresholds. A second experimenter then checked the threshold scoring for reliability purposes.

2.2.5. ABR latency-intensity profiles

An ABR latency-intensity (L-I) profile can help determine if a subject’s hearing loss is a conductive hearing loss (CHL) or a sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). A subject with a CHL would have an elevated ABR threshold and an L-I profile that is displaced upward and parallel to the normal curve. A subject with a SNHL will also have an elevated ABR threshold, however the P2 latencies will typically be normal or near normal in response to loud stimulus intensities but progressively curve upward from the normal range as the stimulus intensity decreases [13]. In rodents, one typically uses the ABR’s P2 wave to derive an animal’s latency-intensity (L-I) profile because the rodent’s P2 wave is the largest wave and usually the last wave to disappear as the sound stimulus decreases [13,17]. P2 latency was measured at this waveform’s positive peak.

2.2.6. ABR amplitude-intensity profiles

The amplitude of the P2 waveform was used as an index of the ABR’s maximum amplitude because the rodent’s P2 wave is the largest wave and the last wave to disappear as the sound intensity is decreased. P2 amplitude was measured from the positive peak of wave P2 to the subsequent negative trough (labeled N2). This was done at each stimulus intensity level in order to derive amplitude-intensity (A-I) profiles. Whereas the ABR amplitude is a function of neural synchrony and the number of neural units firing, the ABR amplitude can provide diagnostic information on these neural functions [26,71,89] and the presence of hyperacusis [15].

2.5. Data analysis

For the maternal variables, the individual dam was the unit of measure. For the offspring birth weights and postnatal mortality, the litter was the unit of measure. Treatment effects on these variables were analyzed by one-way analyses of variances (ANOVA), except that postnatal mortality was analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis Test. For the ABR outcome variables, each litter’s mean male and mean female data were the units of measure. Here, 3-way ANOVAs were used to assess the statistical significance of the Treatment, Sex, and Tone Pip Frequency factors. Tone Pip Frequency was a within-subject measure. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction for the statistical degrees of freedom (df values) was used for main effects and interactions involving this within-subject factor. Pup weights and core (rectal) temperatures were recorded at the time of ABR testing. These two outcome variables were analyzed by ANOVAs for Treatment and Sex, using each litter’s mean male and mean female data as the units of measure. If an ANOVA indicated a significant Treatment main effect or interaction, simple effects tests (univariate ANOVAs) and Bonferroni tests were used to make pairwise comparisons between treatment groups. The criterion for statistical significance was p≤0.05. We predicted that the HAC group would differ from the CON group but that the MAC group would not (see Introduction for rationale). There is very little evidence that a single AC course is harmful to the human or animal offspring, therefore we posited the null hypothesis for our LAC group. Even though rat pregnancy studies found adverse neurodevelopmental [27,39,40,53,79] and ABR effects [50] on offspring following maternal handling stress and saline injections, we did not specifically hypothesize that our SAL offspring would have abnormalities. We were however interested in comparing our LAC, MAC and HAC groups with the SAL group to assess the potential influence of maternal handling stress. To be conservative, two-sided probability levels were used when making pairwise comparisons between treatment groups.

3. Results

3.1. Maternal and offspring outcomes

All the data presented below come from viable litters only. The numbers of non-pregnant dams and non-viable litters were mentioned in Section 2.1.2.

The maternal and offspring variables are presented in Table 1. There were no significant group differences in gestational length, percent maternal weight gain during pregnancy, the number of pups per litter, or the number of live births per litter. By chance, the LAC dams weighed the least at the onset of pregnancy and consequently had less absolute maternal weight gain than the CON dams and consumed less food than the HAC dams. There was a Treatment group effect for average pup birth weight: F (4, 53)=9.00, p<0.001. Here, the HAC and MAC pups had significantly lower birth weights than their cohorts from the CON, SAL and LAC groups. In addition, the LAC group had lower birth weights than the CON and SAL groups. There was a Treatment effect for postnatal mortality between birth and PND 24, where the MAC and HAC pups had significantly higher postnatal mortality than their CON, SAL and LAC cohorts: Chi Square (4)=28.39, p<0.001.

Table 1.

Maternal and offspring outcomes as a function of Treatment Group (mean±SE)

| Treatment group

|

P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | SAL | LAC | MAC | HAC | ||

| Viable litters (n) | 23 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| Non-viable litters (n) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | |

| Gestation lengths (days) | 22.7±0.2 | 22.5±0.3 | 23.0±0.0 | 23.0±0.0 | 23.2±0.2 | NS |

| Maternal weight gains | ||||||

| GD 1 to GD 21 (g) | 138±9 | 132±41 | 92±6 a | 98±11 | 123±6 | 0.036 |

| Maternal weight gain percentages | ||||||

| GD 1 to GD 21 (%) | 44±3 | 36±8 | 36±4 | 35±5 | 33±4 | NS |

| Maternal food consumptions | ||||||

| GD 1 to GD 21 (g) | 505±16 | 544±53 | 391±21 b | 447±25 | 548±25 | 0.002 |

| Litter sizes (# pups/litter) | 14.6±0.9 | 13.7±1.4 | 11.0±1.1 | 13.7±0.4 | 14.3±0.8 | NS |

| Live births (# pups/litter) | 14.4±1.0 | 13.3±1.2 | 11.0±1.1 | 11.3±1.5 | 11.0±1.5 | NS |

| Pup birth weights (g) | 6.7±0.2 | 6.6±0.3 | 5.7±0.1 a | 4.9±0.3 c | 5.6±0.2 c | <0.001 |

| Postnatal deaths (%) | 2.3 | 2.5 | 6.5 | 36.6 c | 36.1 c | <0.001 |

| Male PND24 weight (g) | 65.3±1.8 | 61.9±3.8 | 50.0±3.4 d | 44.0±3.4 d | 44.9±2.8 d | <0.001 |

| Female PND24 weight (g) | 61.3±1.8 | 58.7±3.8 | 48.3±3.8 d | 40.6±3.0 d | 43.0 ±2.8 d | <0.001 |

| Temp. during ABR (°C) | 37.1±0.1 | 37.0±0.1 | 37.3±0.1 | 37.0±0.1 | 37.0±0.1 | NS |

SE=standard error, CON=untreated control, SAL=saline control, LAC=low antenatal corticosteroid regimen, MAC=moderate antenatal corticosteroid regimen, HAC=high antenatal corticosteroid regimen, NS=not significant, GD=gestation day, PND=postnatal day

Different from CON group, p≤0.05

Different from HAC group, p≤0.05

Different from CON, SAL and LAC groups, p≤0.02

Different from CON and SAL groups, p≤0.01

There were no Treatment group differences in rectal temperature during the ABR test session on PND 24: F (4, 88)=0.79, p=0.533. For offspring weights on PND 24, there was a significant effect for Group but not for Sex or their interaction: F (4, 88)=28.75, p<0.001; F (1, 88)=2.06, p=0.16; and F(4, 88)=0.07, p=0.99, respectively. Simple effects tests and pairwise comparisons indicated that the HAC, MAC and LAC offspring weighed significantly less than their CON and SAL cohorts on PND24.

3.2. ABR latencies (neural transmission time)

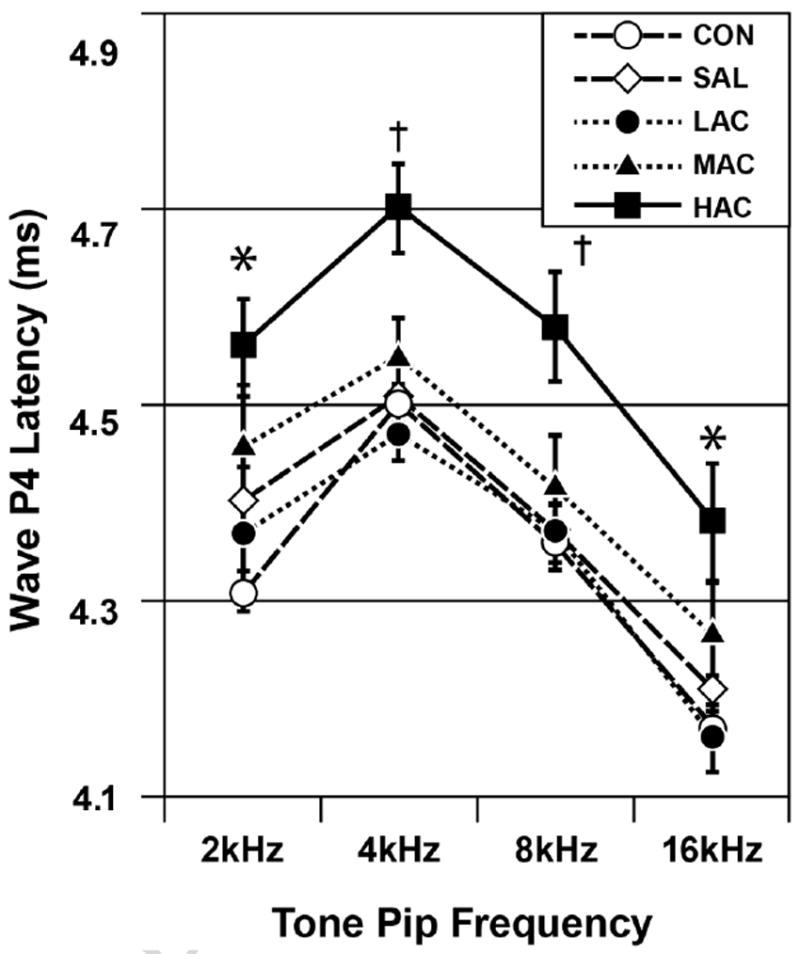

Fig. 1 shows P4 latency as functions of Treatment Group and Tone Pip Frequency. The ANOVA indicated a significant Treatment effect: F (4, 88=9.09, p<0.001. Fig. 1 shows a dose-dependent response pattern in that the HAC offspring had the longest (slowest) P4 latencies, followed by the MAC offspring. The CON, SAL and LAC offspring had the shortest (fastest) P4 latencies. Simple effects tests and pairwise comparisons indicated that the HAC group differed from the LAC, SAL and CON groups at each of the Tone Pip Frequency conditions and from the MAC group at the 4 and 8 kHz frequency conditions. The MAC, LAC, SAL and CON groups did not differ from each other. There was a significant Tone Pip Frequency effect, indicating that P4 latency varied across the four levels of this variable: F (3, 205)=166.27, p<0.001. There was no significant main effect for Sex (p=0.334) and all interactions with either Sex or Frequency were non-significant (p≥0.255).

Fig. 1.

ABR P4 latencies as functions of treatment group and tone pip frequency (mean±SE). Group differences (p<0.05): * HAC>LAC, SAL and CON but not MAC, MAC=LAC=SAL=CON; † HAC>all others, MAC=LAC=SAL=CON. HAC=high antenatal corticosteroid, MAC=moderate antenatal corticosteroid, LAC=low antenatal corticosteroid, SAL=saline control, CON=untreated control. Stimulus intensity=100 dB.

Similar results were seen with the secondary latency variables. For P1 latency, there was a significant Treatment effect: F (4, 88)=3.76, p=0.007. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the HAC group had significantly longer P1 latencies (mean±SE=1.58±0.01 ms) than the SAL group (1.53±0. ms). The MAC, LAC and CON groups did not differ from any group (1.56±0.01, 1.55±0.01 and 1.55±0.01 ms). These P1 latency values were derived from combining the results from the 4 different tone pip conditions. There was a significant Treatment-by-Frequency interaction due to a slightly stronger treatment effect during the 4kHz tone pip condition: F (3, 219)=2.01, p=0.033.

For the P1-P4 IPL, there was a significant Treatment effect: F (4, 88)=9.93, p<0.001. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the HAC group had significantly longer IPLs (mean±SE=2.97±0.03 ms) than the MAC, LAC, SAL and CON groups (2.86±0.03, 2.80±0.03, 2.84±0.03 and 2.79±0.2 ms). These latter 4 groups did not differ from each other. The above IPL values were derived from combining the results from the 4 different tone pip conditions. Fig. 2 illustrates the effects of the HAC condition on the ABRs of individual animals. The HAC animals had prolongations of the various ABR waves which sometimes occurred as early as the P1 wave and became progressively greater with each successive wave.

Fig. 2.

ABRs from the CON pups had normal results, whereas several rat pups in the HAC group had abnormal prolongations of one or more ABR waves (age = day 24). Dotted lines represent the expected position of each wave based on the CON group means. Arrowheads identify abnormally prolonged waves, defined as ≥2SD longer than the CON group means. Stimuli=16 kHz tone pips at 100 dB.

3.3. ABR thresholds

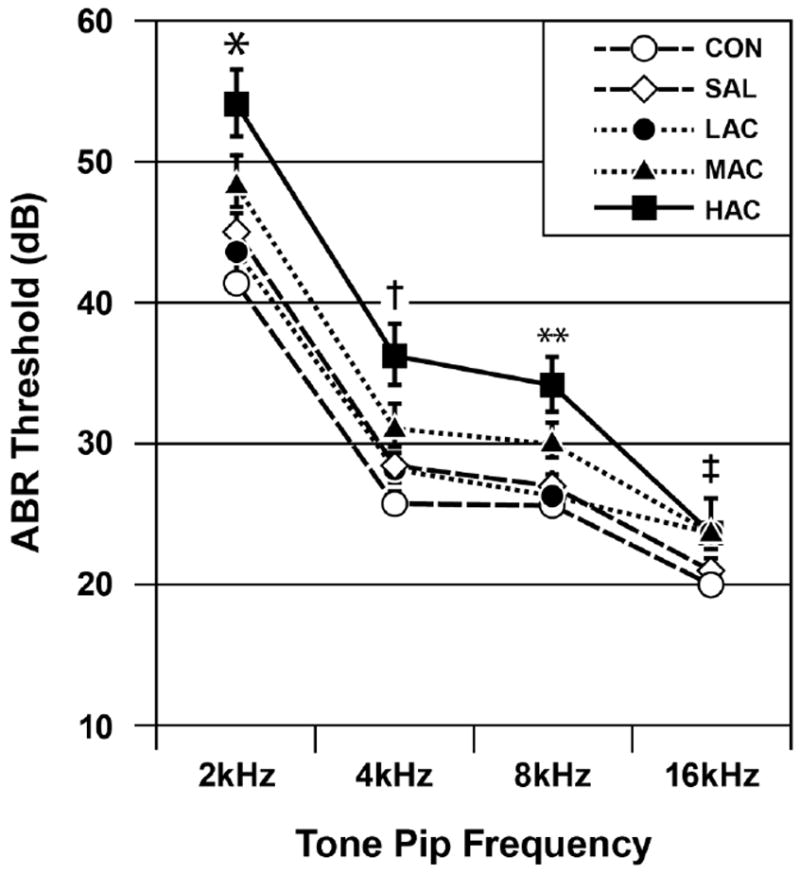

There was a significant Treatment effect on ABR thresholds: F (4, 88)=22.26, p<0.001. Fig. 3 shows a dose-dependent pattern in that the HAC offspring had the highest (poorest) ABR thresholds, followed by the MAC offspring. The CON offspring had the lowest (best) thresholds. The SAL and LAC offspring had thresholds that were intermediate between the CON and MAC offspring. There was a significant Treatment-by-Frequency interaction, indicating that treatment group differences were greatest during the 2 to 8 kHz conditions (lower tone pip frequencies): F(12, 210)=4.61, p<0.001. Simple effects tests and pairwise comparisons indicated that the HAC group typically differed from all other groups and MAC always differed from the CON group and sometimes differed from the LAC and SAL groups. The CON, SAL and LAC groups did not differ from each other, except during the 16 kHz tone pip condition where LAC differed from the CON group. Fig. 3 identifies the significant group differences at each tone pip frequency. There was a significant Tone Pip Frequency effect, indicating that ABR thresholds were progressively lower (better) as the tone pip frequency progressed from 2 to 16 kHz: F (3, 210)=707.74, p<0.001. There was no significant main effect or interaction with the Sex variable (p≥0.778).

Fig. 3.

ABR thresholds as functions of treatment group and tone pip frequency (mean±SE). Group differences (p<0.05): *HAC>all others, MAC>CON and LAC, LAC=SAL=CON; †HAC>all others, MAC>CON, LAC=SAL=CON; **HAC>all others, MAC>LAC, SAL and CON, LAC=SAL=CON; ‡HAC>SAL and CON, MAC=LAC>CON, SAL=CON.

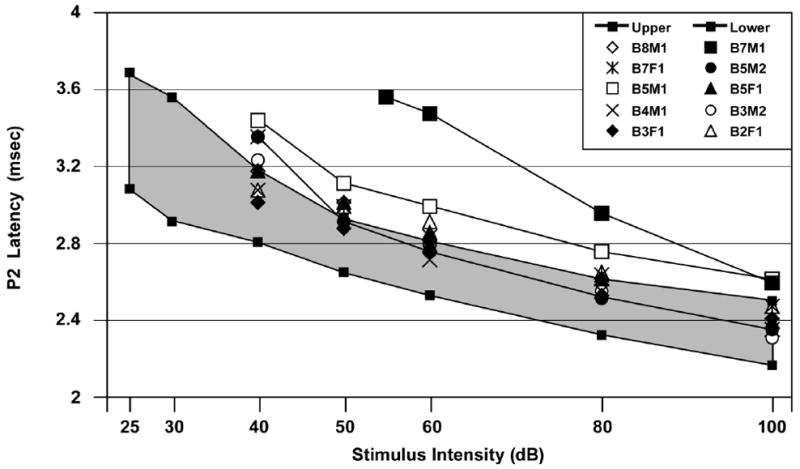

3.4. ABR latency-intensity (L-I) profiles

The L-I profile can help diagnose whether a subject’s hearing loss is either CHL or SNHL (see Methods section). Within any given litter, there can be individual differences in L-I profiles. One littermate, for example, might have a normal profile while other littermates might have profiles diagnostic of CHL or SNHL. Combining such diverse L-I profiles to produce a litter average would obscure the diagnostic differences. Thus, L-I profiles were analyzed for each individual.

Fig. 4 shows the L-I profiles in response to the 8 kHz tone pip condition for the 10 of 29 HAC animals (34.5%) having significantly elevated ABR thresholds. An abnormal elevation in the ABR threshold was defined as being ≥3 standard deviations (SD) above the CON control group mean [13,16-18]. The shaded region in Fig. 4 represents the normal range derived from Control data. Fig. 4 shows that the L-I profile from 3 of these 10 HAC offspring fell outside the normal range. Of these 3 IPL profiles, 2 were generally similar to the L-I profile that is diagnostic of SNHL and 1 was similar to the L-I profile that is diagnostic of CHL. The remaining 7 HAC offspring depicted in Fig. 4 had abnormally elevated ABR thresholds but their L-I profiles fell within the upper normal range. For these same 10 HAC animals, results from the other tone pip conditions (not shown) were highly similar. For the MAC group, 3 of the 24 animals (12.5%) had significantly elevated ABR threshold and all 3 had L-I profiles consistent with SNHL (not shown). For the LAC group, 1 of 23 animals (4.3%) had L-I profiles consistent with SNHL (not shown). None of the CON or SAL animals (0%) had elevated ABR thresholds. Using the above data with the individual animal as the unit of measure, the treatment group difference in elevated ABR thresholds at 8 kHz was significant: Chi Square (4)=27.4, p<0.001. Using litter as the unit of measure, the CON, SAL, LAC, MAC and HAC groups had respectively 0.0, 0.0, 16.7, 25.0 and 55.6% of litters with at least 1 offspring having an abnormally elevated ABR threshold at 8 kHz: Chi Square (4)=16.6, p=0.002.

Fig. 4.

ABR P2 latency-intensity (L-I) profiles of the 10 HAC offspring with elevated ABR thresholds. Two HAC offspring (B7M1 and B5M2) had P2 L-I profiles suggestive of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and 1 (B5M1) had a P2 L-I profile suggestive of conductive hearing loss (CHL). The remaining 7 animals with elevated ABR thresholds had P2 latencies that bordered the upper normal range and with no ABRs below 40 dB. The shaded region is the normal range. Stimuli=8 kHz tone pips.

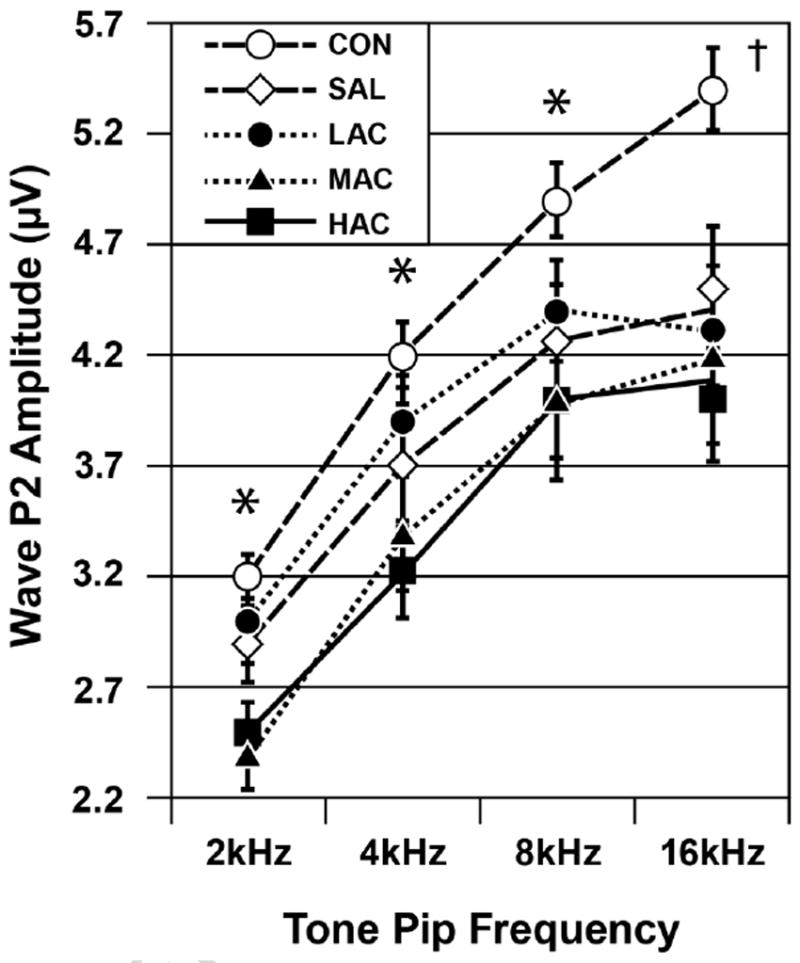

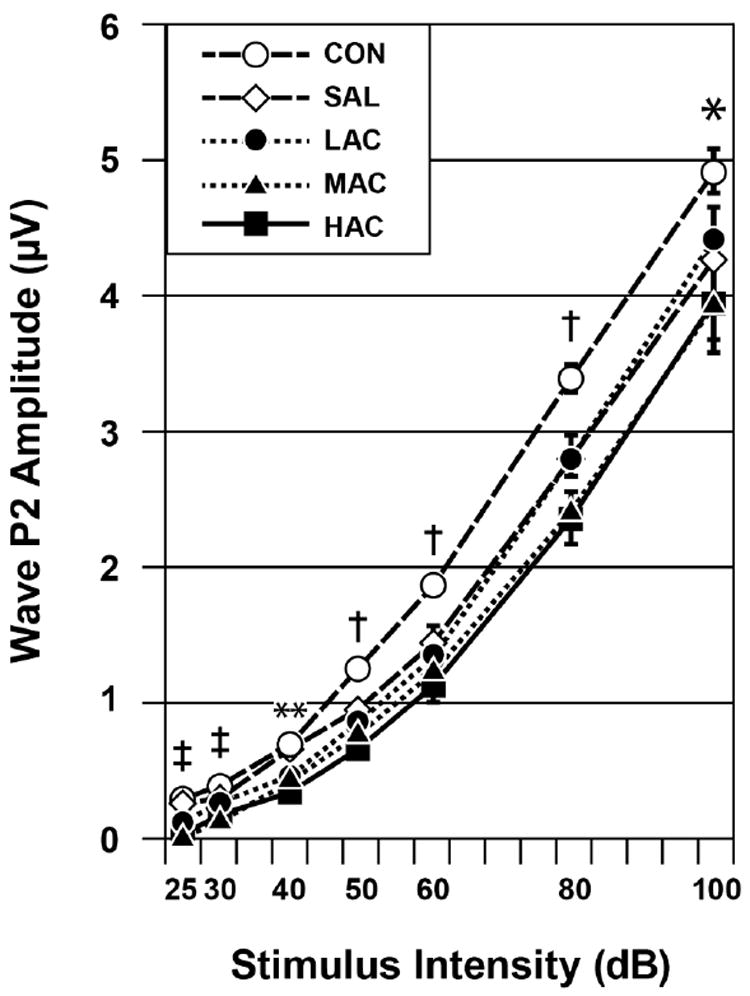

3.5. ABR amplitudes and amplitude-intensity (A-I) profiles

The HAC and MAC groups had elevated ABR thresholds with only some of the offspring exhibiting SNHL-like or CHL-like patterns in their L-I profiles. This suggested that the remaining animals with elevated ABR thresholds had primarily small amplitude ABRs. To investigate this possibility, we measured the ABR’s P2 amplitude. This waveform was chosen as an index of the ABR’s amplitude for reasons described in the Methods section. An ANOVA done on P2 amplitudes elicited by the highest stimulus intensity (see Fig. 5) showed a significant Treatment effect, chiefly caused by the HAC and MAC groups having smaller ABR amplitudes than the CON group: F (4, 88)=5.70, p<0.001. There were also significant effects for Frequency caused by progressively larger P2 amplitudes in response to higher tone pip frequencies: F (3, 170)=189.30, p<0.001. There was a significant Treatment-by-Frequency interaction caused by stronger Treatment effects in response to the 16 kHz tone pip condition: F (12, 170)=2.59, p=0.012. There was no significant main effect for Sex or for its interactions with Treatment and Frequency (p≥0.43). The A-I profiles for P2 amplitudes during the 8 kHz condition showed that these treatment-induced amplitude decreases occurred throughout the range of stimulus intensities (see Fig. 6). Similar effects occurred in response to the 2, 4 and 16 kHz tone pip conditions (not shown).

Fig. 5.

ABR P2 amplitudes as functions of treatment group and tone pip frequency (mean±SE). Group differences (p<0.05): *HAC and MAC<CON, LAC=SAL=CON; †HAC=MAC=LAC=SAL<CON. Stimulus intensity=100 dB.

Fig. 6.

ABR P2 amplitude-intensity (A-I) profiles (mean±SE). HAC and MAC treatments caused decreased P2 amplitudes. Group differences (p<0.05): *HAC and MAC<CON, HAC<SAL; †HAC=MAC=LAC=SAL<CON; **HAC=MAC=LAC<CON and SAL; ‡HAC=MAC<CON, SAL and LAC. Stimuli=8 kHz tone pips.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects on offspring outcome

We found that repeated antenatal corticosteroid treatments (Betamethasone) had harmful effects on offspring birth weight, postnatal mortality, postnatal growth as well as sensory and neural function in an animal (rat) model. The adverse effects on sensory and neural function were evidenced by two basic findings in the auditory brainstem response collected at the postnatal age of 24 days. First, prolonged ABR latencies in the HAC reflected prolonged neural transmission along both the auditory (peripheral) nerve and brainstem (central) auditory pathway, likely due to impaired myelination and neural growth. The prolongation in neural transmission times became progressively greater as the neural information ascended each successive station along the brainstem auditory pathway, indicating a cumulative effect. Interestingly, prolonged neural transmission times are found in some schizophrenia [49,60] and autism patients [36,55,62,76,91,92]; and prenatal exposure to excess glucocorticoids is a risk factor for such psychiatric disorders [7,52,64,85,98]. Second, the elevated ABR thresholds and reduced ABR amplitudes in the HAC and MAC groups reflected poor auditory sensitivity probably due to impaired neural development, poor neural synchrony, or permanent neural damage. The HAC and MAC offspring also had decreased birth and growth weights and increased postnatal mortality. In contrast, there were no significant treatment effects on maternal weight gain and food consumption, gestation length, litter size and number of live births in the HAC and MAC groups.

Of the HAC and MAC offspring with elevated ABR thresholds, about half of them had L-I profiles consistent with sensorineural hearing losses. The HAC and MAC offspring with L-I profiles suggestive of sensorineural hearing loss could have permanent cochlear (inner ear) damage or just a severe maturational delay in cochlear development. The remaining animals with elevated ABR thresholds had ABRs chiefly characterized by small amplitudes and borderline prolonged latencies. ABR amplitudes are dependent on the number of neural units firing and their neural synchrony [26,71,89]. Thus, we conclude that these latter HAC and MAC offspring had impaired neural development and/or poor neural synchrony. Such neural abnormalities can cause auditory processing disorders (APD) [22,89]. Future studies should follow such offspring to see if these disorders persist into adulthood and can be confirmed by histology and behavior.

The current study as well as several previous studies found that glucocorticoid overexposure during the last gestational week had adverse effects on auditory function in the rat offspring [11,44,50]. In contrast, several human studies did not find significant effects on the neonatal ABR [4,5,19] or other hearing tests [38,56]. There are several possible explanations for these differences. First, the majority of the infants in these human studies were exposed to low or moderate amounts of antenatal corticosteroids. Such lower exposures may have little no effects on the ABR. Second, it is possible that the rat fetus is more sensitive to glucocorticoid treatments than the human fetus. A recent review article noted that some human antenatal corticosteroid studies were reporting smaller effects than corresponding animal studies, suggesting that the animal models were more sensitive to such treatments [67]. Consistent with this notion, the high postnatal mortality rates in our MAC and HAC groups suggest increased sensitivity. We recommend therefore that future animal studies consider lower levels of Betamethasone exposure. Third, there were limitations to the human studies in that they did not assess ABR thresholds, the ABR’s L-I and A-I profiles, nor ABRs in response to differing tone pip frequencies to assess high frequency hearing loss, and were compromised by marginal statistical power [19]. ABR thresholds proved to be a more sensitive measure of repeated AC’s harmful effects than neurotransmission time in that both our MAC and HAC offspring showed significant effects on the former parameter whereas only the HAC offspring had prolonged neurotransmission times. The absence of ABR threshold assessment in the infant studies was a shortcoming to which future animal and human studies should pay heed.

We hypothesized that adverse effects would be seen in our HAC group, but not in the MAC group. Contrary to this specific hypothesis, our MAC group had a variety of adverse outcomes. We were not entirely successful in finding a threshold level for the adverse effects of antenatal Betamethasone on the ABR. Clearly, this threshold is lower than 3 AC courses. Whether 1 or 2 AC courses have some short- or long-term adverse consequences remains largely unexplored. Future studies should address this gap in knowledge.

We did not have a specific prediction concerning the LAC group. This group had lower maternal weight gain and food consumption and lower pup birth and growth weights. By chance, lower weight dams were randomly assigned to the LAC group. We feel this is why this group had different outcomes on the above variables. The LAC pups had a normal postnatal mortality rate. The LAC pups had normal ABR wave latencies, indicating adequate maturity of these neural parameters. They also had only sparse and mild effects on their ABR thresholds and amplitudes. So the LAC pups had ostensibly normal ABRs despite being relatively underweight at the time of the ABR recordings. This suggests that the abnormal ABRs in the HAC and MAC groups were not secondary to growth retardation but rather the result of direct effects on the nervous system. In our human infant study on the effects of repeated courses of AC, we similarly found that there was no relation between infant weights and ABR wave latencies or amplitudes [19]. Also similar to our results with the LAC group, another study found no adverse effects from a single Betamethasone course given to rat pups on postnatal day 1 [100].

We did not have a specific prediction concerning the SAL control group. Their maternal and birthing outcomes, postnatal mortality rate, PND 24 body weights and ABR outcomes were normal. A recent study that found higher ABR thresholds to low frequency tone pips in rats prenatally exposed to the stressors of maternal handling and saline injections [50]; however one study could not confirm this finding [46]. Our SAL results did not have adequate statistical power to confirm nor refute that maternal handling stress can influence the offspring’s ABRs. A larger scale study will be necessary to determine this issue definitively. The MAC and HAC groups differed significantly from the SAL group on birth and PND 24 weights, and postnatal mortality; and the HAC differed significantly from the SAL group on ABR neural transmission times and thresholds. These differences indicate that the repeated AC treatments had effects beyond those caused by maternal handling stress alone.

All of the ABR outcome measures failed to show significant sex-dependent effects, indicating that there were no male-female differences in the ABR outcomes when examined at the PND 24 time period. Male-female ABR differences can appear in older animals however [20]. There were no significant treatment group differences in rectal temperature during the ABR recording sessions, eliminating this as a possible confounding variable in our ABR results [90].

4.2. Mechanisms

There are several possible mechanisms for the harmful effects of prenatal Betamethasone on the offspring: (A) The reprogramming or long-term activation of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the cochlea and other auditory-related structures by elevated fetal glucocorticoids might underlie some of the harm to the auditory system [12,44]. (B) The oxidative stress caused by excessive fetal or neonatal exposure to AC has been implicated in damage to the cochlea [11] and brain [10]. (C) Excessive fetal or neonatal AC exposure causes adverse effects on the nervous system which include the inhibition of neural growth and myelination [6,23,29,58,63,73,74,93], the inhibition of cell division and DNA synthesis [47], epigenetic modifications [51,85], cell death [47], decreased cerebral blood flow [63] and “steroid diabetes” with all its negative sequelae for sensory and neurological morbidities [68,72,84,85].

4.3. Conclusions, clinical implications, and future directions

A single course of AC confers great benefit by reducing the incidence and severity of respiratory distress syndrome, chronic pulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, intracranial hemorrhages and death. Despite these benefits, there is increasing concern that excessive or repeated exposure to AC can cause harm in regards to sensory, neurodevelopmental and growth disorders in the young offspring. There is also increasing evidence that such overexposure can cause a variety of health disorders in adulthood [11,28,44,50,94].

Our study was particularly interested in the effects of 3 AC courses because this amount was recently given in about 85% of preterm cases [75] and was considered safe [96]. Our results indicate that this regimen may not be safe. Future studies should fill the gaps in knowledge concerning how much AC treatment is too much, further characterize the nature of the nervous system effects, and document the life-long effects in accord with the Barker Hypothesis concerning the fetal programming of adult-onset diseases [7,67,85].

Our study evaluated 1, 3 and 6 AC courses. There is growing clinical interest in using an initial AC course followed by a “rescue” course. Such a treatment regimen needs to be studied in animal models to fully ascertain the short- and long-term benefit and harm of this AC regimen before further human experimentation is conducted. We did not assess critical periods of exposure, maternal and fetal glucocorticoid levels, maternal lactation parameters, surrogate or cross-fostering, adult offspring diabetes, hypertension, cochlear histopathology, life span, internal organ pathology, neurobehavioral and epigenetic modifications. These would be important outcome measures for future studies.

Another issue for future study concerns the critical periods of exposure. In our Methods section, we provided rationale for giving AC during the last week of gestation in the rat. In addition, AC is given to the rat during this gestational period because lung and other internal organ development in the rat at birth is comparable to and even more mature than the premature human infant [80,81]. However, it can be argued that giving glucocorticoid treatments postnatally to rats would likewise be appropriate because rat brain development during the first 1-2 postnatal weeks more closely mimics the human fetus’s brain development at 23-32 weeks gestation when AC is typically given [34]. The drawbacks to this latter approach include bypassing the maternal compartment by giving the glucocorticoid treatments directly to the rat offspring and the increased mortality and possible maternal rejection associated with giving glucocorticoid treatments to neonatal rats [10,42]. A solution to this dilemma would be for future rat studies to compare the effects of glucocorticoid treatments given during the 3 critical periods of the last gestational week and the first 2 postnatal weeks.

Highlights.

Antenatal corticosteroids (AC) reduce the risks of infant morbidity and mortality

There is no accepted regimen on how frequently AC should be given

Our results found that 3 or more AC treatments was harmful in a rat model

Such results should be considered when weighing the benefit and harm of repeated AC

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from Wayne State University’s Undergraduate Student Research Program (awarded to B.R.A.) and Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate (awarded to M.W.C. and J.I.A.) and the National Institutes of Health (GM58905-8), neither of which had a conflict of interest with the current study and neither of which contributed to the design, analysis or writing of this study. We thank Aliya Ali, Faith Laja and Janelle Sherman for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement There were no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids for preterm birth study (MACS) NIH Clinical Trial NCT00187382. http://clinicaltrialsgov/ct2/show/NCT00187382 (Retrieved from website on September 25, 2006)

- 2.NIH Consensus Development Panel on the Effect of Corticosteroids for Fetal Maturation on Perinatal Outcomes. Effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273:413–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290065031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A randomized trial comparing the impact of one versus two courses of ACS on neonatal outcome. NIH Clinical Trial NCT00201643. 2006 http://clinicaltrialsgov/ct2/show/NCT00201643 (Retrieved from website on September 25)

- 4.Amin SB, Guillet R. Auditory neural maturation after exposure to multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone in premature infants as evaluated by auditory brainstem response. Pediatrics. 2007;119:502–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amin SB, Orlando MS, Dalzell LE, Merle KS, Guillet R. Brainstem maturation after antenatal steroids exposure in premature infants as evaluated by auditory brainstem-evoked response. J Perinatol. 2003;23:307–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonow-Schlorke I, Muller T, Brodhun M, Wicher C, Schubert H, Nathanielsz PW, Witte OW, Schwab M. Betamethasone-related acute alterations of microtubule-associated proteins in the fetal sheep brain are reversible and independent of age during the last one-third of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:553 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.10.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2004;93:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrington KJ. The adverse neuro-developmental effects of postnatal steroids in the preterm infant: a systematic review of RCTs. BMC Pediatr. 2001;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burlet G, Fernette B, Blanchard S, Angel E, Tankosic P, Maccari S, Burlet A. Antenatal glucocorticoids blunt the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of neonates and disturb some behaviors in juveniles. Neuroscience. 2005;133:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camm EJ, Tijsseling D, Richter HG, Adler A, Hansell JA, Derks JB, Cross CM, Giussani DA. Oxidative stress in the developing brain: effects of postnatal glucocorticoid therapy and antioxidants in the rat. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canlon B, Erichsen S, Nemlander E, Chen M, Hossain A, Celsi G, Ceccatelli S. Alterations in the intrauterine environment by glucocorticoids modifies the developmental programme of the auditory system. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2035–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canlon B, Meltser I, Johansson P, Tahera Y. Glucocorticoid receptors modulate auditory sensitivity to acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 2007;226:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church MW, Blakley BW, Burgio DL, Gupta AK. WR-2721 (Amifostine) ameliorates cisplatin-induced hearing loss but causes neurotoxicity in hamsters: dose-dependent effects. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2004;5:227–37. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-4011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Church MW, Gritzke R. Effects of ketamine anesthesia on the rat brain-stem auditory evoked potential as a function of dose and stimulus intensity. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1987;67:570–83. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Church MW, Jen KL, Anumba JI, Jackson DA, Adams BR, Hotra JW. Excess omega-3 fatty acid consumption by mothers during pregnancy and lactation caused shorter life span and abnormal ABRs in old adult offspring. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 32:171–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Church MW, Jen KLC, Dowhan LM, Adams BR, Hotra JW. Excess and deficient omega-3 fatty acid during pregnancy and lactation cause impaired neural transmission in rat pups. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Church MW, Jen KLC, Jackson DA, Adams BR, Hotra JW. Abnormal neurological responses in young adult offspring caused by excess omega-3 fatty acid (fish oil) consumption by the mother during pregnancy and lactation. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Church MW, Jen KLC, Stafferton T, Hotra JW, Adams BR. Reduced auditory acuity in rat pups from excess and deficient omega-3 fatty acid consumption by the mother. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Church MW, Wapner RJ, Mele L, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, Peaceman AM, Moawad AH, O’Sullivan MJ, Miodovnik M, et al. Miodovnik and others, Repeated courses of antenatal corticosteroids: Are there effects on the infant’s auditory brainstem responses? Neurotoxicol Teratol in press. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Church MW, Williams HL, Holloway JA. Brain-stem auditory evoked potentials in the rat: effects of gender, stimulus characteristics and ethanol sedation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;59:328–39. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(84)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Church MW, Williams HL, Holloway JA. Postnatal development of the brainstem auditory evoked potential and far-field cochlear microphonic in non-sedated rat pups. Brain Res. 1984;316:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cone-Wesson B. Prenatal alcohol and cocaine exposure: influences on cognition, speech, language, and hearing. J Commun Disord. 2005;38:279–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotterrell M, Balazs R, Johnson AL. Effects of corticosteroids on the biochemical maturation of rat brain: postnatal cell formation. J Neurochem. 1972;19:2151–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb05124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowley PA. Antenatal corticosteroid therapy: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials, 1972 to 1994. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:322–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowther CA, Doyle LW, Haslam RR, Hiller JE, Harding JE, Robinson JS. Outcomes at 2 years of age after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1179–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis H. Brain stem and other responses in electric response audiometry. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85:3–14. doi: 10.1177/000348947608500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickerson PA, Lally BE, Gunnel E, Birkle DL, Salm AK. Early emergence of increased fearful behavior in prenatally stressed rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:586–93. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drake AJ, Tang JI, Nyirenda MJ. Mechanisms underlying the role of glucocorticoids in the early life programming of adult disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:219–32. doi: 10.1042/CS20070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunlop SA, Archer MA, Quinlivan JA, Beazley LD, Newnham JP. Repeated prenatal corticosteroids delay myelination in the ovine central nervous system. J Matern Fetal Med. 1997;6:309–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199711/12)6:6<309::AID-MFM1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunn E, Kapoor A, Leen J, Matthews SG. Prenatal synthetic glucocorticoid exposure alters hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation and pregnancy outcomes in mature female guinea pigs. J Physiol. 2010;588:887–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.182139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elimian A, Verma U, Visintainer P, Tejani N. Effectiveness of multidose antenatal steroids. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:34–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erichsen S, Bagger-Sjoback D, Curtis L, Zuo J, Rarey K, Hultcrantz M. Appearance of glucocorticoid receptors in the inner ear of the mouse during development. Acta Otolaryngol. 1996;116:721–5. doi: 10.3109/00016489609137913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson SA, Paule MG, Holson RR. Neonatal dexamethasone on day 7 in rats causes behavioral alterations reflective of hippocampal, but not cerebellar, deficits. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finlay BL, Darlington RB. Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science. 1995;268:1578–84. doi: 10.1126/science.7777856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.French NP, Hagan R, Evans SF, Godfrey M, Newnham JP. Repeated antenatal corticosteroids: size at birth and subsequent development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:114–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujikawa-Brooks S, Isenberg AL, Osann K, Spence MA, Gage NM. The effect of rate stress on the auditory brainstem response in autism: a preliminary report. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:129–40. doi: 10.3109/14992020903289790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasbargen U, Reber D, Versmold H, Schulze A. Growth and development of children to 4 years of age after repeated antenatal steroid administration. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:552–5. doi: 10.1007/s004310100804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauser J, Dettling-Artho A, Pilloud S, Maier C, Knapman A, Feldon J, Pryce CR. Effects of prenatal dexamethasone treatment on postnatal physical, endocrine, and social development in the common marmoset monkey. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1813–22. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauser J, Feldon J, Pryce CR. Prenatal dexamethasone exposure, postnatal development, and adulthood prepulse inhibition and latent inhibition in Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry KR. Auditory brainstem volume-conducted responses: origins in the laboratory mouse. J Am Aud Soc. 1979;4:173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herrera EA, Verkerk MM, Derks JB, Giussani DA. Antioxidant treatment alters peripheral vascular dysfunction induced by postnatal glucocorticoid therapy in rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holson RR, Freshwater L, Maurissen JP, Moser VC, Phang W. Statistical issues and techniques appropriate for developmental neurotoxicity testing: a report from the ILSI Research Foundation/Risk Science Institute expert working group on neurodevelopmental endpoints. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:326–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hossain A, Hajman K, Charitidi K, Erhardt S, Zimmermann U, Knipper M, Canlon B. Prenatal dexamethasone impairs behavior and the activation of the BDNF exon IV promoter in the paraventricular nucleus in adult offspring. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6356–65. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hougaard KS, Andersen MB, Kjaer SL, Hansen AM, Werge T, Lund SP. Prenatal stress may increase vulnerability to life events: comparison with the effects of prenatal dexamethasone. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;159:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hougaard KS, Barrenas ML, Kristiansen GB, Lund SP. No evidence for enhanced noise induced hearing loss after prenatal stress or dexamethasone. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:613–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Howard E, Benjamins JA. DNA, ganglioside and sulfatide in brains of rats given corticosterone in infancy, with an estimate of cell loss during development. Brain Res. 1975;92:73–87. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang WL, Beazley LD, Quinlivan JA, Evans SF, Newnham JP, Dunlop SA. Effect of corticosteroids on brain growth in fetal sheep. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:213–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igata M, Ohta M, Hayashida Y, Abe K. Normalization of auditory brainstem responses resulting from improved clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1995;16:81–2. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kadner A, Pressimone VJ, Lally BE, Salm AK, Berrebi AS. Low-frequency hearing loss in prenatally stressed rats. Neuroreport. 2006;17:635–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200604240-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kapoor A, Petropoulos S, Matthews SG. Fetal programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function and behavior by synthetic glucocorticoids. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:586–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kinney DK, Munir KM, Crowley DJ, Miller AM. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koenig JI, Elmer GI, Shepard PD, Lee PR, Mayo C, Joy B, Hercher E, Brady DL. Prenatal exposure to a repeated variable stress paradigm elicits behavioral and neuroendocrinological changes in the adult offspring: potential relevance to schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2005;156:251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kutzler MA, Ruane EK, Coksaygan T, Vincent SE, Nathanielsz PW. Effects of three courses of maternally administered dexamethasone at 0.7, 0.75, and 0.8 of gestation on prenatal and postnatal growth in sheep. Pediatrics. 2004;113:313–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwon S, Kim J, Choe BH, Ko C, Park S. Electrophysiologic assessment of central auditory processing by auditory brainstem responses in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:656–9. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.4.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee BH, Stoll BJ, McDonald SA, Higgins RD. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants exposed prenatally to dexamethasone versus betamethasone. Pediatrics. 2008;121:289–96. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LeFlore JL, Salhab WA, Broyles RS, Engle WD. Association of antenatal and postnatal dexamethasone exposure with outcomes in extremely low birth weight neonates. Pediatrics. 2002;110:275–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levitt NS, Lindsay RS, Holmes MC, Seckl JR. Dexamethasone in the last week of pregnancy attenuates hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor gene expression and elevates blood pressure in the adult offspring in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64:412–8. doi: 10.1159/000127146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liggins GC, Howie RN. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics. 1972;50:515–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindstrom LH, Wieselgren IM, Klockhoff I, Svedberg A. Relationship between abnormal brainstem auditory-evoked potentials and subnormal CSF levels of HVA and 5-HIAA in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;28:435–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90411-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maccari S, Piazza PV, Kabbaj M, Barbazanges A, Simon H, Le Moal M. Adoption reverses the long-term impairment in glucocorticoid feedback induced by prenatal stress. J Neurosci. 1995;15:110–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00110.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maziade M, Merette C, Cayer M, Roy MA, Szatmari P, Cote R, Thivierge J. Prolongation of brainstem auditory-evoked responses in autistic probands and their unaffected relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1077–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCallum J, Smith N, MacLachlan JN, Coksaygan T, Schwab M, Nathanielsz P, Richardson BS. Effects of antenatal glucocorticoids on cerebral protein synthesis in the preterm ovine fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:103 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meyer U, Feldon J. Epidemiology-driven neurodevelopmental animal models of schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;90:285–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Modi N, Lewis H, Al-Naqeeb N, Ajayi-Obe M, Dore CJ, Rutherford M. The effects of repeated antenatal glucocorticoid therapy on the developing brain. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:581–5. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murphy BP, Inder TE, Huppi PS, Warfield S, Zientara GP, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Volpe JJ. Impaired cerebral cortical gray matter growth after treatment with dexamethasone for neonatal chronic lung disease. Pediatrics. 2001;107:217–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Should we be prescribing repeated courses of antenatal corticosteroids? Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nyirenda MJ, Welberg LA, Seckl JR. Programming hyperglycaemia in the rat through prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids-fetal effect or maternal influence? J Endocrinol. 2001;170:653–60. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parikh NA, Lasky RE, Kennedy KA, Moya FR, Hochhauser L, Romo S, Tyson JE. Postnatal dexamethasone therapy and cerebral tissue volumes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2007;119:265–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peltoniemi OM, Kari MA, Tammela O, Lehtonen L, Marttila R, Halmesmaki E, Jouppila P, Hallman M. Randomized trial of a single repeat dose of prenatal betamethasone treatment in imminent preterm birth. Pediatrics. 2007;119:290–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Phillips DP, Carr MM. Disturbances of loudness perception. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998;9:371–9. quiz 399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Poston L. Developmental programming and diabetes - The human experience and insight from animal models. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:541–52. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quinlivan JA, Archer MA, Evans SF, Newnham JP, Dunlop SA. Fetal sciatic nerve growth is delayed following repeated maternal injections of corticosteroid in sheep. J Perinat Med. 2000;28:26–33. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2000.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quinlivan JA, Beazley LD, Evans SF, Newnham JP, Dunlop SA. Retinal maturation is delayed by repeated, but not single, maternal injections of betamethasone in sheep. Eye. 2000;14(Pt 1):93–8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quinlivan JA, Evans SF, Dunlop SA, Beazley LD, Newnham JP. Use of corticosteroids by Australian obstetricians--a survey of clinical practice. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;38:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1998.tb02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenhall U, Nordin V, Brantberg K, Gillberg C. Autism and auditory brain stem responses. Ear Hear. 2003;24:206–14. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000069326.11466.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rossi GT, Britt RH. Effects of hypothermia on the cat brain-stem auditory evoked response. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;57:143–55. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russell WMS, Burch RL, Hume CW. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique, Editoin. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare; London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salm AK, Pavelko M, Krouse EM, Webster W, Kraszpulski M, Birkle DL. Lateral amygdaloid nucleus expansion in adult rats is associated with exposure to prenatal stress. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;148:159–67. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Samtani MN, Pyszczynski NA, Dubois DC, Almon RR, Jusko WJ. Modeling glucocorticoid-mediated fetal lung maturation: I. Temporal patterns of corticosteroids in rat pregnancy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:117–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Samtani MN, Pyszczynski NA, Dubois DC, Almon RR, Jusko WJ. Modeling glucocorticoid-mediated fetal lung maturation: II. Temporal patterns of gene expression in fetal rat lung. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:127–38. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saste MD, Carver JD, Stockard JE, Benford VJ, Chen LT, Phelps CP. Maternal diet fatty acid composition affects neurodevelopment in rat pups. J Nutr. 1998;128:740–3. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sawady J, Mercer BM, Wapner RJ, Zhao Y, Sorokin Y, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, Peaceman AM, Leveno KJ, et al. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network Beneficial Effects of Antenatal Repeated Steroids study: impact of repeated doses of antenatal corticosteroids on placental growth and histologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:281 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seckl JR. Prenatal glucocorticoids and long-term programming. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151(Suppl 3):U49–62. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151u049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Glucocorticoid “programming” and PTSD risk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:351–78. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shinwell ES, Karplus M, Reich D, Weintraub Z, Blazer S, Bader D, Yurman S, Dolfin T, Kogan A, Dollberg S, et al. Early postnatal dexamethasone treatment and increased incidence of cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;83:F177–81. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.3.F177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Slotkin TA, Lappi SE, McCook EC, Tayyeb MI, Eylers JP, Seidler FJ. Glucocorticoids and the development of neuronal function: effects of prenatal dexamethasone exposure on central noradrenergic activity. Biol Neonate. 1992;61:326–36. doi: 10.1159/000243761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith LM, Qureshi N, Chao CR. Effects of single and multiple courses of antenatal glucocorticoids in preterm newborns less than 30 weeks’ gestation. J Matern Fetal Med. 2000;9:131–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(200003/04)9:2<131::AID-MFM9>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Starr A, Sininger Y, Nguyen T, Michalewski HJ, Oba S, Abdala C. Cochlear receptor (microphonic and summating potentials, otoacoustic emissions) and auditory pathway (auditory brain stem potentials) activity in auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2001;22:91–9. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stockard JJ, Sharbrough FW, Tinker JA. Effects of hypothermia on the human brainstem auditory response. Ann Neurol. 1978;3:368–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.410030416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tas A, Yagiz R, Tas M, Esme M, Uzun C, Karasalihoglu AR. Evaluation of hearing in children with autism by using TEOAE and ABR. Autism. 2007;11:73–9. doi: 10.1177/1362361307070908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thivierge J, Bedard C, Cote R, Maziade M. Brainstem auditory evoked response and subcortical abnormalities in autism. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1609–13. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.12.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Uno H, Lohmiller L, Thieme C, Kemnitz JW, Engle MJ, Roecker EB, Farrell PM. Brain damage induced by prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in fetal rhesus macaques. I. Hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;53:157–67. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90002-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Waddell BJ, Bollen M, Wyrwoll CS, Mori TA, Mark PJ. Developmental programming of adult adrenal structure and steroidogenesis: effects of fetal glucocorticoid excess and postnatal dietary omega-3 fatty acids. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:171–8. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Mele L, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, Peaceman AM, Leveno KJ, Malone F, Caritis SN, et al. Long-term outcomes after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1190–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wapner RJ, Sorokin Y, Thom EA, Johnson F, Dudley DJ, Spong CY, Peaceman AM, Leveno KJ, Harper M, Caritis SN, et al. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids: evaluation of safety and efficacy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:633–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Welberg LA, Seckl JR, Holmes MC. Prenatal glucocorticoid programming of brain corticosteroid receptors and corticotrophin-releasing hormone: possible implications for behaviour. Neuroscience. 2001;104:71–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Whitelaw A, Thoresen M. Antenatal steroids and the developing brain. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;83:F154–7. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.2.F154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yeh TF, Lin YJ, Lin HC, Huang CC, Hsieh WS, Lin CH, Tsai CH. Outcomes at school age after postnatal dexamethasone therapy for lung disease of prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1304–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yossuck P, Kraszpulski M, Salm AK. Perinatal corticosteroid effect on amygdala and hippocampus volume during brain development in the rat model. Early Hum Dev. 2006;82:267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zuo J, Curtis LM, Yao X, ten Cate WJ, Bagger-Sjoback D, Hultcrantz M, Rarey KE. Glucocorticoid receptor expression in the postnatal rat cochlea. Hear Res. 1995;87:220–7. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00092-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]