Abstract

Genetic and molecular studies suggest that activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) plays an important role in vascular development, remodeling, and pathologic angiogenesis. Here we investigated the role of ALK1 in angiogenesis in the context of common pro-angiogenic factors (PAFs; vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] A and basic fibroblast growth factor [bFGF]). We observed that PAFs stimulated ALK1-mediated signaling, including Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation, nuclear translocation and Id-1 expression, cell spreading, and tubulogenesis of endothelial cells (ECs). An antibody specifically targeting ALK1 (anti-ALK1) markedly inhibited these events. In mice, anti-ALK1 suppressed MatrigelTM angiogenesis stimulated by PAFs, and inhibited xenograft tumor growth by attenuating both blood and lymphatic vessel angiogenesis. In a human melanoma model with acquired resistance to a VEGF receptor kinase inhibitor, anti-ALK1 also delayed tumor growth and disturbed vascular normalization associated with VEGF receptor inhibition. In a human/mouse chimera tumor model, targeting human ALK1 decreased human vessel density, and improved antitumor efficacy when combined with bevacizumab (anti-VEGF). Anti-angiogenesis and antitumor efficacy were associated with disrupted colocalization of ECs with desmin+ perivascular cells, and reduction of blood flow primarily in large/mature vessels as assessed by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Thus, ALK1 may play a role in stabilizing angiogenic vessels and contribute to resistance to anti-VEGF therapies. Given our observation of its expression in the vasculature of many human tumor types and in circulating ECs from patients with advanced cancers, ALK1 blockade may represent an effective therapeutic opportunity complementary to the current anti-angiogenic modalities in the clinic.

Keywords: ALK1, angiogenesis, TGFβ, VEGF

Introduction

Activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) is a type I transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) receptor subclass with distinct expression, signalling, and functional properties from other family receptors (1, 2). ALK1 is preferentially expressed on proliferating vascular endothelial cells (ECs). Genetic studies of ALK1−/ − mice and zebrafish harboring a loss-of-function mutation demonstrated that ALK1 plays a key role in vasculogenesis, particularly in vessel maturation involving recruitment and differentiation of perivascular cells (PCs), and in the organization and patency of neo-angiogenic vessels (3–6). In humans, type 2 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT2), an autosomal dominant vascular dysplasia syndrome, is linked to the loss-of-function mutations of ALK1 (7, 8).

ALK1 is phosphorylated upon forming a membrane complex with TGFβ and its type II receptor, which then phosphorylates the receptor-regulated Smad proteins (Smad1/5/8). Phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (pSmads) dimerize with Smad4, and the complex translocates to the nucleus triggering transcriptional regulation of target genes that regulate EC function and angiogenesis (9–12).

Early studies showed that ALK1 signaling is context-dependent and can be either pro- or anti-angiogenic (11–16). Recent reports revealed that ALK1 signaling promoted angiogenesis through a synergistic action of TGFβ and bone morphogenesis protein 9(BMP9) (17); further, a soluble ALK1/extracellular domain (ECD) Fc-fusion protein (RAP-041) reduced xenograft tumor burden in mice through anti-angiogenesis (18). These studies suggest that ALK1 is pro-angiogenic.

During angiogenesis, many pro-angiogenic factors (PAFs), including vascular endothelial and basic fibroblast growth factors (VEGF, bFGF), are coordinately overexpressed by tumor, stromal, and infiltrating myeloid cells (19–25). An association between VEGF expression/activity and ALK1 dysregulation in HHT syndrome has been suggested (7, 8, 15, 26, 27), although the molecular and cellular mechanisms of this relationship remain unclear.

This study aimed to verify the pro-angiogenic role of ALK1 and elucidate its relationship with VEGF in tumor angiogenesis via pharmacologic approaches utilizing ALK1-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).

Materials and Methods

Cells and tissues

Human ECs were obtained from Clonetics and cultured in EGM®-2 containing serum and a cocktail of growth factors (Lonza). Human lung fibroblast cells (MRC-5) were from Sigma. Human melanoma M24met cells were described previously (28). Human breast cancer MBA-MD-231/Luc cells were from Xenogen Corp. Human peripheral blood samples were collected with informed consent and local institutional review board approval. ALK1 expression in circulating ECs (CECs) was assessed according to a modified protocol using Alexa Fluor®-labeled anti-human ALK1 (29). See Supplementary Materials for human tumor and normal tissue specimens.

Reagents and animals

Anti-human ALK1 mAb (Anti-huALK1 [PF-03446962]) was generated by immunizing human immunoglobulin G (IgG) 2-transgenic XenoMouse® (30). The antibody potently and selectively binds to human ALK1 with an affinity (Kd) of 7 ± 2 nM (Supplementary Fig. 1A). The murine anti-ALK1 mAb (Anti-muALK1) was generated from mouse hybridoma. Amu-VEGF (mAb against human [hu] and murine [mu] VEGF-A), sunitinib (inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases [RTKs] and several other RTKs), and PF-00337210 (selective inhibitor of VEGF RTKs) were generated at Pfizer. Bevacizumab (anti-huVEGF-A) was from Henry Shein. ALK1/ECD Fc-fusion protein and growth factors were from R&D Systems. Supplementary Table A describes these agents in detail. All mAbs were dosed subcutaneously once weekly (QW), and RTK inhibitors were dosed orally (PO) once daily (QD).

In vitro tubulogenesis assays

ECs and MRC-5 cells were seeded in PAF-reduced MatrigelTM (BD Biosciences) and treated with testing agents and stimuli diluted in endothelial basal medium (EBM)-2 containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The supernatant was changed every 3 days. At day 9, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with anti-huCD31 mAb (Santa Cruz) and Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Images were captured using Cellomics (Thermo Scientific) and quantified using Image-Pro® Plus (Media Cybernetics). See Supplementary Methods for other in vitro assays.

In vivo models

See Supplementary Materials for mice used in in vivo studies and general information on conventional xenograft models. For the chimera tumor model, 50 μL of 2×106 M24met cells mixed with Collgen IV and human fibronectin (both BD Biosciences) were intradermally injected into human neonatal foreskin engrafted in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice (31). Tumor volumes (TV) were calculated according to 0.5×[length×(width)2]. Antitumor efficacy was calculated according to [1-ΔTreat/ΔControl]×100, where ΔTreat and ΔControl were average tumor volume changes during the treatment period for the treated and control groups, respectively.

Immunofluorescence staining

Frozen chimera tumor sections (20 μm) were blocked with 5% rabbit serum/0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/0.3% Triton X-100/PBS. huALK1 was stained with a goat anti-ALK1 antibody (Santa Cruz); CD31 was stained with an Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled anti-huCD31 antibody (BioLegend) or a rat anti-muCD31 clone (MEC 13.3; BD Biosciences). Murine lymphatic vessels were stained with antibody against LYVE-1 (Abcam). The corresponding Alexa Fluor®-labeled secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. Slides were counter-stained with DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories) and images were captured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope and an AxioCam HR color digital camera. For quantification, 3–5 “hotspot” areas were captured for each slide by at least two individuals. Images were analyzed and quantified using Image-Pro® Plus. For perivascular marker staining, tumor sections were co-incubated with sheep anti-huCD31 (R&D Systems) and rabbit anti-desmin (Millipore) antibodies, followed by Alexa Fluor®-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Three-dimensional Z-stack images were captured with a Zeiss AxioPlan 2 microscope using AxioVision 4.8 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). Image reconstruction and surface rendering were performed using the 3D Constructor 5.1 plug-in for Image-Pro® Plus.

Ultrasound measurements

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CE-US) images were acquired using an Acuson Sequoia 512® system (Siemens Medical Solutions) with a 15L8 linear array transducer (32). Time required for each pixel of the tumor to return to 20% of the original amplitude (T20%) was assessed and values were binned in 1.5-sec increments.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise noted, the statistical significance in mean values was determined by one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) with a Dunnett’s multiple-comparison post test (GraphPad Prism®). A P-value <0.05 is considered significant.

Results

Smad1/5/8 signaling pathway can be inhibited by Anti-huALK1

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used to investigate ALK1 signaling and functional activity due to their relatively high-level surface ALK1 expression compared with other EC lines (Supplementary Fig. 1B, C). Western blotting and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays showed that Anti-huALK1 dose-dependently inhibited serum-stimulated pSmads and Id-1 expression in HUVECs, respectively (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1. Modulation of ALK1 signaling PAFs and Anti-huALK1 in HUVECs.

A, top: cells were starved overnight and treated with Anti-huALK1 for 2–4 hours followed by a 45-minute stimulation with 2.5% FBS. pSmads were detected by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as loading control (n = 2). Bottom: cells were treated as abov and the Id-1 transcript in the presence of 0.3× of EGM®-2 BulletKit® (Lonza; 30-minute stimulation) was measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Shown are fitted curves of dose-dependent inhibition of Id-1 by Anti-huALK1 from three experiments.

B, cells were starved for 2–4 hours and incubated with Anti-huALK1 (200 nM) for an additional 1–2 hours before a 45-minute stimulation with VEGF (10 ng/mL), bFGF (30 mg/mL), or TGFβ (1 ng/mL). pSmads and Id-1 were detected by Western blotting. GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was probed as loading control (n = 3).

C, cells were treated as in B, permeabilized, and stained for pSmads (green). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue) to indicate the presence of cells after Anti-huALK1 (n = 2).

D, cells and the experiment details were the same as in B, except that VEGF and TGFβ were used as stimuli, and sunitinib (50 nM) and ALK1/ECD (200 nM) were also used as inhibitors in the assay (n = 3).

To understand the role of ALK1 in tumor-associated angiogenesis, we examined whether PAFs could regulate ALK1 signaling. VEGF and bFGF rapidly induced pSmads and Id-1 in HUVECs as assessed by Western blotting, and these signals were blocked by Anti-huALK1 (Fig. 1B). Anti-huALK1 also attenuated VEGF and bFGF-stimulated pSmads translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 1C). Thus, in addition to TGFβ (a known ALK1 ligand), VEGF and bFGF may also activate Smads and Id-1 in an ALK1-dependent manner.

To address whether VEGF canonical signaling was involved in modulating ALK1 downstream components, we applied sunitinib in the signaling assay and observed that sunitinib significantly suppressed pSmads and Id-1 stimulated by VEGF or TGFβ These downstream molecules were also inhibited by an ALK1/ECD fusion protein in the same assay (Fig. 1D). These results imply a close interplay between the VEGF/VEGF receptor (VEGFR) and TGFβ/ALK1 pathways.

Anti-huALK1 inhibits PAF-mediated EC proliferation and tubule formation

We next investigated whether PAFs contribute to ALK1-mediated EC function. First, using an electronic cell sensor assay (RT-CESTM, Roche), where cellular phenotypical changes were measured in real time (see Supplementary Methods), we observed that Anti-huALK1 rapidly inhibited PAF-stimulated HUVEC attachment and spreading (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. 2A). Longer incubation (up to 15 hours) had a similar result (data not shown). Second, in a co-culture assay, we observed that Anti-huALK1 significantly inhibited VEGF-stimulated EC tubulogenesis (Fig. 2B, C); tubulogenesis under bFGF and TGFβ was moderately inhibited by Anti-huALK1. Anti-huALK1 also inhibited VEGF and bFGF-mediated tubulogenesis by human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (HPAECs) in the co-culture assay (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Thus, VEGF and bFGF can promote EC phenotypical function in an ALK1-dependent manner, consistent with their ability to stimulate ALK1 signaling.

Figure 2. HUVEC function can be inhibited by Anti-huALK1.

A, Anti-huALK1 inhibited PAF-induced EC attachment and spreading. HUVECs (in triplicates) in a 96-well plate equipped with electro-sensor probes (RT-CESTM) were incubated with PAFs ± Anti-huALK1 (200 nM) in basal media containing 1% FBS for 2 hours. Cellular phenotypical changes were recorded in real time and reported as an arbitrary unit (activation index). Data are average ± SD.

B, HUVECs were co-cultured with MRC-5 fibroblast cells. Shown are representative photoimages of the tubule network in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/mL), bFGF (30 ng/mL), or TGFβ (1 ng/mL) ± Anti-huALK1 (2, 20, and 200 nM). A representative photoimage of the tubule network in basal media absent of any exogenous growth factors is also shown (EBM-2 + 5% FBS).

C, tubule area was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods (8 fields/well; 2 wells for each concentration). Data under each PAF were normalized to that of PAF alone (control) and expressed as average ± SEM.

ALK1 promotes tumor growth via angiogenesis

In the AngioReactorTM model containing PAFs, a mAb against murine ALK1 (Anti-muALK1) significantly inhibited murine angiogenesis (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Fig. 3A). Anti-muALK1 produced significant tumor growth inhibition (TGI) of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer xenograft tumors, in which muALK1 was found to be expressed in the vasculature and colocalized with muCD31 (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Fig. 3B). The TGI was associated with substantial reduction of microvessel density (muCD31 staining) and moderate inhibition of murine lymphatic vessel density (LYVE-1 staining) (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with the observation that human lymphatic ECs express ALK1 (Supplementary Fig. 1C), and that ALK1 signaling is involved in multiple stages of lymphatic development in mice (6). Thus, ALK1 promoted murine blood and lymphatic angiogenesis and xenograft tumor growth.

Figure 3. Anti-muALK1 inhibited angiogenesis and tumor growth in mice.

A, PAF-enriched AngioReactorsTM were implanted in mice and murine angiogenesis was assessed 10 days later (n = 6–8/group). Anti-muALK1, Amu-VEGF, or A1D16 (a non-specific mouse IgG1 control) was administered either systemically (4 days post implant) or pre-mixed in the devices (30 μg/mL each). *, P < 0.001 versus either of the control groups. Results were reproducible in two other experiments.

B, Anti-muALK1 inhibited the growth of mammary fatpad-implanted MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors in mice (n = 2 studies). Top left: colocalization (yellow) of muALK1 (red) with muCD31 (green) in the tumor vasculature. Bottom left: Anti-muALK1 (QW and twice weekly [BIW]) and Amu-VEGF produced 59%, 68%, and 81% TGI compared with the control group, respectively (n = 10/group). Top right: photoimages of immunofluorescent staining of murine CD31+ blood vessels (green) and LYVE-1+ lymphatic vessels (red) from the xenograft tumors. Bottom right: quantification of the positive staining areas of the above two markers. †, P < 0.05 and ‡, P < 0.01 versus control.

C, inset: representative photoimages of immunofluorescent staining of huCD31+ and muCD31+ vessels in tumors of the control and Anti-huALK1 (10 mg/kg) groups. Single injection of Anti-huALK1 (1–50 mg/kg) dose-dependently inhibited huCD31 in chimera tumors. Bars: group mean ± SEM (6–10 animals/group, 3–5 hotspots/tumor section, two independent viewers). †, P < 0.05 and ‡, P < 0.01 compared with IgG2 isotype control.

D, Anti-huALK1 inhibited huCD31+ vessel area to a similar degree as that by sunitinib and bevacizumab in the chimera model (n = 3). JBS5 (anti-human integrin α5β1) was used as a reference mAb. Bars: group mean ± SEM (5–6 animals/group; 3–5 hotspots/tumor section; two independent viewers). †, P < 0.05 versus control.

To investigate whether huALK1 can promote human vessel function during tumor growth, we used a human/mouse chimera tumor model, in which local human angiogenesis was attained in the presence of human melanoma tumors grown in human foreskin engrafted in SCID mice (31). Immunofluorescent staining showed that tumor vessels were positive for huCD31 and huALK1 (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Systemic administration of Anti-huALK1 significantly and dose-dependently reduced huCD31+ microvessel density (huMVD) compared with a nonspecific control IgG2 (Fig. 3C). Anti-huALK1 generated a similar huMVD reduction (40–73%) compared with sunitinib (33–58%) and bevacizumab (40–46%) across several studies (Fig. 3D), suggesting that, similar to VEGF/VEGFRs, ALK1 may be a factor promoting robust human angiogenesis.

ALK1 may contribute to resistance to anti-VEGF treatments through dysregulation of vessel normalization

Given the observed involvement of VEGF in ALK1 signaling, we investigated whether tumors secreting a higher level of VEGF are more sensitive to anti-ALK1 treatment. We chose M24met/R xenograft tumors that had acquired resistance to a VEGF RTK inhibitor (PF-00337210), because these tumors express significantly higher huVEGF-A under PF-00337210 treatment, compared with untreated tumors (Fig. 4Ai). The vasculature of the M24met/R tumors was found to be ALK1+/CD31+/desmin+ (Fig. 4Aii–iv; desmin is a marker for PCs) and appeared smooth, reminiscent of the so-called “normalized vessels” (33–35). Anti-muALK1 plus PF-00337210 generated a statistically significant TGI (57%) compared with PF-00337210 alone (Fig. 4Av). In a separate study, Anti-muALK1 alone did not generate any antitumor efficacy (data not shown). Thus, VEGF RTK inhibitor treatment resulted in increased VEGF that may be required for ALK1-mediated angiogenesis. Enhanced efficacy of Anti-muALK1 combined with PF-00337210 was associated with further reduction of CD31+ vessels in the tumor than PF-00337210 alone (Supplementary Fig. 4A); furthermore, the remaining vessels in this group showed diminished CD31+/desmin+ co-staining and increased sprouting (Fig. 4 Avi, vii).

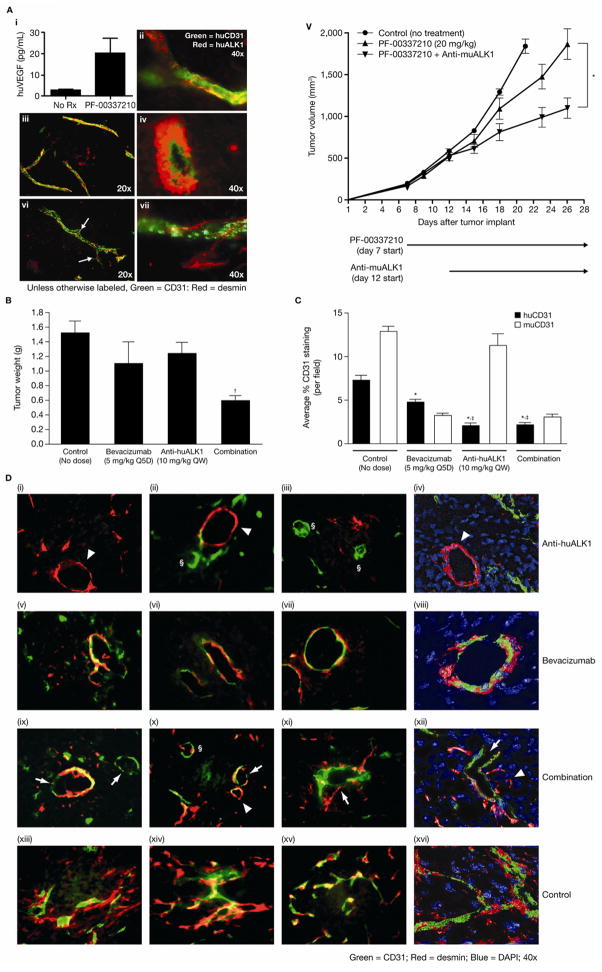

Figure 4. ALK1 inhibition disrupted interaction between ECs and PCs in the M24met/R model (A) and the chimera tumor model (B D).

A, (i) ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) showed increased human VEGF expression in PF-00337210-treated compared with untreated M24met/R tumors; vascular staining (immunofluorescent) was performed and showed co-localization of ALK1 and CD31 (ii) and muCD31 and desmin (iii, iv). (v) M24met/R tumors lacked response to PF-00337210 (▲) compared with untreated tumors (●); addition of Anti-muALK1 (10 mg/kg, QW) to PF-00337210 (▼) delayed tumor growth by 57% compared with PF-00337210 alone (*, P < 0.01; 10 animals/group). Vessels in the combination group showed increased sprouting (arrows) and tortuosity, and reduced CD31+/desmin+ co-staining (vi, vii). Rx, treatment.

B, chimera tumors were treated with Anti-huALK1, bevacizumab, or a combination of the two agents (treatment started when average TV was 50 mm3 and lasted for 10 days). Data are group average tumor weight ± SEM. †, P < 0.05 compared with control (5–7 animals/group).

C, quantification of huCD31 and muCD31 in tumors from B. Anti-huALK1 had no effect on muMVD due to lack of cross-reactivity with muALK1. Data are group average ± SEM (n = 5–7/group; 3–5 hotspots/tumor). *, P < 0.01 compared with control; ‡, P < 0.01 compared with bevacizumab.

D, representative images of huCD31 (green) and desmin (red) double staining of chimera tumors from B. Panels iv, viii, xii, and xvi are Z-stack three-dimensional images. Arrowheads: desmin+/huCD31− vessels; §, small vessels were mostly huCD31+/desmin− arrows: huCD31+ vessels devoid of desmin staining. Details are discussed in the Results section.

Next we investigated whether huALK1 inhibition can also enhance the TGI of bevacizumab using Anti-huALK1 in the chimera tumor model. Bevacizumab produced moderate (42%) TGI (Fig. 4B), despite its ability to significantly inhibit huMVD and muMVD (Fig. 4C). Serum samples from the chimera tumor mice contained significantly higher huVEGF-A compared with muVEGF-A (Supplementary Fig. 4B); thus, the lack of robust TGI by bevacizumab in this model could not be fully explained by its lack of cross-reactivity to muVEGF-A. An alternative explanation may be that tumors in this model have intrinsic resistance to bevacizumab. We questioned whether ALK1 played a role in this resistance. As expected, Anti-huALK1 alone showed little TGI (11%), due to its lack of cross-reactivity to muALK1 (and murine angiogenesis played a significant role in tumor growth). When Anti-huALK1 was combined with bevacizumab, significant TGI was observed (58% compared with control, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B), implying that huALK1 in human vessels was at least partially responsible for bevacizumab resistance in this model.

The above combination treatment did not further reduce huMVD (Fig. 4C), yet markedly improved efficacy. To understand why, we conducted in-depth immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of the vessels. Tumors treated with Anti-huALK1 were often left with large, open structures consisting of desmin+ PCs but lacked huCD31−, as if Anti-huALK1 “pulled” human ECs out of the vasculature that was once covered with PCs prior to Anti-huALK1 treatment (Fig. 4Di–iv, arrowheads). In the same tumor, the remaining smaller vessels were huCD31+/desmin−(indicated by §), suggesting that Anti-huALK1 prevented the recruitment of PCs to these vessels. The above observation/interpretation is consistent with the vascular characteristics of ALK1−/ − mice (3–5). Conversely, bevacizumab treatment resulted in large, open vessels positive for both huCD31 and desmin (Fig. 4Dv–viii), mimicking a stable/normalized vascular phenotype. Anti-huALK1 plus bevacizumab resulted in vascular structures that were largely either huCD31+ or desmin+ (Fig. 4Dix–xii). Overall, combination treatment reduced huMVD, vessel sprouting, and tortuosity compared with the control group (Fig. 4Dxiii–xvi). These data suggest that anti-ALK1 quantitatively disrupted the vascular normalization phenotype induced by bevacizumab, which may have contributed to the observed combinatorial antitumor efficacy.

ALK1 supports functional blood flow (BF) of large vessels

Because vascular normalization may result in better BF (36, 37), we investigated whether Anti-huALK1 could modulate BF in the chimera tumor model using CE-US that can differentiate flow rates within the microvasculature (32). Sixty hours after Anti-huALK1 administration, the development of vessels with fast flow rates was significantly inhibited compared with control tumors (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). Quantification of CE-US imaging parameters further revealed that the prevalence of fast BF (generally associated with large/arterial and functional vessels), but not slow BF (associated with small, leaky vessels), was suppressed in Anti-huALK1-treated tumors compared with control tumors (Fig. 5B, C). A similar conclusion could be drawn from a study using the same model and Power Doppler ultrasonography (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest that huALK1 may be involved in promoting efficient BF in functional and established vessels for human angiogenesis.

Figure 5. Effect of Anti-huALK1 on vascular BF and perfusion.

A, CE-US images of chimera tumors at baseline and 60 hours after treatment. The color bar represents time required for T20% (0–10 second). The formation of fast-flow vessels (T20%<1.5 seconds; yellow) is evident in the control, but not the Anti-huALK1-treated tumor (arrowheads). Fast flow in the kidney cortex is shown below the tumor (arrow).

B and C, quantitation of fast-flow (B) and slow-flow blood vessels (C; T20% in 3–10.5 seconds) in the control and Anti-huALK1 groups on days 1 and 4 of treatment. *, P = 0.011 (n = 4–5/group).

ALK1 expression in primary ECs and human tumor specimens

To begin assessing the relevance of ALK1 in human cancer, we investigated huALK1 expression by IHC in three tissue microarrays (TMAs) containing over 3,000 human tumor specimens representing more than 100 tumor types. The results showed that huALK1 was expressed primarily in the vasculature of most human tumors with varying frequency and intensity. The expression in tumor cells and normal tissues was generally weak or absent. The top 20 most frequently occurring tumor types were rank ordered based on ALK1 expression score (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Table B). Fig. 6B shows representative photomicrographs from three tumor types and the corresponding normal tissues. These data imply that ALK1 may be a potential therapeutic target in certain tumor types.

Figure 6. Expression of ALK1 on human tissue specimen and assessment of ALK1+/CECs in clinical samples.

A, rank order of percentage of patients with vascular ALK1 expression scores of 1+–3+ (by IHC with TMA samples) in the top 20 common cancer types. Numbers of tumor samples assessed are in brackets. *, Occasional presenceof ALK1 in prostate tumors.

B, representative photoimages of ALK1 vascular staining (brown) in the carcinoma tumors and normal tissues of colon (i, ii), lung (iii, iv), and pancreas (v, vi). Normal tissues are generally devoid of specific ALK1 staining compared with the corresponding tumors.

C, percent of viable ALK1+/CECs in evaluated cancer samples was significantly greater than those from healthy volunteers. Viable ALK1+/CEC counts were calculated from total ALK1+/CECs and percentage of total apoptotic cells (Supplementary Table C). †, P < 0.05 and ‡, P < 0.001 compared with healthy volunteers (Mann Whitney U test).

ALK1 expression in CECs from human peripheral blood (HPB) samples was also assessed. Greater levels of total ALK1+/CECs were detected in the HPB of patients with cancer than that of healthy volunteers (Supplementary Fig. 6; Supplementary Table C). The number of viable ALK1+/CECs was even more markedly increased in patients with advanced colon cancer, melanoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) compared with healthy volunteers (Fig. 6C). Implications of ALK1+/CECs are being investigated in an ongoing phase I study.

Discussion

Here we report that ALK1 signaling and function in ECs may depend on multiple PAFs including VEGF and bFGF, and that ALK1 may significantly contribute to blood and lymphatic angiogenesis, tumor growth, and resistance to therapies involving anti-VEGF or VEGF RTK inhibitors.

We showed that ALK1-mediated signaling, EC phenotypical changes, and differentiation were not only dependent on its natural ligand TGFβ, but also on VEGF and bFGF. TGFβ-stimulated Smads phosphorylation and Id-1 expression, until now thought to be specific to ALK1, were also inhibited by sunitinib, an inhibitor of VEGFRs and several other RTKs (38). Because VEGF and bFGF are not known to bind to ALK1, nor is TGFβ direct binding to VEGFRs expected, one possible explanation for our observations may be that there is intracellular cross-talk between the VEGF/VEGFR, bFGF/FGF receptor, and TGFβ/ALK1 pathways at the pSmads level. Consistent with in vitro observations, in vivo we observed that in mice bearing PF-00337210-treated M24met/R tumors, which produced higher serum VEGF than untreated M24met/R tumors, addition of Anti-muALK1 generated statistically significant antitumor efficacy (Fig. 4Av). TGFβ signaling has been shown to interact closely with several other pathways in a context-dependent fashion in models of development and pathologic diseases (reviewed by (39)). The molecular mechanism of the cross-talk between TGFβ/ALK1 and VEGF/bFGF pathways in angiogenesis is being investigated.

Through antitumor efficacy, functional imaging, and IHC studies, we reveal that the mode of action of ALK1 in angiogenesis may be different from, yet complementary to, that of VEGF/VEGFRs. VEGF/VEGFRs are well known to promote neovascularization with weak, leaky vessels deficient in tight junction and EC–PC interaction. Anti-VEGF therapy can result in vascular normalization (35, 36, 40). In supporting this, we reported that a VEGFR inhibitor selectively decreased total tumor perfusion, but not BF, in mature vessels (41). Although vascular normalization may temporarily improve the delivery of an anticancer agent, it has been associated with relapse and resistance to anti-VEGF therapies in the clinic (40). ALK1 may be essential in supporting the function of “normalized” vessels, as we show that anti-ALK1 disrupted ALK1+ EC–PC co-localization, reduced BF primarily in the large and fast-flow vessels, and improved efficacy in models otherwise resistant to anti-VEGF therapies. Collectively, our data support the hypothesis that ALK1 expression and function following anti-VEGF/VEGFR inhibitor therapy may contribute to vascular adaptation from the VEGF-driven neovascularization to the ALK1-driven productive angiogenesis involving mature vessels. The proposed mode of action of ALK1 may also explain the controversy regarding the role of ALK1 in angiogenesis (11–16). Taken together, our findings suggest a key differentiation between, and yet complementary role of, ALK1 and VEGF/VEGFRs in promoting tumor angiogenesis.

Translation to the clinic

Here we show that the ALK1 protein is broadly but heterogeneously expressed in human tumor vasculature, implying a need for patient selection in the clinic to achieve meaningful benefit from anti-ALK1 therapy. Regarding CECs, both the total and viable ALK1+/CEC counts were significantly increased in patients with cancer compared with healthy volunteers. ALK1 expression in tumors based on TMAs was not always consistent with the percentage of viable ALK1+/CECs; the latter may be a surrogate marker for the fraction of vessel turnover and may not directly correlate with ALK1 in the vasculature of solid tumors. The discrepancy may also reflect differences in disease stage and treatment history of patients associated with TMAs (mostly treatment-naïve, early-stage cancers) and CEC samples (all from advanced cancers). The significance of ALK1 positivity in CECs is being investigated. Because Id-1, an ALK1 target gene, has been implicated in the mobilization and function of endothelial progenitor cells (42), we hypothesized that ALK1 may play a key role in circulating EC mobilization and associated angiogenesis. Preliminary data from a phase I study showed that Anti-huALK1 (PF-03446962) reduced total ALK1+/CEC counts following the first treatment cycle in several patients (43)1. Additional studies are needed to correlate changes in ALK1+/CECs with clinical activity, in order to ascertain their potential utility as predictive biomarkers.

In conclusion, our data suggest that VEGF/bFGF can regulate ALK1 signaling and angiogenesis in vivo, and ALK1 plays an important and compensatory role in vascular angiogenesis. Targeting ALK1 may represent a novel and effective therapeutic opportunity, particularly for the treatment of patients resistant to anti-VEGF therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shile Liang, Paola Marighetti, Ines Martin Padura, Jasmin Otten, Joseph Zachwieja, Tina Lu, and Comparative Medicine, Pfizer for technical support; Steve Bender, Farbod Shojaei, Jamie Christensen, and Neil Gibson for support and discussion of the manuscript. We thank all of the participating patients and their families, as well as the global network of investigators, research nurses, study coordinators, and operations staff. Editorial assistance was provided by Jessica Stevens of ACUMED® (Tytherington, UK) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Grant support

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. K.W.F. received funding from NIH: R01CA103828 and R01CA134659. W.F. received funding from Eppendorfer Krebs-und Leukämiehilfe e.V.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Methods and data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

DDH, EC, LZ, PL, TAS, BS, JW, JHC, ZF, SB, GFC, WJL, CGS, and DRS are full-time

Pfizer Inc. employees and own Pfizer Inc. stock.

PM, KDW, RS, and AE declare no competing interests.

GW, KA, XJ, and JL disclose work performed as employees of Pfizer Inc.

KWF has received research funding from Pfizer Inc.

WF has received research funding, and fees for advisory board meetings and invited speeches from Pfizer Inc.

FB has received compensation from Pfizer Inc. for a consultant/advisory board role.

References

- 1.Massagué J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goumans MJ, Liu Z, ten-Dijke P. TGF-beta signaling in vascular biology and dysfunction. Cell Res. 2009;19:116–27. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urness LD, Sorensen LK, Li DY. Arteriovenous malformations in mice lacking activin receptor-like kinase-1. Nat Genet. 2000;26:328–31. doi: 10.1038/81634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh SP, Seki T, Goss KA, Imamura T, Yi Y, Donahoe PK, et al. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2626–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki T, Yun J, Oh SP. Arterial endothelium-specific activin receptor-like kinase 1 expression suggests its role in arterialization and vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2003;93:682–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000095246.40391.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niessen K, Zhang G, Ridgway JB, Chen H, Yan M. ALK1 signaling regulates early postnatal lymphatic vessel development. Blood. 2009;115:1654–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchuk DA, Srinivasan S, Squire TL, Zawistowski JS. Vascular morphogenesis: tales of two syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(Spec No 1):R97–112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadick H, Riedel F, Naim R, Goessler U, Hörmann K, Hafner M, et al. Patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia have increased plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 as well as high ALK1 tissue expression. Haematologica. 2005;90:818–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Rosendahl A, Sideras P, ten DP. Balancing the activation state of the endothelium via two distinct TGF-beta type I receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:1743–53. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Lebrin F, Larsson J, Mummery C, et al. Activin receptor-like kinase (ALK)1 is an antagonistic mediator of lateral TGFbeta/ALK5 signaling. Mol Cell. 2003;12:817–28. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamouille S, Mallet C, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 is implicated in the maturation phase of angiogenesis. Blood. 2002;100:4495–501. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.13.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallet C, Vittet D, Feige JJ, Bailly S. TGFbeta1 induces vasculogenesis and inhibits angiogenic sprouting in an embryonic stem cell differentiation model: respective contribution of ALK1 and ALK5. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2420–7. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.David L, Mallet C, Vailhe B, Lamouille S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Activin receptor-like kinase 1 inhibits human microvascular endothelial cell migration: potential roles for JNK and ERK. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:484–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao ES, Lin L, Yao Y, Boström KI. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor is coordinately regulated by the activin-like kinase receptors 1 and 5 in endothelial cells. Blood. 2009;114:2197–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scharpfenecker M, van Dinther M, Liu Z, van Bezooijen RL, Zhao Q, Pukac L, et al. BMP-9 signals via ALK1 and inhibits bFGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:964–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.002949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunha SI, Pardali E, Thorikay M, Anderberg C, Hawinkels L, Goumans MJ, et al. Genetic and pharmacological targeting of activin receptor-like kinase 1 impairs tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell D, Pobre EG, Mulivor AW, Grinberg AV, Castonguay R, Monnell TE, et al. ALK1-Fc inhibits multiple mediators of angiogenesis and suppresses tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:379–88. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–95. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepper MS, Mandriota SJ, Vassalli JD, Orci L, Montesano R. Angiogenesis-regulating cytokines: activities and interactions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;213 ( Pt 2):31–67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-61109-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, Bergsland E, Hanahan D. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1287–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernando NT, Koch M, Rothrock C, Gollogly LK, D’Amore PA, Ryeom S, et al. Tumor escape from endogenous, extracellular matrix-associated angiogenesis inhibitors by up-regulation of multiple proangiogenic factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1529–39. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–31. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose P, Holter JL, Selby GB. Bevacizumab in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2143–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0901421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flieger D, Hainke S, Fischbach W. Dramatic improvement in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia after treatment with the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonist bevacizumab. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:631–2. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller BM, Romerdahl CA, Trent JM, Reisfeld RA. Suppression of spontaneous melanoma metastasis in scid mice with an antibody to the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancuso P, Antoniotti P, Quarna J, Calleri A, Rabascio C, Tacchetti C, et al. Validation of a standardized method for enumerating circulating endothelial cells and progenitors: flow cytometry and molecular and ultrastructural analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:267–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellermann SA, Green LL. Antibody discovery: the use of transgenic mice to generate human monoclonal antibodies for therapeutics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:593–7. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi N, Haba A, Matsuno F, Seon BK. Antiangiogenic therapy of established tumors in human skin/severe combined immunodeficiency mouse chimeras by anti-endoglin (CD105) monoclonal antibodies, and synergy between anti-endoglin antibody and cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7846–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollard RE, Sadlowski AR, Bloch SH, Murray L, Wisner ER, Griffey S, et al. Contrast-assisted destruction-replenishment ultrasound for the assessment of tumor microvasculature in a rat model. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2002;1:459–70. doi: 10.1177/153303460200100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjamin LE, Hemo I, Keshet E. A plasticity window for blood vessel remodelling is defined by pericyte coverage of the preformed endothelial network and is regulated by PDGF-B and VEGF. Development. 1998;125:1591–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microenvironment abnormalities: causes, consequences, and strategies to normalize. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:937–49. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu J, Long Q, Xu S, Padhani AR. Study of tumor blood perfusion and its variation due to vascular normalization by anti-angiogenic therapy based on 3D angiogenic microvasculature. J Biomech. 2009;42:712–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duda DG, Batchelor TT, Willett CG, Jain RK. VEGF-targeted cancer therapy strategies: current progress, hurdles and future prospects. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, Louie SG, Christensen JG, Li G, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo X, Wang XF. Signaling cross-talk between TGF-beta/BMP and other pathways. Cell Res. 2009;19:71–88. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollard RE, Dayton PA, Watson KD, Hu X, Guracar IM, Ferrara KW. Motion corrected cadence CPS ultrasound for quantifying response to vasoactive drugs in a rat kidney model. Urology. 2009;74:675–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.01.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:8334–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mancuso P, Shalinsky DR, Calleri A, Quarma J, Antoniotti P, Jilani I, Hu-Lowe D, Jiang X, Gallo-Stampino C, Bertolini F. Evaluation of ALK-1 expression in circulating endothelial cells (CECs) as an exploratory biomarker for PF-03446962 undergoing phase I trial in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (Suppl):164s. abstract 3573. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.