Abstract

Rh(III)-catalyzed arylation of imines provides a new method for C–C bond formation, while simultaneously introducing an α-branched amine as a functional group. A detailed mechanistic study provides insights for the rational future development of this new reaction. Relevant intermediate Rh(III)-complexes have been isolated, characterized, and their reactivity in stoichiometric reactions with relevant substrates have been monitored. The reaction was found to be first order in the catalyst resting state and inverse first order in the C-H activation substrate.

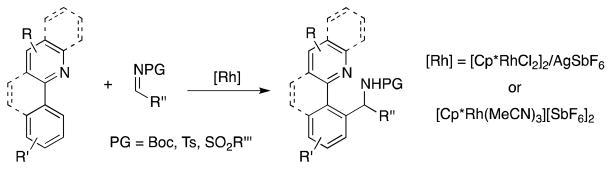

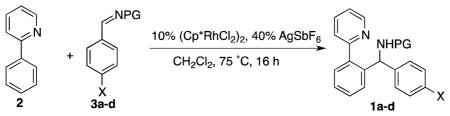

Arylation of alkenes and alkynes have been well explored in the area of chelation-controlled rhodium-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization.1 Our groups, and the Shi group, recently extended the scope of such reactions to Rh(III)-catalyzed arylation of imines (Scheme 1).2 This transformation provides a convenient synthesis of α-branched amines with simultaneous C–C bond formation. The reaction can be conducted under mild conditions and displays excellent functional group compatibility. Further advancements in this field include the arylation of other polarized C–X multiple bonds such as aldehydes,3 isocyanates,4 isonitriles,5 and carbon monoxide.6

Scheme 1.

Rh(III) Catalyzed Imine Arylation

While the mechanism of chelation-controlled Rh(III)-catalysis assisted by acetate has been explored,7 only limited information is available for the arylation of imines employing either [Cp*Rh(MeCN)3][SbF6]2 or a mixture of [Cp*RhCl2]2 and AgSbF6 as a catalyst. Herein, we report an investigation of the mechanistic steps of the reaction from catalyst initiation to C–C bond formation, and subsequently, catalyst propagation (product release). Relevant intermediates were isolated and characterized by X-ray diffraction. In an unusual finding, the rate law of the reaction was determined, revealing substrate inhibition of the catalyst.

For our mechanistic investigations, we first studied the arylation of N-protected aromatic imines bearing N-tosyl, N-Boc, and N-isopropoxycarbonyl protecting groups with 2-phenylpyridine 2 (Table 1). For Boc-amine 1a a considerably higher yield was observed when a twofold excess of 2 with regard to imine 3a was employed (Table 1, entry 2 and 3).2a

Table 1.

Protecting Groups in Imine Arylationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | PG | X | product | % yield |

| 1 | Ts | H | 1a | 402a |

| 2b | Boc | H | 1b | 552a |

| 3 | Boc | H | 1b | 822a |

| 4 | Boc | CF3 | 1c | 952a |

| 5 | C(O)OiPr | H | 1d | 81 |

0.05 mmol of 3, 0.10 mmol of 2, 5.0 μmol of [Cp*RhCl2]2, 0.02 mmol of AgSbF6, 0.70 mL of CH2Cl2, T = 75 °C, t = 16 h.

0.05 mmol of 2.

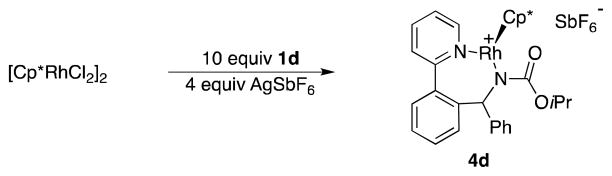

In addition to previously reported transformations using N-Boc and N-tosyl protected imines,2a isopropoxycarbonyl was included as a protecting group to provide a model substrate for our kinetic analysis of the reaction. This was necessary because kinetic analysis employing N-tosyl-imines would provide only limited information due to the reversibility of C–C bond formation, and an unfavorable equilibrium between substrate and product.2a On the other hand, while the reaction with N-Boc protected imine 3b is not reversible,2a competitive deprotection of the Boc group under the slightly acidic reaction conditions complicates kinetic analysis. The N-isopropoxycarbonyl-imine functionality in 3d is comparably electrophlic to the N-Boc imine and gives similar yields (82% vs. 81%), but is stable to acids. Importantly, no back reaction to 2 or 3d was observed when N-isopropoxycarbonyl amine 1d was treated with 20 mol % of Rh(III) catalyst (Scheme 2). However, quantitative formation (with respect to rhodium) of complex 4d was observed.

Scheme 2.

Irreversibility of C–C Bond Formation

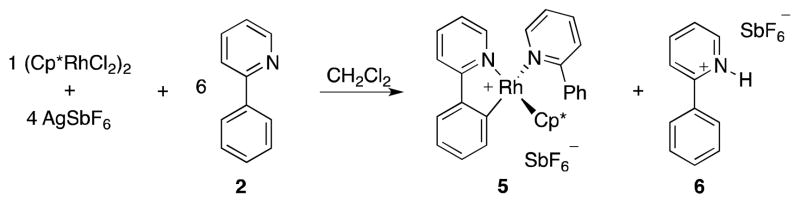

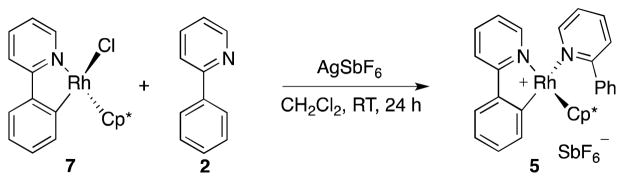

Our first objective was to gain insight regarding the nature of the catalytic species, and which reagents are involved in its formation. To address this issue, we heated 2, [Cp*RhCl2]2, and AgSbF6 (6:1:4) in CH2Cl2 to 75 °C for 16 h (Scheme 3). We observed formation of a mixture of cyclometallated rhodium- complex 5, pyridinium salt 6 and AgCl.8 The mixture exhibited broadened resonances in the 1H NMR spectra that are indicative of a ligand exchange with 2. From a concentrated solution of 5 and 6 in CHCl3 single crystals of 5 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis could be obtained (Figure 1). Cp*-complex 5 has a three legged piano stool configuration with one 2-phenylpyridine acting as a bidentate κC-,κN-ligand, and one 2-phenylpyridine saturating the free valence site of the rhodium center as a monodentate κN-ligand.

Scheme 3.

Cyclometallation

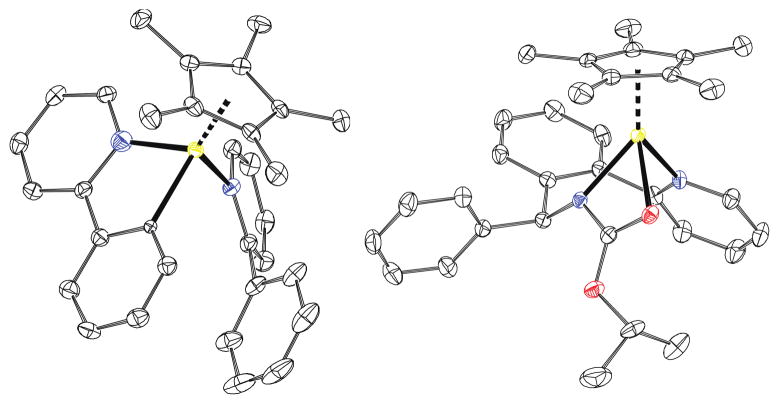

Figure 1.

Thermal ellipsoid plot of 5 (left) and 4d (right) depicted at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and SbF6 anions are omitted for clarity.9,10

Cyclometallation of 2 could also be performed at room temperature. Presumably, during cyclometallation of [Cp*RhCl2]2 with 2, one molecule of 2 acts as a base in a concerted metallation-deprotonation type mechanism (CMD),11 similar to the acetate assisted mechanism described by Jones et al.7a

Quantitative separation of 5 from 6 proved difficult and only moderate yields of 5 could be obtained. Therefore, we sought an alternative preparative route to 5. Complex 7, readily available by cyclometallation of [Cp*RhCl2]2 with 2 in the presence of NaOAc,12 served as a convenient precursor, and afforded 5 in 99% yield by chloride abstraction with AgSbF6 in the presence of excess 2 (Scheme 4).13 In solution (CH2Cl2), decomposition of 5 began to occur within a few hours at room temperature, whereas no decomposition was observed in a solution containing excess 2.

Scheme 4.

Alternative Access to resting state 5

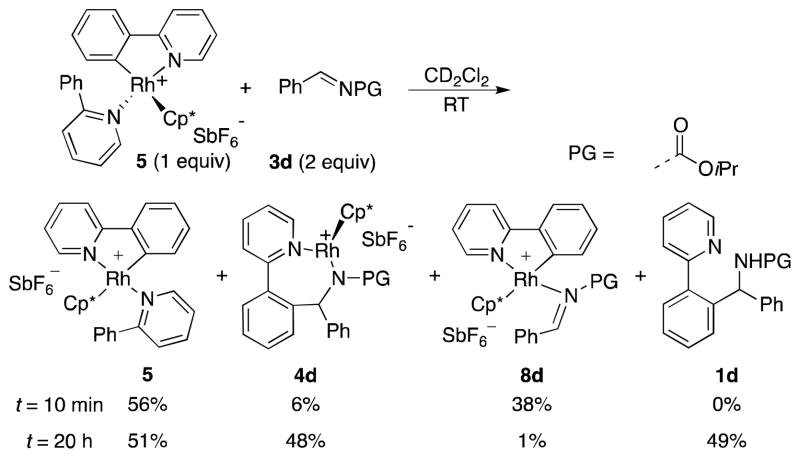

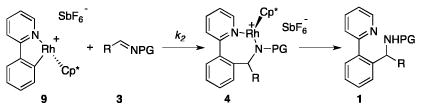

To investigate the C–C bond formation step of imine arylation, we monitored the reaction of a 1:2 mixture of 5 and imine 3d in CD2Cl2 at room temperature (Scheme 5). Initial formation of imine adduct complex 8d was observed, and this material was consumed almost completely within 20 h in favor of 4d with concomitant formation of amine 1d.14

Scheme 5.

Resting states during imine arylation

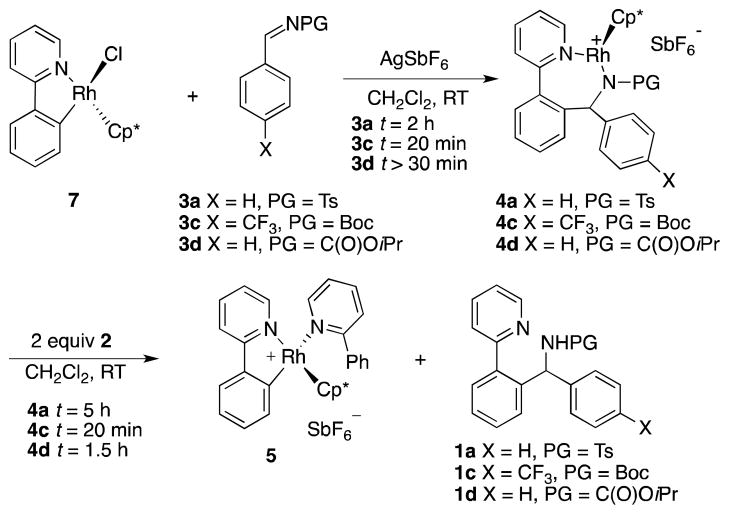

We next developed an independent synthesis of complexes 4a, c, and d by adding a solution of the respective imines in CH2Cl2 to a mixture of AgSbF6 and 7 at room temperature (Scheme 6).15 After crystallization complexes 4a, c, and d were obtained in 73%, 81%, and 66% yields, respectively. These materials were stable in CD2Cl2 for several days.

Scheme 6.

C–C Bond Formation and Propagation

We were able to obtain single crystals of 4a, c, and d suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis by slow diffusion of n-pentane into a saturated solution of the respective compounds in CH2Cl2 (Figure 1).16 The solid-state structure of Cp*-complex 4d depicted a three-legged piano stool configuration with the deprotonated amine 1d acting as a tridentate ligand, which coordinates to the rhodium center via its two nitrogen atoms and the carbonyl-oxygen of the protecting group.

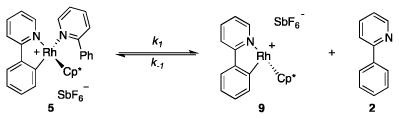

To gain further insight into the catalyst propagation step, complexes 4 were next treated with 2 equiv of the unsubstituted heterocycle starting material 2. For 4a, the C–H activation complex 5 was quantitatively generated within 5 h with concomitant release of the amine product 1a (Scheme 6). Similarly, 4c reacted to give complex 5 within 30 min and 4d within 1.5 h.

From these stoichiometric transformations (Scheme 5 and 6) we conclude that AgSbF6 and pyridinium salt 6 play a non-essential role during imine-insertion into the Rh–C bond and during amine release/catalyst propagation, while the 18 valence electron (VE) complexes 5 and 4a, c, and d represent resting states of the reaction whose relative amounts depend on the respective amounts of the substrates 2, 3, and product 1.

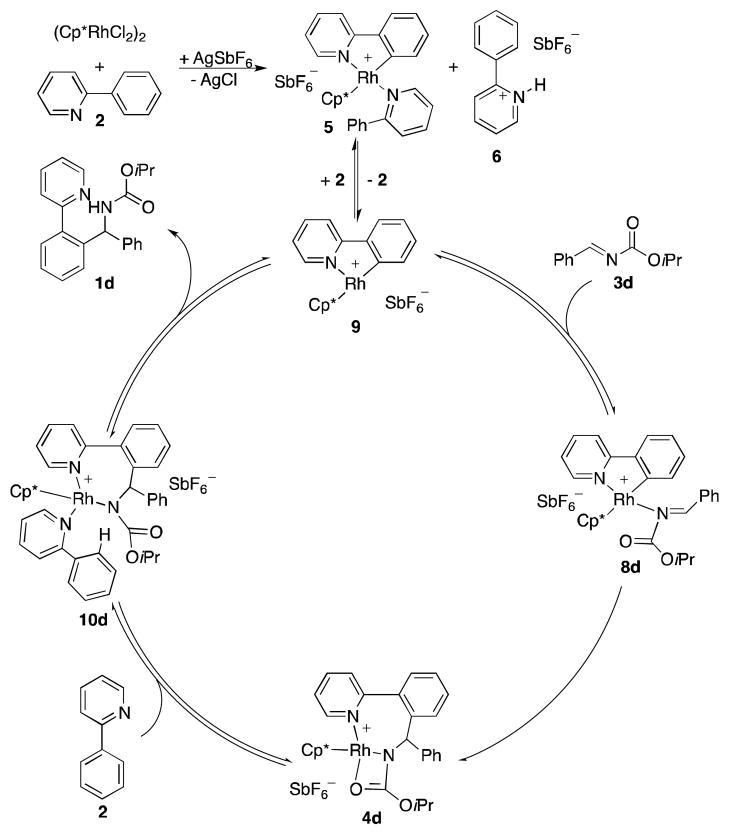

We propose a catalytic cycle for the Rh(III)-catalyzed arylation of imines (Scheme 7) in which the pre-catalyst mixture of AgSbF6 and [Cp*RhCl2]2 rapidly forms resting state 5 and pyridinium salt 6 with 2 acting as a base during CMD. To enter the catalytic cycle, 18 VE-complex 5 needs to lose ligand 2 yielding 16 VE-complex 9. Addition of imine 3d leads to complex 8d, which is rapidly transformed to 4d by insertion of the C–N double bond into the Rh–C bond. The catalytic cycle proceeds by coordination of 2 yielding intermediate 10d. Presumably, the amide nitrogen ligand in 10d acts as a base during CMD, releasing amine 1d with simultaneous cyclometallation of 2 regenerating catalyst 9.

Scheme 7.

Proposed Mechanistic Cycle

However, alternate mechanisms involving co-catalysts such as pyridinium salt 6 or AgSbF6 are also possible. To determine the effects of such additives, we decided to conduct a kinetic analysis of the reaction (1H NMR monitoring) employing imine 3d as a model substrate (vide supra). To simplify the kinetic analysis a six-fold excess of 2 with respect to 3d was used to suppress resting state 4d in favor of 5.17 Lastly, we switched from CH2Cl2 to 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) to eliminate complications that might result from monitoring the reaction above the reaction solution’s boiling point.

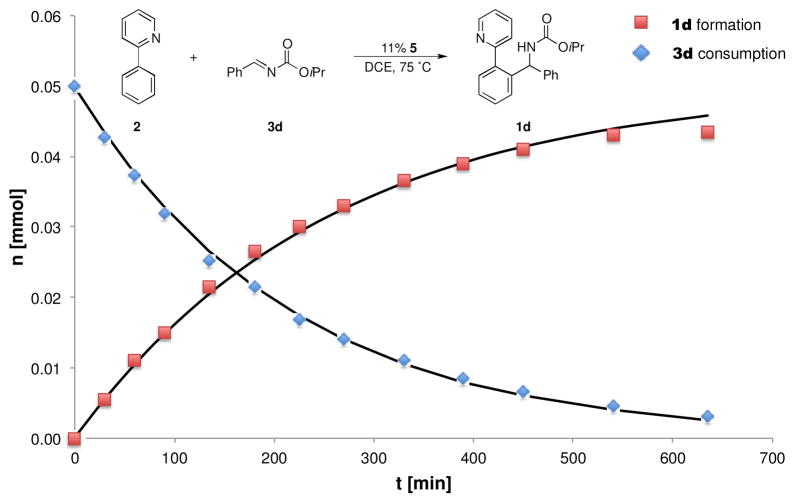

Figure 2 depicts consumption of 3d with formation of 1d over time using 11 mol % of 5 as a catalyst. The reaction followed first order kinetics with k = 0.24 h−1 (Table 2, entry 1) for 1d formation and a slightly higher rate constant for 3d consumption of k = 0.28 h−1. In subsequent runs of the reaction, variable amounts of 6 were added. The reaction remained first order in all cases. While 20 mol % of 6 increased the reaction rate by a factor of 1.48 (Table 2, entries 2 – 4), addition of 40 mol % of 6 resulted in only in a very modest effect (Table 2, entry 5). Similarly, AgSbF6 also resulted in only a small increase in the rate (Table 2, entry 6). These modest effects on the reaction rate could either result from direct involvement of 6 or AgSbF6 or be promoted by a change in the polarity of the medium.

Figure 2.

Monitoring (1H NMR) of imine (3d) arylation with 2. Conditions: 0.050 mmol of 3d, 0.300 mmol of 2, 0.050 mmol of hexamethylbenzene (C6Me6), 5.6 μmol of 5, 0.70 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), T = 75 °C. Black line (simulated): [3d]t = [3d]t=0 - e−k·t (k = 0.24 h−1) and [1d]t = [3d]t=0 - (1 - e−k·t) (k = 0.28 h−1).

Table 2.

Reaction ratesa

| entry | [Rh] | 6 [mol%] | AgSbF6 [mol%] | kb [h−1] | krel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5c | 0 | - | 0.24 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 5c | 5 | - | 0.27 | 1.13 |

| 3 | 5c | 10 | - | 0.31 | 1.30 |

| 4 | 5c | 20 | - | 0.35 | 1.48 |

| 5 | 5c | 40 | - | 0.25 | 1.05 |

| 6 | 5c | - | 12 | 0.32 | 1.36 |

| 7 | [Cp*RhCl2]2d | - | 23 | 0.28 | 1.20 |

0.05 mmol of 1d, 3.00 mmol of 2, 0.05 mmol of C6Me6, DCE (total volume 0.70 mL), T = 75 °C.

Determined from logarithmic plot over first 6.5 h (75 – 80% conversion).

5.6 μmol.

2.8 μmol.

When we employed a mixture of [Cp*RhCl2]2 and AgSbF6 (1:4) as a catalyst, the reaction maintained first order kinetics. The reaction rate was determined as k = 0.28 h−1 (Table 2, entry 7), which is very similar to the rate constant observed when 5 and 6 were employed in a 1:1 ratio (k = 0.31 h−1, Table 2, entry 3). We consider this observation as evidence that the pre-catalyst mixture of [Cp*RhCl2]2/AgSbF6 forms 5 and 6 as the catalytically active compounds in the reaction.

To determine the rate law we monitored the reaction with variable amounts of resting state 5 and 2-phenylpyridine (2). The reaction was found to be first order in 518 and inverse first order in 2.19

We propose the mechanism shown in eqs 1 and 2 for this overall transformation. Complex 9 is produced in a fast equilibrium from resting state 5 by dissociation of 2 (eq 1). We formulate the steady state concentration of 9 by the sum of its formation from 5 and consumption by reaction with 3d and 2 (eq 3).20 Solving for [9] gives eq 5. We assume that k−1[2] ≫ k2[3d], because stoichiometric transformations (Scheme 6) indicated that k−1>k2,21 and at least a four fold excess of 2 with regard to 3d was used during kinetics. Insertion of eq 5 into eq 3 yields eq 6 as an expression for our rate law. With kobs = 0.060 h−1, eq 6 produces excellent fits for the observed amine formations in the catalytic runs with 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 equiv of 2-phenylpyridine (2).19

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

In conclusion, we have provided a detailed study of the mechanism of Rh(III)-catalyzed imine arylation with 2-phenylpyridine (2). The precatalyst mixture of [Cp*RhCl2]2 and AgSbF6 leads to cyclometallation of 2 to yield resting state 5 and pyridinium salt 6 via a CMD mechanism. After formation of 5, both AgSbF6 and 6 are non-essential for catalysis. While the basicity of 2 plays an important role during catalyst initiation (cyclometallation), it also accounts for substrate inhibition by stabilizing resting state 5. Insertion of imines into the Rh–C bond affords amide complex 4. Product release from intermediate 4 occurs simultaneously with cyclometallation with 2, regenerating 5, during which the deprotonated amine-ligand serves as a base during CMD. Thus, only catalyst initiation benefits from the basicity of 2, while it inhibits catalyst turnover. In consequence, possible future directions for imine arylation could include an alternate catalyst initiation, potentially permitting a broader scope of the arylating substrate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH Grant GM069559 (to J.A.E.) and by the Director, Office of Energy Research, Office of Basic Energy Science, Chemical Sciences Division, U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 (to R.G.B.). M.E.T. thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for a research fellowship (Ta 733/1-1 and Ta 733/1-2). We thank Dr. John J. Curley and Dr. Antonio G. DiPasquale for help in X-ray analysis. A loan of a heating circulator for kinetic experiments by Dr. Kenneth B. Wiberg is greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental details for syntheses, kinetic experiments and NMR spectra for all compounds described, X-ray crystallographic data for 4a, 4c, 4d, and 5. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Colby DA, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. Chem Rev. 2010;110:624. doi: 10.1021/cr900005n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Satoh T, Miura M. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:11212. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen X, Engle KM, Wang D-H, Yu J-Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wencel-Delord J, Dröge T, Liu F, Glorius F. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4740. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Karimi B, Behzadnia H, Elhamifar D, Akhavan P, Esfahani F, Zamani A. Synthesis. 2010:1399. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Tsai AS, Tauchert ME, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1248. doi: 10.1021/ja109562x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Y, Li B-J, Wang W-H, Huang W-P, Zhang X-S, Chen K, Shi Z-J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:2115. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Yang L, Correia CA, Li C-J. Adv Synth & Catal. 2011;353:1269. [Google Scholar]; (b) Park J, Park E, Kim A, Lee Y, Chi K-W, Kwak JH, Jung YH, Kim IS. Org Lett. 2011;13:4390. doi: 10.1021/ol201729w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hesp KD, Bergman RG, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11430. doi: 10.1021/ja203495c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu C, Xie W, Falck JR. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:12591. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Y, Hyster TK, Rovis T. Chem Commun. 2011;47:12074. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15843k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Li L, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2009;28:3492. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stuart DR, Alsabeh P, Kuhn K, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:18326. doi: 10.1021/ja1082624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li L, Jiao Y, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2010;29:3404. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hyster TK, Rovis T. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1606. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00235J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.In a control experiment employing 6 instead of [Cp*RhCl2]2 as a catalyst for imine arylation no catalytic activity was observed, excluding the possibility of a rhodium-free, acid-catalyzed mechanism (1.0 equiv of 1c, 1.5 equiv of 2, 0.4 equiv of 6, CH2Cl2, 16 h at 75 °C).

- 9.Crystal data for 5: C32H32F6N2RhSb, Mr = 783.26, orthorhombic space group P212121, T = 100(2) K, a = 13.046(3) Å, b = 13.991(3) Å, c = 16.446(3) Å, α = β = γ = 90°, V = 3002.0(10) Å3, μ = 1.512 mm−1 Z = 4, 153584/9171 reflections collected/unique, R1 = 0.02, wR2 = 0.05, GOF = 1.080.

- 10.Crystal data for 4d: C33H38F6N2O2RhSb, Mr = 904.21, mono-clinic space group P21/c, T = 123(2) K, a = 18.8446(9) Å, b = 9.9469(4) Å, c = 19.9152(9) Å, α = 90°, β = 100.0660(10)°, γ = 90°, V = 3675.5(3) Å3, Z = 4, μ = 1.391 mm−1, 33709/6747 reflections collected/unique, R1 = 0.02, wR2 = 0.06, GOF = 1.059.

- 11.This mechanism is frequently also described as electrophilic C–H bond activation. However, more recently, the term CMD has become more dominant and will be used in this manuscript. For a recent review see: Lapointe D, Fagnou K. Chem Lett. 2010;39:1118.

- 12.(a) Hijazi A, Djukic JP, Allouche L, de Cian A, Pfeffer M, Le Goff XF, Ricard L. Organometallics. 2007;26:4180. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li L, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12414. doi: 10.1021/ja802415h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Both 5 and a mixture of 7/AgSbF6 (1:1) displayed catalytic activity, but no imine (3c) arylation was observed when 7 was employed alone as the catalyst.

- 14.See SI for detailed information about additional experiments employing stoichiometric amounts of imines 3c and 3d, mixtures of 3 and 2, as well as the dependence of the 2 : 4a ratio on 2, 1a, and 3a concentration.

- 15.In analogy to the transformation outlined in Scheme 6, in the synthesis of 4d intermediate formation of 8d was observed by NMR.

- 16.Only 4d is shown. The structures of 4a and c are very similar and may be found in the SI.

- 17.Complexes 4d (minor) and 5 (major) were observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy during a catalytic transformation employing a 1 : 1 ratio of 2 and 3d. When the reaction was run with a 4 : 1 ratio of 2 and 3d as substrates, only 5 could be detected by 1H NMR. See also ref. 14.

- 18.7.5, 10.0, 15.0, and 20.6 mol% of 5 relative to 3d, respectively, 0.050 mmol of 3d, 0.300 mmol of 2, 0.050 mmol of C6Me6 as internal standard, DCE (total volume: 0.70 mL), T = 75.0 °C (see SI).

- 19.3.98, 4.94, 6.00, 7.05, 8.06 equiv of 2 relative to 3d, respectively, 0.050 mmol of 3d, 0.050 mmol of C6Me6 as internal standard, DCE (total volume: 0.70 mL), T = 75.0 °C (see SI).

- 20.Since the formation of 4d is irreversible, subsequent steps leading to 1d can be omitted in the rate law analysis.

- 21.A solution of complex 5 in CD2Cl2 does not display any traces of 9 detectable by 1H NMR spectroscopy at room temperature. Reaction of 3d with 9 yields 8d at room temperature, which is slowly converted into 4d.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.