Abtract

BACKGROUND

Incarceration is associated with poor health and high costs. Given the dramatic growth in the criminal justice system’s population and associated expenses, inclusion of questions related to incarceration in national health data sets could provide essential data to researchers, clinicians and policy-makers.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate a representative sample of publically available national health data sets for their ability to be used to study the health of currently or formerly incarcerated persons and to identify opportunities to improve criminal justice questions in health data sets.

DESIGN & APPROACH

We reviewed the 36 data sets from the Society of General Internal Medicine Dataset Compendium related to individual health. Through content analysis using incarceration-related keywords, we identified data sets that could be used to study currently or formerly incarcerated persons, and we identified opportunities to improve the availability of relevant data.

KEY RESULTS

While 12 (33%) data sets returned keyword matches, none could be used to study incarcerated persons. Three (8%) could be used to study the health of formerly incarcerated individuals, but only one data set included multiple questions such as length of incarceration and age at incarceration. Missed opportunities included: (1) data sets that included current prisoners but did not record their status (10, 28%); (2) data sets that asked questions related to incarceration but did not specifically record a subject’s status as formerly incarcerated (8, 22%); and (3) longitudinal studies that dropped and/or failed to record persons who became incarcerated during the study (8, 22%).

CONCLUSIONS

Few health data sets can be used to evaluate the association between incarceration and health. Three types of changes to existing national health data sets could substantially expand the available data, including: recording incarceration status for study participants who are incarcerated; recording subjects’ history of incarceration when this data is already being collected; and expanding incarceration-related questions in studies that already record incarceration history.

KEY WORDS: incarceration, prisoner, data, health, disparities

INTRODUCTION

Incarceration has become an increasingly common experience for US Americans; approximately 6 million Americans are currently or have been formerly incarcerated in prisons,1,2 and nearly 12 million Americans cycle through jails annually.3–6 If current incarceration rates remain unchanged, 1 in 15 Americans born in 2001 and beyond are expected to go to prison during their lifetimes, with predictions for black and Latino men even higher (1 in 3 and 1 in 6, respectively).1 Yet, little is known about the impact of incarceration on the health of individuals, incarceration’s role as a mediator in demographic or socioeconomic health disparities, or the extent to which incarceration affects community health and contributes to high health care costs.

Emerging evidence suggests strong associations among incarceration, poor health and high health care costs.7–10 Prior to incarceration, prisoners report high rates of inadequate access to health care and adverse behavioral health risk factors, such as tobacco, alcohol, and drug use.11–14 During incarceration, prisoners have higher rates of most chronic medical conditions than age-matched non-prisoners, including diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.6,15,16 Chronic conditions and disability also appear at a younger age in prisoners than in the general population.17–20 Accordingly, prison health care costs are an increasing drain on state and federal budgets,21 costs that may remain high for former prisoners. Over 50% of former prisoners report at least one chronic health condition, 70% report past substance abuse or dependence, and 80% are unable to secure health insurance for at least 8 to 10 months following release.10 Former prisoners also have higher rates of emergency services use and mortality than other adults.16,22–24 Many of the health challenges former prisoners face are likely compounded by employment difficulties, since former prisoners generally must declare their status on job applications only to be discriminated against by employers.25 Moreover, maintaining full-time employment is markedly more difficult for former prisoners who are released with a physical health condition.10 Such employment constraints likely belie a cycle of deteriorating health and lack of access to insurance and care that could further affect mental, physical, and behavioral health, as well as community health care costs. Given the complex interdependence of incarceration and health, periods of incarceration and release are increasingly viewed as critical opportunities to deliver public health interventions aimed at improving individual and community health, and decreasing the costs of health care system-wide.12,26,27

Yet these early data exploring the relationship between incarceration and health are based on relatively few studies that are often limited by small sample sizes,28,29 regional geography,19,24 and reliance on self-report.6,16 Moreover, the primary source of national prisoner health data, the Bureau of Justice Statistics Prison and Jail Inmate Survey, incorporates limited health measures due to its emphasis on criminal justice experiences and outcomes.30 The inclusion of currently and formerly incarcerated persons in health data sets is needed to provide essential, accurate, unbiased, and relevant data to researchers, public health experts, economists, clinicians, and policy-makers. Therefore, our goal was to evaluate a representative sample of publically available national health data sets for their ability to be used to study the health of currently or formerly incarcerated persons and to identify opportunities to improve criminal justice questions in health data sets.

METHODS

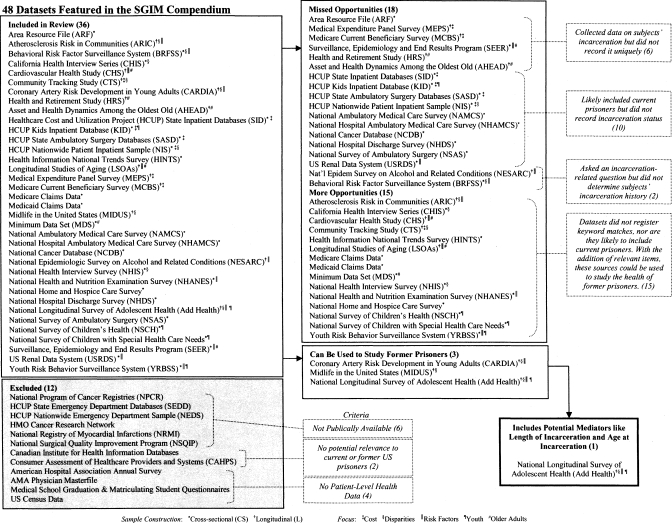

Our analysis focused on 36 of the 48 data sets contained in the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Dataset Compendium, which provides detailed information and links to national health data sets identified by the creators of the compendium (including author MS), with input from other expert researchers, as being resources of high value to generalist researchers.31 The remaining 12 data sets that we did not analyze were either not publically available (6), did not include patient-level health data (4), or were not relevant to currently or formerly incarcerated populations in the US (2), resulting in a sample of 36 data sets; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data sets included in review by inclusion of incarceration-related items. The figure shows all 48 data sets from the Society of General Internal Medicine Dataset Compendium. Twelve data sets were excluded because they were not publically available (6), contained no patient-level health data (4), or were not relevant to currently or formerly incarcerated persons (2). Of the 36 data sets included in our final sample, none could be used to study current prisoners, 3 could be used to study former prisoners, and only one of these (Add Health) represented a systematic approach to studying incarceration-related health effects in study subjects. Eighteen data sets represented missed opportunities because they collected incarceration-related data but did not record it uniquely (6), likely included current prisoners but did not record incarceration status (10), or asked an incarcerated-related question but did not determine subjects’ incarceration history (2). Fifteen data sets were not likely to include current incarceration and did not register a keyword match in our content analysis.

Using content analysis, we examined all available documentation including questionnaires, codebooks, and result summaries. We searched all documents for the keywords: Jail, Prison, Incarceration, Crime, Criminal, Convict, Victim, Police, Correctional, and Corrections. We then analyzed whether the relevant question and coding could be used to form a study sample of currently or formerly incarcerated subjects. We also determined the self-defined focus (health care costs, health disparities, older adults, youth, and/or health risk factors) and sample construction (longitudinal, cross-sectional) of each data set.

Next, we contacted all 12 longitudinal study investigators to determine whether subjects who became incarcerated during the study were dropped and/or reenrolled after release, and if study investigators documented incarceration that occurred during participation. These studies were also included in the keyword search assessment of cross-sectional data sets. The two longitudinal studies that did not respond to two e-mails and one phone call were not included in this secondary analysis.

RESULTS

Of 36 data sets reviewed, 24 (67%) were cross-sectional and 12 (33%) were longitudinal. Data sets focused on health risk factors (11, 31%), health disparities (9, 25%), health care costs (7, 19%), older adults (6, 17%), and/or youth (5, 14%); see Fig. 1.

Exclusion of Currently Incarcerated Persons

The majority of data sets (26, 72%) excluded currently incarcerated subjects in their study design. The remaining ten (28%) likely include currently incarcerated subjects: four studies from Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), the National Cancer Database (NCDB), the National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery (NSAS), the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), two National Ambulatory Medical Care surveys (NAMCS & NHAMCS), and the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). These ten studies, however, did not record subjects’ incarceration status and therefore cannot be used to assess the health or health care of currently incarcerated persons.

Inclusion and Identification of Formerly Incarcerated Persons

Three of the 36 studies reviewed (8%) included a question that could be used to define a group of former prisoners (Table 1). These included Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA), Midlife in the United States (MIDUS), and the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health). CARDIA, which focused on risk factors for coronary artery disease in young adults aged 18 to 30, recorded whether subjects had been in jail at any time during a 3-year period beginning 1 year prior to participation in the study and extending through the first longitudinal examination at year 2.28 While this measure can be used to record jail experience, CARDIA investigators did not assess prison incarceration or participants’ age at or length of incarceration. Similarly, MIDUS included a question to determine whether subjects had ever been in jail or “a comparable institution,” but did not record types (e.g., jail or prison) or lengths of incarceration. Only Add Health assessed subjects’ history of incarceration and included several other descriptive factors such as year, length, and family history of incarceration.

Table 1.

Data Sets that Can Be Used to Create and Investigate Groups of Formerly Incarcerated Persons

| Study | Sample* | Focus† | Keyword match item‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) | L | Disparities, risk | “In the last year” [in the baseline survey] or “Since your last CARDIA exam” [in follow-up surveys] “have any of these things happened to you?” Possible response: “Went to jail” |

| Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) | L | Disparities | “The following questions are about experience you may have had at ANYTIME.” Possible response: “Detention in jail or comparable institution” |

| National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) | L | Youth, disparities, risk | “Have you ever spent time in a jail, prison, juvenile detention center or other correctional facility?” |

| “How many times have you been in a jail, prison, juvenile detention center, or other correctional facility?” | |||

| “How much total time did you spend in jail or prison? [years]” | |||

| “How old were you the last time / first time when you went to jail, prison, juvenile detention center or other correctional facility?” | |||

| “Before your 18th birthday, about how much total time did you spend in jail or detention?” | |||

| “Since your 18th birthday, about how much total time have you spent in jail or prison?”§ |

*Samples are either cross-sectional (CS) or longitudinal (L)

†“Focus” is defined by study designers as indicated in descriptions of each study’s primary intended uses

‡For each data set, we searched all publicly available documentation including questionnaires, codebooks, and result summaries, for the terms Jail, Prison, Incarceration, Crime, Criminal, Convict, Victim, Police, Correctional, and Corrections using a keyword search. This table shows those keyword match items deemed to be the most relevant

§The Add Health questionnaires included 17 total keyword matches from our search. The six most relevant items are included here. Subjects were also asked questions related to their family history of incarceration and to the specific conviction(s) that led to incarceration

Missed Opportunities to Assess the Health of Formerly Incarcerated Persons

Nine studies (25%) contained a keyword match from our search but missed the opportunity to enable development of a study sample of formerly incarcerated persons (Table 2). For instance, in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), incarceration was not differentiated from other problems (Did you “get arrested, held at a police station, or have any other legal problems”?). In six (17%) such data sets [the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), Area Resource File, NAMCS & NHAMCS, and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program], incarceration was listed among possible responses to a question related to a subject’s living situation, but these responses were not recorded uniquely. Even most of the nine data sets that focused on health disparities did not include incarceration-related questions (6, 66%). For more examples, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Missed Opportunities to Create and Investigate Groups of Currently or Formerly Incarcerated Persons

| Study | Sample* | Focus† | Keyword match item‡ | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area Resource File (ARF) | CS | General | Prisoners are counted with other special groups as “population in group quarters” | Record prisoners uniquely |

| Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) | CS | Disparities, risk | “Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail, or other correctional facility?” | Ask about subjects’ history of incarceration |

| Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) | L | Cost | Directions to interviewer: “If [the subject] is homeless, is transient with no permanent home, or is in jail or prison, code response 96.” Response 96 is defined as “homeless/transient/jail or prison” | Record prisoners uniquely |

| Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) | L | Cost | “On January 1, (YEAR), was (PERSON) living in an institution?” According to the Glossary of Terms, “A person is institutionalized if s/he is living in a facility that provides continuous nursing and personal care… or if s/he is living in a correctional facility. Institutions include nursing homes, other long-term health care institutions… and other non-health care institutions” | Record prisoners uniquely |

| Nat’l Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) | L | Risk | Subjects are asked if certain events occurred in the previous year or since last participation. One event is: “Get arrested, held at a police station, or have any other legal problems because of your drinking” | Add incarceration to question and record prisoners uniquely |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER) | CS | Older adults, risk | According to the SEER Coding and Staging Manual, “persons who are incarcerated” are included in the study under the category “persons in institutions,” with others | Record prisoners uniquely |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | L | Older adults | According to study investigators, individuals are followed “when they move from the household population into institutions.” However, no changes to the available coding guidelines are made available | Record subjects who are followed to jail or prison as incarcerated |

| Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) | L | Older adults | According to study investigators, individuals are followed “when they move from the household population into institutions.” However, no changes are made to the relevant coding guidelines | Record subjects who are followed to jail or prison as incarcerated |

| National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS)§ | CS | General | Patient’s residence is recorded as “other institution” if patient is residing in “prison” | Record prisoners uniquely; record current prisoners included in data |

| National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS)§ | CS | General | Patient’s residence is recorded as “other institution” if patient is residing in “prison” | Record prisoners uniquely; record current prisoners included in data |

| HCUP State Inpatient Database (SID)§ | CS | Cost | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| HCUP Kids Inpatient Database (KID)§ | CS | Cost, youth | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| HCUP State Ambulatory Surgery Databases (SASD)§ | CS | Cost | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| HCUP Nationwide Patient Inpatient Sample (NIS)§ | CS | Cost, disparities | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| National Cancer Database (NCDB)§ | CS | General | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS)§ | CS | General | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| National Survey of Ambulatory Surgery (NSAS)§ | CS | General | N/A | Record current prisoners included in data |

| US Renal Data System (USRDS)§ | CS | Risk | “History of Prison” is recorded on a data form for the “cadaver donor” but the same information does not appear to be collected for study subjects | Ask about subject’s history of incarceration; record current prisoners included in data |

*Samples are either cross-sectional (CS) or longitudinal (L)

†“Focus” is defined by study designers as indicated in descriptions of each study’s primary intended uses

‡Some data sets included multiple keyword matches. The keyword match items included in the table were determined as the item most nearly useful in creating study sample of current or former prisoners for investigation of the relationships between incarceration and health

§Studies may rely on administrative data collected by health care providers. As a result, recommendations may best be targeted at health care service providers, administrators and policy makers, and not study investigators

Missed Opportunities in Longitudinal Studies

Ten of the 12 (83%) longitudinal study investigators responded to our questions about subjects who became incarcerated during their study. Of these, two (20%) followed subjects through incarceration and recorded that incarceration had occurred (Add Health and CARDIA). Four studies (40%) dropped those who became incarcerated and did not record incarceration as the cause of attrition [MIDUS, NESARC, Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)], though one of these (MIDUS) did record a lifetime history of incarceration for all participants. The four remaining studies (40%) followed subjects during or after their incarceration but did not generate a code to indicate that the incarceration transpired [Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Asset and Health Dynamics (AHEAD), MEPS and MCBS]. Overall, eight of ten (80%) participating longitudinal studies missed opportunities to document or track participant incarceration.

CONCLUSION

Despite the growth and expense associated with the US criminal justice system, and emerging evidence that incarceration is associated with poor health and high health care costs, a dearth of studies exists assessing the health of currently or formerly incarcerated persons. We analyzed the content of leading publically available national health data sets and found no data sets that could be used to assess the health of currently incarcerated persons. Additionally, while 12 of 36 (33%) data sets collected information related to incarceration, only 3 (8%) could be used to assess the health of formerly incarcerated individuals.

There are many reasons that national health data sets might not include currently or formerly incarcerated subjects. Because correctional health care has traditionally been isolated from mainstream health care, and the impact of incarceration on lifetime health care costs and outcomes is an emerging area of inquiry, investigators could be unaware of the importance of understanding the health and health care needs of this population. Logistical challenges to conducting research either in prisons and jails or with the formerly incarcerated may also serve as deterrents. For example, requirements of prisoner representation on Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), the approval of the IRB by the Office of Human Research Protections, and the lengthy application process for a Certificate of Confidentiality may remain significant barriers to including research subjects in the criminal justice system (either incarcerated or on parole). In 2006, however, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued new ethical guidelines that clarified the standards for health research related to prisoners, recognizing that “access to research may be critical to improve the health of prisoners.”32 The IOM guidelines should increase the ease of understanding how to conduct ethically sound research and, as others have noted, create an entrée for researchers to engage incarcerated populations in minimal risk clinical studies.33

Improved guidelines, and calls to include currently and formerly incarcerated persons in more health research, are important because such studies could add to our understanding of rising health care costs, variations in risk for certain medical conditions, and unexplained health disparities. For instance, over the past decade the unsustainable costs of prison health care have led states across the nation to reexamine their parole and sentencing policies.21,34 The potential for a significant budgetary shift from the criminal justice system to Medicare and Medicaid has been observed,35 yet the specific economic burdens associated with caring for current and former prisoners remain unknown. Additionally, several studies report higher rates of hypertension in incarcerated persons.6,16,19,29 Wang et al. used the CARDIA data to show that incarceration is an independent predictor of hypertension among black men.28 Yet, the longitudinal Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), which aims to “identify factors related to the onset and course of coronary heart disease and stroke,”36 does not assess subjects’ history of incarceration in its surveys and drops subjects who become incarcerated during participation. Finally, excluding incarcerated populations from studies of minority health could lead to biased or under-powered results given the disproportionate representation of minorities in the criminal justice system.33 Yet, we found that most data sets focused on health disparities did not include incarceration-related information.

We propose three basic mechanisms to significantly expand the availability of incarceration-related data for generalist health researchers. First, population-based studies of community care that likely include incarcerated persons should record the incarceration status of all participants. This basic step would generate a wealth of national health and cost data, particularly for prisoners with chronic medical conditions who are likely to require ongoing care after release. Second, studies that already obtain data about incarceration history should code it in a manner that can be used for analysis. Examples of this include data sets that obtain subjects’ incarceration histories but do not differentiate them from other legal or social problems such as homelessness or having been institutionalized in another setting such as a nursing home. Here, small changes to questions or coding mechanisms could enable researchers to study the associations between incarceration and health. Third, studies that already ask about a subject’s history of incarceration should add additional questions to account for potentially significant factors like the type (e.g., jail, prison, parole) and length of incarceration. Only one data set in our review, Add Health, exemplified such a comprehensive approach to recording incarceration-related data. As a result, Add Health has been used by researchers to understand incarceration’s impact on overall health.37,38 With the addition of a few carefully selected questions, other data sets (such as CARDIA and MIDUS) could join Add Health as leading sources of high-impact incarceration-related health research.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings and recommendations. First, not all national health data sets were considered in this review. Rather, we focused on the large, representative sample found in the SGIM Dataset Compendium, an expertly compiled and widely used source of data for secondary analyses among leading health care researchers.31 By precluding data sets outside of the SGIM compendium from our analysis, we may have omitted data sets from the fields of criminology or sociology that include health measures. While this may be seen as a limitation, we focused our evaluation on leading national health data sets because they specifically include robust health measures that could be used by health researchers to understand associations between health and incarceration. By taking this approach, we were able to make specific suggestions to improve the availability of criminal justice-related data for leading health-related research. Moreover, because of their important focus on other criminal justice data, criminologic or sociologic data sets generally include only limited health data. For example, we did not analyze the Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities series, a data set used in the study of prisoner health from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS),39 but with limited health measures and a primary focus on criminal justice data. Finally, because some data sets in our review used administrative data collected by health care providers, particularly those likely to include current prisoners (Table 2), we acknowledge that in some cases our recommendations may fall outside the scope of what study investigators can easily accomplish. Thus, we hope that our findings will have relevance not just to researchers and investigators, but also to hospital data administrators and policy makers as well.

Despite increasing evidence that currently and formerly incarcerated persons are in worse health and may generate higher health care costs than the general public, relatively few studies have been conducted to investigate the associations between incarceration and individual or public health. Our study highlights the extent to which relevant data are absent from most of the widely used and easily accessible national health data sets. Increasing the amount of available incarceration-related data could inform further studies and policies aimed at controlling health care costs, mitigating risk for chronic conditions among vulnerable populations, and narrowing demographic health disparities in outcomes and delivery.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions Study Concept and Design: Ahalt, WilliamsAnalysis and Interpretation of Data: Ahalt, Binswanger, Steinman and WilliamsPreparation of Manuscript, Critical Review: Ahalt, Binswanger, Steinman, Tulsky and WilliamsNo other parties contributed substantially to this research or to preparation of this manuscript.

Funders Dr. Williams is supported by the National Institute of Aging (K23AG033102), the UCSF Hartford Center of Excellence, and the Langeloth Foundation. Dr. Binswanger is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program. These funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Mr. Ahalt, Dr. Williams, and Dr. Steinman are employees of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The opinions expressed in this manuscript may not represent those of the VA.

Prior Presentations The abstract for this paper has been presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, May 5, 2011.

Conflicts of Interest Dr. Williams has been a consultant about prison conditions of confinement. Dr. Steinman helped to create the SGIM Dataset Compendium. These relationships did not affect the analysis of the data or preparation of this manuscript. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, or affiliations.

References

- 1.Bonczar TP. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the US Population, 1974–2001. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 2003.

- 2.Glaze LE. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2009. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 2010.

- 3.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–235. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. Department of Justice: Washington DC. 2004.

- 5.Solomon A, Osborne J, LoBuglio S, Mellow J, and Mukamal D. Life After Lockup: Improving reentry from jail to the community. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. 2008.

- 6.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd JW, et al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Center on the States. One in 100: Behind bars in America 2008. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts. February 2008.

- 8.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammett TM, Roberts C, Kennedy S. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime & Delinquency. 2001;47(3):390–409. doi: 10.1177/0011128701047003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallik-Kane K and Visher CA. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Research Report. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. February 2008.

- 11.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Behind bars: Substance abuse and America's prison population. New York, NY: CASA Columbia. 1998.

- 12.The Urban Institute. Public health dimensions of prisoner reentry: Addressing the health needs and risks of returning prisoners and their families. Meeting Summary. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, Justice Policy Center. December 2002.

- 13.Mumola C. Special report: substance abuse and treatment state and federal prisoners, 1997. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Editor: Washington DC. 1999.

- 14.Glaser JB, Greifinger RB. Correctional health care: a public health opportunity. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(2):139–145. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be-released inmates. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: NCCHC. 2002.

- 16.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912–919. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aday R. Aging Prisoners: Crisis in American Corrections. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anno B, Graham C, Lawrence J, Shansky R. Correctional Health Care: Addressing the Needs of Elderly, Chronically Ill, and Terminally Ill Inmates. Middletown, CT: Criminal Justice Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baillargeon J, Black SA, Pulvino J, Dunn K. The disease profile of Texas prison inmates. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):74–80. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitka M. Aging prisoners stressing health care system. JAMA. 2004;292(4):423–424. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorman B. With soaring prison costs, states turn to early release of aged, infirm inmates. Washington DC: National Conference of State Legislatures; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrell M, Marsden J. Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction. 2008;103(2):251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart LM, Henderson CJ, Hobbs MS, Ridout SC, Knuiman MW. Risk of death in prisoners after release from jail. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(1):32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2004.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verger P, Rotily M, Prudhomme J, Bird S. High mortality rates among inmates during the year following their discharge from a French prison. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(3):614–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travis J, Solomon AL, Waul M. From Prison to Home: The Dimensions and Consequences of Prisoner Reentry. Washington: Urban Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammett TM, Gaiter JL, Crawford C. Reaching seriously at-risk populations: health interventions in criminal justice settings. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(1):99–120. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Public Health Behind Bars: From Prisons to Communities, ed. Robert Greifinger. New York: Springer. 2007,576 pgs.

- 28.Wang EA, Pletcher M, Lin F, et al. Incarceration, incident hypertension, and access to health care: findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):687–693. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colsher PL, Wallace RB, Loeffelholz PL, Sales M. Health status of older male prisoners: a comprehensive survey. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):881–884. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.82.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maruschak L. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Medical Problems of Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith AK, Ayanian JZ, Covinsky KE, et al. Conducting High-Value Secondary Dataset Analysis: An Introductory Guide and Resources. J Gen Intern Med. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Gostin LO. Biomedical research involving prisoners: ethical values and legal regulation. JAMA. 2007;297(7):737–740. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang EA, Wildeman C. Studying health disparities by including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1708–1709. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu T. It's About Time: Aging prisoners, increasing costs, and geriatric release. New York, NY: The Vera Institute of Justice; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maul F. Delivery of end-of-life care in the prison setting. In: Puisis M, editor. Clinical practice in correctional medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. pp. 529–537. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massoglia M. Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law & Society Review. 2008;42(2):275–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5893.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Dept. of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2004. ICPSR04572-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2007