Abstract

Objectives

To compare the timelines and recommendations of the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) and National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), in particular since the single technology assessment (STA) process was introduced in 2005.

Design

Comparative study of drug appraisals published by NICE and SMC.

Setting

NICE and SMC.

Participants

All drugs appraised by SMC and NICE, from establishment of each organisation until August 2010, were included. Data were gathered from published reports on the NICE website, SMC annual reports and European Medicines Agency website.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome was time from marketing authorisation until publication of first guidance. The final outcome for each drug was documented. Drug appraisals by NICE (before and after the introduction of the STA process) and SMC were compared.

Results

NICE and SMC appraised 140 drugs, 415 were appraised by SMC alone and 102 by NICE alone. NICE recommended, with or without restriction, 90% of drugs and SMC 80%. SMC published guidance more quickly than NICE (median 7.4 compared with 21.4 months). Overall, the STA process reduced the average time to publication compared with multiple technology assessments (median 16.1 compared with 22.8 months). However, for cancer medications, the STA process took longer than multiple technology assessment (25.2 compared with 20.0 months).

Conclusions

Proportions of drugs recommended for NHS use by SMC and NICE are similar. SMC publishes guidance more quickly than NICE. The STA process has improved the time to publication but not for cancer drugs. The lengthier time for NICE guidance is partly due to measures to provide transparency and the widespread consultation during the NICE process.

Article summary

Article focus

Has the STA process resulted in speedier guidance for NICE?

What are the differences in recommendation and timelines between SMC and NICE?

Key messages

The STA system has resulted in speedier guidance for some drugs but not for cancer drugs.

SMC publishes speedier guidance than NICE.

SMC and NICE recommend a similar proportion of drugs.

Strength and limitations of this study

Although some differences by SMC and NICE are shown, it is not possible in this study to say which is correct.

Accuracy of outcome data taken from NICE website and SMC annual reports is unclear.

Introduction

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) provides guidance on the use of new drugs in England and Wales. There has been controversy over its decisions, and the timeliness of drug appraisals, particularly those concerning new cancer drugs.1–4 NICE does not appraise all new drugs, but only those referred to it by the Department of Health (DH), after scoping and consultation.

In Scotland, the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) appraises all newly licensed medications (including new indications for medicines with an existing license). The simultaneous functioning of both organisations has been described as ‘complementary’,5 but debate arises when differences occur because of the implications for the NHS of a drug being provided in England but not in Scotland.

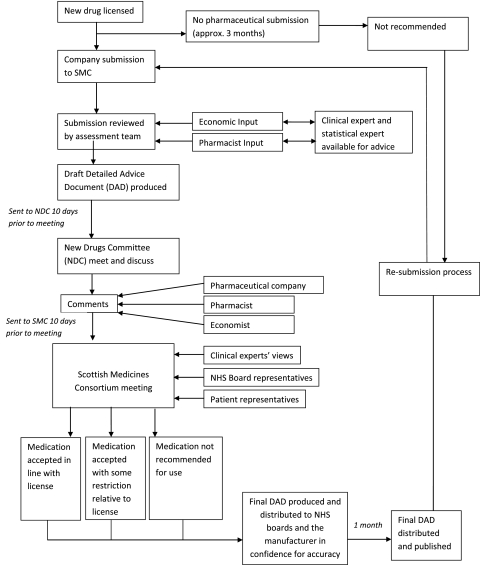

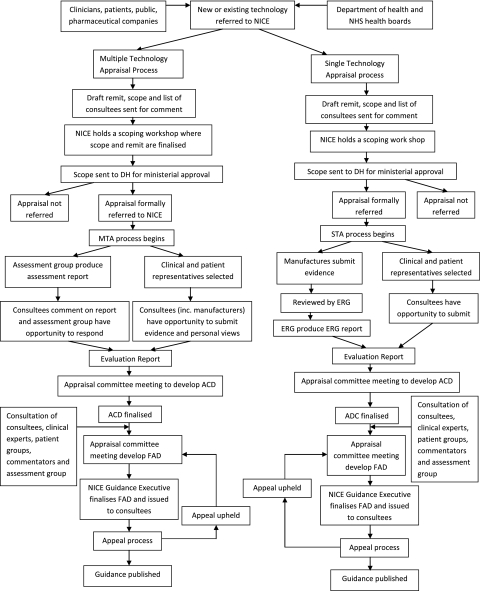

Flow charts outlining the processes are given in figures 1 and 2 (e-version only).

Figure 1.

Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) pathway.

Figure 2.

National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) pathway. ACD, Appraisal Committee Document; ERG, Evidence Review Group; FAD, Final Appraisal Determination.

Evolution of the NICE appraisal system

Before 2005, the main source of evidence for the NICE technology appraisal committees was a technology assessment report (TAR)—a systematic review of clinical and cost-effectiveness, usually with economic modelling, produced by an independent assessment group. NICE also received industry submissions including economic modelling by the manufacturer, and these were reviewed by the assessment group. The manufacturer was given an opportunity to comment on the TAR. The process was regarded as too time consuming and as leading to delays in availability of new medications for patients, especially controversial with new anticancer medications.6 Primary Care Trusts would often not fund new medications until guidance was produced.

In 2005, NICE introduced the ‘single technology assessment’ (STA) system wherein the main source of evidence for the appraisal is a submission, including economic evaluation and review of the clinical effectiveness, by the manufacturer, which is critiqued by one of the assessment groups. There is no independent systematic review or modelling. Currently, most new drugs are appraised under the new STA system, and the TAR-based system (also called multiple technology assessment (MTA)) is used for larger and more complex appraisals, such as for several drugs for the same condition, or, less often, one drug for several conditions.

The STA system is similar to that which has been used by SMC, where the main evidence is an industry submission, critiqued by SMC staff with a short summary of the critique being published with the guidance. During the STA process, an independent academic group critiques the industry submission, and the ‘evidence review group’ report is published in full (except for commercial or academic in confidence data) on the NICE website, making the STA process more transparent. In cases where SMC issue guidance on a medicine and it is then appraised by NICE using the MTA system, NHS Healthcare Improvement Scotland reviews the NICE MTA guidance and generally accepts it for use in Scotland, implicitly reflecting an assumption that the wider scope of an MTA and the extra work involved in the review allowed more evidence to be considered and analysis undertaken; the same arguments do not apply to NICE STA guidances and hence they are not used in Scotland.

There are two aims in this study. First, since it has been 6 years since the introduction of the STA process by NICE, it is timely to assess whether the change has been associated with speedier guidance. Second, we compare recommendations and timelines between NICE and SMC.

Methods

For all drugs appraised by both NICE and SMC, we calculated the time from marketing authorisation (obtained from the European Medicines Agency website) until publication of guidance. NICE data were taken from the technology appraisal guidance documents on their website. SMC data were extracted from annual reports and detailed appraisal documents. Drugs were defined as ‘recommended (NICE) or accepted (SMC)’, ‘restricted’ or ‘not recommended’, according to classification in the tables of appraisals published on the NICE website or SMC annual reports. The term ‘restricted’ can have various meanings, such as place in treatment pathway, patient group, or clinical setting. All medications appraised from the establishment of each organisation until August 2010 were included. When guidance differed, we examined possible reasons, noting if the difference was only about restrictions on use, rather than approval versus non-approval.

Results

NICE and SMC appraised 140 drugs, 415 drugs were appraised only by SMC and a further 102 only by NICE (which started 3 years before SMC). The higher number appraised by SMC reflects SMC's practice of appraising all newly licensed drugs, whereas only selected drugs are appraised by NICE.

Timeliness: NICE before and after the introduction of STAs

The main reason that NICE introduced the STA system was to allow patients, especially those suffering from cancer, quicker access to medications. The time from marketing authorisation to appraisal publication is presented in table 1. After 2005, the STA process reduced the time to publication of guidance. There is marked variability in NICE data throughout the years. For example, in 2009, the median time to publication for STAs was 8 months (range 4–38), but in 2010, the median time was 29 months (range 4–30). However, although the STA system has reduced the time from marketing authorisation to issue of guidance (median 16.1, range 4–41 months) months compared to 22.8 (range 2–77) months for MTAs, it has failed to reduce the time for anticancer medications. For STAs of cancer products, the appraisal process took an average of 25.2 (range 4–41) months compared with 20.0 (range 2–46) months for cancer-related MTAs.

Table 1.

SMC and NICE times to guidance by year

| SMC |

NICE |

|||||||||||

| Year | Number | Median (months) | Range (months) | Total | Median (months) | Range (months) | MTAs | Median (months) | Range (months) | STAs | Median (months) | Range (months) |

| 2000 | NA | 4 | 14 | 4–19 | 4 | 14 | 4–19 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2001 | NA | 4 | 13 | 3–17 | 4 | 13 | 3–17 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2002 | 23 | 5 | 1–23 | 11 | 18 | 9–29 | 11 | 18 | 9–29 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2003 | 57 | 7 | 1–30 | 10 | 34 | 7–46 | 10 | 34 | 7–46 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2004 | 59 | 8 | 1–32 | 13 | 22 | 2–35 | 13 | 22 | 2–35 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2005 | 71 | 8 | 1–29 | 2 | 11 | 3–19 | 2 | 11 | 3–19 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2006 | 94 | 6 | 1–44 | 21 | 21 | 6–77 | 19 | 21 | 6–77 | 2 | 19 | 17–20 |

| 2007 | 84 | 7 | 1–24 | 19 | 26 | 9–58 | 9 | 35 | 24–58 | 10 | 24.5 | 9–41 |

| 2008 | 72 | 7 | 1–30 | 21 | 26 | 2–60 | 11 | 36 | 2–60 | 10 | 12.5 | 5–37 |

| 2009 | 66 | 7 | 1–24 | 21 | 20 | 4–46 | 8 | 28.5 | 20–46 | 13 | 8 | 4–38 |

| 2010 | 30 | 10 | 1–30 | 4 | 29.5 | 4–35 | 1 | 35 | NA | 3 | 29 | 4–30 |

MTA, multiple technology assessments; NA, not applicable; NICE, National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium; STA, single technology assessment.

This increased length of appraisal is also reflected within SMC; anticancer drug appraisals take longer (median 8.0 months, range 1–29) months compared with 7.3 months (range 1–44) for all SMC drugs.

There was no significant difference between multi-drug and single-drug MTAs (median 22.8 months, range 2–77 and 21.5 months, range 3–58, respectively).

Timelines: NICE versus SMC

Comparing all appraised drugs, from marketing authorisation to publication, NICE guidance takes considerably longer, as shown in table 2, at median 21.4 months, compared to 7.4 months for SMC. For drugs appraised by both organisations, NICE guidance took a median 15.7 months longer than SMC guidance. In the SMC process, the Detailed Advice Document is distributed for 1 month to health boards for information and to manufacturers to check factual accuracy.

Table 2.

Median time from marketing authorisation to guidance publication

| All drugs | Cancer drugs | |

| Marketing authorisation to SMC, months (range) | 7.35 (1–44) | 8.00 (1–29) |

| Marketing authorisation to NICE, months (range) | 21.40 (2–77) | 23.62 (2–46) |

| Marketing authorisation to STA, months (range) | 16.05 (4–41) | 25.23 (4–41) |

| Marketing authorisation to MTA, months (range) | 22.81 (2–77) | 20.02 (2–46) |

MTA, multiple technology assessments; NICE, National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium; STA, single technology assessment.

Differences in recommendations between NICE and SMC

NICE and SMC appraised 140 drugs, 415 drugs were appraised only by SMC and a further 102 only by NICE (which started 3 years before SMC). The higher number appraised by SMC reflects SMC's practice of appraising all newly licensed drugs, whereas only selected drugs are appraised by NICE. Of the 140 comparable appraisals, the same outcome was reached in 100 (71.4%), the same outcome but with a difference in restriction in 27 (19.3%) and a different outcome in 13 (9.3%). Details of the differences, and possible reasons, are shown in table 3. It was found that 90.1% of all medications appraised by NICE were recommended, with or without restriction, 71.5% were defined as recommended and 18.6% as restricted, whereas 80% of medications were recommended by SMC, with or without restriction (39.3% defined as accepted and 41.1% defined as restricted), as shown in table 4. (Note that these tables reflect how NICE and SMC have categorised their decisions and they may not be comparable as discussed below.)

Table 3.

Differences between NICE and SMC appraisals

| NICE product | Condition | Decisions | Reason | PAS |

| Infliximab | Crohn's disease (active severe in adults) | Recommended by NICE, not by SMC |

|

No |

| Infliximab | Crohn's disease (fistulising) | Recommended by NICE, not by SMC |

|

No |

| Infliximab | Acute, severely active ulcerative colitis | Recommended by NICE, but not by SMC |

|

No |

| Infliximab | Severe ankylosing spondylitis (adults) | Restricted by SMC, not recommended by NICE |

|

No |

| Pimecrolimus | Atopic dermatitis (eczema) | Recommended by NICE, not by SMC |

|

No |

| Docetaxel (in combination with steroid) | Prostate cancer (hormone-refractory) | Recommended by NICE, not by SMC |

|

No |

| Cinacalcet | Hyperparathyroidism (refractory) | Use very restricted use by NICE, not recommended by SMC |

|

No |

| Telbivudine | Chronic hepatitis B | Recommended by SMC, not by NICE |

|

No |

| Pegaptanib | Wet age-related macular degeneration | Restricted by SMC, not recommended by NICE |

|

No |

| Sunitinib (first line) | Advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Recommended by NICE, but not by SMC |

|

Yes |

| Trabectedin Intravenous | Advanced soft tissue sarcoma | Recommended by NICE, but not by SMC |

|

Yes |

| Adalimumab | Severe active Crohn's disease (adults) | Recommended by NICE, but not by SMC |

|

No |

| Efaluzimab | Psoriasis | Restricted use approved by NICE, not recommended by SMC |

|

No |

EMA, European Medicines Agency; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; MTA, multiple technology assessments; NICE, National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; PAS, Patient Access Scheme; PUVA, Psoralen and Ultraviolet Light A; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium.

Table 4.

NICE and SMC final outcome

| Final outcome | NICE | SMC |

| Recommended, No. of drugs (%) | 173 (71.5) | 218 (39.3) |

| Restricted, No. of drugs (%) | 45 (18.6) | 228 (41.1) |

| Not recommended, No. of drugs (%) | 24 (9.9) | 109 (19.6) |

NICE, National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium.

However, the differences are often less than these figures suggest because NICE sometimes approves a drug for very restricted use. For example, NICE approved pimecrolimus ‘for very restricted use for the second-line treatment of moderate atopic eczema on the face and neck in children aged 2–16 that has not been controlled by topical steroids and only where adverse effects such as irreversible skin atrophy were likely’—four restrictions by age, site, previous treatment and risk of adverse effects. SMC rejected it entirely. Although it was recommended by NICE but not by SMC, there may be very little difference in the amount of drug used.

The approval rate was lower for cancer drugs compared to non-cancer ones. NICE appraised 80 cancer drugs, 16 (20%) of which were not recommended. SMC appraised 98 cancer drugs and 29 (29.6%) were not recommended.

Discussion

The NICE STA process was introduced in 2005, with the intention of producing speedier guidance, especially for cancer medication. Our analysis shows that the introduction of the NICE STA process has resulted in speedier guidance but not for cancer drugs. There are some differences in recommendations between NICE and SMC, with SMC rejecting a great proportion of the drugs appraised by both organisations—20% versus 10%.

Reason for difference in recommendations

The reasons for different recommendations might be expected to include:

NICE sometimes allowed cost per QALY exceeding the upper bound of its cost-effectiveness threshold (£30 000 per QALY); especially after the ‘end-of-life’ additional guidance was adopted. However, in several instances, NICE did not report their estimated cost per QALY. SMC can also accept a cost per QALY over £30 000 but seems not to do so to the same extent as NICE.

Different timings, sometimes by years, during which time ‘patient access schemes’, with part-funding by manufacturers, were introduced into NICE calculations.

The modelling from the manufacturer was sometimes different. For example, SMC considered telbivudine to be cost-effective compared to entecavir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, but the manufacturer's submission to NICE did not include entecavir.

Evolution of evidence base.

Longer appraisals provide more opportunities to explore subgroups. Therefore, differences may arise between decisions if one organisation has time to evaluate numerous subgroups within a population.

The difference in timelines means that if a drug is rejected by SMC, the manufacturer may be able to revise the modelling before the drug goes to NICE.

Reasons for lengthier NICE appraisals

The causes for the lengthier process at NICE include consultation7 and transparency. NICE produces a considerably more detailed report and explanation of how the decision was reached. Publically available material includes drafts and final scopes, responses by consultees and commentators and a detailed final appraisal determination. Our impression (two of us have been associated with NICE appraisal for many years) is that the length of the Appraisal Consultation Decisions and Final Appraisal Determination has increased over the years. More recently, we have noted that drugs may be considered more often by the appraisal committee than the expected two times—there are examples of drugs going to three and four meetings. In the STA process, NICE may issue a ‘minded no’ and give the manufacturer more than the usual interval in which to respond with further submissions. This in turn sometimes leads to the Evidence Review Group asking for more time to consider the new submissions. Hence, drugs may received very detailed consideration, but at a time cost.

Marked variability throughout the years (table 1) is most likely caused by small numbers, especially in 2010, where only three STAs are included. Excluding 2010, there has been a general trend for shortening STA times and lengthier MTA times. This is unsurprising, since more complex appraisals would be assessed in an MTA. The longest appraisals (77 months for etanercept in psoriatic arthritis and 60 months for infliximab for ankylosing spondylitis) are explained by the fact that NICE can appraise older drugs if referred by the DH. Both of these were appraised in an MTA with other drugs.

SMC publishes considerably fewer details. NICE appraisal committees deal with two to three STAs per day, allowing for both public and private sessions. SMC is able to deal with six to seven new drugs per day. NICE allows a 2-month period between appraisal committee meetings, 1 month for consultation and then a period for the evidence review group and the NICE secretariat to reflect on these comments and produce a commentary for the second meeting of the appraisal committee. Comments on the draft guidance (the Appraisal Consultation Decision) come from manufacturers (of drug and comparators), clinical groups such as Royal Colleges, NHS staff, patients and the general public through the consultation facility on the NICE website. Figures 1 and 2 (e-version) demonstrate the pathway of appraisal for SMC and NICE.

There is a trade-off between consultation and timeliness. The emphasis by NICE on wide consultation, compared to the less extensive approach by SMC, may simply be a function of size of territory. SMC and its New Drugs Committee have representatives from most health boards. (Note that in Scotland, trusts have been abolished and NHS boards are unitary authorities providing both primary and secondary care, so representatives include managers and clinicians). This in effect allows consultation as part of the process, though mainly with NHS staff rather than patients and public. Patient interest groups have the opportunity to submit written comments to the SMC in support of a new medicine. In contrast, NICE serves a population >10 times the size, and it would not be possible for every Primary Care Trust or trust to be represented on the appraisal committees.

The wide consultation by NICE may reduce the risk of legal challenge. NICE is probably more likely to be challenged than SMC for two reasons. First, NICE guidance is used more as a reference for pricing negotiations by other countries. Second, NICE guidance is fixed for (usually) 3 years, whereas a manufacturer whose medicine has not been recommended can re-submit to SMC at any time.

Consultation by NICE starts well before the actual appraisal, with scoping meetings, and even a consultation on who should be consulted. After the scoping process, NICE makes a recommendation to the DH as to whether a drug should be appraised. The DH then decides on whether or not to formally refer the drug to NICE. This process takes about 3 months (from scoping meeting to formal referral). However, this consultation and referral process usually happens before marketing authorisation and so is unlikely to be relevant to the timelines examined in this paper. Sir Michael Rawlins, chair of NICE, has suggested that for NICE to produce guidance within 6 months of marketing authorisation, it needs to begin the appraisal process about 15 months before anticipated launch.8 In contrast, SMC just looks at all new drugs, so no selection process is needed. This also has the advantage of complete clarity for industry since they know that if they are taking a medicine through the European licensing process, then (when successful) they will definitely be expected to provide a submission by SMC so they can plan for this at an early stage, whereas at that stage, they may not know whether it will be referred to NICE.

Reasons for lengthier appraisal for cancer drugs

One possible explanation for longer timelines for cancer drugs is that many are expensive and hence costs per QALY may be more likely to be on the border of affordability. Another possibility may be that the evidence base for new cancer drugs is limited at the time of appraisal, so the cost per QALY may be more uncertain. This represents a challenge to the appraisal committee, for example, trying to identify subgroups and stopping/starting rules. Additional analysis may be sought from the Evidence Review Group or the manufacturer. All this generates delay.

Strengths and weaknesses

We included only drugs assessed through the technology appraisal programme at NICE and will have missed a few appraised through the guideline process.9 Appraisal outcomes were collected from published tables on the NICE website or SMC annual reports.

One problem is the definition of restricted. We have mentioned above the pimecrolimus example, which is defined as ‘recommended’ by NICE but for very restricted use. Many drugs are recommended by NICE and SMC for use in specialist care only, but this would probably not be regarded as ‘restricted use’ by most people. On other occasions, NICE has approved drugs for narrower use than the licensed indications. For example, liraglutide and exenatide are licensed for use in dual therapy, but NICE has recommended them for use only in triple therapy, albeit with a very few exceptions in dual therapy. Other examples include restriction on the grounds of prior treatment, fitness states and blood glucose levels.

If we adopted a broader definition of restricted, then one could argue that the majority of NICE approvals are for restricted use.

How does this compare to other studies

Only a few studies have looked at the differences between NICE, SMC and the impact of the new STA system.7 10 11 In 2007, Dear et al found a different outcome in five out of 35 comparable decisions (14.3%), with an average of 12 months difference between SMC and NICE.8 In 2008, Barham11 reported that the interval between marketing authorisation and guidance publication was longer for cancer STAs than MTAs.

Dear et al also compared time differences between SMC and NICE in 2007.10 Based on 35 drugs, they estimated the time difference between SMC and NICE to be 12 months. Our results show the difference to be closer to 17 months based on 88 comparable medications; however, when looking at only STAs, this was approximately 12 months. Dear et al also found an acceptance rate of 64% by SMC, although this does not take into account re-submissions. Our data show an acceptance rate of about 80%, which probably reflects our use of only final SMC decisions, some after re-submissions.

Barbieri and colleagues (2009) reviewed decisions on 25 cases where NICE and SMC guidances could be compared and found general agreement in terms of recommendations for use in 23 cases.7 However, they noted that NICE was sometimes more restrictive than SMC, for example, recommending that use be limited to subgroups based on age or failure of previous treatment. They give an example, alendronate for osteoporosis, approved without restriction by SMC but restricted to age and risk status subgroups by NICE. In this case, the appraisal was done under the previous NICE MTA process involving an independent assessment report by an academic group. Barbieri and colleagues also noted that the interval between SMC and NICE appraisals could be as long as 2 years, which could lead to different decisions because of an increasing evidence base.

Mason and colleagues (2010)12 reported that for the period 2004–2008, the STA process had not shortened the timelines compared to MTAs, for cancer drugs, but did not examine non-cancer medications. They also examined time to coverage in the USA and noted that within cancer therapy, hormonal drugs became available faster than chemotherapy drugs, which were in turn faster than biological agents. However, timelines varied among US providers such as Veterans Affairs and Regence.

Barbieri and colleagues (2009) also reviewed the role of independent third party assessment and concluded that it had advantages but that it tended to take longer, as found in this study for non-cancer drugs.7 However, they argued that the third party system, as was provided to NICE by the academic groups, need not prolong the timelines. Indeed, they suggested that basing the appraisal on manufacturers' submissions might lead to delays if there had to be an iterative process of requesting further data or analyses.

How many bodies does the UK need to evaluate new drugs?

In addition to NICE and SMC, there are systems in Wales and Northern Ireland. The All Wales Medicines Strategy Group evaluates new medicines for the NHS in Wales. However, it aims to avoid duplication with NICE, though it may produce interim advice pending a NICE appraisal, and only assesses up to 32 new medicines a year.

In Northern Ireland, there has been since 2006 a system whereby NICE guidance is assessed for suitability for implementation in the Province, with the expectation that is normally will be adopted.13 There is also a Regional Group on Specialist Medicines, which can issue advice on drugs not appraised by NICE.

The existence of the several bodies making policy on new drugs reflects the impact of devolution and separate development of the NHS in the four territories of the UK.

Licensing is now carried out on a Europe—wide basis but that is more of a technical judgement of efficacy and safety. Health technology assessment of new medicines takes into account a wider range of factors such as willingness and ability to pay for the benefits accrued locally, definition of value, accountability to local parliaments, local clinician buy-in and clinical guidelines.

Conclusions

The introduction of the NICE STA system has been associated with reduced time to publication of guidance for non-cancer drugs, but for cancer drugs, the STA timelines are little different from MTA timelines.

Significant differences remain in timescales between SMC and NICE. There are also some differences in guidances between the organisations, but the differences in terms of approved/not approved are often minor, such as approved for very restricted use/not approved.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Ford J, Waugh N, Sharma P, et al. NICE guidance: a comparative study of the introduction of the single technology appraisal process and comparison with guidance from Scottish Medicines Consortium. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000671. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000671

Funding: No external funding.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: JF carried out most of the data extraction and analysis, produced the first draft and is the guarantor. PS carried out some initial analysis and contributed to design of the analysis. NW analysed reasons for the different recommendations in table 3, using published guidances. AW and MS, with considerable experience of SMC and NICE processes, respectively, commented on drafts. MS is a former member of the NICE Technology Appraisal Committee and is also a member of one of the academic groups, which provide assessment reports (for MTAs) or evidence reviews (for STAs). NW was a member of the NICE AC for 5 years and has been a member of three assessment/evidence review groups. All authors commented on the final draft.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Horton R. NICE vindicated in UK's High Court. Lancet 2007;18:547–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cookson R, McDaid D, Maynard A, et al. NICE mess: is national guidance distorting allocation of resources? BMJ 2001;323:743–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinbrook R. Saying no isn't NICE—the travails of Britain's national Institute for health and clinical excellence. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1977–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raftery J. Review of NICE's recommendations, 1999-2005. BMJ 2006;332:1266–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns J. Providing guidance to the NHS: the Scottish medicines Consortium and the national Institute for clinical Excellence compared. Health Policy 2006;76:134–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts G. Are the scots getting a better deal on prescribed drugs than the English? BMJ 2006;333:875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbieri M, Hawkins N, Sculpher M. Who does the numbers? The role of third-party technology assessment to inform health systems' decision-making about the funding of health technologies. Value in Health 2009;12:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlins MD. The decade of NICE. Lancet 2009;25:351–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waugh N, Cummins E, Royle P, et al. Newer drugs for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dear J, O'Dowd C, Timoney A, et al. Scottish Medicines Consortium: an overview of rapid new drug assessment in Scotland. Scott Med J 2007;52:20–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barham L. Single technology appraisals by NICE: are they delivering faster guidance to the NHS? Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:1037–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason A, Drummond M, Ramsey S, et al. Comparison of anticancer drug coverage decisions in the United states and United Kingdom: does the evidence support the Rhetoric? JCO 2010;28:3234–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health, Social Services and public Safety Implementation of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guidance in the HPSS. http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/nice_guidance_01-06.pdf (accessed Aug 2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.