Abstract

Fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1)–expressing cells accumulate in damaged kidneys, but whether urinary FSP1 could serve as a biomarker of active renal injury is unknown. We measured urinary FSP1 in 147 patients with various types of glomerular disease using ELISA. Patients with crescentic GN, with or without antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody–associated GN, exhibited elevated levels of urinary FSP1. This assay had a sensitivity of 91.7% and a specificity of 90.2% for crescentic GN in this sample of patients. Moreover, we found that urinary FSP1 became undetectable after successful treatment, suggesting the possible use of FSP1 levels to monitor disease activity over time. Urinary FSP1 levels correlated positively with the number of FSP1-positive glomerular cells, predominantly podocytes and cellular crescents, the likely source of urinary FSP1. Even in patients without crescent formation, patients with high levels of urinary FSP1 had large numbers of FSP1-positive podocytes. Taken together, these data suggest the potential use of urinary FSP1 to screen for active and ongoing glomerular damage, such as the formation of cellular crescents.

Crescentic GN is a particularly aggressive type of kidney disease in which glomerular injury causes rapidly progressive GN.1,2 Strong immunosuppressive therapy should be administered as early as possible in order to prevent irreversible kidney scarring.3 The widespread use of assays for antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) has facilitated the clinical diagnosis of pauci-immune crescentic GN.4,5 However, there have been few studies of biomarkers that could potentially serve to identify all forms of crescentic GN.

Fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1) is one of the S100 calcium-binding proteins, a family of secreted and cytosolic proteins involved in a variety of biologic processes.6–8 A large number of FSP1-expressing cells (FSP1+ cells) accumulate in kidneys showing active renal damage.9–11 In this study, we hypothesize that FSP1 secreted from FSP1+ cells in the kidney should be detectable in urine samples. To test that idea and to clarify the significance of urinary FSP1 as a biomarker of active glomerular damage, we established two monoclonal antibodies for human FSP1 and developed a method for measuring urinary FSP1 levels using a sandwich-type ELISA. We then used that assay to assess urinary FSP1 excretion in cases of human GN.

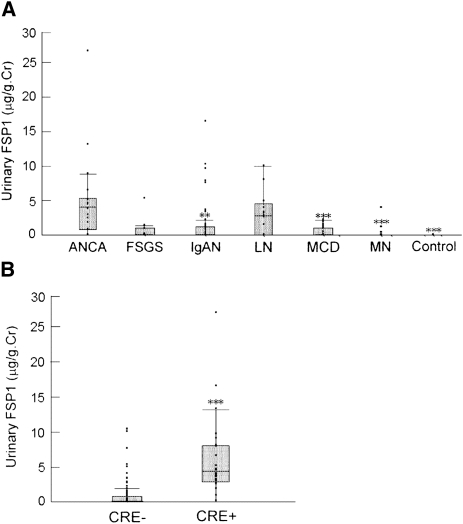

Urinary FSP1 levels were measured in 147 patients with various types of glomerular disease (Figure 1A). In patients with ANCA-associated GN, urinary FSP1 levels were significantly higher (median, 3.71 μg/g of creatinine [first quartile, third quartile, 0.71, 5.07 μg/g of creatinine]) than in patients with IgA nephropathy (0.0 μg/g of creatinine [0.0, 0.98 μg/g of creatinine]; P<0.001), minimal-change nephrotic syndrome (0.0 μg/g of creatinine [0.0, 0.87 μg/g of creatinine]; P<0.0001), or membranous nephropathy (0.0 μg/g of creatinine [0.0, 0.0 μg/g of creatinine]; P<0.0001). Urinary FSP1 was not detectable in any of the healthy volunteers. In 56 patients with IgA nephropathy, the percentages of glomeruli showing cellular crescents, fibrocellular crescents, global sclerosis, and segmental sclerosis correlated positively with urinary FSP1 levels (Supplemental Table 1). A high level of urinary FSP1 (5.21 μg/g of creatinine) was also observed in one patient with FSGS showing a cellular variant.

Figure 1.

Elevation of urinary FSP1 in patients with ANCA nephritis and crescent formation. (A) Urinary FSP1 levels were measured in patients with ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis (ANCA), FSGS, IgA nephropathy (IgAN), lupus nephritis (LN), minimal-change nephrotic syndrome (MCD), or membranous nephropathy (MN). Urinary FSP1 levels were elevated in patients with ANCA and were undetectable in healthy volunteers (control). **P<0.001 and ***P<0.0001 versus ANCA. Cr, creatinine. (B) Urinary FSP1 levels were significantly higher in patients with 20% crescent formation (CRE+) than those without it (CRE−).

Urinary FSP1 levels did not differ between patients with primarily cellular crescents or fibrocellular crescents, but urinary FSP1 was undetectable in five patients with fibrous crescents (Supplemental Figure 1). In five patients with IgA nephropathy and three patients with lupus nephritis, cellular or fibrocellular crescents were identified in more than 20% of glomeruli (20% crescent formation). Given that urinary FSP1 levels were markedly elevated in these eight patients (5.93 μg/g of creatinine [3.45, 9.34 μg/g of creatinine), we divided the 147 study participants into two groups (with or without 20% crescent formation) and compared urinary FSP1 between these two groups. We found that urinary FSP1 levels were significantly higher in patients with 20% crescent formation than in those without it (4.48 μg/g of creatinine [2.91, 8.03 μg/g of creatinine] versus 0 μg/g of creatinine [0, 0.72 μg/g of creatinine]; P<0.0001) (Figure 1B).

To assess the diagnostic value of urinary FSP1 as a novel marker for crescent formation, we used receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis to determine a cut-off level for urinary FSP1 (Supplemental Figure 2) and made a 2×2 table. At FSP1 levels greater than 1.75 μg/g of creatinine, the assay had 90.2% specificity and 91.7% sensitivity for diagnosis in patients with 20% crescent formation. The positive and negative predictive values were 64.7% and 98.2%, respectively. We can also specifically select patients with 15% crescent formation by changing the FSP1 cut-off levels to greater than 5.0 μg/g of creatinine because both the specificity and the positive predictive value increased (to 98.3% and 86.7%, respectively), although the sensitivity decreased (to 43.3%).

The proteinuria level is a classic and valuable prognostic marker of CKD. However, proteinuria is not helpful for determining whether glomerular damage is ongoing. There have been a few studies of potential biomarkers for crescentic GN. Kanno and colleagues12 showed that levels of urinary sediment podocalyxin are elevated in children with cellular crescents. Levels of urinary macrophage migration inhibitory factor and matrix metalloproteinase activity are reportedly higher in patients with crescentic GN and ANCA-associated GN than in healthy controls,13,14 but the levels are not significantly higher than in patients with other glomerular diseases. By contrast, urinary FSP1 levels strongly correlated with the percentage of glomeruli showing cellular or fibrocellular crescent formation in patients with crescent formation, irrespective of the specific glomerular disease (Supplemental Figure 3). In addition, we confirmed a superiority of urinary FSP1 over other existing screening tests (C-reactive protein and serum creatinine) in diagnosing ANCA-negative crescentic GN (Supplemental Figure 4). These results suggest that urinary FSP1 may be useful for the diagnosis and management of all forms of crescentic GN.

We measured urinary FSP1 after therapy in six patients treated for ANCA-associated GN, three treated for lupus nephritis, and three treated for IgA nephropathy. All 12 patients had shown high levels of urinary FSP1 (FSP1 > 3.50 μg/g of creatinine) before therapy. However, urinary FSP1 was undetectable in 11 of those patients after successful treatment, which was judged according to the reduction of urinary protein levels and improvement of renal function. The 12th patient had lupus nephritis and continued to show proteinuria in the nephrotic range, a high titer of anti–double-stranded DNA, and severe hypocomplementemia. Moreover, urinary FSP1 levels continued to be high in this patient. This result suggests that FSP1 levels can be used as a follow-up marker.

We next measured FSP1 levels in serum samples obtained from 88 patients (14 patients with ANCA-associated GN, 38 with IgA nephropathy, 19 with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome, and 17 with membranous nephropathy) on the same day that urine samples were collected. We found that serum FSP1 levels were not elevated in the patients with ANCA-associated GN (Supplemental Figure 5), and there was no correlation between serum and urinary FSP1 levels (data not shown).

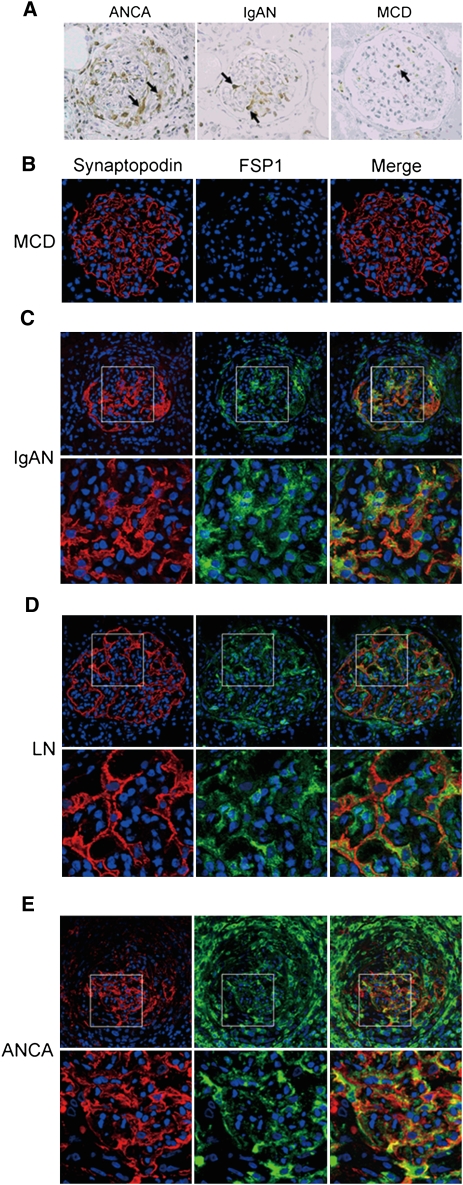

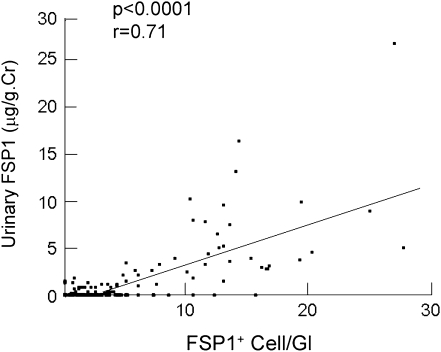

To investigate the origin of the urinary FSP1, we carried out an immunohistochemical analysis using an anti-FSP1 antibody. Figure 2A shows the three typical staining patterns. FSP1+ cells accumulated in cellular crescents in patients with ANCA-associated GN. FSP1+ podocytes were observed in patients with IgA nephropathy. By contrast, FSP1+ cell numbers in glomeruli were significantly lower in patients with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome (Figure 2, A and B). Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, C–E, dual immunofluorescence confirmed the presence of FSP1+ podocytes in patients whose urinary FSP1 was higher than 1.75 μg/g of creatinine, irrespective of crescent formation. Indeed, FSP1+ cell numbers and glomerular profile strongly correlated with urinary FSP1 levels (Figure 3). Taken together, these data suggest that FSP1+ glomerular cells are the main source of urinary FSP1. In patients with no crescent formation, urinary FSP1 levels were significantly higher in those with more than six FSP1+ podocytes than in those with fewer (Supplemental Figure 6). This finding suggests that both FSP1+ podocytes and crescent-forming cells may contribute to urinary FSP1.

Figure 2.

Increased expression of FSP1 in podocytes and cellular crescents. (A) Representative photomicrograph illustrating FSP1 expression within glomeruli. Large numbers of FSP1+ cells accumulate in cellular crescents in patients with ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis (ANCA). FSP1+ podocytes are localized on the outside of the glomerular basement membrane in a patient with IgA nephropathy (IgAN). FSP1+ cells are rarely observed in a patient with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome (MCD). Arrows indicate FSP1+ cells. (B–E) Representative immunofluorescence in renal biopsy specimens from patients with the following: (B) minimal-change nephrotic syndrome, (C) IgA nephropathy, (D) lupus nephritis (LN), and (E) ANCA. Cells expressing FSP1 (green) are clearly present within glomeruli from patients with IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, and ANCA. Merged images show co-localization of synaptopodin (red) and FSP1. Original magnification in upper panels, ×200. Lower panels are the high-power images of the boxed areas of the upper panels.

Figure 3.

Urinary FSP1 levels are positively correlated with numbers of FSP1+ cells/glomerular profile. Cr, creatinine; Gl, glomerular profile.

Identifying the origin of urinary FSP1 is difficult because elevated urinary FSP1 excretion could reflect enhanced intrarenal production, increased filtration, abnormal tubular reabsorption, or secretion from urinary cells that have detached from the renal structure. Serum FSP1 levels were not elevated in patients with crescent formation and did not correlate with urinary FSP1. Thus, urinary FSP1 excretion does not reflect increased systemic inflammation. Potential sites of FSP1 secretion into the urinary space are glomerular cells and tubular epithelial cells. The numbers of FSP1+ tubular epithelial cells are much lower (<1.0/high-power field) than those of FSP1+ glomerular cells, suggesting that glomerular cells are the main source of urinary FSP1. It was recently reported that FSP1 is secreted as a microparticle-like structure15 and that podocytes are able to secrete proteins as microparticles through cellular shedding.16 We further suggest that FSP1 secreted through microparticle shedding is not reabsorbed by tubular epithelial cells and is detected in urine samples. In addition, we previously demonstrated that more than 80% of detached podocytes express FSP1 in diabetic nephropathy, which suggests that some urinary FSP1 may be derived from detached podocytes or crescent cells. Because FSP1 was also produced by interstitial fibroblasts, the extent of renal fibrosis may have some effect on urinary FSP1 excretion. Urinary FSP1 levels weakly but significantly correlated with the extent of renal fibrosis evaluated according to the collagen type 1–positive area (Supplemental Figure 7). However, after adjustment for the number of FSP1+ cells in the glomeruli, there was no association between the extent of renal fibrosis and urinary FSP1 levels.

Urinary FSP1 levels were significantly elevated in patients with high numbers of FSP1+ podocytes, as well as in patients with 20% crescent formation. This finding suggests that the elevated urinary FSP1 levels are due in part to podocytes undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition and detaching from the glomerular basement membrane.17–19 We previously reported that the appearance of FSP1 in podocytes of diabetic patients is associated with more severe clinical and pathologic findings of diabetic nephropathy, perhaps because of induction of podocyte detachment through an epithelial-mesenchymal transition–like phenomenon.11 Urinary FSP1 may therefore be a novel risk factor for glomerular damage due to podocyte detachment, even in patients without crescent formation.

In summary, we established a novel ELISA system for measuring urinary FSP1, which appears to be a potentially useful biomarker for evaluating active glomerular damage, including crescent formation and the presence of FSP1+ podocytes. Using this new biomarker clinically, we may be able to better identify patients who require hospitalization and urgent immunosuppressive therapy.

Concise Methods

Production of Antihuman FSP1 Monoclonal Antibodies

An FSP1 expression vector was generated by cloning the full-length human FSP1 gene into pET-49b(+) vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) carrying the GST-Tag and His-Tag sequences. BL21DE3-competent cells were then transformed using the FSP1 expression vector, after which protein expression was induced using isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). The expressed fusion protein was purified by column chromatography using HisTrap HP columns (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan), after which the GST-Tag and His-Tag were cleaved using human rhinovirus 3C protease (Novagen) to obtain the pure recombinant human FSP1 (rFSP1). The rFSP1 (50 μg/250 μl) was then emulsified in an equal volume of CFA (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) and used as an immunogen.

To raise monoclonal antibodies, BALB/c mice (female, 7 weeks old) (Japan Clea, Tokyo, Japan) were intraperitoneally injected with the immunogen, and similar immunizations were carried out 2, 4, and 6 weeks later. One week after the fourth immunization, a booster injection of the immunogen without adjuvant was administered into the tail vein. Three days after the booster injection, the spleens were removed from the mice and dissociated by passage through 100-mesh steel gauze; the dissociated splenocytes (2×108) were then fused with an equal number of myeloma cells in the presence of 50% polyethylene glycol 1500 (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). The fused cells were then suspended in selective growth medium supplemented with 5% Briblone (Archport, Dublin, Ireland), distributed into the wells of 96-well culture plates (2×105 hybrid cells/well), and cultured with periodic changes of the medium. The supernatants from wells containing hybridoma colonies were screened for the presence of specific antibodies using a direct ELISA, and the hybridoma cells from positive wells were cloned twice by limiting dilution. Each clone was then expanded in culture, after which the antibody-rich supernatants were concentrated by ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialyzed against PBS, and stored at −80°C.

Supernatants from 484 wells containing hybridoma cells were tested for antibodies. Using a direct ELISA and native PAGE, five were found to have preferential binding to rFSP1. From those we selected two clones that bound to rFSP1 with high titers (F1-2 and I11-23). Isotype analysis (Sterotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) revealed that F1-2 was of the IgG2a (κ) subclass, and I11-23 was of the IgG1 (κ) subclass. Through epitope mapping using PepSpots (JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany), we confirmed that these two monoclonal antibodies bind to different epitopes: F1-2 recognizes the N-terminal end of rFSP1, and I11-23 recognizes the EF hand calcium-binding domain. F1-2 was then biotinylated using NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL), after which the efficacy of the surface biotinylation was confirmed using a 2-(4-hydroxyazobenzene) benzoic acid assay (Pierce Chemical).

Development of a Sandwich ELISA

To construct a sandwich ELISA, we coated the bottom of each well of a polyvinyl chloride microtiter plate (Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, MA) with I11-23 (1 μg/50 μl PBS) and then incubated the plate overnight at 37°C. To construct a standard curve, urine samples and rFSP1 (from 1 to 64 ng/ml) were added to each well and incubated overnight at 4°C. After the incubation, the plates were washed five times with washing buffer (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20). The biotinylated antibody (F1-2, 1 μg/100 μl) was then added to each well and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. The plates were again washed five times, after which horseradish peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. After washing, o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (0.2 mg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 0.02% H2O2 was added and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The colorimetric reaction was stopped by addition of 2 M H2SO4 (50 μl/well), and the adsorption at 492 nm was measured with a microplate reader. Urinary concentrations were adjusted for the creatinine concentration and expressed as micrograms per gram of creatinine. The intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.5% and 8.4%, respectively. The detection limit of the test is 1 ng/ml.

Patients and Sample Preparation

One hundred forty-seven patients (68 men and 79 women) with biopsy-proven glomerular disease were enrolled in this study after providing fully informed consent. This study was approved by our institutional review board. Patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis, diabetes mellitus, neoplasia, viral hepatitis, amyloidosis, or other infections were excluded. The participants ranged from 16 to 89 years of age (mean age ± SD, 47.8±20.3 years). Before starting therapy, all patients were referred to the Department of Internal Medicine of Nara Medical University Hospital, and kidney biopsies were performed. Included were 19 patients with ANCA-associated GN, 10 with FSGS, 56 with IgA nephropathy, 13 with lupus nephritis, 29 with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome, and 20 with membranous nephropathy. Freshly voided urine samples were collected from each patient in the morning on the day renal biopsy was performed. Urine samples showing a urinary tract infection were excluded because of the possibility of nonspecific positivity. Macroscopic hematuria was also excluded because of the possibility of contamination by serum. Twenty-three age-matched healthy volunteers also provided urine samples. All samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1500 g to remove any debris and were stored at −80°C before use.

Immunohistochemistry

Renal biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 12 hours, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned according to standard procedures. The sections were then deparaffinized and incubated with proteinase K (0.4 mg/ml) for 5 minutes at room temperature for FSP1 staining or were incubated with 0.1% trypsin for 90 minutes at 37°C for collagen type 1 staining. The endogenous peroxidase activity was then blocked with 0.03% hydrogen peroxide, and nonspecific protein binding was blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS containing 2% BSA. The blocked sections were incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with a primary rabbit polyclonal antihuman FSP1 antibody (1:5000 dilution) or with a primary rabbit polyclonal antihuman collagen type 1 antibody (1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), after which the antibody was detected using a DAKO Envision+System peroxidase (diaminobenzidine) kit (DakoCytomation Inc., Carpinteria, CA). The sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin. The specificity of FSP1 staining was confirmed using control rabbit serum and by absorption of the anti-FSP1 antibody using an excess of rFSP1 protein. The area positively stained for collagen type 1 was calculated using AnalySIS image analysis software (Soft Imaging System, Munster, Germany).

Frozen sections of renal biopsy specimens were also stained for dual immunofluorescence microscopy. After the sections were fixed on glass slides in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 4°C, they were incubated for 60 minutes, first with goat polyclonal antihuman synaptopodin (P-19) antibody (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and then with rabbit polyclonal antihuman FSP1 antibody (1:2000 dilution).13 The sections were then washed three times with PBS and incubated for 30 minutes with DyLight 488-conjugated donkey antirabbit secondary antibody (1:800 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA) and a Cy3-conjugated donkey antigoat secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc.). Finally, the sections were counterstained with 4′6-diamidine-2′- phenylindole dihydrochloride (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) and viewed under a confocal microscope (Fluoview FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analyses

Data were recorded as the median (25th percentile, 75th percentile), and P<0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons between two groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc analysis using the Mann–Whitney test and adjustment of the P value using the Bonferroni method (P<0.002) was used to assess differences in clinical measures among more than three groups. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between urinary FSP1 and FPS1+ cell number and glomerular profile. All analyses were performed using JMP 5.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values were calculated using receiver-operator characteristic curves and 2×2 tables.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Fumika Kunda, Ms. Miyako Sakaida, and Ms. Aya Asano for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Keiichi Imagawa (Shionogi Co.) and Dr. Yoshiko Dohi (Nara Medical University) for helpful discussions.

This work was supported in part by Research Grant 21591036 to M.I. from the Ministry of Education and Science of Japan, a Grant-in-Aid for Diabetic Nephropathy from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2011030229/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Morrin PA, Hinglais N, Nabarra B, Kreis H: Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. A clinical and pathologic study. Am J Med 65: 446–460, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couser WG: Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: Classification, pathogenetic mechanisms, and therapy. Am J Kidney Dis 11: 449–464, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton WK, Sturgill BC: Methylprednisolone therapy for acute crescentic rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Am J Nephrol 9: 368–375, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falk RJ, Jennette JC: ANCA small-vessel vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 314–322, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth AD, Almond MK, Burns A, Ellis P, Gaskin G, Neild GH, Plaisance M, Pusey CD, Jayne DR. Pan-Thames Renal Research Group: Outcome of ANCA-associated renal vasculitis: a 5-year retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 776–784, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, Neilson EG: Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol 130: 393–405, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG: Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donato R: Intracellular and extracellular roles of S100 proteins. Microsc Res Tech 60: 540–551, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishitani Y, Iwano M, Yamaguchi Y, Harada K, Nakatani K, Akai Y, Nishino T, Shiiki H, Kanauchi M, Saito Y, Neilson EG: Fibroblast-specific protein 1 is a specific prognostic marker for renal survival in patients with IgAN. Kidney Int 68: 1078–1085, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada K, Akai Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kimura K, Nishitani Y, Nakatani K, Iwano M, Saito Y: Prediction of corticosteroid responsiveness based on fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1) in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3152–3159, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi Y, Iwano M, Suzuki D, Nakatani K, Kimura K, Harada K, Kubo A, Akai Y, Toyoda M, Kanauchi M, Neilson EG, Saito Y: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a potential explanation for podocyte depletion in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 653–664, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanno K, Kawachi H, Uchida Y, Hara M, Shimizu F, Uchiyama M: Urinary sediment podocalyxin in children with glomerular diseases. Nephron Clin Pract 95: c91–c99, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown FG, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Hill PA, Isbel NM, Dowling J, Metz CM, Atkins RC: Urine macrophage migration inhibitory factor reflects the severity of renal injury in human glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 13[Suppl 1]: S7–S13, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders JS, Huitema MG, Hanemaaijer R, van Goor H, Kallenberg CG, Stegeman CA: Urinary matrix metalloproteinases reflect renal damage in anti-neutrophil cytoplasm autoantibody-associated vasculitis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1927–F1934, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forst B, Hansen MT, Klingelhöfer J, Møller HD, Nielsen GH, Grum-Schwensen B, Ambartsumian N, Lukanidin E, Grigorian M: Metastasis-inducing S100A4 and RANTES cooperate in promoting tumor progression in mice. PLoS ONE 5: e10374, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara M, Yanagihara T, Kihara I, Higashi K, Fujimoto K, Kajita T: Apical cell membranes are shed into urine from injured podocytes: A novel phenomenon of podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 408–416, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Kang YS, Dai C, Kiss LP, Wen X, Liu Y: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a potential pathway leading to podocyte dysfunction and proteinuria. Am J Pathol 172: 299–308, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bariety J, Hill GS, Mandet C, Irinopoulou T, Jacquot C, Meyrier A, Bruneval P: Glomerular epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation in pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1777–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogelmann SU, Nelson WJ, Myers BD, Lemley KV: Urinary excretion of viable podocytes in health and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F40–F48, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]