Family caregivers often rely on clinicians to initiate family discussions about hospice and care of the dying1. Mortality communication, or talk between terminally-ill patients and families about impending death, is encouraged in hospice 2. Most terminally-ill patients use this time to discuss spiritual and psychosocial matters not previously broached between family members 3. Families with open communication prior to the disease maintain the pattern throughout the illness as the situation prompts families to view this as a time to be together 4. However, not all families are able to have open conversations about dying and death. Some families attempt to hide hospice care and instruct healthcare providers not to mention hospice in front of the patient, not to tell the patient that they are terminal, and not to talk about dying and death in front of the patient 5. Overall, families of hospice patients report difficulty talking about the process of dying and death 5. This study investigated concerns shared by informal caregivers (friends or family members) who were designated or legally appointed as the family caregiver of a hospice patient to learn more about family communication patterns during hospice caregiving. We hereafter refer to this group as family caregivers.

Previous work identifies that caregivers in families who are likely to agree with one another report better relationships with the patient, experience less burden, are more satisfied with patient care, have greater caregiver mastery, and have less depressive symptoms 6. It can be surmised that families who are able to quickly achieve consensus regarding decisions have open and regular family interaction and communication 6. On the other hand, caregivers in families that have difficulty reaching agreement about care report greater problems with the patient’s behavior 6 and families who have a prior history of family communication constraints are more likely to experience family conflict 7. However, little is known about the strain placed on family caregivers as a result of these varying family communication patterns. Assessment of family communication patterns may identify family caregivers in need of clinician intervention as well as the most useful kind of interventions 7. Thus, we sought to examine how family communication patterns influence caregiver concerns during the caregiving experience in hospice. Specifically, we asked the following research questions: (1) How do family communication patterns influence the concerns of hospice caregivers? and (2) What is the extent to which family communication patterns determine hospice caregiver communication needs?

Theoretical Framework

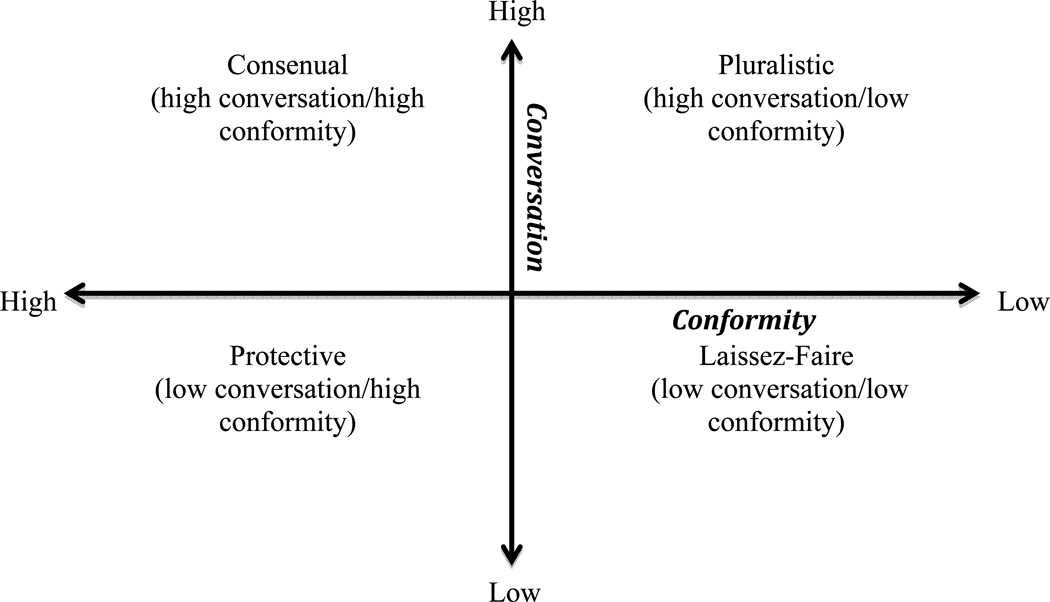

According to Family Communication Patterns Theory (FCPT), family members share a unique relational history that establishes implicit and explicit rules for communicating with each other 8,9,10–12. Family rules govern appropriate topics for discussion (family conversation) as well as establish a hierarchy among family members (family conformity)8,9,10–12. Family conversation can vary from free, spontaneous interaction between family members (high) to limitations on family topics and time spent communicating with each other (low) 13. Likewise, family conformity can range from families with uniform beliefs and family values that emphasize family harmony (high) to families with little emphasis on obedience to parents/elders (low) 14.

Family conversation and conformity rules interact with each other to form a family communication pattern. Figure 1 illustrates how the two features can vary from high to low to reveal four different family types. Consensual families have high allegiance to family conformity and high family conversation. Families negotiate the tension between agreeing and preserving hierarchy within the family, yet still are able to freely explore new ideas 14. Protective families are low on family conversation and high on family conformity. These families rely heavily one parent as a hierarchical figure who determines and directs family communication 14.

Figure 1.

Overview of Family Communication Patterns

Pluralistic families are high in family conversation and low in family conformity. These families have open discussions that involve many or all family members, and parents are not necessarily situated as hierarchical figures within the family. Pluralistic families value participatory decision-making that includes multi-generational opinions 14. Finally, laissez-faire families are low in both family conversation and family conformity. This family type is characterized by very little interaction among family members and emotional detachment. Using FCPT as a framework, this study explored the ways in which family communication patterns influence caregiver concerns during hospice care.

Method

This study consists of secondary data analysis from a larger project that aims to demonstrate the feasibility of delivering a problem solving intervention called ADAPT (Attitude, Define, Alternatives, Predict, Try) to hospice caregivers 15,16. Hospice caregivers were randomly assigned to receive the problem solving intervention either face-to-face or via videophone. While the main goal of the parent study was to account for the impact of the intervention on caregiver outcomes across the two mediums, the project presented here explores audio-recorded discussions of the problem-solving intervention between hospice caregivers and interventionists in both face-to-face encounters and videophone calls. Data analyzed for this study consists of both control and intervention groups; differences between the two mediums were not explored as caregiver talk about concerns that involved family members was the focal point for the study.

The intervention is designed to help caregivers to be effective in solving problems pertaining to the caregiving experience by a) adopting a positive orientation to problem solving, (b) carefully identifying the facts associated with the problem, (c) exercising creativity in generating a list of alternative approaches to solving the problem, (d) predicting the consequences of each alternative and selecting the one most likely to be effective, and (e) implementing the selected alternative to solve the problem. A total of 138 caregivers were referred to the parent study, however eight caregivers chose not to participate and four caregivers were not eligible to participate (one was a paid/ professional caregiver rather than an informal one, and for three the patient had died prior to being contacted). Of the remaining 126 caregivers, 89 caregivers (71%) completed the full study protocol. The study was approved by the supporting university’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Data were collected from consenting hospice caregivers (as defined by the patient or family member who elected for hospice enrollment) in two urban hospice programs in the Northwestern U.S. Caregivers were receiving outpatient services from the participating hospice agencies. Caregivers enrolled in the study had to 1) be 18 years or older, 2) have access to a standard phone line, 3) be without functional hearing loss, no or only mild cognitive impairment, and 4) have at least a 6th grade education.

Procedure

Upon admission to hospice, caregivers were presented with the research opportunity by hospice staff. Contact information for eligible caregivers interested in learning more about the study was sent to the research coordinator. Between days 5 and 18 of the hospice admission, the research coordinator visited the caregiver and obtained informed consent. During this visit the researcher worked on steps one and two of the ADAPT model (“Attitude toward problem-solving” and “Defining the Problem and Setting Realistic Goals”) which was the discussion protocol for the larger parent study. Although caregivers received two more visits by the research coordinator to complete the delivery of the study intervention, only the initial visit with each caregiver was analyzed for this study.

To initiate a discussion about problems and concerns, caregivers were prompted by the researcher to prioritize common concerns using a checklist. Additionally, in order to individualize the intervention material, caregivers were allowed to define problems not included in the list. Interviews took place in the caregiver’s home, an off-site location at the request of the caregiver, or via videophone call as dictated by the larger study design. In three instances, other family members were present but did not contribute to the discussion. All interviews were conducted while the patient was still alive. Each interview was audio-recorded, ranging from 35 minutes to an hour and a half in duration, and serve as the corpus of data for this study.

Data Analysis

A grounded theory approach 17 was used to collectively review the data. The following steps were taken in this study: (1) constant comparison of caregiver talk about family in relation to family communication patterns theory 18 and (2) discussion and feedback among research team members representing varying disciplines where themes were discussed and adjusted according to this feedback. The analysis was conducted using a qualitative data analysis software package called Nvivo 8 which facilitated coding and management of the data.

First, two members of the research team listened to audio recorded intervention discussions together and used Nvivo to transcribe caregiver talk that included any mention of family. Nvivo software allows researchers to code audio and video data in segments and eliminates the need to capture transcriptions in their entirety. This allowed researchers to target caregiver responses about any family-related concerns. Second, members of the research team engaged in a series of individual readings of the transcripts using family communication features deduced from FCPT and coded caregiver talk into one of the following mutually exclusive codes: family hierarchy, preservation of family authority, minimal talk with family but with sustained contact, explicit talk of assumed family roles, reference to open discussion among family members, the absence of an authoritarian family member, little interaction among family, or emotional detachment from family.

Next, the coding features described above were grouped together by family communication patterns accordingly: family hierarchy and preservation of family authority (consensual family communication pattern); minimal talk with family but with sustained contact and explicit talk of assumed family roles (protective family communication pattern); reference to open discussion among family members and the absence of an authoritarian family member (pluralistic family communication pattern) and little interaction among family and emotional detachment from family (laissez-faire family communication pattern). In few instances team members coded a caregiver’s talk into two different family communication patterns. The team met to discuss variances and came to consensus using an iterative transcript reading and recording playback process.

Data grouped by family communication pattern was then thematically analyzed. This process consisted of recognizing recurrence of meaning and repetition of words/phrases. Individual readings by the research team produced notations, memos, and analytical notes. Researchers discussed individual analyses, leading to integration of analytical notes and memos. As a result of these discussions, the emergent themes deduced from the data, and from FCPT, the team established four caregiver types.

To confirm data saturation, we used the four newly established typologies to code the data set. The data proved representative of the typology (Manager, (21) 37.5%; Partner, (13) 23.2%; Carrier, (12) 21.4%; and Loner, (10) 17.8%) and no new themes emerged. Additionally, caregivers completed the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) tool as part of the larger parent study. The CRA is a 24-item multi-dimensional scale used to measure caregiver’s reactions to caregiving 19. The CRA includes 5 items that measure lack of family support using a 1–5 likert score (range 5–25). These items assess caregiver perceptions of caregiving responsibility, caregiving delivery, and how family members work together to achieve care of a loved one. A mean score for CRA items measuring lack of family support were computed and support the caregiver typology.

Finally, authenticity of data was accomplished through peer review of the data by members of the research team who have extensive experience with qualitative research methods, data triangulation with CRA scores, and the absence of negative cases or alternative explanations in the complete data set 20,21. Additionally, it is important to note that caregivers were free to discuss any problems related to caregiving and were not prompted specifically to discuss family issues.

Results

A total of 81 caregivers were included in this data analysis, however 25 caregivers did not have concerns related to family or discuss other family members and 6 caregivers became bereaved and were omitted from the study, resulting in a final sample of 56. The average time from hospice admission to study enrollment was 15 days. Demographics for both patients and caregivers are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 82 years whereas the mean age of caregivers was 61 years. The majority of caregivers and patients were female (87.2%, 57%). Caregiver relationship to the patient was predominantly adult children (48%) followed by spouse/partner of the patient (25%).

Table 1.

Summary Demographic Variables for Patients and Caregivers (n=56)

| Variable | Caregiver | Patient |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Not applicable | |

| Cancer | 25% (14) | |

| (Bladder, 2; Brain, Breast, Colon, Kidney, Melanoma, Ovarian, 4; Lung, Not specified, 2) | 7% (4) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 23% (13) | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 5% (3) | |

| COPD | 4% (2) | |

| CVA | 9% (5) | |

| Debility | 9% (5) | |

| Dementia | 9% (5) | |

| Parkinson’s | 5% (3) | |

| Other (ALS, MS, Renal failure) | 4% (2) | |

| Unknown | ||

| Mean Age | 61 years (range 33–96) | 82 years (range 45–104) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 87.5% (49) | 57% (32) |

| Male | 12.5% (7) | 43% (24) |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 96.4% (54) | 96.4% (54) |

| Black/African-American | 1.7% (1) | 1.7% (1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1.7% (1) | 1.7% (1) |

| Marital Status | Not captured | |

| Married/Partner | 73% (41) | |

| Widowed | 12.5% (7) | |

| Divorced | 11% (6) | |

| Never Married | 1.7% (1) | |

| Unknown | 1.7% (1) | |

| Education | ||

| High school | 23% (13) | |

| Some college | 17.8% (10) | |

| 2 year college degree | 26.7% (15) | |

| 4 year college degree | 14.2% (8) | |

| Master’s degree | 16% (9) | |

| Doctoral degree | 1.7% (1) | |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse/partner | 25% (14) | |

| Adult child | 48% (27) | |

| Sibling | 7% (4) | |

| Other | 11% (6) | |

| Unknown | 9% (5) | |

| Resides with patient | ||

| Yes | 45% (25) | |

| No | 46% (26) | |

| Unknown | 9% (5) |

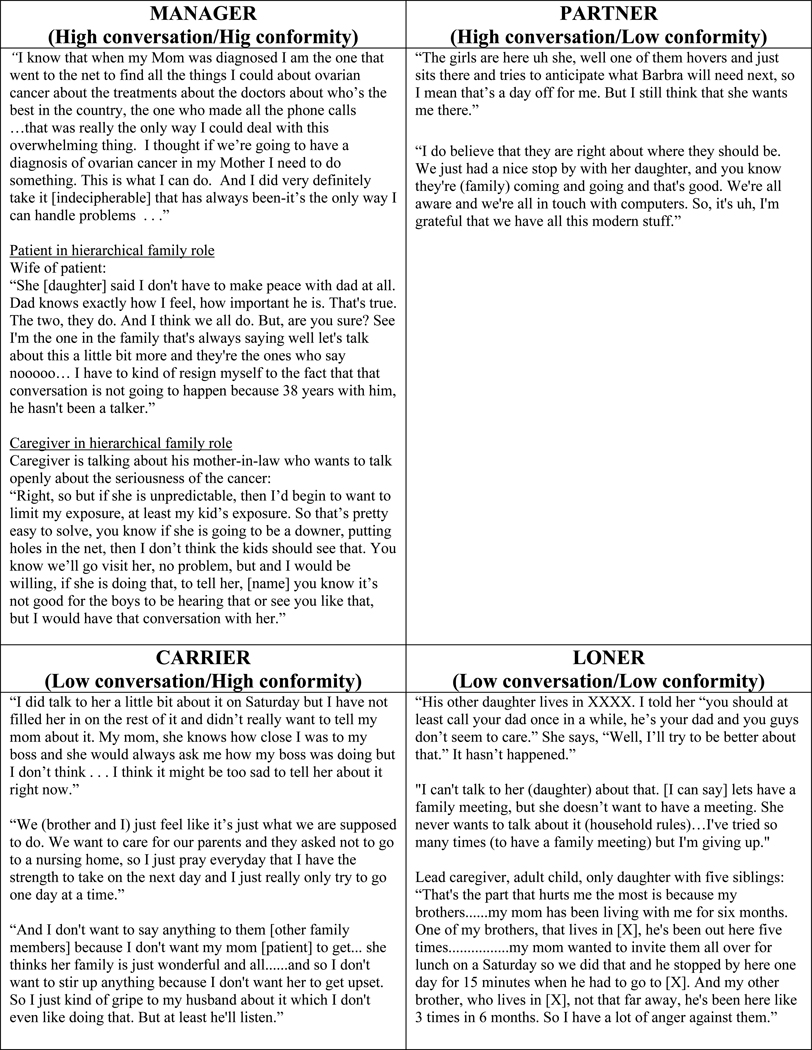

Findings demonstrate that caregivers emphasize family conformity by adhering to family rules dictated by a hierarchical family member (patient or caregiver) rather than engaging in open family conversation. Contrary to previous research examining family coping and illness, family conformity did not equate with family agreement. Caregiver talk revealed burden resulting from family communication patterns, advancing a typology for the ways caregivers experience caregiving responsibility within their family setting. Namely, Manager, Carrier, Partner, and Loner caregiver types emerged as a result of the burden produced by family communication patterns. Each of these caregiver types are described below and illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of Family Caregiver Types with illustrative quotations from the data

Manager

Although the Manager Caregiver comes from a family that emphasizes family conversation and family conformity, one family member (either the patient or caregiver) emerges as the dominant family figure that dictates communication patterns during hospice care. Patients who historically made family decisions were actively demonstrative in their care planning choices, leaving caregivers with the main task of carrying out requests and wishes. In these instances, caregivers reported feeling compelled to adhere to family communication norms by following patient directives. With the emphasis on family structure and hierarchy, open and participatory family conversation was superseded by emphasis on family obligation to provide care within the structures of existing hierarchy (conformity).

Caregivers who held a hierarchical role within the family felt obligated to fulfill their traditional family role. While they might have been interested in talking about care planning, they prioritized already established family communication patterns. As a result, the caregiver’s need to communicate was diminished by their and the patient’s hierarchical roles and the preservation of existing patterns. Burden was also present for caregivers who worked to provide patient care and simultaneously assume the additional family role vacated by the patient. Several caregivers talked about the added stress of carrying on family functions while attending to urgent care situations for the patient, in addition to routine caregiving tasks. One caregiver explained:

I think maybe it was the day she was trying to get her own diaper –she tried to change her own diaper one night in the middle of the night and I was like “don’t help me like that Mom. That’s not helping me.” So I don’t even remember what it was but I do remember feeling kind of stunned that my impatience had seeped out into my voice and she could hear it.

Assuming the additional family role held by her mother added to the daily stress and exhaustion of this daughter caregiver.

Serving in the role as self-appointed family spokesperson, these caregivers discussed decision-making as their sole responsibility with little input encouraged from other family members. Although varying viewpoints were acknowledged from other family members, these caregivers reported little need for and minimal application of this information. Decision-making was decisive and disallowed open family communication. Ultimately, the Manager Caregiver is positioned to make the majority of care planning choices for the patient.

Carrier

Families with low family conversation and high family conformity characterize the protective family communication pattern that gives rise to the Carrier Caregiver. With an emphasis on parental authority, these caregivers absorb multitudinous caregiver burdens for the patient and the family, despite the potential ability of the family members to share in care responsibilities. This caregiver over functions to perform their role in the family structure to minimize illness impact on the patient as well as other individuals in the family.

The Carrier communicates with the patient in a limited way, often suppressing difficult/decision-making discussions with the patient. Given the emphasis on family conformity over family conversation, the Carrier is most likely to acquiecence to other family members during decision-making and care planning. As a result, low conversation and high conformity creates frustration about illness. Acceptance of illness and treatment choices can be confounding because of limited talk, but the pressure to conform to the caregiver/patient action drives the family/caregiver communication pattern. Because the family does not present an open environment to share perspectives, the caregiver goes outside the family to process their burden or find relief. Caregiver disclosure occurs with friends, support groups, health care professionals, and others beyond the bounds of family. In addition, information-seeking and suppression is a common coping mechanism for this caregiver type. Commonly, the Carrier attempts to accomplish all care planning duties, treating the illness as private and personal for the sick family member—insulating the rest of the family from their changing reality.

Burdens of the Carrier type reflect her or his efforts to follow directions from the patient and/or maintain preexisting family roles, despite a system that is shifting uncontrollably due to illness. This caregiver is dependent on practitioner intervention to faciliate patient requests, and serves as a reinforcer of patient agenda. The Carrier’s burden results from prioritizing family harmony and stasis above their own needs and role demands, as well as internalizing unresolved difficulties that develop into a ‘piling on’ pattern.

A young woman providing care for her mother describes the strained relationship she has with her father:

My father is very angry, again very, very, angry. He screamed and yelled at me last night. It’s just awful . . . . I’ve been his whipping post . . . since the day that I can remember . . . . I got her ready for bed, tucked her in, and he [is] sitting down watching [TV] and I’m thinking to myself at nine thirty “ok, so how are you going to get from here to there without another attack” and I went down and I told dad I said to him “um, mom’s all ready for bed and she’d like you to lay down and go to bed too.” And then I went in my room and shut the door until he was gone.

In the midst of caregiving and facing the death of her mother, this Carrier endures additional burden in the form of long-standing hostility from her father. She suppresses any confrontation or direct address about his hurtful behavior; the patient becomes the focal point of her energy and she suppresses her emotional labor..

Partner

Families experiencing high conversation and low conformity embody a pluralistic communication pattern. These families allow all family members to equally share in decision-making and care decisions are made in a manner that supports the lead caregiver’s goals. Absent in these families is the preservation of hierarchy at all costs, or creating a refuge of denial for certain members of the family.

In many instances, advance care planning is either in process or in place for the Partner Caregiver. Open family challenges might include appropriate ways of caring, places of caring, and distribution of the cascading burdens across the family system. The Partner Caregiver experiences open communication with the patient, inclusive of conflict. The caregiver’s burdens are part of the illness scene, instead of challenges pressed quietly into the figurative closet---to either be ignored, routed out with a health care professional, or outsourced to friends. The following exemplar showcases this inclusion of self, family members, and patient on the part of a daughter describing communication with her dying father:

So my brother and I had a little mini meeting today and said we are going to have to give him [father] the message that we understand he is bored, he wants his own food and he still thinks he can still try to go to the bathroom and he’s fighting that whole thing and he wants us to take care of him . . . I heard my Mom say to him yesterday when my brother and I were out of the room when we took her to visit, I heard her say “the kids are in charge now honey and they are doing the best they can for us.”

As this family struggles with their father’s transition into dying, they are actively taking on various aspects of burden with the Partner Caregiver. Conflict is still present, but the members of this family pool resources as they face caregiving costs.

The pattern of including family voices gives rise to family-prompted internal meetings for the Partner. As a result, this caregiver has the potential to experience immediate and extended family support in their caregiving efforts through relief and conversation. There is also potential for an overall supportive environment for this caregiver. The choices of care for the patient are not managed alone.

Loner

For families who demonstrate low conversation and low conformity, there is little support or assistance for the lead caregiver who is most often alone in his or her efforts, decision-making, and burden. The laissez-faire dynamic of this family communication pattern gives rise to the Loner Caregiver. Family members of the Loner are primarily absent in their commitment to the larger family system, employing noninterference/noninvolvement in an illness context. The Loner is an independent constellation among other familiar constellations.

For these caregivers, illness does not impact previously established family dynamics. The Loner is not positioned to rely on other family members, confide in them, ask them for assistance, or reliably expect support from any branch of their family. An adult child caregiver, one of six children in the family, reflects on the lack of participation from her siblings: “That’s really where I get a lot of anger and resentment is towards my own brothers, not my mom [patient]. That’s been hard for me. I just feel like they’ve abandoned her and me. Both of us.” This caregiver moved her mother into her home so that she could provide care and reported that her siblings rarely visited, leaving her own husband to assume caregiving tasks. The participant also noted that this was the established trend in the family before her mother’s terminal diagnosis.

The Loner is solitary in his or her immense burden of patient caregiving. They are at high risk for caregiver suffering, low health literacy, and health problems. The Loner has limited choices as the solo-provider, recognizes the absence of other family members in the illness process, but does not expect or intiate a different outcome based on long-standing patterns of communication. Deep-rooted anger, resentment, depression, abandonment, and helplessness are particular characteristics of suffering for this caregiver type.

Finally, CRA scores for the data support provide support for the typology. With high CRA scores representing a lack of family support (score of 25) and conversely low CRA scores indicating strong family support (score of 5), we correlated the following mean scores from the study sample: Manager, 11; Partner, 7; Carrier, 11; and Loner, 14.

Discussion

The data presented in this article suggest that hospice family caregivers experience burden common with one of four caregiver types: the Manager, the Carrier, the Partner, and the Loner. Although family members defer to the hierarchical role within the family (conformity) over communication (conversation), Partner caregivers experience shared decision-making facilitated through family communication. Overall findings in this study demonstrate that conformity in family communication does not equate with family agreement or open communication. Manager, Carrier, and Loner caregiver types emerged from family communication that emphasized family hierarchical roles rather than conversation and disclosure.

The scope of this study examines the caregivers of terminal patients only, and the expansion of this analysis to include caregivers of patients with chronic illness might yield different results. The predetermined theoretical framework provided conceptual clearness and methodological rigor to the study design, especially given that members of the research team comprised three different disciplines 22. This was especially salient given the nature of hospice and palliative care research where there is less opportunity to apply theoretical sampling 22. Still, it should be noted that the use of a theoretical framework in qualitative research design influences the researcher’s interpretation of the data as it provides plausible relationships among sets of concepts 22. Moreover, the use of secondary data from a larger study limits findings as the research protocol was not designed to achieve this study’s goals 22. Future research should expand our knowledge of family communication patterns by interviewing several family members from within one family rather than just one family member’s perspective. Although the study sample represented patient and family demographics consistent with national statistics of hospice use, more diversity is needed for this study population 23.

Despite these limitations the caregiver typology categories presented here support the findings of similar research on family caregivers, specifically, those examining the impact of a terminal diagnosis and its effect on the entire family system 24. Our results are also consonant with scholarship identifying family communication styles/history of family relationships 25 and how both are impacted by a terminal diagnosis.

Although no studies to date have identified family communication patterns and subsequently a caregiver communication typology in the terminal illness context, communication has been considered instrumental in establishing and promoting quality of life among caregivers26. Caring for a patient with terminal illness has profound significance on a family caregiver’s quality of life. Results from this research indicate one cause for the variance among caregiver quality of life is family communication patterns and communication roles for lead caregivers.

In consonance with our data, a terminal diagnosis and consequently hospice care intractably transfigures the entire family system, not just the patient 24. Given the active role family caregivers play in treatment decision-making, caregiver communication is pivotal in navigating choices and places of care. Family caregiving becomes increasingly more important in the navigation and assurance of patient-centered care; the family caregiver is often the primary patient advocate 24. Communication patterns within and among family members vary and are often based on perceptions of family norms 1. A family that values open family communication can enable a caregiver to more easily assume their role as collaborator with the healthcare team 1. Our findings suggest that caregivers identified as Carriers and Loners most commonly need the intervention of a third party to facilitate their family communication needs.

Implications for Clinicians

This article highlights the exigency for better clinician communication preparation and education about caregiver communication needs. Family functioning varies and interventions have not yet taken this into account 27. Though family “conflict” has been a long-standing awareness of health care professionals, evidence-based analyses providing reliable and useful information to facilitate the provision of good care are still limited.

Communication preparation for clinicians is relatively new, and caregiver communication training is practically non-existent 27. Comprehensive palliative care is needed for family caregivers, especially during hospice care – for both enhancing clinician communication with patients/caregivers as well as the development of quality interventions to support the caregiver. Given the intimate communicative role of family caregivers of terminally ill patients, a relational approach with caregivers has been recommended in order to ensure shared decision-making between clinicians and patients 24. The family caregiver is the lead collaborator with a healthcare team; as such, developing interventions that will enable successful communication with that caregiver and family are imperative.

One way nurse clinicians can initiate collaboration with family caregivers is to first observe what patterns might identify the caregiver as one of the four caregiver types (manager, carrier, partner, loner). Specific family communication practices such as (1) the use of supportive messages between family members, (2) blocked communication between family members such as refusing to talk to each other or agreeing not to talk about the illness, (3) self-censored speech resulting from a family member’s fear of causing anxiety in the patient or other family members, and/or (4) the use of third parties (typically in-law relationships within the family) to mediate family relationships can indicate specific types of family communication 1.

Nurse clinicians can also assess patients and family members for information about their family communication pattern. Some key questions that can be asked include: (a) tell me about your family; (b) who is close to who?; (c) what else is going on in your family’s life?; (d) what has helped your family deal with these stressors?; and (e) what hasn’t been helpful? 28. Information about the family can help to identify specific caregiver types and prioritize caregiver needs. For example, Manager caregiver types have a need to obtain control and fulfill a hierarchical family role. When working with these caregiver types, clinicians should emphasize clinician-involved family meetings, assistance in legal documentation, and inquires about caregiver burden (especially for caregivers caring for a hierarchical family member). In contrast, Carrier and Loner caregiver types have a high need for psychosocial support and need additional resources to aid in coping. In these instances, nurses should involve psychosocial professionals in the plan of care. Clinician assessment and awareness of family communication will aid in the development of tailored interventions that extend the patient’s plan of care to include the family caregiver.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the NIH National Institute of Nursing Research Grant Nr. R21 NR010744-01 (A Technology Enhanced Nursing Intervention for Hospice Caregivers, Demiris PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles, Markey Cancer Center, Department of Communication, University of Kentucky, 741 S. Limestone Street, B357 BBSRB, Lexington KY 40506, Elaine.lyles@uky.edu, Phone: 940-322-4118.

Joy Goldsmith, Department of Communication Studies, Young Harris College, Young Harris, Georgia.

George Demiris, Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems, School of Nursing & Biomedical and Health Informatics, School of Medicine, University of Washington, BNHS-Box 357266, Seattle, WA 98195-7266.

Debra Parker Oliver, Curtis W. and Ann H. Long Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia.

Jacob Stone, Miami University, Department of Environmental Science, Oxford, OH.

References

- 1.Kenen R, Arden-Jones A, Eeles R. We are talking, but are they listening? Communication patterns in families with a history of breast/ovarian cancer (HBOC) Psychooncology. 2004 May;13(5):335–345. doi: 10.1002/pon.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachner YG, O'Rourke N, Davidov E, Carmel S. Mortality communication as a predictor of psychological distress among family caregivers of home hospice and hospital inpatients with terminal cancer. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13(1):54–63. doi: 10.1080/13607860802154473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker M. Facilitating forgiveness and peaceful closure: the therapeutic value of psychosocial intervention in end-of-life care. Journal Of Social Work In End-Of-Life & Palliative Care. 2005;1(4):83–95. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syren SM, Saveman BI, Benzein EG. Being a family in the midst of living and dying. J Palliat Care. 2006 Spring;22(1):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Planalp S, Trost MR. Communication issues at the end of life: reports from hospice volunteers. Health Commun. 2008;23(3):222–233. doi: 10.1080/10410230802055331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pruchno RA, Burant CJ, Peters ND. Typologies of caregiving families: family congruence and individual well-being. Gerontologist. 1997 Apr;37(2):157–167. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, Walsh M, Yonker JA. Predictors of family conflict at the end of life: the experience of spouses and adult children of persons with lung cancer. Gerontologist. Apr;50(2):215–225. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns theory: A social cognitive approach. In: Braithwaite D, Baxter L, editors. Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006. pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris J, Bowen DJ, Badr H, Hannon P, Hay J, Regan Sterba K. Family communication during the cancer experience. J Health Commun. 2009;14 Suppl 1:76–84. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchie L, Fitzpatrick MA. Family communication patterns: Measuring interpersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Communication Research. 1990;17:523–544. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick MA, Ritchie L. Communication schemata within the family: Multiple perspectives on family interaction. Human Communication Research. 1994;20:275–301. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLeod J, Chaffee S. Interpersonal approaches to communication research. American Behavioral Scientist. 1973;16:469–499. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick MA. Family Communication Patterns Theory: Observations on Its Development and Application. Journal of Family Communication. 2004;4(3/4):167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Toward a Theory of Family Communication. Communication Theory (10503293) 2002;12(1):70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K. Use of videophones to deliver a cognitive-behavioural therapy to hospice caregivers. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(3):142–145. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demiris G, Parker Oliver D, Washington K, et al. A Problem Solving Intervention for hospice caregivers: a pilot study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(8):1005–1011. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser B, Strauss A. Awareness of Dying. San Francisco: Aldine; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coffey A, Atkinson P. Making sense of qualitative data analysis: complementary strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, Franklin S. The Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Research in Nursing & Health. 1992 Aug;15(4):271–283. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (3rd ed) Sussex, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiel S, Pestinger M, Moser A, et al. The use of Grounded theory in palliative care: methodological challenges and strategies. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010 Aug;13(8):997–1003. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stiel S, Pestinger M, Moser A, et al. The use of Grounded theory in palliative care: methodological challenges and strategies. J Palliat Med. 2010 Aug;13(8):997–1003. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. 2010 http://www.nhpco.org. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubbard G, Illingworth N, Rowa-Dewar N, Forbat L, Kearney N. Treatment decision-making in cancer care: the role of the carer. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:2023–2031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay J, Shuk E, Zapolska J, et al. Family communication patterns after melanoma diagnosis. Journal of Family Communication. 2009;9(4):209–232. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamayo GJ, Broxson A, Munsell M, Cohen MZ. Caring for the caregiver. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010 Jan;37(1):E50–E57. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E50-E57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson P, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med. 2004 Feb;7(1):19–25. doi: 10.1089/109662104322737214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapp ER, DelCampo RL. Developing family care plans: a systems perspective for helping hospice families. The American Journal Of Hospice & Palliative Care. 1995 Nov–Dec;12(6):39–47. doi: 10.1177/104990919501200608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]