Abstract

Objective: To examine the factors that could influence the decision of healthcare professionals to use a telemonitoring system. Materials and Methods: A questionnaire, based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), was developed. A panel of experts in technology assessment evaluated the face and content validity of the instrument. Two hundred and thirty-four questionnaires were distributed among nurses and doctors of the cardiology, pulmonology, and internal medicine departments of a tertiary hospital. Cronbach alpha was calculated to measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire items. Construct validity was evaluated using interitem correlation analysis. Logistic regression analysis was performed to test the theoretical model. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. Results: A response rate of 39.7% was achieved. With the exception of one theoretical construct (Habit) that corresponds to behaviors that become automatized, Cronbach alpha values were acceptably high for the remaining constructs. Theoretical variables were well correlated with each other and with the dependent variable. The original TAM was good at predicting telemonitoring usage intention, Perceived Usefulness being the only significant predictor (OR: 5.28, 95% CI: 2.12–13.11). The model was still significant and more powerful when the other theoretical variables were added. However, the only significant predictor in the modified model was Facilitators (OR: 4.96, 95% CI: 1.59–15.55). Conclusion: The TAM is a good predictive model of healthcare professionals' intention to use telemonitoring. However, the perception of facilitators is the most important variable to consider for increasing doctors' and nurses' intention to use the new technology.

Key words: home health monitoring, telemedicine, telehealth

Introduction

Telemonitoring is defined as “the use of audio, video, and other telecommunications and electronic information processing technologies to monitor patient status at a distance.”1 Telemonitoring systems allow the capture of patients' clinical parameters (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen saturation, blood glucose, electrocardiograph, and respiratory rate) by appropriate devices in a continuous or intermittent pace.2 Although the process of data measurement and collection can be totally automated, the patients themselves are often in charge of transferring self-measured clinical data. Such information can then be transmitted either to primary care professionals or to a specialized care center where the received parameters can be integrated with other relevant information related to the state of the patient.2 When the measurements fall outside the established limits, the telemonitoring system can react automatically, triggering alerts to the responsible healthcare professional and allowing a timely response to deterioration.2 Telemonitoring systems can be utilized in various contexts, such as the patient's home, scenes of medical emergencies, ambulance services, and hospitals.2

A systematic review showed that data transmitted through telemonitoring systems demonstrated a high level of accuracy and reliability.3 Further, the processes of data transfer of various telemonitoring systems have proven to be effective, and limited technical problems and errors were detected.3 With respect to patients' attitudes and behaviors, these novel management approaches have generally been well received and accepted.3 From an economic viewpoint, studies have reported that home telemonitoring of high-risk pregnant women4 and patients suffering from heart failure5 or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)6 induced significant healthcare cost reductions.

Home telemonitoring of patients with diabetes was associated with a significant improvement in glycemic control.7,8 Studies conducted among patients with hypertension have proven the importance of this approach for the control of the disease.9,10 With respect to home telemonitoring of patients suffering from asthma, significant improvements in patients' peak expiratory flows, considerable reductions in symptoms related to the disease, and improvements in perceived quality of life were observed.7 According to recent systematic reviews, telemonitoring interventions for patients with heart failure have been shown to be efficient in reducing the risk of all-cause mortality, heart failure–related hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and improving patient self-care, perceived quality of life, and evidence-based prescribing.11–14 Finally, home telemonitoring has also been found to reduce rates of hospitalization and emergency department visits for COPD patients.11,15,16

Two previous studies evaluated healthcare professionals' adoption of a telemonitoring system. First, in a study conducted in the United Kingdom, Sharma and colleagues17 investigated clinical users' perspectives on telemonitoring of patients with chronic conditions using the concepts of Giddens's Structuration Theory and Consequence of modernity.18,19 Three focus group discussions were undertaken among nurses and their supporting technical staff who were providing care to patients participating in a randomized controlled trial of telemonitoring for the management of chronic diseases. Following thematic analysis of qualitative data collected during the focus groups, trust (reliability of transmitted data, correct use of equipment by patients, and dependence on technical staff) and sense of security (lack of control and fears about changes in work routines) emerged as the two concepts that determined clinical users' adoption of telemonitoring. Authors conclude that if not acknowledged, these feelings may lead to divergences in groups' interests and misunderstanding of system objectives.

In a study conducted in Quebec (Canada), Vincent et al.20,21 evaluated nonphysician health professionals' adoption of elder home care telemonitoring using Triandis' Theory of Interpersonal Behavior.22 The study was conducted to understand the difference in community health workers' adoption of this technology that was observed in two participating sites. A qualitative research design was used to analyze data from focus groups and administrative documents related to training sessions of health professionals, patient registration, and activity reports. Habits and perceived barriers in clinical practice were identified as the main determinants of community health workers' adoption of elder home care telemonitoring.

Providers' acceptance is an important determinant of successful telehealth program implementation.23 The aim of this study was thus to evaluate the acceptance of a new telemonitoring system by healthcare professionals and to identify the main factors that could affect healthcare professionals' intention to use telemonitoring technology.

Materials and Methods

Context of the Study

The present study was carried out in the context of a home telemonitoring clinical trial conducted in the Basque Country (Spain). A home telemonitoring system was set up at the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) Department of Donostia University Hospital (Gipuzkoa). The hospital belongs to the Basque Health Service (Osakidetza) and serves a catchment population of 700,000 people. A randomized controlled open clinical trial was designed to evaluate the impact of a home telemonitoring intervention and a multifaceted personalized intervention on a sample of 37 patients with heart failure and/or COPD (Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN62033748). The study was approved by the Local Medical Ethics Board (CEIC Gipuzkoa). The clinical trial lasted from July 2008 to December 2009. The control group received a previously tested multifaceted personalized intervention that consisted of an individualized medication program in conjunction with a personalized and closely monitored aerobic physical activity schedule. An appointed nurse phoned the patients every fortnight. Additionally, patients in the control group could contact the medical team through a telephone line and an e-mail address accessible 24 h a day. For the intervention group, telemonitoring consisted of patient self-measurements of respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, weight, and body temperature twice a day in addition to the multifaceted personalized intervention. Besides the clinical measurements, patients in the intervention group completed a qualitative symptom questionnaire daily using the telemonitoring system. The measurements were sent by Global System for Mobile Communication (GSM) to the EBM department. Health services use (hospital admissions and emergency department visits), patient's quality of life, and cost of the interventions were assessed.

Theoretical Framework

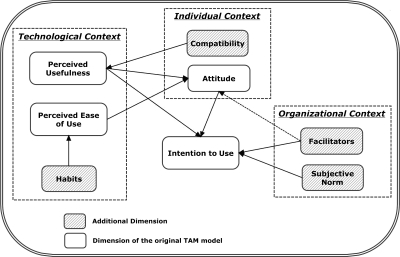

The proposed theoretical framework is adapted from Chau and Hu's model of telemedicine acceptance and comprises three dimensions: the individual context, the technological context, and the organizational context.24 The individual context encompasses the variables Attitude, which can be defined as the perception by an individual of the positive or negative consequences related to adopting the technology, and Compatibility, which refers to the degree of correspondence between an innovation and existing values, past experiences and needs of potential adopters.25 Compatibility was added to the model following previous research on telemedicine adoption.24 The second dimension of the model, the technological context, includes the variables Perceived Ease-of-Use (PEU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) proposed by Davis,26 as well as habit. Habit was proposed by Triandis in his Theory of Interpersonal Behavior (TIB) and refers to behavior that has become automatized.22 As regards the organizational context, the variables Subjective Norm and Facilitators are added in our theoretical model. Subjective Norm originates from the Theory of Reasoned Action26,27 and assesses the extent to which an individual believes that people who are important to him or her will approve his or her adopting of a particular behavior. The variable Facilitators (or facilitating conditions) originates from the TIB22 and refers to the degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support the use of the system. The adapted theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model.

Data Collection

Data were collected by means of a technology acceptance questionnaire that was developed following an adaptation of the original TAM to our particular case study. The questionnaire was tested among healthcare professionals of the cardiology, pulmonology, and internal medicine departments of a tertiary hospital. The face and content validity of the instrument were evaluated by a panel of experts in technology assessment. The internal consistency of the instrument was assessed by calculating the Cronbach alpha values for each theoretical variable. The construct validity of the model was evaluated using interitem correlation analysis. With the exception of Habit, Cronbach alpha values were acceptably high (≥0.7) for the remaining theoretical constructs (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Items Used for Measuring Theoretical Dimensions

| DIMENSION | ITEMS USED TO MEASURE THE DIMENSION | SAMPLE ITEM | CRONBACH α |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 2, 7, 11, 15, 21, and 27 | The use of TMS could help me to monitor my patients more rapidly | 0.94 |

| PEU | 3, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 30 | I think that I could easily learn how to use TMS | 0.80 |

| Attitude | 4, 17, 23, and 31 | I think it is a good idea to use TMS to monitor my patients | 0.89 |

| Compatibility | 6, 13, 22, and 29 | The use of TMS may imply major changes in my clinical practice | 0.72 |

| Subjective Norm | 9, 14, 20, and 26 | Most of my patients will welcome the fact that I use TMS | 0.72 |

| Facilitators | 10, 25, and 32 | I think that my center has the necessary infrastructure to support my use of TMS | 0.79 |

| Habit | 1, 19, and 33 | I feel comfortable with information and communication technologies | 0.56 |

| Intention | 5, 18, and 28 | I have the intention to use TMS when it becomes available in my center | 0.89 |

PU, Perceived Usefulness; PEU, Perceived Ease-of-Use; TMS, telemonitoring systems.

Overall, 155 paper-based questionnaires were sent to the nursing staff and 79 Web-based questionnaires were sent to the doctors (n=71) and nursing supervisors (N=8) via e-mail. The study questionnaire (see Supplementary Data; available online at www.liebertonline.com/tmj) is composed of 33 items that are divided into eight theoretical dimensions (see Table 1). The same questionnaire was used for nurses and doctors. However, we sent Web-based questionnaires to doctors and nursing supervisors because they have a professional e-mail address but the nursing staff does not.

Respondents answered the questionnaire by rating each item on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree.” Scores were developed by computing the mean of all the items that constitute each theoretical dimension. Additionally, respondents had to provide information about their age, gender, medical specialty, number of years in clinical practice, and the highest educational grade obtained. Finally, respondents could choose obtaining a certificate attesting of their collaboration in the present research project.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted descriptive statistics to examine the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the scores of the theoretical variables. We also computed and examined the correlations between the theoretical variables. Since the dependent variable (intention to use) is not normally distributed, a logistic regression analysis was carried out. The dependent variable was dichotomized by choosing the median as the cutoff point. The values for this variable were “low-to-moderate intention=0” and “high intention=1.” In other words, the respondents having a mean score for intention to use higher than 5.34 were categorized as high intenders and those with a mean score for intention to use lower than or equal to 5.34 were categorized as low-to-moderate intenders.

We conducted a logistic regression with blocking of variables. The first block comprised the TAM variables, namely PU and PEU, followed by additional theoretical variables (Subjective Norm, Facilitators, and Compatibility) in the second block. Other control variables (age, gender, medical specialty, number of years in clinical practice, and the highest grade obtained) were also tested.

A statistical significance threshold of 0.05 was chosen. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. The analyses were performed using SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Characteristics of the Participating Healthcare Professionals

Among the 234 healthcare professionals who received the questionnaire, 21 physicians and 72 nurses responded (see Table 2). A response rate of 39.7% was thus achieved. More than 80% of respondents were women. Nearly 48.4% were under 40 years old, 48.4% were between the ages of 40 and 60, and only 3.2% were over 60 years old. Almost 4.3% of the respondents were specialized in pulmonology, 14% in cardiology, and nearly 27% in internal medicine. Respondents had on average 14.89 years (SD=10.86) in clinical practice. Three of the participating physicians held a PhD degree in addition to their medical degree.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the Health Professionals (n=93)

| |

ALL PARTICIPANTS (N=93) |

NURSES (N=72) |

PHYSICIANS (N=21) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARACTERISTICS | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | 76 | 81.72 | 69 | 95.83 | 7 | 33.33 |

| Men | 17 | 18.28 | 3 | 4.16 | 14 | 66.66 |

| Age | ||||||

| <30 | 24 | 25.81 | 23 | 31.94 | 1 | 4.76 |

| 30–39 | 21 | 22.58 | 14 | 19.44 | 7 | 33.33 |

| 40–49 | 30 | 32.26 | 28 | 38.88 | 2 | 9.52 |

| 50–59 | 15 | 16.13 | 7 | 9.72 | 8 | 38.09 |

| >60 | 3 | 3.23 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14.28 |

| Medical specialty | ||||||

| Pulmonology | 4 | 4.30 | 2 | 2.77 | 2 | 9.52 |

| Cardiology | 13 | 13.97 | 9 | 12.50 | 4 | 19.04 |

| Internal medicine | 25 | 26.88 | 10 | 13.88 | 15 | 71.42 |

| Unspecified | 51 | 54.83 | 51 | 70.83 | — | — |

| Years in clinical practice | 14.89 (SD=10.86) | 12.75 (SD=9.20) | 21.71 (SD=13.01) | |||

| Highest educational grade | ||||||

| Nursing diploma | 72 | 77.42 | 72 | 100 | — | — |

| M.D. | 18 | 19.35 | — | — | 18 | 85.71 |

| M.D.+Master degree | 0 | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| M.D.+Ph.D. | 3 | 3.22 | — | — | 3 | 14.28 |

SD, standard deviation.

Descriptive Statistics of the Theoretical Variables

The descriptive statistics of the theoretical variables are presented in Table 3. Theoretical constructs were well correlated with each other and with the dependent variable (Intention to Use). Nevertheless, multicolinearity was detected between the variables attitude and PU (Spearman correlation of 0.90). This finding is not surprising given that PU captures the same construct as the Attitude from the Theory of Reasoned Action. Consequently, the attitude was not included in the final model.

Table 3.

Descriptive Analysis of the Variables of the Model

| PU | PEU | ATT | COM | SN | FAC | HAB | IU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 5.32 | 4.92 | 5.39 | 5.32 | 4.92 | 5.40 | 5.76 | 5.31 |

| SD | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

| Correlation with IU | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 1.00 |

ATT, Attitude; COM, Compatibility; FAC, Facilitators; HAB, Habit; IU, Intention to Use; SN, Subjective Norm.

Results of the Logistic Regression

The results presented in Table 4 show that the TAM alone is good at predicting intention to use telemonitoring (χ2 was significant, Nagelkerke R2=0.42) and that the only significant predictor was PU (OR: 5.28, 95% CI: 2.12–13.11). This means that for every one unit increase in the PU score we expect a 5.28 increase in the odds of having a high intention to use telemonitoring, holding all other variables constant.

Table 4.

Results of the Logistic Regression: Original and Modified Technology Acceptance Model

| INDEPENDENT VARIABLES | MULTIVARIATE REGRESSION OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original TAMa | |||

| PU | 5.28 | 2.12–13.11 | 0.000 |

| PEU | 1.30 | 0.57–2.94 | 0.536 |

| Modified TAMb | |||

| PU | 1.47 | 0.37–5.93 | 0.585 |

| PEU | 0.82 | 0.33–2.06 | 0.672 |

| Compatibility | 1.65 | 0.38–7.10 | 0.503 |

| Subjective norm | 1.90 | 0.77–4.67 | 0.162 |

| Facilitators | 4.96 | 1.59–15.55 | 0.006 |

χ2=35.35, p<0.05, Nagelkerke R2=0.42.

χ2=48.76, p<0.05, Nagelkerke R2=0.54.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; TAM, Technology Acceptance Model.

When other theoretical variables are considered, the model is still significant and more powerful (Nagelkerke R2=0.54). However, the PU and PEU variables from the TAM become nonsignificant (OR: 1.47, 95% CI: 0.37–5.93 and OR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.33–2.06, respectively) and the only significant predictor in this model is the variable Facilitators (OR: 4.96, 95% CI: 1.59–15.55). This means that the variable Facilitators accounts for most of the odds of having a high intention to use telemonitoring. Finally, the addition of other variables such as age, gender, medical specialty, number of years in clinical practice, and the highest grade obtained does not improve the model.

In the view of the importance of the variable Facilitators, a discriminant analysis was conducted to identify whether the items comprised in the facilitators variable differed significantly between low-to-moderate intenders and high intenders. The results show that the two groups differ significantly on the three items of the facilitators variable: (1) “I think that my center has the necessary infrastructure to support my use of telemonitoring systems,” (2) “I would use telemonitoring systems if I receive appropriate training,” and (3) “I would use telemonitoring systems if I receive the necessary technical assistance.”

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the TAM is a good predictive model of healthcare professionals' intention to use telemonitoring systems. The perception of facilitators is the most influential variable in the prediction of nurses' and physicians' intention to use this new technology. The results of this study are consistent with those of a previous study conducted by our team to evaluate healthcare professionals' adoption of teledermatology.28 The perception of facilitators was identified as the most important factor in the prediction of healthcare professionals' intention to use teledermatology.

The results of the present study are important because they point out the key elements that should be considered before the development and the implementation of telemonitoring programs. To improve the acceptance of telemonitoring, it is essential to provide the adequate training to healthcare professionals, ensure that the healthcare system possesses the necessary infrastructure, and provide the required technical assistance to the various users of telemonitoring systems.

Our study showed that telemonitoring acceptance was relatively high among healthcare professionals. Healthcare providers, especially nurses and physicians, are considered the most important gatekeepers for telemedicine services.29 Thus, they have a direct role to play in the implementation and diffusion of telemonitoring services. Further, most patients are informed of telemedicine programs by their healthcare providers and could be more willing to receive telemonitoring services if they perceive support from nurses and physicians. In addition, the decision of whether to use this service or not depends mainly on providers' willingness.29

Study Limitations

The results of our study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, despite the fact that an acceptable response rate was achieved, it was not possible to document differences between healthcare professionals who participated in this survey and those who did not. Second, our questionnaire was adapted from the previous work and was only face and content validated by experts. It seems essential to further validate and to establish the test-retest reliability of this instrument. Finally, our theoretical model encompasses additional constructs belonging to other theories. It would be interesting to test this model in future work and to add other potentially important variables to improve the predictive power of the theoretical model.

Conclusions

Telemonitoring is increasingly seen as an efficient and cost-effective means for improving clinical outcomes and increasing patient involvement in all aspects of their own care. However, it is important to acknowledge the fact that telemonitoring systems are complementary interventions and are not substitutes for primary care. Healthcare provider acceptance of this new system represents one of the key issues that must be addressed to ensure the successful implementation of telemonitoring programs. Our study has shown that the most important factor that seems to influence healthcare professionals' acceptance of telemonitoring is the perception of appropriate organizational infrastructure, training, and support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the framework of collaboration designed for the Quality Plan of the Spanish Health System. The project was funded by the Health Institute Carlos III (Spanish Ministry of Health) and the Department of Health and Consumer Affairs of the Basque Government. Marie Pierre Gagnon holds a New Investigator career grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant no. 200609MSH-167016-HAS-CFBA-111141).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (US) Telemedicine: A guide to assessing telecommunications in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996. Committee on Evaluating Clinical Applications of Telemedicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nangalia V. Prytherch DR. Smith GB. Health technology assessment review: Remote monitoring of vital signs—current status and future challenges. Crit Care. 2010;14:233. doi: 10.1186/cc9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pare G. Jaana M. Sicotte C. Systematic review of home telemonitoring for chronic diseases: The evidence base. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:269–277. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buysse H. De Moor G. Van Maele G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of telemonitoring for high-risk pregnant women. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seto E. Cost comparison between telemonitoring and usual care of heart failure: A systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:679–686. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pare G. Sicotte C. St-Jules D. Gauthier R. Cost-minimization analysis of a telehomecare program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12:114–121. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pare G. Moqadem K. Pineau G. St-Hilaire C. Clinical effects of home telemonitoring in the context of diabetes, asthma, heart failure and hypertension: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e21. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaana M. Pare G. Home telemonitoring of patients with diabetes: A systematic assessment of observed effects. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:242–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McManus RJ. Mant J. Bray EP, et al. Telemonitoring and self-management in the control of hypertension (TASMINH2): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:163–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AbuDagga A. Resnick HE. Alwan M. Impact of blood pressure telemonitoring on hypertension outcomes: A literature review. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:830–838. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran K. Polisena J. Coyle D, et al. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2008. Home telehealth for chronic disease management. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark RA. Inglis SC. McAlister FA, et al. Telemonitoring or structured telephone support programmes for patients with chronic heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:942. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39156.536968.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis SC. Clark RA. McAlister FA, et al. Structured telephone support or telemonitoring programmes for patients with chronic heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007228.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polisena J. Tran K. Cimon K, et al. Home telemonitoring for congestive heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:68–76. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polisena J. Tran K. Cimon K, et al. Home telehealth for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:120–127. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sicotte C. Pare G. Morin S, et al. Effects of home telemonitoring to support improved care for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17:95–103. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma U. Barnett J. Clarke M. Clinical users' perspective on telemonitoring of patients with long term conditions: Understood through concepts of Giddens's structuration theory & consequence of modernity. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160:545–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giddens A. The consequences of modernity. Cambridge: Polity; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giddens A. Central problems in social theory: Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis. London: Macmillan; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent C. Reinharz D. Deaudelin I, et al. Understanding personal determinants in the adoption of telesurveillance in elder home care by community health workers. J Commun Pract. 2007;15:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent C. Reinharz D. Deaudelin I. Garceau M. Why some health professionals adopt elder home care telemonitoring service and others not? In: Pruski A, editor; Knops H, editor. Assistive technology: From virtuality to reality. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2001. pp. 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Triandis HC. Values, attitudes and interpersonal behavior. In: Page MM, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1979: Beliefs, attitudes and values. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broens TH. Huis in't Veld RM. Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, et al. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: A literature study. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:303–309. doi: 10.1258/135763307781644951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chau PYK. Hu PJ. Examining a model of information technology acceptance by individual professionals: An exploratory study. J Manage Inf Syst. 2002;18:191–229. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers EM. The diffusion of innovations. 4th. New York: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fishbein M. Azjen I. Belief, attitude, intentions and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Boston: Addison-Westley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orruño E. Gagnon M-P. Asua J. Ben Abdeljelil A. Evaluation of teledermatology adoption by health care professionals using a modified Technology Acceptance Model. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:303–307. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitten PS. Mackert MS. Addressing telehealth's foremost barrier: Provider as initial gatekeeper. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:517–521. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.