Abstract

D2-like agonists such as quinpirole maintain responding in monkeys, rats, and mice when they are substituted for cocaine. The following studies examined the influence of operant history and cocaine-paired stimuli (CS) on quinpirole-maintained responding in rats trained to nosepoke for cocaine. Upon acquisition of responding for cocaine, substitutions were performed in the presence or absence of injection-CS pairings. Although cocaine maintained responding regardless of whether injections were accompanied by CSs, quinpirole maintained responding only when CSs were paired with injections. To assess the influence of operant history, injections of cocaine, quinpirole, remifentanil, nicotine, or saline were made available on a previously inactive lever, while nosepokes continued to result in CS presentation. Although responding was reallocated from the nosepoke to the lever when cocaine or remifentanil were available, lever presses remained low, and nosepoking persisted when quinpirole or nicotine were made contingent upon lever presses. Finally, quinpirole pretreatments resulted in high rates of nosepoking when nosepokes resulted in CS presentation alone, but failed to maintain nosepoking when the CS was omitted. Together these results suggest that quinpirole's response-maintaining effects are primarily mediated by an enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing effects of previously cocaine-paired stimuli, and not a reinforcing effect of quinpirole.

Keywords: Quinpirole, Cocaine, Nicotine, Self-Administration, Conditioned Reinforcement, Compulsion, Dopamine D2, Dopamine D3

Introduction

A growing body of evidence suggests that dopamine D2 and D3 receptors play important roles in a variety of aspects of drug addiction, and other compulsive behaviors (e.g., Heidbreder et al., 2005; Newman et al., 2005; Everitt et al., 2008). For instance, with respect to drug addiction, positron emission tomography (PET) studies in humans, monkeys, and rats have shown that lower levels of striatal D2-like receptor availability are not only correlated with the positive subjective (Volkow et al., 1999) and reinforcing effects (Morgan et al., 2002) of psychostimulants, such as cocaine, but also personality traits, such as impulsivity, that may predispose individuals to abuse cocaine (Dalley et al., 2007). Additionaly, a variety of D3 and D2/D3 antagonists and partial agonists have been shown to inhibit the cue-induced reinstatement of responding for cocaine (Gilbert et al., 2005; Gal and Gyertyan, 2006; Cervo et al., 2007), as well as cue-maintained responding in second-order schedules of cocaine reinforcement (Pilla et al., 1999; Di Ciano et al., 2003), suggesting that the D3 and D2 receptors may also play an important role in conditioned reinforcement.

Alternatively, a growing number of reports have linked the use of D2-like agonists in the treatment of Parkinson's disease or restless leg syndrome with the development of compulsive patterns of goal-directed behaviors, such as gambling, shopping, eating, and hypersexuality (e.g., Weintraub et al., 2006; Voon and Fox, 2007). When taken together with the findings that the D2 and D3 receptors play important roles in both the primary reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, as well as the conditioned reinforcing effects of stimuli that have been associated with cocaine, these findings suggest that D2 and D3 receptors may be intimately involved in the development or maintenance of compulsive or habitually-maintained patterns of goal-directed behaviors associated with both drug and behavioral addictions.

This notion is further supported by the effects of D2-like agonists in a variety of animal models of drug abuse and compulsion. For instance, D2-like agonists have been shown to maintain self-administration behavior in monkeys (Woolverton et al., 1984; Nader and Mach, 1996; Sinnott et al., 1999), rats (Caine and Koob, 1993; Collins and Woods, 2007), and mice (Caine et al., 2002), suggesting that they possess reinforcing properties in laboratory animals. However, the fact that the response-maintaining effects of these agonists are observed only if the animals have a relatively specific history of drug-reinforcement (Collins and Woods, 2007), suggests that D2-like agonists are not functioning as traditional drug reinforcers. In addition to these effects, D2-like agonists, such as quinpirole, have been shown to induce compulsive checking behavior (e.g., Szechtman et al., 1998; Dvorkin et al., 2006), excessive responding for water, an effect that persisted even when water was freely available (Amato et al., 2006), perseverative responding in the absence of primary reinforcement (Kurylo and Tanguay, 2003; Kurylo, 2004), and excessive responding in a signal attenuation model of obsessive compulsive disorder (Joel et al., 2001), suggesting that D2 and/or D3 receptors may be involved in the development of a variety of compulsive-like behaviors in rats.

Although humans do not generally abuse D2-like agonists (except patients with dopamine dysregulation syndrome; O'Sullivan et al., 2009), a variety of compulsive behaviors have been reported in patients being treated with D2-like agonists, including pramipexole and ropinirole. Although originally described as an increased occurrence of pathological gambling in Parkinson's patients (Driver-Dunckley et al., 2003), a variety of other compulsive behaviors have been reported in Parkinson's, restless-leg, and fibromyalgia patients being treated with pramipexole or ropinirole, including compulsive eating, compulsive shopping, and hypersexuality. Although the overall prevalence of such compulsive behaviors is currently estimated to range from 0.7 to 14% (e.g., Voon et al., 2006; Driver-Dunckley et al., 2007; Weintraub, 2008; Holman, 2009), specific risk factors for the development of such compulsive behaviors have yet to be fully elucidated. However, it is thought that male sex, younger age of disease onset, and histories of drug or alcohol abuse increase the likelihood for developing an impulse control disorder (e.g., Voon and Fox, 2007; Weintraub, 2008). Although the mechanisms responsible for the development of impulse control disorders are currently unknown, it is important to note that all of these behaviors are goal-directed behaviors, and therefore are likely influenced by environmental stimuli. Moreover, the fact that these problematic behaviors typically resolve following dose reduction or cessation of treatment with pramipexole or ropinirole, suggests that these D3/D2 agonists play a causal role in the development and/or maintenance of these compulsive behaviors.

When taken together with the evidence linking D2/D3 receptors to the primary reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, and conditioned reinforcing effects of stimuli associated with their use, the development of impulse control disorders in patients and induction of compulsive-like behaviors in animals treated with D2-like agonists represents a very intriguing psychopharmacological phenomenon. Moreover, the elucidation of the variables that underlie these behavioral effects may provide valuable insight into the mechanisms involved in the development of the compulsive and habitual aspects of drug and behavioral addictions. Perhaps, one of the more interesting differences between the effects of D2-like agonists in laboratory animals and humans is the apparent divergence when it comes to their reinforcing effects. Although it is possible that D2-like agonists possess reinforcing effects in laboratory animals, but not humans, it is also possible that the response-maintaining effects observed in laboratory animals are mediated by other, direct-effects of D2-like agonists. Thus, a series of experiments was designed to elucidate the variables that are involved in the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in rats that have been trained to respond for cocaine. We first examined the influence of the stimuli that were previously paired with cocaine-reinforcement (CS) on the capacity of quinpirole to maintain responding in a direct substitution procedure, as well as whether quinpirole would maintain responding when substituted for cocaine on a previously unreinforced manipulandum (i.e., new response acquisition).

Finally, we determined whether the CS presentation was necessary and sufficient to establish the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole following non-contingent administration of quinpirole prior to sessions in which responding resulted in the presentation of the CS only. Together, the findings of these studies suggest that the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole are mediated by an enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing value of the CS and not a primary reinforcing effect of quinpirole itself. Moreover, these studies suggest that the development and maintenance of compulsive behaviors in patients being treated with D2-like agonists, such as pramipexole and ropinirole, may be driven, at least in part, by an D2/D3-mediated enhancement of conditioned reinforcers associated with the problematic behaviors.

Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (350–375 g) were obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in a temperature and humidity controlled environment, on a 12-h dark/light cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM with free access to food and water. Twenty-four hrs prior to the initiation of operant training, all rats were restricted to ~20g of food per day, sufficient to maintain rats at ~80% of their free feeding weight for the duration of the experiments. All studies were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health, and all experimental procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on the Use and Care of Animals.

Surgery

Rats were surgically prepared with a chronic indwelling femoral catheter in the left femoral vein under ketamine:xylazine (90:10 mg/kg; i.p.) anesthesia. Catheters were tunneled under the skin and attached to stainless steel tubing, exiting the back through a metal tether button that was sutured to the muscle between the scapula. Rats were allowed 5–7 days to recover from surgery prior to the start of operant training. Catheters were flushed with 0.2 ml of heparinized saline (100 U/ml) prior to the start of each self-administration session as well as after the completion of sessions to insure patency.

Apparatus

All experimental sessions were conducted in operant conditioning chambers (30.5 cm W × 24 cm D × 21 cm H; Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT) placed inside sound attenuating cubicles. Each chamber was equipped with a nosepoke device and a lever located on one wall (ENV-110M, ENV-114BM; Med Associates Inc.), and a white houselight located on the opposite wall. The nosepoke could be illuminated with a yellow stimulus light, and a set of green, yellow, and red LED stimulus lights was located above both the nosepoke and lever. Drug solutions were delivered by an air driven pneumatic syringe pump (IITC, Woodland Hills, CA) through Tygon® tubing connected to a stainless steel fluid swivel (Instech Laboratories Inc, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and spring tether which was held in place by a counterbalanced arm. For food self-administration sessions, chambers were also equipped with a liquid food dipper with a 50 μl dipper cup (E14-05; Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA).

Operant training procedures

Prior to any experimental manipulations, 15 groups of 6 rats were trained to nosepoke for 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine on a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement during daily 90-min sessions, and 3 groups of 6 rats were trained to respond for 10-sec access to 50 μl of liquid food (Ensure®). Although levers were present in the chambers during training, lever responses had no scheduled consequence (inactive manipulandum). Illumination of the yellow nosepoke light signaled cocaine (or food) availability, and subsequent nosepokes resulted in an injection (100 βl/kg/0.5 seconds), or 10 sec access to liquid food. Injections were paired with the illumination of a green LED located above the nosepoke followed by a 5-sec timeout (TO) during which time the houselight was illuminated, and all other stimuli were extinguished. Food presentation was also paired with the illumination of a green LED located above the nosepoke as well as the illumination of a white light located inside the dipper aperture, and was followed by a 5-sec TO during which time the houselight was illuminated, and all other stimuli were extinguished. During the TO periods, nosepoke and lever responses were recorded but had no consequence. Following at least 10 sessions, and upon stabilization of responding, defined as three consecutive sessions with less than a 20% difference and no increasing or decreasing trend in responding, rats were randomly assigned to either substitution (11 groups of 6 cocaine-trained rats), or pretreatment studies (4 groups of 6 cocaine-trained rats, and 3 groups of 6 food-trained rats).

Substitution studies

To assess the influence of operant history and CS presentation on the capacity of quinpirole to maintain responding, 11 groups of 6 cocaine-trained rats were assigned to one of three conditions: CS-NS Substitution (3 groups of 6 rats), No CS Substitution (3 groups of 6 rats), or New Response Substitution (5 groups of 6 rats). Substitutions were performed for 7 consecutive days, during which time nosepokes and lever presses were reinforced under a concurrent FR1TO5(nosepoke):FR1TO5(lever) schedule of reinforcement (see below for specific contingencies). Following substitutions, all rats were returned to the baseline schedule of reinforcement (nosepokeing on FR1TO5 for 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine) for a period of 5 days thereafter.

CS-NS Substitution

Substitutions were performed in three groups of 6 rats, with the illumination of the yellow LEDs inside the nosepoke and above the lever signaling the start of the session. Nosepokes resulted in an injection of 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine (1 group of 6 rats), 0.032 mg/kg/inj quinpirole (1 group of 6 rats), or saline (1 group of 6 rats), and all injections were paired with CS presentation (i.e., a 0.5-sec flash of the green LED above the nosepoke, and followed by a 5-sec TO signaled by the illumination of the houselight). Lever presses now resulted in the presentation of a novel stimulus (NS) change (i.e., illumination of the green, yellow, and red LEDs above the lever, followed by a 5-sec TO signaled by the flashing of the houselight at 1-sec intervals).

No CS Substitution

Substitutions were performed in three groups of 6 rats. During the No CS Substitution the start of the session was not signaled (i.e., the yellow LEDs inside the nosepoke and above the lever were not illuminated). Nosepokes resulted in an injection of 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine (1 group of 6 rats), 0.032 mg/kg/inj quinpirole (1 group of 6 rats), or saline (1 group of 6 rats), each followed by a 5-sec TO although the CS was not presented in conjunction with injections (i.e., the green LED above the nosepoke was not illuminated, and the houselight was not illuminated during the TO). Similar to the CS-NS Substitution, lever presses now resulted in a 5-sec TO, however, no stimulus change was associated with this TO (i.e., un-signaled TO).

New Response Substitution

Substitutions were performed in 5 groups of 6 rats, with the illumination of the yellow LEDs inside the nosepoke and above the lever signaling the start of the session. Nosepokes resulted in CS presentation, but no longer resulted in injections. Lever presses now resulted in the injection of 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine (1 group of 6 rats), 0.032 mg/kg/inj quinpirole (1 group of 6 rats), 0.0032 mg/kg/inj remifentanil (1 group of 6 rats), 0.064 mg/kg/inj nicotine (1 group of 6 rats), or saline (1 group of 6 rats), and all injections were paired with the unfamiliar NS (i.e., a 0.5-sec flash of the green, yellow, and red LEDs above the lever, followed by a 5-sec TO signaled by the flashing of the houselight at 1-sec intervals). Remifentanil, at a dose that has been shown to maintain responding in naïve rats (Collins and Woods, 2007), a μ-opioid agonist, was used to assess the capacity of a novel drug reinforcer to maintain responding on a previously inactive lever. Nicotine, at a dose of 0.064 mg/kg/inj, was chosen based on its capacity to maintain responding for its injection, as well as for visual stimuli (Donny et al., 2003).

Pretreatment studies

A total of 4 groups of 6 cocaine-trained rats, and 3 groups of 6 food-trained rats were used to investigate the influence of non-contingent quinpirole or cocaine on responding maintained by CS and NS presentation only. Pretreatments occurred immediately prior to 7 consecutive sessions in which responding was reinforced under a concurrent FR1TO5:FR1TO5 schedule of reinforcement, with nosepoke responding resulting in CS (cocaine- or food-paired stimuli) presentation, and lever presses resulting in NS presentation. Two groups of 6 rats (1 cocaine-trained and 1 food-trained) were pretreated with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.), 2 groups of 6 rats (1 cocaine-trained and 1 food-trained) were pretreated with quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.), and 2 groups of 6 rats (1 cocaine-trained and 1 food-trained) were pretreated with saline. Another group of 6 cocaine-trained rats were pretreated with quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.) prior to sessions in which CS and NS presentations were omitted, and nosepokes and lever presses resulted in a 5-sec unsignaled TO. The dose of cocaine (10 mg/kg; i.p.) was chosen based on its capacity to serve as a discriminative stimulus (Li et al., 2006) and reinstate responding for cocaine-paired cues (Lu et al., 2004). The dose of quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.) was chosen based on the fact that it corresponded to the lower end of the asymptotic portion of the correlation of total quinpirole intake, and CS-maintained responding as shown in Figure 3. In all cases, responding during TOs was recorded, but had no scheduled consequence. Upon completion of the pretreatment studies, all rats were returned to their training contingencies, and allowed to respond for 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine or food for a period of 5 days.

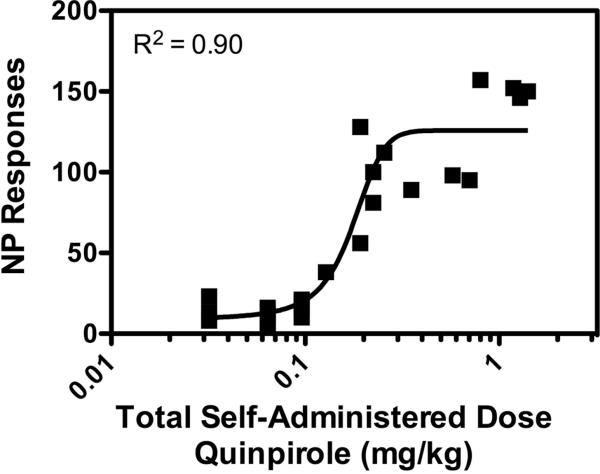

Figure 3.

Nosepoke responses that resulted in CS presentation, as a function of the total self-administered dose of quinpirole resulting from lever presses during the New Resp Substitution. Data were fit with nonlinear regression using a variable slope sigmoid equation (GraphPad Prism).

Drugs

Cocaine was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD), remifentanil, purchased as Ultiva® (GlaxoSmithKline), was obtained from the University of Michigan Hospital Pharmacy, (−)-nicotine bitartrate, and quinpirole (trans-(−)-(4aR)-4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a,9-octahydro-5-propyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-g]quinoline hydrochloride) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Nicotine doses are expressed as mg/kg of base, whereas doses of cocaine, remifentanil, and quinpirole were expressed as mg/kg of the salt. All drugs were dissolved in physiologic saline, and administered i.v. in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg over a period of 0.5 sec. Pretreatments were administered in a volume of 1 ml/kg via the i.p. (cocaine) or s.c. (quinpirole) route.

Data analysis

Responses represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), n=6, number of nosepokes or lever presses that occurred during the active portion of the sessions, but do not include responses made during reinforcement or scheduled TO periods. Significant differences in baseline responding or responding maintained during substitutions was determined using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Bonferroni tests (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) to assess differences in responding between the groups for each session. Significant changes in nosepoke or lever responding over the 7 days of the substitutions were determined using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett's tests (GraphPad Prism) to determine if responses on the nosepoke, or lever were significantly different from the baseline condition. Significant effects of pretreatment (cocaine or quinpirole) on responding for stimuli that were previously paired with reinforcement were determined using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Bonferroni tests (GraphPad Prism) to assess differences in responding for each session as compared to saline pretreated rats. Similarly, significant differences in the effects of quinpirole pretreatment on responding that resulted in CS presentation or no stimulus change were determined using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Bonferroni tests (GraphPad Prism) to assess differences in responding between the groups for each session. Correlation of total self-administered quinpirole dose and the number or nosepokes were fit with nonlinear regression using a variable slope sigmoid equation (GraphPad Prism).

Results

Acquisition of responding for cocaine

Experimentally naïve rats readily acquired nosepoke responding for 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine, and generally reached stable responding within the 14 sessions (12.8 ± 0.2 sessions on average) with responding occurring almost exclusively on the nosepoke (28.9 ± 0.3 nosepokes vs. 0.3 ± 0.1 lever presses) during the last 5 baseline sessions. Similarly, responding occurred almost exclusively on the nosepoke (27.9 ± 5.5 nosepokes vs. 1.6 ± 0.2 lever presses) during the last 5 sessions of the 14-day acquisition period for food-trained rats. These patterns of responding indicate that behavior was controlled almost entirely by cocaine injections during the baseline conditions.

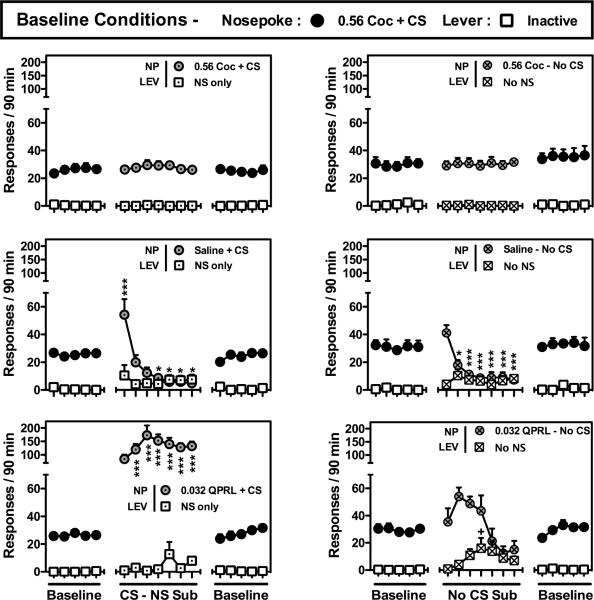

Influence of Cocaine-Paired Stimuli

When cocaine (0.56 mg/kg/inj) was available for injection, nosepoke responding occurred at baseline-like levels, regardless of whether or not the CS was paired with injection (Fig. 1; top panels). Responses occurred almost exclusively on the nosepoke, and few were directed at the lever that now resulted in NS presentation. Substitution of saline for cocaine resulted in progressive decreases in the amount of nosepoke responding during both the 7-day CS-NS [F(7,35)=13.84; p<0.001], and No CS [F(7,35)=15.62; p<0.001] substitutions (Fig. 1; center panels). However, when saline injections were paired with CS presentation, nosepoke responding occurred at rates significantly greater than those maintained by 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine during the first substitution session (Fig. 1; center left panel), an effect that was not observed when CS presentation was omitted (Fig. 1; center right panel). Moreover, although decreases in nosepoke responding were observed in both the CS-NS, and No CS Substitutions, significant decreases in nosepoke responding were observed sooner when saline injections were not paired with CS presentation (second session), as compared to when saline injections were delivered in conjunction with CS presentation (fourth session). Slight increases in lever responses were observed during both saline substitutions; however, these low levels of responding were not significantly different from baseline regardless of whether or not the NS was presented.

Figure 1.

Effects of the cocaine-paired CS on responding maintained by 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine (top panels), saline (middle panels), or 0.032 mg/kg/inj quinpirole (bottom panels). During the Baseline portions of each experimental condition nosepokes (black circles) resulted in 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine paired with CS presentation, and lever presses (open squares) were inactive. CS-NS Substitution; Left Panels) Nosepokes (gray dotted circles) resulted in the injection of cocaine (0.56 mg/kg/inj), saline, or quinpirole (0.032 mg/kg/inj) delivered in conjunction with the cocaine-paired CS (i.e., 0.5-sec illumination of a green LED above the nosepoke, followed by a 5-sec TO with a solid houselight). Lever presses (open dotted squares) resulted in NS presentation (i.e., a 0.5-sec illumination of a green, yellow, and red LED above the lever, followed by a 5-sec TO with a flashing houselight). No CS Substitution; Right Panels) Nosepokes (gray crossed circles) resulted in the injection of cocaine (0.56 mg/kg/inj), saline, or quinpirole (0.032 mg/kg/inj) but no CS presentation (i.e., a 5-sec unsignaled TO), whereas lever presses (open crossed squares) resulted in a 5-sec unsignaled TO. Responses represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n=6) number of nosepokes or lever presses made during the active portion of each 90-min session. ***, p<0.001; **,p<0.01; *, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of nosepokes during the substitution as compared to the number of nosepokes during the last baseline session as determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's tests. +++, p<0.001; ++, p<0.01; +, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of lever presses during the substitution as compared to the number of lever presses during the last baseline session as determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's tests.

Unlike with the cocaine and saline substitutions, the presence or absence of CS had a dramatic effect on the amount of nosepoke responding maintained by 0.032 mg/kg/inj quinpirole. When the CS was presented in conjunction with quinpirole injections, nosepoke responding occurred at levels significantly greater than during the baseline condition [F(7,35)=8.80; p<0.001], with post-hoc analysis revealing significant increases in nosepoke responding during sessions 2 to 7, whereas lever responding was unaffected (Fig. 1; bottom left panel). Alternatively, when quinpirole injections were not paired with CS presentation, responding on both the nosepoke [F(7,35)=6.3; p<0.001] and the lever [F(7,35)=2.47; p<0.05] were significantly different from baseline (Fig. 1; bottom right panel), with increased levels of lever pressing, and saline-like levels of nosepoking observed over the last three days of the substitution. Moreover, a two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both CS [F(1,60)=28.15; p<0.001] and time [F(6,60)=4.52; p<0.001], with significantly more nosepokes observed when quinpirole injections were paired with the CS during sessions 3 to 7 of the substitution as compared to the No CS substitution. Taken together, these findings not only suggest that the CS took on conditioned reinforcing properties following repeated pairings with cocaine injections, but also that response-maintaining effects of quinpirole are dependent upon a quinpirole-CS interaction, and only observed when quinpirole injections are delivered in conjunction with the cocaine-paired CS.

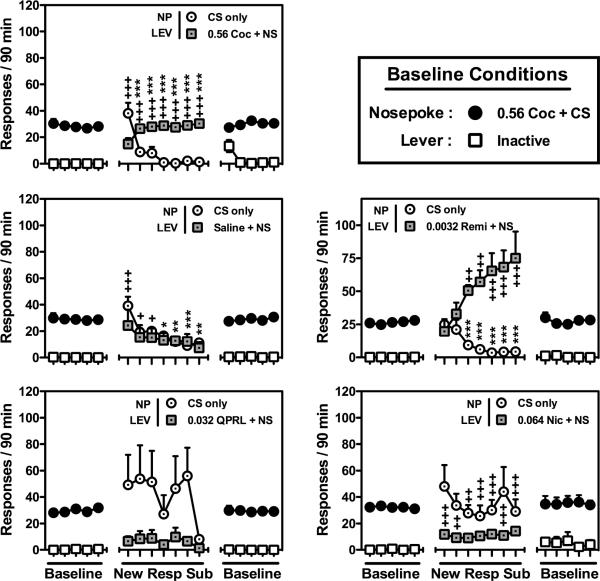

New Response Acquisition

As shown in Figure 2, when cocaine injections were scheduled contingent upon lever responding, rats readily reallocated their responding from the nosepoke to the lever. Lever responding was significantly increased [F(7,35)=26.41; p<0.001] from day 1 to 7, whereas nosepoke responding was significantly decreased [F(7,35)=20.37; p<0.001] from day 2 to 7 of the substitution as compared to the respective baseline levels of nosepoke and lever responding. Baseline patterns of responding recovered when rats were returned to their original reinforcement schedule. Similar patterns of nosepoke and lever responding were observed when 0.0032 mg/kg/inj remifentanil was substituted on the lever, following training for cocaine-reinforcement on the nosepoke, with significant increases in lever presses [F(7,35)=11.59; p<0.001], and significant decreases in nosepoke responding [F(7,35)=7.08; p<0.001] occurring over the course of the 7-day substitution.

Figure 2.

Responding maintained during substitutions in which injections were paired with the NS, and delivered contingent upon a previously non-reinforced lever press response, whereas nosepoke responses continued to produce the cocaine-paired CS, but no longer resulted in injections. During the Baseline portions of each experimental condition nosepokes (black circles) resulted in 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine paired with CS presentation, and lever presses (open squares) were inactive. During the New Resp Sub, nosepokes (open dotted circles) resulted CS presentation, whereas lever presses (gray dotted squares) resulted in cocaine (0.56 mg/kg/inj), remifentanil (0.0032 mg/kg/inj), nicotine (0.064 mg/kg/inj), quinpirole (0.032 mg/kg/inj), or saline paired with NS presentation. Responses represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n=6) number of nosepokes or lever presses made during the active portion of each 90-min session. ***, p<0.001; **,p<0.01; *, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of nosepokes during the substitution as compared to the number of nosepokes during the last baseline session as determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's tests. +++, p<0.001; ++, p<0.01; +, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of lever presses during the substitution as compared to the number of lever presses during the last baseline session as determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's tests.

When lever presses resulted in saline injections, following training for cocaine-reinforcement on the nosepoke (Fig. 2; left center panel), the pattern of nosepoke responding was similar to what was observed during the CS-NS (Fig. 1; center left panel), with nosepoke responding during the first day of the substitution occurring at rates significantly greater than baseline, and progressive decreases in nosepokes for the remainder of the 7-day substitution [F(7,35)=10.68; p<0.001]. Similar to the CS-NS substitution, rates of nosepoke responding for CS presentation remained at, or above those maintained by 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine (baseline) for the first three days of the substitution, with significant decreases in nosepoke responding observed from sessions 4 to 7. However, unlike with the CS-NS, and No CS substitutions, lever presses were also significantly different than baseline [F(7,35)=3.67; p<0.01], with elevated levels of responding observed during the first 3 days of the substitution, and baseline-like levels of lever responding observed for the remainder of the 7-day substitution.

Unlike the patterns of responding observed when cocaine, remifentanil, or saline was available for injection, a different pattern of responding was observed when lever presses resulted in nicotine injection (0.064 mg/kg/inj), following training for cocaine-reinforcement on the nosepoke. Although lever presses were significantly increased when they resulted in nicotine injections [Fig. 2, bottom right panel; F(7,35)=7.78; p<0.001], nosepoke responding also remained elevated and no different from baseline, throughout the 7-day substitution. A similar pattern of responding was observed when lever presses resulted in quinpirole injection. Lever presses remained low when they resulted in quinpirole injections paired with the NS, and nosepokes remained elevated when they resulted in CS presentation, but no injection. However, unlike the stable rates of lever presses observed with nicotine, lever presses occurred at irregular rates when quinpirole was available for injection, and were not significantly different than during baseline, when the lever was inactive. Moreover, although nosepokes were elevated for the first 6 sessions, a large decrease in nosepoking was observed during the seventh session. Interestingly, the amount of nosepoke responding (that resulted in CS presentation) was highly correlated with the total dose of quinpirole earned during the session with lower levels of lever pressing resulting in lower levels of nosepoking, and higher levels of lever pressing resulting in higher levels of nosepoke responding (Figure 3). Taken together, these patterns of responding indicate that although behavior was controlled almost exclusively by injections when cocaine or remifentanil were available, behavior was controlled by both the injection, and CS presentation when nicotine was available, and primarily by CS presentation, and not the injection, when quinpirole was available for injection.

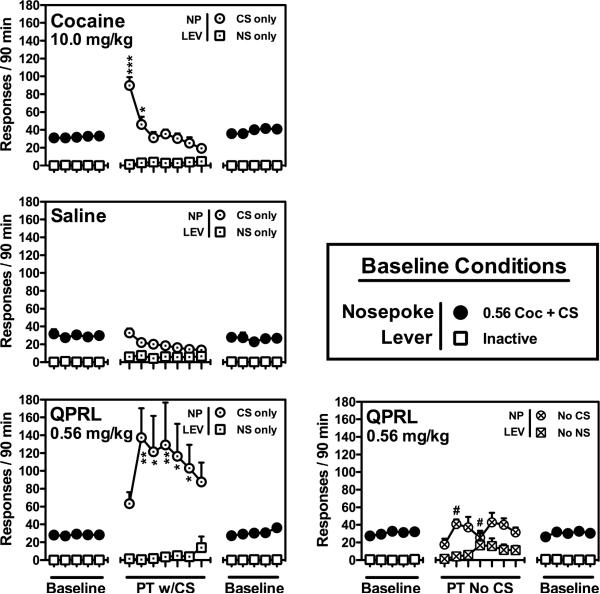

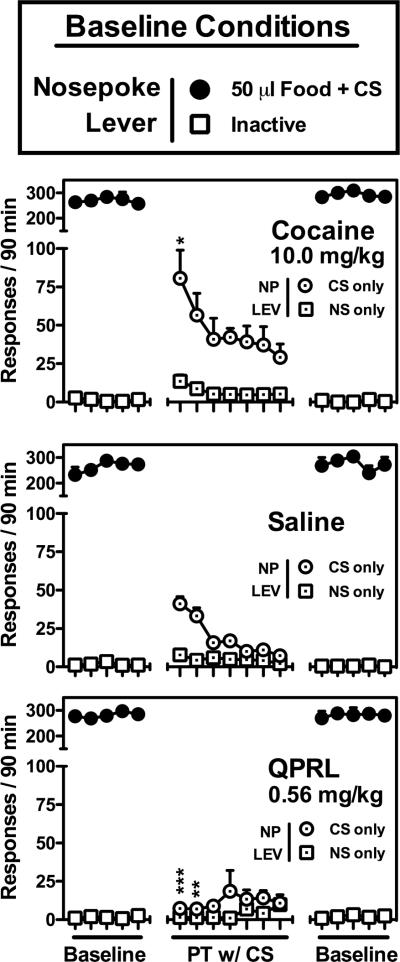

Effects of Pretreatments on Responding for CS Presentation

Figure 4 shows the effects of pretreatments with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p), quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.), or saline on nosepoke responding for the presentation of the cocaine-paired CS, and lever pressing for NS presentation. When rats were pretreated with saline nosepoke responding for the CS persisted at baseline-like levels for the first three sessions, with progressive decreases in nosepoke observed thereafter (Fig. 4; center left panel). Lever responding for the NS remained low, and was no different from baseline at any time. Nosepoke responding for CS presentation was significantly higher than that observed in the saline-treated rats following the first two cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.) pretreatments [main effect of drug: F(1,60)=21.85; p<0.001; and time: F(6,60)=20.84; p<0.001], with progressive decreases in nosepoke responding observed for the remainder of the 7-day manipulation(Fig. 4; top left panel). However, unlike with saline, nosepoke responding for the CS persisted at rates similar to those maintained by 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine throughout the 7-day cocaine pretreatment manipulation. Lever presses remained low, and were no different from baseline at any point.

Figure 4.

Effects of pretreatment with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.), quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.), or saline on nosepoke responding for cocaine-paired CS presentation, and lever pressing for NS presentation. During the Baseline portions of each experimental condition nosepokes (black circles) resulted in 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine paired with CS presentation, and lever presses (open squares) were inactive. During the PT w/CS phase Left Panels) nosepokes (open dotted circles) resulted in presentation of the cocaine-paired CS, whereas lever presses (open dotted squares) resulted in NS presentation. During the PT No CS phase Right Panel) nosepokes (open crossed circles), and lever presses (open crossed squares) resulted in an unsignaled 5-sec TO, but no stimuli change. Responses represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n=6) number of nosepokes or lever presses made during the active portion of each 90-min session. ***, p<0.001; **,p<0.01; *, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of nosepokes during the pretreatment phase of the cocaine-, or quinpirole-treated groups as compared to the number of nosepokes during the pretreatment phase of the saline-treated group as determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests. +++, p<0.001; ++, p<0.01; +, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of lever presses during the pretreatment phase of the cocaine-, or quinpirole-treated groups as compared to the number of nosepokes during the pretreatment phase of the saline-treated group as determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests. #, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of nosepokes during the PT w/CS phase and PT No CS phase of the quinpirole-treated groups as determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests.

Unlike the progressive decreases in CS-maintained responding observed following cocaine and saline pretreatments, when cocaine-trained rats were pretreated with quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.) nosepoke responding for CS presentation occurred at rates higher than those observed with either saline [main effect of drug: F(1,60)=10.05; p<0.01], or cocaine [main effect of drug: F(1,60)=5.87; p<0.05], with rates of nosepoke responding for the CS significantly higher than those observed in saline-treated rats on days 2 to 6 of the manipulation (Fig. 4; bottom left panel). As with saline and cocaine pretreatments, lever presses remained low, and were no different from baseline at any point. The effects of quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.) were also assessed during sessions in which CS, and NS presentations were omitted following nosepoke or lever responding, respectively (Figure 4; bottom right panel). Unlike when the nosepokes resulted in CS presentation, when CSs were omitted quinpirole pretreatments, an effect that was dependent upon both CS [F(1,60)=6.74; p<0.05], and time [F(6,60)=2.71; p<0.05]. Although slight increases in lever pressing were observed, these low levels were no different than those observed during the baseline condition.

The effects of pretreatment with cocaine, quinpirole, or saline on nosepoke responding for the food-paired CS, and lever pressing for NS presentation are shown in Figure 5. Pretreatment with saline resulted in a progressive decrease in nosepoke responding for CS presentation (Fig. 5; center panel). Although this pattern of responding was similar to that observed following saline pretreatments in cocaine-trained rats, CS-maintained nosepoking responding was significantly lower than the rates of responding that were maintained by food throughout the 7-day manipulation [F(7,35)=61.62; p<0.001], whereas lever presses remained low, and were no different from baseline at any point. Similar to the effects of cocaine on responding for the cocaine-paired CS, pretreatment with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.) resulted in significantly more nosepoke responding for the food-paired CS following the first pretreatment as compared to the saline-treated rats [Fig. 5; top panel; main effect of drug: F(1,60)=6.25; p<0.05; main effect of time: F(6,60)=15.27; p<0.001], with progressive decreases in nosepoke responding thereafter. Although the pattern of nosepoke responding for the food-paired CS was similar to the observed with when nosepoke responding resulted in the cocaine-paired CS, nosepoke responding occurred at rates significantly lower than those maintained by food throughout the 7-day cocaine pretreatment manipulation. Lever presses remained low, and were no different from baseline at any point.

Figure 5.

Effects of pretreatment with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.), quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.), or saline on nosepoke responding for food-paired CS presentation, and lever pressing for NS presentation. During the Baseline portions of each experimental condition nosepokes (black circles) resulted in 10-sec access to 50 μl of liquid food paired with CS presentation, and lever presses (open squares) were inactive. During the PT w/CS phase Left Panels) nosepokes (open dotted circles) resulted in presentation of the food-paired CS, whereas lever presses (open dotted squares) resulted in NS presentation. Responses represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n=6) number of nosepokes or lever presses made during the active portion of each 90-min session. ***, p<0.001; **,p<0.01; *, p<0.05; represents significant differences in the number of lever presses during the pretreatment phase of the cocaine-, or quinpirole-treated groups as compared to the number of nosepokes during the pretreatment phase of the saline-treated group as determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests.

Unlike cocaine and saline, which had similar effects on nosepoke responding for the presentation of cocaine- and food-paired CSs, a much different pattern of responding was observed following pretreatment with quinpirole (0.56 mg/kg; s.c.) when nosepokes resulted in the food-paired CS (Fig 5; bottom panel). Unlike the high rates of nosepoking that were observed when responding resulted in the cocaine-paired CS, pretreatment with quinpirole failed to stimulate nosepoking when responding resulted in the CS that was previously paired with food-reinforcement, with rates of nosepoke responding at, or below the those observed following saline pretreatment throughout the 7-day manipulation. Lever presses remained low, and were no different from baseline at any point. When taken together with the results of the substitution studies, these findings indicate that the response contingent presentation of the CS is both necessary, and sufficient for response-maintaining effects of quinpirole with persistent enhancements in responding observed only if responding results in the presentation of the stimuli that had been previously paired with cocaine injection (but not food presentation); an effect that was observed following both response-contingent and non-contingent quinpirole administration.

Discussion

Despite the fact that humans rarely abuse D2-like agonists such as pramipexole or ropinirole, a wide variety of D2-like agonists have been shown to maintain responding when substituted for cocaine in monkeys, rats, and mice, suggesting that they possess reinforcing properties in laboratory animals. However, we have previously shown that quinpirole will maintain responding in cocaine- and remifentanil-trained rats, but not ketamine- or food-trained rats, or in rats with a history of non-contingent cocaine administration, suggesting that the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole are highly dependent upon reinforcement history (Collins and Woods, 2007). The current studies extended these findings by demonstrating that, although quinpirole maintained high rates of responding when injections were delivered in conjunction with the CS that was previously paired with cocaine reinforcement, quinpirole failed to maintain responding if CS presentation was omitted, or if quinpirole was substituted on a previously unreinforced manipulandum. When taken together with the finding that increases in responding that was reinforced by CS presentation alone were observed following both contingent and non-contingent quinpirole administration, these studies suggest that the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole are primarily dependent upon an enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing effects of the cocaine-paired CS, not a reinforcing effect of quinpirole. Moreover, the quinpirole-induced enhancement of the conditioned reinforcement may provide valuable insight into the mechanisms that underlie the development and maintenance of compulsive or habitual behaviors associated with drug and behavioral addictions in humans.

It has been well established that the repeated pairing of discrete stimuli with reinforcers can result in the stimuli taking on conditioned reinforcing properties (Fantino and Romanowich, 2007; Shahan and Podlesnik, 2008). With respect to drug reinforcement, conditioned reinforcers can aid not only in the acquisition and maintenance of drug self-administration behavior (Schenk and Partridge, 2001; Caggiula et al., 2002), but they are also capable of maintaining responding when primary reinforcers are delivered infrequently (Goldberg et al., 1981) and reinstating responding in the absence of the primary drug reinforcer (Kruzich et al., 2001; Di Ciano and Everitt, 2003).

Although the presence or absence of CS-injection pairings did not affect cocaine-maintained responding in animals that had already been trained to respond for cocaine, differences did emerge when cocaine was replaced by saline and rats were allowed to respond in the presence or absence of response contingent CS presentations. For instance, when saline injections were paired with CS presentation (CS-NS and New Resp), nosepoke responding during the initial substitution session occurred at rates significantly greater than those maintained by the primary reinforcer (0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine). Not only was this effect not observed when saline injections were delivered in the absence of CS presentation (No CS), but the omission of CS presentations also resulted in a more rapid decrease in nosepoke responding in the absence of the primary reinforcer, with significant decreases in nosepoke responding observed by the second session. Conversely, response contingent CS presentation maintained nosepoke responding at rates at, or above those maintained by 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine for at least three sessions; an effect that occurred whether saline injections were paired with CS presentation (CS-NS) or not (New Resp, and PT w/ CS in cocaine-trained rats). Together, these findings provide evidence that the repeated pairing with response contingent cocaine with the CS during self-administration training was sufficient for the CS to acquire conditioned reinforcing properties, and that these conditioned reinforcing properties were sufficient to maintain responding for at least three consecutive sessions.

Despite the fact that the reinforcing effects of the CS appeared to decrease when it was no longer paired with cocaine, quinpirole administration resulted in robust nosepoke responding for the CS that persisted throughout the 7-day manipulations suggestive of an enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS. For instance, although quinpirole maintained high rates of responding when injections were delivered in conjunction with CS presentation, quinpirole failed to maintain responding, with saline-like rates of responding observed over the last three days of the substitution when the CS was not paired with quinpirole injection. Importantly, quinpirole (0.032 mg/kg/inj) also failed to maintain responding in naïve rats even when injections were delivered in conjunction with the identical, but previously unpaired, stimuli (Collins and Woods, 2007), suggesting that the quinpirole-CS interaction is only capable of maintaining responding if the stimulus has been previously paired with a reinforcing event (e.g., response contingent cocaine administration). However, in these same studies quinpirole also failed to maintain responding in rats with a history of non-contingent cocaine paired with the identical stimuli (Collins and Woods, 2007), a classical conditioning paradigm that should have been sufficient to establish the conditioned reinforcing effects of the CS. Although this lack of effect is contrary to what would be predicted following the repeated pairing of a visual stimuli (CS) with non-contingent cocaine (US), it is likely that the non-contingent cocaine-CS pairings were delivered too frequently (i.e., every 120-sec; Collins and Woods, 2007), as similarly frequent cocaine-CS pairings (on average every 90-sec) have been shown to be insufficient to establish conditioned reinforcing effects (Kearns and Weiss, 2004), whereas conditioned reinforcing effects have been observed when separating the cocaine-CS pairings have been separated by a longer period of time (i.e., on average every 900-sec; Uslaner et al., 2006). Although it is unclear if quinpirole would enhance responding if non-contingent cocaine-CS pairings were separated by a longer period of time, the results of the current studies do suggest that the response contingent cocaine-CS pairings were sufficient for the CSs to acquire conditioned reinforcing effects, and that the quinpirole-induced enhancement of these conditioned reinforcing effects is responsible, in large part, for the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in laboratory animals.

Further evidence for this notion was provided by the results of the New Response Substitution, in which injections, paired with the NS, were delivered contingently upon lever presses, and CSs were presented contingent upon nosepoke responses. When 0.56 mg/kg/inj cocaine, or 0.0032 mg/kg/inj remifentanil was available for injection, rats readily reallocated their responding towards the lever, and away from the nosepoke, an effect that was not observed when saline was available for injection. Conversely, when nicotine injections were contingent upon lever presses, relatively low, but stable, rates of lever responding were observed, whereas nosepoke responding remained elevated despite the fact that nosepokes resulted only in CS presentation. Taken together, these findings indicate that rats are not only capable of learning a new response for novel drug reinforcer paired with novel stimuli, but that it is also possible to observe drug-CS interactions using this New Resp Substitution. For instance, although the fact that both cocaine and remifentanil maintained almost exclusive lever pressing suggests that responding is being maintained by the primary reinforcing effects of cocaine and remifentanil, the persistence of nosepoking for CS presentation during the nicotine substitution suggests something different. Similar to the findings of Caggiula and colleagues, the maintenance of both lever pressing (for nicotine) and nosepoking (for CSs) by nicotine suggests that nicotine possesses both a primary reinforcing effect, as well as a conditioned reinforcement enhancing effect (Donny et al., 2003; Chaudhri et al., 2006; Palmatier et al., 2007).

Interestingly, the pattern of responding observed when lever presses resulted in quinpirole injection and nosepokes resulted in CS presentation was more similar to that observed with nicotine than either cocaine or remifentanil. Although responding was less stable than nicotine-maintained responding, quinpirole did maintain low levels of lever presses, and elevated levels of nosepoking throughout the substitution period. However, unlike nicotine, quinpirole-maintained lever pressing was no different from baseline at any point of the 7-day substitution, suggesting that the primary reinforcing effects of quinpirole were insufficient for rats to learn a new response for quinpirole injections paired with an NS, even in rats with a history of cocaine reinforcement. Although these findings could also be interpreted as a perseveration on the response that was previously reinforced, nosepokes (for the CS) were highly correlated with the total self-administered dose of quinpirole. These findings not only provide further evidence of the importance of the quinpirole-CS interaction for the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole, but also suggest that it may reflect a dose-dependent, and direct effect of quinpirole on the conditioned reinforcing effects of the cocaine-paired CS.

To further test this notion, nosepoke responding for CS (either cocaine- or food-paired stimuli), and lever pressing for NS presentation were evaluated for 7 consecutive sessions following pretreatment with cocaine, quinpirole, or saline. In agreement with previous reports demonstrating the capacity of psychostimulants to enhance responding for conditioned reinforcers (e.g., Robbins, 1976; Beninger et al., 1981; Everitt and Robbins, 2000), pretreatment with cocaine (10.0 mg/kg; i.p.) resulted in a significant, and selective, increase in responding for CS presentation, suggestive of a cocaine-induced enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing value of the CS. Despite the fact that cocaine enhanced responding for both cocaine- and food-paired CSs, these effects were relatively short-lived, and were only observed during the first one (food), or two (cocaine) sessions in which cocaine was administered.

Compared to cocaine, pretreatment with quinpirole resulted in a more robust, and persistent enhancement of responding maintained by the cocaine-paired CS, with selective elevations in nosepoke responding observed throughout the 7-day manipulation. Moreover, these high rates of quinpirole-induced responding were dependent upon the presentation of the CS, as significantly lower levels of responding were observed when CS presentations were omitted. However, unlike with cocaine, quinpirole failed to enhance responding that was maintained by the food-paired CS, suggesting that the quinpirole-CS interaction may be reinforcer specific, as has previously been shown for the response-maintaining effects of quinpirole in direct substitution studies (Collins and Woods, 2007). Taken together with the results of the three substitution studies, these findings proved strong evidence that quinpirole is capable of producing a robust and persistent enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing value of CSs regardless of whether it is delivered contingent upon responding or not.

Although these studies were primarily focused on the interactions between quinpirole and the CSs associated with cocaine reinforcement, it is important to note that quinpirole has also been shown to maintain responding when substituted from, and delivered with CSs that have been paired with remifentanil reinforcement (Collins and Woods, 2007), and enhance responding for CSs that have been paired with water (Wolterink et al., 1993). While it is unclear why quinpirole had differential effects on responding for cocaine- and food-paired CSs in the current studies, it is likely that quinpirole is also capable of enhancing the conditioned reinforcing value of CSs paired with other classes of drug and non-drug reinforcers. Additionally, it is important to note that drug and behavioral addictions have been shown to be mediated by similar neural mechanisms (e.g., Potenza, 2008; Volkow et al., 2008), that cocaine-, gambling-, and food-associated cues have been shown to induce drug craving, gambling urges, and the desire for food in cocaine abusers, pathological gamblers and normal healthy individuals, respectively (Ehrman et al., 1992; Potenza et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2004; Crockford et al., 2005), suggesting that conditioned stimuli may play a similar role in a variety of problematic, goal-directed behaviors. When taken together with the fact that D3 and D2/D3 antagonists are capable of inhibiting cue-induced reinstatement of responding for a variety of drugs of abuse in laboratory animals (Gilbert et al., 2005; Gal and Gyertyan, 2006; Cervo et al., 2007; Heidbreder et al., 2007), the current finding that quinpirole, a D2/D3 agonist, is capable of producing a robust and persistent enhancement of conditioned reinforcing value of stimuli that were previously paired with cocaine, provides strong evidence that D2 and/or D3 receptors play an important role in the capacity of environmental stimuli to induce urges for drugs, gambling, food, or sex. Thus, the general finding that quinpirole enhanced responding for cocaine-paired CSs may provide valuable insights into the mechanism(s) responsible for the development of impulse control disorders in patients being treated with D2-like agonists, such as pramipexole or ropinirole (e.g., Voon et al., 2006; Weintraub et al., 2006; Voon and Fox, 2007; Weintraub, 2008; Wolters et al., 2008), and suggests that the compulsive nature of these problematic, goal-directed, behaviors may be driven by an enhancement of the conditioned reinforcing value of environmental stimuli that have been associated with their past performance, just as quinpirole induced a robust, and persistent enhancement the reinforcing value of the stimuli that had previously been paired with cocaine reinforcement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH grants DA020669 & F013771 through NIDA

References

- Amato D, Milella MS, Badiani A, Nencini P. Compulsive-like effects of repeated administration of quinpirole on drinking behavior in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beninger RJ, Hanson DR, Phillips AG. The acquisition of responding with conditioned reinforcement: effects of cocaine, (+)-amphetamine and pipradrol. Br J Pharmacol. 1981;74:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:230–237. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Koob GF. Modulation of cocaine self-administration in the rat through D-3 dopamine receptors. Science. 1993;260:1814–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.8099761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Patel S, Bristow L, Kulagowski J, Vallone D, Saiardi A, Borrelli E. Role of dopamine D2-like receptors in cocaine self-administration: studies with D2 receptor mutant mice and novel D2 receptor antagonists. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2977–2988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02977.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervo L, Cocco A, Petrella C, Heidbreder CA. Selective antagonism at dopamine D3 receptors attenuates cocaine-seeking behaviour in the rat. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10:167–181. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705006449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Operant responding for conditioned and unconditioned reinforcers in rats is differentially enhanced by the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Woods JH. Drug and Reinforcement History as Determinants of the Response-Maintaining Effects of Quinpirole in the Rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford DN, Goodyear B, Edwards J, Quickfall J, el-Guebaly N. Cue-induced brain activity in pathological gamblers. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:787–795. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Laane K, Pena Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Differential control over drug-seeking behavior by drug-associated conditioned reinforcers and discriminative stimuli predictive of drug availability. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:952–960. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Underwood RJ, Hagan JJ, Everitt BJ. Attenuation of cue-controlled cocaine-seeking by a selective D3 dopamine receptor antagonist SB-277011-A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:329–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA, Clements LA, Sved AF. Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:68–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver-Dunckley E, Samanta J, Stacy M. Pathological gambling associated with dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2003;61:422–423. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000076478.45005.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver-Dunckley ED, Noble BN, Hentz JG, Evidente VG, Caviness JN, Parish J, Krahn L, Adler CH. Gambling and increased sexual desire with dopaminergic medications in restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30:249–255. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e31804c780e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorkin A, Perreault ML, Szechtman H. Development and temporal organization of compulsive checking induced by repeated injections of the dopamine agonist quinpirole in an animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Childress AR, O'Brien CP. Conditioned responses to cocaine-related stimuli in cocaine abuse patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02245266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3125–3135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Second-order schedules of drug reinforcement in rats and monkeys: measurement of reinforcing efficacy and drug-seeking behaviour. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;153:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130000566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantino E, Romanowich P. The effect of conditioned reinforcement rate on choice: a review. J Exp Anal Behav. 2007;87:409–421. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.44-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal K, Gyertyan I. Dopamine D3 as well as D2 receptor ligands attenuate the cue-induced cocaine-seeking in a relapse model in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JG, Newman AH, Gardner EL, Ashby CR, Jr., Heidbreder CA, Pak AC, Peng XQ, Xi ZX. Acute administration of SB-277011A, NGB 2904, or BP 897 inhibits cocaine cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats: role of dopamine D3 receptors. Synapse. 2005;57:17–28. doi: 10.1002/syn.20152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SR, Kelleher RT, Goldberg DM. Fixed-ratio responding under second-order schedules of food presentation or cocaine injection. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;218:271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Andreoli M, Marcon C, Hutcheson DM, Gardner EL, Ashby CR., Jr. Evidence for the role of dopamine D3 receptors in oral operant alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior in mice. Addict Biol. 2007;12:35–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL, Xi ZX, Thanos PK, Mugnaini M, Hagan JJ, Ashby CR., Jr. The role of central dopamine D3 receptors in drug addiction: a review of pharmacological evidence. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:77–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman AJ. Impulse Control Disorder Behaviors Associated with Pramipexole Used to Treat Fibromyalgia. J Gambl Stud. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D, Avisar A, Doljansky J. Enhancement of excessive lever-pressing after post-training signal attenuation in rats by repeated administration of the D1 antagonist SCH 23390 or the D2 agonist quinpirole, but not the D1 agonist SKF 38393 or the D2 antagonist haloperidol. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:1291–1300. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.6.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ. Sign-tracking (autoshaping) in rats: a comparison of cocaine and food as unconditioned stimuli. Learn Behav. 2004;32:463–476. doi: 10.3758/bf03196042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruzich PJ, Congleton KM, See RE. Conditioned reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior with a discrete compound stimulus classically conditioned with intravenous cocaine. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:1086–1092. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylo DD. Effects of quinpirole on operant conditioning: perseveration of behavioral components. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylo DD, Tanguay S. Effects of quinpirole on behavioral extinction. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SM, Campbell BL, Katz JL. Interactions of cocaine with dopamine uptake inhibitors or dopamine releasers in rats discriminating cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1088–1096. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Dempsey J, Shaham Y. Cocaine seeking over extended withdrawal periods in rats: different time courses of responding induced by cocaine cues versus cocaine priming over the first 6 months. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1860-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Grant KA, Gage HD, Mach RH, Kaplan JR, Prioleau O, Nader SH, Buchheimer N, Ehrenkaufer RL, Nader MA. Social dominance in monkeys: dopamine D2 receptors and cocaine self-administration. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:169–174. doi: 10.1038/nn798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Mach RH. Self-administration of the dopamine D3 agonist 7-OH-DPAT in rhesus monkeys is modified by prior cocaine exposure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;125:13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02247388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Grundt P, Nader MA. Dopamine D3 receptor partial agonists and antagonists as potential drug abuse therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3663–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm040190e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan SS, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: an overview of its epidemiology, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:157–170. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, Matteson GL, Black JJ, Liu X, Caggiula AR, Craven L, Donny EC, Sved AF. The reinforcement enhancing effects of nicotine depend on the incentive value of non-drug reinforcers and increase with repeated drug injections. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilla M, Perachon S, Sautel F, Garrido F, Mann A, Wermuth CG, Schwartz JC, Everitt BJ, Sokoloff P. Selective inhibition of cocaine-seeking behaviour by a partial dopamine D3 receptor agonist. Nature. 1999;400:371–375. doi: 10.1038/22560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN. Review. The neurobiology of pathological gambling and drug addiction: an overview and new findings. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3181–3189. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Steinberg MA, Skudlarski P, Fulbright RK, Lacadie CM, Wilber MK, Rounsaville BJ, Gore JC, Wexler BE. Gambling urges in pathological gambling: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:828–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Relationship between reward-enhancing and stereotypical effects of psychomotor stimulant drugs. Nature. 1976;264:57–59. doi: 10.1038/264057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Partridge B. Influence of a conditioned light stimulus on cocaine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;154:390–396. doi: 10.1007/s002130000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, Podlesnik CA. Conditioned reinforcement value and resistance to change. J Exp Anal Behav. 2008;89:263–298. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2008-89-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott RS, Mach RH, Nader MA. Dopamine D2/D3 receptors modulate cocaine's reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:97–110. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Sulis W, Eilam D. Quinpirole induces compulsive checking behavior in rats: a potential animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1475–1485. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Acerbo MJ, Jones SA, Robinson TE. The attribution of incentive salience to a stimulus that signals an intravenous injection of cocaine. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Pappas N. Prediction of reinforcing responses to psychostimulants in humans by brain dopamine D2 receptor levels. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1440–1443. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Telang F. Overlapping neuronal circuits in addiction and obesity: evidence of systems pathology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3191–3200. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1089–1096. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon V, Hassan K, Zurowski M, de Souza M, Thomsen T, Fox S, Lang AE, Miyasaki J. Prevalence of repetitive and reward-seeking behaviors in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1254–1257. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238503.20816.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Telang F, Jayne M, Ma J, Rao M, Zhu W, Wong CT, Pappas NR, Geliebter A, Fowler JS. Exposure to appetitive food stimuli markedly activates the human brain. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1790–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D. Dopamine and impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S93–100. doi: 10.1002/ana.21454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub D, Siderowf AD, Potenza MN, Goveas J, Morales KH, Duda JE, Moberg PJ, Stern MB. Association of dopamine agonist use with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:969–973. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolterink G, Phillips G, Cador M, Donselaar-Wolterink I, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Relative roles of ventral striatal D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in responding with conditioned reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110:355–364. doi: 10.1007/BF02251293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters E, van der Werf YD, van den Heuvel OA. Parkinson's disease-related disorders in the impulsive-compulsive spectrum. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 5):48–56. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-5010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Goldberg LI, Ginos JZ. Intravenous self-administration of dopamine receptor agonists by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;230:678–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]