Abstract

The past few decades have witnessed bleak pictures of unhappy physicians worldwide. Japanese physicians working in hospitals are particularly distressed. Today, Japan’s healthcare system is near collapse because physicians are utterly demoralized. Their loss of morale is due to budget constraints, excessive demands, physician shortages, poor distribution, long working hours, hostile media, increasing lawsuits, and violence by patients. Severe cost-saving policies, inadequate distribution of healthcare resources, and the failure to communicate risks has damaged physicians’ morale and created conflicts between physicians and society. Physicians should communicate the uncertainty, limitations, and risks of modern medicine to all members of society. No resolution can be achieved unless trust exists between physicians, patients, the public, the media, bureaucrats, politicians and jurists.

Keywords: physician’s morale, physician shortages, overwork, health policy

Introduction

The past few decades have witnessed a loss in physicians’ autonomy, their dwindling prestige, and a deep professional malaise in many advanced nations, including the United Kingdom,1–3 the United States,4 Canada,5 and Australia.6 Many physicians encounter frustration and feel discontented with their professional lives. Why are they so unhappy? A UK report in 2001 pointed out that the woes of physicians in the UK were linked to multiple factors, including poor support, overwork, and excessive patient requirements.1 The report elicited an enormous number of responses worldwide, all of which shared a theme of physician unhappiness. A US report indicated that the dissatisfaction of US physicians was caused by constraints imposed by Managed Care, a malpractice crisis, a disparity in expectations between physicians and patients, a lack of time for routine work, and the imposition of many nonmedical roles for which physicians were never trained.4 A number of reports have discussed other possible reasons.2,3,5,6 An expanding volume of empirical data and anecdotes, although not scientific, supports this view.

In Japan, the grievances of physicians seem immensely more serious than those in Western nations. Japan’s healthcare system is on the verge of collapse because Japanese physicians are utterly demoralized.

In this report, we describe the possible causes of this demoralization: the imbalance between the supply and demand of healthcare services, poor governmental support, overwork, hostile media, increasing lawsuits and violence by patients. In addition, we discuss needed policy changes, which could possibly be applied to any country.

Facts related to physicians’ unhappiness

Fact 1: Budget constraint

Public healthcare services in Japan are provided on the basis of nationwide coverage of health insurance. Healthcare costs are paid with both taxes and insurance premiums. The development of healthcare technologies and an aging society place a growing burden on the healthcare system, one of the major political issues in Japan.

Since the collapse of the bubble economy in 1989, Japan has suffered a long-term recession. The Japanese government is attempting to ease financial deficit by austere budgeting; the healthcare system is thus subject to severe cost-saving policies.

The 2008 report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) indicated that the total health expenditure (THP) per Gross Domestic Products was 8.2% in Japan, which was the lowest in G7 countries: 8.4% in the United Kingdom; 8.7% in Italy; 10.0% in Canada; 10.6% in Germany; 11.1% in France; and 15.3% in the United States. THP per capita was lower in Japan (2,474 USD) than that in Italy (2,614 USD), the United Kingdom (2,760 USD), Germany (3,371 USD), France (3,449 USD), Canada (3,687 USD) or the United States (6,714 USD).7

Fact 2: Physician shortage

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) believes that an excessive number of physicians will swell healthcare costs, based on the so-called ‘physician-induced demand’ theory.8 It has been reluctant to increase human resources, despite the increasing demand for medical care.

As of 2006, there were 277,927 physicians in Japan.9 According to the OECD health data 2008, the number of practicing physicians per 1,000 people was 2.1 in Japan, making it 27th among the 30 OECD industrialized countries.7

Today, the shortage of physicians is apparent, especially in rural areas. Regional disparity in physician density is an unsolved problem in Japan.10 As of 2006, the number of practicing physicians per 1,000 was 2.65 in Tokyo, in contrast to 1.70 to 1.96 in the six prefectures of Tohoku, a northern area of Japan.9

With regard to specialty, there is a distinct shortage of obstetricians, pediatricians, emergency physicians, and surgeons. In particular, the shortage of obstetricians has resulted in dysfunctional child-delivery services. According to the MHLW data, many maternity wards have been closed,11 and pregnant women are forced to commute long distances to find a maternity ward. This situation has already taken its toll. In August 2007 in Nara, a western prefecture of Japan, a 38-year-old pregnant woman miscarried in an ambulance after being sent from hospital to hospital. Obstetric centers reportedly could not accept her due to a shortage of physicians.12

Fact 3: Excessive demands

Japanese healthcare services are characterized as ‘free access’ and ‘affordable’. A large number of hospitals and beds, long stays in hospital, numerous outpatient clinic visits, a vast number of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scanners are unique characteristics of the Japanese healthcare system.13

There is an increasing demand for medical services, with fewer human resources available to meet it. For example, the number of surgeries, endoscopic treatments, and endovascular interventions is increasing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Increase in the number of several treatments11

| Nov 2005 | Nov 1996 | |

|---|---|---|

| All surgeries under general anesthesia | 167,744 | 128,086 |

| Craniotomy | 6,463 | 6,315 |

| Cardiac surgery with caridiopulmonary bypass | 3,689 | 2,814 |

| Malignant tumour resection | 36,569 | 30,605 |

| Total arthroplasty | 6,987 | 5,561 |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 12,027 | 6,976 |

| Endoscopic treatment of digestive tract diseases | 41,669 | 22,693 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 11,249 | 5,818 |

Emergency centers also have difficulty in accepting large numbers of patients. In 2007, among 368,226 patients with severe disease or injury who were sent to emergency hospitals by ambulance, 58,996 (16%) patients were rejected by at least one hospital. The number of hospitals to which the ambulance attendants referred the patient was ≥4 in 14,387 (3.9%) cases, ≥6 in 5,398 (1.5%) cases, or ≥11 in 1,074 (0.3%) cases.14 Mainstream media reported that many hospitals “played hot potato” with ambulances. The reality is that they were forced to send patients elsewhere because there were too few physicians.

Fact 4: Low efficiency of physician distribution

In Japan, physicians are classified into full-time hospital employed physicians, private practice physicians and others. As of 2006, there were 168,337 hospital physicians and 95,213 private-practice physicians. Note that both groups are specialists. Until 2004, there was no education program to train generalists or family physicians in Japan. Almost all graduates start their careers as hospital physicians and experience hospital work as specialists for over 10 years. Hospital physicians must see outpatients for both primary and secondary care at the outpatients’ clinic in the hospital. Many of them, after retiring from work as a hospital physician, become private-practice physicians. Private-practice physicians only see primary-care patients in their own specialties: obstetric private practice physicians only see pregnant women, while pediatric private-practice physicians only see children.

According to a survey conducted in 2005 by the Japan Pediatric Association, 61% of hospital pediatricians’ working time is devoted to primary care. For the 127 million people in Japan, the number of hospitals with pediatrics departments is about 3,500 and the average number of pediatricians per hospital is only 2.4. The percentage of hospitals with three pediatricians or less is about 63%, and the percentage of hospitals with fewer than 20 pediatric beds is about 60%.15 This poor physician distribution increases the workload on individual physicians.

Fact 5: Long working hours

Increasing demands in conjunction with manpower shortages have resulted in overworked physicians. A survey indicated that the average working hours per week among hospital physicians in their twenties, thirties and forties were 74.9, 68.4, and 64.5 hours, respectively.16

Like many Japanese businessmen, Japanese physicians seem to be workaholics. Karoshi is a Japanese word that means “death due to overwork”, while karojisatsu indicates “suicide due to overwork”. Overwork combined with low job control and poor social support can cause sudden death from ischemic heart or cerebrovascular disease, as well as severe mental disorders including depression and burnout syndrome resulting in suicide.17 Criterion of karoshi according to the government is simple. Sudden death of any employee who works an average of 65 hours per week or more for more than 4 weeks or 60 hours or more per week for more than 8 weeks is defined as karoshi.17 In fact, the average working hours of many hospital physicians are far more than 65 hours per week.

Physician karoshi or karojisatsu cases are being seen across Japan. Six physician deaths were attributed to overwork and work-related stress under the Worker’s Accident Compensation Insurance System in 2007.18 These figures might be just the tip of the iceberg; there may be more victims behind the scenes.

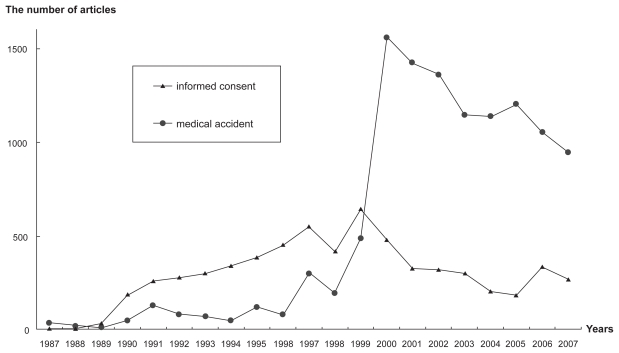

Fact 6: Hostile media

In Japan, until the 1980s, the relationship between physicians and patients was characterised as paternal. The concept of patient autonomy was imported to Japan in the late 1980s from western nations. The term ‘informed consent’ became a key word in Japanese society. Figure 1 shows the number of newspaper reports on ‘informed consent’ presented in the five major Japanese national newspapers: The Yomiuri, The Asahi, The Mainichi, The Nikkei, and The Sankei. The number gradually increased during 1990s.

Figure 1.

Number of newspaper reports regarding ‘informed consent’ and ‘medical accidents’.

Figure 1 also shows the number of newspaper reports describing ‘medical accidents’, which rapidly increased from 1999 and reached a peak in 2000. In fact, two appalling malpractice cases in 1999 definitely changed the media’s attitude toward the medical profession. In February, a nurse at Tokyo Metropolitan Hiroo Hospital mistakenly injected the disinfectant chlorhexidine into a 58-year-old female patient instead of a drug. The patient died of acute heart failure immediately after the injection.19 In June, at Yokohama City University Hospital, a 74-year-old male with cardiac valve disease was confused with an 84-year-old male with lung cancer due to a mix-up in the surgical centre. The former underwent lung resection, while the latter underwent mitral valve plasty.20 These two cases made shocking headlines. The media’s arguments were hostile, with a sense of indignation and injustice. The media claimed that there must be many doctors committing malpractice in society.

Fact 7: Increasing lawsuits

Japan is not a litigious society. Most troubles are settled out of court. Nevertheless, the number of civil lawsuits related to medical accidents is increasing. According to Supreme Court data, the number doubled from 527 in 1997 to 1,139 in 2006.21 Fear of litigation causes defensive medicine,22 and may influence a physician’s decision to cease medical practice.23

Furthermore, the number of criminal prosecution against physicians has been increasing in Japan. Hiyama and colleagues reported that the number of criminal prosecutions against physicians for the death or injury of a patient was 5 or less per year before 2000 but 17 physicians were prosecuted in 2003.24 They discussed that such an increase reflected the general publics’ growing concern about medical errors and an expectation that the police should take a major role in assuring medical safety in Japan. However, the Japanese police force does not have much medical expertise or knowledge about medical practice. For the police, it is very hard to discern error from an unavoidable complication. For physicians, it is an unacceptable situation where police decide the extent of a crime concerning medical accidents. Introducing a third-party peer review system is a controversial subject in Japan, like the coroner or medical examiner systems in the US and UK.

Fact 8: Violence by patients

Patient rights, in their original meaning, include disclosure of information, participation in decision-making about treatment, respect, confidentiality of health information, and avenues for complaints and appeals.25 Apparently, in Japan, the concept of patient rights has been misunderstood, with an emphasis on “complaints and appeals.”

Today, conflicts between physicians and patients are widespread. Japanese hospital physicians are overwhelmed by patients’ excessive and sometimes unfair complaints and appeals. Failure of communication sometimes results in violence by patients. A nationwide survey conducted by All Japan Hospital Association revealed that 6,882 cases of patient violence, including physical violence and abusive language, occurred in 576 hospitals in 2007.26 A survey by Tokyo Metropolitan Hospitals Association found that 2,674 cases of patient violence occurred in 133 hospitals in Tokyo in 2006, and 273 medical workers left hospitals as a result.27 Another survey in 2007 revealed that 140 of 485 physicians (29%) had experienced abusive language or physical violence from patients in the last six months.28

Discussion

Catastrophic collapse of morale

Long-term budget constraints have gradually increased the imbalance of supply and demand in the healthcare system. Advancements of medical technologies and an aging society are not the only causes for the increase in healthcare demands. Excessive patient requirements are the fundamental cause, increasing hospital physicians’ daily work and stress.

In the past, physicians were considered to be on the same level as clergy in Japan. Patients used to be very grateful to physicians. Today, they are regarded more negatively, and patients are very critical. Physicians are overwhelmed by the excessive, unreasonable complaints of patients. Some patients and their families abuse physicians with language and violence. The relationship between physician and patient is more adversarial than it used to be, evidenced by the increasing amounts of bad press, lawsuits and violence.

Physicians have a great deal of passion and pride. In spite of manpower shortages, they have managed to accomplish their duties by working longer. A strong sense of duty and responsibility are the driving force behind their hard work. Most of them have endured a heavy workload without complaint, not for money, but for the benefit of patients.

However, the work situation has deteriorated during over the last decade. Physicians feel undervalued in spite of the sacrifices and contributions they make. The current demands and stresses have become intolerable, resulting in a catastrophic collapse in pride and morale. This, combined with exhaustion, is having a harmful effect on the quality of healthcare. Demoralized physicians are more likely to leave the profession. Dissatisfaction, if prolonged, results in health problems for the physicians themselves.

What has made the situation worse?

The fundamental cause of patients’ loss of trust in physicians is the mass media’s sensational coverage of medical accidents. The two malpractice cases in 1999 were a watershed. Since then, the media has been on a witch-hunt, casting suspicion on any unexpected death. Physicians are under media scrutiny. Sentimental reports on victims of medical accidents amplify people’s distrust in physicians.

Around the year 2000, the Japanese medical profession drastically reformed the risk-management system. Despite budget constraints, they have made every effort to establish a safe system, such as the employment of more nurses, new medical safety equipment, innovation of healthcare information technology, and establishment of safety education programs for medical workers.

An error-prevention strategy is essential, but it has not necessarily improved the physician-patient relationship. The problem is that the medical profession has failed to explain the limitations of medical care to patients and the media. They need to explain the probability that adverse events will occur, that safety is never guaranteed and many adverse events are unpreventable. Instead, they have frantically offered empty promises, saying, “We can offer patients safe and high-quality medical service.” Physicians have given patients a fictitious pledge that will certainly result in dishonor.

As a result, patients have been encouraged to expect enhanced services. They feel entitled to perfect safety and a complete cure. They unrealistically expect modern medicine to solve all their physical and psychological problems.

Possible solutions

The failings of the healthcare system in Japan presented here can occur in any country. Practical strategies should be implemented to improve the plight of physicians. In the UK, several reports suggest that the compact between physicians and patients should be redrafted into something more realistic. 1 Rewriting of the old and implicit compact into a new and explicit one seems necessary.3 However, for the severe problems now plaguing Japan, the following comprehensive measures are needed: (i) refining cost-saving policies, (ii) optimizing the distribution of healthcare resources, and (iii) enhancing the “honesty” policy.

Refining cost-saving policies

The Japanese government has imposed a tight reign on healthcare expenditures without regard for physicians’ health. The policy that restricts the number of physicians has severely worsened working conditions for hospital physicians. Such a situation has gradually been recognized by the public. Media reports on the crisis related to physician shortages have recently rapidly increased. The MHLW responded positively to the media coverage and decided to loosen the policy restricting the number of physicians. It proposed increasing the medical student quota, now at about 7,900, back to its past peak of about 8,300.29

This response appears appropriate, but several problems remain unsolved. First, it will take long time to obtain any actual effect from this policy. The ongoing problem of lopsided distribution, including the shortages of obstetricians, pediatricians, surgeons and emergency physicians cannot be resolved with this policy. Urgent measures such as direct financial support for these departments should be implemented. Second, the current policy is not based on a strict evaluation of increasing demands as a result of an aging society, the geographical distribution of Japan’s population, and the increasing availability of advanced technologies. The requisite supply of physicians should be continuously reviewed to satisfy increasing healthcare demands. Finally, and most importantly, the government must assure finance for the implementation and maintenance of this policy.

Optimizing the distribution of healthcare resources

It is especially necessary in Japan to divide the roles of hospitals and clinics. In Japan, free access to any hospital or clinic is guaranteed. Patients frequently visit multiple medical institutions. OECD health data 2008 showed that the number of doctor consultations per capita per year was very high in Japan (13.7) compared with US (4.0), UK (5.1), France (6.4), or Germany (7.0).7 The free access system causes an oversupply of healthcare resources including duplicative medications.30 Another critical issue is that hospital physicians must devote energy to primary care for what are really just mild cases. Restricting free access and introducing a gatekeeper system that utilizes private practice physicians should be considered in Japan.

Enhancing “honesty” policy

Finally, and most importantly, honesty is the best policy. Physicians should honestly confess the following realities: (1) that medical science is not necessarily scientific enough; (2) that medical care is uncertain; (3) that most diseases are unpreventable, incurable, and irreversible; and (4) that safety comes first, but is never guaranteed. Neither safety nor effectiveness should be overemphasized. Uncertainty, limitations, and risks should be emphasized.

The media’s misunderstanding of the uncertainty in medicine has caused friction between patients and physicians, particularly in Japan. People are naive and are susceptible to mass media reports. A lack of media literacy has caused confusion and anxiety among people. Medical professionals have failed to communicate the risks to patients, making the ensuing catastrophic situation unavoidable. They have brought it upon themselves.

Physicians should open the media’s eyes to the reality that there are many patient problems which modern medicine cannot solve, and that sometimes does more harm than good. Physicians should help their patients to accept that diseases are daily problems, and that most deaths from disease are unavoidable. They should also tell their patients not to overestimate physicians’ skill and professional expertise. No physician has God’s hand.

Unless this is successfully communicated, physicians will not be able to establish a partnership with society based on mutual trust. No agreement can be made unless physicians, patients, the public, the media, bureaucrats, politicians and jurists can trust each other.

Acknowledgment

I thank Tomoko Kodama and Naoya Obana for offering data on Figure 1. The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Smith R. Why are doctors so unhappy? There are probably many causes, some of them deep. BMJ. 2001;322:1073–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards N, Kornacki MJ, Silversin J. Unhappy doctors: what are the causes and what can be done? BMJ. 2002;324:835–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ham C, Alberti KGMM. The medical profession, the public, and the government. BMJ. 2002;324:838–42. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuger A. Dissatisfaction with medical practice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:69–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr031703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spurgeon D. Medicine, the unhappy profession? CMAJ. 2003;168:751–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew M, Williams A. Australian general practitioners: desperately seeking satisfaction: is the satisfied GP an oxymoron? Med J Aust. 2001;175:85–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OECD Health Data 2008: Statistics and indicators for 30 countries. Cited 2008 Oct 2. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/health/healthdata.

- 8.Rice TH. The impact of changing medicare reimbursement rates on physician-induced demand. Med Care. 1983;21:803–15. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics and Information Department, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists, 2006 [In Japanese] Cited 2008 Oct 2. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/ishi/06/index.html.

- 10.Kobayashi Y, Takaki H. Geographic distribution of physicians in Japan. Lancet. 1992;340:1391–3. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics and Information Department, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Survey on medical institutions 2005 [In Japanese] Cited 2008 Oct 2. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/05/index.html.

- 12.Anonymous. Miscarriage jolts Japan to address doctor shortage. Reuters. Cited 2007 Aug 30. Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUST296589.

- 13.Nomura H, Nakayama T. The Japanese healthcare system. BMJ. 2005;331:648–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7518.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fire and Disaster Management Agency. A survey on patient acceptance of medical institutions in ambulance services [In Japanese] 2008 March 11. Available from: http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/houdou/200311/200311-3houdou.pdf.

- 15.Fujimura M. Current status of pediatric medicine in Japan and a reform bill. Nihon Ishikai Zasshi [In Japanese] Japan Med Assoc J. 2007;136:1312–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Policy Bureau, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Report of the investigative commission on the demand and supply for physicians [In Japanese] Cited 2006 July 28. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2006/07/dl/s0728-9c.pdf.

- 17.Hiyama T, Yoshihara M. New occupational threats to Japanese physicians: karoshi (death due to overwork) and karojisatsu (suicide due to overwork) Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:428–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.037473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Six physicians’ karoshi occurred this year. The Yomiuri [In Japanese] Cited 2007 Dec 13. Available from: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/iryou/news/iryou_news/20071213-OYT8T00081.htm.

- 19.Anonymous. Fatal IV drip spurs malpractice probe in Hiroo. The Japan Times. Cited 1999 March 16Available from: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn19990316a4.html.

- 20.Anonymous. Court fines medical staff for heart, lung mix-up. The Japan Times. Cited 2001 Sept 21. Available from: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20010921a3.html.

- 21.The Supreme Court. Numbers of settled lawsuits regarding medical affairs. 2006. [In Japanese]. Cited 2008 Oct 2.Available from: http://www.courts.go.jp/saikosai/about/iinkai/izikankei/toukei_04.html.

- 22.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293:2609–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruse J, Phillips D, Wesley RM. Factors influencing changes in obstetric care provided by family physicians: a national study. J Fam Pract. 1989;28:597–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiyama T, Yoshihara M, Tanaka S, Chayama K. The number of criminal prosecutions against physicians due to medical negligence is on the rise in Japan. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:105–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Hospital Association, Management Advisory. A Patient’s Bill of Rights. 1973. Cited 2008 Oct 2. Available from: http://www.patienttalk.info/AHA-Patient_Bill_of_Rights.htm.

- 26.All Japan Hospital Association. A survey of medical institutions on their risk management systems for patients’ violence [In Japanese] Cited 2008 April 21. Available from: http://www.ajha.or.jp/about_us/activity/zen/080422.pdf.

- 27.Anonymous. 273 hospital workers resigned due to patient violence. The Yomiuri. [In Japanese]. Cited 2008 June 7. Available from: http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/iryou/news/iryou_news/20080607-OYT8T00382.htm.

- 28.Wada K, Yoshida K, Sato E. The situation of patient violence and the measurement of it [In Japanese] Nihon Iji Shinpo. 2007;4354:81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anonymous. Higher medical student quotas. The Japan Times. Cited 2008 Sept 2. Available from: http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/ed20080902a1.html.

- 30.Kinoshita H, Kobayashi Y, Fukuda T. Duplicative medications in patients who visit multiple medical institutions among the insured of a corporate health insurance society in Japan. Health Policy. 2008;85:114–23. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]