Abstract

Background

The transfemoral approach is an extensile surgical approach that is performed routinely to facilitate cement and implant removal and improve exposure for revision stem implantation. Previous studies have looked at clinical results of small patient groups. The factors associated with fixation failure of cementless revision stems when using this approach have not been examined.

Questions/purposes

We determined (1) the clinical results and (2) complications of the transfemoral approach and (3) factors associated with fixation failure of revision stems when using the transfemoral approach.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively examined all our patients in whom femoral stem revision was performed through a transfemoral approach between December 1998 and April 2004 and for whom a minimal followup of 2 years was available. One hundred patients were available for this study. The mean (± SD) postoperative followup was 5 years (± 1.64 years).

Results

The average Harris hip score improved from 45.2 (± 14.02) preoperatively to 83.4 (± 11.86) at final followup. Complete radiographic bony consolidation of the osteotomy site was observed in 95% of patients. Dislocations occurred in 9% of patients. Four revision stem fixation failures were observed, all occurring in patients with primary three-point fixation. Three-point fixation was associated with short osteotomy flaps and long revision stems.

Conclusions

The transfemoral approach is associated with a high rate of osteotomy flap bony healing and good clinical results. When using the transfemoral approach, a long osteotomy flap should be performed and the shortest possible revision stem should be implanted.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Femoral stem revision can be a challenging procedure when an osseointegrated cementless stem or a well-cemented stem has to be explanted or when severe bony defects are present [11, 15, 23, 24]. Revision through an endofemoral approach may result in inadvertent fractures or in incomplete cement removal [18, 20, 24]. Revision performed through the endofemoral approach in a varus-remodeled femur, which often is observed with a loosened femoral stem, may be associated with eccentric femoral reaming and resulting perforation or fracture [21].

Extensile surgical approaches have been described to facilitate cement and implant removal and to improve exposure for revision stem implantation [23, 24]. The standard trochanteric osteotomy and the trochanteric slide osteotomy have been associated with a high incidence of major complications, such as osteotomy nonunion, osteotomy fragment migration, trochanteric bursitis from fixation material, and persistent hip abductor weakness [1, 7]. The extended trochanteric osteotomy (ETO), first described by Younger et al. [27], is associated with a more predictable osteotomy union and allows at the same time better access to the femoral canal [11, 14, 17, 27]. The osteotomy of the transfemoral approach as described by Wagner and Wagner [26] is broader than the ETO and involves 1/2 of the femoral shaft circumference (in contrast to 1/3 of the femoral shaft circumference in ETO). This broader osteotomy of the transfemoral approach has been postulated to be advantageous in the implantation of a cementless revision stem with a diaphyseal mode of fixation [6, 18, 26].

The primary aim of our study is to report the clinical results as reflected by improvement in the Harris hip score [9] and the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score [16] and the incidence of complications when using the transfemoral approach for implanting a cementless modular straight femoral revision stem. We also examined which factors were associated with fixation failure of the revision stem when the transfemoral approach was used.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively examined all our patients in whom femoral stem revision was performed through a transfemoral approach between December 1998 and April 2004 and for whom a minimal followup of 2 years was available. The sole exclusion criterion was the absence of a minimal followup of 2 years; 26 patients were excluded, including 11 patients who died and 15 who did not return for followup. This left 100 patients available for the study. The mean (± SD) postoperative followup was 5 years (± 1.64 years).

The average age of patients was 70 years (± 9.4 years). Forty-six patients were male and 54 were female. Causes for revision included aseptic femoral stem loosening in 40 patients, massive bone loss caused by granulomatous response in 27 patients, revision for recurrent dislocations in three patients, and revision for aseptic cup loosening in 30 patients where the well-fixed femoral stem was also simultaneously revised. Thirteen of the 40 revisions for aseptic femoral stem loosening had already had a prior femoral stem revision.

Indications for the transfemoral approach included presence of a curved femur in 45 patients, anticipated difficulty in complete removal of a preexisting thick cement mantle in 31 patients, anticipated difficulty in removal of a well-fixed osseointegrated femoral stem in 14 patients, and presence of severe bony defects in 10 patients. Two surgeons (PLB, MG) performed all the revisions using the same operative technique. All revisions were performed through a posterior approach to the hip, and in all these patients, a semicircular lateral femoral cortex osteotomy was performed where the osteotomy fragment was left pediculated to the vastus lateralis muscle [26]. The osteotomy length varied from patient to patient. The surgeon planned the osteotomy length during preoperative templating, aiming at good accessibility to the to-be-explanted prosthesis stem or to the distal cement. The distal level of the osteotomy was planned in all patients proximal to the femoral isthmus to ensure the femoral isthmus was not damaged so that initial stem fixation would be possible in the femoral isthmic zone. The distal level of the osteotomy generally was planned at the level of the distal extent of the tip of the stem if this was proximal to the femoral isthmus; otherwise, it was planned just proximal to the most proximal extent of the femoral isthmus. In some patients, the surgeon planned osteotomy length to allow correction of proximal deviation of the femoral axis. The Revitan® modular straight cementless revision stem (Zimmer GmbH, Winterthur, Switzerland) was used for revision surgery. The distal component of this stem has a round profile with eight longitudinal cutting fins and a conical gradient of 2°, and the conical anchoring bed in the isthmic region of the femur is prepared with reamers. In all patients, the surgeon’s aim was to achieve initial fixation of the revision stem through circular press-fit anchoring in the femoral isthmic zone. Bone graft was not used in any of these patients. The osteotomy flap was readapted using cerclage wires. Immediate full weightbearing was allowed postoperatively in all patients.

All patients were examined clinically and radiographically. Preoperative clinical data and intraoperative data were collected from medical records. Clinical assessment was performed using the Harris hip score [9] and the Merle d’Aubigne and Postel score [16]. Radiographic assessment was performed on standardized AP and lateral radiographs of the hip and femur by one observer (HPS) blinded to the results. All the radiographic quantitative measurements were performed using the EvalNet software tool (LeadTools®; LEAD Technologies, Inc, Charlotte, NC, USA). All radiographic measurements were corrected for magnification using the prosthetic head diameter as a reference. The preoperative bony defects were classified according to the classification of Della Valle and Paprosky [4] (Table 1). The preoperative morphologic features of the femur were examined on the AP view of the femur by drawing a centromedullary line in the diaphyseal zone. The femur was defined as curved when the extension of this line was not central at the level of the tip of the lesser trochanter (Table 1). The length of the osteotomy flap (tip of greater trochanter to distal end of the bony flap) was measured on the immediate postoperative AP radiograph. Presence and size of a gap between the osteotomy flap and distal femur were documented on the immediate postoperative radiograph. Type of initial fixation of the revision stem (press-fit anchoring in diaphyseal zone [Fig. 1] or three-point fixation [Fig. 2]) also was evaluated on the immediate postoperative AP radiograph. For the radiographic assessment, press-fit fixation was defined as presence of a cross-sectional area of absolute bone-implant-bone contact in the femur isthmus on the AP radiograph. The fixation was considered to be a three-point fixation when the AP radiograph did not show a cross-sectional area of absolute bone-implant-bone contact in the femur isthmus. Postoperative radiographs were examined for bony consolidation of the osteotomy gap. The gap was classified as absent, slight (< 5 mm), moderate (5–10 mm), and large (> 10 mm).

Table 1.

Preoperative radiographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Morphologic features of femur (on AP radiograph) | |

| Straight femur | 54 |

| Curved femur | 46 |

| Femoral deficiency classification according to Della Valle and Paprosky [4] | |

| Type 1 | 38 |

| Type 2 | 24 |

| Type 3A | 24 |

| Type 3B | 11 |

| Type 4 | 3 |

Fig. 1A–B.

(A) An AP radiograph shows a revision stem with press-fit anchoring in the diaphyseal zone. (B) The magnified image of the femur diaphysis shows a cross-sectional area of absolute bone-implant-bone contact in the femur isthmus between the black arrows.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) An AP radiograph shows a revision stem with three-point fixation. (B) The magnified image of the femur diaphysis shows the revision stem does not have a cross-sectional area of absolute bone-implant-bone contact in the femur isthmus. The black arrows show the region where the fins of the revision stem come in contact with bone; the white arrows show lack of implant-bone contact.

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (Version 2.12.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The paired t test was used for comparing preoperative and postoperative clinical results. The chi square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Logistic regression was performed to identify factors influencing type of initial fixation of the revision stem.

Results

The average Harris hip score improved (p < 0.001) from 45.2 (± 14.02) preoperatively to 83.4 (± 11.86) at final followup. The average Merle d’Aubigne and Postel score improved (p < 0.001) from 10.9 (± 2.32) preoperatively to 15.9 (± 1.75) at final followup. The Merle d’Aubigne and Postel score subgroup for walking and stability improved (p < 0.001) from 3.4 (± 1.11) preoperatively to 4.6 (± 1.21) at final followup. The Merle d’Aubigne and Postel subgroup for pain improved from 2.9 to 5.7.

Dislocations occurred in nine patients. Two dislocations occurred as a result of femoral stem rotational instability (femoral stem was revised in both patients). One dislocation occurred after secondary subsidence of the femoral stem and a longer proximal component of modular stem was implanted. One dislocation was attributable to poor cup positioning, which was revised. One dislocation was treated surgically with implantation of a longer head to increase muscle tensioning (this dislocation was not associated with stem subsidence), and four dislocations could be treated nonoperatively (two of these dislocations occurred after a fall; no clear cause for dislocation could be identified in the other two). Besides these complications, there was also another case of stem fixation failure where the stem had to be reimplanted. All four stem-related complications were observed in patients where the primary fixation was a three-point fixation. Logistic regression analysis showed longer revision stems (p = 0.00149) and shorter osteotomy flaps (p = 0.0378) were associated with three-point fixation with odds ratios of 1.03 and 0.97, respectively. Immediate postoperative AP radiographs showed an initial press-fit fixation of the revision stem in 79 patients and an initial three-point fixation of the revision stem in 21 patients. The average length of the osteotomy flap was 145 mm (± 18.9 mm) and the average length of femoral stem was 210 mm (± 22.7 mm). In the 21 patients with initial three-point fixation, the average length of the revision femoral stem was longer (218 mm versus 208 mm) and the average length of the osteotomy flap was shorter (141 mm versus 147 mm) than in the patients with initial press-fit fixation. Postoperative radiographs showed no gap between the osteotomy flap and the distal femur in 57 patients, a slight gap (< 5 mm) in 21 patients, a moderate gap (5–10 mm) in 15 patients, and a large gap (> 10 mm) in seven patients. At final followup, complete radiographic bony consolidation of the osteotomy site was observed in 95 patients. In the remaining five patients without radiographic bony consolidation, the initial gap at the osteotomy site was always less than 5 mm.

Discussion

The removal of an osseointegrated cementless stem, a well-cemented femur stem, the presence of severe bony defects, or a curved femur may necessitate an extensile surgical approach at revision surgery to avoid inadvertent complications, such as iatrogenic fractures, incomplete removal of cement, or poor positioning of the revision stem [11, 20, 24]. One of the approaches to circumvent such problems is the transfemoral approach [6, 18, 26]. In this study, we report the clinical results and complications of the transfemoral approach and the factors associated with fixation failure of the cementless modular straight revision stem implanted through a transfemoral approach.

We acknowledge limitations to the study. First, due to the inclusion criterion of minimum 2 years’ followup, a relatively large number of patients were excluded from this study. We were faced with this problem as we included all cases of transfemoral approach with various reasons for revision surgery, without stratifying the selection based on age of the patients or the general condition/comorbidities at the time of operation. Second, we used a nonvalidated definition for radiographic assessment of presence or absence of initial press-fit fixation of the revision stem. To our knowledge, no widely used method exists for radiographic assessment of type of initial fixation of femoral stems. Although we are aware the term “press-fit” in the sense of genuine “mechanical joining” cannot be evaluated on plain radiographs, we firmly believe a radiographic differentiation between three-point fixation and isthmic bone-implant-bone anchoring is possible.

The clinical results of our patient group at an average of 5 years followup are comparable to the results described by others using other approaches in femoral stem revisions [2, 17, 19]. Our results show the creation of the broader osteotomy flap in the transfemoral approach does not have a negative influence on the midterm clinical results of femur stem revision surgery. The good clinical results can be attributed to the high percentage of consolidation of the osteotomy flap. In our patient group, the osteotomy site showed radiographic bony consolidation in 95% of patients. There was no secondary displacement of the osteotomy flap in the remaining five patients without radiographic bony consolidation at final followup, leading us to conclude a fibrous fixation of the flap had taken place in these patients. Others have described similar high union rates [8, 10, 12, 26]. A slightly higher consolidation rate (98.5%) of the osteotomy flap with the transfemoral approach was described in a study on the transfemoral osteotomy using a curved modular revision stem [6]. The authors of that study postulated the fixation of the bony flap with cerclage wires led to improved results when compared with the traditional Wagner transfemoral approach where suture-supported readaptation of the bony flap was performed.

In our patient group, the dislocation rate was 9%, which is comparable to the dislocation rate described by others for femur stem revisions [3, 17, 22]. In our patient group, four of nine dislocations were implant-related (three femoral implant-related and one acetabular implant-related). The higher rate of dislocations in revision arthroplasty compared with primary arthroplasty is mainly a result of the soft tissue dysfunction after repeated surgery. Theoretically, a gap between the osteotomy flap and distal femur after a transfemoral approach may be associated with a higher dislocation rate as this is associated with a proximalization of the greater trochanter and decreased strength of the abductor muscles. The use of a straight femur revision stem can hinder a perfect anatomic reduction of the osteotomy flap even after contouring of the endomedullary surface of the flap. A gap between the osteotomy fragment and distal femur was observed in the immediate postoperative radiographs in 47% of our patients; however, only two of nine patients who experienced dislocation had a gap between the osteotomy fragment and distal femur. We postulate the use of the straight femur stem probably also leads to a lateralization of the osteotomy flap and tensioning of the abductor muscles, thereby negating the effect of trochanter proximalization.

Our study clearly shows a short osteotomy flap and a long revision stem are associated with an initial three-point stem fixation (Fig. 3). Initial implant stabilization through press-fit fixation with bone-implant-bone contact in the isthmic zone is desirable when a conical straight revision stem is used. An initial three-point fixation is frequently associated with implantation of an underdimensioned stem, increasing the risk of stem rotational instability and consequent stem subsidence. Correct sizing of the stem and a tight diaphyseal fit also are important when using other implants such as an extensively porous-coated straight stem. Some authors using extensively porous-coated femoral revision stems have reported failure of stem fixations occurring when the femoral stem was undersized [5, 13]. A biomechanical study comparing a proximal porous-coated and an extensively porous-coated stem showed the extent of the porous coating on the stem did not have an effect on the rotational stability of the femoral component and superior rotational stability was accomplished only when a tight diaphyseal fixation was achieved [25]. All four stem-related failures in our patient group were seen in patients where initial fixation was achieved through three-point fixation. Our study shows the mere performance of a broader osteotomy flap does not protect against an initial three-point fixation of the revision stem. We observed an initial three-point fixation in 21% of our patient group. This high percentage of initial three-point stem fixation can be attributed to the high percentage of patients with curved femurs (45%) where press-fit diaphyseal fixation cannot be reliably achieved when using a too-long straight revision stem. We therefore recommend the shortest possible cementless straight revision stems be used when initial press-fit fixation is desired in the diaphyseal region and the osteotomy flap is planned as long as possible to allow good access to the isthmic region for perfect press-fit preparation and stem implantation.

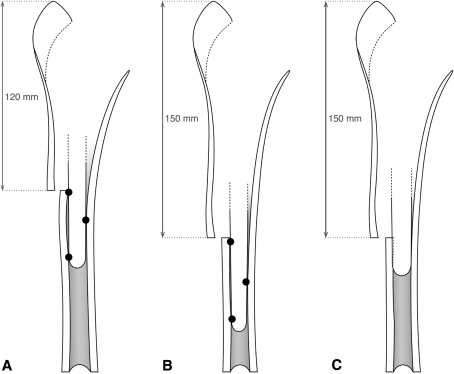

Fig. 3A–C.

(A) In a curved femur, a short osteotomy flap leads to a three-point fixation when using a straight revision stem. In such cases, the distal extent of the osteotomy should be performed close to the femoral isthmus to allow a perfect conical preparation of the femoral isthmus. (B) A too-long fixation stretch in the femoral diaphysis also leads to three-point fixation when using a straight revision stem despite an adequate osteotomy flap length. (C) Press-fit fixation is achieved when the osteotomy flap is sufficiently long and when a short stem is used. The distal extent of the osteotomy is performed close to the femoral isthmus without damaging the isthmus. A bone-implant-bone contact zone height of 4 to 5 cm is sufficient for primary stability of the straight revision stem.

The transfemoral osteotomy is associated with a high rate of osteotomy flap healing and good clinical results at an average of 5 years followup. An initial three-point fixation of the cementless straight conical revision stem that may be associated with rotational instability and failure of stem fixation can be avoided by using the shortest possible stem and performing a sufficiently long osteotomy flap.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aude Tavenard for the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at Polyclinique Sévigné.

References

- 1.Amstutz HC, Maki S. Complications of trochanteric osteotomy in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:214–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boisgard S, Moreau PE, Tixier H, Levai JP. Bone reconstruction, leg length discrepancy, and dislocation rate in 52 Wagner revision total hip arthroplasties at 44-month follow-up] [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2001;87:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WM, McAuley JP, Engh CA, Jr, Hopper RH, Jr, Engh CA. Extended slide trochanteric osteotomy for revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1215–1219. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Della Valle CJ, Paprosky WG. The femur in revision total hip arthroplasty evaluation and classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;420:55–62. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engh CA, Jr, Ellis TJ, Koralewicz LM, McAuley JP, Engh CA., Sr Extensively porous-coated femoral revision for severe femoral bone loss. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:955–960. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.35794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink B, Grossmann A, Schubring S, Schulz M, Fuerst M. A modified transfemoral approach using modular cementless revision stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:105–114. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180986170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel A, Booth RE, Jr, Balderston RA, Cohn J, Rothman RH. Complications of trochanteric osteotomy: long-term implications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;288:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grünig R, Morscher E, Ochsner PE. Three- to 7-year results with the uncemented SL femoral revision prosthesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116:187–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00393708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartwig CH, Böhm P, Czech U, Reize P, Küsswetter W. The Wagner revision stem in alloarthroplasty of the hip. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1996;115:5–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00453209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jando VT, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP. Trochanteric osteotomies in revision total hip arthroplasty: contemporary techniques and results. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:143–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolstad K, Adalberth G, Mallmin H, Milbrink J, Sahlstedt B. The Wagner revision stem for severe osteolysis: 31 hips followed for 1.5–5 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:541–544. doi: 10.3109/17453679608997752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnamurthy AB, MacDonald SJ, Paprosky WG. 5- to 13-year follow-up study on cementless femoral components in revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:839–847. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mardones R, Gonzalez C, Cabanela ME, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Extended femoral osteotomy for revision of hip arthroplasty: results and complications. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masri BA, Mitchell PA, Duncan CP. Removal of solidly fixed implants during revision hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:18–27. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merle D’Aubigné R. Numerical classification of the function of the hip. 1970 [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1990;76:371–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miner TM, Momberger NG, Chong D, Paprosky WL. The extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision hip arthroplasty: a critical review of 166 cases at mean 3-year, 9-month follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(8 suppl 1):188–194. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.29385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nozawa M, Shitoto K, Mastuda K, Maezawa K, Yasuma M, Kurosawa H. Transfemoral approach for revision total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:288–290. doi: 10.1007/s00402-001-0384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paprosky WG, Greidanus NV, Antoniou J. Minimum 10-year-results of extensively porous-coated stems in revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;369:230–242. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199912000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paprosky WG, Martin EL. Removal of well-fixed femoral and acetabular components. Am J Orthop. 2002;31:476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paprosky WG, Sporer SM. Controlled femoral fracture: easy in. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(3 suppl 1):91–93. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paprosky WG, Weeden SH, Bowling JW., Jr Component removal in revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;393:181–193. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters PC, Jr, Head WC, Emerson RH., Jr An extended trochanteric osteotomy for revision total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:158–159. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B1.8110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schurman DJ, Maloney WJ. Segmental cement extraction at revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;285:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiyama H, Whiteside LA, Engh CA. Torsional fixation of the femoral component in total hip arthroplasty: the effect of surgical press-fit technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:187–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner M, Wagner H. [The transfemoral approach for revision of total hip replacement] [in German. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 1999;11:278–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02593992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Younger TI, Bradford MS, Magnus RE, Paprosky WG. Extended proximal femoral osteotomy: a new technique for femoral revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:329–338. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]