Abstract

Background

Marek's disease (MD) is a lymphoproliferative disease in chickens caused by Marek's disease virus (MDV) and characterized by T cell lymphoma and infiltration of lymphoid cells into various organs such as liver, spleen, peripheral nerves and muscle. Resistance to MD and disease risk have long been thought to be influenced both by genetic and environmental factors, the combination of which contributes to the observed outcome in an individual. We hypothesize that after MDV infection, genes related to MD-resistance or -susceptibility may exhibit different trends in transcriptional activity in chicken lines having a varying degree of resistance to MD.

Results

In order to study the mechanisms of resistance and susceptibility to MD, we performed genome-wide temporal expression analysis in spleen tissues from MD-resistant line 63, susceptible line 72 and recombinant congenic strain M (RCS-M) that has a phenotype intermediate between lines 63 and 72 after MDV infection. Three time points of the MDV life cycle in chicken were selected for study: 5 days post infection (dpi), 10dpi and 21dpi, representing the early cytolytic, latent and late cytolytic stages, respectively. We observed similar gene expression profiles at the three time points in line 63 and RCS-M chickens that are both different from line 72. Pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) showed that MDV can broadly influence the chickens irrespective of whether they are resistant or susceptible to MD. However, some pathways like cardiac arrhythmia and cardiovascular disease were found to be affected only in line 72; while some networks related to cell-mediated immune response and antigen presentation were enriched only in line 63 and RCS-M. We identified 78 and 30 candidate genes associated with MD resistance, at 10 and 21dpi respectively, by considering genes having the same trend of expression change after MDV infection in lines 63 and RCS-M. On the other hand, by considering genes with the same trend of expression change after MDV infection in lines 72 and RCS-M, we identified 78 and 43 genes at 10 and 21dpi, respectively, which may be associated with MD-susceptibility.

Conclusions

By testing temporal transcriptome changes using three representative chicken lines with different resistance to MD, we identified 108 candidate genes for MD-resistance and 121 candidate genes for MD-susceptibility over the three time points. Genes included in our resistance or susceptibility genes lists that are also involved in more than 5 biofunctions, such as CD8α, IL8, USP18, and CTLA4, are considered to be important genes involved in MD-resistance or -susceptibility. We were also able to identify several biofunctions related with immune response that we believe play an important role in MD-resistance.

Background

MD is a serious lymphoproliferative disease in chickens caused by MDV and characterized by transformation of T cells that cause tumors in various organs including liver, spleen, gonads, heart, peripheral nerves, skin and muscle [1-3]. Chickens with MD exhibit over-expression of Hodgkin's disease antigen CD30 (CD30hi) that makes it a natural model for studying the initiation and progression of CD30hi lymphomas [4]. MDV is an alphaherpesvirus belonging to the Mardivirus genus which contains three members: MDV-1, MDV-2 and HVT (herpesvirus of turkeys) [5-7]. According to Calnek et al. [8,9], MDV, like other herpesviruses, goes through a complex life cycle that includes cytolytic and latent phases in host cells. An early cytolytic infection is started at 2-7dpi characterized by the virus particles expressing large amounts of the early protein pp38. Subsequently, a latent phase is initiated at around 7-10dpi with the MDV genome persisting in the host cells. Following latency, a late cytolytic phase causes inflammation and transformation of latently infected lymphocytes into tumor cells and is triggered between 14-21dpi [8,9]. During the first cytolytic phase, MDV first uses B cells as a target for its replication before targeting activated CD4+ T cells to enable a persistent latent infection [10-12].

Two highly inbred chicken lines 63 and 72, sub-lines of lines 6 and 7, have been bred since 1939 with line 63 chickens resistant to MD and line 72 chickens susceptible to MD [13]. To better understand the mechanisms underlying MD-resistance and -susceptibility, several studies have been made to ascertain the differences between these two chicken lines. A much higher virus copy number was observed in line 7 chickens indicating varying levels of virus replication [14]. Different proportions of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were found in MD-resistant and -susceptible chickens when infected by MDV. In MD-susceptible birds, as the CD4+ T cells increased in number, the number of CD8+ T cells decreased; the opposite occurred in MD-resistant chickens [15]. Lymphocyte surface markers such as Ly-4, Bu-1 and Th-1, were present in different levels in these two chicken lines [16,17]. The expression of some cytokines, such as IL6 and IL18, was also found to differ between line 6 and line 7 chickens[18]. From an epigenetic perspective, differences in promoter DNA methylation levels between line 63 and line 72 chickens have been found in several candidate genes [19].

With the development of functional genomics technologies, some progress has been made towards investigating the mechanism of MD-resistance in a genome-wide manner. Quantitative trait loci associated with MD-resistance or -susceptibility have been mapped to chromosomes 1, 5, 7, 9, 15, 18, 26, Z, E21 and E16 [20-23]. Also, through the use of chicken immune-specific microarrays, immunoglobulin genes have been shown to have a higher expression in MD-resistant chicken lines as compared to MD-susceptible chicken lines [24]. However, the exact mechanisms behind resistance and susceptibility to MD are still unknown.

Researchers at the Avian Disease and Oncology Laboratory (ADOL, East Lansing, MI, USA) have developed nineteen recombinant congenic strains (RCS) with varying phenotypic traits from lines 63 and 72 to further investigate the mechanisms of MD-resistance and - susceptibility [13,25]. One of these strains, RCS-M, which was developed from line 63 and line 72 and possesses around 87% genetic background of line 63, is genetically closer to the resistant line 63. Our previous study of tumor incidence rates induced by a partially attenuated very virulent plus (vv+) strain of MDV (648A, passage 40) in the different RCSs revealed that while only 0-3% of line 63 chickens and up to 100% of the line 72 chickens developed tumors after MDV infection, about 40% of RCS-M chickens developed tumors (Data not shown). Because of this intermediate response of RCS-M to MDV infection, it is suitable for us to use these three chicken lines to investigate the mechanism of MD-resistance and susceptibility. We performed a temporal trancriptome analysis with spleen samples from line 63, 72 and RCS-M chickens before and after MDV infection at 5dpi, 10dpi and 21dpi. Our main objective is to build on the current understanding of Marek's disease pathogenesis and immune response to MDV, and this genome-wide approach is used for this purpose. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study combining a chicken line having intermediate resistance to MD together with highly-resistant and susceptible lines to more precisely identify the possible genetic factors behind MD resistance and susceptibility.

Results

Temporal Gene Expression Profiles of line 63, line 72 and line M chickens in MDV Challenge Experiment

To find genes that may be involved in the MD-resistance and -susceptibility, we performed transcriptome analysis using three chicken lines with different phenotypes after MDV infection to find the host genes with different reactions to virus infection. We chose 5dpi, 10dpi and 21dpi to represent the critical phases of virus progression to study gene expression changes induced in the different chicken lines.

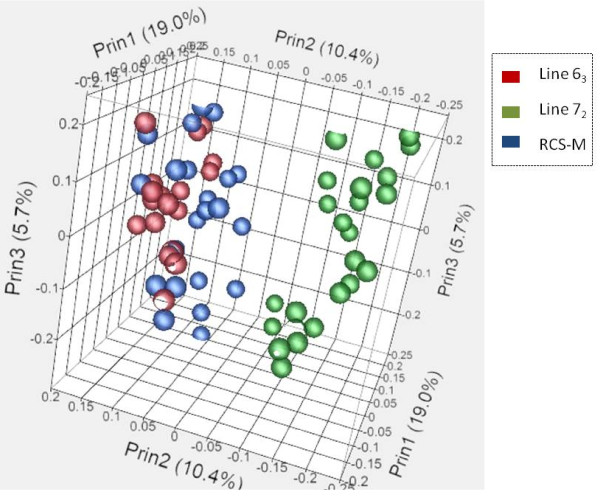

We conducted an initial quality assessment of our dataset to remove outliers (see Methods). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to compare the global gene expression profiles of these three chicken lines. The preliminary PCA plot indicated broad differences between the three chicken lines with lines 63 and RCS-M clustering together and distinct from line 72 chickens (Figure 1). Data normalization and differential gene expression analysis was performed using the limma package in R (for details see Methods). In order to minimize transcriptional variations owing to growth and other developmental differences between the three chicken lines, individuals were paired by line and dpi and comparisons carried out between infected and non-infected individuals. The p-values were then corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR calculation procedure [26]. To detect the host response to MDV infection, we compared the gene expression level of the infected samples to non-infected control samples at the same time point. Differentially expressed gene lists were obtained using a criteria of P < 0.05, FDR < 0.5 and |logFC| > 1.5.

Figure 1.

A three-dimensional PCA plot of 64 individuals indicating broad transcriptional similarities between line 63 and RCS-M that are both markedly distinct from line 72.

Our significant gene lists consisted of a total of 11779 genes in the three chicken lines across three time points that included some virus genes contained in the microarray (Additional file 1. Table S1). As our focus was on the host response to MDV infection, we excluded the MDV genes from further analysis reducing our total gene number to 11694 (Table 1). Notably, no gene was found differentially expressed in line 72 at 5dpi using the above criteria. However, when validating the microarray results with qPCR, we found several genes significantly changed by MDV infection in line 72 at 5dpi (Additional file 2. Figure S1).

Table 1.

Number of genes differentially expressed after MDV infection

| line 63 (Inf. Vs. Non.) | line 72 (Inf. Vs. Non.) | RCS-M (Inf. Vs. Non.) | ||||

| + | - | + | - | + | - | |

| 5dpi | 777 | 651 | 0 | 0 | 707 | 680 |

| 10dpi | 708 | 660 | 823 | 691 | 791 | 572 |

| 21dpi | 573 | 585 | 1007 | 1088 | 567 | 814 |

Genes with differential expression were termed with P < 0.05, |LogFC|>1.5 and FDR < 0.5. +: up-regulated after MDV infection; -: down-regulated after MDV infection.

Pathway analysis to find the networks and biofunctions involved in MDV infection

To study the networks and biofunctions enriched in the differentially expressed genes after MDV infection, we used the IPA system to analyze genes sets. We first used the raw probe names from the microarray as the input data set and found less than 25% of the probes were compatible with IPA. Therefore, we used data mining to map the probe names to homologs from other species that could be used by IPA (for details see Methods). The mapped homologs of these ESTs are shown in Additional file 3. Table S2.

Detailed analyses of the networks and biofunctions affected by MDV in the different chicken lines across different time points were performed to understand the host responses to MDV infection. The top 5 networks influenced by MDV infection in each chicken line at three time points are shown in Table 2. From these networks we can see that during various stages of the MDV life cycle (5dpi, 10dpi and 21dpi), the virus has a broad influence on host gene expression in all chicken lines. A large number of genes involved in metabolism, tissue development, gene expression and the cell cycle were changed by MDV infection in all chicken lines which indicated broad similarities in the host response to MDV infection. However, we also found some unique networks among these chicken lines, such as, cardiac arrhythmia and cardiovascular disease related networks found only in line 72. On the other hand, some immune-related networks such as cell-mediated immune response and antigen presentation were only found in line 63 and RCS-M but not in line 72. These are the specific responses to MDV infection which may be related to the genetic basis of MD-resistance and -susceptibility.

Table 2.

Enriched networks at different time points of MDV infection in different chicken lines

| Lines | Time points |

Score | Focus Molecules |

Top Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L63 | 5dpi | 46 | 29 | Digestive System Development and Function, Hepatic System Development and Function, Organ Development |

| 36 | 25 | Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function, Tissue Morphology, Lipid Metabolism |

||

| 35 | 25 | Amino Acid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Cellular Compromise |

||

| 28 | 21 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Lipid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

||

| 24 | 20 | Drug Metabolism, Endocrine System Development and Function, Lipid Metabolism |

||

| 10dpi | 36 | 25 | Lipid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Vitamin and Mineral Metabolism |

|

| 30 | 21 | Infection Mechanism, Visual System Development and Function, Dermatological Diseases and Conditions |

||

| 30 | 21 | Molecular Transport, Cellular Movement, Cell Cycle | ||

| 27 | 22 | Neurological Disease, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Lipid Metabolism | ||

| 26 | 19 | Organismal Injury and Abnormalities, Infection Mechanism, Infectious Disease |

||

| 21dpi | 39 | 28 | Cell Morphology, Cellular Function and Maintenance, Cell Death | |

| 34 | 22 | Cardiovascular System Development and Function, Organismal Development, Tissue Development |

||

| 27 | 19 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Cellular Assembly and Organization |

||

| 24 | 17 | Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cell-mediated Immune Response, Cellular Development |

||

| 22 | 16 | Lipid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Behavior | ||

| L72 | 10dpi | 29 | 21 | Cardiac Arrythmia, Cardiovascular Disease, Genetic Disorder |

| 27 | 22 | Cellular Assembly and Organization, Cellular Compromise, Free Radical Scavenging |

||

| 26 | 19 | Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function |

||

| 24 | 18 | Cell Morphology, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function |

||

| 22 | 17 | Infection Mechanism, Cardiovascular System Development and Function, Organismal Development |

||

| 21dpi | 38 | 27 | Cell Morphology, Connective Tissue Development and Function, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function |

|

| 32 | 24 | Lipid Metabolism, Molecular Transport, Small Molecule Biochemistry | ||

| 31 | 24 | Embryonic Development, Tissue Development, Cell Cycle | ||

| 31 | 24 | Cell Morphology, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function, Connective Tissue Development and Function |

||

| 23 | 20 | Connective Tissue Disorders, Genetic Disorder, Cellular Assembly and Organization |

||

| RCS- M | 5dpi | 32 | 22 | Cell Morphology, Cellular Development, Cell Death |

| 32 | 22 | Cellular Assembly and Organization, Cell Morphology, Cellular Development |

||

| 30 | 21 | Cell Morphology, Cellular Development, Skeletal and Muscular System | ||

| Development and Function | ||||

| 28 | 20 | Amino Acid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Drug Metabolism |

||

| 24 | 18 | Inflammatory Disease, Renal and Urological Disease, Amino Acid Metabolism |

||

| 10dpi | 34 | 23 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Lipid Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

|

| 31 | 21 | Antigen Presentation, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Function and Maintenance |

||

| 29 | 20 | Molecular Transport, Drug Metabolism, Lipid Metabolism | ||

| 21 | 16 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Drug Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry |

||

| 20 | 16 | Dermatological Diseases and Conditions, Genetic Disorder, Immunological Disease |

||

| 21dpi | 33 | 23 | Cell Morphology, Cellular Assembly and Organization, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction |

|

| 26 | 19 | Connective Tissue Development and Function, Skeletal and Muscular System Development and Function, Tissue Morphology |

||

| 24 | 18 | Carbohydrate Metabolism, Small Molecule Biochemistry, Organismal Functions |

||

| 24 | 23 | Cell Death, Gene Expression, Cellular Function and Maintenance | ||

| 23 | 18 | Lipid Metabolism, Molecular Transport, Small Molecule Biochemistry | ||

*The genes input in IPA software were obtained using P < 0.05, |LogFC|>1.5 and FDR<0.5.

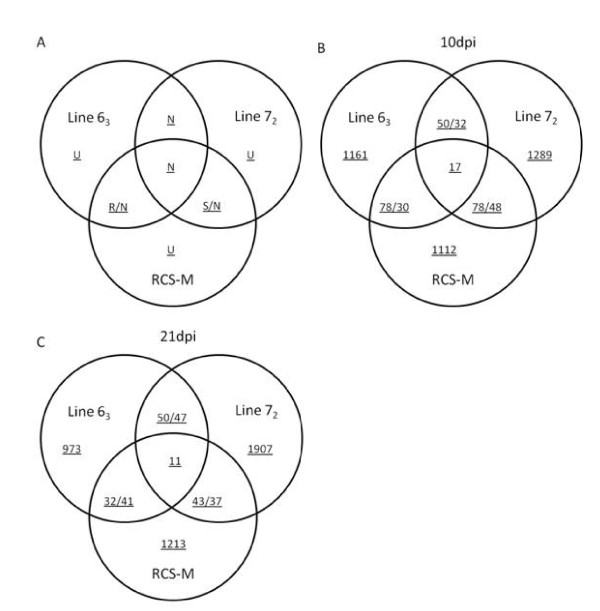

Identification of genes related with MD-resistance and -susceptibility

Utilizing the varying characteristics of these chicken lines, we attempted to identify genes associated with MD-resistance and -susceptibility from pair-wise comparisons. We make the following observations about differentially expressed genes obtained from our analysis. Genes differentially expressed after MDV infection and having similar trends in line 63 and RCS-M but not in line 72 are likely to be related to MD-resistance; conversely, genes showing similar trends in line 72 and RCS-M but not in line 63 are possibly related to MD-susceptibility (Figure 2A). Genes differentially expressed after MDV infection in all three chicken lines are likely indicators of a common host response to virus infection. Finally, genes that are differentially expressed only in one chicken line could be part of a line-specific host response to virus infection (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of the differentially expressed genes after MDV infection in different chicken lines at three time points showing the number of genes that are related to MD-resistance and -susceptibility. A. Schema showing the gene sets related to MD-resistance and-susceptibility. R: genes related to MD-resistance; S: genes related to MD-susceptibility; U: line specific genes; N: genes with no definition. B. 10 days post infection. C. 21 days post infection. Line 63.non: non-infected control of line 63 chickens; Line 63.inf: infected line 63 chickens; Line 72.non: non-infected control of line 72 chickens; Line 72.inf: infected line 72 chickens; RCS-M.non: non-infected control of RCS-M; RCS M.inf: infected RCS-M chicken.

From the above intuition, we were able to narrow the list of putative genes contributing to resistance (resistant genes) to 78 and 30 and the number of genes possibly associated with susceptibility (susceptible genes) to 78 and 43 at 10dpi, 21dpi respectively (Figure 2B-D). For some of the putative resistant genes, the fold change after MDV infection in RCS-M is about half or less compared to line 63 suggesting an additive effect of these genes in resistance (Additional file 4. Table S3). We can also find several genes that show a similar behaviour in the susceptible gene lists (Additional file 4. Table S3). This is consistent with the intermediate tumor incidence rates we observed in RCS-M chickens.

Although we were able to limit the number of putative resistant and susceptible genes, it is still a difficult task to determine the most important genes. By further analysing the networks associated with these genes, we found several genes involved in a large number of biofunctions (Additional file 5. Table S4). This indicated the importance of these genes to MD resistance or susceptibility even though they may not have very high fold changes. We defined high-confidence genes as those involved in more than 5 biofunctions to obtain high-confidence gene lists important for MD-resistance or -susceptibility (Table 3). The differentially expressed genes at the various time points were different indicating different mechanisms involved in the host response. At 10 dpi several interleukin genes were present among the putative susceptible genes such as IL8, IL17A and IL12RB2. The NOS2 gene, which can catalyze the generation of NO (nitric oxide), was also found in the putative MD-susceptible gene list.

Table 3.

Genes from MD-resistant and -susceptible gene lists enriched in more than 5 biofunctions

| T.Point | R./S. | Genes | +/- | No. Bio. |

P.Name | S. Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10dpi | R. | GNAQ | - | 39 | *002455 | AJ851735 | Q5F3B5 : (Q5F3B5) Hypothetical protein |

| R. | PRKG1 | - | 33 | *015981 | BU421057 | Q9Z0Z0 : (Q9Z0Z0) cGMP-dependent protein kinase 1, beta isozyme (CGK 1 beta) (cGKI-beta) | |

| R. | CD8A | + | 27 | *007686 | CR390735 | XP_420863 : gi:50747402:ref:XP_420863.1: PREDICTED: similar to CD8 alpha chain [Gallus gallus] | |

| R. | RGS4 | - | 27 | A_87_P021537 | BX950639 | Gallus gallus finished cDNA, clone ChEST606e8. [BX950639] | |

| R. | RARB | - | 25 | A_87_P008918 | X56674 | Chicken mRNA for retinoic acid binding protein beta isoform. [X56674] | |

| R. | HAS3 | + | 12 | *013355 | BU278152 | Q8CEB9 : (Q8CEB9) Mus musculus 10 days neonate skin cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:4732404L04 product:similar to DG42III | |

| R. | SPINK5 | - | 12 | *005267 | CR353088 | P10184 : gi:1708509:sp:P10184:IOV7_CHICK Ovoinhibitor precursor >gnl:BL_ORD_ID:146450 gi:212485:gb:AAA48994.1: ovoinhibitor | |

| R. | SULF2 | - | 10 | A_87_P022688 | BX934216 | Gallus gallus finished cDNA, clone ChEST442e20. [BX934216] | |

| R. | COL14A1 | - | 9 | A_87_P008851 | X70793 | G.domesticus mRNA for collagen XIV (longer splice variant). [X70793] | |

| R. | SCN4B | - | 9 | A_87_P021873 | BX935954 | Gallus gallus finished cDNA, clone ChEST430l23. [BX935954] | |

| R. | WISP1 | - | 9 | A_87_P009711 | DQ003338 | Gallus gallus WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP-1) mRNA, complete cds. [DQ003338] | |

| R. | AHNAK | - | 5 | *004305 | BX935083 | NP_033773 : gi:61743961:ref:NP_033773.1: AHNAK nucleoprotein isoform 1 [Mus musculus] | |

| R. | P4HA2 | - | 5 | A_87_P007103 | TC198023 | Q8BU53 (Q8BU53) Mus musculus 2 days pregnant adult female oviduct cDNA, RIKEN full-length enriched library, clone:E230038K10 product:procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase (proline 4-hydroxylase), alpha II polypeptide, full insert sequence, p | |

| S. | NOS2 | + | 64 | A_87_P009073 | U46504 | Chicken macrophage nitric oxide synthase mRNA. [U46504] | |

| S. | IL8 | - | 58 | *010230 | Y14971 | O73912 : (O73912) K60 protein precursor (CXC chemokine K60) | |

| S. | IL17A | + | 53 | A_87_P035017 | AY920750 | Gallus gallus interleukin 17 mRNA, complete cds. [AY920750] | |

| S. | CTLA4 | + | 47 | *019882 | DN853042 | XP_421960 : gi:50750341:ref:XP_421960.1: PREDICTED: similar to costimulatory molecule B7 receptor CD152 [Gallus gallus] | |

| S. | IL12RB2 | + | 23 | *000640 | AJ621939 | Q5GR16 : (Q5GR16) Interleukin 12 receptor beta 2 (Fragment) | |

| S. | PLK1 | + | 20 | *001748 | AJ720598 | Q5ZJ36 : (Q5ZJ36) Hypothetical protein | |

| S. | ROR1 | - | 13 | *000634 | AJ620298 | Q705C2 : (Q705C2) Tyrosine kinase orphan receptor 1 | |

| S. | LECT2 | - | 11 | *009802 | M29449 | O88803 : (O88803) Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 precursor (Chondromodulin II) (ChM-II) | |

| S. | ABCA8 | - | 6 | *016305 | BU440826 | XP_415691 : gi:50757881:ref:XP_415691.1: PREDICTED: similar to ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A, member 10; ATP-binding cassette A10 [Gallus gallus] | |

| S. | TSPAN8 | - | 6 | *004228 | BX934864 | XP_416096 : gi:50728338:ref:XP_416096.1: PREDICTED: similar to Tm4sf3 protein [Gallus gallus] | |

| S. | COL5A2 | - | 6 | A_87_P001489 | TC224310 | Q86XF6 (Q86XF6) COL5A2 protein, partial (5%) [TC224310] | |

| R. | MMP9 | - | 63 | A_87_P037769 | AF222690 | Gallus gallus 75 kDa gelatinase mRNA, complete cds. [AF222690] | |

| 21dpi | R. | SFTPA1 | + | 38 | *000489 | AF411083 | Q90XB2 : (Q90XB2) Surfactant protein A precursor |

| R. | FBXW4 | - | 6 | *015952 | BU419266 | Q9JMJ2 : (Q9JMJ2) F-box/WD-repeat protein 4 (F-box and WD-40 domain protein 4) (Hagoromo protein) | |

| R. | CPN1 | - | 5 | *006641 | CR387490 | Q9EQV8 : (Q9EQV8) Carboxypeptidase N, polypeptide 1, 50kD | |

| S. | CD28 | + | 50 | *010136 | X67915 | P31043 : (P31043) T-cell-specific surface glycoprotein CD28 homolog precursor (CHT28) | |

| S. | CHRM4 | - | 37 | A_87_P009241 | NM_001031191 | Gallus gallus cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 4 (CHRM4), mRNA [NM_001031191] | |

| S. | F10 | - | 29 | *009605 | D00844 | P25155 : (P25155) Coagulation factor × precursor (Stuart factor) (Virus activating protease) (VAP) | |

| S. | WNT7A | - | 27 | A_87_P038155 | AB045629 | Gallus gallus mRNA for Wnt-7a, complete cds. [AB045629] | |

| S. | FMN2 | + | 12 | A_87_P005690 | TC203559 | AF218942 formin 2-like protein {Homo sapiens;}, partial (28%) [TC203559] | |

| S. | ATF6 | - | 8 | A_87_P023703 | BX931991 | Gallus gallus finished cDNA, clone ChEST222o13. [BX931991] | |

| S. | GLO1 | - | 6 | *004233 | BX934880 | XP_419481 : gi:50740506:ref:XP_419481.1: PREDICTED: similar to glyoxylase 1; glyoxalase 1 [Gallus gallus] | |

| S. | OPN4 | - | 5 | *002725 | AY882944 | XP_421494 : gi:50749124:ref:XP_421494.1: PREDICTED: similar to Opsin 4 (Melanopsin) [Gallus gallus] | |

| S. | ITGBL1 | - | 5 | *016603 | BU449144 | Q4VBJ0 : (Q4VBJ0) Integrin, beta-like 1 | |

T.Point: time point; No. Bio.: number of biofunctions involved; P.Name: Probe Name; S.Name: Systematic Name; R.: resistant genes; S.: susceptible genes; +: up-regulated; -:down-regulated.

Validation of the microarray results by real-time quantitative PCR

To validate the microarray results, we designed primers for some high-confidence genes such as CD8α, CTLA4, IL8 and USP18 and some other genes chosen at random, such as CD8β, GHR, TNFRSF6B and MMP2. Since a reference gene with stable expression is essential to avoid distortions in qPCR, the two genes GAPDH and ACTB are commonly used as internal reference for doing qPCR of MDV infected samples [24,27]. In our validation, we first used both genes as internal references to see if there were any distortions and found no differences (Additional file 6. Figure S2). Therefore, GAPDH was chosen as the internal reference. We also designed primers that span introns to further avoid the influence of DNA contamination. As shown in Additional file 2. Figure S1, we were able to validate most of the genes that are differentially expressed. Also, comparable expression profiles were observed for most of the validated genes in the microarray and qPCR (Table 4) which further suggested that the gene expression profiles from the microarray are reliable.

Table 4.

Validation of microarray results by quantitative PCR

| Genes | Probe Name in Micro-array | Time points |

Gene expression fold change after MDV infection in each lines (Inf./Non.) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| line 63 | line 72 | RCS-M | ||||||

| Micro- array |

Q-PCR | Micro- array |

Q-PCR | Micro-Array | Q-PCR | |||

| 5dpi | 1.02 | 1.45 | 2.85 | 4.07 | 1.41 | 1.29 | ||

| CTLA-4 | *019882 | 10dpi | 2.31 | 3.37 | 3.29 | 13.68 | 3.56 | 7.02 |

| 21dpi | 0.62 | 2.05 | 3.07 | 2.03 | 1.27 | 1.44 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.46 | 1.05 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.52 | 0.85 | ||

| CD8α | *007686 | 10dpi | 2.92 | 2.33 | 1.51 | 1.35 | 3.90 | 2.80 |

| 21dpi | 1.08 | 3.13 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 1.24 | 2.01 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 0.78 | ||

| CD8β | A_87_P008699 | 10dpi | 1.87 | 2.86 | 1.03 | 2.05 | 1.86 | 2.30 |

| 21dpi | 1.42 | 3.31 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 2.03 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.24 | 3.37 | 4.09 | 4.13 | 1.43 | 1.68 | ||

| USP18 | *005670 | 10dpi | 2.07 | 2.15 | 4.87 | 5.55 | 2.53 | 0.58 |

| 21dpi | 0.98 | 11.89 | 3.28 | 4.54 | 2.73 | 5.99 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.00 | 2.85 | 5.67 | 9.36 | 1.12 | 4.17 | ||

| TNFRSF6B | *003404 | 10dpi | 5.03 | 9.47 | 5.52 | 11.46 | 2.75 | 2.35 |

| 21dpi | 1.54 | 5.27 | 4.28 | 9.14 | 1.00 | 6.85 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 0.29 | ||

| MMP2 | A_87_P009159 | 10dpi | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.62 |

| 21dpi | 0.88 | 1.10 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 1.16 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.04 | 0.18 | 1.71 | 0.91 | ||

| IL8 | *010230 | 10dpi | 8.28 | 0.66 | 3.01 | 0.19 | 4.25 | 0.10 |

| 21dpi | 18.51 | 2.22 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 2.59 | ||

| 5dpi | 1.00 | 3.14 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 1.85 | 0.81 | ||

| GHR | A_87_P009190 | 10dpi | 8.57 | 1.25 | 0.24 | 1.82 | 1.00 | 0.53 |

| 21dpi | 1.54 | 1.56 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 2.76 | ||

The numbers here represent the fold change of gene expression after MDV infection. The numbers equal to 1.00 means the expression level doesn't change after MDV infection. The numbers > 1.00 means the expression level is increased after MDV infection while numbers < 1.00 indicate that the expression level is reduced after MDV infection. The numbers in bold and italic are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Discussion

There have been several studies looking at gene expression changes related to disease in general [28-30] and MD in particular [24,27,31-34], although results tend to vary a lot. MD is a complex disease with the disease phenotype in susceptible individuals depending on the location and frequency of tumors. Any single gene with differential expression cannot fully explain the phenomenon of host resistance or susceptibility. Therefore, we tried to use a genome-wide approach to build on the current understanding of Marek's disease pathogenesis and immune response to MDV. Upon close examination of the transcriptional responses, dramatically increased numbers of significant genes were observed at 10dpi in RCS-M and at 21dpi in line 72 at lower FDR levels (FDR < 0.2) which indicated a strongly enhanced transcriptional response. At a more relaxed FDR level (FDR < 0.5), we find comparable numbers of differentially expressed genes at 5, 10 and 21dpi in line 63 and RCS-M. Line 72 has similar numbers of significant genes at 10dpi but there is a definite increase in the transcriptional response at 21dpi with close to twice as many differentially expressed genes. However, even at this level, we do not find any significantly expressed genes at 5dpi in line 72 (FDR<0.5), indicating a much muted transcriptional response (Table 1).

Over the years, several attempts have been made to identify the gene profiles that change as a result of MDV infection. For example, using microarray analysis, studies have identified some genes related to MDV infection by using different chicken lines and MDV strains [24,31-34]. When chicken embryo fibroblasts were infected with MDV, genes related to inflammation, cell-growth and differentiation and antigen presentation, such as MIP, IL-13R, MHC I and MHC II were induced both at 2dpi and 4dpi [33]. In contrast, in spleen tissue, several other genes were found to be affected at an early stage, including TLR-15, IL-6 and Mx1[31]. In chickens with major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-associated MD resistance, the immunoglobulin genes IgG and IgM were differentially expressed after MDV infection at 7dpi and 14dpi[24], whereas in lines 6 and 7 from ADOL, that carry the same MHC haplotype (B2) but differ in their response to MDV infection[35], various alloantigens like Ly-4 [16] and Bu-1 [17] were differentially expressed. Linkage and association studies as well as integrated analyses using genetic mapping and microarrays have revealed some genes that may be responsible for MD progression or resistance, such as GH, IFNγ and SULT [27]. However, it is difficult to find a consensus amongst these studies due to variation in experimental parameters such as, virus strain or in vitro derived samples. By using a genome-wide approach and three chicken lines with varying resistance to MD, we were able to generate a comprehensive list of candidate genes that can be used for studying MD-resistance and susceptibility. Besides finding some genes that were reported in previous studies, such as Mx1, we also found several genes that have not been reported before in this context, such as CD8α, IL8, USP18, and CTLA4. CD8α, present in the putative resistant gene list at 10dpi, codes a surface glycoprotein expressed on a subpopulation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [36], which binds to the α3 domain or membrane-proximal domain of most of the known HLA class I molecules to enhance CTL activation [37-41]. It has been shown that CD8α was up-regulated by MDV infection at the early cytolytic stage (4dpi and 7dpi), whereas IgM and CD3 were down-regulated [34]. These are similar to our microarray results, the slight difference being possibly due to the differences in virus strains and genetic background of the chickens. The CD8α gene was significantly up-regulated at 10dpi in the MD-resistant chicken line (line 63) and RCS-M, but down-regulated in the MD-susceptible chicken line (line 72). In chickens vaccinated against MDV an increase of CD8α cells was found after MDV infection compared to unvaccinated chickens [32]. The vaccinated birds were phenotypically similar to line 63 and hence, this result is consistent with our finding. The above evidence, taken all together, leads us to speculate that CD8α plays an important role in MD resistance. The induction of CD8α gene may result from an increase of the CD8+ T cells that eliminate MDV infected cells in the resistant chickens. However, this scenario needs further validation.

In contrast, CTL-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), present in our putative susceptible gene list at 10dpi, is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed on the surface of an activated T cell [42]. It has been reported that the knockout of CTLA-4 resulted in a lymphoproliferative disorder and death in mice, which indicated a very important role of CTLA-4 in negative regulation of T cell activation [43]. The blockade of the CTLA-4 pathway results in a rejection of tumor [44,45], indicating that a lower CTLA-4 expression may be important for antitumor response. Therefore, in humans, a current strategy of immunotherapy focuses on the blockade of the CTLA-4 pathway [46,47]. A higher expression of CTLA-4 was detected at lymphoma lesions in MD-susceptible chickens at 21dpi, although no significant difference was found in the whole tissue [48]. Importantly, a similar result existed in our data: the fold change of CTLA-4 at 10dpi after MDV infection is much less in line 63 than in line 72 and RCS-M (Table 4), indicating a lower level of CTLA-4 involved in antitumor immune response.

In addition to the above genes, some networks and biofunctions were also observed to be different between MD-resistant and susceptible chickens. It is interesting to note that most of the differentially expressed genes were not enriched in biofunctions of immune related diseases, but with other diseases or metabolism. This is consistent with the fact that apart from the generation of tumors, MD-susceptible chickens also exhibit weight loss, paralysis and other symptoms. However, some immune response-related biofunctions were enriched only in line 63 and RCS-M chickens. It was thought for a long time that tumor cells have no antigen and this enables them to escape the host immune system. While the finding of the melanoma antigen in the late 1980's shed light on the role of immune system to fight against tumors [49], the tumor cells are known to also have immunosuppressive agents that help them evade detection and killing by the immune system [50,51]. The networks related to immune response found in line 63 chickens, suggests that in these chickens the immune system is activated to counteract the development of tumor. In contrast, the transformed cells in susceptible chickens are able to escape the natural resistance of the immune system to generate tumors, although at present it is still unclear if this is due to a larger initial damage to the immune system [52] or the immunosuppression induced by MDV in line 72 chickens. NOS2 is an enzyme that catalyzes the generation of NO [53] which in turn increases the virulence of MDV by immunosuppression [54]. However, it has also been shown that NO has inhibitory effects on MDV replication [55] and NO production in MDV-infected susceptible chickens (MHC, B13B13) is the lowest in comparison to MD-infected resistant birds (MHC, B19B19) [55,56]. Interestingly, we found that the NOS2 gene was up-regulated in susceptible chicken lines. Therefore, it remains to be seen whether the up-regulation of NOS2 in line 72 could induce immunosuppression and increase the risk of tumor generation in MD-susceptible chickens. The above results indicate that different immune response in resistant and susceptible chickens lead to the vastly different responses to MDV infection.

To minimize transcriptional variations and take full advantage of a similar genetic background in the inbred lines, we paired birds by line and dpi, respectively, and tested the difference between infected and non-infected individuals. This procedure not only led us to identify the genes most likely related to MD resistance and susceptibility, but also revealed a common broad influence of MDV infection on the hosts. By using IPA to analyze differentially expressed gene sets, we found focused pathways enriched in metabolism, tissue development, gene expression and cell cycle along with other immune-related pathways preferentially enriched in resistant chickens. These results suggested possible mechanisms and specific genes related to MD-resistance or -susceptibility. We hypothesized that there are four possible causes behind MD-resistance: some genes activated in resistant chickens can (i) cause loss of the MDV receptor, (ii) help to clear infected cells, (iii) affect the viral life cycle or (iv) prevent transformation of infected cells. Our observations and previous research have showed that the virus load in both resistant and susceptible chickens was similar at early stages of infection [18,57], suggesting the presence of receptors for MDV in both resistant and susceptible chickens. Thus, the latter three of the aforementioned possibilities are more likely to be the main reasons for MD-resistance although it is not easy to say which of these play a big role in non-MHC associated resistance.

Conclusions

Using a comprehensive genome-wide study of gene expression in chicken lines with varying resistance to MD, we were able to identify pathways and genes that may be involved in MD-resistance and susceptibility. Phenotypic similarities between the chicken lines enabled us to narrow the list of putative genes to 108 genes associated with MD-resistance and 121 genes associated with susceptibility. Combining network analysis with differential gene expression analysis helped uncover high-confidence genes such as CD8α, IL8, USP18, and CTLA-4 and several immune-related biofunctions with potentially important consequences to MDV infection. Our findings add to the current understanding of the mechanism behind resistance and susceptibility to MD while expanding the scope of future studies with a comprehensive list of putative genes. Our approach also underlines the importance of comprehensive functional studies to gain valuable biological insight into the genetic factors behind complex disease.

Methods

Sample Collection for Microarray

Three inbred lines of White Leghorn (line 63, line 72 and RCS-M) were divided into two treatment groups each containing 60 chickens. One group from each line was infected with a partially attenuated very virulent strain (vv+) of MDV-648A passage 40 [1], at day 5 after hatch, intra-abdominally at a viral dosage of 500 plaque-forming units (PFU) per chick. The other group was not infected. The viral-challenge experiment was conducted in the BL-2 facility at ADOL. Four chickens from each group were euthanized at 5dpi (cytolytic infection period), 10dpi (latency period) and 21dpi (reactivation period), respectively. Spleen samples were collected and stored in RNAlater solution (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) at -20°C until RNA extraction. All the experimental chickens were managed and euthanized following ADOL's Guidelines for Animal Care and Use (revised April, 2005) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR Guide) in 1996 (http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=5140).

RNA Extraction

Approximately 30~50mg spleen tissues were homogenized in TRizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA), and total RNA extraction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA). Total RNA was purified using the RNAeasy mini column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and contaminant DNA was digested by DNase I (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA concentration was assessed using Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and RNA quality determined by 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Foster City, CA, USA).

Microarray Experiment Design, Hybridization and Analysis

Custom Agilent 4 × 44K chicken microarrays were used in this study. The 4 × 44K chicken arrays were designed based on the whole chicken genome sequence and consist of 42,034 probes [58]. Four biological replicates of each group were carried out at each time point. RNA was labelled using the Agilent Quick-Amp labelling kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). In two of the four replicates of each experimental group, the infected samples were labelled with Cy3 and the uninfected two were labelled with Cy5. A total of 825 ng of Cy3 and Cy5 labelled cDNAs were then hybridized to the 4 × 44K Agilent chicken arrays. Following stringency washes, slides were scanned on an Agilent G2505B microarray scanner and the resulting image files analyzed with Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 9.5.1). All procedures were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocols. After the microarray analysis was performed in three chicken lines at three time points, we first tested for the presence of outliers (JMP Genomics, Version 9). Parallel plots and PCA revealed the presence of outliers in our datasets, which were subsequently removed. A parallel plot subsequently indicated that the log2 intensities had similar distributions across all remaining arrays (Additional file 7. Figure S3). After the initial quality assessment step we performed linear modelling using the limma package in R to find differentially expressed genes. Dye bias was removed by normalizing within array using loess normalization [59] and normalization between arrays was carried out using quantile normalization [60]. The p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR calculation procedure [26]. We compared age-matched individuals from the same line before and after infection with MDV at three time points of disease progression. All the array data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Yu et al., 2010) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE24017 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE24017).

Data Mining and Network Analysis

The expressed sequence tags (ESTs) specific to microarray probes were mapped to proteins or protein homologs with GenBank names, Swissprot, pfam or RefSeq accession numbers using the BioMart data mining system via Sigenae (Details found on http://www.sigenae.org). Proteins with the identity of 40% or more were considered to be homologs [61]. In case of multiple proteins mapping to a probe, proteins with the highest identity were used to create a unique mapping. The resultant list was then analyzed using IPA to detect the enrichment of biofunctions and networks. Core analysis was performed in IPA using significantly expressed genes from the statistical analysis based on the Ingenuity Knowledge Base with the reference set "Genes + Endogenous Chemicals".

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

RNA samples for quantitative real-time PCR were used for first strand cDNA synthesis using 1 μg of total RNA by SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA) with oligo (dT)12-18 primers (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA). Samples were then analyzed with real time RT-PCR using an iCycler iQ PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The real time RT-PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 μl with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each group has 4 biological replicates with 3 replicates for one reaction and each reaction was repeated twice. The mRNA expression was normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). The primers for all the genes analyzed are in Additional file 8. Table S5. All steps of our Q-PCR validation, which include RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, reference gene selection, Q-PCR procedures, and data analysis were performed according to the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines [62]

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YY extracted RNA, performed array hybridization and partial data analysis. JL performed the pathway analysis, experimental confirmation of microarray results and wrote the paper. AM analyzed the microarray data and wrote the paper. FT extracted RNA. HMZ collected samples and revised the paper. PY did data mining before IPA analysis. JZS designed the experiments and revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Number of genes differentially expressed after MDV infection including MDV genes. This table contains the number of genes that are differentially expressed after MDV infection which including all the genes that were shown in the microarray like MDV genes. Genes with differential expression were termed with p < 0.05, LogFC>1.5 and FDR < 0.5. +: up-regulated after MDV infection; -: down-regulated after MDV infection.

Figure S1. Validation of microarray data by Q-PCR. This figure showing the Q-PCR validation result of the genes that shown significant different expression after MDV infection in three time points (5dpi, 10dpi, and 21dpi). Line 63.non: non-infected control of line 63 chickens; Line 63.inf: infected line 63 chickens; Line 72.non: non-infected control of line 72 chickens; Line 72.inf: infected line 72 chickens; non: non-infected control of chicken; inf: infected RCS-M chicken. n = 4 for each line. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Table S2. Homologs of chicken ESTs from BioMart. This table includes the homologs that were converted from the chicken ESTs on the microarray. The data mining was down on BioMark (details see http://www.sigenae.org).

Table S3. Possible MD-resistant and susceptible gene lists at 10dpi and 21dpi. This table showed the possible candidates for MD-resistance and susceptibility at 10dpi and 21dpi. The gene lists were chosen by the following criteria: Genes differentially expressed after MDV infection and having similar trends in line 63 and RCS-M but not in line 72 are likely to be related to MD-resistance; conversely, genes showing similar trends in line 72 and RCS-M but not in line 63 are possibly related to MD-susceptibility.

Table S4. Biofunction enrichment of the MD-resistant and susceptible genes at 10dpi and 21dpi. The genes that are listed as possible MD-resistant and -susceptible genes were used to do the IPA analysis. This table showed the biofunctions that were enriched by these genes at 10dpi and 21dpi.

Figure S2. Stability test of the internal reference. ACTB gene was added to normalize the gene expression when doing the Q-PCR experiment to monitor the stability of the Q-PCR result when using GAPDH as the internal control. A similar ratio shown in both normalization method indicated a stabilized system of the Q-PCR.

Figure S3. A parallel plot of kernel densities shows similar distribution of log2 intensities in all arrays after normalization.

Table S5. Primers for validation of microarray results by quantitative PCR.

Contributor Information

Ying Yu, Email: yuying@cau.edu.cn.

Juan Luo, Email: jluo1@umd.edu.

Apratim Mitra, Email: amitra83@umd.edu.

Shuang Chang, Email: shchang@msu.edu.

Fei Tian, Email: feitian@umd.edu.

Huanmin Zhang, Email: hmzhang@msu.edu.

Ping Yuan, Email: pyuan@umd.edu.

Huaijun Zhou, Email: hjzhou@poultry.tamu.edu.

Jiuzhou Song, Email: songj88@umd.edu.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by USDA-NRI/NIFA 2008-35204-04660 and USDA-NRI/NIFA 2010-65205-20588.

References

- Witter RL, Calnek BW, Buscaglia C, Gimeno IM, Schat KA. Classification of Marek's disease viruses according to pathotype: philosophy and methodology. Avian Pathol. 2005;34(2):75–90. doi: 10.1080/03079450500059255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnek BW, Witter RL. Diseases of Poultry. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davison F, Nair V. Marek's Disease: An Evolving Problem. Oxford: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SC, Young JR, Baaten BJ, Hunt L, Ross LN, Parcells MS, Kumar PM, Tregaskes CA, Lee LF, Davison TF. Marek's disease is a natural model for lymphomas overexpressing Hodgkin's disease antigen (CD30) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(38):13879–13884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305789101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison A. Comments on the phylogenetics and evolution of herpesviruses and other large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 2002;82(1-2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulman ER, Afonso CL, Lu Z, Zsak L, Rock DL, Kutish GF. The genome of a very virulent Marek's disease virus. J Virol. 2000;74(17):7980–7988. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.17.7980-7988.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LF, Wu P, Sui D, Ren D, Kamil J, Kung HJ, Witter RL. The complete unique long sequence and the overall genomic organization of the GA strain of Marek's disease virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(11):6091–6096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnek BW. Pathogenesis of Marek's disease virus infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;255:25–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56863-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnek BW. Marek's disease--a model for herpesvirus oncology. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1986;12(4):293–320. doi: 10.3109/10408418509104432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek WR, Calnek BW, Schat KA, Chen CH. Characterization of Marek's disease virus-infected lymphocytes: discrimination between cytolytically and latently infected cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;70(3):485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnek BW, Schat KA, Ross LJ, Chen CL. Further characterization of Marek's disease virus-infected lymphocytes. II. In vitro infection. Int J Cancer. 1984;33(3):399–406. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calnek BW, Schat KA, Ross LJ, Shek WR, Chen CL. Further characterization of Marek's disease virus-infected lymphocytes. I. In vivo infection. Int J Cancer. 1984;33(3):389–398. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon LD, Hunt HD, Cheng HH. A review of the development of chicken lines to resolve genes determining resistance to diseases. Poult Sci. 2000;79(8):1082–1093. doi: 10.1093/ps/79.8.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumstead N, Sillibourne J, Rennie M, Ross N, Davison F. Quantification of Marek's disease virus in chicken lymphocytes using the polymerase chain reaction with fluorescence detection. J Virol Methods. 1997;65(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(96)02172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SC, Basaran BH, Davison TF. Resistance to Marek's disease herpesvirus-induced lymphoma is multiphasic and dependent on host genotype. Vet Pathol. 2001;38(2):129–142. doi: 10.1354/vp.38-2-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen TL, Longenecker BM, Pazderka F, Gilmour DG, Ruth RF. A T-cell antigen system of chickens: Ly-4 and Marek's disease. Immunogenetics. 1977;5:535–552. doi: 10.1007/BF01570512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour DG, Brand A, Donnelly N, Stone HA. Bu-1 and Th-1, two loci determining surface antigens of B or T lymphocytes in the chicken. Immunogenetics. 1976;3:549–563. doi: 10.1007/BF01576985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Underwood G, Davison F. Differential cytokine responses following Marek's disease virus infection of chickens differing in resistance to Marek's disease. J Virol. 2003;77(1):762–768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.762-768.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zhang H, Tian F, Zhang W, Fang H, Song J. An integrated epigenetic and genetic analysis of DNA methyltransferase genes (DNMTs) in tumor resistant and susceptible chicken lines. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo RL, Bacon LD, Liu HC, Witter RL, Groenen MA, Hillel J, Cheng HH. Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci affecting susceptibility to Marek's disease virus induced tumors in F2 intercross chickens. Genetics. 1998;148(1):349–360. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonash N, Bacon LD, Witter RL, Cheng HH. High resolution mapping and identification of new quantitative trait loci (QTL) affecting susceptibility to Marek's disease. Anim Genet. 1999;30(2):126–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1999.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz EM, Fulton JE, O'Sullivan NP, Arthur JA, Wang J, Dekkers JC, Soller M. Mapping quantitative trait loci affecting susceptibility to Marek's disease virus in a backcross population of layer chickens. Genetics. 2007;177(4):2417–2431. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz EM, Fulton JE, O'Sullivan NP, Arthur JA, Cheng H, Wang J, Soller M, Dekkers JC. Mapping QTL affecting resistance to Marek's disease in an F6 advanced intercross population of commercial layer chickens. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarson AJ, Parvizi P, Lepp D, Quinton M, Sharif S. Transcriptional analysis of host responses to Marek's disease virus infection in genetically resistant and susceptible chickens. Anim Genet. 2008;39(3):232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RF, Coussens PM, Lee LF, Velicer LF. Current Research on Marek's Disease. American Association of Avian Pathologists, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini YHY. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a Practical and Powerful Approach to Mulyiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Liu HC, Cheng HH, Tirunagaru V, Sofer L, Burnside J. A strategy to identify positional candidate genes conferring Marek's disease resistance by integrating DNA microarrays and genetic mapping. Anim Genet. 2001;32(6):351–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2001.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock EM, Geddes JW, Chen KC, Porter NM, Markesbery WR, Landfield PW. Incipient Alzheimer's disease: microarray correlation analyses reveal major transcriptional and tumor suppressor responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(7):2173–2178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308512100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow T. Gene expression microarray improves prediction of breast cancer outcomes. Manag Care. 2007;16(8):51–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Hata F, Nishimori H, Honmou O, Yasoshima T, Nomura H, Ohno K, Hirai I, Kamiguchi K, Isomura H, Hirohashi Y, Denno R, Sato N, Hirata K. Differential gene expression screening between parental and highly metastatic pancreatic cancer variants using a DNA microarray. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22(2):307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M, Sarson AJ, Huebner M, Sharif S, Kireev D, Zhou H. Marek's disease virus-induced immunosuppression: array analysis of chicken immune response gene expression profiling. Viral Immunol. 2010;23(3):309–319. doi: 10.1089/vim.2009.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano R, Konnai S, Onuma M, Ohashi K. Microarray analysis of host immune responses to Marek's disease virus infection in vaccinated chickens. J Vet Med Sci. 2009;71(5):603–610. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RW, Sofer L, Anderson AS, Bernberg EL, Cui J, Burnside J. Induction of host gene expression following infection of chicken embryo fibroblasts with oncogenic Marek's disease virus. J Virol. 2001;75(1):533–539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.533-539.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarson AJ, Abdul-Careem MF, Zhou H, Sharif S. Transcriptional analysis of host responses to Marek's disease viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2006;19(4):747–758. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone HA. Use of highly inbred chickens in research. In US Dept Agriculture Technical Bulletin. 1975. p. 1514.

- Ledbetter JA, Evans RL, Lipinski M, Cunningham-Rundles C, Good RA, Herzenberg LA. Evolutionary conservation of surface molecules that distinguish T lymphocyte helper/inducer and cytotoxic/suppressor subpopulations in mouse and man. J Exp Med. 1981;153(2):310–323. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter RD, Norment AM, Chen BP, Clayberger C, Krensky AM, Littman DR, Parham P. Polymorphism in the alpha 3 domain of HLA-A molecules affects binding to CD8. Nature. 1989;338(6213):345–347. doi: 10.1038/338345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter RD, Benjamin RJ, Wesley PK, Buxton SE, Garrett TP, Clayberger C, Krensky AM, Norment AM, Littman DR, Parham P. A binding site for the T-cell co-receptor CD8 on the alpha 3 domain of HLA-A2. Nature. 1990;345(6270):41–46. doi: 10.1038/345041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter TA, Rajan TV, Dick RF, Bluestone JA. Substitution at residue 227 of H-2 class I molecules abrogates recognition by CD8-dependent, but not CD8-independent, cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;337(6202):73–75. doi: 10.1038/337073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayen J, Huang JH, Meyerson H, Zhang D, Getty R, Greenspan N, Tykocinski M. Class I MHC alpha 3 domain can function as an independent structural unit to bind CD8 alpha. Mol Immunol. 1995;32(4):267–275. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)00149-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway CA Jr. The T cell receptor as a multicomponent signalling machine: CD4/CD8 coreceptors and CD45 in T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:645–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.003241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariavach P, Mattei MG, Golstein P, Lefranc MP. Human Ig superfamily CTLA-4 gene: chromosomal localization and identity of protein sequence between murine and human CTLA-4 cytoplasmic domains. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18(12):1901–1905. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, Thompson CB, Griesser H, Mak TW. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270(5238):985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend SE, Allison JP. Tumor rejection after direct costimulation of CD8+ T cells by B7-transfected melanoma cells. Science. 1993;259(5093):368–370. doi: 10.1126/science.7678351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271(5256):1734–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abken H, Hombach A, Heuser C, Kronfeld K, Seliger B. Tuning tumor-specific T-cell activation: a matter of costimulation? Trends Immunol. 2002;23(5):240–245. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Kojima Y, Uno T, Hayakawa Y, Teng MW, Yoshizawa H, Yagita H, Gejyo F, Okumura K, Smyth MJ. Combination therapy of established tumors by antibodies targeting immune activating and suppressing molecules. J Immunol. 2010;184(10):5493–5501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Buza JJ, Burgess SC. Genotype-dependent tumor regression in Marek's disease mediated at the level of tumor immunity. Cancer Microenviron. 2009;2(1):23–31. doi: 10.1007/s12307-008-0018-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411(6835):380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SB, Dean JH, Law LW. Defects in cell-mediated immunity during growth of a syngeneic simian virus-induced tumor. Int J Cancer. 1975;15(1):152–169. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910150118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CC, Rodrigues D. Switching on the macrophage-mediated suppressor mechanism by tumor cells to evade host immune surveillance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(7):4265–4269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baigent SJ, Davison TF. Development and composition of lymphoid lesions in the spleens of Marek's disease virus-infected chickens: association with virus spread and the pathogenesis of Marek's disease. Avian Pathology. 1999;28:287–300. doi: 10.1080/03079459994786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstermann U, Kleinert H. Nitric oxide synthase: expression and expressional control of the three isoforms. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;352(4):351–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00172772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosinski KW, Yunis R, O'Connell PH, Markowski-Grimsrud CJ, Schat KA. Influence of genetic resistance of the chicken and virulence of Marek's disease virus (MDV) on nitric oxide responses after MDV infection. Avian Dis. 2002;46(3):636–649. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2002)046[0636:IOGROT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Z, Schat KA. Inhibitory effects of nitric oxide and gamma interferon on in vitro and in vivo replication of Marek's disease virus. J Virol. 2000;74(8):3605–3612. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3605-3612.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Z, Schat KA. Expression of cytokine genes in Marek's disease virus-infected chickens and chicken embryo fibroblast cultures. Immunology. 2000;100(1):70–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunis R, Jarosinski KW, Schat KA. Association between rate of viral genome replication and virulence of Marek's disease herpesvirus strains. Virology. 2004;328(1):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Chiang HI, Zhu J, Dowd SE, Zhou H. Characterization of a newly developed chicken 44K Agilent microarray. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Speed T. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods. 2003;31(4):265–273. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Thorne NP, Goldstein DR. Normalization for two-color cDNA microarray data. Institute of Mathematical Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CA, Kreychman J, Gerstein M. Assessing annotation transfer for genomics: quantifying the relations between protein sequence, structure and function through traditional and probabilistic scores. J Mol Biol. 2000;297(1):233–249. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem. 2009;55(4):611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Number of genes differentially expressed after MDV infection including MDV genes. This table contains the number of genes that are differentially expressed after MDV infection which including all the genes that were shown in the microarray like MDV genes. Genes with differential expression were termed with p < 0.05, LogFC>1.5 and FDR < 0.5. +: up-regulated after MDV infection; -: down-regulated after MDV infection.

Figure S1. Validation of microarray data by Q-PCR. This figure showing the Q-PCR validation result of the genes that shown significant different expression after MDV infection in three time points (5dpi, 10dpi, and 21dpi). Line 63.non: non-infected control of line 63 chickens; Line 63.inf: infected line 63 chickens; Line 72.non: non-infected control of line 72 chickens; Line 72.inf: infected line 72 chickens; non: non-infected control of chicken; inf: infected RCS-M chicken. n = 4 for each line. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Table S2. Homologs of chicken ESTs from BioMart. This table includes the homologs that were converted from the chicken ESTs on the microarray. The data mining was down on BioMark (details see http://www.sigenae.org).

Table S3. Possible MD-resistant and susceptible gene lists at 10dpi and 21dpi. This table showed the possible candidates for MD-resistance and susceptibility at 10dpi and 21dpi. The gene lists were chosen by the following criteria: Genes differentially expressed after MDV infection and having similar trends in line 63 and RCS-M but not in line 72 are likely to be related to MD-resistance; conversely, genes showing similar trends in line 72 and RCS-M but not in line 63 are possibly related to MD-susceptibility.

Table S4. Biofunction enrichment of the MD-resistant and susceptible genes at 10dpi and 21dpi. The genes that are listed as possible MD-resistant and -susceptible genes were used to do the IPA analysis. This table showed the biofunctions that were enriched by these genes at 10dpi and 21dpi.

Figure S2. Stability test of the internal reference. ACTB gene was added to normalize the gene expression when doing the Q-PCR experiment to monitor the stability of the Q-PCR result when using GAPDH as the internal control. A similar ratio shown in both normalization method indicated a stabilized system of the Q-PCR.

Figure S3. A parallel plot of kernel densities shows similar distribution of log2 intensities in all arrays after normalization.

Table S5. Primers for validation of microarray results by quantitative PCR.