Background: Cells undergoing apoptosis are selectively recognized and engulfed by phagocytes.

Results: A Drosophila endoplasmic reticulum protein named DmCaBP1 was externalized upon apoptosis, bound to both apoptotic cells and phagocytes, and enhanced phagocytosis.

Conclusion: DmCaBP1 connects apoptotic cells and phagocytes to promote phagocytosis.

Significance: We are first to report that a protein residing in the endoplasmic reticulum plays a role in apoptotic cell clearance as a tethering molecule.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Calcium Binding Proteins, Drosophila, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Phagocytosis

Abstract

To elucidate the actions of Draper, a receptor responsible for the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells in Drosophila, we isolated proteins that bind to the extracellular region of Draper using affinity chromatography. One of those proteins has been identified to be an uncharacterized protein called Drosophila melanogaster calcium-binding protein 1 (DmCaBP1). This protein containing the thioredoxin-like domain resided in the endoplasmic reticulum and seemed to be expressed ubiquitously throughout the development of Drosophila. DmCaBP1 was externalized without truncation after the induction of apoptosis somewhat prior to chromatin condensation and DNA cleavage in a manner dependent on the activity of caspases. A recombinant DmCaBP1 protein bound to both apoptotic cells and a hemocyte-derived cell line expressing Draper. Forced expression of DmCaBP1 at the cell surface made non-apoptotic cells susceptible to phagocytosis. Flies deficient in DmCaBP1 expression developed normally and showed Draper-mediated pruning of larval axons, but a defect in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in embryos was observed. Loss of Pretaporter, a previously identified ligand for Draper, did not cause a further decrease in the level of phagocytosis in DmCaBP1-lacking embryos. These results collectively suggest that the endoplasmic reticulum protein DmCaBP1 is externalized upon the induction of apoptosis and serves as a tethering molecule to connect apoptotic cells and phagocytes for effective phagocytosis to occur.

Introduction

The prompt and effective removal of cells that have become unnecessary or harmful plays an important role in the development and tissue homeostasis (1, 2). Such altered own cells are induced to undergo apoptosis and become susceptible to apoptosis-dependent phagocytosis (2, 3). It is presumed that phagocytes find and engulf apoptotic cells using receptors that recognize specific ligands present at the surface of target cells or soluble molecules connecting apoptotic cells and phagocytes (4–6). It is therefore essential to identify and characterize the receptors and corresponding ligands/soluble molecules to fully understand the mechanism and meanings of this biological phenomenon.

There are two partly overlapping signaling pathways for the induction of phagocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans, and one pathway is governed by a receptor called CED-1 (7–11). CED-1 is a single-path membrane protein containing atypical EGF-like repeats in its extracellular region (11). There are counterparts of CED-1 in other species (12), namely Draper in Drosophila (13, 14), Jedi in mice (15), and MEGF10 in humans (16), and their involvement in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells has been shown. However, it is almost obscure how CED-1 and its counterparts are activated for the induction of engulfment in phagocytes. We previously identified a protein we named Pretaporter as a ligand for Draper, a Drosophila homologue of CED-1, by affinity chromatography (17). Pretaporter is a protein residing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)3 and seems to be relocated to the cell surface after the induction of apoptosis (17). While isolating Pretaporter, we noticed the presence of another protein that bound to and eluted from the Draper-conjugated matrix. In this study, we identified and characterized this protein in terms of its involvement in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly Stocks

The following fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) and used in this study: w1118, y1 w1118, w*; P{sqh-EYFP-ER}3 (18), y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}DmCaBP1EY12345, and w*; wgSp-1/CyO; ry506 Sb1 P{Δ2–3}99B/TM6B, Tb+. The Draper-null line w; Sp/SM1; drpr Δ5/TM6B Sb Tb (13) was provided by M. Freeman. To generate mutated alleles of DmCaBP1, y1 w67c23; P{EPgy2}DmCaBP1EY12345 flies were first mated with w1118 six times to remove possible second-site mutations and then with w*; wgSp-1/CyO; ry506 Sb1 P{Δ2–3}99B/TM6B, Tb+ for the mobilization of the P-element by the action of Δ2–3 transposase. We screened about 100 candidate excision events by Western blotting with anti-calcium-binding protein 1 of Drosophila melanogaster (DmCaBP1) antibody and isolated flies with no DmCaBP1 expression. A fly line obtained after precise excision of P-element, DmCaBP1H20, was used as a DmCaBP1-expressing control. Other fly lines used were generated through mating of the existing lines.

Cell Culture

The cell lines l(2)mbn, established from larval hemocytes, and embryonic-cell derived S2 were maintained at 25 °C with Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, as described previously (14). l(2)mbn cells were incubated with 20-hydroxyecdysone (Sigma-Aldrich) (1 μm) for 48 h before being used in an assay for phagocytosis. To induce apoptosis, S2 cells were incubated in the presence of cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) (2 μg/ml) for 24 h, as described previously (14). Apoptotic S2 cells were stained with the DNA-binding fluorochrome Hoechst 33342 (1 μm) and by TUNEL (Millipore) for the examination of chromatin condensation and DNA cleavage, respectively, according to standard protocols. S2 cells were treated with Escherichia coli-derived LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) (50 μg/ml) at 25 °C for 4 h, essentially as reported by Cornwell and Kirkpatrick (19). To fractionate externalized DmCaBP1, culture media of apoptotic S2 cells were centrifuged at varying levels of forces according to published procedures (20), and the resulting pellets and supernatants at each centrifugation were analyzed by Western blotting. RNAi using double-stranded RNA synthesized in vitro was done as described previously (14).

Antibody and Immunochemistry

The generation and use of anti-Draper (14), anti-Croquemort (14), anti-focal adhesion kinase (21), anti-Pretaporter (17), and anti-Calreticulin (22, 23) antibodies were reported previously. Anti-Drosophila DmCaBP1 antibody was raised by immunizing rats with recombinant DmCaBP1 expressed in E. coli as a protein fused to GST. Anti-GST mAb was purchased from Millipore, and anti-maltose-binding protein (MBP) antibody was from New England Biolabs. To examine the expression of DmCaBP1 during development, flies at various developmental stages were homogenized in a buffer consisting of 63 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2.5% (w/v) SDS, and 2.5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, and resulting extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. For the examination of the binding of DmCaBP1 to apoptotic cells and phagocytes, we incubated cycloheximide-treated S2 cells and l(2)mbn cells with GST-fused DmCaBP1 and MBP-fused DmCaBP1, respectively, in PBS supplemented with 0.88 mm CaCl2 at 4 °C for 1 h, and the cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with the same buffer, and lysed as described above. The lysates were then analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GST and anti-MBP antibodies. Western blotting using alkaline phosphatase- or HRP-labeled secondary antibody was carried out as described previously (14). Immunocytochemical detection of DmCaBP1 was performed as described in our previous paper (17). To immunoprecipitate DmCaBP1, cell lysates or culture media were incubated with anti-DmCaBP1 antiserum, and proteins bound to the antibody were recovered using protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare).

Assays for Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis reactions in vitro with l(2)mbn cells as phagocytes were carried out as described previously (14). To prepare latex beads coated with DmCaBP1, FITC-labeled latex beads (Φ = 1.7 μm, Polysciences) were incubated with GST-fused DmCaBP1 in the presence of a cross-linking reagent (17). To obtain non-apoptotic cells with surface-expressed DmCaBP1, nucleotide sequences of DmCaBP1 cDNA were altered so that the ER retention motif was replaced by the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchoring signal, and S2 cells were transfected with the resulting DNA coding for glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored DmCaBP1, as done for Pretaporter (17). An analysis of phagocytosis with dispersed embryonic cells was conducted as described (21). Briefly, Drosophila embryos at stage 16 were homogenized, and cells were collected by filtration, fixed with paraformaldehyde and methanol, membrane-permeabilized with Triton X-100, and incubated with swine serum for blocking. The cells were then cytochemically analyzed with anti-Croquemort antibody to identify hemocytes and by TUNEL to identify apoptotic cells, and cells positive for both signals were considered embryonic hemocytes that had phagocytosed apoptotic cells. A microscopic field containing 100 or more cells positive for Croquemort expression was examined to determine the level of phagocytosis. The mean ± S.D. of the results from five microscopic fields was obtained in each experiment.

Solid-phase Assay for Protein-Protein Interaction

GST-fused recombinant proteins (2.5 pmols) were incubated in 96-well culture containers, the surface of which had been coated with MBP-fused recombinant proteins, at 4 °C overnight. The wells were then washed and successively supplied with anti-GST antibody and anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated with HRP followed by a colorimetric reaction. Each test protein was analyzed in quintuplicate.

Other Materials and Methods

The MS analysis was carried out essentially as reported previously (17). In brief, protein bands separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with silver or Coomassie Brilliant Blue were excised and in-gel-digested with trypsin or Achromobacter protease I. The resulting peptides were then subjected to LC/MS/MS, and proteins were identified by the MS/MS ion search of Mascot Software (Matrix Science, London, UK). The pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk was obtained from R&D Systems and used at 20 μm. Brefeldin A, 3-methyladenine, and MG-132 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and added to cell cultures at the concentrations effectively used for Drosophila cells: 30 μg/ml (24), 10 mm (25), and 10 μm (26, 27), respectively. An extracellular region of Draper fused to GST at the C terminus was expressed in Sf21 cells using a baculovirus-based vector and affinity purified as described previously (17). Other GST-fused and MBP-fused recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli using the pGEX-KG (GE Healthcare) and pMAL-c4X (New England Biolabs) vectors, and purified to homogeneity using glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) and amylose resin (New England Biolabs), respectively, according to the manufacturers' instructions. Using pGEX-KG, proteins of interest were fused to GST at the N terminus, and with pMAL-c4X, vector proteins were fused to MBP at the N terminus and to β-gal at the C terminus. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was carried out according to a standard protocol using the following DNA oligomers as primers in PCR: 5′-CCCGGAGTGAAGGATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTTGCTGTGCGTCAAG-3′ (reverse) for attacin-A mRNA and 5′-GACGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAACGCGGTTCTGCATGAG-3′ (reverse) for mRNA of ribosomal protein 49. An analysis of axon pruning was carried out as described previously (28).

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data from quantitative analyses are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of the results from at least three independent experiments, unless otherwise stated in the text. Other data are representative of at least three independent experiments that yielded similar results. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant and are indicated in the figures.

RESULTS

Identification and Expression Profile of DmCaBP1

We previously isolated proteins that bind to the extracellular region of Draper and identified a protein we named Pretaporter as a ligand for Draper (17). There was another protein band that was retained on and eluted from the Draper-conjugated Sepharose matrix (Fig. 1A). We analyzed this band by MS (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1) and found it to be an as-yet uncharacterized protein called DmCaBP1 (29). The amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence of cDNA (AY061349.1) shows that DmCaBP1 consists of 433 amino acid residues containing the signal peptide at the N terminus, two thioredoxin-like domains, and the ER retention motif at the C terminus (Fig. 1B), suggesting it to be a protein residing in the ER. An ELISA-like solid-phase assay revealed that DmCaBP1 directly binds to Draper (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Identification and expression pattern of DmCaBP1. A, whole-cell lysates of S2 cells were subjected to affinity chromatography using Sepharose conjugated with the extracellular region of Draper fused to GST (Draper-GST) or GST alone. The bound materials were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by staining with silver. The arrowhead points to the position of a band that was subsequently identified to be DmCaBP1. B, the entire amino acid sequence of DmCaBP1 deduced from the nucleotide sequence of cDNA is shown with the positions of peptides identified in the MS analysis (underlined) as well as predicted domain structures. The numbering denotes amino acid positions with the N terminus as 1. The boxed, colored (blue and red), and bolded/shaded regions indicate the signal peptide, the thioredoxin-like domains, and the ER-retention motif, respectively. Refer to supplemental Fig. S1 for more information. C, the binding of DmCaBP1 to Draper was examined by an ELISA-like solid-phase assay. GST-fused Draper or GST alone was incubated in a culture container that had been coated with the indicated MBP-fused proteins, and the amount of GST proteins remaining in the container after washing was determined by an immunochemical reaction. The mean ± S.D. of the data (n = 5) from one of two independent experiments with similar results are presented. D, lysates of whole animals at the indicated developmental stages were analyzed by Western blotting for the level of DmCaBP1. E, dispersed embryonic cells (stage 16) of a fly line that expresses YFP fused to the ER-retention motif KDEL at the C terminus as a marker for ER-residing proteins (ER marker) were immunocytochemically analyzed using anti-DmCaBP1 antibody for the subcellular localization of DmCaBP1. Phase-contrast and fluorescence views of the same microscopic fields are shown as laterally aligned panels. The inset shows a magnified view of a cell pointed by an arrowhead in each panel. Scale bar = 20 μm.

When the level of DmCaBP1 was analyzed with flies at various developmental stages by Western blotting, this ER protein continued to be expressed from embryos through adults (Fig. 1D). To determine the subcellular localization and cell type-specificity of DmCaBP1, we immunocytochemically analyzed dispersed embryonic cells that artificially expressed a marker protein for the ER. The results showed that the localization of DmCaBP1 overlaps with that of a marker present in the lumen of the ER and that almost all cells in stage-16 embryos gave positive signals (Fig. 1E), indicating a ubiquitous expression of DmCaBP1 in the ER, at least for this developmental stage.

Apoptosis-dependent Externalization of DmCaBP1

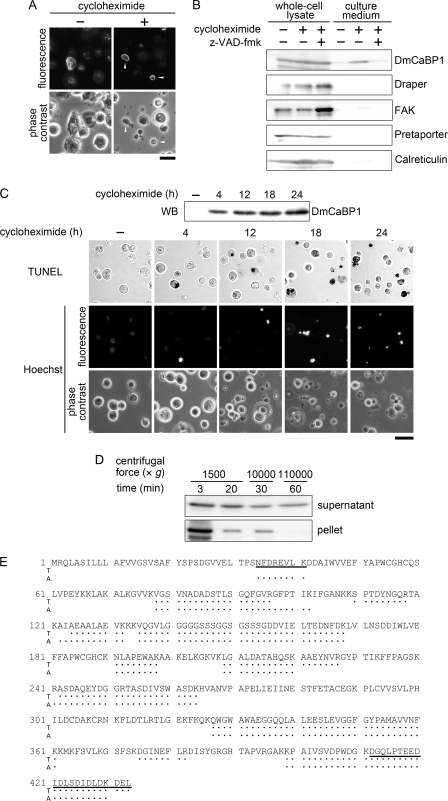

Because DmCaBP1 was found to be a protein binding to the extracellular region of Draper, we next examined its possible externalization. We first immunocytochemically analyzed cultured cells before and after the induction of apoptosis. The treatment of cells with cycloheximide, which induces typical apoptosis (14), seemed to change the subcellular distribution of DmCaBP1 from the ER to the area near the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A). We next examined the presence of DmCaBP1 in the culture medium by Western blotting and observed a signal with migration in a gel almost the same as the intracellular one (Fig. 2B). This was not the case for Draper and focal adhesion kinase, a membrane-integrated and a soluble cytoplasmic protein, respectively, and the DmCaBP1 signal in the medium disappeared when apoptosis was induced in the presence of z-VAD-fmk, a caspase inhibitor. We showed previously that other ER proteins, Calreticulin (23) and Pretaporter (17), exist at the surface of apoptotic cells. We thus examined if these proteins are also released from apoptotic cells. However, the results indicated that they are not purged from apoptotic S2 cells as efficiently as DmCaBP1 (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that DmCaBP1 is preferentially externalized after the induction of apoptosis. When a time-course experiment was carried out, DmCaBP1 became detectable in culture supernatants somewhat prior to a couple of biochemical events typical of apoptosis: the cleavage of nuclear DNA (examined by TUNEL) and the condensation of chromatin (examined by staining with Hoechst 33342) (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Apoptosis-dependent externalization of DmCaBP1. A, S2 cells before and after the treatment with cycloheximide were immunocytochemically analyzed for the subcellular localization of DmCaBP1. Fluorescence and phase-contrast views of the same microscopic fields are shown as vertically aligned panels. The arrowheads indicate the cells where the localization of DmCaBP1 has been altered. Scale bar = 10 μm. B, S2 cells were treated with cycloheximide in the absence and presence of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk, and their whole-cell lysates as well as the culture media were analyzed by Western blotting for the levels of the indicated proteins. Only portions of the gel containing the signals derived from the corresponding proteins are shown. FAK, focal adhesion kinase. C, S2 cells were maintained in the presence of cycloheximide for the indicated periods of time. The culture media were analyzed for the level of DmCaBP1 by Western blotting (WB), whereas the cells were subjected to cytochemical analyses for the occurrence of DNA cleavage (TUNEL) and chromatin condensation (Hoechst). In the analysis of DNA cleavage, TUNEL-positive nuclei are shown in black. In the analysis of chromatin condensation, fluorescence and phase-contrast views of the same microscopic field are shown as vertically aligned panels. Scale bar = 20 μm. D, culture media of cycloheximide-treated S2 cells were first centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 3 min, and the resulting supernatants were recentrifuged at 1,500 × g for 20 min. Supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatants were recentrifuged at 110,000 × g for 60 min. Supernatants and pellets obtained after each centrifugation were analyzed by Western blotting for the presence of DmCaBP1. E, DmCaBP1 present in the culture media of cycloheximide-treated S2 cells and whole-cell lysates of normal S2 cells was immunoprecipitated with anti-DmCaBP1 antibody and subjected to the MS analysis after digestion with trypsin (T) or Achromobacter protease I (A). Peptides identified in both DmCaBP1 preparations are shown with dots along with the amino acid sequence of DmCaBP1 deduced from the nucleotide sequence of its cDNA. Peptides including the presumed N terminus and C terminus of mature DmCaBP1 are underlined. Refer to supplemental Fig. S3 for more information.

A recent report shows that an aminopeptidase residing in the ER is secreted from macrophages upon treatment with LPS and IFN-γ in a manner inhibitable by brefeldin A, suggesting the involvement of inflammatory signaling and vesicle transport (30). We conducted a series of experiments to examine an analogy in the mechanism of externalization between DmCaBP1 and this aminopeptidase. S2 cells were incubated in the presence of LPS, and cell lysates and culture media were analyzed for the presence of DmCaBP1. The results showed that LPS induced the expression of mRNA of attacin-A, an antimicrobial peptide, in S2 cells but not the externalization of DmCaBP1 (supplemental Fig. S2A). To examine the involvement of vesicle transport, autophagy, and proteasomes in the apoptosis-dependent externalization of DmCaBP1, we treated cells with cycloheximide together with brefeldin A, 3-methyladenine, and MG-132, respectively. However, the externalization of DmCaBP1 was not influenced by the presence of either substance (supplemental Fig. S2B). These results suggested that the mechanism for externalization differs between DmCaBP1 and ER-residing aminopeptidase.

We next examined if externalized DmCaBP1 is associated with membrane vesicles. Culture media of apoptotic S2 cells were subjected to differential centrifugation, and supernatants and pellets after each centrifugation were analyzed for the presence of DmCaBP1 by Western blotting. The results showed that supernatants but not pellets, which should contain membranous materials, after final centrifugation gave signals, suggesting that externalized DmCaBP1 is not contained in membrane vesicles (Fig. 2D). We then examined possible truncation of DmCaBP1 during externalization. For this purpose, we conducted the MS analysis of DmCaBP1 immunoprecipitated from lysates of normal S2 cells as well as culture media of apoptotic S2 cells. We first analyzed trypsin-digested DmCaBP1 and identified a peptide spanning the presumed C terminus (Fig. 2E). This peptide existed in the samples derived from both intracellular and externalized DmCaBP1, and was among abundant peptides observed (supplemental Fig. S3A). We concluded that KDEL is the C-terminal sequence of mature DmCaBP1 and that this region does not undergo cleavage during externalization of DmCaBP1. By contrast, a peptide corresponding to the N terminus appeared undetectable in the analysis. We thus used another protease, Achromobacter protease I, to digest DmCaBP1 and similarly analyzed the resulting peptides. In this attempt, we observed a peptide corresponding to the amino acid positions 34–41 (Fig. 2E), and the amount of this peptide was near comparable with those of other peptides in both samples (supplemental Fig. S3B). We found no peptides located closer to the N terminus of nascent DmCaBP1 than this peptide. We thus presumed that NFDR is the N-terminal sequence of mature DmCaBP1 and that the N-terminal 33-amino acid region including the signal peptide is chopped off during the maturation of nascent DmCaBP1. Collectively, DmCaBP1 is unlikely to undergo truncation upon apoptosis-dependent externalization.

Involvement of DmCaBP1 in Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells

We next examined if externalized DmCaBP1 binds to apoptotic cells and/or phagocytes. For this purpose, we incubated cultured cells with GST- or MBP-tagged DmCaBP1 and determined cell-bound DmCaBP1 by Western blotting. We found that more DmCaBP1 proteins were recovered with either apoptotic S2 cells or hemocyte-derived l(2)mbn cells than the control proteins (Fig. 3A). This indicated that DmCaBP1 binds to both apoptotic cells and phagocytes and suggested a role for this ER protein in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.

FIGURE 3.

Surface DmCaBP1-mediated phagocytosis of latex beads and non-apoptotic cells. A, cycloheximide-treated S2 cells (left panel) and l(2)mbn cells (right panel) were incubated with recombinant DmCaBP1 proteins fused to GST and MBP, respectively. GST alone and MBP-βgal were included as controls for GST-DmCaBP1 and MBP-DmCaBP1-βgal, respectively. The cells were recovered by centrifugation, and their whole-cell lysates were examined by Western blotting using anti-GST antibody (left panel) or anti-MBP antibody (right panel) together with the input proteins, GST-DmCaBP1/GST (left panel) and MBP-DmCaBP1-βgal/MBP-βgal (right panel). B, latex beads coated with GST-fused DmCaBP1 (GST-DmCaBP1) or GST alone were subjected to an assay for phagocytosis with l(2)mbn cells that had been treated with double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) containing mRNA sequences of the indicated genes, as phagocytes. The level of phagocytosis is shown relative to that of non-coated latex beads, taken as 100. NS, not significant. The mean ± S.D. of the data (n = 6) from one of three independent experiments with similar results are presented. C, S2 cells transfected with DNA for the expression of GPI-anchored DmCaBP1 (GPI-DmCaBP1) or with the vector alone were subjected to an immunofluorescence analysis with anti-DmCaBP1 antibody under a membrane-non-permeabilized condition. Scale bar = 10 μm. D, S2 cells analyzed in B as well as untransfected cells (none) were examined for susceptibility to phagocytosis by l(2)mbn cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of the results from three independent experiments (n = 3 in each experiment).

To test the possibility that externalized DmCaBP1 binds and activates phagocytes, l(2)mbn cells were incubated with a recombinant DmCaBP1 protein, washed, and used in an assay for the phagocytosis of latex beads. We found that the level of phagocytosis by l(2)mbn cells treated with DmCaBP1 did not significantly differ from that by the cells preincubated with a control protein (data not shown). This suggested that DmCaBP1 binds to phagocytes but does not augment their general phagocytic activity.

To examine the effect of DmCaBP1 on phagocytosis mediated by Draper, we analyzed the phagocytosis of DmCaBP1-bound latex beads by l(2)mbn cells. Beads coated with GST-DmCaBP1 were more effectively phagocytosed than those coated with GST alone, and this was abolished when l(2)mbn cells were treated with double-stranded RNA with a sequence corresponding to Draper mRNA (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, forced expression of DmCaBP1 as a membrane-anchor form made non-apoptotic S2 cells susceptible to phagocytosis by l(2)mbn cells (Figs. 3, C and D). These results indicated that DmCaBP1 induces phagocytosis, being present at the surface of target cells. To confirm a role for DmCaBP1 in apoptotic cell clearance in vivo, we generated a fly line deficient in the expression of DmCaBP1 (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4) and analyzed phagocytosis in embryos. The results showed that the level of phagocytosis was lower in embryos of the DmCaBP1-lacking fly line than in a control line (Fig. 4B). The above-described results collectively suggested that DmCaBP1 is released from cells during apoptosis, bridges apoptotic cells and phagocytes, and promotes Draper-dependent phagocytosis.

FIGURE 4.

Involvement of DmCaBP1 in apoptotic cell clearance in Drosophila. A, whole-animal lysates of adult flies generated by the mobilization of P-element were analyzed by Western blotting for the level of DmCaBP1. DmCaBP1H20 and DmCaBP1Δ1 are fly lines obtained through the precise and imprecise excision of P-element in the original fly line, respectively. Refer to supplemental Fig. S4 for more information. B, dispersed cells prepared from stage-16 embryos of DmCaBP1H20 and DmCaBP1Δ1 were examined for the level of phagocytosis. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of the results from three independent experiments (n = 5 in each experiment). C, brains dissected from DmCaBP1H20 and DmCaBP1Δ1 as well as Draper-lacking (drprΔ5) flies at the indicated developmental stages (APF, after pupation formation) were histochemically examined for the existence of γ neuron axons. The arrowheads point to the axons removed during metamorphosis. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Functional Relationship between DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter

The results obtained so far indicated that DmCaBP1 is analogous to Pretaporter, which we previously reported as a ligand for Draper (17). The removal of γ neuron axons, called pruning, of larval mushroom bodies during metamorphosis occurs in a manner dependent on the actions of Draper (28), and Pretaporter does not seem to be involved in this event (17). We found that the pruning of larval axons took place in the absence of DmCaBP1, whereas it was severely impaired in Draper-lacking flies, as observed previously (28) (Fig. 4C). For a more direct examination of the relationship between DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter, we generated a double-mutant fly line that lacks both proteins (Fig. 5A) and analyzed its embryos for the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. We found that the level of phagocytosis by embryonic hemocytes in the double mutant was comparable with that in single mutants for the two genes (Fig. 5B). This suggested that DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter cooperate with each other in the Draper-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in Drosophila embryos.

FIGURE 5.

Functional relationship between DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter. A, lysates of adult flies of the indicated lines were analyzed by Western blotting for the levels of DmCaBP1, Pretaporter, and Draper. The fly line prtpΔ1 is a null-mutant for pretaporter (17). B, dispersed cells prepared from stage-16 embryos of the indicated fly lines were examined for the level of phagocytosis. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of the results from three independent experiments (n = 5 in each experiment). NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we isolated the Drosophila protein DmCaBP1 and showed its role in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. DmCaBP1 resides in the lumen of the ER of normal cells and is apparently relocated outside cells upon the induction of apoptosis. DmCaBP1 most likely connects apoptotic cells and phagocytes for the induction of phagocytosis. We previously reported another ER protein, which we named Pretaporter, as a ligand for Draper (17). Genetic experiments in this study showed that a simultaneous loss of DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter does not bring about a further decrease in the level of phagocytosis compared with flies lacking either one of these ER proteins, suggesting cooperation between the two proteins. Data obtained from a coimmunoprecipitation experiment and a solid-phase binding assay suggested no physical association between these two proteins (data not shown). Recently, Wang et al. (31) reported that a transthyretin-like protein of C. elegans called TTR-52 is secreted from non-apoptotic cells and acts as a bridging molecule between apoptotic cells and phagocytes by binding to phosphatidylserine and CED-1, respectively. As an analogy to this protein, DmCaBP1 could act as a bridging or tethering molecule to promote phagocytosis. We speculate that both Pretaporter and DmCaBP1 are essential for the Draper-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in that Pretaporter is responsible for the activation of Draper, whereas DmCaBP1 connects apoptotic cells and phagocytes.

Our data suggested that intact DmCaBP1, even with the ER retention motif, is released from apoptotic cells. The externalization of DmCaBP1 depended on the activity of caspases but did not seem to involve vesicle transport, autophagy, or proteasomes. By contrast, Pnaretakis et al. (32) reported that mammalian calreticulin is exposed to the surface of apoptotic cells by SNARE-dependent exocytosis, and an ER-residing aminopeptidase is secreted from macrophages upon an inflammatory stimulus in a manner involving vesicle transport (30). Besides DmCaBP1, two more ER proteins, Calreticulin (23) and Pretaporter (17), are found at the surface of apoptotic cells. Unlike DmCaBP1, these proteins seemed to directly move from the ER to the cell surface without being released from cells. Franz et al. (33) showed that several ER-residing proteins, which were not analyzed in this study, are exposed at the surface of apoptotic cells. Therefore, the externalization or surface exposure of ER proteins could be a general feature in apoptotic cells, although the mechanism of relocation may vary from protein to protein. Clarification of the mechanisms and meanings of this biological event is important for understanding the extra-ER role for ER proteins in apoptosis.

Two proteins, DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter (17), isolated through affinity chromatography with a matrix containing the extracellular portion of Draper, turned out to be ER proteins containing the thioredoxin-like domain. Two and three domains are repeated in tandem in DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter, respectively. We showed previously that two thioredoxin-like domains are sufficient for Pretaporter to bind Draper (17), and this coincides with the presence of two domains in DmCaBP1. This domain is often contained in protein disulfide isomerases that catalyze the formation and breakage of disulfide bonds (34, 35). Na et al. (36) showed that human protein disulfide isomerase undergoes partial cleavage by caspases in apoptotic cells. However, DmCaBP1 did not seem to undergo proteolysis during apoptosis-dependent externalization. To examine a possible effect of DmCaBP1 on the expression of Draper, we analyzed Draper with lysates of adult flies by Western blotting, but found no significant difference as to either the signal intensity or the electrophoretic mobility on a gel determined without 2-mercaptoethanol, irrespective of the existence of DmCaBP1 (data not shown). Flies lacking both DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter developed normally and showed no obvious defects, suggesting that these two ER proteins are dispensable. Roles for DmCaBP1 and Pretaporter as proteins containing the thioredoxin-like domain and localized in the ER, besides their involvement in the Draper-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, remain to be elucidated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marc Freeman and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for the fly stocks, Bok Luel Lee for the antibody, and the National Institute of Genetics for the expressed sequence tag clone. We also thank Koichi Ueda, Hisashi Wada, and Takeshi Moki for contributing to our study at the initial stage and Masafumi Tsujimoto for advice. We also acknowledge the use of the GenBanktm.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 19370051 and 22370049 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to Y. N.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liao D. J. (2005) The scavenger cell hypothesis of apoptosis. Apoptosis redefined as a process by which a cell in living tissue is destroyed by phagocytosis. Med. Hypotheses 65, 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakanishi Y., Nagaosa K., Shiratsuchi A. (2011) Phagocytic removal of cells that have become unwanted. Implications for animal development and tissue homeostasis. Dev. Growth Differ. 53, 149–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Savill J., Fadok V. (2000) Corpse clearance defines the meaning of cell death. Nature 407, 784–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lauber K., Blumenthal S. G., Waibel M., Wesselborg S. (2004) Clearance of apoptotic cells. Getting rid of the corpses. Mol. Cell 14, 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ravichandran K. S., Lorenz U. (2007) Engulfment of apoptotic cells. Signals for a good meal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 964–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ravichandran K. S. (2011) Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal. The find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity 35, 445–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reddien P. W., Horvitz H. R. (2004) The engulfment process of programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 193–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kinchen J. M., Hengartner M. O. (2005) Tales of cannibalism, suicide, and murder. Programmed cell death in C. elegans. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 65, 1–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mangahas P. M., Zhou Z. (2005) Clearance of apoptotic cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 295–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lettre G., Hengartner M. O. (2006) Developmental apoptosis in C. elegans. A complex CEDnario. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou Z., Hartwieg E., Horvitz H. R. (2001) CED-1 is a transmembrane receptor that mediates cell corpse engulfment in C. elegans. Cell 104, 43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Callebaut I., Mignotte V., Souchet M., Mornon J. P. (2003) EMI domains are widespread and reveal the probable orthologs of the Caenorhabditis elegans CED-1 protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300, 619–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freeman M. R., Delrow J., Kim J., Johnson E., Doe C. Q. (2003) Unwrapping glial biology. Gcm target genes regulating glial development, diversification, and function. Neuron 38, 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manaka J., Kuraishi T., Shiratsuchi A., Nakai Y., Higashida H., Henson P., Nakanishi Y. (2004) Draper-mediated and phosphatidylserine-independent phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by Drosophila hemocytes/macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48466–48476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu H. H., Bellmunt E., Scheib J. L., Venegas V., Burkert C., Reichardt L. F., Zhou Z., Fariñas I., Carter B. D. (2009) Glial precursors clear sensory neuron corpses during development via Jedi-1, an engulfment receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1534–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamon Y., Trompier D., Ma Z., Venegas V., Pophillat M., Mignotte V., Zhou Z., Chimini G. (2006) Cooperation between engulfment receptors. The case of ABCA1 and MEGF10. PLoS ONE 1, e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuraishi T., Nakagawa Y., Nagaosa K., Hashimoto Y., Ishimoto T., Moki T., Fujita Y., Nakayama H., Dohmae N., Shiratsuchi A., Yamamoto N., Ueda K., Yamaguchi M., Awasaki T., Nakanishi Y. (2009) Pretaporter, a Drosophila protein serving as a ligand for Draper in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. EMBO J. 28, 3868–3878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LaJeunesse D. R., Buckner S. M., Lake J., Na C., Pirt A., Fromson K. (2004) Three new Drosophila markers of intracellular membranes. BioTechniques 36, 784–788, 790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cornwell W. D., Kirkpatrick R. B. (2001) Cactus-independent nuclear translocation of Drosophila RELISH. J. Cell. Biochem. 82, 22–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Théry C., Boussac M., Véron P., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Raposo G., Garin J., Amigorena S. (2001) Proteomic analysis of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. A secreted subcellular compartment distinct from apoptotic vesicles. J. Immunol. 166, 7309–7318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nagaosa K., Okada R., Nonaka S., Takeuchi K., Fujita Y., Miyasaka T., Manaka J., Ando I., Nakanishi Y. (2011) Integrin βν-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in Drosophila embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25770–25777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi J. Y., Whitten M. M., Cho M. Y., Lee K. Y., Kim M. S., Ratcliffe N. A., Lee B. L. (2002) Calreticulin enriched as an early-stage encapsulation protein in wax moth Galleria mellonella larvae. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 26, 335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuraishi T., Manaka J., Kono M., Ishii H., Yamamoto N., Koizumi K., Shiratsuchi A., Lee B. L., Higashida H., Nakanishi Y. (2007) Identification of calreticulin as a marker for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in Drosophila. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 500–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu H., Boulianne G. L., Trimble W. S. (2002) Drosophila syntaxin 16 is a Q-SNARE implicated in Golgi dynamics. J. Cell Sci. 115, 4447–4455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hou Y. C., Chittaranjan S., Barbosa S. G., McCall K., Gorski S. M. (2008) Effector caspase Dcp-1 and IAP protein Bruce regulate starvation-induced autophagy during Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 182, 1127–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lundgren J., Masson P., Mirzaei Z., Young P. (2005) Identification and characterization of a Drosophila proteasome regulatory network. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4662–4675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rumpf S., Lee S. B., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (2011) Neuronal remodeling and apoptosis require VCP-dependent degradation of the apoptosis inhibitor DIAP1. Development 138, 1153–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Awasaki T., Tatsumi R., Takahashi K., Arai K., Nakanishi Y., Ueda R., Ito K. (2006) Essential role of the apoptotic cell engulfment genes draper and ced-6 in programmed axon pruning during Drosophila metamorphosis. Neuron 50, 855–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Y., Musacchio M., Finkelstein R. (1998) A homologue of the calcium-binding disulfide isomerase CaBP1 is expressed in the developing CNS of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Genet. 23, 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goto Y., Ogawa K., Hattori A., Tsujimoto M. (2011) Secretion of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 is involved in the activation of macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21906–21914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang X., Li W., Zhao D., Liu B., Shi Y., Chen B., Yang H., Guo P., Geng X., Shang Z., Peden E., Kage-Nakadai E., Mitani S., Xue D. (2010) Caenorhabditis elegans transthyretin-like protein TTR-52 mediates recognition of apoptotic cells by the CED-1 phagocyte receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 655–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panaretakis T., Kepp O., Brockmeier U., Tesniere A., Bjorklund A. C., Chapman D. C., Durchschlag M., Joza N., Pierron G., van Endert P., Yuan J., Zitvogel L., Madeo F., Williams D. B., Kroemer G. (2009) Mechanisms of preapoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO J. 28, 578–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Franz S., Herrmann K., Fürnrohr B. G., Führnrohr B., Sheriff A., Frey B., Gaipl U. S., Voll R. E., Kalden J. R., Jäck H. M., Herrmann M. (2007) After shrinkage apoptotic cells expose internal membrane-derived epitopes on their plasma membranes. Cell Death Differ. 14, 733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turano C., Coppari S., Altieri F., Ferraro A. (2002) Proteins of the PDI family. Unpredicted non-ER locations and functions. J. Cell. Physiol. 193, 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ellgaard L., Ruddock L. W. (2005) The human protein disulphide isomerase family. Substrate interactions and functional properties. EMBO Rep. 6, 28–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Na K. S., Park B. C., Jang M., Cho S., Lee D. H., Kang S., Lee C. K., Bae K. H., Park S. G. (2007) Protein disulfide isomerase is cleaved by caspase-3 and -7 during apoptosis. Mol. Cells 24, 261–267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.