Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The indications for nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) are broadening as more breast surgeons appreciate the utility of preserving the nipple-areolar complex. A number of incision locations are available to the mastectomy surgeon, including inframammary, lateral and periareolar approaches. The present study investigated the effect of these three incisions on reconstructive outcomes; specifically, nipple necrosis.

METHODS

A single-centre, retrospective review of 37 breast NSM reconstructions treated with immediate tissue expander reconstruction with acellular dermis between 2007 and 2008 was performed. The primary outcome was the incidence of nipple necrosis associated with periareolar, lateral and inframammary incisions. Secondary outcomes were the effects of radiation, chemotherapy and breast size on nipple necrosis.

RESULTS

Thirty-seven breast procedures performed on 20 patients were included in the present study. Periareolar incisions were used in 21 cases, lateral incisions in 14 and inframammary incisions in two. The periareolar incision was associated with a significantly higher incidence of nipple necrosis compared with lateral or inframammary incisions (38.1% versus 6.3%, P=0.028). Patients receiving breast radiation (45.5% versus 15.4%, P=0.066) and those with larger breast size (540.4 g versus 425.7 g, P=0.130) also demonstrated a modest trend toward an increased rate of nipple necrosis.

CONCLUSION

The periareolar incision results in a higher rate of nipple necrosis following NSM and immediate tissue expander breast reconstruction. Using the lateral or inframammary incision reduces the incidence of nipple necrosis and may help improve overall reconstructive and cosmetic outcomes.

Keywords: Acellular dermis, Breast reconstruction, Nipple-areola complex, Nipple-sparing mastectomy, Nipple necrosis, Tissue expansion

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Les indications de mastectomie sous-cutanée (MSC) augmentent à mesure que les chirurgiens du sein constatent l’utilité de conserver le complexe mamelon-aréole. Le chirurgien peut choisir divers foyers d’incision, y compris les abords inframammaire, latéral et périaréolaire. La présente étude portait sur l’effet de ces trois incisions sur les issues de la reconstruction, notamment la nécrose du mamelon.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

Les auteurs ont procédé à une analyse rétrospective monocentrique de 37 reconstructions mammaires avec expanseur tissulaire au moyen de derme acellulaire immédiatement après une MSC entre 2007 et 2008. L’issue primaire était l’incidence de nécrose du mamelon associée à une incision périaréolaire, latérale ou inframammaire. Les issues secon-daires étaient les effets de la radiation, de la chimiothérapie et de la dimension du sein sur la nécrose du mamelon.

RÉSULTATS

Trente-sept interventions mammaires effectuées auprès de 20 patient es ont fait partie de la présente étude. Dans 21 cas, l’incision périaréolaire était privilégiée, tandis que l’incision latérale l’était dans 14 cas et l’incision inframammaire, dans deux. L’incision périaréolaire s’associait à une incidence beaucoup plus élevée de nécrose du mamelon que l’incision latérale ou inframammaire (38,1 % par rapport à 6,3 %, P=0,028). Les patients sous radiothérapie du sein (45,5 % par rapport à 15,4 %, P=0,066) et ceux qui avaient de plus gros seins (540,4 g par rapport à 425,7 g, P=0,130) démontraient également une modeste tendance vers un taux plus élevé de nécrose du mamelon.

CONCLUSION

L’incision périaréolaire entraîne un taux plus élevé de nécrose du mamelon après une MSC suivie d’une reconstruction mammaire immédiate avec expanseur tissulaire. L’incision latérale ou inframammaire réduit l’incidence de nécrose du mamelon et peut contribuer à améliorer les issues reconstructives et esthétiques globales.

Since its initial description in the 1960s by Freeman (1,2), the use of the nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) has significantly increased (3,4). In general, NSM is considered for patients with T0 to T2 tumours smaller than 4.5 cm in size, further than 2.5 cm from the areolar edge and 4 cm from the nipple centre, and no clinical involvement of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC) or skin (5). Recent studies, however, report that NSM can be used in all cases in which total mastectomy is indicated when histological analyses of intraoperative frozen sections from sub-NAC tissues are negative (6).

From a reconstructive perspective, preservation of the NAC improves aesthetic outcomes without increasing the rate of cancer recurrence (7–11). The principal reconstructive benefit of the technique is preservation of the NAC; however, the NAC is also the most vulnerable anatomical element during the mastectomy and reconstructive procedures. If significant epidermolysis or full-thickness loss of the nipple occurs, then the advantage of performing a NSM is nullified. While a variety of NSM incisions are available to the breast surgeon, there is a paucity of data investigating the effects of incision type on reconstructive outcomes.

The most common incisions used in NSM are periareolar, lateral or inframammary (12–15). Several advantages and disadvantages have been described for each incision location. Periareolar incisions enable central access to all quadrants of the breast during the mastectomy while maintaining a well-hidden incision scar within the periphery of the NAC (6). However, following mastectomy, a significant source of blood flow to the NAC occurs through the skin flaps and dermal vascular plexus. Therefore, making an incision across one-half of the NAC can disrupt this critical blood supply. Lateral incisions also allow for easy central access to all quadrants of the breast, but do not cut across the skin-based blood supply to the nipple (because the incision is axial to the NAC periphery). Inframammary incisions allow the scar to be well-concealed in the inframammary fold with very minimal disruption of the skin-based blood supply to the NAC (6,7,11,12). The problem with this approach lies in the difficulty of accessing the upper quadrants of the breast for mastectomy (7,11).

There is significant variability in the literature regarding the incidence of nipple necrosis with varying incision location. For example, the reported incidence of nipple necrosis with an inframammary approach ranges between 2% and 67% (9,13,16–22). A potential rationale for the wide divergence in the nipple necrosis outcomes stems from the variability in surgical methodology; in some cases, outcomes with both autologous and expander implant-based reconstructions were combined.

The present study assessed the relationship between incision choice and NAC survival by selecting cases involving a standardized oncological and reconstructive technique with the only variable relating to incision location – periareolar, lateral or inframammary. While the primary outcome measure was nipple necrosis, the effects of radiation, chemotherapy, breast size and intraoperative expansion on NAC survival were also analyzed.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board approved the present study. All patients undergoing NSM followed by acellular dermis-assisted tissue expander breast reconstruction between 2007 and 2008 were identified. Medical records were retrospectively reviewed. Demographic, oncological, procedural and reconstructive data were recorded and outcomes assessed. Each mastectomy was considered as an independent event in bilateral cases. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 (IBM Corporation, USA).

NSM

All mastectomies were performed by one of two breast oncologists (NH or SK). The technique varied only by choice of incision location: periareolar, lateral or inframammary. The periareolar incision involved a curvilinear incision along the border of the areola, around approximately one-half of its circumference, with a lateral extension of 4 cm to 6 cm. The lateral incision extended out from the lateral edge of the areola for 6 cm to 8 cm. The inframammary incision was placed 1 cm to 2 cm superior and parallel to the inframammary fold for a length of 8 cm to 10 cm. In general, inframammary incisions were only ued in women with relatively small breasts (B cup or smaller) to mitigate issues related to surgical access to the upper pole during the mastectomy. In all cases, the NAC was dissected away from the breast tissue at the level just beneath the dermis. The nipple was inverted to ensure complete removal of ductal tissue, but was not cored. Absence of tumour involvement of the NAC was confirmed with frozen section histological analysis of the sub-NAC breast tissue. After the mastectomy was completed, the weight of excised breast tissue was measured, recorded and used as surrogate marker to determine breast size.

Acellular dermis-assisted tissue expander breast reconstruction

All breast reconstructions were performed by one of two plastic surgeons (NF or JK), using identical technique. Following NSM, the pectoralis muscle was disinserted inferiorly and elevated off of the chest wall. A sheet of acellular dermis (FlexHD, Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, USA, or Alloderm, Lifecell, USA) was then fashioned as a soft tissue sling to recreate the inferior pole. The acellular dermis was sutured inferiorly to the inframammary fold, laterally to the serratus fascia and superiorly to the free edge of the pectoralis muscle. A tissue expander (McGhan Medical, USA) was then placed in the newly created submuscular-subgraft pocket. In cases where a one-stage reconstructive technique was used, a moderate plus profile silicone gel implant or adjustable expander implant (Mentor, USA) was used. The expander was judiciously expanded intraoperatively to the degree of skin excess, such that the skin edges could be approximated without undue tension. Two 7 mm clot-stop drains were placed in the subcutaneous space using separate stab incisions.

RESULTS

Thirty-seven NSM (17 bilateral cases, three unilateral cases) underwent immediate tissue expander breast reconstruction with acellular dermis. The mean age of patients at the time of mastectomy was 44.4 years (range 33 to 62 years). The mastectomies were prophylactic in 22 cases and therapeutic in 15 cases. Of the 22 prophylactic cases, five had pathological evidence of carcinoma on final pathology. The incision location for the NSM was periareolar in 21 cases, lateral in 14 and inframammary in two (Figures 1 and 2). Eleven breasts received neoadjuvant radiation, while two also received adjuvant radiation therapy. Thirteen patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no cases of subareolar involvement of tumour on final pathology.

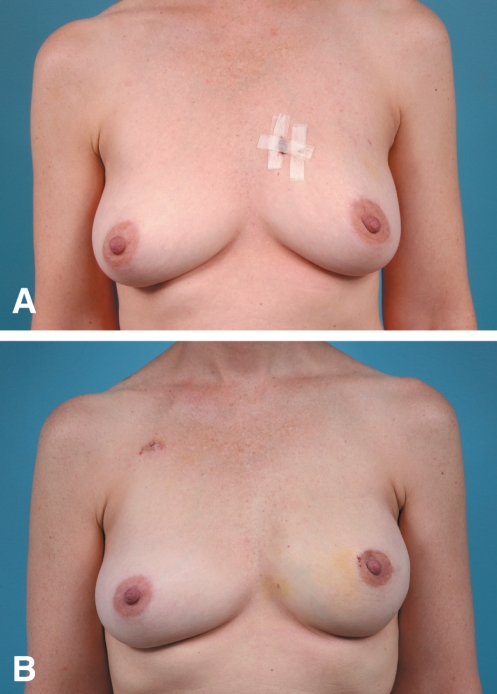

Figure 1.

Unilateral periareolar incision. Preoperative (A) and four-month postoperative (B) photographs of a 43-year-old woman with left breast cancer who underwent unilateral expander/implant breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy using a periareolar incision

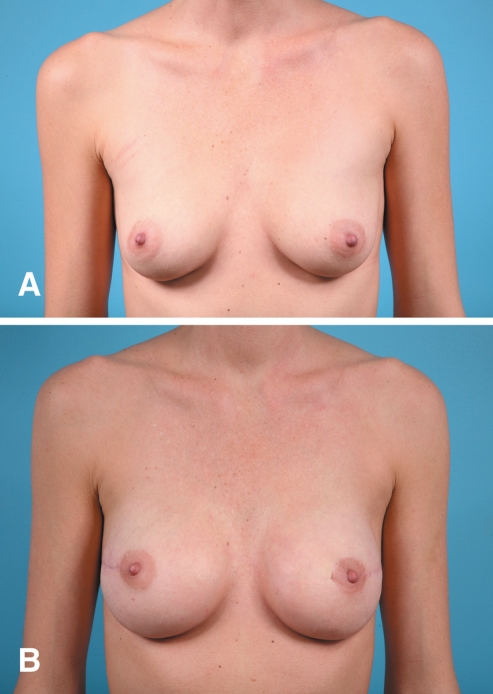

Figure 2.

Bilateral lateral incisions. Preoperative (A) and two-month postoperative (B) photographs of a 33-year-old woman with BRAC-1 mutations and a strong family history of breast cancer who underwent bilateral expander/implant breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy using lateral incisions

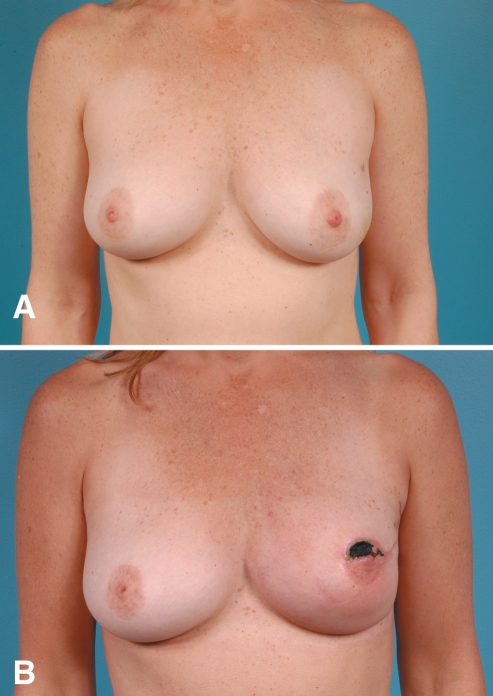

The mean weight of the mastectomy specimens was 454 g (range 156 g to 1074 g). Mean intraoperative tissue expander fill volume was 337.4 mL (range 150 mL to 600 mL). On average, intraoperative fill achieved 79.8% of final fill volume. The mean number of expansions to achieve final fill volume was 1.90 (mean final fill volume was 421.5 mL). The mean follow-up time was 38.3 weeks (range 24 to 96 weeks). Sixteen breasts (43.2%) experienced complications (Table 1). Nine cases (24.3%) of nipple necrosis, six (16.2%) soft tissue infections, one (2.7%) hematoma and one seroma (2.7%) occurred. There were no cases of implant migration, implant exposure or early capsular contracture. There were two prosthetic failures: one tissue expander rupture and one implant leak. Of the nine cases of nipple necrosis, four were partial and five involved the entire NAC. The partial cases were successfully managed with debridement (Figure 3). The cases of necrosis involving the entire NAC required resection and reconstruction. Four patients with soft tissue infection required explantation of their prosthesis and two were successfully treated with oral antibiotics. One patient who required explantation subsequently underwent elective autologous reconstruction using a free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap. No cases of recurrence were reported at the most recent follow-up.

TABLE 1.

Complication rates of 20 patients (37 procedures) who underwent nipple-sparing mastectomies with one of three incision types followed by two-stage tissue expander implant reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix

| Incision type

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Periareolar | Lateral or inframammary | P | |

| Number | 37 | 21 | 16 | |

| Nipple necrosis | 9 (24.3) | 8 (38.1) | 1 (6.25) | 0.028 |

| Complete | 5 (13.5) | 5 (23.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.046 |

| Partial | 4 (10.8) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (6.25) | 0.412 |

| Infection | 6 (16.2) | 4 (19.0) | 2 (12.5) | 0.472 |

| Hematoma | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.568 |

| Seroma | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.568 |

| Debridement | 3 (8.1) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (6.25) | 0.603 |

| Explantation | 4 (10.8) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.091 |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified

Figure 3.

Partial nipple necrosis. A 48-year-old woman with left breast cancer who underwent unilateral immediate expander acellular dermis breast reconstruction and contralateral breast augmentation following nipple-sparing mastectomy using a periareolar incision. A Preoperative view. B Partial-thickness nipple necrosis. Note the evolving eschar two months after expander placement

Complication rates according to mastectomy incision location are summarized in Table 1. Most notably, periareolar incision placement resulted in significantly more cases of nipple necrosis compared with the other incision methods (38.1% versus 6.25%, P=0.028). Additionally, when present, cases of nipple necrosis with a periareolar incision were more likely to result in complete NAC necrosis (23.8% versus 0.0%, P=0.046). There were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of soft tissue infection between the two groups (19.0% versus 12.0%, P=0.472). However, the four patients with periareolar incisions who contracted a soft tissue infection required explantation of their prostheses, while the two patients with lateral incisions and soft tissue infection were able to be treated with oral antibiotics. These explantation rates demonstrated a trend toward significance (19.0% versus 0.0%, P=0.091).

Secondary outcomes including radiation and larger breast size demonstrated a trend toward increased rates of nipple necrosis. Specifically, there was a trend toward increased nipple necrosis (45.5% versus 15.4%, P=0.066) and soft tissue infection (36.4% versus 7.7%, P=0.096) in breasts receiving radiation. There was also a trend toward increased breast size (weight of breast tissue excised) in cases demonstrating nipple necrosis (540.4 g versus 425.7 g, P=0.130). Seven of the nine cases of nipple necrosis occurred in breasts larger than 500 g. There were no incidences of nipple necrosis in breasts smaller than 350 g. There was no difference in the incidence of nipple necrosis in patients receiving chemotherapy (P=0.643). There was also no difference in initial intraoperative tissue expander fill volume (P=0.837), per cent intraoperative tissue expander fill volume (initial fill volume/ final fill volume [P=0.694]), final tissue expander fill volume (P=0.797) or number of expansions (P=0.917).

DISCUSSION

Although NSM may allow for better aesthetic outcome (2), the most significant complication is the loss of the very element that makes it a worthwhile procedure – the nipple. While several studies (5–15) have alluded to risk factors for developing nipple necrosis, a clear and unified surgical technique with stratified analysis has not linked nipple necrosis to NSM technique. Our study focused on a standardized reconstructive technique subject to simple statistical tests, and clearly demonstrated that the periareolar incisions were associated with a higher incidence of nipple necrosis than lateral and inframammary incisions.

In the senior author’s experience, there are significant differences in the ability to intraoperatively expand tissues between NSM and a skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) (79.8% versus 63.2%, P=0.037) (23). Although it is true that NSM creates a larger envelope for expansion than SSM, permitting greater expansion, the increased volume of the tissue expander may place more tension on the skin flaps, thereby promoting ischemia (24,25). Several techniques have been described to decrease the incidence of nipple necrosis following NSM (11). The present study specifically identified the periareolar incision as a risk factor for developing nipple necrosis during NSM. The periareolar incision resulted in nipple necrosis in 38.1% of breasts undergoing NSM. In 23.8% of cases, nipple necrosis was complete, requiring excision and subsequent reconstruction of the NAC. In comparison, the lateral or inframammary incision resulted in 6.3% nipple necrosis. All incidences of nipple necrosis that occured after using these incisions were partial in nature, and the NAC was successfully salvaged. In addition, 19.0% of periareolar incisions demonstrated soft tissue infection and all of these cases required explantation. While 12% of lateral or inframmary incisions also demonstrated soft tissue infection, none required explantation and all where successfully treated with oral antibiotics.

The results of the present study are consistent with most other reports of NSM in the literature (7,11,12) and can be explained by the extent of NAC blood flow disruption associated with the various incision patterns. The periareolar incision is highly dependent on collateral blood flow, which varies with the length of periareolar portion of the incision. Periareolar incisions greater than one-third the circumference of the NAC are problematic in this regard. The lateral and inframammary incisions result in less disruption of blood vessels to the NAC by preserving the collateral blood supply from the intercostal arteries (6,7,11,14).

Secondary factors affecting nipple necrosis, including radiation and breast size, have been described in previous reports and merit discussion. In the present study, 45.5% of breasts receiving preoperative radiation demonstrated nipple necrosis compared with a 15.4% incidence of nipple necrosis in breasts not receiving radiation.

These results are consistent with previous studies of acellular dermis-assisted reconstruction following SSM (23,26–28). Our results also demonstrate a trend toward larger breast size in breasts with nipple necrosis. Seven of the nine cases with nipple necrosis in the present study had breasts larger than 500 g, whereas no incidences of nipple necrosis were seen in breasts smaller than 350 g. Whether this is because of intrinsic issues of vascularity due to longer mastectomy flaps or because of attempted high-volume expansion (or a combination of the two) is unclear.

There are several limitations of the present study. Although the reconstructive technique was standardized, there are confounding variables associated with the mastectomy that could not be controlled. For example, the thickness of the mastectomy skin flap and method of mastectomy flap dissection (electrocautery versus sharp dissection) were not controlled. Mastectomy flap thickness can have a dramatic effect on blood supply and is highly dependent on the surgical oncologist’s technique.

Incorporating the findings of the present study, our recommended algorithmic approach to NSM and subsequent reconstruction is as follows. For patients with small-size breasts without tumours in the upper outer breast quadrant, an inframammary incision should be used. In cases not meeting these criteria, the lateral incision is recommended. Cases in which blood supply to the nipple is perceived to be decreased either due to incision type, breast size, irradiation status or flap thickness, reconstruction with autologous tissues is strongly believed to increase blood supply to the NAC. In prosthetic reconstructive cases, the use of acellular dermis and limited initial intraoperative expansion should be considered to limit tension on flaps that are at greater risk for nipple necrosis.

CONCLUSION

NSM coupled with acellular dermis-assisted expander implant breast reconstruction results in an acceptable rate of complications. The periareolar incision heightens the risk of nipple necrosis compared with a lateral or inframammary approach. Other risk factors for nipple necrosis may include use of the radiation and breast size. Larger, multivariate studies are warranted to further evaluate these risk factors associated with NSM breast reconstruction.

Footnotes

DICLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman BS. Subcutaneous mastectomy for benign breast lesion with immediate or delayed prosthetic replacement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1962;30:676–82. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman BS. Complications of subcutaneous mastectomy with prosthetic replacement, immediate or delayed. South Med J. 1967;60:1277–80. doi: 10.1097/00007611-196712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kissin MW, Kark AE. Nipple preservation during mastectomy. Br J Surg. 1987;74:58–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800740118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinton CP, Doyle PJ, Blamey R, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy for primary operable breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1984;71:469. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voltura AM, Tsangaris TN, Rosson GD. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: Critical assessment of 51 procedures and implications for selection criteria. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3396–401. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paepke S, Schmid R, Fleckner S, et al. Subcutaneous mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola skin: Broadening the indications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:288–92. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c7d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spear SL, Hannan CM, Willey SC, Cocilovo C. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1665–73. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a64d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wellisch D, Schain W, Noone B, et al. The psychological contribution of nipple addition in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:699–704. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber B, Krause A, Reimer T, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areolar complex and autologous reconstruction is an oncologically safe procedure. Ann Surg. 2003;238:120–7. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000077922.38307.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber B, Krause A, Dieterich M, et al. The oncological safety of skin-sparing mastectomy with conservation of the nipple-areola complex and autologous reconstruction: An extended follow-up study. Ann Surg. 2009;249:461–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a044f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wijayanayagam A, Kumar AS, Foster RD, Esserman LJ. Optimizing the total skin-sparing mastectomy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:38–45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Etienne CA, Cody Iii HS, III, Disa JJ, Cordeiro P, Sacchini V. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: Initial experience at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and a comprehensive review of literature. Breast J. 2009;15:440–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowe JP, Jr, Kim JA, Yetman R, Banbury J, Patrick RJ, Baynes D. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: Technique and results of 54 procedures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:148–50. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margulies AG, Hochberg J, Kepple J, Henry-Tillman RS, Westbrook K, Klimberg VS. Total skin-sparing mastectomy without preservation of the nipple-areola complex. Am J Surg. 2005;190:907–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stolier AJ, Sullivan SK, Dellacroce FJ. Technical considerations in nipple-sparing mastectomy: 82 consecutive cases without necrosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1341–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caruso F, Ferrara M, Castiglione G, et al. Nipple sparing subcutaneous mastectomy: Sixty-six months follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:937–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacchini V, Pinotti JA, Barros AC, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer and risk reduction: Oncologic or technical problem? J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:704–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petit JY, Veronesi U, Orecchia R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in association with intraoperative radiotherapy (ELIOT): A new type of mastectomy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:47–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crowe JP, Jr, Kim JA, Yetman R, Banbury J, Patrick RJ, Baynes D. Nipple-sparing mastectomy: Technique and results of 54 procedures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:148–50. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psaila A, Pozzi M, Barone Adesi L, et al. Nipple sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction: A short term analysis of our experience. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:309–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komorowski AL, Zanini V, Regolo L, Carolei A, Wysocki WM, Costa A. Necrotic complications after nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy. World J Surg. 2006;30:1410–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0650-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bistoni G, Rulli A, Izzo L, Noya G, Alfano C, Barberini F. Nipple sparing mastectomy: Preliminary results. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:495–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawlani V, Buck D, Heyer K, Kim JYS. Tissue expander breast reconstruction using pre-hydrated human acellular dermis. Ann Plast Surg. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181f3ed0a. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson K, Hunt TK, Brennan SS, Mathes SJ. Tissue oxygen measurements in delayed skin flaps: A reconsideration of the mechanisms of the delay phenomenon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:328–36. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198808000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottrup F, Firmin R, Hunt TK, Mathes SJ. The dynamic properties of tissue oxygen in healing flaps. Surgery. 1984;95:527–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spear SL, Parikh PM, Reisin E, Menon NG. Acellular dermis-assisted breast reconstruction. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:418–25. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bindingnavele V, Gaon M, Ota KS, Kulber DA, Lee DJ. Use of acellular cadaveric dermis and tissue expansion in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones FR, Tauras AP. A periareolar incision for augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51:641–4. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197306000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]