Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the hypothesis that complaints of adverse events related to encounters with healthcare personnel are underreported and to identify barriers to filing such complaints.

Design

A cross-sectional study, where a questionnaire was sent to the respondents asking whether or not they have filed complaints of adverse events. Respondents were also asked whether they have had reasons for doing so but abstained, and if so their reasons for not complaining. The authors also asked about participants' general experience of and trust in healthcare.

Setting

The County of Stockholm, Sweden.

Participants

A random sample of 1500 individuals of the general population registered by the Swedish National Tax Board as living in the County of Stockholm in April 2008. Of the selected group, aged 18–99 years, 50% were women and 50% men. Response rate was 62.1%, of which 58% were women and 42% were men; the median age was 49 years.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were whether the participants have filed a formal complaint with the Patients' Advisory Committee and whether they have had reason to file a complaint but have refrained from doing so. Secondary outcome measures were the participants' general experience of and trust in healthcare.

Results

Official complaints have been filed by 23 respondents (2.7%, 95% CI 1.7% to 3.7%), while 159 (18.5%, 95% CI 15.9% to 21.1%) stated that they have had legitimate reasons to file a complaint but have abstained (p<0.001). The degree of under-reporting was greater among patients with a general negative experience of healthcare (37.3%, 95% CI 31.9% to 42.7%) compared with those with a general positive experience (4.8%, 95% CI 2.4% to 7.2%). The reasons given for abstaining were, among others, ‘I did not have the strength’, ‘I did not know where to turn’ and ‘It makes no difference anyway’. Respondents with a general negative experience also had lower trust in healthcare.

Conclusions

The authors found a considerable discrepancy between the actual complaint rate and the number of respondents stating that they have had reasons to complain but have abstained. This indicates that in official reports of complaints, the authors only see ‘the tip of an iceberg’.

Article summary

Article focus

To test the hypothesis that patients' complaints about adverse events related to negative encounters in healthcare are under-reported.

To study barriers to filing complaints.

To investigate whether trust in and experiences of healthcare are related.

Key messages

Patient complaints about negative encounters are under-reported, disclosing only the tip of an iceberg.

The main barriers to complaints are that patients do not find the strength to make them, do not know where to turn or do not find it worthwhile since they do not believe it will make any difference.

Negative encounters seem to have a negative impact on the exposed patients' trust in healthcare.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study reveals the barriers to complaining in a clear way, which enables healthcare personnel to work actively to provide a more supportive environment for the patients in case of adverse events.

The study sample was small and there was no time-limit regarding events respondents might consider and refer to, which means that our results cannot be compared with official complaint rates.

Introduction

Whereas healthcare by and large is doing its best to improve and promote health, adverse events and complaints occur. Fortunately such incidents are rather unusual. In Stockholm, the capital of Sweden, there are each year around 15 million healthcare visits but only about 8500 registered complaints, including all internal incident reports as well as complaints from patients. However, the number of complaints is steadily increasing.1 2

Patients file their reports with the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen) or with a Patients' Advisory Committee (Patientnämnd). The latter authority also administers complaints about patients' experiences of negative healthcare encounters, that is, complaints concerning how the patient is received by healthcare employees. The main types of complaints addressed to Patients' Advisory Committees concern medical maltreatment (42%), availability (12%), encounters (12%) and monetary issues (7%),2 but the complaints often reveal combinations of reasons for complaining. As an example, a snapshot review showed that around 30% of the complaints registered as concerning maltreatment also brought up negative encounters.3

The general aim of authorities' administration of complaints is to improve patient safety and efficiency in healthcare. The patients' motives for filing a complaint might, however, differ; they may also concern a wish for an explanation, someone to be accountable for what happened, financial compensation or receiving an apology.4–6

We have found no systematic reviews of barriers to complaints regarding negative healthcare encounters focusing on patients. It is, however, well reported that complaints from patients as well as hospital staff regarding adverse events tend to be widely under-reported.7–10 One may wonder whether the same is true for negative encounters. In this paper, based on a questionnaire survey, we test the hypothesis that patients' tendency to file complaints regarding negative encounters in relation to the number of incidents perceived to be worthy of a complaint is under-reported, disclosing only the tip of an iceberg. We also investigate whether trust in and experiences of healthcare are related.

Materials and methods

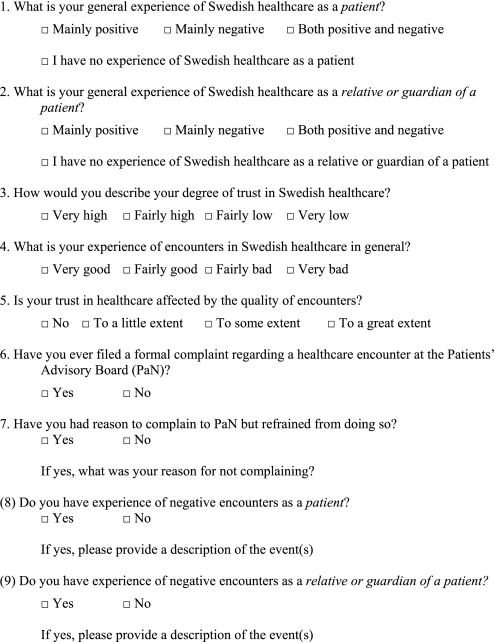

A questionnaire concerning experience of healthcare, negative encounters, trust and complaints to the Patients' Advisory Committee was distributed to a randomly selected study population (n=1500; 50% women and 50% men, aged 18–99 years) registered by the Swedish National Tax Board as living in the County of Stockholm in April 2008. The questionnaire included seven questions with fixed response alternatives and space for comments. In addition, it contained two open-ended questions regarding the respondents' personal experiences of negative healthcare encounters, as patients and as relatives. The focus of the present analysis is on the questions regarding respondents' general experience of Swedish healthcare, their trust in healthcare, whether they have filed a formal complaint with the Patients' Advisory Committee, whether they have had reason to file a complaint but have refrained from doing so, and if so why, and how they perceive their personal experience of encounters with personnel in the healthcare system (appendix 1).

Response options for the question regarding respondents' general experience of Swedish healthcare were ‘mainly positive’, ‘mainly negative’, ‘both positive and negative’ (ie, a mixed experience not clearly pointing in any direction) and ‘no experience’. Since there were no significant differences between those who had a mainly negative general experience and those who had a both positive and negative general experience, we have merged these into one group in the analysis (‘negative general experience’). For estimation of the respondents' degree of trust in healthcare, they were given four response alternatives ranging from ‘very high’ to ‘very low’ (in the analysis the responses were dichotomised into ‘high trust’ and ‘low trust’). Response options regarding having filed or having had reason to file a complaint were ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

As a follow-up question, we asked for the underlying reasons for not filing a complaint when having had reasons to do so. The responses were subjected to qualitative content analysis.11 The reasons presented in the responses were first identified and classified into basic (first-level) themes based on their main content. Thereafter, the basic themes were condensed into a smaller set of second-level themes, where related basic themes were grouped together. Further analysis into third-level themes was conducted but was considered not to add anything of value.

Finally, response options to the question about personal experiences of encounters with healthcare personnel were ‘very positive’, ‘fairly positive’, ‘fairly negative’ and ‘very negative’. In the analysis, they were dichotomised into positive and negative experiences of such encounters.

The results were analysed using Epi-Calc2000 and presented as ORs and proportions with 95% CIs. When testing the iceberg hypothesis, we used the χ2 test, with the significance level 0.05.

Of the sample of 1500, 16 questionnaires were returned due to death or unknown address; altogether 992 participants (62.1%) returned a completed questionnaire (58% were women and 42% men). The median age was 49 years.

The study was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Dnr. 2008/439-31.

Results

Our analysis shows that 23 persons (2.7% (95% CI 1.7% to 3.7%)) have turned to the Patients' Advisory Committee with complaints about the quality of their encounters, while 159 (18.5% (95% CI 15.9% to 21.1%)) stated that they had had legitimate reasons to file a complaint but had chosen to not go through with them (p<0.001). There was an association between type of general experience of healthcare and inclination to file a complaint (OR: 7 (95% CI 4.7 to 10.3); see table 1). We found no significant sex- or age-related differences where complaints were concerned.

Table 1.

The table shows the participants' tendency to complain in relation to different general experiences of healthcare

| Filed a complaint | Had reasons to complain but abstained | |

| General experience of healthcare: | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| Positive (n=553) | 1.5 (0.5 to 2.5) | 7.8 (5.6 to 10) |

| Negative (n=314) | 4.8 (2.4 to 7.2) | 37.3 (31.9 to 42.7) |

| All (n=867) | 2.7 (1.7 to 3.7) | 18.5 (15.9 to 21.1) |

| Missing: (n=5) |

The results are presented as proportions with a 95% CI. Those who had no experiences of healthcare (n=50) are excluded from the presentation. The internal dropout rate for responding to the combinations of these questions was 75 or 7.6%.

A majority of the respondents, 60.3% (95% CI 56.2% to 64.4%), stated that they had a mainly positive general experience of healthcare, 34% (95% CI 29% to 39.6%) had a negative general experience and 5.5% (95% CI 0% to 11.8%) had no experience of healthcare. Of the respondents with a positive general experience of healthcare, 99.5% (CI 99% to 100%) stated that their personal encounters with healthcare personnel had been positive. Of those who had a negative general experience, 19.5% (95% CI 15.1% to 23.9%) reported personal experiences of negative encounters. Comparing the two groups, we found a rather strong correlation (OR: 44.2 (95% CI 13.7 to 142.3)).

We also found a strong correlation between a general negative experience and low trust in healthcare on the one hand and a general positive experience and high trust on the other (OR: 21 (95% CI 11.1 to 40.3)). Of those who had reasons to file a complaint but did not do so, one-third reported that they had low trust in healthcare. This can be compared with those who had no reason for filing a complaint; nine of the 10 had high trust in healthcare (p<0.001; table 2).

Table 2.

The table displays the proportions (with a 95% CI) of the respondents who had high trust in healthcare in relation to whether they had filed a complaint to the Patients' Advisory Board, whether they had had reasons for filing a complaint and their general experience of healthcare

| High trust | |

| Never complained (n=843) | 87% (84.7 to 89.3) |

| Actually complained (n=23) | 60.9% (41 to 80.8) |

| Missing (n=6) | |

| No reasons for complaining (n=703) | 90.9% (88.8 to 93) |

| Reasons for complaining but abstained (n=163) | 66.7% (59.5 to 73.9) |

| Missing (n=6) | |

| Positive experiences of healthcare (n=551) | 97.6% (96.3 to 98.9) |

| Negative experiences of healthcare (n=312) | 66.3% (61.1 to 71.5) |

| Missing (n=9) | |

Those who had no experiences of healthcare (n=50) are excluded from the presentation. The internal dropout rate for responding to the combinations of these questions ranged between 76 and 79, on average 7.8%.

Respondents stating that they had had reason to file a complaint regarding negative encounters with healthcare personnel but abstained were asked to comment why they abstained. Input was received from 140 respondents. Seventeen distinct first-level themes were identified, and from these, five second-level themes emerged: ‘weakness’, ‘futility’, ‘lack of knowledge’, ‘mercifulness’ and ‘other action taken’. The most common responses (first-level themes) were ‘I did not have the strength’, ‘I did not know where to turn’ and ‘It makes no difference anyway’. Other reasons stated were, for example, that it was too difficult and that the respondent was afraid of the consequences (see table 3).

Table 3.

Reasons for not filing official complaints to the Patients' Advisory Committee; number of respondents=159.

| First-level themes | Second-level themes |

| I did not have the strength (n=39) | Weakness |

| I was afraid of the consequences (n=8) | |

| I do not like to complain (n=3) | |

| I did not want to relive the trauma (n=1) | |

| I was not the closest relative (n=1) | |

| It makes no difference anyway (n=17) | Futility |

| I had other priorities (n=14) | |

| It was too difficult (n=13) | |

| I did not have time to do it (n=8) | |

| The damage was already done (n=5) | |

| I did not know where to turn (n=18) | Lack of knowledge |

| Lack of knowledge I did not know/think I had that option (n=4) | |

| I did not complain out of consideration for the accused person (n=3) | Mercifulness |

| I did not complain due to collegial relations (n=2) | |

| I complained directly at the hospital (n=4) | Other action taken |

| No reason stated (n=19) | |

Discussion

Comparing the number of respondents who have filed a complaint with the number who have not but who think they had legitimate reasons to do so, we found a significant difference, indicating that the complaints filed show only the tip of an iceberg. The ratio between filed complaints and non-reported complaints that, according to the respondents, would qualify for a formal complaint was approximately 1:7 in the survey population. Among those with a general negative experience of healthcare, it was approximately 1:8.

In the total study sample, almost all participants had had experience of healthcare—only 50 participants had not. We found a strong correlation between a positive/negative general experience of healthcare and personal experiences of positive/negative encounters with healthcare personnel. These findings might indicate that the respondents do not clearly distinguish between medical maltreatment and negative encounters or that these experiences interact; they are both important for the impression and assessment of healthcare services. Other studies have indicated that negative encounters might become a threat to patient safety since they affect communication and patient behaviour.12–14 Earlier studies have also indicated that patients who have been received in a hostile, rude or otherwise negative manner are more predisposed to go through with malpractice claims.6 15 Our study shows that a larger percentage of those with a negative general experience of healthcare file complaints compared with those with a positive general experience.

The encounter's effect on trust

Not surprisingly, those with a negative general experience of healthcare who had filed a complaint or had had reasons for doing so reported lower trust in healthcare at the time of the survey compared with those with a positive general experience who had not filed a complaint and had had no reason for doing so. A large proportion of the latter group had high trust in healthcare. Trust seems to be important for several reasons, for example, for concordance and ultimately for patient safety.14 16 If trust in healthcare is jeopardised by negative encounters, it seems important also to examine more carefully the bottom of the iceberg, that is, to study those who do not file complaints.

Reasons for not complaining

Weakness, perceived futility and lack of knowledge about how to complain (or even that there was such an option) were second-level themes that covered most of the reported reasons for not having filed a formal complaint. Many of the most frequent reasons have in common that the respondents felt that the obstacles were too great or that it required more strength than they could muster. Quite a few express the belief that reporting adverse events is futile, implying distrust regarding either the ability or the willingness of healthcare to actually take notice of and learn from the complaints. Furthermore, some respondents chose not to complain due to fear of reprimands, such as receiving worse care or having their treatment withdrawn—an alarming result that also implies a considerable lack of trust among some of the respondents.

Improvements of the reporting system

These responses identify the main barriers to receiving input via formal complaints. The obstacles prevent learning about complaints and are therefore liable to have negative effects on the development of healthcare services and prevention of future adverse events. The responses also indicate that if the healthcare system wants this kind of input, it needs to offer patients more support. Better provision of information seems to be part of the solution since some respondents were not even aware that they could file a formal complaint or did not know how to do it. One can also conclude from the responses that discontented patients might need more hands-on active support in getting their complaints filed.

Validity

There was no limit in time regarding which events respondents might consider and refer to. This means that our results cannot be compared with official reports presenting annual complaint rates. For this reason, we have not focused on comparisons with earlier research but on relative associations within the present data and the manifest reasons for not filing complaints.

Conclusions

The present Swedish study indicates that healthcare complaints filed regarding encounters reveal only the tip of an iceberg. Complaints seem to be considerably under-reported, especially among those with a negative general experience of healthcare. In order to develop and improve the quality of healthcare encounters and services, by assuring critical feedback, it is important that healthcare providers offer more information and support to patients who want to make complaints. Since differences in healthcare systems and ways to handle complaints might affect the tendency to file complaints, and the difficulty to do so, it is not clear to what extent these findings are generalisable to other countries. Further research is needed.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Questions asked in the survey.

|

Footnotes

To cite: Wessel M, Lynøe N, Juth N, et al. The tip of an iceberg? A cross-sectional study of the general public's experiences of reporting healthcare complaints in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000489. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000489

Funding: This work was partly funded by Stockholm County Council.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden.

Contributors: MW is the main author of the present paper and took a leading part in its conception and design, statistical analysis, interpretation of the results and writing of the paper. NL contributed with the original idea for the present study, took part in its conception and design, participated in the statistical analysis and contributed substantially to the interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript. NJ contributed to the conception and design of the study and has critically revised the manuscript. GH contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study and to the interpretation of the results. He has taken a leading role in writing the paper.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

References

- 1.Stockholms läns landsting Vården i siffror. Årsbokslut. (Stockholm County Council. Healthcare in figures. Annual report, 2007). 2007. http://www.sll.se/Handlingar/HSN/2008/ (accessed 28 Mar 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.SLL Patientnämndens Årsrapport. Stockholm County Council (2010) Annual report, Patients' Advisory Committee. 2010. http://www.patientnamndenstockholm.se/res/Arsrapport/Aarsrapport-2010.pdf (accessed 31 Aug 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessel M, Helgesson G, Lynöe N. Experiencing bad treatment: qualitative study of patient complaints concerning their reception by public healthcare in the County of Stockholm. J Clin Ethics 2009;4:195–201 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simanowitz A. Standards, attitudes and accountability in the medical profession. Lancet 1985;2:546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels A, Burn R, Horarik S. Patients' complaints about medical malpractice. Med J Aust 1999;170:598–602 J Clin Ethics 2009;4:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent CA, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet 1994;343:1609–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barach P, Small S. Reporting and preventing medical mishaps: lessons from non-medical near miss reporting systems. BMJ 2000;320:759–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawton R, Parker D. Barriers to incident reporting in a healthcare system. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:15–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christiaans-Dingelhoff I, Smits M, Zwaan L, et al. To what extent are adverse events found in patient records reported by patients and healthcare professionals via complaints, claims and incident reports? BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen S, Neale G, Schwab K, et al. Hospital staff should use more than one method to detect adverse events and potential adverse events: incident reporting, pharmacist surveillance and local real-time record review may all have a place. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:40–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to its Methodology. 2nd edn California: Sage Publications Inc, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong L, de Haes J, Hoos A, et al. Doctor–patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:903–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstein A, O'Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:464–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient Safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:76–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA 1997;277:553–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leape LL, Woods DD, Hatlie MJ, et al. Promoting patient safety by preventing medical error. JAMA 1998;280:1444–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.