Abstract

In this work we created electrospun fibrous scaffolds with random and aligned fiber orientations in order to mimic the 3D structure of the natural extracellular matrix (ECM). The rigidity and topography of the ECM environment have been reported to alter cancer cell behavior. But the complexity of the in vivo system makes it difficult to isolate and study such extracellular topographical cues that trigger cancer cells’ response. Breast cancer cells were cultured on these fibrous scaffolds for 3–5 days. The cells showed elongated spindle-like morphology in the aligned fibers whereas kept mostly flat stellar shape in the random fibers. Gene expression profiling of these cells post seeding, showed up-regulation of transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1) along with other mesenchymal biomarkers, suggesting that these cells are undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in response to the polymer scaffold. The results of this study indicate that the topographical cue may play a significant role in tumor progression.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence accumulating from recent literatures makes scientists believe that the biophysical properties of extracellular matrix (ECM) have major impact on cancer cell survival, morphogenesis, invasion, and metastasis.1, 2 During tumor progression ECM components modulate cell phenotype by generating tensional forces within the matrix, or spatial orientation of matrix fibrils.3 Cells respond to these geometric cues by restructuring their cytoskeleton also known as “contact guidance”,4 which is further translated to biochemical signals within a cell, altering its gene and protein expressions. Several studies show that substrate topography can guide differentiation of neural stem cells,5 Schwann cell maturation,6 skeletal muscle constructs7 and restoration of tissue architecture8 through contact cue. Many recent works also reported that cell adhesion to patterned surface depends largely on the surface architecture of the physical patterns.9–11

In the developmental process of tumor metastasis, ECM remodeling occurs where the epithelial cancer cells undergo a phenotypic change to obtain a more migratory, invasive form also known as epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT), promoting directed cell invasion into the vessels.12 However, the complexity of the in vivo system makes it difficult to isolate and study those ECM topographical cues which affect such cellular transitions and behaviors. Therefore it is necessary to employ an in vitro biomimetic scaffold to investigate such cell-matrix interactions. In this paper, we exploit the method of electrospinning to obtain random and aligned poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) fibers and use it as a model to evaluate cell-substrate response.

Electrospinning is a simple and very economical method to produce biomaterials with large surface area, controllable mechanical properties and tunable surface chemistries.13, 14 It is a promising technique in the field of tissue engineering as the non-woven fibrous mats produced in the sub-micron range can mimic structure and topography of the ECM. Among many synthetic polymers that have been used in electrospinning, PCL is known for its excellent biocompatibility and good support for cell growth.13, 15–17 Moreover, the alignment of electrospun fibers can be readily achieved by improved fiber collection method, which has been employed to dictate neuron cells, stem cells, and fibroblast growth by providing contact cue guidance.5, 6, 18–21 Here we report that contact cue can induce the elongation and alignment of a variety of breast cancer cells with aligned PCL fibers as culturing substrates. Furthermore, such morphological change may indicate an EMT-like transition in breast cancer cells, regulated by the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling pathway. Our result implies that the biophysical attributes of tumor microenvironment like ECM alignment may be sufficient to induce the occurrence of EMT in cancer cells.

Experimental Section

Materials

PCL (Average Mn ca. 60 kDa, Sigma), 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluro-2-propanol (HFIP) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. TGFβ-1 was purchased from Stemgent Inc. Deionized (DI) water was produced from a Millipore Purification System (18 MΩ·cm at 25 °C). H605 is a mammary tumor cell line which was isolated from the primary tumor of the MMTV-Her2/neu transgenic mouse as described in our previous publications.22 MTCL and 4T1 cell lines were obtained from Dr. Xiaoming Yang of School of Medicine Columbia, SC. MDA-MB-231 cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Shaojin You from Atlanta VA Medical Center. MCF-7 and NMuMG cell lines were purchased from ATCC.

Electrospinning PCL fibers

PCL was dissolved in HFIP to form a 15% w/w solution. The polymer solution was transferred to a 1 mL syringe connected to a 21G blunt needle (BD precision guide) which was also the positive electrode. The polymer was dispensed using a syringe pump (KD scientific) at a constant flow rate of 15 µL/min in a humidity controlled chamber. A stationary grounded aluminum foil collector was placed at a distance of 15 cm from the tip of the needle for obtaining random fibers. A rotating mandrel was placed at a distance of 10 cm from the tip of the needle and turned at 1000 rpm for collecting aligned fibers. Electrospinning of the polymer was carried out by applying a positive voltage of 6–8 kV employing a high voltage supply (HVR Orlando, FL) between the needle tip and the stationary / rotating collector. The electrospun PCL scaffold was kept overnight on a vacuum dry oven in order to remove residual solvents. PCL fiber scaffold was sterilized by immersing in 70% ethanol for 20 min and following UV irradiation in a laminar flow hood for 20 min.

Cell culture and Seeding

Mouse mammary tumor cell H605,22 mouse mammary epithelial cells (NMuMG), and human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 µg/mL insulin, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. Mouse breast cancer cells 4T1 and MTCL23 were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 was cultured in RPMI 1640 and supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. All cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C. All media components were obtained from Hyclone laboratories Inc. Sterilized PCL fiber scaffold were washed with PBS twice and soaked in media overnight prior cell seeding. Cells at their growth phase of 80% confluency were detached from plate using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and seeded on fiber mat at a density of 1.3 × 104 per cm2 and cultured for 3–5 days. Images of H605 cells were taken at day 5 whereas for 4T1, MDA-MB-231 and MTCL images were taken at 3 days of culture.

TGFβ-1 treatment in culturing H605 cells

H605 cells were seeded to a 12-well plate at a density of 1.3 × 104 per cm2. Cells were maintained in 5 ng/mL (final concentration) of TGFβ-1 in complete medium for one week. Cells were subcultured at 80–90% confluence once in one week.

EMT induction in NMuMG cells

NMuMG cell were seeded at a density of 2.6 × 104 per cm2 on aligned PCL fiber mat. The higher seeding density for NMuMG cells were employed to make sure cell density was still in an appropriate range since the addition of TGFβ-1 would cause cell death and reduce cell number significantly. Twenty four hours post seeding, 5 ng/mL (final concentration) of TGFβ-1 was added to media for EMT induction. Cells on PCL fiber mat without TGFβ-1 treatment was used as a control.

Microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, cells on fiber mat were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Actin cytoskeleton was stained with Rhodamine–phalloidin (Cytoskeleton Inc.) and the nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen). The fluorescence was visualized under microscope (Olympus IX81) with DAPI filter and Cy3 filter set. Signals from the DAPI filter set were assigned blue and those from the Cy3 filter set were assigned green. Mercury lamp was used as a light source. Nucleus orientation analysis was performed for 15–50 cells using ImageJ software, keeping the fiber directionality as the reference point. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), PCL fiber mat were dried with nitrogen, sputter coated with gold for 30 seconds and imaged at 20–25 kV with Zeiss UltraPlus FESEM. Diameter of approximately 10 fibers was calculated with ImageJ software (NIH, USA). Cells on PCL mat were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room temperature. Post-fixation, cells were treated with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 60 min at 4 °C. After washing three times with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, the cell samples were dehydrated in a series of ethanol solution (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%) for 10 min each. The samples were processed though critical point drying apparatus (Ladd Research Industries, Inc.). A thin layer of gold (20 nm) was sputter-coated on the samples and imaged with Zeiss UltraPlus FESEM.

RNA extraction and reverse-transcription qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from H605 cells after 5 days of culture in aligned fibers, random fibers and TCP using RNeasy mini purification kit (Qiagen), and subsequently reverse-transcribed with qScript™cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences Inc.). RT-qPCR was carried out for 45 cycles of PCR (95°C for 15s, 58°C for 15s and 72°C for 30s) with iQ5 SYBR Green supermix (Biorad) using primers indicated in Table 1. In a 25 µL total volume of reaction mixture, 200 nM of both forward and reverse primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc) and the cDNA template at a final concentration of 0.25 ng/µL were employed. Data analysis was performed using 2−ΔΔCT method for relative quantification24 based on three replicate measurements and all samples were normalized to Gapdh expression as the internal control. Statistical analysis on normalized expression was performed using ‘Pair Wise Fixed Reallocation Randomisation Test’ on each sample and a value of p < 0.005 was considered as significant. 25

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-qPCR experiments.

| Gene Name | Forward Sequence 5’-3’ | Reverse Sequence 5’-3’ |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | TGCCGCCTGGAGAAACCTGC | CAGCCCCGGCATCGAAGGTG |

| Ck18 | TCCGCGCCCAGTATGAAGCG | GAGGGTGCGTCTCAGCTCCG |

| Ck14 | CGCCGTCTGCTGGAGGGAGA | GGAGACCACCTTGCCATCGTGC |

| Sma | GGCTCCATCCTGGCTTCGCT | GGAGGCGCTGATCCACAAAACG |

| TGFβ1 | CGGGAAGCAGTGCCCGAACC | GGGGGTCAGCAGCCGGTTAC |

| Snail | ACCTCCCCATCCTCGCTGGC | GGAGGCTCTGGGCGGGTACA |

| Fsp1 | GGCAAGACCCTTGGAGGAGGCC | GAAGCTAGGCAGCTCCCTGGTCA |

| Stat3 | AGGGCTTCTCTGGGGCTGGT | TCTGCAGGCTGGGTGAGGCT |

| Ecadh | CCGGCTAGTTGGCACACCGA | GCAGGCATTGGAGGGGTGCAT |

| Ncadh | GGTGGCCTGGTACTGGCAGC | AGAACGCTGGGGTCAGAGGTGT |

| Smad3 | CCGGCCCCTTTAAGTAACGGCC | CCCCCGTCTGCAATGCCACA |

| Bmp7 | CCACCTTGGCGAGGAGCCAACA | CCGTCACGTGCCAGAAGGAAAGG |

RESULTS

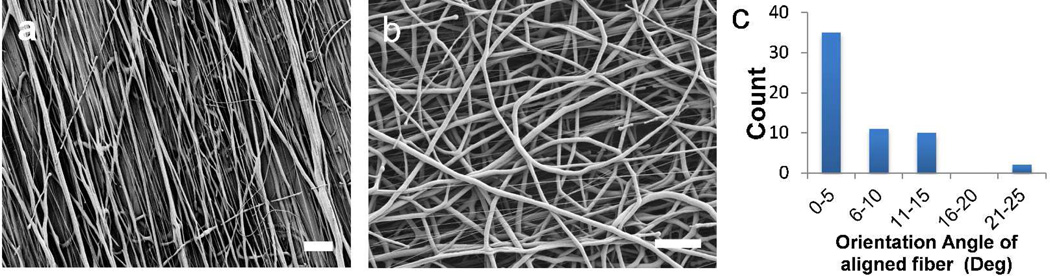

PCL fiber fabrication

Electrospun PCL fibers were readily fabricated using a home-made apparatus. With a stationary collector placed at 15 cm underneath the tip, random fiber mat was obtained and no preferred fiber orientation observed under SEM (Figure 1b). When the collector was replaced with a rotating mandrel, well-oriented fiber mat showed alignment of fibers along the direction of the rotation of the collecting mandrel (Figure 1a). When fibers reach the edge of the rotating collector during electrospinning it is stretched by the tangential force and forms aligned fibers on the collector surface. The solution concentration and solvent have significant effects in the diameter of the fibers as previously reported in literatures.26 Various PCL solution concentrations (9%, 12% and 15%) were used to test the fiber formation. The 15% PCL solution produced homogenous fibers with no beading, which was used in the cell studies. The average fiber diameters for a 15% PCL solution in HFIP for aligned and random fibers were calculated to be 1.8 ± 0.46 µm and 2.0 ± 0.65 µm, respectively. The aligned fibers were produced at a rotation speed of 1000 rpm of the rotating collector. Degree of alignment was calculated by measuring the orientation angles of the fibers with respect to the direction of the rotating collector. More than 75% of the fibers lie within 10 degree to the direction of rotating axis thus, showing good alignment (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

SEM images of 15% PCL electrospun fibers (a) aligned (Mag = 1.28 KX) and (b) random (Mag = 1.64 KX). (c) Plot showing the degree of alignment of the aligned fibers. Scale bar = 20µm.

Cellular response to aligned and random PCL fiber scaffolds

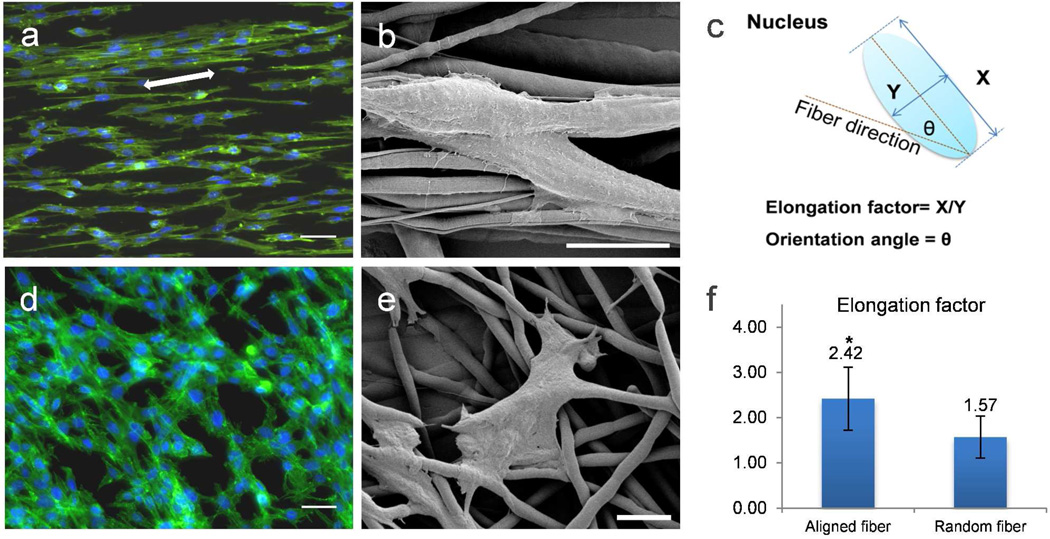

The PCL fiber scaffold was optimized for cell studies. A mammary tumor cell line, H605, which was isolated from the primary tumor of the MMTV-Her2/neu transgenic mouse, was first investigated.22 Due to the high hydrophobicity (Table S1 water contact angle 121.5°) of PCL material, cells attach but do not spread immediately. To promote cell attachment and spreading sterilized PCL fiber scaffold was soaked in media overnight at 37 °C prior to cell seeding.27 No cell death was observed in both random and aligned fiber scaffolds after one day of cell seeding and the increase in cell number upon culturing from 3 days to 5 days suggested cells were viable in the PCL scaffold (data not shown). In literature, electrospun fibrous scaffold with diameter ranging from micrometer to nanometer have not been shown to hinder cell growth.28 Figure 2 shows morphological differences in these cells when cultured on different PCL fiber mats for 5 days. When cells were cultured on aligned fibers, the cytoskeleton and nuclei align and elongate along the fiber axes (Figure 2a, b). Similar phenomenon has been reported with fibroblasts, Schwann cell, and neural stem cells before.5, 6, 21 When cells were cultured on random PCL fiber, its cellular cytoskeleton was stretched to cross multiple fibers (Figure 2d, e). The orientation of the cells related to the fiber scaffold was not dependent on the size of the electrospun fibers but may be specific to certain cell type.28, 29 The cell alignment on different scaffold was evaluated by measuring the nucleus elongation factor and the degree of orientation.4 The nucleus elongation factor of each cell is defined as the ratio of X/Y, where X is the major axis of the nucleus which runs along the aligned fiber direction, and Y is the minor axis of the nucleus, runs perpendicular to X-axis. Longer and thinner, spindle-morphology of cells will give higher elongation factor of nuclei, which normally indicates the tensional effect of the fibers in stretching the actin cytoskeleton of the cells. The angle created between the major axis of cell nucleus (X-axis) and the direction of the aligned fibers represents the orientation angle (Figure 2c). Lower orientation angle indicates better cell alignment along fiber direction. Based on the fluorescence microscopy images of cells on PCL fibers, elongation factors (Figure 2f) and degrees of orientation of at least 50 nuclei were calculated. The average elongation of cells on aligned fibers is shown to be significantly higher than cells on random fibers, while the average of the orientation angle of cells on aligned fibers is 8.5 ± 9.27°, which indicates a very good cell alignment.

Figure 2.

Morphological comparison of primary tumor cell line H605 on aligned and random electrospun PCL fibers after 5 days culture. Fluorescence microscope images of H605 on (a) aligned and (d) random electrospun PCL fibers. White arrow depicts the direction of underlying fibers. Green represents actin cytoskeleton and blue the cell nuclei. Scale bar = 40 µm. SEM images of H605 on (b) aligned (Mag = 8.68 KX) and (e) random (Mag = 2.94 KX) electrospun PCL fiber; scale bar = 20 µm. (c) Schematic illustration of how to determine the elongation factor and the orientation angle of the nucleus. (f) Plot of elongation factors of H605 on aligned and random PCL fibers. Bars correspond to mean ± standard deviation, (*) p < 0.005 obtained from paired student’s t-test.

Response of different types of breast cancer cells on aligned PCL fiber scaffold

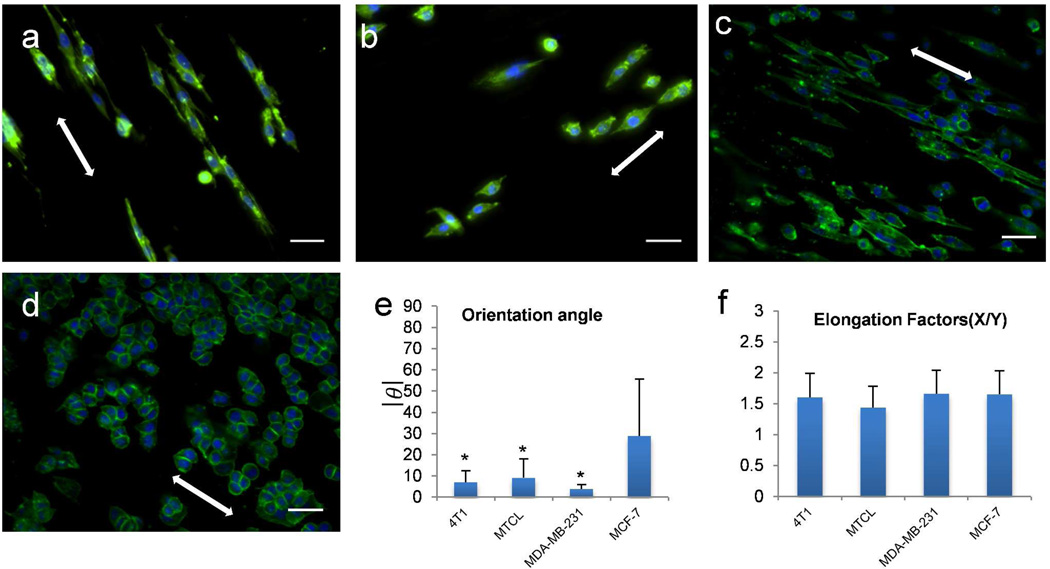

The dramatic change of H605 cell line on different fiber scaffolds inspired us to investigate the effect of other breast cancer cell lines on these scaffolds. We assume cancer cells with different subtype, like, luminal (non-aggressive),30 or basal (aggressive) 31 would behave differently in these aligned fiber mats. To test this hypothesis, we cultured MCF-7 (luminal),30 4T1, MTCL, and MDA-MD-231 (basal)31 on aligned PCL fiber mat for 3 days. The breast cancer cell lines with basal phenotype showed similar morphology on aligned fibers, where the cytoskeleton and nuclei of individual cells aligned and elongated along the fiber axis (Figure 3a–c). In contrast, the luminal-type cell line MCF-7 maintained cell-cell contacts showing less impact of the aligned fibers on the cells (Figure 3d). Average orientation angle of basal type cells are lower than 10°, which indicates good alignment with the fibers. As comparison, the orientation angle of MCF-7 is much higher than the other three (Figure 3e), indicating a random orientation of MCF-7 on aligned fibers. All four breast cancer cell lines showed random orientation when cultured on tissue culture plastic (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Response of four different breast cancer cell lines on aligned PCL fibers: (a) 4T1, (b) MTCL, (c) MDA-MB-231, and (d) MCF-7. Cells were cultured on PCL fibers for 3 days. Green represents actin cytoskeleton and blue the nuclei of a cell, scale bar = 40 µm. All the images are obtained by using 20× Objective. White arrow indicates the fiber directionality. Elongation factors (e) and degree of orientation (f) of all cell lines were calculated using methods showing in Figure 2c. Bars correspond to mean ± standard deviation, (*) p < 0.005 obtained from paired student’s t-test represents significant difference in orientation angle in 4T1, MTCL, MDMBA-231 in comparison to MCF-7.

PCL fiber induced EMT-like phenotype

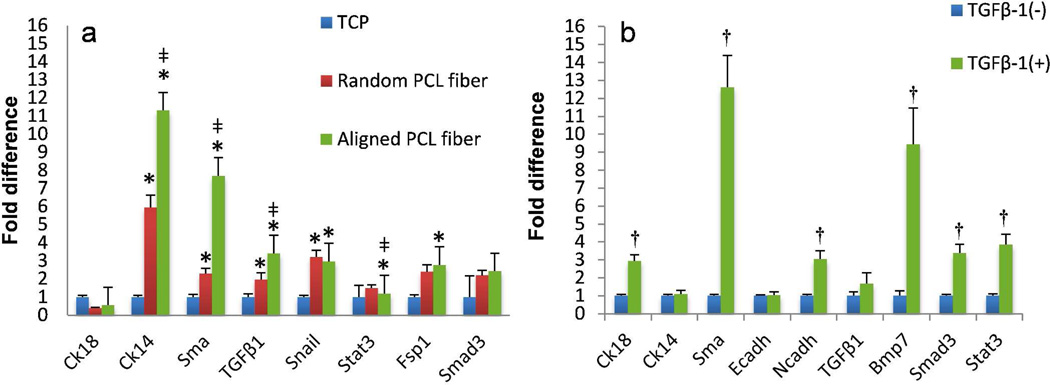

Real time PCR was performed on H605 cells after 5 days of culture on random and aligned fibers, keeping H605 on tissue culture plates as control. Gene expression analysis of cells on aligned fibers showed, significant upregulation of Cytokeratin 14 (Ck14), Smooth muscle actin (Sma), TGFβ-1 (Tgfb1), Snail, Fibroblast specific protein-1 (Fsp1) and Smad3 (Figure 4a). Similar gene expression pattern with less fold difference was observed in the cells cultured on random PCL fibers. Upregulation of Smad3 (downstream of TGFβ-1) suggests the cellular signaling by the TGFβ pathway.32 TGFβ-1 and Snail are well-known EMT inducers,33, 34 therefore higher expression of these genes shows that the cells are undergoing EMT like transitions. Ck14 has been known to be activated in basal like breast cancer cells, with enhanced migratory and invasive phenotype.35 We hypothesize that the increase in the Ck14 indicates that H605 is undergoing more aggressive and motile phenotype. Sma and Fsp1 have been well reported as EMT markers in fibroblasts and epithelial cells thus increased expression of these genes also highlights the EMT like phenotype.36 According to Zeisberg et al, there exist 3 types of EMT, i.e. Type-1 (mesenchymal), Type-2 (fibroblast), and Type-3 (metastatic).37 Enhanced upregulation of cytoskeletal markers like Ck14, Sma, Fsp1 and transcriptional factors like Snail clearly indicates that H605 on aligned fibers are undergoing Type-3 EMT in comparison to H605 on random fibers and in control experiments. However, cell surface proteins like Fibronectin, N-cadherin (Ncadh) and E-cadherin (Ecadh) did not show significant changes in the gene profile (data not shown), possibly because these cells had been cultured on the fibers for a relatively shorter period of time. More importantly, chemical induction in H605 with TGFβ-1 also showed similar gene expression pattern with upregulation of Bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp7), Ncadh, Smad3 and Sma, corroborating our hypothesis that Type-3 EMT on PCL fibers was induced via the TGFβ pathway (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Comparison of gene expression profiles by RT-qPCR. (a) H605 cells cultured on different substrates: tissue culture plate (TCP), random PCL fibers, and aligned PCL fibers. (b) H605 cells with or without TGFβ-1 treatment. The gene expressions were normalized using Gapdh as the housekeeping gene. (*) p < 0.005 obtained from ‘pair wise fixed reallocation randomisation test’ represents significant difference between cells on TCP control with random or aligned fibers (a), (‡) p < 0.005 represents significant difference between cells on random and aligned fibers. (†) p < 0.005 represents significant difference between TGFβ-1 treated and untreated cells (b).

EMT in tumor environment is thought to be a force dependent phenomenon.38 Dynamic compression and contraction of cell-matrix interaction leads to the activation of latent ECM bound TGFβ, which thereafter stimulates a feedback loop to induce EMT in the cell itself.36 Cell alignment along the fibers can be explained, considering the mechanical strength of the fibers stretching the cytoskeleton of the cell, giving rise to torsion and tensional forces which further induce actomyosin reorganization and result in a change in cell shape.4, 38 These conformational changes in the cells can influence the biochemical signaling cascade within the cell by integrin clustering. Thus we can conclude that, contact cue guidance of the cells, giving spindle morphology along the fibers, may induce EMT like phenotype through the TGFβ pathway.

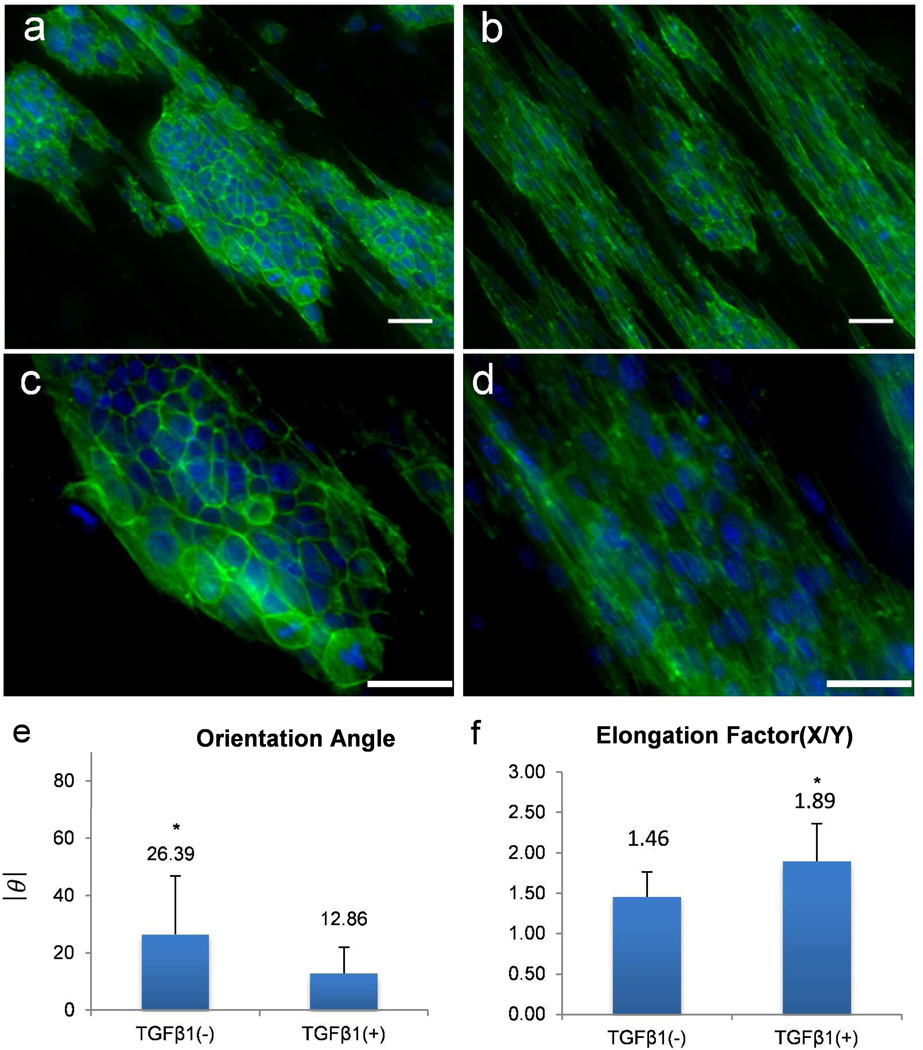

To further confirm the correlation between cell alignment and EMT-like phenotype, a well-studied inducible EMT model was tested with mouse mammary epithelial cell line (NMuMG) on aligned PCL fibers. TGFβ-1 has been shown to induce epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in NMuMG cells.39 Without any treatment, these cells exhibit typical epithelial cell morphology having compact colonies on the aligned fibers. Although the cells on the exterior of the colonies showed partial alignment with the fibers, cells in the interior of the colonies showed strong resistance to align and maintained their cuboidal and clustered morphology (Figure 5a). Upon TGFβ-1 treatment, NMuMG cells are malleable to response to the contact cue given by the aligned fiber mat and appear spindle shaped and elongated (Figure 5b, c). These morphological changes are classic features of EMT.40 Consistent with this observation, rearrangement of cytoskeleton as a signature of the transition was observed by phalloidin staining. The control cells without TGFβ-1 treatment exhibited a peripheral F-actin staining with slim central stress fibers, while the cells with TGFβ-1 treatment showed a decrease in marginal F-actin but contained much thicker central stress fiber (Figure 5a, b). Besides the induced morphological changes and cytoskeleton rearrangement, cells located both in the interior and exterior of the colonies showed good alignment along fiber direction with average orientation angle of 12.86° (Figure 5b, d). This observation suggests that the EMT-like changes are at least partially induced by the contact cues.

Figure 5.

TGFβ-1 induced elongation of NMuMG cells on aligned PCL fibers. Fluorescence microscope images of NMuMG cells on aligned PCL fibers: (a) and (c) (20×) without TGFβ-1 treatment, and (b) and (d) (40×) with TGFβ-1 treatment for 24 hours. Green represents actin cytoskeleton and blue the nuclei of a cell, scale bar = 40 µm. White arrows depict the direction of underlying fibers. Degree of orientation (c) and elongation factors (d) were calculated using methods showing in Figure 2c. Bars correspond to mean ± standard deviation, (*) p < 0.005 obtained from paired student’s t-test represents significant difference between TGFβ-1 treated and untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, two types of PCL fiber mat with different orientations were fabricated by electrospinning technique to study the influence of contact cue guidance on breast cancer cell behavior. Different morphology of primary tumor cell line H605 was observed when it was cultured on fiber mat with different orientations. H605 showed spindle-like shape on aligned fiber and stellar-like shape on random fiber. After testing four more cell lines, we observed only the breast cancer cell lines which have basal-like phenotype show spindle-like morphology on aligned fiber. Several Type-3 EMT 36,37 related genes were up-regulated when H605 were cultured on aligned PCL fibers. Increase of cell tension due to cell alignment may cause the up-regulation of TGFβ-1 which further promotes EMT-like phenotype. This assumption was further confirmed by gene expression analysis and TGFβ-1 treatment of H605 and NMuMG. This work provided a useful in vitro model to study the interplay between extra cellular matrix and cancer cell during tumor progression.

A parallel fiber alignment was observed previously as a characteristic of ECM produced by primary carcinoma associated fibroblasts of the skin.41 However, the consequence of this fiber arrangement for tumor cell behavior was unknown. Our study identifies ECM architecture as a direct inducer of EMT suggesting that the biophysical attributes of tumor microenvironment may play a critical role in cancer progression. The parallel fiber architecture is reminiscent of the collagen fiber signature identified in the transgenic Wnt-1 mouse mammary tumor model by Provenzano and colleagues.42 This group identified parallel collagen fibers perpendicular to the advancing edge of the tumors. Interestingly, local cell invasion was found predominantly to be oriented along certain aligned collagen fibers, suggesting that radial alignment of collagen fibers relative to tumors facilitates invasion. Because of the inherent limitations of the model system, it was not clear whether the invasion was a consequence or cause of the fiber arrangement. Our data clearly demonstrate that ECM alignment can directly induce EMT-like phenotype, which is known to be a critical step in the tumor invasion and metastasis.

Evidence supporting the importance of the biophysical attributes of the ECM for breast carcinoma cell behavior is accumulating. Besides ECM architectures, dense rigid physical properties are also known to suppress tubulogenesis and stimulate invasion of well differentiated breast carcinoma cells.43 Due to the lack of a good system to mimic the in vivo tumor microenvironment, the contribution of individual microenvironmental cues to tumor initiation and progression remains largely unknown. The electrospun fibers used in our study have similar dimensions to ECM fibers in natural tissue matrix and various fiber attributes in a spatial arrangement that correspond with normal tissue structure in vivo. Most importantly, they are amenable to modulation of the mechanical properties by co-spinning with biopolymers and to the integration of defined ECM ligands and bioactive environmental materials thus provide an ideal model system to assess 3D matrix effects on breast carcinoma cell behavior. This study provides proof-of-principle experiments demonstrating that this model system can be used to address the contribution of microenvironmental cues to tumor progression, which is otherwise difficult to be evaluated due to the complexity of cancer cell-microenvironment interaction in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of this work by NIH grant (3P20RR017698-08) to HC and QW, and the American Cancer Society Research Award (RSG-10-067-01-TBE) to HC. QW would also acknowledge the support from the US NSF CHE-0748690, the Alfred P. Sloan Scholarship, the Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar Award, and the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors also like to thank Dr. Xiaoming Yang and Dr. Shaojin You for providing us with cell lines. The authors are grateful to the reviewers of this paper for many helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Yu H, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinman HK, Philp D, Hoffman MP. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2003;14:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen M, Artym VV, Green JA, Yamada KM. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2006;18:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang X, Takayama S, Qian X, Ostuni E, Wu H, Bowden N, LeDuc P, Ingber DE, Whitesides GM. Langmuir. 2002;18:3273–3280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim SH, Liu XY, Song H, Yarema KJ, Mao HQ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9031–9039. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Itoh S, Konno K, Kikkawa T, Ichinose S, Sakai K, Ohkuma T, Watabe K. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;91:994–1005. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Zeng H, Nam J, Agarwal S. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009;102:624–631. doi: 10.1002/bit.22080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoehme S, Brulport M, Bauer A, Bedawy E, Schormann W, Hermes M, Puppe V, Gebhardt R, Zellmer S, Schwarz M, Bockamp E, Timmel T, Hengstler JG, Drasdo D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:10371–10376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909374107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu Y, Sun J, Shen J. Langmuir. 2008;24:8050–8055. doi: 10.1021/la800998n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rong J, Lee LA, Li K, Harp B, Mello CM, Niu Z, Wang Q. Chem. Comm. 2008:5185–5187. doi: 10.1039/b811039e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Lee LA, Niu Z, Ghoshroy S, Wang Q. Langmuir. 2011;27:9490–9496. doi: 10.1021/la201580v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiseman BS, Werb Z. Science. 2002;296:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.1067431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal S, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3343–3351. doi: 10.1002/adma.200803092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Zang J, Lee LA, Niu Z, Horvatha GC, Braxtona V, Wibowo AC, Bruckman MA, Ghoshroy S, zur Loye H-C, Li X, Wang Q. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:8550–8557. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:1392–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1197–1211. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson MR, Coombes AG. Biomaterials. 2004;25:459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker BM, Mauck RL. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1967–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnell E, Klinkhammer K, Balzer S, Brook G, Klee D, Dalton P, Mey J. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3012–3025. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nathan AS, Baker BM, Nerurkar NL, Mauck RL. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CH, Shin HJ, Cho IH, Kang YM, Kim IA, Park KD, Shin JW. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1261–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo PK, Kanojia D, Liu X, Singh UP, Berger FG, Wang Q, Chen H. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You S, Li WEI, Kobayashi M, Xiong YIN, Hrushesky W, Wood P. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Animal. 2004;40:187–195. doi: 10.1290/1543-706X(2004)40<187:COASMT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1197–1211. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khil M-S, Bhattarai SR, Kim H-Y, Kim S-Z, Lee K-H. J. Biomed. Mat. Res Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2005;72B:117–124. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bashur CA, Dahlgren LA, Goldstein AS. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5681–5688. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bashur CA, Shaffer RD, Dahlgren LA, Guelcher SA, Goldstein AS. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2009;15:2435–2445. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Saleh S, Al Mulla F, Luqmani YA. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mani SA, Yang J, Brooks M, Schwaninger G, Zhou A, Miura N, Kutok JL, Hartwell K, Richardson AL, Weinberg RA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10069–10074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakao A, Imamura T, Souchelnytskyi S, Kawabata M, Ishisaki A, Oeda E, Tamaki K, Hanai J-i, Heldin C-H, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. EMBO J. 1997;16:5353–5362. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zavadil J, Bottinger EP. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–5774. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Wang H, Wang F, Gu Q, Xu X. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laakso M, Loman N, Borg A, Isola J. Mod. Pathol. 2005;18:1321–1328. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wipff P-J, Rifkin DB, Meister J-J, Hinz B. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:1311–1323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez JI, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. Oncogene. 2008;27:6981–6993. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Netherton SJ, Bonni S. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guarino M, Rubino B, Ballabio G. Pathology. 2007;39:305–318. doi: 10.1080/00313020701329914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amatangelo MD, Bassi DE, Klein-Szanto AJ, Cukierman E. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:475–488. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62991-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ. BMC Med. 2006;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wozniak MA, Desai R, Solski PA, Der CJ, Keely PJ. J. Cell. Biol. 2003;163:583–595. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.