Abstract

Whether renal outcomes differ between the segmental and global subclasses of diffuse proliferative (class IV) lupus nephritis is unknown. In this meta-analysis, we searched the literature in MEDLINE, EMBASE, five registries of clinical trials, and selected cohort studies and randomized, controlled trials that used the 2003 International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society classification of lupus nephritis in adult patients. Our endpoint was the composite of doubling of serum creatinine concentration or ESRD. In the eight studies included in the final analysis, the incidence of this endpoint varied between 0% and 67%. A funnel plot and Egger's test did not suggest significant heterogeneity. The meta-analysis did not support a significant difference in renal outcome between the segmental (IV-S) and global (IV-G) subclasses (relative risk for class IV-G versus IV-S, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.68–1.70). Meta-regression did not suggest that ethnicity or duration of follow-up influenced the association between histologic class and renal risk. In conclusion, the rate of doubling of serum creatinine concentration or of ESRD did not differ between patients with class IV-S and those with IV-G lupus nephritis.

Renal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus is highly variable, as reflected by the broad spectrum of histologic abnormalities found at renal biopsy.1,2 Different histologic classifications of lupus nephritis (LN) have been used over the past several decades.3,4 The correlation of certain patterns of glomerular injury with clinical manifestations and prognosis led to the proposal of a new classification by the International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) in 2003.5 The proposed changes sought to improve interobserver agreement and reproducibility and to eliminate the ambiguities seen with prior classifications.6 Important changes in the new classification of LN are the elimination of both normal renal biopsy findings and the subcategories of class V. Furthermore, sclerotic glomeruli are now included in the assessment of the number of affected glomeruli. The most remarkable change in the new classification is probably the subdivision of class IV. Diffuse endocapillary or extracapillary glomerulonephritis involving 50% of all glomeruli or more (defined as class IV) is divided into two subcategories: segmental and global. Diffuse segmental proliferative LN (IV-S) is defined as at least 50% of the involved glomeruli having lesions involving less than half of the glomerular tuft. Diffuse global LN (class IV-G) is diagnosed when the lesions affect more than 50% of the glomerular tuft. Both subcategories are also scored for active and chronic lesions.5

This new classification of class IV LN is based on a study of 86 consecutive cases of LN that suggested a difference in outcome between segmental vasculitis-like lesions and more global lesions with wire loops. Renal survival rates at 10 years were 52% for patients (n=24) with focal segmental glomerulonephritis involving 50% or more of all glomeruli and 75% in 35 patients with diffuse proliferative lesions (P<0.05).7 Similarly, the risk for progression to ESRD was 2.9 times higher in the group with focal segmental lesions. The two groups also differed morphologically. Subendothelial deposits were seen frequently in diffuse proliferative lesions, whereas the focal segmental lesions showed a relative absence of such subendothelial immune aggregates. This finding might indicate a distinct immunopathogenesis that could require other therapeutic protocols; such a distinction would impede merger of the two categories into one class in the new LN classification.7

After the introduction of the ISN/RPS classification, comparisons between LN classes IV-S and IV-G were published. Markowitz and D’Agati6 summarized the first three studies on the outcome of these class IV subcategories. The studies were performed in relatively small groups of patients who did not always receive similar therapies. Although the two subclasses showed distinct clinical and morphologic features at baseline, outcome did not significantly differ.8–10 Of note, on repeat biopsies, shifts from IV-S to IV-G and vice versa occurred in two studies,8,9 a finding that might suggest a similar pathogenesis with various disease stages or morphologic expressions.6

Although the first reports on the outcome of LN class IV-S and IV-G did not significantly differ, some trends toward a better outcome of IV-S9 or IV-G10 have been reported. Furthermore, a short-term follow-up study found a better response to cyclophosphamide induction treatment in LN class IV-S than in IV-G.11 Because the conclusions of various studies are contradictory, our current study aims to analyze the existing evidence on the differences in renal outcome of the two subclasses of class IV LN.

Results

Studies Included

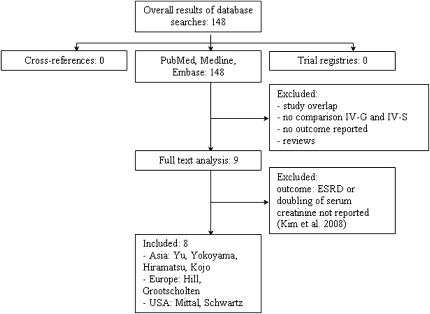

A flow chart of the results obtained with the search of MEDLINE and EMBASE is depicted in Figure 1. No ongoing trials were identified by reviewing the trial registries. A manual review of the reference lists of full-text articles did not yield any additional studies.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the inclusion of studies. Abstracts were screened for use of the 2003 ISN/RPS classification. Reasons for exclusion are presented.

Nine studies fulfilled the study inclusion and quality criteria.8–16 One study done by Kim et al.11 was excluded from analysis because it reported renal flares as an outcome and did not provide data on the doubling of serum creatinine concentration or ESRD. Characteristics of the remaining eight studies are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Renal outcomes per study

| Authors | Publication Year | Class IV-S | Class IV-G | Immunosuppressive Therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Death | No Renal Death | Follow-up (yr) | Renal Death | No Renal Death | Follow-up (yr) | |||||

| Mittal et al.8 | 2004 | 3 | 8 | 3.2 | 2 | 20 | 4.6 | Steroids; steroids and CP/MMF/AZA/MTX/plasmapheresis | ||

| Yokoyama et al.10 | 2004 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 7 | None; steroids; steroids + CP/AZA/CsA/mizoribine | ||

| Hill et al.9 | 2005 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 10 | Steroids; steroids + CP | ||

| Grootscholten et al.13 | 2008 | 0 | 15 | 6.5 | 5 | 52 | 6.3 | Steroids + AZA; steroids + CP followed by steroids + AZA | ||

| Hiramatsu et al.14 | 2008 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 4 | 37 | 5 | Steroids; steroids + CP/AZA/CsA/other | ||

| Schwartz et al.12 | 2008 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 16 | 45 | 6 | Steroids + CP; steroids + CP (+ plasmapheresis) | ||

| Kojo et al.16 | 2009 | 0 | 20 | 12.5 | 1 | 44 | 12.5 | Steroids; steroids + CP/CsA/tacrolimus/AZA/mizoribine | ||

| Yu et al.15 | 2009 | 1 | 19 | 5 | 27 | 125 | 5 | Steroids + CP followed by CP/AZA/MMF/leflunomide | ||

AZA, azathioprine; CP, cyclophosphamide; CsA, cyclosporin A; MMF, mofetil mycophenolate; MTX, methotrexate.

Outcome

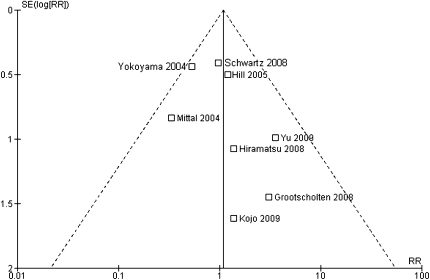

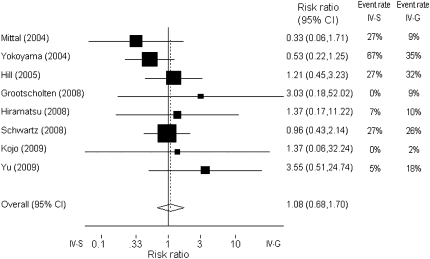

The occurrence of the combined end point (doubling of serum creatinine concentration or ESRD) varied considerably between the studies, with rates ranging from 0% to 67%. As can be determined from Table 1 and Figure 2, the smaller studies (by Mittal et al. and Yokoyama et al.) showed a better outcome for class IV-G. The study by Yokoyama et al. showed considerably higher event rates in both groups than did other studies.10 To evaluate a publication bias, we constructed a funnel plot (Figure 2). There appeared to be less studies in the bottom-left of the funnel. Neither Egger's test (P=0.30) nor the Mantel-Haenzel chi-squared test (P=0.45) nor I2 statistics (I2=0%) provided statistical evidence of funnel plot asymmetry. However, in the face of the relatively few studies included in the analysis, we cannot exclude that small, negative observational studies are not reported. Another cause for an asymmetry could be heterogeneity between the various studies. Therefore, we evaluated potential heterogeneity with meta-regression, first on ethnicity and then on duration of follow-up. Neither had significant effects on the association between histological class and outcome. Studies performed in Asia showed a nonsignificant slightly lower relative risk for renal death, RR=0.94 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.18–4.8) P=0.44, and I2=0%. Each additional year of follow-up was associated with a nonsignificant increase in relative risk for renal death of 3% (RR=1.03 [95% CI: 0.78–1.35], P=0.88, and I2=0%). Finally, a forest plot was constructed with the Mantel-Haenzel method to obtain an overall relative risk of renal death for class IV-S versus IV-G (Figure 3). The relative risk of renal death was 1.08 (95% CI: 0.68–1.70) for IV-G.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for the effect of histologic class on the risk for renal death. A risk ratio >1 suggests a higher risk for renal death in class IV-G.

Figure 3.

Forest plot (fixed effects) of the estimated effect of histologic class IV on the risk for renal death. The box size is related to study weights, which were calculated with the Mantel–Haenzel method. A risk ratio >1 suggests a higher risk with class IV-G, and a risk ratio less than 1 suggests a higher risk with class IV-S. The test for heterogeneity was not significant (P=0.45). A forest plot allowing for random effects (using the DerSimonian and Laird method) yielded similar results.

Discussion

The ISN/RPS classification, published in 2004, divided class IV into two subcategories: class IV-S and IV-G. We performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the existing evidence for differences in renal outcome between the two subclasses of class IV LN. The occurrence of renal death (i.e., doubling of serum creatinine concentration or ESRD) did not significantly differ between the two groups of patients.

Several limitations of our study should be mentioned. Only a small number of studies could be included. However, the selected trials have passed an extensive evaluation of study quality. Publication bias was addressed by a search of multiple publication and clinical trial registration databases. Despite a negative result on a test for heterogeneity, it is possible that small negative (observational) studies were not published because fewer studies appear in the bottom-left part of the funnel plot. We believe that this would not affect our conclusion that renal outcome between the two subclasses of class IV LN are not different. If more negative studies were included, it would only have strengthened our conclusion.

Sources of possible heterogeneity that we considered were duration of follow up, therapy, and geographic distribution of the studies. However, data on therapy in individual patients were not available. The lack of these data hampered interpretation of the considerable variation in progression to the combined end point between the studies. One retrospective study evaluating the differences between IV-S and IV-G in response to cyclophosphamide induction treatment has been published.11 Patients with class IV-G LN showed a significantly lower rate of complete remission after 6 months and a significantly greater decline in GFR after a follow-up of 5 years. However, the response to standard treatment should be interpreted cautiously because it depends on both glomerular structure and baseline clinical measures. Various authors stated some clinical differences between IV-S and IV-G at the time of the first biopsy.8,9,13,15 Patients with LN classified as IV-G tend to have higher blood pressure, higher serum creatinine concentrations, more severe proteinuria, a higher level of anti–double-stranded DNA, and lower levels of C3 and C4 at baseline than do patients with class IV-S LN. However, these differences did not always reach statistical significance. The study populations differed with regard to ethnicity, but there were no indications of significant heterogeneity.

Hill et al.9 attributed the differences between the outcomes of their study and those in the study of Najafi et al.7 to differences in the extent of chronic lesions. Mean National Institutes of Health chronicity index scores (±SD) were 3.8±2.6 in the study of Najafi and colleagues and 1.7±1.2 in the study of Hill and colleagues. In the study by Hiramatsu et al.,14 only patients with chronic lesions showed a decline in renal function after therapy. To address the effect of chronicity in the various studies, we evaluated the proportion of biopsy specimens categorized as showing active/chronic disease or the chronicity index score in individual studies (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were reported between IV-S and IV-G.

Table 2.

Reported measures of chronicity: percentage of biopsy specimens categorized as active/chronic or chronicity index score

| Author | IV-S | IV-G | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active/Chronic (%) | CI Score | Active/Chronic (%) | CI Score | ||

| Mittal et al.8 | 2 (0–8a | 4 (0–9a | 0.13 | ||

| Yokoyama et al.10 | 83 | 2.0±?b | 88 | 3.3±?b | 0.76 |

| Grootscholten et al.13 | 2.3 (1.7–3.3)c | 2.7 (2.0–3.7)c | 0.36 | ||

| Hiramatsu et al.14 | 29 | 49 | 0.19 | ||

| Yu et al.15 | 20 | 2.90±0.97d | 28 | 3.29±2.03d | 0.90 |

CI, chronicity index.

aMedian (minimum–maximum values).

bMean (SD not given).

cMedian (interquartile range).

dMean ± SD.

The criteria for the subclasses of class IV are involvement of more (IV-G) or less (IV-S) than 50% of the glomerular tuft. These definitions might cause misclassifications of the two subclasses because they are sensitive to sampling error: glomerular involvement is heterogeneous, and sample sizes are often small.12 In the study of Hill and colleagues,9 specimens were divided into “pure” and “mixed” subsets to refine the differences between class IV-G and IV-S; biopsy specimens with 80% of glomeruli or greater showing global proliferative lesions were classified as pure class IV-G. Pure class IV-S was defined similarly. Clinical and morphologic differences between the two subcategories became more accentuated in the pure subsets, but there were still no significant differences in renal relapse rate or renal survival at 10 years. Furthermore, the Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group published a study in 2008 questioning whether World Health Organization (WHO) class III involving 50% or more of the glomerular tuft, as published by Najafi et al.,7 is truly comparable to ISN/RPS class IV-S.12 Twenty-two biopsy specimens initially classified by the authors as WHO class III involving more than 50% of the glomerular tuft appeared to shift to class IV-G when the ISN/RPS classification was used. Thus, comparisons between studies using different classifications of LN should be interpreted with caution.17

Finally, one could argue that less immune suppression would have revealed differences in renal outcome between IV-S and IV-G. To answer this question, a randomized controlled trial is necessary, which is not available. So whether the immune complex proliferative lesions can be treated with less immune suppression than the segmental necrotizing lesions remains unknown at present. Therefore, analysis of histology remains intriguing for delineating pathophysiology and clinical disease course. Three recent studies indicate that the new classification seems to improve interobserver agreement, one of the goals set by the ISN/RPS. Furness et al.18 distributed renal biopsy specimens from patients with LN to 92 pathologists, who classified them by using the 1995 WHO classification. After 1 year, the specimens were reevaluated by using the ISN/RPS classification; reevaluation showed a significantly higher interobserver reproducibility (κ = 0.53 versus 0.44; P=0.002).18 These two classifications were also applied on renal biopsy specimens from a group of 60 Japanese patients. A higher consensus was reached with the ISN/RPS classification (98% versus 83%; P=0.008), but note that only two pathologists judged the specimens.10 Revision of renal biopsy specimen assessment by specialized nephropathologists reached low intraclass correlation coefficients for both the ISN/RPS 2003 and the WHO 1995 classifications: 0.181 and 0.108, respectively.13 Exclusion of several subclasses of the ISN/RPS 2003 classification led to an increase of the intraclass correlation coefficient to 0.405. The authors questioned whether further subclassification of LN is meaningful, given the lack of difference in outcome of class IV-G and IV-S LN and the low interobserver agreement in a classification that includes many subclasses.

In conclusion, the division of class IV LN into two subcategories in the 2003 ISN/RPS classification was based on a pilot study observing a difference in renal outcome between segmental and global lesions in diffuse proliferative LN. In our current meta-analysis, we found that, despite some clinical and morphologic differences, the renal outcome of class IV-S and IV-G LN did not differ.

Consise Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategy

One of the reviewers (A.R.) searched MEDLINE via PubMed (1990 through February 2010) and EMBASE (1980 through February 2010) by using the OVID search engine, with a language restriction (English, French, Dutch, and German). Five trial registries were screened to include ongoing trials: ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com), Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.actr.org.au), Clinical Trials Registry India (www.ctri.in), and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org) (as of April 2010).

The following keywords and subject terms were used in the searches: “lupus nephritis,” “classification,” “class IV-S,” and “class IV-G.”

The titles and abstracts resulting from the search were screened. Studies that probably included relevant data or information on trials were retained initially. Then, we selected cohort studies or randomized, controlled trials that used the 2003 ISN/RPS histologic classification criteria in patients 18 years of age or older who met four American College of Rheumatology criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.19 Study endpoints had to include doubling of serum creatinine concentration; ESRD, which was defined as the initiation of dialysis therapy or transplantation, all-cause mortality, or proteinuria at the end of follow-up.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted data from the selected trials by using a standard form. This form included the criteria applied to the biopsy specimens (minimal number of glomeruli), duration of follow-up, baseline characteristics (age, sex, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, disease duration, serum creatinine concentration, proteinuria, anti–double-stranded DNA, and C3 and C4 levels), treatment regimen, and study outcome (ESRD, doubling of serum creatinine concentration, renal flare, serum creatinine concentration at last follow-up, proteinuria at last follow-up, and all-cause mortality). For comparative purposes a composite endpoint was used: renal death comprising doubling of serum creatinine concentration or ESRD.

Quality Analysis

Study quality was evaluated individually by two investigators (C.H. and A.R.) without blinding to authorship or journal. A standardized checklist adapted from Altman20 and the Cochrane handbook21 was used. This included an assessment of the description of the sample, the criteria for inclusion and evaluation of biopsy specimens, the duration of follow-up, outcome, prognostic variables, appropriate execution of analysis, adequate allocation, and description of treatment regimens. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus with the other authors.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and RevMan, version 5.0 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

A forest plot was constructed to obtain overall relative risk for the composite endpoint of renal death for class IV-S versus IV-G; we used a fixed-effects model computed with the Mantel–Haenszel method. A second model using the DerSimonian and Laird method was performed to determine whether allowing for random effects substantially influenced results. Heterogeneity was evaluated with a funnel plot and Egger's test. Finally, a meta-regression was conducted to evaluate the potential confounding effect of ethnicity and duration of total follow-up on the association between histologic class and outcome.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berden JH: Lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 52: 538–558, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin HA, 3rd, Boumpas DT, Vaughan EM, Balow JE: Predicting renal outcomes in severe lupus nephritis: contributions of clinical and histologic data. Kidney Int 45: 544–550, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churg J, Sobin L: Renal Disease: Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Disease, Tokyo, Igaku-Shoin, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock RJ: Renal Disease: Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Disease, 2nd Ed., Tokyo, Igaku-Shoin, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M: The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 241–250, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz GS, D’Agati VD: The ISN/RPS 2003 classification of lupus nephritis: an assessment at 3 years. Kidney Int 71: 491–495, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najafi CC, Korbet SM, Lewis EJ, Schwartz MM, Reichlin M, Evans J. Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group: Significance of histologic patterns of glomerular injury upon long-term prognosis in severe lupus glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 59: 2156–2163, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal B, Hurwitz S, Rennke H, Singh AK: New subcategories of class IV lupus nephritis: are there clinical, histologic, and outcome differences? Am J Kidney Dis 44: 1050–1059, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, Bariéty J: Class IV-S versus class IV-G lupus nephritis: clinical and morphologic differences suggesting different pathogenesis. Kidney Int 68: 2288–2297, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama H, Wada T, Hara A, Yamahana J, Nakaya I, Kobayashi M, Kitagawa K, Kokubo S, Iwata Y, Yoshimoto K, Shimizu K, Sakai N, Furuichi K. Kanazawa Study Group for Renal Diseases and Hypertension: The outcome and a new ISN/RPS 2003 classification of lupus nephritis in Japanese. Kidney Int 66: 2382–2388, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YG, Kim HW, Cho YM, Oh JS, Nah SS, Lee CK, Yoo B: The difference between lupus nephritis class IV-G and IV-S in Koreans: focus on the response to cyclophosphamide induction treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 311–314, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz MM, Korbet SM, Lewis EJ; Collaborative Study Group: The prognosis and pathogenesis of severe lupus glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1298–1306, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grootscholten C, Bajema IM, Florquin S, Steenbergen EJ, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Goldschmeding R, Bijl M, Hagen EC, van Houwelingen HC, Derksen RH, Berden JH: Interobserver agreement of scoring of histopathological characteristics and classification of lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 223–230, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiramatsu N, Kuroiwa T, Ikeuchi H, Maeshima A, Kaneko Y, Hiromura K, Ueki K, Nojima Y: Revised classification of lupus nephritis is valuable in predicting renal outcome with an indication of the proportion of glomeruli affected by chronic lesions. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 702–707, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu F, Tan Y, Wu LH, Zhu SN, Liu G, Zhao MH: Class IV-G and IV-S lupus nephritis in Chinese patients: a large cohort study from a single center. Lupus 18: 1073–1081, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojo S, Sada KE, Kobayashi M, Maruyama M, Maeshima Y, Sugiyama H, Makino H: Clinical usefulness of a prognostic score in histological analysis of renal biopsy in patients with lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol 36: 2218–2223, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markowitz GS, D’Agati VD: Classification of lupus nephritis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 220–225, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furness PN, Taub N: Interobserver reproducibility and application of the ISN/RPS classification of lupus nephritis-a UK-wide study. Am J Surg Pathol 30: 1030–1035, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ: The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 25: 1271–1277, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altman DG: Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ 323: 224–228, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPTGS: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, London, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009 [Google Scholar]