Abstract

Objective To assess the effect of the UK Committee on Safety of Medicines’ announcement in January 2005 of withdrawal of co-proxamol on analgesic prescribing and poisoning mortality.

Design Interrupted time series analysis for 1998-2007.

Setting England and Wales.

Data sources Prescribing data from the prescription statistics department of the Information Centre for Health and Social Care (England) and the Prescribing Services Unit, Health Solutions Wales (Wales). Mortality data from the Office for National Statistics.

Main outcome measures Prescriptions. Deaths from drug poisoning (suicides, open verdicts, accidental poisonings) involving single analgesics.

Results A steep reduction in prescribing of co-proxamol occurred in the post-intervention period 2005-7, such that number of prescriptions fell by an average of 859 (95% confidence interval 653 to 1065) thousand per quarter, equating to an overall decrease of about 59%. Prescribing of some other analgesics (co-codamol, paracetamol, co-dydramol, and codeine) increased significantly during this time. These changes were associated with a major reduction in deaths involving co-proxamol compared with the expected number of deaths (an estimated 295 fewer suicides and 349 fewer deaths including accidental poisonings), but no statistical evidence for an increase in deaths involving either other analgesics or other drugs.

Conclusions Major changes in prescribing after the announcement of the withdrawal of co-proxamol have had a marked beneficial effect on poisoning mortality involving this drug, with little evidence of substitution of suicide method related to increased prescribing of other analgesics.

Introduction

For many years concerns have been expressed about the extent of fatal poisoning with the analgesic co-proxamol (dextropropoxyphene in combination with paracetamol), especially its use for suicide.1 2 Death occurs largely because of the toxic effects of high levels of dextropropoxyphene on respiration and cardiac conduction.3 4 The margin between therapeutic and potentially lethal concentrations is relatively narrow.5 Between 1997 and 1999 co-proxamol was the single drug used most frequently for suicide in England and Wales (766 deaths over the three year period), implicated in nearly a fifth of all suicides from drug related poisoning.2 6

After the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency reviewed the efficacy and safety profile of co-proxamol, the Committee on Safety of Medicines (CSM) advised in January 2005 that co-proxamol should be withdrawn from use in the UK, the final date of withdrawal being 31 December 2007.7 8 The committee also advised that during the intervening period efforts should be made to move patients to suitable alternatives, although patients for whom this was difficult could continue to receive the drug through normal prescribing. This announcement had a major effect during the withdrawal phase on prescribing in England9 10 and in Scotland, where there was a beneficial effect on suicides during 2005-6.11

We evaluated the effect of the announcement of co-proxamol withdrawal on prescribing and mortality involving co-proxamol and other analgesics in England and Wales. We investigated deaths from drug poisoning that received a verdict of suicide or an open verdict, and also those with a verdict of accidental death, some of which may have been suicidal acts.12 Substitution of method is a potential concern where a common means used for suicide becomes less available.13 We therefore investigated the possible effect of the withdrawal of co-proxamol on the prescribing of other analgesics and on their use in suicide. Our method takes account of underlying trends in prescribing and deaths before the committee’s announcement.

Method

Prescriptions

We obtained data on prescriptions of co-proxamol and of co-codamol, codeine, co-dydramol, dihydrocodeine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol, and tramadol (the analgesics most likely to be used instead of co-proxamol) in England and Wales from the prescription statistics department of the Information Centre for Health and Social Care (England) and the Prescribing Services Unit of Health Solutions Wales (Wales), in the form of quarterly statistics for 1998 to 2007. We excluded preparations in the form of liquids, suppositories, granules, and powders, and also effervescent preparations, which are rarely used in poisoning. Prescription data for Wales were not available for the first quarter of 1998, and therefore we estimated values for this quarter with least squares methods.

Deaths

To evaluate the effect of the withdrawal of co-proxamol on suicide we used data on deaths that received a suicide verdict and those recorded as death of undetermined intent (open verdicts). In England and Wales, it has been customary to assume that most injuries and poisonings of undetermined intent are cases where the harm was self inflicted but there was insufficient evidence to prove that the deceased deliberately intended to kill themselves.14 15

Quarterly information on deaths from drug poisoning (suicides, open verdicts, and accidental poisonings) involving co-proxamol alone, co-codamol, codeine, co-dydramol, dihydrocodeine, NSAIDs, paracetamol, and tramadol was provided by the Office for National Statistics on the basis of death registrations during 1998-2007 in England and Wales. We restricted our analyses to deaths involving single drugs or single drugs and alcohol. Similar data were supplied for overall drug poisoning deaths receiving suicide, open, and accidental poisoning verdicts, and for all deaths receiving suicide and open verdicts.

In assessing whether there has been any substitution of other analgesics for co-proxamol among self poisoning deaths we have combined mortality data for all the other analgesics. We also examined trends in deaths from poisoning with all drugs (suicide, open, and accidental death verdicts) and deaths from all causes (suicide and open verdicts only).

Statistical analyses

We analysed trends in prescribing and deaths with Stata version 10.0.16 We used interrupted time series analysis to estimate changes in levels and trends in prescribing and deaths after the CSM announcement of the withdrawal of co-proxamol. This method controls for baseline level and trend when estimating expected changes in the number of prescriptions (or deaths) due to the intervention.17

Specifically, we used segmented regression analysis18 to estimate the mean quarterly number of prescriptions and deaths that might have occurred in the post-intervention period without the CSM announcement, and the number of prescriptions and deaths that occurred with the CSM announcement. The latter were obtained from best fitted data lines from the regressions, and are better estimates than taking the average of the actual values. The end of 2004 was chosen as the point of intervention. Thus our data comprised 28 quarters in the pre-intervention segment and 12 quarters in the post-intervention segment. Slope and level regression coefficients were used to estimate the average quarterly absolute differences (using the midpoint of the post-intervention period, midway between quarter 2 and quarter 3 of 2006).

Preliminary analyses indicated some autocorrelation in the data, therefore the Cochrane-Orcutt autoregression procedure was used (rather than ordinary linear regression) to correct for first order serially correlated errors. The Durbin Watson statistic of all final models was close to the preferred value of 2, indicating that no serious autocorrelation remained.

Results

Prescriptions

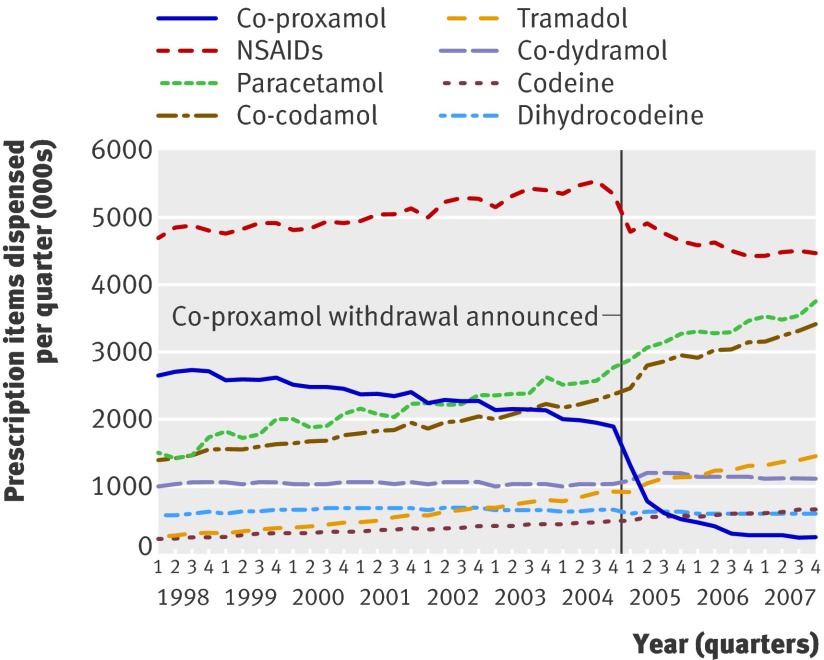

Prescription data for England and Wales showed a steep reduction in prescription of co-proxamol in the first two quarters of 2005, with further reductions thereafter (fig 1).

Fig 1 Prescriptions for analgesics dispensed in England and Wales, 1998-2007.

Regression analyses indicated a significant decrease in both level and slope in prescribing of co-proxamol (appendix table), such that the number of prescriptions decreased by an average of 859 (95% confidence interval [CI] 653 to 1065) thousand per quarter in the post-intervention period (table 1). This change equated to an overall decrease of about 59% in the three year post-intervention period, 2005 to 2007. We also noted significant decreases in prescribing NSAIDS of an average of 1053 (95% CI 920 to 1186) thousand per quarter, equating to an approximate 19% decrease overall for 2005 to 2007; and for dihydrocodeine of an average of 35 (95% CI 2 to 68) thousand per quarter, or approximately 6% overall for 2005 to 2007 (table 1).

Table 1.

Changes in prescriptions and deaths from poisoning involving co-proxamol, other analgesics, and all drugs, in England and Wales, 1998-2007, associated with the CSM announcement

| Estimation of absolute effect during 2005 to 2007 of the CSM announcement* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean quarterly estimated number without CSM announcement † | Mean quarterly estimated number with CSM announcement † | Mean quarterly change during 2005 to 2007 ‡ (95%CI) § | |

| Prescriptions (thousands) | |||

| Co-proxamol | 1465.1 | 605.7 | −859 (−1065 to −653) |

| Co-codamol | 2524.7 | 3024.6 | 500 (459 to 540) |

| Codeine | 534.6 | 578.0 | 43 (31 to 55) |

| Co-dydramol | 1018.2 | 1140.0 | 122 (99 to 145) |

| Dihydrocodeine | 634.6 | 600.0 | −35 (−68 to −2) |

| NSAIDs | 5633.8 | 4581.0 | −1053 (−1186 to −920) |

| Paracetamol | 2947.0 | 3330.0 | 382 (268 to 497) |

| Tramadol | 1130.1 | 1193.9 | 64 (−5 to 133) |

| Suicide, open | |||

| Co-proxamol | 39 | 15 | −24 (−37 to −12) |

| Other analgesics ¶ | 39 | 44 | 5 (−5 to 15) |

| All drugs except co-proxamol and other analgesics | 204 | 191 | −13 (−34 to 8) |

| All drugs | 283 | 252 | −31 (−66 to 3) |

| All causes | 1152 | 1130 | −22 (−89 to 45) |

| Suicide, open, accidental | |||

| Co-proxamol | 48 | 19 | −29 (−42 to −17) |

| Other analgesics | 56 | 60 | 4 (−11 to 18) |

| All drugs except co-proxamol and other analgesics | 348 | 385 | 37 (−8 to 82) |

| All drugs | 452 | 466 | 14 (−46 to 75) |

*Using interrupted time series segmented regression analysis18 where the intervention point is taken as the end of 2004 (the CSM announcement on the withdrawal of co-proxamol, January 2005).

†Estimated for the midpoint quarter of 2005 to 2007. See appendix for method, equation (2) or (3).

‡Absolute difference of estimated number with CSM announcement and estimated number without CSM announcement, taken at the midpoint of the post-intervention period, see appendix equation (4).

§95% confidence intervals (CI) taken from Stata results or calculated according to Zhang et al.26

¶Co-codamol, codeine, co-dydramol, dihydrocodeine, NSAIDS, paracetamol, and tramadol.

Prescriptions for the other analgesics, apart from tramadol, increased significantly in the post-intervention period (table 1). On the basis of mean quarterly estimates, percentage increases over the 2005 to 2007 period were approximately 20% for co-codamol, 13% for paracetamol, 12% for co-dydramol, and 8% for codeine.

Deaths

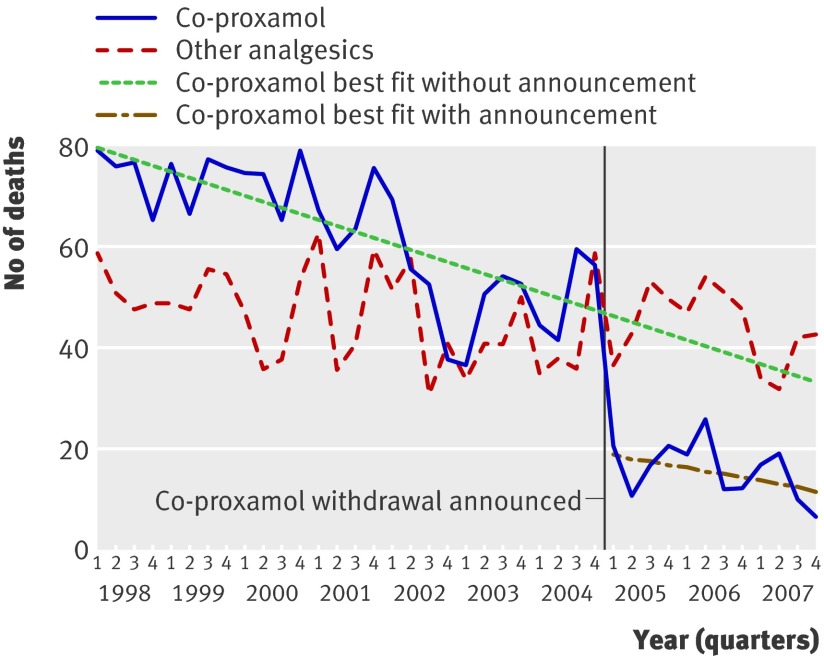

Mortality data for England and Wales showed a marked reduction in suicide and open verdicts involving co-proxamol in the first quarter of 2005, which persisted until the end of 2007 (fig 2 and table 2). Before 2005 deaths due to co-proxamol alone accounted for 19.5% (95% CI 16.9 to 22.2) of all suicides by drug poisoning, whereas between 2005 and 2007 they constituted just 6.4% (5.2 to 7.5; table 2).

Fig 2 Mortality in England and Wales from analgesic poisoning (suicide and open verdicts), 1998-2007, for people aged 10 years and over (substances taken alone, with or without alcohol)

Table 2.

Suicide and open verdict deaths by all causes, and suicide, open verdict, and accidental deaths due to poisoning by all drugs, co-proxamol alone, and other analgesics alone (or with alcohol) in England and Wales

| All causes | All drugs | Co-proxamol alone† | Other analgesics* alone† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide, open | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | ||||

| 1998 | 5347 | 1432 | 2250 | 298 (21) | 354 (16) | 207 (15) | 283 (13) | |||

| 1999 | 5241 | 1415 | 2298 | 298 (21) | 359 (16) | 208 (15) | 280 (12) | |||

| 2000 | 5081 | 1309 | 2147 | 296 (23) | 345 (16) | 175 (13) | 229 (11) | |||

| 2001 | 4904 | 1279 | 2181 | 268 (21) | 322 (15) | 200 (16) | 262 (12) | |||

| 2002 | 4762 | 1225 | 1984 | 217 (18) | 265 (13) | 182 (15) | 237 (12) | |||

| 2003 | 4811 | 1195 | 1844 | 196 (16) | 226 (12) | 166 (14) | 237 (13) | |||

| 2004 | 4883 | 1247 | 2007 | 204 (16 ) | 249 (12) | 168 (14) | 232 (12) | |||

| 2005 | 4718 | 1154 | 1927 | 70 (6) | 86 (5) | 183 (16) | 238 (12) | |||

| 2006 | 4513 | 979 | 1822 | 69 (7) | 83 (5) | 200 (20) | 287 (16) | |||

| 2007 | 4322 | 888 | 1852 | 53 (6) | 63 (3) | 151 (17) | 209 (11) | |||

*Co-codamol, codeine, co-dydramol, dihydrocodeine, NSAIDS, paracetamol, tramadol.

†Percentage of all drug poisoning deaths shown in brackets.

Regression analyses indicated a significant decrease in both level and slope for deaths involving co-proxamol which received a suicide or open verdict (appendix table), such that the number of deaths decreased by on average 24 (95% CI 12 to 37) per quarter in the post-intervention period (table 1). This equated to an estimated overall decrease of 295 (95% CI 251 to 338) deaths, approximately 62%, in the post-intervention period 2005 to 2007 compared with 1998 to 2004.

When deaths from accidental poisoning involving co-proxamol were included, there was a mean quarterly decrease of 29 (95% CI 17 to 42) deaths, which equated to an overall decrease of 349 (306 to 392) deaths, approximately 61%, in 2005 to 2007 (table 1).

There were no statistically significant changes in level or slope in the post-intervention period for deaths involving the other analgesics, for those that received a suicide or open verdict (mean quarterly change 5, 95% CI −5 to 15) and when accidental poisoning deaths were also included (mean quarterly change 4, −11 to 18).

There was a reduction during the post-intervention period in deaths (suicide and open verdicts) involving all drugs (including co-proxamol and other analgesics), with the mean quarterly change between 2005 and 2007 being −31 (95% CI −66 to 3) deaths, but this decrease did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (table 1). The mean quarterly change in the overall suicide rate (including open verdicts) was −22 (95% CI −89 to 45). The substantial rise in deaths involving all drugs in which a suicide, open or accidental verdict was reached (table 1) was largely due to an increase in accidental deaths from drug misuse.19

Discussion

The rationale for co-proxamol being withdrawn in the UK was that the efficacy and safety profile of the drug was disadvantageous,8 with co-proxamol being involved in a large number of deaths from suicide annually.2 Thus, this measure was primarily aimed at preventing suicides involving self poisoning with co-proxamol. The data we have presented show that after the announcement of the withdrawal of co-proxamol in January 2005 there was an immediate large reduction in prescriptions, which during the period 2005-7 amounted to 59% fewer prescriptions than expected on the basis of data for 1998-2004. This decrease was associated with a 62% reduction in deaths from suicide related to co-proxamol (including open verdicts), or an estimated 295 fewer deaths. Inclusion of accidental deaths, some of which were likely to have been suicides,12 increased the estimated reduction in number of deaths to 349 over three years. This level of effect was consistent with that found in Scotland during 2005-611 and with benefits found with prescribing restrictions in other countries in Europe.20 21 Some prescribing continued during the withdrawal phase because the CSM advice had allowed this.7 8

Possible substitution of suicide method must be considered in estimating the effect of changing availability of a specific method of suicide.13 22 Because withdrawal of co-proxamol was associated with changes in prescribing of other analgesics, an increase in use of other analgesics for suicide might be expected. Although prescribing of co-codamol, paracetamol, and co-dydramol increased during 2005-7, analyses of suicides and open verdict deaths involving other analgesics combined indicated little evidence of such substitution. This finding is in keeping with lower toxicity of most of these alternative drugs. Since poisoning deaths with co-proxamol also often involve other substances, but co-proxamol is usually the fatal agent,5 the overall number of deaths prevented by the CSM initiative was probably considerably greater than the figures we have reported, as we restricted our analysis to overdoses of single medicines.

An abrupt reduction in prescribing of NSAIDs occurred shortly before the announcement of the withdrawal of co-proxamol, because of concerns about COX 2 inhibitors.23 However, NSAIDs are rarely a direct acute cause of death, especially by suicide.24

Overall suicide and open verdict deaths decreased in England and Wales during 2005 to 2007 but the change was not statistically significant. Also the proportionate decline was much greater and statistically significant for co-proxamol. Thus underlying downward trends in suicide cannot account for the full extent of the decrease in co-proxamol related deaths.

The results of this study provide an example of how the actions of regulatory authorities based on risk assessment of drugs can have an important public health function, as has also been found for measures restricting pack sizes of analgesics sold over the counter.24

Strengths and limitations

We used national data to evaluate the effect of the announcement of withdrawal of co-proxamol on prescribing and deaths. We restricted the analyses to deaths involving single analgesics to eliminate the possible contribution of other drugs to the deaths. We also investigated possible substitution of method of suicide by examining prescribing and drug poisoning deaths involving other analgesics, and deaths receiving a coroner’s verdict of accidental poisoning, some of which may have been intentional.12 25 We did not examine possible substitution with entirely different methods of suicide. The mortality data we used were based on registrations rather than actual dates of deaths, which might have affected quarterly data but not the overall findings.

Our method of statistical analysis—interrupted time series autoregression—controls for baseline level and trend when estimating expected changes in the number of prescriptions (or deaths) due to the intervention, and is therefore preferable to simpler methods such as a change in proportions before and after the intervention which do not take long term baseline data into account. However, it should be noted that the estimates of the overall effect on prescriptions and mortality involved extrapolation, which is inevitably associated with uncertainty. Also the regression method assumes linear trends over time, and the co-proxamol prescribing data, in particular, had a poor fit, resulting in large standard errors in the post-intervention period. Estimates of the standard errors for absolute mean quarterly changes in number of prescriptions or deaths were determined exactly, including the covariance of level and slope terms. Estimates of percentage changes over the three year post-intervention period, however, are point estimates and were not determined with standard error calculations. Therefore caution must be advised in interpreting these percentages too literally.

Conclusions

The announcement of the withdrawal of co-proxamol in the UK has had a substantial effect on prescribing and on deaths from poisoning in England and Wales, particularly suicides. This evidence, along with a similar finding for Scotland,11 suggests that the UK initiative has been an effective measure.

What is already known on this topic

In early 2005 the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency announced gradual withdrawal of co-proxamol because of its adverse benefit to safety ratio, especially its use for intentional and accidental fatal poisoning.

Restriction of access to dangerous means for suicidal behaviour can reduce deaths from suicide.

What this study adds

During the three year withdrawal phase (2005-7) prescription of co-proxamol in England and Wales fell by 59%, with an increase in prescribing of some other analgesics.

The marked reduction in suicides and accidental poisonings involving co-proxamol during this period, with no evidence of an increase in deaths involving other analgesics, suggests that the initiative has been effective.

We thank Doug Altman of the Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, for statistical advice, and staff at the Information Centre for Health and Social Care (England) and Prescribing Services Unit, Health Solutions Wales, for providing prescription data.

Contributors: KH and SS had the idea for the study. KH, DG, and NK obtained funding. KH, HB, SS, AB, and CG designed the study. AB and ER extracted mortality data. KS provided expert statistical advice. HB conducted the statistical analysis. All authors participated in writing of the manuscript. KH is guarantor.

Funding: This work was funded by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research (RP-PG-0606-1247). The views and opinions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health/NIHR or NHS. The funders played no role in the analysis or write up of this paper. KH is also supported by Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust and HB by the Department of Health.

Competing interests: KH and SS presented evidence to the MHRA committee that evaluated co-proxamol.

Ethical approval: None required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b2270

References

- 1.Simkin S, Hawton K, Sutton L, Gunnell D, Bennewith O, Kapur N. Co-proxamol and suicide: a review to inform initiatives to prevent the continuing toll of overdose deaths. Q J Med 2005;98:159-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Co-proxamol and suicide: a study of national mortality statistics and local non-fatal self-poisonings. BMJ 2003;326:1006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Distalgesic and its equivalents: time for action. DTB 1983;21:17-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman DN, Afshari R. Licence needs to be changed. BMJ 2003;327:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawton K, Simkin S, Gunnell D, Sutton L, Bennewith O, Turnbull P, et al. A multicentre study of co-proxamol poisoning suicides based on coroners’ records in England. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;59:207-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning: England and Wales, 1993-2005. Health Statistics Q 2007;33:82-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Withdrawal of co-proxamol products and interim updated prescribing information CEM/CMO/2005/2. www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-a/documents/websiteresources/con019461.pdf.

- 8.Committee on Safety of Medicines. Withdrawal of co-proxamol (Distalgesic, Cosalgesic, Dolgesic). Curr Probl Pharmacovigilance 2006;31:11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Information Centre for Health and Social Care PSU. Prescription Cost Analysis: England 2005. Leeds: Department of Health, 2006.

- 10.The Information Centre for health and social care PSU. Prescription Cost Analysis: England 2006. Leeds: Department of Health, 2007.

- 11.Sandilands EA, Bateman DN. Co-proxamol withdrawal has reduced suicide from drugs in Scotland. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;66:290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Harriss L, Zahl D. Deaths from all causes in a long-term follow-up study of 11,583 deliberate self harm patients. Psychol Med 2006;36:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daigle MS. Suicide prevention through means restriction: assessing the risk of substitution: a critical review and synthesis. Accid Anal Prev 2005;37:625-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adelstein A, Mardon C. Suicides 1961-74. Popul Trends 1975;2:13-8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock A, Baker A, Griffiths C, Jackson G, Fegan G, Marshall D. Suicide trends and geographical variations in the United Kingdom, 1991-2004. Health Statistics Q 2006;31:6-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stata Corporation. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation, 2007.

- 17.Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:613-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office for National Statistics. Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales, 2003-07. Health Statistics Q 2008;39:82-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonasson U, Jonasson B. Restrictions on the prescribing of dextropropoxyphene (DXP)—effects on sales and cases of fatal poisoning. Report for the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine and Medical Products Agency. Last update 2004. www.rmv.se/pdf/dxp-report.pdf.

- 21.Segest E, Harris CN, Bay H. Dextropropoxyphene deaths in Denmark from the health authority point of view. Med Law 1993;12:141-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawton K. Restricting access to methods of suicide: Rationale and evaluation of this approach to suicide prevention. Crisis 2007;28(suppl 1):4-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb S. Warnings issued over COX 2 inhibitors in US and UK. BMJ 2005; 330: 9.

- 24.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J, Cooper J, Johnston A, Waters K, et al. UK legislation on analgesic packs: before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ 2004;329:1076-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkle BS. Self-poisoning with dextropropoxyphene and dextropropoxyphene compounds: the USA experience. Human Toxicol 1984;3:115-34S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang F, Wagner A, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Estimating confidence intervals around relative changes in outcomes in segmented regression analyses of time series data. 15th Annual NESUG (NorthEast SAS Users Group Inc) Conference. Last update 2002. www.nesug.info/Proceedings/nesug02/st/st005.pdf.