Abstract

Major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) molecules are expressed on the surface of antigen presenting cells and display short bound peptide fragments derived from self and nonself antigens. These peptide-MHC complexes function to maintain immunological tolerance in the case of self antigens and initiate the CD4+ T cell response in the case of foreign proteins. Here we report the application of LC-MS/MS analysis to identify MHC II peptides derived from endogenous proteins expressed in freshly isolated murine splenic DCs. The cell number was enriched in vivo upon treatment with Flt3L-B16 melanoma cells. In a typical experiment, starting with about 5× 108 splenic DCs, we were able to reliably identify a repertoire of over 100 MHC II peptides originating from about 55 proteins localized in membrane (23%), intracellular (26%), endo-lysosomal (12%), nuclear (14%) and extracellular (25%) compartments. Using synthetic isotopically labeled peptides corresponding to the sequences of representative bound MHC II peptides, we quantified by LC-MS relative peptide abundance. In a single experiment, peptides were detected in a wide concentration range spanning from 2.5 fmol/μL to 12 pmol/μL or from approximately 13 copies to 2×105 copies per DC. These peptides were found in similar amounts on B cells where we detected about 80 peptides originating from 55 proteins distributed homogenously within the same cellular compartments as in DCs. About 90 different binding motifs predicted by the epitope prediction algorithm were found within the sequences of the identified MHC II peptides. These results set a foundation for future studies to quantitatively investigate the MHC II repertoire on DCs generated under different immunization conditions.

Keywords: Endogenous peptides, MHC, DCs, Flt3L, LC-MS/MS, AQUA analysis, isotopically labeled peptides

Introduction

Identification of vaccines and immune therapies should benefit from knowledge of antigenic peptide sequences originating from proteins that are presented on MHC I and MHC II molecules on antigen presenting cells. The most specialized antigen presenting cells are dendritic cells (DCs) 1–3. They display self antigens for the induction of tolerance 4, 5 and they capture foreign antigens by phagocytosis, pinocytosis and receptor mediated uptake to initiate T cell immunity 6, 7. However, there are no direct studies of the spectrum of MHC II peptides that are presented by DCs 8, 9.

B cells like DCs display self peptides and they are specialized to capture antigens via the B cell receptor 10. Following antigen processing and presentation to T cells, particularly in germinal centers, the B cells expand, undergo isotype switching and develop high affinity and specific antibodies 11, 12. Peptides presented by MHC II molecules on B cells have been characterized by several groups by LC-MS/MS analysis using between 109 and 1010 cells from established cell lines 13–17.

Numerous studies have established that MHC II molecules present peptides generated from endogenous cellular proteins by proteolytic degradation 13, 14, 17. They vary in length from 8–30 amino acids and are usually found as nested sets of peptides with a core sequence shared among them 18–21. In the past, limited numbers of DCs isolated from normal mouse spleen have restricted their use for proteomic analysis. The number of DCs in various tissues of mice can be expanded in vivo by treatment with Flt3L22–24, which is a regulator of hematopoietic cell development25. The receptor, Flt-3 or Flt-2 or CD135, is a marker for committed progenitors of DCs that form in the bone marrow and then continue to respond to Flt3L after migration via the blood into spleen and lymph nodes 25–30. It has been demonstrated that these Flt3L mobilized DCs resemble their counterparts in untreated mice 31.

We postulated that these Flt3L DCs can be used to identify the repertoire of peptides bound to MHC II molecules on DCs by mass spectrometry. Here we will show that this is indeed feasible. We find that MHC II bound peptides are presented on DCs over a wide range of copies per cell and their abundance is similar in DCs and B cells. In both DCs and B cells they originate from proteins localized quite uniformly among different intracellular compartments. There was a good agreement between the MHC II peptide sequences identified by LC-MS/MS and sequences predicated from the epitope binding algorithm.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Balb/c x C57Bl/6 (C x B6) F1 mice from Harlan Animal Research Laboratory (3565 Paysphere Circle, Chicago, IL 60674 USA) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and used at 6–8 wk of age in accordance with Rockefeller University Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Cell lines, Antibodies, Reagents

Melanoma cells expressing Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) were established via retroviral gene transfer 32 and generously provided by L. Santambrogio (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY). B16 Flt3L melanoma cells were cultured with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 5 × 106 were injected s.c into the abdomen region of mice. After 15–20 days, all major splenic DC subsets had expanded >10 fold in agreement with previous reports 22, 33. The anti-MHC class II (N22) hydridoma cells 22, 33 were maintained in DMEM medium with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The N22 monoclonal antibody was affinity-purified from culture supernatants using Protein G Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences). Poly IC (polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid) was from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell enrichment

Flt3L treated mice were injected in vivo with poly IC (50 μg) for 5 hr prior to harvesting their spleens. Spleens were removed, cut in small fragments, and digested into single cell-suspensions with 400 U/ml collagenase D (Roche Applied Science) for 25 min at 37°C. After inhibition of collagenase with 10 mM EDTA, cells were resuspended in PBS in 2 mM EDTA and 2% FCS. CD11c+ DC were enriched by positive selection using anti-CD11c magnetic beads and MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). From a pool of 12–17 mice we could typically obtain from 5×108 to 7×108 DCs. DCs were obtained from seven separate experiments. In four out of the seven experiments CD19+ B cells were simultaneously obtained from the same pool of mouse spleens as DCs by positive selection using CD19-biotin antibody (D3 clone, BD Biosciences) followed by streptavidin magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The yield of B cells was typically 6–8 ×108 cells.

Affinity purification of MHC II molecules

MHC II molecules were purified by immunoaffinity from the cells after lysis with 1% CHAPS (Anatrace), 0.1 mM iodoacetamide, 5 mM EDTA, 1:100 Protease Inhibitors Cocktail, 1 mM PMSF (Sigma) in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 at 4 °C for 45 min on a rotator. The lysate was cleared by 30 min centrifugation at 15000 RPM. MHC class II molecules from cleared lysate were immunoaffinity purified with 12–15 mg of purified antibody N22 bound to CNBr-activated Sepharose (GE Healthcare) at a ratio of 40 mg sepharose per mg of antibody following manufacturer’ s protocol. The affinity column was washed first with 3 column volumes of lysis buffer, followed by 6 column volumes of 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 8, 6 column volumes of 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8. The MHC II molecules were eluted at room temperature for 4 min on rotator by adding 1 ml of 10% acetic acid. Small aliquots (5 ml) of each elution fraction were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and by Western blotting developed with an anti-mouse class II monoclonal antibody as culture supernatant from KL295 hybridoma 34 and a secondary anti-mouse IgG 1 -HRP conjugated antibody (SouthernBiotech) to evaluate the yield and purity of the eluted HLA (data not shown).

Purification of peptides bound to the MHC II molecules

MHC II peptide complexes were boiled at 70°C for 10 min. MHC II peptides were separated from the denatured protein subunits of the HLA molecules and the contaminating antibody by ultrafiltration through a 10 kD cutoff membrane filter (Sartorius Stedim, Aubagne, France) and centrifugation at 3000 g. The filters were washed three times with 2 ml water to remove contaminants interfering with the mass spectrometry. Recovered peptide mixtures (5–6 ml) were concentrated and desalted with C-18 cartridge (Waters, Medford, MA). The C-18 cartridge was first washed three times with 50% acetonitrile (1.5 ml), equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) in water, and then loaded with the peptide mixture. The cartridge was then washed by an additional 3 ml 0.1 TFA%, and the peptides were eluted with 0.1% TFA in 50% acetonitrile in (1.5 ml). The eluted MHC peptides were reduced to near dryness and then reconstituted at 20 μL 0.1% TFA/water. Half of the peptide mixture, corresponding to approximately 3.5–4 ×108 cell equivalents, was injected for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Analysis by mass spectrometry

For LC-MS/MS analysis, the MHC peptide mixture was separated on the Dionex U3000 capillary/nano-HPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, California) that is directly interfaced with the Thermo-Fisher LTQ-Obritrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, California). Prior to the analysis by tandem LC-MS/MS, the complex mixture was passed through a 10 kD filter to separate the peptides bound to the MHC II complex from other higher molecular weight peptides and proteins that might be present in the mixture eluted from the Ab column. The analytical column was a home-made fused silica capillary column (75 μm ID, 100 mm length; Upchurch, Oak Harbor, Washington) packed with C-18 resin (300 A, 5 mm, Varian, Palo Alto, California). To optimize the separation of peptides bound to the MHC II complex, the mixture was run on capillary/nano HPLC system with a shallow gradient of an aqueous mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and organic mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in 100% acetonitrile) in 180 min with a flow rate of 250 nL/min under the following conditions: 0 % B to 55% B formed in 120 min, followed by 25 min gradient from 55% to 80% solvent B. Solvent B was maintained at 80% for another 10 min and then decreased to 0% in 10 min. Another 15 min interval was used for equilibration, loading and washing. The HPLC system was interfaced with the Thermo-Fisher LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. The LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent acquisition mode using the Xcalibur 2.0.7 software. The experiment consisted of a single MS full-scan in the Orbitrap (620–1200 m/z, 30,000 resolution) followed by 6 data-dependent MS/MS scans in the ion trap at 35% normalized collision energy. The most intense 6 masses from each full mass spectrum with doubly and triply charge states were selected for fragmentation by collision-induced dissociation in the linear ion-trap. The dynamic exclusion parameters were as follows: Repeat count = 1; Repeat Duration = 30 second; Exclusion list = 100; and Exclusion time = 90 second.

Database search

The MS/MS spectra from each LC-MS/MS run were converted from the .RAW file format to .DTA files using the Bioworks 3.3.1 software. DTA files were analyzed using the MASCOT software search algorithm against IPI mouse database. The following search parameters were used in all MASCOT searches: the digestion enzyme was set as none and methionine oxidation as the variable modification. The maximum error tolerance for MS scans was 10 ppm for MS and 1.0 Da for MS/MS respectively. Peptide were identified by comparing the found sequences with the sequences deposited in the International Protein Index mouse (IPI) database. Only peptides with Mascot Score more than 20 and mass deviation less than 5 ppm were considered. Decoy database searches using the MASCOT software yielded an estimated FDR of less than 10 using the above mentioned settings. Therefore, only peptides that could be confirmed by other search engines, SEQUEST (ThermoFinningan) and X!tandem (www.thegpm.org), were accepted. For peptides with Mascot scores 20–30 their MS/MS spectra were inspected manually to confirm that the major fragmented ions matched the identified peptide sequences. The unambiguous confirmation of the sequences of a subset of identified peptides was obtained by comparing the MS/MS spectra of eluted natural peptides with the MS/MS spectra obtained from the corresponding synthetic isotopically labeled counterparts (Table 1, Fig. 2A–D).

Table 1.

List of isotopically labeled peptides synthesized for Absolute Quantitation Analysis.

| Protein name | Isotopically enriched peptide sequence | Mass shift (Da) |

|---|---|---|

| H-2 class II histocompatibility Ag, alpha chain | ASFEAQGAL*ANIAVDKA | 1675.86a + 7b |

| ApoE, Apolipoprotein E | KELEEQL*GPVAEETR | 1727.88a + 7b |

| Cap1, Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | GPKPFSAP*KPQTSPSP | 1622.85a + 6b |

| CtsZ, Cathepsin Z | DLPVWEYA*HKHG | 1451.70 a + 4b |

| Laptm4b, Lysosomal-associated transmembr. prot 4B | LPPYDDATA*VPSTAKEPPPP | 2063.03a + 4b |

| Slamf7, SLAM family member 7 | APNTFYSTV*QIPKV | 1564.83a + 6b |

| Tln1, Talin-1 | LPPSTGTFQEA*QSRLNEAAAG | 2145.05a + 4b |

Seven endogenous MHC II peptides were selected and synthesized as isotopically (13C, 15N) labeled peptides at a single amino acid residue, denoted here with (*).

Mass corresponds to the monoisotopic form of the selected peptide.

Predicted mass shift due to the incorporation of the isotopically labeled amino acid.

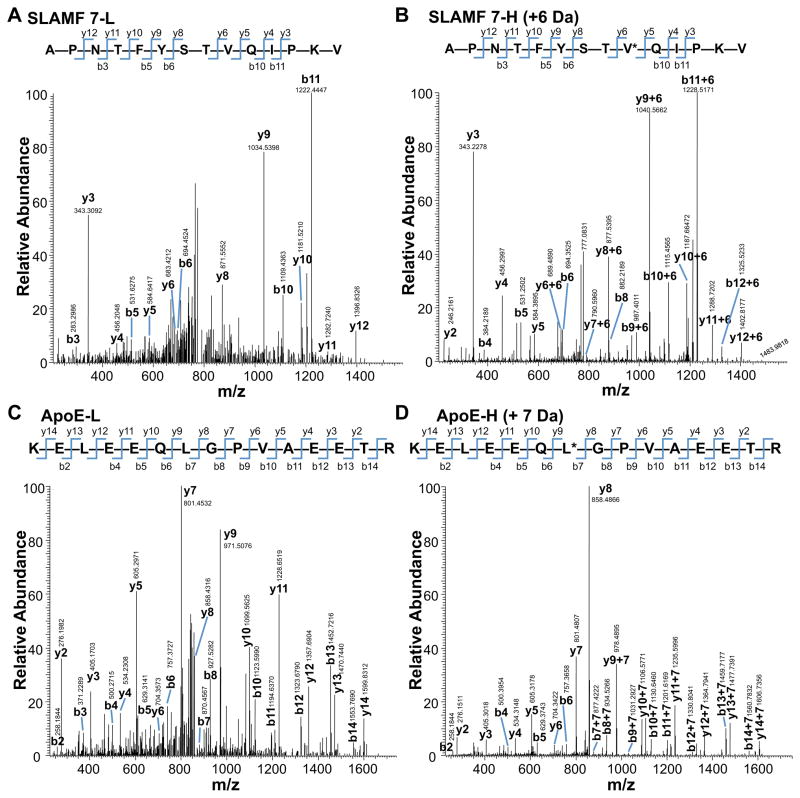

Figure 2.

Identification of two representative MHC class II binding peptides derived from DCs and B cells. Comparison of MS/MS spectra of naturally eluted peptides SLAM7 (A) and APOE (C), identified using MASCOT software in B cell and DC samples respectively, with MS/MS spectra of the matching synthetic isotopically labeled peptides for SLAM7 (B) and APOE (D). The corresponding y and b series are marked.

Prediction of peptide MHC II binding motifs

All source proteins were analyzed using the SYFPEITHI database (http://www.syfpeithi.de) for prediction of MHC II binding motifs. The SYFPEITHI program/database predicts epitope sequences that are likely to be presented by the selected MHC II molecules along with a score based on the presence of certain amino acids in certain positions of the class II MHC-binding groove (anchor motifs). For each protein analysis, we reported the top-scoring peptide MHC II binding motifs matching with our identified peptides (Table 1S).

Synthesis of isotopically labeled peptides

Peptides were synthesized in collaboration with the Proteomics Resource Center, Rockefeller University, New York, NY. All peptides were synthesized on a SYMPHONY™ multiple peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Tuscon, Arizona) on preloaded Wang resins (Bachem, Torrance, CA) at the 25 μmol scale, using Fmoc protected amino acids (Anaspec, Fremont, CA) 35, 36. Peptides were synthesized by the solid phase peptide synthesis method according to established protocols 37. Stable isotopically labeled Fmoc amino acids (Isotech, Miamisburg, OH) were introduced at appropriate positions (Table 1). They were uniformly labeled with 13C and 15N to attain a greater molecular weight shift (Table 1). They were incorporated into the peptide chain using 4–5 fold excess and coupling times of 8 h to ensure good coupling yields. Non-isotopically labeled Fmoc amino acids were coupled for 4 h. After the simultaneous deprotection of the side chain protecting groups and cleavage of the peptide from the Wang resin peptides were worked up using a standard butyl ether precipitation, dissolved in water and lyophilized. All crude lyophilized products were subsequently analyzed by reversed-phase UPLC (Waters Chromatography, Milford, MA, System: Waters Aquity™) using a Waters UPLC BEH C18 column. Individual peptide integrity was initially verified by electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry using a Finnigan LTQ (Thermo Finnigan, West Palm Beach, CA) spectrometer system. After the initial analytical characterizations peptides were then purified on a Waters 600 preparative HPLC system with VYDAC C18 column to greater than 99% purity. Peptides were resuspended at 1 mg/ml in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA in water prior their use in quantitative assays.

Quantitation of MHC II peptides

An absolute quantitation method based on the combination of exact mass measurements, their retention time and the comparison of profile intensity of light peptides and isotopically labeled (heavy) peptides was used to quantitate selected MHC II peptides 38, 39. Selected synthetic peptides for quantitation and their isotopically labeled counterparts are listed in Table 1. MHC II peptide mixture (10 μL) in 0.1 % TFA/water was mixed with 10 μL of a solution containing all 7 synthetic isotope labeled peptides dissolved in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA/water. The amount of synthetic isotopically labeled peptides spiked into the sample was 0.8 ng, except for the H-2 class II alpha chain peptide which was added as 2.8 ng. The entire peptide mixture was subjected for LC/MS analysis. Peptides were separated on the HPLC column under the same solvent gradient conditions as the ones described for the LC-MS/MS. The LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer was operated in the full scan mode with a resolution of 30,000. In the LC–MS experiments we measured the peak intensity of a specific ion from both the native peptide and the isotopically labeled peptide as a function of m/z values. The absolute quantification was determined by comparing the peak intensity of the native peptide with the peak intensity of heavy peptide added at the concentration indicated in table 6. The actual copy numbers of MHC II peptides from DCs and B cell were calculated as follows: 1) moles of native peptide determined by AQUA analysis = g/MW; 2) Molecules of native peptide = moles (from step 1) × 6.022 ×1023/mol; 3) Molecules of native peptide per cell = molecules (from step 2)/number of cells used per AQUA analysis.

Table 6. Quantitation experiments of selected MHC II associated peptides eluted from DCs and B cells.

Peptides were first identified from DCs and B cells by LC-MS/MS analysis (see Tables 2–5). Peptide abundance was then measured by LC-MS using stable isotope labeled peptides as internal standards (see Table 1 and Materials and Methods). Results are expressed as fmol/μL of sample and copies/cell and represent an average of 3 independent sample preparations (Fig. 1).

| Dendritic cells (n=3) | B cells (n=3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein/Peptide Sequence | Localization | Standard | fmol/μl | Copies/cell | fmol/μl | Copies/cell |

|

H-2 class II histocompatibility Ag, alpha chain ASFEAQGAL*ANIAVDKA |

membrane | 2.8 ng | 1.18 ± 0.25 ×104 | 1.53 ± 0.46 ×105 | 9.61 ± 0.016 ×104 | 1.18 ± 0.02 ×105 |

|

ApoE, Apolipoprotein E KELEEQL*GPVAEETR |

extracellular | 0.8 ng | 42 ± 5.46 | 548 ± 55.22 | 22.56 ± 0.98 | 298.67 ± 30.02 |

|

Cap1 Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 GPKPFSAP*KPQTSPSP |

membrane | 0.8 ng | 26.03± 4.48 | 347 ± 82.34 | 11.68 ± 2.11 | 133.33 ± 17.90 |

|

CtsZ, Cathepsin Z DLPVWEYA*HKHG |

lysosome | 0.8 ng | 27.96 ± 2.09 | 362 ± 22.09 | 27.03 ± 7.90 | 280 ± 69.28 |

|

Laptm4b Lysosomal-associated transmembr. prot 4B LPPYDDATA*VPSTAKEPPPP |

lysosome | 0.8 ng | 35.71 ± 0.23 | 477 ± 38.66 | 22.73 ± 2.54 | 273.33 ± 12.70 |

|

Slamf7 SLAM family member 7 APNTFYSTV*QIPKV |

membrane | 0.8 ng | 2.66 ± 0.52 | 35.6 ± 9.28 | 2.55 ± 1.10 | 13.3 ± 6.35 |

|

Tln1 Talin-1 LPPSTGTFQEA*QSRLNEAAAG |

cytosol | 0.8 ng | 48.17 ± 15.90 | 614 ± 153.91 | 71.32 ± 29.06 | 680.67 ± 325 |

Functional profile analysis

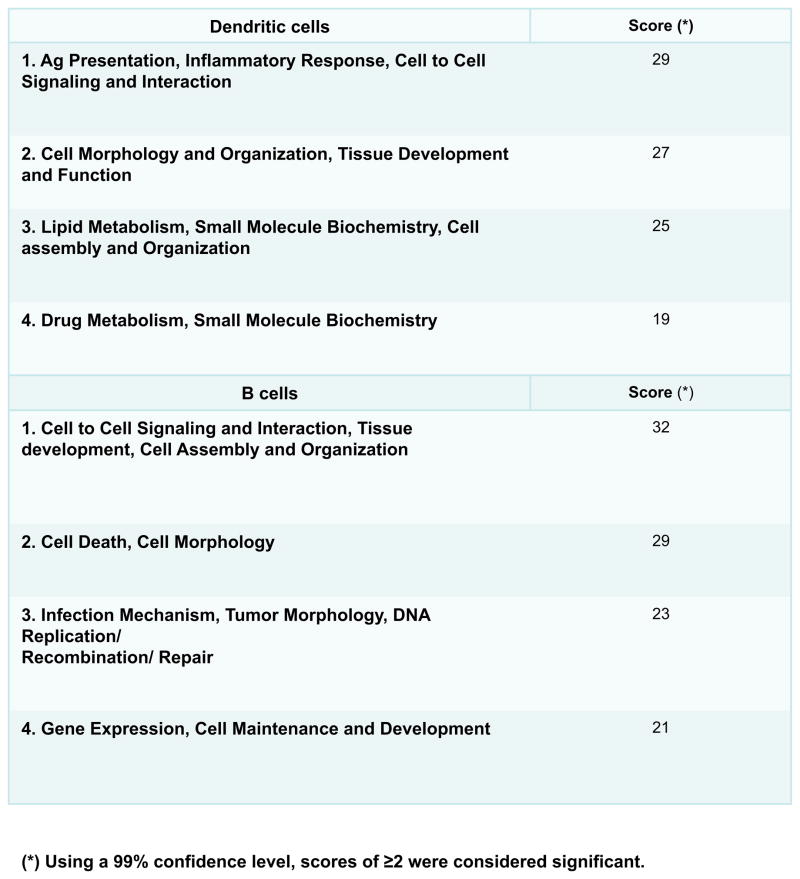

The functional networks analyses were executed using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com) software that enables the exploration of molecular interaction networks of source protein data sets. The list of source proteins, identified by MS/MS analysis in one representative experiment and containing IPI numbers as identifiers, were uploaded onto the Ingenuity pathway analysis software (IPA). A score was computed for each network according to the fit of the original set of significant genes. This score reflects the negative logarithm of the P value that indicates the likelihood of the focus genes in a network being found together due to random chance. Using a 99% confidence level, scores of ≥2 were considered significant.

Results

Endogenous peptides eluted from MHC II molecules of DCs and B cells derive from all major cellular compartments

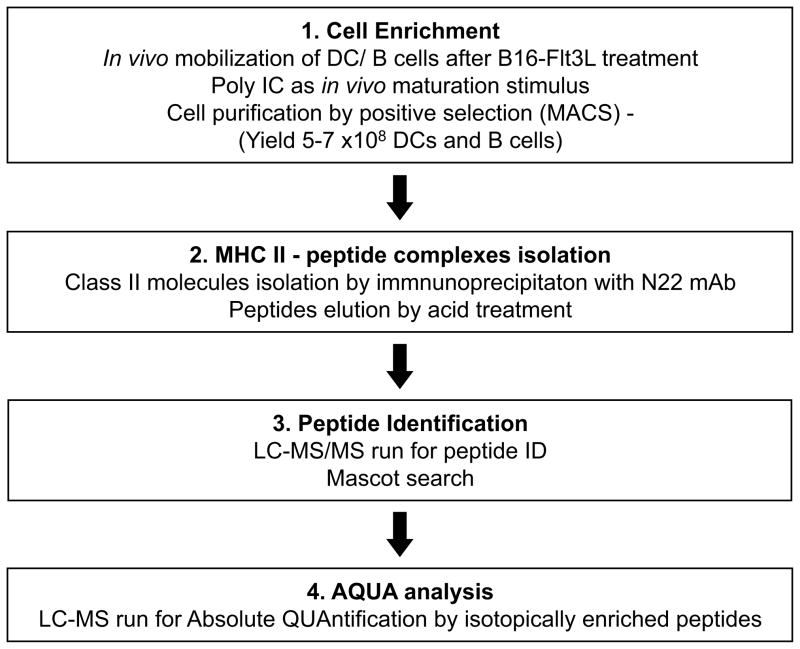

Fig. 1 summarizes the workflow for the MS-based experiments that we used to characterize the repertoire of MHC II peptides on splenic DCs. We also applied this approach to B cells, where prior work had identified peptides bound to their MHC II molecules 13, 18. Spleen DCs (5–7×108) and B cells (6–8×108) were obtained in four independent experiments from the same pool of 12–17 Flt3L treated mouse spleens. Poly IC was administered in vivo for 5 hr as a maturation stimulus to increase the antigen presentation activity of DCs and possibly of B cells 22, 40–47. Maturation stimuli have been demonstrated to increase the half-life of surface MHC II peptides in activated DCs compared to immature DCs that retain large amount of MHC II molecules in intracellular antigen-processing compartments48–50.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram summarizing the steps performed to identify peptides presented by MHC II molecules on DCs and B cells, from sample preparation to peptide identification by LC-MS/MS and quantitation by LC-MS.

Overall, we performed peptide elutions and LC-MS/MS analysis on 7 biological replicates from DCs and 4 from B cells. In each experiment we were able to identify from freshly isolated murine splenic DCs and B cells up to 200 peptide sequences presented by MHC II molecules. In Tables 2–5, we included only peptides identified in multiple biological replicates (n=7 for DCs and n=4 for B-cells) by the MASCOT software and confirmed by SEQUEST and X!tandem search engines. This software search, though, may have excluded additional peptide sequences that were present at levels below the detection limits set by the instrument for an automatic search and sequencing 51. As shown in Tables 2–5, the majority of detected peptides were 15–25 amino acids long, and several were clustered in nested sets consisting of 3–10 sequences, in agreement with published reports for B cells, macrophages, and B cell-derived cell lines 13, 14, 19–21. A considerable number of single peptide sequences were also detected52, 53 and they originated from different cellular compartments.

Table 2. MHC II binding peptides derived from membrane proteins of DCs and B cells (a).

Endogenous peptides were eluted from immunoprecipitated MHC II molecules on DCs and B cells. Peptide sequences were identified by tandem MS, and the corresponding source proteins were obtained by searching peptide sequences against the IPI database for mouse proteins using the MASCOT algorithm (see Materials and Methods). Only peptides with a MASCOT score greater than 20 and mass accuracy better than 5 ppm were included. Sequences highlighted in bold letters were selected for further quantitation analysis (see Table 1).

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| H-2 class II, alpha chain | A.NIAVDKA.N | DC |

| Q.GALANIAVDK A | DC | |

| E.AQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| F.EAQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| S.FEAQGALANIAVD.K | DC/B cell | |

| F.EAQGALANIAVDKA.N | DC/B cell | |

| S.FEAQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| F.ASFEAQGALANIAVD.K | DC/B cell | |

| S.FEAQGALANIAVDKA.N | DC/B cell | |

| A.SFEAQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| F.ASFEAQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| F.ASFEAQGALANIAVDKA.N | DC/B cell | |

| K.FASFEAQGALANIAVDK.A | DC/B cell | |

| K.FASFEAQGALANIAVDKA.N | B cell | |

|

| ||

| CD74 H2-class II gamma chain (CLIP) | A.KPVSQMRMATPLLMRP.M | DC/B cell |

| A.KPVSQMRMATPLLMRPM.S | DC | |

| A.KPVSQMRMATPLLMRPM.S | DC | |

|

| ||

| H2-Eb1, beta chain | F.IYFRNQKGQSGLQPTGLL.S | DC |

|

| ||

| H-2 class II, beta chain | H.NYEGPETSTSLR.R | DC |

| C.RHNYEGPETSTSL.R | DC | |

| R.HNYEGPETSTSLR.R | DC | |

| C.RHNYEGPETSTSLR.R | ||

|

| ||

| Igh 6 prot; Ig mu chain C | L.LPQEKYVTSAPMPEPGAPG.F | DC/B cells |

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| SLAM family member 7 | D.APNTFYSTVQIPKV.V | DC/B cells |

| D.APNTFYSTVQIPKVV.K | DC | |

| A.PNTFYSTVQIPKVVK.S | DC | |

| E.DAPNTFYSTVQIPKVVK.S | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| EVI2B | L.PNKPTVTVVSPLPNDS.I | DC |

| N.KPTVTVVSPLPNDSINPQP.S | B cell | |

|

| ||

| Ptprn | R.RPGGSGGSGGSGGLRLLV.C | DC |

| R.MAKGVKEIDIAATLE.H | B cell | |

|

| ||

| Ace2 | P.WTKALENVVGARNM.D | DC/B cells |

|

| ||

| Germinal center transcript 2 | F.SSHAFQQPRPLTTPY.E | DC |

|

| ||

| Icos ligand | Y.LPYKSPGINVDSS.Y | DC |

| Y.LPYKSPGINVDSSY.K | DC | |

|

| ||

| CD97 | L.EDFYGSPIPSVSLK.L | DC |

| S.LEDFYGSPIPSVSLK.L | DC | |

|

| ||

| Annexin 6 | T.GKPIEASIRGELSG.D | DC |

| G.KPIEASIRGELSGDF.E | DC | |

|

| ||

| Sorl1 sortilin related receptor | I.DPYDQPNAIYIER.H | DC |

|

| ||

| Itgax Integrin alpha-X | V.SPTVHFTPAEISR.S | B cell |

|

| ||

| Entpd1 | M.LNLTNMIPAEQPLSPPLPHSTY IGLM.V | B cell |

|

| ||

| Ilk | -.NLLQYKADINAVNE.H | B cell |

|

| ||

| Gramd1a | F.HHLDRELAKAEK.L | B cell |

|

| ||

| Grik1 | S.NSGLNMTDGNRDRSNNI.T | B cell |

The rate of detection of the peptides by LC-MS/MS analysis shown in table was 100% (i.e. in 7/7 separate biological replicates for DC and 4/4 biological replicates for B cells)

Table 5. MHC II binding peptides derived from extracellular proteins of DCs and B cells (a).

Peptides and their source proteins were identified as described in Legend to Table 2.

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein B48 receptor | T.ATEQAVEIRAEGGQE.A | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Apolipoprotein E | L.EEQLGPVAEETRAR.L | DC/B cell |

| K.ELEEQLGPVAEETR.A | DC/B cell | |

| K.ELEEQLGPVAEETRA.R | DC/B cell | |

| E.EQTQQIRLQAEIFQ.A | DC/B cell | |

| K.KELEEQLGPVAEETR.A | DC/B cell | |

| Y.KKELEEQLGPVAEETR.A | DC | |

| Y.KKELEEQLGPVAEETRA.R | DC | |

|

| ||

| Beta globin | A.FQKVVAGVAAALAH.K | DC/B cell |

| A.FQKVVAGVAAALAHK.Y | DC/B cell | |

| A.AFQKVVAGVAAALAHK.Y | DC/B cell | |

| A.FQKVVAGVAAALAHKY.H | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| ASM-like phosphodiesterase 3a | G.NPLNSVFVAPAVTPVK.G | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Fibronectin | L.NPGTEYVVSIIAVNGRE.E | DC/B cell |

| L.NPGTEYVVSIIAVNGREE.S | DC | |

|

| ||

| Apolipoprotein B | T.NFFHESGLEARVALK.A | DC |

| T.NFFHESGLEARVALKA.G | DC | |

| N.KKITEVSLVGHLSYDKK.G | DC | |

|

| ||

| Fibrinogen, alpha | R.KVIEKAQQIQALQSNVR.A | DC |

|

| ||

| Hba-a1 hemoglobin alpha | L.ASVSTVLTSKYR. | DC |

| D.KFLASVSTVLTSKYR. | DC | |

|

| ||

| Sortilin-related receptor | I.DPYDQPNAIYIER.H | DC |

|

| ||

| Pld4 phospholipase D4 | R.SLQAFSNPSAGISVDVK.V | DC |

|

| ||

| Serum albumin | I.LVRYTQKAPQVSTPTLV.E | DC |

|

| ||

| Serotransferrin | E.HPQTYYYAVAVVKK.G | DC |

| E.HPQTYYYAVAVVKKGTD.F | DC | |

|

| ||

| Vcan, Versican | Y.TCKKGTVACGQPPVVENAKTFGKMKPRYEI.N | B cell |

|

| ||

| Metrn, Meteorin | V.FAERMTGNLELLLAEGPDLAGGRCMR.W | B cell |

|

| ||

| Serpina 3c | Y.KKLALKNPDTNIVFSPL.S | B cell |

The rate of detection of the peptides by LC-MS/MS analysis shown in table was 100% (i.e. in 7/7 separate biological replicates for DCs and 4/4 biological replicates for B cells)

To confirm peptide identity and to perform further quantitation analysis (next section), a subset of identified peptides were synthesized as isotopically labeled peptides (Table 1). LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on the synthetic peptides, and obtained fragmentation spectra were compared with the corresponding spectra of the naturally presented MHC II peptides eluted from DCs and B cells. Fig. 2A and 2C shows the MS/MS spectra from two representative peptides that have been identified as APNTFYSTVQIPKV and KELEEQLGPVAEETR, respectively from SLAM family member 7 (Slamf7) and apolipoprotein E (ApoE). For comparison, sequences of synthetic isotopically labeled Slamf7 and ApoE peptides are shown on Fig. 2B and 2D. As seen from Fig. 2A–D the naturally processed peptides and the corresponding synthetic isotopically labeled peptides demonstrated an essentially identical product ion spectrum, confirming the validity of MASCOT identification.

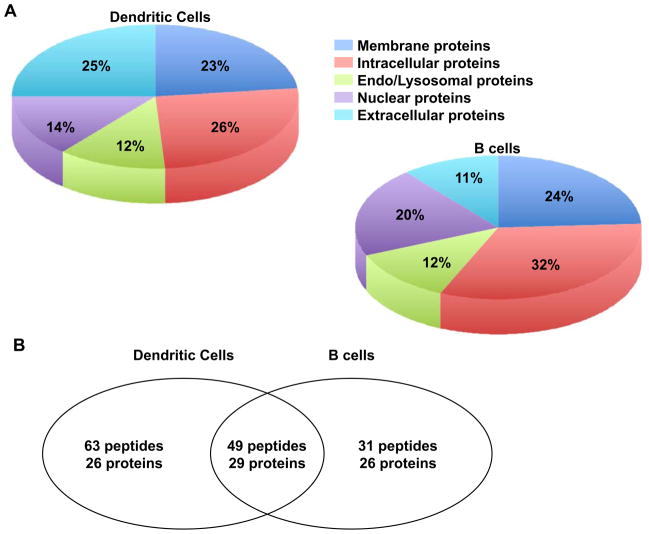

Peptides were classified according to source proteins they were derived from. We found in multiple biological replicates (n=7 for DCs and n=4 for B-cells) about 112 peptides as MHC II ligands isolated from DCs and about 80 peptides from B cells, corresponding to a total of around 80 proteins from membrane, extracellular, intracellular and nuclear compartments (Tables 2–5 and Fig. 3A). The rate of detection of peptides listed in Tables 2–5 was 100 % in 7 biological replicates of DCs and 4 of B cells. As seen from Tables 2–5 and Fig. 3B, a significant number of class II-bound peptide sequences were shared by DCs and B cells and were derived from similar cellular compartments. We identified more peptides in DCs than in B cells, but the number of source proteins was quite comparable (Fig. 3B). Forty-nine MHC class II-bound peptide sequences originating from 29 proteins were shared by DCs and B cells.

Figure 3.

Cellular localization of source proteins for endogenous MHC II peptides. A) Pie charts and percentages of source proteins identified as MHC II peptides endogenously presented by DCs and B cells in multiple biological replicates (n=7 for DCs and n=4 for B cells). B) Venn diagram representation of the overlap of endogenous MHC II peptides eluted from DCs and B cells in multiple replicates as indicates above.

In previous reports that analyzed established cell lines 13, the majority of the identified peptides were derived from membrane or secreted proteins such as MHC class II, invariant chain, beta globin, LDL receptor, apoliproproteins B and E. Importantly, here we showed that more than 50% of the endogenous MHC II peptides from mouse splenic DCs and B cells were derived from cytosolic proteins. These proteins include intracellular proteins from cytoskeleton (actin, plastin-2, cap-1, catenin) or constitutive enzymes (ubiquitin hydrolase, NADH dehydrogenase, cytocrome c oxidase), endo/lysosomal proteins involved in antigen processing and vesicular trafficking (cathepsin z, Rab6A, Lamp4B) and nuclear proteins such as transcription factors (NPAT protein, homeobox D13, zinc finger 516) and DNA binding proteins (histone cluster 3 H2bb, splicing factor 3B) (Table 2–5). Peptides that originate from exogenous sources are present at high amount in the extracellular space, such as serum albumin or transferring (Table 5). These results indicate that the repertoire displayed on DCs as well as B cells is large, overlapping and derived from all cellular compartments (Fig. 3A).

Proteomic analysis of mouse DC subsets54 reflected an exclusive expression of pattern recognition pathways. In three previous proteomic studies 55–57, the proteins identified in human DCs were classified only in two major classes: cytoskeleton-related proteins and chaperons.

The intracellular localization of the source proteins for MHC II peptides in murine spleen DCs and B cells shown in Fig. 3A is different from what has been reported for the intracellular distribution of mammalian proteins. Because the characterization of the subcellular mammalian proteome is still incomplete, the assigned intracellular localization of mammalian proteins depends on the method used to characterize their location. For example, Protein Correlation Profiling of about 1400 proteins fractionated from mouse liver localized about 35 % to the cytosol, 14 % to the nucleus and 18% to the plasma membrane58. Another approached that utilized antibody-based immunofluorescence to map the intracellular distribution of over 3500 proteins in the human A-431 epidermoid carcinoma, U-2 osteosarcoma and U-251 MG gliobliostoma cell lines by confocal fluorescence microscopy found that about 32% of the proteins were localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus59. On the other hand, bioinformatics analysis of 6900 human proteins demonstrated the majority of proteins are located in the nucleus (38%) and plasma membrane (23.3%)60. The later approach integrated information deposited in 3 different data bases (protein-protein interaction, PPI, metabolite-linked protein interactions, MPLI, and protein-subcellular localization, SCL. Despite these differences, the general conclusion of the above mentioned studies is that the intracellular distribution of mammalian proteins is not homogenous, in contrast to our findings shown in Fig. 3A.

Identified MHC II peptide sequences in DCs and B cells contain the predicted binding motifs

There was a very good correlation between the identified MHC II peptides by LC-MS/MS and the sequences that were predicted to optimally bind to H-2Ad and H-2Ed molecules by the epitope prediction algorithm developed by Rammense et al61 (Table 1S). About 90 different binding motifs were found. For some of the MHC II binding peptides, like for example the H-2 class II alpha chain, a single binding frame was found in the 12 identified peptides ranging in size from 20 to 14 amino acids (Table 2 and Table 1S). The 14-amino acid long peptide had a high binding score of 29. Majority of the H-2 class II alpha chain peptides contained N-terminal extension of the 14 amino acid core sequence, and few contained short C-terminal extensions. These findings suggest that in DCs and B cells amino peptidases are predominately responsible for the generation of the high affinity binding core sequence of the H-2 class alpha chain binding protein62.

We also identified different MHC II binding peptides originating from a single source protein that contained several different predicted binding motifs. For example, we identified three MHC II binding peptides derived from Apolipoprotein B, two of which contained different binding motifs. One of these peptides, T.NFFHESGLEARVALK.A, has a high binding score of 31 and a second one with a different binding motif N.KKITEVSLVGHLSYDKK.G has a score of 18 (Table 5 and Table 1S). For actin, three peptides (L.RVAPEEHPVL.L; E.LRVAPEEHPVL.L; F. YNELRVAPEEHPVL.L) each with a different predicted binding motif and binding scores of 7, 10 and 20, respectively were identified (Table 3 and Table 1S). Two binding motifs were found in the three peptides derived from the Fanconi anemia complementation B protein (Table 4 and Table 1S). Two of these peptides, Y.AEMTLALAEIQLKS.D and A.EMTLALAEIQLKS.D were identified in both DCs and B cells, while the third peptide I.QLKSDLIVKTL.A was identified only in DCs.

Table 3. MHC II binding peptides derived from intracellular proteins of DCs and B cells (a).

Peptides and their source proteins were identified as described in Legend to Table 2.

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| Plastin-2 | S.SIASFKDPKISTSLP.V | DC |

| S.SIASFKDPKISTSLPV.L | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| Cap 1, Adenylyl cyclase-associated 1 | R.SGPKPFSAPKPQTSPSPKP.A | B cell |

| S.GPKPFSAPKPQTSPS.P | DC/B cell | |

| S.GPKPFSAPKPQTSPSP.K | DC/B cell | |

| S.GPKPFSAPKPQTSPSPK.P | DC | |

| R.SGPKPFSAPKPQTSPSPK.P | DC | |

| S.GPKPFSAPKPQTSPSPKP.A | DC | |

|

| ||

| Catenin alpha-2 | A.GSRMDKLARAVADQ.C | DC/B cell |

| E.AGSRMDKLARAVADQ.C | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| Hook homol. 3 | E.EKSSLLAENQILME.R | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Talin-1 | L.LPPSTGTFQEAQSRLNEAAAG.L | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Actin | L.RVAPEEHPVL.L | DC |

| E.LRVAPEEHPVL.L | DC | |

| F.YNELRVAPEEHPVL.L | DC | |

|

| ||

| Suppressor cytok. signal 7 | T.ETSDALLVLEGLESEA.E | DC |

|

| ||

| Rps15a 40S | R.MNVLADALKSINNAE.K | DC |

|

| ||

| Usp13 ubiquitin C-term hydrolase | G.ALFSVPGGGGKMAAGDLG.E | DC |

|

| ||

| similar axo dynein hc 8 | T.SCGNALLVGVGGSGKQ.S | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Prot. shisa 5 | T.GPPPYHESLAGASQPP.Y | DC |

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| Rpl30 60S | D.PGDSDIIRSMPEQTGEK. | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Ndufa4 NADH dehydrogenase | I.GAGGTGAALYVMRL. A | DC |

| F.IGAGGTGAALYVMRL.A | DC | |

| F.IGAGGTGAALYVMRL. A | DC | |

|

| ||

| Cox6a1 cytochrome c oxidase poly peptide | M.SSGAHGEEGSARMWKALT.Y | DC/B cell |

| P.GLRRPMSSGAHGEEGSARM. W | DC | |

|

| ||

| Atp5j, ATPase subunit F6 | D.PKFEVIDKPQS. | B cell |

|

| ||

| KIF1 binding prot. | E.KFQAALALSRVEL.H | B cell |

|

| ||

| Bcar3 | F.QMRLLWGSKGAEVN.Q | B cell |

|

| ||

| Oas1b, oligoadenylate synthetase 1B | K.GKCTALKGRSDADLV.V | B cell |

|

| ||

| Bscl2, Seipin | G.FAEQKQLLEVEL.Y | B cell |

|

| ||

| Nmral1 NmrA-like family domain-containing protein 1 | V.FGATGAQGGSVARALLE.D | B cell |

|

| ||

| Sharpin | D.PERPGRFRLGLLGTEPGAVSLE.W | B cell |

|

| ||

| Atg4d cysteine protease | T.RIPDPSNLGPSGSGVAALGSSGTDPAEP.D | B cell |

|

| ||

| Cntln Centlein | H.ACKTSTHKA.Q | B cell |

|

| ||

| Notch2 | E.SPDQWSSSSPHSASD.W | B cell |

The rate of detection of the peptides by LC-MS/MS analysis shown in table was 100% (i.e. in 7/7 separate biological replicates for DC and 4/4 biological replicates for B cells)]

Table 4. MHC II binding peptides derived from endo/lysosomal and nuclear proteins of DCs and B cells (a).

Peptides and their source proteins were identified as described in Legend to Table 2.

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| Integral membrane prot.2B | R.YQTIEENIKIF.E | DC/B cell |

| R.YQTIEENIKIFE.E | DC | |

| V.KVTFNSALAQKEAK.K | DC | |

| V.KVTFNSALAQKEAKK.D | DC | |

| R.YQTIEENIKIFEED.A | DC | |

|

| ||

| Cathepsin Z | N.DLPVWEYAHKHG.I | DC/B cell |

| G.NDLPVWEYAHKHG.I | DC | |

|

| ||

| Ras related prot Rab-6A | I.MLVGNKTDLADKRQ.I | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Spg3a | S.MLQATAEANNLAAVAT.A | DC |

|

| ||

| Tyr prot phophatase non rec 23 | L.LREMLAKIEDKNE.V | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Snx17 Sorting nexin 17 | Q.VPTEEVSLEVLLSNGQK.V | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Lysosomal transmembrane prot. 4B | L.LPPYDDATAVPSTAKEPP.P | DC |

| L.LPPYDDATAVPSTAKEPPP.P | DC/B cell | |

| L.LPPYDDATAVPSTAKEPPPP.Y | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| Stx5a Syntaxin-5 | G.SIFQQLAHMVKE.Q | B cell |

|

| ||

| Acp5 Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5 | E.ISPKEMTIIYVEASGK.S | B cell |

| E.ISPKEMTIIYVEASGKS.L | B cell | |

| PROTEIN NAME | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | CELL TYPE |

|---|---|---|

| NPAT | S.QIPTEAEVAVGEK.N | DC |

| L.FASQIPTEAEVAVGEK.N | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| Homeobox D13 | V.PYTKLQLKELENE.Y | DC/B cell |

|

| ||

| Fancb Fanconi anemia, complementation B | I.QLKSDLIVKTL.A | DC |

| A.EMTLALAEIQLKS.D | DC/B cell | |

| Y.AEMTLALAEIQLKS.D | DC/B cell | |

|

| ||

| Histone demethylase JARID1D | S.FDNWANKVQAALEV.E | DC |

|

| ||

| Zinc finger prot.516 | L.RSSRKEVEGAASAQE.D | DC |

|

| ||

| Sart3 squamous cell carcinoma Ag by T cells 3 | L.EDWDLAIQKTETR.L | DC |

|

| ||

| Histone cluster 3, H2bb | V.NDIFERIASEASR.L | DC |

|

| ||

| Aff3 42kDa | P.FPNKENENSLVWK.E | DC |

|

| ||

| Wiz | -.MEGLLAGGLAAPDHPR.G | B cell |

|

| ||

| Prdm10, PR domain 10 | I.TDSGVATPVTSGQVKA.V | B cells |

|

| ||

| Hltf Helicase-like transcription factor | E.FDKLFEDLKEDDRT.V | B cell |

|

| ||

| Ehmt1 | L.QMSKALRDSAPDK.P | B cell |

|

| ||

| Foxd1 forkhead box D1 | A.SRPAASPAPPGPAPAPGTGSGGCSGAGAGGG.A | B cells |

|

| ||

| Sf3b3 Splicing factor 3B | V.NQRQVVIALTGGELVYF.E | B cell |

The rate of detection of the peptides by LC-MS/MS analysis shown in table was 100% (i.e. in 7/7 separate biological replicates for DCs and 4/4 biological replicates for B)

Several endogenous MHC II peptides are present at comparable levels in DCs and B cells

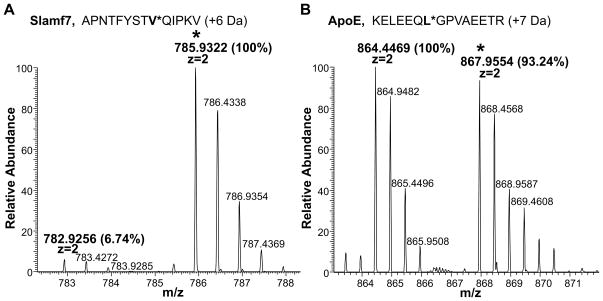

To evaluate the absolute abundance of MHC II peptides originating from different cellular compartments in DCs and B cells we performed a quantitation of selected peptides previously identified after LC-MS/MS analysis in these cell types. Our approach for peptides quantitation involved the use of isotopically labeled peptides as internal standards to quantify its natural endogenous counterpart38. We selected as quantitative targets 7 peptides derived from different cell compartments that were consistently detected in DCs (n=7) and B cells (n=4) (Tables 2–5). First, we synthesized heavy isotope-labeled peptides corresponding to the endogenous counterparts introducing a single amino acid that was isotopically labeled with 13C, 15N (Table 1). We added them as internal standards in the peptide mixture just prior to the LC-MS run (Fig. 1 and Table 6). Samples were analyzed by LC-MS and peak intensities of the unlabeled and the isotopically labeled pairs were compared. Fig. 4 shows, as an example, MS traces of the APO E peptides pair measured in the DCs sample (Fig. 4B) and of the SLAM 7 peptides pair measured in the B cells sample (Fig. 4A). Results summarized in Table 6 represent the amount of endogenous peptides calculated from three independent biological replicates performed over several months and show a very good agreement between them.

Figure 4.

Absolute Quantitation Analysis (AQUA) by LC-MS of selected MHC II endogenous peptides. Synthetic isotopically labeled peptides (0.8 ng) were spiked into DC and B cell samples. Quantitation of endogenous counterparts was obtained comparing peaks’ intensity of the selected peptide pair. Heavy isotopes peaks are indicated with a (*). Each peptide was analyzed separately after LC-MS run. A) MS profile of the SLAM 7 peptides pair identified in the MHC II peptide mixture eluted from one representative B cell sample. B) MS profile of the Apo E peptides pair identified in the MHC II peptide mixture eluted from one representative DC sample. Isotopic patterns of the ions were consistent with the predicted patterns based on the isotopic ratios. Mass shifts of the isotopically labeled peptides are consistent with the predicted values (see Table 1).

Quantitation of one of the peptides originating from the H-2 class II alpha chain showed that it was presented on the MHC II molecules in both DCs and B cells at similar levels of 1.18×105 copies per cell (Table 6). This peptide was unusually abundant in our studies. Quantitation of another peptide originating from a membrane protein, Cap1 adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1, showed that it was presented on the MHC II molecules in DCs and B cells at similar levels as most of the other selected peptides originating from proteins found in extracellular, lysosomal and cytosolic cellular compartments respectively i.e. about 133±18 copies per cell vs 299±30 copies per cell for Apolipoprotein E; 280±69 copies per cell for cathepsin Z and 273±13 copies per cell for Talin-1, respectively. But the peptide originating from the membrane protein SLAM family member 7 was present in both DCs and B cells at a very low level of 13±6 copies per cell (Table 6).

As shown in Table 6, our approach resulted in the detection from a single experiment of a wide range of peptide concentrations starting from about 2.55 fmol/μL to 11.18 pmol/μL of sample or about 4000 fold difference in concentrations. Thus, in a single experiment, both excellent sensitivity and wide dynamic range were achieved. It should be noted that the concentration of detected peptides calculated in this way represents an underestimation of the actual concentration of these peptides bound to the MHC II complex in the DCs and B cells, respectively, because we added the isotopically labeled peptides in the sample aliquot prior to the LC-MS run and after the peptides were immunoprecipated and purified through 10 kD filter and C-18 column where some loss of peptides takes place 38.

Quantitative results summarized in Table 6, although limited to 7 peptides, demonstrated that DCs and B cells express comparable levels of not only peptides derived from the H-2 class II alpha chain, but also of other peptides derived from other membrane proteins as well as extracellular and lysosome/cytosol proteins. These findings establish that not only the endogenous MHC II peptides repertoire of splenic DCs and B cells partially overlap but that many of the MHC II class associated peptides are presented on DCs and B cells at comparable levels.

MHC II peptide repertoire identified in DCs and B cells underlines their distinct immunological functions

To evaluate the physiological relevance of the repertoire of MHC II class associated peptides in freshly isolated splenic DCs and B cells detected by LC-MS/MS, we further analyzed the repertoire by the Ingenuity Functional Network Analysis ®63. As input for the Ingenuity analysis we used the IPI protein numbers obtained in one representative experiment in which 80 proteins were identified by the MASCOT software in DCs and 75 in B cells. Ingenuity software assigned the source proteins of the MHC II class associated peptides in DCs and B cells to cellular networks that characterize their distinct immune functions (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

MHC II peptide repertoire in DCs and B cells reflects their distinct roles in the immune system. The functional analysis was generated through the use of Ingenuity Pathways Analysis Software (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Data sets of source proteins identified from MHC II peptide analysis of DCs and B cells in one representative experiment were uploaded into Ingenuity application. The biological functions that had the most significant (score ≥) are shown (see Materials and Methods).

In DCs, antigen presentation, inflammatory responses, cell to cell signaling and interaction networks were ranked with top scores.

The proteins listed for the antigen presentation in DCs included proteins derived from all the cellular compartments, in particular several representative of the HLA DR molecules (HLA- DR, HLA- DRB1, the invariant chain CD74, and the cystein protease Cathepsin Z responsible for intracellular protein degradation (Fig. 1S). Proteins grouped in the cell to cell signaling and interaction network include several that mediate cell adhesion, migration and signaling (talin 1, TLN1; fibronectin 1, FN1; capain cysteine protease, CAPNS1) as well as proteins involved in membrane and protein trafficking (Ras-related protein Rab6A, annexin 6), and the membrane channel protein pannexin 1 involved in membrane permeability. The common extracellular proteins, apolipoprotein B (APOB) involved in lipid transport, apolipoprotein E (APO E) that mediates binding, and internalization of lipids, and fibrinogen alpha gene, FGA, involved in fibrinogen network also grouped in this network.

Networks with highest scores in B cells were cell to cell signaling and interaction, tissue development, cell assembly and organization, cell death and cell morphology, infection mechanism, tumor morphology and DNA replication, recombination and repairs (Fig. 5, Fig. 1S). Several proteins involved in the regulation of transcription segregated in the later network. They were, the zinc-finger containing protein, WIZ, and several members of the histone lysine-N-methyltransferases (EHMT1 targeted to histone H3, NPAT that activates the transcription of histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4; ATX5 that inhibits transcription). Fanconi anemia group B protein (FANCB) involved in DNA repair grouped in the same network. The network also included SHISA5 protein involved in regulating responses to cellular stress through apoptosis in a capase-dependent manner; SHARPIN, the shank-interacting protein 1 which plays a role in NF-kappa B activation of inflammation, and several proteins the promote vesicle trafficking (HOOK 3 and SNX17).

The cell signaling and interaction network in B cells was characterized by a different set of proteins from the ones listed for DCs. They were the ANXA1 member of the annexin family that mediates anti-inflammatory responses, ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase that has a role in vascular development, BCAR3 that promotes cell migration, CAP1, adenyl cyclase associated protein 1 that regulates developmental and morphological processes, ILK, integrin like protein kinase that mediates cell architecture, ITGAX, integrin alpha X involved in cell-cell interactions during inflammation, MOV10L1 which is a RNA helicase involved in cell cycle progression, VCAN which has a role in cell adhesion, and TLX1, T-cell leukemia homebox protein required for normal development of the spleen. Proteins that grouped in the cell morphology network were cytochrome C oxidase subunit, COX6A1, that mediates mitochondrial electron transport, protein diaphanous homolog 1, DIAPH1, required for the assembly of F-actin structures; 2′-5′ oligonucleotide synthesase 1B, OAS1b, which controls cell growth and differentiation and Ras-related protein Rab-B which mediates retrograde membrane traffic. Several transcriptional factors also were grouped in this network. These were helicase-like transcription factor, HLTF, which maintains genome stability through posttranscriptional repair of damaged DNA, the splicing factor SFPQ, which regulates posttranscriptional processes and the forkhead box protein D1, FOXD1. Only few proteins that were grouped in the cell to cell signaling and interaction network were shared between DCs and B cells. These were apolipoprotein E (APOE) and fibronectin 1 (FN1).

Discussion

The actual sequences of peptides that are naturally presented on MHC II molecules cannot be easily predicted, in fact such peptides have been demonstrated to display a high degree of heterogeneity in both length and site of their natural truncations17, 64, 65. To our knowledge, our report provides for the first time a qualitative and quantitative profile by LC-MS/MS analysis of the endogenous MHC II peptides presented in vivo by DCs.

Results of our studies demonstrate that it is feasible to use murine spleen DCs expanded in vivo by treatment with Flt3L to identify the repertoire of MHC II binding peptides by LC-MS analysis. About 10–20 fold lower numbers of DCs were needed for proteomic analysis compared to what is described in other reports for cell lines13, 14. Also, we used smaller numbers of mice to obtain the DCs compared to the numbers used in other studies, which have concentrated on DCs generated from bone marrow cultures rather than DCs taken directly from mice54, 66. Flt3L treatment expanded the number of murine splenic DCs to be comparable to the yield of splenic B cells isolated from the same pool of 12–17 treated mice, and was typically in the range 5–7× 108 cells. This allowed a direct comparison of the MHC II peptide repertoire in the two types of immune cells.

The application of the AQUA strategy for the absolute quantitation using synthetic isotopically labeled peptides enabled in a single experiment the measurement of the abundance of several peptides presented on the MHC II molecules in DCs and B cells. These quantitative data were robust enough to overcome the dynamic range of copy numbers that spanned several orders of magnitude. Our quantitation results (Table 6) indicate that there is a large difference in the in vivo presentation of different endogenous MHC II peptides both in DCs and B cells, with about 4000 fold differences in amounts between the most abundant H-2 class II alpha chain peptide and the least abundant peptide originating from the lymphocyte antigen SLAM family member 7. This wide difference in presentation of endogenous MHC II peptides derived from different proteins in DCs and B cells is about 20 fold higher than previously reported for the four immunogenic MHC II epitopes derived from a single protein, hen egg-white lysozyme, quantitated in the B cell lymphoma line 16.

Additional conclusions from our studies can be placed in the context of findings in several fields. First, we observed a very good agreement between the MHC II peptide sequences identified in our LC-MS/MS experiments (Tables 2–5) and the predicted single binding motifs for these MHC II bound peptides (Table 1S). Almost all of the identified MHCII peptides originating from different endogenous source proteins in DCs and B cells contained the predicted single binding motifs with binding scores in the range of 31 to 7 (Table 1S). Although many peptides presented by MHC II molecules have a significant binding affinity score above 20, we also found some MHC II peptides with low scores. This is in part expected for peptides presented on MHC II molecules on mouse splenic DCs and B cells because the SYFPEITHI database does not fully cover all different mouse MHC II haplotypes, for example H2-Ab in our mice. The majority of identified MHC II binding peptides was larger than the 15 amino acid long sequences used in the predictive model. Taken together, these observations suggest that the predictive algorithm is useful in the global prediction of the peptide sequences that bind to MHC II molecules in murine spleen DCs and B cells, but that the LC-MS/MS analysis is required to obtain their exact sequences.

Second, we find that in DCs and B cells the majority of naturally presented peptides identified from MHC II complexes originate from proteins distributed at roughly comparable levels in the plasma membrane, intracellular and nuclear compartments, and proteins resident in endosomal and lysosomal organelles 13, 14, 18. There have been several reports that estimated the distribution of mammalian proteins in different cellular compartments. Foster et al. reported that about 35% from about 1400 proteins fractionated from mouse liver are localized in the cytosol, 14% in the nucleus and 18% in the plasma membrane58. Fagerberg et al. found that over 3500 proteins in three human cell lines are primarily distributed in the cytoplasm and nucleus59, while Kumar and Ranganathan reported that the majority of the analyzed 6900 human proteins are localized in the nucleus (38%) and plasma membrane (23%)60. The general conclusion of all of these studies is that the intracellular distribution of mammalian proteins is not homogenous, in contrast to our findings that the endogenous source proteins for the MHC II bound peptides identified on DCs and B cells are comparably localized among different cellular compartments.

Third, pathway analysis (Ingenuity software) of the endogenous MHC II repertoire on splenic DCs and B cells indicates that this repertoire reflects the distinct immune functions of the two cell types. The source proteins for the identified MHC II peptides in splenic DCs and B cells are grouped in distinct networks that characterize different immune functions of DCs vs. B cells, although 40% of these proteins are shared. For DCs, peptides derived from proteins required for antigen presentation and small molecule transport were abundant and consistent with the role of DCs in presenting antigens to T cells and initiating T cell immunity40, 43, 67. In contrast for B cells, many peptides were derived from cell to cell signaling proteins and proteins for DNA recombination and repair, which are required by B cells that distinctively produce antibody and undergo immunoglobulin class switching68–70.

Similar conclusions were reached when the MHC I repertoire was identified in bone marrow DCs and thymocytes66. It was found that cell specific source proteins for 417 peptides identified in DCs and 187 peptides from thymocytes were grouped in networks that characterize their distinct functions in the immune system. Myeloid differentiation, proteosome function and toll-like receptor signaling were the main networks for bone marrow DCs treated with LPS as a maturation stimulus, while in thymocytes, the source proteins were grouped into networks that regulate tight junctions, purine metabolism and the cell cycle.

Comparison of the source proteins for the MHC I peptides identified in bone marrow DCs66 with the source proteins for the MHC II peptides identified in spleen DCs in our study shows that very few of them are shared. Among the shared proteins are ones that have a role in the general maintenance of cellular processes, for example NADH dehydrogenase 1 alpha subcomplex (Ndnfa4), protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 23 (Ptpn23), Cathenin Beta 1 (Ctnnb1), actinin alpha 4 (Actn4), ubiquitin specific peptidase 14 (Usp14) and annexins (annexin A3 and A7 as source proteins for MHC I and annexin 6 for MHC II peptides). This lack of overlap between source proteins for MHC I and MHC II peptide presented on the MHC molecules of bone marrow and spleen DCs in vivo is consistent with the different functions of the MHC I and MHC II molecules in eliciting T cell mediated responses to immune challenges and reinforces conclusions that the source proteins for MHC II and MHC I peptides reflect the distinct roles of DCs and B cells in the immune system.

In summary, our experiments established that it is feasible to use the LC-MS/MS technology to examine a wide repertoire of MHC II peptides in murine splenic DCs. The approach described here can be applied in the future to investigate different aspects of DC biology. In particular, it can be used to identify the specific peptides presented on MHC II molecules on murine splenic DCs during viral infections or other immune interventions and allows for critical interpretation of biological findings based on antigen presentation and T cell responses.

Supplementary Material

MHC II binding motifs of peptides identified from DCs and B cells.

(a) Peptides and corresponding source proteins were identified by MS/MS. Peptides are arranged according to the H2-Ad and H2-Ed binding motif (http://www.syfpeithi.de), indicated by score. Peptides with a score equal to or higher than 20 were regarded as strong binders. Anchor amino acids in position 1, 4, 6 and 9 are in bold.

A list of source proteins for MHC II peptides identified in DCs and B cells grouped in cellular networks by the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis Software (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com) (see Materials and Methods and Legend to Fig. 5).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Howard Hang and John Wilson for helping to launch the project, Drs. Brian Chait, David Fenyo, Beatrix Ueberheide, and Chae Gyu Park for valuable discussions, Susan Powel (Proteomics Resource Center at The Rockefeller University) for purification of the synthetic isotopically labeled peptides, Dr. Nawei Zhang for her help in the late phase of this work. We were supported by grants from NIAID, AI13013 and AI051573 to RMS.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- MHC

Major Histocompability Complex

- DCs

dendritic cell

- Flt3L

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- poly IC

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- MS

mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Supporting Information includes a table and a figure. Table 1S contains the list of predicted single binding frames found in the sequences of identified MHC II peptides that bind to MHC II molecules in spleen murine DCs and B cells in vivo. Fig. 1S shows the complete list of source proteins grouped in the functional networks for DCs and B cells identified by the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis Software (www.ingenuity.com). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://publ.asc.org

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unanue E. Cellular studies on antigen presentation by class II MHC molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90127-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM, Hemmi H. Dendritic cells: translating innate to adaptive immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:17–58. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallusto F, Cella M, Danieli C, Lanzavecchia A. Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility class II compartment: downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J Exp Med. 1995;182:389–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savina A, Amigorena S. Phagocytosis and antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:143–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inaba K, Turley S, Iyoda T, Yamaide F, Shimoyama S, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN, Mellman I, Steinman RM. The formation of immunogenic MHC class II-peptide ligands in lysosomal compartments of dendritic cells is regulated by inflammatory stimuli. J Exp Med. 2000;191:927–936. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inaba K, Turley S, Yamaide F, Iyoda T, Mahnke K, Inaba M, Pack M, Subklewe M, Sauter B, Sheff D, Albert M, Bhardwaj N, Mellman I, Steinman RM. Efficient presentation of phagocytosed cellular fragments on the MHC class II products of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2163–2173. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vascotto F, Le Roux D, Lankar D, Faure-Andre G, Vargas P, Guermonprez P, Lennon-Dumenil AM. Antigen presentation by B lymphocytes: how receptor signaling directs membrane trafficking. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(1):93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelsoe G. Life and death in germinal centers [Redux] Immunity. 1996;4:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Meyer-Hermann M, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell. 2010;143(4):592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dongre AR, Kovats S, deRoos P, McCormack AL, Nakagawa T, Paharkova-Vatchkova V, Eng J, Caldwell H, Yates JR, 3rd, Rudensky AY. In vivo MHC class II presentation of cytosolic proteins revealed by rapid automated tandem mass spectrometry and functional analyses. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(5):1485–94. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1485::AID-IMMU1485>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dengjel J, Schoor O, Fischer R, Reich M, Kraus M, Muller M, Kreymborg K, Altenberend F, Brandenburg J, Kalbacher H, Brock R, Driessen C, Rammensee HG, Stevanovic S. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(22):7922–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501190102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik P, Strominger JL. Perfusion chromatography for very rapid purification of class I and II MHC proteins. J Immunol Methods. 2000;234:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velazquez C, DiPaolo R, Unanue ER. Quantitation of lysozyme peptides bound to class II MHC molecules indicates very large differences in levels of presentation. J Immunol. 2001;166(9):5488–5494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippolis JD, White FM, Marto JA, Luckey CJ, Bullock TN, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. Analysis of MHC class II antigen processing by quantitation of peptides that constitute nested sets. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):5089–5097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudensky AY, Preston-Hurlburt P, Hong SC, Barlow A, Janeway CA., Jr Sequence analysis of peptides bound to MHC class II molecules. Nature. 1991;353:622–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelhard VH. Structure of peptides associated with class I and class II MHC molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:181–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santambrogio L, Strominger JL. The ins and outs of MHC class II proteins in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2006;25(6):857–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alfonso C, Karlsson L. Nonclassical MHC class II molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozzacco L, Trumpfheller C, Huang Y, Longhi MP, Shimeliovich I, Schauer JD, Park CG, Steinman RM. HIV gag protein is efficiently cross-presented when targeted with an antibody towards the DEC-205 receptor in Flt3 ligand-mobilized murine DC. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(1):36–46. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux ER, Lyman SD, Shortman K, McKenna HJ. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: Multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Keeffe M, Hochrein H, Vremec D, Pooley J, Evans R, Woulfe S, Shortman K. Effects of administration of progenipoietin 1, Flt-3 ligand, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and pegylated granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor on dendritic cell subsets in mice. Blood. 2002;99(6):2122–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waskow C, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, Guermonprez P, Ginhoux F, Merad M, Shengelia T, Yao K, Nussenzweig M. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curti A, Fogli M, Ratta M, Tura S, Lemoli RM. Stem cell factor and FLT3-Ligand are strictly required to sustain the long-term expansion of primitive CD34(+)DR(−) dendritic cell precursors. J Immunol. 2001;166:848–854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Amico A, Wu L. The early progenitors of mouse dendritic cells and plasmacytoid predendritic cells are within the bone marrow hemopoietic precursors expressing Flt3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;198(2):305–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, Chu FF, Randolph GJ, Rudensky AY, Nussenzweig MC. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1170540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Tussiwand R, Lanzavecchia A, Manz MG. Activation of the Flt3 signal transduction cascade rescues and enhances type I interferon-producing and dendritic cell development. J Exp Med. 2006;203(1):227–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz V, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, Golumbek P, Levitsky H, Brose K, Jackson V, Hamada H, Pardoll D, Mulligan RC. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulendran B, Lingappa J, Kennedy MK, Smith J, Teepe M, Rudensky A, Maliszewski CR, Maraskovsky E. Developmental pathways of dendritic cells in vivo: distinct function, phenotype, and localization of dendritic cell subsets in FLT3 ligand-treated mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:2222–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang YS, Yamazaki S, Iyoda T, Pack M, Bruening S, Kim JY, Takahara K, Inaba K, Steinman RM, Park CG. SIGN-R1, a novel C-type lectin expressed by marginal zone macrophages in spleen, mediates uptake of the polysaccharide dextran. Int Immunol. 2003;15:177–186. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wellings DA, Atherton E. Standard Fmoc protocols. Methods Enzymol. 1997;289:44–67. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)89043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knorr R, Trzeciak A, Bannwarth W, Gillessen D. New coupling reagents in peptide chemistry. Tetrahedron Ltrs. 1989;30(15):1927–1930. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sole NA, Barany G. Optimization of solid-phase synthesis of [Ala8]-dynorphin A. J Org Chem. 1992;57(20):5399–5403. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardt M, Witkowska HE, Hall SC, Fisher S. Absolute quantitation of targeted endogenous salivary peptides using heavy isotope-labeled internal standards and high-resolution selective reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Thermo Scientific. 2008 Application Note: 451. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:476–483. doi: 10.1038/nri1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Platt CD, Ma JK, Chalouni C, Ebersold M, Bou-Reslan H, Carano RA, Mellman I, Delamarre L. Mature dendritic cells use endocytic receptors to capture and present antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(9):4287–4292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910609107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longhi MP, Trumpfheller C, Idoyaga J, Caskey M, Matos I, Kluger C, Salazar AM, Colonna M, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1589–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JA, Sinkovits RS, Mock D, Rab EL, Cai J, Yang P, Saunders B, Hsueh RC, Choi S, Subramaniam S, Scheuermann RH. Components of the antigen processing and presentation pathway revealed by gene expression microarray analysis following B cell antigen receptor (BCR) stimulation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manickasingham S, Reis e Sousa C. Microbial and T cell-derived stimuli regulate antigen presentation by dendritic cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165(9):5027–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Toll-dependent selection of microbial antigens for presentation by dendritic cells. Nature. 2006;440:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature04596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierre P, Turley SJ, Gatti E, Hull M, Meltzer J, Mirza A, Inaba K, Steinman RM, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of MHC class II transport in mouse dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:787–92. doi: 10.1038/42039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–787. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walseng E, Furuta K, Bosch B, Weih KA, Matsuki Y, Bakke O, Ishido S, Roche PA. Ubiquitination regulates MHC class II-peptide complex retention and degradation in dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(47):20465–20470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010990107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mallick P, Kuster B. Proteomics: a pragmatic perspective. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):695–709. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wahlstrom J, Dengjel J, Persson B, Duyar H, Rammensee HG, Stevanovic S, Eklund A, Weissert R, Grunewald J. Identification of HLA-DR-bound peptides presented by human bronchoalveolar lavage cells in sarcoidosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3576–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI32401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hillen N, Stevanovic S. Contribution of mass spectrometry-based proteomics to immunology. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2006;3(6):653–64. doi: 10.1586/14789450.3.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luber CA, Cox J, Lauterbach H, Fancke B, Selbach M, Tschopp J, Akira S, Wiegand M, Hochrein H, O’Keeffe M, Mann M. Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32(2):279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pereira SR, Faca VM, Gomes GG, Chammas R, Fontes AM, Covas DT, Greene LJ. Changes in the proteomic profile during differentiation and maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells stimulated with granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor/interleukin-4 and lipopolysaccharide. Proteomics. 2005;5(5):1186–98. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Angenieux C, Fricker D, Strub JM, Luche S, Bausinger H, Cazenave JP, Van Dorsselaer A, Hanau D, de la Salle H, Rabilloud T. Gene induction during differentiation of human monocytes into dendritic cells: an integrated study at the RNA and protein levels. Funct Integr Genomics. 2001;1(5):323–9. doi: 10.1007/s101420100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Le Naour F, Hohenkirk L, Grolleau A, Misek DE, Lescure P, Geiger JD, Hanash S, Beretta L. Profiling changes in gene expression during differentiation and maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells using both oligonucleotide microarrays and proteomics. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):17920–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foster LJ, de Hoog CL, Zhang Y, Xie X, Mootha VK, Mann M. A mammalian organelle map by protein correlation profiling. Cell. 2006;125(1):187–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fagerberg L, Stromberg S, El-Obeid A, Gry M, Nilsson K, Uhlen M, Ponten F, Asplund A. Large-Scale Protein Profiling in Human Cell Lines Using Antibody-Based Proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2011 doi: 10.1021/pr200259v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar G, Ranganathan S. Network analysis of human protein location. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11 (Suppl 7):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S7-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50(3–4):213–9. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lovitch SB, Pu Z, Unanue ER. Amino-terminal flanking residues determine the conformation of a peptide-class II MHC complex. J Immunol. 2006;176(5):2958–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fissolo N, Haag S, de Graaf KL, Drews O, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG, Weissert R. Naturally presented peptides on major histocompatibility complex I and II molecules eluted from central nervous system of multiple sclerosis patients. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(9):2090–101. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900001-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chicz RM, Urban RG, Lane WS, Gorga JC, Stern LJ, Vignali DAA, Strominger JL. Predominant naturally processed peptides bound to HLA-DR1 are derived from MHC-related molecules and are heterogeneous in size. Nature. 1992;358:764–768. doi: 10.1038/358764a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suri A, Lovitch SB, Unanue ER. The wide diversity complexity of peptides bound to class II MHC molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Verteuil D, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Granados DP, Fortier MH, Hardy MP, Bramoulle A, Caron E, Vincent K, Mader S, Lemieux S, Thibault P, Perreault C. Deletion of immunoproteasome subunits imprints on the transcriptome and has a broad impact on peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex I molecules. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9(9):2034–47. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900566-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227(1):221–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]