Summary

We identified subsets of neurons in the brain that co-express the dopamine receptor subtype-2 (DRD2) and the ghrelin receptor (GHSR1a). Combination of FRET confocal microscopy and Tr-FRET established the presence of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in hypothalamic neurons. To interrogate function, mice were treated with the selective DRD2 agonist cabergoline which produced anorexia in wild-type and ghrelin−/− mice; intriguingly, ghsr−/− mice were refractory illustrating dependence on GHSR1a, but not ghrelin. Elucidation of mechanism showed that formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers allosterically modifies canonical DRD2 dopamine signaling resulting in Gβγ subunit-dependent mobilization of [Ca2+]i independent of GHSR1a basal activity. By targeting the interaction between GHSR1a and DRD2 in wild-type mice with a highly selective GHSR1a antagonist (JMV2959) cabergoline–induced anorexia was blocked. Inhibiting dopamine signaling in subsets of neurons with a GHSR1a antagonist has profound therapeutic implications by providing enhanced selectivity because neurons expressing DRD2 alone would be unaffected.

Keywords: ghrelin, growth hormone secretagogue receptor, GHSR1a, dopamine, DRD2, GPCR, heteromerization, Tr-FRET, FRET, protein-protein interaction, signal transduction, G protein, hypothalamus, brain, feeding behavior, food intake

Introduction

The growth hormone secretagogue receptor GHSR1a was identified as an orphan G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) by expression cloning with a small molecule, MK-0677, that rejuvenates the GH axis in elderly subjects (Howard et al., 1996; Smith et al., 1997). In situ hybridization and RNase protection assays in rat and human brain illustrated expression in multiple hypothalamic nuclei, in the dentate gyrus and CA2 and CA3 regions of the hippocampal formation, as well as the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, and dorsal and median raphe nuclei (Guan et al., 1997). Subsequently, GHSR1a was deorphanized by the discovery of ghrelin produced in the stomach that enhances GH release and appetite (Dixit et al., 2007; Kojima et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2006; Wren et al., 2001). Upon activation, GHSR1a transduces its signal through Gαq/11, phospholipase C, inositol phosphate and mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Smith et al., 1997).

Employing Ghsr-IRES-tauGFP knock-in mice we showed that DRD1 is expressed in discrete sets of neurons in the brain that also express GHSR1a (Jiang et al., 2006), and now show subsets co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2. We speculated that receptor co-expression in same neurons can led to interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2 by modifying dopamine signaling and translate it into discrete behavioral phenotypes. Paradoxically, despite the broad distribution of GHSR1a in the brain, with the exception of extremely low levels measured in the arcuate nucleus, endogenous ghrelin is undetectable (Cowley et al., 2003; Grouselle et al., 2008). Resolution of this paradox led to the experiments described herein and we provide evidence for the role of unliganded GHSR1a (apo-GHSR1a) in neurons via heteromerization with DRD2. DRD2 is a member of GPCR A family; canonically DRD2 transmits dopamine signal through Gαi/o coupling which results in inhibiting activity of adenylate cyclase and decreasing cAMP level (Missale et al., 1998). Dopamine signaling through DRD2 has been shown to regulate food intake (Fetissov et al., 2002; Johnson and Kenny, 2010; Palmiter, 2007; Pijl, 2003; Volkow et al., 2011). Hypothalamus is a key center in homeostatic food regulation and it has been shown that hypothalamic dopamine signaling is important for basal regulation of food intake by influencing feeding frequency and volume (Meguid et al., 2000). In support of a role for DRD2 signaling in the regulation of feeding behavior, pharmacologically increasing dopamine in the lateral hypothalamus (LHA) induces anorexia and injection of a DRD2 antagonist into the LHA increases food intake (Vucetic and Reyes, 2010).

Here, we examined whether co-expression of GHSR1a and DRD2 in the same neuron leads to formation of heteromers that exhibit unique pharmacological properties, or if crosstalk between GHSR1a and DRD2 occurs independent of heterodimerization, as reported for other Gαq- and Gαi-coupled receptor pairs (Rives et al., 2009). We present evidence that in the absence of ghrelin interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2 alters canonical DRD2 signal transduction resulting in dopamine-induced [Ca2+]i mobilization. Based on results from a series of in vitro experiments, we conclude that the mechanism is not explained by receptor crosstalk, but by allosteric interaction between apo-GHSR1a and DRD2.

Illustrating the physiological relevance of our findings we show unambiguously using ghsr−/− mice, ghrelin−/− and wild-type mice that the anorexigenic property of a DRD2 agonist is dependent upon interactions with GHSR1a, but not ghrelin. Furthermore, the demonstration that a highly selective GHSR1a antagonist inhibits DRD2 agonist signaling in vitro and in vivo supports our hypothesis that apo-GHSR1a is an allosteric modulator of dopamine-DRD2 signaling. Most importantly, we also show that GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers exist naturally in native hypothalamic neurons that regulate appetite.

This discovery is of fundamental importance towards understanding neuronal signaling because of a popular belief that with the exception of GABAB receptors, where two dissimilar subunits are required for agonist-induced signal transduction in vivo (Jones et al., 1998), GPCR heteromers are in vitro artifacts and physiologically irrelevant. Our findings have important therapeutic implications because extensive resources have been invested in developing GHSR1a antagonists as antiobesity agents. Polymorphisms in DRD2 impair DRD2 signaling and are associated with obesity in humans (Epstein et al., 2007). Placing our findings in this context we would predict that GHSR1a antagonists might exacerbate rather than prevent obesity. Indeed, a recent report concluded that the lack of efficacy of GHSR1a antagonists in the clinic was a poor understanding of the complexity of GHSR1a signaling in vivo (Costantini et al., 2011).

Results

Identification of neurons co-expressing ghsr1a and drd2 in mouse brain

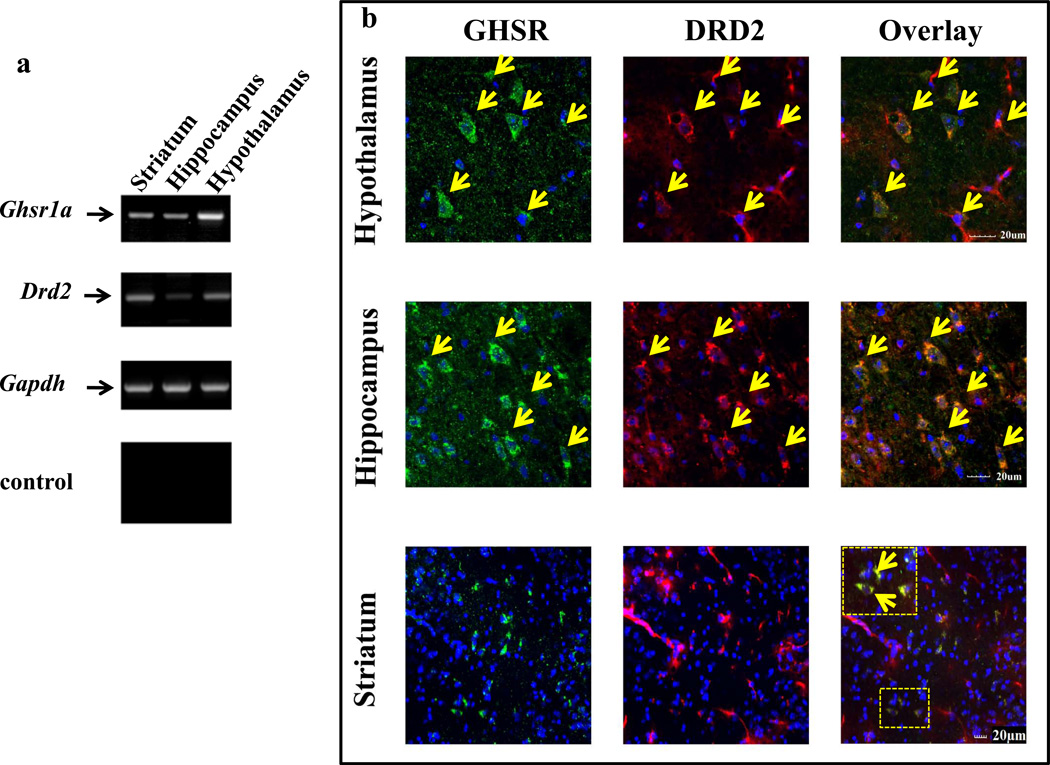

To measure the relative expression of ghsr1a and drd2 mRNA was isolated from different regions of the mouse brain. RT-PCR shows ghsr1a expression is most abundant in hypothalamus compared to striatum and hippocampus and that drd2 is expressed mainly in the striatum with lesser amounts in the hypothalamus (Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence on brain slices from Ghsr-IRES-tauGFP mice (Jiang et al., 2006) show colocalization of DRD2 and GFP in subsets of neurons with the most abundant co-expression in the hypothalamus (Figure 1B). The specificity of the DRD2 monoclonal antibody used for immunofluorescence studies was rigorously tested (Figure S1A,B,C and D). Importantly, DRD2 immunofluorescence was observed in brain slices from drd2+/+, but not drd2−/− mice.

Figure 1. GHSR1a and DRD2 mRNA and protein expression in mouse brain.

(a) GHSR1a and DRD2 mRNA expression in mouse striatum, hippocampus and hypothalamus. No PCR products are detected in controls containing no RT; the housekeeping gapdh was used as a negative control. The sizes of PCR products are: ghsr1a, 190 bp; drd2, 286 bp; and gapdh, 428 bp.

(b) Identification of neurons co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 in mouse brain. Brain sections from ghsr-IRES-tauGFP mice were stained with mouse DRD2 antibody and secondary Alexa647 (red); GHSR1a expressing neurons were localized by detecting GFP (green). To amplify GFP signal, sections were stained with GFP antibody and secondary Alexa488. Co-expression of GHSR1a and DRD2 is shown in overlay pictures with yellow arrows indicating individual neurons co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). In striatum, box represents the area with higher magnification.

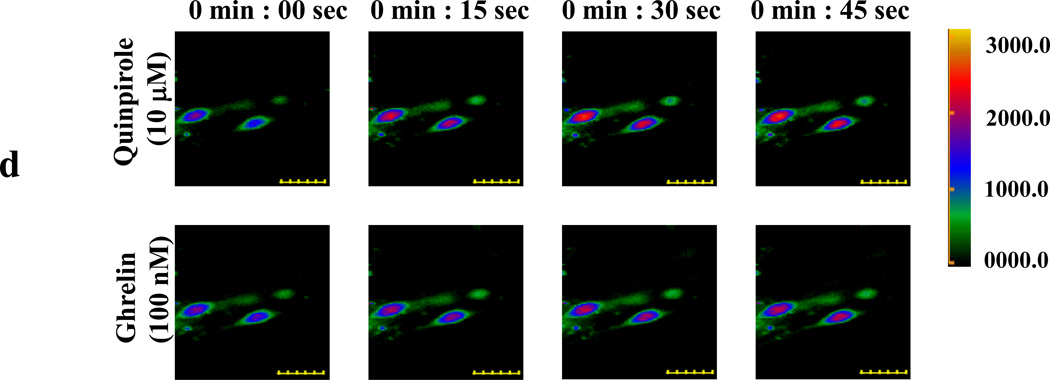

Quinpirole induces Ca2+ transients in neuronal cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2

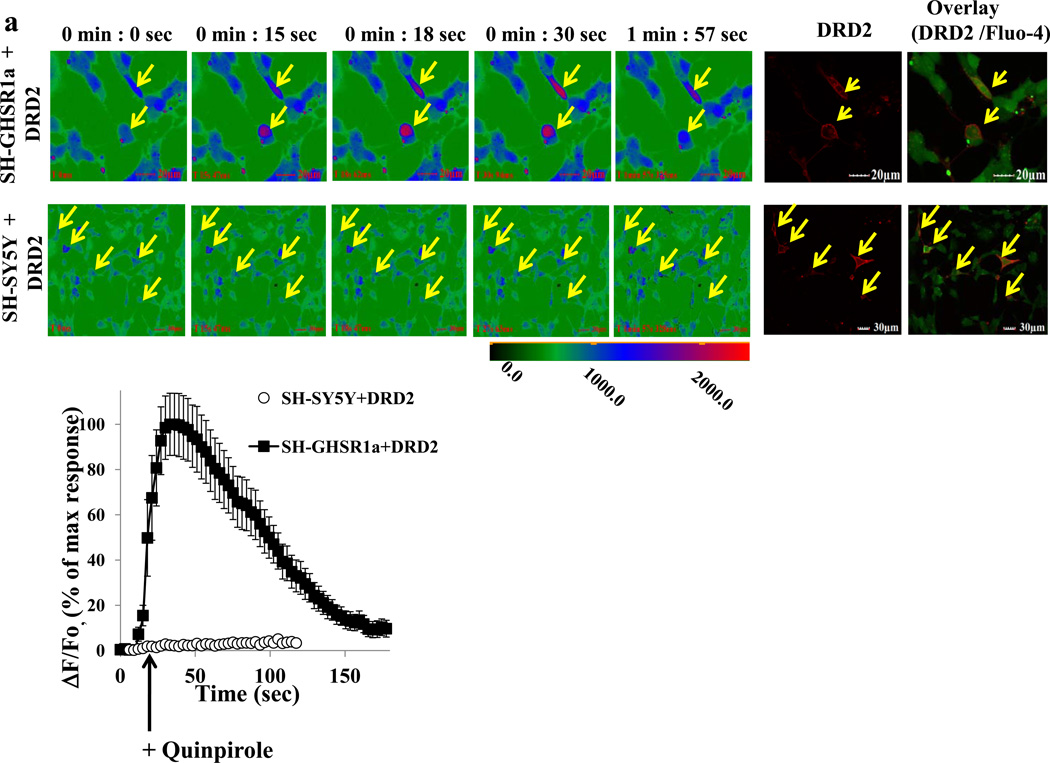

To investigate whether neuronal cells that co-express GHSR1a and DRD2 are characterized by modification of signal transduction, we selected the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line that expresses DRD2 endogenously and generated SH-SY5Y cells that stably express GHSR1a (SH-GHSR1a). In SH-SY5Y parental cells, DRD2 activation by the selective DRD2 agonist, quinpirole, causes coupling to Gαi without inducing release of intracellular Ca2+, whereas quinpirole treatment of SH-GHSR1a cells produces dose dependent rapid transient Ca2+ signals reaching a maximum by 20 sec (Figure 2A; Figure 2B EC50=32.76±3.4 nM). Attenuation of the Ca2+ signal by the DRD2 antagonist raclopride confirms DRD2 specificity (Figure 2C) and attenuation by the GHSR1a antagonist/inverse agonist L-765,867, Subst P derivative (Holst et al., 2004; Smith et al., 1996).

Figure 2. Apo-GHSR1a modifies DRD2 signaling causing quinpirole to induce mobilization of[Ca2+]i in neuronal cells.

(a) SH-GHSR1a (upper panel) or parental SH-SY5Y (lower panel) neuronal cells transfected with SNAP-DRD2 were loaded with Fluo-4. Changes in [Ca2+] (shown in pseudocolor) were imaged after quinpirole (10 µM) treatment. SNAP-DRD2 expressing cells (yellow arrows) were visualized by labeling with red-fluorophore (BG-647, 2 µM). Overlay pictures represent the DRD2 expressing cells (red) loaded with Fluo-4 (green). Graphical representation of changes in [Ca2+] over time after quinpirole treatment (lower panel). Cells co-expressing GHSR1a+DRD2 (SH-GHSR1a transfected with SNAP-DRD2) show rapid Ca2+ transients; however, cells expressing only DRD2 SH-SY5Y transfected with SNAP-DRD2) show no increase in [Ca2+].

(b) Dose-dependence of quinpirole-stimulated [Ca2+]i mobilization in SH-GHSR1a cells transfected with DRD2.

(c) Quinpirole-induced increase in [Ca2+]i mobilization is abolished by treatment with GHSR1a and DRD2 antagonists. Pretreatment of SH-GHSR1a cells transfected with DRD2 with raclopride or substance P derivative for 5 min attenuates quinpirole (10 µM)-induced Ca2+ signals. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments with responses from 5–10 cells analyzed for each experiment. **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001 versus untreated control.

(d) Primary neurons isolated from hypothalamus were loaded with Fluo-4. [Ca2+]i level changes (shown in pseudocolor) were imaged after quinpirole addition (10 µM, upper panels). After washing, the same cells respond to ghrelin (100 nM) treatment by increasing [Ca2+]i level (lower panels). Scale bar represents 20 µm.

Since GHSR1a and DRD2 co-localize in the hypothalamus (Figure 1B), we prepared primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons. Treatment of the cultured neurons induces rapid Ca2+ transients (Figure 2D, upper panel). After washing to remove quinporole, ghrelin treatment produces an immediate Ca2+ response (Figure 2D, lower panel). These results are consistent with co-expression of GHSR1a and DRD2 in hypothalamic neurons.

Specificity of functional interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2

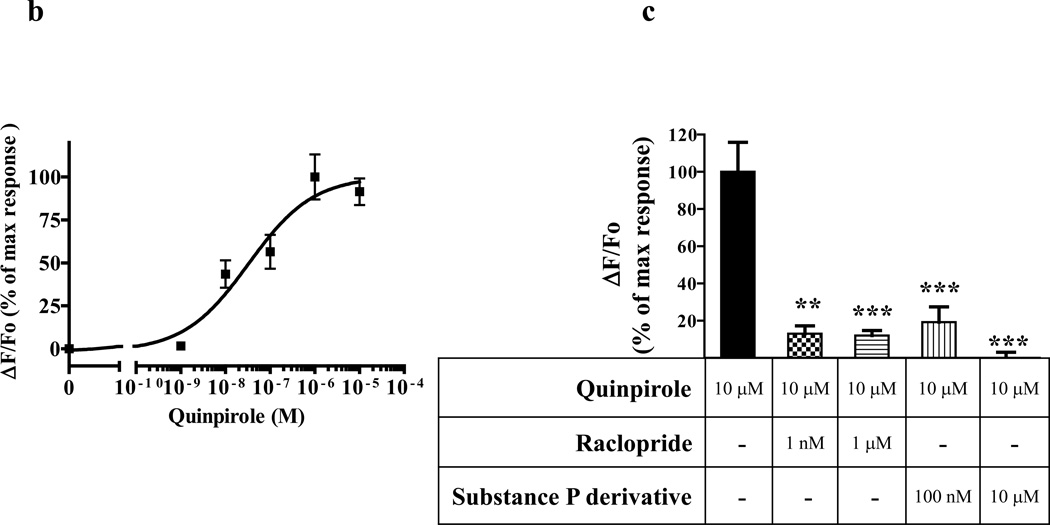

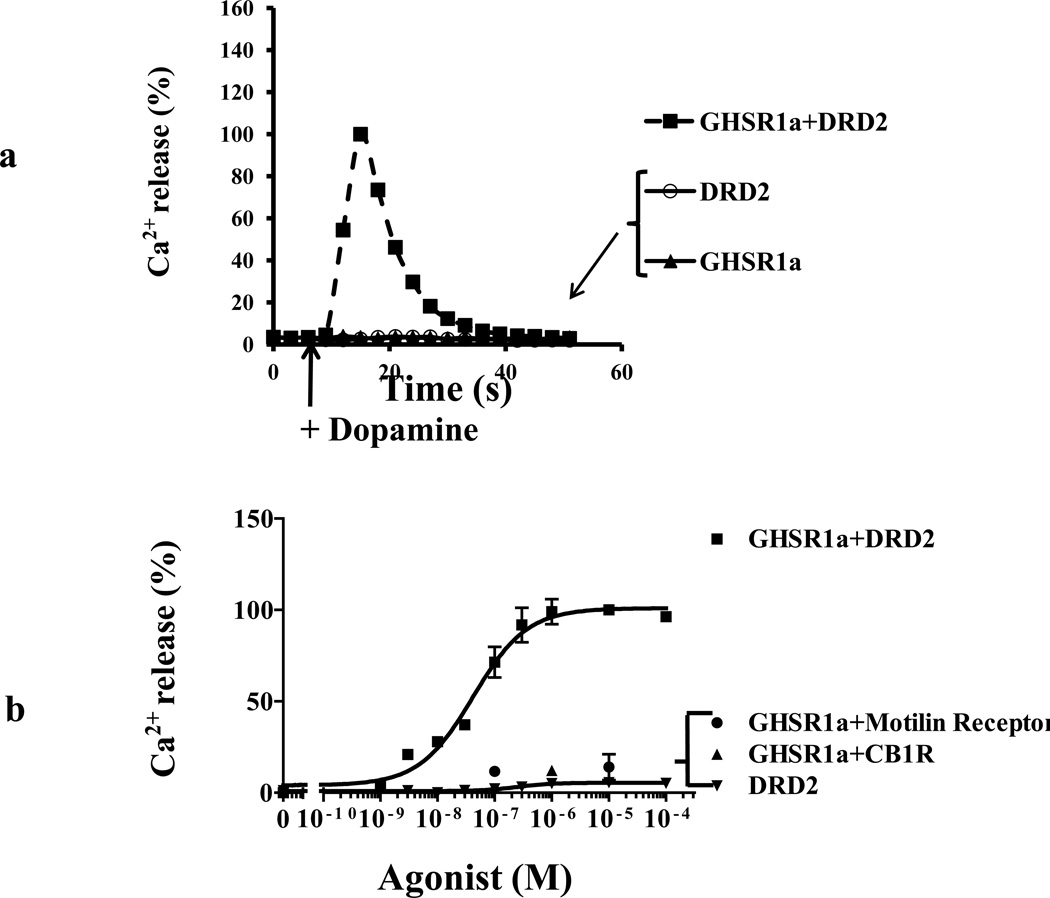

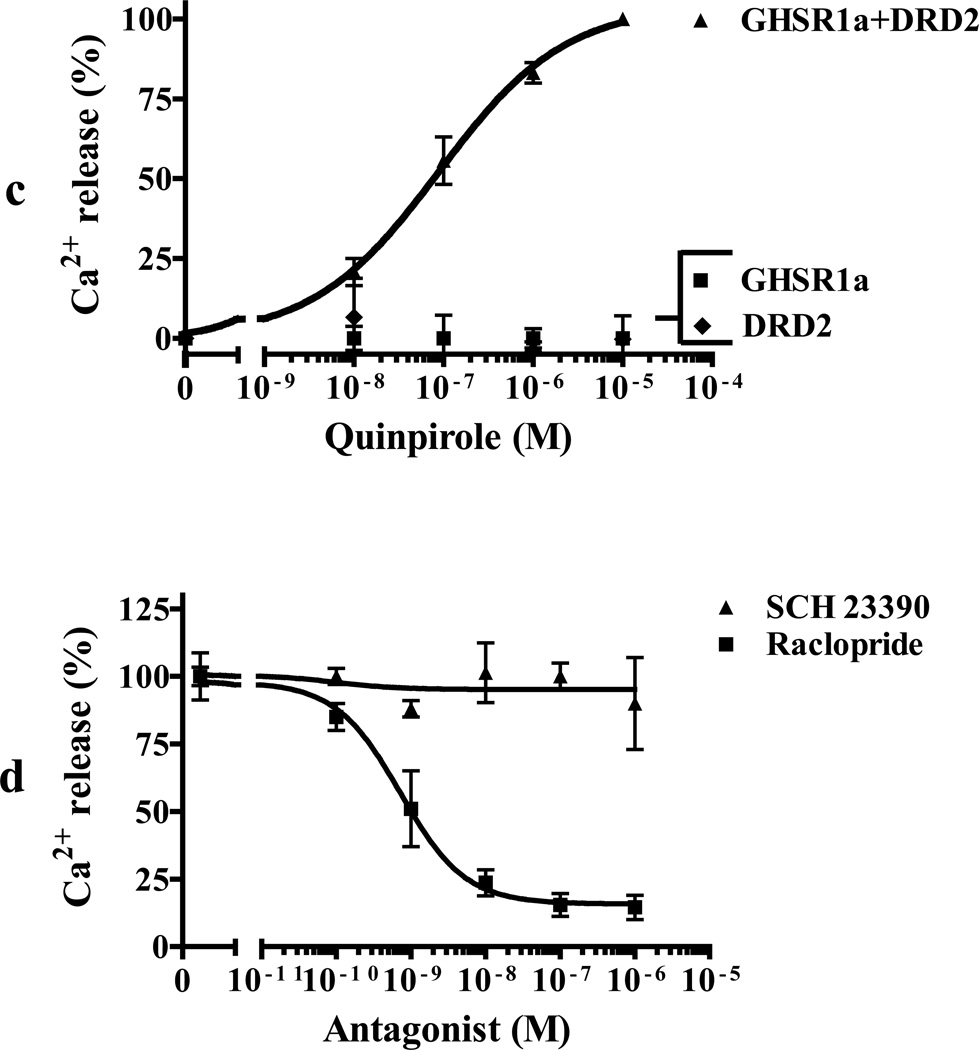

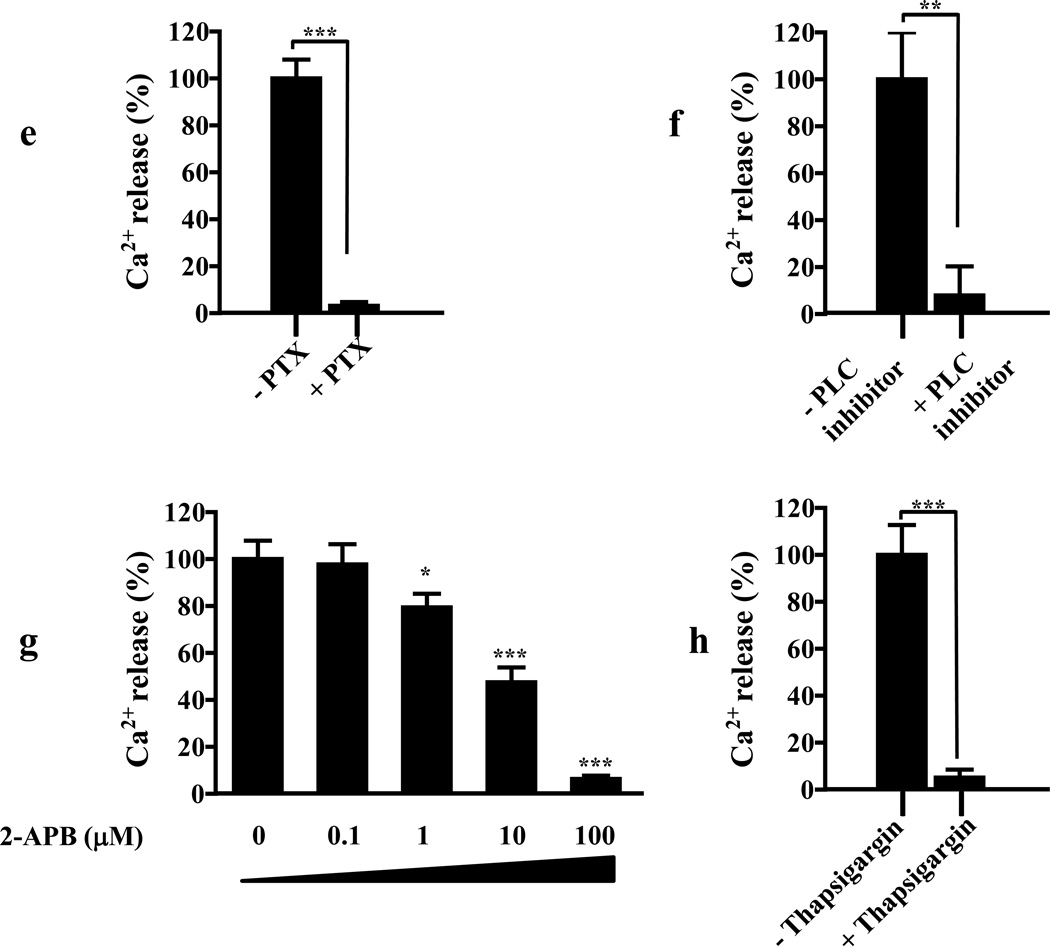

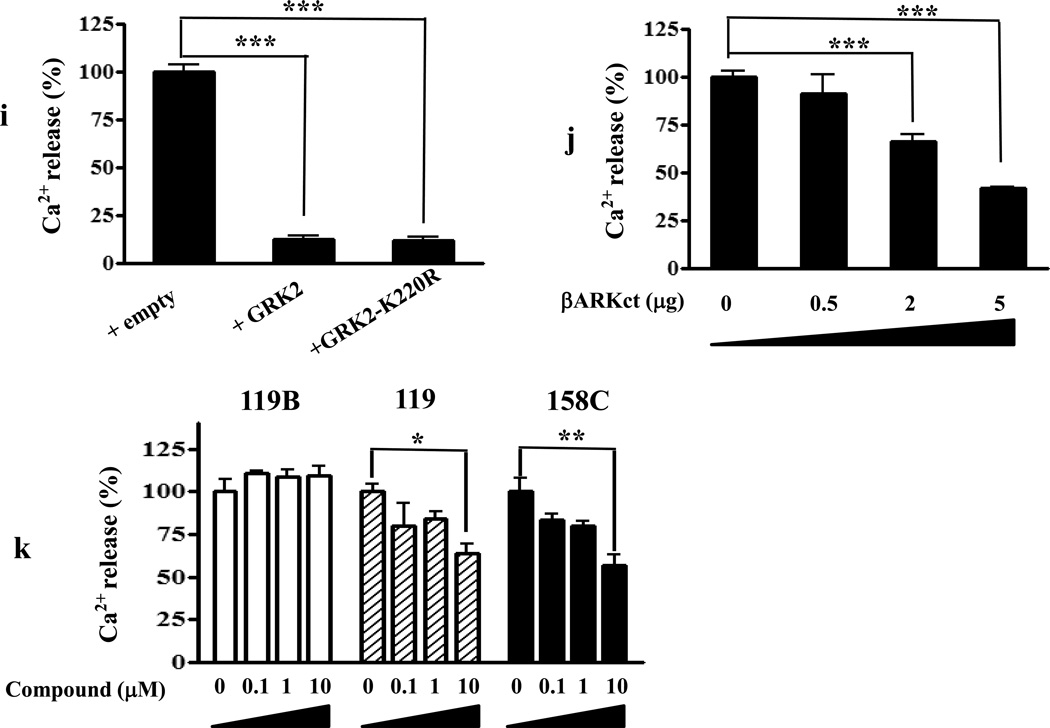

To study GHSR1a and DRD2 interactions in a system where we could control the relative concentrations of GHSR1a and DRD2 we performed Ca2+ mobilization assays in HEK293 cells stably expressing the bioluminescent calcium sensor aequorin (Button and Brownstein, 1993). When DRD2 is expressed alone dopamine does not induce Ca2+ mobilization, but when GHSR1a is co-expressed dopamine induces dose-dependent rapid Ca2+ transients with a maximal response at 15–20 sec (Figure 3A; Figure 3B, EC50=41.88±1.12 nM). To determine GHSR1a specificity, the closely related motilin receptor that also couples to Gαq/11 (Feighner et al., 1999) was co-expressed with DRD2; in this context dopamine treatment does not induce a Ca2+ response (Figure 3B). As an additional specificity control GHSR1a was co-expressed with the Gαi/o coupled cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) instead of DRD2; treatment with a CB1 agonist did not induce Ca2+ mobilization (Figure 3B). We next tested for dopamine receptor agonist specificity. The DRD2 selective agonist quinpirole dose-dependently increases [Ca2+]i in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2, but not in cells expressing either GHSR1a or DRD2 alone (Figure 3C). To determine DRD2 agonist specificity, cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 were treated with DRD2 selective antagonist raclopride or the DRD1 antagonist SCH23390. The former inhibited dopamine-induced Ca2+ signaling, but the latter was ineffective (Figure 3D), illustrating DRD2 selectivity.

Figure 3. Functional interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2 and involvement of Gβγ subunits in dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization in aequorin-HEK293 cells.

(a) Activation of transfected aequorin-HEK293 cells with dopamine (10 µM) produces rapid Ca2+ transients in cells co-expressing GHSR1a+DRD2 (■) but not in cells expressing GHSR1a (▲) or DRD2 (○) alone.

(b) Dose-dependent Ca2+ response to dopamine treatment in cells co-expressing GHSR1a+DRD2 (■). Dose-dependent Ca2+ responses to dopamine are not observed in cells co-expressing motilin receptor + DRD2 (●), DRD2 alone (▼) or in the presence of CB1R agonist (WIN-55212-2) in cells co-expressing GHSR1a+CB1R (▲).

(c) Specificity of agonist-induced Ca2+ response. Quinpirole dose-dependently increases [Ca2+] in cells co-expressing GHSR1a+ DRD2 (▲) but not in cells expressing GHSR1a (■) or DRD2 (♦) alone.

(d) In cells co-expressing GHSR1a+DRD2, dopamine-induced Ca2+ signaling is inhibited by raclopride (■) but not by the D1R specific agonist SCH 23390 (▲).

(e) Pretreatment of cells with pertussis toxin (PTX, 0.25 µg/ml) inhibits dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ release in cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2.

(f) Pretreatment with the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor (U73122, 10 µM) blocks dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ release in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2.

(g) In cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 the dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ signal is attenuated after pretreatment with the intracellular IP3 receptor antagonist 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB).

(h) Thapsigargin pretreatment (100 nM) blocks dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ release in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2.

(i) Overexpression of GRK2 or the GRK2 phosphorylation mutant (GRK2-K220R)in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 inhibit dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ mobilization.

(j) The Gβγ scavenger (βARK1ct) dose-dependently decreases dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ mobilization in cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2.

(k) Cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2 pretreated with small molecule inhibitors of Gβγ subunit signaling (M119 and M158C) and inactive control compound (M119B) for 5 min before dopamine treatment. M119B is ineffective in inhibiting dopamine-induced Ca2+ release whereas M119 and 158C inhibit the response to dopamine.

The data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments in duplicate for each concentration point. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 and ***, P<0.001 versus untreated control.

GHSR1a modification of DRD2 signal transduction via activation of Gβγ subunits

To probe the mechanism of dopamine-induced Ca2+ signal generation we tested specific inhibitors of GPCR signal transduction. The dopamine-induced Ca2+ signal is blocked by: pertussis toxin (PTX), an inhibitor of Gαi signaling (Figure 3E); the PLC inhibitor (U73122) (Figure 3F); 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) an antagonist of intracellular IP3 receptors (Figure 3G); thapsigargin (TG), a depletor of intracellular calcium stores (Figure 3H). Hence, GHSR1a and DRD2 co-expression results in dopamine-induced coupling to Gαi, activation of PLC and production of IP3 that acts on IP3 receptors to release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum.

Since dopamine-induced Ca2+ release is blocked by PTX (Figure 3E), we reasoned the mechanism might involve direct stimulation of PLC by Gβγ subunits derived from Gαi/o and direct association of Gβγ with GRK2 (Inglese et al., 1994; Koch et al., 1994). To test for a role of GRK2, we expressed wild-type GRK2 or a mutant GRK2 (GRK2-K220R) lacking kinase activity in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 (Namkung and Sibley, 2004). Both WT and mutant GRK2 inhibit dopamine-induced increases in Ca2+ (Figure 3I, P< 0.001). Expression of the Gβγ scavenger, βARK1ct (Koch et al., 1994) dose-dependently inhibits dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Figure 3J). Pretreating cells expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 with small molecule inhibitors (M119 and M158C) of Gβγ subunit signaling (Bonacci et al., 2006) attenuates dopamine-induced modification of Ca2+ release, whereas the inactive control compound (M119B) is ineffective (Figure 3K). Hence, GHSR1a modification of dopamine-induced signal transduction is mediated by Gβγ subunits.

Dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization is independent of GHSR1a basal activity

When GHSR1a is expressed at high concentrations under heterologous non-native conditions it exhibits basal activity. Therefore, in all experiments we expressed GHSR1a at concentrations commensurate with the low levels exhibited in vivo and under these conditions GHSR1a does not exhibit detectable basal activity; nevertheless, it was important to rigorously test the possibility that basal activity of GHSR1a might be responsible for altering canonical DRD2 signaling by receptor crosstalk.

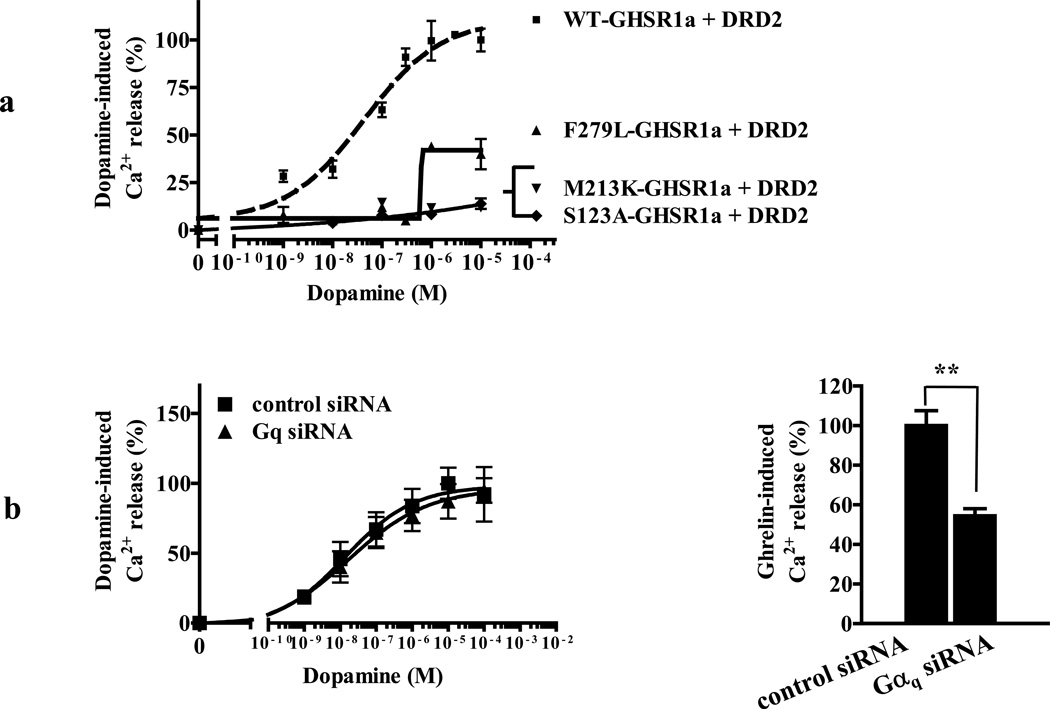

We co-expressed DRD2 with WT-GHSR1a and with three point mutants that exhibit equivalent basal activity to WT-GHSR1a (S123A-GHSR1a and M213K-GHSR1a), or lack basal activity (F279L-GHSR1a) altogether (Feighner et al., 1998; Holst et al., 2007), but may not have the ability to support DRD2 signaling. Although WT-GHSR1a and S123A-GHSR1a and M213K-GHSR1a all have identical basal activity, of the three, only WT-GHSR1a co-expression with DRD2 mobilizes Ca2+ in response to dopamine (Figure 4A). By direct contrast, co-expression of DRD2 with the basally inactive mutant produces a modest increase in Ca2+ mobilization in response to dopamine (Figure 4A). These results illustrate a lack of correlation between dopamine-induced release of intracellular Ca2+ and GHSR1a basal activity and are consistent with allosteric interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2.

Figure 4. Dopamine-induced Ca2+ release is independent of GHSR1a constitutive activity in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2.

(a) Co-expression of GHSR1a point mutants S123A and M213K that exhibit identical constitutive activity to WT-GHSR1a, and F297L which is devoid of constitutive activity Cells co-expressing DRD2 with either S123A or M213K fail to mobilize Ca2+ in response to dopamine, whereas the GHSR1a F279L point mutant exhibits Ca2+ mobilization in response to dopamine;

(b) Knockdown of Gαq subunit by siRNA does not inhibit dopamine induced Ca2+ mobilization in (left panel), whereas ghrelin-induced Ca2+ mobilization (right panel) is significantly impaired.

The data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments in duplicate for each concentration point. **, P<0.01 versus untreated control.

Agonist activation of GHSR1a in HEK293 cells results in coupling to Gαq and signaling through (Smith et al., 1997). Therefore, if modification of DRD2 signaling by GHSR1a is caused by GHSR1a basal activity, ablating Gαq expression should block DRD2-mediated mobilization of Ca2+ by dopamine. When Gαq siRNA is expressed with GHSR1a and DRD2 dopamine-induced Ca2+ signaling is not suppressed (Figure 4B, left panel), whereas ghrelin-induced Ca2+ release is significantly reduced (Figure 4B, right panel). To ensure that ablating Gαq suppresses GHSR1a basal activity, we deliberately overexpressed GHSR1a to produce detectable basal activity as measured by IP1 production. Co-expression of Gαq siRNA, but not control siRNA, suppresses IP1 production to control levels (Figure S2A). Also, overexpression of Gαq protein does not increase dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Figure S2B). The PKC inhibitor, BisI, also does not reduce dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Figure S2C). These data provide evidence that modification of DRD2 signaling by GHSR1a is independent of GHSR1a basal signaling through Gαq and PKC.

Functional crosstalk between receptors that depends on basal activity of a Gαq coupled receptor is indicated when acute pre-activation (3 min) with an agonist of the basally active receptor synergistically increases the agonist response of the protomer partner (Rives et al., 2009). In the case of GHSR1a and DRD2, pre-incubation with ghrelin for 3 min has no effect on the amount of Ca2+ released in response to dopamine (Figure S2D). Likewise, if dopamine-induced Ca2+ production is explained by potentiation of GHSR1a activity by DRD2, activation of DRD2 prior to ghrelin treatment would potentiate ghrelin-induced Ca2+ mobilization. However, this is not the case; simultaneous addition of ghrelin and dopamine results in additive Ca2+ accumulation (Figure S2E,F).

Our collective results argue that dopamine-induced Ca2+ release is independent of GHSR1a basal activity and crosstalk between signal transduction pathways. An alternative mechanism is that GHSR1a-induced modification of canonical dopamine-DRD2 signal transduction is a consequence of allosteric modification of DRD2 signal transduction caused by formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers.

Cross-desensitization of GHSR1a and dopamine receptors

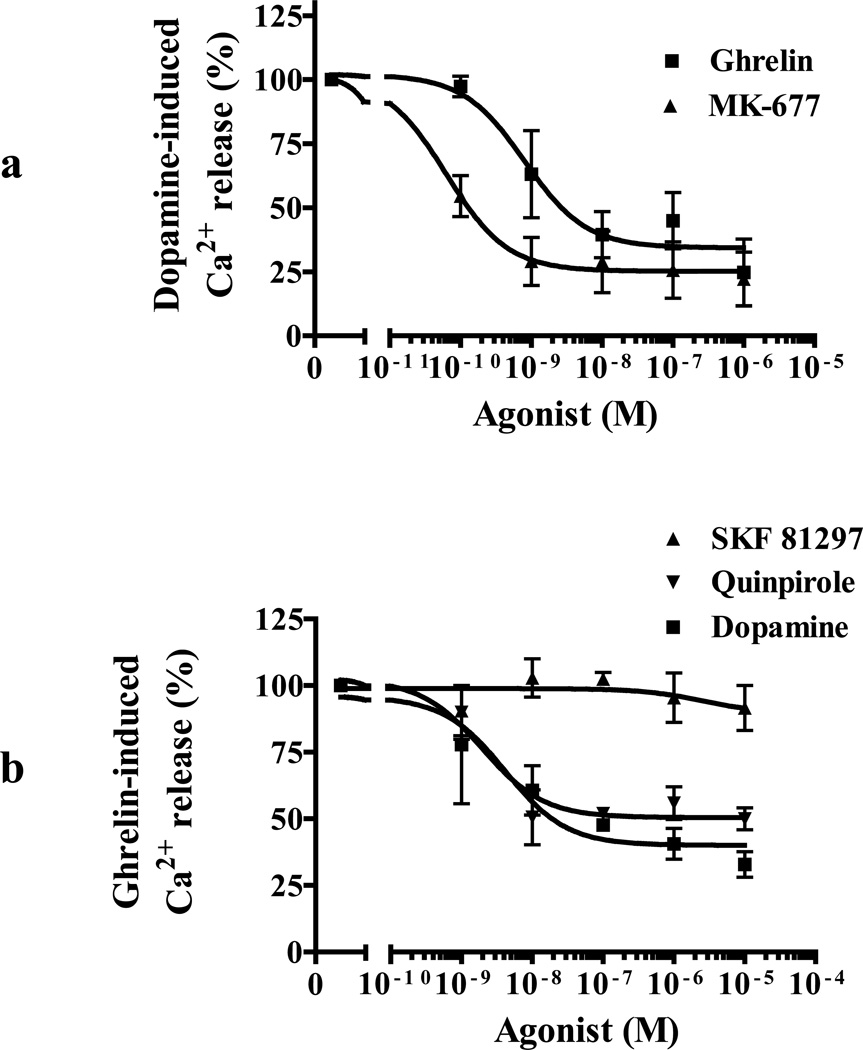

Cross-desensitization caused by extended (30 min) preincubation of receptors with the agonist of one protomer would be indirect evidence for possible formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers. Pretreatment of cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 for 30 min with increasing concentrations of the GHSR1a agonists MK-677 (Patchett et al., 1995) or ghrelin reduces dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization by 60–75% of the control response (Figure 5A). MK-677 with a longer half-life than ghrelin is significantly more efficient than ghrelin in attenuating DRD2-induced Ca2+ signaling (MK-677 EC50=0.064±0.0005 nM, ghrelin EC50=0.87±0.019nM; p<0.05; Fig. 5a). Similarly, preincubation with dopamine or quinpirole reduces ghrelin-induced Ca2+ release by 60% and 50%, respectively (Figure 5B), but preincubation with the D1R-selective agonist SKF81297 fails to inhibit the ghrelin-induced response (Figure 5B). Cross desensitization observed with a GHSR1a agonist or DRD2 agonist is consistent with a mechanism involving formation of GHSR1a:DRD2.

Figure 5. Preatment of cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 with GHSR1a or DRD2 agonists results in cross-desensitization of agonist signaling.

(a) Aequorin-HEK293 cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2 pretreated with increasing concentrations of ghrelin (■) or MK-677 (▲) for 30 min show attenuated response to dopamine-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ mobilization.

(b) Aequorin-HEK293 cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2 were pretreated with increasing concentrations of dopamine (■), SKF81297 (▲) or quinpirole (▼) for 30 min and Ca2+ mobilization measured after ghrelin treatment (100 nM).

The data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments in duplicate for each concentration point.

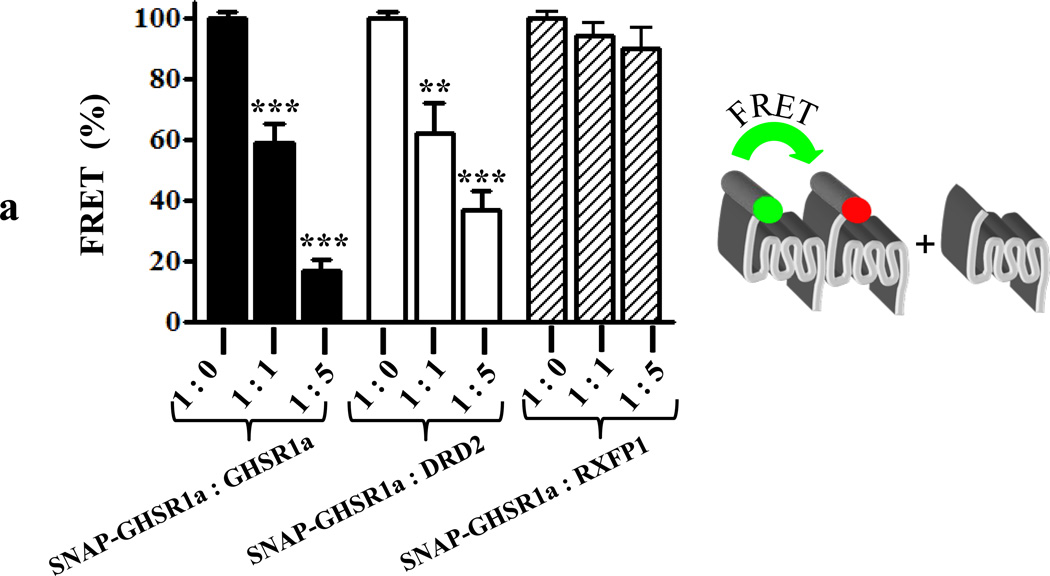

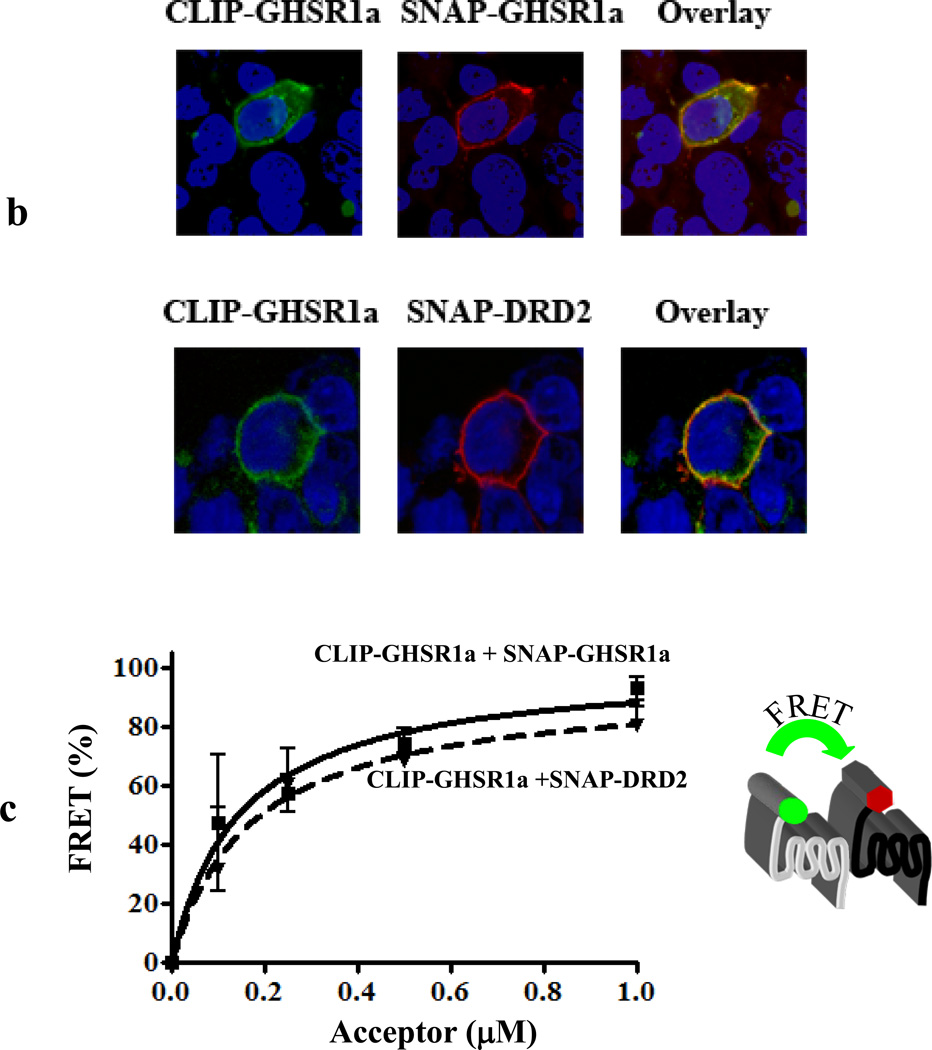

Heteromer formation between GHSR1a and DRD2

We employed time-resolved (Tr)-FRET to test for heteromer formation because this technology is ideal for monitoring cell surface protein-protein interactions at physiological concentrations of receptors (Maurel et al., 2008). We introduced a SNAP-tag at the GHSR1a N-terminus and showed its appropriate expression on the cell surface and its functional activity (Figure S3A, B). Specific labeling of SNAP-GHSR1a was demonstrated by SDS-PAGE in-gel fluorescence, fluorescent confocal microscopy, and dose-dependent cell surface labeling with BG-488 (Figure S3C, D, E).

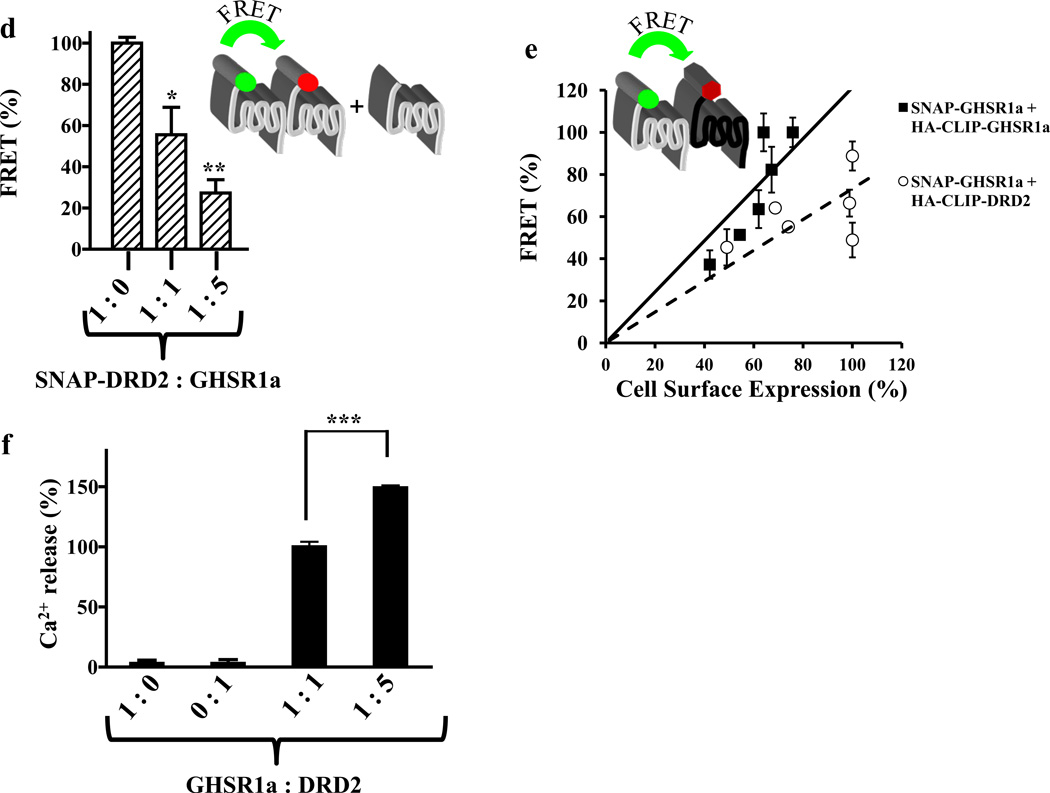

To optimize the Tr-FRET signal cells expressing SNAP-GHSR1a were incubated with a fixed concentration of energy donor (terbium cryptate, 100 nM) and increasing concentrations of acceptor (Figure S3F) and a linear relationship between receptor concentration and Tr-FRET signal was established (Figure S3G). When GHSR1a is expressed alone it forms homomers and consistent with formation of GHSR1a homomers the Tr-FRET signal is reduced according to the ratio SNAP-GHSR1a to GHSR1a such that at a ratio of 1:1 Tr-FRET is reduced to 59±6% and to 17±3.7% at a 1:5 ratio (Figure 6A). When DRD2 is substituted for GHSR1a, the Tr-FRET signal generated by GHSR1a:GHSR1a homomers is reduced to 62±10% by a 1:1 ratio of GHSR1a to DRD2 (p<0.01), and 36.6±6.5% by a 1:5 ratio, consistent with formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers (Figure 6A). When a control GPCR, RXFP1, is co-expressed with SNAP-GHSR1a, the Tr-FRET is not attenuated (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Detection of heteromer formation between GHSR1a and DRD2 in vitro by Tr-FRET.

(a) Tr-FRET competition assays where cells were transfected with increasing ratios of SNAP-GHSR1a and untagged GHSR1a, untagged DRD2 or an untagged RXFP1. (b) Cells co-transfected with CLIP- or SNAP-tagged receptor variants, labeled specifically with either green (BC-488, 2 µM) or red fluorophore (BG-647, 2 µM) and then examined by confocal microscopy. Overlay pictures show co-localization of GHSR1a with DRD2.

(c) FRET acceptor saturation assays performed using constant amount of donor fluorophore (BG-TbK, 100 nM) and increasing amounts of acceptor fluorophore (BC-647) in cells co-expressing SNAP- and CLIP-tagged receptor variants.

(d) GHSR1a:DRD2 formation measured by Tr-FRET competition assays; Tr-FRET measurements on cells transfected with SNAP-DRD2 in the presence of different ratios of untagged GHSR1a.

(e) Homomerization of GHSR1a and heteromerization of GHSR1a and DRD2 by Tr-FRET receptor titration. Cells were co-transfected with constant amount of SNAP-GHSR1a and increasing amounts of HA-CLIP-GHSR1a or HA-CLIP-DRD2. The HA-tagged receptor cell surface expression was determined by cell surface ELISA and Tr-FRET signal plotted as a function of cell surface expressed HA-CLIP-tagged receptor.

(f) Magnitude of dopamine-induced Ca2+ release is dependent on formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers; intracellular Ca2+ mobilization induced by dopamine (10 µM) in aequorin HEK293 cells expressing different ratios of GHSR1a to DRD2.

The data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments in duplicate for each concentration point. ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001 versus control.

To confirm GHSR1a:DRD2 formation we prepared CLIP-tagged GHSR1a and SNAP-tagged DRD2 and examined expression of these receptors by confocal microscopy. Both the CLIP- and SNAP-tagged receptors are co-localized on the cell surface (Figure 6B). We then conducted saturation assays observing robust saturable Tr-FRET signals indicative of specific heteromerization rather than random collisions (Figure 6C).

As a further test of heteromerization of GHSR1a and DRD2 we utilized a SNAP-tagged DRD2 variant. We first defined conditions for the equivalent labeling of SNAP-DRD2 with either fluorophore to detect homomers and tested for a linear relationship between receptor DNA transfected and Tr-FRET signal (Figure S4A,B). In Tr-FRET competition assays with SNAP-DRD2, the Tr-FRET signal in the presence of GHSR1a at a 1:1 ratio is significantly reduced compared to empty vector (55.5±13%, p<0.05), and at a 1:5 ratio further reduced (27.3 ±6.5%, p<0.01), consistent with heteromerization between GHSR1a and DRD2 (Figure 6D). Over a range of receptor concentrations high FRET signals are detected in cells expressing SNAP-GHSR1a and CLIP-DRD2, and in cells expressing SNAP-GHSR1a and CLIP-GHSR1a, which is again consistent with GHSR1a and DRD2 heteromerization (Figure 6E).

The results of Tr-FRET were compared to the magnitude of dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization. In cells co-expressing different ratios of GHSR1a to DRD2 dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization is highest in cells transfected with a 1:5 ratio of GHSR1a to DRD2 (150±1.5%), compared to cells transfected with a 1:1 ratio (Fig. 6f, p<0.001). Thus, the magnitude of dopamine-induced Ca2+ release correlates with the level of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers (Figure 6E).

Heteromerization and conformation-dependent functional interaction between GHSR1a and DRD2

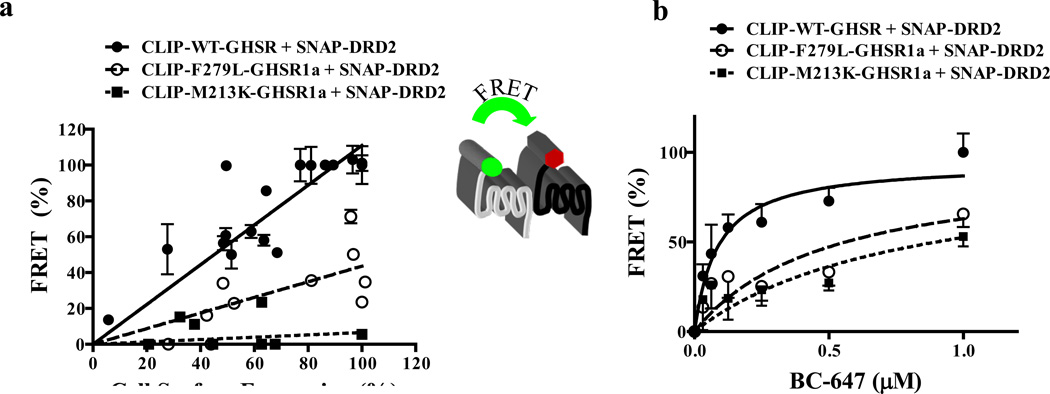

If modification of DRD2 signaling is a consequence of physical association between the two receptors, it should be dependent upon GHSR1a conformation. To test for dependence on confirmation WT-GHSR1a, M213K-GHSR1a and F279L-GHSR1a that are equivalently expressed on the cell surface of HEK293 cells were employed (Figure S5A). Tr-FRET signals were measured in cells co-expressing varying levels of CLIP-WT-GHSR1a, CLIP-M213K-GHSR1a and CLIP-F279L-GHSR1a with a fixed concentration of SNAP-DRD2. The slope of the relationship between cell surface expression and FRET signal is significantly reduced (p<0.05) with the M213K mutant (slope = 0.06±0.048) and F279L mutant (slope = 0.43±0.06) compared to WT-GHSR1a (slope = 1.11±0.05) suggesting that M213K and F279L less readily form heteromers with DRD2 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. GHSR1a point mutants illustrate GHSR1a:DRD2 formation is dependent on GHSR1a structure.

Tr-FRET experiments comparing heteromerization of wild-type GHSR1a, M213K-GHSR1a and F279L-GHSR1a point mutants in the presence of DRD2.

(a) Tr-FRET receptor titration assays were performed to assess heteromerization. Cells were co-transfected with increasing amounts of HA-CLIP-tagged receptors; the FRET signal is represented as a function of cell surface expression of HA-tagged receptors.

(b) Tr-FRET acceptor titration assay to determine heteromer formation. FRET intensity signals were measured in cells co-expressing CLIP-tagged WT-GHSR1a, M213K or F279L point mutants in the presence of SNAP-DRD2 and labeled with constant amount of donor (BG-TbK, 100 nM) and increasing amount of acceptor fluorophore (BC-647).

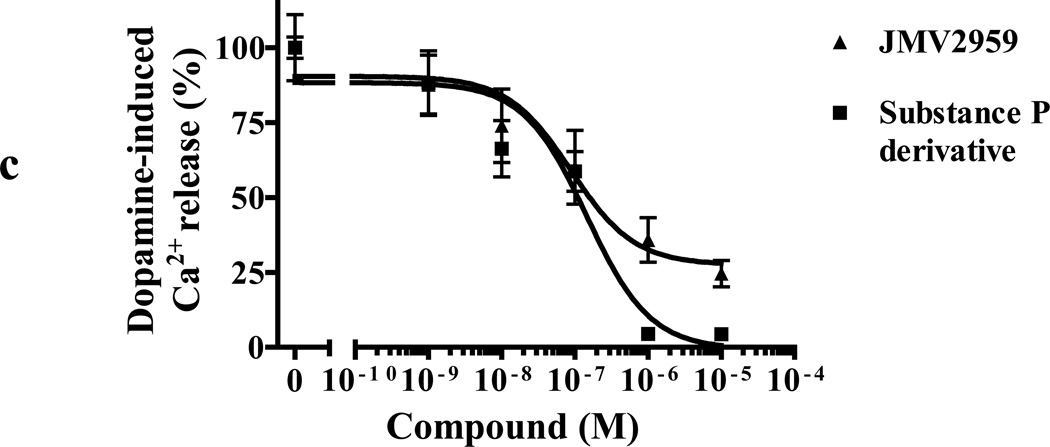

(c) Dose-dependent inhibition of dopamine-induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i in cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2 by GHSR1a neutral antagonists JMV2959 and substance P derivative

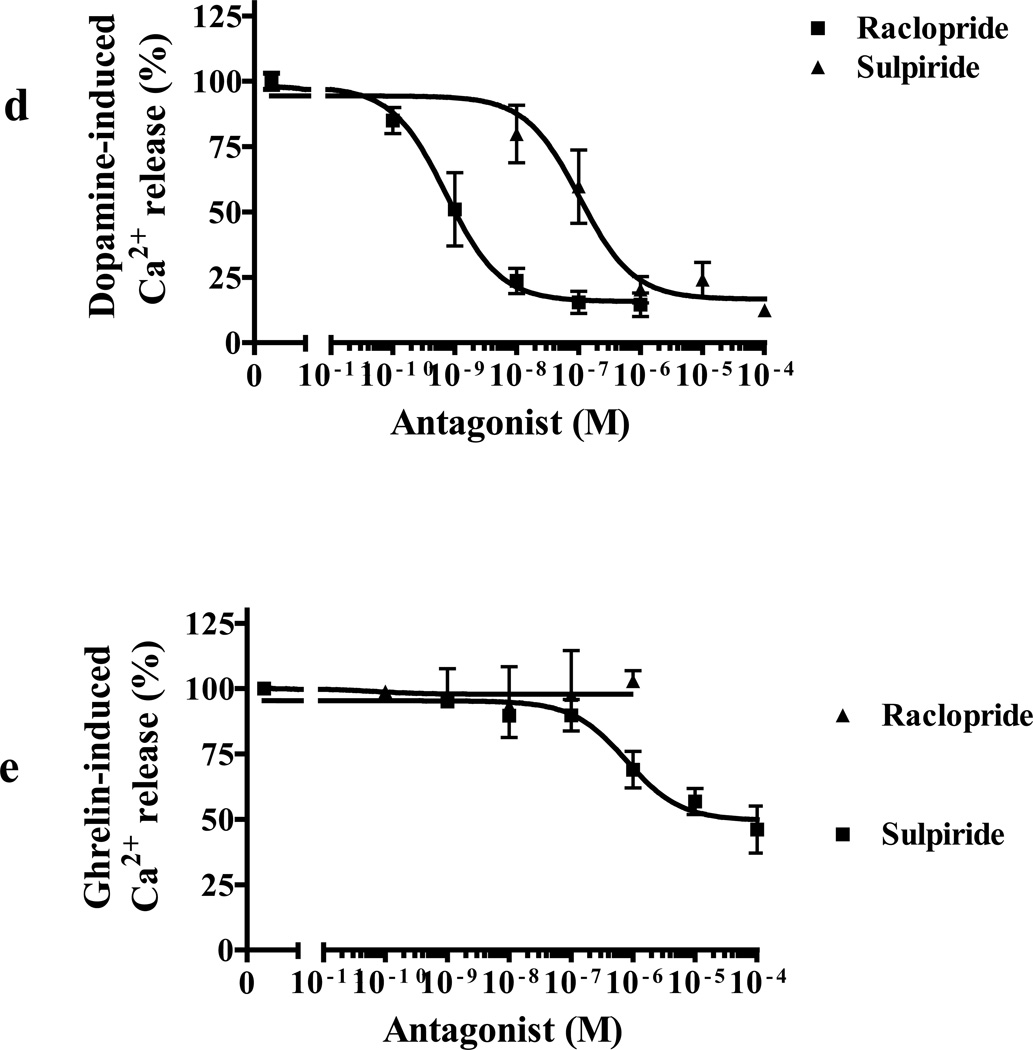

(d) Dose-dependent inhibition of dopamine-induced (10 µM) Ca2+ mobilization by DRD2 antagonist (raclopride, ■) and inverse agonist (sulpiride, ▲) in cells co-expressing GHSR1a + DRD2.

(e) Sulpiride (■) but not raclopride (▲) inhibits ghrelin-induced (100 nM) Ca2+ mobilization in cells co-expressing GHSR1a+DRD2.

The data represent the mean ± s.e.m. for three independent experiments in duplicate for each concentration point.

To determine if the reduced FRET signals in the case of the point mutants might be explained by reduced efficiency we performed Tr-FRET acceptor titration assays in cells co-expressing fixed amounts of SNAP-WT-GHSR1a and CLIP-DRD2, SNAP-M213K-GHSR1a and CLIP-DRD2 or SNAP-F279L-GHSR1a and CLIP-DRD2. A significant decrease (p<0.05) in FRET potency occurs in cells co-expressing M213K-GHSR1a with DRD2 (FRET50 = 0.79±0.22) and F279L-GHSR1a with DRD2 (FRET50 = 0.49±0.15), compared to WT-GHSR1a and DRD2 (FRET50 = 0.086±0.029). These results are consistent with a reduced capacity of the M213K and F279L point mutants to form heteromers with DRD2 (Figure 7B), suggesting that a specific GHSR1a conformation is preferred for formation of heteromers with DRD2. Since the M213K and F279L mutants exhibit reduced capacity for dopamine-induced Ca2+ release (Figure 4A), these results illustrate a positive correlation between GHSR1a conformation and dopamine induced Ca2+ signaling.

A more subtle way to alter confirmation and test for a mechanism involving allosteric effects caused by heteromerization is to use inverse agonists and antagonist selective for each protomer. We tested the effects of the GHSR1a antagonist/inverse agonist (L-765,867 aka Subst. P derivative) and the highly selective neutral antagonist JMV2959 on dopamine-induced Ca2+ signaling. Both compounds exhibit dose-dependent inhibition of dopamine-induced Ca2+ signaling (Figure 7C). As predicted, dopamine-induced Ca2+ release is dose-dependently inhibited by the DRD2 antagonist raclopride and the inverse agonist sulpiride (Figure 7D); however, sulpiride although not raclopride, partially inhibited ghrelin-induced Ca2+ mobilization. Therefore, in this context the DRD2 inverse agonist acts as a partial GHSR1a antagonist (IC50 = 0.7±0.02 µM, Figure 7E). These compounds do not interfere with GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromerization (data not shown) and these data are consistent with altered conformation of protomers by their respective inverse agonist or neutral antagonist as reflected by modification of signaling of the protomer partner; furthermore, the results support a model where allosteric modification of DRD2 signaling by GHSR1a is dependent upon formation of heteromers.

Detection of GHSR1a and DRD2 heteromers in native tissues

We next directly addressed the question of whether GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers exist in the brain by using fluorescently labeled ghrelin (red-ghrelin) to localize GHSR1a expression. First our approach employing red-ghrelin was validated. In HEK293 cells expressing SNAP-GHSR1a a robust FRET signal was generated following binding of red ghrelin (Kd=28 nM; Figure S6A). Illustrating red ghrelin specificity, unlabeled ghrelin and the highly selective GHSR1a agonist, MK-677 (Patchett et al., 1995) competitively inhibit red ghrelin binding (IC50=215±30nM and 35±20 nM, respectively), but des-acyl ghrelin was ineffective (Figure S6B). In brain slices from ghsr +/+ mouse, but not in slices from ghsr −/− mouse, red ghrelin is observed confirming the specificity of fluorescent red-ghrelin binding to GHSR1a (Figure S6C).

Red ghrelin was next used to test for formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in vitro. SNAP-tagged receptors labeled with cryptate fluorophore donor produces dose-dependent increases in FRET in cells co-expressing SNAP-GHSR1a and GHSR1a or SNAP-DRD2 and GHSR1a in the presence of red-ghrelin (Figure S6D.). When different ratios of GHSR1a and SNAP-DRD2 (1:1 and 1:2) are expressed the FRET signals associated with red-ghrelin correlate with the relative ratios of GHSR1a to DRD2 (Figure S6E), consistent with GHSR1a and DRD2 specific heteromerization.

Next, we performed the red-ghrelin Tr-FRET assay on tissue isolated from different regions of mouse brain. Membrane preparations from striatum and hypothalamus were incubated with red-ghrelin (acceptor fluorophore), a specific antibody for DRD2 and cryptate labeled secondary antibody (donor fluorophore). Although membranes from the striatum exhibit a slightly higher FRET signal, the increase does not reach significance (Figure 8A). In hypothalamic membrane preparations, a significantly higher FRET signal is observed (198±27, compared to background, 100±5.7, p<0.05; Figure 8A) in agreement with relative levels of receptor mRNA (Figure 1). To test specificity we repeated the Tr-FRET assays on membrane preparations of brain tissues from ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− mice in parallel. Significantly higher FRET signals are observed in hypothalamus from ghsr+/+ mice compared to ghsr−/− mice (p<0.05; Figure 8B), illustrating the specificity of the Tr-FRET signal in the hypothalamus of wild-type mice. Again, Tr-FRET signals in the striatum did not reach statistical significance (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Detection GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in vivo by Tr-FRET and the dependence of the anorexigenic effect of a DRD2 agonist on GHSR1a.

(a) Tr-FRET signal detection on membrane preparations from striatum and hypothalamus after labeling with red-ghrelin (100 nM, acceptor fluorophore), antibody for DRD2 and cryptate labeled secondary antibody (10 nM, donor fluorophore). Non-specific FRET signal was measured on membranes in the presence 100 nM of red-fluorophore, antibody for DRD2and cryptate labeled secondary antibody (10 nM, donor fluorophore).

(b) Tr-FRET signals detected on membrane preparations of striatum and hypothalamus from ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− mice. Membranes were labeled in the presence of 100 nM red-ghrelin (acceptor), antibody for DRD2 and 10 nM cryptate labeled secondary antibody (donor).

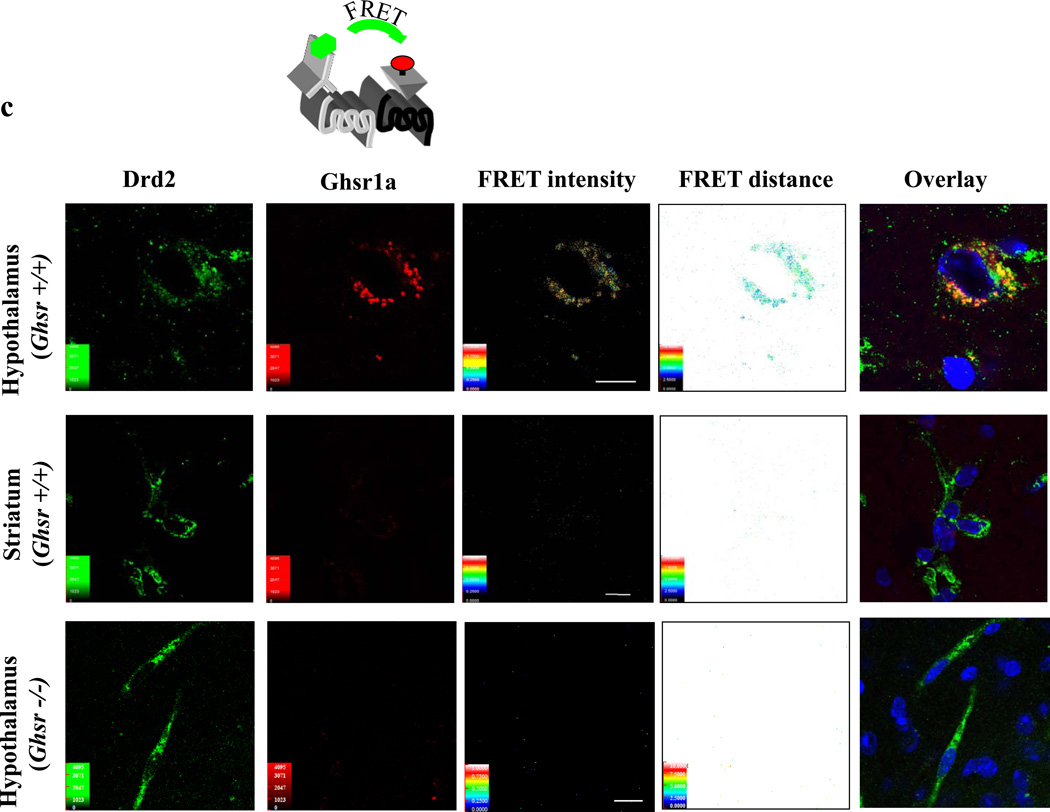

(c) Confocal microscope FRET analysis of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromer formation in ghsr+/+ mouse hypothalamic (upper panels) striatal (middle panels) neurons and ghsr−/− mouse hypothalamic neurons (lower panels). Brain slices were stained with 100 nM red-ghrelin (acceptor), DRD2 antibody and Cy3 labeled secondary antibody (donor). Red color indicates GHSR1a staining, green DRD2 localization. Microscopic analysis shows FRET intensity, distances separating the two receptors and co-localization of two receptors (overlay).

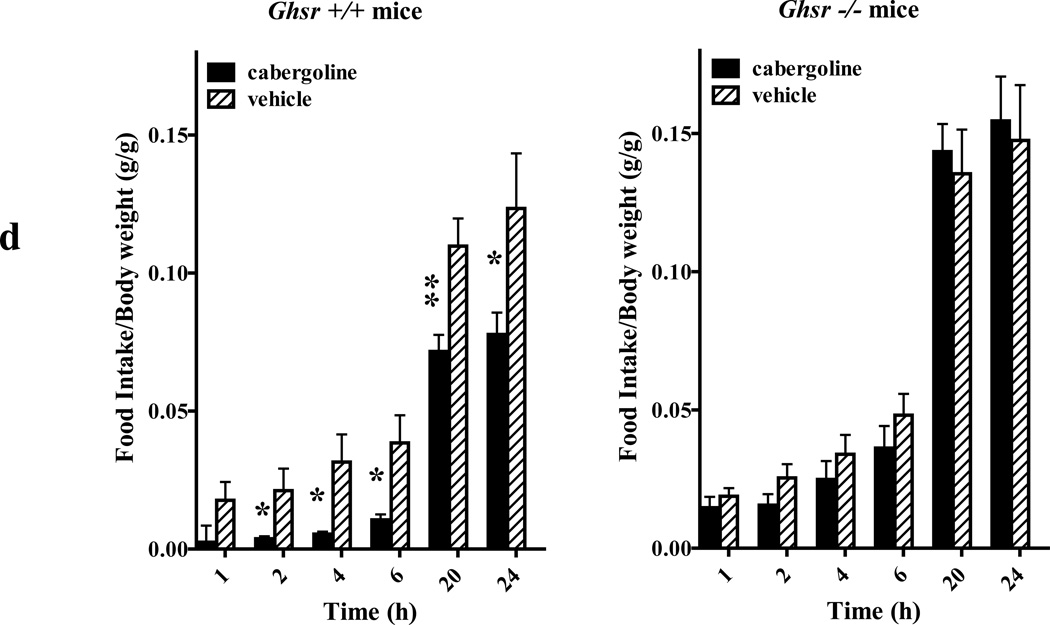

(d) Effect of cabergoline administration on food intake in ghsr+/+ mice (n=4 for cabergoline and n=4 for vehicle; left graph) and in ghsr −/− mice (n=5 for cabergoline and n=5 for vehicle; right graph). Mice were injected i.p. with cabergoline (0.5 mg/kg) in 100 µl of physiological saline or with 100 µl saline alone (vehicle). Food intake was measured at 1, 2, 4, 6, 20 and 24 h after injections. Average body weight mass of ghsr+/+ was 31.8g and ghsr−/− was 28.1g; * P<0.05; ** P<0.01 versus control vehicle treatments.

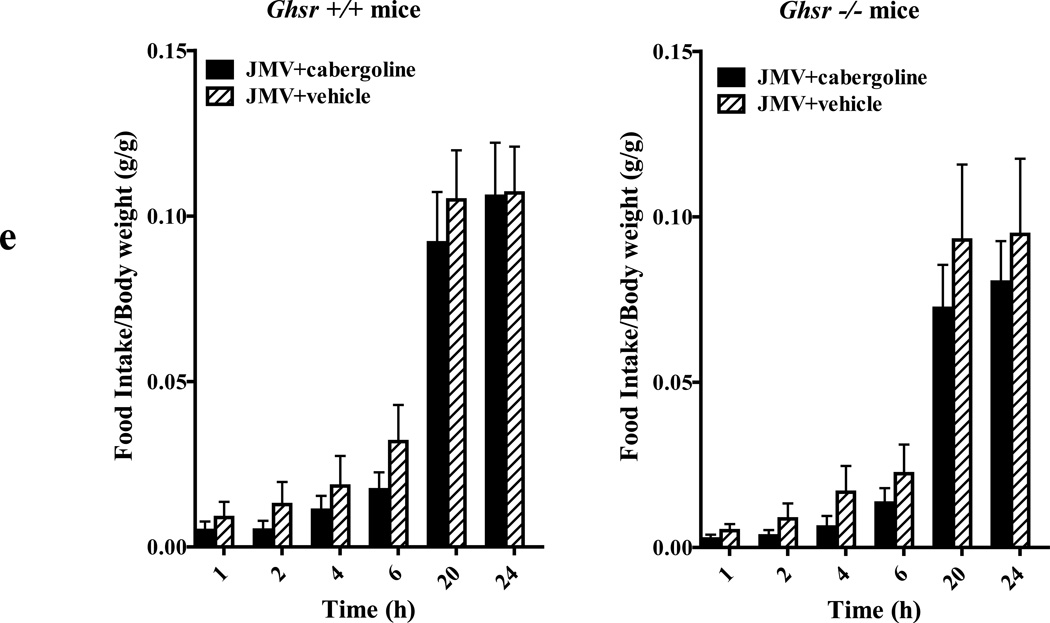

(e) The neutral GHSR1a selective antagonist JMV2959 antagonizes cabergoline induced reduction on food intake in ghsr +/+ mice (n=4 for cabergoline and n=4 for vehicle; left graph) and had no effect in ghsr −/− mice (n=5 for cabergoline and n=5 for vehicle; right graph). Mice were injected i.p. with JMV295 at 0.2 mg/kg dose, 30 min before cabergoline treatments (0.5 mg/kg). Food intake was measured at 1, 2, 4, 6, 20 and 24h after injection.

(f) Effect of cabergoline administration on food intake in ghrelin+/+ mice (n=6 for cabergoline and n=4 for vehicle, left graph) and in ghrelin −/− mice (n=5 for cabergoline and n=5 for vehicle, right graph). Mice were injected i.p. with cabergoline (0.5 mg/kg) in 100 µl of physiological saline or with 100 µl saline alone (vehicle). Food intake was measured at 1, 2, 4, 6, 20 and 24 h after injections. * P<0.05 versus control vehicle treatments.

We then tested for GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in brain slices from ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− mice. In the hypothalamus of ghsr+/+, but not ghsr−/− mice confocal FRET analysis shows that GHSR1a and DRD2 are in close proximity with a relative distance of 5–6 nm (50–60Å) and FRET intensity ranging from 0.4 to 0.6 (Figure 8C). In the striatum, FRET intensity signals are very weak (Figure 8C). To summarize, Tr-FRET analysis of membrane preparations and FRET analysis from single neurons by confocal microscopy confirm heteromer formation between natively expressed GHSR1a and DRD2 in the hypothalamus of wild-type mice.

Physiological relevance of GHSR1a interactions with DRD2

The in vivo detection of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers and in vitro cell-based data led us to ask whether preventing formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers would be associated with an altered behavioral phenotype. DRD2 activation suppresses appetite (Comings et al., 1996; Epstein et al., 2007; Stice et al., 2008). In cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 the DRD2 selective agonist cabergoline induces a dose-dependent mobilization of Ca2+ (Figure S7A), and treating mice with cabergoline (0.5 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg) results in dose dependent suppression of food intake (Figure S7B); therefore, to test whether cabergoline’s affect was dependent upon GHSR1a and DRD2 interactions we compared food-intake in ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− treated with cabergoline. In ghsr+/+ mice food intake is markedly reduced within 2 h of cabergoline treatment compared to vehicle-treated mice (p<0.05; Figure 8D, left graph), whereas food intake in ghsr−/− mice is unaffected by cabergoline treatment (Figure 8D, right graph).

In cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2, the GHSR1a neutral antagonist, JMV2959 (Moulin et al., 2007) attenuates dopamine-induced Ca2+ mobilization (Figure 7C). To test if inhibition of DRD2 signaling by JMV2959 in cells would translate to the whole animal we treated wild-type mice with JMV2959 prior to cabergoline treatment. Indeed, cabergoline-induced suppression of food intake in ghsr+/+ mice was prevented by pre-treatment with JMV2959 (0.2 mg/kg, p<0.05; Figure 8E left graph), whereas food intake in cabergoline treated ghsr−/− mice was unaffected by JMV2959 treatment (Figure 8E right graph).

In cell based assays we showed that GHSR1a modifies DRD2 signaling in the absence of ghrelin. Since both ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− produce endogenous ghrelin, to test for a possible role of endogenous ghrelin on DRD2 signaling in vivo we compared the effects of cabergoline treatment on food intake in ghrelin −/− and ghrelin +/+ mice. Cabergoline (0.5 mg/kg) significantly reduced food intake irrespective of genotype (Figure 8F). Hence, antagonism of the anorexigenic effect of cabergoline by JMV2959 (Figure 8E) is not dependent on endogenous ghrelin, but on the presence of GHSR1a, illustrating the physiological relevance of interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2 on dopamine signaling.

Discussion

We investigated the interaction of the GHSR1a and DRD2 signaling systems and found molecular, cellular, and physiological bases for functional and structural interactions in vivo and in vitro. Here we show that in mouse hypothalamic neurons co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 heteromers are formed. Heteromerization of GPCR’s is an important mechanism that can regulate receptor function. Receptor-receptor interactions potentially stabilize specific conformations and lead to coupling with discrete effectors resulting in heteromer specific signal transduction. Here we found that dopamine or a selective DRD2 agonist activates GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers inducing Gβγ and PLC-dependent mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Most importantly, this modification of DRD2 signaling is observed in the absence of ghrelin, showing that apo-GHSR1a behaves as an allosteric modulator of dopamine-DRD2 signaling. This finding resolves the paradox and documents a function for GHSR1a expressed in areas of the brain considered inaccessible to peripherally produced ghrelin and where there is no evidence of ghrelin production.

Subsets of neurons co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 were identified in ghsr-IRES-tauGFP mice by a combination of GFP and DRD2 immunohistochemistry. Co-localization is most abundant in hypothalamic neurons, consistent with results of in situ hybridization (Guan et al., 1997) and RT-PCR. We asked what effects co-expression of GHSR1a and DRD2 would have on dopamine signal transduction in these neurons. Using HEK293 cells, SH-SY5Y, GHSR-SH-SY5Y, and primary cultures of hypothalamic neurons we showed that co-expression of GHSR1a and DRD2 altered canonical DRD2 signal transduction resulting in dopamine-induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i. In this context mobilization of [Ca2+]i by dopamine is dependent upon Gβγ subunit activation of PLC and inositol phosphate pathways.

GHSR1a is present at extraordinary low levels in native tissues (Howard et al., 1996). A widely held belief, based on the basal activity exhibited by GHSR1a when expressed in heterologous systems at higher levels than in native tissues, is that GHSR1a basal activity is physiologically relevant. Although we do not share this belief, it was incumbent upon us to test whether GHSR1a basal activity might explain the effects of GHSR1a on modification of canonical DRD2 signaling. Perhaps, the most relevant example of basal activity of one GPCR modifying signaling of another by receptor crosstalk is co-expression of mGlu1a with GABAB receptor (Rives et al., 2009). In common with GHSR1a, mGlu1a couples to Gαq, and like DRD2, GABAB couples to Gαi/o. Co-expression of these receptors produces a synergistic increase in GABA-induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i. The authors concluded that potentiation of [Ca2+]i mobilization was a consequence of temporal integration of [Ca2+]i responses as a result of mGlu1a basal activity. However, in the context of GHSR1a and DRD2 co-expression we found no evidence of receptor crosstalk producing augmentation of [Ca2+]i in response to agonists of either receptor.

It is well known that expression of GHSR1a in cell lines at levels exceeding those observed in native tissues is accompanied by detectable basal activity. Therefore, in our studies we deliberately used low level GHSR1a expression commensurate with what is observed in native tissues. However, a case for a physiological role for GHSR1a basal activity was concluded from experiments showing inhibition of feeding in rats during a 6 day central infusion of the GHSR1a inverse agonist, [D-Arg1,D-Phe5,D-Trp7,9,Leu11]-substance P (Petersen et al., 2009). Although modest reductions in food intake and weight gain were observed, the results are ambiguous because the study was compromised by side-effects observed following cannulation and implantation of infusion pumps. Furthermore, this inverse agonist is not highly selective. Nevertheless, based on this report it was incumbent on us to rigorously test whether basal activity of GHSR1a explained modification of canonical DRD2 signaling.

We selected point mutants of GHSR1a described as exhibiting the same basal activity as WT-GHSR1a, and a mutant devoid of basal activity to test for correlation with modification of DRD2 signal transduction. There was no correlation between basal activity of the mutants and dopamine induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i. GHSR1a couples to Gαq (Howard et al., 1996); therefore, to eliminate possible basal activity we suppressed Gαq production by expressing Gαq siRNA in cells co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2. Dopamine-induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i was unaffected by inhibition of Gαq expression. Furthermore, inhibition of PKC signaling blocks GHSR1a signal transduction (Smith et al., 1997), but we show PKC inhibition does not inhibit dopamine-induced mobilization of [Ca2+]i. Collectively, these results preclude basal activity of GHSR1a as an explanation for modification of DRD2 signal transduction.

Our results are consistent with an allosteric mechanism associated with physical association between GHSR1a and DRD2. Indeed, the results of agonist cross-desensitization assays support this mechanism. GPCRs are known to form homo- and heteromers in vitro and these complexes can modulate receptor signaling and trafficking (Bulenger et al., 2005; Milligan, 2009; Terrillon and Bouvier, 2004). Although dimerization in vitro is well documented, its physiological relevance has been questioned because of the paucity of reports showing the existance of GPCR dimers in native tissue. Nevertheless, the functional requirement for dimerization in the case of the GABAB receptor is undeniable (Jones et al., 1998). We employed Tr-FRET methodology to test for formation of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers because its high sensitivity and high signal to noise ratio is ideal for detecting homo- and heteromers on cell surfaces at physiological levels of GPCR expression (Maurel et al., 2008) (Albizu et al., 2010). Tr-FRET assays using SNAP- and CLIP-tagged GHSR1a and DRD2 showed heteromers formed at equimolar concentrations of GHSR1a and DRD2. By comparing Tr-FRET signals obtained from combinations of SNAP- and CLIP-tagged DRD2, SNAP- and CLIP-tagged WT-GHSR1a and GHSR1a point mutants with associated dopamine-induced mobilization of Ca2+ we concluded that function correlates with the Tr-FRET signal produced by GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers.

The results of experiments with DRD2 and GHSR1a point mutants illustrate that heteromer formation is dependent upon GHSR1a conformation. However, to support a mechanism of allosteric modulation more subtle changes that do not cause dissociation of the heteromers must be induced. Conformation and dimerization of GPCRs is affected by inverse agonists and antagonists (Fung et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2005; Mancia et al., 2008; Vilardaga et al., 2008). A neutral antagonist or inverse agonist of one protomer can modify function of the other protomer via allostery (Smith and Milligan, 2010). In the case of CB1R and μ-opioid receptor where integration of signaling occurs through cross-talk mediated by basal activity, an inverse agonist, but not a neutral antagonist reduced activity (Canals and Milligan, 2008). In contrast, the GHSR1a neutral antagonist JMV2959 (Moulin et al., 2007), inhibits dopamine-induced Ca2+ release consistent with an allosteric affect associated with GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers. With DRD2 homomers, binding of the inverse agonist (sulpiride) to one protomer modifies the signal generated by the other (Han et al., 2009). Likewise, sulpiride modifies ghrelin-induced Ca2+ release by GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers consistent with allosteric modification of signaling between the protomers.

To test for endogenously formed GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in native tissue we performed Tr-FRET assays on hypothalamic and striatal membrane preparations isolated from ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− mouse brains. The highest FRET signals were observed in hypothalamic membranes from ghsr+/+ mice, illustrating GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromer formation. As confirmation we performed confocal microscope FRET analysis on brain slices from ghsr+/+ and ghsr−/− mice. The robust FRET signals in hypothalamic neurons of ghsr+/+, but not ghsr−/− mice show for the first time the existence of GHSR1a:DRD2 heteromers in native hypothalamic neurons.

It was important to determine whether interaction between GHSR1a and DRD2 was associated with a DRD2 dependent behavioral phenotype. For these experiments we selected the DRD2 agonist cabergoline. Cabergoline is widely used clinically for treatment of Parkinson disease and hyperprolactinemia and has greater selectivity for DRD2 compared to other dopamine and serotonin receptor subtypes (Kvernmo et al., 2006). Besides other pathways, DRD2 regulates feeding behavior (Fetissov et al., 2002; Palmiter, 2007), and humans treated with cabergoline experience weight loss (Korner et al., 2003). Because the hypothalamus is a key regulatory center for food intake, we hypothesized that cabergoline acts on these neurons to induce anorexia. Pharmacological doses of ghrelin increase food intake, therefore, it is possible that cabergoline inhibits food intake by lowering endogenous ghrelin concentrations, or by interfering with ghrelin signaling. Alternatively, cabergoline suppression of feeding may require the allosteric affect of GHSR1a on DRD2 signaling. To test these possibilities we compared food intake in ghsr+/+ mice and ghsr−/− mice treated with cabergoline. If cabergoline interfered with endogenous ghrelin signaling, food intake should be inhibited in both genotypes and perhaps exaggerated in ghsr−/− mice; however, ghsr−/− mice were completely refractory to cabergoline-induced anorexia, illustrating dependence on GHSR1a.

To test whether the allosteric interaction between DRD2 and GHSR1a could be targeted pharmacologically, we treated mice with the highly selective neutral GHSR1a antagonist JMV2959 prior to cabergoline treatment. As predicted by our hypothesis, JMV2959 blocked cabergoline-induced anorexia. The demonstration that JMV2959 treatment of WT mice recapitulates the phenotype observed in ghsr−/− mice indicates that resistance of ghsr−/− mice to cabergoline is further evidence of an allosteric function for GHSR1a on DRD2-mediated inhibition of food intake. This result also argues against possible developmental changes caused by ghsr ablation as an explanation of the resistance of ghsr−/− mice to cabergoline.

Although counter to evidence that ghrelin stimulates rather than inhibits feeding behavior, the unlikely possibility remained that blocking endogenous ghrelin signaling with either a GHSR1a antagonist or ablation of ghsr might overcome the inhibitory effect of cabergoline on food-intake. If this were true then ghrelin−/− mice, like ghsr−/− should be resistant to the anorexic effect of cabergoline. When food intake was compared in vehicle treated and cabergoline treated ghrelin+/+ and ghrelin−/− mice, suppression of food intake by cabergoline was identical in both genotypes. These results provide additional evidence that cabergoline-induced anorexia is dependent upon allosteric interactions between GHSR1a and DRD2.

Our findings are of fundamental importance because they support the notion that in subsets of neurons co-expressing GHSR1a and DRD2 allosteric modulation by GHSR1a results in a differential response to endogenous dopamine. Most importantly, we show that a neutral GHSR1a antagonist blocks dopamine signaling in neurons co-expressing DRD2 and GHSR1a, which allows neuronal selective fine-tuning of dopamine/DRD2 signaling because neurons expressing DRD2 alone will be unaffected. This provides exciting opportunities for designing the next generation of drugs with improved side-effect profile for treating psychiatric disorders associated with dysregulation of dopamine signaling.

Experimental Procedures

Small molecule molecule inhibitors of Gβγ subunit signaling were obtained from the chemical diversity set of the NCI/NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program. M119 is referenced as compound NSC 119910, M119B is referenced as compound NSC 119892 and M158C is referenced as compound NSC 158110.

Animals

Ghsr+/+, ghsr−/−, ghrelin+/+ and ghrelin−/− were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice for at least 15 generations (Sun et al., 2004). All studies were done in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Scripps Florida.

RT-PCR and detection of mRNA expression of ghsr1a and drd2 in mouse brain

Tissue extractions for analysis of gene expression were carried out on adult 3 month old mice. Mice were killed by decapitation after a brief exposure to carbon dioxide brains were removed and immediately dissected using a coronal brain matrix. Tissue homogenization, RNA isolation, cDNA template preparation and sequence of primers can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of mouse brain sections

Immunofluorescence was carried out on adult male ghsr-IRES-tauGFP mice as described previously (Jiang et al., 2006). Brains were quickly removed as described above, snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Frozen brains were embedded with Tissue-Tek (Sakura Finetek) and cut into 20 µm coronal sections using Leica CM1950 cryostat (Leica Microsytems). Detailed protocol for fixation and staining with primary and secondary antibodies of brain sections can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Plasmid constructs

The N-terminally HA-tagged GHSR1a was generated by introducing HA sequence into GHSR1a cDNA (Jiang et al., 2006) by PCR. The SNAP- and CLIP-tag receptor variants were generated by PCR (for template cDNA, SNAP- and CLIP empty vectors were purchased from Cisbio US, Bedford, MA) and subcloned into mammalian pcDNA3.1. The SNAP- and CLIP-F279L-GHSR1a was constructed by subcloning point mutant F279L-GHSR1a (Feighner et al., 1998) into SNAP- or CLIP-GHSR1a. The RXFP1 expression vector was described previously (Kern et al., 2007). HA- tagged DRD2 and Gαq expression vectors were purchased from Missouri cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). βARKct clone was the generous gift of Dr. R. Lefkowitz (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). The integrity of all constructs generated by PCR and subcloning was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Cell culture, plasmid and siRNA transfections

HEK293 (ATCC number: CRL-1573) and neuronal SH-SY5Y (ATCC number: CRL-2266) cells were grown routinely in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and 100 µg/ml of penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 95% air/5% CO2. HEK293 cells stably expressing aequorin (HEK-AEQ) were maintained in above media containing 500 µg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen). Mouse hypothalamic tissue of embryonic day 18 mouse was purchased from BrainBits (Springfield, IL), primary neurons were prepared and the [Ca2+]i mobilization assay performed after cultivating neurons in NbActiv4 neuronal culture medium (BrainBits). Detailed protocol for transient transfections and generation of stable SH-SY5Y cell line expressing GHSR1a can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Ca2+ mobilization assays

The aequorin bioluminescence assay was carried out as described previously (Feighner et al., 1998; Howard et al., 1996) and live cell Ca2+ mobilization assays in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells and primary hypothalamic neurons were performed with the Fluo-4 direct assay (Invitrogen), see detailed protocols in Supplemetary Methods.

Live Cell Time Resolved (Tr)-FRET

Labeling of cells was performed after 48 hours of transfection as described previously (Maurel et al., 2008). Cell labeling with terbium cryptate donor and acceptor fluorophore; and Time-resolved (Tr) FRET measurments were performed as described in Supplementary Methods.

Tr-FRET binding assays

Fluorescently-labeled ghrelin (red-ghrelin from Cisbio) binding assays were performed on batch labeled cells with terbium-cryptate. 48 h after transfection with SNAP-tagged receptors, cells were labeled with 100 nM of BG-TbK (Cisbio) substrate in 6-well plates by incubating for 1 h at 37°C (95% air/5% CO2) in DMEM containing 0.5% FBS. Cells were then detached, collected by centrifugation (1000 × g, 10 min) and washed three times with PBS. Pelleted cells were resuspended in Tris-KREBS buffer and seeded in 96-well plates (50×103 cells per well). Saturation binding, non-specific binding and completion binding experiments were performed as described in Supplementary Methods.

Tr-FRET assay on membrane preparations from mouse brain

Mouse brains were dissected as above,crude membrane preparations were isolated, labeled with biotin and added to streptavidin plates for labeling with donor and acceptor fluorophores (see details in Supplementary Methods). Red-ghrelin (100 nM) and mouse anti-DRD2 antibody (1:100 dilutions, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added and the plates incubated overnight at 4°C in the dark. To measure the background signal membranes were incubated with 100 nM of red-fluorophore and mouse anti-DRD2 antibody. Plates were washed twice with TMEP and incubated with terbium-kryptate labeled anti-mouse antibody (10 nM/well; Cisbio) for 2 h at 4°C in the dark. After two final washes, 400 mM KF in TMEP was added to each well and Tr-FRET signal was measured using an EnVision plate reader as described above.

FRET microscopy on brain slices

Mouse brain sections (20 µm) were processed for FRET studies. Sections were stained with red-ghrelin, primary mouse DRD2 antibody, secondary goat anti-mouse Cy3 labeled antibody and FRET microscopy was performred using Olympus FluoView 1000 (details in Supplementary Methods).

Food intake experiments

Age-matched WT, ghsr −/− or ghrelin −/− mice were housed individually for 1 week before food intake measurements. Mice were kept in a standard 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. light cycle facility and fed with a regular mouse chow. Mice were fasted for 16 h before cabergoline and JMV2959 administration. Cabergoline (Tocris) was dissolved in 0.9% saline (1 ml) acidified with 2% of phosphoric acid (30 µl) and administered at 0.5 mg/kg doses. Either cabergoline in 100 µl of 0.9% saline buffer or 100 µl of 0.9 % saline was administered intraperitoneally. JMV2959 was kind gift from Babette Aicher, Aeterna-Zentaris, Frankfurt am Main Germany. As described previously, JMV2959 was administered intraperitoneally (Moulin et al., 2007) at 0.2 mg/kg dose, 30 min before cabergoline treatments. Food intake was measured at 1, 2, 4, 6, 20 and 24h after injection.

Data analysis

The mean and the s.e.m. are presented for values obtained from the number of separate experiments indicated, and comparisons were made using two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA test. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Instat Software and differences judged to be statistically significant if P<0.05.

Highlights.

GHSR1a and DRD2 form heteromers in vitro and in vivo in hypothalamic neurons;

GHSR1a allosterically modifies DRD2 signaling by Gβγ dependent [Ca2+]i mobilization;

Anorexigenic effects of a DRD2 agonist are dependent upon ghsr expression;

A GHSR1a selective antagonist blocks the anorexigenic effect of a DRD2 agonist;

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Bryan Wharram for assistance with the food intake experiments. The drd2−/− mouse brain was a gift from Emiliana Borelli (Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of California Irvine). This work was supported by the grant from the US National Institutes of Health (R01AG019230 to R.G.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Albizu L, Cottet M, Kralikova M, Stoev S, Seyer R, Brabet I, Roux T, Bazin H, Bourrier E, Lamarque L, et al. Time-resolved FRET between GPCR ligands reveals oligomers in native tissues. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacci TM, Mathews JL, Yuan C, Lehmann DM, Malik S, Wu D, Font JL, Bidlack JM, Smrcka AV. Differential targeting of Gbetagamma-subunit signaling with small molecules. Science. 2006;312:443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.1120378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulenger S, Marullo S, Bouvier M. Emerging role of homo- and heterodimerization in G-protein-coupled receptor biosynthesis and maturation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D, Brownstein M. Aequorin-expressing mammalian cell lines used to report Ca2+ mobilization. Cell Calcium. 1993;14:663–671. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(93)90091-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, Milligan G. Constitutive activity of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor regulates the function of co-expressed Mu opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11424–11434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings DE, Gade R, MacMurray JP, Muhleman D, Peters WR. Genetic variants of the human obesity (OB) gene: association with body mass index in young women, psychiatric symptoms, and interaction with the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini VJ, Vicentini E, Sabbatini FM, Valerio E, Lepore S, Tessari M, Sartori M, Michielin F, Melotto S, Merlo Pich E, et al. GSK1614343, a Novel Ghrelin Receptor Antagonist, Produces an Unexpected Increase of Food Intake and Body Weight in Rodents and Dogs. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:158–168. doi: 10.1159/000328968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley MA, Smith RG, Diano S, Tschop M, Pronchuk N, Grove KL, Strasburger CJ, Bidlingmaier M, Esterman M, Heiman ML, et al. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonstrates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron. 2003;37:649–661. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit VD, Yang H, Sun Y, Weeraratna AT, Youm YH, Smith RG, Taub DD. Ghrelin promotes thymopoiesis during aging. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:2778–2790. doi: 10.1172/JCI30248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Temple JL, Neaderhiser BJ, Salis RJ, Erbe RW, Leddy JJ. Food reinforcement, the dopamine D2 receptor genotype, and energy intake in obese and nonobese humans. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:877–886. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner SD, Howard AD, Prendergast K, Palyha OC, Hreniuk DL, Nargund RP, Underwood D, Tata JR, Dean DC, Tan C, et al. Structural requirements for the activation of the human growth hormone secretagogue receptor by peptide and non-peptide secretagogues. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:137–145. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.1.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner SD, Tan CP, McKee KK, Palyha OC, Hreniuk DL, Pong S-S, Austin CP, Figureoa D, MacNeil D, Cascieri MA, et al. Receptor for motilin identified in the human gastrointestinal system. Science. 1999;284:2184–2188. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetissov SO, Meguid MM, Sato T, Zhang LH. Expression of dopaminergic receptors in the hypothalamus of lean and obese Zucker rats and food intake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R905–R910. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00092.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung JJ, Deupi X, Pardo L, Yao XJ, Velez-Ruiz GA, DeVree BT, Sunahara RK, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated oligomerization of beta(2)-adrenoceptors in a model lipid bilayer. EMBO J. 2009;28:3315–3328. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouselle D, Chaillou E, Caraty A, Bluet-Pajot M, Zizzari P, Tillet Y, Epelbaum J. Pulsatile cerebrospinal fluid and plasma ghrelin in relation to growth hormone secretion and food intake in the sheep. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1138–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan XM, Yu H, Palyha OC, McKee KK, Feighner SD, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Smith RG, Van der Ploeg LH, Howard AD. Distribution of mRNA encoding the growth hormone secretagogue receptor in brain and peripheral tissues. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;48:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Shi L, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Moreira IS, Urizar E, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Allosteric communication between protomers of dopamine class A GPCR dimers modulates activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:688–695. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst B, Holliday ND, Bach A, Elling CE, Cox HM, Schwartz TW. Common structural basis for constitutive activity of the ghrelin receptor family. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53806–53817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst B, Mokrosinski J, Lang M, Brandt E, Nygaard R, Frimurer TM, Beck-Sickinger AG, Schwartz TW. Identification of an efficacy switch region in the ghrelin receptor responsible for interchange between agonism and inverse agonism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15799–15811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard AD, Feighner SD, Cully DF, Arena JP, Liberator PA, Rosenblum CI, Hamelin M, Hreniuk DL, Palyha OC, Anderson J, et al. A receptor in pituitary and hypothalamus that functions in growth hormone release. Science. 1996;273:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglese J, Luttrell LM, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Touhara K, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Functionally active targeting domain of the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase: an inhibitor of G beta gamma-mediated stimulation of type II adenylyl cyclase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3637–3641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Betancourt L, Smith RG. Ghrelin amplifies dopamine signaling by crosstalk involving formation of GHS-R/D1R heterodimers. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1772–1785. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KA, Borowsky B, Tamm JA, Craig DA, Durkin MM, Dai M, Yao WJ, Johnson M, Gunwaldsen C, Huang LY, et al. GABA(B) receptors function as a heteromeric assembly of the subunits GABA(B)R1 and GABA(B)R2. Nature. 1998;396:674–679. doi: 10.1038/25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Agoulnik AI, Bryant-Greenwood GD. The low-density lipoprotein class A module of the relaxin receptor (leucine-rich repeat containing G-protein coupled receptor 7): its role in signaling and trafficking to the cell membrane. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1181–1194. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Inglese J, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6193–6197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner J, Lo J, Freda PU, Wardlaw SL. Treatment with cabergoline is associated with weight loss in patients with hyperprolactinemia. Obes Res. 2003;11:311–312. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvernmo T, Härtter S, Burger E. A review of the receptor-binding and pharmacokinetic properties of dopamine agonists. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia F, Assur Z, Herman AG, Siegel R, Hendrickson WA. Ligand sensitivity in dimeric associations of the serotonin 5HT2c receptor. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:363–369. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel D, Comps-Agrar L, Brock C, Rives ML, Bourrier E, Ayoub MA, Bazin H, Tinel N, Durroux T, Prezeau L, et al. Cell-surface protein-protein interaction analysis with time-resolved FRET and snap-tag technologies: application to GPCR oligomerization. Nat Methods. 2008;5:561–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguid MM, Fetissov SO, Varma M, Sato T, Zhang L, Laviano A, Rossi-Fanelli F. Hypothalamic dopamine and serotonin in the regulation of food intake. Nutrition. 2000;16:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. G protein-coupled receptor hetero-dimerization: contribution to pharmacology and function. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin A, Demange L, Bergé G, Gagne D, Ryan J, Mousseaux D, Heitz A, Perrissoud D, Locatelli V, Torsello A, et al. Toward potent ghrelin receptor ligands based on trisubstituted 1,2,4-triazole structure. 2. Synthesis and pharmacological in vitro and in vivo evaluations. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5790–5806. doi: 10.1021/jm0704550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung Y, Sibley DR. Protein kinase C mediates phosphorylation, desensitization, and trafficking of the D2 dopamine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49533–49541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmiter RD. Is dopamine a physiologically relevant mediator of feeding behavior? Trends in neurosciences. 2007;30:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchett AA, Nargund RP, Tata JR, Chen M-H, Barakat KJ, Johnston DBR, Cheng K, Chan WW-S, Butler BS, Hickey GJ, et al. The design and biological activities of L-163,191 (MK-0677): a potent orally active growth hormone secretagogue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7001–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen PS, Woldbye DP, Madsen AN, Egerod KL, Jin C, Lang M, Rasmussen M, Beck-Sickinger AG, Holst B. In vivo characterization of high Basal signaling from the ghrelin receptor. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4920–4930. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijl H. Reduced dopaminergic tone in hypothalamic neural circuits: expression of a "thrifty" genotype underlying the metabolic syndrome? Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;480:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rives M-L, Vol C, Fukazawa Y, Tinel N, Trinquet E, Ayoub MA, Shigemoto R, Pin J-P, Pre´zeau L. Crosstalk between GABAB and mGlu1a receptors reveals new insight into GPCR signal integration. EMBO J. 2009;28:2195–2208. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NJ, Milligan G. Allostery at G protein-coupled receptor homo- and heteromers: uncharted pharmacological landscapes. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:701–725. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RG, Pong S-S, Hickey GJ, Jacks TM, Cheng K, Leonard RJ, Cohen CJ, Arena JP, Chang CH, Drisko JE, et al. Modulation of pulsatile GH release through a novel receptor in hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:261–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RG, Van der Ploeg LH, Howard AD, Feighner SD, Cheng K, Hickey GJ, Wyvratt MJ, Jr, Fisher MH, Nargund RP, Patchett AA. Peptidomimetic regulation of growth hormone secretion. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:621–645. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.5.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Spoor S, Bohon C, Small DM. Relation between obesity and blunted striatal response to food is moderated by TaqIA A1 allele. Science. 2008;322:449–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1161550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Asnicar M, Saha PK, Chan L, Smith RG. Ablation of ghrelin improves the diabetic but not obese phenotype of ob/ob mice. Cell Metab. 2006;3:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wang P, Zheng H, Smith RG. Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4679–4684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305930101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrillon S, Bouvier M. Roles of G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga J-P, Nikolaev VO, Lorenz K, Ferrandon S, Zhuang Z, Lohse MJ. Conformational cross-talk between alpha2A-adrenergic and mu-opioid receptors controls cell signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:126–131. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Baler RD. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake: implications for obesity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucetic Z, Reyes TM. Central dopaminergic circuitry controlling food intake and reward: implications for the regulation of obesity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:577–593. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, Brynes AE, Frost GS, Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5992. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.