Summary

The etiology of patellofemoral pain is likely related to pathological femoral shape and soft-tissue restraints imbalance. These factors may result in various maltracking patterns in patients with patellofemoral pain. Thus, we hypothesized that femoral shape influences patellofemoral kinematics, but that this influence differs between kinematically-unique subgroups of patients with patellofemoral pain. 3D MRIs of 30 knees with patellofemoral pain and maltracking (“maltrackers”) and 33 knees of asymptomatic subjects were evaluated retrospectively. Dynamic MRI was acquired during a flexion-extension task. Maltrackers were divided into two subgroups (non-lateral and lateral maltrackers) based on previously defined kinematic criteria. Nine measures of femoral trochlear shape and two measures of patellar shape were quantified. These measures were correlated with patellofemoral kinematics. Differences were found in femoral shape between the maltracking and asymptomatic cohorts. Femoral shape was correlated with patellofemoral kinematics, but the kinematic parameters that demonstrated significant correlation varied across maltracking subgroups. Femoral shape parameters were associated with patellar kinematics in patients with patellofemoral pain and maltracking, but the correlations were unique across subgroups within this population. The ability to better categorize patients with patellofemoral pain will likely improve treatment by providing a more specific etiology of maltracking in individual patients.

Keywords: Patellofemoral pain, femur, kinematics, MRI

Introduction

Patellofemoral (PF) pain syndrome is one of the most common problems of the knee1–6, constituting 25% of all injuries presenting to a sports injury clinic7 and affecting 15% of military recruits undergoing basic infantry training8. It is characterized by anterior knee pain that is aggravated by deep flexion, prolonged sitting and repetitive flexion/extension6. Muscle force imbalance9,10, altered passive constraints9,10, static PF malalignment11–18, dynamic PF maltracking19–23, and pathological femoral shape24 are thought to be related to PF pain. Yet, the mechanism by which these factors lead to pain is not well understood, complicating treatment.

One of the difficulties in determining the source of PF pain is that the numerous potential causes are inter-related. For example, PF malalignment and maltracking result from imbalanced forces acting on the patella25; such an imbalance may partially arise from pathological femoral shape. Trochlear dysplasia (a sulcus angle > 150° 26 or a lateral trochlear inclination angle (LTI) < 11° 1) can lead to recurrent patellar dislocation1,3,5,27,28. Yet, few studies have examined how PF shape may be altered in patients with PF pain without recurrent dislocation12,24,29. One study30 explored the relationship between femoral shape and PF kinematics (“tracking”) in a combined population of patients with PF pain and asymptomatic volunteers. The sulcus angle was a predictor of 2D PF kinematics, but the potentially unique correlations within each population (patients with PF pain and asymptomatic volunteers) were not identified. A more recent study22 revealed kinematically distinct subgroups (non-lateral and lateral maltrackers) within a patient population with PF pain and maltracking. The distinct maltracking patterns may indicate a different reliance on the femoral sulcus for guiding PF movement between these subgroups.

Thus, our primary objective was to quantify femoral and patellar shape in the context of 3D PF kinematics of asymptomatic subjects and patients with PF pain and maltracking (“maltrackers”) to test three hypotheses: 1) femoral and patellar shape parameters are different between these cohorts; 2) these same parameters differ between kinematically-unique subgroups within the maltrackers; and 3) the influence of femoral shape on PF kinematics differs between kinematically-unique subgroups of maltrackers. Support of these hypotheses would define how femoral shape influences PF kinematics, providing clinical guidance in treatment selection.

Methods

This retrospective study used data from two separate cohorts. The first included 30 knees of patients diagnosed with PF pain and suspected maltracking (“maltrackers”, Table 1). To be included in this cohort, each knee had to be clinically diagnosed with PF pain (symptoms present for ≥ 1 yr) without any of the following: prior surgery (including arthroscopy); ligament, meniscus, iliotibial band, or cartilage damage; other lower leg pathology or injury; or traumatic onset of PF pain syndrome. Also, each knee had to exhibit one or more of the following: Q-angle ≥15°; a positive apprehension test; patellar lateral hypermobility ≥ 10 mm; or a positive J-sign9. The second cohort consisted of 33 knees (Table 1) from an asymptomatic control population (with no history of lower leg pathology, surgery, or major injury) recruited from the general population. All participants gave informed consent upon entering this IRB-approved study.

Table 1. Demographics & Clinical Intake Parameters.

The majority of the control cohort data were collected prior to the patellar maltracking cohort data; thus, clinical intake parameters were unavailable for the control cohort. Only lateral hypermobility was significantly different between the lateral and non-lateral maltracking cohorts.

| Parameter | Controls | Maltrackers | Non-Lateral | Lateral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 24.9 | 5.1 | 27.6 | 10.8 | 27.9 | 10.0 | 27.4 | 11.7 |

| Height (cm) | 171.4 | 10.7 | 168.0 | 6.9 | 166.2 | 6.5 | 169.3 | 7.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.0 | 18.3 | 62.5 | 12.7 | 58.8 | 7.7 | 65.4 | 15.1 |

| Gender | 16F & 17M | 26F & 4M | 12F & 1M | 14F & 3M | ||||

| Kujula Score (out of 100) | 74.2 | 11.4 | 72.1 | 13.0 | 75.7 | 10.3 | ||

| Visual Analog Pain Scale (out of 100) | 36.8 | 27.0 | 35.1 | 26.5 | 38.1 | 28.2 | ||

| Q-angle (deg) | 16.2 | 3.5 | 17.0 | 2.0 | 15.5 | 3.7 | ||

| Lateral hypermobility | 8.7 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 10.9 | 5.3 | ||

| J-sign (present) | 15 | ----- | 5 | ----- | 10 | ----- | ||

| Length of pain (years) | 3.1 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 2.7 | ||

For all subjects, two sets of MR images were acquired: a high resolution 3D sagittal Gradient Recalled Echo Image series with resolution that varied from 0.547 mm × 0.547 mm × 1.0 mm to 1.172 mm × 1.172 mm × 1.5 mm; and a full dynamic image set, containing a sagittal-oblique fast-PC MR image series (x,y,z velocity and anatomic images over 24 time frames) and an axial fastcard image series (anatomic images only). All dynamic images were acquired while subjects extended/flexed their knee from maximum flexion to full extension and back31.

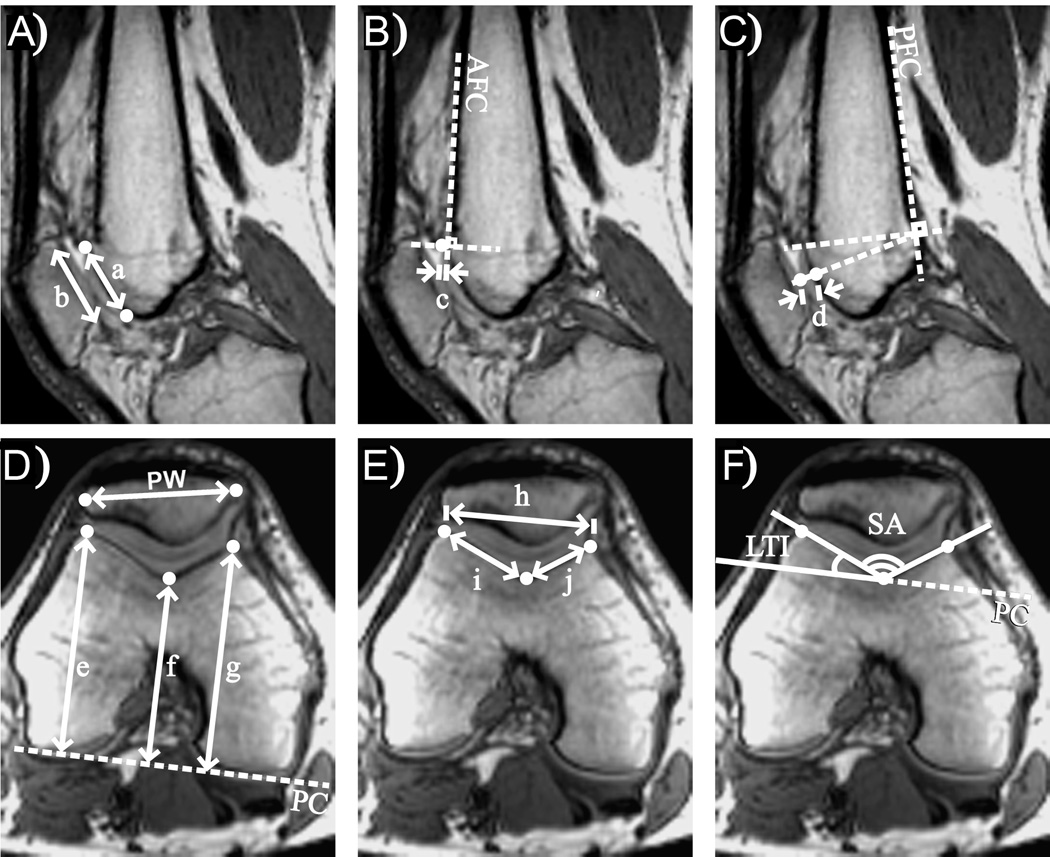

Seven measures of femoral trochlear geometry (Fig.1: lateral trochlear inclination (LTI)1, sulcus angle12,32,33, articular cartilage depth (ACD)3, sulcus groove length, trochlear bump3, trochlear groove width5, and trochlear depth5) and two measures of patellar geometry (patellar height (PH) and width) were quantified from the 3D static images using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). From these measurements, two ratios describing trochlear geometry (facet and condyle asymmetry5) and one describing the relationship between trochlear groove width and patellar width (TPR) were calculated. All measures were scaled by the ratio of the average epicondylar width across the asymptomatic cohort (76.9 mm) to each subject’s epicondylar width.

Figure 1. A-C) Sagittal Reference Plane.

A) Sulcus groove length (a) is the linear distance between the most superior and most inferior points in the sulcus groove (white dots). Patellar height (b), measured in the patellar sagittal reference plane, is the longest length of the patella along the posterior edge. B) Trochlear bump (c) is the perpendicular distance from the superior tip of the articular cartilage (white dot) to the tangent to the distal anterior femoral cortex (AFC). C) Articular cartilage depth (d) is measured along a vector 15° below the line perpendicular to the distal posterior femoral cortex (PFC) and intersecting the edge of the posterior condyles. D-F) Axial Femoral Reference Plane. D) Height of the medial condyle, sulcus groove, and lateral condyle are distances e, f, and g, respectively, each measured as the perpendicular distance from the most anterior point of the bony landmark (white dots) to the tangent to the posterior condyles (PC). Trochlear depth is [(e + g) / 2] – f. Condyle asymmetry is e / g. Patellar width (PW: measured in the patellar reference plane, but shown in the femoral reference plane for brevity), is the distance between the most medial and most lateral points on the patella. E) Trochlear groove width (h) is the distance between the anterior points of the lateral and medial trochlear condyles (outer white dots). The ratio between trochlear groove width and patellar width (TPR) is PW/h. The center dot represents the most distal point of the sulcus groove. Facet asymmetry of the trochlear groove is defined as i / j. F) Lateral trochlear inclination (LTI) is the angle between the tangent to the lateral trochlear edge and PC. Sulcus angle (SA) is defined by the angle between the lines tangent to the medial and lateral trochlear edges.

Before performing femoral shape measures, each 3D static sagittal image set was rotated to standardize the analysis coordinate system across subjects and decrease inherent variability in measurements due to initial offsets in limb positioning (MIPAV, NIH)33,34. In the rotated image set, the femoral-sagittal reference plane was defined as the image plane containing the deepest point of the sulcus groove. Sulcus groove length, trochlear bump, and ACD were quantified in this plane. The patellar-sagittal reference plane was defined as the image plane containing the tallest patellar section. Patellar height was quantified in this image plane. The rotated 3D sagittal image set was then re-sliced to create an axial image set. The femoral-axial reference plane was defined as the axial image plane containing the epicondylar line (Fig. 1). LTI, sulcus angle, trochlear depth, trochlear groove width, facet asymmetry, and condyle asymmetry were quantified in this plane. The patellar-axial reference plane was defined as the axial image plane containing the widest portion of the patella. Patellar width was quantified in this plane.

PF kinematics were obtained for each subject through integration of the fast-PC MRI velocity data31. This technique has excellent accuracy (<0.5mm35) and precision (<1.2° 31) for measuring PF kinematics. Displacement was defined in 3D (lateral-medial, inferior-superior, and posterior-anterior), as was orientation (flexion-extension, lateral-medial tilt, and valgus-varus rotation)22. A significant increase in the superior location of the patella relative to the femur was defined as patella alta. Although, this is not the typical measure of patella alta (e.g., the Insall-Salvati ratio, which defines a relationship between the patella and tibia during quiet standing36), the method may be more physiologically relevant because the kinematic relationship between the patella and the femoral sulcus is quantified during volitional exercise with quadriceps activity. The kinematics were quantified from ~45° knee flexion to full extension, but for clarity we focused on two descriptors of this range, the value and slope of each kinematic variable. The value of each variable was defined by its magnitude at 10° of extension, consistent with a previous study22. At this angle, the knee was in terminal extension (where patellar maltracking is typically most evident). Nearly all subjects reached this angle, so minimal data loss occurred. The slope of each kinematic variable was defined by the linear best fit with knee angle.

The maltracking cohort was divided into two subgroups based on the lateral-medial displacement of the patella, using a previously defined criterion22. Symptomatic knees with displacement medial to the asymptomatic average (≥ −0.45 mm) and with a lateral-medial displacement slope ≤ 0.25 mm/° were defined as “non-lateral maltrackers” (n = 13). All others were defined as “lateral maltrackers” (n = 17).

A Student’s t-test (2-tailed, unequal variances) was used to compare demographics and shape parameters between the asymptomatic and maltracking cohorts. This was followed by a one-way ANOVA with group (asymptomatic, non-lateral maltrackers and lateral maltrackers) as the main effect factor. If a difference was detected between groups, a pairwise Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was performed to determine which group-pair demonstrated this difference. For shape parameters demonstrating significance between groups, correlations were sought with the value of each kinematic variable. A correlation ≥ 0.5 was considered clinically relevant. If a set of shape parameters co-varied (Pearson’s r coefficient), then the correlations were reported for a single variable from that set. Due to the higher percentage of males in the control population (Table 1), a Student’s t-test was used to compare shape parameters and kinematics between males and females in the asymptomatic population. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

Previous studies showed that the mean LTI is about 20° (SD: 5°) in asymptomatic subjects1,24. Therefore, assuming a minimum detectable difference of 4.0° (20% of the asymptomatic mean) and choosing a common standard deviation of 5°, a preliminary power analysis estimated that two cohorts (asymptomatic volunteers and patients with PF pain) of 26 subjects each would be needed to yield a power of 80% (effect size: 0.8).

Results

No significant differences were found in demographics between the cohorts (asymptomatic controls and all maltrackers) or between the maltracking subgroups (lateral and non-lateral maltrackers). The one exception was the significantly larger percentage of females in the maltracking cohort compared to the asymptomatic cohort (Table 1). In comparing asymptomatic males to asymptomatic females, no differences in kinematics (matching previously published results31) or PF shape parameters were found.

Three shape parameters were significantly different in the maltracking cohort compared to the asymptomatic cohort (Table 2). ACD, sulcus groove length, and PH were smaller in the maltracking cohort by 25.7% (p<0.001), 8.0% (p=.031), and 7.1% (p=.020), respectively.

Table 2. Femoral Shape Parameters.

Each row provides the mean and standard deviation (SD) for each shape variable in each cohort (control and maltrackers) and each maltracking subgroup (non-lateral and lateral).

| Parameter | Controls | Maltrackers | Non-Lateral | Lateral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Lateral trochlear inclination (°) | 25.78N | 5.18 | 27.34 | 6.22 | 30.83C,L | 5.34 | 24.68N | 5.59 |

| Sulcus angle (°) | 126.98 | 8.82 | 126.87 | 8.63 | 121.60L | 7.22 | 130.90N | 7.48 |

| Articular cartilage depth (mm) | 3.08L,N,M | 0.85 | 3.87C | 0.79 | 4.07C | 0.63 | 3.72C | 0.89 |

| Sulcus groove length (mm) | 28.98M | 3.50 | 31.28C | 4.61 | 30.56 | 4.23 | 31.83 | 4.93 |

| Trochlear depth (mm) | 7.74 | 1.67 | 7.85 | 1.50 | 8.76L | 1.20 | 7.15N | 1.34 |

| Patellar height (mm) | 25.59N,M | 2.30 | 27.41C | 2.21 | 27.69C | 2.67 | 27.20 | 1.85 |

| Trochlear bump (mm) | 2.26 | 1.25 | 2.43 | 1.83 | 2.23 | 1.24 | 2.58 | 2.20 |

| Trochlear groove width (mm) | 32.47 | 3.88 | 32.53 | 3.03 | 32.16 | 2.99 | 32.81 | 3.12 |

| Patellar width (mm) | 41.71 | 3.10 | 42.14 | 2.38 | 42.62 | 2.47 | 41.78 | 2.31 |

| Condyle asymmetry | 1.04 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.03 |

| Facet asymmetry | 1.46 | 0.37 | 1.37 | 0.30 | 1.26 | 0.23 | 1.45 | 0.32 |

| TPR | 1.30 | 0.20 | 1.31 | 0.14 | 1.34 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.11 |

Superscript letter indicates a significant difference for that cohort or subgroup compared to another (C = controls, M = all maltrackers, L = lateral maltrackers, N = non-lateral maltrackers). Light grey shading indicates no significant differences were found between any cohort or any subgroup.

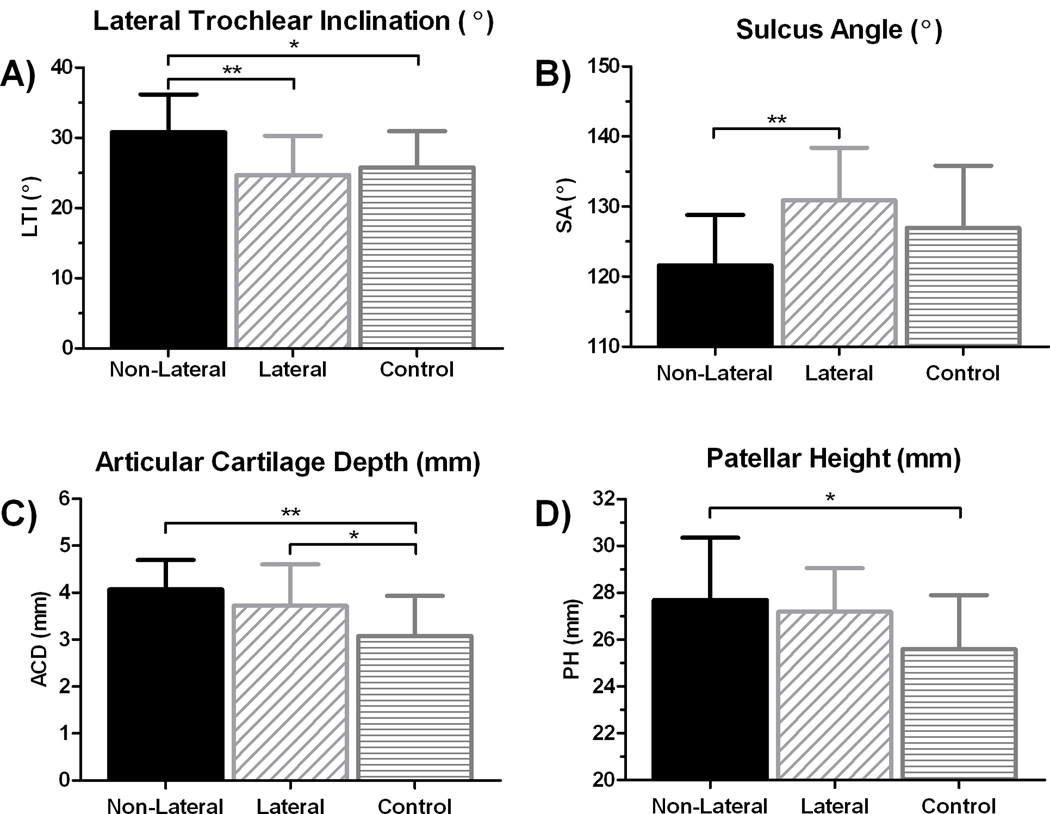

Three femoral shape parameters (LTI, sulcus angle, and trochlear depth) were different between the maltracking subgroups (Table 2 and Fig. 2). LTI was 20.0% (p=0.008) and 11.3% (p=0.016) greater in non-lateral maltrackers compared to lateral maltrackers and asymptomatic subjects, respectively. Sulcus angle and trochlear depth were 7.1% (p=0.009) and 22.5% (p=0.015) larger in the lateral compared to the non-lateral maltrackers, respectively. Patellar height was not different between the maltracking subgroups, but it was 7.6% greater in non-lateral maltrackers compared to the asymptomatic cohort (p=0.020).

Figure 2. Femoral shape parameters with significant differences between the three cohorts.

Mean (+SD) is shown for non-lateral maltrackers, lateral maltrackers, and controls for (A) lateral trochlear inclination (LTI), (B) sulcus angle (SA), (C) articular cartilage depth (ACD), and (D) patellar height. One star (*) and two stars (**) indicate significant differences between groups at p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively.

The measures of trochlear dysplasia (trochlear bump, trochlear groove width, facet asymmetry, and condyle asymmetry), patellar width, and TPR were not different between the two cohorts or between the two maltracking subgroups. Strong co-variance was documented between LTI and both sulcus angle (r=−0.82) and trochlear depth (r=0.76), but not between LTI and either ACD (r = 0.08) or PH (r = 0.05). PH weakly co-varied with ACD (r=0.45).

The non-lateral maltracking subgroup differed from the asymptomatic population in a single kinematic variable only: increased PF flexion (4.0°). The lateral maltrackers followed a more “classic” pattern of maltracking: increased lateral (4.3mm) and superior (6.7mm) displacement along with increased flexion (4.2°), lateral tilt (5.7°), and valgus (1.7°). Out of all the kinematic variables, flexion and superior displacement were the most consistently different between the maltracking subgroups and the control population. Only two non-lateral and two lateral maltrackers were more extended than the asymptomatic average and only two lateral and four non-lateral maltrackers were inferior to the asymptomatic average.

Correlations between femoral shape and PF kinematics existed for both cohorts. LTI and PF lateral tilt were moderately correlated for the asymptomatic cohort (r = 0.61). The maltrackers demonstrated correlations between LTI and superior displacement (r = −0.69), medial displacement (r = 0.48), and medial tilt (r = 0.57). LTI was inversely correlated with patellar superior displacement (r = −0.70) for lateral maltrackers. In contrast, LTI and PF lateral tilt were moderately correlated for the non-lateral maltrackers (r = 0.55). In addition, PH was moderately correlated with patellar superior displacement (r = 0.56) and extension (r = −0.68) for the non-lateral maltracking subgroup. Correlations for sulcus angle, trochlear depth, and ACD co-varied with other shape measures and therefore, were not considered independent measures.

Discussion

Our results define differences in femoral shape between populations, and can be used to explain potential sources of maltracking by correlations of femoral shape with PF kinematics. The association between shape and kinematics was different for the lateral and non-lateral maltracking subgroups, indicating a different reliance on the femoral sulcus for restricting patellar motion at or near full extension. In addition, the two maltracking subgroups often demonstrate average femoral shape values that are on opposite sides of the asymptomatic average (e.g., LTI, sulcus angle, and trochlear depth). Thus, when the maltracking population as a whole is compared to the asymptomatic population, these differences are masked.

Our study is unique in demonstrating an increase in LTI for a subgroup of maltrackers (non-lateral). Although previous studies demonstrated decreased LTI (trochlear dysplasia) in patients with PF pain1,3,5,27,28, the increase in LTI found in our study is supported by earlier in vitro work that simulated dysplasia and trochleoplasty (resulting in increased LTI) in cadaver knees37. By changing the LTI in cadaver knees, Amis and colleagues found that trochlear dysplasia resulted in an increase (from control) of about 5 mm in lateral displacement, whereas trochleoplasty resulted in a decrease (~2.5 mm at 10° knee extension). Similarly, the non-lateral maltracking subgroup demonstrated a 6.2° increase in LTI along with a 6.2 mm decrease in lateral PF displacement22 compared to lateral maltrackers.

The lack of significant differences between the asymptomatic and maltracking cohorts for the majority of the femoral shape parameters is not surprising as most of the maltrackers did not have gross patellar instability. Only four lateral maltrackers had a history of two or more dislocations; all other maltrackers had no history of dislocation. Trochlear bump, trochlear groove width, condyle asymmetry, and facet asymmetry are all measures of femoral dysplasia5, which has a higher prevalence in patients with PF pain and recurrent dislocation1,3. Significant differences were found in ACD, but the difference between populations was within the range of measurement accuracy and thus, was potentially not clinically relevant.

The correlations between femoral shape and PF kinematics are supported by a previous 2D study30. In our study, the distinct associations between shape and kinematics for each maltracking subgroup indicate that the two subgroups relied on the femoral sulcus differently for restricting patellar motion at or near full extension. For lateral maltrackers, femoral shape was not a controlling factor for PF kinematics in terminal extension. This is likely due to the patella alta identified in this subgroup, which removes the patella from the sulcus groove early in terminal extension, allowing soft tissue forces to dominate PF kinematics. Interestingly, the inverse correlation between LTI and the PF superior displacement in this maltracking subgroup potentially arose from the influence of kinematics on femoral shape. Specifically, in the presence of patella alta, the proximal femoral sulcus experiences less mechanical stress due to patellar disengagement. Lowered stress on the bone fosters remodeling, which results in a lower LTI37. Following this line of reasoning, the superior location of the patella explains 49% (r2) of the variation in LTI. Thus, patella alta increases the likelihood of dislocation12,27,38 by both removing the patella from the constraints of the femoral sulcus and by fostering femoral dysplasia.

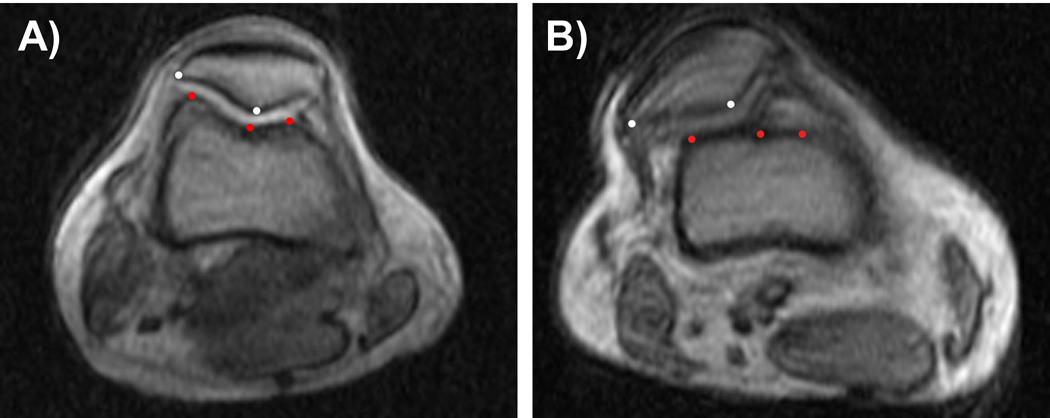

For the non-lateral maltracking subgroup, the femoral sulcus only partially controlled PF kinematics in that 30% (r2) of the variability in patellar tilt could be explained by LTI. This is likely due to the lack of patella alta and the larger patellar height, allowing the patella to remain engaged with the femoral groove further into terminal extension. Although no correlation was found between LTI and lateral-medial displacement, the increased LTI and the more medially displaced patella in the non-lateral maltrackers likely indicates that LTI influenced this kinematic variable, but not in a linear fashion. Specifically, in the presence of soft-tissue imbalance, the lateral edge of the patella is engaged with the lateral trochlea. Thus, further lateral translation can only occur if the patella rides up the lateral trochlea, resulting in a coupled anterolateral translation. The increased patellar flexion in non-lateral maltrackers increases posterior pressure on the patella. This pressure resists anterior movement, preventing the patella from riding up the lateral trochlea. Thus, a prominent lateral trochlea (large LTI) provides the non-lateral maltrackers an osseous constraint, which prevents lateral patellar translation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Mid-patellar axial image during volitional knee extension with active quadriceps contraction.

(A) Non-lateral Maltracker. The combination of a longer patella, normative superior patellar location, and a high LTI in the non-lateral maltrackers enables the patella to remain partially engaged with the femoral trochlea in terminal extension. The large lateral edge resists lateral patellar translation, leading to a more centralized tracking pattern. (B) Lateral Maltracker. Due to the patella alta and the lower value of LTI, the patella is not engaged with the femoral trochlea in terminal extension. The lack of osseous constraints and the presence of soft tissue imbalance allow the patella to track laterally.

The primary limitation of this study was its retrospective nature. The 3D static images were not collected for the specific purpose of measuring femoral bone shape. Thus, the image resolution varied among subjects. As many of the shape parameters demonstrated no significant differences between cohorts, power was investigated post-hoc. Only a single parameter (trochlear bump) was significantly underpowered to detect a difference of 1.0 mm (power < 70%). Due to the increased incidence of PF pain syndrome in females, sex is an important consideration. When controlling for sex as a covariate, group significance was maintained for all comparisons with the single exception of PH. No significant interaction between group and sex was detected for all PF bone shape and kinematic variables. Further analysis of PH with multiple regression techniques suggested that while sex may influence PH, this influence was not strong enough to confound the original group comparisons. Therefore, based on multiple statistical analyses, the difference in sex representation between the cohorts does not confound our results.

Ongoing debate persists on the benefits of measuring kinematics during weight-bearing tasks. Powers and colleagues demonstrated that maltracking patterns were more pronounced at or near full extension under non-axial loading conditions with high quadriceps activity (compared to a partial weight-bearing condition) similar to the current paradigm39. In agreement, the single study to quantify PF kinematics during full weight-bearing failed to identify maltracking patterns near full extension, but did identify such patterns at deep flexion (>60° of flexion) or the portion of the movement requiring the highest quadriceps load20. Additionally, a recent cadaver study demonstrated that increased quadriceps load led to increased lateral patellar tilt and shift40. In total, these results highlight the fact that loading of the patellofemoral joint occurs primarily through quadriceps contraction, not axial loading. Therefore, quantifying knee joint kinematics associated with PF pain during dynamic movements requiring quadriceps activity is key to identify maltracking patterns,19 and weight-bearing is likely not the primary factor. Thus, the fact that our data were acquired in a non weight-bearing condition is not a limitation, particularly since the critical elements of movement and quadriceps activities are incorporated within the experimental paradigm.

In conclusion, femoral shape is generally not the primary controlling factor in PF kinematics for patients with PF pain. Importantly, the relationship between femoral shape and PF kinematics varies based on the type of maltracking present. Thus, any treatment or surgical intervention aimed at correcting PF maltracking10 should account for both the differences in femoral shape and the relationships between femoral shape and PF kinematics. For example, a change in bone shape would unlikely alter PF kinematics in a lateral maltracker with patella alta, but shortening the patellar tendon would increase patellar engagement with the trochlear groove during terminal extension, and therefore likely improve maltracking. In addition, our study has identified measurements that can be taken on standard clinical MRIs (e.g., LTI and patellar height) which suggest, but do not definitively predict, membership in PF pain subgroups. The differences in femoral shape between the maltracking subgroups may support the development of a clinical tool to predict kinematic maltracking patterns associated with PF pain, without the need for dynamic imaging, since such patterns could not be predicted from classic clinical measures alone22. This would likely improve treatment by providing a more specific etiology of maltracking. Data collection is continuing in order to support tool development.

Table 3. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients (r) for Lateral Trochlear Inclination Angle (LTI) and Patellar Height (PH) with Patellofemoral Kinematics.

Medial, superior, anterior, flexion, medial tilt and varus indicate the positive directions of motion.

| Cohort | Parameter | Displacement | Rotation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | Superior | Anterior | Flexion | Medial Tilt | Varus | ||

| Control | LTI | 0.35* | −0.25 | 0.20 | −0.17 | 0.61** | 0.21 |

| All Maltrackers | LTI | 0.48* | −0.69** | −0.17 | −0.10 | 0.57** | 0.01 |

| Non-Lateral | LTI | 0.13 | −0.32 | −0.46 | −0.33 | 0.55* | 0.11 |

| Lateral | LTI | 0.26 | −0.70* | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.42 | −0.17 |

| Control | PH | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.16 | −0.14 |

| All Maltrackers | PH | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.46* | 0.05 | 0.31 |

| Non-Lateral | PH | 0.00 | 0.56* | 0.09 | −0.69* | 0.11 | 0.48 |

| Lateral | PH | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.21 | −0.13 | 0.07 |

p≤0.05

p<0.001

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth K. Rasch, PT, PhD, Ching-yi Shieh, PhD, and Pei-Shu Ho, PhD for support on the statistical analysis. We also thank Abrahm Behnam, Jacqueline Feenster, Bonnie Damaska and the Diagnostic Radiology Department at the National Institutes of Health for their support and research time. Salary support for all authors was provided through the National Institutes of Health for all authors. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, (CC and NICHD).

References

- 1.Carrillon Y, Abidi H, Dejour D, et al. Patellar instability: assessment on MR images by measuring the lateral trochlear inclination-initial experience. Radiology. 2000;216:582–585. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.2.r00au07582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutbill JW, Ladly KO, Bray RC, et al. Anterior knee pain: a review. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1997;7:40–45. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dejour H, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Guier C. Factors of patellar instability: an anatomic radiographic study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 1994;2:19–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01552649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muhle C, Brossmann J, Heller M. Kinematic CT and MR imaging of the patellofemoral joint. European Radiology. 1999;9:508–518. doi: 10.1007/s003300050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfirrmann CW, Zanetti M, Romero J, Hodler J. Femoral trochlear dysplasia: MR findings. Radiology. 2000;216:858–864. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se38858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson T. The measurement of patellar alignment in patellofemoral pain syndrome: are we confusing assumptions with evidence? Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 2007;37:330–341. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereaux MD, Parr GR, Lachmann SM, et al. Thermographic diagnosis in athletes with patellofemoral arthralgia. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Br] 1986;68:42–44. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B1.3941140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milgrom C, Finestone A, Eldad A, Shlamkovitch N. Patellofemoral pain caused by overactivity. A prospective study of risk factors in infantry recruits. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Am] 1991;73:1041–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amis AA. Current concepts on anatomy and biomechanics of patellar stability. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2007;15:48–56. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318053eb74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feller JA, Amis AA, Andrish JT, et al. Surgical biomechanics of the patellofemoral joint. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:542–553. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grelsamer RP, Weinstein CH, Gould J, Dubey A. Patellar tilt: The physical examination correlates with MR imaging. Knee. 2008;15:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aglietti P, Insall JN, Cerulli G. Patellar pain and incongruence. I: Measurements of incongruence. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 1983;176:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi T, Fujikawa K, Nemoto K, et al. Evaluation of patello-femoral alignment using MRI. Knee. 2005;12:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurin CA, Dussault R, Levesque HP. The tangential x-ray investigation of the patellofemoral joint: x-ray technique, diagnostic criteria and their interpretation. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 1979;144:16–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacIntyre NJ, Hill NA, Fellows RA, et al. Patellofemoral joint kinematics in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Am] 2006;88:2596–2605. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laprade J, Culham E. Radiographic measures in subjects who are asymptomatic and subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 2003:172–182. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000079269.91782.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merchant AC, Mercer RL, Jacobsen RH, Cool CR. Roentgenographic analysis of patellofemoral congruence. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Am] 1974;56:1391–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schutzer SF, Ramsby GR, Fulkerson JP. Computed tomographic classification of patellofemoral pain patients. The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1986;17:235–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brossmann J, Muhle C, Schroder C, et al. Patellar tracking patterns during active and passive knee extension: evaluation with motion-triggered cine MR imaging. Radiology. 1993;187:205–212. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.1.8451415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson NA, Press JM, Koh JL, et al. In Vivo Noninvasive Evaluation of Abnormal Patellar Tracking During Squatting in Patients with Patellofemoral Pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:558–566. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanford W, Phelan J, Kathol MH, et al. Patellofemoral joint motion: evaluation by ultrafast computed tomography. Skeletal Radiology. 1988;17:487–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00364042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan FT, Derasari A, Fine KM, et al. Q-angle and J-sign: Indicative of Maltracking Subgroups in Patellofemoral Pain. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0880-0. [ePub ahead of Print]: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan FT, Derasari A, Brindle TJ, Alter KE. Understanding patellofemoral pain with maltracking in the presence of joint laxity: complete 3D in vivo patellofemoral and tibiofemoral kinematics. Journal of Orthopeadic Research. 2009;27:561–570. doi: 10.1002/jor.20783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keser S, Savranlar A, Bayar A, et al. Is there a relationship between anterior knee pain and femoral trochlear dysplasia? Assessment of lateral trochlear inclination by magnetic resonance imaging. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2008;16:911–915. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elias DA, White LM. Imaging of patellofemoral disorders. Clinical Radiology. 2004;59:543–557. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tecklenburg K, Dejour D, Hoser C, Fink C. Bony and cartilaginous anatomy of the patellofemoral joint. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2006;14:235–240. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dandy DJ. Chronic patellofemoral instability. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Br] 1996;78:328–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hing CB, Shepstone L, Marshall T, Donell ST. A laterally positioned concave trochlear groove prevents patellar dislocation. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 2006;447:187–194. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203478.27044.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray TF, Dupont JY, Fulkerson JP. Axial and lateral radiographs in evaluating patellofemoral malalignment. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1999;27:580–584. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powers CM. Patellar kinematics, part II: the influence of the depth of the trochlear groove in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Physical Therapy. 2000;80:965–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seisler A, Sheehan FT. Normative three-dimensional patellofemoral and tibiofemoral kinematics: a dynamic,in vivo study. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2007;54:1333–1341. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.890735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalichman L, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, et al. The association between patella alignment and knee pain and function: an MRI study in persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2007;15:1235–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shih YF, Bull AM, Amis AA. The cartilaginous and osseous geometry of the femoral trochlear groove. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2004;12:300–306. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibanuma N, Sheehan FT, Lipsky PE, Stanhope SJ. Sensitivity of femoral orientation estimates to condylar surface and MR image plane location. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2004;20:300–305. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheehan FT, Zajac FE, Drace JE. Using cine phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging to non-invasively study in vivo knee dynamics. J Biomech. 1998;31:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grelsamer RP, Meadows S. The modified Insall-Salvati ratio for assessment of patellar height. Clinical Orthopeadics & Related Research. 1992;282:170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amis AA, Oguz C, Bull AM, et al. The effect of trochleoplasty on patellar stability and kinematics: A biomechanical study in vitro. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [Br] 2008;90:864–869. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escala JS, Mellado JM, Olona M, et al. Objective patellar instability: MR-based quantitative assessment of potentially associated anatomical features. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:264–272. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0668-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powers CM, Ward SR, Fredericson M, et al. Patellofemoral kinematics during weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing knee extension in persons with lateral subluxation of the patella: a preliminary study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:677–685. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.11.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goudakos IG, Konig C, Schottle PB, et al. Stair climbing results in more challenging patellofemoral contact mechanics and kinematics than walking at early knee flexion under physiological-like quadriceps loading. Journal of Biomechanics. 2009;42:2590–2596. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]