Abstract

Retrospective studies suggest that chronic allograft nephropathy might progress more rapidly in patients with post-transplant anemia, but whether correction of anemia improves renal outcomes is unknown. An open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial investigated the effect of epoetin-β to normalize hemoglobin values (13.0–15.0 g/dl, n=63) compared with partial correction of anemia (10.5–11.5 g/dl, n=62) on progression of nephropathy in transplant recipients with hemoglobin <11.5 g/dl and an estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) <50 ml/min per 1.73 m2. After 2 years, the mean hemoglobin was 12.9 and 11.3 g/dl in the normalization and partial correction groups, respectively (P<0.001). From baseline to year 2, the eCrCl decreased by a mean 2.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the normalization group compared with 5.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the partial correction group (P=0.03). Furthermore, fewer patients in the normalization group progressed to ESRD (3 versus 13, P<0.01). Cumulative death-censored graft survival was 95% and 80% in the normalization and partial correction groups, respectively (P<0.01). Complete correction was associated with a significant improvement in quality of life at 6 and 12 months. The number of cardiovascular events was low and similar between groups. In conclusion, this prospective study suggests that targeting hemoglobin values ≥13 g/dl reduces progression of chronic allograft nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients.

Anemia is a common complication of kidney transplantation.1,2 After the first post-transplantation year, the prevalence of post-transplant anemia (PTA) varies between 25% and 40%.1–4 The pathogenesis of PTA is multifactorial, with declining renal function, failing erythropoietin synthesis, and use of immunosuppressive drugs all playing major roles.1–4 PTA is associated with chronic fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, cognitive decline, and impairment in quality of life (QoL).5 Observational and retrospective studies have produced conflicting conclusions on the association between hemoglobin (Hb) levels and all-cause mortality in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs).6–8 PTA may contribute to the progression of chronic allograft nephropathy,7,9–11 and a positive correlation has been found between the degree of anemia and renal graft function in this population.1,3,9

In CKD, targeting an Hb level of 13 g/dl or higher using erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) did not slow the decline in GFR and was associated with either an increase in cardiovascular events or no benefit.12–14 Therefore, their use should be considered for CKD patients with Hb levels below 11 g/dl and without intentionally exceeding 13 g/dl.15 How these results apply to the KTR is unknown, and prospective randomized studies are needed to determine the optimal target Hb level in this population.

The use of ESAs before transplantation was associated with reduced postoperative blood transfusion requirements,16 decline in late alloreactivity,17 and decreased frequency of late episodes of rejection.17 We recently showed in a randomized, prospective study that the use of high-dose ESAs in the first month after kidney transplantation in patients at risk for delayed graft function effectively corrected anemia but failed to reduce the need for dialysis in the first weeks after transplantation and improve renal function at 3 months.18

Given the lack of evidence to confirm the benefit of ESAs after 1 year of transplantation, we initiated the Correction of Anemia and Progression of Renal Insufficiency in Transplant patients (CAPRIT) study to test the hypothesis that, in KTR with PTA, the complete correction of anemia with epoetin-β would slow the deterioration of renal allograft function.

RESULTS

Study Population

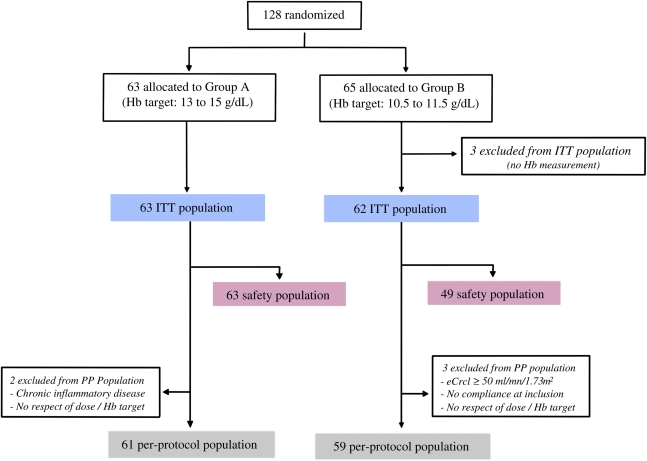

A total of 128 patients were randomized (group A: n=63, group B: n=65). Three patients in group B with no Hb measurement were excluded within the first month. Therefore, the intention to treat population included 125 patients (63 in group A and 62 in group B); of these, 100 (80%) patients completed the study. The per protocol population included 120 patients with no major protocol deviation. The safety population included 63 patients in group A and 49 patients in group B. The trial profile with the study populations is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial profile. Among the 128 patients randomized in the study, 3 were excluded in group B because none had a single Hb determination; the remaining patients represent the ITT population. Very few patients were excluded during follow-up.

The mean patient age was 49±13 years, and 49% were male. The mean time from transplantation was 8±5 years, with a majority being first transplant recipients (87%). The demographic, baseline, and medication characteristics of the two groups were similar (Table 1). Six patients (9.5%) in group A and 18 patients (29.0%) in group B (P<0.05) did not complete the 2-year follow-up assessment because of return to dialysis (group A: n=3, group B, n=13), noncompliance (n=2 in each group), and death (group A: n=1, group B: n=3).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Group A (n=63) | Group B (n=62) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.2 ± 13.1 | 50.4 ± 13.4 | 0.19 |

| Male sex n (%) | 26 (41) | 35 (56) | 0.09 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.5 ± 14.5 | 69.8 ± 15.4 | 0.05 |

| Height (cm) | 165.3 ± 8.7 | 166.6 ± 10 | 0.45 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 4.6 | 25.0 ± 4.4 | 0.06 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 181.4 ± 50.2 | 193.1 ± 56.9 | 0.22 |

| eCrcl: Cockcroft’s formula (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 38.9 ± 10.6 | 37.8 ± 11.0 | 0.55 |

| eGFR: Nankivell’s formula (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 40.0 ± 12.0 | 41.4 ± 13.5 | 0.54 |

| eGFR: MDRD’s formula (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 34.4 ± 10.0 | 33.7 ± 10.8 | 0.70 |

| Cause of chronic kidney disease n (%) | |||

| diabetic nephropathy | 3 (4.8) | 1 (1.6) | 0.61 |

| chronic glomerulonephritis | 18 (28.6) | 29 (46.8) | 0.04 |

| chronic interstitial nephritis | 9 (14.3) | 12 (19.4) | 0.48 |

| polycystic kidney disease | 6 (9.5) | 5 (8.1) | 1.00 |

| other hereditary nephritis | 3 (4.8) | 3 (4.8) | 1.00 |

| others | 18 (28.6) | 11 (17.7) | 0.20 |

| unknown | 6 (9.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.11 |

| Mode of renal replacement therapy | |||

| age at first renal replacement therapy (years) | 35.1 ± 13.8 | 37.8 ± 14.5 | 0.28 |

| hemodialysis n (%) | 50 (82.0) | 52 (89.7) | 1.00 |

| Renal transplantation | |||

| duration of renal transplantation (years) | 8.1 ± 5.0 | 8.3 ± 5.5 | 0.79 |

| age at renal transplantation (years) | 39.2 ± 12.8 | 42.0 ± 13.9 | 0.50 |

| number of previous renal transplantation | |||

| first transplantation n (%) | 56 (88.9%) | 53 (85.5%) | |

| second transplantation n (%) | 6 (9.5%) | 9 (14.5%) | |

| third transplantations n (%) | 1 (1.6%) | — | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| diastolic | 78.8 ± 9.8 | 79.3 ± 9.8 | 0.78 |

| systolic | 136.2 ± 17.3 | 141.6 ± 16.1 | 0.07 |

| Cardiovascular history before inclusion n (%) | 15 (23.8) | 17 (27.4) | 1.00 |

| myocardial infarction | 1 (6.7) | 2 (11.8) | 0.61 |

| coronary revascularization | 1 (6.7) | 4 (23.5) | 0.36 |

| heart failure | 3 (20.0) | 3 (17.6) | 1.00 |

| cardiac valvulopathy | 4 (26.7) | 2 (11.8) | 0.67 |

| cerebral infarction or transient ischemic attack | 2 (13.3) | 1 (5.9) | 1.00 |

| History of neoplasm | 5 (9.3) | 4 (7.3) | 1.00 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 10.4 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 0.13 |

| Platelets (×103/mm3) | 246 ± 65 | 242 ± 64 | 0.72 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | 29.8 ± 10.8 | 31.7 ± 10.3 | 0.33 |

| Serum ferritin (µg/L) | 190 ± 135 | 309 ± 359 | 0.02 |

| Serum albumin level (g/L) | 41.0 ± 4.1 | 40.8 ± 3.9 | 0.78 |

| Protein to creatinine ratio (mg/mmol) | 51.6 ± 94.2 | 34.2 ± 43.6 | 0.67 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 5.0 ± 6.5 | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 0.13 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | |||

| corticosteroids | 45 (71.4) | 40 (64.6) | 0.44 |

| mycophenolate mofetil | 47 (74.6) | 48 (77.4) | 0.83 |

| azathioprine | 7 (11.1) | 7 (11.1) | 1.00 |

| ciclosporine | 45 (71.4) | 48 (77.4) | 0.83 |

| tacrolimus | 17 (27) | 12 (19.4) | 0.39 |

| Immunosuppressive drug association | |||

| 1 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 26 (41.3) | 31 (50) | 0.37 |

| 3 | 36 (57.1) | 31 (50) | 0.47 |

| ARB and/or ACE inhibitor | 44 (69.8) | 44 (71.0) | 1.00 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD or n (%) when appropriate. ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Concomitant Treatment

Immunosuppressive Therapy

A large majority of patients were taking double (46%) or triple (54%) combination immunosuppressive therapy. Mycophenolate mofetil was used in 76% of patients, cyclosporine was used in 74% of patients, and corticosteroids were used in 68% of patients. No significant difference between the two groups regarding immunosuppressive treatment (Table 1), including calcineurin inhibitors (Table 2), was noted at inclusion or during the follow-up.

Table 2.

Calcineurin inhibitors exposure

| Blood Levels of Calcineurin Inhibitors (mg/ml) | Group A | Group B | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclosporine C2a level at month 3 | 541.5 ± 192.3 | 540.2 ± 197.3 | 0.61 |

| Cyclosporine C2a level at month 6 | 574.9 ± 208.5 | 566.9 ± 233.3 | 0.23 |

| Cyclosporine C2a level at month 9 | 504.4 ± 278.1 | 484.9 ± 221.1 | 0.15 |

| Cyclosporine C2a level at month 12 | 601.2 ± 236.4 | 605.4 ± 236.8 | 0.45 |

| Cyclosporine C2a level at month 24 | 505.7 ± 212.2 | 591.9 ± 198.8 | 0.78 |

| Tacrolimus C0b level at month 3 | 7.7 ± 2.7 | 8.2 ± 3.3 | 0.98 |

| Tacrolimus C0b level at month 6 | 7.7 ± 2.7 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 0.90 |

| Tacrolimus C0b level at month 9 | 7.2 ± 2.5 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 0.45 |

| Tacrolimus C0b level at month 12 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 0.38 |

| Tacrolimus C0b level at month 24 | 6.7 ± 3.7 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0.35 |

Using 2-hour postdosing levels.

Using trough levels.

Antihypertensive Medication

Forty-four patients (69.8%) in group A and 44 patients (71.0%) in group B (Table 1) were treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. No difference between groups regarding antihypertensive medication was observed during the study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of antihypertensive medication during the follow-up

| Antihypertensive Medication | Group A (%) | Group B (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 6 | 77.0 | 63.9 | 0.21 |

| Month 12 | 73.3 | 70.7 | 0.42 |

| Month 18 | 70.9 | 67.9 | 0.50 |

| Month 24 | 69.1 | 69.6 | 0.94 |

Anemia Management

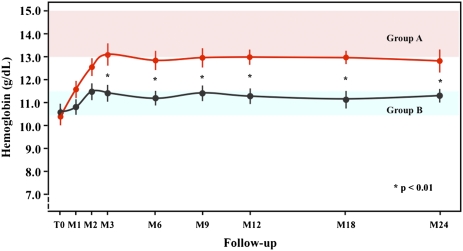

At baseline, the mean Hb level was 10.5±0.8 g/dl in both groups (Table 1). At the end of the correction phase, the mean Hb level was 13.1±1.7 g/dl in group A and 11.4±1.0 g/dl in group B (P=0.01) and remained significantly higher in group A compared with group B at each visit (Figure 2). During the study, patients in group A were more likely to be taking epoetin-β than those patients in group B. At the end of the study, 89.1% of patients in group A and 60.9% in group B were treated with epoetin-β, mainly one time per week (P<0.05). The mean weekly dose was significantly higher in group A than group B at each visit (Table 4). One patient (1.6%) in group A and five patients (8.1%) in group B received a total of 2 and 10 units of packed red cells (P<0.05), respectively.

Figure 2.

Changes during the 24 months of follow-up in mean Hb levels. Red circles and line are for patients in group A, and black circles and line are for patients randomized to group B. The difference between the two groups was significant after the 3-month phase of correction.

Table 4.

Weekly doses of epoetin-β during the study

| Epoetin (IU/wk) | Group A (n=63) | Group B(n=62) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 3 | 6083 ± 3620 | 3488 ± 2117 | <0.001 |

| Month 6 | 6237 ± 3765 | 4127 ± 2742 | 0.001 |

| Month 9 | 6023 ± 3598 | 4762 ± 3793 | 0.001 |

| Month 12 | 6769 ± 4338 | 4559 ± 3847 | 0.001 |

| Month 15 | 6691 ± 4561 | 4105 ± 2679 | 0.002 |

| Month 18 | 6331 ± 4170 | 4525 ± 2888 | 0.02 |

| Month 21 | 5857 ± 3475 | 4666 ± 3572 | 0.04 |

| Month 24 | 5498 ± 2716 | 4595 ± 3596 | 0.04 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD.

Renal Function

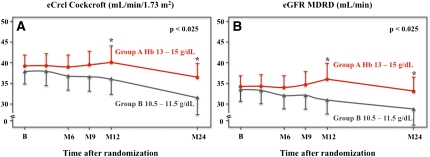

At baseline, the mean estimated creatinine clearance (eCrcl) was 38.3±10.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (calculated by Cockcroft–Gault formula) in both groups (Table 1). At year 2, the mean eCrcl decreased by 2.4±1.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in group A and 5.9±1.1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in group B (P=0.03), and similar results were found using other formulas (Table 5). At the end of the study, the mean last available estimated GFR (eGFR) using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula was 32.6±12.7 ml/min for group A and 28.0±13.8 ml/min for group B (P=0.03). Figure 3 shows the values of the eCrcl (Figure 3A) and eGFR (Figure 3B) during the 2-year follow-up period. The difference between groups became significant after 12 months, showing that the rate of decline of renal function was lower in patients with complete anemia correction (group A) than in patients with partial anemia correction (group B). A doubling of serum creatinine occurred in 2 patients in group A and 10 patients in group B (P<0.01). Few patients had significant proteinuria at inclusion, without any difference between the two groups. During the follow-up, two new patients in group B had developed proteinuria. The variation in the urine protein to creatinine ratio between inclusion and the end of the study was 31.6±217.2 mg/mmol for group A and 22.7±199.0 mg/mmol for group B (P=0.90).

Table 5.

Efficacy endpoints at the end of the study

| Endpoint | Group A (n=63) | Group B (n=62) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR at the end of study (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | |||

| Cockcroft–Gault’s formula | 36.5 ± 13.2 | 31.8 ± 15.1 | 0.05 |

| abbreviated MDRD’s formula | 32.6 ± 12.7 | 28.0 ± 13.8 | 0.05 |

| Nankivell’s formula | 37.4 ± 16.1 | 32.9 ± 19.6 | 0.10 |

| eGFR variation (baseline to month 24; ml/min per 1.73 m2) | |||

| Cockcroft–Gault’s formula | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 0.02 |

| abbreviated MDRD’s formula | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 0.01 |

| Nankivell’s formula | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 0.02 |

| ESRD n (%) | 3 (4.8) | 13 (21) | 0.01 |

| doubling in serum creatinine n (%) | 2 (3.2) | 10 (16.1) | 0.01 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD or n (%) when appropriate.

Figure 3.

Changes during 24 months of follow-up in (A) eCrcl calculated with the Cockcroft–Gault formula and (B) eGFR calculated with the abbreviated MDRD formula. Red circles and line are for patients in group A, and black triangles and line are for patients randomized to group B. The difference between groups became significant after 12 months, showing that the rate of decline of renal function was lower in patients with complete anemia correction (group A) than in patients with partial anemia correction (group B).

ESRD and Survival

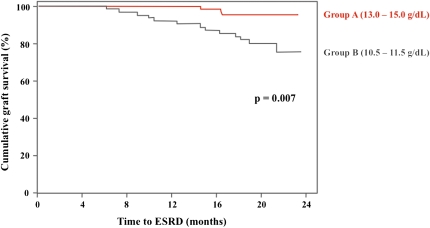

At the end of the study, progression to ESRD and return to dialysis occurred in 3 patients (4.8%) in group A and 13 patients (21%) in group B (P=0.01) (Table 3). The death-censored graft survival at 2 years was 94.6% in group A and 80.0% in group B (P=0.01) (Figure 4). The time to returning to dialysis was higher in group A than in group B (17.8±1.2 versus 15.4±5.5 months). One patient died in group A (esophageal carcinoma), and three patients dies in group B (hemophagocytosis, amyloidosis, and severe polyradiculitis). No acute graft rejection was observed during the 24-month follow-up period.

Figure 4.

Death-censored Kaplan–Meir graft survival. Red line is for patients in group A, and black line is for patients in group B.

Quality of Life

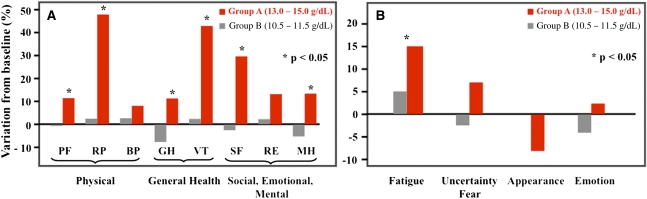

At 6 months, the improvement in QoL, using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey,19 was significantly better compared with baseline in group A than in group B regarding general health (P=0.01), vitality (P=0.01), physical function (P=0.04), physical role (P=0.02), mental health (P=0.04), and social function (P=0.05), which is shown in Figure 5A. The difference between groups was maintained at month 12 for vitality (P=0.03) and physical role (P=0.01). Regarding the analyses performed with the Kidney Transplant Questionnaire-25,20 a statistical significance between groups A and B was reached at 6 months and maintained at 12 months in the dimension of fatigue (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of anemia correction on quality of life. Variation in QoL assessment using the (A) Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire and (B) Kidney Transplant Questionnaire-25 questionnaire between baseline and 6 months. During the follow-up, improvement in QoL assessed using the SF-36 was observed only in group A for most items, whereas with the KTQ questionnaire, improvement was significant only for fatigue. Values are expressed as adjusted means. Positive changes indicate improvement in the quality of life, whereas negative changes indicate worsening of the quality of life. PF, physical functioning; RP, role physical; BP, physical pain; GH, general health; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role emotional; MH, mental health.

Safety

The safety analysis included all patients receiving at least one dose of study treatment (group A: n=63, group B: n=49). Adverse events, most of which were mild or moderate, occurred in 65.1% and 67.3% (P=0.80) in groups A and B, respectively (Table 6). A total of 57 patients (46%) were hospitalized: 30 patients in group A and 27 patients in group B. Cardiovascular events occurred more frequently in group B, mainly as a result of the higher incidence of ESRD in this group. There were no stroke or cardiac events in group A. Blood pressure measurements were similar between the two groups during the follow-up period (Table 7).

Table 6.

Frequency of adverse events at the end of the study

| Adverse Events | Group A (n=63) | Group B (n=49) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with adverse events n (%) | 41 (65.1) | 33 (67.3) | 0.80 |

| Patients with serious adverse events n (%) | 32 (50.8) | 22 (44.9) | 0.57 |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 | 4 (8) | 0.03 |

| acute cardiac failure | 0 | 2 (4) | 0.18 |

| arrhythmia | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.43 |

| myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.43 |

| Vascular disorders | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | 0.69 |

| de novo hypertension | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1.00 |

| peripheral vascular disorders | 2 (3) | 1a (2) | 1.00 |

| Nervous system | 1 (1.5) | 2 (4) | 0.58 |

| headache | 0 | 2 (4) | 0.18 |

| convulsion | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Infections | 11 (17.5) | 7 (14) | 1.00 |

| urinary tract infection | 8 (12.7) | 1 (2) | 0.07 |

| pneumonia | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 1.00 |

| bacteriemia | 3 (4.5) | 3 (6) | 1.00 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5 (8) | 5 (10) | 1.00 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 1b (1.5) | 2b (4) | 1.00 |

One phlebitis.

One diabetes in group A and one uncontrolled diabetes in group B.

Table 7.

Blood pressure profile during the study

| BP (mmHg) | Group A | Group B | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 0 | |||

| systolic | 136 ± 17 | 142 ± 16 | 0.07 |

| diastolic | 79 ± 10 | 79 ± 10 | 1.00 |

| Month 6 | |||

| systolic | 138 ± 22 | 141 ± 21 | 0.40 |

| diastolic | 81 ± 11 | 79 ± 13 | 0.35 |

| Month 12 | |||

| systolic | 139 ± 17 | 141 ± 20 | 0.50 |

| diastolic | 83 ± 11 | 80 ± 13 | 0.16 |

| Month 24 | |||

| systolic | 135 ± 17 | 141 ± 20 | 0.07 |

| diastolic | 79 ± 10 | 79 ± 12 | 1.00 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide evidence that a complete correction of anemia (Hb≥13.0 g/d) in KTR after 2 years slows the decline in renal function, prolongs graft survival, and improves QoL. Importantly, this Hb target was well tolerated and not associated with an increase in the number of cardiovascular or thrombotic events.

In our study, complete correction of anemia was achieved with a relatively low dose of epoetin-β given weekly, which is comparable with its use in the setting of CKD to normalize Hb values. In the Cardiovascular Risk Reduction by Early Anemia Treatment with Epoetin-β (CREATE) study,13 the median weekly epoetin dose was 5000 IU in the group assigned to the target Hb of 13.0–15.0 g/dl. Our findings were also consistent with the median dose of 4000 IU per week in KTR in the Transplant European Survey on Anemia Management study.1

Our study does not confirm the recent findings of a large retrospective study that identified an excess mortality rate in KTR in whom a target Hb level of 14 g/dl was obtained with the use of an ESA compared with patients not receiving an ESA.8 Because of the inherent methodological differences, particularly in Hb levels, comparison of this study with our study is difficult. Molnar et al.,7 in a single-center cohort of 938 KTR followed for 4 years, have found that graft loss and mortality were significantly higher in anemic patients; in a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, anemia independently predicted both mortality (hazard ratio=1.69, 95% confidence interval=1.11–2.56) and graft failure (hazard ratio=2.46, 95% confidence interval=1.48–4.09). Finally, the work by Kamar and Rostaing10 showed that the occurrence of PTA at 1 year after transplantation was harmful in the long term to both graft and patient survival.

Taking into account the disappointing results of large-scale studies regarding the efficacy and safety of high Hb targets with ESA therapy in CKD patients, including patients with diabetes, our results are unexpected and raise important issues. Anemia correction with a target Hb level of 13 g/dl using an ESA does not prevent progression to ESRD in patients with CKD and does not slow GFR decline in patients with severe CKD of varying etiology, including hypertension, chronic glomerulonephritis, and diabetes.12–14,21–24 This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that chronic allograft nephropathy and CKD are fundamentally different entities in terms of pathophysiology and outcome. Chronic allograft nephropathy results from various immunologic and nonimmunologic injuries and leads to ESRD at a frequency of <5%/yr.

Anemia correction with epoetin-β in KTR is not associated with an increase in cardiovascular events or stroke, which has been reported in the Correction of Hemoglobin and Outcomes in Renal Insufficiency (CHOIR)12 and Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy (TREAT)14 studies. To explain these observed differences in risk, potential differences in study populations and design should be considered. Patients in the CAPRIT study had a far less severe cardiovascular profile, with an annual cardiovascular event rate that was extremely low compared with those rates of patients in the CHOIR12 and TREAT14 studies. Moreover, the epoetin doses were more than two times the doses used in our study to achieve similar Hb levels, indicating a more severe cardiovascular risk profile, a more pronounced inflammatory state and a higher state of resistance to ESA therapy in the two aforementioned studies.22,23 However, this safety profile should be interpreted with caution regarding the size of our population and the lack of power to detect low rate events.

The emergence of innovative nephroprotective strategies constitutes an important step to the improvement of renal allograft survival. These advances are underpinned by the characterization of tissue responses to injury at the biologic level. Ischemia, defined as the shortage of blood in a tissue, is a well known contributor to chronic allograft nephropathy. Tissues subjected to ischemia activate various stress responses, including programmed cell death, fibrogenesis, and inflammation, ultimately leading to irreversible structural deterioration.25 Thus, targeting renal ischemia opens the door to promising tissue protective strategies. The nephroprotection afforded by the correction of anemia with ESAs raises questions regarding the respective roles of anemia correction and the tissue protective properties of ESAs. Our study was not designed to give a precise answer, because the patients with high Hb target levels received more epoetin-β than those patients with low Hb target levels. At the biologic level, hypoxia promotes inflammation, cell death, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and fibrosis,25,26 and the beneficial effects of anemia correction on these processes are supported by experimental and clinical data.27,28 Recombinant human erythropoietin (RHuEPO) is known to inhibit the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and reduce fibrogenesis.29 Importantly, the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in the renal allograft may result from immunologic and nephrotoxic injuries and is predictive of rejection.30–32 Taking into account the role of calcineurin inhibitors in the progression of chronic allograft nephropathy and their importance in mediating the epithelial to mesenchymal transition, one can speculate that the nephroprotective effects of epoetin-β may be at least partly caused by the inhibition of calcineurin inhibitor-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition by RHuEPO. Thus, correcting tissue hypoxia by raising Hb levels adds to the tissue protective effects of RHuEPO. Because of the lack of histologic data, one cannot exclude the possibility that these short-term results may be the consequence of an increase in intrarenal hemodynamics. Longer follow-up times of renal and nonrenal transplant patients, who are often anemic and develop progressive CKD, could help to better characterize the tissue-protective properties of RHuEPO under calcineurin inhibitor pressure.

Additionally, our findings reinforce data showing that ESAs improve QoL,5 and a correction of Hb to the range observed in group A in this study has a positive impact on general health, exercise capacity, and physical scores. Correcting renal anemia also reduces the need for red cell transfusion in CKD patients and KTR.12,13

Limitations of our study include the limitations of a nonblinded study. Because the study was not large enough and not of long enough duration compared with the CREATE, TREAT, and CHOIR studies, we have to interpret with caution our results concerning the low number of cardiovascular complications at higher Hb target. Additionally, serial biopsies at inclusion and the end of follow-up and more sensitive markers of renal damage, such as urinary N-GAL or KIM-1 measurements and proteomic analysis, would have also helped to better understand the underlying mechanism by which epoetin-β preserves renal function. Because patients entered the study, on average, 8 years after transplantation, it would have been difficult for ethical reasons to realize such systemic biopsies. In addition, exact GFR measurements would have been helpful, but only a few transplant centers used routinely exact GFR measurements (mostly by iohexol clearance) in our country. However, the calculations with the three formulas and the serum creatinine levels were concordant to show a better preservation of the renal function in patients randomized to the high Hb target. Finally, assessments of QoL in nonblinded studies limit the interpretation of the data.

In conclusion, anemia correction with epoetin-β in KTR with moderate renal dysfunction slows the decline in GFR, reduces the incidence of ESRD, and improves QoL without increasing the risk of cardiovascular events. This study provides evidence that kidney disease in KTR constitutes a particular entity and that the results from nephroprotection studies conducted in CKD patients should not be directly extrapolated to KTR. Additional studies should be carried out to confirm whether complete correction of anemia in KTR might impact patient survival and establish the optimal Hb target level in KTR.

CONCISE METHODS

This was a randomized, national parallel group controlled trial conducted in 17 centers in France.

Study Population

Patients were enrolled if they met the following criteria: 18–80 years of age, primary or secondary kidney allograft performed at least 12 months before, eCrcl less than 50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 of body surface area (Cockcroft–Gault formula), stable renal function in the previous 3 months (serum creatinine variation<20%), using standard immunosuppressive double or triple therapy (combination of antiproliferative agent and/or corticoids and a calcineurin inhibitor; sirolimus not recommended), and anemia (Hb=11.5 g/dl) without iron deficiency (serum ferritin level≥50 µg/L, transferrin saturation≥20%). Antihypertensive therapy was used to achieve systolic BP<140 mmHg and diastolic BP<80 mmHg.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned (1:1 ratio) to receive epoetin-β (Neorecormon; Roche) to achieve a target Hb of 13–15 g/dl (group A, complete correction) or 10.5–11.5 g/dl (group B, partial correction). Randomization was stratified by center, age, gender, eCrcl, graft duration, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. Patients were followed for 24 months or until they were withdrawn from the study or lost to follow-up. Patients had monthly visits during the anemia correction phase (lasting 3 months) and were seen every 3 months during maintenance phase. Administered subcutaneously, the treatment was initiated with a low dose of epoetin-β (to the discretion of each investigator), and the dose was steadily increased. Dose increases of 25–50% were allowed when Hb level increase at 4 weeks after initiation was <0.5 g/dl; similarly, a 25–50% decrease in dose was allowed when the Hb level increased >2 g/dl in the first 4 weeks of treatment.

Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was the variation in eCrcl (calculated by Cockcroft–Gault formula) between the time of inclusion in the study and the 24-month follow-up assessment. Secondary outcomes included the GFR estimated by the Nankivell and MDRD formulas doubling of serum creatinine and proteinuria. Number of patients who progressed to ESRD, time to return to dialysis, graft survival, occurrence of acute graft rejection, and patient survival were also analyzed. For patients who returned to dialysis during the follow-up, the GFR was estimated at the time of the return to dialysis. QoL (determined using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey19 and the Kidney Transplant Questionnaire-2520), weekly dose of epoetin-β, blood transfusion requirements, and adverse events were secondary endpoints. At inclusion and each visit, blood pressure was measured, and the number of antihypertensive drugs was also collected.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using the SAS software (SAS Institute, Carry, NC) release 9.1. Results are presented as mean ± SD or n (%) when appropriate. We calculated by the method of covariance that we would need a sample size of 65 patients in each group to show a difference of 15% in the primary endpoint (no variation in eCrcl between baseline and the end of the 24-month study in group A and a decline in eCrcl in group B) with a type I error (α) set at 5% in a bilateral approach, a type II error (β) set at 10%, and a dropout/lost of follow-up rate of 10%. We used a mixed model approach, with missing values imputed by last observation carried forward for primary endpoint analysis. For the comparison of quantitative parameters (t test, variance analysis), the normality hypothesis for criteria parameters was controlled by a Shapiro–Wilks test. If these hypotheses were not fulfilled, a nonparametric approach was considered by the Wilcoxon test. For the comparison of qualitative parameters, chi-squared or Fisher exact tests were used. To assess the variables associated with outcomes, such as allograft loss, first acute graft rejection episode, return to dialysis, and death, Kaplan–Meier survival plots were used. The comparison between survival rates was made using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was indicated by a two-tailed P<0.05.

DISCLOSURES

G.C. reports receiving consulting fees and lecture fees from Roche France and lecture fees from Amgen, Genzyme, and Novartis.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions made by all physicians and the site study staff and thank Ms. Christine Lebel and Linda Ouabou for data management and clinical monitoring.

The CAPRIT study was funded in part by grants from Roche France and the Clinical Research Department of Amiens University Hospital.

Roche was not implicated in the collection and interpretation of the data of the CAPRIT study or the redaction of the manuscript.

The CAPRIT study was presented in part at the annual American Transplant Meeting in San Diego, CA, May 2–5, 2010.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “ESAs in Transplant Anemia: One Size Does Not “Fit All”,” on pages 192–193.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2011060546/-/DCSupplemental.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanrenterghem Y, Ponticelli C, Morales JM, Abramowicz D, Baboolal K, Eklund B, Kliem V, Legendre C, Morais Sarmento ALM, Vincenti F: Prevalence and management of anemia in renal transplant recipients: A European survey. Am J Transplant 3: 835–845, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winkelmayer WC, Kewalramani R, Rutstein M, Gabardi S, Vonvisger T, Chandraker A: Pharmacoepidemiology of anemia in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1347–1352, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choukroun G, Deray G, Glotz D, Lebranchu Y, Dussol B, Bourbigot B, Lefrançois N, Cassuto-Viguier E, Toupance O, Hacen C, Lang P, Mazouz H, Martinez F: Incidence and management of anemia in renal transplantation: an observational-French study. Nephrol Ther 4: 575–583, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molnar MZ, Mucsi I, Macdougall IC, Marsh JE, Yaqoob M, Main J, Courtney AE, Fogarty D, Mikhail A, Choukroun G, Short CD, Covic A, Goldsmith DJ: Prevalence and management of anaemia in renal transplant recipients: Data from ten European centres. Nephron Clin Pract 117: c127–c134, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawada N, Moriyama T, Ichimaru N, Imamura R, Matsui I, Takabatake Y, Nagasawa Y, Isaka Y, Kojima Y, Kokado Y, Rakugi H, Imai E, Takahara S: Negative effects of anemia on quality of life and its improvement by complete correction of anemia by administration of recombinant human erythropoietin in posttransplant patients. Clin Exp Nephrol 13: 355–360, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkelmayer WC, Chandraker A, Alan Brookhart M, Kramar R, Sunder-Plassmann G: A prospective study of anaemia and long-term outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 3559–3566, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molnar MZ, Czira M, Ambrus C, Szeifert L, Szentkiralyi A, Beko G, Rosivall L, Remport A, Novak M, Mucsi I: Anemia is associated with mortality in kidney-transplanted patients—a prospective cohort study. Am J Transplant 7: 818–824, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinze G, Kainz A, Hörl WH, Oberbauer R: Mortality in renal transplant recipients given erythropoietins to increase haemoglobin concentration: Cohort study. BMJ 339: b4018, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solid CA, Foley RN, Gill JS, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ: Epoetin use and Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative hemoglobin targets in patients returning to dialysis with failed renal transplants. Kidney Int 71: 425–430, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamar N, Rostaing L: Negative impact of one-year anemia on long-term patient and graft survival in kidney transplant patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation 85: 1120–1124, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhabra D, Grafals M, Skaro AI, Parker M, Gallon L: Impact of anemia after renal transplantation on patient and graft survival and on rate of acute rejection. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1168–1174, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, Reddan D; CHOIR Investigators: Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 355: 2085–2098, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt KU, Macdougall IC, Tsakiris D, Burger HU, Scherhag A; CREATE Investigators: Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med 355: 2071–2084, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, Feyzi JM, Ivanovich P, Kewalramani R, Levey AS, Lewis EF, McGill JB, McMurray JJV, Parfrey P, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, Solomon SD, Toto R; TREAT Investigators: A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 361: 2019–2032, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locatelli F, Aljama P, Canaud B, Covic A, De Francisco A, Macdougall IC, Wiecek A, Vanholder R; Anaemia Working Group of European Renal Best Practice (ERBP): Target haemoglobin to aim for with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: A position statement by ERBP following publication of the Trial to reduce cardiovascular events with Aranesp therapy (TREAT) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2846–2850, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linde T, Ekberg H, Forslund T, Furuland H, Holdaas H, Nyberg G, Tydén G, Wahlberg J, Danielson BG: The use of pretransplant erythropoietin to normalize hemoglobin levels has no deleterious effects on renal transplantation outcome. Transplantation 71: 79–82, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lietz K, Lao M, Paczek L, Górski A, Gaciong Z: The impact of pretransplant erythropoietin therapy on late outcomes of renal transplantation. Ann Transplant 8: 17–24, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez F, Kamar N, Pallet N, Lang P, Durrbach A, Lebranchu Y, Adem A, Barbier S, Cassuto-Viguier E, Glowaki F, Le Meur Y, Rostaing L, Legendre C, Hermine O, Choukroun G; NeoPDGF Study Investigators: High dose epoetin beta in the first weeks following renal transplantation and delayed graft function: Results of the Neo-PDGF Study. Am J Transplant 10: 1695–1700, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30: 473–483, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laupacis A, Pus N, Muirhead N, Wong C, Ferguson B, Keown P: Disease-specific questionnaire for patients with a renal transplant. Nephron 64: 226–231, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Locatelli F, Covic A, Eckardt KU, Wiecek A, Vanholder R; ERA-EDTA ERBP Advisory Board: Anaemia management in patients with chronic kidney disease: a position statement by the Anaemia Working Group of European Renal Best Practice (ERBP). Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 348–354, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon SD, Uno H, Lewis EF, Eckardt KU, Lin J, Burdmann EA, de Zeeuw D, Ivanovich P, Levey AS, Parfrey P, Remuzzi G, Singh AK, Toto R, Huang F, Rossert J, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA; Trial to Reduce Cardiovascular Events with Aranesp Therapy (TREAT) Investigators: Erythropoietic response and outcomes in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 363: 1146–1155, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan DN, Sapp S, Califf RM, Patel UD, Singh AK: Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int 74: 791–798, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh AK: Does correction of anemia slow the progression of chronic kidney disease? Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 638–639, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG: Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1819–1834, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deicher R, Hörl WH: Anaemia as a risk factor for the progression of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 139–143, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diskin CJ, Stokes TJ, Dansby LM, Radcliff L, Carter TB: Beyond anemia: the clinical impact of the physiologic effects of erythropoietin. Semin Dial 21: 447–454, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keithi-Reddy SR, Addabbo F, Patel TV, Mittal BV, Goligorsky MS, Singh AK: Association of anemia and erythropoiesis stimulating agents with inflammatory biomarkers in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 74: 782–790, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SH, Choi MJ, Song IK, Choi SY, Nam JO, Kim CD, Lee BH, Park RW, Park KM, Kim YJ, Kim IS, Kwon TH, Kim YL: Erythropoietin decreases renal fibrosis in mice with ureteral obstruction: Role of inhibiting TGF-β-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1497–1507, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson H, Ali S, McDonnell BJ, Burt AD, Kirby JA: Chronic renal allograft dysfunction: The role of T cell-mediated tubular epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 390–397, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jevnikar AM, Mannon RB: Late kidney allograft loss: What we know about it, and what we can do about it. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3[Suppl 2]: S56–S67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strutz F: Pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in chronic allograft dysfunction. Clin Transplant 23: 26–32, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]