Abstract

Melanoma appears to be heterogeneous in terms of its molecular biology, etiology, and epidemiology. We previously reported that the expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) in melanoma tumor cells is strongly correlated with poor patient survival. Therefore, we hypothesized that nitric oxide (NO) produced by iNOS promotes the melanoma inflammatory tumor microenvironment associated with poor outcome. To understand the role of NO and iNOS in the melanoma inflammatory tumor microenvironment, PCR arrays of inflammatory and autoimmunity genes were performed on a series of stage III melanoma lymph node metastasis samples to compare the gene expression profiles of iNOS-expressing and non-expressing tumor samples. The results indicate that expression of CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) was inversely correlated with iNOS expression, and the high CXCL10–expressing cases had more favorable prognoses than the low CXCL10–expressing cases. Functional studies revealed that treating iNOS-negative/CXCL10-positive melanoma cell lines with a NO donor suppressed the expression of CXCL10. Furthermore, scavenging NO from iNOS-expressing cell lines significantly affected the chemokine expression profile. Culture supernatants from NO scavenger–treated melanoma cells promoted the migration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which was diminished when the cells were treated with a CXCL10-neutralizing antibody. CXCL10 has been reported to be an antitumorigenic chemokine. Our study suggests that production of NO by iNOS inhibits the expression of CXCL10 in melanoma cells and leads to a protumorigenic tumor microenvironment. Inhibiting NO induces an antitumorigenic environment, and thus, iNOS should be considered to be an important therapeutic target in melanoma.

Keywords: CXCL10, nitric oxide, melanoma, molecular signature, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer and exhibits extremely aggressive growth characteristics. The incidence and mortality due to melanoma continue to increase in the US, with more than a 600-fold increase in the incidence and a 15-fold increase in the number of deaths since 1950, as documented by the American Cancer Society. Only 20% of patients with visceral metastasis live beyond 5 years, and early detection with surgical excision are the only reliable means of control.1

Increasing evidence suggests that melanoma is a heterogeneous disease in terms of response to therapy, etiology, tumor mutational status, and survival of patients with advanced disease.2–4 Our previous studies showed that the expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) in melanoma tumor cells after combination biochemotherapy (P < 0.001) strongly correlates with poor patient survival and can be detected in at least 60% of patients’ tumors.5, 6 In this study, however, we showed that melanoma cells from 12 of 20 tumors express iNOS, yet the expression of this molecule in the tumor did not correlate with pathologic or clinical response to therapy.

Nitric-oxide (NO) is generated as a reaction product of the enzymatic conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by three isotypes of NO synthases (NOSs): endothelial (eNOS), neuronal (nNOS), and inducible (iNOS). NOSs are expressed in various tissue types: eNOS and nNOS are typically considered to be constitutively expressed, whereas iNOS, as its name implies, is inducible.7 NO is involved in neurotransmission, vasodilation, inflammation, and immunity8 and is also believed to play roles in multiple stages of various cancers.9 In fact, a recent study showed that increased iNOS expression is a signature of inferior survival, in estrogen receptor α–negative breast tumors and exposure of estrogen receptor–negative cells to NO enhanced cell motility and invasion.10 Based on these facts, we hypothesized that NO produced by iNOS is a key molecule in the melanoma inflammatory tumor microenvironment and a predictor of poor outcome.

To gain further insight into the role of NO and iNOS in the melanoma inflammatory tumor microenvironment, we performed an inflammatory and autoimmunity gene polymerase chain reaction (PCR) array on a series of stage III melanoma lymph node metastasis samples to compare the gene expression profile directly between iNOS-positive and iNOS-negative tumor samples. We found that the group with the most favorable prognosis showed significant expression of CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10). CXCL10 was initially identified as a chemokine that is induced by interferon gamma (IFN)-γ and secreted by various cell types, including monocytes, neutrophils, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, fibroblasts, mesenchymal cells, dendritic cells, and astrocytes.11 It binds to its receptor, CXCR3, as well as CXCL9 and CXCL11, and regulates immune responses by recruiting CD8+ T cells, eosinophils, monocytes, natural killer cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs).12–15 In addition, CXCL10 is considered as an angiostatic protein, antagonizing the activities of angiogenic factors.16, 17

This study reports that CXCL10 expression is upregulated in iNOS-negative tumor samples. Furthermore, in vitro experiments indicate that NO suppresses the expression of CXCL10 in iNOS-negative melanoma cell lines and scavenging NO from iNOS-positive cell lines changes the chemokine expression pattern, including expression of CXCL10. The culture supernatants of NO-scavenged iNOS-expressing cells promoted the migration of pDCs, mainly because of the expression of CXCL10, suggesting that scavenging NO may alter the inflammatory tumor microenvironment of melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Patients and melanoma samples

This study was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and was conducted in compliance with HIPAA regulations. Only patients for whom tumor material was identified as available in our Melanoma Informatics, Tissue Resource and Pathology Core, and for whom survival and other American Joint Committee on Cancer prognostic data were considered reliable to be included. Eligibility for inclusion in the study included a diagnosis of stage III melanoma, and the availability of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) metastatic tumor tissue from which the stage III diagnosis was made, and iNOS expression previously determined.5, 6 The following information was gathered from the medical records of study subjects: gender; age at melanoma diagnosis; date of stage III diagnosis, defined as the date of pathologic confirmation; administration of adjuvant interferon; features known to influence the survival of patients with stage III melanoma, including the number of positive lymph nodes, macroscopic vs. microscopic disease, the presence or absence of in-transit disease, and ulceration of the primary tumor; and the date and cause of death or date of last follow-up. Patient follow-up and survival data were last updated in December 2010.

Cell culture and reagents

We obtained three metastatic melanoma cell lines, A375, SB2, and WM1727A, from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Normal human pDCs were obtained from MatTek Corporation (Ashland, MA) and cultured in the manufacturer’s DC-MM growth medium according to their instructions. The melanoma cell lines used in this study were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 mg/mL of streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine (all from Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY). Each cell line was cultured to 50%–60% confluence a day before the start of the experiment. The NO scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO) and NO donor s-nitroso-n-acetyl-l,l-penicillamine (SNAP) and 3-Morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) were obtained from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA) and diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide. Human CXCL10 recombinant protein was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat DNA fingerprinting using the AmpF/STR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA; cat 4322288) and analysis was performed by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Characterized Cell Line Core. The short tandem repeat profiles were compared to known ATCC fingerprints (ATCC.org) and the Cell Line Integrated Molecular Authenication database (CLIMA), version 0.1.200808 (http://bioinformatics.istge.it/clima/; Nucleic Acids Research 37:D925–D932 PMCID: PMC2686526).

PCR arrays of inflammatory response and autoimmunity genes

A PCR-based microarray was performed using the RT2-Profiler PCR Array (SABioscience, Frederick, MD). The array (PAHS-077) is configured in a 96-well plate consisting of a focused panel of 84 gene-specific primer sets, along with primers for five housekeeping genes and assay controls. We also customized another set of arrays containing 76 other inflammatory-related gene–specific primer sets; thus 160 genes were analyzed. Briefly, total RNA was isolated using the RT2 FFPE RNA Extraction Kit (SABioscience) from the FFPE melanoma samples and then, converted to first-strand cDNA and pre-amplified using the RT2 FFPE PreAmp cDNA Synthesis Kit (SABioscience). Next, pre-amplified cDNA was added to an RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (SABioscience) and added to the array plates. Real-time PCR was carried out using a Mastercycler ep realplex real-time PCR system (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The amplification data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Statistics were performed with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test using the web-based PCR array data analysis software available from SABioscience and also confirmed using Microsoft Excel software (Analysis ToolPak for Microsoft Excel, 2003).

Immunohistochemical analysis

FFPE sections of melanoma tumor samples and acetone-fixed cytospin sections of melanoma cell line samples were examined for iNOS, CXCL10, and CXCL9 expression by immunohistochemical analysis using a mouse anti-iNOS monoclonal antibody created at Creative Biolabs (Shirley, NY), a goat anti-CXCL10 polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems), and a mouse anti-CXCL9 monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems). Pre-immune normal mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and anti-vimentin antibody (BioGenex Laboratories, San Ramon, CA) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Antigen detection was performed using avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) kit (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories) and immunolabeling was developed with the chromogen 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole.

Immunolabeling was scored separately for two variables; first, for number of positive melanoma cells; second, for the overall intensity of immunoreactivity of the positive cells.5–6 Briefly, scoring for number of positive tumor cells was defined as follows: “0”, less than 5% positive cells; “1”, 5–25% positive cells; “2”, >25–75% positive cells; and “3”, greater than 75% positive cells. Intensity scoring was defined as follows; “0”, no staining; “1”, light staining; “2”, moderate staining; and “3”, intense staining. The slides were independently interpreted by two readers without knowledge of the clinical data. Any discrepancies in scores were subsequently reconciled.

Extraction of RNA from cultured cells and real-time PCR analysis

RNA samples were isolated from cultured cells using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion) to remove genomic DNA, and then converted to first-strand cDNA by random priming using a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR) analysis was carried out on a Mastercycler ep realplex real-time PCR system (Eppendorf) using RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (SABioscience). The primer sequences used for the qRT-PCR studies are as follows: CXCL10 sense, 5′-GAAATTATTCCTGCAAGCCAATTT-3′ and antisense, 5′-TCACCCTTCTTTTTCATGTAGCA-3′ 18; CXCL9 sense, 5′-CCAAGGGACTATCCACCTACAATC-3′; and antisense, 5′-GGTTTAGACATGTTTGAACTCCATTC-3′ 19; and GAPDH sense, 5′-TGGGTGTGAACCATGAGAAG-3′, and antisense, 5′-GCTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGC-3′. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. Fold-induction values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blotting and measurement of the CXCL10 concentration

Goat anti-CXCL10 polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems), Goat anti-Actin antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and 1:1000 horseradish peroxidase–labeled anti-goat antibody (DAKO) were used. Amersham ECL western blot detection reagent (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used to detect protein expression, and data were captured by exposure to Kodak BioMax Light film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The concentration of CXCL10 in the culture supernatant was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a Single Analyte ELISArray kit (SABiosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The focused protein array

The culture supernatants from cPTIO-treated and untreated melanoma cells were collected 48 hours after treatment. A human cytokine array panel A array kit (Proteome Profiler, R&D Systems) was used to measure the chemokine levels in the supernatants according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Positive controls were located in the upper left-hand corner, lower left-hand corner, and lower right-hand corner of each array kit. Amersham ECL Western blot detection reagent (GE Healthcare) was used to detect protein expression, and data were captured by exposure to Kodak BioMax Light film (Eastman Kodak). Arrays were scanned using a computer scanner and spot optical densities were quantified with Image Quant TL Software (GE Healthcare). The relative expression level of each protein was calculated by dividing the spot density of each protein by the mean spot density of the controls.

MTT Assay

The amount of viable cells were examined with the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazoliumbromide (MTT) assay. The cell culture medium was removed, and serum-free medium containing 1 mg/ml MTT was added to the cells. After 3-hour incubation, medium was removed and the formazan product was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance at 570 nM and 630 nM of this solution was measured in a spectrophotometer. Then, the absorbance at 570 nM was subtracted from the absorbance at 630 nM. The cell survival rate was calculated by optical density reading of cells given a treatment divided with the optical density reading of the untreated control cells.

Cell migration assays

Cell migration was examined with a QCM Chemotaxis Cell Migration Assay, 96-well (5 μm) kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 2 × 105 pDCs/well were plated in DC-MM medium in the top wells of the Boyden chambers. The culture supernatants of melanoma cells, treated with or without reagents were plated in the bottom wells. After 4-hour incubation at 37°C, the cells that had migrated were lysed and quantified using the fluorescent dye CyQuant GR Dye (Chemicon). The cell migration was assessed using a fluorescent plate reader, with a 480/520-nm filter set. The number of cells that migrated was estimated by calculating the ratio between the fluorescence intensity of the migrated cells and the fluorescence intensity of 2 × 105 pDCs. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

The objective of the statistical analysis was to simultaneously assess the prognostic effects of melanoma tumor CXCL10 expression, gender, age at melanoma diagnosis, and number of nodes in regard to overall survival (OS). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compute survival in months from the date of stage III diagnosis to the date of death (for patients who died) or to the date of last follow-up (for those still alive). For OS, censored patients included only those remaining alive at last follow-up. The χ2 exact trend test was utilized to compare patient characteristics for discrete categorical variables or factors between groups. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the prognostic effects for each of the previous defined factors. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistically significant differences of in the in vitro analyses were determined by Student’s t-test. All analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute) and S-PLUS software.20, 21

Results

Patient characteristics

A summary of the patient characteristics is given in Table 1. The study included 16 patients with stage III melanoma, 8 of whom had iNOS-positive tumors and 8 of whom had iNOS-negative tumors. The median age at diagnosis was 54 years (range, 32–73) for iNOS-positive patients and 47 years (range, 29–53) for iNOS-negative patients. 50% of patients were male and 50% were female in each group. All patients whose tumors were iNOS positive died of their disease within 5 years, and all patients with iNOS-negative tumors were still alive more than 90 months after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Summary of the cases analyzed in this study.

| iNOS positive (N=8) | iNOS negative (N=8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) |

| Female | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 54.125 | 46.625 |

| (range) | 32–73 | 29–53 |

| Number of positive nodes | ||

| 1 node | 2 (25%) | 2 (25%) |

| 2 or 3 nodes | 3 (37.5%) | 2 (25%) |

| ≥ 4 nodes | 3 (37.5%) | 4 (50%) |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| Yes | 4 (50%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| No | 4 (50%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Survival terms from diagnosis of stage III (months) | 29.875 | >123.375 |

| (range) | 12–53 | >90–>189 |

The study included 8 Stage III melanoma patients tumor which expressed iNOS and 8 iNOS negative tumors. The median age at melanoma Stage III diagnosis was 54.125 (range 32–73) in iNOS positive patient and 46.625 (range 29–53) in iNOS negative patient. 50% of patients were male and 50% were female in each group. All patients whose tumor were iNOS died of disease within 5 years and all iNOS negative group patients are surviving more than 90 months.

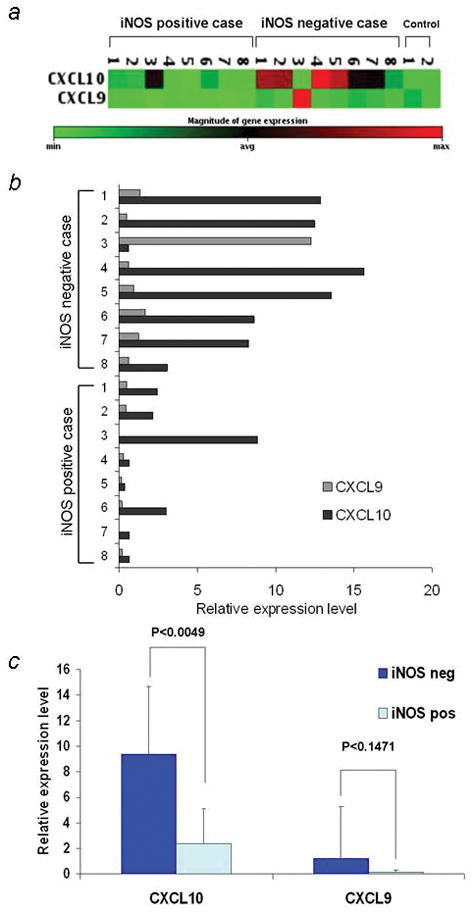

CXCL10 is overexpressed in iNOS-negative melanoma samples

Among the 160 genes analyzed by PCR array 94 genes showed expression in at least one case of melanoma samples (Supporting information Table 1) and only CXCL10 was found to be overexpressed in iNOS negative group at the significant level (p value <0.01). Six of eight iNOS-negative melanoma samples showed high CXCL10 expression with at least 5 times higher expression levels than those in normal lymph node samples (mean increase about 7-fold), whereas only one of eight iNOS-positive melanoma cases showed CXC10 expression (Fig. 1a–c). CXCL9 was also expressed at 8-fold increased levels in iNOS-negative melanomas, whereas expression of CXCL11 was not detected in any case.

Figure 1.

Expression of CXCL10 and CXCL9 in iNOS-positive and iNOS-negative melanoma samples (a) PCR array gene expression clustergram of melanoma lymph node metastasis samples. The magnitude of the gene expression is color coded, as shown beneath the clustergram. (b) Quantitative analysis of the PCR array. The mRNA levels of CXCL10 and CXCL9 in eight iNOS-positive and eight iNOS-negative melanoma samples are estimated. (c) The means and SDs of the CXCL10 and CXCL9 mRNA levels in melanoma samples.

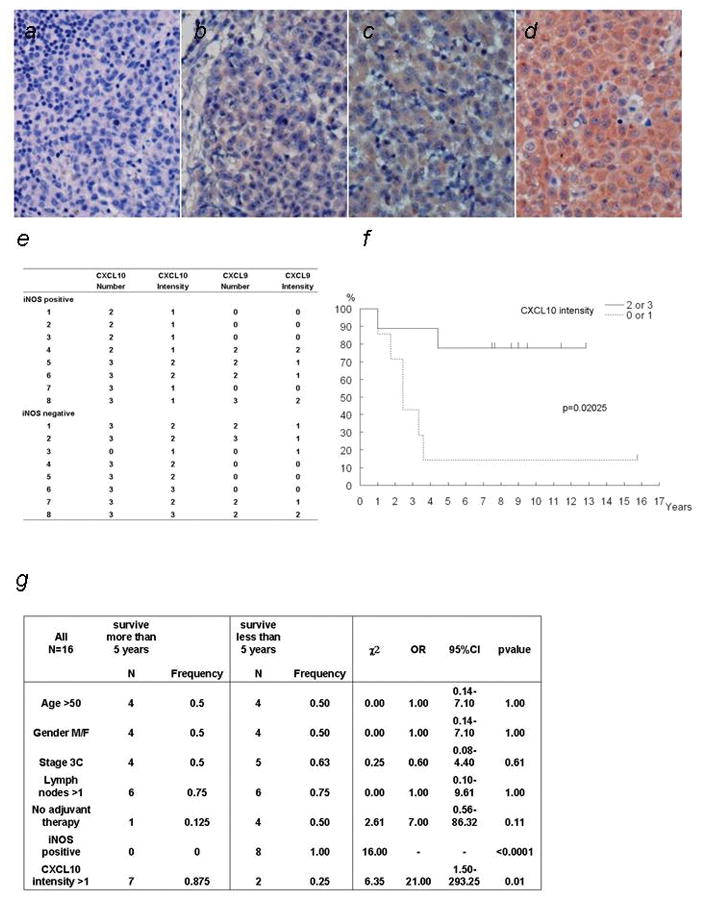

To confirm the expression at the protein level, we measured CXCL10 and CXCL9 expression levels by immunohistochemical analyses of all 16 samples. The number of iNOS-positive melanoma cells and the overall intensity of immunoreactivity of the iNOS-positive cells were scored separately (Fig. 2a–d). CXCL10 was found to be expressed in seven of eight iNOS-negative melanoma samples (intensity level > 2), whereas six of eight iNOS-positive melanoma samples showed lower expression of CXCL10 (intensity level = 1; Fig. 2e, Supporting information Fig. S1). By contrast, there was no significant difference in the CXCL9 staining between the iNOS-positive and -negative groups (Supporting information Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of CXCL10 and correlation of CXCL10 expression level and prognosis of stage III melanoma.

Immunolabeling was scored for number of positive melanoma cells and for the overall intensity of immunoreactivity of the positive cells. (a–d) Representative immunohistochemical staining of stage III melanoma samples (400x). The four panels represent the following intensities of immunostaining (a) 0; (b) 1; (c) 2; (d) 3. (e) Table showes the immunolabeling of the stained tumor samples. Scoring for number of positive tumor cells was defined as follows: “0,” less than 5% positive cells; “1,” 5–25% positive cells; “2,” >25–75% positive cells; “3,” greater than 75% positive cells. 7 out of 8 iNOS negative cases scored 2 or 3 in the CXCL10 intensity. (f) Kaplan-Meier survival curves, illustrating the influence of the CXCL10 expression intensity on disease-specific survival after diagnosis of stage III melanoma. The effect of the combined categories used in the multivariate analysis is displayed. Number of events per number of cases are as follows: CXCL10 score 0 = 0 deaths/1 patient; score 2 = 4 deaths/4 patients; score 3 = 4 deaths/11 patients; CXCL10 intensity score 1 = 6 deaths/7 patients; CXCL10 intensity score 2 = 2 deaths/7 patients; CXCL10 intensity score 3 = 0 deaths/2 patients. (g) Statistical analysis of the patients. Table shows the result of χ2 exact trend test for differences in prognostic factors between long time survivors (more than 5 years) and short time survivors (less than 5 years). Expression of CXCL10 showed the significant difference. OR; odds ratio, 95% CI; 95% confidence interval on OR

Strong CXCL10 expression is correlated with favorable prognosis in patients with stage III melanoma

High CXCL10 expression correlates with clinicopathological variables and favorable prognosis. The expression of CXCL10 in melanoma tumor samples for the 16 melanoma patients and statistically analyzed data are shown in Figure 2 (f) and (g). The 5-year disease-free survival rate was significantly lower in the low-expression group (number = 0 or 1) than in the high-expression group (number = 2 or 3; P < 0.01). On the other hand, no significant differences were observed regarding age, gender, number of lymph nodes involved, or use of adjuvant therapy. In the statistical analysis of the disease-free survival rate, the low CXCL10 expression (intensity ≤ 1) group had a significantly poorer prognosis than the high CXCL10 expression (intensity ≥ 2) group (P = 0.02025; Fig. 2f). In the analysis comparing the number of cells expressing CXCL10, the high expression group (score = 3) showed better prognosis than the low expression group (score ≤ 2), though the results were not statistically significant (P = 0.18242).

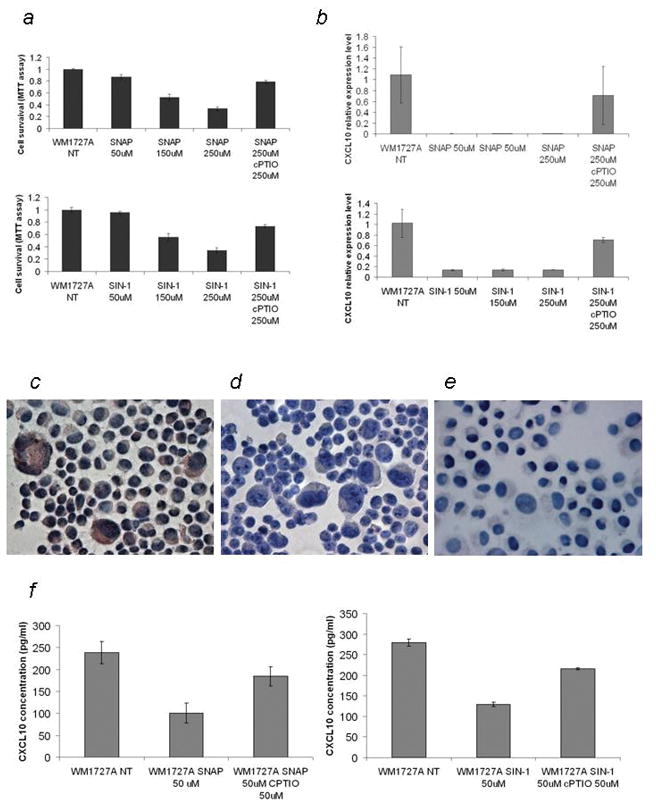

Nitric oxide suppresses the expression of CXCL10

To examine the relationship between the expression of CXCL10 and iNOS, we analyzed their expression levels in melanoma cell lines by immunohistochemical analysis and found that WM1727A cells express CXCL10 but not iNOS (Supporting information Fig. S3). We treated the WM1727A cells with the NO donor SNAP, NO and super oxide donor SIN-1 and analyzed CXCL10 expression. These reagents reduce the cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3a). Treat these cells with 50uM SNAP and SIN-1 downregulated the expression of CXCL10 at the mRNA (Fig. 3b) and protein (Fig. 3c, d and e) levels. Furthermore, the secretion of CXCL10 in culture media was suppressed at the 50% dose when the cells were treated with SNAP and SIN-1, and this was reversed when cPTIO was added (Fig. 3f). These results suggest that NO suppresses the expression of CXCL10 at the mRNA level, decreasing the secretion of the CXCL10 protein.

Figure 3.

Nitric oxide suppresses the expression of CXCL10. (a) MTT assay of WM1727A cells treated with SNAP and SIN-1. WM1727A was treated with 0, 50, 150, and 250 μM of SNAP (upper panel) and SIN-1 (lower panel) with or without 250 uM. The MTT assay was performed 24 hours later. (b) QRT-PCR analysis of CXCL10 mRNA levels in WM1727A cells. WM1727A cells were treated with 0, 50, 150, and 250 μM (upper panel) of SNAP and SIN-1 (lower panel) with or without 250 uM cPTIO, and the expression of CXCL10 was measured by QRT-PCR 24 hours after treatment. Values are shown relative to the levels from untreated cells. (c, d, e) Immunostaining of CXCL10 in the cyto-spin specimen of (c) untreated, (d) SNAP-treated (50 μM, 2 times every 24 hours) and SIN-1 treated (50 μM, 2 times every 24 hours) WM1727A cells. Expression of CXCL10 is visualized as red staining. (f) ELISA of the culture supernatant from WM1727A cells. The WM1727A cells were treated with 0 and 50 μM SNAP (left panel) and SIN-1 (right panel), with or without 50 μM cPTIO every 24 hours, and the concentration of CXCL10 protein was measured by CXCL10 ELISA 48 hours after the initial treatment.

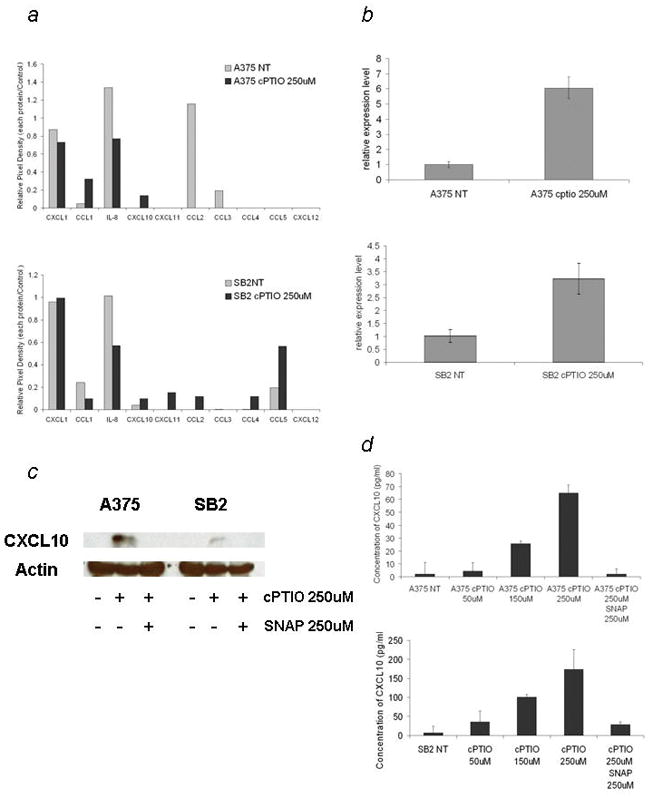

Scavenging NO in melanoma cells affects the cytokine and chemokine expression profile

To analyze the effect of NO scavenging on the expression of chemokines in melanoma cells, we treated the iNOS-positive/CXCL10-negative cell lines A375 and SB2 with the NO scavenger cPTIO. In the analysis of the protein array data, upregulation of CXCL10 and downregulation of IL-8 were observed in both treated cell lines. Marked downregulation of CCL2 in the A375 cells and upregulation of CCL4 and CCL5 in the SB2 cells were also observed (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Scavenging nitric oxide changes the chemokine expression profile including the expression of CXCL10 in iNOS-positive melanoma cells. (a) Chemokine expression profile of A375 cells (upper panel) and SB2 cells (lower panel) treated with and without 250uM c-PTIO.

(b) QRT-PCR analysis of CXCL10 mRNA levels in A375 and SB2 cells treated with 250 uM cPTIO 48 hours after treatment. Values shown are normalized to the levels from untreated cells. (c) Western blotting for CXCL10 in A375 and SB2 cells treated with 250 uM cPTIO or 250 uM cPTIO and 250 uM SNAP for 48 hours. (d) ELISA analysis of culture supernatants. Both cells were treated with 0, 50, 150, and 250 μM of cPTIO, with or without 250 uM SNAP, and the concentration of CXCL10 protein was measured by CXCL10 ELISA 48 hours after treatment.

Upon further analysis, we observed marked CXCL10 upregulation in the mRNA and protein levels in both treated cell lines (Fig. 4b), whereas expression of CXCL9 was not detected under any condition. CXCL10 protein expression was also observed when the cells are treated with cPTIO, and this expression was diminished when SNAP was added (Fig. 4c). cPTIO also induced secretion of CXCL10 into the culture media in a dose-dependent manner, and this secretion was inhibited by SNAP (Fig. 4d). These results suggest that suppression of CXCL10 by NO is a reversible process.

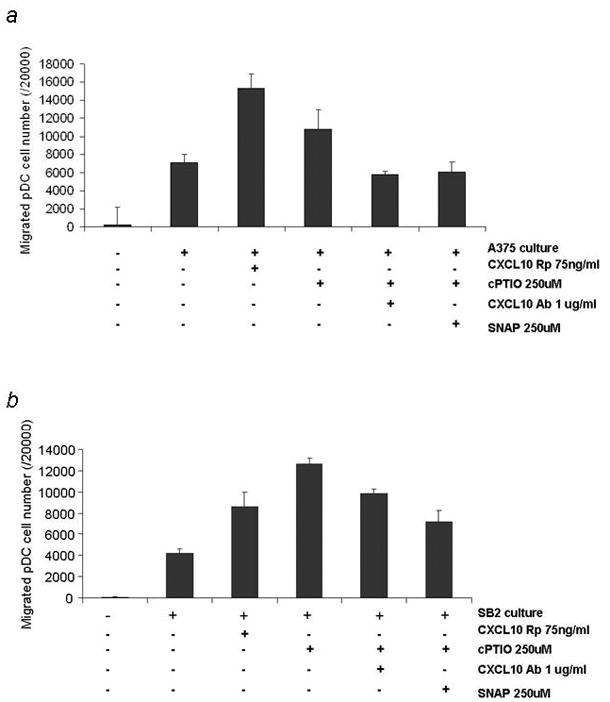

The culture supernatant of c-PTIO-treated melanoma cells promotes the migration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells

Based on the significant difference in the chemokine expression characteristics between the NO-scavenged and untreated melanoma cell lines, we analyzed the immune response of the NO-scavenged melanoma cells by measuring the migration of immune cells. Because CD8+ T cells are reported to migrate toward CXCL10-expressing cells, we focused on pDCs due to their role as the most potent secretors of antiviral type-I interferon-like interferon-alpha, and CXCL10 is reported to be one of the major pDC chemoattractants.14, 15 Migration of pDCs was promoted in both A375 and SB2 cells when the cells were treated with cPTIO and was lost when the cells were treated with SNAP. When the CXCL10-neutralizing antibody was added to the cPTIO-treated media, the increased migration of pDCs was also completely lost in the A375 and partially lost in the SB2 cells. The migration of pDCs was also promoted in these cells when recombinant CXCL10 protein was added to the media (Fig. 5a and b). These results suggest that scavenging NO from melanoma will promote the migration of pDCs, mainly by upregulating expression of CXCL10.

Figure 5.

Culture media from nitric oxide–quenched melanoma cells promotes the migration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The culture media from (a) A375 and (b) SB2 melanoma cells were collected 48 hours after treatment and applied to the migration assay. The migration of pDCs was promoted in these cells when recombinant CXCL10 protein was added to the media. Migration of pDCs was also promoted when the cells were treated with cPTIO and the increased migration of pDCs was completely lost in the A375 and partially lost in the SB2 cells when further treated with SNAP and CXCL10 neutralizing antibody.

Discussion

Tumor microenvironment drives the process of tumor progression. Not only cancer cells but also surrounding cells can secrete various mediators, which can either activate or inhibit angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, metastasis and may contribute to tumor cell survival, positively or negatively.22 Among them, CXCL10 has been described as a promoter of cell-mediated immunity23 and an inhibitor of angiogenesis,24–27 tumor cell growth,28–31 and metastasis32 in several experimental tumors. In melanoma, it is reported as one of the major factors to recruit CD8+T cell in the metastatic lesion,23 inhibits angiogenesis in the xenograft model,27 and reduces proliferation and invasiveness.31

In this study, we showed that expression of CXCL10 is inversely correlated with the expression of iNOS in stage III melanoma lymph node metastasis samples. In the 16 cases of stage III melanoma analyzed, the high CXCL10–expressing group associated with a more favorable prognosis than the low CXCL10–expressing group. Expression of CXCL10 has been characterized previously as a prognostic marker for predicting favorable clinical outcomes in uterine cervical26 and colorectal cancer.33 Because of its heterogenic features, a molecular biomarker for predicting the outcomes of patients with melanoma is desired. We previously reported that expression of iNOS is a predictor of poor outcomes.6 Based on this study, we add that expression of CXCL10, which is negatively correlated with iNOS expression could be a candidate marker of favorable prognosis in patients with stage III melanoma, though the analysis of the larger set of patients should be necessary to rule out the possibility of the selection bias in this study.

Our results further indicate that treating the CXCL10-positive/iNOS-negative melanoma cell lines with a NO donors leads to suppression of CXCL10 expression at mRNA level. The relationship between CXCL10 expression and NO has been described in the study of human rhinovirus–infected airway epithelial cells, where NO was reported to suppress the promoter activity by inhibiting the binding of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and interferon regulating factors.34 It was also hypothesized that s-nitrosilation of those transcription factors by NO modifies their expression levels.34 Taken together, our data suggest that NO suppresses the expression of CXCL10 at the transcriptional level.

Interestingly, our NO-scavenging experiment in iNOS-positive melanoma cells resulted in a significant difference in the expression profiles of chemokines. Along with CXCL10 upregulation, we observed significant downregulation of IL-8 in both the A375 and SB2 cell lines. The downregulation of CCL2 in A375 and upregulation of CCL4 and CCL5 in SB2 cells were also observed. Importantly, these changes in the chemokine profile owing to scavenging NO were observed in the two genetically distinct melanoma cell lines. A375 displays the BRAF V600E activating mutation,37 whereas SB2 has an activating N-Ras mutation.38 Therefore, CXCL10 might be universally regulated by NO regardless of the mutational status of the melanoma cells and the NO regulation of other chemokine expressions will depend on each melanoma cell context. Even though further careful assessment is necessary, the NO-depleted chemokine expression profile seems to be antitumorigenic and angiostatic. IL-8 is a well-known factor promoting angiogenesis and supporting cancer stem cell renewal and invasion.35 CCL2 is reported as a major chemoattractant of tumor-associated macrophages, which promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth.36 We found that these factors are downregulated, while CXCL10 and CCL5, which are the major CD8+ T cell attractants, are upregulated in melanoma cells. Supportively, there are tendency of CCL5 upregulation (2.1 fold increase; p=0.133397) and CCL2 downregulation (1.47 fold decrease; p=0.482002) in iNOS negative tumor group compared to positive group in the PCR array analysis (Supporting information Table 1). These results suggest that tumor cell-derived NO production significantly affects the expression of chemokines and regulates the migration of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment.

NO has been shown to covalently modify proteins, which can lead to regulation of their activity, including caspases,39 retinoblastoma protein,40 c-Src,41 and p53.42 It is also reported to exert complex modulatory effects on the inflammatory pathways through s-nitrosylation,43 and expression of chemokines might also be modified by those events. However, protein s-nitrosylation is a reversible posttranslational modification event,40 and we speculate that reduction of NO will reverse the s-nitrosilation of proteins. These results support the use of NO scavengers or iNOS inhibitors in the treatment of melanoma. We previously demonstrated that depletion of endogenously produced NO can inhibit melanoma proliferation and promote apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner.44 Although these experiments did not completely kill the tumor cells, present study showed that the altered chemokine expression profile, especially CXCL10 expression, of the remaining tumor cells changed the tumor microenvironment from pro- to anti-tumorigenic. Interestingly, a recent report showed that conventional interferon-alpha therapy correlates with the upregulation of CXCL10 in serum from melanoma patients,45 and in vitro analysis showed that interferon-treated melanoma cells secrete CXCL10, which recruits CD8+ T cells. These data highlight the importance of CXCL10 secretion in the treatment of melanoma.

Migration assay results showed that scavenging NO from iNOS-positive tumor cells promotes the migration of pDCs, mainly by upregulating the expression of CXCL10. pDCs have been found in infiltrates of melanoma, and melanoma cells have been proposed to attract pDCs through the secretion of CXCL12.46 A recent report also showed that melanoma attracts circulating pDCs by secretion of CCR6.47 Our study suggests that treating melanoma cells with NO-scavenging agents will further promote the infiltration of pDCs by secreting CXCL10. Recent studies have reported that TLR7 or TLR9 agonist monotherapies48–50 activate tumor-infiltrating pDCs and improve immune responses. Thus, therapies that induce CXCL10 secretion combined with treatments that activate pDCs may further improve the antitumorigenic immune response.

In conclusion, tumor-originated NO inhibits the expression of CXCL10 in the majority of patient melanoma cells and promotes a protumorigenic tumor microenvironment. We have shown that depletion of NO from the tumor cell changes the tumor microenvironment to an antitumorigenic one, including the expression of CXCL10 and migration of pDCs to the tumor. Therefore, iNOS should be strongly considered as a target in the treatment of melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples with CXCL10. P1–P8 show the CXCL10 staining of each iNOS-positive case, and N1–N8 show the CXCL10 staining of each iNOS-negative case.

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples with CXCL9. P1–P8 show the CXCL9 staining of each iNOS-positive case, and N1–N8 show the CXCL9 staining of each iNOS-negative case.

Immunohistochemical staining of WM1727A, A375, and SB2 cell lines. FFPE specimens of (a,b) WM1727A, (c,d) A375, and (e,f) SB2 cells were stained with iNOS (a,c,e) or CXCL10 (b,d,f) antibodies and visualized as red staining. Expression of iNOS was observed in 50% of A375 cells and 40% of SB2 cells, whereas WM1727A did not show any iNOS expression. Expression of CXCL10 was observed in WM1727A cells, but not the A375 or SB2 cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of MDACC Characterized Cell Line Core and the director of this core, Dr. Katherine Stemke Hale for their critical fingerprinting analysis of our melanoma cell lines. We also appreciate the support and effort of the members of our Melanoma Informatics, Tissue Resource and Pathology Core, who provided the de-identified tissues for this research project, as well as maintain accurate patient information available for our studies. We would also like to thank Ms. Sandra A. Kinney for her excellent technical help.

Grant Support

This work was supported by NIH P50 CA093459 (SE, EAG), Institutional Core Grant NIH CA16672 (Characterized Cell Line Core), Adelson Foundation (EAG), and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Core-to Core grant (KT). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. 2010 Available from: seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007.

- 2.Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, Lasithiotakis K, Garbe C, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gogas H, Ioannovich J, Dafni U, Stavropoulou-Giokas C, Frangia K, Tsoutsos D, Panagiotou P, Polyzos A, Papadopoulos O, Stratigos A, Markopoulos C, Bafaloukos D, et al. Prognostic significance of autoimmunity during treatment of melanoma with interferon. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:709–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekmekcioglu S, Ellerhorst J, Smid CM, Prieto VG, Munsell M, Buzaid AC, Grimm EA. Inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in human metastatic melanoma tumors correlate with poor survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4768–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekmekcioglu S, Ellerhorst JA, Prieto VG, Johnson MM, Broemeling LD, Grimm EA. Tumor iNOS predicts poor survival for stage III melanoma patients. IntJ Cancer. 2006;119:861–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:907–16. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wink DA, Vodovotz Y, Laval J, Laval F, Dewhirst MW, Mitchell JB. The multifaceted roles of nitric oxide in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:711–21. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glynn SA, Boersma BJ, Dorsey TH, Yi M, Yfantis HG, Ridnour LA, Martin DN, Switzer CH, Hudson RS, Wink DA, Lee DH, Stephens RM, et al. Increased NOS2 predicts poor survival in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3843–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI42059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luster AD, Ravetch JV. Biochemical characterization of a gamma interferon-inducible cytokine (IP-10) J Exp Med. 1987;166:1084–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taub DD, Lioyd AR, Conlon K, Wang JM, Ortaldo JR, Harada A, Matsushima K, Kelvin DJ, Oppenheim JJ. Recombinant human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a chemoattractant for human monocytes and T lymphocytes and promotes T cell adhesion to endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1809–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jinquan T, Jing C, Jacobi HH, Reimert CM, Millner A, Quan S, Hansen JB, Dissing S, Malling HJ, Skov PS, Poulsen LK. CXCR3 expression and activation of eosinophils: role of IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 and monokine induced by IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2000;165:1548–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanbervliet B, Bendriss-Vermare N, Massacrier C, Homey B, de Bouteiller O, Brière F, rinchieri G, Caux C. The inducible CXCR3 ligands control plasmacytoid dendritic cell responsiveness to the constitutive chemokine stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1)/CXCL12. J Exp Med. 2003;198:823–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohrgruber N, Gröger M, Meraner P, Kriehuber E, Petzelbauer P, Brandt S, Stingl G, Rot A, Maurer D. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment by immobilized CXCR3 ligands. J Immunol. 2004;173:6592–602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Addison CL, Ehlert JE, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strieter RM, Kunkel SL, Arenberg DA, Burdick MD, Polverini PJ. Interferon gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), a member of the C-X-C chemokine family, is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:51–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spurrell JC, Wiehler S, Zaheer RS, Sanders SP, Proud D. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L85–95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishioka Y, Manabe K, Kishi J, Wang W, Inayama M, Azuma M, Sone S. CXCL9 and 11 in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: a role of alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:317–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1999. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijc.21767/?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Abook&rft.genre=book&rft.btitle=SAS%2FSTAT%20User%27s%20Guide%2C%20Version%208&rft.date=1999&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [Google Scholar]

- 21.S-PLUS 2000. Professional Release 3. Seattle, WA: Data Analysis Products Division, MathSoft, Inc; 1988–2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, McKee M, Gajewski TF. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3077–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sgadari C, Angiolillo AL, Cherney BW, Pike SE, Farber JM, Koniaris LG, Vanguri P, Burd PR, Sheikh N, Gupta G, Teruya-Feldstein J, Tosato G. Interferon-inducible protein-10 identified as a mediator of tumor necrosis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13791–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanegane C, Sgadari C, Kanegane H, Teruya-Feldstein J, Yao L, Gupta G, Farber JM, Liao F, Liu L, Tosato G. Contribution of the CXC chemokines IP-10 and Mig to the antitumor effects of IL-12. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:384–92. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.384. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Farber%20JM%22%5BAuthor%5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato E, Fujimoto J, Toyoki H, Sakaguchi H, Alam SM, Jahan I, Tamaya T. Expression of IP-10 related to angiogenesis in uterine cervical cancers. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1735–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman AL, Friedl J, Lans TE, Libutti SK, Lorang D, Miller MS, Turner EM, Hewitt SM, Alexander HR. Retroviral gene transfer of interferon-inducible protein 10 inhibits growth of human melanoma xenografts. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:149–53. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biragyn A, Tani K, Grimm MC, Weeks S, Kwak LW. Genetic fusion of chemokines to a self tumor antigen induces protective, T-cell dependent antitumor immunity. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:253–8. doi: 10.1038/6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narvaiza I, Mazzolini G, Barajas M, Duarte M, Zaratiegui M, Qian C. Intratumoral coinjection of two adenoviruses, one encoding the chemokine IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 and another encoding IL-12, results in marked antitumoral synergy. J Immunol. 2000;164:3112–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maru SV, Holloway KA, Flynn G, Lancashire CL, Loughlin AJ, Male DK, Romelo IA. Chemokine production and chemokine receptor expression by human glioma cells: role of CXCL10 in tumour cell proliferation. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;199:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonicelli F, Lorin J, Kurdykowski S, Gangloff SC, Le Naour R, Sallenave JM, Hornebeck W, Grange F, Bernard P. CXCL10 reduces melanoma proliferation and invasiveness in vitro and in vivo. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:720–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giese NA, Raykov Z, DeMartino L, Vecchi A, Sozzani S, Dinsart C, Cornelis JJ, Rommelaere J. Suppression of metastatic hemangiosarcoma by a parvovirus MVMp vector transducing the IP-10 chemokine into immunocompetent mice. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:432–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Z, Xu Y, Cai S. CXCL10 expression and prognostic significance in stage II and III colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2010;37:3029–36. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9873-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koetzler R, Zaheer RS, Wiehler S, Holden NS, Giembycz MA, Proud D. Nitric oxide inhibits human rhinovirus-induced transcriptional activation of CXCL10 in airway epithelial cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benoy IH, Salgado R, Van Dam P, Geboers K, Van Marck E, Scharpé S, Vermeulen PB, Dirix LY. Increased serum interleukin-8 in patients with early and metastatic breast cancer correlates with early dissemination and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7157–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Yang X, Mukaida N, Yoshihara M, Chayama K. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 transfection induces angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of gastric carcinoma in nude mice via macrophage recruitment. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7629–36. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satyamoorthy K, Li G, Gerrero MR, Brose MS, Volpe P, Weber BL, Elder DE, Helyn M. Constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in melanoma is mediated by both BRAF mutations and autocrine growth factor stimulation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:756–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamin CL, Melnikova VO, Ananthaswamy HN. Models and mechanisms in malignant melanoma. Mol Carcinog. 2007;46:671–8. doi: 10.1002/mc.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rössig L, Fichtlscherer B, Breitschopf K, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM, Mülsch A, Dimmeler S. Nitric oxide inhibits caspase-3 by S-nitrosation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6823–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–7. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacMillan-Crow LA, Greendorfer JS, Vickers SM, Thompson JA. Tyrosine nitration of c-SRC tyrosine kinase in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;377:350–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chazotte-Aubert L, Hainaut P, Ohshima H. Nitric oxide nitrates tyrosine residues of tumor-suppressor p53 protein in MCF-7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:609–13. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall HE, Hess DT, Stamler LS. S-nitrosylation: physiological regulation of NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8841–2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403034101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang CH, Grimm EA. Depletion of endogenous nitric oxide enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis in a p53-dependent manner in melanoma cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:288–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dengel LT, Norrod AG, Gregory BL, Clancy-Thompson E, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Slingluff CL, Mullins DW. Interferons induce CXCR3-cognate chemokine production by human metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2010;33:965–74. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb045d. http://wwwncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Slingluff%20CL%20Jr%22%5B_Author%5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou W, Machelon V, Coulomb-L’Hermin A, Borvak J, Nome F, Isaeva T, Wei S, Krzysiek R, Durand-Gasselin I, Gordon A, Pustilnik T, Curiel DT, et al. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1339–46. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charles J, Di Domizio J, Salameire D, Bendriss-Vermare N, Aspord C, Muhammad R, Lefebvre C, Plumas J, Leccia MT, Chaperot L. Characterization of circulating dendritic cells in melanoma: role of CCR6 in plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment to the tumor. J Invest Dermatol. 2010 Jun;130:1646–56. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pashenkov M, Goess G, Wagner C, Hörmann M, Jandl T, Moser A, Britten CM, Smolle J, Koller S, Mauch C, Tantcheva-Poor I, Grabbe S, et al. Phase II trial of a toll-like receptor 9-activating oligonucleotide in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5716–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molenkamp BG, van Leeuwen PA, Meijer S, Sluijter BJ, Wijnands PG, Baars A, van den Eertwegh AJ, Scheper RJ, de Gruijl TD. Intradermal CpG-B activates both plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells in the sentinel lymph node of melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2961–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dummer R, Hauschild A, Becker JC, Grob JJ, Schadendorf D, Tebbs V, Skalsky J, Kaehler KC, Moosbauer S, Clark R, Meng TC, Urosevic M. An exploratory study of systemic administration of the toll-like receptor-7 agonist 852a in patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:856–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples with CXCL10. P1–P8 show the CXCL10 staining of each iNOS-positive case, and N1–N8 show the CXCL10 staining of each iNOS-negative case.

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples with CXCL9. P1–P8 show the CXCL9 staining of each iNOS-positive case, and N1–N8 show the CXCL9 staining of each iNOS-negative case.

Immunohistochemical staining of WM1727A, A375, and SB2 cell lines. FFPE specimens of (a,b) WM1727A, (c,d) A375, and (e,f) SB2 cells were stained with iNOS (a,c,e) or CXCL10 (b,d,f) antibodies and visualized as red staining. Expression of iNOS was observed in 50% of A375 cells and 40% of SB2 cells, whereas WM1727A did not show any iNOS expression. Expression of CXCL10 was observed in WM1727A cells, but not the A375 or SB2 cells.