Abstract

Nanostructured, self-assembling peptides hold promise for a variety of regenerative medical applications such as 3D cell culture systems, accelerated wound healing, and nerve repair. The aim of this study was to determine whether the self-assembling peptide K5 can be applied as a carrier of anti-inflammatory drugs. First, we examined whether the K5 self-assembling peptide itself can modulate various cellular inflammatory responses. We found that peptide K5 significantly suppressed the release of tumor-necrosis-factor- (TNF-) α and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from RAW264.7 cells and peritoneal macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Similarly, there was inhibition of cyclooxygenase- (COX-) 2 mRNA expression assessed by real-time PCR, indicating that the inhibition is at the transcriptional level. In agreement with this finding, peptide K5 suppressed the translocation of the transcription factors activator protein (AP-1) and c-Jun and inhibited upstream inflammatory effectors including mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), p38, and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3/6 (MKK 3/6). Whether this peptide exerts its effects via a transmembrane or cytoplasmic receptor is not clear. However, our data strongly suggest that the nanostructured, self-assembling peptide K5 may possess significant anti-inflammatory activity via suppression of the p38/AP-1 pathway.

1. Introduction

Inflammation is one of the body innate immune responses and is mainly mediated by macrophages. When viruses or bacteria infect the body, significant cooperation among macrophages, dendritic cells, B cells, and T cells is required. Various inflammatory molecules, such as cytokines (e.g., tumor-necrosis-factor- (TNF-) α), chemokines, and mediators (including nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)), are known to play critical roles in managing crosstalk between immune cells in both acute and chronic responses [1, 2]. In this regard, the initial activation of macrophages in inflammatory events could be an important step.

Initiation of the macrophage inflammatory process is triggered by the activation of receptors such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR3 through the binding of their ligands, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and poly(I:C), respectively [3]. A series of intracellular signaling events follows, managed by the activities of nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including ERK (extracellular signal-related kinase), p38, and JNK (C-Jun N-terminal kinase), as well as the activation and upregulation of transcription factors (e.g., nuclear-factor- (NF-) κB and activator-protein- (AP) 1) [4, 5]. Eventually, these responses lead macrophages to be transcriptionally activated to express proinflammatory genes encoding such cytokines as tumor-necrosis-factor- (TNF-) α, inducible NO synthase (iNOS), and cyclooxygenase- (COX-) 2 [6–9].

Although it is well known that inflammation is a representative defense mechanism in the body, severe inflammatory responses may lead to a number of serious diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, septic shock, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis [8, 10–12]. Effective modulation of the acute or chronic inflammatory responses could be used to cure or prevent such diseases; each of the biochemical elements of the inflammatory signaling pathway may be considered as an anti-inflammatory target for new drug development.

Self-assembling peptide nanofiber-based hydrogels with a broad range of biomedical and biotechnological applications have been widely studied [13, 14]. Short peptides with 8 to 16 residues or 2.5 to 5 nm in length have been found to self-assemble into hydrogen-forming nanofibers under the proper conditions, including pH and ionic strength of the medium [15]. Due to their structural merits, such hydrogel systems have been applied to 3D tissue cultures and tissue engineering research systems [16, 17]. An interesting pharmacological application of this nanofiber technology is as a biocompatible drug delivery system controlling the release of small molecules or peptides/proteins [14]. Controlling the release rates of small molecules and peptides/proteins through various hydrogels is a critical aspect of biomaterials science.

Even though self-assembled peptide nanofibers are more advantageous than synthetic drug delivery polymers, it is necessary to test whether the peptide components are immunogenic or inflammation-inductive in the body. Because only a few studies regarding the effects of peptide nanofibers on immunological responses have been reported, we explored the immunoregulatory role of a representative peptide nanofiber (peptide K5) by measuring its inflammation regulation activity in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Peptide K5 was designed and prepared as previously described [18, 19]. (3-4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, a tetrazole (MTT), dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, E. coli 0111:B4) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). SB203580 was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Luciferase constructs containing promoters sensitive to NF-κB and AP-1 were gifts from Professors Chung Hae Young (Pusan National University, Pusan, Republic of Korea) and Man Hee Rhee (Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea). Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for determining PGE2 and TNF-α were purchased from Amersham (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Fetal bovine serum and RPMI1640 were obtained from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY). RAW264.7 and HEK293 cells were purchased from the ATCC (Rockville, MD). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and were obtained from Sigma. Phosphospecific or total antibodies against c-Fos, c-Jun, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3/6 (MKK3/6), TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1), inhibitor of κBα (IκBα), γ-tubulin, and β-actin were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA).

2.2. Animals

C57BL/6 male mice (6 to 8 weeks old, 17 to 21 g) were obtained from Daehan Biolink (Chungbuk, Republic of Korea) and housed in plastic cages under conventional conditions. Water and pellet diets (Samyang, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) were available ad libitum. Studies were performed in accordance with guidelines established by the Kangwon University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. Preparation of Peritoneal Macrophages

Peritoneal exudates were obtained from C57BL/6 male mice (7 to 8 weeks old, 17 to 21 g) by lavaging four days after intraperitoneal injection of 1 mL of sterile 4% thioglycolate broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) as reported previously [20]. After washing with RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS, peritoneal macrophages (1 × 106 cells/mL) were plated in 100 mm tissue culture dishes for 4 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

2.4. Cell Culture

Peritoneal macrophages and cell lines (RAW264.7 and HEK293 cells) were cultured with RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) at 37°C under 5% CO2. For each experiment, cells were detached with a cell scraper. At the cell density used for experiments (2 × 106 cells/mL), the proportion of dead cells was less than 1% as measured by Trypan blue dye exclusion.

2.5. NO, PGE2, and TNF-α Production

After preincubation of RAW264.7 cells or peritoneal macrophages (1 × 106 cells/mL) for 18 h, cells were pretreated with Peptide K5 (0 to 400 μg/mL) for 30 min and were further incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. The inhibitory effect of peptide K5 on NO, PGE2, and TNF-α production was determined by analyzing NO, PGE2, and TNF-α levels with the Griess reagent and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits as described previously [21, 22].

2.6. Cell Viability Test

After preincubation of RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) for 18 h, the peptide K5 (0 to 100 μg/mL) was added to the cells and incubated for 24 h. The cytotoxic effect of the peptide K5 was then evaluated by a conventional MTT assay, as reported previously [23, 24]. At 3 h prior to culture termination, 10 μL of MTT solution (10 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) was added to each well, and the cells were continuously cultured until termination of the experiment. The incubation was halted by the addition of 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate into each well, thus solubilizing the formazan [25]. The absorbance at 570 nm (OD570–630) was measured using a Spectramax 250 microplate reader.

2.7. mRNA Analysis by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reactions (RT-PCR)

To determine cytokine mRNA expression levels, total RNA was isolated from LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells with the TRIzol Reagent (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was stored at −70°C until use. Quantification of mRNA was also performed using real-time RT-PCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan) and a real-time thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as reported previously [26, 27]. The results were expressed as a ratio of optical density to GAPDH. The primers (Bioneer, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) used are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in real-time PCR analysis.

| Gene | Primer sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | F | 5′-CCCTTCCGAAGTTTCTGGCAGCAGC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GGCTGTCAGAGCCTCGTGGCTTTGG-3′ | |

| COX-2 | F | 5′-CACTACATCCTGACCCACTT-3′ |

| R | 5′-ATGCTCCTGCTTGAGTATGT-3′ | |

| GAPDH | F | 5′-CACTCACGGCAAATTCAACGGCAC-3′ |

| R | 5′-GACTCCACGACATACTCAGCAC-3′ |

2.8. Luciferase Reporter Gene Activity Assay

HEK293 cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were transfected with 1 μg of plasmids containing NF-κB-Luc or AP-1-Luc along with β-galactosidase using the calcium phosphate method in a 12-well plate according to the manufacturer's protocol [28]. The cells were used for experiments 48 h after transfection. Luciferase assays were performed using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) as reported previously [29].

2.9. Preparation of Total Lysates and Nuclear Extracts and Immunoblotting

Preparation of total lysates and nuclear extracts from LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells pretreated with peptide K5 was performed using a previously published method [30]. Immunoblot analysis of levels of phosphorylated or total transcription factor (AP-1(c-Fos, c-Jun), p-FRA-1), Lamin A/C, MAPK (ERK, p38, and JNK), MKK 3/6, TAK-1, IRAK-1, IκBα, and β-actin was performed according to published methods [31, 32].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data (Figures 1, 2, and 4), expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), were calculated from one (n = 6) of two independent experiments. Other data are representative of three different experiments with similar results. For statistical comparisons, results were analyzed using analysis of variance/Scheffe's post hoc test, and the Kruskal-Wallis/Mann-Whitney test. All P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were carried out using the computer program SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

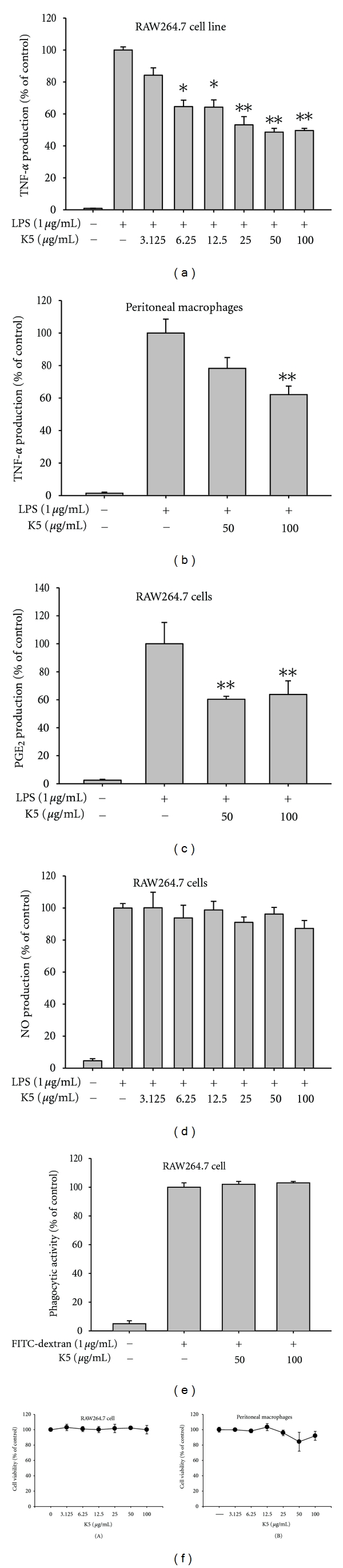

Figure 1.

Effect of peptide K5 on the production of inflammatory mediators. (a), (b), (c), and (d) Levels of NO, PGE2, and TNF-α were determined by Griess assay, EIA, and ELISA from culture supernatants of RAW264.7 cells or peritoneal macrophages treated with peptide K5 (0 to 100 μg/mL) and LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 (TNF-α) or 24 (NO and PGE2) h. (e) Phagocytic uptake levels of FITC-dextran were determined by flow cytometric analysis using RAW264.7 cells treated with peptide K5 (0 to 100 μg/mL) and FITC-dextran (1 μg/mL) for 6 (TNF-α) or 24 (NO and PGE2) h. (e) Cell viability of RAW264.7 cells and peritoneal macrophages was determined by MTT assay. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared to control.

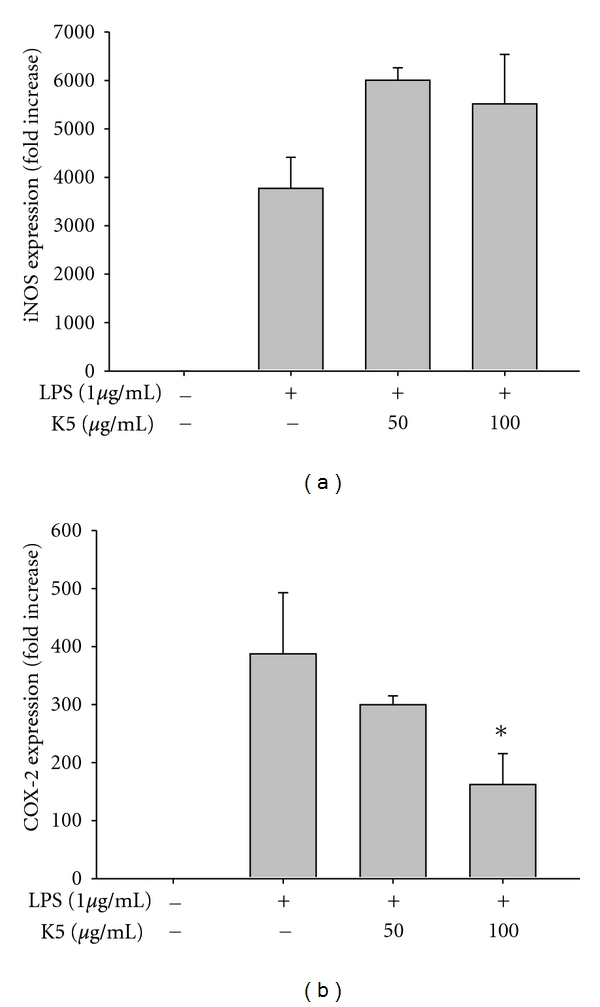

Figure 2.

Effect of peptide K5 on the mRNA expression of proinflammatory genes. (a) and (b) The mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2 were determined by real-time PCR. *P < 0.05 compared with controls.

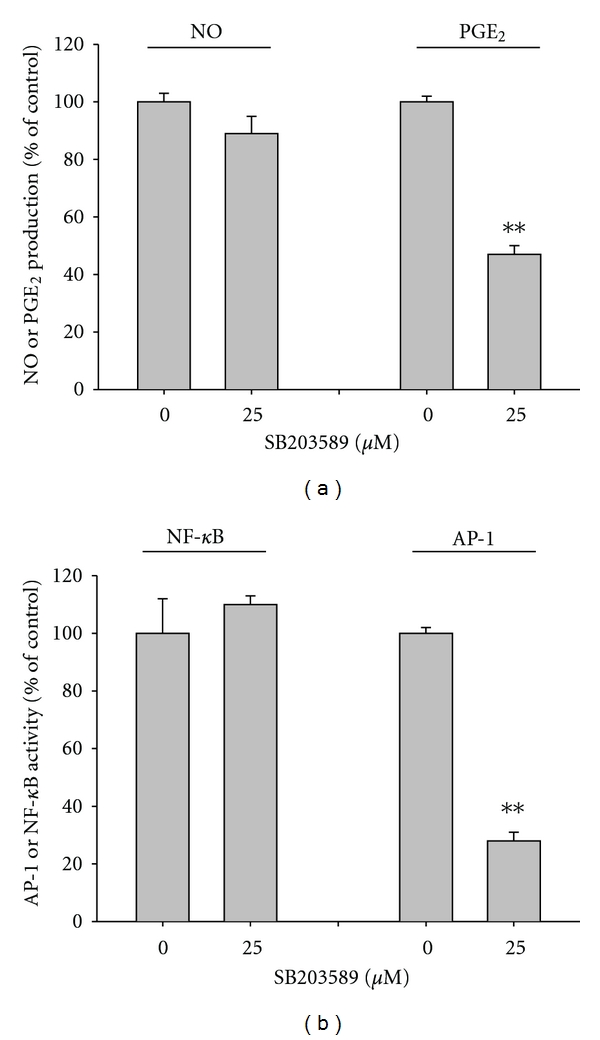

Figure 4.

Effect of SB203580 on the production of NO and PGE2 and activation of AP-1. (a) Levels of NO and PGE2 were determined by Griess assay and EIA from culture supernatants of RAW264.7 cells treated with SB203580 (25 μM) and LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 (NO and PGE2) h. (a) HEK293 cells cotransfected with plasmid constructs NF-κB-Luc or AP-1-Luc (1 μg/mL each) and β-gal (as a transfection control) were treated with SB203580 (25 μM) in the presence or absence of TNF-α (20 ng/mL) for NF-κB activation or PMA (10 ng/mL) for AP-1 activation. Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer. **P < 0.01 compared with controls.

3. Results and Discussion

Peptide K5 is a representative peptide known to be self-assembled and to form nanofibers that can be used as 3D scaffolds for tissue engineering or drug delivery [14, 17]. Thus far, no one has tested whether this peptide itself can induce an immunological response, but it is important for us to determine whether this nanofiber is immunogenic prior to using it as a drug delivery system. Therefore, in this study, the regulatory activity of peptide K5 on macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses was examined under LPS treatment conditions.

Our data suggest that peptide K5 can act as a therapeutic molecule with anti-inflammatory properties. Thus, K5 suppressed TNF-α production in a concentration-dependent manner in both in RAW264.7 cells (Figure 1(a)) and in bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated by LPS (Figure 1(b)). The peptide also showed significant inhibition of PGE2 production in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 1(c)). However, peptide K5 did not suppress either NO release from LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells (Figure 1(d)) or phagocytic uptake of FITC-dextran by RAW264.7 cells (Figure 1(e)), indicating that not all macrophage activation pathways are blocked by the peptide. Because K5 did not induce cytotoxicity at up to 100 μg/mL under the conditions studied (Figure 1(f)), all inhibitory activities seem to be due to a specific pharmacological action. The suppressive activities were much stronger than or comparable to those of previously reported peptides such as an immunomodulatory peptide (CP), human β-defensin 3, HBD-2, and enantiomeric 9-mer peptide [33, 34]. Considering these points, it is reasonable that peptide K5 could be used as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic.

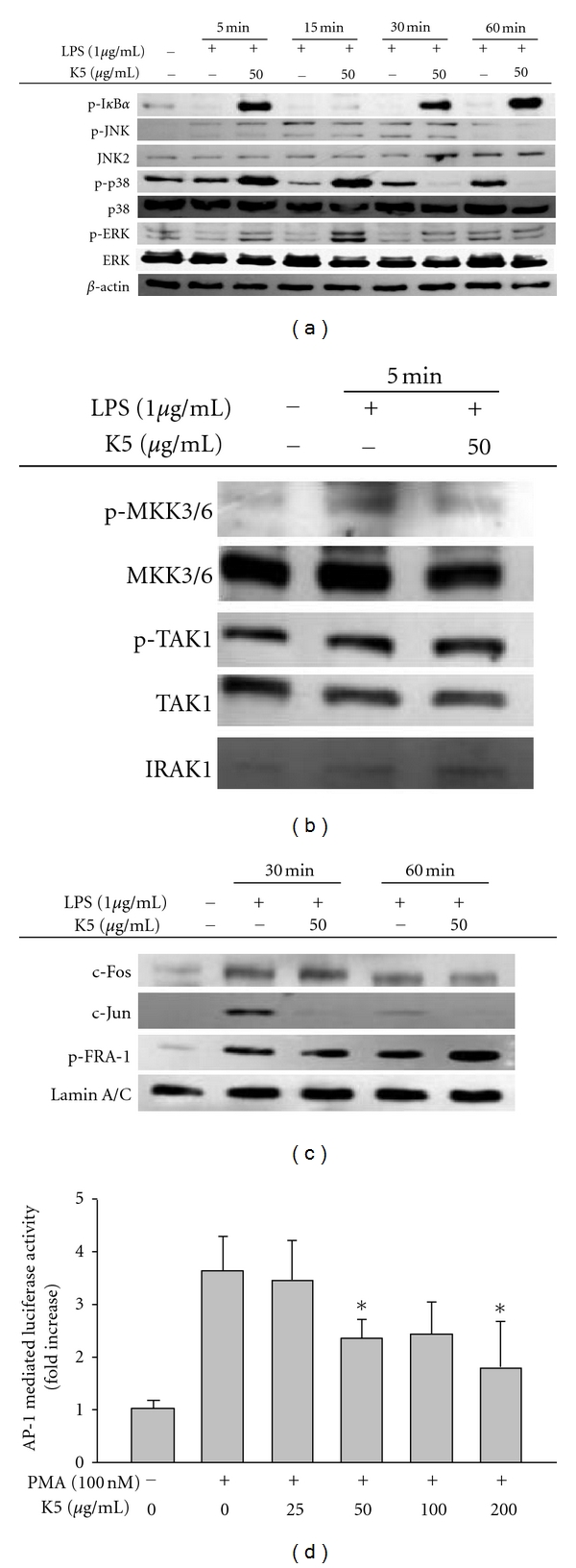

Because drug development requires understanding the molecular mechanism of a drug pharmacological action, we explored the inhibitory mechanism of peptide K5. To determine whether peptide K5 is able to suppress LPS-induced inflammatory responses at the transcriptional or translational levels, the mRNA levels of the inflammatory genes iNOS and COX-2 induced by LPS were measured by real-time PCR. Peptide K5 only blocked mRNA expression of COX-2 up to 60% at 100 μg/mL (Figure 2), implying that the inhibition of PGE2 production could be due to the blockade of transcriptional activation mediated by inflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1 [35]. To determine which transcription factors are targeted by peptide K5, nuclear proteins were analyzed. Interestingly, at 30 to 60 min, peptide K5 markedly diminished nuclear levels of c-Jun, while Fra-1 and c-Fos levels were not altered (Figure 3(a)), indicating that, among the different AP-1 family proteins, c-Jun could be a transcriptional target of peptide K5. To identify the molecular target of peptide K5, signaling events upstream of AP-1 translocation were continuously evaluated. Intriguingly, at 30 to 60 min, peptide K5 markedly suppressed the phosphorylation of p38, a critical enzyme for c-Jun translocation (Figure 3(b)), although this peptide remarkably enhanced p38 phosphorylation. Meanwhile, because there was no inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation, and rather it has been enhanced at 5, 30, and 60 min (Figure 3(b)), we expected that NF-κB, a major transcription factor activated under inflammatory conditions, would not be blocked by peptide K5. Indeed, the peptide did not suppress NF-κB translocation (data not shown). So far, we could not understand why the phosphorylation of IκBα was enhanced by the treatment of peptide K5. Whether this peptide is able to stimulate the activity of upstream signaling enzymes such as Akt and IκBα kinase (IKK) for this event or increase the protein level of IκBα by suppression of its cleavage pathway could be considered to be tested in the following experiments.

Figure 3.

Effect of peptide K5 on the activation of signaling events upstream of AP-1 activation. (a) and (b) Phosphoprotein or total protein levels of IκBα, ERK, p38, JNK, MKK3/6, TAK1, IRAK1, and β-actin from cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis using phosphospecific or total protein antibodies. (c) Levels of members of the AP-1 family (p-Fra-1, c-Jun, and c-Fos) in the nuclear fraction were determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies against total protein. (d) HEK293 cells cotransfected with plasmid constructs NF-κB-Luc, or AP-1-Luc (1 μg/mL each) and β-gal (as a transfection control) were treated with SB203580 (25 μM) in the presence or absence of TNF-α (20 ng/mL) for NF-κB activation or PMA (10 ng/mL) for AP-1 activation. Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer. *P < 0.05 compared with controls.

To determine whether peptide K5 can block events upstream of p38, the phosphorylation patterns of several upstream enzymes were investigated. Peptide K5 inhibited the phosphorylation of MKK3/6, an upstream kinase of p38 [36], at 5 min, while the activation of its upstream enzymes, TAK1 and IRAK1, as assessed by measuring phospho-TAK1 and a degraded form of IRAK1 [37], was not diminished (Figure 3(c)). Peptide K5 also showed an inhibitory pattern of luciferase activity mediated by AP-1 (Figure 3(d)), as assessed by a reporter gene assay with AP-1 promoter. Therefore, our data strongly suggest that the molecular target of peptide K5 seems to be a complex of AP-1 (c-Jun), p38, MKK3/6 kinase, and TAK1 in LPS signaling. However, whether this peptide can block TAK1 enzymatic activity either directly or indirectly is not yet clear. Detailed studies using purified TAK1 will be conducted to address this issue.

The functional significance of the p38/MKK3/6/TAK1 pathway for AP-1 activation and inflammatory responses has been well defined [36]. To confirm its role under our experimental conditions, a selective inhibitor of p38, SB203580, was employed and tested under the same conditions. Neither K5 nor the p38 inhibitor blocked NO production (Figure 4(b)). In contrast, SB203580 markedly suppressed both PGE2 (Figure 4(b)) and TNF-α production (data not shown), suggesting that the p38 pathway may be a critical component in regulating the release of PGE2 and TNF-α in LPS-treated macrophages.

In general, it is known that proteins and peptides are not able to penetrate the cell membrane due to their sizes and charges. Small hydrophobic molecules exhibiting anti-inflammatory activities, however, are membrane-permeable compounds and are expected to easily modulate cytosolic target enzymes. In this regard, the possibility that peptide K5 can be transported into the cytoplasm by a specific transporter seems plausible. Several receptors, such as PEPT1, OATP1A2, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1, have been identified as transporters of peptide molecules [38, 39]. Because some of these receptors, including PEPT1, have been reported to be involved in inflammatory responses, it is necessary to test whether these transporters and the relevant signaling pathways are critical for the pharmacology of peptide K5. Further studies will be conducted to address these points.

Unlike small-molecule drugs, the therapeutic use of peptide-based drugs is hindered by cost, stability, pharmacokinetics, and obscure targeting. Nonetheless, some peptides such as GLP-1 analogs, extracellular matrix protein-derived peptides such as acetylated Pro-Gly-Pro (Ac-PGP) [40], and integrin-binding N-terminal peptide [41] have been reported to have anticancer, antiseptic shock, and antitumorigenic activities and were subsequently developed as promising peptide drugs. Indeed, some peptide-type drugs have already been used as glycopeptide-type antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin) [42]. However, compared with small-molecule drugs having subnanomolar potency, it is difficult to develop a low-potency peptide into a drug. Recent studies have focused on developing special drug delivery apparatuses using peptides [14]. Peptide K5 is a candidate peptide for drug delivery; it is a self-assembling nanopeptide forming a hydrogel and is known to be generally nonimmunogenic, nonthrombogenic, and applicable to such noninvasive therapies as void filling [14, 18, 19]. Through these properties, self-assembling peptides have been nominated as scaffolds for 3D cell culturing systems, regenerative medicine applications, and drug delivery applications [43, 44]. Although such applicable features are sufficient to warrant use of these peptides, the anti-inflammatory property of peptide K5 could provide an additive benefit when used as an anti-inflammatory drug delivery system. In particular, because this peptide has been shown to block the p38/AP-1 pathway in the LPS/TLR4 response, drugs with inhibitory activities on the activation of NF-κB or IRF-3, which affect the production of NO and IFN-β, will help to synergize total anti-inflammatory responses. This hypothesis will be evaluated using several in vivo inflammatory models, such as DSS-induced colitis and collagen-type-II-generated arthritis.

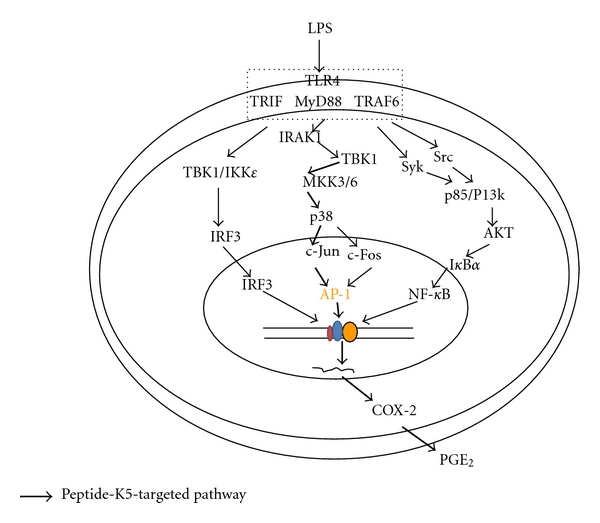

In summary, we have demonstrated that peptide K5 can strongly block macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses, such as the production of TNF-α and PGE2, during the activation of TLR4. In particular, peptide K5 selectively diminishes the activation of AP-1 by suppression of upstream signaling enzymes, such as MKK3/6 and TAK1 (Figure 5). Considering that this peptide is a self-assembling drug delivery carrier, it is possible that peptide K5 could be developed as a carrier of NF-κB inhibitory drugs and act synergistically to combat inflammation. To investigate this possibility, we plan to conduct additional in vivo efficacy tests using models of chronic inflammatory disorders (e.g., colitis and arthritis).

Figure 5.

Putative inhibitory pathway of LPS-activated inflammatory signaling responses by peptide K5.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by a grant (2010–2012) from Kangwon Technopark, Kangwon Province, Korea. W. S. Yang and Y. C. Park contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Kinne RW, Bräuer R, Stuhlmüller B, Palombo-Kinne E, Burmester GR. Macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Research. 2000;2(3):189–202. doi: 10.1186/ar86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens T, Babcock AA, Millward JM, Toft-Hansen H. Cytokine and chemokine inter-regulation in the inflamed or injured CNS. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;48(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leon CG, Tory R, Jia J, Sivak O, Wasan KM. Discovery and development of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonists: a new paradigm for treating sepsis and other diseases. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;25(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9571-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekine Y, Yumioka T, Yamamoto T, et al. Modulation of TLR4 signaling by a novel adaptor protein signal-transducing adaptor protein-2 in macrophages. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(1):380–389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda K, Akira S. Roles of Toll-like receptors in innate immune responses. Genes to Cells. 2001;6(9):733–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bresnihan B. Pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;26(3):717–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burmester GR, Stuhlmüller B, Keyszer G, Kinne RW. Mononuclear phagocytes and rheumatoid synovitis: mastermind or workhorse in arthritis? Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1997;40(1):5–18. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gracie JA, Forsey RJ, Chan WL, et al. A proinflammatory role for IL-18 in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;104(10):1393–1401. doi: 10.1172/JCI7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang TJ, Moon JS, Lee S, Yim D. Polyacetylene compound from Cirsium japonicum var. ussuriense inhibits the LPS-induced inflammatory reaction via suppression of NF-κB activity in RAW 264.7 cells. Biomolecules and Therapeutics. 2011;19(1):97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuhlmuller B, Ungethum U, Scholze S, et al. Identification of known and novel genes in activated monocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2000;43(4):775–790. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<775::AID-ANR8>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaëlsson E, Holmdahl M, Engström A, Burkhardt H, Scheynius A, Holmdahl R. Macrophages, but not dendritic cells, present collagen to T cells. European Journal of Immunology. 1995;25(8):2234–2241. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko HJ, Jin JH, Kwon OS, Kim JT, Son KH, Kim HP. Inhibition of experimental lung inflammation and bronchitis by phytoformula containing broussonetia papyrifera and lonicera japonica. Biomolecules and Therapeutics. 2011;19(3):324–330. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galler KM, Hartgerink JD, Cavender AC, Schmalz G, D'Souza RN. A customized self-assembling peptide hydrogel for dental pulp tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2012;18(1-2):176–184. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koutsopouios S, Unsworth LD, Nagai Y, Zhang S. Controlled release of functional proteins through designer self-assembling peptide nanofiber hydrogel scaffold. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(12):4623–4628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tysseling-Mattiace VM, Sahni V, Niece KL, et al. Self-assembling nanofibers inhibit glial scar formation and promote axon elongation after spinal cord injury. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(14):3814–3823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garreta E, Gasset D, Semino C, Borrós S. Fabrication of a three-dimensional nanostructured biomaterial for tissue engineering of bone. Biomolecular Engineering. 2007;24(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang S. Designer self-Aassembling peptide nanofiber scaffolds for study of 3-D cell biology and beyond. Advances in Cancer Research. 2008;99:335–362. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(07)99005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelain F, Unsworth LD, Zhang S. Slow and sustained release of active cytokines from self-assembling peptide scaffolds. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;145(3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagai Y, Unsworth LD, Koutsopoulos S, Zhang S. Slow release of molecules in self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffold. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;115(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyo S. The mechanism of poly I:C-induced antiviral activity in peritoneal macrophage. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 1994;17(2):93–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02974230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho JY, Baik KU, Jung JH, Park MH. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of cynaropicrin, a sesquiterpene lactone, from Saussurea lappa. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;398(3):399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim SI, Cho CW, Choi UK, Kim YC. Antioxidant activity and ginsenoside pattern of fermented white ginseng. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(3):168–174. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauwels R, Balzarini J, Baba M, et al. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. Journal of Virological Methods. 1988;20(4):309–321. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(88)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roh YS, Kim HB, Kang CW, Kim BS, Nah SY, Kim JH. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg3 against 24-OH-cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in cortical neurons. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(3):246–253. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JR, Oh DR, Cha MH, et al. Protective effect of polygoni cuspidati radix and emodin on Vibrio vulnificus cytotoxicity and infection. Journal of Microbiology. 2008;46(6):737–743. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim YO, Lee SW. Microarray analysis of gene expression by Ginseng water extracts in a mouse adrenal cortex after immobilization stress. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2011;35(1):111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon J, Kim S, Shim S, Choi DS, Kim JH, Kwon YB. Modulation of LPS-stimulated astroglial activation by Ginseng total saponins. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2011;35(1):80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin M, Park S, Pyo MY. Suppressive effects of T-412, a flavone on interleukin-4 production in T cells. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2009;32(11):1875–1879. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung KK, Lee HS, Cho JY, et al. Inhibitory effect of curcumin on nitric oxide production from lipopolysaccharide-activated primary microglia. Life Sciences. 2006;79(21):2022–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byeon SE, Lee J, Lee E, et al. Functional activation of macrophages, monocytes and splenic lymphocytes by polysaccharide fraction from Tricholoma matsutake. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2009;32(11):1565–1572. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-2108-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee YG, Lee WM, Kim JY, et al. Src kinase-targeted anti-inflammatory activity of davallialactone from Inonotus xeranticus in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;154(4):852–863. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HD, Ha SE, Kang JR, Park JK. Effect of Korean red ginseng extract on cell death responses in peroxynitrite-treated keratinocytes. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2010;34(3):205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varoga D, Klostermeier E, Paulsen F, et al. The antimicrobial peptide HBD-2 and the Toll-like receptors-2 and -4 are induced in synovial membranes in case of septic arthritis. Virchows Archiv. 2009;454(6):685–694. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee E, Kim JK, Shin S, et al. Enantiomeric 9-mer peptide analogs of protaetiamycine with bacterial cell selectivities and anti-inflammatory activities. Journal of Peptide Science. 2011;17(10):675–682. doi: 10.1002/psc.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Ghosh S. Molecular mechanisms of NF-κB activation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide through Toll-like receptors. Journal of Endotoxin Research. 2000;6(6):453–457. doi: 10.1179/096805100101532414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Chen JX, Liao R, et al. Sequential activation of the MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and MKK3/6-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediates oncogenic ras-induced premature senescence. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2002;22(10):3389–3403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3389-3403.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Li T, Sane DC, Li L. IRAK1 serves as a novel regulator essential for lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-10 gene expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(49):51697–51703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamai I. Oral drug delivery utilizing intestinal OATP transporters. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.07.007. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taub ME, Mease K, Sane RS, et al. Digoxin is not a substrate for organic anion-transporting polypeptide transporters OATP1A2, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1 but is a substrate for a sodium-dependent transporter expressed in HEK293 cells. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2011;39(11):2093–2102. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SD, Lee HY, Shim JW, et al. Activation of CXCR2 by extracellular matrix degradation product acetylated pro-gly-pro has therapeutic effects against sepsis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;184(2):243–251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0004OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seo DW, Saxinger WC, Guedez L, Cantelmo AR, Albini A, Stetler-Stevenson WG. An integrin-binding N-terminal peptide region of TIMP-2 retains potent angio-inhibitory and anti-tumorigenic activity in vivo. Peptides. 2011;32(9):1840–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preobrazhenskaya MN, Olsufyeva EN. Polycyclic peptide and glycopeptide antibiotics and their derivatives as inhibitors of HIV entry. Antiviral Research. 2006;71(2-3):227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horii A, Wang X, Gelain F, Zhang S. Biological designer self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffolds significantly enhance osteoblast proliferation, differentiation and 3-D migration. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(2, article e190) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JK, Anderson J, Jun HW, Repka MA, Jo S. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile-based nanofiber gel for bioresponsive cisplatin delivery. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2009;6(3):978–985. doi: 10.1021/mp900009n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]