Abstract

The incidence of precocious puberty (PP, the appearance of signs of pubertal development at an abnormally early age), is rapidly rising, concurrent with changes of diet, lifestyles, and social environment. The current diagnostic methods are based on a hormone (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) stimulation test, which is costly, time-consuming, and uncomfortable for patients. The lack of molecular biomarkers to support simple laboratory tests, such as a blood or urine test, has been a long standing bottleneck in the clinical diagnosis and evaluation of PP. Here we report a metabolomic study using an ultra performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry. Urine metabolites from 163 individuals were profiled, and the metabolic alterations were analyzed after treatment of central precocious puberty (CPP) with triptorelin depot. A panel of biomarkers selected from >70 differentially expressed urinary metabolites by receiver operating characteristic and logistic regression analysis provided excellent predictive power with high sensitivity and specificity for PP. The altered metabolic profile of the PP patients was characterized by three major perturbed metabolic pathways: catecholamine, serotonin metabolism, and tricarboxylic acid cycle, presumably resulting from activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Treatment with triptorelin depot was able to normalize these three altered pathways. Additionally, significant changes in the urine levels of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, indoleacetic acid, 5-hydroxytryptophan, and 5-hydroxykynurenamine in the CPP group suggest that the development of CPP condition may involve an alteration in symbiotic gut microbial composition.

Puberty, the primary regulator of the reproductive process in vertebrates, is a complex biological process affected by systemic and environmental factors such as activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPGA)1 (1). Precocious puberty (PP) is defined as the onset of puberty before the age of eight in girls and nine in boys, mainly because of the precocious activation of the gonadotropic axis, which induces several somatic and psychological modifications (1). PP results in an increasing growth rate and rapid acceleration of bone maturation, which leads to the early fusion of epiphyseal and eventually adult short stature (2). The abnormal pubertal development will impact physical and psychological health of PP individuals over a long period of time. The incidence of PP is about 0.6% throughout the world (3) and is 10 times more common in girls than in boys, and girls with PP exhibit a greater risk of developing breast cancer (4).

PP can be divided into two types, central precocious puberty (CPP, also called “true precocious puberty”) and peripheral precocious puberty (PPP, or “pseudo precocious puberty”), depending on whether or not the HPGA is involved (5). CPP is gonadotropin-dependent early maturation and results primarily from activation of HPGA, whereas PPP is gonadotropin-independent; the causes of PPP include both endogenous sources such as gonadal tumors, adrenal tumors, and congenital disorders and exposure to exogenous steroids (5). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which is produced in the hypothalamus and acts on the pituitary gland, stimulates the pulsatile production and release of gonadotropins including luteinizing hormones (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormones (FSH) to maintain normal reproductive functions (1). Correct diagnosis of the etiology of sexual precocity is critical, because treatment of patients with PPP is different from those with CPP, and some PPP can secondarily evolve into CPP (6). Standard treatment of CPP is to suppress the activation of HPGA (7) through periodically using GnRH agonists such as leuprorelin depot (8) and triptorelin depot (9, 10). Patients with CPP have to continue receiving this medication until they reach the average age of the onset of puberty. However, the underlying mechanisms of PP and the global changes in metabolism and physiology before and after treatment are poorly understood.

Because of the lack of molecular biomarkers to support simple laboratory tests, the clinical diagnosis and evaluation of PP has to rely on a hormone (GnRH) stimulation test, which is costly, time-consuming, and uncomfortable for patients (11). To avoid these problems, several attempts, such as measurement of basal gonadotropin levels or subcutaneous leuprolide acetate test with a single sample, have been made (12–14). None of these alternative tests have been standardized sufficiently or proven to be equal or superior to the GnRH test as yet. In cases of precocious puberty, the GnRH test may also need to be repeated during treatment with GnRH analog to assess the effectiveness of suppression and to adjust the dose of the analog (15, 16).

The development of PP not only involves the changes of endocrine (17) but also changes in the concentration of endogenous metabolites (18). Metabolic profile of biofluids (urine, serum, and saliva) can be altered by a variety of physiological processes following pathophysiological stimuli; therefore, global perturbation in these profiles may demonstrate the presence of a particular disease (19, 20). Metabonomics or metabolomics, with the enhanced feasibility of acquiring high throughput “snapshots” of the metabolic status of a whole organism (21, 22), is rapidly emerging as a biochemical profiling technology in many fields such as clinical research (23), drug discovery (24), toxicology (25), botany (26), microbiology (27), and nutrition research (28, 29). The objective of this study was to obtain a system view of the metabolic responses to CPP or PPP by simultaneously assaying metabolic profiles and identify urinary metabolites as potential biomarkers to diagnose and stratify CPP and PPP using this high resolution and high sensitivity analytical platform. In the present study, we profiled urine metabolites in 163 participants using ultra performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOFMS) and gas chromatography-time of flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOFMS). These two analytical platforms (UPLC-QTOFMS and GC-TOFMS) were used to maximize the number of the detectable metabolites for the evaluation of the phenotypic variations in CPP and PPP subjects and the effect of triptorelin depot intervention. The urine concentrations of several important hormones were also determined in these subjects. This profiling approach was aimed to provide vital information for biomarker discovery as well as the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of CPP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Leucine-enkephalin, formic acid, chloroform, pyridine, anhydrous sodium sulfate, BSTFA (1% TMCS), heptadecanoic acid, methoxyamine, and l-2-chlorophenylalanine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methanol and acetonitrile (HPLC grade) were obtained from Merck. All of the aqueous solutions were prepared with ultrapure water produced by a Milli-Q system (18.2 mΩ; Millipore, Bedford, MA).

Clinical Samples

In this study, a total of 106 precocious puberty subjects were enrolled, including 57 CPP girls and 49 PPP girls (see Table I). The diagnosis was carried out by the children's hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China). A total of 57 age-matched healthy girls were recruited as healthy controls. The body mass index and GnRH stimulation test results were recorded (see Table I). PP girls appeared to have a higher body weight than that of their age-matched healthy counterparts. The body mass index in PP subjects is significantly greater than the control group (p < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance) but did not reach the criterion for obesity. Urina sanguinis samples (urine passed on rising in the morning) (30) were collected from all the participants prior to the administration of any medication. CPP subjects received triptorelin depot at 50–100 μg/kg of body weight/month via intramuscular injection, and urina sanguinis samples were also collected at each of the last days in the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth month post-dose. All of the urine samples were immediately centrifuged at 13,000 rpm (15,700 × g) for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was immediately stored at −80 °C until analysis. Study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital, and written informed consents were signed by all participants. Urine sample preparation for UPLC-QTOFMS and GC-TOFMS analysis was done as described previously (20, 29).

Table I. Clinical information of human subjects.

| Characteristics | Subjects |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CPP (n = 57) | PPP (n = 49) | Control (n = 57) | |

| Age (years) | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 7.7 ± 1.3 | 8.0 ± 0.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.6 ± 1.6a | 17.8 ± 2.4a | 15.2 ± 1.2 |

| GnRH stimulation test (IU/liter) | LH peak > 5.0, LH/FSH > 0.6 | LH peak < 5.0, LH/FSH < 0.6 | |

| Pathological conditions | None | None | None |

a p < 0.01, compared with the control group, one-way analysis of variance.

Sample Analysis by UPLC-QTOFMS

Urine metabolite profiling was performed according to our previous published work (29) (for details, see the supplemental materials). Chromatographic separations were performed on a 2.1 × 100-mm 1.7-μm ACQUITY BEH C18 column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) using an ultra performance liquid chromatography system (Waters Corp.). Data were acquired using a Waters Q-TOF Premier MS system (Waters Corp.) operated in positive ion electrospray ionization mode.

UPLC-QTOFMS Spectral Data Processing

The UPLC-QTOFMS data from the urine samples were analyzed to identify potential discriminant variables. The ES+ raw data were analyzed by the MarkerLynx applications manager version 4.1 (Waters, Manchester, UK) using parameters reported in our previous work (20, 29). The resulting data from the UPLC-QTOFMS platforms were subjected to multivariate statistical analyses to establish characteristic metabolomic profiles associated with different response phenotypes (CPP or PPP). For details, see the supplemental materials.

Sample Preparation and Analysis by GC-TOFMS

Urine analysis by GC-TOFMS was performed according to our previous published work with minor modifications (20, 31). Briefly, each 1-μl aliquot of the derivatized solution was injected into an Agilent 6890N gas chromatography in splitless mode coupled with a Pegasus HT time-of-flight mass spectrometer and separated on a DB-5 MS capillary column with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 ml/min (for details, see the supplemental materials).

GC-TOFMS Data Analysis

The acquired MS files from GC-TOFMS analysis were performed according to our previous published work (20, 31). Briefly, the MS files were exported in NetCDF format by ChromaTOF software (v3.30; Leco Co.). CDF files were extracted using custom scripts in the MATLAB 7.1 (The MathWorks, Inc.) for data pretreatment. The resulting three-dimensional data set included sample information and peak retention time, and peak intensities will be subject to multivariate statistical analyses to establish characteristic metabolomic profiles associated with different response phenotypes (CPP or PPP). Cluster heat maps were performed in Matlab 7.1 software (Mathworks, Inc.). For details, see the supplemental materials.

Metabolite Annotation and Marker Selection

Compound annotation is performed using our in-house library containing ∼750 mammalian metabolite standards. For UPLC-QTOFMS-generated data, identification was performed by comparing the accurate mass (m/z) and retention time (Rt) of reference standards in our in-house library and the accurate mass of compounds obtained from the web-based resources such as the Human Metabolome Database. For GC-TOFMS-generated data, identification was processed by comparing the mass fragments and Rt with our in-house library or mass fragments with NIST 05 standard mass spectral databases in NIST MS search 2.0 (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD) software with a similarity of more than 70%.

For UPLC-QTOFMS data, significant variables (markers) are selected based on a threshold of a multivariate statistical parameter (SIMCA-P 12.0 software; Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden), such as variable importance in the projection (VIP) value (VIP > 1) from a typical 7-fold cross-validated orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) model. For GC-TOFMS-generated data, the significant variables are selected with VIP value (VIP > 1), from a typical 7-fold cross-validated OPLS-DA model. These differential metabolites selected from the OPLS-DA model are validated at a univariate level with Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. The critical p value of the test is usually set to 0.05. The false discovery rate (32, 33), a statistical approach to the problem of multiple comparisons, was used in this study to verify the discriminant metabolites chosen by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney p values (<0.05).

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis and Prediction Models

The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was done as described previously (34). Using the results obtained from the OPLS-DA analysis of the UPLC-QTOFMS and GC-TOFMS data, we conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics 19 (SPSS Inc.) to evaluate the predictive power of each of the discriminant metabolites (31, 34). The cutpoint was determined for each biomarker by searching for those that yielded both high sensitivity and specificity. ROC curves were then plotted on the basis of the set of optimal sensitivity and specificity values. The area under the curve (AUC) was computed via numerical integration of the ROC curves. The metabolite signature that has the largest area under the ROC curve was identified as having the strongest predictive power for detecting CPP.

A binary logistic regression prediction model (35) was constructed using the binary outcome of the disease (CPP, PPP) and healthy control as dependent variables and validated using leave-one-out cross-validation. The forward stepwise regression, the procedure to select the strongest variables until there are no more significant predictors in the data set, was used for marker selection. The likelihood ratio chi-squared test was used to assess significance in logistic regression because the errors are assumed to follow a binomial distribution. This test assigns a p value to each variable to assess significance. Therefore, the most important variable is the one with the smallest p value. The leave-one-out cross-validation was performed to predict the property value for a compound from the data set, which is in turn predicted from the regression equation calculated from the data for all other compounds. The cross-validation error rate is the number of samples predicted incorrectly divided by the number of samples. ROC curves for the logistic model were plotted with the fitted probabilities from the model as possible cut-points for the computation of sensitivity and specificity.

Additionally, the logistic regression model was tested with a cross-validation analysis using an 80% random sample of the data set as a training sample and a holdout sample containing the remaining 20% of the subjects. The classification accuracy for the holdout sample is used to estimate how well the model based on the training sample will perform for the population represented by the data set.

Urine Hormone Measurements

The urine concentrations of LH, FSH, estradiol, progesterone, prolactin, and testosterone were measured using specific RIA kits (Beijing North Biotechnology Institute, Beijing, China). Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

UPLC-QTOFMS Analysis of Urine Metabolite Profiles

We first performed metabolic profiling in subjects with CPP and PPP and healthy controls (Table I) with UPLC-QTOFMS. Approximately 10,280 peaks (defined by a pair of m/z value and Rt) were obtained from each urine sample using the method reported in our previous work (29). Although only a fraction of these peaks are selected as differential metabolites and subsequently identified, the information obtained from the metabolomic analysis is important to elucidate the pathophysiological changes as a result of CPP or PPP. Typical UPLC-QTOFMS base peak intensity chromatograms of urine samples from a CPP subject, a PPP subject, and a healthy control were given in supplemental Fig. 1A, showing minor variations of each other. After data normalization, principal component analysis of the data set was performed, which showed a trend of intergroup separation on the scores plot (not shown). However, the metabolic profiles clearly formed three clusters on the scores plot of partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) model of the UPLC-QTOFMS spectral data (supplemental Fig. 1B).

A four-component PLS-DA model was obtained from the UPLC-QTOFMS data set with satisfactory modeling and prediction results (R2Ycum > 0.7, Q2Ycum > 0.4). Supplemental Fig. 1B shows the scatter plot using the scores of the second principal component (PC2) and the third principal component (PC3). PLS-DA was able to visually demonstrate the degree of metabolic alterations from each other, suggesting the CPP, PPP, and healthy controls have different urinary metabolic patterns. Furthermore, supervised orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) were performed between each two classes (36) to select the differential metabolites contributing to the intergroup separation (i.e. different metabolic phenotype). The modeling parameters were summarized in supplemental Table 1. The CPP and control group were completely separated from each other with a 7-fold cross-validated OPLS-DA model (Fig. 1A). Based on the cut-off value of variable importance in the project (VIP > 1) of the OPLS-DA model and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05) as described under “Experimental Procedures,” a total of 54 differential metabolites were obtained, and 35 of them were validated by available reference standards (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table 2). All of the metabolites listed in supplemental Tables 2–4 were discriminant (Wilcoxon p < 0.05), with a false discovery rate of 10%. Furthermore, we randomly divided the whole sample set into two subsets: the training set (38 CPP patients and 38 healthy controls) and the testing set (19 CPP patients and 19 healthy controls). Thirty-eight healthy controls and 38 CPP patients can be successfully differentiated by PC1 (the first principal component of the model) with statistical significance (supplemental Fig. 2). Supplemental Fig. 2 shows the prediction results of the 38 testing samples using the model established with the 76 training samples. All of the test samples are correctly classified as CPP or healthy subjects, suggesting that these markers are of great potential for CPP diagnosis. The permutation test (200 times) of the PLS-DA model corresponding to principal component analysis model including correlation coefficient between the original Y and the permuted Y versus the cumulative R2 and Q2, with the regression line was shown in supplemental Fig. 3. The intercept (R2 and Q2 when correlation coefficient is zero), which is correlated with the extent of overfitting is rather small (R2 = 0.44, Q2 = −0.12 for UPLC-QTOFMS data, and R2 = 0.58, Q2 = −0.16 for GC-TOFMS data), suggesting that the model is satisfactory.

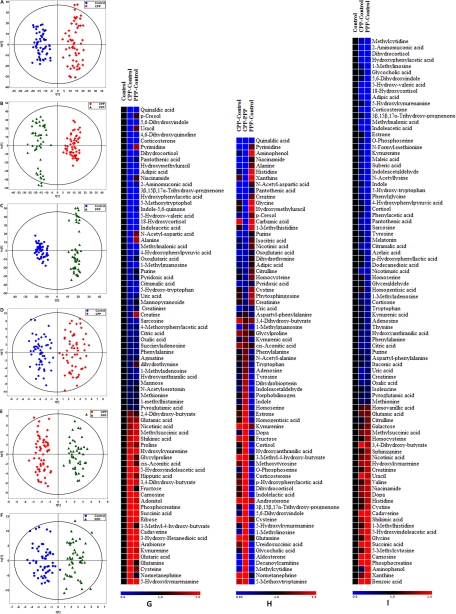

Fig. 1.

OPLS-DA score plots of metabolic profiles derived from the data of UPLC-QTOFMS (A–C) and GC-TOFMS (D–F) among the CPP group, the PPP group, and the healthy control group. The model parameters of OPLS-DA score plots were listed in supplemental Tables 1 and 2, and relative changes in metabolites in the CPP group were compared with the healthy control group (G); the CPP group compared with the PPP group (H); and the PPP group compared with the healthy control group (I). Heat maps show changes in metabolites of healthy controls compared with the CPP and PPP groups or CPP compared with PPP. Shades of red and blue represent fold increase and fold decrease of a metabolite, respectively, in the CPP or PPP group relative to healthy control or in the CPP group compared with the PPP group (see color scale).

The differential metabolites accountable for the intergroup separation between the CPP and PPP groups and between PPP and healthy control groups, respectively, were also identified by the OPLS-DA model (Fig. 1, B and C). Sixty-five and seventy differential metabolites contributing to the intergroup separation (CPP-PPP and PPP-control, respectively) were selected (Fig. 1 and supplemental Tables 3 and 4) based on the VIP value (VIP > 1) of the OPLS-DA model (Fig. 1) and the p value of Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (p < 0.05).

GC-TOFMS Analysis of Urine Metabolite Profiles

The representative total ion current chromatograms of a CPP patient, a PPP patient, and a healthy control were shown in supplemental Fig. 1C. After removing two internal standards, a total of 300 variables were used in the following analysis. A four-component PLS-DA model was constructed from the GC-TOFMS data set with satisfactory modeling and prediction results (supplemental Fig. 1D). The OPLS-DA scores plot between CPP and healthy controls showed clear separations using one predictive component and two orthogonal components (Fig. 1D), with satisfactory modeling and predictive abilities. The modeling parameters were summarized in supplemental Table 5. Twenty-two differential metabolites were obtained, and 14 of them were validated by available reference standards (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table 2) with VIP values (VIP > 1) of the OPLS-DA model and the p value of Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test set at 0.05 by GC-TOFMS.

Analogously, the differential metabolites accountable for the intergroup separation between the CPP and PPP groups and between the PPP and healthy control groups, respectively, were also identified by the OPLS-DA model of GC-TOFMS spectral data (Fig. 1, E and F). Differential metabolites contributing to the intergroup separation were obtained based on the VIP value (VIP >1) of OPLS-DA model and the p value of Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test set at 0.05. Seven and 15 differential metabolites contributing for the intergroup separation (CPP-PPP and PPP-control, respectively) were obtained (Fig. 1 and supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Metabolite Markers Associated with Overweight

Because there is a statistically significant difference in body mass index values between the control group and PP groups (Table I), we tried to identify metabolite markers associated with overweight phenotype among subjects in the control group. As listed in supplemental Table 6, 12 differentially expressed metabolites were found in overweight subjects compared with nonoverweight subjects. These metabolites are of statistical significance (p < 0.05), including tetrahydrobiopterin, p-hydroxyphenyllactic acid, p-aminobenzoic acid, N4-acetylcytidine, malonic acid, imidazole-4-acetaldehyde, hypotaurine, glutathione, aminomalonic acid, acetylcarnitine, 4-(3-pyridyl)-3-butenoic acid, and 2,6-dimethylheptanoyl carnitine. Two metabolites, p-hydroxyphenyllactic acid and aminomalonic acid, were found differentially expressed in PPP relative to healthy controls; malonic acid, hypotaurine, and aminomalonic acid were differential between CPP and PPP; and hypotaurine was differential in CPP relative to healthy controls. Therefore, they were removed from the list of PP markers.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis and Prediction Models

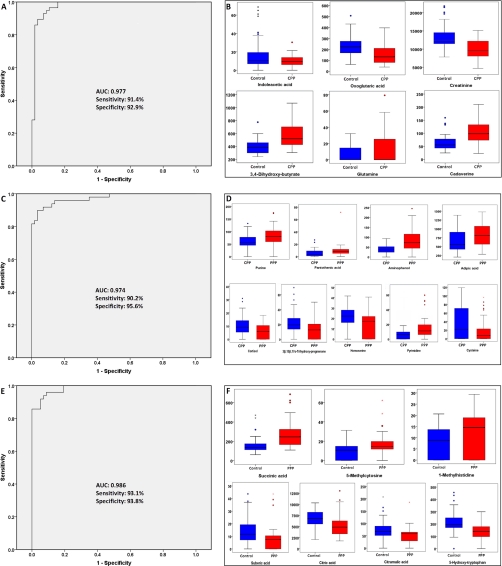

To demonstrate the utility of urinary metabolites for the discrimination between CPP and healthy control, a logistic regression model was built based on the 78 validated discriminant metabolites (supplemental Table 2), and as a result, creatinine, 3,4-dihydroxy-butyrate, cadaverine, oxoglutaric acid, glutamine, and indoleacetic acid, in combination, provided the best prediction (Table II). The coefficient values were positive for 3,4-dihydroxy-butyrate, cadaverine, and glutamine, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine increased the probability that the sample was obtained from an CPP subject, whereas for creatinine, oxoglutaric acid, and indoleacetic acid, the coefficient values were negative, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine decreased the probability that the sample was obtained from an CPP subject. The leave-one-out cross-validation (CV) error rate based on logistic regression model was 8.8% (10 of 114). The ROC curve was computed for the logistic regression model. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained a sensitivity of 91.4%, a specificity of 92.9%, and a positive predictive value of 93.0%. The calculated ROC AUC was 0.977 (95% confidence intervals, 0.950, 1.000) for the logistic regression model (Fig. 2A). By using the same set of metabolites between CPP and healthy controls, we obtained a sensitivity of 76.8%, a specificity of 72.0%, and a positive predictive value of 75.4% for the distinguishing PPP from controls. 3,4-Dihydroxy-butyrate (1.44-fold to healthy control), cadaverine (1.64-fold to healthy control), and glutamine (2.06-fold to healthy control) were shown at a significantly higher level in CPP, whereas creatinine (0.74-fold to healthy control), oxoglutaric acid (0.68-fold to healthy control), and indoleacetic acid (0.59-fold to healthy control) were lower in CPP (Table II and Fig. 2B). These were in accordance with the result obtained from the logistic regression model, in which 3,4-dihydroxy-butyrate, cadaverine, and glutamine have a positive coefficient value, whereas creatinine, oxoglutaric acid, and indoleacetic acid have negative coefficient values. The classification accuracy for the holdout sample of an 80–20 CV is 87.5%. The trained model also showed high separation ability in the CV (AUC: 0.938 (95% confidence intervals, 0.892, 0.984)). The ROC curves are shown in supplemental Fig. 4.

Table II. Urinary metabolite signatures selected by logistic regression model for the discrimination of CPP from healthy control or PPP and PPP from healthy control, respectively.

| Markers | Coefficient value | S.E. | p value | FCa | pb | VIPc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPP-control | ||||||

| Creatinined | −0.0008 | 0.0002 | 4.31E-04 | 0.74 | 1.77E-09 | 3.02 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxy-butyrate | 0.0085 | 0.0034 | 1.23E-02 | 1.44 | 1.00E-08 | 2.85 |

| Cadaverined | 0.0593 | 0.0153 | 1.10E-04 | 1.64 | 6.11E-08 | 2.53 |

| Oxoglutaric acidd | −0.0207 | 0.0058 | 3.23E-04 | 0.68 | 4.25E-05 | 2.18 |

| Glutamined | 0.0800 | 0.0350 | 2.22E-02 | 2.06 | 1.59E-02 | 1.70 |

| Indoleacetic acidd | −0.0684 | 0.0307 | 2.61E-02 | 0.59 | 5.02E-03 | 1.97 |

| Constant | 4.8600 | 2.6534 | 6.70E-02 | |||

| CPP-PPP | ||||||

| Pantothenic acidd | −0.1572 | 0.0841 | 6.15E-02 | 0.59 | 1.77E-02 | 1.78 |

| 3β,15β,17α-Trihydroxy-pregnenone | 0.1390 | 0.0528 | 8.50E-03 | 1.83 | 3.81E-04 | 2.19 |

| Adipic acidd | −0.0055 | 0.0019 | 4.39E-03 | 0.77 | 2.42E-03 | 1.92 |

| Aminophenold | −0.0929 | 0.0275 | 7.27E-04 | 0.43 | 1.18E-07 | 3.46 |

| Cortisold | 0.1658 | 0.0790 | 3.58E-02 | 1.52 | 9.60E-03 | 1.61 |

| Cysteined | 0.0589 | 0.0210 | 5.06E-03 | 1.91 | 9.93E-03 | 1.59 |

| Homoserined | 0.1824 | 0.0762 | 1.66E-02 | 1.46 | 7.42E-04 | 2.16 |

| Pyrimidine | −0.0341 | 0.0193 | 7.77E-02 | 0.40 | 1.66E-04 | 2.53 |

| Purined | −0.1745 | 0.0877 | 4.65E-02 | 0.72 | 1.37E-04 | 2.43 |

| Constant | 5.2300 | 2.2832 | 2.20E-02 | |||

| PPP-control | ||||||

| Citric acidd | −0.0017 | 0.0005 | 5.71E-04 | 0.78 | 1.08E-03 | 2.18 |

| Succinic acidd | 0.0425 | 0.0118 | 3.18E-04 | 1.71 | 2.17E-06 | 3.17 |

| 1-Methylhistidined | 0.3799 | 0.1296 | 3.37E-03 | 1.61 | 3.88E-03 | 1.73 |

| 5-Hydroxy-tryptophand | −0.1990 | 0.0770 | 9.77E-03 | 0.63 | 5.75E-07 | 2.79 |

| 5-Methylcytosine | 0.2354 | 0.0890 | 8.21E-03 | 1.72 | 3.26E-03 | 1.76 |

| Citramalic acidd | −0.0570 | 0.0195 | 3.44E-03 | 0.68 | 1.68E-03 | 1.83 |

| Suberic acidd | −0.2715 | 0.0856 | 1.52E-03 | 0.59 | 6.74E-03 | 1.59 |

| Constant | 2.9966 | 1.7399 | 8.50E-02 |

a The fold change (FC) with a value larger than 1.0 indicates a relatively higher concentration present in CPP patients, whereas a value lower than 1.0 means a relatively lower concentration as compared with the PPP patients or healthy controls. A fold change (>1) also indicates a relatively higher concentration present in PPP patients as compared to the healthy controls, whereas a value of <1 means a relatively lower concentration.

b The p value was obtained from Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test.

c Variable importance in the projection (VIP) was obtained from OPLS-DA with a threshold of 1.0.

d Metabolites validated by reference standards.

Fig. 2.

A, ROC curve analysis for the predictive power of combined urinary biomarkers for distinguishing CPP from healthy control. The final logistic model included six urinary biomarkers, creatinine, 3,4-dihydroxy-butyrate, cadaverine, oxoglutaric acid, glutamine, and indoleacetic acid. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained sensitivity of 91.4% and specificity of 92.9% by ROC. The calculated area under the ROC curve was 0.977 (95% confidence intervals, 0.950, 1.000). B, box plots of six discriminant metabolites in distinguishing CPP from healthy control. C, ROC curve analysis for the predictive power of combined urinary biomarkers for distinguishing CPP from PPP. The final logistic model included nine urinary biomarkers, pantothenic acid, 3β,15β,17α-trihydroxy-pregnenone, adipic acid, aminophenol, cortisol, cysteine, homoserine, pyrimidine, and purine. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained sensitivity of 90.2% and specificity of 95.6% by ROC. The calculated area under the ROC curve was 0.974 (95% confidence intervals, 0.947, 1.000). D, box plots of nine discriminant metabolites in distinguishing CPP from PPP. E, ROC curve analysis for the predictive power of combined urinary biomarkers for distinguishing PPP from healthy controls. The final logistic model included seven urinary biomarkers: citric acid, succinic acid, 1-methylhistidine, 5-hydroxy-tryptophan, 5-methylcytosine, citramalic acid, and suberic acid. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained sensitivity of 93.1% and specificity of 93.8% by ROC. The calculated area under the ROC curve was 0.986 (95% confidence intervals, 0.970, 1.000). F, box plots of seven discriminant metabolites in distinguishing PPP from healthy control.

Analogously, we constructed the same logistic regression model based on the 77 validated biomarkers derived from the CPP group to the PPP group (supplemental Table 3), and consequently, pantothenic acid, 3β,15β,17α-trihydroxy-pregnenone, adipic acid, aminophenol, cortisol, cysteine, homoserine, pyrimidine, and purine, in combination, provided the best prediction (Table II). The coefficient values were positive for 3β,15β,17α-trihydroxy-pregnenone, cortisol, cysteine, and homoserine, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine increased the probability that the sample was obtained from an CPP subject, whereas for pantothenic acid, adipic acid, aminophenol, pyrimidine, and purine, the coefficient values were negative, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine decreased the probability that the sample was obtained from an CPP subject. The leave-one-out cross-validation error rate based on logistic regression models was 9.43% (10 of 106). The ROC curve was computed for the logistic regression model. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained a sensitivity of 90.2%, a specificity of 95.6%, and the positive predictive value of 96.5%. The calculated AUC was 0.974 (95% confidence intervals, 0.947, 1.000) for the logistic regression model (Fig. 2C). The levels of pantothenic acid, adipic acid, aminophenol, pyrimidine, and purine were significantly decreased in CPP, whereas 3β,15β,17α-trihydroxy-pregnenone, cortisol, cysteine, and homoserine were shown at higher levels in CPP (Table II and Fig. 2D). These findings were consistent with the results obtained from the logistic regression model. The classification accuracy for the holdout sample of an 80–20 CV is 83.3%. The trained model also showed high separation ability in the CV (AUC: 0.958 (95% confidence intervals, 0.926, 0.990)) as shown in supplemental Fig. 4.

For the analysis of metabolites derived from PPP group to healthy control group, we constructed the same logistic regression model based on a total of 89 validated biomarkers (supplemental Table 4), and consequently, citric acid, succinic acid, 1-methylhistidine, 5-hydroxy-tryptophan, 5-methylcytosine, citramalic acid, and suberic acid, in combination, provided the best prediction (Table II). The coefficient values were positive for succinic acid, 1-methylhistidine, and 5-methylcytosine, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine increased the probability that the sample was obtained from an PPP subject, whereas for citric acid, 5-hydroxy-tryptophan, citramalic acid, and suberic acid, the coefficient values were negative, indicating that the rise in their concentration in urine decreased the probability that the sample was obtained from an PPP subject (Table II and Fig. 2F). The leave-one-out cross-validation error rate based on logistic regression models was 6.14% (seven of 114). The ROC curve was computed for the logistic regression model. Using a cutoff probability of 50%, we obtained a sensitivity of 93.1% and a specificity of 93.8%. The positive predictive value was 94.7%. The calculated area under the ROC curve was 0.986 (95% confidence intervals, 0.970, 1.000) for the logistic regression model (Fig. 2E). The classification accuracy for the holdout sample of an 80–20 CV is 88.2%. The trained model also showed high separation ability in the CV (AUC: 0.952 (95% confidence intervals, 0.911, 0.993)) as shown in supplemental Fig. 4.

Metabolic Changes of CPP Subjects Associated with Drug Treatment

We performed metabolic profiling on 25 age-matched girls from the control group and the CPP group before and after drug treatment. Fig. 3 shows the trajectory of metabolite profiles of the control, pre-dose, and post-dose CPP groups at different time points ranging from 1 to 6 months. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, CPP subjects at the pre-dose stage exhibited a distinct urinary metabolite profile from that of the control subjects. The metabolomic profiling visualizes time-dependent metabolic alterations in the CPP subjects from 1 to 6 months post-dose, showing a drug-mediated recovery tendency toward a normal (control) state.

Fig. 3.

The trajectory of time-dependent changes in urinary metabolite profile (score plot of PC2) in the CPP group (pre-dose, the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth month treatment with triptorelin depot). Six representative metabolites from catecholamine and serotonin pathways exemplify a clear recovery trend in CPP patients treated with triptorelin depot over 6 months from the trend plot of metabolite changes in CPP group at pre-dose and at the second, fourth, and sixth months post-dose. FC represents the fold change of mean rank calculated from Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test on the CPP group versus the control group.

To further investigate the metabolic changes resulting from triptorelin depot treatment, we analyzed several key metabolites at different time points. Fig. 3 depicted the time-dependent trajectories of these representative metabolites in the CPP group at pre-dose and the second, fourth, and sixth months versus the control group. The differentially expressed metabolites in the urine of CPP subjects were gradually normalized as a result of triptorelin depot treatment.

Urinary Hormone Levels of CPP, PPP, and Healthy Control

Urine tests showed increases of all the six urine hormones levels, progesterone, LH, prolactin, FSH, estradiol, and testosterone, in the CPP and PPP groups compared with the healthy control group (Table III). Further, among the six hormones, there were significant increases of FSH, LH, and testosterone (p < 0.05) in the CPP group and of LH and testosterone (p < 0.05) in the PPP group, respectively, compared with the healthy control group. There is no statistical significance between CPP and PPP group from the data shown in Table III.

Table III. Urine hormone content determined in CPP, PPP, and healthy control group (ng/ml, mean ± S.E.).

| Group | Progesterone | LH | Prolactin | FSH | Estradiol | Testosterone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.016 ± 0.004 | 8.713 ± 0.618 | 85.711 ± 12.824 | 3.038 ± 0.360 | 6.244 ± 2.788 | 0.212 ± 0.026 |

| CPP | 0.021 ± 0.004 | 12.966 ± 1.117a | 113.806 ± 33.882 | 4.763 ± 0.705b | 71.750 ± 53.999 | 0.341 ± 0.053b |

| PPP | 0.022 ± 0.005 | 13.707 ± 1.618a | 82.449 ± 10.861 | 4.736 ± 0.837 | 19.799 ± 11.852 | 0.322 ± 0.046b |

a p < 0.01 compared to healthy control.

b p < 0.05 compared to healthy control.

DISCUSSION

Because the metabolomic data typically contains a large number of variables that are interrelated, multivariate statistical methods such as principal component analysis, PLS-DA and OPLS-DA coupled with univariate statistical methods such as Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test were used in this study. Our combined use of two analytical platforms takes advantage of complementary analytical outcomes and therefore broadens the window of important metabolic variations identified. Another advantage of utilizing the LC-MS and GC-MS in combination is that we can cross-validate the metabolites mutually detected by these two analytical platforms. The UPLC-QTOFMS-based metabolomic study identified significant variations between CPP patients and healthy controls in 54 metabolites, and GC-TOFMS was able to identify 22 differential metabolites. The OPLS-DA models derived from our current GC-TOFMS and UPLC-QTOFMS metabolic analysis showed good and similar separations between patients with CPP and healthy controls, highlighting the diagnostic potential of this noninvasive profiling approach. Discriminant metabolites were identified in CPP relative to PPP or the healthy control by comparison of the accurate mass of molecular weight (<2 ppm) with the reference standards available (Fig. 1 and supplemental Tables 2–4) and online databases such as the Human Metabolome Database. Characterizing the spectrum of metabolic alterations in CPP or PPP could reveal the pathways contingent on PP and holds potential for better understanding the pathogenesis of human PP. Little knowledge could be obtained about the metabolites alteration in biological fluids of individuals with PP until now. In the current study, we profiled multiple biochemical groups, enabling the discovery of a rich metabolic signature spanning amino acids and other nitrogenous compounds, catecholamine metabolism, the TCA cycle, serotonin metabolism, and purines (Fig. 1 and 4). A panel of metabolites was selected as potential biomarkers by using the ROC analysis and logistic regression model from a total of >70 metabolites (Table II and Fig. 2).

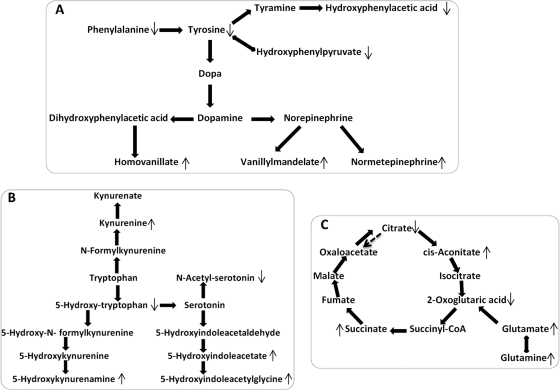

Fig. 4.

The altered metabolic pathways in the CPP group as compared with the control group. ↑ represents significantly elevated concentration of metabolites in the CPP group, whereas ↓ represents significantly lowered concentration of metabolites in the CPP group as compared with the control group. A, catecholamine metabolic pathway. B, tryptophan metabolic pathway. C, TCA cycle.

Urinary Metabolites from Triptorelin and Derivatives

Triptorelin depot, in the form of pamoate salt of triptorelin, is a synthetic decapeptide agonist analog of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone with an empirical formula of C64H82N18O13·C23H16O6 and a molecular mass of 1,699 Da (37). Triptorelin is eliminated by both the liver and the kidneys as an intact peptide, and thus far, no metabolites of triptorelin have been identified in the urine using our method (38). Given the fact that subjects received a monthly injection and that the urine samples were collected in the morning prior to the clinical visits, we assumed that there were no drug-related molecules contributing to the intergroup separation or classified as metabolite markers.

Metabolic Signatures of CPP

The PP subjects (Table I) usually were also overweight, and therefore the metabolite markers for PP may be derived from the status of overweight. We identified a panel of markers (supplemental Table 6) associated with overweight, which were then excluded from the list of PP markers.

HPGA is activated at the onset of puberty, and the hypothalamus produces a GnRH pulse, which stimulates the secretion of gonadotropins from the pituitary (1). The sympathetic nervous system neurotransmitters and catecholamines, especially norepinephrine, play important roles in the regulation of GnRH neurons; therefore it is possible that they also control GnRH neuron development in ontogenesis (39, 40), which is an important step in the secretion of GnRH (41).

In this study, lower levels of phenylalanine and tyrosine, the precursor of catecholamines, and significantly higher levels of homovanillic acid and vanillylmandelic acid, the major end products of catecholamine metabolism, were observed in the urine samples of the CPP subjects as compared with healthy controls. Normetanephrine, a methylated metabolite of norepinephrine, was observed at a higher expression level (2.95-fold in CPP to healthy control). These alterations in the CPP subjects suggested an up-regulated catecholamine metabolic pathway (Fig. 4A) and enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity, which are in agreement with previous observations of increased noradrenaline and adrenaline levels in both the ovaries and uteri of precocious female rats induced by hypothalamic lesions (42).

Serotonin (5-HT) may stimulate the hypothalamus to release GnRH through the phospholipase C pathway (43) and function as a mediator of hormone secretion (44, 45). We found the levels of 5-hydroxytryptophan, the immediate precursor of the neurotransmitter 5-HT, significantly decreased in the urine of CPP subjects, whereas the levels of 5-hdroxyindoleacetic acid and 5-hydroxykynurenamine were increased. Such variations are evidently the outcome of an up-regulated 5-HT metabolic pathway in the CPP population (Fig. 4B).

Glutamate, the major endogenous excitatory amino acid, exerts its action through ionotropic and metabotropic receptors, and the most abundant fast excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian nervous system (46, 47) plays a predominant role in the regulation of pulsatile gonadotropin release, induction of puberty, and preovulatory and steroid-induced gonadotropin surges reproductive axis (48). 3,4-Dihydroxybutyrate, the product of the catabolic pathway of 4-aminobutyrate via 4-hydroxybutyrate, is also the intermediate in neurotransmitter pathways (49). A significantly higher level of glutamate and 3,4-dihydroxybutyrate (Table II and Fig. 1) in CPP patients indicated the activation of central nervous system (CNS) and the induction of puberty. Pantothenic acid, which has not been previously associated with PP, plays an active role in fatty acid metabolism and facilitates acetyl-coenzyme A entry into the TCA cycle. Therefore, TCA cycle intermediates such as citrate, cis-aconitic acid, 2-oxoglutaric acid, and succinic acid were also significantly altered between the CPP and control groups (Fig. 4C). Creatinine is linked to muscle mass, and the lower levels of urinary creatinine observed in CPP subjects could be a result of the excessive weight and relative low muscle/fat ratio caused by low physical activity (50). Cadaverine, the decarboxylation product of the amino acid lysine, can be synthesized in an inducible manner in mammalian tissues and elevated in response to an exogenous gonadotrophin (51). A significant high level of cadaverine demonstrated the occurrence of PP and the fact that CPP is gonadotrophin-dependent.

The difference between CPP and PPP conditions is whether or not HPGA is activated. As previously discussed, CPP is characterized by gonadal maturity and the release of sex hormones through activated HPGA, whereas PPP is mostly caused by exogenous steroid exposure. There are multiple potential sources from which children may be exposed to the exogenous estrogens or androgens. Exogenous estrogen contamination in the food ingested by the children and by their mothers is considered a cause of precocious puberty (52). Accidental or systemic exposure to these hormones from various sources such as hair products containing estrogen or placental extracts (53) is also a possibility. In this study, we were unable to determine the differences between endogenous steroids and exogenous steroids, although we did find some differences in amino acid metabolism. However, we found a phenomenon that the metabolic level of purine is lower in CPP compared with healthy control or PPP, including adenosine, xanthine, and glutamine in purine metabolism. Additionally, adenosine has an inhibitory effect in the CNS; the reduction in adenosine activity leads to increased activity of the neurotransmitters dopamine and glutamate (54). Carnosine is a putative neurotransmitter in the brain (55, 56), one of its central functions is the induction of hyperactivity, such as increasing spontaneous activity and increasing plasma corticosterone concentration in chicks, and it has recently been reported to be a stimulant for the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (56, 57). Carnosine regulates brain function and/or behaviors by activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and enhancing production of NO via constitutive NOS (55). The function of β-alanine and histidine are the reverse of carnosine (56), and this also explains the decrease of both concentrations in CPP. The acute degradation of dipeptides could not occur in the brain; thus, dipeptidyl structure-carnosine is important for the induction of hyperactivity (57). It was reported that pyrimidine-rich initiator is one of the multiple promoter elements in the human GnRH receptor gene, and these promoters are responsible for the multiplicity of regulation of human reproductive functions (58). The significant decrease of pyrimidine may be the occurrence of CPP. Adrenocorticotropic hormone, a polypeptide tropic hormone produced and secreted by the anterior pituitary gland, is an important component of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and is often produced in response to biological stress (along with corticotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus). Increased excretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, in turn, depletes both vitamin C and pantothenic acid from the glands (59, 60), and stimulates the adrenal cortex into cortisol secretion (59). Therefore, we believe that increased adrenal medullary hormone secretion and enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity are major metabolic regulatory pathways disturbed in CPP subjects. These important physiological alterations are indicative of activated HPGA, increased release of gonadal hormones, and subsequent development of puberty along with secondary sexual characteristics. These alterations are in accordance with the urine hormone analysis results listed in Table III showing that LH and FSH levels increased significantly in all CPP girls after the GnRH stimulation test, confirming the central origin of precocious pubertal development (61).

Effect of Triptorelin on Metabolome

Triptorelin is a long acting GnRH agonist preparation, differing from native GnRH by amino acid substitutions that increase the resistance of the drug to metabolism, prolong its action, and elevate its potency. GnRH secretion is a physiological pulsatile process in nature, and the gonadotropes require this intermittent form to secrete gonadotropins in a physiologic pattern. Therefore, continuous stimulation of the pituitary desensitizes gonadotropin secretion, down-regulates GnRH receptors, and suppresses a pathologic function of HPGA, resulting in gonadal suppression (7). As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the majority of those metabolites in catecholamines and serotonin pathways, such as tyrosine, vanillylmandelic acid, homovanillic acid, 5-hydroxykynurenamine, 5-hydroxyindoleacetylglycine, and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid were normalized as a result of triptorelin treatment. The recovery of these metabolites indicated the catecholamines, and serotonin pathways were down-regulated, possibly leading to decreased adrenal medullary hormone secretion and sympathetic nervous system activity.

Gut Microbiota Variation

We observed that there were significant alterations in the urinary excretion levels of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, indole-5,6-quinone, indoleacetic acid, 4-hydroxyphenypyruvic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, 5-hydroxytryptophan, 5-hydroxykynurenamine, and 18-hydroxycortisol in the CPP group, all of which are believed to be associated with gut microbial-mammalian cometabolism (27). This suggests that the development of the CPP condition may involve an alteration in symbiotic gut microbial composition. Additionally, we observed that the PP subjects were more likely to be overweight (Table I) than their age-matched counterparts in the control group, although their body weights were not up to the standard of obesity. There is strong evidence that chronic life stress directly impacts gastrointestinal function in animals and humans (62–64) and increases the activity of both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathoadrenal system (65). As emerging evidence demonstrates the influence of gut microbiota on the development, behavior, and function of CNS (66), it is increasingly important to understand the intricate relationship between CNS, gut microbiota, and metabolic phenotypes in the development of precocious puberty.

The aim of this study was to search for potential urinary metabolite markers for PP. However, there are several limitations in the current MS-based study. First, the medium-sized cohort of PP subjects (n = 106) used in this study may not be sufficiently large to conclusively obtain and verify viable biomarkers. Second, differential variables detected were partially identified and validated using the current protocol. More biomarkers and metabolic information can be obtained with an improved metabolite identification capability in future studies.

In summary, we applied a UPLC-QTOFMS and GC-TOFMS-based metabolomic profiling approach, in conjunction with multivariate statistical techniques, to identify metabolite markers in precocious puberty subjects relative to their age-matched normal counterparts. This noninvasive approach revealed several key metabolic pathways involved in precocious puberty and visualized time-dependent metabolomic alterations resulting from drug intervention. The results highlight the roles of up-regulated catecholamine and 5-HT metabolic pathways as well as the interplay among CNS, gut microbiota, energy metabolism, and the obese phenotype in precocious puberty subjects. The urinary metabolite markers identified in the study provide a potential alternative diagnostic and stratification approach, with high applicability, for the clinical management of PP.

Footnotes

* This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 30672636, National Science and Technology Major Project Grant 2009ZX10004-601, and National Basic Research Program Grant 2007CB914700.

This article contains supplemental text, Tables 1–6, and Figs. 1–4.

This article contains supplemental text, Tables 1–6, and Figs. 1–4.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- HPGA

- hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

- PP

- precocious puberty

- GnRH

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- LH

- luteinizing hormones

- FSH

- follicle-stimulating hormones

- CPP

- central precocious puberty

- PPP

- peripheral precocious puberty

- UPLC-QTOFMS

- ultra performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight-mass spectrometry

- GC-TOF-MS

- gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- PLS-DA

- partial least squares discriminant analysis

- OPLS-DA

- orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis

- VIP

- variable importance in the projection

- ROC

- receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

- area under the curve

- CV

- cross-validation

- CNS

- central nervous system

- 5-HT

- serotonin

- BSTFA

- Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide

- TMCS

- Trimethylchlorosilane.

REFERENCES

- 1. Partsch C. J., Heger S., Sippell W. G. (2002) Management and outcome of central precocious puberty. Clin. Endocrinol. 56, 129–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein K. O. (1999) Precocious puberty: Who has it? Who should be treated? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 84, 411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bridges N. A. (2001) In Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology (Brook C. G., Hindmarsh P., eds) pp. 165–179, Blackwell Science, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petridou E., Syrigou E., Toupadaki N., Zavitsanos X., Willett W., Trichopoulos D. (1996) Determinants of age at menarche as early life predictors of breast cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 68, 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bridges N. A., Christopher J. A., Hindmarsh P. C., Brook C. G. (1994) Sexual precocity: Sex incidence and aetiology. Arch. Dis. Child 70, 116–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lebrethon M. C., Bourguignon J. P. (2000) Management of central isosexual precocity: Diagnosis, treatment, outcome. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 12, 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Conn P. M., Crowley W. F., Jr. (1994) Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and its analogs. Annu. Rev. Med. 45, 391–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson A. C., Meethal S. V., Bowen R. L., Atwood C. S. (2007) Leuprolide acetate: A drug of diverse clinical applications. Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 16, 1851–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martínez-Aguayo A., Hernández M. I., Beas F., Iñiguez G., Avila A., Sovino H., Bravo E., Cassorla F. (2006) Treatment of central precocious puberty with triptorelin 11.25 mg depot formulation. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carel J. C., Blumberg J., Seymour C., Adamsbaum C., Lahlou N. (2006) Three-month sustained-release triptorelin (11.25 mg) in the treatment of central precocious puberty. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 154, 119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poomthavorn P., Khlairit P., Mahachoklertwattana P. (2009) Subcutaneous gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (triptorelin) test for diagnosing precocious puberty. Hormone Res. 72, 114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parker K. L., Baensbailon R. G., Lee P. A. (1991) Depot leuprolide acetate dosage for sexual precocity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 73, 50–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cavallo A., Richards G. E., Busey S., Michaels S. E. (1995) A simplified gonadotropin-releasing-hormone test for precocious puberty. Clin. Endocrinol. 42, 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawson M. L., Cohen N. (1999) A single sample subcutaneous luteinizing hormone (LH)-releasing hormone (LHRH) stimulation test for monitoring LH suppression in children with central precocious puberty receiving LHRH agonists. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 84, 4536–4540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Houk C. P., Kunselman A. R., Lee P. A. (2008) The diagnostic value of a brief GnRH analogue stimulation test in girls with central precocious puberty: A single 30-minute post-stimulation LH sample is adequate. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metabol. 21, 1113–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Houk C. P., Kunselman A. R., Lee P. A. (2009) Adequacy of a single unstimulated luteinizing hormone level to diagnose central precocious puberty in girls. Pediatrics 123, e1059–e1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schoeters G., Den Hond E., Dhooge W., van Larebeke N., Leijs M. (2008) Endocrine disruptors and abnormalities of pubertal development. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 102, 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraley G. S., Kuenzel W. J. (1993) Precocious puberty in chicks (Gallus domesticus) induced by central injections of neuropeptide-Y. Life Sci. 52, 1649–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunn W. B., Bailey N. J., Johnson H. E. (2005) Measuring the metabolome: Current analytical technologies. Analyst 130, 606–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qiu Y., Cai G., Su M., Chen T., Zheng X., Xu Y., Ni Y., Zhao A., Xu L. X., Cai S., Jia W. (2009) Serum metabolite profiling of human colorectal cancer using GC-TOFMS and UPLC-QTOFMS. J. Proteome Res. 8, 4844–4850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicholson J. K., Lindon J. C., Holmes E. (1999) ‘Metabonomics’: Understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data. Xenobiotica 29, 1181–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Allen J., Davey H. M., Broadhurst D., Heald J. K., Rowland J. J., Oliver S. G., Kell D. B. (2003) High-throughput classification of yeast mutants for functional genomics using metabolic footprinting. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 692–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bao Y., Zhao T., Wang X., Qiu Y., Su M., Jia W. (2009) Metabonomic variations in the drug-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and healthy volunteers. J. Proteome Res. 8, 1623–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamel A., Prakash C. (2006) High performance liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization/tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC/API/MS/MS) in drug metabolism and toxicology. Curr. Drug Metab. 7, 837–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holmes E., Nicholson J. K., Tranter G. (2001) Metabonomic characterization of genetic variations in toxicological and metabolic responses using probabilistic neural networks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fiehn O. (2003) Metabolic networks of Cucurbita maxima phloem. Phytochemistry 62, 875–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li M., Wang B., Zhang M., Rantalainen M., Wang S., Zhou H., Zhang Y., Shen J., Pang X., Zhang M., Wei H., Chen Y., Lu H., Zuo J., Su M., Qiu Y., Jia W., Xiao C., Smith L. M., Yang S., Holmes E., Tang H., Zhao G., Nicholson J. K., Li L., Zhao L. (2008) Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2117–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Solanky K. S., Bailey N. J., Beckwith-Hall B. M., Bingham S., Davis A., Holmes E., Nicholson J. K., Cassidy A. (2005) Biofluid 1H NMR-based metabonomic techniques in nutrition research: Metabolic effects of dietary isoflavones in humans. J. Nutr. Biochem. 16, 236–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xie G., Ye M., Wang Y., Ni Y., Su M., Huang H., Qiu M., Zhao A., Zheng X., Chen T., Jia W. (2009) Characterization of Pu-erh tea using chemical and metabolic profiling approaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 3046–3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Williams C. T. (1883) The relations of phthisis and albuminuria. Br. Med. J. 2, 1224–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ni Y., Su M., Qiu Y., Chen M., Liu Y., Zhao A., Jia W. (2007) Metabolic profiling using combined GC-MS and LC-MS provides a systems understanding of aristolochic acid-induced nephrotoxicity in rat. FEBS Lett. 581, 707–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Storey J. D. (2002) A direct approach to false discovery rates. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 64, 479–498 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei J., Xie G. X., Zhou Z. T., Shi P., Qiu Y. P., Zheng X. J., Chen T. L., Su M. M., Zhao A. H., Jia W. (2010) Salivary metabolite signatures of oral cancer and leukoplakia. Int. J. Cancer 129, 2207–2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Y., St John M. A., Zhou X., Kim Y., Sinha U., Jordan R. C., Eisele D., Abemayor E., Elashoff D., Park N. H., Wong D. T. (2004) Salivary transcriptome diagnostics for oral cancer detection. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 8442–8450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ni Y., Su M., Lin J., Wang X., Qiu Y., Zhao A., Chen T., Jia W. (2008) Metabolic profiling reveals disorder of amino acid metabolism in four brain regions from a rat model of chronic unpredictable mild stress. FEBS Lett. 582, 2627–2636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trelstar Compound Summary, NCBI PubChem. http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=47207906&viewopt=PubChem&namedisopt=Alphabetic.

- 38. Müller F. O., Terblanchè J., Schall R., van Zyl Smit R., Tucker T., Marais K., Groenewoud G., Porchet H. C., Weiner M., Hawarden D. (1997) Pharmacokinetics of triptorelin after intravenous bolus administration in healthy males and in males with renal or hepatic insufficiency. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44, 335–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Izvolskaia M., Duittoz A. H., Tillet Y., Ugrumov M. V. (2009) The influence of catecholamine on the migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-producing neurons in the rat foetuses. Brain Struct. Funct. 213, 289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Izvol'skaia M. S., Adamskaia E. I., Voronova S. N., Duittoz A., Tillet I. (2005) Catecholamines in regulation of development of GnRH neurons of rat fetuses. Ontogenez 36, 440–448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Helena C. V., Franci C. R., Anselmo-Franci J. A. (2002) Luteinizing hormone and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone secretion is under locus coeruleus control in female rats. Brain Res 955, 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ivanisević-Milovanović O. K., Pantic V., Demajo M., Loncar-Stevanović H. (1993) Catecholamines in hypothalamus, ovaries and uteri of rats with precocious puberty. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 16, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim H. S., Yumkham S., Choi J. H., Son G. H., Kim K., Ryu S. H., Suh P. G. (2006) Serotonin stimulates GnRH secretion through the c-Src-PLC gamma1 pathway in GT1–7 hypothalamic cells. J. Endocrinol. 190, 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chaouloff F. (2000) Serotonin, stress and corticoids. J. Psychopharmacol. 14, 139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kang Y. M., Chen J. Y., Ouyang W., Qiao J. T., Reyes-Vazquez C., Dafny N. (2004) Serotonin modulates hypothalamic neuronal activity. Int. J. Neurosci. 114, 299–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weinberg R. J. (1999) Glutamate: An excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian CNS. Brain Res. Bull. 50, 353–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parent A. S., Matagne V., Bourguignon J. P. (2005) Control of puberty by excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters and its clinical implications. Endocrine 28, 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brann D. W., Mahesh V. B. (1995) Glutamate: A major neuroendocrine excitatory signal mediating steroid effects on gonadotropin-secretion. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 53, 325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hoffmann G. F., Seppel C. K., Holmes B., Mitchell L., Christen H. J., Hanefeld F., Rating D., Nyhan W. L. (1993) Quantitative organic-acid analysis in cerebrospinal-fluid and plasma: Reference values in a pediatric population. J. Chromatogr. B 617, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Waldram A., Holmes E., Wang Y., Rantalainen M., Wilson I. D., Tuohy K. M., McCartney A. L., Gibson G. R., Nicholson J. K. (2009) Top-down systems biology modeling of host metabotype-microbiome associations in obese rodents. J. Proteome Res. 8, 2361–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Andersson A. C., Henningsson S. (1980) Biosynthesis and accumulation of cadaverine and putrescine in rat ovary after administration of human chorionic gonadotrophin. Acta Endocrinol. 95, 237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sáenz de Rodríguez C. A., Bongiovanni A. M., Conde de Borrego L. (1985) An epidemic of precocious development in Puerto-Rican children. J. Pediatr. 107, 393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Eugster E. A. (2009) Peripheral precocious puberty: Causes and current management. Hormone Res. 71, 64–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dutra G. P., Ottoni G. L., Lara D. R., Bogo M. R. (2010) Lower frequency of the low activity adenosine deaminase allelic variant (ADA1*2) in schizophrenic patients. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 32, 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tomonaga S., Tachibana T., Takahashi H., Sato M., Denbow D. M., Furuse M. (2005) Nitric oxide involves in carnosine-induced hyperactivity in chicks. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 524, 84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tomonaga S., Tachibana T., Takagi T., Saito E. S., Zhang R., Denbow D. M., Furuse M. (2004) Effect of central administration of carnosine and its constituents on behaviors in chicks. Brain Res. Bull. 63, 75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tsuneyoshi Y., Tomonaga S., Asechi M., Morishita K., Denbow D. M., Furuse M. (2007) Central administration of dipeptides, beta-alanyl-BCAAs, induces hyperactivity in chicks. BMC Neurosci. 8, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ngan E. S., Leung P. C., Chow B. K. (2000) Identification of an upstream promoter in the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270, 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hurley L. S., Morgan A. F. (1952) Carbohydrate metabolism and adrenal cortical function in the pantothenic acid-deficient rat. J. Biochem. 195, 583–590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Raszyk J. (1975) Effect of nutrition on adreno cortical activity. Ceskoslovenska Fysiologie 24, 51–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Iughetti L., Predieri B., Cobellis L., Luisi S., Luisi M., Forese S., Petraglia F., Bernasconi S. (2002) High serum allopregnanolone levels in girls with precocious puberty. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 87, 2262–2265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lutgendorff F., Akkermans L. M., Söderholm J. D. (2008) The role of microbiota and probiotics in stress-induced gastro-intestinal damage. Curr. Mol. Med. 8, 282–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. O'Mahony S. M., Marchesi J. R., Scully P., Codling C., Ceolho A. M., Quigley E. M., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G. (2009) Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: Implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 263–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Caso J. R., Leza J. C., Menchén L. (2008) The effects of physical and psychological stress on the gastro-intestinal tract: lessons from animal models. Curr. Mol. Med. 8, 299–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Noble R. E. (2002) Diagnosis of stress. Metabolism 51, 37–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sudo N., Chida Y., Aiba Y., Sonoda J., Oyama N., Yu X. N., Kubo C., Koga Y. (2004) Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J. Physiol. 558, 263–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]