Abstract

Modulation of cell : cell junctions is a key event in cutaneous wound repair. In this study we report that activation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor disrupts cell : cell adhesion, but with different kinetics and fates for the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein and for E-cadherin. Downregulation of desmoglein preceded that of E-cadherin in vivo and in an EGF-stimulated in vitro wound reepithelialization model. Dual immunofluorescence staining revealed that neither E-cadherin nor desmoglein-2 internalized with the EGF receptor, or with one another. In response to EGF, desmoglein-2 entered a recycling compartment based on predominant colocalization with the recycling marker Rab11. In contrast, E-cadherin downregulation was accompanied by cleavage of the extracellular domain. A broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor protected E-cadherin but not the desmosomal cadherin, desmoglein-2, from EGF-stimulated disruption. These findings demonstrate that although activation of the EGF receptor regulates adherens junction and desmosomal components, this stimulus downregulates associated cadherins through different mechanisms.

1. Introduction

During cutaneous wound repair, epidermal cells at the wound margin undergo phenotypic and functional changes including increased proliferation, migration, and a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) characterized by disruption of cell : cell junctions, changes in cell : substrate adhesion, and retraction and reorganization of the cytoskeleton [1–3]. Kalluri and Weinberg proposed three sub-classifications of EMT with type 2 EMT associated with wound healing, tissue regeneration, and organ fibrosis [4]. An essential aspect of type 2 EMT is that once repair is achieved epithelial phenotype and tissue integrity is restored. A hallmark of successful wound repair is the reestablishment of cell : cell junctions and barrier function, thereby illustrating dynamic modulation of adherens junctions and desmosomes during wound reepithelialization. In mouse epidermis, a decrease in E-cadherin is evident 3 days after wounding in full-thickness incisional or excisional wound models with subsequent protein restoration upon wound closure [5]. Blocking E-cadherin function with antibody caused uneven wound margins and disruption of the reorganizing actin cytoskeleton in mouse epidermis [6], demonstrating the importance of E-cadherin in wound repair. Similarly, the dissolution of hemidesmosomes, which connect the cell to the extracellular matrix, and desmosomes responsible for cell : cell contacts occurs during wound healing [7, 8] but little is known about modulation of desmosomal cadherins during wound repair.

A number of mechanisms have been reported to regulate the assembly and disassembly of adherens junctions and desmosomes in cells including phosphorylation of junctional components [9–12], cadherin cleavage [13–18], and endocytic mechanisms [19–26]. Certain signaling molecules such as PKC-α are expressed and activated at the wound margin and contribute to the loss of desmosomal adhesion [27]. The epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor is another important regulator of wound repair. EGF receptor expression is elevated at the leading edge of healing wounds in mice [28, 29] and humans [29], and EGF stimulates wound repair in vivo [30–32]. Furthermore, keratinocyte migration in vitro and epithelial outgrowth in vivo are decreased in EGF receptor null skin [30] indicating that EGF receptor activity is important for optimal wound repair. Activation of the EGF receptor also induces expression of transcriptional regulators of EMT such as Snai2 and regulates junctional assembly and disassembly in keratinocytes [12, 33–38]. It remains unclear how activation of these signaling pathways affect the junctional stability of both desmosomes and adherens junctions to facilitate reepithelialization.

In this study, we investigated the effects of EGF receptor activation on the fate of E-cadherin and desmoglein-2, a desmosomal cadherin that is elevated in healing wounds [39]. We find that downregulation of desmoglein precedes that of E-cadherin in vivo and in EGF-stimulated in vitro wound reepithelialization models. Importantly, we find evidence for differential regulation of adherens junctions and desmosomal complex proteins as a consequence of EGF receptor activation. Furthermore, EGF-stimulated downregulation of E-cadherin and demsoglein-2 displays distinct temporal and spatial patterns and involves different mechanisms. These findings indicate that the same stimulus leads to different outcomes for classical versus desmosomal cadherins in keratinocytes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Line and Reagents

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) 12F cells were originally derived from a tumor of the facial epidermis and generously provided by Dr. William A. Toscano, Jr. (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN). SCC 12F cells are nontumorigenic and express EGF receptor levels similar to those detected at the margins of healing wounds. SCC 12F cells were maintained on 10 cm2 plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium : Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture (DMEM : F-12) containing 5% (v/v) iron-supplemented defined calf serum (HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Logan UT), 2 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U/mL, streptomycin, 50 μg/mL). For all experiments involving growth factor addition, SCC 12F cells were placed into DMEM : F-12 containing 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 24 hours prior to growth factor addition. Murine epidermal growth factor (EGF) was obtained from Biomedical Technologies Inc. (Stoughton, MA). GM6001X was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). AG1478 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). DMEM : F-12, BSA, Penicillin/Streptomycin, and L-glutamine were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

129 Young adult male mice were shaved and depilated using Nair (Church and Dwight, Princeton, NJ). Two days later, mice were anesthetized, skin of the upper dorsum was tented, and paired 3 mm-diameter excisional wounds were introduced using a sterile disposable biopsy punch. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation 48 hours later. Skin containing the wound sites and underlying muscle was removed, spread on thin cardboard, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 μm. For immunohistochemistry, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by a 10-minute incubation in aqueous 3% H2O2, and microwave antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Nonspecific antibody binding was blocked using Biocare Blocking Reagent (Concord, CA). For E-cadherin immunohistochemistry, slides were incubated for 1 hour in a 1 : 50 dilution of a rabbit polyclonal antibody (sc7870, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), then for 30 minutes with Envision plus labeled polymer-anti-rabbit-HRP (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Desmoglein was detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody (CBL174, Millipore, Billerica, MA) diluted 1 : 100 for a 1-hour incubation, followed by a 15-minute incubation with biotinylated rabbit-anti-mouse F(ab)' (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY) diluted 1 : 250 and a 30-minute incubation with SA-HRP (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA). All incubations were performed at room temperature, and immunoreactivity was detected using diaminobenzidine as chromagen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and cover-slipped.

2.3. In Vitro Wound Healing Assay

For evaluation of in vitro reepithelialization, confluent cell monolayers were deprived of serum and growth factors for 24 hours, and a cell-free area was introduced by scraping the monolayer with a standard dimension blue pipette tip (USA Scientific, Ocala, FL) followed by extensive washing to remove cellular debris. In vitro reepithelialization was monitored by repopulation of the cleared area (wound width typically between 200–300 mm) with cells over time either in the presence or absence of the EGF receptor inhibitor AG1478.

2.4. Immunoblotting of Protein and Conditioned Medium

Cells were lysed either with SDS collection buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A) to collect total protein, or by subcellular fractionation. For subcellular fractionation, cells were lysed with 0.05% saponin collection buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 0.05% saponin, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A) and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm; the resulting supernatant represented the saponin, or cytoplasmic, fraction. The pellet was then fully resuspended in 1% triton collection buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A) and then centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was labeled the triton soluble, or membrane-associated fraction. Finally, the remaining pellet was fully resuspended in 1% SDS collection buffer, and this was labeled the triton insoluble, or cytoskeletal-associated (junction bound) fraction. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) colorimetric assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal quantities of protein were fractionated on 8% (w/v) SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Conditioned medium was collected from 6 well plates (1 mL total volume) and then concentrated using a centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with a 30,000 molecular weight cutoff. The retentate was collected and resolved on an 8% (w/v) SDS polyacrylamide gel, then transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Immunoblotting was performed as described below. Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature before the addition of primary antibody. Primary antibodies [E-cadherin (clone NCH-38, Dakocytomation, Carpinteria, CA), E-cadherin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), desmoglein-2 (clone 6D8, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and alpha-catenin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA)] for western blots were used at 1 : 1000 dilution and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The membranes were washed with TBST three times, and secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase labeled goat anti-mouse from Promega (Madison, WI), at a dilution of 1 : 10,000 in 5% (w/v) milk was added for 1 hour at room temperature. The membranes were washed with TBST three times and developed using the SuperSignal chemiluminescent detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Visualization and densitometry of the blots were obtained with the Kodak Image Station 440 System (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA).

2.5. Immunofluorescence

SCC 12F cells were seeded in a Lab Tek II chamber slide system (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL). Cells were transferred to serum-free medium and then treated with 20 nM EGF for various times, or pretreated with the broad spectrum MMP inhibitor GM6001X for 30 minutes prior to addition of EGF. To probe for junctional proteins, cells were fixed with cold dry methanol for 2 minutes, or alternatively with freshly prepared paraformaldehyde (3.7%) for 10 minutes. Paraformaldehyde slides were triton-permeabilized for an additional 5 minutes. The slides were then blocked in 3% (w/v) BSA in complete PBS (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.8 mM magnesium chloride and 0.18 mM calcium chloride) at 37°C in a humidified chamber. For detection of lysosomal colocalization, Lysotracker (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added at a 1 : 250 dilution to live cells 2 hours before fixation. Primary antibodies were used at a 1 : 100 dilution and included: beta-catenin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), plakoglobin, caveolin-1, pancytokeratin (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), E-cadherin (HECD-1 clone), desmoglein-2 (clone 6D8, Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), EEA1 (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO), epidermal growth factor receptor (Upstate, Chicago, Il.), rab11 (rabbit polyclonal Ab), and rab7 (chicken polyclonal Ab), both kindly provided by Dr. Angela Wandinger-Ness, University of New Mexico. Primary antibody was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Slides were washed three times in complete PBS; then a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added at a 1 : 300 dilution and was allowed to incubate for 1 hour at 37°C in a humidified chamber. Actin staining was obtained by incubating with TRITC-labeled Phalloidin (0.5 μg/mL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were washed three times in complete PBS then mounted with a coverslip using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Images were obtained with an inverted microscope (Olympus IX70, Melville NY) and MagnaFire software 2.1 (Optronics, Goleta, CA) or with a Zeiss confocal Microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

2.6. PCR

RNA was isolated using 0.5 mL Trizol (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA. All PCR reagents were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Primers were ordered from Sigma-Genosys (The Woodlands, TX) and included the following: E-cadherin (Forward, GGGTGACTACAAAATCAATC, Reverse, GGGGGCAGTAAGGGCTCTTT), desmoglein-2 (Forward, CACTATGCCACCAACCACTG, Reverse, TTAGGCATGGCCAGAGTAGG), and 18s rRNA (Forward, AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG, Reverse, CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA). E-cadherin amplification was performed with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 4 minutes, followed by 38 cycles with a denaturing step at 94° for 30 seconds, an annealing step of 55°C for 30 seconds and an extension step of 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension step of 72°C for 4 minutes. Desmoglein-2 amplification was performed as above, with the annealing step of 64°C for 30 seconds, for a total of 30 cycles. 18s rRNA amplification was performed with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 4 minutes, followed by 20 cycles with a denaturing step at 94° for 30 seconds, an annealing step of 55°C for 30 seconds and an extension step of 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension step of 72°C for 4 minutes. GoTaq Flexi products (Promega, Madison, WI) were used according to the manufacturer's protocols. The resulting PCR products were loaded onto a 3% agarose gel (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA). SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added for staining purposes, and the gel was imaged on a Kodak Image Station 440 System (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results from different treatment groups in immunoblotting experiments were compared by Welsh's t-test, and the value for statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Wound Margins In Vivo Show a Decrease in E-Cadherin and Desmoglein at the Migrating Epithelial Tip

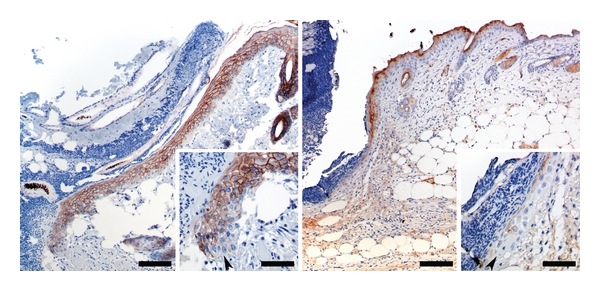

Both E-cadherin and desmoglein were studied in an in vivo incisional wound model. After 48 hours after incision, the epithelium stained for both E-cadherin (Figure 1, left panel) and desmoglein (Figure 1, right panel), throughout a majority of the intact epithelium. However, at the migrating wound edge, both E-cadherin and desmoglein displayed a marked decrease in staining (Figure 1, insets of both panels, E-cadherin was present in all but a few cells at the migrating tip, demonstrating the persistence of this cadherin throughout the epithelium even 48 hours post injury. Desmoglein, however, is largely absent from the migrating front. Clearly, a downregulation of both cadherins occurs as a normal response to wounding in vivo, although the degree of downregulation of each cadherin differs 48 hours post injury.

Figure 1.

Cadherin staining 48 h postincisional wounding in vivo. Left Panel: E-cadherin immunoreactivity at wound margin 48 h after introduction of an incisional wound. Bar = 150 μm. Inset: Higher magnification of the advancing edge of epithelium. Note that E-cadherin immunoreactivity is present in all but a few cells at the very tip of the migrating epithelium. Bar = 50 μm. Right Panel: Desmoglein immunoreactivity at wound margin 48 h after introduction of an incisional wound. Bar = 150 μm. Inset: Higher magnification of the advancing edge of epithelium. Note that desmoglein immunoreactivity is largely absent from the tip of the migrating epithelium. Bar = 50 μm.

3.2. EGF Receptor Activation Is Required for Junctional Disruption at Wound Margins

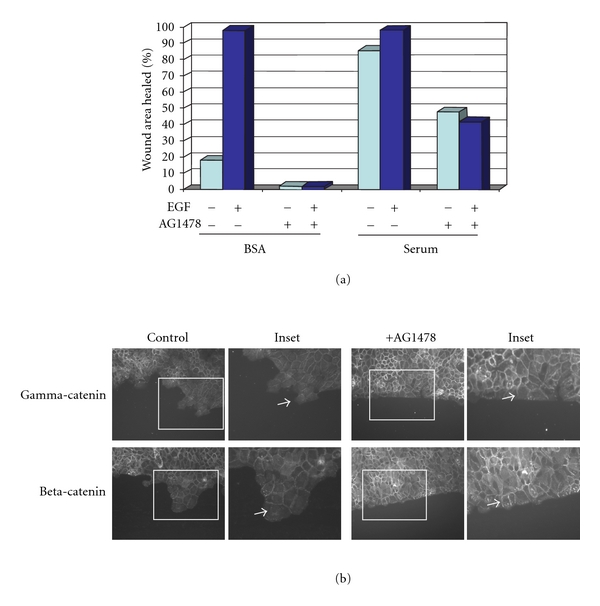

EGF receptor activation stimulates wound repair in vivo [30, 40] and disrupts junctional complexes in vitro [41, 42]. We conducted in vitro wound closure assays using SCC 12F cells, a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma line [43] with EGF receptor levels comparable to those at wound margins [36] to investigate the status of junctional complexes at an in vitro wound border as a function of EGF receptor activity (Figure 2). Modest wound closure occurs in serum-free conditions, and exogenous EGF greatly stimulates the response. Both basal and EGF-stimulated migration into the wound area was inhibited by the EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (Figure 2(a)). The loss of basal migration is likely due to inhibition of the autocrine EGF receptor activation in this system [44]. Junctional disruption was detected at wound margins as evidenced by the loss of catenin border staining under basal (no exogenous EGF) conditions (Figure 2(b), arrows). In contrast, EGF receptor inhibition led to retention of catenin staining at cell borders of cells at the wound edge, suggesting that junctional integrity was retained (Figure 2(b), arrowheads). Similar results were obtained for E-cadherin and desmoglein-2 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Junctions at the wound margin are retained upon EGF receptor inhibition. Cells were grown to confluence, placed in serum-free medium overnight, and then a wound was introduced with a pipette tip. Cells were washed 3X with PBS, then placed in serum-free medium +/−20 nM EGF and +/−5 μM of the selective EGF receptor inhibitor AG1478 as indicated for 24 h. (a) The area of wound closure was measured using ImagePro software. (b) After wounding, cells were fixed and immunostained for either gamma-catenin (plakoglobin) or beta-catenin. Note the loss of border staining is limited to the wound edge (see arrows). Upon EGF receptor inhibition, junctional proteins are apparent at the wound edge (see arrowheads).

3.3. Downregulation of Junctional Proteins by EGF Receptor

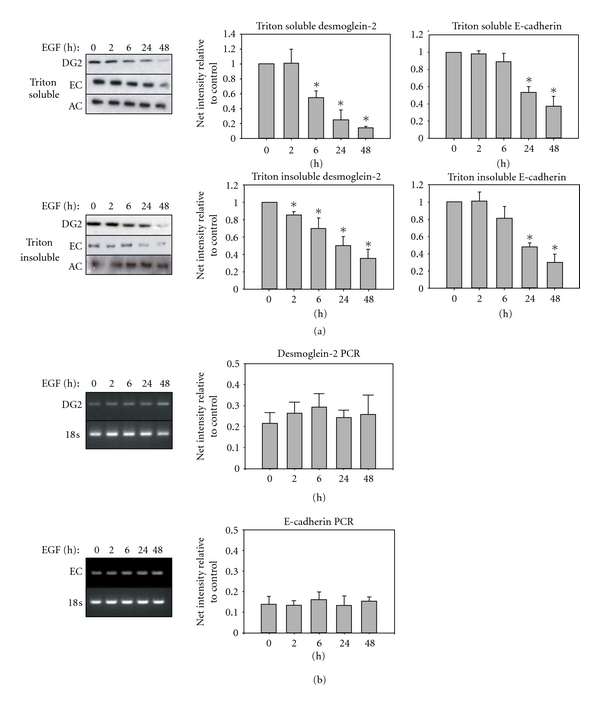

EGF receptor activity has been reported to modulate certain junctional proteins, leading to downregulation and protein degradation [9, 45–47]. The catenins are well studied, but less is known regarding the fate of cadherins in response to EGF receptor activation. Using sequential detergent extraction, we compared protein levels of membrane-associated (triton soluble) versus junction bound (triton insoluble) cadherins. Extended exposure to EGF led to loss of both the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2 and adherens junction protein E-cadherin from the cell membrane and junction-associated protein pools (Figure 3). Since transcriptional repression of E-cadherin is one reported mechanism of down-regulation [48, 49], we examined mRNA levels for E-cadherin and desmoglein-2 in response to EGF (Figure 3(b)). In a time course that spanned 48 hours, no change in either E-cadherin or desmoglein-2 transcripts occurred. In agreement with the in vitro wound model, a decrease in the protein levels of both beta-catenin and plakoglobin was detected in the membrane- and junction-associated protein fractions (data not shown). Interestingly, not all junctional components were affected, as the levels of the adherens junctional linker protein alpha-catenin were retained following EGF treatment (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

EGF regulation of cadherin proteins in membrane and cytoskeleton-associated pools. Cells were grown to subconfluence, placed in serum-free medium overnight, and then treated with EGF for the indicated times. DG2: desmoglein-2, EC: E-cadherin, AC: alpha-catenin. (a) Sequential detergent extraction separates the triton soluble (membrane-associated) fraction, from the triton insoluble, (cytoskeletal, or intact junctional) fraction. Blots are representative of a minimum of three separate experiments. Bar graphs represent the densitometric quantification of each lane normalized to no treatment control, with asterisks indicating statistical significance. (P < 0.05) (b) Cells were treated with or without EGF for the indicated times, and mRNA level was measured by PCR. Bar graphs represent the densitometric quantification of bands normalized to no treatment control.

There was a notable difference in the time dependence for loss of cadherin protein in the membrane-associated versus junction-associated protein pools in response to EGF. The triton soluble, membrane-associated fraction, showed a decrease in desmoglein-2 protein as early as 6 hours, whereas E-cadherin was not significantly decreased until 24 hours after EGF exposure (Figure 3(a), asterisks P < 0.05). Similarly, in the triton insoluble fraction, a significant decrease in desmoglein-2 protein was evident at 2 hours post-EGF treatment whereas little change in E-cadherin was evident until later time points (Figure 3(b), asterisks P < 0.05). These findings indicate that E-cadherin and desmoglein-2 are not coordinately regulated during reepithelialization.

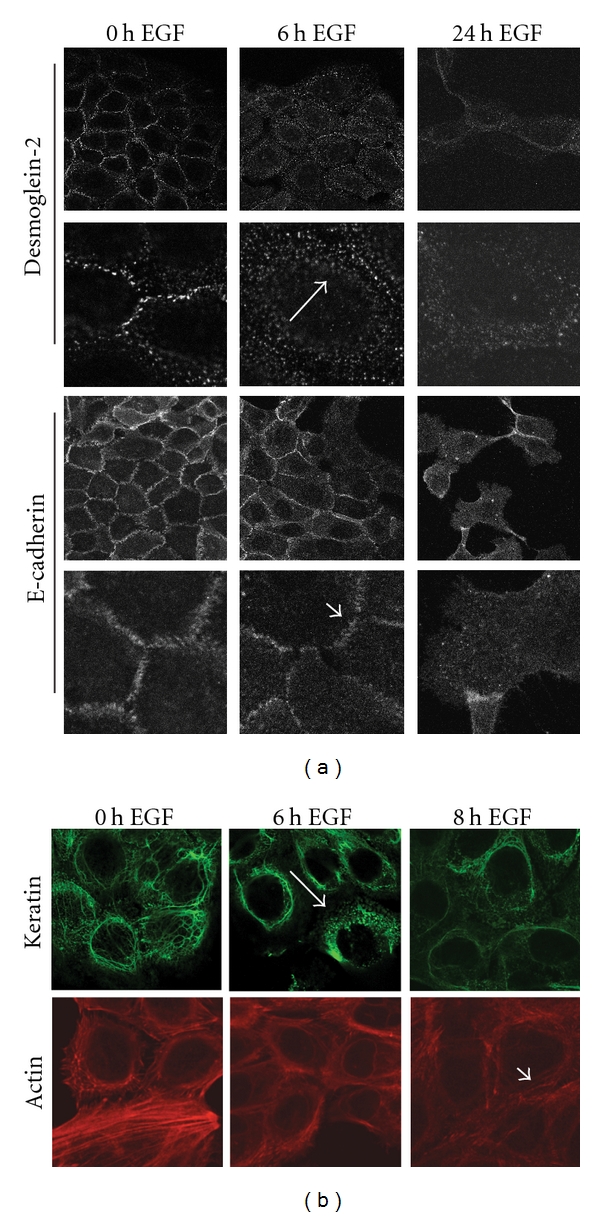

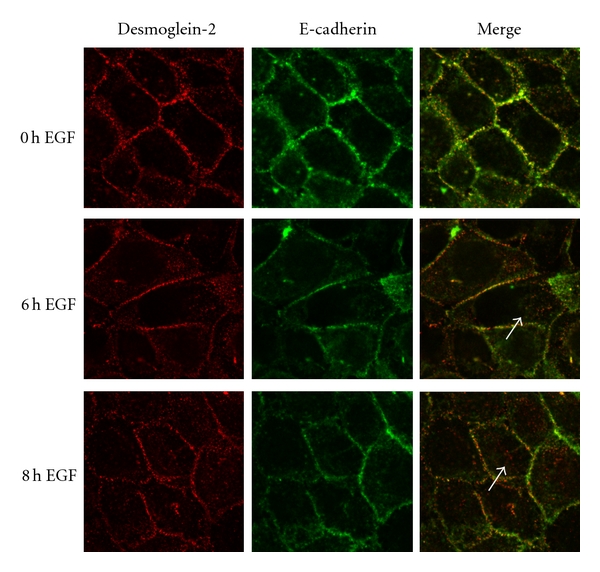

3.4. EGF-Dependent Downregulation of Desmoglein-2 Precedes E-Cadherin

The cellular localization of E-cadherin and desmoglein-2 following EGF receptor activation confirmed the differences observed in the cell fractionation studies. Internalization of desmoglein-2 was evident within 6 hours of EGF treatment as detected by punctate intracellular staining (Figure 4(a), white arrows). In contrast, E-cadherin staining was retained at the cell borders after EGF treatment (Figure 4(a), arrowheads). Loss of both cadherins from cell borders was evident after 24 hours of EGF treatment. Similar internalization kinetics were observed for the desmosomal catenin plakoglobin and the adherens junctional component, beta-catenin (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Different kinetics for disruption of desmosomes and adherens junctions by EGF. (a) SCC 12F cells were treated with EGF for the indicated times, fixed, and then probed with E-cadherin or desmoglein-2 antibodies. Note the relocalization of the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2 from the cell borders following treatment with EGF for 4–6 h (white arrows). This pattern differs from that observed for the adherens junctional cadherin, E-cadherin, where strong border staining is evident at 6 hours post EGF treatment (white arrowheads). (b) Cells were treated with EGF, fixed, and then stained with phalloidin to stain the actin cytoskeleton, or with a pan-cytokeratin antibody, to label keratin filaments. Disorganization of the keratin network is seen at 6 hours (white arrow), while the actin cytoskeleton remains intact at 8 hours posttreatment (white arrowheads).

Immunostaining of the corresponding cytoskeleton partners shows disruption of the desmosomal-associated cytokeratin network at 6 hours, consistent with the time frame of desmosomal cadherin internalization (Figure 4(b)). In contrast, the adherens junction-associated actin cytoskeleton remains intact at this timepoint and is maintained at 8 hours following EGF treatment, consistent with E-cadherin localization. Disruption of the actin skeleton was evident 24 hours posttreatment (data not shown). These findings indicate that functional disruption of desmosomes precedes that of adherens junctions.

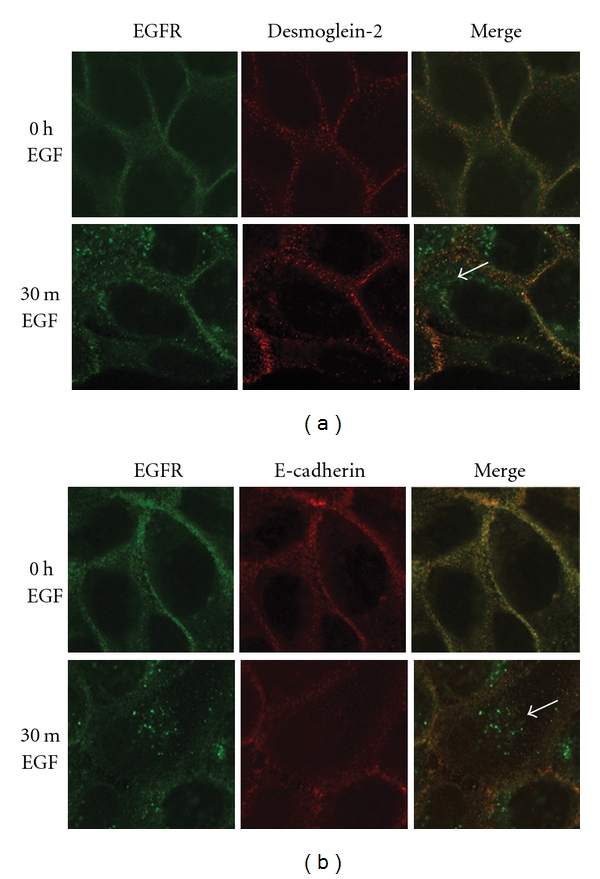

3.5. Internalization Fate of Desmoglein-2

Several studies document E-cadherin internalization in response to growth factors [19, 50–52]; however, EGF-stimulated trafficking of desmosomal cadherins has not been well described. EGF receptor activation stimulates multiple trafficking pathways including clathrin-dependent and –independent trafficking itineraries [19, 53, 54]. EGF stimulates clathrin-dependent EGF receptor internalization [55, 56], although the receptor can undergo clathrin-independent internalization under certain situations such as oxidative stress [57]. Neither E-cadherin nor desmoglein-2 colocalized with the EGF receptor following EGF receptor activation, and EGF receptor internalization preceded that of desmoglein-2 by several hours (Figure 5, white arrows). These findings indicate that although desmoglein-2 internalizes in response to EGF receptor activation, the two proteins do not follow the same itinerary. Dual immunofluorescence staining for desmoglein-2 and E-cadherin reveals that desmoglein-2 colocalizes with E-cadherin at the cell surface, but not in the cytosol post EGF treatment (Figure 6) further indicating distinct fates for the two cadherins.

Figure 5.

Cadherins do not cointernalize with the EGF receptor. SCC 12F cells were treated with 20 nM EGF for 30 minutes, fixed, and probed for EGF receptor (green) or junctional cadherin (red). White arrows indicate the internalized EGF receptor in the cytoplasm while both junctional cadherins, desmoglein-2 (upper panel), and E-cadherin (lower panel) remain at the cell surface 30 minutes post EGF treatment.

Figure 6.

Desmoglein-2 does not internalize with E-cadherin. SCC 12F cells were treated with EGF for the indicated times, fixed, then probed with E-cadherin or desmoglein-2 antibodies. The desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2 is relocalized from the cell borders at 6–8 hrs after EGF treatment. Note punctate cytoplasmic staining (white arrows). This pattern differs from that observed for the adherens junctional cadherin, E-cadherin, where strong border staining is evident at 6 hours post EGF treatment.

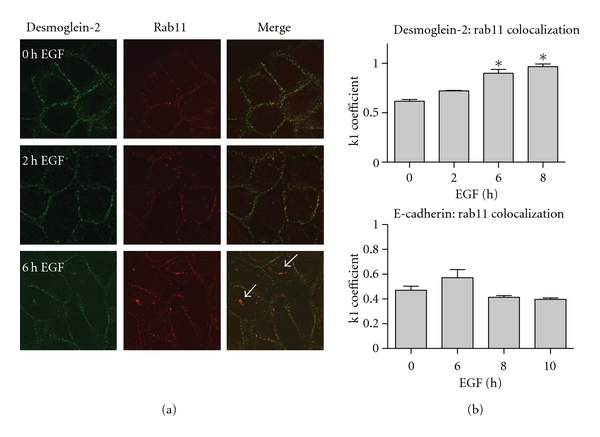

To establish whether desmoglein-2 internalization occurs through the classical endosomal pathway or through alternate internalization pathways, we used markers of the classical endosomal pathway (EEA-1, Rabs) as well as markers for caveolae-dependent internalization (caveolin-1). A small fraction of desmoglein-2 was present in EEA-1-positive early endosomes. However, there was little evidence of desmoglein-2 colocalizing with rab7, a late endocytic vesicle marker, nor with lysotracker, a marker of lysosomes, for up to 12 hours post EGF treatment (summarized in Table 1). Similarly, desmoglein-2 did not colocalize with caveolin-1, a marker for the caveosomal-dependent trafficking. The majority of desmoglein-2 colocalized with the recycling marker Rab11 (Figure 7(a)). Colocalization was analyzed using Mander's overlap coefficients k1 and k2 [58], where the k1 coefficient described the amount of cadherin colocalized with Rab11 as compared to total cadherin levels. Over an 8-hour time course, desmoglein-2 colocalization with Rab11 increased (Figure 7(b)) and at 6- and 8-hour time points, both proteins were present in small punctate vesicles on the plasma membrane and in the cytosol. This colocalization was statistically significant at the 6- and 8-hour time points (Figure 6(b), P < 0.05) whereas E-cadherin showed no increase in k1 over the same timepoints. Together, these findings indicate that EGF promotes desmoglein-2 internalization through a predominantly recycling rather than a lysosomal degradation pathway and represents a novel internalization fate for desmoglein-2.

Table 1.

Localization of cadherins with endocytic trafficking markers. Colocalization experiments were conducted using immunofluorescence techniques and confocal microscopy as described in “Methods”. EGF treatment ranged from 2–12 hours, and experiments were repeated a minimum of 3 times. (−) indicates no colocalization at any timepoint; (±) indicates colocalization at the plasma membrane but not in cytoplasm; (+) indicates vesicular colocalization in at least one timepoint; (+++) indicates colocalization in vesicles at several timepoints.

| Endosomal compartment | Desmoglein-2 colocalization | E-cadherin colocalization |

|---|---|---|

| EEA1 (Early endosome) | + | N. T. |

| Rab11 (Recycling endosome) | +++ | − |

| Rab7 (Late endosome) | − | − |

| Lysotracker (Lysosome) | + | − |

| Caveolin-1 (Caveosome) | + | (±) |

Figure 7.

Desmoglein-2 colocalizes with Rab11, a recycling marker. (a) SCC 12F cells were treated for the indicated times with 20 nM EGF, then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were stained with antibodies against both desmoglein-2 and rab11. Secondary antibodies tagged with either FITC or Rhodamine were used. Colocalization is detected by the appearance of yellow staining where the red and green overlap, particularly in EGF-treated cells (white arrows). (b) Mandler's overlap coefficient, k1, measures the ratio of cadherin colocalized with Rab11 to total cadherin present.

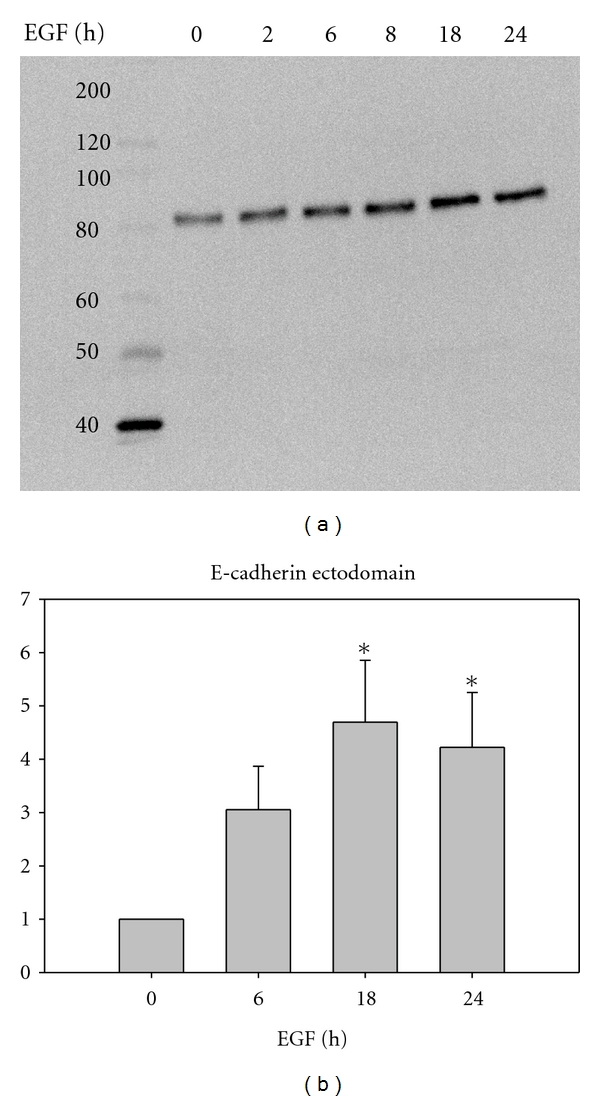

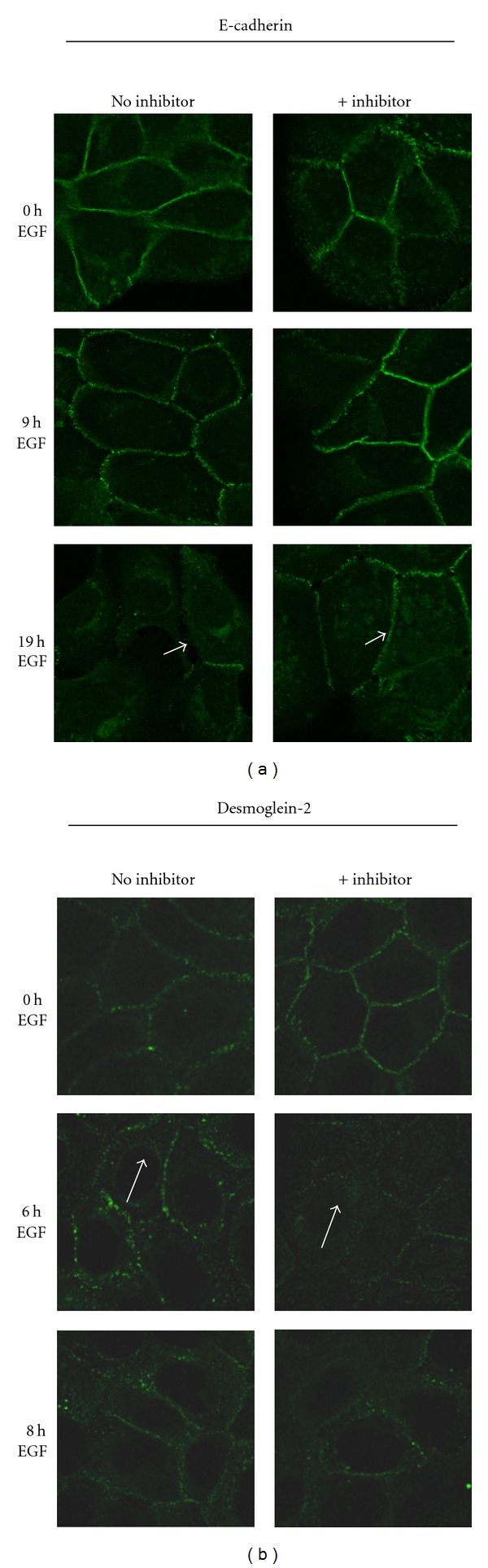

3.6. EGF Receptor Activation Stimulates E-Cadherin Cleavage

In contrast to desmoglein-2, EGF treatment led to a gradual decrease in the intensity of E-cadherin staining at cell-cell borders without an emergence of punctate intracellular staining indicative of internalization after 8-hour treatment (see Figure 6). However, at these same timepoints, E-cadherin cleavage as a consequence of EGF receptor activation was detected by immunoblotting for the 80 kD E-cadherin ectodomain. A significant increase in an 80 kD E-cadherin fragment in the conditioned medium was evident 18 hours and 24 hours after EGF treatment (Figure 8). There was no evidence for desmoglein-2 cleavage products under the same conditions (data not shown). Accumulation of the EGF-dependent 80 kD E-cadherin fragment was prevented by pretreatment with a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor GM6001X. Although there is some internalized E-cadherin after 18 hours of EGF treatment, cells pretreated with the MMP inhibitor retain significant junctional E-cadherin staining at the plasma membrane (Figure 9). Conversely, this protection was not extended to the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2, as internalization was independent of the MMP inhibitor. Taken together, these studies indicate distinct fates for the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2 as compared to the classical cadherin E-cadherin upon EGF stimulation.

Figure 8.

EGF receptor activation leads to accumulation of an E-cadherin extracellular fragment in conditioned medium. Subconfluent cells were serum-starved (without BSA in the medium) for 24 hours. Cells were treated with 20 nM EGF for the indicated times, then the conditioned medium was collected, concentrated, and resolved on an 8% SDS gel. Samples of conditioned media were normalized to the corresponding protein lysate, transferred onto PVDF, and probed with an antibody against the extracellular epitope of E-cadherin, which recognizes both full length (120 kD) and cleaved E-cadherin (80 kD).

Figure 9.

Effect of MMP inhibition on membrane localization of E-cadherin or desmoglein-2 after EGF treatment. Cells were serum-starved for 24 hours then treated with 50 μM of the broad spectrum MMP inhibitor GM6001X for 30 minutes before addition of 20 nM EGF for the indicated times. Cells were then fixed and probed with either an E-cadherin antibody that recognizes the intracellular epitope or desmoglein-2 antibody. White arrows indicate the internalized desmoglein-2 even in the presence of inhibitor, while the white arrowheads indicate the retention of E-cadherin at the cell-cell borders.

4. Discussion

The EGF receptor is a significant regulator of cutaneous wound repair based on experimental studies, genetic models, and evidence for accelerated healing in patients [28–30]. In this study we demonstrate temporal differences in EGF-dependent down-regulation of E-cadherin and desmoglein-2. Our studies demonstrate a decrease of desmosomal function precedes that of adherens junctions in vivo and for the EGF-stimulated responses in vitro. This finding is consistent with previous reports that assembly of adherens junctions is necessary for the formation of desmosomes [59]. The potential significance of desmosomal disruption preceding that of adherens junctions may be related to the requirement of keratinocytes to form a migratory epithelial sheet from the stratified epidermis [1]. It has been noted that conversion to a single cell layer requires down-regulation of desmosomal adhesion [60]. Importantly, we provide evidence that the EGF-stimulated disruption of the two types of junctions is related to different underlying mechanisms for the down-regulation of cadherin function.

EGF receptor activation led to accumulation of an 80 kD E-cadherin fragment in conditioned medium, and a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor protected adherens junctions from EGF-dependent disruption. Extracellular cleavage of E-cadherin is a well-studied mechanism, and several proteases, including MMP-3, -7 [18], -9 [16], MT1-MMP, ADAM10 [61] and ADAM15 [62], as well as plasmin [17], kallikrein 7 [63], and γ-secretase [64, 65] cleave E-cadherin. EGF is a known inducer of MMPs and other proteases, and there is evidence for EGF-stimulating MMP-dependent E-cadherin cleavage [16, 35, 66–71]. Although the internalization of E-cadherin has been reported in several models and occurs through clathrin-dependent [24, 25, 50, 72–74], clathrin-independent [75, 76], and caveolae-dependent [54] pathways, the endocytic fate of E-cadherin appears to vary according to the stimulus presented and cell context [54, 77, 78]. Src activation promotes clathrin-dependent endocytosis of E-cadherin [25], yet clathrin-independent mechanisms were reported following EGF stimulation of the MCF-7 and A431 cell lines by micropinocytosis [19] and caveolar-dependent internalization [54], respectively. In contrast to studies demonstrating cointernalization of E-cadherin with the tyrosine kinase receptors c-Met and FGFR1 [50, 51], we did not find evidence for concurrent trafficking of EGF receptor with either E-cadherin or desmoglein-2.

Similar to E-cadherin, extracellular cleavage of desmosomal cadherins has been reported. The appearance of a 60 kD fragment of desmoglein-3 occurs in vitro in keratinocytes treated with patient sera with pemphigus vulgaris [15]. In a highly invasive squamous cell line that forms sparse cell : cell junctions, a 100 kD desmoglein-2 fragment was detected in low-calcium (.09 mM) conditions, and production of this fragment was reversed by inhibition of the EGF receptor and the inhibition of several members of the sheddase family of ADAMS (a disintegrin and metalloprotease), including ADAM17 [79]. ADAM 17 has been shown by others to be increased in response to EGF [80] and to cleave desmoglein-2 [81]. Our studies suggest that EGF receptor-stimulated desmoglein-2 cleavage is not the predominant mechanism in this experimental system.

There is additional evidence that desmosomal cadherins can be internalized in response to various stimuli. In HaCat cells, desmoglein-1 underwent internalization in response to sera collected from pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus patients as early as 6 hours with a concurrent decrease in the amount of desmoglein-1 found in the membrane-associated fraction postexposure [21]. Internalization of desmoglein-3 in response to pemphigus autoantibody was found to undergo clathrin-independent internalization [22], early endosomal localization [23], and subsequent lysosomal degradation [20]. Both EGF receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms have been proposed [82–84].

The potential significance of reversible mechanisms for downregulation of cadherins may be related to characteristics of the partial EMT present at wound margins [1]. There has been increased appreciation that partial EMT includes processes of dynamic junctional modulation and retention of cell cohesion rather than complete cell dissociation and migration of individual cells. As examples, both in culture and in vivo, maintenance of cell : cell contact of migrating neural crest cells is necessary for movement persistence and oriented migration [85]. In the Drosophila tracheal system, dynamic modulation of junctions through endocytosis and recycling maintains tissue stability during migratory processes [86], and during gastrulation, posttranslational regulatory mechanisms such as E-cadherin protein degradation and turnover appear to be important [85]. One characteristic of cohesive migrating epithelial is that cells at the edge of these tissues appear more mesenchymal [87] as we observe at the edge of wound margins in vitro and in vivo (Figures 1 and 2).

Collectively, the data indicates that there are numerous trafficking itineraries and mechanisms of cadherin down-regulation that may be dependent upon the initial signaling event. Our studies demonstrate EGF-stimulated down-regulation of E-cadherin and desmoglein-2 through distinct mechanisms; EGF-dependent cleavage of E-cadherin and entry of desmoglein-2 into a recycling trafficking itinerary. These distinct mechanisms may help account for the observed differences in the modulation of adherens junctions and desmosomes during wound repair in vivo.

5. Conclusions

Modulation of adherens junctions and desmosomes is an essential component of reepithelialization, yet we do not have a full understanding of the mechanisms that govern assembly and disassembly of these structures and, in particular, the fate of the respective cadherins. In this study we demonstrate that EGF downregulates E-cadherin and desmoglein-2, but with different kinetics and through distinct mechanisms. Activation of the EGF receptor leads to E-cadherin cleavage through an MMP-dependent mechanism. In contrast, a desmosomal cadherin, desmoglein-2, is internalized and localizes predominantly within a recycling compartment rather than trafficking to lysosomes, thereby representing a novel fate in response to growth factor activation. This study illustrates that the same stimulus can lead to divergent outcomes for disruption of adherens junctions and desmosomal complexes, and different fates for the corresponding cadherins. Understanding how various stimuli direct cadherin trafficking and downregulation will likely prove important to understanding junctional modulation in physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions.

Acknowledgments

Images in this paper were generated in the University of New Mexico & Cancer Center Fluorescence Microscopy Shared Resource, funded as detailed on: http://hsc.unm.edu/crtc/microscopy/. This work was supported by: NIH R01 GM079381, NIH R01AR042989, and a minority supplement to NIH RO1AR42989.

Abbreviations

- EGF:

epidermal growth factor,

- MMP:

matrix metalloproteinase,

- EMT:

epithelial-mesenchymal transition,

- PCR:

polymerase chain reaction,

- SCC:

squamous cell carcinoma,

- BSA:

bovine serum albumin,

- PBS:

phosphate buffered saline,

- SDS:

sodium dodecyl sulfate,

- TBST:

Tris buffered saline with Tween,

- EDTA:

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid,

- EGTA:

Ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid,

- PMSF:

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride.

References

- 1.Arnoux V, Come C, Kusewitt D, Hudson L, Savagner P. Cutaneous wound reepithelializaton: a partial and reversible EMT. In: Savagner P, editor. Rise and Fall of Epithelial Phenotype: Concepts of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005. pp. 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RYJ, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura M, Tokura Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the skin. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2011;61(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(6):1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuwahara M, Hatoko M, Tada H, Tanaka A. E-cadherin expression in wound healing of mouse skin. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology. 2001;28(4):191–199. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028004191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danjo Y, Gipson IK. Actin “purse string” filaments are anchored by E-cadherin-mediated adherens junctions at the leading edge of the epithelial wound, providing coordinated cell movement. Journal of Cell Science. 1998;111, part 22:3323–3332. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.22.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawczyk WS, Wilgram GF. Hemidesmosome and desmosome morphogenesis during epidermal wound healing. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1973;45(1-2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(73)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sciubba JJ, Waterhouse JP, Meyer J. A fine structural comparison of the healing of incisional wounds of mucosa and skin. Journal of Oral Pathology. 1978;7(4):214–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1978.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariner DJ, Davis MA, Reynolds AB. EGFR signaling to p120-catenin through phosphorylation at Y228. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117(8):1339–1350. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorch JH, Klessner J, Park JK, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition promotes desmosome assembly and strengthens intercellular adhesion in squamous cell carcinoma cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(35):37191–37200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MV, Burnett PE, Denning MF, Reynolds AB. PDGF receptor activation induces p120-catenin phosphorylation at serine 879 via a PKCα-dependent pathway. Experimental Cell Research. 2009;315(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaudry CA, Palka HL, Dusek RL, et al. Tyrosine-phosphorylated plakoglobin is associated with desmogleins but not desmoplakin after epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(27):24871–24880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang R, Shi Z, Johnson JJ, Liu Y, Stack MS. Kallikrein-5 promotes cleavage of desmoglein-1 and loss of cell-cell cohesion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(11):9127–9135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson CL, Kojima SI, Cooper-Whitehair V, Getsios S, Green KJ. Plakoglobin rescues adhesive defects induced by ectodomain truncation of the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein 1: implications for exfoliative toxin-mediated skin blistering. American Journal of Pathology. 2010;177(6):2921–2937. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cirillo N, Campisi G, Gombos F, Perillo L, Femiano F, Lanza A. Cleavage of desmoglein 3 can explain its depletion from keratinocytes in pemphigus vulgaris. Experimental Dermatology. 2008;17(10):858–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl KDC, Symowicz J, Ning Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 is a mediator of epidermal growth factor-dependent E-cadherin loss in ovarian carcinoma cells. Cancer Research. 2008;68(12):4606–4613. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryniers F, Stove C, Goethals M, et al. Plasmin produces an E-cadherin fragment that stimulates cancer cell invasion. Biological Chemistry. 2002;383(1):159–165. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noë V, Fingleton B, Jacobs K, et al. Release of an invasion promoter E-cadherin fragment by matrilysin and stromelysin-1. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114, part 1:111–118. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant DM, Kerr MC, Hammond LA, et al. EGF induces macropinocytosis and SNX1-modulated recycling of E-cadherin. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120, part 10:1818–1828. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calkins CC, Setzer SV, Jennings JM, et al. Desmoglein endocytosis and desmosome disassembly are coordinated responses to pemphigus autoantibodies. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(11):7623–7634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cirillo N, Gombos F, Lanza A. Changes in desmoglein 1 expression and subcellular localization in cultured keratinocytes subjected to anti-desmoglein 1 pemphigus autoimmunity. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;210(2):411–416. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delva E, Jennings JM, Calkins CC, Kottke MD, Faundez V, Kowalczyk AP. Pemphigus vulgaris IgG-induced desmoglein-3 endocytosis and desmosomal disassembly are mediated by a clathrin- and dynamin-independent mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(26):18303–18313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710046200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennings JM, Tucker DK, Kottke MD, et al. Desmosome disassembly in response to pemphigus vulgaris IgG occurs in distinct phases and can be reversed by expression of exogenous Dsg3. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2011;131(3):706–718. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyashita Y, Ozawa M. Increased internalization of p120-uncoupled E-cadherin and a requirement for a dileucine motif in the cytoplasmic domain for endocytosis of the protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(15):11540–11548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palacios F, Tushir JS, Fujita Y, D’Souza-Schorey C. Lysosomal targeting of E-cadherin: a unique mechanism for the down-regulation of cell-cell adhesion during epithelial to mesenchymal transitions. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25(1):389–402. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.389-402.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao K, Garner J, Buckley KM, et al. p120-Catenin regulates clathrin-dependent endocytosis of VE-cadherin. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16(11):5141–5151. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallis S, Lloyd S, Wise I, Ireland G, Fleming TP, Garrod D. The α isoform of protein kinase C is involved in signaling the response of desmosomes to wounding in cultured epithelial cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(3):1077–1092. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoscheck CM, Nanney LB, King LE., Jr. Quantitative determining of EGF-R during epidermal wound healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1992;99(5):645–649. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12668143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenczak BA, Lynch JB, Nanney LB. Epidermal growth factor receptor distribution in burn wounds. Implications for growth factor-mediated repair. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;90(6):2392–2401. doi: 10.1172/JCI116130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Repertinger SK, Campagnaro E, Fuhrman J, El-Abaseri T, Yuspa SH, Hansen LA. EGFR enhances early healing after cutaneous incisional wounding. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2004;123(5):982–989. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2008;16(5):585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardwicke J, Schmaljohann D, Boyce D, Thomas D. Epidermal growth factor therapy and wound healing—past, present and future perspectives. Surgeon. 2008;6(3):172–177. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(08)80114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirley SH, Hudson LG, He J, Kusewitt DF. The skinny on slug. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2010;49(10):851–861. doi: 10.1002/mc.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusewitt DF, Choi C, Newkirk KM, et al. Slug/Snai2 is a downstream mediator of epidermal growth factor receptor-stimulated reepithelialization. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129(2):491–495. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCawley LJ, Li S, Wattenberg EV, Hudson LG. Sustained activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway: a mechanism underlying receptor tyrosine kinase specificity for matrix metalloproteinase-9 induction and cell migration. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(7):4347–4353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCawley LJ, O’Brien P, Hudson LG. Overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor contributes to enhanced ligand-mediated motility in keratinocyte cell lines. Endocrinology. 1997;138(1):121–127. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudson LG, Newkirk KM, Chandler HL, et al. Cutaneous wound reepithelialization is compromised in mice lacking functional Slug (Snai2) Journal of Dermatological Science. 2009;56(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark RAF. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York, NY, USA: Plenum Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moll I, Houdek P, Schäfer S, Nuber U, Moll R. Diversity of desmosomal proteins in regenerating epidermis: immunohistochemical study using a human skin organ culture model. Archives of Dermatological Research. 1999;291(7-8):437–446. doi: 10.1007/s004030050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanney LB, Paulsen S, Davidson MK, Cardwell NL, Whitsitt JS, Davidson JM. Boosting epidermal growth factor receptor expression by gene gun transfection stimulates epidermal growth in vivo. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2000;8(2):117–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hudson LG, McCawley LJ. Contributions of the epidermal growth factor receptor to keratinocyte motility. Microscopy Research and Technique. 1998;43(5):444–455. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981201)43:5<444::AID-JEMT10>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhora FY, Dunkin BJ, Batzri S, et al. Effect of growth factors on cell proliferation and epithelialization in human skin. Journal of Surgical Research. 1995;59(2):236–244. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1995.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudson LG, Toscano WA, Jr., Greenlee WF. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) modulates epidermal growth factor (EGF) binding to basal cells from a human keratinocyte cell line1. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1986;82(3):481–492. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(86)90283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pittelkow MR, Cook PW, Shipley GD, Derynck R, Coffey RJ. Autonomous growth of human keratinocytes requires epidermal growth factor receptor occupancy. Cell Growth & Differentiation. 1993;4(6):513–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shibamoto S, Hayakawa M, Takeuchi K, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin and plakoglobin enhanced by hepatocyte growth factor and epidermal growth factor in human carcinoma cells. Cell Adhesion and Communication. 1994;1(4):295–305. doi: 10.3109/15419069409097261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hazan RB, Norton L. The epidermal growth factor receptor modulates the interaction of E- cadherin with the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(15):9078–9084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moon HS, Choi EA, Park HY, et al. Expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of E-cadherin, β- and γ-catenin, and epidermal growth factor receptor in cervical cancer cells. Gynecologic Oncology. 2001;81(3):355–359. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolós V, Peinado H, Pérez-Moreno MA, Fraga MF, Esteller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116, part 3:499–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guaita S, Puig I, Francí C, et al. Snail induction of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in tumor cells is accompanied by MUC1 repression and ZEB1 expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(42):39209–39216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryant DM, Wylie FG, Stow JL. Regulation of endocytosis, nuclear translocation, and signaling of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 by E-cadherin. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16(1):14–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamei T, Matozaki T, Sakisaka T, et al. Coendocytosis of cadherin and c-Met coupled to disruption of cell-cell adhesion in MDCK cells—regulation by Rho, Rac and Rab small G proteins. Oncogene. 1999;18(48):6776–6784. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palacios F, Schweitzer JK, Boshans RL, D’Souza-Schorey C. ARF6-GTP recruits Nm23-H1 to facilitate dynamin-mediated endocytosis during adherens junctions disassembly. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4(12):929–936. doi: 10.1038/ncb881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ning Y, Buranda T, Hudson LG. Activated epidermal growth factor receptor induces integrin α2 internalization via caveolae/raft-dependent endocytic pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(9):6380–6387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Z, Ghosh S, Wang Z, Hunter T. Downregulation of caveolin-1 function by EGF leads to the loss of E-cadherin, increased transcriptional activity of β-catenin, and enhanced tumor cell invasion. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(6):499–515. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang F, Khvorova A, Marshall W, Sorkin A. Analysis of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor receptor by RNA interference. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(16):16657–16661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sigismund S, Argenzio E, Tosoni D, Cavallaro E, Polo S, di Fiore PP. Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Developmental Cell. 2008;15(2):209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan EM, Heidinger JM, Levy M, Lisanti MP, Ravid T, Goldkorn T. Epidermal growth factor receptor exposed to oxidative stress undergoes Src- and caveolin-1-dependent perinuclear trafficking. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(20):14486–14493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manders EMM, Verbeek FJ, Aten JA. Measurement of co-localization of objects in dual-colour confocal images. Journal of Microscopy. 1993;169(3):375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1993.tb03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis JE, Wahl JK, Sass KM, Jensen PJ, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. Cross-talk between adherens junctions and desmosomes depends on plakoglobin. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;136(4):919–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garrod D, Chidgey M. Desmosome structure, composition and function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1778(3):572–587. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maretzky T, Reiss K, Ludwig A, et al. ADAM10 mediates E-cadherin shedding and regulates epithelial cell-cell adhesion, migration, and β-catenin translocation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(26):9182–9187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Najy AJ, Day KC, Day ML. The ectodomain shedding of E-cadherin by ADAM15 supports ErbB receptor activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(26):18393–18401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801329200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson SK, Ramani VC, Hennings L, Haun RS. Kallikrein 7 enhances pancreatic cancer cell invasion by shedding E-cadherin. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1811–1820. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marambaud P, Shioi J, Serban G, et al. A presenilin-1/γ-secretase cleavage releases the E-cadherin intracellular domain and regulates disassembly of adherens junctions. EMBO Journal. 2002;21(8):1948–1956. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferber EC, Kajita M, Wadlow A, et al. A role for the cleaved cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin in the nucleus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(19):12691–12700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708887200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilkins-Port CE, Ye Q, Mazurkiewicz JE, Higgins PJ. TGF-β1 + EGF-initiated invasive potential in transformed human keratinocytes is coupled to a plasmin/mmp-10/mmp-1-dependent collagen remodeling axis: role for PAI-1. Cancer Research. 2009;69(9):4081–4091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dahl KDC, Zeineldin R, Hudson LG. PEA3 is necessary for optimal epidermal growth factor receptor-stimulated matrix metalloproteinase expression and invasion of ovarian tumor cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2007;5(5):413–421. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris VL, Chan BMC. Interaction of epidermal growth factor, Ca2+, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in primary keratinocyte migration. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2007;15(6):907–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Charvat S, Chignol MC, Souchier C, le Griel C, Schmitt D, Serres M. Cell migration and MMP-9 secretion are increased by epidermal growth factor in HaCaT-ras transfected cells. Experimental Dermatology. 1998;7(4):184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park S, Jung HH, Park YH, Ahn JS, Im YH. ERK/MAPK pathways play critical roles in EGFR ligands-induced MMP1 expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2011;407(4):680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hudson LG, Moss NM, Stack MS. EGF-receptor regulation of matrix metalloproteinases in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Future Oncology. 2009;5(3):323–338. doi: 10.2217/FON.09.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Izumi G, Sakisaka T, Baba T, Tanaka S, Morimoto K, Takai Y. Endocytosis of E-cadherin regulated by Rac and Cdc42 small G proteins through IQGAP1 and actin filaments. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;166(2):237–248. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ivanov AI, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. Endocytosis of epithelial apical junctional proteins by a clathrin-mediated pathway into a unique storage compartment. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15(1):176–188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Le TL, Yap AS, Stow JL. Recycling of E-cadherin: a potential mechanism for regulating cadherin dynamics. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;146(1):219–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paterson AD, Parton RG, Ferguson C, Stow JL, Yap AS. Characterization of E-cadherin endocytosis in isolated MCF-7 and Chinese hamster ovary cells. The initial fate of unbound E-cadherin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(23):21050–21057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akhtar N, Hotchin NA. Rac1 regulates adherens junctions through endocytosis of E-cadherin. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2001;12(4):847–862. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bryant DM, Stow JL. The ins and outs of E-cadherin trafficking. Trends in Cell Biology. 2004;14(8):427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D’Souza-Schorey C. Disassembling adherens junctions: breaking up is hard to do. Trends in Cell Biology. 2005;15(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klessner JL, Desai BV, Amargo EV, Getsios S, Green KJ. EGFR and ADAMs cooperate to regulate shedding and endocytic trafficking of the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein 2. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20(1):328–337. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Santiago-Josefat B, Esselens C, Bech-Serra JJ, Arribas J. Post-transcriptional up-regulation of ADAM17 upon epidermal growth factor receptor activation and in breast tumors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(11):8325–8331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bech-Serra JJ, Santiago-Josefat B, Esselens C, et al. Proteomic identification of desmoglein 2 and activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule as substrates of ADAM17 and ADAM10 by difference gel electrophoresis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(13):5086–5095. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02380-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heupel WM, Engerer P, Schmidt E, Waschke J. Pemphigus vulgaris IgG cause loss of desmoglein-mediated adhesion and keratinocyte dissociation independent of epidermal growth factor receptor. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;174(2):475–485. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chernyavsky AI, Arredondo J, Kitajima Y, Sato-Nagai M, Grando SA. Desmoglein versus non-desmoglein signaling in pemphigus acantholysis: characterization of novel signaling pathways downstream of pemphigus vulgaris antigens. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(18):13804–13812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Frušić-Zlotkin M, Raichenberg D, Wang X, David M, Michel B, Milner Y. Apoptotic mechanism in pemphigus autoimmunoglobulins-induced acantholysis—possible involvement of the EGF receptor. Autoimmunity. 2006;39(7):563–575. doi: 10.1080/08916930600971836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Acloque H, Adams MS, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(6):1438–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI38019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shaye DD, Casanova J, Llimargas M. Modulation of intracellular trafficking regulates cell intercalation in the Drosophila trachea. Nature Cell Biology. 2008;10(8):964–970. doi: 10.1038/ncb1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Revenu C, Gilmour D. EMT 2.0: shaping epithelia through collective migration. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2009;19(4):338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]