Abstract

BACKGROUND

Premature mortality and disparities in morbidity observed in African-American men may be associated with factors in their social, economic, and built environments that may be especially influential during the transition to adulthood.

OBJECTIVE

To have young, African-American men from Los Angeles County identify and prioritize factors associated with their transition to manhood using photovoice methodology and pile-sorting exercises.

DESIGN

Qualitative study using community-based participatory research (CBPR) and photovoice

PARTICIPANTS

Twelve African-American men, ages 16–26 years, from Los Angeles County, California.

APPROACH

We used CBPR principles to form a community advisory board (CAB) whose members defined goals for the partnered project, developed the protocols, and participated in data collection and analysis. Participants were given digital cameras to take 50–300 photographs over three months. Pile-sorting techniques were used to facilitate participants’ identification and discussion of the themes in their photos and selected photos of the group. Pile-sorts of group photographs were analyzed using multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis to systematically compare participants’ themes and identify patterns of associations between sorted photographs. Sub-themes and related quotes were also elicited from the pile-sorting transcripts. The CAB and several study participants met periodically to develop dissemination strategies and design interventions informed by study findings.

KEY RESULTS

Four dominant themes emerged during analysis: 1) Struggles face during the transition to manhood, 2) Sources of social support, 3) Role of sports, and 4) Views on Los Angeles lifestyle. The project led to the formation of a young men’s group and community events featuring participants.

CONCLUSIONS

CBPR and photovoice are effective methods to engage young, African-American men to identify and discuss factors affecting their transition to manhood, contextualize research findings, and participate in intervention development.

KEY WORDS: race/ethnicity, men’s health, socioeconomic factors, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

African-American men have the lowest life expectancy and highest age-adjusted death rates for homicide, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, cerebrovascular accidents, and malignant neoplasms compared to men and women from other racial/ethnic groups.1 A substantial portion of health disparities observed among African-American men are the result of cumulative exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage, racism, and residence in resource-poor neighborhoods over the life course.2–9 In Los Angeles County, home to one of the largest African-American populations in the United States, African-American men are three times more likely to live in poverty and to drop out of high school than men from other racial/ethnic groups, and have the highest unemployment rate at 16%.10,11 They also more likely to experience police stops when driving, incarceration, and race-based violence.10 Homicide rates for African-American men ages 15–24 years old are alarmingly high at three times the rate for Hispanics and ten times for other racial/ethnic groups.1,12

The inter-related contextual factors that structure lifestyle choices and have direct and indirect effects on African-American men’s health may be especially detrimental during the transition to manhood. The transition to adulthood is one of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes that are shaped by one’s social context. As young men become increasingly self-sufficient, they face vital choices that may include the pursuit of higher education, achieving financial independence, taking on new responsibilities in personal relationships and family, and making independent decisions on life goals.13 Traditional beliefs about manhood adopted by young men may include the denial of weakness, emotional and physical control, dismissal of the need for help, and the display of aggressive behavior and physical dominance.14 This developmental stage is a particularly vulnerable time for African-American men because their ability to make life decisions may be constrained by their environment and opportunities. These dominant constructions of manhood may be internalized by African-American men and lead to unhealthy, risk-taking behaviors resulting in adverse health outcomes.14 As such, this transition period may be a pivotal time to intervene in the lives of young, African-American men in order to promote a safe and healthy manhood.

Few studies have examined the impact of contextual factors in the transition to manhood or elicited the perspectives of young, African-American men to understand the mechanisms contributing to health disparities. We report the results of a research project in which young, African-American men from Los Angeles County, with guidance from a community advisory board (CAB), used photovoice and other qualitative research methods to identify, discuss, and develop strategies to address factors influential in their transition to manhood.

METHODS

Advisory Board

This project was designed and conducted using community-based participatory research principles.15,16 Partners for a community advisory board (CAB) were identified by the lead investigator through meetings with and referrals from representatives of organizations with a history of working on issues relevant to African-American men. The CAB was comprised of nine community leaders and three academic researchers, whose goal was to develop strategies for understanding and reducing health disparities among African-American men. Each community member had over ten years of work experience in their field and included leaders of well-recognized family, health, arts, education, social service, and neighborhood-based organizations in Los Angeles County. Although several CAB members had worked together previously, this was the first opportunity for most members to collaborate on a research project. In a series of monthly meetings, the CAB identified the transition to manhood as an important developmental, decision-making stage that might be the focus of an intervention, and defined the transition to manhood as a time period when one had left the security of secondary school or caretakers. Of note, the CAB chose not to share this definition with the participants as not to bias their photographs and discussions. CAB members partnered in all phases of the project to conceptualize the research question, define broad goals for a collaborative project, develop the study objectives and protocols, decide on the methodology, recruit and train participants, participate in data analysis and interpretation, and disseminate project results. The protocol was approved by the RAND IRB.

Participants

Eligible participants were African-American men, ages 16–26 years, who resided in Los Angeles County and self-identified as African-American. CAB members used personal and professional connections to recruit fifteen young men whom they felt had recently navigated the transition to manhood, would provide a forthcoming account of life experiences, had diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, and would be able to complete all project phases. All recruited participants were interviewed and asked to attend a one-day training session. Three men decided not to continue after attending the training session. The remaining 12 participants completed all phases of the study protocol. Participants received $150 in gift cards for their participation. Refer to Table 1 for participant demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics of Photovoice Participants

| Participant Characteristics | N = 12 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (year, range)* | 22 (16–26) |

| Any college, % | 25 |

| Employed full-time | 33 |

| Have been homeless, % | 30 |

| Raised in single-parent household, % | 50 |

| Raised in foster-care system, % | 25 |

| Current fathers, % | 17 |

| Prior incarceration, % | 25 |

| Prior gang involvement, % | 30 |

| Interest in careers in the sports or entertainment industry, % | 50 |

| Neighborhood Characteristics | |

| Neighborhood >35% African-American†, % (LAC‡ mean 9%) | 67 |

| Majority of zip code population at >200% FPL§, % (LAC mean 38%) | 50 |

*Range of ages: 1 participant was 16 years old, 1 was 19, 3 were 20, 1 was 21, 2 were 23, 3 were 24, and 1 was 26 years old

†Neighborhoods include Compton, South Central Los Angeles, Culver City/Ladera, and Wilshire Los Angeles. Five out of 8 neighborhoods have a Latino population greater than 50%

‡ LAC = Los Angeles County

§FPL = federal poverty level

Data Source: The Zip Code Data Book: The United Way of Greater Los Angeles; August 2003http://www.unitedwayla.org/getinformed/rr/socialreports/Pages/ZipCodeDataBook.aspx

Study Procedures and Data Collection

Photovoice Photovoice is a participatory strategy that uses photographs taken by individuals to promote critical reflection, enhance group discussion, share knowledge, create empowerment, and reach policy makers.17 Photovoice has been used to highlight social and environmental factors that can affect health and well-being in culturally diverse, hard-to-reach, and disenfranchised populations.18–20

Training and Equipment The CAB facilitated a training session for participants that included discussions of the project purpose, photovoice methodology, research ethics, review of informed consent, and practice sessions conducted by a professional photographer.21 Lectures were given on safety issues and how-to obtain permission and informed consent for subjects that could be identified in the photographs. Participants were told that photographs of individuals without consent would be removed from the analysis. Each participant received a digital camera, memory card, camera case, batteries, and half-page consent forms to be signed by photographed subjects.

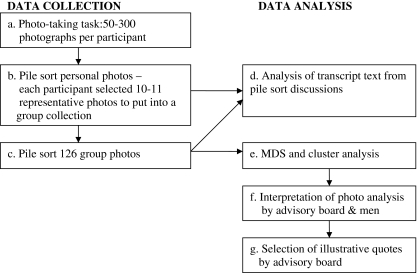

Photo-taking Task Participants were asked to take between 50–300 photographs on factors influential in to their transition to manhood for a three-month period between November 2008 and January 2009 (Fig. 1, box a). CAB members met regularly with the participants to discuss their reactions to taking photographs and to better understand the photovoice process. All subjects photographed in private settings provided consent.

Figure 1.

Data Collection and Data Analysis Phases. In using the photovoice methodology, the advisory board sought to elicit the perceptions of young, African-American men through photographic images (a) and discussion. Discussion of the images occurred in two distinct pile-sorting settings: 1) sessions in which each participant verbalized his impression of images in his personal set of photographs (b), and 2) sessions in which each participant discussed the similarities and differences he saw in a common set of images comprised of a sample of photographs from all participants (c). Multivariate analysis of pile sort data (e) and systematic analysis of discussion transcripts (d) were used to identify the main issues that the young men considered important in their transition to manhood. MDS, multidimensional scaling.

Pile Sorting Task Pile sorting is a qualitative data analysis technique used to understand patterns in the participants’ photographs and discussions.22,23 Participants pile sorted and discussed their personal set of photographs (Fig. 1, box b), and a group collection of photographs, one-on-one with a CAB member (Fig. 1, box c).22,23 Each participant selected 1–2 representative photographs from their individual piles to put into a group collection of 126 photographs. Discussions were guided by the SHOWeD questions: (1) What do you SEE in this photograph? (2) What is really HAPPENING in this photograph? (3) How does this relate to OUR lives? (5) WHY does this situation, concern, or strength exist? and (5) What can we DO to address these issues?24,25 These 1–2 hour sessions were audio recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis and Theme Generation

The participants’ data were entered into ANTHROPAC, a software designed to produce data matrices from pile sort data.26 A photo-by-photo aggregate proximity matrix was produced that represented the proportion of time that each unique combination of two photos was placed together in piles by the participants. The aggregate proximity matrix was then analyzed with Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) to produce a two-dimensional scatterplot of the output and a cluster analysis using the single-link method (Fig. 1, box e). These techniques are common multivariate analysis techniques for analyzing pile sort data.23,27,28 Participants and CAB members convened to discuss and interpret the results, reached consensus about how best to describe the set of photographs in each cluster, and identified an accompanying theme (Fig. 1, box f).

Photographs and transcripts from the pile-sorting sessions were reviewed by the research team. Two individuals (PI and research assistant) coded the transcripts using qualitative data analysis methods based on the principles of grounded theory (Fig. 1, box d)..29 The analysts first read through each transcript and tagged quotes from the text that represented one of the broad themes that participants identified in the discussion of the results (Kappa = 0.813). The analysts constructed a codebook that defined these themes and salient sub-themes in detail.30 Categories that did not fit easily into an established theme were added as new themes to the codebook. The final set of themes and sub-themes were verified by CAB members and participants for clarification, consensus, and validation.29 To summarize the themes, CAB members selected an exemplary quote and photograph (Fig. 1, box g). Additional photographs can be viewed at www.blackmensphotovoice.org.

RESULTS

Theme Analysis

From a synthesis of photographs taken, iterative discussions, participants’ labeling of piles, and MDS/cluster analyses, four themes emerged as instrumental in the transition to manhood for the participants. The main themes are: (1) struggles, (2) social support and inspiration, (3) role of sports, and (4) views on Los Angeles (L.A.) lifestyle. Presented below for each main theme or sub-theme is an exemplary quote followed CAB members’ comments.

Struggles Struggles in the transition to manhood incorporated sub-themes such as racism, unemployment, neighborhood disadvantage, family challenges, and psychological health.

Race Struggles All 12 men independently photographed and discussed racial tensions, interpersonal discrimination, and racial profiling. Racial tensions were described as rivalry between African-American and Latino gangs, and among peers in school: “The school police are always busy because we're having major race riots and wars. On the laundry mat around the corner from my house it said, ‘F All Niggers’.”

One participant described discrimination from a photograph of a store clerk’s face: “Like him, look, he’s staring ‘don’t steal nothing out my store’. He’s still looking ‘don’t steal anything out my store’.” Racial profiling by law enforcement and negative experiences with being pulled over while driving were prominent sub-themes: “My experiences with the police have not been the best. I haven’t gotten beat up or they haven’t killed any of my friends, but from tickets and being harassed.”

According to the CAB, young, African-American men feel anger, stress, and isolation when they realize that their physical identity (e.g., age and race) is associated with societal fear and suspicion that may limit their economic opportunities, social interactions, and place of residence. These negative feelings are either internalized or outwardly expressed through aggressive behaviors.31

Economic Struggles Ten men discussed concerns with unemployment, financial instability, and homelessness. One college-educated participant described his experiences:

“[A] picture of Working World newsstand. It says, ‘Working World, the best jobs in town,’ which is a lie, because I looked in this magazine for over six months and never found a job out of it.”

“I’m registered with a million temp agencies. I was employed, and that was the best feeling in the world. I mean, Christmas is great, but it’s nothing like having a job.”

CAB members agreed that employment in a stable job for a young man can single-handedly change his life course and prevent him from “turning to the streets” or engaging in illegitimate activities to earn money.Another participant who was employed full-time at minimum wage said: “I feel like I’m broke. If something really bad or devastating were to happen in life, I wouldn’t even have any money to work off of. I would just have my living from paycheck to paycheck.” The participants also connected financial instability with photographs of homeless people to show that they did not want that lifestyle: “I was homeless for two years. I’ve stayed in shelters and I’ve slept in a park. I remember sitting on a bus stop myself, not having any place to go, not knowing where I’m gonna get my next meal, and just chilling like him.” Given the high numbers of African-American men with low-income jobs and inadequate economic resources, CAB members were not surprised that the participants saw homelessness as a potential life trajectory.10

Neighborhood Disadvantage Eight men photographed and discussed their built environment as a place of urban decay with graffiti tagging, barren land, dilapidated housing, unsafe parks, and sidewalks littered with liquor stores and unhealthy fast food shops. The CAB noted that several photographs and quotes depicted life in the neighborhood as feeling trapped or behind bars, which may socialize youth into feeling comfortable with incarceration. Figure 2 and the following quote are examples of this sub-theme:

“Even my grandmother put bars on her [home]. You can walk all around here, people have bars on everything.”

Community violence was articulated to be a normal part of growing up:

“Not being able to go to sleep because you don’t hear the police helicopters circling. Wondering if you’re going to get jumped on the way to school. Wondering if a stray bullet’s going to hit you. These things are not normal for most kids, but to me, it was.”

“Birthdays are important. I cried when I turned 18 because so many of my friends that didn’t. A couple of dudes that I know died while we were around 15, shot in the streets.”

CAB members admitted that living in a racially-segregated, resource-poor neighborhood was a form of institutional racism, and that one’s transition to a healthy manhood is constrained when the physical environment limits access to health care, green space, healthy food, and places to exercise. CAB members also correlated the direct health effects of exposure to community violence with the disturbingly high rates of homicide for young, African-American men, as well as indirect effects on mental health through trauma and stress.

Figure 2.

Photograph and quote depicting institutional racism. “The locks and chains that keep us in the same community [are] a representation of the four freeways that enclose Compton after the Watts riots. We’re encaged into one area so that if anything ever happened again, it can be easily accessible by a National Guard base within ten minutes of here.”

Family Struggles The majority of participants were raised by single mothers, extended family members, or in the foster care system. Men who lost their caretakers to chronic medical illness or violent death often described this loss as a low point in their lives that was associated with depression, rebellious behavior, and financial instability. Eight participants discussed family challenges, especially men raised in the foster care system: “I stayed with [my foster mom] for nine years. She kicked me out right before high school ended. There was no notice. It was just I'm tired of him. I'm done with him. She made me pack my stuff that day and dropped me off at the office. And I sat there all day; they were trying to find a place for me.”CAB members noted that the influence of fathers in the participants’ transition to manhood was “missing”, possibly because biological fathers were absent from the young men’s lives. They also commented that participants with stable family structures or who had compensated with other male role models from the family or community regarded family as a source of support.

Psychosocial Struggles Five men openly discussed psychological challenges during their transition to manhood. One participant described feeling alone and uncertain about his future, while another spoke about his depression:

“He’s walking a lonely road. Gives you a sense of what some guys my age think we’re doing. We think we’re walking the road by ourselves. You can see what’s in front of you, you can see what’s behind you, but sometimes you feel like you’re by yourself.”

“I was out of work for a while. I was in jeopardy of losing the house that I’m in and I was having problems with my girlfriend. It seemed like there was no end in sight and I started thinking about committing suicide. It was just a real dark time for me, just deep in depression.”

The CAB acknowledged that feeling despair from a lack of control over one’s life was common in young, African-American men who grew up with the collective effects of racism, economic strife, dangerous neighborhoods, and family instability. CAB members described the transition to manhood as a time period where everything appears more intense and urgent, but without having developed healthy coping mechanisms. Some men described avoidance through alcohol and drugs: “I was always around [marijuana] because my dad smoked. I started going through a lot and getting high to take my mind off of stuff that’s going on in my life.”

Sources of Support and Inspiration Struggles faced by the participants were buffered by a number of support systems that allowed the men to navigate the transition to manhood in ways that were positive. Supports included family, friends, and community members, as well as inspiration from service work with youth, African-American leaders (e.g., President Obama, Malcolm X), Church, music, and nature. Figure 3 is an example of older African-American men mentoring youth through sports.All twelve participants described ways in which they helped the younger generation: “My new team that I'm coaching. It’s a lot of boys, a lot of good talent, and a lot of lost souls. They don’t have a positive male figure. It’s going to be a good challenge for me.” CAB members felt service work in this population was under recognized.Church and faith was frequently mentioned as a source of support, especially among men who may not have had positive role models:

“[Church] is a central part of my life; it’s where I spend probably 40% of my time. I got saved-I was living a wrong life.”

“God is the only thing that really got me through some of the problems.”

While some men struggled with feeling alone and misunderstood, they also credited their supports in helping them choose pathways that decreased the likelihood for gang involvement, incarceration, substance abuse, or death.

Figure 3.

Photograph and quote depicting social support from community members. “You don’t really see black men in a neighborhood helping out. But [these coaches] are giving back to the community. They helped me to get to where I'm at now. Without them I really couldn’t do nothing.”

Sports Ten participants discussed the role of sports in their lives. Sports were described as a source of teamwork, an outlet or escape, a way to socialize with other African-American men without police harassment, fitness, coaching, entertainment, and personal accomplishment that was pivotal during their transition to manhood. For example, a photograph of young men playing basketball elicited the comment, “I’ve been playing basketball since I was four or five. Sports are an outlet for anybody, any color.”One participant took a photograph of his trophies and said, “I played football for Crenshaw High growing up and I got three basketball championships and two football championships. That’s my trophies and I'm just proud of that.” The CAB had conflicting feelings about the role of sports during the transition to manhood. While CAB members agreed on the positive aspects of sports, they also acknowledged sports accomplishments are often the sole source of pride for young, African-American men and boys, and an overemphasis on sports may undermine educational pursuits and future life goals.

L.A. Lifestyle All the participants photographed the excess and opulence associated with the L.A. lifestyle; photographs were of high-end fashion stores, luxury and sports cars, large homes, and rich neighborhoods. They recognized the influence of living in L.A. on their personal and professional goals, and connected having particular brand names with being successful. One participant said, “My dream one day is to own a Bentley. Once I own a Bentley I know I'm set for life. I know I can take care of my family, take care of myself. And I know how to be a better man once I have one of those.” The CAB commented that the unhealthy desire for wealth at this age may be more pronounced in L.A., given the stark income inequality, and may lead to high-risk behaviors to obtain money or poor money management.

Action Step – Young Men’s Group

The CAB played a critical role in shaping the project and partnering with the young men to interpret the findings. CAB members identified the transition to manhood as one of the most dangerous periods for African-American men because of the expectations of manhood (e.g., find a job, support family, pay bills) in an environment that limits them. Although the recruited participants were men who the CAB felt had successfully navigated the transition to manhood because they were not currently in gangs, in jail, selling drugs, or dead, it became evident to both the participants and CAB members that the young men continued to struggle with the challenges they described as they attempted to realize life goals. Discussion between the CAB and participants resulted in the design and implementation of a young men’s group. The group met twice monthly for three months with a structured program of speakers, exercises, and readings based on a Rites of Success curriculum that helps participants access and utilize community resources to build bridges to their futures. The men have also conducted events in community venues in Los Angeles and Long Beach and in local secondary schools where they shared their photographs and discussed lessons that helped them increase their physical and emotional well-being. The events have been well-received with over 300 attendees and positive evaluations. The men plan to continue dissemination events and become trained in a Rites of Passage curriculum with the support of the CAB.

DISCUSSION

The young, African-American men in this project used photovoice, pile-sorting, and input from a CAB to identify four major themes that characterized their transition to manhood: struggles, supports, sports, and L.A. lifestyle. Participants’ descriptions of institutional racism, unemployment, income inequality, and neighborhood violence have been implicated in higher rates of conditions that include homicide, HIV/AIDS, stress, and depression among young men.7,11,32 The lack of self-efficacy in restricted environments expressed by the participants has been associated with elevated rates of substance abuse and violent behavior.31,33 These difficult experiences in early life may lead to maladaptive coping mechanisms resulting in severe morbidity and premature mortality from chronic medical conditions, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and depression, among older African-American men.7,34

Participants credited family, friends, significant others, community members, church participation, and sports as supports that helped them navigate the transition to manhood. As described by older African-American men in Ornelas et al., the young men in our study identified service as an important part of their identity.19 Young, urban African-American men are rarely described as helping youth and being role models, but all the men indicated that a principal reason for participation in the photovoice project was the possibility that sharing their experiences could benefit youth facing similar challenges. Our findings show that opportunities to be involved in community work may serve as a healthy coping mechanism during the transition to manhood for young, African-American men.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to highlight the viewpoints of young, African-American men on factors influencing their transition to manhood. Although we did not specifically ask men about their health, many of the themes/sub-themes represent potential targets for health interventions during a critical point in the life course. Our findings support prior research that suggest public health interventions that address challenging contextual factors in pathways to manhood and build on community assets may lower risk for unhealthy behaviors for young, urban African-American men.35,36 For example, in a health intervention described by Daniels et al., young men reentering the community after incarceration not only received health information to reduce drug use, HIV risk, and repeat arrest, but were also provided resources for employment and educational opportunities.36 Our results also suggest that primary care physicians who care for young, African-American men must be aware of these contextual influences and the community resources that can support current and future physical and emotional well-being.

Our research study has potential limitations. Our sample, though similar in size to other photovoice projects, was nonetheless a small convenience sample with participants who were heterogeneous in age, socioeconomic status, and childhood experiences, so generalizations from our findings should be made with caution. However, certain themes, such as police harassment, unemployment, financial difficulty, sports, the paradox of L.A. lifestyle, and service work were discussed independently by most participants despite their differences, and have been shown to be important to young, African-American men in other geographic regions.37 Our analysis is limited to the photographs and discussions of the participants; therefore, issues that do not lend themselves to photography may be missing.

Community-based participatory research and photovoice methods effectively engaged community leaders and young men in research protocol development, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination. The research process led to an intervention for the young men who realized that they may not have had successful transitions to manhood. These methods are an important strategy for understanding and reducing health disparities among vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Jamico Elder, Charles Boyd, and Andrea Jones for their participation in the community advisory board, and the Los Angeles Urban League for meeting space. Dr. Bharmal was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and UCLA National Service Research Award (T32 PE19001). Dr. Brown was supported by the Beeson Career Development Award (K23 AG26748), the UCLA Resource Center in Minority Aging Research (AG02004), the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20MD00148), and the American Heart Association Outcomes Research Center Award (0875133 N). Portions of this work were presented at the 2010 Academy Health Conference in Boston, MA and 2010 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Conference, Minneapolis, MN.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2010: With Special Feature on Death and Dying. Hyattsville, MD; 2011. [PubMed]

- 2.Lynch JWKG. Socioeconomic position. In: Kawashi I, Berkman L, editors. Social Epidemiology. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krieger N. Discrimination and health. In: Kawashi I, Berkman L, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 36–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Heal Aff. 2005;24(2):325–334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diez-Roux AV, Northridge ME, Morabia A, Bassett MT, Shea S. Prevalence and social correlates of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Harlem. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(3):302–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.3.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks P, Muennig P, Lubetkin E, Jia H. The burden of disease associated with being African-American in the United States and the contribution of socio-economic status. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(10):2469–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.State of Black Los Angeles 2011: Los Angeles Urban League;April 2011.

- 11.Davis LM, Kilburn MR, Schultz D. Reparable harm: assessing and addressing disparities faced by boys and men of color in California. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortality in Los Angeles County 2006: Leading causes of death and premature death with trends for 1997–2006: Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Office of Health Assessment and Epidemiology;September 2009.

- 13.Erikson EH, Erikson JM. The Life Cycle Completed: WW Norton & Company; 1997.

- 14.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community based participatory research. Community-based participatory research for health. 2003:3–26.

- 16.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community–participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Necheles JW, Chung EQ, Hawes-Dawson J, et al. The Teen Photovoice Project: a pilot study to promote health through advocacy. Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action. 2007;1(3):221. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ornelas IJ, Amell J, Tran AN, Royster M, Armstrong-Brown J, Eng E. Understanding African American men's perceptions of racism, male gender socialization, and social capital through photovoice. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):552–565. doi: 10.1177/1049732309332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strack RW, Magill C, McDonagh K. Engaging youth through photovoice. Heal Promot Pract. 2004;5(1):49. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CC, Redwood-Jones YA. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from Flint Photovoice. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(5):560–572. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: Sage; 1985.

- 23.Weller SC, Romney AK. Systematic data collection: Sage Publications, Inc: 1997.

- 24.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15(4):379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(2):171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borgatti SP. Anthropac 4.0. 1996. Natick, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- 27.Carolina SB. ANTHROPAC. Anthropol News. 1991;32(2):2–2. doi: 10.1111/an.1991.32.2.2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgatti SP. Elicitation techniques for cultural domain analysis. Enhanced ethnographic methods: audiovisual techniques, focused group interviews, and elicitation techniques. 1998:115–51.

- 29.Glaser BGSA. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Trw I, Kay AK, Milstein B, Cdc A. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. The Content Analysis Reader. 2008:211.

- 31.Rich JA, Grey CM. Pathways to recurrent trauma among young black men: traumatic stress, substance use, and the "code of the street". Am J Public Health. 2005;95(5):816–824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krivo Lauren J, Peterson Ruth D, Kuhl Danielle C. Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. Am J Sociol. 2009;114(6):1765–1802. doi: 10.1086/597285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolland JM. Hopelessness and risk behaviour among adolescents living in high-poverty inner-city neighbourhoods. J Adolesc. 2003;26(2):145–158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):724–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among urban low-income African American males. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):732–741. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniels J, Crum M, Ramaswamy M, Freudenberg N. Creating REAL MEN: description of an intervention to reduce drug use, HIV risk, and rearrest among young men returning to urban communities from jail. Heal Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):44–54. doi: 10.1177/1524839909331910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Race, Ethnicity & Health Care Fact Sheet: The health status of African American men in the United States: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: April 2007.