Abstract

The current phase of globalization represents a “double-edged sword” challenge facing public health practitioners and health policy makers. The first “edge” throws light on two constructs in the field of public health: global health (formerly international health) and globalized public health. The second “edge” is that of global governance, and raises the question, “how can we construct public health regulations that adequately respond to both global and local complexities related to the two constructs mentioned earlier (global health and globalized public health)?” The two constructs call for the development of norms that will assure sustained population-wide health improvement and these two constructs have their own conceptual tools and theoretical models that permit a better understanding of them. In this paper, we introduce the “globalized public health” construct and we present an interactive comprehensive framework for critically analyzing contemporary globalization’s influences on the field of public health. “Globalized public health”, simultaneously a theoretical model and a conceptual framework, concerns the transformation of the field of public health in the sociohistorical context of globalization. The model is the fruit of an original theoretical research study conducted from 2005 to 2008 (“contextualized research,” Gibbons’ Mode II of knowledge production), founded on a QUAL-quant sequential mixed-method design. This research also reflects our political and ideological position, fuelled with aspirations of social democracy and cosmopolitical values. It is profoundly anchored in the pragmatic approach to globalization, looking to “reconcile” the market and equity. The model offers several features to users: (1) it is transdisciplinary; (2) it is interactive (CD-ROM); (3) it is nonlinear (nonlinear interrelations between the contextual globalization and the field of public health); (4) it is synchronic/diachronic (a double-crossed perspective permits analysis of global social change, the emergence of global agency and the transmutation of the field of public health, in the full complexity of their nonlinear interaction); (5) it offers five characteristics as an auto-eco-organized system of social interactions, or dynamic, nonlinear sociohistorical system. The model features a visual interface (five interrelated figures), a structure of 30 “integrator concepts” that integrates 114 other element-parts via 1,300 hypertext links. The model is both a knowledge translation tool and an interactive heuristic guide designed for practitioners and researchers in public health/community health/population health, as well as for decision-makers at all levels.

Keywords: contemporary globalization, public health, conceptual framework, theoretical model, theory, sociohistorical system, knowledge translation tool, nonlinearity, transdisciplinarity, synchronicity, diachronicity

Globalization and public health: A key issue

“Facing the daunting global context, public health is at a crossroads”1 or as Roy further explains, “Globalization is the crossroads of public health, its mission, and its goals”.2 Beyond the acceptance of the image of a crossroads of the two previous authors, many others agree that the field of public health is currently undergoing a profound crisis.3–10

Health has its historic, cultural, and social foundations, but its public foundations are the most strongly pronounced. Gagnon and Bergeron also insist on this type of transformation in the field of public health in time and space, a transformation that is the result of social and political processes and does not follow any deterministic logic.5 Thus, for the past 25 to 30 years, the field of public health has been influenced by the sociohistorical context of globalization.11

Contemporary globalization,a which can be seen as the prime force behind the rapid economic, political, social, environmental and cultural changes that are transforming the world order and societies, marks the sociohistorical reality of the past quarter century. Driven by the economy and information and communication technologies (ICTs), and closely linked to culture, such a globalization process is without historical precedent in its intensivity and extensivity character (eg, its velocity and impact), which fundamentally distinguish it from previous eras of globalization. Today’s world is one of porous borders, with increasingly transnational interdependencies. The intensification of transnational flows – which can be due to organizations (global corporations, humanitarian or environmental organizations, religious or identity movements) or to the aggregation of individual choices (migratory flows) – marks the failure of the ideal of a world of nation-states, of a world based on the three-pronged principle of authority, sovereignty, and territoriality. Thus, globalization, although not comparable to the end of the state, forces the states of the world to re-think their interventions and capacity for action, notably in the health sector. The nation-state system is no longer the only foundation of global governance; such governance requiring now the recognition of the inter-weaving of global spaces (transnational) and local spaces (national or infranational).

In general, globalization establishes a new local – global dialectic of issues or problems in the day-to-day experience of people. Local fundamental problems that concern people – problems related to health, food, work, safety, environment, investment, etc. – turn into transnational problems. At the same time as this new transnationality of problems, globalization becomes the trigger of conflicts, calling for its framework or the learning of a democratically founded interdependence agreed upon by the different actors (states, international institutions, nongovernment organizations [NGOs], associative groups, private foundations, global corporations) with different interests (public, associative or private interests). In different sectors (health, education, safety, environment), global governance thus takes us to the transnational opening of national policies and the implementation of a global public space that transcends territories.

More specifically, the current phase of globalization confronts the field of research, knowledge and action of public health. By giving rise to inherently global health issues (IGHIs)6 and widening inequalities/inequities in health, contemporary globalization makes a territorialized vision of public health obsolete or incomplete: a (new) “globalized public health” is taking shape, requiring a deeper understanding of the issues and processes at stake and requiring the creation of a global governance for public health.

However, although public health researchers and practitioners recognize the need to conceptualize this new “globalized public health” and better understand the ways in which today’s era of globalization can lead to improved health for all, the linkages between globalization and public health are complex and remain poorly conceptualized.12 On one hand, globalization is a cross-disciplinary and wide-ranging subject, plagued by definitional ambiguity and heated debates. On the other hand, a clear definition of public health is not easy to provide. Moreover, public health is at a turning point of its history and continues to be theoretically under-developed and conceptually under-tooled.1,2,12,13,b So, despite a growing literature on the importance of globalization for health/public health, the concept of “globalized public health” is immature due to a conspicuous lack of theory, and generally speaking, public health practitioners often confuse the meaning of global health and globalized public health.

In this paper, we introduce this “globalized public health” construct and provide an interactive comprehensive framework for critically analyzing contemporary globalization’s influences on public health. The paper is divided into three parts. In the first part, public health is first defined as being a field and presented as a field in crisis in developed societies. We will see why a global context – contemporary globalization – permits us to more clear sociohistorical understanding of this crisis. In the second part, we present a definition and the limitations of this sociohistorical context or process of globalization. We will then see exactly how we can characterize globalization as a “double-edged sword” for public health. The third part includes the principal findings and major conclusions of an original research study conducted in Canada from 2005 to 2008, founded on a mixed-method design. In response to our first research objective, the theoretical model called “globalized public health” is presented, using different figures. In response to our second research objective, we have listed proposals that are incorporated and developed within the model. From this, we then invited public health practitioners to act locally while keeping “globalized public health” in mind. We conclude with a consideration of the usefulness that this model could have for health researchers, professionals, and decision-makers, as either a heuristic strategy or as a knowledge translation tool.

Part 1: Defining public health as a field in crisis in a global context

In what way and how can we claim that public health is a “field”? And what is a “field in crisis in a global context”?

Every man or woman in the street has a rough idea of what public health might be. And yet, a clear definition is not easy to provide, for several possible reasons: (1) the health of a group is harder to define and measure than the health of an individual; (2) health, in a collective sense, is also a social construction; (3) from a scientific point of view, public health is not a discipline; (4) one can see a variety of divergent practical perspectives in public health. The difficulty in defining “public health” could also be explained by the ambiguity of its underlying notions, such as “health”, “well-being”, “illness”, and even “determinant of health”. In addition, the term “public” is ambiguous: does it refer to the State and the opposition public versus private, or does “public” refer to the population in the sense of the opposition between public and individual? As Bibeau and Fortin mention, expressions like public health, new public health, and critical public health are much more than simple cosmetic labels.12 In this paper, we use the term “public health” as a combination of “population health” and the “new public health”, and this combination will be considered as a “field”.

Public health has as yet received scant attention as a field since Gagnon and Bergeron introduced this perspective in 1999.5 More frequently, public health has been studied from the perspective of intervention (health and security at work, environmental health, lifestyles) or from the perspective of a particular problem (suicide, breast cancer). Gagnon and Bergeron invite us to go beyond these organizational, professional, and disciplinary divisions, and to consider public health as a field.5 The notion of field has its roots in Bourdieu, and refers initially to a battleground of opposing forces in a context of the sociology of class. But Gagnon and Bergeron go beyond this conception, to consider a field as the system of interactions between the institutional and individual actors working in the various domains of public health.5 The term “domain” itself refers to a conceptual space-time in which a group of professional and organizational interventions are centered on a particular object or problem. These different domains – infectious diseases, cardiovascular illnesses, cancers, etc. – can be associated with different modes of intervention (for example, prevention, promotion of health, epidemiological surveillance, protection against environmental and infection risks, assessment of health services). Each of these modes is distinguished from the others by a specific type of intervention (for protection against illness, the types of intervention include vaccination, inspection, and epidemiological surveillance; for promotion of health, they would include social marketing, sanitary education, etc.).

We consider public health as a field of knowledge, research, and collective action, a field that is comprised of different domains and different types of intervention: (1) a practice-based field; (2) a transdisciplinary field that supports integrated activities, promotes inter-sectorial partnerships and the development of knowledge and innovations; (3) a field whose practices and policies are ethical and evidence-based. This field has eight essential functions (surveillance, protection, prevention of illness, promotion of health, support for enactment of laws, research, development of professional expertise, evaluation). It is a field for sustained population-wide health improvement which emphasizes the hallmarks of public health practice: (1) the focus on actions and interventions which require collective actions, (2) sustainability, that is the need to embed policies within supportive systems, and (3) the goals of public health: population-wide health improvement, which implies a concern to tackle health inequalities/inequities.

Furthermore, as Massé reminds us, it is a field in constant evolution in which social actors play a determining role.14 The field is as yet insufficiently conceptualized, but is currently being transformed and structured in time and space.3,5,12 The field of public health is indeed a social, cultural, and historical construct. And indeed, today this sociohistorical construct of public health is at a turning point in its history. As previously mentioned, different authors assert that public health is at a crossroads.1–4,11–13 Our opinion is that the field of public health is currently in a profound crisis.11

It’s a crisis that is felt at different levels (micro, meso, and macro) and that is perceived by all public health practitioners, as well as by health care organizations, national institutes of public health, etc. It’s a crisis manifested in multiple, complex ways, in the sense that the interests of those involved are intertwined. It’s a crisis that goes beyond territorial limits in its sociosanitary implications (for example in the propagation of infectious diseases such as AIDS, SARS, H5N1, H1N1, environmental degradation, etc.).6 At the same time, important questions are emerging, directly or indirectly related to public health: the war against increasing poverty, deforestation, shortage of water, disappearance of ecosystems, the adaptation to climate change, the financing of health systems and the quality of health care, bio-terrorism, the brain drain and the shortage of health professionals. And questions like these need the cooperation of several actors and will transform the context of collaboration among those actors in public health.15–18

This crisis also involves increasing inequality in health within and across countries. Another manifestation of the crisis is the emergence of new interdisciplinary fields of knowledge and research in public health, for example the field of knowledge translation research, the field of equity in health, and of healthy public policies.19,20 Finally, global challenges inform the local (territorialized) manifestations of the crisis, as shown by the following Quebec examples: (1) fundamental revisions of university programs in public health that take new global challenges into account (eg, climate change), and the need to produce new programs in response to north – south collaborations; (2) evaluation of the national public health institute and a critical renewal of its vision and missions; (3) an appeal for conceptual innovations with respect to environmental degradation and public health; (4) increasing study of social inequalities in health and of factors related to their construction (inequality of income, of professional status, of social environment, etc.).

Now that we understand that the field of public health is in crisis, and now that we have seen its manifestations, what conceptual context has the necessary tools that can help us “pin down” the crisis, so as to better understand and resolve it? Is it the context of “advanced modernity”?21 Of “reflexive modernity”?22 Of “post-modernism”?23 Is it the “post-industrial” context? If not, which other type of “post” would be the most appropriate: post-work society, post-experience society, post-class society, post-capitalism society, or post-information society?

What context would be the most pertinent? What context would permit, for example, linking SARS, research and development, the increasing problem of obesity, teleradiology, climate change, the challenge of an efficient and equitable public health system, the fear of bio-terrorism, new public – private partnerships, the emergence of interdisciplinary research fields such as knowledge translation, and equity in health, etc.? The context we need is the global context: today’s era of globalization.

Part 2: Public health confronted to the challenge of today’s era of globalization

What do we mean by a “double challenge”, the “two-edged sword” that the global perspective points at the field of public health?

Defining the multifaceted process of globalization

Globalization is a polysemous concept, distinct from concepts and phenomena such as: (1) occidentalism, Westernization, Americanization (worldwide expansion of corporations); (2) internationalization (cross-border growth of economic and political activity); (3) liberalization (free-market strategies); (4) universalization (global convergence around cultural and institutional forms).24 Globalization can be thought of as an anthropomorphic phenomenon of “creative destruction”25 covering the period 1980 to present day, and transcending territorial borders. It is also a process-driven, sociohistorical phenomenon, favoring the growth of economic, political, social or cultural networks between governments, societies, individuals, and currently dominated by a neoliberal philosophy. Globalization, both as a context and as a sociohistorical process, can be conceptualized in a dual synchronic-diachronic perspective (see Table 1).11 The adjective diachronic (from the Greek elements dia “through” and chronos “time”) means “through time” or “over time”. It is opposed to synchronic.c The diachronic perspective examines the historical development of the globalizing process, whereas the synchronic point of view concentrates on the present system of the changing global order.

Table 1.

Contemporary globalization from a synchro-diachronic perspective

|

Synchronicdperspective on globalization = Matrix of meanings, System of social interactions “Global society” = Market society, Risk society, Technoscientific society, Networked and timeless society, Learning society |

|

Forms of globalization(See Footnote # d) (“Forms” = Multiple and varied facets of globalization)

|

|

Globalization logics(See Footnote # d) (“Logic” = Abstract and schematic reasoning that permits an understanding of reality’s complexities)

|

|

Diachronic perspective on globalization The period 1980–2009 is marked by an acceleration of history, seeing phenomena such as the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of neoliberal ideology, a technological revolution, deepening inequalities between North and South, and the spread of pandemies. Despite Fukoyama’s proclamation of the “End of history”, we observe instead new and numerous histories, lived in fast-forward. Above all it’s a time of crisis. The specific crises that have marked the sociohistorical reality of the last quarter-century include:

|

Specific histories that have marked sociohistorical reality during the last quarter-century:

|

Globalization is historically unprecedented because of its velocity (intensive character) and its impact (extensive character). Three eras of globalization occurred before 1980.26 The first began in 1498 with market globalization, triggered by the discovery of America (Columbus), by the opening of the India route (Vasco de Gama), and the circumnavigation of Africa (Dias). This is the epoch when merchant explorers sought profit on other continents. Market globalization ended with the signature of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. The second, capitalist globalization lasted from 1763 to 1883. This was the epoch of the first industrial revolution and of trade with the colonies: England was the center of capitalist production. The third, industrial globalization was born in 1883, with the creation of the first multinational company, the Standard Oil Trust of Rockefeller. This was the epoch of American big business, the epoch of the second industrial revolution, featuring the boom of steel, the arrival of petrol, the introduction of electricity, and the chemical industry. Then came the Depression, the Second World War, and the international Bretton – Woods conference.

Although this new globalizing world – contemporary globalization – plunges its roots in five centuries of globalization and shares certain characteristics with earlier eras of globalization, various organizational features separate the current phase of globalization from previous phases. The changing global order is structured by ICTs, by a global economy, by the development of regional and planetary regulatory systems, and by the appearance of systemic problems at a planetary level (AIDS, money-laundering, mass terrorism, climate change, etc.).27

It should also be mentioned that apart from its concrete and historical existence, globalization: (1) has been discussed in an abundant literature; (2) has several definitions, some of which are contradictory; (3) has inspired varying positions (pro-globalization, anti- and alter-globalization); (4) has a cumulative dynamic history; (5) has different driving forces, types, and collective representations. Finally, some authors find that it is a vague notion of a simple, restrictive phenomenon, while others find that it is a complex, multiform process that is indissociable from global regulation and government (global governance). Global governance changes the rules of the game all over the planet. New actors appear and take their places (NGOs, global corporations, citizens, etc.) while others lose the exclusivity of their power (nation-states). A new global political reality thus appears, conditioned by an increase in the number of international actors and concomitant requirements of order and readjustments.

Today’s era of globalization: A “double-edge sword” for public health

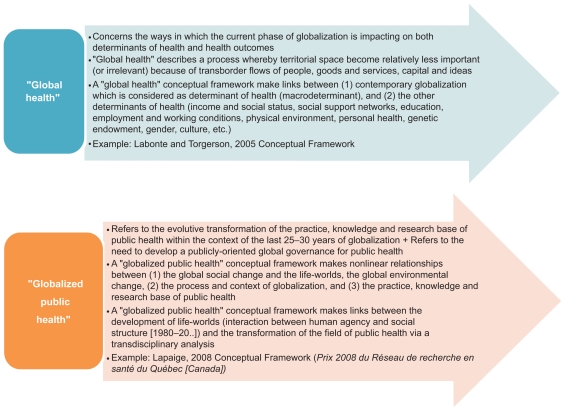

The current phase of globalization represents a “double-edged sword” challenge for public health. The first “edge” is globalization as such: we can study the nature of the connections between public health and globalization, given (1) the appearance of new challenges and the transformation of local challenges into global challenges, (2) varying manifestations of these challenges at the micro, meso, and macro levels. This first “edge” throws light on two constructs in the field of public health: global health (formerly international health) and globalized public health. These two constructs are associated yet distinct both as concepts and as “objects” (see Figure 1). Globalization renders incomplete, if not obsolete, the concept of “international health”. Furthermore, it clearly reveals the inadequacy of a simple territorial vision of public health.

Figure 1.

Today’s era of globalization as a double-edge sword for public health: “Global health” versus “globalized public health.”

These two constructs call for the development of new models of intervention, research, and training, as well as new norms and new theories. More specifically, they call for: (1) the development and implementation of modified, if not radically new types of intervention in public health; (2) the development of conceptual innovations in public health, in its practice, research, and the curriculum of public health training; (3) the development of theoretical and conceptual frameworks that permit: (a) comprehension of the changing field (of research, knowledge, and action) of public health by relating these changes to global social change and to globalization (its manifestations, its forms, its logics, and its imaginative visions), (b) comprehension of how determinants of health are put into play, how globalization affects these determinants, as well as the results and outcomes of health, and finally of the extent to which these outcomes and results of health become globalized.

The second “edge” is that of global regulation, and raises the question “How can we construct public health regulations that adequately respond to both global and local complexities related to the two constructs mentioned earlier (global health and globalized public health)?” The two constructs call for the development of norms that will assure sustainable health for the population. The two constructs have their own conceptual tools and theoretical models that permit a better understanding of them. It is worth noting that the constructs and their models arrive at the same conclusion: it is absolutely necessary to take a stand with respect to the challenges of globalization.

The challenges of globalization related to the crisis in public health can be structured around four general themes (see Table 2). The first theme concerns collective resources and global public goods; the second theme relates to global governance; the third involves action by individual citizens and the fourth theme relates to the emergence of new interdisciplinary fields of research.

Table 2.

Contemporary globalization and public health: Supra-territorialized issues related to the crisis in public health

Theme 1: Global public goods

|

Theme 2: Global governance

|

Theme 3: Social issues and action by individual citizens

|

Theme 4: Burgeoning interdisciplinary fields of research within the field of public health

|

Part 3: A comprehensive framework for analyzing the relationships between public health and today’s era of globalization

This paper is grounded on the results of a Canadian theoretical research study that has lead to the conceptual modeling of inter-relationships between globalization and the field of public health. This research study also included the analysis and production of five recommendations and 16 sub-proposals to set up “globalized public health” policies throughout Canada. This study was considered avant-garde in its theorization of the complex that encompassed the principle of transdisciplinarity. It was considered as a conceptual innovation in terms of public health given its direct and immediate integration into information technologies (Prix du Réseau de recherche en santé du Québec 2008 [RRSPQ 2008 Award]). The theory developed was nonlinear, transdisciplinary, and also interactive, inviting the reader to “travel” within the same theoretical model using hypertext links or following visual representations.

Purpose and setting of the research

To date, in the international literature, there is no interactive and/or transdisciplinary comprehensive framework (a) for analyzing and/or critically assessing the inter-relationship between public health and globalization, on the one hand, and (b) for understanding the dynamics of global governance for public health on the other hand. The major reference work related to the conceptual modelling of the links between globalization and health is that of Woodward and Labonte, and all the frameworks presented in the international literature are related to the global health construct.6,31–36

Our research is situated at the crossroads of two perspectives: (1) knowledge translation research, and (2) critical population health research.19,29 It answers, on the one hand, the need of defining an inter-relational framework between globalization and the field of public health (1) which takes into account the complexity and multireferentiality of these inter-relationships, (2) which at least reflects interdisciplinarity, and (3) which adopts a critical perspective.3,6,9,12,18,34–36 It also responds to the usefulness of this framework as a basis (1) for positioning the potential influence of the different aspects of globalization on the field of public health, while taking into account all the complexity found of their reality, (2) for shaping future research programs, and ultimately (3) for developing national and international policies more favorable to health. By subscribing to production logic of a theoretical understanding of public health in a global context, the proposed model should therefore allow to set up avenues of thought and actions to explore, for the present and the future of public health.

The aim of the study was first to carry out a critical analysis of contemporary globalization in public health and global governance for public health as well as to develop, secondly, a theoretical framework linking globalization and public health.

Our specific research objectives were broken down as follows:

-

Build a conceptual framework/theoretical model that allows to:

Analyze the nature of links between public health and contemporary globalization (synchronistic perspective of the model); and

-

Better understand the transformation of public health during the 1980–2008 period (diachronic perspective of the model).

This means developing a sociohistorical model of globalized public health, which introduces a conceptual coherence between two perspectives (synchronic and diachronic) at the same time that it gives meaning to the evolutionary transformation of public health over the past 25 years.

By taking into account the previous model, propose new avenues of thought and action for global governance for public health.

In this research study, the current phase of globalization was first looked at as a “a transformation process in the world” which consisted of taking the actors as the starting point, and considering the phenomenon of globalization from the perspective of social, organizational, and institutional change. This in turn allowed us to state our second objective from the angle of the stakeholders in the global governance for public health.

Moreover, the proposals were made that took into account our “theoretical sensitivity” (in French: sensibilité théorique), which leads to concomitantly consider the economic process of globalization and the major concerns regarding sustainability and equity. Indeed, following the example of Beck and Held, this work is taking the position of social-democratic and cosmopolitan thought, within which contemporary globalization is an opportunity to re-think the concept universality rather than destroying it.22,27

Lastly, this research is in line with the position of Laïdi, for whom the important thing is to protect the weaker and regulate globalization, and who also confirms that globalization will be what we do with it.37

Complexity, nonlinearity, transdisciplinarity, and synchronicity-diachronicity

This research came from a transdisciplinary perspectivec and was affiliated with complex thinking and nonlinear thinking.38,39 More closely, our research is based on socioanthropological thought, which in particular, from a methodological perspective, enabled our research to take on a double synchronic and diachronic dimension, and subsequently choose a given period, eg, the one covering the past 25–30 years (1980–2008).

The model is the fruit of an original theoretical research study conducted from 2005 to 2008 (“contextualized research”; Gibbons’ Mode II of knowledge production), founded on a QUAL-quantd sequential mixed-method design (qualitative research with “qualitative analysis in writing mode” by Paille and Mucchielli, followed by a systematic review of the literature on knowledge translation and public health (2007–2008) so as to transform the model into a knowledge translation tool).40

Principal findings and major conclusions

Public health – socially, culturally, and historically constructed – has been going through a major crisis over the past two to three decades. This crisis was the point of departure for our questioning. In order to answer to the four research questionse underlying our study, we have chosen the new globalizing world, eg, the multifaceted process of globalization, as a contextual target. We then developed, analyzed and operationalized a certain number of integrator concepts that have allowed us to theoretically understand the social and historical reality of the past quarter century, this reality corresponding to the crisis developing in public health being placed in its context.

Responding to our primary research objective: A theoretical model called “globalized public health”

This section contains three figures, presented in succession (Figures 2, 3, and 4), which, taken together, allow for a theoretical understanding of public health in the global context.

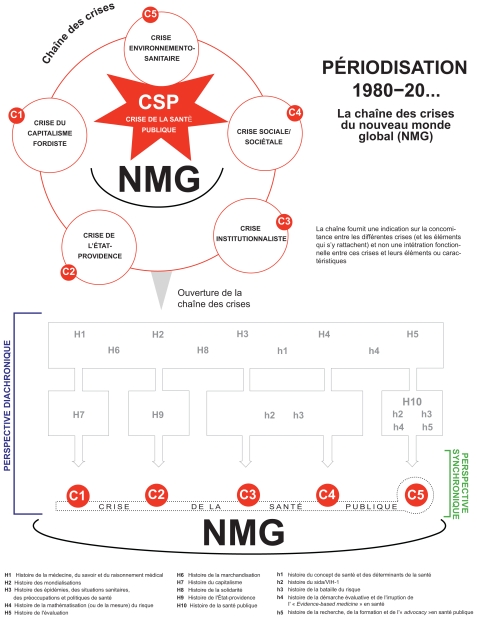

Figure 2.

1980–2008: The series of crises for the new globalizing world (In French: La chaîne des crises du nouveau monde global [NMG]).

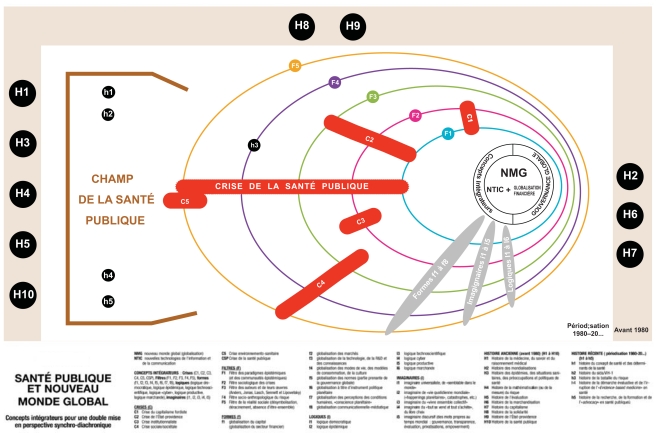

Figure 3.

Public health and the new globalizing world: The integrator concepts for a double synchro-diachronic perspective of their inter-relationships (in French: Santé publique et nouveau monde global – Concepts intégrateurs pour une double mise en perspective synchro-diachronique).

Notes: French – English translation: Champ de la santé publique = The field of public health; Crise de la santé publique = The crisis of public health; NMG-Nouveau monde global = The new globalizing world, Contemporary globalization; NTIC = ICTs; Concepts intégrateurs = The integrator concepts; Globalisation financière = Soft capitalism, Global capitalism; Gouvernance globale = Global governance; Formes f1 à f8 = The forms of globalization [from f1 to f8]; Imaginaires i1 à i5 = The globalization-related imaginations [from i1 to i5]; Logiques l1 à l6 = The logics of globalization [from l1 to l6]; Périodisation 1980–20… = Period 1980–20…; Avant 1980 = Before 1980.

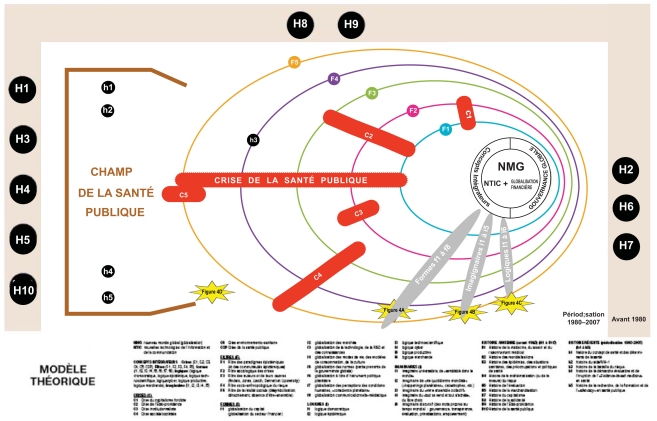

Figure 4.

Theoretical model (in French: Modèle théorique).

The first two figures (Figure 2 and Figure 3) are in “paper format” and did not as such involve the theoretical model. They only prepare the reader for the model’s double synchronic – diachronic dimension. The third and final figure (Figure 4) corresponds to the figurative gateway of the model on CD-ROM. Indeed, our theoretical model does not exist in paper format. The sociohistorical model of globalized public health that meets our research objectives is an interactive digital model on digital optical disk. It corresponds to a nonlinear system supported by a visual representation (five inter-related figures), a synchronic framework of 30 integrator concepts, incorporating 114 other element-parts, via more than 1,300 hypertext links. However, even if the model is interactive and cannot be transposed in paper format, we refer to it in this article as Figure 4.

Figure 2, the first of three figures is entitled “1980–2008: The series of crises for the new globalizing world” and figuratively brings the reader to the beginning of questioning by the author and the point of departure of the research: the transmutation of public health during the 1980–2008 period may be compared with the many signs of globalization, since the public health crisis can be seen as another “link” to be added to the chain made up of five other connected crises relating to the same period.

The “chain” of crises (C) (in French: Chaîne des crises) for the new globalizing world (French acronym in the Figure 2: NMG-Nouveau monde global) represented in Figure 2 include six crises identified as follows:

C1: Crisis of Fordist capitalism

C2: Crisis of welfare state

C3: Institutional crisis

C4: Social/societal crisis

C5: Health – environmental crisis

PHC (in French: CSP-Crise de la santé publique): Public health crisis.

Figure 2 can be looked at in two phases: first of all, five of the six crises are linked in a chain (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5), with the public health crisis (PHC; in French CSP) attaching to C5. Within this inward-looking chain appears – under the French acronym of NMG (Nouveau monde global) – the new globalizing world.

In a second phase, using images, we look at the opening of the crisis chain (see Figure 2). Secondly, the opening of this crisis chain will enable us to “enter”, as it were, into the actual modelling in Figure 4 (via Figure 3). Why? Because this opening of the chain enables us to look at the different crises from a diachronic perspective, eg, to relate the crises with various Histories and histories (so-called ancient histories and recent histories). From then on, we gain a double perspective, eg, diachronic (socio-anthropohistorical) and synchronic, with these two perspectives referring to research objectives 1.b. (which was to better understand the transformation of public health during the period of 1980–2008) and 1.a. (which was to analyze the nature of the links between public health and the new globalizing world) respectively.

In Figure 2, the different Histories from ancient history (eg, which, in our research, goes beyond the period of 1980–2008, or back before 1980) are referred to as follows:

H1: History of medicine, medical knowledge and reasoning

H2: History of globalization (different eras of globalization)

H3: History of epidemics, health situations, concerns and politics around health

H4: History of mathematization (or measurement) of risk

H5: History of evaluation

H6: History of mercantilism

H7: History of capitalism

H8: History of solidarity

H9: History of the welfare state

H10: History of professionalization in public health.

Other histories are part of recent history, which, in our research, covers the period of 1980–2008. These histories come from the sociohistorical reality of the last quarter century, and are identified as follows:

h1: History of the concept of health and health determinants

h2: History of HIV-1/AIDS

h3: History of the fight against risk

h4: History of the evaluative process and sudden emergence of evidence-based medicine/practice in health sciences

h5: History of research, training and advocacy in public health.

When examining the second phase in Figure 2, we can see that the public health crisis (represented by the dotted line) encompasses C5 and is hand in glove with the four other crises – C1, C2, C3, and C4 (the precise nature of these links appear more explicitly in Figure 4). We can also see that C1 is related above all to H7, but also to H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, h1 and h4 (whose Histories/histories are linked to all crises in the figure). Crisis C2 is linked especially to H9, but also H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, h1 and h4; crises C3 and C4 are especially linked to h2 and h3, but also to H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, h1 and h4. Lastly, crises C5 and PHC are linked above all to H10, h2, h3, h4, h5, but also to H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H8, h1 and h4.

The six crises initially presented in Figure 2 will re-appear in the following figure (Figure 3) as integrator concepts (along with other integrator concepts). Through these integrator concepts, an analytical framework focuses, on the one hand, on the inter-relationship between public health and globalization, and, on the other hand, on the dynamics of global governance for public health. Figure 3 with its integrator concepts therefore prepares the reader for understanding the model in Figure 4.

Figure 3, entitled “Public health and the new globalizing world”: The integrator concepts for a double synchro-diachronic perspective of their inter-relationships” proposes the following integrator concepts, which are made up of crises (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, PHC), filters (F1, F2, F3, F4, F5), forms of globalization (f1, f2, f3, f4, f5, f6, f7, f8), logics of globalization (dromocratic logic, epidemic logic, technoscientific logic, cyber logic, productive logic, market logic) and imaginations related to globalization (i1, i2, i3, i4, i5) (see Figure 3).

The crises in Figure 3 (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, PHC) are the same as those that appear in the Figure 2.

The filters (F) are identified as follows:

F1: Filter of epistemic paradigms (and epistemic communities)

F2: Sociological filter of crises (Habermassian crisis of the social state; Freitagian crisis of normativity, Dubarian crisis of identities; ethico – politcal crisis according to Beauchemin)

F3: Filter of authors and their works (Anders and the hiatus between producing and representing; Jonas and the responsibility principle; Lasch, Sennett, and Lipovetsky and the rise of new individualism in the West)

F4: Socioanthropological filter of risk (Beck’s risk society, era of risk and uncertainty)

F5: Filter of social reality (desymbolization, absence of the being-togetherness [être-ensemble]).

The forms (f) appear as follows:

f1: Globalization of capital

f2: Globalization of markets

f3: Globalization of technology, research and development, and knowledge

f4: Globalization of ways of life, consumer models, culture

f5: Globalization of standards (participant in global governance)

f6: Globalization as a planetary political instrument

f7: Globalization of perceptions of human conditions, planetary consciousness

f8: Communication-media globalization.

The logics (l) are presented as follows (the first three logics appear in the periphery of the sociohistorical process of the new global-izing word, whereas the last three form the heart):

l1: Dromocratic logic

l2: Epidemic logic

l3: Technoscientific logic

l4: Cyber logic

l5: Productive logic

l6: Mercantilist logic

Lastly, imaginations (i) appear as follows:

i1: Universalist imagination, a “similar” imagination in the world

i2: Imagination of the “world’s daily life” (“planetary happenings, catastrophes, etc.)

i3: Imagination of “living together collectively”

i4: Imagination of “everything can be bought and sold”, of free choice

i5: Discursive imagination (words that are specific to world time: governance, privatization, social risk).

And together, all these integrator concepts that are crises, filters, forms, logics, imaginations – implemented figuratively in Figure 3, will reappear, but this time inter-related with each other and other elements once the reader opens Figure 4, found on the CD-ROM.

The CD-ROM or Figure 4: Brief presentation

Figure 4, entitled Theoretical Model, appears on CD-ROM. Figure 4 includes four figures: Figures 4A, 4B, 4C, and 4D. These figures can be activated by clicking their respective name (viewed in Figure 4 as yellow stars). Figure 4A is entitled Histories and Forms of Globalization; Figure 4B is entitled Imaginations and New Public Health; Figure 4C is called Logics and Societies; and Figure 4D is entitled Globalized Public Health (see Figure 4).

For each term or meaning found in the five figures (Figures 4, 4A, 4B, 4C, 4D), as for each of the aforementioned integrator concepts, hypertext links (approximately 1,300) were created. By facilitating multireferential6 analysis, these links let us situate analytically/contextually the clicked elements or terms to link them to the others. As well, the propositions related to global governance in public health, although discussed hereafter, are an integral part of Figure 4D.

Figure 4: A nonlinear, interactive and transdiscipinary theory

The purpose of our research was first to carry out a critical analysis on the globalization of public health and global governance for public health as well as to, secondly, develop a theory on globalized public health. However, in addition to the methodological question of external validity (generalizability) found in any theoretical production, one thing must be made clear regarding the term or concept of theory when we look at globalization. To start with, we know that globalization is not a univocal or monolithic processual phenomenon. Quite the contrary… taken from a diachronic perspective, we have it interact with five histories (h1, h2, h3, h4, h5) and at least as many crises (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, PHC), which mark the sociohistorical reality of the last 25–30 years. Still from a diachronic perspective, the same processual phenomenon interacts with other so-called ancient histories. Viewed from the opposite side, eg, synchronic perspective, it integrates various key logics, and takes on multiple forms; it infiltrates the imaginations in many ways just as it can be perceived as a global society that is at the same time a risk society, a technoscientific society, a networked and timeless society, a learning society and a market society. However, in spite of using this synchrodiachronic perspective, or, as pointed out by Cusin and Benamouzig, “Notwithstanding the cultural hybridation or deterritorialization of economic, financial, technological and human relations, globalization (…) remains difficult to grasp, even more so to think about in theoretical terms”.41 Now one of the two goals of our research was in fact to develop a theory that “touches and thinks” globalization since it is about a theory on globalized public health.

In our research, contemporary globalization was understood as a matrix of contextual meanings from a given period in time, as a processual phenomenon of the past 25–30 years, a phenomenon that is dialogically synchronic and diachronic, that is itself part of the auto-eco-organized open system of social interactions, which form “globalized public health”. At the same time, the theory constructed here is neither linear nor systematic. We are therefore not dealing with a closed textual production – universalizing or not – which would end, for example, with one-way links. Given the multivocal character of globalization, but especially taking into account our epistemological standpoint in the transdisciplinary handling of our research topic, our theory, to the contrary, is of a recursive, retroactive, plural and openg type. The theory constructed here presents transversality and complexity; it is in line with the paradigm of complexity and nonlinearity and resonates with our own epistemological posture. It stems from the construction of a “complex know-how”, related to “globalized public health”. The figures (Figures 4, 4A, 4B, 4C, 4D) in this theory attest to the dialogic, as well as to the recursive and organizational movement, as they are conceived in the globalized way of thinking public health based on a complex manner of thinking… public health in the global context for the last 25–30 years or so and in the sociohistorical reality of this time. The auto-eco-organized theory, our theory is dependent on the interstructuring from figure to another. This is an enactive theory,h which is the result of interactions between the different figures of the model.42 In our research, theory will thus take shape dynamically, presenting itself as a theoretical interactive model (Figure 4) (provided on CD-ROM) whose entire set of element-parts are visually represented and analytically framed. These 114 element-parts are conceptually united, both figuratively (in the different figures – Figures 4, 4A, 4B, 4C, 4D – and between them, one figure to another) and in the form of hypertext links. Through multireferential analysis, these links specifically authorize theoretical and dynamic relationing, by allowing travel from one concept/item to another (which is conceptually linked to it). The hypertext links then enable readers to “visit” the theory at the same time as they become a component of this theoryi (they are at the same times as they make up links).

Figure 4: A dynamic, nonlinear, historical – social system with five characteristics

Placed in a transdisciplinary and complex perspective, and using a multireferential approach, the inter-relationships between the new globalizing world (in French: NMG-Nouveau monde global) and the field of public health (in French: Champ de la santé publique), in our research, are outside of a linear vision of direct or indirect links, which could have been “fenced in” and presented, for example, in columns and tables, being called “once and for all” or intemporally, being expounded one after another in an exhaustive fashion. Public health has, over the past 25–30 years, been a cross-sectional study object and constitutes a complex unit forming a whole; globalized public health is neither static nor monistic, and the fact that the inter-relationships (which can be made between public health and globalization) belong to different levels of knowledge does not allow for a “directly explicit” vision that can be translated to paper.

Within the theoretical model that expresses it using a synchronic approach, globalized public health appears to be a dynamic nonlinear historical-social system whose characteristic features are:

A synchro-diachronic framework (the existence of a delimiting framework, where globalization and public health can be both seen synchronically and diachronically);

Nonlinearity of interactions (the globalized public health system is dynamic and nonlinear, its nonlinearity being made up of nonlinear interrelations/interactions as well as a series of negative properties: j nonadditivity, nonproportionality, and nonpredictability;

Circular causality between globalization and public health (sharing the previous characteristics of nonadditivity and nonproportionality, the globalized public health system thirdly puts into play an entangled causality, in “echoes”);

A homeostatic function of the system (the globalized public health system is one that is auto-eco-organized and open; it is a system of interactions with its own operating rules, which constitute a force suitable for reproduction. This auto-organization with auto-adaptation of the system will produce one or more “emerging collective behaviors”);

The dialectic character of the system (the new globalizing world initially appears as a sociohistorical process that is both disjunctive and cohesive – “sower” of paradoxes – be it in its logics, in the forms it takes, in the expression of the imaginations that it evokes, in the societies that it rules, even in the crises that have taken hold and have become entrenched under its reign).

In the lens of our secondary research objective: Think “globalized public health”, act locally

Subjected to the contextual imprint of what we call the new globalizing world, public health has thus, over the last quarter century, become “globalized”. Globalized public health appears as a sociohistorical interactive system relating to the 1980–2008 period. It also appears as a temporal and total reality structure of that era. However, globalized public health is also a complete scope of a critical and solidary commitment (to make as public health practitioners) for global governance of public health.

At the dawn of the 21st century, global governance for public health remains to be carried out de facto. Our opinion is in line with that of many authors who are today very concerned because of the focus on the financial benefits of globalization, such focus overshadowing the costs of globalization in terms of health, as well as human and environmental development. Far from being against liberalization of trade and market, it is now time to advocate the establishment of a (new) global governance for public health, a governance that will, among other things, guarantee that the same financial globalization also meets human and social development objectives associated with a more equitable distribution of power and resources among all citizens of the world.

Along these lines, we propose hereunder five paths of action for global governance for public health, which appear as an element-part of the globalized public health system (in Figure 4D). The title of each of the postulates is presented below as they appear (in French) in the model.

Proposition 1 (P1): Fight against the institution of “closed health-related knowledge” in the context of a knowledge-based/learning-based economy and promote knowledge in public health as a global public good.

Proposition 2 (P2): Promote and build a “civically educated” transnational society, which is responsible and socially aware, constituting an opposing force to the logics and forms of globalization.

Proposition 3 (P3): “Remodel” the field of public health taking into account the globalitarian context (for example: a- becoming more transdisciplinary, recognizing its status and expertise independently from other medical fields; b- revitalize universities curricula and other training programs within the context of globalization [eg, adaptation of the field to climate change], c- develop a new approach to global ethics; d-introduce and promote novel theories, conceptual frameworks and technological innovations].

Proposition 4 (P4): Oppose the “right to health” to the current “marketing of disease” in business agreements and at the World Health Organization.

Proposition 5 (P5): Reject social responsibility in its current form (regarding health) of transnational corporations as a strategy for regulating capitalism.

Conclusion

“Globalized public health”, simultaneously a theoretical model and a conceptual framework, concerns the transformation of the field of public health in the sociohistorical context of globalization. The model offers several features to users: (1) it is transdisciplinary, (2) it is interactive (CD-ROM), (3) it is nonlinear (nonlinear interrelations between the procedural and contextual globalization and the field of public health), (4) it is synchronic/diachronic (a double-crossed perspective permits analysis of global social change, the emergence of global agency and the transmutation of the field of public health, in the full complexity of their nonlinear interaction), (5) it offers five characteristics as an auto-eco-organized system of social interactions, or dynamic, nonlinear historical – social system. The model features a visual interface (five inter-related figures), a structure of 30 integrative concepts that integrates 114 other element-parts via 1,300 hypertext links. The model is both a tool for knowledge translation and an interactive heuristic guide designed for practitioners and researchers in public health/community health/population health, as well as for decision-makers at all levels. For public health researchers, the usefulness of the model comes out at different levels: (1) epistemological level (nonlinearity as a new paradigm, until essentially used in mathematical physics, bio-computer science, linguistics), (2) methodological level (“qualitative analysis in writing mode” until then used in communication sciences), (3) technological level (integrating ICTs) while at the same time, participating in recording public health in a new transdisciplinary space. As a knowledge translation tool for public health practitioners, the nonlinear system holds, above all, an important heuristic value, while secondly, supporting a logic of critical commitment, reflection and action. It initially allows practitioners to understand (in all its sociohistorical, cultural, economic and political complexity) the current public health crisis with regard to globalization, and it clarifies the issues in terms of global governance for public health. For the decision-making levels, the model provides concrete paths of action for setting up the globalized health policies. “Globalized public health” can thus be used as a basis: (1) for positioning the potential influence of the different aspects of globalization on the field of public health, while taking into account all the complexity found of their reality, (2) for shaping future health research programs, (3) for developing national and global policies more favorable to health. It should allow setting up avenues of thought and actions to explore, for the present and the future of public health.

In conclusion, we suggest the adoption of a renewed definition of globalization as we consider the choices we have as public health practitioners and researchers. Firstly, we strongly support Wallace’s definition of globalization:

[A]s an awareness of how ‘what affects one affects all,’ a consciousness of our fundamental interdependence as a global community, as well as the resulting process of learning to work collaboratively and share and disperse resources within our global community to ensure social justice, equity, the protection of human rights, and the sustainability of the planet.20

Secondly, as public health practitioners and researchers, we have the alternative between a timid preservation of the status quo, and the elaboration of a collective identity serving as agents capable of organizing a counterweight to globalization and its impact on our field, while practicing public health at the local level. We have the choice to commit ourselves towards an action-driven reflection that goes well beyond good intentions and wishful thinking. These actions will contribute to: (1) drive globalization as newly defined, and build a global collaboration among public health practitioners and researchers; (2) to develop and implement a publicly oriented global governance for public health, which is equitable, participative, accountable, and sustainable. At the dawn of this new century, we must strategize globally and act locally to develop this burgeoning field of globalized public health.

Acknowledgments

Funding has been provided by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF). The opinions, results, and conclusions are those of the author and no endorsement by the CHSRF is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

It is beyond the scope of this paper to present the main debates over globalization’s existence, definitional characterization, historical prominence, and societal contribution, not to mention its processes of incorporation and the resultant complex and contradictory outcomes.

Bibeau and Fortin warn us that there is an urgent need to re-think public health as a science of society and to reinforce critical thinking about the links between macroscopic processes (social, cultural, political, economic) and that which is happening in the minds and bodies of individuals.12 “Danger!” warn Bibeau and Fortin, speaking of the tendency for public health to uncritically adopt certain social theories (for instance, the theory of interest and the theory of rational choice), thereby leading researchers to disconnect study of the macro from study of the micro, to disconnect the context from social agents, conditions of life, the existence of concrete individuals.12 “Danger!” concerning the conceptual pragmatism so dear to public health (social theories become simple tool boxes). And “danger!” when an exclusive priority is given to empirical, descriptive, quantitative studies, while at the same time there is little critical questioning relative to social issues.12

Sociology (socioanthropology), phenomenology, linguistics (sciences of language), medicine and psychiatry.

Viewed from a synchronic perspective, globalization can be understood as an open auto-eco-organized system of social interactions. When combined with a complex reading of globalization, a synchronic point of view allows us to view the global society expressing itself through different faces, each one reflecting the “real totality”/“significant totality” while, at the same time, appearing distinct and complex: (1) a market society; (2) a risk society; (3) a technoscientific society; (4) a networked and timeless society (often referred to as an information society); (5) a knowledge society, which we prefer to call a learning society. As a “comprehensive” entity, the same global society unites various forms and subscribes to certain key logics. We use the term “forms” to designate each of the societal areas of activity or actions affected by globalization. Within the many forms of globalization (listed from f1 to f8 in Table 1), there are eight (from f1 to f8) that we believe to be fundamental: (f1) globalization of capital (nestled in the heart of the market society); (f2) globalization of markets; (f3) globalization of technology, R&D and knowledge (related to the networked and timeless society); (f4) globalization of lifestyles, consumerism, culture (integrated into the market society); (f5) globalization of standards; (f6) globalization as a worldwide policy instrument; (f7) globalization of perceptions of human conditions or of “global conscience” (closely related to the risk society); (f8) communication-media globalization.

Furthermore, globalization subscribes to six different logics (listed from l1 to l6 in Table 1). The logics are defined as abstract and schematic orders of reasoning that exist in a context that allows an understanding of the complexity of reality. First, are market and productive logics (l6, l5), which are closely related, and make up the nucleus of the new globalizing world. Together, they underlie the market society and are the strong and unfailing allies of the first two forms of globalization that were described (f1, f2). Productive logic (l5) is at the root of the organizational changes in globalization on which lean production, re-engineering and “total quality” are based. Market logic extols the marketability of everything and of anything. Secondly, right in the core of the capitalist system is dromocratic logic (whose etymology stems from the Greek word dromos, meaning “acceleration”). In the context of globalization, new forms of expression of the human connection to time are effectively emerging: these are urgency, immediacy, instantaneousness and speed, with acceleration being the common denominator that unites the other forms. The arrival of urgency and instantaneousness in economic life falls right in line with the emergence of a new global space-time. Dromocratic logic (l1) therefore joins another type of logic – cyber logic – which, for its part, is related to the ICT revolution. Cyber logic (l4) and dromocratic logic (l1) contribute to both the learning society and to the networked and timeless society. Technoscientific logic (l3), which represents the union between science and technology, comes in third. Presented as a knowledge production logic in which technical know-how tends to override or guide pure logotheoretical scientific knowledge, technoscientific logic is inseparable from the performance culture and, at the same time, is allied with the cult of speed and subjected to the law of market. Linked to the risk society and to the technoscientific and learning societies, technoscientific logic is still closely related to the rationalization of uncertainty. It therefore builds strong links with evaluative research by legitimizing decision-making and by underlying the rational model of scientific expertise. Coming in fourth is the epidemic logic (l2), which we relate to the breakdown of boundaries. Epidemic logic results from the contagion logic as a mode of propagation by contact, and can carry both harmful and beneficial elements. Whether we are dealing with a computer virus, a rise in political extremism, or information sharing culture and the creation of a worldwide health information community on AIDS, a similar logic – epidemic – seems to guide these total social facts.

Sequential design with a dominant qualitative (QUAL) approach.

Our four research questions were:

1. What must be reported, observed, put forward, or expressed regarding public health in the global context, eg, regarding the existing inter-relationships between, on the one hand, the process and context of contemporary globalization, and, on the other hand, the field of public health?

2. What would be the integrator concepts that would, first of all, allow to theoretically understand the sociohistorical reality and the “meaning” of globalization, integrator concepts in order to be able to then understand, and analytically assign a meaning to the public health “crisis”?

3. What would have to be theorized regarding “globalized public health”, eg, public health in a global context?

4. How could we see global governance for public health in terms of: (a) adapting the practices for the different stakeholders to a new globalized context, (b) cooperating between stakeholders?

In short (recursive + retroactive + plural + open): favourable to questioning (this particularly evokes the criteria of “pragmatic validity” covering questioning, reflection, and working hypotheses that readers may voice).

Varela, cited in Mabilon-Bonfils and colleagues (1999). The term enaction was coined by the first author cited, Franscisco Varela, to characterize the “make emerge” concept in the interactive process and in implementing an epistemology of the complexity.

As a representation of a “complex know-how” and coming from a dialogic, recursive and organizational movement, the theory is a “totality theory” where nonset totality is both less and more than the sum of its parts.

We could say in this regard that the system of “globalized public health” subscribes to the “philosophy of no” from Bachelard.43

References

- 1.Beaglehole R, Bonita R. Public health at the crossroads Achievements and prospects. 2eéd. Cambridge, Royaume-Uni: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy M Collectif de conférenciers. Actes du colloque «Les enjeux éthiques en santé publique». Montréal, Québec: ASPQ Éditions; 1999. Les enjeux en santé publique exigent une éthique pour la complexité; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiffoleau S. Santé et inégalités Nord-Sud: la quête d’un bien public équitablement mondial. In: Les biens publics mondiaux. Un mythe légitimateur pour l’action collective? Paris, France: L’Harmattan; 2002. pp. 245–268. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contandriopoulos AP. À la recherche d’une troisième voie: les systèmes de santé du XXesiècle. In: Pomey M-P, Poullier JP, Lejeune B, editors. Santé publique. Paris, France: Masson; 2000. pp. 637–664. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagnon F, Bergeron P. Le champ contemporain de la santé publique. In: Le système de santé québécois. Un modèle en transformation. Montréal, Québec: Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 1999. pp. 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labonte R, Torgerson R. Interrogating globalization, health and development: Towards a comprehensive framework for research, policy and political action. Crit Public Health. 2005;15(2):157–179. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montaville B. Mondialisation et santé publique: entre exigences éthiques et marchandisation. Lille, France. VIIième Congrès de l’Association française de science politique (Table ronde 1); 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organisation panaméricaine de la Santé. Trade in health services: Global, regional and country perspectives. Washington, DC: Auteur; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verschave FX. La santé mondiale, entre racket et bien public. Paris, France: Charles Léopold Mayer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Global crises – global solutions: Managing public health emergencies of international concern through the revised International Health Regulations Genèva. Switzerland: International Health regulations Revision Project; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapaige V. La santé publique globalisée. Québec, Canada: Les Presses de l’Université Laval; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bibeau G, Contandriopoulos AP, Gomez M, Demers A, Zunzunegui MV, Vissandjée B. Cadre théorique pour les discussions du réseau. Montréal, Quebec: Université de Montréal, REDET (Réseau sur les déterminants de la santé); 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly MP. Mapping the life-world: A future research priority for public health. In: Killoran A, Swann C, Kelly MP, editors. Public health evidence tackling health inequalities. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 553–573. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massé R. Éthique et santé publique. Enjeux, valeurs et normalité. Saint-Nicolas, Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodgson R, Lee K, Drager N. Global health governance discussion paper: A conceptual review, no1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buse K. Governing public-private infectious disease partnerships. Brown Journal of World Affairs. 2004;10(2):225–242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kickbusch I, Quick J. Partnerships for health in the 21st century. World Health Statistical Quarterly. 1998;51:58–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee K, Walt G, Haines A. The challenge to improve global health: Financing the Millennium Development Goals. JAMA. 2004;291:2636–2638. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham ID. Knowledge translation at CIHR. Cornwall, Ontario. CIHR IHSPR-IPPH 7th Annual Summer, «Innovation in knowledge translation research and knowledge translation», NAV Canada Training and Conference Centre; June 22nd–25th; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace BC. Toward equity in health: A new global approach to health disparities. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giddens A. Consequences of modernity. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck U. Sur la voie d’une autre modernité. 2e éd. Paris, France: Aubier; 2001. La société du risque. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freitag M. L’oubli de la société. Pour une théorie critique de la postmodernité. Saint-Nicolas, Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholte JA. Globalization: A critical introduction. Basingstoke, Royaume-Uni: Palgrave Macmillan; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowan T. Creative destruction: How globalization is changing the world’s cultures. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gélinas JB. La globalisation du monde. Laisser faire ou faire? Montréal, Québec: Écosociété; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Held D, McGrew AG. Globalization in question. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rischard JF. High noon 20 Global Problems, 20 Years to Solve Them. New York, NY: Basis Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labonte R, Torgerson R. Frameworks for analyzing the links between globalization and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lapaige V, Labonte R. Globalisation, santé globale et santé publique/santé des populations: liens complexes et utilité différentielle de deux types de modèles théoriques. Ottawa, Ontario. 77e Congrès de l’Association francophone pour le savoir (ACFAS) «La science en français: une affaire capitale!», Université d’Ottawa; May 11–15, 2009; Available from: http://www.acfas.net/programme/d_77_109.html#s260. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodward D, Drager N, Beaglehole R, Lipson D. Mondialisation et santé: un cadre pour l’analyse et l’action. Bulletin de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé. 2002;6:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galea S. Macrosocial determinants of population health. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huynen M, Martens P, Hilderink H. The health impacts of globalisation: A conceptual framework. Globalization and Health. 2005;1(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labonte R, Schrecker T, Runnels V, Packer C. Globalization and health: Pathways, evidence and policy. Londres, Rouyaume-uni: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee K. Health impacts of globalization: Towards a global governance. Basingstoke, Royaume-Uni: Palgrave Macmillan; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K. Globalization and health: An introduction. Basingstoke, Royaume-Uni: Palgrave Macmillan; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laïdi Z. La grande perturbation. Paris, France: Flammarion; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin E. Introduction à la pensée complexe. Paris, France: ESF; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sève L. Émergence, complexité et dialectique. Sur les systèmes dynamiques non linéaires. Paris, France: Odile Jacob; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paillé P, Mucchielli A. L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. Paris, France: Armand Colin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cusin F, Benamouzig D. Économie et sociologie. Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mabilon-Bonfils B, Saadoun L. Le CAPES de sciences économiques et sociales. Paris, France: Vuibert; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bachelard G. La philosophie du non. Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France; 1940. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hegel GWF. Science de la logique. Deuxième tome. Paris, France: Aubier Montaigne; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hegel GWF. Science de la logique. Premier tome, premier livre. Paris, France: Aubier Montaigne; 1972. [Google Scholar]