Abstract

The norepinephrine nucleus, locus coeruleus (LC), has been implicated in cognitive aspects of the stress response, in part through its regulation by the stress-related neuropeptide, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). LC neurons discharge in tonic and phasic modes that differentially modulate attention and behavior. Here, the effects of exposure to an ethologically relevant stressor, predator odor, on spontaneous (tonic) and auditory-evoked (phasic) LC discharge were characterized in unanesthetized rats. Similar to the effects of CRF, stressor presentation increased tonic LC discharge and decreased phasic auditory-evoked discharge, thereby decreasing the signal-to-noise ratio of the sensory response. This stress-induced shift in LC discharge towards a high tonic mode was prevented by a CRF antagonist. Moreover, CRF antagonism during stress unmasked a large decrease in tonic discharge rate that was opioid mediated because it was prevented by pretreatment with the opiate antagonist, naloxone. Elimination of both CRF and opioid influences with an antagonist combination rendered LC activity unaffected by the stressor. These results demonstrate that both CRF and opioid afferents are engaged during stress to fine-tune LC activity. The predominant CRF influence shifts the operational mode of LC activity towards a high tonic state that is thought to facilitate behavioral flexibility and may be adaptive in coping with the stressor. Simultaneously, stress engages an opposing opioid influence that restrains the CRF influence and may facilitate recovery towards pre-stress levels of activity. Changes in the balance of CRF:opioid regulation of the LC could have consequences for stress vulnerability.

Keywords: corticotropin-releasing hormone, arousal, synchrony, naloxone, auditory-evoked response

1.0 Introduction

1.1. Attributes of the locus coeruleus

The locus coeruleus (LC) is the primary source of the widespread norepinephrine innervation of the forebrain (Jones and Moore, 1977; Swanson and Hartman, 1976). The physiological attributes of LC neurons that were initially characterized implicated this system in arousal and vigilance. For example, LC neurons discharge spontaneously and their frequency is positively correlated to behavioral and electroencephalographic (EEG) indices of arousal (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a). LC neurons are also phasically activated by salient sensory stimuli and this activation precedes behavioral responses to the stimuli, implying a role for the LC in shifting attention (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b; Berridge and Foote, 1991; Bouret and Sara, 2005; Foote et al., 1980). It has recently been proposed that by shifting between tonic and phasic modes of discharge the LC facilitates different behavioral outcomes (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). The phasically-activated LC, characterized by synchronously driven discharge, has been associated with focusing attention and maintaining on-going behavioral tasks. In contrast, a high tonic mode of discharge, which is spontaneous and asynchronous, is associated with scanning the environment and going off-task. The ability of LC neurons to switch between tonic and phasic modes of discharge would facilitate rapid behavioral adjustments in response to environmental challenges.

1.2. The LC and stress

Many of the same stressors that engage the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activate the LC-NE system as indicated by early immediate gene expression and forebrain norepinephrine release (Cullinan et al., 1995; Finlay et al., 1997; Jordan et al., 1994; Kawahara et al., 2000; Kwon et al., 2006; Ma and Morilak, 2005; Pacak et al., 1995; Smagin et al., 1994; Smagin et al., 1997). Because of technical limitations, fewer studies have recorded LC discharge during stress and most of these have examined the effect of physiological stressors on tonic (i.e., spontaneous), but not phasic LC activity (Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1987; Curtis et al., 1993; Morilak et al., 1987a, b). Studies from our laboratory using hypotensive stress or pharmacological stress produced by administration of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) support the idea that stress increases LC discharge and moreover suggest that stress biases the mode of LC discharge away from phasic activity towards a high tonic state (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988; Valentino and Wehby, 1988a). This would suggest that in addition to increasing arousal, LC activation during stress functions to facilitate a disengagement from ongoing behavior and to promote behavioral flexibility in response to challenging environmental conditions, an important cognitive limb of the stress response. Consistent with this, CRF administration into the LC, but not the lateral ventricle, facilitated extradimensional set shifting (Snyder et al., in press).

The present study characterized LC discharge in response to an ethologically relevant stimulus, predator odor. The stimulus chosen was a chemical component of fox feces that has been reported to produce a concentration-dependent activation of the immediate early gene, c-fos in LC neurons as well as in LC afferents (Day et al., 2004). To best evaluate the impact of this stressor on LC discharge characteristics both tonic and phasic discharge were quantified during trials of auditory stimulus presentation. The roles of CRF and endogenous opioids in regulating LC activity in the response to the stressor were assessed in pharmacological antagonist studies.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Animals

The subjects were adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (320–360 g; Charles River, Wilmington, MA) housed three to a cage in a controlled environment (12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 0700 h). Food and water were available ad libitum. Care and use of animals was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and was in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, reduce the number of animals used and to utilize alternatives to in vivo techniques.

2.2. Surgery for microelectrode implantation

Rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane-air mixture, positioned in a stereotaxic frame and surgically prepared for localization of LC with a glass micropipette and subsequent implantation of a microwire electrode array in LC as previously reported (Kreibich et al., 2008). Body temperature was maintained at 37.5° C by a feedback controlled heating unit. A hole (4 mm) was drilled in the skull centered at 3.7 mm caudal and 1.2 mm lateral to lambda for approaching the LC. For experiments in which agents were administered into the lateral ventricle another hole (2 mm diameter) was drilled for implantation of an intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) cannula guide as previously described (Howard et al., 2008). Additionally, five holes were drilled to insert skull screws for fixing the microwire electrode array to the skull with dental cement.

Neuronal recordings with glass micropipettes (2–4 μm diameter tip, 4–7 MOhm) filled with 0.5 M sodium acetate buffer were used to initially localize the LC. These were advanced toward the LC with a micromanipulator. Neuronal signals were amplified, filtered and monitored with an oscilloscope and a loudspeaker. LC neurons were tentatively identified during recording by their spontaneous discharge rates (0.5–5 Hz), entirely positive, notched waveforms (2–3 ms duration), and biphasic excitation–inhibition responses to contralateral hindpaw or tail pinch. Trajectories where LC units were encountered with the glass micropipette for at least 400 microns (dorsal-ventral penetration) were targeted for implantation with the microwire electrode array. The microwire array (NB Labs, Denison, TX) consisted of 8 Teflon insulated stainless steel wires (50 μm diameter) that were gathered in a circular bundle (7–8 mm long) and cut to produce bare wire tips for recording. A ground wire from the array encircled a skull screw and was in contact with brain tissue through another hole drilled next to the anchoring skull screw. The multiwire array was attached to a Microstar head stage and connected to a 16-channel data acquisition system (AlphaLab; Alpha Omega; Nazareth Illit, Israel). Accurate placement was aided by recording neuronal activity through the multiwire array during the implantation procedure. After detecting LC activity, the multiwire array was affixed to the skull and screws with dental cement. For experiments in which agents were administered into the lateral ventricle, an intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) cannula guide was implanted as previously described (Howard et al., 2008). The scalp wound was sutured closed. Post-operative recovery was three days.

2.3. Electrophysiological recordings in unanesthetized rats

For the first 2 days after the postoperative period, rats were habituated to the recording chamber (30 cm long, 22 cm wide, 25 cm high) in which they had free movement. During these sessions, the Microstar cables were connected to the multiwire array for 1 h to assess detection of LC waveforms. In the recording chamber, two depot caps were taped to the inner surface of opposing walls 4 cm above the bedding covered floor. Each depot cap held tissue paper (1.0 cm square) to which 2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethlythiazoline (TMT, 300 μmol in 40 μl), vehicle (water, 40 μl) or butyric acid (600 μmol in 40 μl) were applied using a pipetter. The concentration of TMT chosen was one that has been demonstrated to increase c-fos expression in the LC and in LC afferents, such as the central nucleus of the amygdala (Day et al., 2004). Butyric acid was used as an odorant control and the concentration was based on approximating the same number of volatile molecules as produced by TMT (300 μmol) (Hotsenpiller and Williams, 1997). The depot caps were replaced after each experiment and taped in position before the rat was placed in the chamber. For the first study (Study 1), LC activity was recorded during a 15-min baseline period that included two segments of spontaneous activity (5 min each), one before and one after a 5-min period of auditory stimulation (3 kHz tone, 50 ms duration, 80 db intensity, presented at 0.25 Hz, 50 presentations). After the baseline recording, exposure to vehicle was initiated by pipette application of 40 μl to tissue paper in the depot caps. Immediately after application, another trial of auditory stimulation was initiated followed by a final segment (5 min) of spontaneous activity. Then the rat was returned to the home cage. On the following day (Day Two of Study-1) the same rat was returned to the recording chamber. After recording baseline activity as described above, TMT was applied by pipette to tissue paper in the caps. The trial of auditory stimulation was repeated and the rat was then returned to the home cage. In a separate experiment, LC activity was recorded before and during exposure to butyric acid. These rats were only exposed on a single day (no pre-exposure to water).

For the second Study (Study 2) all rats experienced only one recording session. Each rat had a cannula guide implanted for injection of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, 3 μl, i.c.v.), the CRF antagonist, DPheCRF12–41 (3 μg in 3 μl ACSF, i.c.v.), naloxone (10 μg in 3 μl ACSF, i.c.v.) or a combination of DPheCRF12–41 (3 μg) and naloxone (10 μg in 3 μl ACSF, i.c.v.). The dose of DPheCRF12–41 chosen is that which prevents LC activation by CRF and hypotensive stress (Curtis et al., 1994). In these experiments the baseline recording period (15 min) was the same as that described for Study 1 but was followed by injection of an antagonist or ACSF. Exposure to TMT by pipetter application to the depot caps began 8–10 min after i.c.v. injections and a trial of auditory stimulation was initiated immediately after TMT application. Additional experiments assessed the effects of DPheCRF12–41 or naloxone alone on LC spontaneous and auditory-evoked discharge in the absence of TMT exposure.

2.4. Data Analysis

Putative LC multiunit activity was recorded as continuous analog waveforms using the AlphaLab interfaced to a host computer. Extracellular unit waveforms were amplified at a gain up to 25,000 with a bandwidth of 800 Hz to 1.4 kHz. Multiunit activity on all eight wires (channels) was monitored in real time simultaneously during experiments and spike sorting of multiunit activity was done off-line. The WaveMark template-matching algorithm in the Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, CED) was used to discriminate putative LC single-unit waveforms. A set of waveforms identified by the Wave Mark template is verified as events from a single unit by analyses of principal component clusters and associated autocorrelograms (Fig. 1). For principal component clusters, Spike2 generates a cluster of dots representing waveform events from a putative single unit in three-dimensional space. An ellipsoid representing 2 standard deviations (in three-dimensional space) from the cluster centrality is generated with the cluster of waveform events (Fig. 1b). The lack of overlap of any two ellipsoids was considered verification that the clusters were events from separate single units. An autocorrelogram of a set of waveform events in which no spikes occurred during an absolute refractory period of 2.0 ms was considered verification that those events were from a single unit (Fig. 1c). For each channel with LC activity, two to three single units were usually discriminated. LC activity was typically isolated on 2–4 channels in an individual rat.

Figure 1.

Discrimination of single units from LC recordings. a) Accumulated waveforms of three units discriminated from a multiunit analog record by the wavemark template matching algorithm. b) Cluster plot of the principal component analysis for the three representative waveform sets in a. Each waveform in the template is represented by a color-coded event dot in the principal component space, thereby generating its respective principal component cluster. The ellipsoids around the clusters are three-dimensional representations of 2 SD from cluster centrality. The lack of overlap of the ellipsoids suggests that the clusters represent single units. c) The histograms are inter-spike interval autocorrelograms that are color-matched with their associated set of waveforms (a) and component clusters (b). The abscissae indicate time in milliseconds, whereas the ordinates indicate number of intervals per bin. For LC neurons, the onset of the relative refractory period is 3 ms, suggesting that at least 2 ms to the left of 0 and 2 ms to the right of 0 should be devoid of spike interval histograms in an autocorrelogram of a single LC unit.

Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were generated offline from activity recorded during the period of repeated auditory stimulation. Discriminated LC unit discharge was pooled in 8 ms bins beginning 0.5 s before to 1.5 s after the auditory stimulation. Tonic and evoked LC activity were quantified from PSTHs as described previously (Valentino and Foote, 1987). Briefly, the histogram was divided into different time components and the discharge rate for each component was determined. The first 500 ms represented the unstimulated or tonic activity. The evoked component was defined as that period after the stimulus when LC discharge rate exceeds the mean tonic discharge rate plus 2 SD. Rates during the different components were compared before and after introduction of TMT or vehicle by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

To get an indication of neuronal synchrony in different experimental conditions, cross-correlograms were generated using Neuroexplorer from the discriminated spike trains of pairs of LC units recorded from the same channel. The peak Z score was determined for each histogram. Peak Z score is a numerical assessment of synchronous activity between a pair of neurons by the relation of the maximum value of the central peak (at time 0 sec) of the histogram to the mean and standard deviation of the histogram background. The time axis range for the histograms was 800 ms in 50 ms bin size extending 400 ms on either side of the zero time point as this interval included the trough between the central peak and the first satellite peak proximate to the central peak for all analyzed cross-correlograms. Peak Z scores of cross-correlograms from baseline recordings were compared to those determined during TMT exposure by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

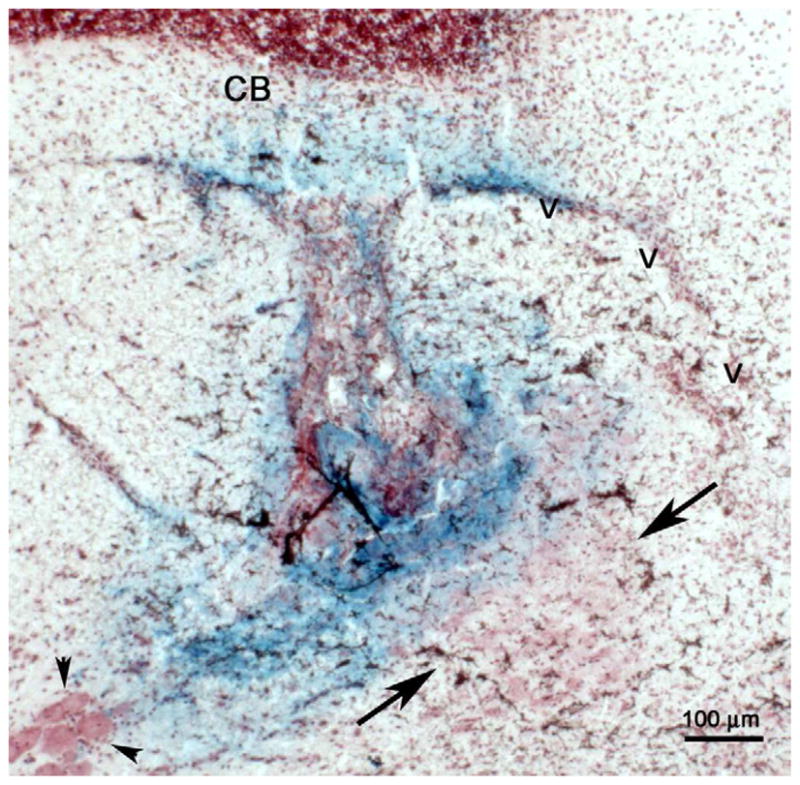

2.5. Histology

At the end of the experiment, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and current was passed through the electrode (10 mA, 15 s). Rats were perfused through the heart with 60 ml of 0.24M potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline to form a Prussian blue reaction product for identification of the recording site. Frozen sections were cut on a cryostat and stained with neutral red for visualization of the Prussian blue labeled recording site (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histological verification of a recording site in the LC. Photomicrograph showing a coronal section stained with neutral red at the level of the LC. The arrows point to the LC. The darkened region within the LC is the Prussian blue stain produced by deposited metal ions reacting with potassium ferrocyanide. The arrowheads indicate the location of soma of the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus lateral to the LC. V= Ventricle, CB=cerebellum. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

2.6. Drugs

TMT (2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethlythiazoline) was obtained from Phero Tech Inc. (Delta, BC, Canada). DPheCRF12–41 was a generous gift from Dr. Jean Rivier of the Clayton Foundation Laboratory for Peptide Biology (Salk Institute, San Diego, CA). The opioid antagonist, naloxone and butyric acid were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

3.0. Results

3.1. Predator odor exposure alters LC tonic and auditory-evoked discharge

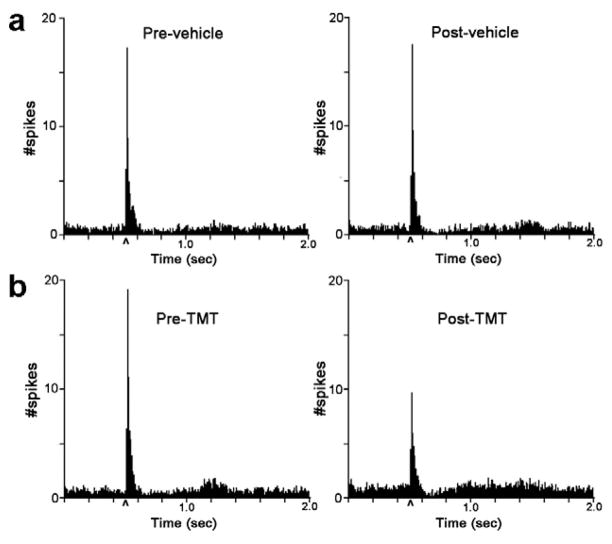

As previously reported (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b), LC neurons of unanesthetized rats were phasically activated by the repeated presentation of auditory stimuli (Fig. 3a). This response was reproducible and stable with repeated trials of auditory stimulation (Fig. 3a). Thus, the magnitude of tonic and evoked LC discharge and the signal-to-noise ratio of the response remained unchanged during a second trial that was presented after pipetting vehicle into the caps (Fig. 3a, Table 1-H2O alone). Figure 3a shows the average PSTHs generated from 22 units (4 rats) before and after exposure to vehicle. Figure 3b shows the average PSTHs (n=25 neurons) from the same four rats recorded before and after TMT exposure 24 h later. Although it could not be assured that recordings were from identical LC neurons from day 1 to day 2, the magnitudes of LC tonic and auditory-evoked activity recorded in the same subjects on consecutive days were comparable (Fig. 3a,b, Table 1; pre-H2O vs. pre-TMT). In contrast to the introduction of vehicle into the chamber, the introduction of TMT increased tonic LC discharge (140±3% of pre-TMT rate). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA for tonic discharge rate indicated no effect of treatment (F(1,45)=1.4, p=0.25), an effect of time (F(1,93)=20.9, p<0.001) and a treatment*time interaction (F(1,93)=15.0, p<0.001). TMT exposure also decreased auditory-evoked activity (61±3% of pre-TMT rate) (Fig. 3b, Table 1). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA for evoked discharge rate revealed a trend for a treatment effect (F(1,45)=3.7, p=0.06), an effect of time (F(1,93)=42.4, p<0.001) and a treatment*time interaction (F(1,93)=35.1, p<0.001). As a result, the signal-to-noise ratio of the LC sensory response was reduced by TMT exposure (Table 1). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA for the signal-to-noise ratio indicated an effect of treatment (F(1,45)=10.3, p=0.002), time (F(1,93)=5.1, p<0.05) and a treatment*time interaction (F(1,93)=7.8, p<0.01). In contrast to TMT, there was no effect of butyric acid on either tonic or evoked LC discharge or in the signal-to-noise ratio (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Effect of TMT exposure on LC tonic and auditory-evoked activity. a) Shown are the average PSTHs (n=22 cells from 4 rats) generated before (Pre-vehicle) and immediately after (Post-vehicle) pipetting water into the caps. b) The average PSTHs (n=25 cells from same 4 rats) generated before (Pre-) and immediately after (Post-) introduction of TMT.

Table 1.

Absolute mean rates and signal-to-noise values for each experimental condition

| Tonic (Hz) | Evoked (Hz) | Signal:Noise | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Study 1a | ||||||

| H2O alone (22; 4 rats) | 1.7±0.2 | 1.8±0.2 | 22.7±1.4 | 22.3±1.3 | 21.0±3.8 | 21.8±4.1 |

| TMT alone (25; 4 rats) | 1.8±0.2 | 2.5±0.3*** | 23.6±1.9 | 14.0±1.0*** | 14.7±0.9 | 6.3±0.4*** |

| Butryic acid (16,3 rats) | 2.2±0.2 | 2.3±0.2 | 20.8±1.4 | 19.9±1.6 | 10.8±1.3 | 9.8±0.9 |

| Study 2b | ||||||

| ACSF/TMT (28; 3 rats) | 1.6±0.1 | 2.1±0.2*** | 22.2±1.6 | 10.3±0.9*** | 15.6±1.2 | 5.4±0.5# |

| DPhe/TMT (26; 4 rats) | 1.6±0.1 | 0.4±0.1*** | 20.8±2.5 | 20.2±3.1 | 14.7±2.3 | 72.6±13.1*** |

| NX/TMT (12; 2 rats) | 1.3±0.1 | 2.1±0.2*** | 19.7±1.6 | 9.2±0.7*** | 15.8±1.2 | 4.5±0.4 |

| DPhe/NX/ TMT (32; 3 rats) | 1.6±0.1 | 1.5±0.1 | 19.7±1.0 | 20±1.2 | 13.3±0.8 | 14.3±1.1 |

***p<0.001 Student-Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test comparing Pre vs. Post within treatment group

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA for tonic: effect of treatment F(3,94)=10.5, p<0.001; time F(1,195)=0.07, ns; treatment*time interaction F(3,195)=122, p<0.001. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA for evoked: effect of treatment F(3,94)=2.2, ns; time F(1,195)=119, p<0.001; treatment*time interaction F(3,195)=46.3, p<0.001. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA for signal-to-noise: effect of treatment F(3,94)=16.8, p<0.001; time F(1,195)=7.6, p<0.01; treatment*time interaction F(3,195)=26.9, p<0.001.

p<0.001 Student-Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test comparing Pre vs. Post within treatment;

p=0.09 Student-Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test comparing Pre vs. Post within treatment

Parentheses indicate number of cells;rats.

3.2. Role of CRF in LC responses to TMT exposure

The effects of TMT exposure on LC tonic and sensory-evoked discharge are similar to those produced by CRF administration or by hypotensive stress, which releases CRF in the LC (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988; Valentino et al., 1991). To determine whether CRF was involved in the effects of TMT on LC activity, rats were administered ACSF or the CRF antagonist, DPheCRF12–41, prior to TMT exposure. Figure 4a shows the average PSTHs before and after TMT exposure of ACSF-treated rats. The ability of predator odor to increase tonic LC discharge rate and decrease auditory-evoked discharge seen in rats not pretreated with ACSF was reproduced in ACSF-pretreated rats (Fig. 4a, Table 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of antagonizing CRF and/or endogenous opioids on LC activity during TMT exposure. a) Mean PSTHs (n=28 cells, 3 rats) generated before and after ACSF (3 μl, i.c.v.) pretreatment followed by TMT exposure. Note the increase in tonic discharge rate and decrease in evoked discharge rate similar to that see in Figure 3b. b) Mean PSTHs (26 cells; 4 rats) generated before and after pretreatment with DPheCRF12–41 followed by TMT exposure. Note that with CRF antagonist pretreatment evoked discharge is not decreased by TMT and a large decrease in tonic activity is apparent. c) Mean PSTHs (32 cells; 3 rats) generated before and after pretreatment with a combination of DPheCRF12–41 and naloxone followed by TMT exposure. Note that TMT appears to have no effect on LC activity in rats pretreated with the antagonist combination. The abscissae indicate time in seconds before and after the auditory stimulus, which starts at 0.5 s (arrowhead), and the ordinates indicate the averaged number of cumulative discharges across all units in the group in each 8 ms bin.

Exposure of ACSF-pretreated rats to vehicle rather than TMT did not alter LC tonic or auditory evoked activity or the signal-to-noise ratio. Thus, tonic rates before and after vehicle exposure were 1.4±0.2 Hz and 1.4±0.1 Hz, respectively (n=12 cell/3 rats). Evoked rates for the same cells were 21.7±1.7 Hz and 22.5±1.6 Hz, respectively and the signal-to-noise ratio was 16.7±1.5 and 16.8±1.5, respectively.

Pretreatment with the CRF antagonist, DPheCRF12–41 (3 μg, i.c.v.) prevented the decrease in auditory-evoked activity produced by TMT exposure and unmasked a large inhibition of tonic discharge, resulting in an increased signal-to-noise ratio of the sensory response (Fig. 4b, Table 1). DPheCRF12–41 had no effect on its own in the absence of stress. Thus, tonic rates were 1.9±0.2 and 1.8±0.2 before and after DPheCRF12–41, respectively (14 cells; 2 rats). Evoked rates for the same cells were 20.5±0.9 and 20.7±0.8 before and after DPheCRF12–41, respectively and the signal-to-noise ratios were 12.8±1.6 and 15.4±3.0 before and after DPheCRF12–41, respectively.

The increased signal-to-noise ratio suggested increased synchrony in LC discharge. This was assessed by analysis of cross-correlograms of cells recorded on the same wires. Figure 5 shows representative cross-correlograms generated from pairs of single units that were recorded from the same microwire before and after TMT for a rat administered ACSF and a rat administered DPheCRF12–41 (i.c.v.) prior to TMT exposure. The mean peak Z scores of the cross correlograms were 4.1±0.6 and 3.8±0.5 before and after TMT exposure for ACSF pretreated rats (n=27 cell pairs) and 3.7± 0.4 and 8.6±1.3 before and after TMT exposure for DPheCRF12–41 treated rats (n=19 cell pairs). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated an effect of treatment (F(1,45)=6.2, p=0.02), time (1,45)=22.3, p<0.0001) and a time*treatment interaction (F(1,45)=27, p<0.0001) indicating that LC neurons fired more synchronously after TMT exposure when CRF receptors were blocked.

Figure 5.

Representative cross correlograms from pairs of LC neurons recorded on the same wire. a) Correlograms for the same cell pair before and after exposure to TMT. The peak Z scores were 2.97 and 4.89 before and after TMT, respectively. b) Correlograms for the same cell pair before and after TMT in a rat that was pretreated with DPheCRF12–41 prior to TMT exposure. The peak Z scores were 3.12 and 9.52 before and after TMT, respectively. Note the large peak indicative of greater synchrony between cells after TMT exposure in the rat pretreated with DPheCRF12–41. The abscissae indicate interspike intervals in 50 ms bins and the ordinates indicate the number of counts/bin.

3.3. Opposing opioid influence on LC activity during TMT exposure

We and others have provided evidence that endogenous opioids are released during stress or stress termination to inhibit LC activity (Abercrombie and Jacobs, 1988; Curtis et al., 2001). In the present study, the hypothesis that endogenous opioids mediated the LC inhibition revealed by antagonizing CRF in stressed rats was tested. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA of LC discharge rates before and after TMT indicated similar effects in rats pretreated with the opioid antagonist, naloxone compared to rats pretreated with ACSF (Table 1). However, a comparison of the percentage increase in tonic LC discharge rate elicited by TMT exposure indicated a greater effect of naloxone (66±5%) compared to ACSF (32±3%) pretreatment (p<0.0001, Student’s t-test). Eliminating the influence of both CRF and endogenous opioids by pretreating rats with a combination of DPheCRF12–41 and naloxone completely prevented the ability of TMT exposure to affect LC tonic and sensory-evoked discharge characteristics (Fig. 4, Table 1). The decrease in tonic discharge rate seen with DPheCRF12–41 alone was absent in rats treated with the DPheCRF12–41/naloxone combination. The mean PSTH appeared identical in rats pretreated with both antagonists before and after TMT exposure (Fig. 4c). The effects of TMT in these subjects were indistinguishable from those that were pretreated with ACSF and exposed to vials containing water (Table 1).

4.0. Discussion

This is the first study to characterize the effects of stress on both tonic and sensory-evoked LC discharge in unanesthetized rats. Exposure to an ethologically relevant stressor altered LC neuronal activity of unanesthetized rats such that tonic discharge rate was increased and phasic discharge evoked by an auditory stimulus was decreased. The bias away from a phasic mode and towards a high tonic mode of discharge would favor a shift in attention from focused to scanning and promote behavioral flexibility, an effect that would be adaptive in responding to a threat (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). This stress-induced shift in the mode of LC discharge was CRF-mediated, consistent with CRF mediation of LC activity during hypotensive stress (Curtis et al., 2001; Valentino et al., 1991). In addition to CRF, predator odor engaged a robust inhibitory endogenous opioid influence on tonic LC discharge that was revealed when the CRF influence was eliminated or when an opiate antagonist was administered. Similar to the pharmacological effects of morphine (Zhu and Zhou, 2001), this opioid influence promoted synchrony between LC neurons and a shift towards a phasic mode of discharge, opposite to the effect of CRF. The opioid influence may serve to curb the CRF effect on LC activity during the stress response and protect against an inappropriately excessive or prolonged responses.

4.1. Stress shifts the operating mode of LC neurons

The putative functions of the LC-norepinephrine system are based in part on the specific electrophysiological characteristics of LC neurons. Two patterns of LC discharge (tonic vs. phasic) favor different modes of signal processing and behavior (see for reviews (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). In the tonic mode, LC neurons are thought to be uncoupled and discharge spontaneously at frequencies that correlate to the state of arousal (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a). LC neurons are also phasically driven by salient sensory stimuli (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b; Ennis et al., 1992). In this phasic mode, LC discharge is synchronous as a result of electrotonic coupling (Christie et al., 1989; Usher et al., 1999). Tonic and phasic modes of LC discharge are interrelated such that phasic discharge is optimal within a narrow range of moderate tonic discharge rate. Thus, phasic activity is diminished either when tonic discharge rate is low (e.g., slow wave sleep) or when tonic activity exceeds the optimum moderate level (Aston-Jones et al., 2000; Usher et al., 1999). This inverted U-shaped relationship between tonic and phasic LC discharge has suggested that the LC maintains an appropriate level of arousal for optimally processing sensory information (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). At moderate levels of tonic activity when phasic discharge is optimal, attention is sustained on relevant stimuli. However, during high levels of tonic activity associated with elevated arousal, diminished phasic discharge is related to labile attention. Behaviorally based perspectives of the functions of LC discharge modes emerged from evidence that phasic discharge is linked to behavioral outcome in response to task-related stimuli, rather than the sensory component of the stimuli (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). This perspective posits that the phasic mode of LC discharge facilitates behavioral responses to ongoing tasks. In contrast, a shift towards higher tonic and diminished phasic discharge would promote going off-task and searching for alternative tasks that may be optimal in a dynamic environment or when the present behavior is not adaptive.

In the present study, predator odor stress shifted the operational mode of LC neurons to a high tonic state in which phasic responses to brief auditory stimuli were reduced. The neuronal effect was selective to the predator odor in this study because disrupting the ongoing environment by introducing vehicle into the caps, exposing to another odorant (butyric acid) or manipulation of the rat for i.c.v. administration of ACSF did not reproduce the neuronal effects. Indeed the pattern of LC discharge during control conditions remained remarkably stable. The neuronal effects of predator odor stress were similar to those reported for the physiological stressor, hypotensive challenge, in anesthetized rats presented with repeated sciatic nerve stimulation as the sensory stimulus (Valentino and Wehby, 1988a). That these effects generalize across stressors and sensory stimuli of different modalities, implies that the shift towards a high tonic mode of LC activity that is associated with heightened arousal, labile attention and behavioral flexibility is a fundamental and adaptive effect of stress on the LC-norepinephrine system.

4.2. Role of CRF in stress effects on LC neurons

Anatomical and electrophysiological evidence supports a role for CRF as a neurotransmitter acting within the LC that alters neuronal activity during stress (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). CRF administered i.c.v. or directly into the LC increases tonic discharge rate (Curtis et al., 1997). Similar effects occur in LC slice preparations in vitro (Jedema and Grace, 2004). CRF also decreases LC phasic discharge and the signal-to-noise ratio of the sensory response, similar to the effects produced by hypotension and predator odor stress (Valentino and Foote, 1987; Valentino and Foote, 1988). Notably, intra-LC CRF increases behavioral flexibility in an attentional set shifting task, an effect that would be predicted based on its electrophysiological effects on LC neurons (Snyder et al., in press). Endogenous CRF released within the LC mediates LC activation by hypotensive stress because intra-LC injection of a CRF antagonist prevented the effect (Curtis et al., 1994; Valentino et al., 1991). Additionally, manipulations that desensitized LC neurons to CRF resulted in cross-desensitization to hypotensive stress (Curtis et al., 1995). The multiwire bundle used for multiunit recordings from unanesthetized rats does not allow for intra-LC injections of antagonists. Therefore, although the experiments using intracerebroventricular antagonist administration indicate the requirement for central CRF in LC activation by predator odor, it is not possible to state with certainty that this is the direct result of CRF afferents synapsing onto LC neurons. Nonetheless, the finding that these results using predator odor stress and intracerebroventricular administration of the CRF antagonist mimicked those using hypotensive stress and intra-LC antagonist administration, taken with the body of evidence for direct CRF neuromodulation of the LC (see above), strongly suggests that exposure to predator odor stress engages CRF inputs to the LC to affect the mode of activity. The ability of CRF to set the mode of LC discharge towards one that favors increased arousal and behavioral flexibility complements its neurohormone role to engage the endocrine limb of the stress response.

4.3. Role of endogenous opioids in stress effects on LC neurons

Endogenous opioids densely innervate the LC and LC neurons express μ-opiate receptors (Mansour et al., 1988; Pert et al., 1975; Tempel and Zukin, 1987; Van Bockstaele et al., 1995; Van Bockstaele et al., 2000). Inhibitory effects of activating μ-opiate receptors on LC neurons have been well described (Aghajanian and Wang, 1987; Williams and North, 1984). Notably, because tonic LC discharge is more sensitive to opioid inhibition than phasic discharge, the signal-to-noise of LC sensory responses is increased by opiate receptor activation, an effect distinctly opposite that produced by CRF (Valentino and Wehby, 1988b). Additionally, morphine promotes synchrony between LC neurons, an effect that would contribute to biasing the discharge mode towards a phasic state (Zhu and Zhou, 2001). Abercrombie and Jacobs (1988) demonstrated that systemic naloxone increased LC discharge rates in cats exposed to restraint stress but not unstressed cats, suggesting that stress releases endogenous opioids to inhibit LC tonic activity. Subsequently we demonstrated that intra-LC naloxone microinfusion prevents the inhibition of LC discharge rate that occurs with the termination of hypotensive stress (Curtis et al., 2001). This study suggested that endogenous opioids, were released in the LC with stress termination to reinstate tonic LC activity to baseline levels, thus restoring arousal, attention and behavior to pre-stress states. The present study provides further evidence that endogenous opioids are released during stress to affect the LC system in a manner that opposes the effect of CRF. Unlike hypotensive stress where opioid effects were most apparent immediately upon stressor termination, predator odor simultaneously engaged both CRF and opioid systems to affect the LC. This was seen as a robust naloxone-sensitive inhibition when the CRF influence was removed by administration of DPheCRF12–41. The results support the concept that the opioid influence serves to restrain the effects of CRF. This role of opioids is clinically relevant as its loss in opiate tolerant individuals would result in an inappropriately exaggerated stress response of the LC system.

Finally, it is noteworthy that antagonism of both CRF and opioid influences rendered the LC completely unresponsive to the stressor. This suggests that the effects of stress on the LC-norepinephrine system are primarily (if not solely) mediated by CRF and endogenous opioids.

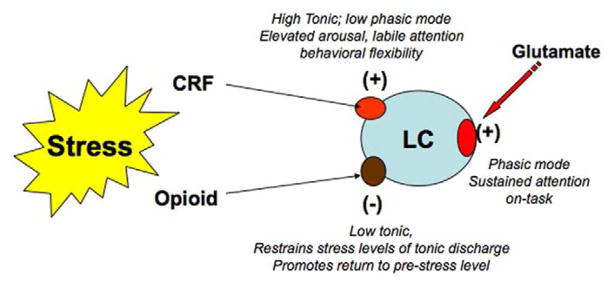

4.4. Conclusion

The schematic in Figure 6 depicts a putative model of how the operational mode of LC neurons may be dictated by specific afferents. In an unstressed state, sensory stimuli engage excitatory amino acid inputs that set the phasic mode of LC discharge that is associated with selective attention and remaining on-task. The robust and rapid response of LC neurons to glutamate resembles the phasic burst produced by sensory stimuli and LC microinfusion of non-NMDA antagonists prevents LC activation by certain sensory stimuli (Aston-Jones and Ennis, 1988; Ennis et al., 1992; Szabo and Blier, 2001). CRF has a qualitatively different effect on LC neurons, producing a lower magnitude, longer duration activation (Curtis et al., 1997). Its release in the LC by stressors shifts the operational mode to a high tonic, low phasic state that is associated with labile attention and going off-task. Although at sufficiently high doses, opiates can completely inhibit tonic and phasic LC activity (Valentino and Wehby, 1988b), the release of endogenous opioids during stress selectively inhibits tonic LC activity and this functions to restrain the effects of CRF on the LC system and to return activity to pre-stress levels when the stressor is terminated. The interaction of these inputs fine-tunes the activity of the LC-norepinephrine system to facilitate adaptive behaviors in a dynamic environment.

Figure 6.

Schematic depicting how LC discharge mode is influenced by different afferent inputs. In awake but unstressed conditions, salient sensory stimuli engage glutamatergic afferents that phasically drive LC neurons. Stress engages parallel CRF and endogenous opioid inputs to the LC. The CRF input shifts LC discharge to a high tonic-low phasic mode that has been suggested to facilitate behavioral flexibility. At the same time the opioid input provides a brake on LC discharge, which if eliminated, would result in an even greater tonic activation by the stress.

Highlights.

Predator stress biases LC activity towards a high tonic mode

CRF mediates the bias towards a high tonic LC activity induced by predator stress

Endogenous opioids are engaged during predator stress to counterbalance CRF actions

Acknowledgments

Supported by PHS grants DA09082, MH40008. The authors acknowledge the technical expertise of Mr. Kile McFadden and statistical consultation by Nayla Chaijale. Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Joe Marwah (Jwaharlal Marwaha) for his mentorship of Dr. Andre Curtis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6.0. References

- Abercrombie ED, Jacobs BL. Single unit response of noradrenergic neurons in locus coeruleus of freely moving cats. I Acutely presented stressful and nonstressful stimuli. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2837–2843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02837.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abercrombie ED, Jacobs BL. Systemic naloxone administration potentiates locus coeruleus noradrenergic neuronal activity under stressful but not non-stressful conditions. Brain Res. 1988;441:362–366. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajanian GK, Wang YY. Common alpha2 and opiate effector mechanisms in the locus coeruleus: intracellular studies in brain slices. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26:793–399. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(87)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981a;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. J Neurosci. 1981b;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Ennis M. Sensory-evoked activation of locus coeruleus may be mediated by a glutamate pathway from the rostral ventrolateral medulla. In: Cavalheiro A, Lehmann J, Turski L, editors. Frontiers in Excitatory Amino Acid Research. A.R. Liss, Inc; New York: 1988. pp. 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Cohen J. Locus coeruleus and regulation of behavioral flexibility and attention. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:165–182. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Foote SL. Effects of locus coeruleus activation on electroencephalographic activity in the neocortex and hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3135–3145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03135.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouret S, Sara SJ. Network reset: a simplified overarching theory of locus coeruleus noradrenaline function. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Williams JT, North RA. Electrical coupling synchronizes subthreshold activity in locus coeruleus neurons in vitro from neonatal rats. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3584–3589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-10-03584.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Helmreich DL, Watson J, SJ . A neuroanatomy of stress. In: Friedman MJ, Charney DS, Deutch AY, editors. Neurobiological and Clinical Consequences of Stress: From Normal Adaptation to PTSD. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1995. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Bello NT, Valentino RJ. Endogenous opioids in the locus coeruleus function to limit the noradrenergic response to stress. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Drolet G, Valentino RJ. Hemodynamic stress activates locus coeruleus neurons of unanesthetized rats. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:737–744. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90150-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Florin-Lechner SM, Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Activation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system by intracoerulear microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on discharge rate, cortical norepinephrine levels and cortical electroencephalographic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Grigoradis D, Page ME, Rivier J, Valentino RJ. Pharmacological comparison of two corticotropin-releasing factor antagonists: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Pavcovich LA, Valentino RJ. Previous stress alters corticotropin-releasing factor neurotransmission in the locus coeruleus. Neuroscience. 1995;65:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00496-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HE, Masini CV, Campeau S. The pattern of brain c-fos mRNA induced by a component of fox odor, 2,5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline (TMT), in rats, suggests both systemic and processive stress characteristics. Brain Res. 2004;1025:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis M, Aston-Jones G, Shiekhattar R. Activation of locus coeruleus neurons by nucleus paragigantocellularis or noxious sensory stimulation is mediated by intracoerulear excitatory amino acid neurotransmission. Brain Res. 1992;598:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay JM, Jedema HP, Ravinovic AD, Mana MJ, Zigmond MJ, Sved AF. Impact of corticotropin-releasing hormone on extracellular norepinephrine in prefrontal cortex after cold stress. J Neurochem. 1997;69:144–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3033–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotsenpiller G, Williams J. A synthetic predator odor (TMT) enhances conditioned analgesia and fear when paired with a benzodiazepine receptor inverse agonist. Psychobiology. 1997;25:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Howard O, Carr GV, Hill TE, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Differential blockade of CRF-evoked behaviors by depletion of norepinephrine and serotonin in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:569–582. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1179-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Grace AA. Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly activates noradrenergic neurons of the locus ceruleus recorded in vitro. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9703–9713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2830-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE, Moore RY. Ascending projections of the locus coeruleus in the rat. II Autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1977;127:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S, Kramer GL, Zukas PK, Petty F. Previous stress increases in vivo biogenic amine response to swim stress. Neurochem Res. 1994;19:1521–1525. doi: 10.1007/BF00969000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara H, Kawahara Y, Westerink BH. The role of afferents to the locus coeruleus in the handling stress-induced increase in the release of norepinephrine in the medial prefrontal cortex: a dual-probe microdialysis study in the rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;387:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich A, Reyes BA, Curtis AL, Ecke L, Chavkin C, Van Bockstaele EJ, Valentino RJ. Presynaptic inhibition of diverse afferents to the locus ceruleus by kappa-opiate receptors: a novel mechanism for regulating the central norepinephrine system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6516–6525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0390-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon MS, Seo YJ, Shim EJ, Choi SS, Lee JY, Suh HW. The effect of single or repeated restraint stress on several signal molecules in paraventricular nucleus, arcuate nucleus and locus coeurleus. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Morilak DA. Norepinephrine release in medial amygdala facilitates activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in response to acute immobilisation stress. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:308–314. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Fornal C, Jacobs BL. Effects of physiological manipulations on locus coeruleus neuronal activity in freely moving cats. I Thermoregulatory challenge. Brain Res. 1987a;422:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilak DA, Fornal C, Jacobs BL. Effects of physiological manipulations on locus coeruleus neuronal activity in freely moving cats. II Cardiovascular challenge. Brain Res. 1987b;422:24–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacak K, McCarty R, Palkovits M, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Effects of immobilization on in vivo release of norepinephrine in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in conscious rats. Brain Res. 1995;688:242–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pert CB, Kuhar MJ, Snyder SH. Autoradiographic localization of the opiate receptor in rat brain. Life Sci. 1975;16:1849–1854. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(75)90289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smagin GN, Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ. Sodium nitroprusside infusions activate cortical and hypothalamic noradrenergic systems in rats. Neurosci Res Comm. 1994;14:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Smagin GN, Zhou J, Harris RB, Ryan DH. CRF receptor antagonist attenuates immobilization stress-induced norepinephrine release in the prefrontal cortex in rats. Brain Res Bull. 1997;42:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(96)00368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder K, Wang W-W, Han R, McFadden K, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the norepinephrine nucleus, locus coeruleus facilitates behavioral flexibility. Neuropsychopharmacology. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.218. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Hartman BK. The central adrenergic system. An immunofluorescence study of the location of cell bodies and their efferent connections in the rat using dopamine-B-hydroxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol. 1976;163:467–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo ST, Blier P. Serotonin (1A) receptor ligands act on norepinephrine neuron firing through excitatory amino acid and GABA(A) receptors: a microiontophoretic study in the rat locus coeruleus. Synapse. 2001;42:203–212. doi: 10.1002/syn.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempel A, Zukin RS. Neuroanatomical patterns of the μ, d and k opioid receptors of rat brain as determined by quantitative in vitro autoradiography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:4308–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher M, Cohen JD, Servan-Schreiber D, Rajkowski J, Aston-Jones G. The role of locus coeruleus in the regulation of cognitive performance. Science. 1999;283:549–554. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor disrupts sensory responses of brain noradrenergic neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000124700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing factor increases tonic but not sensory-evoked activity of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in unanesthetized rats. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1016–1025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01016.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis AL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E. Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Corticotropin-releasing factor: Evidence for a neurotransmitter role in the locus coeruleus during hemodynamic stress. Neuroendocrinology. 1988a;48:674–677. doi: 10.1159/000125081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Wehby RG. Morphine effects on locus coeruleus neurons are dependent on the state of arousal and availability of external stimuli: Studies in anesthetized and unanesthetized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988b;244:1178–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Branchereau P, Pickel VM. Morphologically heterogeneous met-enkephalin terminals form synapses with tyrosine hydroxylase containing dendrites in the rat nucleus locus coeruleus: an immuno-electron microscopic analysis. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:423–438. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Saunders A, Commons KG, Liu XB, Peoples J. Evidence for coexistence of enkephalin and glutamate in axon terminals and cellular sites for functional interactions of their receptors in the rat locus coeruleus. J Comp Neurol. 2000;417:103–114. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000131)417:1<103::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, North RA. Opiate receptor interactions on single locus coeruleus neurons. Mol Pharm. 1984;26:489–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Zhou W. Morphine induces synchronous oscillatory discharges in the rat locus coeruleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]