Abstract

Although developmental timing of gene expression is used to infer potential gene function, studies have yet to correlate this information between species. We analyzed 10,921 ESTs in 3311 clusters from first- and infective third-stage larva (L1, L3i) of the parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis and compared the results to Caenorhabditis elegans, a species that has an L3i-like dauer stage. In the comparison of S. stercoralis clusters with stage-specific expression to C. elegans homologs expressed in either dauer or nondauer stages, matches between S. stercoralis L1 and C. elegans nondauer-expressed genes dominated, suggesting conservation in the repertoire of genes expressed during growth in nutrient-rich conditions. For example, S. stercoralis collagen transcripts were abundant in L1 but not L3i, a pattern consistent with C. elegans collagens. Although a greater proportion of S. stercoralis L3i than L1 genes have homologs among the C. elegans dauer-specific transcripts, we did not uncover evidence of a robust conserved L3i/dauer `expression signature.' Strikingly, in comparisons of S. stercoralis clusters to C. elegans homologs with RNAi knockouts, those with significant L1-specific expression were more than twice as likely as L3i-specific clusters to match genes with phenotypes. We also provide functional classifications of S. stercoralis clusters.

Strongyloides Pathogenesis and Biology

The human round worm Strongyloides stercoralis causes chronic infections of the gastrointestinal tract. In immune-competent hosts, the disease is not life-threatening, but immunodeficiency can lead to dangerous disseminated infections with pulmonary hemorrhage, necrotizing colitis, and 80% mortality if untreated (Igra-Siegman et al. 1981). Strongyloidiasis is difficult to diagnose (Genta 1988), and estimates of worldwide infections range from 70–600 million (Chen et al. 1994). Research goals include development of vaccines (Herbert et al. 2002) and diagnostics (Siddiqui and Berk 2001). Strongyloides has a unique life cycle, with parasitic and free-living generations. Parasitic females in the intestine produce eggs by mitotic parthenogenesis, and first-stage (L1) larvae are excreted in stool. Larvae use environmental and genetic cues to determine their developmental path, becoming free-living adults (heterogonic pathway) or third-stage infective (L3i) larvae (homogonic pathway; Schad 1990; Ashton et al. 1998; Grant and Viney 2001). S. stercoralis free-living worms can complete one life cycle of sexual reproduction outside the host, generating progeny that must re-enter parasitic development (Yamada et al. 1991). Homogonic development resembles the life cycle of other parasitic nematodes (e.g., hookworms), whereas the heterogonic life cycle is much like that of free-living nematodes, including Caenorhabditis elegans, in nutrient-rich conditions. L3i, derived from either parasitic or free-living parents, are suited for long-term survival and dispersal in the environment and are the only stage capable of infection, entering the host by skin penetration before traveling to the lungs and on to the intestine. L3i of S. stercoralis and many parasitic nematodes are developmentally arrested, nonfeeding, and resistant to extreme temperatures and desiccation. They are morphologically similar to the dauer larvae formed by free-living nematodes under unfavorable environmental conditions, a stage that has been extensively studied in C. elegans (Hawdon and Schad 1991; Lopez et al. 2000). C. elegans dauers (L3d) can arrest for months, molting to L4 when favorable conditions return, and much is known about the molecular genetic control of dauer entry and exit (Riddle and Albert 1997). In S. stercoralis, host factors are likely critical to the exit of L3i from arrest, but little is known about the genes involved.

Nematode Comparative Genomics

The C. elegans genome is complete (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998), and substantial annotation has been added by gene expression (Hill et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2001) and RNA interference (RNAi) studies (Kamath et al. 2003). Parasitic nematode genomes are being explored via expressed sequence tags (ESTs); projects on >30 species have generated nearly 300,000 parasitic nematode ESTs (McCarter et al. 2002; Parkinson et al. 2003) including collections from parasites of mammals (Tetteh et al. 1999; Daub et al. 2000; Blaxter et al. 2002) and plants (Popeijus et al. 2000; Dautova et al. 2001; McCarter et al. 2003). Comparative genomic studies that begin to look for correlation in gene expression patterns across species are an important step in understanding the degree of relevance of model species, such as C. elegans, to the biology of species of interest including parasites. Previous characterization of the S. stercoralis genome was limited to 57 ESTs (Moore et al. 1996) and studies of individual genes of interest (Siddiqui et al. 1997, 2000; Massey et al. 2001). Strongyloididae species (S. stercoralis, S. ratti, Parastrongyloides trichosuri) are useful parasites for comparative studies with C. elegans because they can be maintained outside the host for a generation or more, depending upon the species (Viney 1999; Dorris et al. 2002). To create an inventory of S. stercoralis genes and to support studies of Strongyloides pathogenesis and biology, we analyzed an estimated 2947 genes expressed during L1and L3i. Compared to L3i-expressed genes, L1-expressed transcripts from S. stercoralis are more likely to have C. elegans homologs that are expressed and essential during growth in nutrient-rich conditions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As part of a larger effort to examine the genomes of parasitic nematodes, we submitted to GenBank 5′ ESTs from staged S. stercoralis cDNA libraries including 4473 from L1and 6435 from L3i. Here we present the first large-scale analysis of S. stercoralis genes, including a comparison to gene expression patterns in C. elegans.

NemaGene Cluster Formation

To reduce data redundancy and determine gene representation, the 10,908 S. stercoralis sequences were grouped by identity into 3479 contigs and further organized into 3311 clusters. ESTs within a contig derive from nearly identical transcripts, whereas contigs within a cluster may represent splice isoforms of a gene. Clusters ranged in size from a single EST (1868 cases) to 1097 ESTs (Fig. 1). The great majority of clusters have 10 or fewer ESTs. Contig building reduced the total number of nucleotides used for analysis from 4.75 to 2.73 million. The 3311 clusters likely overestimate gene discovery, as one gene could be represented by multiple nonoverlapping clusters (see L3NIEAG.01, Table 1A). Such “fragmentation” was estimated at 11% using C. elegans as a reference genome. After discounting for fragmentation, we estimate that sequences derive from 2947 genes for a discovery rate of 27% (2947/10,908). Assuming 19–20,000 total genes as in C. elegans (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998), these clusters likely represent 15% of all S. stercoralis genes. Contig building successfully increased the length of assembled transcript sequences from 435±101 nucleotides for ESTs to 646±219 for multimember contigs.

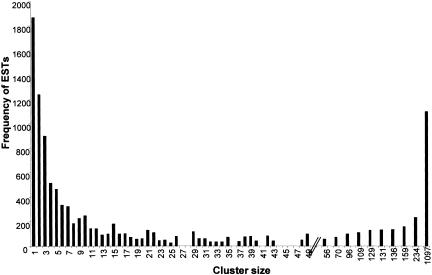

Figure 1.

Histogram for S. stercoralis Nemagene v2.0 clustering showing the distribution of ESTs by cluster size. For example, there were three clusters of size 26 containing a sum of 78 ESTs. Cluster size (x-axis) is shown to scale for 1 to 50 members, with the size of larger clusters indicated. Seventeen percent of all clusters are singletons, and 53% of clusters contain 10 or fewer members. Distribution of contigs sizes is not shown.

Table 1A.

The Most Abundantly Represented Transcripts in the S. Stercoralis cDNA Libraries

|

Non-redundant GenBank

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ESTs from library

|

||||||||

| Cluster | ESTs per cluster | L1 | L3i | Best identity descriptor | Accession SW/TRa | E-value | C. elegans Gene Wormpep | |

| 1 | SS00012.cl | 1097 | 8 | 1089 | S. stercoralis IGG immunoreactive antigen | O44394 | 6e-91 | F54B11.2b |

| 2 | SS00013.cl | 234 | 4 | 230 | Crithidia fasciculata MURF-2 protein | Q34096 | 5e-06 | — |

| 3 | SS00010.cl | 159 | 1 | 158 | Podocoryne carnea POD-EPPT, pod-EPPT protein | Q25677 | 2e-31 | T05A10.1b |

| 4 | SS00028.cl | 136 | 0 | 136 | Zea mays HRGP, hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein | Q41814 | 3e-18 | Y22D7AR1b |

| 5 | SS01581.cl | 131 | 0 | 131 | novel | — | — | — |

| 6 | SS01580.cl | 129 | 6 | 123 | S. stercoralis L3NIEAG.01 | Q9UA16 | 3e-40 | C07A4.3b |

| SS00064.cl | 56 | 0 | 56 | S. stercoralis L2NIEAG.01 | Q9UA16 | 3e-141 | C07A4.3b | |

| SS01574.cl | 48 | 2 | 46 | S. stercoralis L3NIEAG.01 | Q9UA16 | 1e-40 | C07A4.3b | |

| 7 | SS01578.cl | 109 | 101 | 8 | novel | — | — | — |

| 8 | SS01394.cl | 96 | 19 | 77 | Anisakis simplex troponin-like protein | Q9U3U5 | 7e-99 | F54C1.7b |

| 9 | SS01577.cl | 70 | 0 | 70 | C. elegans HCH-1, metalloprotease | Q21059 | 2e-53 | F40E10.1 |

| SS01564.cl | 38 | 0 | 38 | C. elegans HCH-1, metalloprotease | Q21059 | 2e-52 | F40E10.1 | |

| 10 | SS01515.cl | 49 | 47 | 2 | C. elegans ADP/ATP carrier protein | O45865 | 8e-178 | T27E9.1 |

| 11 | SS00004.cl | 49 | 48 | 1 | C. elegans 60S acidic ribosomal protein | Q93572 | 2e-146 | F25H2.10 |

| 12 | SS01616.cl | 43 | 0 | 43 | novel | — | — | — |

| 13 | SS01569.cl | 42 | 26 | 16 | Necator americanus calreticulin precursor | O76961 | 1e-185 | Y38A10A.5b |

| 14 | SS00165.cl | 42 | 36 | 6 | Onchocerca volvulus disulfide isomerase precursor | Q25598 | 4e-209 | C07A12.4b |

| 15 | SS01567.cl | 40 | 37 | 3 | C. elegans 40S ribosomal protein S8 | P48156 | 3e-88 | F42C5.8 |

| 16 | SS01566.cl | 39 | 22 | 17 | Loa loa SXP-1, immunodominant hypodermal antigen | Q9GU97 | 1e-05 | — |

| 17 | SS01565.cl | 39 | 2 | 37 | C. elegans trehalase precursor | Q22195 | 3e-94 | T05A12.2 |

| 18 | SS01563.cl | 38 | 38 | 0 | C. elegans ACT-4, actin 4 | P10986 | 1e-241 | M03F4.2 |

| 19 | SS01562.cl | 37 | 19 | 18 | C. elegans EF-1-ALPHA, elongation factor 1-alpha | P53013 | 4e-186 | F31E3.5 |

| 20 | SS01355.cl | 35 | 19 | 16 | C. elegans FTT-2, 14-3-3 like protein | Q20665 | 9e-131 | F52D10.3A |

| 21 | SS00503.cl | 35 | 33 | 2 | C. elegans COX1, cytochrome C oxidase polypeptide I | P24893 | 5e-108 | — |

| 22 | SS00069.cl | 34 | 34 | 0 | C. elegans COL-34, cuticular collagen | Q20087 | 6e-154 | F36A4.10 |

| 23 | SS01559.cl | 33 | 27 | 6 | C. elegans RPL-4, ribosomal protein L1 | O02056 | 4e-141 | B0041.4 |

| 24 | SS00810.cl | 32 | 25 | 7 | C. elegans RPS-9, ribosomal protein S9 | Q20228 | 6e-97 | F40F8.10 |

| 25 | SS01557.cl | 31 | 0 | 31 | C. elegans EGL-3, prohormone convertase 2 | Q10575 | 5e-120 | C51E3.7A |

SW/TR is SWISS-PROT and TrEMBL Proteinknowledgebase (http://us.expasy.org/sprot/)

C. elegans homolog present but with a lower probability match than the best GenBank descriptor

Distribution of BLAST Matches and Homologs in C. elegans

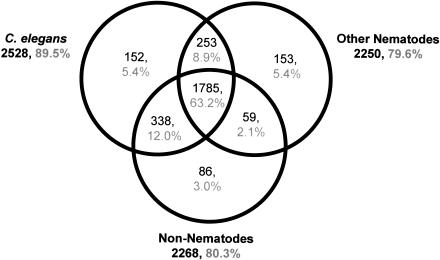

The Figure 2 Venn diagram combines the results of BLAST searches versus three databases for the 85% (2826/3311) of S. stercoralis clusters that had matches to proteins from other species. Strikingly, in the majority of cases where homologies were found, matches were found in all three databases—C. elegans proteins, other nematode sequences, and nonnematode sequences (1785/2826). Many gene products in this category are conserved across metazoans. The 15% of clusters with no homology may contain novel or diverged amino acid sequences specific to S. stercoralis or 3′ or 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) where amino acid level homology would be lacking. A comparison of open reading frame (ORF) length in contig sequences with and without BLAST homology confirms that the mean ORF length is shorter in contigs without homology at 135 amino acids (aa) versus those with homology at 176 aa (Suppl. Fig. 1 available online at www.genome.org), a significant difference at >99% confidence (two-tailed T-test with unequal variance; Snedecor and Cochran 1967). The distribution of ORF length for clusters lacking homology is bimodal, indicating the possible presence of two populations; the first containing novel protein-coding sequences with a distribution of ORF sizes similar to that found in sequences with homology, and a second of UTR sequences containing random and generally short ORFs.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing distribution of S. stercoralis cluster BLAST matches by database. Databases used were: for C. elegans, Wormpep v.54 and mitochondrial protein sequences; for other nematodes, all GenBank nucleotide data for nematodes except C. elegans and S. stercoralis; for nonnematodes, SWIR v.21 with all nematode sequences removed.

As expected for a clade IVA Strongyloididae nematode with phylogenetic proximity to the clade V Rhabditida (Blaxter et al. 1998), the C. elegans genome provided the best source of information for interpreting S. stercoralis sequences: 89.5% of clusters with matches showed homology to a C. elegans gene product (Fig. 2), a higher percentage than observed for Meloidogyne incognita of clade IVB (85%) (McCarter et al. 2003) or the more distant clade I nematode Trichinella spiralis (82%) (M. Mitreva and J. McCarter, unpubl.). The most conserved sequences between S. stercoralis and C. elegans include gene products involved in cell structure, protein synthesis, and metabolism (e-values of 1e-243–1e-187; Suppl. Table 1). Representation of these clusters in L1 and L3i varied from common to rare and from shared to stage-specific. None of the most conserved gene products were nematode-specific. We found that 558 clusters (19.7% of those with matches) had homology only to nematodes, the most conserved with an e-value of 1e-106. Included among the most conserved nematode-specific clusters were homologs of previously characterized C. elegans structural proteins such as UNC-87 calponin (SS01345.cl; Goetinck and Waterston 1994) and LET-805 myotactin (SS03242.cl; Hresko et al. 1999). Cases were also identified of S. stercoralis sequences arising from putative ancestral nematode genes lost in the lineage leading to C. elegans. For example, SS01920.cl contains a prolyl oligopeptidase β-propeller domain (IPR004106; Rennex et al. 1991) not previously described in nematodes but present in our ESTs from S. ratti, P. trichosuri, and Dirofilaria immitis. SS00116.cl has homology to Drosophila melanogaster protein CG1167 (Q9VXQ8) as well as P. trichosuri and D. immitis ESTs, but lacks a C. elegans homolog. Several parasitic nematode species have been demonstrated to harbor prokaryotic-related sequences, including plant parasites that express rhizobacteria-like transcripts from their nuclear genomes (possibly as a result of horizontal gene transfer; Scholl et al. 2003) and filarial nematodes that possess a Wolbachia bacterial endosymbiont (Blaxter et al. 1999). Other nematodes, such as C. elegans, lack prokaryotic-like sequences and endosymbionts. Surveying clusters as in McCarter et al. (2003), we found no evidence of prokaryotic-like sequences in S. stercoralis.

Abundant Transcripts Expressed in L1 Versus L3i

The 25 most highly represented clusters accounted for 27% of ESTs (Table 1A). Representation in a cDNA library generally correlates with abundance in the original biological sample (Audic and Claverie 1997), although artifacts can occur. Among the most abundant clusters, four have homology to known parasite antigens. Two are highly represented in L3i; IGG immunoreactive antigen (SS00012.cl) is observed in patients with chronic Strongyloidiasis (S. Ramachandran, W. Thompson, and F.A. Neva, unpubl.), and L3NIEAG.01, represented by three clusters, is a putative member of the Ancylostoma secreted protein (ASP) family (Hawdon et al. 1996). Among transcripts abundant in both stages are SS01569.cl with homology to genes encoding calreticulin-related antigens in Necator americanus (Pritchard et al. 1999) and Onchocerca volvulus (Rokeach et al. 1994), and SS01566.cl with weak homology to the immunodominant hypodermal SXP-1antigen used as a filarial diagnostic tool (Dissanayake et al. 1992, 1994; Klion et al. 2003).

Highly abundant L1-specific clusters (Tables 1A, 1B) include genes encoding specific collagens (SS00069.cl, SS00001.cl, SS01498.cl, SS01492.cl, and SS01490.cl). Remarkably, 38 S. stercoralis collagen-encoding clusters are detected in L1, with none found in L3i. In C. elegans, the cuticular collagen superfamily consists of about 100 members (Mayne and Brewton 1993), and several dozen are characterized in other nematodes (Selkirk et al. 1989; Selkirk and Blaxter 1990; Cox 1992). Although sharing conserved sequences, nematode collagens are often developmentally regulated and not functionally redundant (Levy et al. 1993). In C. elegans, collagens are expressed in waves coinciding with the four molts (L1to L2, etc.; Johnstone 1994; Johnstone and Barry 1996). A survey of genes expressed in C. elegans dauer versus other stages found no collagen genes among 358 dauer-specific transcripts, but numerous collagens among the genes expressed during nutrient-rich conditions where molting worms were present, including six of the 20 most abundant transcripts (Jones et al. 2001). Likewise, in our survey of 5713 ESTs from root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita L2 (infective dauer-like stage), only three collagen ESTs were found (0.05% of transcripts; McCarter et al. 2003), though collagens are more common in other stages (M. Mitreva and J. McCarter, unpubl.). Down-regulation of collagen expression may be a general feature of the long-lived nonmolting dauer/infective stage in many nematodes, a possibility that is now being explored. Abundant L3i-specific clusters (Tables 1A, 1C) encode several novel proteins (SS01581.cl, SS01616.cl) as well as the first sheath protein (SHP3)-encoding transcript described in S. stercoralis (SS01534.cl). Nematode surface proteins (SHP1–SHP5) have been studied in Brugia malayi and Litomosoides sigmodontis (Selkirk et al. 1991; Zahner et al. 1995; Conraths et al. 1997).

Table 1B.

Abundantly Represented L1-Specific Transcriptsa

|

Nonredundant GenBank

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | ESTs per cluster | Best identity descriptor | Accession SW/TRb | E-value | C. elegans gene wormpep | |

| 1 | SS00001.cl | 26 | C. elegans COL-6, cuticle collagen 6 | P18831 | 5e-134 | ZK1290.3 |

| 2 | SS01536.cl | 22 | C. elegans arginine kinase | Q10454 | 1e-145 | F46H5.3 |

| 3 | SS01533.cl | 21 | Brugia pahangi HSP 90, heat shock protein 90 | O61998 | 6e-234 | C47E8.5c |

| 4 | SS01520.cl | 18 | C. elegans H3, histone 3 | Q10453 | 8e-81 | F45E1.6 |

| 5 | SS00723.cl | 16 | C. elegans 40S ribosomal protein S16 | Q22054 | 2e-58 | T01C3.6 |

| 6 | SS01504.cl | 15 | C. elegans UNC-54, myosin heavy chain | O02244 | 2e-220 | F11C3.3 |

| 7 | SS00026.cl | 15 | Monodelphis domestica ribosomal protein S4 Y isoform | O62739 | 7e-90 | Y43B11AR.4c |

| 8 | SS01498.cl | 14 | C. elegans COL-10, cuticle collagen 10 | Q17460 | 1e-124 | B0222.8 |

| 9 | SS01492.cl | 14 | C. elegans cuticle collagen | Q20778 | 8e-29 | F54D8.1 |

| 10 | SS01490.cl | 14 | C. elegans COL-1, cuticle collagen 1 | Q19763 | 1e-134 | F23H12.4 |

Note: The two largest L1-specific clusters appear in Table 1A

SW/TR is SWISS-PROT and TrEMBL Proteinknowledgebase (http://us.expasy.org/sprot/)

C. elegans homolog present but with a lower probability match than the best GenBank descriptor

Table 1C.

Abundantly Represented L3i-Specific Transcriptsa

|

Nonredundant GenBank

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | ESTs per cluster | Best identity descriptor | Accession SW/TRb | E-value | C. elegans gene wormpep | |

| 1 | SS01556.cl | 31 | Drosophila melanogaster CG16995 protein | Q9VQA7 | 2e-13 | — |

| 2 | SS01540.cl | 23 | C. elegans protein id: CAB02955.1 | O62173 | 8e-54 | F15D3.6 |

| 3 | SS01145.cl | 22 | Dictyostelium discoideum SRF related protein | O76853 | 8e-14 | T05A10.1c |

| 4 | SS00011.cl | 22 | C. elegans lipase | O16380 | 3e-32 | K12B6.3 |

| 5 | SS01534.cl | 21 | Litomosoides sigmodontis SHP3, microfilarial sheath protein | Q25402 | 4e-25 | F55B11.3c |

| 6 | SS01532.cl | 21 | C. elegans MAP1A/1B, microtubule associated protein | Q09490 | 2e-65 | C32D5.9 |

| 7 | SS01528.cl | 20 | C. elegans tyrosine aminotransferase | Q93703 | 7e-105 | F42D1.2 |

| 8 | SS01517.cl | 17 | C. elegans HSP70, heat shock protein 70 | Q22758 | 4e-62 | T24H7.2 |

| 9 | SS01508.cl | 16 | C. elegans protein id: AAB65951.1 | O16458 | 2e-94 | F41E6.9 |

| 10 | SS01505.cl | 15 | C. elegans protein id: CAB03200.1 | P90845 | 4e-33 | F25B3.6 |

Note: The seven largest L3i-specific clusters appear in Table 1A

SW/TR is SWISS-PROT and TrEMBL Proteinknowledgebase (http://us.expasy.org/sprot/)

C. elegans homolog present but with a lower probability match than the best GenBank descriptor

Comparative Genomics of Transcription in S. stercoralis L1 versus L3i and C. elegans Nutrient-Rich Conditions versus Dauer

Figure 3 displays the distribution of the 3311 clusters in a Venn diagram based on EST library of origin. The majority of clusters had representation only in L1or L3i, with just 12% of clusters containing ESTs from both libraries. Excluding singletons, 27% of the clusters are mixed L1/L3i. The limited number of shared clusters between the two libraries is most likely a result of true differences in the abundance of gene expression between the two stages; even for transcripts with abundant representation, many clusters remain stage-specific or stage-biased (Suppl. Fig. 2). Limited overlap could also result from allelic variation between the two S. stercoralis strains used in library production or from limited depth of sampling. Allelic variation between strains is unlikely to result in the formation of multiple clusters representing the same gene, because any contigs sharing >93% nucleotide identity over ≥100 nucleotides will share the same cluster. Nuclear polymorphisms are rarely this extensive, especially within coding regions. In C. elegans, comparison of the N2 and the reproductively isolated Hawaiian strain detected a polymorphism rate of 0.115% over 5.4 million bases (Wicks et al. 2001). The EST sample size is sufficient that 261of the clusters with stage-biased expression are large enough (≥ four members for L1, ≥ six members for L3i) that bias toward one stage can be considered significant by the pairwise-test (P<0.05; Audic and Claverie 1997).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing distribution of S. stercoralis clusters based on library of origin of each cluster's EST members. The majority of clusters are either L1-specific or L3i-specific.

Based on morphology and behavior, C. elegans dauer larvae and infective-stage L3i of many animal parasites are believed to be equivalent, and searches for homologs of C. elegans dauer pathway genes are underway in many parasites, including S. stercoralis (Massey et al. 2001). As a first comprehensive comparative genomics approach to examining conservation of gene function during nematode evolution, we compared transcripts with stage-specific or stage-biased gene expression between S. stercoralis (L1 vs. L3i) and C. elegans (dauer vs. other stages). The aim of this comparison was to determine whether there is any pattern of shared expression of homologs in like-stages between species (L3i with dauer, and L1with other stages). In C. elegans, gene expression in dauer versus other stages had previously been compared in our lab by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE; Jones et al. 2001). In that study, nondauer stages were mixtures of all feeding larval stages (L1–L4) and adults containing embryos growing in nutrient-rich conditions where L1s made up ∼5% of the sample volume; for simplicity we refer to these mixed stages as “nutrient-rich-specific”. Of 11,130 detected C. elegans genes, 6496 were common to both groups, 328 were identified as significant dauer-specific, and 489 were nutrient-rich-specific by the Fisher exact test (P < 0.05; Jones et al. 2001).

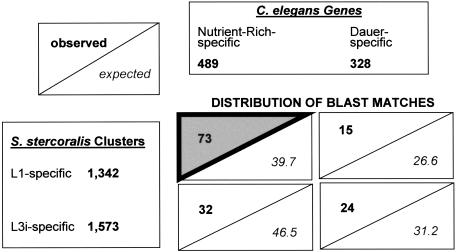

S. stercoralis L1- and L3i-biased or -specific clusters were compared to the C. elegans dauer-specific and nutrient-rich-specific genes at a variety of BLAST thresholds (1e-30, 1e-15, and 1e-05). In all cases, the overwhelming result was that BLAST matches were dominated by S. stercoralis L1/C. elegans nutrient-rich matches, with L1/dauer, L3i/nutrient-rich, and L3i/dauer matches less common. This was true even though L1s made up only a fraction of the C. elegans mixed-stage starting material used for SAGE, perhaps because of shared expression between all feeding and growing stages or specifically between L1s and embryos. One example is given in Figure 4 using the full set of S. stercoralis L1-and L3i-specific clusters at the 1e-30 BLAST threshold. Based on the relative sizes of the input data sets (1342, 1573, 489, 328), the null expectation is that of the 144 matches found, 39.7 would fall in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant; instead, 73 such matches were observed. Assessment of the deviation of the observed from the expected values results in the highly significant χ2 (χ2) value of 39.3. A χ2 value >7.8 is required for significance at P < 0.05 (Steel and Torrie 1960; Snedecor and Cochran 1967). Significant concentrations of matches in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant were also seen at BLAST cut-offs of 1e-15 and 1e-05.

Figure 4.

Data sets of S. stercoralis L1-specific and L3i-specific clusters (lower left) were used to search sets of C. elegans nutrient-rich-specific and dauer-specific clusters (top right) at 1e-30, resulting in 144 BLAST matches distributed in four quadrants (lower right). Each quadrant shows the number of observed matches and expected matches, based upon the null hypothesis that the distribution of matches would reflect the relative sizes of the input data sets. Matches were found to be concentrated in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant (gray triangle). Although individual S. stercoralis clusters may lack adequate sample size to be considered significantly biased in their expression alone, the full set of L1- and L3i-specific clusters including singletons can be used in this comparison, as the collection as a whole is significantly biased. Restriction of the L1 and L3i sets to clusters with significant L1- and L3i-biased expression shows the same type of distribution, with a concentration in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant.

Next, we restricted consideration to just the larger 178 L1-biased and 83 L3i-biased S. stercoralis clusters with significant biased representation (Suppl. Fig. 2; Audic and Claverie 1997). In this case as well, the comparison to C. elegans showed a strong preference toward L1/nutrient-rich matches, with highly significant χ2 values at BLAST cut-offs of 1e-15 and 1e-05. For example, at 1e-15, 36 of 53 matches were in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant, versus an expectation of 21.6. Sample sizes were inadequate for comparison at 1e-30. In addition to the assumption that the distribution of matches would reflect the relative sizes of the starting data sets, we also considered the null hypothesis that the S. stercoralis L3i data set should show a distribution of matches similar to the C. elegans nutrient-rich versus dauer categories, as is seen with the L1data set. This null hypothesis was also rejected at P < 0.05; the L3i-specific or L3i-biased data sets were significantly more likely than the L1data sets to distribute their matches in dauer by measures of 1.3- to 3.9-fold, depending on the data sets and thresholds used.

At least two factors could account for the concentration of S. stercoralis/C. elegans BLAST matches in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant. First, these matches may reflect actual evolutionary conservation of expression pattern by homologs between the two species; that is, genes excluded from L3i in S. stercoralis tend to be excluded from dauer in C. elegans. Second, genes expressed during L1and nutrient-rich growth may be more likely to have conserved sequences than genes expressed during L3i/dauer. Evidence suggests that both these factors are involved. Addressing sequence conservation, Jones et al. (2001) noted that 15 of the 20 most abundant dauer-specific transcripts in C. elegans were of unknown function, whereas fewer of the most abundant nondauer-specific transcripts were unknowns (8 of 20), suggesting the possibility that dauer-specific genes are more rapidly evolving or less likely to be found in other species (Jones et al. 2001). Other C. elegans studies have also found that genes with roles in later or specialized stages of development (i.e., dauer as opposed to embryonic or germ line) tend to be less conserved (Castillo-Davis and Hartl 2002; Kamath et al. 2003). Similarly, S. stercoralis L3i clusters appear to be less conserved than L1clusters. At a BLAST threshold of 1e-05, 95% of significant L1-biased clusters have C. elegans homologs, compared to only 82% of the L3i-biased clusters. Also at 1e-05, 84% of L1-specific clusters have C. elegans homologs, compared to only 66% for L3i-specific clusters. Recalculating the expected values for the quadrants in the comparisons described above, counting only clusters with BLAST matches for input data set sizes, still results in significant χ2 values, but less severe than those seen before the adjustment. For instance, in the Figure 4 example the χ2 value changes from 39.7 to 27.8. Our current interpretation is that, in part, the reason for the concentration of matches in the L1/nutrient-rich quadrant is the higher degree of sequence conservation in these stages, with the remainder resulting from shared expression pattern of homologs.

While a greater proportion of S. stercoralis L3i-specific genes than L1-specific genes have homologs among the C. elegans dauer-specific transcripts, we did not uncover evidence of a robust L3i/dauer `expression signature' conserved between the two nematodes. There are a number of challenges that may prevent use of this EST-based comparative genomics approach to identify key genes involved in these stages of presumably shared origin. First, a major limitation of this approach is sample size. By using only stage-biased or stage-specific transcripts in our comparison, we are essentially limiting analysis to 4.2% of C. elegans genes and 1.2% or 13.3% of S. stercoralis genes (assuming 19,500 genes per species). The intersection of these comparisons tends to be rather small (several dozen to several hundred matches). Second, use of stage specificity as a criterion may be inappropriately severe, because expression of a gene in other stages does not prevent it from still playing a critical role in the stage of interest (i.e., L3i/dauer). In addition, we currently have no available information to make comparisons based on organ or tissue of expression; substantial changes in gene expression that occur in the context of specific cells may be lost in our whole-organism analysis. Third, the speed of evolution of genes involved in L3i and dauer may make detection of homologs involved in these stages more difficult than for genes expressed in other more conserved stages. It is also possible that although they are structurally and functionally very similar, the C. elegans dauer stage and S. stercoralis L3i stage may have evolved to be substantially different at the molecular level or could even conceivably have arisen by convergent evolution. Overcoming these challenges would likely involve having the full S. stercoralis genome sequence (for ortholog mapping) as well as full-genome microarray or SAGE data that could be compared to data generated by the equivalent methods in C. elegans.

Homologs of C. elegans Genes Involved in Dauer Determination and Biology

As an additional approach to uncover S. stercoralis genes involved in L3i/dauer biology, clusters were examined for homologs of 37 genes involved in dauer entry or maintenance in C. elegans (Jones et al. 2001). Twenty-five such C. elegans genes identified 36 S. stercoralis homologs, including 12 with high identity matches that may indicate orthology (Table 2). Included among the list are eight homologs of daf (dauer formation defective) genes (Georgi et al. 1990; Estevez et al. 1993; Larsen et al. 1995; Lin et al. 1997), as well as glutathione peroxidase genes (Vanfleteren 1993) and superoxide dismutase. Five S. stercoralis homologs showed a bias toward expression in L3i versus L1, including homologs of the daf-12 nuclear hormone receptor (SS01351.cl), F26E4.12 glutathione peroxidase (SS01468.cl), F38E11.2 heat shock protein (SS01374.cl), F22F1.1 histone H1 (SS01412.cl), and most strikingly a homolog of T26C11.2 (SS00028.cl) with 136 L3i ESTs and zero L1 ESTs. The availability of these sequences will aid in a more thorough study comparing C. elegans dauer and S. stercoralis L3i.

Table 2.

C. Elegans Genes with Potential Roles in Dauer Having S. Stercoralis Homologs

| S. stercoralis homologs | C. elegans gene | Description | E-value | Possible ortholog? | Other homologsa gene | Description | E-value | S. stercoralis L1 | ESTs L3i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS00947.cl | C05D2.1 | daf-4 TGF-B receptor | 2e-22 | yes | see below | 0 | 3 | ||

| SS00947.cl | F29C4.1 | daf-1 kinase | 1e-07 | no | see above | 0 | 3 | ||

| SS01351.cl | F11A1.3 | daf-12, nuclear hormone receptor | 3e-58 | yes | F33D4.1 | nhr-8, nuclear hormone receptor | 8e-08 | 0 | 7 |

| SS03246.cl | R13H8.1 | daf-16 forkhead domain | 5e-46 | yes | R13H8.2 | 7e-29 | 1 | 0 | |

| SS02087.cl | R13H8.1 | daf-16 forkhead domain | 2e-13 | no | none | 1 | 0 | ||

| SS00592.cl | R13H8.1 | daf-16 forkhead domain | 1e-13 | no | F26D12.1 | fkh-7, forkhead domain | 1e-33 | 0 | 2 |

| SS03322.cl | R13H8.1 | daf-16 forkhead domain | 3e-07 | no | none | 1 | 0 | ||

| SS02393.cl | B0334.8 | daf-23 phosphoinositide 3-kinase | 3e-10 | no | F35H12.4 | phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase | 1e-57 | 0 | 1 |

| SS01344.cl | C15F1.b | sod-1 superoxide dismutase | 8e-64 | yes | see below | 2 | 5 | ||

| SS01344.cl | F55H2.1 | sod-4 superoxide dismutase | 1e-36 | no | see above | 2 | 5 | ||

| SS01344.cl | ZK430.3 | superoxide dismutase | 2e-57 | no | see above | 2 | 5 | ||

| SS01223.cl | C08A9.1 | sod-3 superoxide dismutase | 8e-72 | yes | F10D11.1 | sod-2 superoxide dismutase | 3e-74 | 4 | 1 |

| SS00590.cl | C11E4.1 | glutathione peroxidase | 2e-90 | yes | see below | 5e-82 | 0 | 2 | |

| SS00590.cl | C11E4.2 | glutathione peroxidase | 5e-82 | yes | see above | 2e-90 | 0 | 2 | |

| SS01468.cl | F26E4.12 | glutathione peroxidase | 2e-60 | yes | R05H10.5 | glutathione peroxidase | 2e-60 | 2 | 10 |

| SS01468.cl | R03G5.5 | glutathione peroxidase | 2e-54 | no | R05H10.5 | glutathione peroxidase | 2e-60 | 2 | 10 |

| SS00462.cl | T24H7.1 | prohibitin | 3e-41 | no | Y37E3.9 | prohibitin | 3e-80 | 2 | 0 |

| SS01126.cl | R11A8.4 | sir-2 silancing information regulator | 1e-17 | no | none | 1 | 3 | ||

| SS02217.cl | H42K12.1 | pdk-1 protein kinase | 7e-09 | no | none | 0 | 1 | ||

| SS02646.cl | T28B8.2 | ins-1 insulin like | 3e-12 | no | none | 0 | 1 | ||

| SS01374.cl | F38E11.2 | hsp-12, alpha-B-crystallin | 3e-9 | no | C14B9.1 | hsp-12, alpha-B-crystallin | 3e-13 | 0 | 8 |

| SS03005.cl | R02C2.3 | G-protein receptor | 2e-21 | no | T14D7.2 | 4e-100 | 1 | 0 | |

| SS00028.cl | T26C11.2 | novel | 1e-10 | no | Y22D7AR.1 | tyrosine phosphatase | 4e-16 | 0 | 136 |

| SS03404.cl | F36D3.9 | cysteine protease | 2e-08 | no | Y65B4A.2 | cysteine proteinase | 5e-45 | 1 | 0 |

| SS01412.cl | F22F1.1 | histone H1 | 3e-35 | yes | F59A7.4 | histone H1 | 3e-34 | 0 | 9 |

| SS00818.cl | F22F1.1 | histone H | 3e-40 | yes | M163.3 | his-24 histone | 2e-42 | 3 | 0 |

| SS01412.cl | C30G7.1 | histone H1 | 1e-18 | no | see above | 0 | 9 | ||

| SS00818.cl | C30G7.1 | histone H1 | 1e-24 | no | see above | 3 | 0 | ||

| SS00190.cl | C12D8.10 | akt-1 kinase | 5e-25 | no | B0545.1B | tpa-1 protein kinase | 2e-87 | 0 | 2 |

| SS03259.cl | C12D8.10 | akt-1 kinase | 3e-23 | no | T01H8.1B | spk-1 protein kinase C | 1e-44 | 1 | 0 |

| SS03125.cl | C12D8.10 | akt-1 kinase | 6e-27 | no | ZK303.2B | kin-1 protein kinase | 1e-34 | 0 | 1 |

| SS02139.cl | F56C9.1 | protein phosphatase 1 | 1e-73 | yes | F23F11.6 | serine/threonine phosphatase | 6e-73 | 1 | 0 |

| SS00017.cl | F56C9.1 | protein phosphatase 1 | 2e-51 | yes | F23F11.6 | serine/threonine phosphatase | 1e-55 | 1 | 3 |

| SS00691.cl | F56C9.1 | protein phosphatase 1 | 6e-37 | no | F38H4.3 | serine/threonine phosphatase | 1e-68 | 2 | 0 |

| SS00509.cl | F56C9.1 | protein phosphatase 1 | 4e-46 | no | C05A2.1 | serine/threonine phosphatase | 5e-54 | 0 | 2 |

| SS02292.cl | F56C9.1 | protein phosphatase 1 | 5e-45 | no | Y75B8A.30 | serine/threonine phosphatase | 3e-61 | 0 | 1 |

The following C. elegans genes with potential roles in dauer did not have S. stercoralis homologs among the clusters: Y55D5A.b, daf-2; ZC395.6, gro-1; ZC395.2, clk-1; F25E2.5, daf-3; R10H10.2, spe-26; Y54G11A.6, ctl-1 catalase; B0412.2, daf-7; C08H9.5, cold-1; Y54G11A.5, peroxisomal catalase.

Selected C. elegans genes include those involved in signaling pathways for dauer entry and exit, genes known to play a role in dauer, and genes of interest with high levels of dauer expression in comparison to other stages (Jones et al. 2001).

The highest matching additional C. elegans homolog of the S. stercoralis cluster

Comparison to C. elegans Genes with RNAi Phenotypes

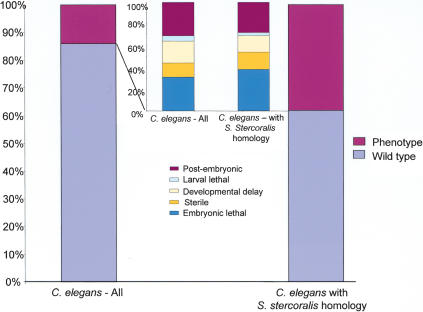

RNAi, whereby the introduction of a sequence-specific double-stranded RNA leads to degradation of corresponding mRNAs (Fire et al. 1998), has allowed the surveying of thousands of C. elegans genes for knockout phenotypes (Fraser et al. 2000; Gonczy et al. 2000; Maeda et al. 2001; Kamath et al. 2003). Such information is potentially transferable to understanding which genes play crucial roles in other nematodes, including parasites. RNAi has been demonstrated in three parasitic nematodes (Hussein et al. 2002; Urwin et al. 2002), but is not yet adaptable to rapid screening. We compared a list of 4786 C. elegans genes assayed by RNAi as of June 2002 to the list of the 2528 S. stercoralis clusters with C. elegans homologs. RNAi experimental information was available for the most closely related homolog in 1059 cases, and a phenotype was apparent in 401cases (38%; Suppl. Tables 2, 3). In contrast, RNAi surveys of all predicted genes in C. elegans resulted in phenotypes in just 10%–14% of cases (Kamath et al. 2003) and 27% for genes with evidence of expression (Maeda et al. 2001). Additionally, C. elegans genes with expressed S. stercoralis homologs were more likely to have severe RNAi phenotypes such as embryonic lethality and sterility (Fig. 5). Previously, a correlation between severity of phenotype in C. elegans and sequence conservation across phyla had been shown by selecting genes with homologs in Saccharomyces, Drosophila, and human (Fraser et al. 2000; Gonczy et al. 2000). Here we show the same trend following detection of homology with an expressed gene in another nematode species.

Figure 5.

A comparison of phenotype distribution between all RNAi-surveyed C. elegans genes (left) vs. only those genes with homology to S. stercoralis (right). Large columns display percent with and without phenotype. Small columns display percent breakdown of various phenotypes observed. C. elegans genes with S. stercoralis homologs are significantly more likely to have pheno-types by RNAi.

To determine whether genes expressed at various stages and levels in S. stercoralis differ in the likelihood that their C. elegans homologs have RNAi phenotypes, we compared phenotypes observed for the best-scoring homologs of L1- and L3i-expressed clusters. C. elegans homologs of S. stercoralis clusters with significant L1-biased (178) or L3i-biased (83) expression show a significant difference, with 69% (62/90) of L1homologs having phenotypes versus only 30% for L3i (10/33; χ2 test, P<0.05; Snedecor and Cochran 1967). Nearly half of the L1 homologs with phenotypes are ribosomal proteins (20) or structural proteins such as actin and myosin (9), categories not found among the L3i-biased genes. Clusters with lower levels of expression did not show a significant difference between L1and L3i; using the full sets of S. stercoralis L1-specific (1342) and L3i-specific (1573) clusters resulted in C. elegans homologs with phenotypes for 42% of L1 (230/551) versus 37% of L3i clusters (209/563). Previous data showed that evidence of expression in C. elegans or other nematodes enriches for genes with RNAi phenotypes (Fraser et al. 2000; Maeda et al. 2001; McCarter et al. 2003). The comparison here between L1and L3i demonstrates that the particular stage and level of expression in another nematode is also an important predictor of phenotype, with C. elegans genes having S. stercoralis homologs highly expressed in L1being nearly six times as likely to have a phenotype as the average C. elegans gene surveyed by RNAi. High-level expression in L3i does not have quite as dramatic an effect of enriching for genes with phenotypes (2.5-fold vs. sixfold increase) for perhaps two reasons. First, high-throughput RNAi screens in C. elegans have observed nematodes during growth in nutrient-rich conditions when dauer larvae are not present. Screening for RNAi phenotypes in worms induced to enter dauer may detect phenotypes not seen in standard screens. It is also possible that the repertoire of genes expressed in dauer/L3i are truly less likely to result in phenotypes following knockout as genes active in L1.

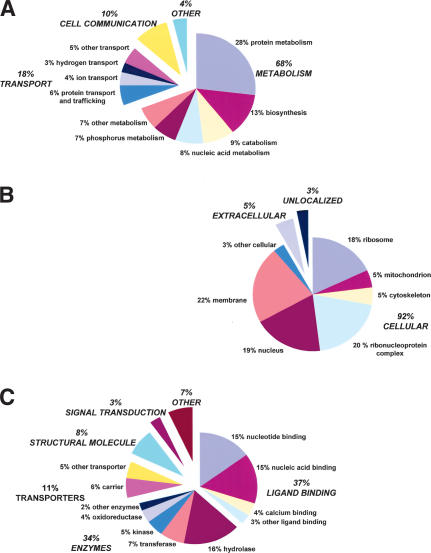

Functional Classification Based on Gene Ontology and KEGG Assignments

To categorize transcripts by function, we utilized the Gene Ontology (GO) classification (www.geneontology.org). InterProScan (ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/unix/iprscan) was used to match S. stercoralis clusters to InterPro protein domains which themselves are already mapped into the GO hierarchy. Of 3311 clusters, 1298 (39%) align to InterPro domains, and 870 (26%) map to GO. Among the more highly expressed stage-biased clusters, 49% of L1-biased clusters map to the GO hierarchy, compared to only 36% for L3i. GO representation for S. stercoralis clusters is shown by biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 6, Suppl. Table 4). GO representation among four nematode species is shown in Supplemental Table 5 (Quackenbush et al. 2001). The greater percentage of extracellular mappings in S. stercoralis is largely attributable to 17 contigs with homology to the VAP venom allergen family (Blaxter 2000; Ding et al. 2001). As an alternative categorization method, clusters were assigned to metabolic pathways in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (www.genome.ad.jp/kegg). Enzyme commission numbers were assigned to 484 of 3311 clusters (15%), which allowed mapping of 285 (9%) to KEGG (Table 3). Metabolic pathways well represented by the S. stercoralis clusters include glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and biochemical networks involving pyruvate, butanoate, purines, pyrimidines, glutamate, tyrosine, and glycerolipids. Four enzymes involved in nucleotide sugar metabolism were expressed in L1, whereas none were expressed in L3i. These include SS00993.cl, encoding a putative UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (EC 2.7.7.9), and SS0508.cl and SS01928.cl encoding dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratases (EC4.2.1.46). The C. elegans homolog of this enzyme, F53B1.4, is strongly expressed in most life-cycle stages but absent from dauer larvae (Hill et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2001). Genes encoding nucleotide sugar biosynthesis enzymes in C. elegans are expressed in many tissues, including gut, neurons, and the vulva. Mutations in some of these genes affect vulval invagination, oocyte development, and embryogenesis (Herman and Horvitz 1997; Herman et al. 1999). The observed down-regulation of nucleotide sugar metabolism in L3i and dauer is consistent with the lack of new cell division and DNA replication in these developmentally arrested stages. Complete lists of GO and KEGG mappings for S. stercoralis are available at www.nematode.net.

Figure 6.

Percentage representation of gene ontology (GO) mappings for S. stercoralis clusters by (A) biological process, (B) cellular component, and (C) molecular function. See Supplemental Table 4 for details. Note that individual GO categories can have multiple mappings. For instance, GO:0015662: P-type ATPase (cluster-SS01525, InterPro domain IPR004014) is a nucleic acid-binding protein, a hydrolase enzyme, and a transporter.

Table 3.

KEGG Biochemical Pathway Mappings for S. Stercoralis Clusters

| Clusters per library

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG categories representeda | Clusters | L1 | L3i | L1/L3i | Enzymes |

| 1.1 Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 21 | 14 | 6 | 1 | 13 |

| 1.2 Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 19 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| 1.3 Pentose phosphate cycle | 14 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| 1.4 Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1.5 Fructose and mannose metabolism | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 9 |

| 1.6 Galactose metabolism | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| 1.7 Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1.8 Pyruvate metabolism | 24 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| 1.9 Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 10 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 1.10 Propanoate metabolism | 14 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 8 |

| 1.11 Butanoate metabolism | 15 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 11 |

| 2.1 Oxidative phosphorylation | 22 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| 2.5 Methane metabolism | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3.1 Fatty acid biosynthesis (path 1) | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3.2 Fatty acid biosynthesis (path 2) | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 3.3 Fatty acid metabolism | 18 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| 3.4 Synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 3.5 Sterol biosynthesis | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 3.6 Bile acid biosynthesis | 9 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| 3.8 Androgen and estrogen metabolism | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 4.1 Purine metabolism | 20 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| 4.2 Pyrimidine metabolism | 19 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 11 |

| 4.3 Nucleotide sugars metabolism | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 5.1 Glutamate metabolism | 17 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| 5.2 Alanine and aspartate metabolism | 17 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 8 |

| 5.3 Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 14 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| 5.4 Methionine metabolism | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5.5 Cysteine metabolism | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 5.6 Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 11 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| 5.7 Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 5.8 Lysine biosynthesis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5.9 Lysine degradation | 14 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 7 |

| 5.10 Arginine and proline metabolism | 16 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 8 |

| 5.11 Histidine metabolism | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| 5.12 Tyrosine metabolism | 15 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| 5.13 Phenylalanine metabolism | 11 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| 5.14 Tryptophan metabolism | 18 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| 5.15 Phenylalanine/tyrosine/tryptophan biosynthesis | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 6 |

| 5.16 Urea cycle and metabolism of amino groups | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 6.1 β-Alanine metabolism | 11 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| 6.2 Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 6.3 Aminophosphonate metabolism | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 6.4 Selenoamino acid metabolism | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 6.5 Gyanoamino acid metabolism | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 6.6 D-Glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 6.7 D-Arginine and D-ornithine metabolism | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 6.9 Glutathione metabolism | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 7.1 Starch and sucrose metabolism | 15 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| 7.2 Glycoprotein biosynthesis | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 7.4 Aminosugars metabolism | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 8.1 Glycerolipid metabolism | 19 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 14 |

| 8.2 Inositol phosphate metabolism | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 8.4 Phospholipid degradation | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 8.5 Sphingoglycolipid metabolism | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 8.8 Prostaglandin and leukotriene metabolism | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 9.2 Riboflavin metabolism | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 9.3 Vitamin B6 metabolism | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9.4 Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 9.5 Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 9.8 One carbon pool by folate | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9.11 Ubiquinone biosynthesis | 25 | 7 | 15 | 3 | 3 |

555 total and 312 unique mappings; 61 metabolic pathways are represented out of 83 possible

Conclusions

Increasing information on stage of gene expression now makes possible comparisons of gene expression patterns between related species. In one of the first such studies, we examined expression of homologous genes in S. stercoralis and C. elegans, observing conservation of genes expressed during growth in nutrient-rich conditions and exclusion of collagen expression from the dauer-equivalent stage in both species. Information on additional species and stages will help to refine our view of how patterns of gene expression have changed during nematode evolution. However, based on this analysis we anticipate that detecting robust stage-specific `expression signatures' conserved between distant nematodes will be quite challenging. Microarray experiments, which can better detect levels of gene expression than ESTs, will aid in these comparisons. As recently as February 2000, only 57 ESTs from Strongyloididae nematodes had been deposited in dbEST. As of March 2003, our submissions have brought that number to 30,115, including ESTs from the closely related species S. stercoralis (11,392), S. ratti (10,760), and P. trichosuri (7963; Dorris et al. 2002). Stages represented include L1, L2, L3, and adult, and derive from both the homogonic and heterogonic life cycles. Unlike most parasites, the heterogonic cycle of Strongyloididae species (Viney 1999) allows maintenance of cultures outside the host mammal in lab conditions identical to those used for C. elegans. Strongyloididae species are therefore more amenable to attempts at transferring techniques developed in C. elegans to parasitic nematodes, including transformation (Lok and Massey 2002) and RNAi, as well as mutagenesis and gene mapping. The number of generations for which a Strongyloididae species can be maintained in culture away from its host varies greatly from only one for S. stercoralis to upwards of 50 for P. trichosuri (W. Grant, pers. comm.). Such technical advantages for study, as well as the medical importance of S. stercoralis, make Strongyloididae species good candidates for the eventual generation of a draft genome sequence.

METHODS

Libraries and EST Generation

The L1cDNA library was created from 2×103 S. stercoralis larvae recovered from jirds (Meriones unquiculatus) infected with a strain maintained in dogs. The L3i cDNA library used 4×105 larvae from a strain passed repeatedly in Patas monkeys (Harper et al. 1984). The genetic or environmental propensity of the strains to favor heterogonic versus homogonic development is not known. Unidirectional libraries were constructed in Uni-ZAP XR (Stratagene; McCarrey and Williams 1994). The L1 library had an unamplified titer of 1×105 plaque-forming units per mL (pfu/mL), an average insert size of 675 bp, and ∼15% nonrecombinants. The L3i library had an unamplified titer of 1.5×106 pfu/mL, an average insert size of 957 bp, and ∼3% nonrecombinants. For sequencing, the phagemid was excised and replicated in XL-1 Blue MRF′ cells. Sequencing and EST processing were performed as described (Hillier et al. 1996; Marra et al. 1999; McCarter et al. 2000, 2003). Prior to dbEST submission, sequences were processed to assess quality, trim vector, remove contaminants and cloning artifacts, and identify BLAST similarities (Hillier et al. 1996). The Web site www.nematode.net provides information on trace files and clone ordering. From 14,950 attempts, 11,335 sequences (76%) passed filtering and were submitted to dbEST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST). The average submitted read length was 435±101 nucleotides (457 for L1, 420 for L3i). The 10,921 ESTs analyzed here include 4473 L1and 6435 L3i submissions. An additional 414 ESTs submitted later are not included. Reads were failed for poor trace quality (∼19.8% of all reads); missing insert (∼3.7%); E. coli contamination (∼0.4%); and small insert size (∼0.1%).

Clustering and Sequence Analysis

Clustering was performed as described (McCarter et al. 2003) using Phred, Phrap, Consed, and BLAST programs (Ewing et al. 1998; Ewing and Green 2000). The completed assembly, Nema-Gene Strongyloides stercoralis v 2.0, is available at www.nematode.net. Fragmentation, defined as the representation of one gene by multiple nonoverlapping clusters, was estimated by examining S. stercoralis clusters with homology to C. elegans. Best-scoring BLASTX matches against Wormpep found matches to 2348 nonoverlapping regions of 2090 C. elegans proteins, for a fragmentation index of 11%. Two hundred-sixteen proteins were represented in two nonoverlapping regions, 16 proteins in three regions, and two proteins in four regions. Overlapping matches by multiple clusters to the same region of a C. elegans gene was not considered fragmentation, as these clusters had already been directly compared to one another by BLASTN. WU-BLAST sequence comparisons were performed as described (Altschul et al. 1990; http://blast.wustl.edu [Gish 2002]; McCarter et al. 2003) using contig sequences as queries versus multiple databases, including the SWIR v.21(5/19/2000) protein database, Wormpep v.54 C. elegans protein database (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, unpubl.), and internal databases constructed using intersections of GenBank data, such as nematode sequences excluding C. elegans and S. stercoralis. This allows examination of sequences in specific phylogenetic distributions (Wheeler et al. 2001). Homologies were reported for e-value scores of 1e -05 and better. TRANSLATE was used to translate contigs for ORF analysis (S. Eddy, unpubl.).

Comparison of S. stercoralis and C. elegans Stage-Specific Transcripts

To examine shared gene expression patterns between nematodes, all 1342 L1-specific and 1573 L3i-specific S. stercoralis clusters were compared by BLAST to 489 nondauer-specific and 328 dauer-specific C. elegans genes (Jones et al. 2001). Additionally, 178 L1-biased clusters and 83 L3i-biased clusters from S. stercoralis with significant stage-biased expression based on sample size were selected using a pairwise test (Audic and Claverie 1997). Null hypotheses about the distribution of matches between data sets were tested using the χ2 statistic with one or three degrees of freedom as appropriate (Steel and Torrie 1960). Comparisons used BLASTX to match cluster nucleotide sequences to C. elegans gene translations in Wormpep v.54 at 1e-05, 1e-15, and 1e-30. SAGE tag sequences were used only as a means of identifying C. elegans genes (Jones et al. 2001), and were not used in sequence comparisons to S. stercoralis.

Functional Assignments

Clusters were assigned putative functional categorization as described (McCarter et al. 2003) using InterProScan v.3.1(ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/unix/iprscan), InterPro domains (11/08/02; InterProScan; Apweiler et al. 2001; Zdobnov and Apweiler 2001), InterPro to GO mappings, and Gene Ontology categorization (go_200211_assocdb.sql; The Gene Ontology Consortium 2000). Mappings are stored in a MySQL database and displayed using AmiGo (11/25/02; www.godatabase.org/cgi-bin/go.cgi). Clusters were assigned by enzyme commission number to metabolic pathways using the KEGG database (IUBMB 1992; Bono et al. 1998; Kanehisa and Goto 2000). To identify cases where S. stercoralis homologs in C. elegans have been surveyed for knockout phenotype using RNAi, Wormpep BLAST matches were cross-referenced to a list of all 7212 available C. elegans RNAi experiments (6107 genes; 5/5/2002; www.wormbase.org). For each S. stercoralis cluster, only the highest-scoring C. elegans match was considered.

Supplemental Data

The following files are available online: Table 1, most conserved nematode genes between S. stercoralis and C. elegans; Table 2, complete list of C. elegans RNAi phenotypes for genes with S. stercoralis homologs; Table 3, classification of C. elegans RNAi phenotypes for genes with S. stercoralis homologs; Table 4, S. stercoralis Gene Ontology mappings: (A) biological process, (B) cellular component, (C) molecular function; Table 5, comparison of Gene Ontology mappings among nematode species. Figure 1, distribution of contigs by size of longest ORF; Figure 2, histogram for S. stercoralis Nemagene v2.0 clustering showing the distribution of clusters by EST origin in L1or L3i.

Acknowledgments

S. stercoralis EST sequencing at Washington University was supported by NIH-NIAID research grant AI 46593 to R.W. J.M. was supported by a Helen Hay Whitney/Merck Fellowship. We thank all members of the GSC's EST group, Barry Shortt for assistance with statistics, and the reviewers for their improvements to the manuscript. J.P.M. and B.C. are employees and equity holders of Divergence Inc; this research was not company funded.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.1524804.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org. EST sequences are available from GenBank, EMBL, and DDJB under the accession numbers AW495499–AW496706, AW587864–AW588186, AW588989–AW589121, BE028808–BE030358, BE223–115–BE224723, BE579014–BE582028, BF014868–BF015393, BG224323–BG227958, and BI772815–BI773227. The sequences are also available at www.nematode.net.]

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler, R., Attwood, T.K., Bairoch, A., Bateman, A., Birney, E., Biswas, M., Bucher, P., Cerutti, L., Corpet, F., Croning, M.D., et al. 2001. The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 37-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, F.T., Bhopale, V.M., Holt, D., Smith, G., and Schad, G.A. 1998. Developmental switching in the parasitic nematode Strongyloides stercoralis is controlled by the ASF and ASI amphidial neurones. J. Parasitol. 84: 691-695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic, S. and Claverie, J.M. 1997. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 7: 986-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter, M. 2000. Genes and genomes of Necator americanus and related hookworms. Int. J. Parasitol. 30: 347-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter, M.L., De Ley, P., Garey, J.R., Liu, L.X., Scheldeman, P., Vierstraete, A., Vanfleteren, J.R., Mackey, L.Y., Dorris, M., Frisse, L.M., et al. 1998. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature 392: 71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter, M., Aslett, M., Guiliano, D., and Daub, J. 1999. Parasitic helminth genomics. Filarial Genome Project. Parasitology 118: S39-S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter, M.L., Daub, J., Guiliano, D., Parkinson, J., Whitton, C., and Filarial Genome Project. 2002. The Brugia malayi genome project: Expressed sequence tags and gene discovery. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96: 7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono, H., Ogata, H., Goto, S., and Kanehisa, M. 1998. Reconstruction of amino acid biosynthesis pathways from the complete genome sequence. Genome Res. 8: 203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Davis, C.I. and Hartl, D.L. 2002. Genome evolution and developmental constraint in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 728-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. 1998. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science 282: 2012-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J., Lee, C.M., and Changchan, C.S. 1994. Duodenal Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Endoscopy 26: 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conraths, F.J., Hirzmann, J., Hebom, G., and Zahner, H. 1997. Expression of the microfilarial sheath protein 2 (shp2) of the filarial parasites Litomosoides sigmodontis and Brugia malayi. Exp. Parasitol. 85: 241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, G.N. 1992. Molecular and biochemical aspects of nematode collagens. J. Parasitol. 78: 1-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub, J., Loukas, A., Pritchard, D.I., and Blaxter, M. 2000. A survey of genes expressed in adults of the human hookworm, Necator americanus. Parasitology 120: 171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautova, M., Rosso, M.N., Abad, P., Gommers, F.J., Bakker, J., and Smant, G. 2001. Single pass cDNA sequencing—A powerful tool to analyse gene expression in preparasitic juveniles of the southern root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nematology 3: 129-139. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X., Shields, J., Allen, R., and Hussey, R.S. 2001. Molecular cloning and characterisation of a venom allergen AG5-like cDNA from Meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Parasitol. 30: 77-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, S., Xu, M., and Piessens, W.F. 1992. A cloned antigen for serological diagnosis of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaremia with daytime blood samples. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 56: 269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, S., Zheng, H., Dreyer, G., Xu, M., Watawana, L., Cheng, G., Wang, S., Morin, P., Deng, B., Kurniawan, L., et al. 1994. Evaluation of a recombinant parasite antigen for the diagnosis of limphatic filariasis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 50: 727-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorris, M., Viney, M.E., and Blaxter, M.L. 2002. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the genus Strongyloides and related nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 32: 1507-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, M., Attisano, L., Wrana, J.L., Albert, P.S., Massague, J., and Riddle, D.L. 1993. The daf-4 gene encodes a bone morphogenetic protein receptor controlling C. elegans dauer larva development. Nature 365: 644-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B. and Green, P. 2000. Analysis of expressed sequence tags indicates 35,000 human genes. Nat. Genet. 25: 232-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, B., Hillier, L., Wendl, M.C., and Green, P. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8: 175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M.K., Kostas, S.A., Driver, S.E., and Mello, C.C. 1998. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391: 806-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, A.G., Kamath, R.S., Zipperlen, P., Martinez-Campos, M., Sohrmann, M., and Ahringer, J. 2000. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408: 325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. 2000. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25: 25-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genta, R.M. 1988. Predictive value of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the serodiagnosis of strongyloidiasis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 89: 391-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, L.L., Albert, P.S., and Riddle, D.L. 1990. daf-1, a C. elegans gene controlling dauer larva development, encodes a novel receptor protein kinase. Cell 61: 635-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetinck, S. and Waterston, R.H. 1994. The Caenorhabditis elegans muscle-affecting gene unc-87 encodes a novel thin filament-associated protein. J. Cell. Biol. 127: 79-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonczy, P., Echeverri, C., Oegema, K., Coulson, A., Jones, S.J., Copley, R.R., Duperon, J., Oegema, J., Brehm, M., Cassin, E., et al. 2000. Functional genomic analysis of cell division in C. elegans using RNAi of genes on chromosome III. Nature 408: 331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.N. and Viney, M.E. 2001. Postgenomic nematode parasitology. Int. J. Parasitol. 31: 879-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.S.t., Centa, R.M., Gam, A., London, W.T., and Neva, F.A. 1984. Experimental disseminated strongyloidiasis in Erythrocebus patas. I. Pathology. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33: 431-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawdon, J.M. and Schad, G.A. 1991. Albumin and a dialyzable serum factor stimulate feeding in vitro by third-stage larvae of the canine hookworm Ancylostoma caninum. J. Parasitol. 77: 587-591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawdon, J.M., Jones, B.F., Hoffman, D.R., and Hotez, P.J. 1996. Cloning and characterization of Ancylostoma-secreted protein. A novel protein associated with the transition to parasitism by infective hookworm larvae. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 6672-6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, D.R., Nolan, T.J., Schad, G.A., Lustigman, S., and Abraham, D. 2002. Immunoaffinity-isolated antigens induce protective immunity against larval Strongyloides stercoralis in mice. Exp. Parasitol. 100: 112-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, T. and Horvitz, H.R. 1997. Mutations that perturb vulval invagination in C. elegans. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 62: 353-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, T., Hartwieg, E., and Horvitz, H.R. 1999. sqv mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans are defective in vulval epithelial invagination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 968-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.A., Hunter, C.P., Tsung, B.T., Tucker-Kellogg, G., and Brown, E.L. 2000. Genomic analysis of gene expression in C. elegans. Science 290: 809-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, L.D., Lennon, G., Becker, M., Bonaldo, M.F., Chiapelli, B., Chissoe, S., Dietrich, N., DuBuque, T., Favello, A., Gish, W., et al. 1996. Generation and analysis of 280,000 human expressed sequence tags. Genome Res. 6: 807-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hresko, M.C., Schriefer, L.A., Shrimankar, P., and Waterston, R.H. 1999. Myotactin, a novel hypodermal protein involved in muscle-cell adhesion in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell. Biol. 146: 659-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, A.S., Kichenin, K., and Selkzer, P.M. 2002. Suppression of selected acetylcholinesterase expression in Nippostrongylus brasiliensis by RNA interference. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122: 91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igra-Siegman, U., Kapila, R., Sen, P., Zaminski, Z.C., and Louria, D.B. 1981. Syndrome of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 3: 397-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUBMB. 1992. Enzyme nomenclature: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Johnstone, I.L. 1994. The cuticle of the nematode C. elegans: A complex collagen structure. Bioessays 16: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, I.L. and Barry, D.J. 1996. Temporal reiteration of a precise gene expression pattern during nematode development. EMBO J. 15: 3633-3639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.J., Riddle, D.L., Pouzyrev, A.T., Velculescu, V.E., Hillier, L., Eddy, S.R., Stricklin, S.L., Baillie, D.L., Waterston, R., and Marra, M.A. 2001. Changes in gene expression associated with developmental arrest and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 11: 1346-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.S., Fraser, A.G., Dong, Y., Poulin, G., Durbin, R., Gotta, M., Kanapin, A., Le Bot, N., Moreno, S., Sohrmann, M., et al. 2003. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa, M. and Goto, S. 2000. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 27-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K., Lund, J., Kiraly, M., Duke, K., Jiang, M., Stuart, J.M., Eizinger, A., Wylie, B.N., and Davidson, G.S. 2001. A gene expression map for Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 293: 2087-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klion, A.D., Vijaykumar, A., Oei, T., Martin, B., and Nutman, T.B. 2003. Serum immunoglobulin G4 antibodies to the recombinant antigen, Ll-SXP-1, are highly specific for Loa loa infection. J. Infect. Dis. 187: 128-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, P.L., Albert, P.S., and Riddle, D.L. 1995. Genes that regulate both development and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139: 1567-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A.D., Yang, J., and Kraemer, J.M. 1993. Molecular and genetic analyses of the Caenorhabditis elegans dpy-2 and dpy-10 collagen genes: A variety of molecular alternations affect organismal morphology. Mol. Biol. Cell 4: 803-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K., Dorman, J.B., Rodan, A., and Kenyon, C. 1997. daf-16: An HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 278: 1319-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok, J.B. and Massey, H.C.J. 2002. Transgene expression in Strongyloides stercoralis following gonadal microinjection of DNA constructs. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119: 279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, P.M., Boston, R., Ashton, F.T., and Schad, G.A. 2000. The neurons of class ALD mediate thermotaxis in the parasitic nematode, Strongyloides stercoralis. Int. J. Parasitol. 30: 1115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, I., Kohara, Y., Yamamoto, M., and Sugimoto, A. 2001. Large-scale analysis of gene function in Caenorhabditis elegans by high-throughput RNAi. Curr. Biol. 11: 171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra, M.A., Kucaba, T.A., Hillier, L.W., and Waterston, R.H. 1999. High-throughput plasmid DNA purification for 3 cents per sample. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Jr., H.C., Ball, C.C., and Lok, J.B. 2001. PCR amplification of putative gpa-2 and gpa-3 orthologs from the (A+T)-rich genome of Strongyloides stercoralis. Int. J. Parasitol. 31: 377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, R. and Brewton, R.G. 1993. New members of the collagen superfamily. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5: 883-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarrey, J.R. and Williams, S.A. 1994. Construction of cDNA libraries from limited amounts of material. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 5: 34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter, J., Abad, P., Jones, J.T., and Bird, D. 2000. Rapid gene discovery in plant parasitic nematodes via expressed sequence tags. Nematology 2: 719-731. [Google Scholar]

- McCarter, J., Dautova Mitreva, M., Martin, J., Dante, M., Wylie, T., Rao, U., Pape, D., Bowers, Y., Theising, B., Murphy, C.V., et al. 2003. Analysis and functional classification of transcripts from the nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Genome Biol. 4: R26: 1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarter, J.P., Clifton, S., Bird, D.M., and Waterston, R.H. 2002. Nematode gene sequences, update for June 2002. J. Nematol. 34: 71-74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, T.A., Ramachandran, S., Gam, A.A., Neva, F.A., Lu, W., Saunders, L., Williams, S.A., and Nutman, T.B. 1996. Identification of novel sequences and codon usage in Strongyloides stercoralis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 79: 243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, J., Mitreva, M., Hall, N., Blaxter, M., and McCarter, J.P. 2003. 400000 nematode ESTs on the Net. Trends Parasitol. 4922: 132-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popeijus, H., Blok, V.C., Cardle, L., Bakker, E., Phillips, M.S., Helder, J., Smant, G., and Jones, J.T. 2000. Analysis of genes expressed in second stage juveniles of the potato cyst nematodes Globodera rostochiensis and G. pallida using the expressed sequence tag approach. Nematology 2: 567-574. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, D.I., Brown, A., Kasper, G., McElroy, P., Loukas, A., Hewitt, C., Berry, C., Fullkrug, R., and Beck, E. 1999. A hookworm allergen which strongly resembles calreticulin. Parasite Immunol. 21: 439-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quackenbush, J., Cho, J., Lee, D., Liang, F., Holt, I., Karamycheva, S., Parvizi, B., Pertea, G., Sultana, R., and White, J. 2001. The TIGR gene indices: Analysis of gene transcript sequences in highly sampled eukaryotic species. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 159-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennex, D., Hemmings, B.A., Hofsteenge, J., and Stone, S.R. 1991. cDNA cloning of porcine brain prolyl endopeptidase and identification of the active-site seryl residue. Biochemistry 30: 2195-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, D.L. and Albert, P.S. 1997. Genetic and environmental regulation of dauer larva development. In C. elegans II (eds. L.D. Riddle et al.), pp. 739-768. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, New York. [PubMed]

- Rokeach, L.A., Zimmerman, P.A., and Unnasch, T.R. 1994. Epitopes of the Onchocerca volvulus RAL1antigen, a member of the calreticulin family of proteins, recognized by sera from patients with onchocerciasis. Infect. Immun. 62: 3696-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad, G.A. 1990. Morphology and life history of Strongyloides stercoralis. In Strongyloidiasis: A major roundworm infection of man (ed. I.D. Grove), pp. 85-104. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Scholl, E.H., Thorne, J.L., McCarter, J.P., and Bird, D.M. 2003. Horizontally transferred genes in plant-parasitic nematodes: A high-throughput genomic approach. Genome Biol. 4: R39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, M.E. and Blaxter, M.L. 1990. Cuticular proteins of Brugia filarial parasites. Acta Trop. 47: 373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, M.E., Nielsen, L., Kelly, C., Partono, F., Sayers, G., and Maizels, R.M. 1989. Identification, synthesis and immunogenicity of cuticular collagens from the filarial nematodes Brugia malayi and Brugia pahangi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 32: 229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, M.E., Yazdanbakhsh, M., Freedman, D., Blaxter, M.L., Cookson, E., Jenkins, R.E., and Williams, S.A. 1991. A proline-rich structural protein of the surface sheath of larval Brugia filarial nematode parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 11002-11008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, A.A. and Berk, L.S. 2001. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33: 1040-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, A.A., Koenig, N.M., Sinensky, M., and Berk, L.S. 1997. Strongyloides stercoralis: Identification of antigens in natural human infections from endemic areas of the United States. Parasitol. Res. 83: 655-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, A.A., Stanley, S.C., and Berk, L.S. 2000. A cDNA encoding the highly immunodominant antigen of Strongyloides stercoralis: Gamma-subunit of isocitrate dehidrogenase (NAD+). Parasitol. Res. 86: 279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor, W.G. and Cochran, G.W. 1967. Statistical methods, 6th ed. pp. 20-31, pp. 59-119. The Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA.

- Steel, R.G.D. and Torrie, J.H. 1960. Principles and procedures of statistics, pp. 346-351. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Tetteh, K.K., Loukas, A., Tripp, C., and Maizels, R.M. 1999. Identification of abundantly expressed novel and conserved genes from the infective larval stage of Toxocara canis by an expressed sequence tag strategy. Infect. Immun. 67: 4771-4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin, P.E., Lilley, C.J., and Atkinson, H.J. 2002. Ingestion of double-stranded RNA by preparasitic juvenile cyst nematodes leads to RNA interference. Molec. Plant Microbe Interacts. 15: 747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanfleteren, J.R. 1993. Oxidative stress and ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. J. 292: 605-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viney, M.E. 1999. Exploiting the life cycle of Strongyloides ratti. Parasitol. Today 15: 231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.L., Church, D.M., Lash, A.E., Leipe, D.D., Madden, T.L., Pontius, J.U., Schuler, G.D., Schriml, L.M., Tatusova, T.A., Wagner, L., et al. 2001. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks, S.R., Yeh, R.T., Gish, W.R., Waterston, R.H., and Plasterk, R.H. 2001. Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat. Genet. 28: 160-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, M., Matsuda, S., Nakazawa, M., and Arizono, N. 1991. Species-specific differences in heterogonic development of serially transferred free-living generations of Strongyloides planiceps and Strongyloides stercoralis. J. Parasitol. 77: 592-594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahner, H., Hobom, G., and Stirm, S. 1995. The microfilarial sheath and its proteins. Parasitol. Today 11: 116-120. [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov, E.M. and Apweiler, R. 2001. InterProScan—An integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17: 847-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEB SITE REFERENCES

- http://blast.wustl.edu; Gish, W. 2002, WU BLAST Web site.

- ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/unix/iprscan; InterProScan.

- http://www.geneontology.org/; Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium.

- http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/; Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

- http://www.godatabase.org/cgi-bin/go.cgi; AmiGO.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbEST/; NCBI expressed sequence tags database.

- http://nematode.net/; Nematode EST data Genome Sequencing Center.