Abstract

Introduction

Evidence produced by researchers is not comprehensibly used in practice. National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire's strategy for closing the research to practice gap relies on the use of ‘Diffusion Fellows’ (DFs). DFs are seconded from the local healthcare economy to act as champions for change, translating and disseminating knowledge from practice into the research studies and vice versa, taking the knowledge developed by academics back into their own practice environments. This paper outlines the rationale and design of a qualitative evaluation study of the DF role.

Methods and analysis

The evaluation responds to the research question: what are the barriers and facilitators to DFs acting as knowledge brokers and boundary spanners? Interviews will be carried out annually with DFs, the research team they work with and their line managers in the employing organisations. Interviews with DFs will be supplemented with a creative mapping component, offering them the opportunity to construct a 3D model to creatively illustrate some of the barriers precluding them from successfully carrying out their role. This method is popular for problem solving and is valuable for both introducing an issue that might be difficult to initially verbalise and to reflect upon experiences.

Ethics and dissemination

DFs have an important role within the CLAHRC and are central to our implementation and knowledge mobilisation strategies. It is important to understand as much about their activities as possible in order for the CLAHRC to support the DFs in the most appropriate way. Dissemination will occur through presentations and publications in order that learning from the use of DFs can be shared as widely as possible. The study has received ethical approval from Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee and has all appropriate NHS governance clearances.

Article summary

Article focus

Qualitative evaluation.

Knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning roles.

Creative research methods.

Key messages

Real-time evaluation of Diffusion Fellow role.

Understand what knowledge brokers and boundary spanners do and what helps/hinders this.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Longitudinal study.

Formative evaluation.

Introduction

Evidence stemming from healthcare research is known to be poorly implemented and used,1 with problems involving the production of the knowledge, the sharing, translation or the mobilisation of knowledge, the reception that the knowledge receives once in the world of practice and the use of the knowledge.2–4 Numerous approaches have been suggested with regard to how research evidence should be translated into practice and how it should be allowed to make an impact in healthcare.5–9 The National Institute for Health Research has taken steps to address the problem of research and evidence implementation by establishing the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) programme. Funded for 5 years (2008–2013), nine CLAHRCs operate across England, with the remit to close the research to practice gap. This paper reports on one aspect of the implementation and knowledge mobilisation strategy applied by the National Institute for Health Research CLAHRC for Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire (NDL). CLAHRC-NDL is built around a conceptual model of organisational learning, which sees change as issue centred and socially contextual.

The worlds of research and practice are fractured and disconnected from one another. This creates a lack of knowledge and wide gulfs in understanding each other's perspective.6 9 Knowledge is contested by each community and shaped and reshaped by each group to meet its own needs and demands; it is a social construction, produced, embedded and mediated by social and political processes.10 11 Given that knowledge is socially contingent, it follows therefore that its mobilisation also takes place through a social process of inter-connected groups of individuals and communities. Formal communities of practice, together with an individual's interpersonal networks, are key to mobilising knowledge and as an extension of this, in getting research implemented. These groups mould and shape (translate) the information to fit the contextual needs of each network, group or organisation. Greenhalgh et al2 described how “knowledge depends for its circulation on interpersonal networks, and will only diffuse if these social features are taken into account and barriers overcome.” Change does not occur from the top–down; it is not an individualised action nor something that can be copied from one place to another. Change is issue centred, home grown and collectively implemented.12 Having a contextual understanding of the network or community of practice into which change is to be actioned and implemented is critical and is something that academics, as outsiders, are not often able to access.

To address this, CLAHRC-NDL is using individuals seconded from our NHS partner organisations to act as change agents and champions for innovation, whom we have called ‘Diffusion Fellows’ (DFs). The DF model is a unique element of CLAHRC-NDL's approach to the implementation of health and social care research into practice. DFs bridge the gaps between research and practice, filling the ‘structural holes’13 between the two communities that impede the translation and implementation of evidence. They bring experiential knowledge and assist with the co-design of the studies to ensure that they are fit for practice. Consequently, DFs aid knowledge mobilisation and evidence implementation at the earliest possible stage, rather than waiting until the end of the study to find that the intervention is unsuitable for the health and social care environment.

DFs are seconded to CLAHRC-NDL for 1 day per week for the life of the CLAHRC. They work inwards to the research project, advising on the design of the study; this continues throughout the project in relation to identifying and solving practice-based ‘real-world’ issues and practicalities. Moreover, together with the research teams, DFs also work outwards, from the research base back into practice. In enacting this role, DFs are translating the evidence produced from the language of academics into something with more resonance for NHS and social care audiences. In doing this dissemination role, they are acting as knowledge brokers, sharing and mobilising knowledge,6 9 and boundary spanners, crossing language, understanding and practice divides.3 14 DFs inhabit a variety of diverse communities of practice and networks, and so have the opportunity to foster shared understandings among a wide and diffuse population, both across the NDL region and nationally, through professional and occupational networks. This study evaluates the role of the DFs.

Methods and analysis

The DF programme is an important component of CLAHRC-NDL's research to practice strategy. This evaluation seeks to understand more about the knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning roles of the DFs in order to learn from and improve the experiences of our DFs. The research design outlined below captures the nature and development of the DF role, DF involvement and embedding within the research teams, and the enactment of the DF's important translation, knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning roles.

Previous research has found that knowledge brokers are key facilitators of organisational change and development and can have a role in implementing research findings into practice.15–17 However, there is limited evidence about what such roles actually entail.18 19 Qualitative methods will therefore be used to identify, explore and describe the DFs' roles and activities and to develop an understanding of barriers and facilitators with regard to knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning practices in healthcare and social care.

Study objectives

In carrying out this study, the primary research question is: what are the barriers and facilitators to DFs acting as knowledge brokers and boundary spanners across NDL. Data will be collected on the rationales, expectations and experiences of being a DF, how relationships between the DF and the CLAHRC teams develop and to establish what support CLAHRC needs to offer to DFs, the research teams and employing organisations.

Inclusion criteria

In order to participate in the study, participants should meet one of the following inclusion criteria. An individual should

Be seconded to CLAHRC-NDL as a DF,

Line manage or be responsible for the DF in their employing organisation or

Be a representative of the CLAHRC-NDL research team that the DF works into.

Individuals who do not meet these criteria, or any who do but are under the age of 18 years or who are unable to give their informed consent, will be precluded from taking part.

Sampling strategy

This study relies on a defined population-sampling frame and a purposive sampling strategy. All CLAHRC-NDL DFs will be invited to participate in the study (N=25), which will take place over 3 years (data collected commenced during Spring 2011 and will continue until Summer 2013). Following their first interview (year 1), DFs will be asked to contact their line manager with an invitation from the research team, requesting their involvement in the study. Subject to the line manager's consent, the DF will pass on their details to the research team, who will make contact with the manager, and schedule the interview. A member of the DF's CLAHRC-NDL research team will be approached to participate in the interviews. Initially, the Principal Investigator will be contacted, but it may be that this person has little contact with the DF. In this scenario, the Principal Investigator will be asked to nominate someone else from their research team who works more closely with the DF. In subsequent years of the study, all participants will be contacted by the research team and asked to consent to be re-interviewed.

Triad of interviews

In-depth qualitative interviews will be carried out annually with DFs, their line managers and representatives from the CLAHRC-NDL research teams. A topic guide will be used to aid the focus of the interview (see table 1 for an outline of the questions asked). This allows for greater flexibility in the questioning strategy than more rigid interview schedules.20–22 Moreover, interviews are likely to follow an informal format, as the research team have existing relationships with the majority of interviewees and as such are likely to be more akin to a ‘conversation with a purpose’23 than a more formal interview situation. It is envisaged that this shared understanding and rapport will assist in creating an open situation in which experiences (positive and negative) can be openly shared, without participants fearing they are being too critical. However, all respondents will be assured of the anonymity of the data and that the interviews are intended to be a non-judgemental but formative learning opportunity for both the individuals and CLAHRC-NDL.

Table 1.

List of interview questions

| DF interview questions (year 1) | DF interview questions (years 2 and 3) | Line manager interview questions (all years) | CLAHRC team interview questions (all years) |

|

|

|

|

CLAHRC, Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care; DF, Diffusion Fellow; NDL, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire.

The interviews will explore how, why and with whom DFs share knowledge and the boundaries and obstacles that hinder or obstruct this. In addition, DFs will be encouraged to talk about their rationales for wanting to become a DF, their expectations of the DF role and their background and previous experiences of being involved in implementing change. They will be asked to talk about their DF activities during the previous year, how their DF secondment fits with their work with their employing organisation, any challenges that they have faced and how they work with the research team. Interviews with the DFs' line managers and CLAHRC-NDL research team will explore their perceptions of role, in relation to the CLAHRC study and the employing organisation. The list shown in table 1 is neither exhaustive nor a series of questions that must be rigorously followed; the flexibility of the topic guide offers space and the opportunity for participants to raise other issues which they might consider to be pertinent. All the interviews will be audio recorded (with participants' consent) and will be transcribed verbatim.

Creative mapping and visual research

In addition to the face-to-face interviews, the DFs will be invited to participate in a creative mapping exercise. This additional source of data provide ‘something extra’ and will offer the DFs the opportunity to elaborate on some of the points that they have made during the interviews, as well as introduce any thoughts and ideas that they find difficult to verbalise. Creative research methods provide an opportunity for reflection and elicitation of meanings and experiences that DFs may not voice or to holistically draw together a number of experiences, to represent something or ‘do’ some sense making. Bagnoli24 describes how “not all knowledge is reducible to language [and] non-linguistic dimensions allow us to access and represent different levels of experience.” Utilising a creative mapping approach therefore offers an additional way of collecting data on the DFs' experiences of enacting the knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning roles.

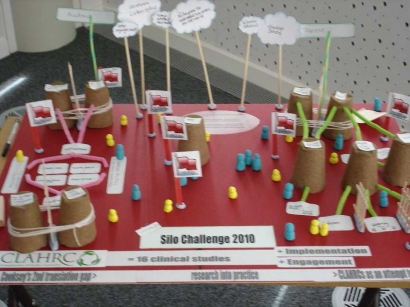

The idea for the creative mapping element of the study developed from a team exercise designed to define what were seen as the challenges to the spread and sustainability of the CLAHRC's way of working (see figure 1). Further investigation revealed that our amateur efforts were similar to the Lego Serious Play business development tools. Lego Serious Play involves groups of individuals working together to problem solve issues in a creative and imaginative way, by building models using Lego bricks. It is argued that “this kind of hands-on, minds-on learning produces a deeper, more meaningful understanding of the world, and its possibilities (by) deepen(ing) the reflection process and support(ing) an effective dialogue.”25 Lego Serious Play builds on Roos and Victor's26 27 work on leadership and strategy in organisations. They described how the interplay of knowledge, identity and meaning within a contextual sphere creates meaning and how story-telling, sparked from the creative process, enables individuals to move from intuition to something concrete.

Figure 1.

Exemplar knowledge brokering map.

The model shown here (produced by the research team) shows organisational ‘silos’ (upturned flower pots) that impede the flow of knowledge, links between organisations (pipe cleaners), people working within the network, red warning flags and ‘thought-clouds’ containing suggestions for enhanced practice.

In designing the creative mapping exercise, Gauntlett's28 work has been influential. He described how creative interviews allow “participants to spend time applying their playful or creative attention to the act of making something symbolic or metaphorical, and then reflecting on it.” The process involves “people messing around with materials, select things, manipulate the thing in question until it approaches something that seems to communicate meanings in a satisfying manner.”29 Consequently, “the idea is that going through the thoughtful, physical process of making something…an individual is given the opportunity to reflect, and to make their thoughts, feelings or experiences manifest and tangible. This unusual experience gets the brain firing in different ways, and can generate insights which would most likely not have emerged through direct conversation.”29

This strategy will allow the DFs to physically ‘map’ the connections that they have developed, highlight where obstacles and difficulties exist and how these are hindering their knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning roles. If they choose to participate in this component of the study, DFs will be asked to build a model that illustrates the interactions they have with others as part of their role, producing a diagrammatic ‘map’ of relationships and visually illustrating the strength or weakness of connections between individuals, partner organisations and other stakeholders. In doing this, DFs will build their own 3D knowledge mobilisation and brokering map, physically demonstrating the boundaries and silos that they cross, obstacles and barriers that they face, the processes they have worked through, and the networks and links that they have developed.

Story-telling and story-making are an active endeavour, calling on participants to reflect, elaborate, refine and evaluate as they go along.30 In relation to creative research methods, this is done through “thinking with hands to understand and unlock new perspectives.”25 Consequently, talk and sense making are literally about what participants put on the table. Gauntlett28 described creative research methods as a process “in which people are asked to make things, and reflect on them, rather than having to speak instant reports or ‘reveal’ themselves in verbal discussion” (original emphasis). Words and visual images together create meaning.

In carrying out the creative mapping exercise, it is hoped—as advocates of Lego Serious Play have found—that in building the 3D models, participants are able to surface the ‘undiscussables’ or illustrate the complex and challenging demands they face in carrying out their DF role. This process of discovery and reflective sense making is likely to occur in a more direct way than polite conversational rules allow. What's more, not only do images enable reflection on otherwise tacit, unrecognised, unspoken phenomena31 32 but they “encode an enormous amount of information in a single representation.”33

Visual methods have become increasingly popular as research tools, as they provide a means for participants to reflect upon and provide further elicitation and explanation about their practice.34 35 However, to date such methods have been underutilised. Harrison36 recognised this omission, describing it as “a neglected dimension in our understanding of social life.” She argued that visual methods should be seen as a form of ‘photobiography’, whereby participants can make sense of their self in relation to the social and the physical context.

By including this form of creative ethnography in the research design, DFs will be able to “tell the story of how people, through collaborative and indirectly independent behaviour, create the ongoing character of particular social places and practices.”37 It will call for them to think “outside of the box, generating new ways of interrogating and understanding the social.”24 Moreover, interacting with the diagrams “provides a basis for further interviewing and communication between researcher and participants.”24 Therefore, while each DF is building their knowledge-brokering map, they will be asked to discuss its content. This discussion will be audio recorded, with participants' consent, while the map construction will be video recorded (again with consent) to capture the building process and final design. The video camera will be positioned so that the recording captures the building and editing of the map and physical movement of components, along with the verbal explanation of each activity. Consequently, while it is important to be able to capture the hands and voice of the DF, the recording will not include their face, head or body, thus preventing any visual identification of the individual involved.

Each year, the model will be rebuilt by a member of the research team (using the video from the previous year as an aide memoir), following which DFs will be asked to amend and develop their model, depicting if new boundaries have been crossed or formed, if barriers have been broken down or new ones formed, if new relationships and networks have been fostered or if existing ones have been maintained or are unsustainable.

Taken together, data collected from the interviews and the creative maps will enable us to meet the study objective and thus gain a better understanding and appreciation of the role of the DFs, especially in relation to their knowledge-brokering and boundary-spanning activities.

Longitudinal timeline

Subject to participants' agreement, interviews will be repeated on an annual basis to revisit issues discussed in previous years and to discuss any developments in the operationalisation of the DF role since the start of the study. Taking place over 3 years (2011–2013), the longitudinal nature of data collection will allow reflections and sense making to be recorded over time, as the DF role and its impact develops, and reacts to the changing NHS and social care infrastructure and climate.

In study year 3 (2013), DF interviews will be carried out twice, to allow for a final examination of the DF programme prior to the end of CLAHRC-NDL funding (30 September 2013). Interviews with DFs will take approximately 1–1½ h each time. Interviews with line managers and CLAHRC research teams are likely to last a maximum of 30 min each time. In total, just <220 interviews will be carried out (DFs = 100, line managers = 75, CLAHRC representatives = 39).

Data analysis

Data will be analysed at each time point, as well as summatively at the end of the evaluation. The data will be analysed using conventional qualitative methods that seek to identify themes, which are relevant both across and in cases.21 22 38–40 Analysis will be inductive, thematic and grounded in the theories of knowledge brokering and knowledge mobilisation.6 9 14 41 This approach is complementary to CLAHRC-NDL's wider theoretical framework of organisational learning, which is a situated real-time approach to examining the translation of research evidence into practice.5 10 42

Thematic analysis provides a concise, coherent, logical, non-repetitive and interesting account of the story the data tell. To reach this end point, it requires the researcher to spend time engaging with the data, reading the interview transcriptions, listening to the audio recordings of interviews and watching the map building videos. This provides the necessary surface for the writing down of early thoughts, ideas and reflections, prompted by the interview data. Engaging with the data generates understanding, insight and familiarity, which are the building blocks of analysis. Once the data have undergone this preliminary analysis, all the data extracts that have been coded will be sorted in a more general sense and examined in order to identify the wider themes of which they are representative. Developing themes usually entails selecting extracts from the data, which will be clearly labelled with the unique identifying code of the informant and with the place (line number range) in the interview from which the extract originates. Lastly, the data extracts will be accompanied by a narrative, which elaborates why extract is analytically interesting.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has no material ethical considerations, although it is appreciated that the interviews may touch upon sensitive issues. Participants will be assured of their anonymity and that the primary purpose of the evaluation is to learn from and improve their experiences, which cannot occur if a positive-spin is placed on their comments and reflections.

The role of the DF is new and untested. This evaluation will work with the DFs and those they interact with to understand the role while also seeking to make real-time improvements. DFs have an important role within CLAHRC-NDL; in actively bridging the research to practice gap, they are at the front-line of efforts to make academic research more clinician friendly and for practice to be more receptive to empirical evidence. Their experiences therefore offer valuable learning points, both for practice and to extend academic theory-driven work on boundary spanning and knowledge brokering.

Recommendations for improved practice will be co-produced with the study steering committee, whose membership is compiled of the DFs. Internal dissemination will occur through DF bimonthly learning sets, CLAHRC-NDL management meetings and knowledge exchange events which are held frequently and available to all members of CLAHRC-NDL. External dissemination activity will see presentations to academic and practice audiences, both locally and nationally, and publications in academic and practice journals.

At both an operational and theoretical level, it is anticipated that the evidence collected will assist with the development of typologies or role descriptions that can enhance the understanding of all those involved with the DF role. Michaels18 described how little is known about what knowledge brokers actually ‘do’ in carrying out their role. While CLAHRC-NDL generically describes the activities DFs undertake as: providing hands on advice, acting as a CLAHRC ambassador, facilitating change and building capacity, all within the remit of getting research into practice, what this means on the ground varies between the DFs.

In responding to the overall study objectives and research question, this evaluation study will inform the development of a guiding structure, which will support the DFs, their line managers and the CLAHRC teams in enabling the DFs to carry out their important knowledge-brokering role. This framework will be sincere to the organisational learning ethos of CLAHRC-NDL and our emphasis on situated, contextual solutions, and will as such be flexible to allow for the contextual variation that all of our DFs face. At a wider level, it is hoped that the study will contribute to the ‘implementation’ debate more generally, through a real-world, real-time longitudinal analysis of the experience of change agents, and lessons from this that might be packaged for other knowledge brokering or change implementation efforts in many of other contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Cecily Palmer and Alison Seymour were involved in the conceptual design of the study but took no part in writing this paper. The author is grateful to Cecily Palmer and Melanie Jordan for their helpful comments while drafting the paper.

Footnotes

To cite: Rowley E. Protocol for a qualitative study exploring the roles of ‘Diffusion Fellows’ in bridging the research to practice gap in the Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC-NDL). BMJ Open 2012;2:e000604. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000604

Funding: This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) as part of the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care—Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. CLAHRC-NDL is funded through a matched-funding scheme by the National Institute of Health Research, The University of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, NHS Nottingham City, NHS Nottinghamshire County, NHS Bassetlaw, Derbyshire Healthcare Foundation Trust, NHS Derby City, NHS Derbyshire County and Lincolnshire Partnership Foundation Trust. The funders had no role in the study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of subsequent reports or the decision to submit reports for publication. The study's principal investigator, ER has sole responsibility for all these tasks.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 10/H0408/95; Principal Investigator: ER).

Contributors: ER was the sole author of this paper. She led the conception and design of the study, drafting the article and had final approval of the version to be published.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cooksey D. A Review of UK Health Research Funding. London: The Stationary Office, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organisations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald L, Ferlie E, Wood M, et al. Interlocking interactions, the diffusion of innovations in healthcare. Hum Relat 2002;55:1429–49 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 2003;362:1225–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutley SM, Davies HTO. Developing organisational learning in the NHS. Med Educ 2001;35:35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies HT, Nutley S, Walter I. Why ‘knowledge transfer’ is misconceived for applied social research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:188–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutley SM, Walter I, Davies HTO. Using Evidence: How Research Can Inform Public Services. Bristol: Polity Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham ID, Tetroe J. Some theoretical underpinnings of knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:936–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomas J. The in-between world of knowledge brokering. BMJ 2007;334:129–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JS, Duguid P. Organizational learning and communities of-practice: toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organ Sci 1991;2:40–57 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin B. Thinking About Knowledge Mobilization: A Discussion Paper Prepared at the Request of the Canadian Council on Learning and the social Sciences and Humanities research Council. http://webspace.oise.utoronto.ca/∼levinben/thinking%20about%20KM%202008.pdf (accessed Oct 2011).

- 12.Bate P. Changing the culture of a hospital: from hierarchy to networked community. Publ Admin 2000;78:485–512 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burt RS. Structural Holes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlile PR. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: boundary objects in new product development. Organ Sci 2002;13:442–55 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartunek J, Trullen J, Bohet E, et al. Sharing and expanding academic and practitioner knowledge in healthcare. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003;8:62–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swan J, Scarborough H, Robertson M. The construction of ‘communities of practice’ in the management of innovation. Manag Learn 2002;33:477–96 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams P. The competent boundary spanner. Publ Admin 2002;80:103–24 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaels S. Matching knowledge brokering strategies to environmental policy problems and settings. Environ Sci Pol 2009;12:994–1011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez RM, Gould RV. A dilemma of state power: brokerage and influence in the national health policy domain. Am J Sociol 1994;99:1455–91 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert N. Researching Social Life. London: Sage, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. California: Sage, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silverman D. Qualitative Research. 3rd edn London: Sage, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess RG. The unstructured interview as a conversation. In: Burgess RG, ed. Field Research: A Sourcebook and Field Manual. London: Routledge, 2005:164–9 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnoli A. Beyond the standard interview: the use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual Res 2009;9:547–70 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lego Serious Play: Introduction to Lego Serious Play. http://www.seriousplay.com/19483/HOW%20TO%20GET%20IT (accessed Oct 2011).

- 26.Roos J, Victor B. Towards a new model of sense-making as serious play. Eur Manag J 1999;17:348–55 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roos J, Victor B, Statler M. Playing seriously with strategy. Long Range Plann 2004;37:549–68 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gauntlett D. Creative Explorations. New Approaches to Identities and Audiences. London: Routledge, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gauntlett D. Making is Connecting: The Social Meaning of Creativity, from DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen and Associates: The Science of Lego Serious Play. http://www.rasmussen-and-associates.com/downloads/science_of_LSP.pdf (accessed Oct 2011).

- 31.Blinn L, Harrist AW. Combining narrative instant photography and photo-elicitation. Vis Anthropol 1991;4:175–92 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latham A. Research and writing everyday accounts of the city: an introduction to the diary-photo-diary-interview method. In: Knowles C, Sweetman J, eds. Picturing the Social Landscape: Visual Methods and the Sociological Imagination. London: Routledge, 2004:117–31 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grady J. Working with visible evidence: and invitation and some practical advice. In: Knowles C, Sweetman J, eds. Picturing the Social Landscape: Visual Methods and the Sociological Imagination. London: Routledge, 2004:18–32 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iedema R, Forsyth R, Georgiou A, et al. Video research in health. Visibilising the effects of computerising clinical care. Qual Res J 2007;6:15–30 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carroll K, Iedema R, Kerridge R. Reshaping ICU ward round practices using video-reflexive ethnography. Qual Health Res 2008;18:380–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison B. Seeing health and illness worlds—using visual methodologies in a sociology of health and illness: a methodological review. Sociol Health Illn 2002;24:856–72 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shrum W, Duque R, Brown T. Digital video as research practice: methodology for the millennium. J Res Pract 2005;1 http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/6/11 (accessed Oct 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, eds. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge, 1994:173–94 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huberman AM, Miles MB. Data management and analysis methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. California: Sage, 1998:179–210 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, et al. Health research funding agencies' support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q 2008;86:125–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yannow D. Seeing organizational learning: a ‘cultural’ view. Organization 2000;7:247–68 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.