Abstract

Most individuals who enter drug treatment programs are unable to maintain long-term abstinence. This problem is especially relevant for those presenting with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). In examining potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between ASPD and abstinence, one factor that may be especially useful is the personality variable of impulsivity. Thus, the current study examined ASPD status in relation to longest abstinence attempt among 117 substance use treatment-seeking individuals, considering the mediating role of five facets of impulsivity: urgency, perseverance, premeditation, control, and delay discounting. Results indicated that individuals with ASPD evidenced shorter previous abstinence attempts and lower levels of perseverance and control than those without ASPD. Further, lower levels of control were associated with shorter abstinence attempts. Finally, control mediated the relationship between ASPD and longest quit attempt. These results suggest the potential value of multiple facets of impulsivity in efforts to understand relapse and subsequent treatment development efforts.

Keywords: Antisocial Personality Disorder, impulsivity, abstinence, substance use treatment, treatment dropout

1. Introduction

Due to the high prevalence of illicit drug and alcohol use and subsequent costs to society, a great deal of research in the past two decades has focused on the development and evaluation of effective treatments. Although outcome studies show promise (Gossop, Marsden, Stewart, & Kidd, 2003; Hubbard, Craddock, Flynn, Anderson, & Etheridge, 1997), recent estimates indicate that a large number of individuals who enter drug treatment relapse within a matter of weeks or even days, and few of these individuals are able to recover abstinence thereafter (Hubbard et al., 1997; Ravndal, Vaglum, & Lauritzen, 2005). This problem is especially relevant for individuals diagnosed with Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD). Indeed, the presence of ASPD among substance using individuals is often associated with a poor prognosis for treatment outcomes across treatment settings (e.g., Arndt, McLellan, Dorozynsky, & Woody, 1994; Cacciola, Rutherford, Alterman, McKay, & Snider, 1996; Goldstein, et al., 2001; Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2003). As a salient example, a recent study reported that individuals with ASPD in residential substance use treatment had significantly earlier post-treatment failure at the post-treatment follow-ups than those without ASPD (Goldstein et al, 2001). Despite this increased probability of treatment failure associated with ASPD, there is a dearth of literature explicitly examining why individuals with ASPD are at an elevated risk for poor treatment outcomes. Therefore, investigating factors that might underlie or mediate the relationship between ASPD and poor treatment outcomes might indicate potential avenues for targeted treatment approaches.

In examining the potential underlying mechanisms of the relationship between ASPD and treatment failure, one variable that may be especially useful is that of trait-impulsivity. Impulsivity has not only been consistently found to be related to substance use disorders, (e.g., Allen, Moeller, Rhoades, & Cherek, 1998; Moeller, et al., 2001), but is also a distinguishing characteristic of ASPD (American Psychiatric Association [DSM-IV-TR], 2000). A number of studies indicate that compared to non-ASPD substance users, individuals with ASPD evidence higher levels of impulsivity (Moeller, et. al., 2001). Furthermore, other studies indicate that impulsivity is predictive of substance use treatment failure (Moeller, et al., 2001; Miller, 1991; Patkar, et al., 2004). Taken together, these studies suggest that the construct of impulsivity may explain the high rates of treatment failure among individuals with ASPD.

Despite the clearly established role of impulsivity in ASPD, substance use, and substance use treatment outcomes, one difficulty in interpreting these documented relationships is the multidimensional nature of impulsivity (Evenden, 1999; Monterosso, Ehrman, Napier, O’Brien, & Childress, 2001; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). Various conceptualizations of the construct of impulsivity have been proposed, including the inability to resist impulsive acts in the face of negative affect, susceptibility to boredom, lack of planfulness, preference for acting without regard to consequences, and the inability to delay gratification (Cloninger, Przybeck & Svrakic, 1991; Logan, Schachar, & Tannock, 1997; Whiteside, et al., 2005), among others.

Each of the aforementioned facets of impulsivity has been linked to ASPD, substance use, or indices of treatment failure. In a longitudinal study (Lynam & Miller, 2004), separate dimensions of impulsivity were found to be differentially associated with deviance and substance use in adolescence and adulthood. For instance, the compromised ability to withhold impulsive behavior in the presence of negative affect (termed Urgency) was related to substance use in adolescence. Similarly, the inability to consider potential consequences of behavior prior to acting (lack of Premeditation) was related to substance use and antisocial behavior. In contrast, the inability to persist during a boring or difficult task (lack of Perseverance), was not related to antisocial behavior or substance use across all assessment points. However, a study examining impulsivity as a predictor of substance use disorder diagnoses demonstrated that lack of perseverance conferred large effect sizes (Verdejo-Garcia, Bechara, Recknor, & Perez-Garcia, 2007). Furthermore, a similar construct, task-persistence, has been shown to be inversely related to substance use (Quinn, Brandon, & Copeland, 1996). Finally, the inability to be planful and deliberate (lack of Control) has been associated with substance use disorders (McGue, Slutske, & Iacono, 1999; Swendsen, Conway, Rounsaville, & Merikangas, 2002) and ASPD (Taylor & Iacono, 2007).

Behavioral measures of impulsivity such as delay discounting, or the tendency to prefer smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards have also been linked to ASPD, substance use severity, and treatment outcomes. Research indicates that drug users exhibit substantially high rates of delay discounting (Allen, et al., 1998; Coffey, Gudleski, Saladin, & Brady, 2003; Crean, de Wit, & Richards, 2000; Madden, Petry, Badger, & Bickel, 1997; Kirby & Petry, 2004; Petry, Kirby, & Kranzler, 2002; Bickel, Kirby, & Petry, 1999, Petry & Casarella, 1999; Vuchinich & Simpson, 1998). With respect to treatment outcome, higher levels of delay discounting have been found to predict shorter periods of abstinence from illicit drugs at follow-up in opiate addicts (Passetti, Clark, Mehta, Joyce, & King, 2008). Similarly, recent work indicates that substance abusers with ASPD discounted delayed rewards at higher rates than their non-ASPD substance-abusing counterparts (Petry, 2002).

The studies described above provide excellent documentation of the univariate relationships of the multiple dimensions of impulsivity and ASPD, as well as their relationships to substance use and treatment failure. However, to date, no substance use treatment outcome studies have explicitly examined the unique roles of different facets of impulsivity as related to treatment outcomes in individuals diagnosed with ASPD. Moreover, no studies have explicitly examined the mediational role of the multiple dimensions of impulsivity in the relationship between ASPD and substance use treatment failure. Thus, the current study sought to identify facets of impulsivity that may explain negative treatment outcomes in individuals with ASPD, with a focus on dimensions of impulsivity that have been shown to be related to either ASPD or substance use outcomes. Specifically, we examined a) facets of impulsivity uniquely related to ASPD and, b) the potentially mediating role of these types of impulsivity in the relationship between ASPD and longest abstinence attempt.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

As part of a larger study, 150 inpatient residents in a drug and alcohol abuse treatment center in the greater Washington DC metropolitan area completed questionnaire packets. Treatment at this center involves a mix of strategies adopted from Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous as well as group sessions focused on relapse prevention and functional analysis. The center requires complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol (including the prohibition of any form of agonist treatment such as methadone), with the exception of caffeine and nicotine; regular drug testing is provided and any use is grounds for dismissal from the center. Typical treatment lasts between 30 and 180 days. Aside from scheduled activities (e.g., group retreats, physician visits), residents are not permitted to leave the center grounds during treatment.

Thirty-three participants were excluded from analyses because of missing data on one or more of the variables of interest and/or issues of literacy. Casewise deletion was used in order to assure that all analyses were conducted on the same set of observations. Furthermore, the excluded participants did not differ from the included participants with respect to demographics, drug use, ASPD diagnosis, impulsivity variables or longest abstinence attempt. The final sample of 117 participants had a mean age of 41.6 (SD = 8.8). Sixty-three percent of the participants were male, and 94.2% were African-American, with the rest of the participants endorsing “Caucasian”. With regard to highest education level achieved, 20% of the participants had an education level of “less then high school”, 44.2 % had a “high school or equivalent” level, and 35.8% had “some college and above” level. The modal income was $0 - $9,999, and most were not living with a partner (74.2%).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1. Demographics and Longest Abstinence Attempt

A short self-report questionnaire was administered to obtain demographic information, as well as the number of days of the participants’ longest serious abstinence attempt prior to treatment (not counting detoxification).

2.2.2. Assessment of ASPD

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis II (SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, and Benjamin, 1997) was used to obtain ASPD diagnosis. All interviews were audio recorded, and reliability checks on all assessments were conducted. The last author (C.W.L.) listened to every 10th interview to ensure that assessor drift did not occur over time.

2.2.3. Level of substance Use

We assessed frequency of substance use in the past year prior to current treatment and lifetime heaviest substance use in the following nine categories of substances: (a) cannabis, (b) alcohol, (c) cocaine, (d) stimulants, (e) sedatives, (f) opiates, (g) hallucinogens (other than PCP), (h) PCP, and (i) inhalants. Responses were provided on a Likert-type scale (“Never” = 0 to “About every day” = 5).

2.2.4. Assessments of Impulsivity

In the current study, we utilized the Trait Negative Emotionality Superfactor and the Control subscale of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen, 1992). The Trait-Negative Emotionality (NEM) subscale measures the degree to which an individual is easily upset, has unaccountable mood changes, is nervous, tense, and feels unlucky, exploited or mistreated. The Control subscale was used at to assess individual differences in self-control and planfulness. Specifically, high scores on the Control scale indicate someone who is restrained, organized, and reflective. The measure has high internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = .85) and high 30-day test re-test reliability (r = .89). The MPQ has strong psychometric properties and the internal consistency in the current study was acceptable, ranging from .80 to .90 for NEM and Control, respectively.

To measure impulsive pathways and motivations for drug use, the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS; Whiteside, et al., 2005) was administered, which assesses four distinct facets of personality associated with impulsive behavior: urgency, (lack of) premeditation, (lack of) perseverance, and sensation seeking. The UPPS consists of 44 items and has been found to have good internal consistency as well as divergent and external validity. The alpha reliabilities have been found to be .87, .89, .85, and .83 for (lack of) Premeditation, Urgency, Sensation Seeking, and (lack of) Perseverance, respectively. Internal reliability in the current study was acceptable (α = .82, .86, .80, .78 for the respective subscales). The current study utilized the Urgency, Premeditation, and Perseverance scales. Although sensation-seeking is related to impulsivity, it has been shown to be a separate construct (Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007).

Developed by Kirby, et al. (1999), the Delay Discounting Questionnaire provides a measure of the degree to which an individual shows preference for small, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards. Alternatively, delay discounting may be seen as the rate at which the subjective value of deferred rewards decreases as a function of the delay until they are received. The Delay Discounting Questionnaire was provided in a paper and pencil format, consisting of a fixed set of 27 choices between smaller, immediate rewards and larger delayed rewards. For example, on the first trial participants were asked “Would you prefer $54 today, or $55 in 117 days?” Delays included in this questionnaire ranged from 7 to 186 days.

2.3. Procedure

Consent forms were obtained for each participant, after which participants completed the ASPD module of the SCID-II and the SCID-IV conducted by the second author (M.A.B). For the current study, a Ph.D. level clinician (C.W.L.) reviewed 10 percent of the interviews. No discrepancies were found between clinician and supervisor ratings. Following the interview, participants completed a self-report questionnaire packet including the measures described above. All procedures followed were in accordance with the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

3.0. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

According to SCID-II interviews, 34.5% (n = 40) of participants met criteria for ASPD. As shown in Table 1, preliminary analyses were conducted to explore the impact of demographic factors (including age, gender, education level, and income) and relevant clinical characteristics on the dependent variable (longest abstinence attempt), in order to identify potential covariates for later analyses. Ethnic/racial homogeneity within this sample prevented a meaningful analysis of this variable. For demographics, character pathology groups (ASPD vs. non-ASPD) did not differ as a function of gender, age, income, or marital status; however, a significant difference emerged in terms of education (χ2 (1, n = 117) = 10.71, p < .01), indicating significantly lower rates of high school or GED completion among individuals with ASPD (63%) compared to those without ASPD (37%). These results are presented in Table 2. Finally, character pathology groups did not differ on current or lifetime substance use in any drug category. However, a significant group effect was observed when these groups were compared on levels of trait negative affect (p = .002). Therefore, a dichotomous education variable was created (no high school diploma/GED vs. at least a high school diploma/GED) and included with trait negative affect in the subsequent analyses in order to statistically control for demographic and clinical differences in the dependent variables and in the key pathology groups.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations among key variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||||||

| 1. Age | --- | .05 | −.06 | −.13 | .03 | −.13 | .08 | .04 | .04 | .04 | .02 |

| 2. Gender | --- | .10 | .20* | −.00 | −.19* | −.21* | −.23* | −.13 | −.10 | .03 | |

| 3. Education | --- | .30* | .20* | −.23* | −.28* | −.15 | −.09 | .04 | .01 | ||

| 4. Income Clinical Correlates |

--- | .15 | −.21* | −22* | −.24* | −.16 | .14 | .02 | |||

| 5. Longest Abstinence Attempt |

−.013 | −.19* | −.13 | −.06 | .26** | .01 | |||||

| 6. Trait-NA Impulsivity |

-- | .21* | .49** | .30** | −.36** | −.16 | |||||

| 7. Perseverence | --- | .51** | .60** | −.60** | .04 | ||||||

| 8. Urgency | --- | .55** | −.58** | .04 | |||||||

| 9. Premeditation | --- | −.67** | .04 | ||||||||

| 10. Control | --- | .01 | |||||||||

| 11. Delay Discounting |

--- |

p < .05

p < .01.

Note: Gender was coded as male = 1 and female = 2; Education was coded as less than high school degree or GED = 1, high school degree and beyond = 2. Empty cells represent redundant correlations in the table.

Abbreviations: NA = negative affect.

Table 2.

Demographics and other drug use across character pathology groups.

| ASPD | Non-ASPD | Significance Level |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Gender (male) | 59.5% | 70.7% | .16 |

| Age | 41.9 (8.9) | 41.8 (8.9) | .71 |

| Education (less than high school) | 11.4% | 36.6% | .001 |

| Income (modal) | $0 - $9,999 | $0 - $9,999 | .92 |

| Marital Status (single) | 83% | 69.6% | .35 |

| Drug Use, Current | |||

| Alcohol | 55% | 54% | .53 |

| Marijuana | 32% | 25% | .25 |

| Crack/Cocaine | 61% | 67% | .32 |

| Opiates | 44% | 32% | .13 |

| Hallucinogens (other than PCP) | 5% | 3% | .41 |

| PCP | 10% | 4% | .18 |

| Drug Use, Heaviest Lifetime | |||

| Alcohol | 73% | 62% | .18 |

| Marijuana | 54% | 45% | .26 |

| Crack/Cocaine | 78% | 72% | .32 |

| Opiates | 48% | 34% | .09 |

| Hallucinogens (other than PCP) | 12% | 6% | .22 |

| PCP | 28% | 18% | .16 |

Note: Drug use percentages represent those who reported using the drug two or more times a week.

3.2. Guidelines for Establishing Mediation

Baron and Kenny (1986) outline the four steps to formally demonstrate mediation. First, the independent variable (ASPD status) must significantly predict the dependent variable (longest abstinence duration). Second, the independent variable (ASPD status) must significantly predict the mediator (impulsivity). Third, the mediator (impulsivity) must significantly predict the dependent variable (longest abstinence duration). Finally, when both the independent variable and the mediator are included in the same model to predict the dependent variable, the mediator must still significantly predict the dependent variable. If these criteria are met, then the effect of the independent variable must be reduced. If the effect of the independent variable is reduced to zero, full mediation has been established. In order to test the significance of the mediation model, we used a Sobel test (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993; Soper, 2011). To determine if impulsivity is a mediator (and more so, what type of impulsivity is the mediating variable), we followed these guidelines in the analyses below.

3.3. Longest Abstinence Attempt among ASPD Groups

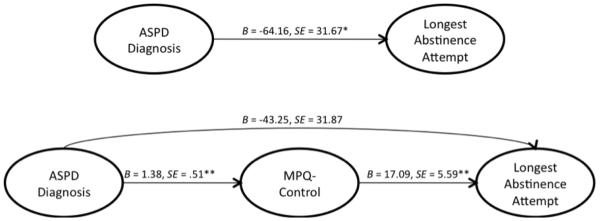

A univariate ANCOVA was conducted to examine between-group differences in longest abstinence attempt. Specifically, character pathology group (ASPD vs. non-ASPD) was included as independent variable (see Figure 1). Education and trait negative affect were included as covariates based on analyses reported above. As predicted, ASPD participants reported significantly shorter duration of abstinence attempts than non-ASPD participants (F(3, 113) = 4.11, p = .045, eta2 = .04).

Figure 1.

Results of meditational model with MPQ-control as a mediator between ASPD diagnosis and longest abstinence attempt (controlling for education and trait negative affect). Unstandardized regression coefficients presented; *p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001; Sobel Test: z = 2.03, p < .05

3.4. Impulsivity among ASPD Groups

To accomplish the second step in the requirements for mediation, a series of ANCOVAs were conducted. Each subtype of impulsivity (with the exception of delay discounting) was entered as a dependent variable, and ASPD status as the independent variable. Education and trait negative affect were included as covariates. A significant effect of ASPD status was found for UPPS-perseverance [F(3, 113) = 4.15, p = .044, eta2 = .04] and MPQ-control [F(3, 113) = 6.95, p = .010, eta2 = .056], but not for UPPS-urgency [F(4, 113) = .636, p = .427, eta2 = .005] or premeditation [F(3, 113) = 1.05, p = .307, eta2 = .01].

To determine if there are group differences in delay of gratification between ASPD and non-ASPD participants, we conducted a second analysis with the Delay Discounting Task as the dependent variable. Specifically, the k values were analyzed with a 2x3 repeated measures ANOVA with ASPD group as the between subject variable and magnitude of the delayed reward (low, med, & high) as the within subject variable. There was neither a significant main effect of ASPD group [F(2, 100) =.086; p = .77], nor significant effects of reward magnitude [F(1, 100) = 1.42; p = .24].

3.5. Mediation of Longest Abstinence Attempt by Impulsivity

A set of partial correlations was conducted for the relationship between longest abstinence attempt, and MPQ-control and UPPS-perseverance. As above, education and trait negative affect were entered as covariates. A significant positive correlation was observed between longest abstinence attempt and MPQ-control (r = 0.28, p = .003), but not UPPS-perseverance (r = −.15, p = .119). As such, only MPQ control could be considered to have fulfilled three of the four criteria for mediation and thus, was the only variable entered into the mediation model below.

In the final step, MPQ-control was added as a covariate to the previously described ANCOVA, where ASPD was the independent variable and longest abstinence attempt was the dependent variable. The previous covariates (education and trait-negative affect) also were retained. A significant effect of MPQ-control was observed, F(4, 112) = 6.95, p = .010, eta2=.058, which indicates that impulsivity is a potential mediator. Moreover, the effect of ASPD was reduced and was no longer significant, F(4, 112) = 1.84, p = .177, eta2= .016). Providing support for the mediating role of MPQ-control in this relationship, the Sobel mediation test (indicating whether the indirect effect of the predictor on the criterion via the mediator is significantly different from zero) indicated that the indirect effect of ASPD status on longest abstinence attempt was significant (z = 2.03, p < .05). The results of the mediation model are presented in Figure 1.

4.0. Discussion

Prior studies investigating ASPD and substance use treatment outcomes have demonstrated that individuals with ASPD are at significantly greater risk for substance use and substance use treatment failure compared to those without ASPD. Moreover, the construct of impulsivity has been found to be related ASPD (Moeller, et al., 2001) and treatment failure (Miller, 1991; Moeller, et al., 2001; Patkar, et al., 2004). However, given the focus of prior studies on broad conceptualizations of impulsivity despite its multidimensional nature, it is not clear which facets of impulsivity may be responsible for negative substance use treatment outcomes among individuals with ASPD. Therefore, this study sought to investigate the relationship between multiple facets of impulsivity and longest abstinence attempt as well as which facets may be responsible for poor treatment outcomes among individuals with ASPD.

First, our results indicated that that ASPD was associated with shorter lengths of abstinence than those without ASPD, a finding consistent with previous reports of higher levels of treatment failure in this population (Arndt, et al., 1994; Cacciola, et al., 1996; Goldstein, et al., 2001; Grella, et al., 2003). Regarding the univariate associations of ASPD and impulsivity, the disorder was related to low perseverance and control, but not affect-driven impulsivity (Urgency), lack of forethought (Premeditation), and the tendency to prefer immediate small rewards over delayed larger rewards (delay discounting). Of note, the lack of a relationship between ASPD and premeditation is somewhat in contrast to previous work indicating that premeditation in particular predicts delinquency over time (Lynam et al., 2004). This discrepancy may be explained by the differences in sample and measurement across the two studies. Notably, Lynam and Miller (2004) utilized non-clinical undergraduate samples, and focused on predicting delinquency (defined by instances of antisocial behaviors such as truancy, stealing, fighting, etc.); in contrast, the current study utilized an older clinical sample, and focused on a categorical diagnosis of ASPD.

In the current study, a behavioral measure of the tendency to prefer smaller immediate rewards (delay discounting) was not related to ASPD, nor was it related to the longest abstinence attempt, in contrast to previous robust findings linking delay discounting to ASPD (Petry, 2002), substance use, and alcohol use severity (Coffey, et al., 2003; Madden, et al., 1997; Vuchinich, et al., 1998). The current finding suggests that delay discounting may not sufficiently characterize behavioral processes involved in maintaining abstinence (in contrast to those involved in substance use per se).

Although perseverance and control were both related to ASPD status and early treatment failure, a mediational analysis of the relationship of ASPD and treatment failure indicated that only the dimension of Control functioned as a mediator. This finding suggests that although ASPD is associated with low levels of planfulness and persistence during boring or difficult tasks, only the trait of being deliberate, anticipating, and planful may determine an ASPD-diagnosed individual’s success at remaining abstinent. Interestingly, the finding that persistence in the face of emotional and environmental obstacles (perseverance) was not related to treatment failure is somewhat counterintuitive, considering the various challenges inherent in early abstinence, including withdrawal and resisting cravings and social pressure to use substances. Nevertheless, Lynam and Miller (2004) did not find a relationship between perseverance and substance use across numerous assessment points, indicating that the current findings are likely to be authentic. Thus, the current findings identify the trait of being deliberate, anticipating, and planful as a facet of impulsivity that may be responsible for treatment success, thereby isolating a possible mechanism for intervention that may increase success at maintaining abstinence in individuals with ASPD.

Although the current findings are interesting and clinically relevant, there are a number of limitations that should be noted. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits the ability to infer causal relationships. Second, although the extension of this work to an underserved sample is a strength of this study, it also introduces limitations to the generalizability of these findings. Consequently, our findings in a sample of inner-city, primarily African-American men and women in residential substance use treatment may not generalize to ASPD patients in general.

Third, there were limitations posed by the delay discounting measure. Specifically, the presence of a ceiling effect in delay discounting scores may have compromised sample variability. Moreover, perhaps real-reward (see Green & Myerson, 2004) or real-time measures of delay discounting (see Reynolds, 2006) that utilize actual money and/or vouchers, rather than hypothetical rewards may demonstrate more ecologically validity and thus perhaps better predictive utility with respect to abstinence as opposed to simply substance use. Nevertheless, previous research has demonstrated a strong association between hypothetical and real-reward assessments (Epstein, Richards, Saad, Paluch, Roemich, & Lerman, 2003), suggesting that these findings were not likely due to the method of assessing delay discounting.

Finally, all measures used in this study were self-reported and retrospective. Perhaps real-time behavioral measures of impulsivity would yield more valid assessments of each facet. As such, the heavy reliance on self-report methodology in assessing constructs which may be influenced by individuals’ willingness and/or ability to accurately report on their history of relapse or trait-impulsivity may pose limits to internal validity. Therefore, the use of a multi-method assessment of each impulsivity facet is warranted in addition to independent verification of relapse.

Despite limitations, the current study begins to establish the exact nature of the processes involved in substance use treatment failure among individuals with ASPD. This method is consistent with translational approaches to substance use treatment research. Along these lines, the identification of basic mechanisms underlying poor treatment outcomes may assist in creating integrative intervention approaches that will ultimately reduce rates of treatment failure among individuals with ASPD.

Research Highlights.

-

-

Control mediated the relationship between ASPD and longest abstinence attempt

-

-

Lower levels of perseverance was associated with ASPD but did not mediate this relationship

-

-

Urgency, premeditation and delay discounting did not mediate this relationship

Statement 4: Acknowledgements

The authors thank Walter Askew, Pinque Alston, and Michelle Williams of the Salvation Army Harbor Light Residential Treatment Center of Washington, DC, for assistance with participant recruitment.

Statement 1: Role of Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R36 DA21820 awarded to the second author. NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement 2: Contributors

Marina A. Bornovalova and Adria J-M Trotman designed the study and wrote the protocol. Marsha N. Sargeant and Marina A. Bornovalova conducted literature searches, provided summaries of previous research studies, and conducted the statistical analyses. Marsha N. Sargeant, Marina A. Bornovalova, and Adria J-M Trotman wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Statement 3: Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen TJ, Moeller FG, Rhoades HM, Cherek DR. Impulsivity and history of drug dependence. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 1998;50(2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Revised 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt IO, McLellan AT, Dorozynsky L, Woody GE. Desipramine treatment for cocaine dependence: Role of antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1994;182(3):151–156. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, Alterman AI, McKay JR, Snider EC. Personality disorders and treatment outcome in methadone maintenance patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1996;184(4):234–239. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Švrakić DM. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: U.S. normative data. Psychological Reports. 1991;69(3, Pt 1):1047–1057. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11(1):18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean JP, de Wit H, Richards JB. Reward discounting as a measure of impulsive behavior in a psychiatric outpatient population. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8(2):155–162. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Richards JB, Saad FG, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN, Lerman C. Comparison between two measures of delay discounting in smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11(2):131–138. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R, Bigelow C, McCusker J, Lewis BF, Mundt KA, Powers SI. Antisocial behavioral syndromes and return to drug use following residential relapse prevention/health education treatment. The American Journal Of Drug And Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27(3):453–482. doi: 10.1081/ada-100104512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Kidd T. The National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS): 4-5 year follow-up results. Addiction. 2003;98(3):291–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A Discounting Framework for Choice With Delayed and Probabilistic Rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(5):769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser Y-I. Followup of cocaine-dependent men and women with antisocial personality disorder. Journal Of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, Anderson J, Etheridge RM. Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99(4):461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Schachar RJ, Tannock R. Impulsivity and inhibitory control. Psychological Science. 1997;8(1):60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller JD. Personality Pathways to Impulsive Behavior and Their Relations to Deviance: Results from Three Samples. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2004;20(4):319–341. [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control patients: Drug and monetary rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5(3):256–262. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: II. Alcoholism versus drug use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(3):394–404. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. Predicting relapse and recovery in alcoholism and addiction: Neuropsychology, personality, and cognitive style. Journal Of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1991;8(4):277–291. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(91)90051-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J. The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. Journal Of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;21(4):193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterosso J, Ehrman R, Napier KL, O’Brien CP, Childress AR. Three decision-making tasks in cocaine-dependent patients: Do they measure the same construct? Addiction. 2001;96(12):1825–1837. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9612182512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passetti F, Clark L, Mehta MA, Joyce E, King M. Neuropsychological predictors of clinical outcome in opiate addiction. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94(1-3):82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Murray HW, Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Vergare MJ. Pre-Treatment Measures of Impulsivity, Aggression and Sensation Seeking Are Associated with Treatment Outcome for African-American Cocaine-Dependent Patients. Journal Of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23(2):109–122. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: Relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2002;162(4):425–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Casarella T. Excessive discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers with gambling problems. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Kirby KN, Kranzler HR. Effects of gender and family history of alcohol dependence on a behavioral task of impulsivity in healthy subjects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(1):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EP, Brandon TH, Copeland AL. Is task persistence related to smoking and substance abuse? The application of learned industriousness theory to addictive behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4(2):186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ravndal E, Vaglum P, Lauritzen G. Completion of Long-Term Inpatient Treatment of Drug Abusers: A Prospective Study from 13 Different Units. European Addiction Research. 2005;11(4):180–185. doi: 10.1159/000086399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: Relations to drug use and gambling. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17(8):651–667. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280115f99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper DS. Sobel Test Calculator for the Significance of Mediation. 2011 [Online Software]. Available from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc3.

- Swendsen JD, Conway KP, Rounsaville BJ, Merikangas KR. Are personality traits familial risk factors for substance use disorders?: Results of a controlled family study. The American Journal Of Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1760–1766. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Iacono WG. Personality trait differences in boys and girls with clinical or sub-clinical diagnoses of conduct disorder versus antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(4):537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Waller NG. Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multi-dimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota; 1992. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, Pérez-García M. Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(2-3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6(3):292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19(7):559–574. [Google Scholar]