Abstract

The determination of prognosis for B-Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is known to be related to the multiple differences in tumor cell biology. Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 are two markers linked to germinal center B cells. Both markers are thought to have an effect on prognosis of mature B-cell neoplasms. Forty-four patients with chronic B-cell neoplasm were included; Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 expression by immunohistochemistry was examined. Bcl-2 protein was positive in 36.4% (16 of 44) of cases (62.5% of follicular lymphoma, 16.7% of mantle cell lymphoma and 30% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma); the positive group implying a bad prognostic effect of the marker in NHL. Bcl-6 was positive in 13.6% (6 of 44) of cases (11.1% of mantle cell lymphoma and 40% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) and its positivity implies a better disease course. Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 can be used as prognostic marker in NHL.

Key words: Bcl-2, Bcl-6, Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Introduction

The determination of prognosis for each of the Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) variants is known to be related to the multiple differences in tumor cell biology (cytogenetics, immunophenotype, growth fraction, cytokine production) found within each of the specific disease variants.1–3

Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 are two markers linked to germinal center B cells. The Bcl-2 gene, located at chromosome 18q21, encodes for a 25kd protein located mainly in the mitochondrial membrane. This Bcl-2 protein is an anti-apoptosis factor that is important in normal B-cell development and differentiation. Bcl-2 overexpression provides a survival advantage for malignant B cells and is thought to play a critical role in resistance to chemotherapy.4

The Bcl-6 gene, located at chromosome 3q27, encodes a 79kd DNA binding protein and transcriptional repressor that appears to be involved in mediating growth suppression.5 In lymphoid tissues, the Bcl-6 protein is expressed in germinal center B cells in secondary follicles in both the dark (centroblast-rich) and light (centrocyte-rich) zones.6

Immunohistochemical studies of the prognostic value of Bcl-6 expression led to discordant results. Some supported its ability to predict for a better overall survival rate, whereas others found no difference in overall survival rates.7

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Forty-four newly diagnosed B-NHL adult patients attending the hematology unit of the clinical pathology department, Ain Shams University took part in the study. Patients were recruited to the study on the basis of clinical and laboratory criteria of B-NHL. All patients were subjected to clinical sheet details, complete blood count with examination of PB smears stained with Leishman stain, bone marrow aspiration, bone marrow trephine biopsy, immunophenotyping using lymphoproliferative disorder panel (CD19, CD5, CD10, CD11c, CD20, CD22, CD23, CD38, CD79b, FMC7, CD103, CD25, kappa and lambda light chains). Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 immunostaining was performed on fixed bone marrow trephine biopsy specimen.

The diagnosis of NHL was confirmed by tissue biopsy in 40 patients (lymph node biopsy in 38 patients and liver biopsy in 2 patients). In the remaining 4 patients, bone marrow was the first diagnostic material. The 44 NHL cases comprised 18 mantle cell lymphomas (MCL), 16 follicular lymphomas (FL) and 10 diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL).

Methods

Two milliliter peripheral blood samples were collected in a sterile EDTA containing vaccutainers for CBC and immunophenotyping. BM aspiration was withdrawn, a few drops were put on glass slides for morphological examination and 1 mL into sterile EDTA containing vacutainers for immunophenotyping. BM trephine core biopsy was obtained and transferred immediately in a sterile plastic cup containing aldehyde solution fixative.

Immunohistochemistry

Fixation was performed for 24 h; decalcification of the core was performed using disodium ethylene-diamine-tetra acetic acid for 48 h. This was followed by passing the core in serial concentrations of ethyl alcohol (50%, 70%, 85%, 90%, and 100%) ending with xyelene then wax followed by paraffin embedding.

Serial 3-µm sections were cut from the paraffin block, mounted on positively charged slides and dried overnight in a 60°C oven. Sections were then deparaffinized in xylene for 24 h and hydrated in a descending grades of alcohol; 100%, 90%, 85% and 70%. Antigen unmasking was performed by heat induced an epitope retrieval method by placing the slides in a plastic Coplin jar filled with citric acid buffer so that the solution covers the slides, then placing the jar in a microwave at 800Watt for 20 min (divided into 4 cycles 5 min each). The Coplin jar was then removed from the oven and allowed to cool for 15 min.

Slides were placed in a humidified chamber and rinsed three times in phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation of the tissue section with 3% hydrogen peroxide in water for 30 min. After washing, the tissue sections were then incubated with the primary monoclonal antibody, ready to use Bcl-2 and 1:10 dilution in Bcl-6. Two hundred µl of the monoclonals were added for 1 h at room temperature with Bcl-2 and overnight at 4°C with Bcl-6.

The Streptavidin biotin method was used as a detection kit (LSAB2, Dako, Denmark). Tissue sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 40 min, then with Streptavidin conjugated enzyme for 30 min during which the 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate chromogen was freshly prepared then added onto the tissue section for 10 min in the dark.

The sections were counterstained in Meyer hematotoxylin, dehydrated, then put in xyelene and cover-slipped by DPX mount media and examined under a light microscope.

The positivity of the immunostaining was detected by percentage of positive cells and intensity of staining. For Bcl-2 the positivity cut off was considered when the reactivity of lymphoma cells with antibodies was more than 20%8 and was more than 10% for Bcl-6.9

The pattern of staining was also considered. For Bcl-2, membranous and cytoplasmic patterns were considered positive. For Bcl-6, positivity was detected if the pattern of staining was unclear.

Treatment regimen

Patients with NHL were treated with chemotherapy protocols with or without regional radiation therapy. The used therapeutic protocol was CHOP regimen; cyclophosphamide 650 mg/m2 day, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 up to 2 mg/m2 and doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 were given in day one whereas prednisone in a dose of 40 mg/m2 was administrated from day 1 till day 5. Cycles were repeated at intervals of 3–4 weeks according to the tumor volume and performance status of patients. Rituximab was added to CHOP (R-CHOP) for B-cell lymphomas with aggressive histology.10,11

Follow up

The follow-up strategy used to assess remission included history, physical examination, serum LDH and CBC after 2–4 cycles according to the International Workshop Group (IWG) criteria.12,13 Follow-up ranged from 12 to 30 months with a mean of 19.5±0.7 months. Response to therapy was assessed at the end of induction and complete remission (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all physical and radiographic evidence of lymphoma for at least four weeks after systemic chemotherapy and/ or radiation.14 In addition, patients with initial BM involvement were required to have clearing (as determined by repeated aspiration and biopsy) to be categorized as complete responders. Non-responders included patients in partial remission where a reduction in the size of measurable lesions by at least 50% occurred with no new lesions appearing and resistant cases who had no response to the used chemotherapeutic regimen. Relapse was determined as the recurrence of lymphoma in patients who had been in CR for at least four weeks.12

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a social science statistical package (SPSS version 15.0.1). The following tests were performed: descriptive statistics including quantitative data (mean ± standard deviation (SD) for parametric, and in the form of median and range in non-parametric results), qualitative data (number and percentage), analytical statistics including χ2, Fisher's exact test, Wilcoxon Rank-sum test (Z-value) and quantitative parametric data was analyzed using Student's t-test (t-value). The overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates along with standard error (SE) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and comparison between groups was made using a log rank test. P values ≤0.05 and ≤0.01 were considered significant and highly significant, respectively, in all analyses.

Results

There were 26 males and 18 females with a male to female ratio 1.4:1.0. Ages ranged from 20 to 70 years old with a mean of 45±15.2 years. The results of this study are summarized in Tables 1–3 and Figures 1–5.

Table 1. Details of Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 expression in different groups of chronic B cell neoplasms.

| N. of cases | Bcl-2 positive n (%) | Bcl-6 positive n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 16 | 10 (62.5) | 0 (0) |

| MCL | 18 | 3 (16.7) | 2 (11.1) |

| DLBCL | 10 | 3 (30) | 4 (40) |

| Total | 44 | 16 (36.4) | 6 (13.6) |

Table 3. Comparing Bcl-6 expression and prognostic parameters in NHL group.

| Parameter | Bcl-6 positive | Bcl-6 negative | P | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. cases | % cases | N. cases | % cases | ||||

| Age (mean) | ≥45 yrs | 0 | 0 | 28 | 73.7 | 0.001 | S |

| <45 yrs | 6 | 100 | 10 | 26.3 | |||

| Sex (mean) | M | 2 | 33.5 | 24 | 63.2 | 0.167 | NS |

| F | 4 | 66.5 | 14 | 36.8 | |||

| Hb g/dL (mean) | ≥10 | 2 | 33.5 | 20 | 52.6 | 0.38 | NS |

| <10 | 4 | 66.5 | 18 | 47.4 | |||

| Plt ×109/L (mean) | ≥150 | 6 | 100 | 20 | 52.6 | 0.028 | S |

| <150 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 47.4 | |||

| TLC ×109/L (mean) | ≥8 | 2 | 33.5 | 12 | 31.6 | 0.932 | NS |

| <8 | 4 | 66.5 | 26 | 68.4 | |||

| LDH IU/L (mean) | ≥500 | 4 | 66.5 | 22 | 57.9 | 0.685 | NS |

| <500 | 2 | 33.5 | 16 | 42.1 | |||

| Stage | I | 2 | 33.5 | 4 | 10.5 | 0.388 | NS |

| II | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15.8 | |||

| III | 2 | 33.5 | 12 | 31.6 | |||

| IV | 2 | 33.5 | 16 | 42.1 | |||

| Pattern | Diffuse | 0 | 0 | 6 | 15.8 | 0.26 | NS |

| Patchy | 2 | 33.5 | 12 | 31.6 | |||

| Interstitial | 0 | 0 | 8 | 21.0 | |||

| Mixed | 4 | 66.5 | 12 | 31.6 | |||

| Therapeutic | Responders | 4 | 66.5 | 16 | 42.1 | 0.26 | NS |

| Response | Non-responders | 2 | 33.5 | 22 | 57.9 | ||

| Clinical | Complete remission | 6 | 100 | 18 | 47.4 | 0.016 | S |

| outcome | Relapse | 0 | 0 | 20 | 52.6 | ||

| Fate | Alive | 6 | 100 | 25 | 78.9 | 0.088 | NS |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 13 | 21.1 | |||

S, significant, NS, non-significant. TLC, total leukocytic count; Hb, hemoglobin; Plts, platelets; BML, bone marrow lymphocytes; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

Unfavorable = survival ≤ 12 months, Favorable = survival > 12 months.

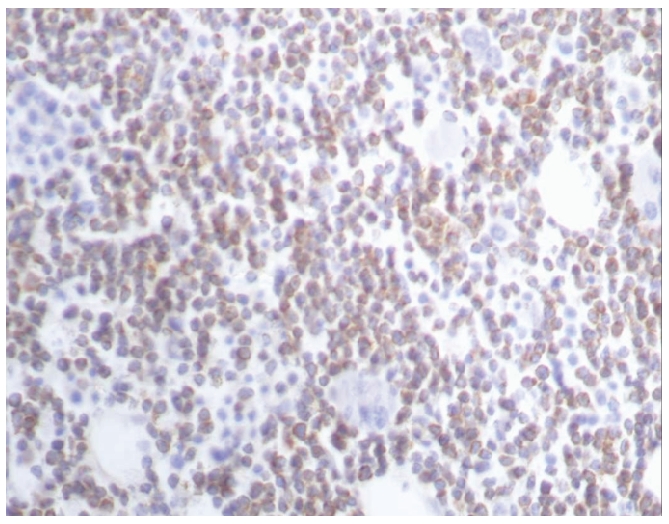

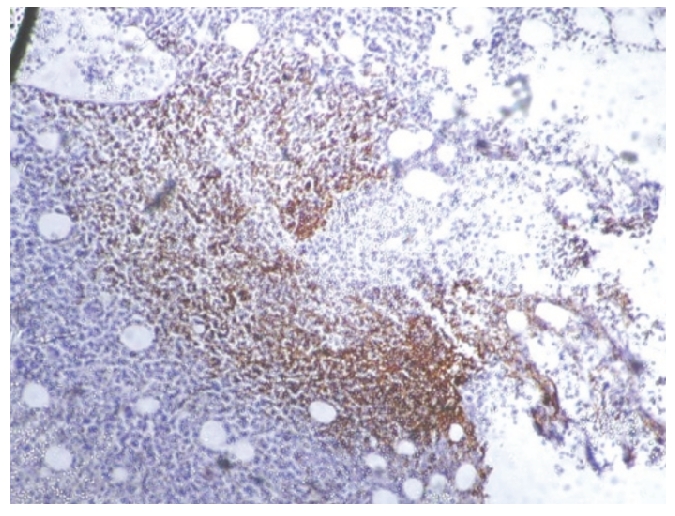

Figure 1.

Bcl-2 positivity in a case of follicular lymphoma (A): ×40.

Figure 5.

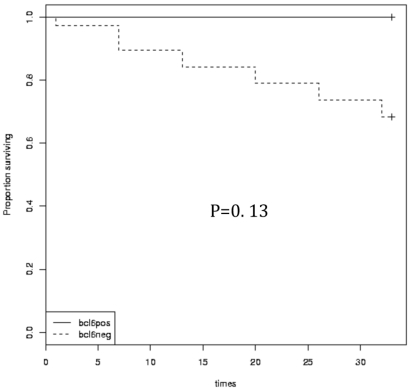

Kaplan-Meier overall survival and disease-free survival times in relation to Bcl-6 protein expression.

Bcl-2 protein was positive in 36.4% (16 of 44) of cases with the most frequent expression in the FL group (P=0.019); 62.5% of FL, 16.7% of MCL and 30% of DLBCL. Bcl-6 was positive in 13.6% (6 of 44) of cases with the most frequent expression in the DLBCL group (P=0.014) (11.1% of MCL and 40% of DLBCL) (Table 1).

Relation of Bcl-2 protein expression to clinical and laboratory prognostic factors

On comparing Bcl-2 expression with various prognostic parameters, a statistically significant difference was obtained in platelets count in which 75% of Bcl-2 positive cases were thrombocytopenic (P=0.001). A higher serum LDH serum level was detected in Bcl-2 positive cases compared to Bcl-2 negative group and the difference was statistically significant (P=0.004). On the other hand, no statistical significance was found as regards age, staging, total leukocytic count, hemoglobin level and pattern of BM infiltration (Table 2 and Figure1).

Table 2. Comparing Bcl-2 expression and prognostic parameters in NHL group.

| Parameter | Bcl-2 positive | Bcl-2 negative | P | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. cases | % cases | N. cases | % cases | ||||

| Age (mean) | ≥45 yrs | 12 | 75 | 16 | 57.1 | 0.236 | NS |

| <45 yrs | 4 | 25 | 12 | 42.9 | |||

| Sex (mean) | M | 10 | 62.5 | 16 | 57.1 | 0.728 | NS |

| F | 6 | 37.5 | 12 | 42.9 | |||

| Hb g/dL (mean) | ≥10 | 8 | 50 | 14 | 50 | 1 | NS |

| <10 | 8 | 50 | 14 | 50 | |||

| Plt ×109/L (mean) | ≥150 | 4 | 25 | 22 | 78.6 | 0.001 | HS |

| <150 | 12 | 75 | 6 | 21.4 | |||

| TLC ×109/L (mean) | ≥8 | 8 | 50 | 6 | 21.4 | 0.052 | NS |

| <8 | 8 | 50 | 22 | 78.6 | |||

| LDH IU/L (mean) | ≥500 | 14 | 87.5 | 12 | 42.9 | 0.004 | HS |

| <500 | 2 | 12.5 | 16 | 57.1 | |||

| Stage | I | 0 | 0 | 6 | 21.4 | 0.239 | NS |

| II | 2 | 12.5 | 4 | 14.3 | |||

| III | 6 | 37.5 | 8 | 28.6 | |||

| IV | 8 | 50 | 10 | 35.7 | |||

| Pattern | Diffuse | 4 | 25 | 2 | 7.2 | 0.36 | NS |

| Patchy | 4 | 25 | 10 | 35.7 | |||

| Interstitial | 2 | 12.5 | 6 | 21.4 | |||

| Mixed | 6 | 37.5 | 10 | 35.7 | |||

| Therapeutic | Responders | 2 | 12.5 | 18 | 64.3 | 0.001 | HS |

| response | Non-responders | 14 | 87.5 | 10 | 35.7 | ||

| Clinical | Complete remission | 2 | 12.5 | 22 | 78.6 | 0.001 | HS |

| outcome | Relapse | 14 | 87.5 | 6 | 21.4 | ||

| Fate | Alive | 7 | 43.8 | 24 | 85.7 | 0.003 | HS |

| Death | 9 | 56.2 | 4 | 14.3 | |||

S, significant; NS, non-significant; TLC, total leukocytic count; Hb, hemoglobin; Plts, platelets; BML, bone marrow lymphocytes; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Impact of Bcl-2 protein expression on response to therapy and clinical outcome

This study showed that 87.5% of patients with positive Bcl-2 protein expression significantly developed resistance to the therapeutic regimens adopted at the end of induction (P=0.001). Interestingly, these patients also displayed a poor clinical outcome experiencing higher relapse and mortality rates than their negative counterparts (P=0.001 and P=0.003, respectively).

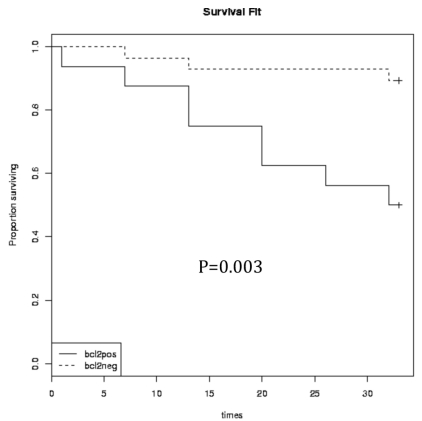

Bcl-2 expression in relation to patients' survival

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed significantly shorter OS and DFS times in B-NHL patients with Bcl-2 protein expression (P<0.05). The estimated 30-month OS survival rate was 44% in Bcl-2 positive patients compared to 85% in negative cases (log rank 8.7; P=0.003) and DFS rate was 12% versus 64% (log rank, 19.13; P=0.001) (Figure 3).

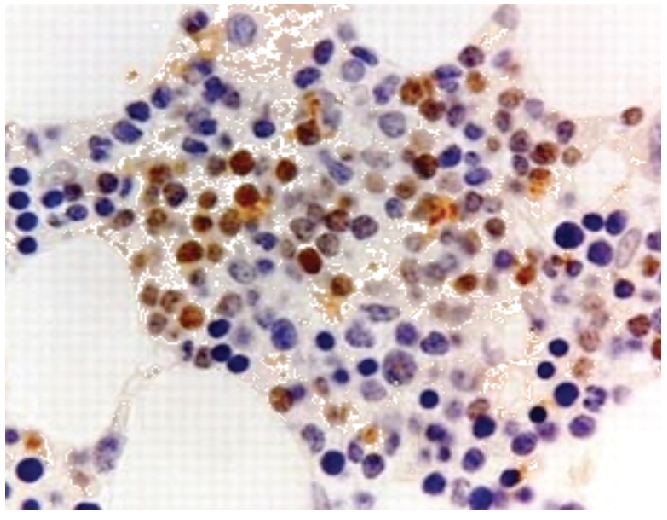

Figure 3.

Bcl-6 positivity in a case of DLBCL (×40).

Relation of Bcl-6 protein expression to clinical and laboratory prognostic factors

A statistically significant difference (P=0.001) was detected among the studied patients as regards age in which all the Bcl-6 positive cases were below the age of 45 years. In addition, a statistically significant difference was also obtained (P=0.028) in platelet count in which all Bcl-6 positive cases had a normal platelet count. No statistically significant difference was seen as regards other prognostic factors (P>0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bcl-2 positivity in a case of follicular lymphoma (B): ×10

Impact of Bcl-6 protein expression on response to therapy and clinical outcome

No statistically significant difference (P>0.05) was detected among patients with positive Bcl-6 protein expression as regards response to the therapeutic regimens adopted and mortality rates. However, a significantly lower relapse rate was detected in patients with positive Bcl-6 protein than in patients with negative expression (P=0.016).

Bcl-6 expression in relation to patients' survival

As regards Bcl-6 expression, results of survival analysis were consistent among Bcl-6 positive and negative patients (P>0.05). Nevertheless, OS and DFS were higher in patients exhibiting this marker (OS 100% versus 79% and DFS 66% versus 45%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival and disease-free survival times in relation to Bcl-2 protein expression.

Discussion

Several prognostic parameters were used in B-NHL to detect patients' outcome. To detect the value of Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 in diagnosis and prognosis of such diseases, immunostaining of Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 was performed for 44 patients with B-NHL. In this study, using a cut off 20% or more, Bcl-2 protein was positive in 36.4% (16 of 44) of NHL cases (62.5% of FL, 16.7% of MCL and 30% of DLBCL cases).

Studying Bcl-2 in lymphoma cases, Papakonstantinous et al.15 proved that the expression of Bcl-2 protein is not restricted to B-cell lymphomas bearing the t(14; 18) translocation and they showed the complete absence of any correlation between BCL-2 gene rearrangements and Bcl-2 protein expression in NHL. Ben-Ezra and King16 have suggested that Bcl-2 alone is useful in discriminating FL and benign lymphoid aggregates. In spite of the fact that the absence of Bcl-2 was highly specific for benign lymphoid aggregates, the expression of Bcl-2 in some benign and atypical lymphoid aggregates in the study by West et al.17 did not make Bcl-2 a specific marker for the detection of FL in bone marrow biopsy specimens. In addition, Llanos et al.18 stated that Bcl-2 expression is related to the grade of FL being highest in grade I and lowest in grade III, which matches with our negative cases where 5 of 6 of our negative Bcl-2 FL cases were of grade III.

The percentage of positive Bcl-2 in MCL cases was surprisingly low (16.7%). In fact, our negative MCL cases gave minimal positivity ranging from 5 to 20%; yet we considered them negative results according to the previously agreed cut off. Navratile et al.19 also found that Bcl-2 is expressed in low grade but not high grade lymphoma, and although MCL looks like a slow growing, low-grade tumor under the microscope, it grows fast and behaves like a high-grade lymphoma.

Bcl-2 protein expression was studied in relation to treatment response and clinical outcome, revealing a statistical significance, where a high tendency for developing resistance and a poor clinical outcome with significantly shorter OS and DFS were shown in Bcl-2 positive compared to negative patients. Comparing Bcl-2 to prognostic parameters in the NHL group in the current study, there was a significantly higher LDH level and a significantly lower platelet count in Bcl-2 positive NHL cases.

Hadzi-Pecova and his co-workers20 confirmed that the expression of Bcl-2 protein is significantly present in advanced compared with early stages of B-cell lymphoma. Similarly, high Bcl-2 expression by Hermine et al.21 was more frequently associated with stages III and IV. However, according to Hadzi-Pecova et al.,20 Bcl-2 expression did not show any significant influence either on total survival or on disease-free survival.

Although some reports failed to show any impact of Bcl-2 protein expression on survival of DLBCL cases,22,23 subsequent studies have reported that Bcl-2-positive cases have a worse disease-free survival.24 Recently, Hallack Neto et al.25 found a prognostic significance for Bcl-2 protein regarding overall survival.

Llanos et al.18 found no significant differences regarding the prognostic effect of Bcl-2 expression between FL patient groups. On the contrary, they observed a trend toward poorer survival among DLBCL patients with high Bcl-2 expression. Moreover, Iqbal et al.4 specified that Bcl-2 expression is associated with poor survival in the activated B cell-like subgroup of DLBCL but not in the germinal center B-cell subgroup. As for Bcl-6, the current study showed positivity in 13.6% (6 of 44) of NHL cases (11.1% of MCL and 40% of DLBCL cases). Despite the fact that FL usually stains Bcl-6 positive in lymph nodes, bone marrow lymphoid aggregates are less likely to express Bcl-6 as experienced by West et al.. In their study, only 12 out of 26 FL cases (i.e. 46%) were positive for Bcl-6 in their bone marrow specimens. They gave two explanations for this referring either to the nature of FL or the micro-environment of the bone marrow.17

All Bcl-6 positive cases were below the age of 45 years and had a normal platelet count. The current study found no relation between therapeutic response, OS and DFS on the one hand, and Bcl-6 expression on the other hand. However, a significantly lower relapse rate was found in patients with positive Bcl-6 protein.

Some authors suggested expression of Bcl-6 to be a prognostic marker in DLBCL26–28 but others have contradicted this.7,29,30 These differences may partly be explained by the differences in the cut off value (10–30%) for a positive staining in these studies. Also, differences in staining techniques may be of importance, for instance, in one study using the EnVision method and a low cut off of 10%, as much as 97% of cases were found positive for Bcl-6.9

Expression of Bcl-6 by Holler et al.8 had identified prognostically relevant favorable subgroups. Also Lossos et al.27 observed a strong predictive value for survival. In a study by Colomo et al.,30 Bcl-6 was expressed in 91% of DLBCL cases (23% Bcl-6 alone and 49% with other markers). The group of patients with restricted expression of Bcl-6 presented with earlier stage, low-risk IPI and normal LDH values. However, although this group of patients had the highest overall survival rate, the difference did not reach statistical significance. The reasons for these discordant results in different studies are not clear but they may be related in part to the heterogeneity of the selected patients. The aberrant expression of Bcl-6 in MCL found in the current study was also experienced by some authors. Only one of 20 MCL cases studied by Chuang et al.31 expressed Bcl-6. Similarly, Gualco et al.32 found Bcl-6 expression in 12% of the MCL cases.

In conclusion, Bcl-2 and Bcl-6 are found frequently in B-NHL and both proteins should be considered as reliable prognostic markers. Bcl-2 positive patients were associated with poor prognosis as well as short OS and DFS times whereas Bcl-6 positive patients were associated with a favorable prognosis. This indicated their potential as promising targets for therapeutic intervention. However, prospective studies with more patients in each group together with a longer follow up are recommended.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inamdar KV, Bueso-Ramos CE. Pathology of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an update. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:363–89. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staudt LM. Molecular diagnosis of the hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1777–1777. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iqbal J, Neppalli VT, Wright G, et al. BCL-2 expression is a prognostic marker for the activated B-cell-like type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:961–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsi ED, Yegappan S. Lymphoma immunophenotyping: a new era in paraffin-section immunohistochemistry. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:218–39. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilalovic N, Blystad AK, Golouh R, et al. Expression of Bcl-6 and CD10 protein is associated with longer overall survival and time to treatment failure in follicular lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:34–42. doi: 10.1309/TNKL-7GDC-66R9-WPV5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leval L, Harris NL. Variability in immunophenotype in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its clinical relevance. Histopathology. 2003;43:509–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2003.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Höller S, Horn H, Lohr A, et al. A cytomorphological and immunohistochemical profile of aggressive B-cell lymphoma: high clinical impact of a cumulative immunohistochemical outcome predictor score. J Hematop. 2009;2:187–94. doi: 10.1007/s12308-009-0044-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linderoth J, Jerkeman M, Cavallin-Ståhl E, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of CD23 and CD40 may identify prognostically favorable subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:722–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone. Blood. 2005;106:3725–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath B, Demeter J, Eros N, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: Remission after rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:885–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hampson FA, Shaw AS. Response assessment in lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elis A, Blickstein D, Klein O, et al. Detection of relapse in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Role of routine follow-up studies. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:41–4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papakonstantinous G, Verbeke C, Hastka J, et al. Bcl-2 expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas is not associated with Bcl-2 gene rearrangements. Brit J Haemat. 2001;113:383–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben-Ezra JM, King BE, Harris AC, et al. Staining for Bcl-2 protein helps to distinguish benign from malignant lymphoid aggregates in bone marrow biopsies. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:560–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West RB, Warnke RA, Natkunam Y. The usefulness of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of follicular lymphoma in bone marrow biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:636–43. doi: 10.1309/W3QX-WJ1C-WG2K-225V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llanos M, Alvarez-Argüelles H, Alemán R, et al. Prognostic significance of Ki-67 nuclear proliferative antigen, Bcl-2 protein, and p53 expression in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2001;18:15–22. doi: 10.1385/MO:18:1:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navratil E, Gaulard P, Kanavaros P, et al. Expression of the Bcl-2 protein in B-cell lymphomas arising from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:18–21. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadzi-Pecova L, Petrusevska G, Stojanovic A. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: immunologic prognostic studies. Prilozi. 2007;28:39–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermine O, Haioun C, Lepage E, et al. Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 protein expression in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) Blood. 1996;87:265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang SC, Visser L, Hepperle B, et al. Clinical significance of Bcl-2-MBR gene rearrangement and protein expression in diffuse large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: an analysis of 83 cases. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:149–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller TP, Levy N, Bailey NP, et al. The Bcl-2 gene translocation t(14;18) identifies a subgroup of patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma having an indolent clinical course with late relapse. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1994;13:370–370. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piris MA, Pezzella F, Martinez-Montero JC, et al. p53 and Bcl-2 expression in high-grade B-cell lymphomas: correlation with survival time. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:337–41. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallack Neto AE, Siqueira SA, et al. Bcl-2 protein frequency in patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128:14–7. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrans SL, O'Connor SJM, Evans PAS, et al. Rearrangement of the BCL-6 locus at 3q27 is an independent poor prognostic factor in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:322–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lossos IS, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, et al. Ongoing immunoglobulin somatic mutation in germinal center B cell-like but not in activated B cell-like diffuse large cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10209–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berglund M, Thunberg U, Amini RM, et al. Evaluation of immunophenotype in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its impact on prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1113–20. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dogan A, Bagdi E, Munson P, et al. CD10 and BCL-6 expression in paraffin sections of normal lymphoid tissue and B-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:846–52. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colomo L, López-Guillermo A, Perales M, et al. (2003): Clinical impact of the differentiation profile assessed by immunophenotyping in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:78–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuang SS, Huang WT, Hsieh PP, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma in Taiwan: clinicopathological and molecular study of 21 cases including one cyclin D1-negative tumor expressing cyclin D2. Pathol Int. 2006;56:440–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gualco G, Weiss LM, Harrington WJ, Jr, et al. BCL-6, MUM1, and CD10 expression in mantle cell lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:103–8. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181bb9edf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]