Abstract

Both central and peripheral axons contain pivotal microRNA (miRNA) proteins. While recent observation demonstrated that miRNA biosynthetic machinery responds to peripheral nerve lesion in an injury-regulated pattern, the physiological significance of this phenomenon remains to be elucidated. In the current paper we hypothesized that deletion of Dicer would disrupt production of Dicer-dependent miRNAs and would negatively impact regenerative axon growth. Taking advantage of tamoxifen-inducible CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl knockout (Dicer KO), we investigated the results of Dicer deletion on sciatic nerve regeneration in vivo and regenerative axon growth in vitro. Here we show that the sciatic functional index, an indicator of functional recovery, was significantly lower in Dicer KO mice in comparison to wild-type animals. Restoration of mechanical sensitivity recorded in the von Frey test was also markedly impaired in Dicer mutants. Further, Dicer deletion impeded the recovery of nerve conduction velocity and amplitude of evoked compound action potentials in vitro. Histologically, both total number of regenerating nerve fibers and mean axonal area were notably smaller in the Dicer KO mice. In addition, Dicer-deficient neurons failed to regenerate axons in dissociated dorsal root ganglia (DRG) cultures. Taken together, our results demonstrate that knockout of Dicer clearly impedes regenerative axon growth as well as anatomical, physiological and functional recovery. Our data suggest that the intact Dicer-dependent miRNA pathway is critical for the successful peripheral nerve regeneration after injury.

Keywords: miRNA, Dicer, sciatic nerve, axonogenesis, axon growth, regeneration

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important molecular switches which play a major role in post-transcriptional gene regulation (Jackson, et al., 2010). Pri-miRNAs are initially processed by biosynthetic enzymes, Drosha and DGCR8/Pasha, while in cytoplasm RNAse III enzyme Dicer cleaves pre-miRNAs into the mature miRNAs (Bernstein, et al., 2001, Lee, et al., 2003). Dicer plays a critical part in the miRNA biosynthetic pathway and the system wide ablation of Dicer in mice results in early embryonic lethality (Bernstein, et al., 2003). Therefore, to investigate the role of miRNAs in the nervous system many groups have used Cre-mediated recombination systems to ablate Dicer in a tissue or developmentally specific manner (Cuellar, et al., 2008). Studies show that during early development, the deletion of Dicer in the neural crest (NC) lineage leads to the cell loss in enteric, sensory, and sympathetic nervous systems (Zehir, et al., 2010). During the late embryonic stage cortical-specific Dicer conditional knockout affects survival and differentiation of cortical neural progenitors resulting in the abnormal migration of neurons in the cortex as examined at E 18.5 (Kawase-Koga, et al., 2009). Postnatally, conditional loss of Dicer in excitatory forebrain neurons disrupts cellular morphogenesis, resulting in an array of phenotypes including microcephaly, reduced dendritic branch elaboration, and increased cortical apoptosis (Davis, et al., 2008). Loss of Dicer in dopaminoceptive neurons is associated with ataxia, reduced brain size, and decreased lifespan to 10–12 weeks (Cuellar, et al., 2008). Similarly, conditional inactivation of Dicer in Purkinje cells leads to relatively rapid disappearance of Purkinje cell-expressed miRNAs, followed by a slow cerebellar degeneration and development of ataxia between 13 to 17 week of age (Schaefer, et al., 2007).

Thus while these data strongly suggest an indispensible role of miRNAs during neural development and maturation in the CNS, little information is available on the role of miRNAs in the adult PNS. Although no reports have directly linked miRNA regulation with peripheral nerve physiology, recent observations show that loss of Dicer in Schwann cells may arrest Schwann cell differentiation (Bremer, et al., 2010), alter myelin-related gene expression (Pereira, et al., 2010), and cause a severe neurological phenotype resembling congenital hypomyelination (Yun, et al., 2010). Interestingly, components of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and mRNA-processing bodies (P-bodies), which are the local foci of mRNA degradation, have been detected in severed sciatic nerve fibers and regenerating dorsal root ganglia (DRG) axons in vitro (Hengst, et al., 2006, Murashov, et al., 2007, Wu, et al., 2011). In addition, a comprehensive list of miRNAs residing within the distal axonal domain of superior cervical ganglia has recently been reported (Natera-Naranjo, et al., 2010). Thus, current observations suggest that miRNAs may play an important regulatory role in peripheral nerve health even after development.

In the current study we asked whether the genetic ablation of Dicer would affect peripheral nerve regeneration. Taking advantage of tamoxifen-inducible CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl knockout mice (Dicer KO), we investigated the results of Dicer deletion on sciatic nerve regeneration in vivo and regenerative axon growth in vitro. Here we show that deletion of Dicer impaired nerve regeneration according to functional behavioral tests, electrophysiological and histological analyses. In addition, Dicer-deficient neurons failed to regenerate axons in dissociated dorsal root ganglia (DRG) cultures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that the intact Dicer-dependent miRNA pathway is necessary for the successful functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury in adult animal

MATERIALS and METHODS

Animals, injections, and surgery

Animals were housed individually under standard laboratory conditions, with a 12 h light/dark schedule and unlimited access to food and water. All experimental procedures followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of East Carolina University, an AAALAC-accredited facility.

Breeding pairs of CAG-CreERt and Dicerfl/fl mice were provided by Dr. Tatsuya Kobayashi as a generous gift (Kobayashi, et al., 2008). The offspring, CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice carried a homozygous allele of floxed Dicer gene (Dicerfl/fl ) and heterozygous transgene insert CAG-CreERt that contained Cre recombinase with a mutant mouse estrogen receptor ligand binding domain. By breeding CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice, we obtained CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice and Dicerfl/fl littermates. Genotypes were determined by PCR using genomic DNA derived from tail biopsies.

To induce the deletion of Dicer, 8-wk-old CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at the dose of 0.1mg/g body weight for five consecutive days (Kobayashi, et al., 2008). These animals were hereafter called Dicer KO (Dicer KO) mice in this study. Sesame oil (Sigma) with ethanol (EMD Chemicals Inc., Gibbstown, NJ) (3.75%) solution was used as vehicle to dissolve tamoxifen. CAG-CreERt: Dicerfl/fl mice with vehicle treatment (hereafter called vehicle treated group) and Dicerfl/fl mice with tamoxifen treatment (hereafter called no-Cre group) were used as controls in this study. All animals were normal at birth, exhibiting normal weight and weaning behavior as compared with control littermates. At 8 weeks, (beginning of tamoxifen treatment,) heterozygous mutant mice were viable, normal in size, and did not display any physical or behavioral abnormalities (data not shown).

Five days after the tamoxifen or oil treatment, Dicer KO and control animals were subjected to sciatic nerve crush. Before surgery, animals were anesthetized with ketamine (18 mg/ml)-xylazine (2 mg/ml) anesthesia (0.05 ml/10g body weight, i.p). Exposure of the right sciatic nerve was performed with sterile surgical instruments through an incision on the middle thigh of the right hind limb. Approximately 5 mm of nerve was exposed from the sciatic notch to the trifurcation of the nerve. The exposed sciatic nerve was crushed in the mid-thigh for 15 sec with a fine hemostat. The wound was closed with 3M™ Vetbond™ Tissue Adhesive (3M, St. Paul, MN) and the recovery of sciatic nerve was monitored for 3 weeks.

X-gal staining of sciatic nerves

5 days after tamoxifen or vehicle treatment, 5 mice were randomly selected from each group, and around 1 cm of sciatic nerve was dissected from 3 groups of mice. Sciatic nerves were first fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS with Magnesium Chloride (2mM) on ice for 30 minutes, and then rinsed in 3 changes of PBS. X-gal stock (Sigma) was diluted into X-gal reaction buffer and was incubated with the tissue for 2–4 hours at 37°C. The sciatic nerves were rinsed in PBS until the solution ran clear. The activity of β-galactosidase was checked under bright-field optics.

Western blot analysis

Proteins for western blotting were extracted from pooled sciatic nerves (n=6 for each group at each time point) and quantified with the BioRad reagent (BioRad, Hercules, CA). 20 µg of solubilized proteins were loaded per lane on sodium dodecyl sulfate gels and separated by SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were then transferred to immobilon P membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR, Nebraska, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature on a shaker, and then probed with primary antibody against Dicer (Abcam, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. After washing, membranes were incubated in IRDye® conjugated secondary antibodies for one hour at room temperature with gentle shaking. The fluorescence signals on membrane were detected with the Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from pooled sciatic nerves (n=6 for each group at each time point) after tamoxifen or vehicle treatment with RNAqueous-Micro Micro Scale RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with NCode™ VILO™ miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit and SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Town, CA). The real-time PCR reactions were carried out using EXPRESS SYBER® GreenER™ qPCR SuperMix Universal (Invitrogen) in triplicates for each cDNA sample in the presence of mouse gene-specific primers for Dicer (Forward: 5’-AGTGTAGCCTTAGCCATTTGC-3’; Reverse: 5’-CTGGTGGCTTGAGGACAAGAC-3’). Primers for miRNA qPCR include miR-199a (5’-ACAGTAFTCTGCACTTGGTTA-3’), miR-21 (5’-TAGCTTATCAGACTGATGTTGA-3’), miR142-5p(5’-CATAAAGTAGAAAGCACTACTAAAA-3’) and miR-9 (5’-TCTTTGGTTATCTAGCTGTTGA-3’) and a universal Primer supplied with the NCode™ VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kits (Invitrogen). Relative quantitation of gene and miRNA expressions were normalized against the reference gene S12 using a −ΔΔCT method (Paz, et al., 2007). All experiments were carried out three times independently.

Analyses of functional recovery

Functional motor recovery

Functional recovery of motor function after sciatic nerve crush was analyzed using a walking track assessment, and quantified with the sciatic functional index (SFI). Paw prints were recorded by painting the hind paws with black ink and having the animals walk along an 8×40 cm corridor lined with a white paper. The toe spread and the paw length were measured from those prints to calculate SFI (McMurray, et al., 2003). The resulting SFI was calculated according to the formula described as:

where ETS represented experimental toe spread, NTS represented normal toe spread, EPL represented experimental paw length, and NPL represented normal paw length. The value of SFI ranges from −100 to 0. A SFI close to zero suggests normal nerve function or completely recovery of nerve function, and a value of −100 indicates total loss of function. The walking corridor analysis was performed on animals before crush injury as baseline tests, and at 2, 4, 7, 14, and 21 days after injury.

Mechanical sensitivity test

Mechanical sensitivity (allodynia) was studied with the von Frey test. Filaments with stimulus intensities ranging from 0.08–10 grams were applied to the glabrous skin of each hind paw eight times while the animal stood on an elevated screen. Before testing, a 15 min quiescent period was allowed. Filaments were applied to the point of bending, at which time substantiation of response or non-response was determined. Responses included hind paw withdrawal and orientation toward the stimulus. During each test session, the filament that produced a threshold response (response to over 4 out of 8 stimuli) in each animal was documented for both the left and right hind paws (Okada, et al., 2002). Raw data measurements were recorded as stimulus intensities required to elicit a threshold response and subsequently normalized to baseline values.

Electrophysiological analyses on isolated sciatic nerves

Electrophysiological approaches were used to assess the effects of Dicer deletion on nerve conduction velocity (NCV) and compound action potential (CAP) amplitude of the regenerating sciatic nerve, at 14 and 21 d after injury. Mice were euthanized by decapitation under deep anesthesia with ketamine (18 mg/ml)-xylazine (2 mg/ml), and sciatic nerves from injured and contralateral uninjured side were dissected from the ankle to the spinal column at a length of ~ 20 mm and immediately placed in Locke solution (154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM dextrose, 2 mM HEPES, pH 7.2), equilibrated to room temperature. Nerve segments were straightened and fixed in a slightly stretched position by pinning the two ends to the bottom of a Sylgard-lined dissecting dish. After removing all connective tissues from the nerves, glass suction electrodes were gently attached to the nerves, proximal and distal to the site of the injury, usually ~ 2 cm apart and bracketing the injury site by ~ 1cm. The proximal site was stimulated with a series of 10 constant-current pulses of 500 µA and 100 µs, at intervals of 2 s, to achieve a maximal and stable peak CAP response recorded at the distal side. To minimize the size of the stimulus artifact and maximize the size of the CAP signal, the diameters of the suction electrode were fabricated to match the diameter of the sciatic nerve. Signals were recorded, amplified with a 4-channel extracellular amplifier (AM Systems, Model 1700, Sequim, WA), and digitized with a Digidata 1322A using pClamp 10 software (both: Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were subsequently analyzed offline with pClamp and SigmaPlot (Version 11, Systat, San Jose, CA) software. In short, signal responses from injured nerves were rectified and the calculated integrals of these responses were measured against control epochs of identical duration from intact controls. Comparisons were made between the averaged amplitudes of ten consecutive responses measured between injured and un-injured sides at each time point.

Histological evaluation

Semi-thin sections of sciatic nerves were prepared to visualize the re-myelinated axons. The lesioned portions of the sciatic nerves were fixed with cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed with 1% osmium tetraoxide solution, dehydrated stepwise in increasing concentrations of ethanol, embedded with Low Viscosity Embedding Media Spurr's Kit (EMS, Hatfield, PA), and cut into transverse sections. Transverse semi-thin sections (1 µm thick) were stained with Richardson's solution. The number of myelinated axons was counted under bright field microscope at magnification of 40X. The myelinated axon area was quantified at 40X magnification using the NIH ImageJ software package, as described previously (McMurray, et al., 2003).

Dissociated DRG neuronal cell culture

The regenerative axon growth was studied in vitro in dissociated cultures of L4/5 DRG neurons collected 5 days after conditioning sciatic nerve crush. DRGs were dissociated with collagenase (0.2 mg/ml) and 0.25% trypsin in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA). The dissociated DRGs were plated on poly-L-Lysine and laminin- coated plates. DRGs were grown in DMEM/F12 media containing 10% horse serum, L-glutamine and N2 supplement (Gemini Bio-product, West Sacramento, CA) with 50 nM glial cell inhibitor 5-Fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (Sigma) at 37° C for 18 hrs.

Administration of 4-hydroxytamixifen to primary DRG cultures

DRGs were collected from conditionally lesioned CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl and from Dicerfl/fl mice, dissociated and plated as describe above. 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO with sonication to obtain 1 µM stock solution, which was applied to DRG cultures in a final concentration of 1 nM overnight. DRGs isolated from Dicerfl/fl mice and cultured with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (negative control) were designated as no-Cre group. Correspondingly, DRG neurons collected from CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice and treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen were called Dicer KO group.

Immunofluorescent staining and image analyses

The effect of the Dicer KO on regenerative axon growth was studied by assessing axonal elongation and branching- arborization. After overnight culturing of lumbar DRGs on coverslips, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and washed with PBST. After blocking with 10% goat serum for 1 hour at room temperature, the cultures were incubated with primary antibodies against TUJ1 (Covance, Princeton, NJ, 1:100) overnight at 4 °C and secondary anti-mouse Texas Red conjugated antibody (Jackson ImmunoReserch Lab, West Grove, PA, 1:100) for one hour. After mounting the slides, images were viewed with an Olympus IMT-2 fluorescent microscope. Images were recorded using the Spot digital camera system (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and measured with NIH ImageJ software.

Quantification of axon length and measurement of axon branches were performed following previously described lab protocol (Murashov, et al., 2005). For each coverslip, 30 images were taken, and from each, 10–15 neurons, which were completely distinguishable from neighboring cells, were chosen for further analysis. The axon length was quantified by tracing the image of neurites with the ImageJ software. The longest axon for each neuron was measured and recorded. The number of neurites branches per neuron was also determined from each neuronal population manually. Only branches longer than one cell body in length were counted (Liu, et al., 2002).

Statistic analyses

The results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean in graphic and text representations. The difference between 3 groups (CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice with tamoxifen treatment, CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice with vehicle treatment, and Dicerfl/fl mice with tamoxifen treatment) at each time point were evaluated with one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism version 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software; San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Tamoxifen treatment induced Dicer gene knockout in sciatic nerve

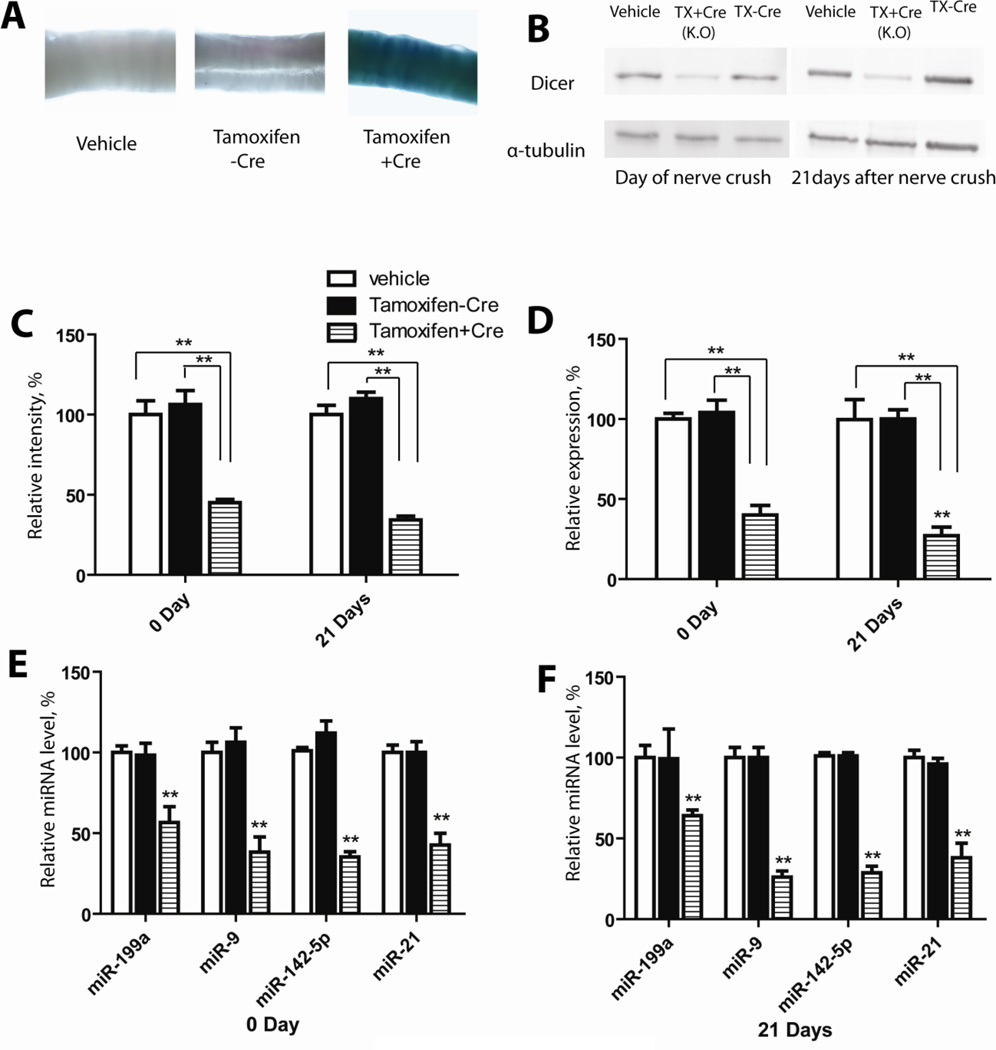

To confirm that tamoxifen treatment could activate Cre expression and result in Dicer KO, we used a ROSA26 Cre reporter gene. All animals carried ROSA26 stop/flox locus annexed to a lazZ reporter, in which lazZ expression was conditional upon the removal of the floxed stop codon. When Cre recombinase was expressed, it excised the genomic region between the two loxP sites, allowing expression of lazZ. The breeding pairs of CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl were heterozygous for Cre alleles. Correspondingly, their offspring genotype was either CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl, or Dicerfl/fl. X-gal staining for sciatic nerves from those offspring showed that only the CAG-CreERt: Dicerfl/fl mice treated with tamoxifen exhibited blue tissue staining. For the other two control groups of mice neither the CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice with vehicle treatment nor the Dicerfl/fl littermates with tamoxifen administration showed any staining in their tissues (Fig. 1A). These results confirmed that tamoxifen treatment successfully activated Cre recombinase in CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice. CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice receiving vehicle injection and Dicerfl/fl mice receiving tamoxifen treatment lacked Cre expression, and therefore, had no lacZ expression.

Figure 1. Cre activation induces loss of Dicer in CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice.

Tamoxifen treatment of CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice activated Cre recombinase, under the control of the estrogen promoter. A, Cre activation was assessed by X-gal staining of sciatic nerves. LacZ expression was not observed in two control groups: vehicle treated CAG-CreERt: Dicerfl/fl mice (left) and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice (middle). X-gal staining was obvious in sciatic nerve of tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice (right). B, Western blot shows successful depletion of Dicer in sciatic nerve. Sciatic nerves were collected from 3 groups of mice (Tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice, vehicle treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice, and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice) at both the day of sciatic nerve crush surgery and 21 days after nerve crush. C, Protein levels of Dicer were quantified by band densitometry and normalized to α-tubulin level. D, Decrease in Dicer expression at mRNA level in pooled samples of sciatic nerves after tamoxifen treatment measured by Real-Time qPCR. E, F, Real-Time qPCR confirmed declined levels of selected miRNAs after Cre induced Dicer ablation at day 0 (E) and day 21(F) after nerve crush. (**p<0.01)

The ablation of Dicer expression after tamoxifen treatment in CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice was assessed by western blot analysis. Sciatic nerves were collected both at the day of nerve crush and 21 days after nerve injury. Western blot data gave the evidence that at both time points, there was a significant decrease in the Dicer expression at the protein level in Dicer KO group (Fig. 1B). On the day of nerve crush, Dicer expression in the sciatic nerve was down-regulated to 42±2.09% of the vehicle treated group level. At 21 days after nerve crush, Dicer expression in the knockout group was decreased to 32±2.33% of the vehicle treated group level, possibly reflecting over time depletion of Dicer protein pool (Fig. 1C).

To confirm these data at the mRNA level, tissue samples were collected from 3 groups of mice at 2 different time points, and total RNA was isolated from sciatic nerves. Quantification of 3 independent RT-qPCR experiments revealed that, tamoxifen treatment reduced Dicer mRNA levels to 40±6.11% and 27±5.31% in sciatic nerve at day 0 and day 21 respectively (Fig. 1D), when compared to two controls. Since Dicer is a key enzyme in the microRNA biogenesis pathway, we used RT-qPCR to determine the effect of Dicer deletion on microRNA expression. The expression levels of the following 4 different miRNAs, miR-199a, miR-21, miR-142-5p and miR9, were significantly down regulated (Fig. 1E, F) following inducible Dicer deletion. At day 0, the expression levels of miR-199a, miR-21, miR-142-5p and miR-9 were reduced to 64±3.51 %, 42.67±7.27%, 35.33±3.18%, and 38.33±9.39% respectively in comparison with the control groups, and at day 21, the expression levels of miR-199a, miR-21, miR-142-5p and miR-9 were reduced to 56.67±9.77, 38±9.07%, 28.67±4.10%, and 26±3.78%, respectively. These results confirmed that Cre activation induced by tamoxifen treatment in CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice led to the ablation of Dicer and marked loss of miRNAs expression in the nervous system.

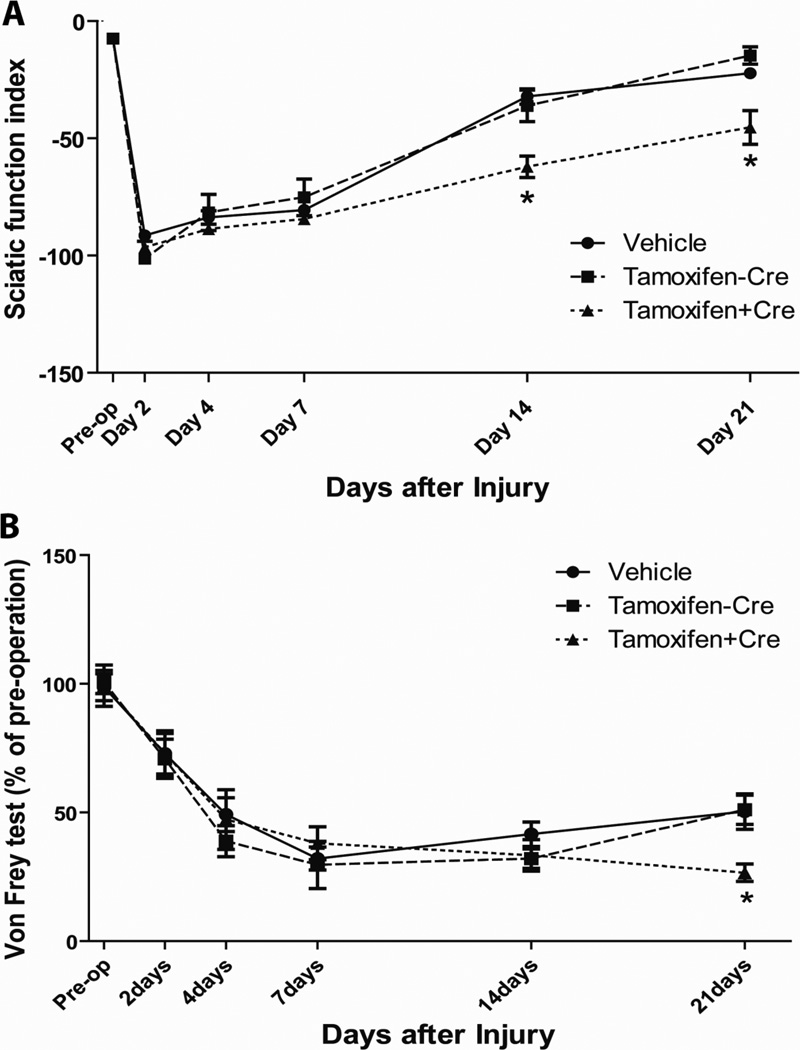

Dicer deletion delayed functional recovery in walking corridor test

In order to determine the effect of miRNA depletion on the recovery of motor function, we performed a walking corridor behavioral test (N=20 for each group). As shown in Fig 2A, during the baseline test, the SFI was normal (close to zero) for 3 groups of mice before sciatic nerve crush. Two days after nerve crush, the values of SFI were close to −100 (vehicle control group: −91.51±2.83; no-Cre control group: −102.4±2.70; Dicer KO group: −96.80±2.69) in all three groups of the mice. The SFI was recovering during the observation period of three weeks. At earlier time points, there were no significant differences between the Dicer KO group and two control groups (Day 4: vehicle control group: −84.45±3.29; no-Cre control group: −78.27±7.54; Dicer KO group: −88.75±2.43. Day7: vehicle control group: −82.23±2.43; no-Cre control group: −70.27±2.70; Dicer KO group: −84.54±2.20). However, although the trends for the development of SFI were similar for the 3 groups of mice, the SFI values of Dicer KO were slightly lagging behind. The SFI values for Dicer KO group at day 14 and day 21 after injury became significantly lower (P<0.05) than those of two control groups (Day 14: vehicle control group: −34.71±3.78; no-Cre control group: −25.49±6.93; Dicer KO group: −61.00±5.38. Day21: vehicle control group: 24.56±2.22; no-Cre control group: −14.07±4.71; Dicer KO group: −43.53±7.49.). It should be noted that, at day 21, the SFI value of the no-Cre control group resembled the pre-operation level, whereas the SFI value of the Dicer KO group was still significantly lower than pre-operation level. Thus, the data demonstrated that loss of Dicer resulted in a slower recovery of motor function.

Figure 2. Behavioral tests reflect impaired restoration of sensory and motor function in Dicer KO.

A, Sciatic functional index (SFI) ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) shows the recovery of motor function from sciatic nerve crush with/without Dicer deletion over the course of time. Tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice (Dicer KO) demonstrated delayed recovery compared to vehicle treated animals and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice. The difference between SFI reached statistical significance at day 14 and day 21. (N=20, * p<0.05). B, von Frey test assessed mechanical sensitivity at 2, 4, 7, 14, and 21 days after nerve injury. All data were normalized to pre-injury baseline level. At 21 days post-injury, the threshold to mechanical stimuli was significantly lower in the Dicer KO group. (N=15, * p<0.05). Tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice are represented by dot lines, tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice are represented by dashed lines, and vehicle treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice are represented by full lines.

Dicer deletion resulted in a delayed recovery from allodynia

In our experiments, we used the von Frey test to assess pre-injury mechanical sensitivity and the injury-induced changes in mechanical sensitivity following Dicer deletion (N=15 for each group). Two pre-injury tests were used to determine the baseline value and the tests to evaluate the recovery of the sensory function were conducted 2, 4, 7, 14, and 21 days after injury. Following sciatic nerve injury, mice typically became hypersensitive and responded to filaments of lesser intensities, indicating the presence of mechanical allodynia (Vogelaar, et al., 2004). In our experiments, the decrease in the threshold was observed at the first post-injury behavioral test and progressed with time (Fig. 2B). During the second week after injury, mice in the two control groups showed signs of recovery from allodynia. From day 7 to day 14, the sensory threshold of the control animals increased from 32.09±4.5% to 41.56±4.73% of pre-operation levels, whereas the Dicer KO further decreased their thresholds to mechanical stimuli, from 38.01±6.4% to 33.33±6.07% of pre-operation level. On the last day of the observation periods (Day 21), there were significant differences in the sensory thresholds between control groups and Dicer KO group (vehicle control group: 50.34±6.92; no-Cre control group: −51.03±5.71; Dicer KO group: −26.57±3.36, P<0.05, N=15). Thus, the significantly lower mechanical withdrawal thresholds in Dicer KO at Day 21 indicated the delayed recovery from allodynia.

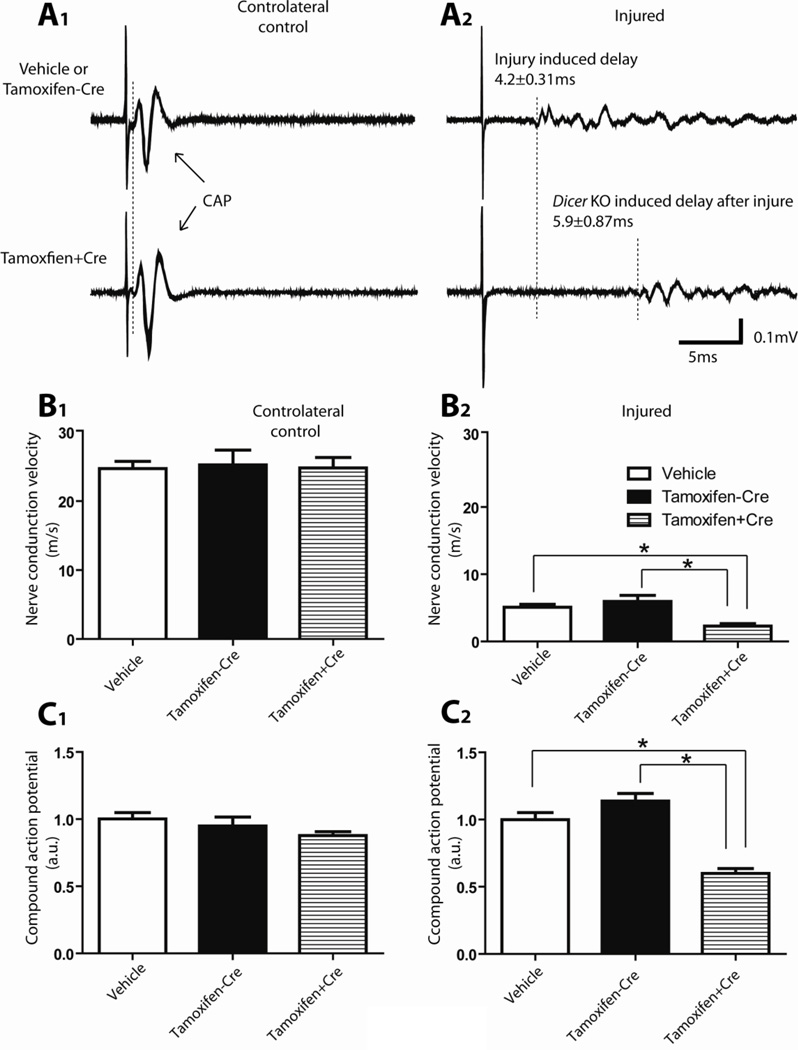

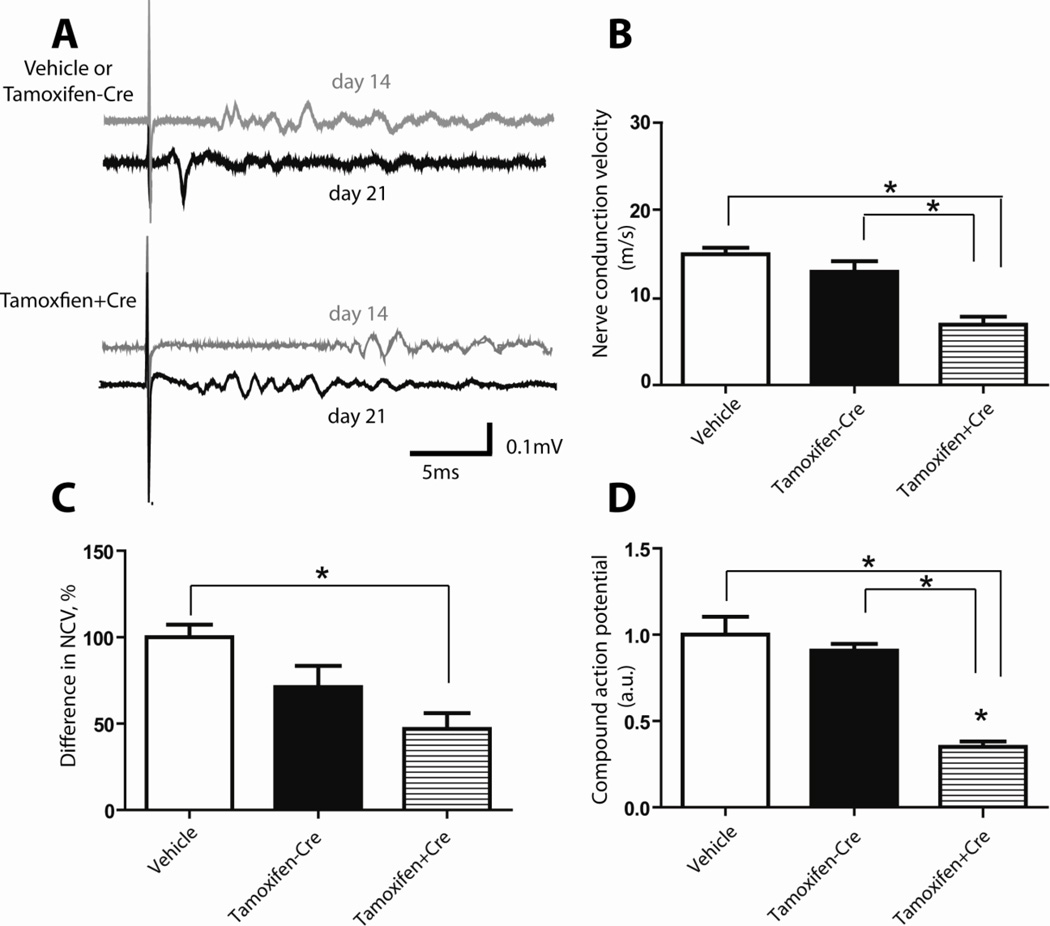

Electrophysiological evaluation of sciatic nerve regeneration

The electrophysiological assessments, performed at 14 days and 21 days after nerve crush, provided further evidence for the delayed physiological recovery of crushed sciatic nerve in Dicer KO animals. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) decreased after crush and then was restored upon the regeneration of nerve fibers (Fig. 3 and 4). At both 14 (Fig. 3B) and 21 (Fig. 4B) days after injury, NCV was significantly slower in Dicer KO group compared with controls (Day 14: vehicle control group: 5.10±0.43 m/s ; no-Cre control group: 5.96±0.89 m/s; Dicer KO group: 2.28±0.38 m/s (Fig. 3 B2). Day 21: vehicle control group: 15.14±0.74 m/s; no-Cre control group: 13.1±1.23 m/s; Dicer KO group: 6.40±0.83 m/s. N=5, P<0.05 (Fig. 4B)). The increase of NCV from day 14 to day 21 was also significantly smaller in Dicer KO group (vehicle control group: 100±7.33%; no-Cre control group: 71.22±12.27%; Dicer KO group: 46.94±9.07% (Fig. 4C)). After nerve injury, the waveforms of the evoked action potentials recorded from distal sciatic nerve had dramatically changed. Instead of single identifiable CAPs, several waveform signals with lower amplitude were recorded (Fig. 3A1, A2). A quantification of these data, after rectification and integration of the appropriate time windows, revealed that during the period of recovery, both at 14 days (Fig. 3C2) and 21 days (Fig. 4D), the response was considerably smaller in the Dicer KO group. At 14 days after nerve crush (Fig. 3C2), the CAP in vehicle treated groups was 100±20.24%; in no-Cre animals was 124.5±26.73%, while the action potential in Dicer knock out animals was 49.96±15.21%. At 21 days (Fig. 4D), similar to day 14 data, Dicer KO (32.13±8.14%) displayed delayed recovery comparing to vehicle treated (100±21.89%) or no-Cre group (100.8±18.76%) at 21 days. The wave shapes recorded from control groups 21 days after nerve crush also showed greater restoration compared with the group of Dicer KO. 21 days after nerve injury, the initial response amplitude remained reduced and was followed by several small waves (Fig 4A upper graph). In the Dicer KO group, the response remained delayed and only small waveform signals were recorded from the distal end of the nerve, which exhibited wave shapes similar to 14 day’s data (Fig. 4A lower graph).

Figure 3. Electrophysiological evaluations of sciatic nerve functional recovery at 14 days after sciatic nerve crush.

A, Typical examples of responses recorded from the distal side of the sciatic nerve after electrical stimulation. Stimulation of the proximal side of the sciatic nerves (500 µA, 100 µsec) induced a fast response with a single CAP in the intact nerve and a delayed and spread-out response in the regenerating nerve. A1, Compound action potentials (CAPs) recorded from the controlateral uninjured sciatic nerve. The signals recorded from vehicle treated mice and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice (no Dicer deletion) were similar to that recorded from tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice (Dicer KO). The duration from the stimulation artifact to onset of compound action potential was used for the calculation of nerve conduction velocity. No difference of NCV (B1) or rectified and integrated compound action potential amplitude (C1) was observed between the different groups in the controlateral uninjured nerves. A2, Delayed responses were recorded from the injured sciatic nerves 14 days after crush. Note the additional delay in the response of Dicer KO sciatic nerve of nearly 6 ms, indicating a reduced nerve conduction velocity, and suggesting a slower rate of functional recovery after injury in the Dicer KO animals. B2, Animals from all 3 groups gradually restored NCV on the crushed nerve with time. However, animals with Dicer KO (tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl) have a significantly lower NCV compared with control animals (tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice and vehicle treated mice). C2, Dicer KO animals also exhibited smaller rectified and integrated response amplitude (N=5, * p<0.05).

Figure 4. Electrophysiological evaluations of sciatic nerve functional recovery at 21 days after sciatic nerve crush.

A, Typical examples of delayed responses were recorded from the injured sciatic nerve 21 days after nerve crush with electrical stimulations at the proximal ends. Note the appearance of a quick response in signals from the control animals, while Dicer KO sciatic nerve still showed only a delayed response without any fast component. Waveform signals recorded at 14 days after nerve injury are repeated from Figure 3 A2 for comparison purposes. B, The NCV were compared between control groups (vehicle treated mice and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl ) and Dicer KO groups (tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl ). Animals with Dicer KO had a significantly lower NCV. C, Difference in NCV between 14 and 21 days in three groups of mice. Although animals from all groups showed restored NCV with time, the increase in NCV was significantly smaller in Dicer KO animals from day 14 to day 21. D, Dicer KO animals exhibited smaller rectified and integrated response amplitude 21 days after injury (N=5, * p<0.05).

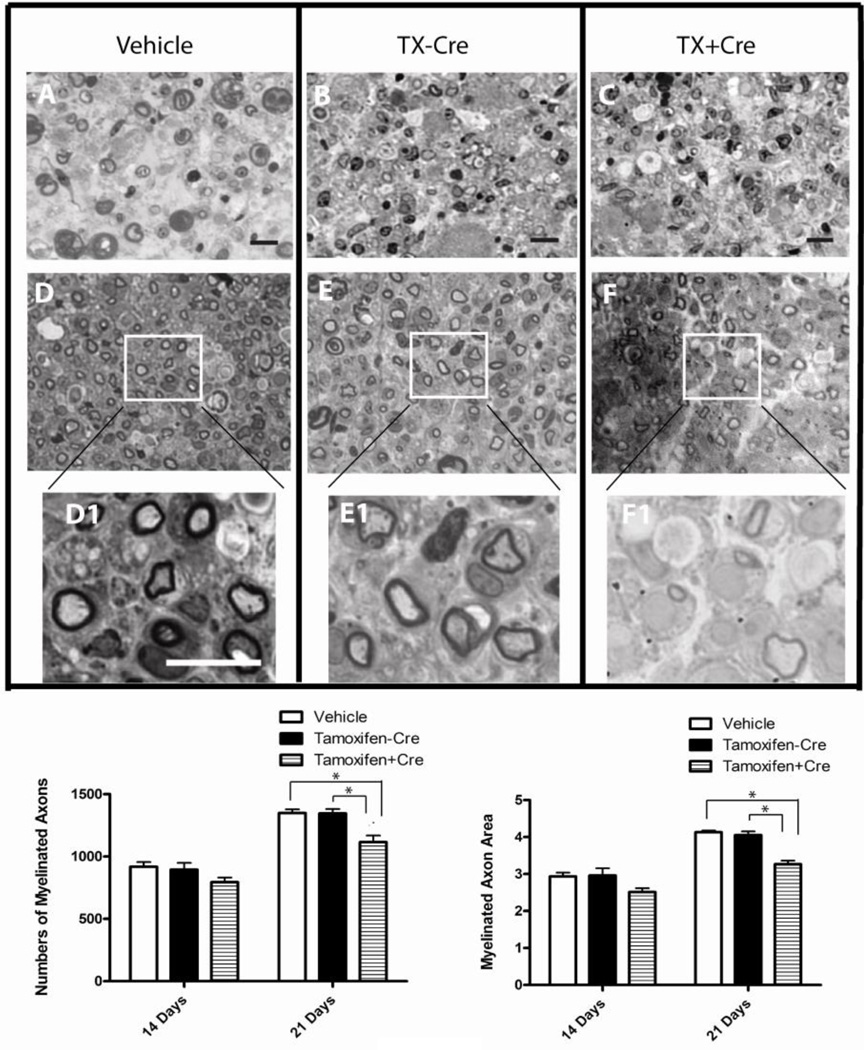

The effect of Dicer KO on anatomical recovery of crushed sciatic nerve

Semi-thin cross sections of sciatic nerves were stained with osmium tetroxide and Richard’s dye to help visualize myelinated nerve fibers. Myelinated nerve fiber mean areas as well as the number of myelinated nerve fibers were quantified with NIH ImageJ software. At day 14 after nerve crush, the sizes and number of the individual myelinated nerve fibers of regenerating nerves in Dicer KO group were smaller than those observed in control nerves (Fig. 5A–C). The compromised regeneration in Dicer mutants became apparent at 21 days (Fig. 5D–F) when the difference in size and numbers of axon fibers between the control and the knockout groups reached statistical significance (Fig. 5G and H) (number of regenerated nerve fibers: vehicle control group: 1349.50±28.04; no-Cre control group: 1345.50±36.37; Dicer KO group: 1115.50±52.73; myelinated axon area: vehicle control group: 4.13±0.05; no-Cre control group: 4.05±0.09; Dicer KO group: 3.26±0.09. N=6, P<0.05). Thus, the histological data confirmed that Dicer deletion impairs anatomical recovery of peripheral nerve following crush injury.

Figure 5. Light microphotographs of semi-thin sections of sciatic nerve give evidence of delayed regeneration of sciatic nerve fibers after Dicer deletion.

Transverse semi-thin sections of sciatic nerve distal to the injury sites were examined under light microscopy. Light micrographs of nerves from vehicle treated group (A, D) and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl group (B, E) were compared with that of tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt: Dicerfl/fl (Dicer knockout) group (C, F) at 14 days (upper panel) and 21 days (lower panel) post injury. Images obtained at higher magnification (D1, E1, F1) clearly showed the regenerating axons with new myelin wrappings. Note smaller axons with thinner myelin in Dicer knockout group (F1) compared to the two control groups (D1, E1), The statistical analysis showed that the number of myelinated axons (G) and myelinated mean axon area (H) at day 21 after crush were significantly lower in Dicer knockout mice. (Scale bar=10 µm, N=6, * p<0.05).

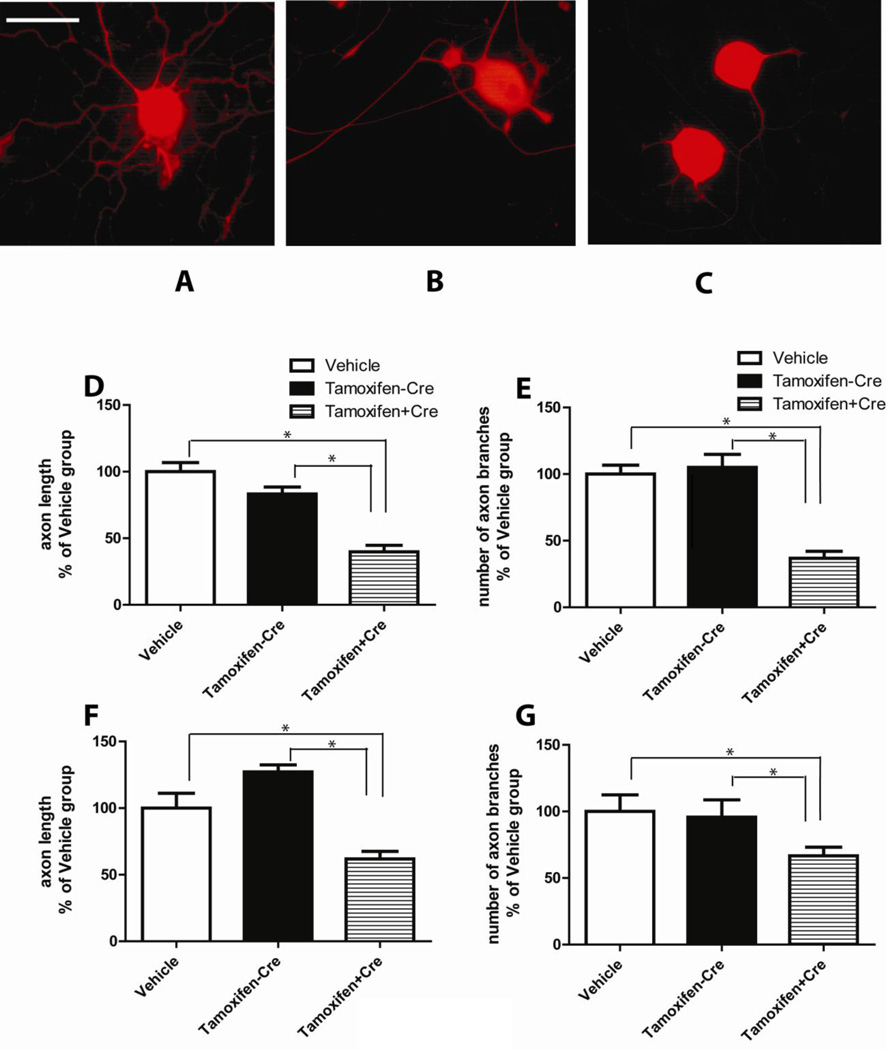

Direct effect of Dicer deletion on regenerating DRG neurons in vitro

To assess the direct effects of Dicer deletion on regenerative axon growth, in vitro studies were performed in dissociated DRG neuronal cultures. DRGs from tamoxifen or vehicle treatment CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl mice and tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice were collected at day 5 after conditioning sciatic nerve lesion. After such injury the regenerative capacity of the neurons are improved and can be detected as an increased axonal outgrowth in comparison to uninjured contralateral neurons. The neuronal cells were dissociated and plated sparsely on coverslips coated with poly-d-lysine and laminin. Immunostaining with the neuronal marker TUJ was used to visualize the neuronal cell bodies and axons in the cultures. The measurement of axon length and the counting of branches demonstrated that, in the absence of Dicer, the regenerative axon growth was significantly impaired compared to control groups (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Arrested regenerative axon growth after Dicer deletion in vivo and in vitro.

A, DRG culture from vehicle treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/f mice. B, DRG culture from tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice. C, DRG culture from tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl (knockout) mice. Fixed cells were incubated with antibodies against neuronal marker β-tubulin and signals were visualized with TX-Red conjugated secondary antibody. The statistical analyses were performed on the length (D) and the branch number (E) of the axons in dissociated DRG cultures. F, effect of 4-hydroxytamoxifen treatment in vitro, on axon length. G, effect of 4-hydroxytamoxifen treatment in vitro on axon branching. Dicer KO neurons had significantly less axon branches and shorter axons compared with control groups. (Scale bar=100 µm, N=30, * p<0.05).

Mean axon length of Dicer KO DRG neuron was approximately 200 µm after 24 hr culturing. In the two control groups, dissociated DRG neurons had more robust regenerative growth. The mean axon length was around 350 µm after 24hr culturing. For statistic analysis, we normalized all of the data to the vehicle treated group. DRG neurons from the tamoxifen treated Dicerfl/fl mice had approximately the same axon length in comparison with vehicle treatment CAG-CreERt: Dicerfl/fl group (vehicle control group: 100±6.75%, no-Cre control group: 83.20±5.28% (Fig. 6D)). The axon length in the tamoxifen treated CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl group decreased to 39.83±4.82% of the control level, due to Dicer KO. Dicer deletion also significantly inhibited axon branching. After 24hr culturing, the number of branches in Dicer KO DRG neurons was 63% lower than that of the two control groups (Vehicle control group: 100±6.6%; no-Cre control group: 105.10±9.75%; Dicer KO group: 36.81±5.26%. N=30, P<0.05 .(Fig. 6E)). Therefore, in vitro studies provided further evidence that the intact Dicer-dependent miRNA pathway is critical for regenerative axon growth in isolated neurons.

In additional experiment we asked the question whether deletion of Dicer in vitro might produce effect similar to the result obtained after the Dicer KO in vivo. Specifically, conditioned DRG neurons isolated from CAG-CreERt:Dicerfl/fl and Dicerfl/fl animals were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). The results of the experiment (Fig. 6F and 6G), demonstrated that ablation of Dicer in cultured DRG neurons produced similarly impaired regenerative axon growth as in Dicer whole animal KO. The axon length in Dicer KO group decreased to 61.79±5.79% in comparison with vehicle-treated group and no-Cre group (vehicle control group 100±11.17%; no-Cre control group 121.1±5.28% (Fig. 6F)). Likewise, Dicer KO in vitro also significantly inhibited axon branching. The number of branches in Dicer knockout group was 66.75% of the control group (Vehicle control group: 100±12.35%; no-Cre control group: 95.68±8.35%; Dicer KO group: 66.73±6.46%. N=30, P<0.05. (Fig. 6G)). Taken together, our results revealed that loss of Dicer in a whole animal as well as in isolated neurons produced similar deficits in axon regeneration. Therefore, in vitro studies provided further evidence that the intact Dicer-dependent miRNA pathway is critical for regenerative axonogenesis in isolated neurons.

DISCUSSION

Dicer ablation resulted in delayed functional recovery

Our experiments demonstrated a delayed functional recovery of Dicer KO in comparison to control groups in walking corridor and von Frey behavioral tests. Walking corridor SFI data are complementary to a recent study that showed progressive locomotor dysfunction and muscular atrophy after specific ablation of Dicer in post-mitotic postnatal motor neurons (Haramati, et al., 2010). The authors also reported the perturbed expression of neurofilament subunits in their Dicer KO model and linked this observation to deregulation of miR-9 (Haramati, et al., 2010). In another observation, loss of miR-206 accelerated progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and diminished survival (Williams, et al., 2009). It was also suggested that the beneficial actions of miR-206 were mediated by muscle-derived factors that promote nerve-muscle interactions in response to injury of motor neurons (Williams, et al., 2009). Therefore, our SFI data together with current observations suggest a significant role of miRNAs in motor neuron health and response to injury.

We have also observed delayed recovery of sensory function in Dicer KO using von Frey analysis. This observation is supported by previous findings which revealed that Dicer deletion led to severe defects in axon pathfinding of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) at the optic chiasm (Pinter and Hindges, 2010). This work has shown that miRNAs are essential regulatory elements for correct axon guidance decisions and the establishment of circuitry during neural development. Another recent report demonstrated that deletion of Dicer in Nav1.8+ sensory neurons attenuated or abolished inflammatory pain with corresponding decrease of nociceptor-specific pre-mRNA transcripts (Zhao, et al., 2010). Furthermore, spinal nerve ligation changed expression of the sensory organ-specific cluster of miRNAs in injured rat DRGs, which was linked to mechanical hypersensitivity (Aldrich, et al., 2009). Thus, recent observations indicated a possible role for miRNAs in mechanism of pain. It has been recently proposed that miRNAs may participate in the regulatory mechanisms of genes associated with the pathophysiology of chronic pain as well as the nociceptive processing following acute noxious stimulation (Kusuda, et al., 2011). Collectively, our von Frey data and previous reports propose a critical role of miRNAs in sensory neuron physiology and response to injury.

Dicer deletion impaired electrophysiological recovery

CAP amplitude and NCV are routinely used as two indexes to evaluate progression of nerve regeneration (Shen, et al., 2008, Sun, et al., 2009). CAP and NCV may be affected by both damage to peripheral nerve and by muscle atrophy caused by denervation of target tissue (Navarro, et al., 2007). To avoid muscle influence, this study was performed on isolated sciatic nerve preparation. Our electrophysiological data provided further evidence of the impaired nerve regeneration in the absence of Dicer. Measured NCV and CAP were significantly lower in Dicer KO animals at 14 and 21 day of regeneration. The delayed recovery of electrophysiological indexes may be explained by a failure in axon outgrowth and/or remyelination of the new fibers. After peripheral nerve injury, Schwann cells provide trophic and mechanical support for regenerating axons and subsequently form new myelin sheath (Navarro, et al., 2007). Interestingly, Schwann cell-specific deletion of Dicer fully arrest Schwann cell differentiation, resulting in early postnatal lethality (Bremer, et al., 2010). Specifically, most Schwann cells arrest at the promyelinating stage (Pereira, et al., 2010). In vivo, this results in a neurological phenotype similar to congenital hypomyelination (Yun, et al., 2010). Conversely, several miRNAs were identified as regulators of myelination (Bremer, et al., 2010, Yun, et al., 2010). For instance, miR-138 was described as a potential repressor of key immature Schwann cell genes, thus facilitating myelination (Yun, et al., 2010). Another miRNA, miR-219, was demonstrated to play a critical role in enabling the rapid transition from proliferating oligodendrocyte precursor cells to myelinating oligodendrocytes (Dugas, et al., 2010). Therefore, current data suggest that during nerve regeneration, disrupted miRNA biogenesis could result in failed remyelination and consequently in loss of saltatory propagation. Ablation of Dicer might also hamper the ionic remodeling process. Indeed, recent observation has identified a group of miRNAs regulating voltage-gated sodium channel Scn11a, alpha 2/delta1 subunit of voltage-dependent Ca-channel, and purinergic receptor P2r× ligand-gated ion channel 4 in the spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain (von Schack, et al., 2011). Thus, the impaired function in ion channels might be another factor potentially contributing to the delayed recovery of peripheral nerve electrophysiological characteristics.

Delayed anatomical recovery in Dicer mutants

Our histological evaluation showed that Dicer KO reduced total number of myelinated axons as well as diminished mean axonal area in regenerating sciatic nerve. Previous studies demonstrated the critical role for miRNAs in the transition of Schwann cells from the pro-myelin stage to the myelinating stage (Bremer, et al., 2010, Pereira, et al., 2010, Yun, et al., 2010). Ultrastructural and biochemical analysis of sciatic nerves from postnatal mice revealed a severe myelination defect in Schwann cell-specific Dicer KO animals (Bremer, et al., 2010, Pereira, et al., 2010, Yun, et al., 2010). Dicer-deficient Schwann cells not only failed to myelinate, but were also unable to form normal Remak bundles of unmyelinated small-caliber axons (Bremer, et al., 2010). Western blot analyses of Schwann cell-DRG co-cultures grown under myelinating conditions revealed that reduced levels of Dicer led to a decrease in the expressions of myelin basic protein and protein zero, which were accompanied by significant reductions in synthesis of myelin (Verrier, et al., 2010). Loss of Dicer specifically in Schwann cells can also result in signs of axonal degeneration, which suggest the involvement of miRNAs in the maintenance of axon integrity (Pereira, et al., 2010). Taken together, our data and previous findings suggest that ablation of Dicer might lead to myelination defect, perturbation of axon integrity and consequently to the failure of axon to grow back.

Dicer ablation impaired regenerative ability of PNS neuron in vitro

To answer the question whether the loss of Dicer could directly impact regenerative ability of PNS neuron, we performed a study in dissociated DRG cultures after conditioning sciatic nerve lesion. Interestingly, while conditioning lesion resulted in robust axon outgrowth in wild type neurons, Dicer-deficient neurons exhibited striking decrease in axon length and branching-arborization. The observed regenerative failure in DRG neurons after ablation of Dicer provided new evidence that miRNA pathway per se may play a critical role in intrinsic mechanism of axon growth. Several previous studies implicated miRNAs in translational control in dendrite outgrowth, as well as synaptic plasticity (Ashraf, et al., 2006, Siegel, et al., 2009). For example, miR-134, which is localized at synaptic sites, inhibits translation of lim-domain-containing protein kinase1 (Limk1 ) mRNA. Limk1 regulates actin filament dynamics and its ablation resulted in abnormalities in dendritic spine structure (Schratt, et al., 2006). In addition, miR-134 constrains neuritogenesis by down-regulating the expression of its target Pumillio, an evolutionarily conserved dendritogenesis promoting factor (Fiore, et al., 2009). MiR-138 controls the expression of acyl protein thioesterase 1 (APT1), an enzyme regulating the palmitoylation status of proteins that are known to function at the synapse (Siegel, et al., 2009). Recent studies have also shown that in cultured cortical and hippocampal neurons, miR-132 functions downstream from CREB to mediate dendritic growth and spine formation. Deletion of the miR-212/132 locus caused a dramatic decrease in dendrite length, arborization, and spine density (Magill, et al., 2010). Thus, while previous reports demonstrated an important role of miRNAs in neurito- and dendritogenesis our current observation revealed a critical role of Dicer-dependent miRNA pathway in axonogenesis.

Potential role of Dicer-dependent miRNAs in nerve regeneration

Our data clearly showed that albeit Dicer KO animals did recover after sciatic nerve crush, the recovery was significantly slower than in wild type controls. The remaining regenerative ability of peripheral nerves in Dicer mutants could be explained by remaining miRNAs, which were still detectable in the tamoxifen-treated samples. According to the literature, the tamoxifen-inducible Dicer KO usually results in around 80% elimination of Dicer mRNA (Albinsson, et al., 2011, Pereira, et al., 2010). Since in our study activation of Cre did not completely eliminated Dicer expression in sciatic nerves either, it is conceivable that the remaining gene was still functional. In addition, the mature miRNAs appear to be rather stable (O'Rourke, et al., 2007) and could continue to function for quite some time before being completely degraded (Kawase-Koga, et al., 2009). Therefore some stable miRNAs could also contribute to the process of nerve regeneration even after Dicer deletion. Conversely, some miRNA species can still be processed by alternative Dicer-independent biogenesis pathway recently uncovered in vertebrates (Yang and Lai, 2010). In this pathway, the pre-miRNA is loaded into Ago2 and then cleaved by the Ago2 catalytic center to the mature form (Cheloufi, et al., 2010). Thus, Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway might be another potential source of miRNAs production, and therefore provide some functional compensation after the ablation of Dicer .

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have provided the first evidence that the intact Dicer-mediated miRNAs pathway is required for effective and timely regeneration of peripheral nerve in vivo and regenerative axon growth in vitro. Axon loss has been largely neglected as a therapeutic target in a variety of neurological symptoms and disorders including multiple sclerosis, stroke, traumatic brain and spinal cord injury, peripheral neuropathies and chronic neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s (Coleman and Perry, 2002). Understanding how axon-degeneration/regeneration process is initiated by these diverse insults could lead to new treatments. We anticipate that our study could pave the way for further explorations of miRNA-regulated regenerative mechanisms in the peripheral as well as central nervous systems and possibly herald novel miRNA based therapies of neurological disorders and injuries.

Highlights.

We examined if Dicer ablation would negatively impact regenerative axon growth in vivo and in vitro

Dicer KO impaired regeneration in functional, electrophysiological, histological analyses

Dicer KO neurons failed to regenerate axons in dissociated dorsal root ganglia cultures

We show that Dicer-miRNA pathway is necessary for axonogenesis and for the functional recovery.

AKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Matthias Merkenschlager for permission to use Dicer floxed mice, and Dr. Andy McMahon for CAG-Cre ERt transgenic mice. We also would like to express sincere gratitude to Dr. Tatsuya Kobayashi for providing breeding pairs and continuous consulting on establishing the colony and troubleshooting experiments. We are thankful to Dr. Randall Renegar and Joani Zary for help with the histology. This research was supported in part by Brody Brothers Endowment Grant MT7779 (AKM), Wooten Laboratory grant (AKM), East Carolina University Research Development Award (AKM) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Award #A11-0093-001 (AKM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCE

- 1.Albinsson S, Skoura A, Yu J, DiLorenzo A, Fernandez-Hernando C, Offermanns S, Miano JM, Sessa WC. Smooth muscle miRNAs are critical for postnatal regulation of blood pressure and vascular function. PloS one. 2011;6:e18869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldrich BT, Frakes EP, Kasuya J, Hammond DL, Kitamoto T. Changes in expression of sensory organ-specific microRNAs in rat dorsal root ganglia in association with mechanical hypersensitivity induced by spinal nerve ligation. Neuroscience. 2009;164:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf SI, McLoon AL, Sclarsic SM, Kunes S. Synaptic protein synthesis associated with memory is regulated by the RISC pathway in Drosophila. Cell. 2006;124:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bremer J, O'Connor T, Tiberi C, Rehrauer H, Weis J, Aguzzi A. Ablation of Dicer from murine Schwann cells increases their proliferation while blocking myelination. PloS one. 2010;5:e12450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bremer J, O'Connor T, Tiberi C, Rehrauer H, Weis J, Aguzzi A. Ablation of Dicer from Murine Schwann Cells Increases Their Proliferation while Blocking Myelination. Plos One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, Hannon GJ. A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 2010;465:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nature09092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman MP, Perry VH. Axon pathology in neurological disease: a neglected therapeutic target. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuellar TL, Davis TH, Nelson PT, Loeb GB, Harfe BD, Ullian E, McManus MT. Dicer loss in striatal neurons produces behavioral and neuroanatomical phenotypes in the absence of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5614–5619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801689105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis TH, Cuellar TL, Koch SM, Barker AJ, Harfe BD, McManus MT, Ullian EM. Conditional loss of Dicer disrupts cellular and tissue morphogenesis in the cortex and hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4322–4330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4815-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugas JC, Cuellar TL, Scholze A, Ason B, Ibrahim A, Emery B, Zamanian JL, Foo LC, McManus MT, Barres BA. Dicer1 and miR-219 Are required for normal oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Neuron. 2010;65:597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiore R, Khudayberdiev S, Christensen M, Siegel G, Flavell SW, Kim TK, Greenberg ME, Schratt G. Mef2-mediated transcription of the miR379-410 cluster regulates activity-dependent dendritogenesis by fine-tuning Pumilio2 protein levels. EMBO J. 2009;28:697–710. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haramati S, Chapnik E, Sztainberg Y, Eilam R, Zwang R, Gershoni N, McGlinn E, Heiser PW, Wills AM, Wirguin I, Rubin LL, Misawa H, Tabin CJ, Brown R, Jr, Chen A, Hornstein E. miRNA malfunction causes spinal motor neuron disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13111–13116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006151107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hengst U, Cox LJ, Macosko EZ, Jaffrey SR. Functional and selective RNA interference in developing axons and growth cones. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5727–5732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5229-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawase-Koga Y, Otaegi G, Sun T. Different timings of Dicer deletion affect neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the developing mouse central nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2800–2812. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T, Lu J, Cobb BS, Rodda SJ, McMahon AP, Schipani E, Merkenschlager M, Kronenberg HM. Dicer-dependent pathways regulate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1949–1954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusuda R, Cadetti F, Ravanelli MI, Sousa TA, Zanon S, De Lucca FL, Lucas G. Differential expression of microRNAs in mouse pain models. Molecular pain. 2011;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, Kim VN. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu R-Y, Schmid R-S, Snider WD, Maness PF. NGF Enhances Sensory Axon Growth Induced by Laminin but Not by the L1 Cell Adhesion Molecule. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2002;20:2–12. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magill ST, Cambronne XA, Luikart BW, Lioy DT, Leighton BH, Westbrook GL, Mandel G, Goodman RH. microRNA-132 regulates dendritic growth and arborization of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20382–20387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015691107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMurray R, Islamov R, Murashov AK. Raloxifene analog LY117018 enhances the regeneration of sciatic nerve in ovariectomized female mice. Brain Res. 2003;980:140–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02984-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murashov AK, Chintalgattu V, Islamov RR, Lever TE, Pak ES, Sierpinski PL, Katwa LC, Van Scott MR. RNAi pathway is functional in peripheral nerve axons. Faseb J. 2007;21:656–670. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6155com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murashov AK, Pak ES, Hendricks WA, Owensby JP, Sierpinski PL, Tatko LM, Fletcher PL. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into dorsal interneurons. FASEB J. 2005;19:252–254. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2251fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natera-Naranjo O, Aschrafi A, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Identification and quantitative analyses of microRNAs located in the distal axons of sympathetic neurons. RNA. 2010;16:1516–1529. doi: 10.1261/rna.1833310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navarro X, Vivo M, Valero-Cabre A. Neural plasticity after peripheral nerve injury and regeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;82:163–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Rourke JR, Georges SA, Seay HR, Tapscott SJ, McManus MT, Goldhamer DJ, Swanson MS, Harfe BD. Essential role for Dicer during skeletal muscle development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada M, Nakagawa T, Minami M, Satoh M. Analgesic effects of intrathecal administration of P2Y nucleotide receptor agonists UTP and UDP in normal and neuropathic pain model rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:66–73. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paz N, Levanon EY, Amariglio N, Heimberger AB, Ram Z, Constantini S, Barbash ZS, Adamsky K, Safran M, Hirschberg A, Krupsky M, Ben-Dov I, Cazacu S, Mikkelsen T, Brodie C, Eisenberg E, Rechavi G. Altered adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in human cancer. Genome Res. 2007;17:1586–1595. doi: 10.1101/gr.6493107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereira JA, Baumann R, Norrmen C, Somandin C, Miehe M, Jacob C, Luhmann T, Hall-Bozic H, Mantei N, Meijer D, Suter U. Dicer in Schwann Cells Is Required for Myelination and Axonal Integrity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:6763–6775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0801-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira JA, Baumann R, Norrmen C, Somandin C, Miehe M, Jacob C, Luhmann T, Hall-Bozic H, Mantei N, Meijer D, Suter U. Dicer in Schwann cells is required for myelination and axonal integrity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:6763–6775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0801-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinter R, Hindges R. Perturbations of microRNA function in mouse dicer mutants produce retinal defects and lead to aberrant axon pathfinding at the optic chiasm. Plos One. 2010;5:e10021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schratt GM, Tuebing F, Nigh EA, Kane CG, Sabatini ME, Kiebler M, Greenberg ME. A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature. 2006;439:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nature04367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen H, Yuan Y, Ding F, Liu J, Gu X. The protective effects of Achyranthes bidentata polypeptides against NMDA-induced cell apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons through differential modulation of NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegel G, Obernosterer G, Fiore R, Oehmen M, Bicker S, Christensen M, Khudayberdiev S, Leuschner PF, Busch CJ, Kane C, Hubel K, Dekker F, Hedberg C, Rengarajan B, Drepper C, Waldmann H, Kauppinen S, Greenberg ME, Draguhn A, Rehmsmeier M, Martinez J, Schratt GM. A functional screen implicates microRNA-138-dependent regulation of the depalmitoylation enzyme APT1 in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:705–716. doi: 10.1038/ncb1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun WJ, Sun CK, Zhao H, Lin H, Han QQ, Wang JY, Ma H, Chen B, Xiao ZF, Dai JW. Improvement of Sciatic Nerve Regeneration Using Laminin-Binding Human NGF-beta. Plos One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verrier JD, Semple-Rowland S, Madorsky I, Papin JE, Notterpek L. Reduction of Dicer impairs Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2558–2568. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogelaar CF, Vrinten DH, Hoekman MF, Brakkee JH, Burbach JP, Hamers FP. Sciatic nerve regeneration in mice and rats: recovery of sensory innervation is followed by a slowly retreating neuropathic pain-like syndrome. Brain Res. 2004;1027:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Schack D, Agostino MJ, Murray BS, Li Y, Reddy PS, Chen J, Choe SE, Strassle BW, Li C, Bates B, Zhang L, Hu H, Kotnis S, Bingham B, Liu W, Whiteside GT, Samad TA, Kennedy JD, Ajit SK. Dynamic changes in the microRNA expression profile reveal multiple regulatory mechanisms in the spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain. PloS one. 2011;6:e17670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, Bassel-Duby R, Sanes JR, Olson EN. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science. 2009;326:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D, Raafat M, Pak E, Hammond S, Murashov AK. MicroRNA machinery responds to peripheral nerve lesion in an injury-regulated pattern. Neuroscience. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang JS, Lai EC. Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis in vertebrates. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4455–4460. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.13958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yun B, Anderegg A, Menichella D, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML, Awatramani R. MicroRNA-deficient Schwann cells display congenital hypomyelination. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:7722–7728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0876-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yun B, Anderegg A, Menichella D, Wrabetz L, Feltri ML, Awatramani R. MicroRNA-deficient Schwann cells display congenital hypomyelination. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7722–7728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0876-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zehir A, Hua LL, Maska EL, Morikawa Y, Cserjesi P. Dicer is required for survival of differentiating neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 2010;340:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao J, Lee MC, Momin A, Cendan CM, Shepherd ST, Baker MD, Asante C, Bee L, Bethry A, Perkins JR, Nassar MA, Abrahamsen B, Dickenson A, Cobb BS, Merkenschlager M, Wood JN. Small RNAs control sodium channel expression, nociceptor excitability, and pain thresholds. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10860–10871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1980-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]