Abstract

Type I IFN and IL-12 are well documented to serve as so called “signal 3” cytokines, capable of facilitating CD8+ T cell proliferation, effector function and memory formation. While their ability to serve in this capacity is well established, to date, no non-cytokine signal 3 mediators have been clearly identified. We have established a vaccine model system in which the primary CD8+ T cell response is independent of either IL-12 or type I IFN receptors, but dependent on CD27/CD70 interactions. We show here that primary and secondary CD8+ T cell responses are generated in the combined deficiency of IFN and IL-12 signaling. In contrast, antigen specific CD8+ T cell responses are compromised in the absence of the TNF receptors CD27 and OX40. These data indicate that CD27/OX40 can serve the central function as signal 3 mediators, independent of IFN or IL-12, for the generation of CD8+ T cell immune memory.

Introduction

The goal of vaccine development is to provide long-term immunological protection to the host in the form of immunological memory. For CD8+T cells, memory is characterized by the capacity for a more rapid and more robust expansion of antigen-specific cells upon secondary exposure to antigen than what is obtainable in a naïve host (1, 2). Additionally, unlike naïve cells, these memory cells produce large amounts of IFN-γ and lyse target cells after short-term antigenic stimulation in vitro (2). T cell activation and the acquisition of these memory traits require TCR-initiated recognition of antigen, co-stimulation through CD28 via B7 (CD80 or CD86) family members, and IL-12 or Type I IFN (IFN), referred to as signal 3 cytokines (3). In the absence of a requisite signal 3, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells fail to develop effector functions, and any cells that survive long-term are tolerant, unable to proliferate in response to secondary challenge (4).

In addition to the role of cytokines in this process, members of the TNFR/TNFL superfamily have also been shown to be important contributors to the development of CD8+ T cell immunity. Both the use of TNF ligand blocking antibodies and TNF receptor deficient mice have shown individual and cooperative roles for CD27, OX40, and 4-1BB in promoting the generation of CD8+ T cell immunity (5–15). Generally speaking, the stimulation of a CD8+ T cell via one or more of these TNF receptors enhances T cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation to effector function (16, 17). CD27 in particular is reported to mediate CD8+ T cell expansion and memory formation in response to challenge with influenza (5, 6, 9) and even facilitate breaking peripheral tolerance (12, 18). Recent reports indicate that CD27 signaling is necessary for the localization of flu specific responses to the lung (5, 6, 9), in large part due to the ability of CD27 to augment IL-2 production and subsequent acquisition of effector function (19). However, primary and secondary expansion of flu specific CD8+ T cells within the lymphoid tissue is largely intact even in CD27−/− mice (5, 6, 9). While the additional loss of other TNF receptor/ligand signals further compromises flu specific CD8+ T cell responses, they generally lead to a 3–4 fold reduction in primary and secondary CD8+ responses (9), resembling less the level of ablation of T cell memory associated with the loss of a defined signal 3 mediator. Thus, while TNF receptor simulation of CD8+ T cells clearly favors a more robust response, the degree to which these signals can support the formation of CD8 T cell memory in the absence of classical signal 3 mediators such as IFN and IL-12 is unclear.

We have shown previously that vaccination with combined TLR/anti-CD40 agonists induces enhanced expression of CD70, the ligand for CD27, on dendritic cells, and that this TNFR-TNFL interaction stimulates a robust primary expansion of antigen-specific CD8+T cells (10). Our vaccine also induced a modest expression of OX40L and 4-1BBL, but interaction with their cognate receptors was not involved in the stimulation of primary expansion of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells(10, 13). Herein we describe the ability of combined TLR agonist/anti-CD40 vaccination to program CD8+ T cells for memory in the absence of IL-12 and IFN signaling. Furthermore, we show that CD27/OX40 stimulation of the CD8+ T cells can serve as a bona fide “signal 3”, enabling functional CD8+ T cell memory.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Six- to eight-week-old female wild type C57BL/6 and B6.Ly5.2 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. IL-12Rβ1−/− and IFNαβR−/−, CD27−/− (5) (provided by Dr. Jannie Borst, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam), and OX40−/− mice (20, 21) (provided by Dr. Michael Croft, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology) were obtained and bred in the National Jewish Health Biological Resource Center. Double receptor knockout mice, IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− (DKO), were generated in-house by crossing IL-12Rβ1−/− mice with IFNαβR−/− mice. Double TNFR knockout mice, CD27−/−OX40−/−, were generated in-house by crossing CD27−/− mice with OX40−/− mice. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at National Jewish Health approved all animal procedures.

Mixed Bone Marrow Chimeras

Bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias from congenic mouse strains and resuspended to single cell suspension in sterile PBS as previously described. Bone marrow was mixed to a 1:1 ratio and injected i.v. into lethally-irradiated recipient mice (900 rad). Chimeric mice were fed an antibiotic-containing rodent chow (Septra, Harlan Teklad) for 4–5 weeks to prevent bacterial infection. Reconstitution of the immune system was complete 12 weeks after iradiation at which time mice were immunized as described below. Reconstitution of mixed chimera’s occurred, on average, to the expected 1:1, or 1:1:1 ratios (not shown).

Immunization and Secondary Challenge

Mice were injected i.v. with 100 µg whole ovalbumin protein or 100 µg B8R peptide with 50 µg Pam3Cys (InvivoGen) and 50 µg anti-CD40 antibody (clone FGK45). In some experiments, 50ug of polyIC (GE Healthcare) was used in place of the Pam3cys. In some experiments, either anti-CD70 (clone FR70, BioXcell) or anti-OX40L (RM134L, BioXcell) blocking antibody was injected i.p. (250 µg) on days -1, 0, 2, and 4 of immunization. For secondary challenge, mice were infected i.v. with 2 × 105 cfu listeria monocytogenes (Lm) expressing ovalbumin protein (kindly provided by Mike Bevan, University of Washinton) or 5 × 105 cfu LM expressing ovalbumin protein and B8R peptide (Kindly provided by Rodney Prell while at Cerus Corporation).

Staining and Detection of Antigen-Specific CD8+ T Cells

Seven days after primary challenge or five days after secondary challenge, PBLs were isolated via dorsal aorta bleed, and in some experiments, spleens were also removed and homogenized into single-cell suspensions as described previously (10). Cells were plated in 96-well plates and stained with PE-conjugated Kb/SIINFEKL (Ovalbumin) or Kb/TSYKFESV (B8R) tetramer (Beckman Coulter) for 1 h at 37°C. Antibodies against CD8 (PerCP conjugate, clone 53-6.7), CD19 (APC-Cy7, clone 1D3), CD44 (Pacific Blue, clone IM7), and KLRG1 (APC, clone 2F1) were added for an additional 30 min at 37°C. For staining of cells from mixed bone marrow chimeric mice, anti-CD45.1 (APC, clone A20), CD3 (APC-Cy7, clone 145-2C11), and anti-CD45.2 (alexa fluor 488, clone 104) were used instead of KLRG1 and CD19. The cells were then washed and resuspended in FACS buffer for flow cytometric analysis. Data were collected on a CyAn LX flow cytometer using Summit software (Dako Cytomation), and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). For analysis, the data were gated on CD8+ CD19− events and analyzed for tetramer staining by the activation marker CD44, the antigen-specific cells being CD44high. For analysis of samples from mixed bone marrow chimeric mice, the data were gated on CD8+ CD3+ events, separated based on CD45.1 and CD45.2 staining, and analyzed for tetramer staining by the activation marker CD44. All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend.

Statistical Analyses

Paired (bone marrow chimeras) and unpaired statistical analyses were made between experimental populations or groups using Student’s t test with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). All experiments were performed independently at least twice with a minimum of three mice per group.

Results and Discussion

CD8+ T Cells that Lack IL-12Rβ1 and IFNαβR have Primary and Memory Responses Similar to WT

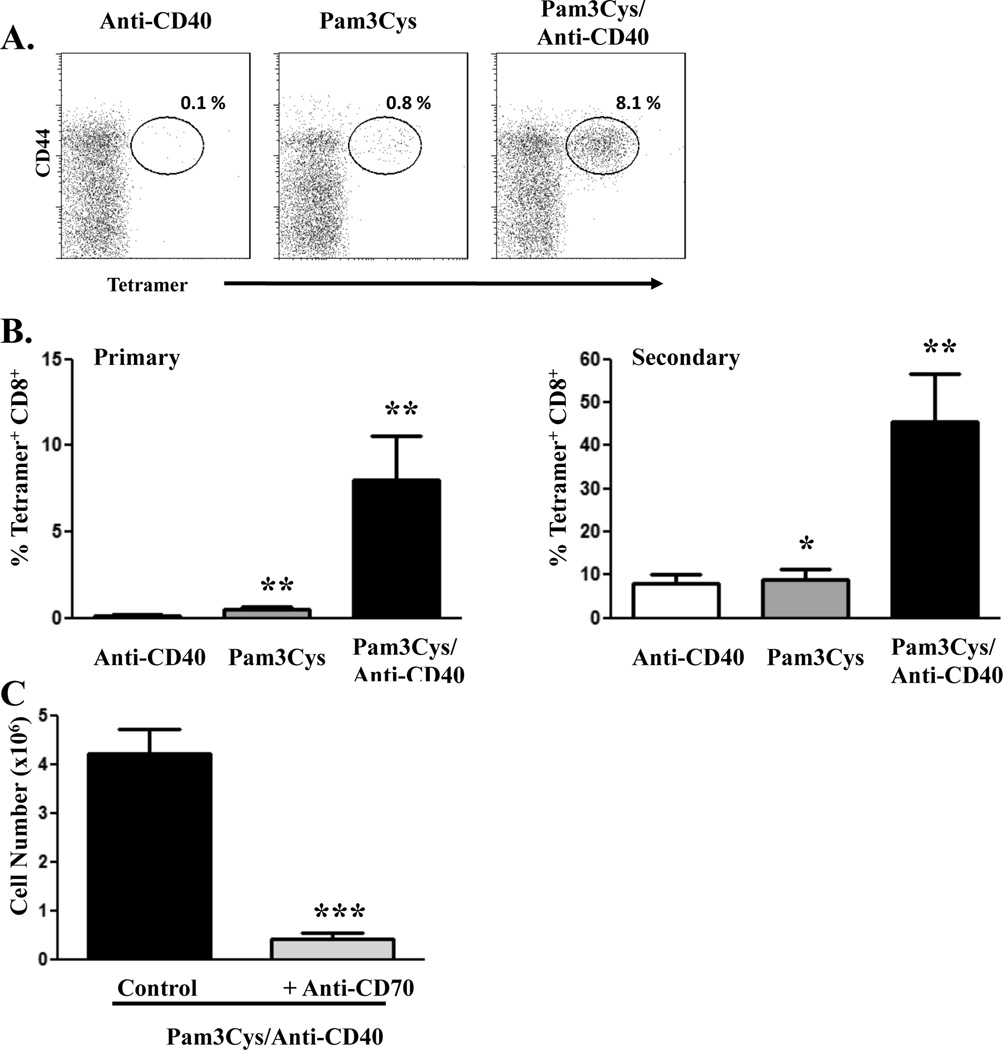

As we previously showed (10, 22), immunization with protein antigen in presence of a combination of the TLR2 agonist, Pam3Cys, and an agonistic anti-CD40 antibody (combined TLR/CD40 immunization) generates an exponentially larger antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response compared to the response elicited by immunization with either agonist alone (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, vaccination with combined TLR/CD40 stimulation results in the development of memory CD8+ T cells that are capable of robust secondary expansion (Fig. 1B), differentiation to effector function, and protection against subsequent infectious challenge (10, 14, 22, 23). While it is clear that the primary CD8+ T cell response to combined TLR/CD40 vaccination is dependent on DC expression of CD70 and its interaction with CD27 on the T cells (Fig. 1C and (10, 13, 14)), we have not yet examined the role of the TNF R/L superfamily in the generation of memory CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cell expansion resulting in robust immune memory has been shown to require stimulation of the T cell via antigen and CD28 (signal 1 and 2) as well as the contribution of various cytokine mediators of a so called “signal 3” (3, 24). Indeed, reductionist approaches to T cell stimulation as well as responses to infectious or tumor challenges have revealed that the absence of an effective cytokine signal 3 mediator renders antigen specific CD8+ T cells incompetent as effectors or memory cells (4, 25–30). The most well studied cytokine signal 3 mediators are IL-12 and IFN, both of which can be induced in the process of combined TLR/CD40 immunization. Previous work established that TLR7/CD40 and TLR2/CD40 combinations could elicit primary CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of IL-12 or type I IFN, respectively(22). However, the influence of either of these cytokines on the production of competent CD8+ T cell memory resulting from any TLR/CD40 combination has never been established. The limited stimuli with which this vaccination elicits such potent CD8+ T cell responses is a significant advantage, compared to the use of infectious agents, for pursuing and establishing the minimal signals required for immune memory formation. We therefore examined the role of IFN and IL-12 in the generation of memory CD8+ T cells in response to combined TLR/CD40 immunization.

Figure 1. CD8+ T cell responses to combined TLR/anti-CD40 agonist immunization.

C57BL/6 mice were immunized i.v. with whole ovalbumin protein (100 µg) with Pam3Cys (25 µg), anti-CD40 antibody (50 µg), or both. A, Seven days after immunization, PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Percentages in each dot plot indicate the percentage of Ag-specific (tetramer-staining) CD8+ T cells of total CD8+ T cells in the blood. B, Magnitude of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion after primary immunization (left panel). Forty-four days post-immunization, mice were infected with 2 × 105 cfu ovalbumin-expressing Listeria monocytogenes, and five days later, spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods (right panel). Values indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained with Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer. C, C57BL/6 mice were immunized as in A. Blocking anti-CD70 antibody (250 µg) was administered i.p. on days -1, 0, 2, and 4 of immunization. Seven days post-immunization, spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the total number of splenic antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as calculated by multiplying the percentage of tetramer-staining CD8+ T cells by the total number of splenic leukocytes. The experiment performed 3 times with a minimum of 3 mice per group, Error bars, SD. *, P< 0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P< 0.005.

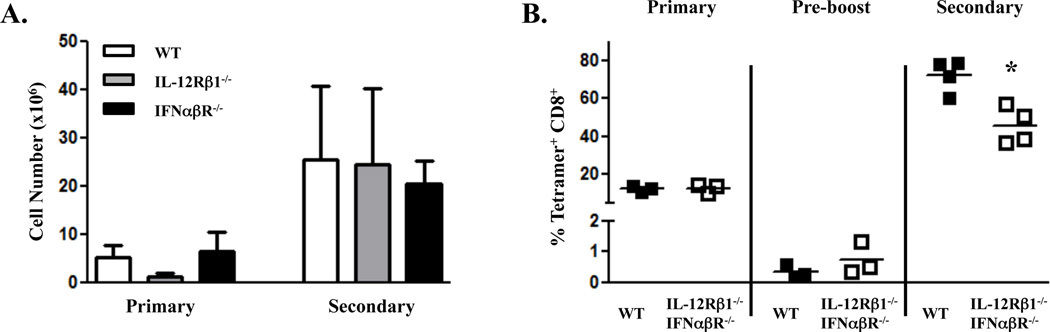

Initially, we immunized wild type (WT), IL-12Rβ1−/−, and IFNαβR−/− mice with OVA protein and combined TLR/CD40 and assessed the development of primary and secondary CD8 T cell responses. While the primary response in the IL-12Rβ1−/− mice was occasionally reduced relative to that seen in the WT or IFNαβR−/− hosts, the expansion of memory CD8+ T cells to secondary challenge in both IL-12Rβ1−/− and IFNαβR−/− mice was similar to wild-type (Fig 2A). These results are similar to those observed in previous studies examining IL-12Rβ1−/− or IFNαβR−/− CD8+ T cells in response to Listeria monocytogenes or Vaccinia virus challenge, respectively (31–33). However, it remained possible that anomalous results were observed in these hosts due to the lack of any IL-12 or IFN signaling throughout development. In addition, it was possible that in the absence of one cytokine receptor, the other was capable of supporting T cell memory formation. To examine both IL-12 and IFN in the presence of WT innate and adaptive cells, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras using congenically marked bone marrow from dual IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− mice (DRKO) and WT mice. Following reconstitution, the mice were immunized with combined TLR/CD40 as described above (Fig. 1) and the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion was monitored by tetramer staining and intracellular cytokine staining. Seven days after immunization, the expansion of the DRKO CD8+ T cells was similar, if not superior to, WT CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2B). We then waited for the development of a pool of memory CD8+ T cells (>40 days), the magnitude of which was not significantly different between WT or DRKO CD8+ T cells (average of 0.34% tetramer+ of WT CD8+ compared to 0.73% tetramer+ of DRKO, p=0.42). The mice were then challenged to determine the degree of secondary expansion of the CD8+ T cell memory pool. Although the secondary expansion by the DRKO CD8+ T cells was statistically lower than that of the WT CD8+ T cells, this difference was less than 2 fold and the magnitude of the secondary expansion of both cell types was still characteristic of a robust memory response (DRKO cells expanding from an average of 0.73% pre-boost to 40–60% post-boost). Memory cells from all mice formed effector responses commensurate with their degree secondary expansion as measured by intracellular IFNγ production (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that combined TLR/CD40 immunization generates primary and secondary CD8+ T cell responses that are largely independent of IL-12 and Type I IFN signals.

Figure 2. CD8+ T cell memory to combined TLR/CD40 immunization is IL-12 and Type I IFN independent.

A, Wild type C57BL/6, IL-12Rβ1−/−, or IFNαβR−/− mice were immunized i.v. with whole ovalbumin protein (100 µg) with Pam3Cys (25 µg) and anti-CD40 antibody (50 µg). Seven days after immunization (Primary), Spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Fifty-four days post-immunization, mice were infected with 2 × 105 cfu ovalbumin-expressing Listeria monocytogenes, and five days later (Secondary), spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the total number of splenic antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as calculated by multiplying the percentage of tetramer-staining CD8+ T cells by the total number of splenic leukocytes. The experiment performed 2 times with 3–4 mice per group. Error bars, SD. B, WT×IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− mixed bone marrow chimeras were immunized i.v. against whole ovalbumin protein (100 µg) with Pam3Cys (25 µg) and anti-CD40 antibody (50 µg). At seven days (Primary) and forty-four days (Pre-boost) post-immunization, mice were bled from the tail vein, and PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were infected with 5 × 105 cfu ovalbumin/B8R-expressing Listeria monocytogenes forty-four days after immunization, and five days later (Secondary), PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained with Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer. Each symbol represents data from a single mouse. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Error bars, SD. *, P< 0.05.

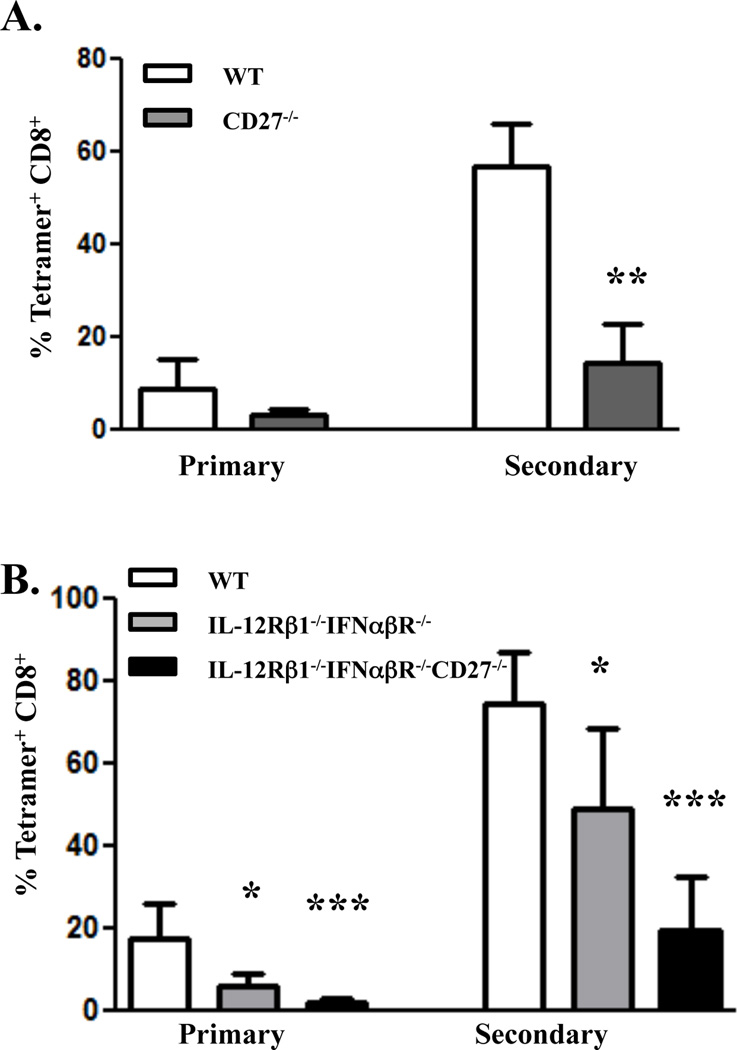

Impairments in TNFR-TNFL Interactions Reduces Memory CD8+ T Cell Responses

We have previously shown that primary CD8+ T cell responses in combined TLR/CD40 immunized mice are inhibited by blocking CD27-CD70 interactions using an anti-CD70 blocking antibody ((10) and Fig. 1C). To characterize the role of CD27 signaling on CD8+ T cell memory in response to combined TLR/CD40 immunization, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras using congenically marked bone marrow from CD27−/− and WT hosts. Following reconstitution (approximately 12 weeks) the mice were immunized with combined TLR/CD40 as described above and the CD8+ T cell response examined as described above. In contrast to the DRKO CD8+ T cells in the WT×IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− chimeras (Fig. 2), the expansion of CD27−/− bone marrow-derived CD8+ T cells was reduced compared to cells of WT origin (Figure 3A). Despite the reduced primary response of the CD27−/− cells, examination of the pool of antigen specific memory CD8+ T cells (>40 days post-priming) showed no significant differences between CD27−/−- and WT-derived CD8+ T cells (0.25% tetramer+ of CD8+ compared to 0.16% tetramer+, respectively, p=0.39, data not shown). However, upon rechallenge, the secondary expansion of the CD27−/− CD8+ T cells was substantially lower than that of WT cells, being reduced by 3–6 fold (Fig 3A). Thus, the response of the CD27−/− cells was far more compromised than the response of IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− CD8+ T cells in the WT×IL-12Rβ1−/− IFNαβR−/− chimeras.

Figure 3. CD27 deficiency attenuates primary and secondary CD8+ T cell immunity in response to combined TLR/CD40 immunization independent of type I IFN or IL-12.

A, WT×CD27−/− mixed bone marrow chimeras were made as described in the Materials and Methods and immunized i.v. against whole ovalbumin protein (100 µg) with Pam3Cys (25 µg) and anti-CD40 antibody (50 µg). At seven days (Primary) post-immunization, mice were bled from the tail vein, and PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were infected with 5 × 105 cfu ovalbumin/B8R-expressing Listeria monocytogenes forty-four days after immunization, and five days later (Secondary), PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars, SD. B. WT (CD45.1)×IL-12Rb1−/−IFNabR−/− (CD45.2)×CD27−/−IL-12Rb1−/−IFNabR−/− (CD45.1/CD45.2) mixed bone marrow chimeras were made and immunized i.v. as described in A. The timing and analysis of primary and secondary CD8+ T cell responses were performed and analyzed as described in A. Values indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained with Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer. The experiment performed 2 times with 3–4 mice per group. Error bars, SD. *, P< 0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P< 0.005.

Closer examination of the data indicated that the cells from the CD27−/− host still underwent an appreciable secondary expansion (~100 fold). While substantially reduced as compared to the WT cells, this degree of secondary expansion was greater than we anticipated, suggesting that other factors/receptors may contribute to the generation and/or programming of the CD8+ T cell response. We initially anticipated that either IFN or IL-12 might be the secondary contributors to the generation of residual T cell memory. We therefore performed experiments using triple bone marrow chimeric mice, reconstituting irradiated B6 mice with a 1:1:1 mixture of bone marrow from WT B6, IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/−, and CD27−/−IL-12Rβ2−/−IFNαβR−/− donors. Following reconstitution, we immunized the mice as described above and examined both primary and secondary responses of the CD8+ T cells derived from each background (Fig. 3B). A number of observations are noteworthy. First, T cells derived from the IL-12Rβ1−/−IFNαβR−/− background responded identically to that shown in Figure 2, displaying a secondary expansion, and IFNγ production (not shown), that was reduced less than 2 fold as compared to WT cell. Second, the only real reduction in CD8+ T cell memory was observed in the cells derived from the CD27−/− bone marrow. Third, the degree to which the CD27−/−IL-12Rβ2−/−IFNαβR−/− was reduced compared to the WT response was largely indistinguishable (3–5 fold) from that seen in the WT×CD27−/− bone marrow chimeras shown in Figure 2. That is, the additional deficit of IL-12R and IFNαR on the responding T cells did not reduce their capacity for secondary response any greater than the absence of CD27 alone. Again, the memory cells from each background formed effector responses (IFNγ production) commensurate with their degree secondary expansion (data not shown). We conclude from these experiments that neither IFNR or IL-12R contribute significantly to the generation of CD8+ T cell immunity in response to combined TLR/CD40 immunization, regardless of the presence or absence of CD27.

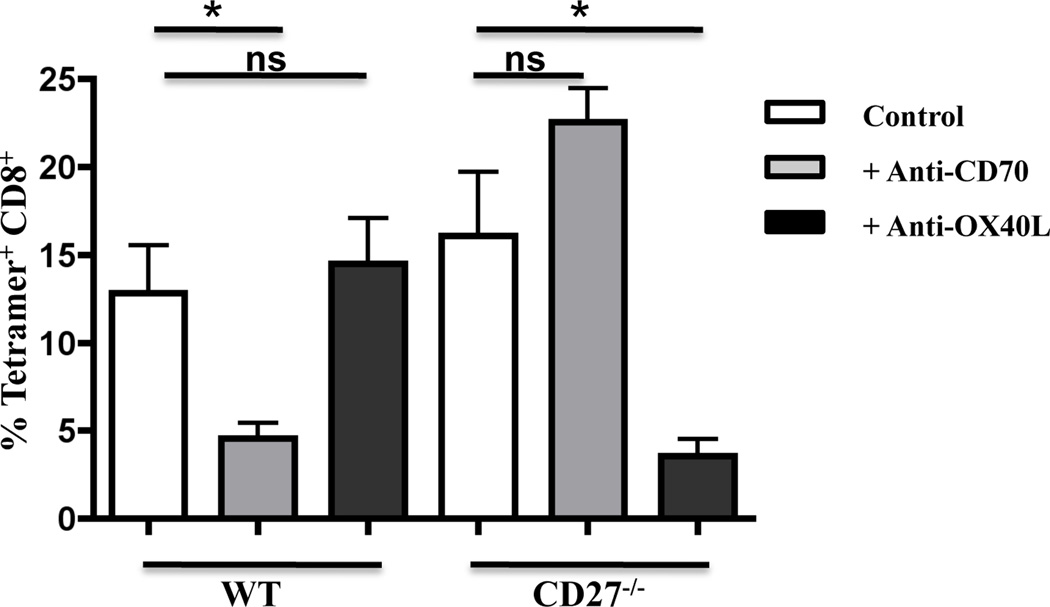

To reiterate, however, while the response of the CD27 deficient cells in the bone marrow chimeras was significantly reduced, it did not achieve the level of ablation seen in the absence of established signal 3 mediators such as IL-12 or IFN in other systems (3, 4, 34). Again our data suggested the participation of another factor in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory from combined TLR/CD40 immunization. In this regard, experiments using the intact CD27−/− hosts in combined TLR/CD40 immunization revealed an interesting contribution of OX40/OX40L interactions to the CD8+ T cell response. In related experiments using combined polyIC/CD40 immunization, we observed that OX-40L blockade, despite having no impact on the response in a WT host reduced the CD8 response in a CD27−/− host similar to the degree to which CD70 blockade reduced the response in the WT host (Fig. 4)(10, 13). Similar data was observed with combined TLR2/CD40 immunization (not shown), and indicate that in the absence of CD27 expression, OX40 contributes significantly to the induction of CD8+ T cell immunity. This finding was perhaps not surprising given i) the similarity in the signaling pathways between the two receptors (35–38), ii) previous reports regarding the cooperativity between TNF receptors in supporting CD8+ T cell memory (9, 15), iii) the well documented importance of OX40 to the formation of T cell immunity in other model systems (11, 39–42), and iv) our previous demonstration that combined TLR/CD40 immunization elicits OX40L expression sufficient for supporting robust CD4+ T cell expansion (13).

Figure 4. The CD8+ T cell response to combined TLR/anti-CD40 agonist immunization in CD27−/− mice is inhibited by anti-OX40L administration.

Wild type C57BL/6 and CD27−/− mice were immunized i.v. against whole ovalbumin protein (100 mg) with PolyIC (50 mg) and anti-CD40 antibody (50 mg). Blocking anti-CD70 or anti-OX40L (clone RM134L, Bioxcell) antibody was administered (250 mg) i.p. on days -1, 0, 2, and 4 of immunization. Seven days post-immunization, PBL were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained with Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer. Each group has 3 mice each, Error bars, SD. This experiment was performed 3 times with similar results.

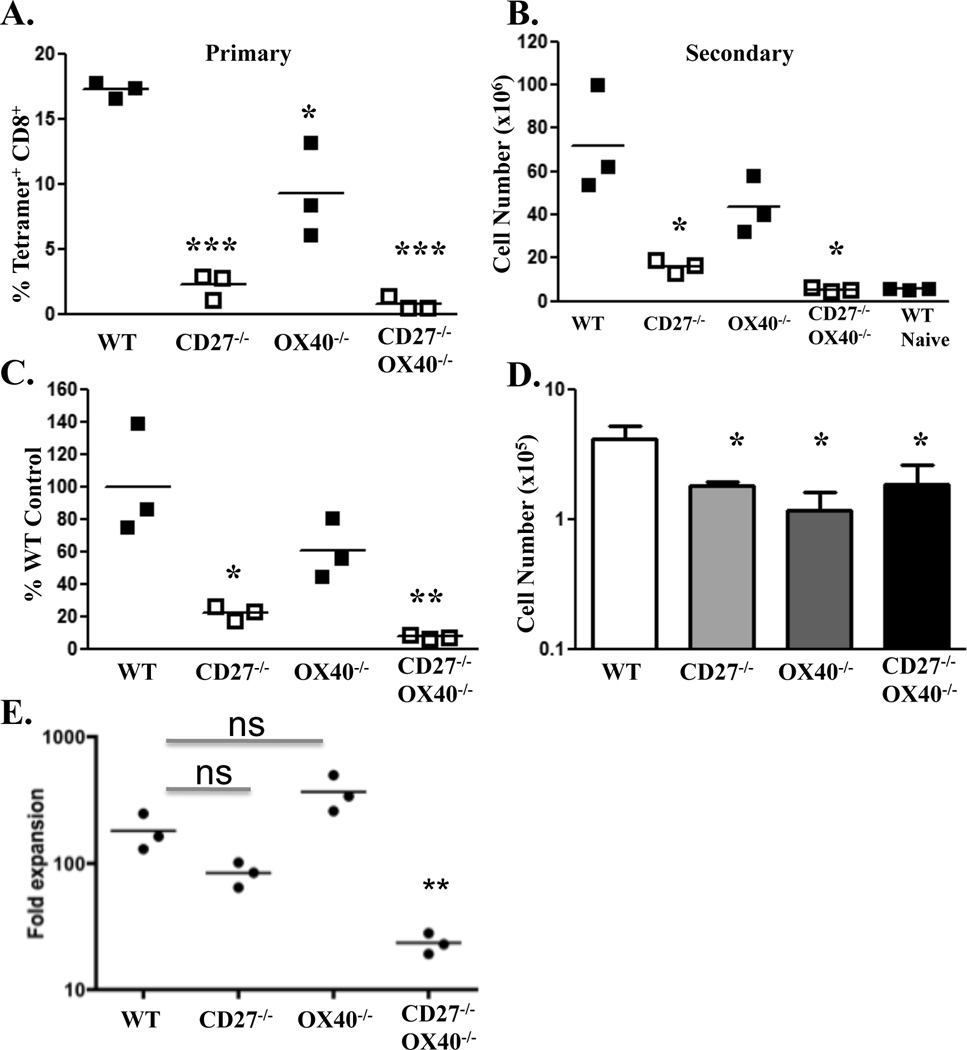

To further examine the potential contribution of OX40-OX40L interactions in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory from combined TLR/CD40 vaccination, we immunized mice that were deficient in CD27, OX40 or both, and again monitored the primary T cell response as described above. The response in the CD27−/− mice was again reduced compared to WT (Fig. 5A). Curiously, even though OX40L blocking antibody has no impact on the CD8+ T cell response in the WT host (10, 13, 14), the response in the OX40−/− hosts was also somewhat reduced, though less so than in the CD27−/−. Further, the primary response in CD27−/−OX40−/− mice was even more reduced than that seen in the CD27−/− hosts, consistent with the observation that OX40 participates in the CD8+ T cell response in the absence of CD27 (10, 13). Upon secondary antigenic challenge, the secondary CD8+ T cell responses in CD27−/− mice were again significantly reduced, though not absent, compared to WT mice, while the responses in the OX40−/− hosts were not statistically different than WT (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the secondary response in the CD27−/−OX40−/− mice was all but absent, being less than even a primary response in a naïve host (Fig. 5B) and representing only a very small fraction of the secondary response as compared to the WT (Fig. 5C). Further, CD27−/−, OX40−/−, and CD27−/−OX40−/− mice had relatively similar CD8+ T cell numbers in the memory pool 4–5 weeks after immunization (Fig. 5D), indicating that the lack of secondary response in the CD27−/−OX40−/− hosts was not due simply to a difference in memory precursors. Using the numbers of antigen specific T cells in each host pre- and post-boost we calculated the fold expansion of the memory cells which revealed two important observations. First, the fold expansion of the memory cells, arguably the best metric for assessing the quality of the memory cell pool, was not statistically different between the WT and the single TNF receptor deficient hosts. Second, the fold expansion of the memory CD27−/− OX40−/− T cells was significantly reduced as compared to the WT or single-deficient counterparts (Fig. 5E). Together, these data indicate that even in the presence of both IFNR and IL-12R, the combined loss of CD27 and OX40 expression can render a host incapable of generating CD8+ T cell memory in response to combined TLR/CD40 immunization. Collectively these data suggest that the non-cytokine signaling mediators CD27 and OX40 can serve as primary signal 3 mediators for CD8+ T cell differentiation and memory generation.

Figure 5. CD27/OX40 serve as signal 3 mediators for CD8+ T cell memory.

Wild type C57BL/6, CD27−/−, OX40−/−, or CD27−/−OX40−/− mice were immunized i.v. against B8R peptide (100 µg) with Pam3Cys (25 µg) and anti-CD40 antibody (50 µg). A. Seven days after immunization, spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells that stained with Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer. B, Mice immunized as in A plus unimmunized wild type C57BL/6 mice (naïve) were infected with 5 × 105 cfu B8R-expressing Listeria monocytogenes forty-four days post-immunization. Five days later, spleen cells were isolated and stained to detect antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Values indicate the calculated total number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen. C, Secondary expansion represented as a percentage of the response observed in wild type mice. Percent of WT values were obtained by dividing the total number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in each mouse by the mean number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from the wild type controls after boost. For dot graphs, each dot represents data collected from a single mouse. D, Number of resting antigen specific memory T cells one day prior to LM boost. Values indicate the calculated total number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen as described in B. E, The degree of expansion of the CD8+ T cell memory pool represented as the fold increase between the numbers of antigen specific cells from pre-boost to post-boost. Values were obtained by dividing the total number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells calculated for each mouse at five days after the secondary challenge by the mean number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells as shown in D. Each dot represents data collected from a single mouse. The horizontal bar represents the mean value of each group. The horizontal bar represents the mean value of each group. This experiment was performed twice, with 3 mice per strain, with similar results. n.s, P>0.05*, P< 0.05; **, P< 0.01; ***, P< 0.005.

Conclusions and Discussion

From the data shown above we conclude that 1) CD8+ T cell memory can be generated in the absence of both type I IFN and IL-12, and 2) in the presence or absence of IL-12/IFN signaling, the TNF receptors (CD27/OX40) can serve the function of signal 3 mediators for the formation of CD8+ T cell memory. These data are novel and important for a number of reasons. First, IL12 and IFN have been shown in a number of model systems to be required for full CD8+ T cell differentiation and memory formation (3, 4, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 43, 44). While the literature is clear on the fact that these cytokines can, and do, serve as signal 3 mediators in many circumstances, our data indicate that a requirement for IL-12/IFN is not applicable to all methods of immunization/vaccination. Given that the induction of these cytokines can be highly variable between different individuals in the population and can even participate in a potentially hazardous “cytokine storm” (45), our demonstration that cell surface TNF-family receptors can replace the need for these cytokines in generating CD8+ T cell immunity may ultimately have significant clinical advantages, particularly in a vaccine setting such as we show here.

Second, important roles for CD27 and OX40 are well established in the generation of CD8+ T cell responses to Listeria monocytogenes (LM), LCMV, VSV, influenza, and vaccinia (5, 6, 13, 15, 46). Indeed, a recent publication demonstrated that CD27/OX40 signaling are the key determinants in the production of protective CD8+ T cell memory against more virulent strains of vaccinia (15). Thus, CD27 and OX40 are important in more responses than just our form of vaccination, perhaps even serving as the major “signal 3” source in one or more of these infectious settings as well.

Third, we believe the data presented here may define an even larger role for CD27 than has been previously appreciated for the purposes of CD8+ T cell memory formation. Previous reports identify CD27 as an important contributor to CD8+ T cell immunity, best studied and demonstrated in response to challenge with influenza. However, while the flu specific CD8+ T cell responses are indeed reduced in the CD27−/− host, they are generally reduced only 2–3 fold in the lymphoid tissues with the major deficit being the trafficking of the cells into the lung (5, 6, 9, 19). These data suggest that either CD27 has less of an impact on the development of CD8+ T cell memory as it does on T cell survival and effector differentiation, or that CD27 deficiency does not necessarily reflect the full impact of the CD27/CD70 pathway. Consistent with the latter, we and others have observed a significant reduction in the CD8+ T cell response to challenge with LM, LCMV, VSV, and vaccinia in the presence of CD70 blockade (13, 15, 46), but no reduction in the response to LM or vaccinia challenge in the CD27−/− host or in CD27−/− cells in WT X CD27−/− bone marrow chimeras (not shown). Our demonstration here that OX40 compensates for the loss of CD27 in a manner not observed in the WT hosts, along with literature reports of similar kinds of compensation between TNF receptor superfamily members (15, 46) calls into question whether simple receptor deficiency on the T cell fully appreciates the role of the given receptor in the development of T cell immunity.

Finally, non-infectious, protein vaccination formulations and/or adjuvants capable of eliciting cellular immunity are difficult to come by and are generally absent from the list of adjuvants currently being investigated for clinical implementation (47). We have demonstrated that 1) combined TLR/CD40 immunization elicits potent expression of CD70 and OX40L on DCs and 2) stimulation through the receptors for these ligands efficiently supports CD8+ T cell immunity. The capacity to use a variety of innate receptor activators (10, 13, 14, 22) indicates the flexibility of this method of vaccination and collectively adds to the necessity for pursuing this vaccine technique in the clinic.

Highlights.

-

1)

CD8+ T cell memory can be produced independent of the signal 3 mediators type I IFN and IL-12.

-

2)

IFN/IL-12 independent T cell memory is compromised in the absence of the TNF receptors CD27 and OX40.

-

3)

CD27/OX40 are non-cytokine signal 3 mediators of CD8+ T cell immunity.

-

3)

Combined TLR/CD40 vaccination elicits IFN/IL-12 independent, CD27/OX40-dependent immunity

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Catherine Haluszczak for helpful lab assistance, Mick Croft at the Lajolla institute of Immunology, San Diego CA for providing the OX40−/− mice, and Jannie Borst at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, for providing the CD27−/− mice. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AI06877, AI066121) and the Department of Defense (W81XWH-07-1-0550). DoD support was associated with funding for the Center for Respiratory Biodefense at National Jewish Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors Disclosure.

R.M.K. is a founder of ImmuRx Inc., a vaccine company whose intellectual property is based on the combined TLR agonist/anti-CD40 immunization platform. R.M.K. and P.J.S. are listed as inventors on patent applications filed by the University of Colorado and licensed by ImmuRx Inc.

References

- 1.Tanchot C, Lemonnier FA, Perarnau B, Freitas AA, Rocha B. Differential requirements for survival and proliferation of CD8 naive or memory T cells. Science. 1997;276:2057–2062. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veiga-Fernandes H, Walter U, Bourgeois C, McLean A, Rocha B. Response of naive and memory CD8+ T cells to antigen stimulation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:47–53. doi: 10.1038/76907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines as a third signal for T cell activation. Current opinion in immunology. 2010;22:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 determines tolerance versus full activation of naive CD8 T cells: dissociating proliferation and development of effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1141–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendriks J, Gravestein LA, Tesselaar K, van Lier RA, Schumacher TN, Borst J. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:433–440. doi: 10.1038/80877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendriks J, Xiao Y, Borst J. CD27 promotes survival of activated T cells and complements CD28 in generation and establishment of the effector T cell pool. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1369–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawicki W, Bertram EM, Sharpe AH, Watts TH. 4-1BB and OX40 act independently to facilitate robust CD8 and CD4 recall responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:5944–5951. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock TN, Yagita H. Induction of CD70 on dendritic cells through CD40 or TLR stimulation contributes to the development of CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:710–717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendriks J, Xiao Y, Rossen JW, van der Sluijs KF, Sugamura K, Ishii N, Borst J. During viral infection of the respiratory tract, CD27, 4-1BB, and OX40 collectively determine formation of CD8+ memory T cells and their capacity for secondary expansion. J Immunol. 2005;175:1665–1676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez PJ, McWilliams JA, Haluszczak C, Yagita H, Kedl RM. Combined TLR/CD40 stimulation mediates potent cellular immunity by regulating dendritic cell expression of CD70 in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:1564–1572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salek-Ardakani S, Moutaftsi M, Crotty S, Sette A, Croft M. OX40 drives protective vaccinia virus-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7969–7976. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller AM, Xiao Y, Peperzak V, Naik SH, Borst J. Costimulatory ligand CD70 allows induction of CD8+ T-cell immunity by immature dendritic cells in a vaccination setting. Blood. 2009;113:5167–5175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurche JS, Burchill MA, Sanchez PJ, Haluszczak C, Kedl RM. Comparison of OX40 ligand and CD70 in the promotion of CD4+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2010;185:2106–2115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McWilliams JA, Sanchez PJ, Haluszczak C, Gapin L, Kedl RM. Multiple innate signaling pathways cooperate with CD40 to induce potent, CD70-dependent cellular immunity. Vaccine. 2010;28:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salek-Ardakani S, Flynn R, Arens R, Yagita H, Smith GL, Borst J, Schoenberger SP, Croft M. The TNFR family members OX40 and CD27 link viral virulence to protective T cell vaccines in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:296–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI42056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croft M. The role of TNF superfamily members in T-cell function and diseases. Nature reviews. 2009;9:271–285. doi: 10.1038/nri2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts TH. TNF/TNFR family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annual review of immunology. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller AM, Schildknecht A, Xiao Y, van den Broek M, Borst J. Expression of costimulatory ligand CD70 on steady-state dendritic cells breaks CD8+ T cell tolerance and permits effective immunity. Immunity. 2008;29:934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peperzak V, Xiao Y, Veraar EA, Borst J. CD27 sustains survival of CTLs in virusinfected nonlymphoid tissue in mice by inducing autocrine IL-2 production. J Clin Invest. 2011;120:168–178. doi: 10.1172/JCI40178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gramaglia I, Jember A, Pippig SD, Weinberg AD, Killeen N, Croft M. The OX40 costimulatory receptor determines the development of CD4 memory by regulating primary clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2000;165:3043–3050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jember AG, Zuberi R, Liu FT, Croft M. Development of allergic inflammation in a murine model of asthma is dependent on the costimulatory receptor OX40. J Exp Med. 2001;193:387–392. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahonen CL, Doxsee CL, McGurran SM, Riter TR, Wade WF, Barth RJ, Vasilakos JP, Noelle RJ, Kedl RM. Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med. 2004;199:775–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahonen CL, Wasiuk A, Fuse S, Turk MJ, Ernstoff MS, Suriawinata AA, Gorham JD, Kedl RM, Usherwood EJ, Noelle RJ. Enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity of multifactorial adjuvants compared with unitary adjuvants as cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008;111:3116–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunological reviews. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aichele P, Unsoeld H, Koschella M, Schweier O, Kalinke U, Vucikuja S. CD8 T cells specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus require type I IFN receptor for clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2006;176:4525–4529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtsinger JM, Gerner MY, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 availability limits the CD8 T cell response to a solid tumor. J Immunol. 2007;178:6752–6760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenzuela J, Schmidt C, Mescher M. The roles of IL-12 in providing a third signal for clonal expansion of naive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6842–6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenzuela JO, Hammerbeck, Mescher MF. Cutting edge: Bcl-3 up-regulation by signal 3 cytokine (IL-12) prolongs survival of antigen-activated CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:600–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearce EL, Shen H. Generation of CD8 T cell memory is regulated by IL-12. J Immunol. 2007;179:2074–2081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson LJ, Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Murali-Krishna K. Innate inflammatory signals induced by various pathogens differentially dictate the IFN-I dependence of CD8 T cells for clonal expansion and memory formation. J Immunol. 2006;177:1746–1754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Z, Casey KA, Jameson SC, Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Programming for CD8 T cell memory development requires IL-12 or type I IFN. J Immunol. 2009;182:2786–2794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curtsinger JM, Johnson CM, Mescher MF. CD8 T cell clonal expansion and development of effector function require prolonged exposure to antigen, costimulation, and signal 3 cytokine. J Immunol. 2003;171:5165–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gravestein LA, Amsen D, Boes M, Calvo CR, Kruisbeek AM, Borst J. The TNF receptor family member CD27 signals to Jun N-terminal kinase via Traf-2. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2208–2216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199807)28:07<2208::AID-IMMU2208>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiba H, Nakano H, Nishinaka S, Shindo M, Kobata T, Atsuta M, Morimoto C, Ware CF, Malinin NL, Wallach D, Yagita H, Okumura K. CD27, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, activates NF-kappaB and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun Nterminal kinase via TRAF2, TRAF5, and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13353–13358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawamata S, Hori T, Imura A, Takaori-Kondo A, Uchiyama T. Activation of OX40 signal transduction pathways leads to tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 2- and TRAF5-mediated NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5808–5814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arch RH, Thompson CB. 4-1BB and Ox40 are members of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-nerve growth factor receptor subfamily that bind TNF receptor-associated factors and activate nuclear factor kappaB. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:558–565. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croft M. Control of immunity by the TNFR-related molecule OX40 (CD134) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;28:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salek-Ardakani S, Flynn R, Arens R, Yagita H, Smith GL, Borst J, Schoenberger SP, Croft M. The TNFR family members OX40 and CD27 link viral virulence to protective T cell vaccines in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;121:296–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI42056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humphreys IR, Loewendorf A, de Trez C, Schneider K, Benedict CA, Munks MW, Ware CF, Croft M. OX40 costimulation promotes persistence of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8 T Cells: A CD4-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2007;179:2195–2202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song A, Tang X, Harms KM, Croft M. OX40 and Bcl-xL promote the persistence of CD8 T cells to recall tumor-associated antigen. J Immunol. 2005;175:3534–3541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hervas-Stubbs S, Riezu-Boj JI, Gonzalez I, Mancheno U, Dubrot J, Azpilicueta A, Gabari I, Palazon A, Aranguren A, Ruiz J, Prieto J, Larrea E, Melero I. Effects of IFN-alpha as a signal-3 cytokine on human naive and antigen-experienced CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:3389–3402. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H, Ma S. The cytokine storm and factors determining the sequence and severity of organ dysfunction in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2008;26:711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schildknecht A, Miescher I, Yagita H, van den Broek M. Priming of CD8+ T cell responses by pathogens typically depends on CD70-mediated interactions with dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:716–728. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity. 2010;33:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]