Abstract

Autoantibodies against gangliosides GM1 or GD1a are associated with acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) and acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN), whereas antibodies to GD1b ganglioside are detected in acute sensory ataxic neuropathy (ASAN). These neuropathies have been proposed to be closely related and comprise a continuous spectrum, although the underlying mechanisms, especially for sensory nerve involvement, are still unclear. Antibodies to GM1 and GD1a have been proposed to disrupt the nodes of Ranvier in motor nerves via complement pathway. We hypothesized that the disruption of nodes of Ranvier is a common mechanism whereby various anti-ganglioside antibodies found in these neuropathies lead to nervous system dysfunction. Here, we show that the IgG monoclonal anti-GD1a/GT1b antibody injected into rat sciatic nerves caused deposition of IgG and complement products on the nodal axolemma and disrupted clusters of nodal and paranodal molecules predominantly in motor nerves, and induced early reversible motor nerve conduction block. Injection of IgG monoclonal anti-GD1b antibody induced nodal disruption predominantly in sensory nerves. In an ASAN rabbit model associated with IgG anti-GD1b antibodies, complement-mediated nodal disruption was observed predominantly in sensory nerves. In an AMAN rabbit model associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies, complement attack of nodes was found primarily in motor nerves, but occasionally in sensory nerves as well. Periaxonal macrophages and axonal degeneration were observed in dorsal roots from ASAN rabbits and AMAN rabbits. Thus, nodal disruption may be a common mechanism in immune-mediated neuropathies associated with autoantibodies to gangliosides GM1, GD1a, or GD1b, providing an explanation for the continuous spectrum of AMAN, AMSAN, and ASAN.

Keywords: node of Ranvier, acute motor axonal neuropathy, acute sensory ataxic neuropathy, ganglioside, autoantibody

Introduction

Recent discoveries of autoantibodies against gangliosides, a group of glycosphingolipids with sialic acid, have provided profound insights into the mechanisms of autoimmune neuropathies (van Doorn et al., 2008). The anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated neuropathies are quite diverse in antibody profiles and clinical manifestations. For example, various antibodies can be found in one neuropathy subtype: IgG antibodies to GM1, GD1a, GalNAc-GD1a, or GM1b are detected in acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) (van Doorn et al., 2008). In addition, one anti-ganglioside antibody may induce different conditions: IgG anti-GM1 antibodies are associated with both AMAN (predominantly motor involvement) and acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) (both sensory and motor involvements) (Griffin et al., 1996a; Yuki et al., 1999). IgG anti-GD1b antibodies are found in the acute sensory ataxic neuropathy (ASAN) or ataxic Guillain-Barré syndrome (Pan et al., 2001; Notturno et al., 2008; Ito et al., 2011). Despite this remarkable diversity, these neuropathies may be regarded as closely related and comprise a continuous spectrum.

How can various anti-ganglioside antibodies induce distinct, but similar types of neuropathies? We hypothesized that these acute immune-mediated neuropathies are caused by the same pathophysiologic mechanism. Furthermore, we hypothesize that disruptions are more likely to occur at areas along the neuron where the axolemma is exposed, i.e. nodes of Ranvier could represent a primary target. Nodes of Ranvier are critical for action potential generation and propagation due to high densities of voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels enriched at the nodal axolemma which are responsible for action potential generation (Susuki and Rasband, 2008). Gangliosides GM1, GD1a, or GD1b are highly enriched at or near nodes (for review, see Kaida et al., 2009). In human AMAN and AMSAN, an early pathological feature includes the widening of the nodes of Ranvier with deposition of complement products (Griffin et al., 1996a; Griffin et al., 1996b; Hafer-Macko et al., 1996). The complement system plays a central role in immune response to eliminate invading pathogens, although the disruption of a fine balance of complement activation and regulation may cause injury and contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases (Ramaglia et al., 2008). In an AMAN rabbit model induced by immunization with gangliosides, the IgG anti-GM1 antibodies bind the nodes in the ventral roots, activate the complement pathway, and disrupt the molecular organization of nodes including clustered Nav channels (Susuki et al., 2007). Consistent with these data, in ex vivo and in vivo transfer models using mutant mice overexpressing a-series gangliosides (e.g. GD1a), a monoclonal IgG antibody reactive with GD1a disrupted the nodes in distal motor nerves via the complement pathway (McGonigal et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that the complement-mediated nodal disruption is a common mechanism in these anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated neuropathies.

In this study, we address the following questions: 1) can various anti-ganglioside antibodies cause nodal disruption, and 2) are sensory neurons affected by anti-ganglioside antibodies via the same mechanism? Here, we first provide the evidence that IgG anti-ganglioside antibodies can disrupt the nodes in sensory nerve fibers via complement pathway. Our results provide an explanation for the continuous spectrum of AMAN, AMSAN, and ASAN.

Methods

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: FITC-conjugated goat IgG antibodies to C3 component of rabbit or rat complement (Nordic Immunological Laboratories); chicken polyclonal antibody to rabbit membrane attack complex (MAC), kindly provided by Dr. B.R. Lucchesi (University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI); mouse monoclonal antibody to rabbit macrophage (RAM11) (DAKO Cytomation); mouse monoclonal antibody against pan Nav channel (Rasband et al., 1999); guinea pig antibody to Caspr, kindly provided by Dr. J. Black (Yale University, New Haven, CT); rabbit antibody to Caspr (Schafer et al., 2004); rabbit anti-βIV spectrin SD (Berghs et al., 2000); chicken anti-βIV spectrin generated and affinity purified against the same peptide; and goat anti-choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) antibody (Millipore). For intraneural injection, the previously well-characterized mouse monoclonal anti-ganglioside antibodies were used (Lunn et al., 2000; Schnaar et al., 2002; Lopez et al., 2008, summarized in Supplementary table 1). As control, we used mouse IgG1 and IgG2b that are not reactive to any rat antigens (abcam). AMCA-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Other fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen.

Intraneural injection

Adult Sprague Dawley rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (80 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine hydrochloride (16 mg/kg body weight). The left sciatic nerves or tibial nerves were exposed aseptically and injected with 4 µl of antibody solution (1 µg/µl) mixed with 1 µl of rabbit complement (EMD Chemicals) using a glass micropipette. Rabbit complement was used as a source of complement, because, among human, guinea pig, rabbit, rat and mouse complements tested, the rabbit complement was most effective for the monoclonal anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated cytotoxicity assays (Zhang et al., 2004). After surgery, buprenorphine hydrochloride was injected subcutaneously for pain relief. This animal procedure was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Baylor College of Medicine (protocol AN-4634), and conforms to the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Nerve conduction study

Conduction in motor nerve fibers was examined using 16 to 18 week old rats as described elsewhere (Susuki et al., 2003) with modifications. In brief, rats were anesthetized by ketamine and xylazine, and body temperature was kept between 36.0 and 37.0°C by use of a heating pad. The left tibial nerve was stimulated at the ankle and knee, and the evoked compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) were amplified and displayed on a PowerLab signal acquisition set-up (AD Instruments).

ASAN and AMAN rabbit model

To induce ASAN, 0.5 mg of GD1b ganglioside (Sigma) was injected subcutaneously to the back of male Japanese white rabbits (Kbs:JW) at three week intervals as described elsewhere (Susuki et al., 2004). Clinical signs of immunized rabbits were carefully observed on a daily basis. Induction of the AMAN rabbit model and anti-ganglioside serology is described elsewhere (Susuki et al., 2004; Yuki et al., 2001). These experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Dokkyo Medical University (approval numbers 0342 and 0511). Rabbits were treated according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Dokkyo Medical University.

Immunohistochemistry

Rat sciatic nerve and rabbit nerve root specimens were prepared and the immunohistochemical studies were performed as described (Schafer et al., 2004; Susuki et al., 2007). In brief, after the permeabilization in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 10% goat serum for 1 hr, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted to appropriate concentrations in the same buffer. Goat anti-ChAT antibody and Alexa 594-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody was diluted in the 0.1 M phosphate buffer containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% bovine serum albumin. Then the sections were thoroughly rinsed, followed by application of fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Digital images were collected on an Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope fitted with an ApoTome for optical sectioning (Zeiss). For quantification, nodes were considered to be disrupted when there was an apparent change in shape or loss of the clusters of βIV spectrin (rat sciatic nerves) or Nav channel (rabbit nerve roots). When nodal or paranodal molecules were completely absent, nodes were identified based on the morphology seen by relatively strong nonspecific staining on the myelin outer surface or differential interference contrast images.

Morphological analyses

The lumbar spinal nerve root, cauda equina, and spinal cord specimens were evaluated pathologically, as described (Yuki et al., 2001). For electron microscopy, ultrathin sections cut from tissue fragments embedded in Epon 812 resin were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and then examined using a Hitachi-7100 electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo).

Statistical analysis

The differences of data in immunohistochemistry or electrophysiological analyses were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Differences are considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

Injected monoclonal anti-ganglioside antibody disrupts nodes in rat sciatic nerves

To demonstrate the ability of antibodies to induce nodal lesions, we used an intraneural injection model, because this model is useful to test various antibodies in a short time course. We first tried GD1a/GT1b-2b (IgG2b reactive with GD1a, GT1b, GT1aα, and weakly with GalNAc-GD1a) (Lunn et al., 2000; Gong et al., 2002) that has been shown to bind nodes in rat peripheral nerves (Gong et al., 2002), and to induce axonal neuropathy in mice (Sheikh et al., 2004). By injecting GD1a/GT1b-2b together with rabbit complement, we found the deposition of mouse IgG and complement component C3 (Fig. 1B) at nodes in the injected sites. Clusters of βIV spectrin at nodes and contactin-associated protein (Caspr) at paranodes (Susuki and Rasband, 2008) were disorganized or completely absent in association with massive complement deposition (Fig. 1B). The peak of the autoimmune nodal lesions seemed to be 3–5 days after injection (Supplementary figure 1), similar to the previous observations of nerve conduction abnormalities induced by intraneural injection of human sera containing anti-GM1 antibodies (Santoro et al., 1992; Uncini et al., 1993). When the injection was repeated at day 3, the disrupted βIV spectrin staining was found in 17–33% of the nodes at day 4 (Fig. 1C), whereas a single injection caused disruption only in 8 or 9% of the nodes at days 3 or 5, respectively (Supplementary figure 1). The frequency of disrupted βIV spectrin staining was much greater in nodes with complement deposition (46 of 145, 31.7%) compared to nodes without complement deposition in GD1a/GT1b-2b injected nerve (6 of 152, 3.8%), suggesting the necessity of complement activation for nodal disruption. Importantly, injection of GD1a/GT1b-2b alone (without adding rabbit complement) twice in the same protocol caused IgG deposition in 43.1% of nodes, C3 deposition in 30.2%, and nodal disruption in 10.8% (data were obtained from two rats). Thus, the nodal disruption could be enhanced by adding rabbit complement, whereas the injected GD1a/GT1b-2b has the ability to activate the rat complement pathway.

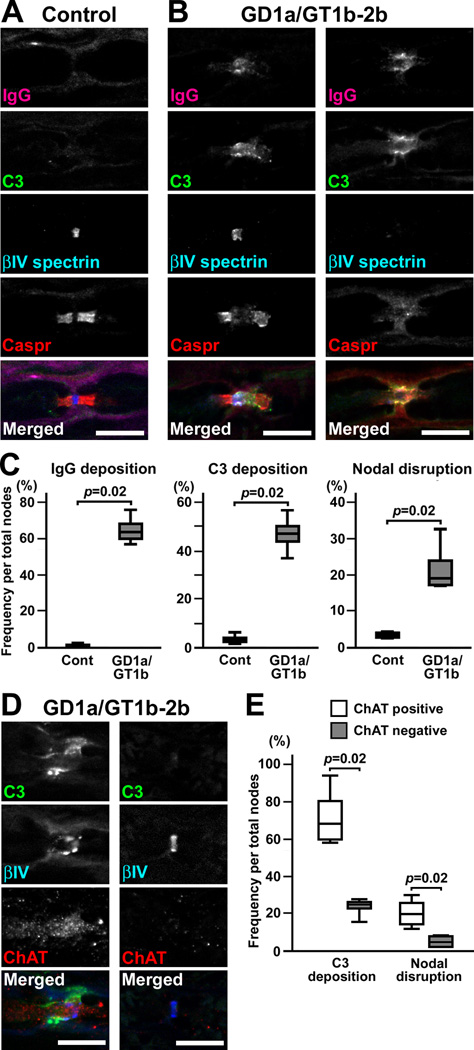

Fig. 1. GD1a/GT1b-2b disrupts predominantly motor nerve nodes via the complement pathway.

(A,B) Immunofluorescence analyses in longitudinal sections of rat sciatic nerves injected with control IgG2b or GD1a/GT1b-2b. Nerve fibers run horizontally in all panels. Sections are stained by antibodies to mouse IgG (magenta), C3 component of complement (green), βIV spectrin (blue), and Caspr (red). Control IgG2b weakly binds to the outer surface of myelin, but no C3 deposition is seen (A). Deposition of GD1a/GT1b-2b and C3 is associated with the abnormally lengthened gap between paranodal Caspr clusters with preserved nodal βIV spectrin (B, left column), or with completely damaged βIV spectrin and Caspr clusters (B, right column).

(C) Frequency of immune-mediated nodal disruption after repeated injection of GD1a/GT1b-2b in rat sciatic nerves at day 4. The depositions of IgG or C3, or disrupted nodes are significantly more frequent by injection of GD1a/GT1b-2b compared to control IgG2b (n=4 in each group). For quantification, 200–300 nodes were observed in each rat sciatic nerve.

+(D) Representative images of nodes in sciatic nerves at day 4 after repeated injection of GD1a/GT1b-2b together with complement. Left column shows disrupted node (shown by βIV spectrin in blue) with C3 deposition (green) in ChAT positive axon (red). Right column shows preserved node in ChAT negative axon.

(E) Quantitation of C3 deposition and nodal disruption in ChAT positive or negative nodes at day 4. Data were collected from four animals.

Scale bars = 10 µm (A,B,D).

Does GD1a/GT1b-2b disrupt nodes in motor nerves, sensory nerves, or both? To address this question, we used anti-ChAT antibody as a marker for motor nodes. ChAT is involved in the metabolism of acetylcholine which is a neurotransmitter for motoneurons, and anti-ChAT antibody can be used as a motor axon marker in the rat sciatic nerve injury model (Castro et al., 2008). We confirmed that the anti-ChAT antibody labels axons in rat ventral roots but not in dorsal roots prepared by our fixation protocol (Supplementary figure 2). By immunostaining of the GD1a/GT1b-2b injected nerves, we found that the C3 deposition and disrupted βIV spectrin clustering was significantly more frequent in ChAT positive nodes than in ChAT negative nodes (Fig. 1D,E). This finding strongly suggests that the GD1a/GT1b-2b preferentially affects motor nodes but can also involve sensory nodes, corresponding well with clinical observation that IgG anti-GD1a antibodies were detected in both AMAN and AMSAN (Yuki et al., 1999).

To examine if the autoimmune nodal lesions cause conduction failure, we performed a serial motor nerve conduction study. Control IgG2b or GD1a/GT1b-2b was injected together with complement into rat tibial nerves half way between ankle and knee twice (days 0 and 3). At days 4 and 7, the CMAP amplitude recorded from the plantar muscle after stimulation at the knee (proximal to injection site) was significantly reduced compared to that after stimulation at the ankle (distal to injection site) (Fig. 2A,B). There were no significant changes in motor nerve conduction velocity (MCV) (Fig. 2C) or the proximal/distal (P/D) ratio of CMAP duration (Fig 2D). These data demonstrate the presence of partial nerve conduction block involving a fraction of myelinated motor axons between the ankle and knee, corresponding well with immunohistochemistry data (Fig. 1C,E). Furthermore, the proximal CMAP amplitude returned to normal by day 21 (Fig. 2A,B). Thus, similar to the electrophysiology in human AMAN patients (Kokubun et al., 2010), complement-mediated nodal disruption can cause rapidly reversible nerve conduction failure.

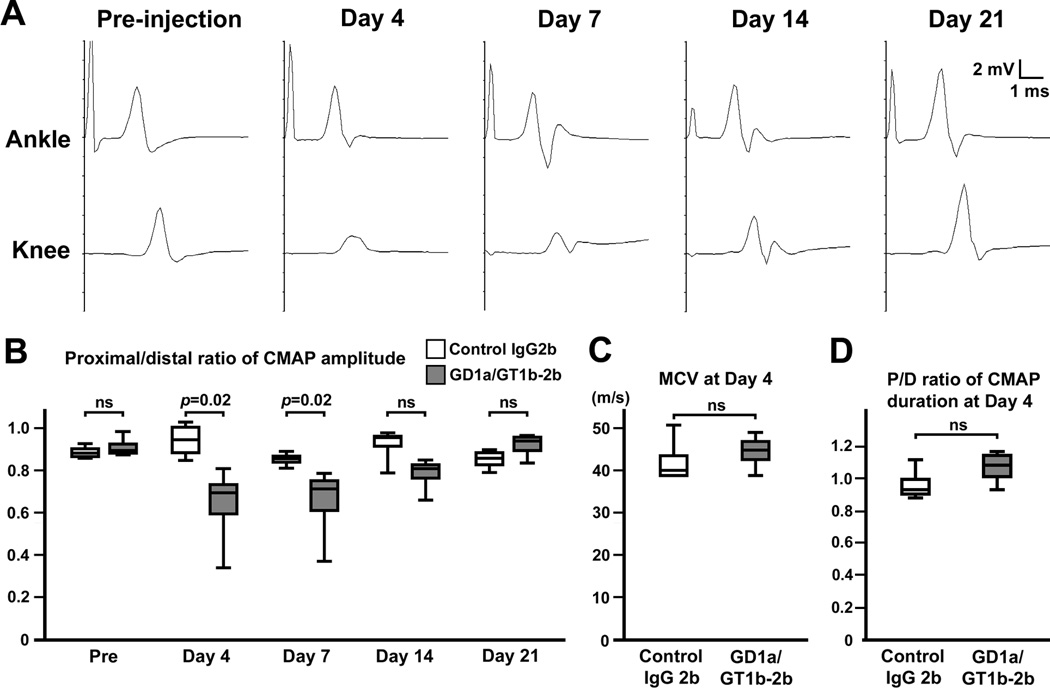

Fig. 2. Serial nerve conduction study in GD1a/GT1b-2b injected nerves.

Control IgG2b or GD1a/GT1b-2b was injected into rat tibial nerves half way between ankle and knee twice (days 0 and 3). Nerve conduction study of tibial nerve was performed serially at different time points: pre-injection, days 4, 7, 14, and 21.

(A) Representative wave forms from one animal injected with GD1a/GT1b-2b. At day 4, the amplitude after stimulation at the knee is abnormally reduced. Temporal dispersion is not apparent. The abnormal amplitude reduction disappears by day 21 without apparent late components.

(B) Temporal changes of P/D ratio of CMAP amplitude (between the base line and negative peak) in rat tibial nerve injected with control IgG2b or GD1a/GT1b-2b. The same animals were analyzed for serial nerve conduction study (n=4 in each group). At days 4 and 7, P/D ratio of CMAP amplitude was significantly reduced in GD1a/GT1b-2b injected nerves. At day 14, the ratio still tended to be lower than control, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. By day 21, the ratio returned to normal.

(C) There is no significant difference of MCV in the ankle-knee segment of tibial nerves between control and GD1a/GT1b-2b groups at day 4 (n=4 in each group).

(D) There is no significant difference of P/D ratio of CMAP duration (from the onset to the final return to baseline) between control and GD1a/GT1b-2b groups at day 4 (n=4 in each group).

IgG monoclonal antibodies to b-series gangliosides disrupt nodes

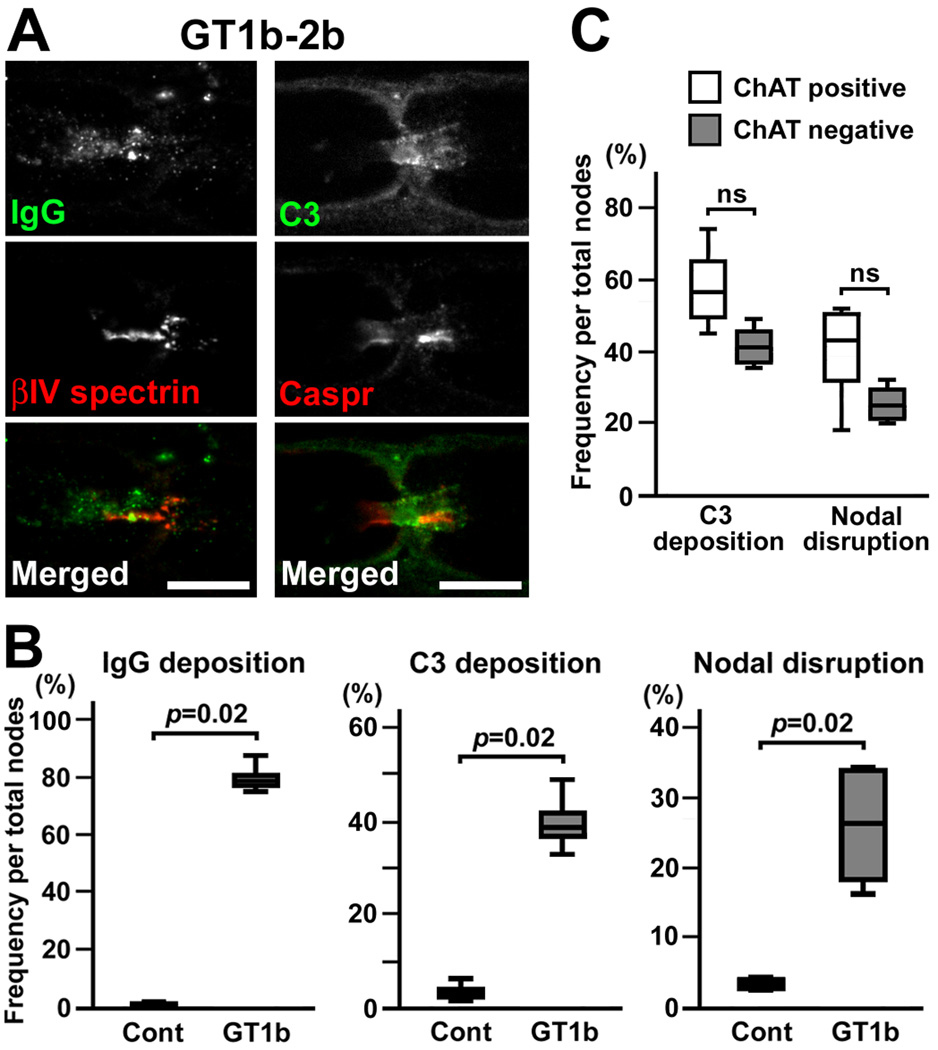

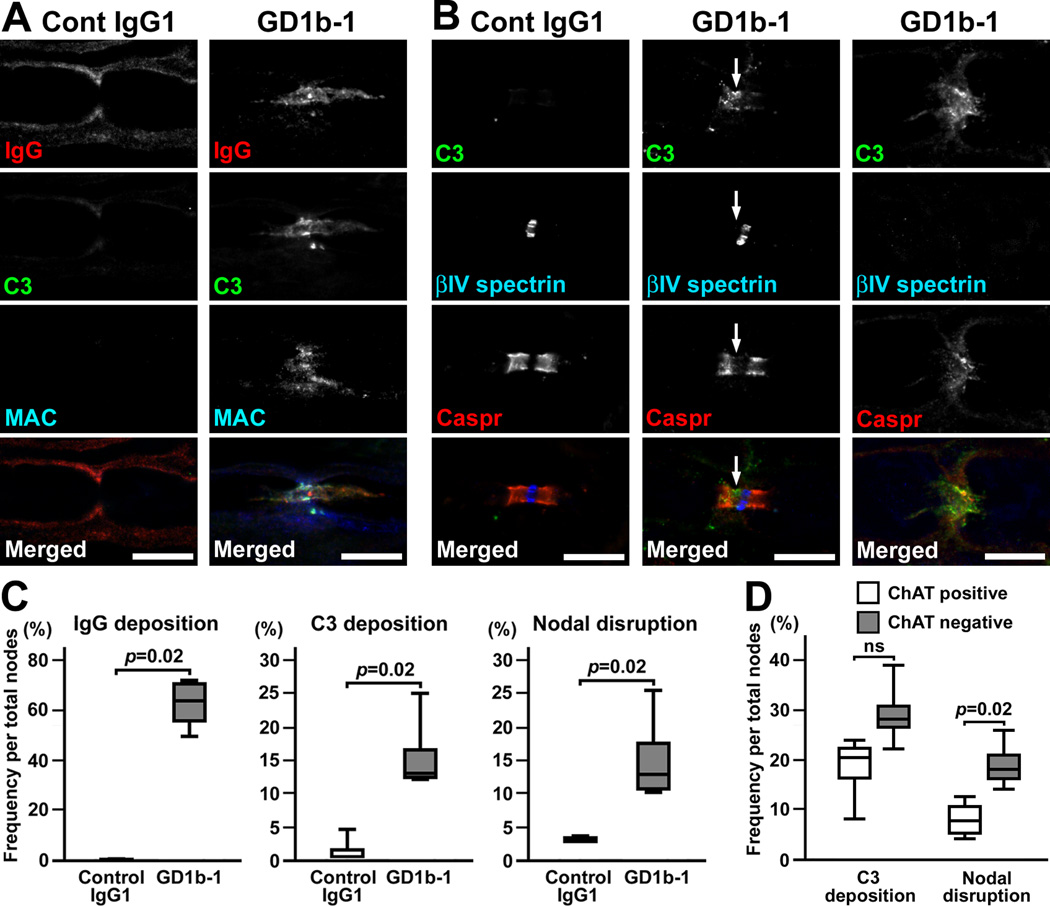

Next, we tested the ability of various anti-ganglioside antibodies to induce nodal lesions by the same protocol: the injection of monoclonal antibody together with rabbit complement twice at days 0 and 3. Surprisingly, injection of GM1-1 or GM1-2b (Schnaar et al., 2002) did not induce IgG deposition at the nodal axolemma or nodal disruption (two rats each). By injecting GD1a-1 or GD1a-2b (Schnaar et al., 2002), weak IgG deposition was seen at the axolemma in some nodes, but complement deposition or nodal disruption was not apparent (two rats each). By injecting GD1a-E6 (Lopez et al., 2008), we found a few nodal lesions associated with IgG and complement deposition (two rats each). In contrast, injection of GT1b-2b (monoclonal IgG2b monospecific to GT1b) (Schnaar et al., 2002) induced robust nodal lesions (Fig. 3A,B). We found C3 deposition and nodal disruption in both ChAT positive and negative axons. Although the ChAT positive nodes tended to be more frequently involved than ChAT negative nodes, the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, GD1b-1 (monoclonal IgG1 monospecific to GD1b) (Schnaar et al., 2002) induced the deposition of IgG and the complement products on the nodal axolemma, and disrupted clusters of nodal and paranodal molecules (Fig. 4A–C). Importantly, in contrast to GD1a/GT1b-2b (Fig. 1E), sensory nodes were more preferentially affected by GD1b-1. The disruption of nodal βIV spectrin staining was significantly more frequent in ChAT negative nodes than in ChAT positive nodes, although the difference of C3 deposition did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4D). These results may correspond well with the clinical observation that the monospecific IgG anti-GD1b antibody is found in ASAN patients (Pan et al., 2001; Notturno et al., 2008; Ito et al., 2011).

Fig. 3. Nodal lesions caused by injection of GT1b-2b.

(A) Immunofluorescent studies in longitudinal sections of rat sciatic nerves injected with GT1b-2b. Nerve fibers run horizontally in all panels. Left column shows deposition of mouse IgG (green) and a disrupted nodal βIV spectrin cluster (red). Right column shows deposition of C3 (green) and altered paranodal Caspr staining (red).

(B) Frequency of immune-mediated nodal disruption by GT1b-2b. The depositions of IgG or C3, or disrupted nodes are significantly more frequent by injection of GT1b-2b compared to control IgG2b (n=4 in each group). Two hundred-300 nodes were observed in each nerve.

(C) Quantitation of C3 deposition and nodal disruption in ChAT positive or negative nodes in GT1b-2b injected nerves. Data were collected from four animals.

Scale bars = 10 µm (A).

Fig. 4. Nodal lesions predominantly in sensory fibers caused by injection of GD1b-1.

(A,B) Immunofluorescent studies in longitudinal sections of rat sciatic nerves injected with control IgG1 or GD1b-1. Nerve fibers run horizontally in all panels.

(A) Sections are stained by antibodies to mouse IgG (red), C3 (green), and MAC (blue). Nonspecific binding of mouse control IgG1 is seen along the outer surface of the myelin sheath, but no staining on the axolemma was observed (left column). There are no apparent depositions of C3 or MAC. In GD1b-1 injected nerve (right column), depositions of IgG, C3, and MAC are seen on the axolemma at and near node.

(B) Sections are stained by antibodies to C3 (green), βIV spectrin (blue), and Caspr (red). The nerve injected with control IgG1 does not show nodal C3 deposition, and clusters of nodal βIV spectrin and paranodal Caspr remain intact (left column). In the nerves injected with GD1b-1, the Caspr cluster on the left side seems to be reduced in association with C3 deposition, resulting in widening of the nodal gap (middle column, arrows). At the node with massive C3 deposition, both βIV spectrin and Caspr clusters are remarkably disrupted or disappear (right column).

(C) Frequency of immune-mediated nodal disruption by GD1b-1. The depositions of IgG or C3, or disrupted nodes are significantly more frequent by injection of GD1b-1 compared to control IgG1 (n=4 in each group). Two hundred-300 nodes were observed in each nerve.

(D) Quantitation of C3 deposition and nodal disruption in ChAT positive or negative nodes in GD1b-1 injected nerves. Data were collected from four animals.

Scale bars = 10 µm (A,B).

Sensory node disruption in ASAN model

Next, to test if the sensory nodes are a primary autoimmune lesion in ASAN, we analyzed the ASAN animal model (Kusunoki et al., 1996). Seven of 17 rabbits sensitized with GD1b developed acute ataxia and plasma IgG anti-GD1b antibodies (summarized in Supplementary table 2). One rabbit with ataxia died unexpectedly. Two rabbits with ataxia were available for immunohistochemical analyses. In dorsal roots from the ASAN rabbit (animal ID: Db-1), we found the deposition of IgG, C3, and MAC (Fig. 5A), and disrupted or no clusters of nodal and paranodal molecules (Fig. 5B). The diameter of Nav channel clusters (axon diameter at nodes) was 4.08 ± 1.16 µm in C3-positive nodes (mean ± SD, n=66), whereas it was 1.89 ± 0.83 µm in C3-negative nodes (n=65). Thus, the larger axons may be mainly affected by IgG anti-GD1b antibodies, and may correspond well with the clinical symptoms of prominent ataxia. In dorsal roots from another ASAN rabbit (Db-2), we occasionally found binary Nav channel clusters on both sides of a nodal gap with complement deposition (Fig. 5C), a common characteristic of nodes during the recovery phase in AMAN rabbits (Susuki et al., 2007). This rabbit may have been already in the recovery phase of the disease, although it was difficult to evaluate the temporal change of ataxia in animals. Similar nodal lesions were present in ventral roots from rabbit Db-1, although the disruption of the Nav channel clusters was rare compared to the dorsal roots (Fig. 5D,E). Four rabbits with ataxia were used for morphological analyses. As reported previously (Kusunoki et al., 1996), axonal degeneration was found in dorsal roots and spinal cord dorsal column from three of four rabbits with ataxia (Fig. 6A; Supplementary table 2).

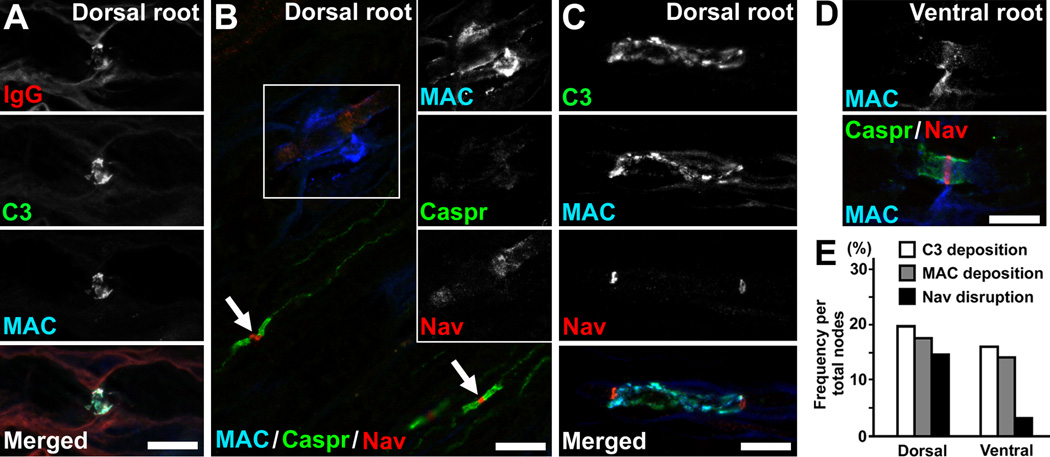

Fig. 5. Disruption of sensory nodes in an ASAN model induced by immunizing with GD1b.

Nerve root sections obtained from the ASAN rabbit Db-1 (A,B,D,E) or Db-2 (C).

(A) Deposition of IgG (red), C3 (green), and MAC (blue) at the nodes in dorsal root section. The nerve fiber runs horizontally.

(B) Disrupted node and paranodes in dorsal root. The section is stained by antibodies to MAC (blue), Caspr (green), and Nav channels (red). Black and white images of individual colors of boxed area are shown in insets. Both Caspr and Nav channel clusters are completely destroyed at the affected node with massive MAC deposition. Arrows indicate normal nodes without MAC staining.

(C) Disrupted nodes with binary Nav channel clusters on both sides of complement deposition in a dorsal root.

(D) In a ventral root, MAC deposition is seen at the node, but Nav channel and Caspr staining is preserved.

(E) The frequency of nodal disruption in the ASAN rabbit Db-1. The Nav channel cluster disruption is more frequent in dorsal roots than in ventral roots. Data were obtained from approximately 300 nodes observed in three different nerve root specimens.

Scale bars = 10 µm (A–D).

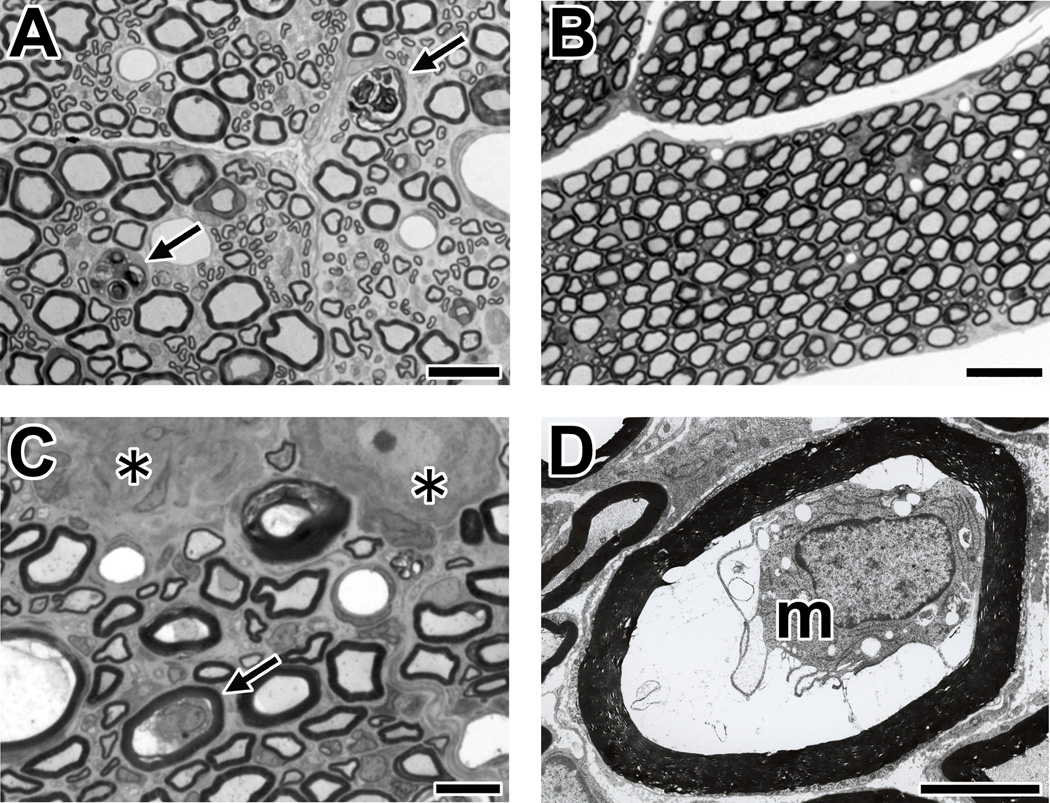

Fig. 6. Morphological analyses of sensory nerves in ASAN rabbits.

The tissues from an ASAN rabbit Db-4 are shown.

(A) Wallerian-like degeneration of sensory nerve fibers in a cross-section of the dorsal root with toluidine blue stain. The arrows indicate the myelin ovoids produced by Wallerian-like degeneration of the myelinated nerve fibers.

(B) There are no pathological changes in the ventral root (toluidine blue stain).

(C,D) Macrophages in sensory nerve fibers with a preserved myelin sheath (arrow). The cross-section of DRG. A nerve fiber with macrophage in panel C (arrow, toluidine blue stain) is shown by electron microscopy (m, macrophage) (panel D). Asterisks indicate the DRG neurons.

Scale bars = 20 µm (A); 50 µm (B); 10 µm (C); 5 µm (D).

Furthermore, we found macrophages with damaged axons surrounded by preserved myelin sheath in dorsal roots and/or spinal cord dorsal column from three of four ASAN rabbits (Fig. 6C,D; Supplementary table 2). These pathological findings are identical to those in ventral roots from AMAN patients (Griffin et al., 1996b) and AMAN rabbits (Susuki et al., 2003; Yuki et al., 2004). Neither axonal degeneration nor periaxonal macrophages were apparent in ventral roots from these four ASAN rabbits (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that IgG anti-GD1b antibodies can disrupt sensory nodes via the complement pathway, and provide a mechanism underlying sensory ataxia.

Sensory node disruption by IgG anti-GM1 antibodies

IgG anti-GM1 antibodies are associated with AMSAN (Yuki et al., 1999), and nodes of Ranvier were lengthened in both dorsal and ventral roots from AMSAN patients (Griffin et al., 1996a). Do IgG anti-GM1 antibodies affect sensory nodes by the same mechanisms? Although we did not see sensory nerve involvement in our first set of experiments (Yuki et al., 2001), we decided to thoroughly re-investigate sensory nerve fibers in AMAN rabbits associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies. The specimens of spinal cords, spinal nerve roots, and dorsal root ganglions (DRGs) from previously published AMAN rabbits (Yuki et al., 2001; Susuki et al., 2003; Susuki et al., 2004; Susuki et al., 2007) or from animals used in unpublished preliminary experiments were newly processed for immunohistochemical or pathological analyses. We found sensory nerve lesions in some AMAN rabbits (summarized in Supplementary table 3). For immunohistochemistry, dorsal root specimens were available from 12 AMAN rabbits induced by immunization of bovine brain ganglioside mixture and associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies (eight rabbits described in Susuki et al., 2007; four rabbits from previously unpublished experiments). We found autoimmune nodal lesions in the dorsal root in one of 12 AMAN rabbits (Animal ID: Bg-24). The nodal IgG and complement deposition was only mild and nodal Nav channel clusters were mostly preserved (Fig. 7A,B). In contrast, in the ventral roots from the same animal, massive complement deposition was associated with both nodal and paranodal disruption (Fig. 7C). The frequency of complement deposition and nodal disruption was much higher in ventral roots than in dorsal roots (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, morphological analyses revealed Wallerian-like degeneration in dorsal roots or dorsal columns in two of eight (25%) GM1-sensitized rabbits with paralysis and five of 32 (16%) bovine brain ganglioside mixture-sensitized rabbits with paralysis (Fig. 8A,B; Supplementary table 3). In addition, in dorsal roots from one AMAN rabbit (Cr-16) (Susuki et al., 2003), we occasionally found periaxonal macrophages (Fig. 8C,D). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that IgG anti-GM1 antibodies can attack nodes of Ranvier in sensory as well as motor nerves, although the motor axons are the ones that are predominantly affected in this animal model of AMAN.

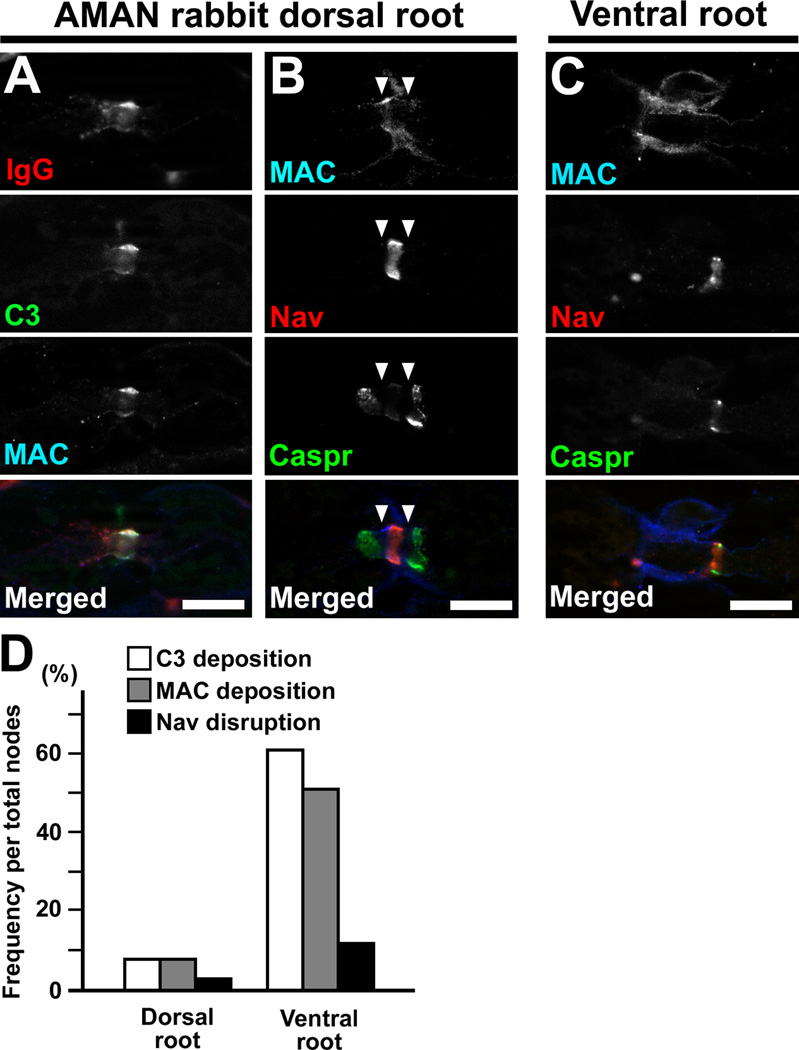

Fig. 7. Sensory node involvement in AMAN rabbit associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies.

(A–C) Nerve root sections from an AMAN rabbit Bg-24. This rabbit developed limb weakness 104 days from first immunization, and was sacrificed 14 days from onset of weakness. The nerve fibers run horizontally.

(A) Deposition of IgG (red), C3 (green), and MAC (blue) at the nodes in dorsal root.

(B) Affected node with MAC deposition (blue) in dorsal root. The arrowheads indicate the gap between abnormally widened paranodal Caspr clusters and a preserved nodal Nav channel cluster.

(C) Affected node from a ventral root in the same rabbit. The section is stained by antibodies to MAC (blue), Caspr (green), and Nav channels (red).

(D) The frequency of complement deposition and nodal disruption in an AMAN rabbit Bg-24. The nodal complement deposition and Nav channel cluster disruption are less frequent in dorsal root than in ventral root. Data were obtained from 100 nodes.

Scale bars = 10 µm (A–C).

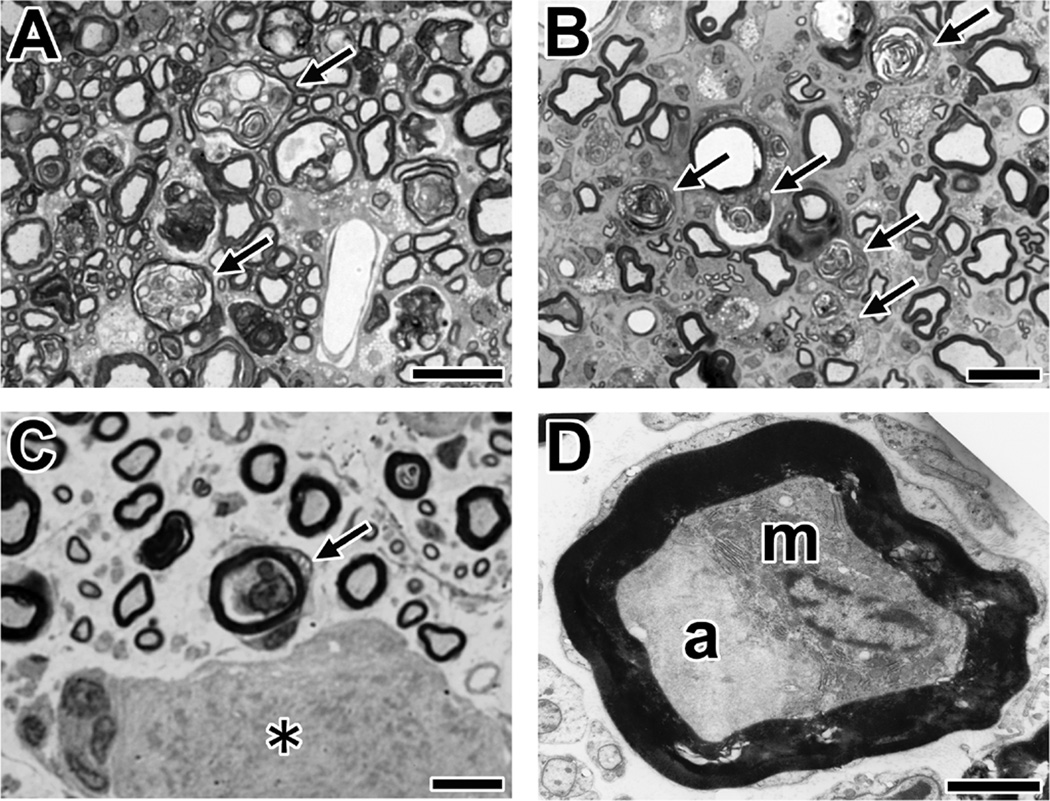

Fig. 8. Morphological analyses of AMAN rabbits associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies.

(A,B) Wallerian-like degeneration of sensory nerve fibers. Shown are cross-sections of the spinal cord dorsal column (A) or dorsal root (B) from AMAN rabbit (Bg-8) using toluidine blue stain. The arrows indicate the myelin ovoids produced by Wallerian-like degeneration of the myelinated nerve fibers.

(C) A macrophage in a sensory nerve fiber with a preserved myelin sheath (arrow) in the section of DRG using toluidine blue stain. The asterisk indicates the DRG neuron. A DRG section from an AMAN rabbit (Cr-16).

(D) Electron microscopy of a macrophage (m) between a deformed axon (a) and intact myelin. A DRG section from an AMAN rabbit (Cr-16).

Scale bars = 20 µm (A,B); 10 µm (C); 2.5 µm (D).

Discussion

In this study, we showed that IgG antibodies against GM1, GD1a, GD1b, and GT1b can disrupt the nodal and paranodal molecular architecture via the complement pathway. Importantly, nodal disruption was induced in both motor and sensory fibers, providing an explanation for the continuous spectrum of AMAN, AMSAN, and ASAN.

The motor node disruption mediated by anti-GM1 or anti-GD1a antibodies is demonstrated by multiple experimental paradigms, providing basic mechanism for human AMAN pathology (Hafer-Macko et al., 1996) at the molecular level. In ventral roots from AMAN rabbits associated with IgG anti-GM1 antibodies, nodes and paranodes are disrupted by complement-mediated attack (Susuki et al., 2007). A monoclonal IgG antibody reactive with GD1a disrupted nodes in distal motor nerves via the complement pathway in ex vivo and in vivo transfer models (McGonigal et al., 2010), and an intraneural injection model (GD1a/GT1b-2b, present study). However, the results of intraneural injection of anti-GM1 or anti-GD1a antibodies have shown controversial results. For example, by injecting human sera containing IgM anti-GM1 antibodies together with fresh human complement, motor nerve conduction block was induced and immunoglobulin deposition was detected at the nodes (Santoro et al., 1992; Uncini et al., 1993). In contrast, similar experiments failed to induce nerve conduction failure, whereas injected anti-GM1 antibodies bound to the nodes (Harvey et al., 1995). Similarly, in the present study, the monoclonal antibodies to GM1 (GM1-1, GM1-2b) or GD1a (GD1a-1, GD1a-2b) did not cause nodal disruption. Several factors should be considered to interpret this discrepancy. First, the amount of injected antibodies may be limited, because repeated injection of GD1a/GT1b-2b facilitated nodal disruption (present study). Second, GM1 or GD1a in rat sciatic nerve nodes may not be abundant enough, because induction of anti-ganglioside antibody mediated injury depends on the antigen density (Goodfellow et al., 2005). Third, the reactive epitopes of those monoclonal antibodies may be masked by other gangliosides (Greenshelds et al., 2009). Fourth, the affinity of the injected antibodies may not be high enough (Comín et al., 2006). Fifth, the ability of complement activation can be different among each monoclonal antibody (Zhang et al., 2004). Nevertheless, the motor node disruption by injected GD1a/GT1b-2b is clearly described, and further supported by a previous report (McGonigal et al., 2010).

Is the autoimmune nodal disruption responsible tor the development of neurological symptoms? By injecting GD1a/GT1b-2b into wild type sciatic nerves, motor nerve conduction block was induced, confirming previous experiments produced by similar antibody in mutant mice overexpressing GD1a but lacking GT1b (McGonigal et al., 2010). Importantly, the recovery pattern of nerve conduction block induced by GD1a/GT1b-2b was identical to the rapidly reversible conduction failure in human AMAN associated with antibodies to GM1, GD1a, GD1b, or GM1b (for review, see Kokubun et al., 2010). Nerve conduction block can be a result of nodal ionic imbalance due to the formation of bi-directional, non-specific ion and water pores by MAC insertion in the nodal axolemma (McGonigal et al., 2010). Furthermore, reduced numbers of functioning Nav channels in the disrupted nodes, the large leakage of driving current through altered paranodes, and juxtaparanodal potassium channels exposed by paranodal detachment can affect nerve conduction. Indeed, in a single rat myelinated nerve fiber preparation, anti-GM1 antibodies decreased the Na+ current and caused a progressive increase of nonspecific leakage current in the presence of active complement (Takigawa et al., 1995), although this was not confirmed by another group (Hirota et al., 1997). With the clinical course, complement deposition decreases and nodal and paranodal molecules start to be redistributed (Supplementary figure 1; and Susuki et al., 2007), allowing the recovery of nerve conduction. If the autoimmune attack progresses, Wallerian-like degeneration could subsequently develop. The pathophysiological processes in AMAN can vary from early reversible axonal dysfunction to long-lasting axonal degeneration, and these conditions can occur on a continuous spectrum (Kokubun et al., 2010). Taken together, these observations suggest that the complement-mediated nodal disruption is a primary mechanism of motor deficits in AMAN associated with anti-ganglioside antibodies.

Sensory nodes can also be affected by anti-GM1 and anti-GD1a antibodies, although it is less frequent and less severe compared to motor node disruption. In AMAN rabbits, a single immunization protocol of gangliosides induces autoimmune attack of nodes primarily in motor nerves, but occasionally in sensory nerves as well with identical pathological features (Figs. 7,8). Similarly, the anti-GD1a/GT1b antibody caused complement deposition in both motor and sensory nerves, but the nodal component was relatively preserved in sensory nerves (McGonigal et al., 2010; Fig. 1D,E, present study). These results may provide evidence to support the idea that AMAN and AMSAN is part of a spectrum of a single type of immune attack on the axon (Griffin et al., 1996a; Yuki et al., 1999). Indeed, sensory fibers are often involved subclinically in AMAN, and reversible conduction failure is reported in sensory as well as motor fibers in both AMAN and AMSAN (Capasso et al., 2011).

How do the IgG anti-GD1b antibodies cause ASAN? Importantly, rapid resolution of reduced sensory nerve action potentials without conduction slowing has been reported in ASAN patients associated with IgG anti-GD1b antibodies (Pan et al., 2001; Notturno et al., 2008), suggesting the presence of nodal disruption in distal sensory nerves. Here we provide the first evidence for the nodal disruption caused by IgG anti-GD1b antibodies via the complement pathway. Our results strongly suggest the presence of GD1b epitope at nodes in both sensory and motor nerves, although this has not been previously described. Because of the clear description of IgG deposition (Fig. 5), the nodal axolemma in sensory neurons should be a primary autoimmune lesion in ASAN rabbits. Intraneural injection of GD1b-1 (Fig. 4) strongly supports this idea. Furthermore, in dorsal roots in ASAN rabbits, we found periaxonal macrophages (Fig. 6C,D), a histological characteristic found during the acute phase in ventral roots from AMAN (Griffin et al., 1996b) or AMSAN patients (Griffin et al., 1996a) and AMAN rabbits (Susuki et al., 2003; Yuki et al., 2004), and presumably occur subsequent to the nodal disruption (Susuki et al., 2007). The down-regulation of trkC, a neurotrophin-3 receptor (Hitoshi et al., 1999), and the possible subsequent apoptosis of DRG neurons (Takada et al, 2008) have been proposed as pathogenic mechanisms in ASAN rabbits. These changes may occur subsequent to nodal disruption and sensory axon injury. Indeed, trkC in DRG neurons can be down-regulated by sciatic nerve transaction (Bergman et al., 1999), and apoptosis of DRG neurons can be induced by crushing either the nerve root proximal to the DRG or the spinal nerve distal to the DRG (Sekiguchi et al., 2009). Thus, the complement-mediated nodal disruption may be involved in the development of ASAN associated with IgG anti-GD1b antibodies.

Taken together, we propose that complement-mediated nodal disruption is a central mechanism common to the acute immune-mediated neuropathies associated with antibodies to GM1, GD1a, GD1b, and GT1b. Traditionally, the mechanisms of neuropathies are considered to be either myelin or the axon defects. Our findings clearly indicate that the nodes can be exclusively damaged by autoimmune processes, resulting in development of neuropathies. These results further emphasize the importance of the nodes of Ranvier for proper neuronal function, and that their dysfunction is directly associated with neurological disorders. Complement inhibitors or calpain inhibitors may be promising candidate drugs to attenuate the disease process induced by IgG anti-GM1 or -GD1a antibodies (Phongsisay et al., 2008; McGonigal et al., 2010). Our results suggest that these drugs may also be potentially useful for treatment of ASAN associated with IgG anti-GD1b antibodies.

Highlights.

-

►

Anti-ganglioside antibodies are found in neuropathies, AMAN, AMSAN, or ASAN.

-

►

Anti-GD1a antibody disrupts nodes of Ranvier and induces nerve conduction block.

-

►

Anti-GD1b antibodies disrupt nodes in sensory nerves and cause ataxia.

-

►

Anti-GM1 antibodies attack primarily motor but occasionally sensory nodes as well.

-

►

Nodal disruption may be a common mechanism in AMAN, AMSAN, and ASAN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS044916 (to M.N.R.) and NS42888 (to Dr. Kazim A. Sheikh, Department of Neurology, University of Texas Medical School at Houston). We thank H. Fujita, C. Yanaka, Y. Nishimoto, C. Yamanaka, and K. Yamaguchi (Dokkyo Medical University) for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AMAN

acute motor axonal neuropathy

- AMSAN

acute motor-sensoty axonal neuropathy

- ASAN

acute sensory ataxic neuropathy

- Caspr

contactin-associated protein

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- CMAP

compound muscle action potential

- DRG

dorsal root ganglions

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- MCV

motor nerve conduction velocity

- Nav

voltage-gated sodium

- P/D

proximal/distal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Berghs S, Aggujaro D, Dirkx R, Jr, Maksimova E, Stabach P, Hermel JM, Zhang JP, Philbrick W, Slepnev V, Ort T, Solimena M. βIV spectrin, a new spectrin localized at axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier in the central and peripheral nervous system. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:985–1001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman E, Fundin BT, Ulfhake B. Effects of aging and axotomy on the expression of neurotrophin receptors in primary sensory neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;410:368–386. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990802)410:3<368::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso M, Notturno F, Manzoli C, Uncini A. Involvement of sensory fibres in axonal subtypes of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011;82:664–670. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.238311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J, Negredo P, Avendaño C. Fiber composition of the rat sciatic nerve and its modification during regeneration through a sieve electrode. Brain Res. 2008;1190:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comín R, Yuki N, Lopez PH, Nores GA. High affinity of anti-GM1 antibodies is associated with disease onset in experimental neuropathy. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;84:1085–1090. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Tagawa Y, Lunn MP, Laroy W, Heffer-Lauc M, Li CY, Griffin JW, Schnaar RL, Sheikh KA. Localization of major gangliosides in the PNS: implications for immune neuropathies. Brain. 2002;125:2491–2506. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow JA, Bowes T, Sheikh K, Odaka M, Halstead SK, Humphreys PD, Wagner ER, Yuki N, Furukawa K, Furukawa K, Plomp JJ, Willison HJ. Overexpression of GD1a ganglioside sensitizes motor nerve terminals to anti-GD1a antibody-mediated injury in a model of acute motor axonal neuropathy. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1620–1628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4279-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenshields KN, Halstead SK, Zitman FM, Rinaldi S, Brennan KM, O'Leary C, Chamberlain LH, Easton A, Roxburgh J, Pediani J, Furukawa K, Furukawa K, Goodyear CS, Plomp JJ, Willison HJ. The neuropathic potential of anti-GM1 autoantibodies is regulated by the local glycolipid environment in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:595–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI37338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JW, Li CY, Ho TW, Tian M, Gao CY, Xue P, Mishu B, Cornblath DR, Macko C, McKhann GM, Asbury AK. Pathology of the motor-sensory axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1996a;39:17–28. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JW, Li CY, Macko C, Ho TW, Hsieh ST, Xue P, Wang FA, Cornblath DR, McKhann GM, Asbury AK. Early nodal changes in the acute motor axonal neuropathy pattern of the Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Neurocytol. 1996b;25:33–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02284784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafer-Macko C, Hsieh ST, Li CY, Ho TW, Sheikh K, Cornblath DR, McKhann GM, Asbury AK, Griffin JW. Acute motor axonal neuropathy: an antibody-mediated attack on axolemma. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:635–644. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey GK, Toyka KV, Zielasek J, Kiefer R, Simonis C, Hartung HP. Failure of anti-GM1 IgG or IgM to induce conduction block following intraneural transfer. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:388–394. doi: 10.1002/mus.880180404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota N, Kaji R, Bostock H, Shindo K, Kawasaki T, Mizutani K, Oka N, Kohara N, Saida T, Kimura J. The physiological effect of anti-GM1 antibodies on saltatory conduction and transmembrane currents in single motor axons. Brain. 1997;120:2159–2169. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.12.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitoshi S, Kusunoki S, Murayama S, Tsuji S, Kanazawa I. Rabbit experimental sensory ataxic neuropathy: anti-GD1b antibody-mediated trkC downregulation of dorsal root ganglia neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;260:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Matsuno K, Sakumoto Y, Hirata K, Yuki N. Ataxic Guillain-Barré syndrome and acute sensory ataxic neuropathy form a continuous spectrum. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011;82:294–299. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.222836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida K, Ariga T, Yu RK. Antiganglioside antibodies and their pathophysiological effects on Guillain-Barré syndrome and related disorders-a review. Glycobiology. 2009;19:676–692. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokubun N, Nishibayashi M, Uncini A, Odaka M, Hirata K, Yuki N. Conduction block in acute motor axonal neuropathy. Brain. 2010;133:2897–2908. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki S, Shimizu J, Chiba A, Ugawa Y, Hitoshi S, Kanazawa I. Experimental sensory neuropathy induced by sensitization with ganglioside GD1b. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:424–431. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez PH, Zhang G, Bianchet MA, Schnaar RL, Sheikh KA. Structural requirements of anti-GD1a antibodies determine their target specificity. Brain. 2008;131:1926–1939. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn MP, Johnson LA, Fromholt SE, Itonori S, Huang J, Vyas AA, Hildreth JE, Griffin JW, Schnaar RL, Sheikh KA. High-affinity anti-ganglioside IgG antibodies raised in complex ganglioside knockout mice: reexamination of GD1a immunolocalization. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:404–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal R, Rowan EG, Greenshields KN, Halstead SK, Humphreys PD, Rother RP, Furukawa K, Willison HJ. Anti-GD1a antibodies activate complement and calpain to injure distal motor nodes of Ranvier in mice. Brain. 2010;133:1944–1960. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notturno F, Caporale CM, Uncini A. Acute sensory ataxic neuropathy with antibodies to GD1b and GQ1b gangliosides and prompt recovery. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:265–268. doi: 10.1002/mus.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan CL, Yuki N, Koga M, Chiang MC, Hsieh ST. Acute sensory ataxic neuropathy associated with monospecific anti-GD1b IgG antibody. Neurology. 2001;57:1316–1318. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phongsisay V, Susuki K, Matsuno K, Yamahashi T, Okamoto S, Funakoshi K, Hirata K, Shinoda M, Yuki N. Complement inhibitor prevents disruption of sodium channel clusters in a rabbit model of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Neuroimmunol. 2008;205:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaglia V, Daha MR, Baas F. The complement system in the peripheral nerve: friend or foe? Mol. Immunol. 2008;45:3865–3877. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband MN, Peles E, Trimmer JS, Levinson SR, Lux SE, Shrager P. Dependence of nodal sodium channel clustering on paranodal axoglial contact in the developing CNS. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7516–7528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07516.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro M, Uncini A, Corbo M, Staugaitis SM, Thomas FP, Hays AP, Latov N. Experimental conduction block induced by serum from a patient with anti-GM1 antibodies. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:385–390. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Bansal R, Hedstrom KL, Pfeiffer SE, Rasband MN. Does paranode formation and maintenance require partitioning of neurofascin 155 into lipid rafts? J. Neurosci. 2004;24:3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5427-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaar RL, Fromholt SE, Gong Y, Vyas AA, Laroy W, Wayman DM, Heffer-Lauc M, Ito H, Ishida H, Kiso M, Griffin JW, Shiekh KA. Immunoglobulin G-class mouse monoclonal antibodies to major brain gangliosides. Anal. Biochem. 2002;302:276–284. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi M, Sekiguchi Y, Konno S, Kobayashi H, Homma Y, Kikuchi S. Comparison of neuropathic pain and neuronal apoptosis following nerve root or spinal nerve compression. Eur. Spine J. 2009;18:1978–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1064-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh KA, Zhang G, Gong Y, Schnaar RL, Griffin JW. An anti-ganglioside antibody-secreting hybridoma induces neuropathy in mice. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:228–239. doi: 10.1002/ana.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susuki K, Nishimoto Y, Yamada M, Baba M, Ueda S, Hirata K, Yuki N. Acute motor axonal neuropathy rabbit model: immune attack on nerve root axons. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:383–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.33333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susuki K, Nishimoto Y, Koga M, Nagashima T, Mori I, Hirata K, Yuki N. Various immunization protocols for an acute motor axonal neuropathy rabbit model compared. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;368:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susuki K, Rasband MN, Tohyama K, Koibuchi K, Okamoto S, Funakoshi K, Hirata K, Baba H, Yuki N. Anti-GM1 antibodies cause complement-mediated disruption of sodium channel clusters in peripheral motor nerve fibers. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:3956–3967. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4401-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susuki K, Rasband MN. Molecular mechanisms of node of Ranvier formation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008;20:616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K, Shimizu J, Kusunoki S. Apoptosis of primary sensory neurons in GD1binduced sensory ataxic neuropathy. Exp. Neurol. 2008;209:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa T, Yasuda H, Kikkawa R, Shigeta Y, Saida T, Kitasato H. Antibodies against GM1 ganglioside affect K+ and Na+ currents in isolated rat myelinated nerve fibers. Ann. Neurol. 1995;37:436–442. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uncini A, Santoro M, Corbo M, Lugaresi A, Latov N. Conduction abnormalities induced by sera of patients with multifocal motor neuropathy and anti-GM1 antibodies. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:610–615. doi: 10.1002/mus.880160606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn PA, Ruts L, Jacobs BC. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:939–950. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki N, Kuwabara S, Koga M, Hirata K. Acute motor axonal neuropathy and acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy share a common immunological profile. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999;168:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki N, Yamada M, Koga M, Odaka M, Susuki K, Tagawa Y, Ueda S, Kasama T, Ohnishi A, Hayashi S, Takahashi H, Kamijo M, Hirata K. Animal model of axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome induced by sensitization with GM1 ganglioside. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:712–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki N, Susuki K, Koga M, Nishimoto Y, Odaka M, Hirata K, Taguchi K, Miyatake T, Furukawa K, Kobata T, Yamada M. Carbohydrate mimicry between human ganglioside GM1 and Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide causes Guillain-Barré syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11404–11409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402391101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Lopez PH, Li CY, Mehta NR, Griffin JW, Schnaar RL, Sheikh KA. Anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated neuronal cytotoxicity and its protection by intravenous immunoglobulin: implications for immune neuropathies. Brain. 2004;127:1085–1100. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.