Background: The nuclear molecules responsible for FcγR-mediated inflammation remain unknown.

Results: C/EBPβ and -δ are activated by IgG IC, which plays a critical role in TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production in macrophages.

Conclusion: C/EBPβ and -δ play a key role in FcγR-mediated induction of inflammatory mediators.

Significance: The finding encourages further investigation of the role of C/EBPβ and -δ in IC diseases.

Keywords: Chemokines, Complement, Cytokine, Inflammation, Transcription factors

Abstract

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) and C/EBPδ are known to participate in the regulation of many genes associated with inflammation. However, little is known about the activation and function of C/EBPβ and -δ in inflammatory responses elicited by Fcγ receptor (FcγR) activation. Here we show that C/EBPβ and -δ activation are induced in IgG immune complex (IC)-treated macrophages. The increased expression of C/EBPβ and -δ occurred at both mRNA and protein levels. Furthermore, induction of C/EBPβ and -δ was mediated, to a large extent, by activating FcγRs. Using siRNA-mediated knockdown as well as macrophages deficient for C/EBPβ and/or -δ, we demonstrate that C/EBPβ and -δ play a critical role in the production of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages. Moreover, both ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK are involved in C/EBP induction and TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production induced by IgG IC. We provide the evidence that C5a regulates IgG IC-induced inflammatory responses by enhancing ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK activities as well as C/EBPβ and -δ activities. Collectively, these data suggest that C/EBPβ and -δ are key regulators for FcγR-mediated induction of cytokines and chemokines in macrophages. Furthermore, C/EBPs may play an important regulatory role in IC-associated inflammatory responses.

Introduction

The Fcγ receptors (FcγRs)2 are a family of cell surface molecules that bind the Fc portion of IgG immunoglobulins. Different cell types bear different sets of FcγRs, and their specificities for various antibody classes thus determine which types of cells will be engaged in given responses. Four types of FcγRs are identified in mice: FcγRI, FcγRIIB, FcγRIII, and the newest member, FcγRIV. FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV are activating receptors, all of which associate with FcR common γ-chain, whereas FcγRIIB is an inhibitory member. The corresponding human FcγRs are FcγRIA, FcγRIIA, FcγRIIIA (activating), and FcγIIB (inhibitory) receptors. Human FcγRIA and mouse FcγRI have high affinity for IgG. Based on the sequence similarity, human FcγRIIA is most closely related to mouse FcγRIII, and human FcγRIIIA seems to be the orthologue of mouse FcγRIV (1). However, human FcγRIIA has an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif in its cytosolic domain, which is not present in mouse FcγRIII and does not require γ-chain for functionality (1). Macrophages, the sentinels of innate immunity, play key roles in inflammation. Activation of macrophages by FcγRs triggers a wide variety of cellular responses (1, 2). In addition to phagocytosis, one of the major cellular responses in macrophages initiated by IgG immune complex (IC)-mediated FcγR cross-linking is the activation of genes encoding chemokines and cytokines important in inflammation. Although the production of these mediators is mainly controlled at the transcriptional level in response to various inflammatory stimuli, the key nuclear molecules that mediate FcγR signaling in macrophages remain unknown. Several transcription factors, such as NF-κB, AP-1, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ), and Stat3, are activated in macrophages/monocytes following IgG IC stimulation (3, 4). Studies using pharmacological inhibitors suggested that NF-κB activation was involved in the expression of several chemokines, including macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and β (MIP-1α and MIP-1β), upon cross-linking of FcγR (3, 5). However, these lines of evidence are either indirect or correlative. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanisms whereby the expression of inflammatory mediators is induced by FcγRs.

C/EBPα, -β, -δ, -ϵ, -γ, and -ζ comprise a family of basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors that dimerize through a leucine zipper motif and bind to DNA through an adjacent basic region. C/EBPβ and -δ have been implicated in the regulation of inflammatory mediators as well as other gene products associated with the activation of macrophages and the acute phase inflammatory response (6). Two major forms of C/EBPβ are translated from the same messenger RNA, liver-enriched activating protein (LAP) and liver-enriched inhibitory protein (LIP) (7). The roles of C/EBP family members in regulating inflammation have also been studied using knock-out mice. Interestingly, the LPS stimulation of peritoneal macrophages from C/EBPβ-deficient mice led to normal induction of several inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, with the exception of G-CSF, Mincle, and mPGES-1 (8–11), although macrophages from these mice demonstrate defective intracellular bacteria killing. Similarly, C/EBPδ-deficient macrophages show nominal defects in IL-6 and TNF-α production in response to several TLR ligands (12). In contrast, the absence of both C/EBPβ and -δ results in a significant decrease in the TLR ligand-induced production of both IL-6 and TNF-α (12). In another study, Gorgoni et al. (13) found that LPS-induced expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and inducible nitric-oxide synthase is partially impaired in C/EBPβ-deficient macrophages and that expression of IL-12 p35 is completely defective. However, IL-12 p40, RANTES, and MIP1-β are more efficiently induced in response to IFN-γ and LPS in the absence of C/EBPβ. These results raise the possibility that the redundant expression of multiple C/EBP isoforms as well as differences in C/EBP homo-/heterodimer occupancy in specific gene promoters may account for the differential effects of C/EBPβ and -δ deficiency. Thus, the role of C/EBPβ and -δ in regulating transcription of the different inflammation-regulated mediators warrants further investigation. Furthermore, whether and how C/EBPβ and -δ are involved in the FcγR-induced inflammatory response remains unclear, and the signals that mediate the activation of C/EBPβ and -δ are unknown. In this report, we demonstrate that both C/EBPβ and -δ are induced by IgG IC in macrophages. Furthermore, activation of C/EBPβ and -δ in macrophages is mediated, to a large extent, by FcγRs. We provide evidence that C/EBPβ and -δ are key transcription factors that regulate the FcγR-mediated induction of inflammatory cytokine and chemokines in macrophages. Moreover, both ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK are involved in the C/EBP activation and mediator production induced by IgG IC. Interestingly, we show that C5a regulates IgG IC-induced inflammatory responses by enhancing ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK activities as well as C/EBP activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Reagents

RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; TIB-71TM) (Manassas, VA). ΨCREJ2 cells (a producer cell line for the J2 retrovirus (14) kindly provided by H. Young) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Rockford, IL), 200 mm l-glutamine, and 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Transformed C/EBP-deficient macrophage cell lines were generated from bone marrow of mice lacking C/EBPβ and/or C/EBPδ as well as their wild-type littermates (15, 16). Bone marrow was collected from the femurs and tibias and placed into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% FBS. The bone marrow plugs were disaggregated and pelleted, and red blood cells were lysed using NH4Cl lysis solution (Sigma). The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 200 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin. After 24 h, macrophages suspended in the medium were collected by centrifugation. To generate immortalized macrophage cell lines, 1–5 × 107 BM cells were resuspended in ΨCREJ2 cell supernatant supplemented with 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) and 100 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor. ΨCREJ2 cell supernatant was removed after 24 h, and cell lines were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 200 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Rabbit anti-BSA IgG was purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Solon, OH). ELISA kits for mouse TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII and ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, were purchased from EMD Biosciences (Gibbstown, NJ). C5a and BSA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Luciferase Assay

Transient transfections were performed with 1.5 × 105 cells plated in 12-well plates by using 0.5 μg of DNA and 1.5 μl of Fugene®6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) in 50 μl of Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen). 24 h after transfection, the cells were incubated either with or without 100 μg/ml IgG IC for 5 h. Cell lysates were subjected to luciferase activity analysis by using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). IgG IC were formed by the addition to anti-BSA of BSA at the point of antigen equivalence as described previously (17).

siRNA Transfection

Transient siRNA transfections were performed by transfecting 2 × 106 RAW264.7 cells with control siRNA or C/EBPβ/δ siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) using the Amaxa® nucleofector kit V. 12 h later, the cells were treated with or without 100 μg/ml IgG IC for 5 h. Supernatants were collected for ELISA analysis.

Peritoneal Macrophage Isolation and Culture

8–9-Week-old specific pathogen-free male C57BL/6 were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. FcRγ- and FcγRII-deficient mice were obtained from Taconic. C5aR knock-out mice were kindly provided by Craig Gerard (Harvard Medical School). C/EBPβ−/− and C/EBPδ−/− mice have been described previously (15, 16). Mouse peritoneal macrophages were isolated by using the thioglycollate method. Briefly, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.5 ml of 2.4% sterile thioglycollate dissolved in double distilled H2O. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained by instillation and aspiration of 10 ml of PBS 4 days after thioglycollate administration. The macrophages were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and allowed to adhere for 2 h, followed by 100 μg/ml IgG IC treatment for the indicated time periods. The supernatants were harvested and subjected to ELISA analysis. The purity of the cell suspension was ∼99%, which was determined by staining of the peritoneal cell suspension with the HEMA 3® Stain Set (Fisher).

ELISA

Macrophages were stimulated by IgG IC for the indicated time. The supernatants were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the cell-free supernatants were harvested for TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α measurements according to the manufacturer's protocols.

RNA Isolation and Detection of mRNA by Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cells with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's procedure. After isolation, total cellular RNA was incubated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI) to remove contaminating DNA. 2 μg of total RNA was submitted to reverse transcription by using Superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCR was performed with the following primers: for C/EBPβ, 5′ primer (5′-CAA GCT GAG CGA CGA GTA CA-3′) and 3′ primer (5′- AGC TGC TCC ACC TTC TTC TG-3′); for C/EBPδ, 5′ primer (5′-CGC AGA CAG TGG TGA GCT T-3′) and 3′ primer (5′-CTT CTG CTG CAT CTC CTG GT-3′); for GAPDH, 5′ primer (5′-GCC TCG TCT CAT AGA CAA GAT G-3′) and 3′ primer (5′-CAG TAG ACT CCA CGA CAT AC-3′). After a “hot start” for 5 min at 94 °C, 28–33 cycles were used for amplification with a melting temperature of 94 °C, an annealing temperature of 60 °C, and an extending temperature of 72 °C, each for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. PCR was performed using different cycle numbers for all primers, to ensure that DNA was detected within the linear part of the amplifying curves for both primers.

Western Blot Analysis

RAW264.7 cells were lysed in cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. Samples containing 80 μg of protein were electrophoresed in a 12% polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-C/EBPβ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-C/EBPδ antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-phospho-p38 MAPK antibody (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-p38 MAPK antibody (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-p44/42 antibody (Cell Signaling), and rabbit anti-GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling), respectively. After three washes in TBST, the membranes were incubated with a 1:5000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare). The membrane was developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence technique according to the manufacturer's protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts of RAW264.7 cells or primary macrophages were prepared as follows. Cells were lysed in 15 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.6), 2 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) for 10 min on ice. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 20 s at 4 °C. Proteins were extracted from nuclei by incubation at 4 °C with vigorous vortexing in buffer C (420 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 0.2 mm EDTA, 25% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and complete protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Protein concentrations were determined by a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The EMSA probe was C/EBP consensus oligonucleotide (5′-TGCAGATTGCGCAATCTGCA-3′; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or a NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′; Promega, Madison, WI). C/EBP and NF-κB probes were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol at 10 mCi/ml; GE Healthcare). DNA binding reactions were performed at room temperature in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 6 μl of nuclear extract (1 mg/ml in buffer C) and 5 μl of 5× binding buffer (20% (w/v) Ficoll, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 5 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol). The remainder of the reaction mixture contained KCl at a final concentration of 50 mm, Nonidet P-40 at a final concentration of 0.1%, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 200 pg of probe, bromphenol blue at a final concentration of 0.06% (w/v), and water to final volume of 25 μl. Samples were electrophoresed through 5.5% polyacrylamide gels in 1× TBE at 190 V for ∼3.5 h, dried under vacuum, and exposed to x-ray film. For supershifts, nuclear extracts were preincubated with antibodies (1–2 μg) for 0.5 h at 4 °C prior to the binding reaction. The following antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.: NF-κB p50, p52, p65, RelB, c-Rel, C/EBPα, C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, C/EBPϵ, C/EBPγ, and normal rabbit immunoglobulin G.

Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as the mean ± S.E. Significance was assigned where p < 0.05. Data sets were analyzed using Student's t test or one-way analysis of variance, with individual group means being compared with the Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test.

RESULTS

IgG IC Induces Expression of C/EBPβ and -δ in Macrophages

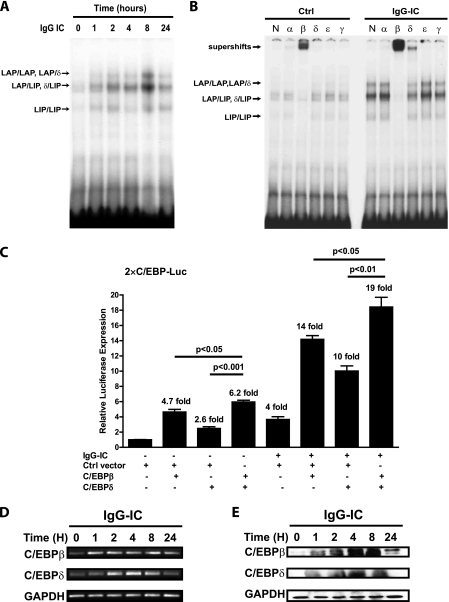

To determine if C/EBP activities are induced by IgG IC, we first examined the DNA binding activity of C/EBPs in RAW264.7 macrophages. As shown in Fig. 1A, RAW264.7 cells were challenged with IgG IC for different time periods, and extracted nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA. The results show that strong C/EBP DNA binding activity was induced after IgG IC stimulation (Fig. 1A). To determine which C/EBP family members are induced by IgG IC, supershift assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 1B, there was a low but detectable level of C/EBPβ binding activity in nuclear extract from control-treated RAW264.7 cells. The basal level of C/EBPδ binding was minimal; however, DNA binding activities of both C/EBPβ and -δ were dramatically enhanced by IgG IC stimulation.

FIGURE 1.

IgG immune complexes induce C/EBPβ and -δ expression and increase C/EBP DNA binding activity in macrophages. A, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 100 μg/ml immune complexes for the times indicated. Nuclear proteins were harvested and subjected to EMSA to measure C/EBP DNA binding activity. B, RAW264.7 cells were treated or left untreated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes for 4 h. The nuclear extracts were harvested for gel supershift assay to identify which C/EBP family member DNA binding activity was regulated by IgG immune complex treatment. N, α, β, δ, ϵ, and γ, normal rabbit IgG, anti-C/EBPα antibody, anti-C/EBPβ antibody, anti-C/EBPδ antibody, anti-C/EBPϵ antibody, and anti-C/EBPγ antibody, respectively. The arrows indicate C/EBP complex and supershift species. C, RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with a total of 0.5 μg of the indicated DNA. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complex for 5 h. Cell lysates were used to perform a luciferase activity assay. Luminometer values were normalized for expression from a co-transfected thymidine kinase reporter gene. The data were expressed as means of three experiments ± S.E. (error bars). RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes for different time periods. Then total cellular RNA was isolated for RT-PCR with primers for C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and GAPDH, respectively (D). The level of GAPDH is shown at the bottom as a loading control. E, the total proteins were extracted to conduct Western blot using rabbit anti-C/EBPβ antibody, rabbit anti-C/EBPδ antibody, and rabbit anti-GAPDH antibody, respectively. The level of GAPDH is shown at the bottom as a loading control.

We further examined the IgG IC-induced C/EBP activation in transient transfections using 2XC/EBP-Luc, a promoter-reporter that contains two copies of a canonical C/EBP binding site, and expression vectors for C/EBβ and/or C/EBPδ. These transfections were carried out with and without IgG IC treatment. Consistent with the results from EMSA, IgG IC stimulation alone (without transfection of a C/EBP expression vector) increased luciferase activity 4-fold compared with the control group (Fig. 1C). IgG IC treatment of C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPβ plus C/EBPδ transfectants induced luciferase expression 14-, 10-, and 19-fold, respectively, over the control value. Interestingly, overexpression of C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPβ plus C/EBPδ alone (i.e. in the absence of IC treatment) stimulated luciferase activity 4-, 2.6-, and 6.2-fold, respectively; this is significantly less than the values observed in the presence of IgG IC. These data suggest that IgG IC signaling may stimulate C/EBP transcriptional activity in addition to inducing expression of the endogenous proteins. Moreover, C/EBPβ and -δ together were more potent activators than either protein alone, indicating that C/EBPβ and -δ are preferential dimerization partners, C/EBPβ/δ heterodimers have stronger DNA binding activity than homodimers, or both.

We next examined whether IgG IC induces expression of C/EBPβ and -δ at the mRNA level. RT-PCR showed that C/EBPβ and -δ mRNAs were highly induced in RAW264.7 cells following a 24-h treatment with IgG IC (Fig. 1D). We then sought to determine whether this induction resulted in increased abundance of C/EBPβ and -δ proteins in RAW264.7 cells. The Western blot analysis of proteins isolated over a time course of IgG IC treatment revealed a time-dependent increase in the abundance of both C/EBPβ (mainly LAP) and C/EBPδ proteins (Fig. 1E). These data demonstrate that increased abundance of C/EBPβ and -δ is coincident with their increased DNA binding activity in RAW264.7 cells.

C/EBPβ and -δ Are Critical Regulators of Cytokine and Chemokine Expression in IgG IC-stimulated Macrophages

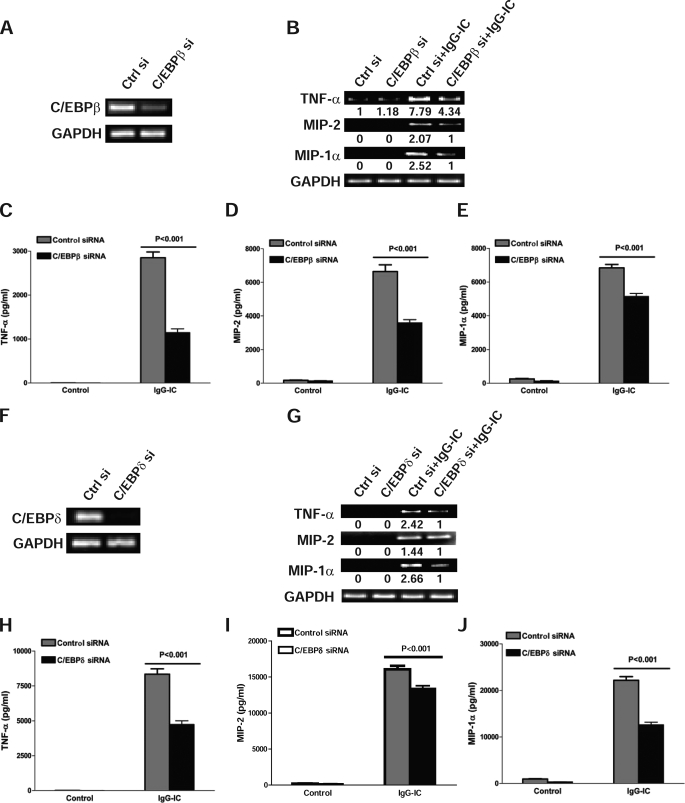

C/EBPβ and -δ play important roles in regulating inflammatory responses in many different cells, including macrophages (12, 13, 18–21). However, whether they are involved in macrophage inflammatory responses after FcγR cross-linking is unknown. TNF-α is an early proinflammatory cytokine secreted by macrophages during inflammation. Both MIP-2 and MIP-1α were initially identified as monokines secreted from LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (22–25). MIP-2 belongs to the C-X-C chemokine subfamily and has been shown to possess potent chemotactic activity for neutrophils, whereas MIP-1α, as a member of the C-C chemokine subfamily, has been shown to chemoattract leukocytes of the monocyte lineage (22, 23, 26, 27). Therefore, we sought to determine the effect of C/EBPβ and -δ deficiency on the expression of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α from IgG-IC-stimulated macrophages. To that end, we first showed that both C/EBPβ and -δ expression were efficiently depleted by their respective siRNAs in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2, A and F). IgG IC significantly increased expression of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α mRNAs in control cells, whereas all were markedly reduced when C/EBPβ or -δ was ablated (Fig. 2, B and G). To examine if knockdown of C/EBPβ or -δ led to a corresponding reduction in secretion of these inflammatory proteins, we performed ELISA analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, C–E, the secretions of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α from RAW264.7 cells were all significantly induced by IgG IC treatment. However, when compared with control siRNA treatment, C/EBPβ siRNA suppressed TNF-α production by ∼60%, MIP-2 by ∼46%, and MIP-1α by ∼25%. Furthermore, C/EBPδ knockdown significantly inhibited secretion of TNF-α (∼43%), MIP-2 (∼17%), and MIP-1α (∼43%) (Fig. 2, H–J).

FIGURE 2.

C/EBPβ and -δ silencing down-regulates IgG immune complex-induced TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production from macrophages. A and F, RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA, C/EBPβ siRNA (A), or C/EBPδ siRNA (F), respectively. 12 h later, RNAs were extracted and subjected to RT-PCR to examine the expression of C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and GAPDH, respectively. The level of GAPDH is shown at the bottom as a loading control. B and G, RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA, C/EBPβ siRNA (B), or C/EBPδ siRNA (G). 12 h later, cells were incubated with or without 100 μg/ml IgG IC for 4 h. Total RNA was extracted, and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed to examine expression of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α, respectively. C–E and H–J, RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with control siRNA, C/EBPβ siRNA (C–E), or C/EBPδ (H–J), respectively. 12 h after transfection, the cells were stimulated with or without 100 μg/ml IgG immune complex for 5 h. The supernatants were harvested, and ELISA was performed to determine the production of TNF-α (C–E and H–J). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 7–12).

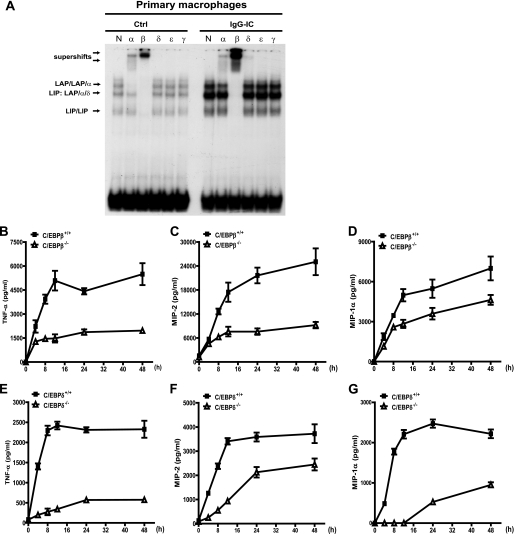

We further determined whether the observed regulatory role of C/EBPβ and -δ on the IgG IC-induced TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production in RAW264.7 cells was also applicable to primary macrophages. We first showed that the DNA binding activities of both C/EBPβ and -δ (to a minor extent) were induced by IgG IC in peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 3A). We next demonstrated that, upon IgG IC treatment, C/EBPβ- or C/EBPδ-deficient macrophages released significantly lesser amounts of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α at all time points when compared with wild type macrophages (Fig. 3, B–D and E–G, respectively), consistent with the results obtained from RAW264.7 cells. In addition, we compared the IgG IC responses of four different immortalized macrophage cell lines established from WT, C/EBPβ−/−, C/EBPδ−/−, and C/EBPβ−/−/δ−/− cells. When compared with WT macrophages, C/EBPβ knock-out suppressed TNF-α induction by ∼80%, MIP-1α by ∼58%, and MIP-2 by ∼77.7%, and C/EBPδ knock-out also significantly inhibited TNF-α (∼24%), MIP-1α (∼49%), and MIP-2 (∼34%) (supplemental Fig. 1). Moreover, C/EBPβ/δ double knock-out further reduced secretion of TNF-α (∼98%), MIP-1α (∼99%), and MIP-2 (∼98%) (supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, there is a redundant role for C/EBPβ and -δ in IgG IC-induced TNF-α, MIP-1α, and MIP-2 production in macrophages. Taken together, these findings show that C/EBPβ and -δ are critical regulators of cytokine and chemokine production in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages.

FIGURE 3.

C/EBPβ and -δ are critical regulators of cytokine and chemokine production in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages. A, primary peritoneal macrophages obtained from wild type were treated or left untreated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes for 4 h. The nuclear extracts were harvested for a gel supershift assay to identify which C/EBP family member DNA binding activity was regulated by IgG immune complex treatment. N, α, β, δ, ϵ, and γ, normal rabbit IgG, anti-C/EBPα antibody, anti-C/EBPβ antibody, anti-C/EBPδ antibody, anti-C/EBPϵ antibody, and anti-C/EBPγ antibody, respectively. The arrows indicate C/EBP binding bands and supershift bands. B–D and E–G, primary peritoneal macrophages obtained from corresponding wild type, C/EBPβ knock-out (B–D), and C/EBPδ knock-out (E–G) mice were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complex for different time periods, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA analysis for TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 6).

NF-κB plays a central role in coordinating immune and inflammatory responses. To test its involvement in IgG IC-induced inflammation, RAW264.7 cells were treated with a NF-κB inhibitor, BAY 11-7082 (supplemental Fig. 2). The data showed that upon IgG IC stimulation, the levels of all three mediators were down-regulated by BAY 11-7082, with a significant inhibitory effect on TNF-α and MIP-1α production, suggesting that NF-κB also plays an important regulatory role in IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production.

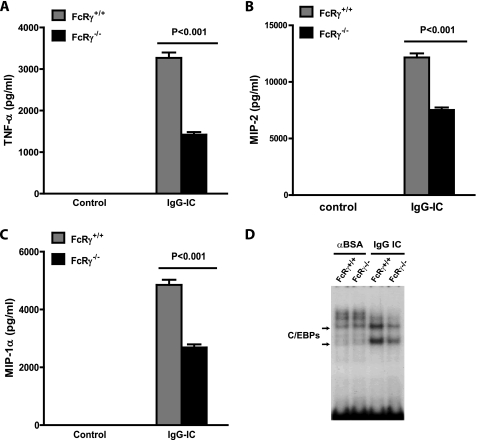

FcγRs Trigger C/EBP-mediated Cytokine and Chemokine Production in IC-stimulated Macrophages

FcγRs exert both activating and inhibitory effects on inflammatory responses, and the cellular threshold for inflammation is dependent on the ratio of the opposing signaling FcγRs. Because both activating and inhibitory FcγRs are expressed on macrophages (1, 28), we sought to determine the role of FcγRs in IgG IC-induced inflammation in macrophages. Using peritoneal macrophages from FcR γ-chain knock-out mice, we first examined the influence of conventional activating FcγRs on IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production. As shown in Fig. 4, A–C, FcR γ-chain mutation resulted in a significantly decreased production of TNF-α (∼57%), MIP-2 (∼38%), and MIP-1α (∼45%) in IgG IC-treated macrophages compared with their wild type counterparts. In contrast, FcγRII deficiency resulted in an approximately 2-fold increase of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production (supplemental Fig. 3). Because our data suggest that C/EBPβ and -δ may play important roles in cytokine and chemokine expression in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages (Figs. 2 and 3), we next examined the effect of FcγRs deficiency on C/EBPβ and -δ activation. We found that knock-out of activating FcγRs suppressed induction of C/EBP DNA binding activity (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, inhibitory FcγRII deficiency elevated C/EBP DNA binding activity (mainly LAP/LIP and LAP/γ heterodimers) (data not shown). In summary, these findings suggest that activating FcγRs play an important role in IgG IC-induced C/EBPβ and -δ induction, leading to production of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α, whereas the inhibitory FcγRII has an opposite effect.

FIGURE 4.

FcγRs play important roles in C/EBP-mediated cytokine and chemokine production in macrophages. A–C, primary peritoneal macrophages obtained from corresponding wild type and FcR γ-chain-deficient mice were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG IC for 5 h, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA analysis for TNF-α (A), MIP-2 (B), and MIP-1α (C) production. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 8). D, primary peritoneal macrophages obtained from corresponding wild type and FcR γ-chain-deficient mice were treated or left untreated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes for 4 h. The nuclear proteins were harvested and subjected to EMSA to measure C/EBP DNA binding activity.

ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK Are Involved in IgG IC-induced C/EBPβ and -δ Activation and Subsequent Cytokine/Chemokine Production

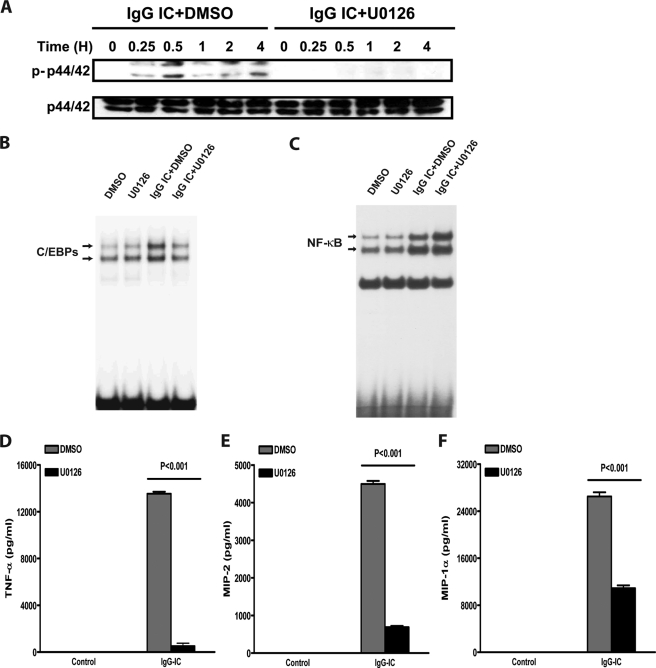

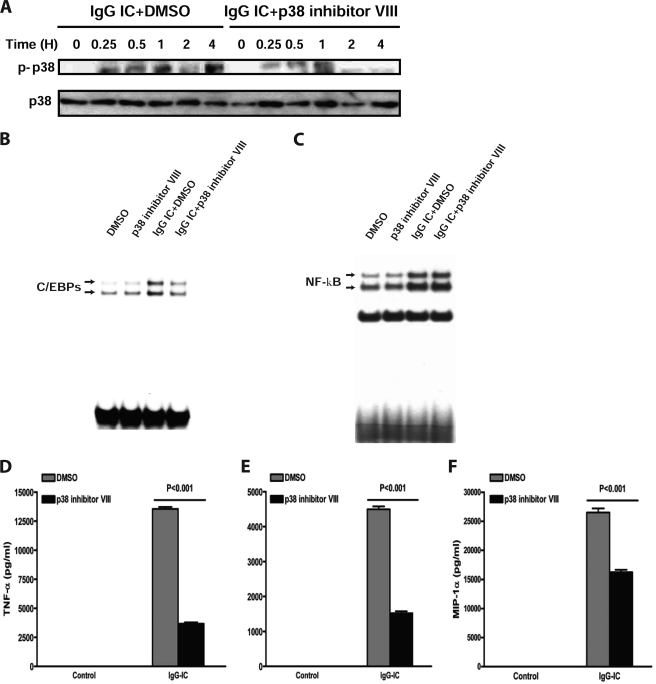

Previous studies have shown that FcγR cross-linking on macrophages/monocytes activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2, p44/42) and p38 MAPK signaling pathways (29, 30). However, whether ERK and p38 signaling pathways function as transducers connecting FcγR stimulation to C/EBPβ and -δ activation remains unclear. To investigate this possibility, we first evaluated the MAPK pathways in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages. As shown in Fig. 5A and 6A, IgG IC treatment led to the phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK in a time-dependent manner. We next evaluated the influence of these phosphorylated MAPK on C/EBPβ and -δ activation by using specific pharmacological inhibitors for ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK. We observed that phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK was significantly inhibited by U0126 and p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII, respectively (Figs. 5A and 6A). Further, U0126 and p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII markedly suppressed C/EBP DNA binding activity induced by IgG IC (Figs. 5B and 6B).

FIGURE 5.

ERK1/2 is involved in IgG IC-induced C/EBPβ and -δ activation and subsequent cytokine/chemokine production in macrophages. A, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126 (10 μm), for the indicated time periods. Total proteins were subjected to Western blot by using rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 (p-p44/42) antibody and rabbit anti-p44/42 antibody, respectively. B and C, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126 (10 μm), for 4 h. The nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA for C/EBP DNA binding (B) and NF-κB DNA binding (C). D–F, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126 (10 μm), for 5 h, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA analysis for TNF-α (D), MIP-2 (E), and MIP-1α (F) production. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 10).

FIGURE 6.

p38 MAPK is involved in IgG IC-induced C/EBPβ and -δ activation and subsequent cytokine/chemokine production in macrophages. A, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of p38 MAPK inhibitor VII (10 μm) for the indicated time periods. Total proteins were subjected to Western blot by using rabbit anti-phospho-p38 (p-p38) antibody and rabbit anti-p38 antibody, respectively. B and C, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of p38 MAPK inhibitor VII (10 μm) for 4 h. The nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA for C/EBP DNA binding (B) and NF-κB DNA binding (C). D–F, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes in the presence or absence of p38 MAPK inhibitor VII (10 μm) for 5 h, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA analysis for TNF-α (D), MIP-2 (E), and MIP-1α (F) production. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 10).

The effect of MAPK inhibitors on IgG IC-induced NF-κB activation was also examined. EMSA showed that none of these inhibitors reduced NF-κB DNA binding activity (Figs. 5C and 6C). Interestingly, U0126 slightly elevated IgG IC-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 5C). To determine whether MAPK activation is involved in IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production (which are regulated by C/EBPβ and -δ), we evaluated the effect of U0126 and p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII on TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α secretion from RAW264.7 macrophages. As shown in Figs. 5D and 6D, U0126 and p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII significantly inhibited IgG IC-stimulated TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production. To determine whether ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK act in concert or sequentially downstream of FcγRs, RAW264.7 cells were treated with both ERK1/2 inhibitor and p38 inhibitor. As shown in supplemental Fig. 4, when compared with p38 MAPK inhibitor VIII or U0126 treatment alone, co-treatment resulted in a significantly decreased production of TNF-α (∼100%), MIP-2 (∼100%), and MIP-1α (∼66%). These data suggest that ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK act in concert to mediate IgG IC-induced inflammatory responses.

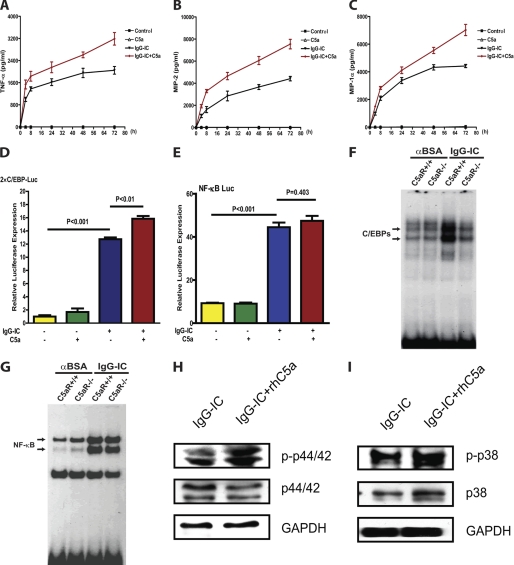

C5a Enhances IgG IC-stimulated Cytokine and Chemokine Production by Elevating C/EBPs but Not NF-κB DNA Binding Activity

C5a has been shown to synergistically enhance IC-induced TNF-α and MIP-2 production in alveolar macrophages (31, 32). Thus, we examined the role of C5a in the activation of peritoneal macrophages treated with IgG IC. As shown in Fig. 7, A–C, the addition of C5a significantly increased IgG IC-induced TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production, whereas stimulation with C5a alone had no effect on these inflammatory mediators. C5a plays a critical role in regulating the FcγR III/II pair to connect complement and FcγR pathways during IC-associated inflammation (31). Furthermore, C5a can be generated by IC-stimulated macrophages (33). Therefore, we determined if C5a signaling plays a role in activation of C/EBPs and NF-κB, which may lead to the increased production of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α. Reporter assays demonstrated that IgG IC-induced C/EBP activity, but not NF-κB activity, was further increased by the addition of C5a (Fig. 7, D and E). Moreover, IgG IC-stimulated C/EBP DNA binding was significantly reduced in peritoneal macrophages from C5aR-deficient mice compared with WT controls (Fig. 7F). In contrast, C5aR deficiency had no effect on NF-κB DNA-binding activity (Fig. 7G), consistent with the reporter data. Thus, C5a appears to have a specific role in activating C/EBPs.

FIGURE 7.

C5a signaling enhances IgG immune complex-induced C/EBP activation and cytokine and chemokine production in macrophages. A–C, mouse peritoneal macrophages were treated with 10 nm recombinant human C5a, 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes, or a combination of both stimuli for different time points, and supernatants were subjected to ELISA analysis for TNF-α (A), MIP-2 (B), and MIP-1α (C) production. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = 7). D and E, RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with a total of 0.5 μg of DNA. 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 10 nm recombinant human C5a, 100 μg/ml IgG immune complexes, or a combination of both stimuli for 4 h. Cell lysates were used to perform the luciferase activity assay. Luminometer values were normalized for expression from a co-transfected thymidine kinase reporter gene. The data were expressed as means of three experiments ± S.E. (error bars). F and G, peritoneal macrophages obtained from wild type and C5aR-deficient mice were treated with or without 100 μg/ml IgG IC for 4 h, and nuclear proteins were subjected to EMSA for C/EBP (F) or NF-κB (G) DNA binding activity. H and I, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 μg/ml IgG immune complex or IgG immune complex plus 10 nm rhC5a for 4 h. Total proteins were extracted and subjected to Western blot by using rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 (p-p44/42) antibody, rabbit anti-p44/42 antibody, and rabbit anti-GAPDH (H) and using rabbit anti-phospho-p38 (p-p38) antibody, rabbit anti-p38 antibody, and rabbit anti-GAPDH (I).

To further address the underlying mechanisms whereby C5a enhances IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production, we explored the influence of C5a on MAPK pathways. As shown in Fig. 7, H and I, C5a treatment further increased both phospho-p38 and phospho-p44/42 levels induced by IgG IC in RAW264.7 cells. Taken together, these data indicate that C5a enhances IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production by elevating phospho-p38 and phospho-p44/42 levels, which lead to increased C/EBPβ and -δ activities.

DISCUSSION

Macrophage FcγR activation plays a central role in the immune defense system (1, 2). However, the signaling pathways from FcγRs to the nucleus remain largely unknown. In the current study, we provide the evidence that C/EBPβ and -δ are key transcription factors that regulate FcγR-mediated induction of inflammatory cytokine and chemokines in macrophages. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that C/EBPs are key regulators of immune complex-induced inflammatory responses.

Increasing evidence suggests an important role for C/EBPs, such as C/EBPβ and -δ, in inflammation (12, 34, 35). For example, C/EBPβ has been shown to be an effector in the induction of acute phase and inflammatory genes responsive to LPS, IL-1, or IL-6 (36, 37). C/EBPδ has been less well characterized than C/EBPβ. However, similarly to C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ has also been implicated in regulation of the acute phase and inflammatory responses (38, 39). Interestingly, a recent study demonstrates a critical function for C/EBPδ in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4 stimulation (34). In another recent study, Maitra et al. (21) show that C/EBPδ is the key mediator to initiate low dose endotoxin-induced inflammation. Functional C/EBP binding sites have been identified in the promoter regions of the TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α (3, 40–42). For example, C/EBPβ has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of the TNF-α gene in myelomonocytic cells (40). Furthermore, serial and site-directed deletion mutants of MIP-2 luciferase reporter genes demonstrate that the binding sites for both C/EBPβ and NF-κB are essential for the activity of the MIP-2 promoter in response to nitric oxide (41). In addition, a recent study suggests that C/EBPβ and NF-κB are both involved in the IL-1β-responsive up-regulation of MIP-1α genes in chondrocytes (42). Using monocytic cells, Fernández et al. (3) recently showed that cross-linking of FcγR induced C/EBPβ DNA binding to its binding site in the MIP-1α promoter, which suggests the possible involvement of C/EBPβ in IC-induced MIP-1α expression. However, whether and to what extent C/EBPβ and -δ contribute to FcγR-mediated inflammatory mediator production has been unclear. Our study shows that C/EBPα and -β are expressed in unstimulated macrophages, and IgG IC stimulation up-regulates C/EBPβ and -δ activities. Using an siRNA-mediated knockdown approach and mice deficient for C/EBPβ or/and -δ, our results clearly demonstrate that C/EBPβ and -δ play critical roles in the production of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α in IgG IC-stimulated macrophages. Interestingly, the functions of C/EBPβ and -δ seem to be partially redundant, although lack of either protein has a significant effect on TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α production. This could also indicate the importance of C/EBPβ and -δ heterodimer occupancy in regulating these promoters. This is further supported by data showing that co-expression of C/EBPβ- and C/EBPδ-expressing vectors stimulated a C/EBP-driven luciferase reporter significantly more strongly than either C/EBPβ or C/EBPδ alone (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, because a relatively low level of DNA binding for C/EBPδ contributes a vigorous induction of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α, it is tempting to speculate that C/EBPδ may be more effective than C/EBPβ in supporting the IgG IC-induced transcription of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α genes.

Although the primary mechanism of C/EBPβ regulation within inflammatory responses appears to be post-transcriptional (43), C/EBPβ mRNA levels are also induced by inflammatory stimuli, including LPS (36). On the other hand, unlike C/EBPβ, the primary mechanism of C/EBPδ regulation within the inflammatory responses is transcriptional (38, 43). For example, LPS, IL-1, and IL-6 all can induce C/EBPδ at the mRNA level (37). Here we show for the first time that IgG IC induces C/EBPβ and -δ expression at both mRNA and protein levels. Furthermore, the DNA binding activities of both C/EBPβ and -δ are increased upon FcγR activation, although whether this is due solely to increased expression of the proteins versus post-translational regulation of C/EBP protein activity is unknown and requires further investigation.

Using MAPK inhibitors, previous studies have shown that activation of MAPK is necessary for the FcγR-dependent induction of TNF-α expression in monocytes (44). Furthermore, FcγR ligation of monocytes/macrophages leads to both ERK1/2 and p38 activation (45, 46). In addition, Song et al. (47) demonstrated that in microglia, the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway was necessary and sufficient for IC-induced MIP-1α expression. Thus, our finding that IgG IC treatment leads to the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK is consistent with these previous reports. Importantly, our results suggest that both ERK and p38 MAPK pathways are involved in IgG IC-induced C/EBPβ and -δ activation, thus stimulating cytokine and chemokine production in macrophages. Interestingly, neither ERK nor p38 MAPK affects NF-κB DNA binding activity, suggesting that other signaling pathways are involved in its activation by IgG IC. This is consistent with a previous report showing that a MEK inhibitor failed to affect IC-induced p65 nuclear translocation in microglia (47). In contrast, other studies have suggested that MAPK activation is necessary for FcγR-dependent activation of NF-κB in monocytes (48–50). Collectively, however, these data do not exclude the requirement for NF-κB activation in FcγR-mediated inflammation. In the current study, IgG IC-stimulated production of TNF-α, MIP-2, and MIP-1α is inhibited by a NF-κB inhibitor with a significant effect observed on TNF-α and MIP-1α levels (supplemental Fig. 2). These data suggest that NF-κB may play important but differential regulatory roles in FcγR-mediated inflammatory mediator production.

Products of macrophages play a major role in events leading to tissue injury. TNF-α, other cytokines, and chemokines, such as MIP-2 and MIP-1α, secreted by macrophages have been shown to modulate the cell signaling cascades for the production of other proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators during inflammation. The coordinate expression of activating and inhibitory FcγRs on macrophages and other cells thus ensures the homeostasis of IC-induced inflammatory responses. For example, genetic deletion of FcR γ-chain, which leads to the loss of cell surface expression and functional inactivation of all three activating FcγRs, results in dramatically impaired inflammatory responses associated with IC formation (1, 28). In contrast, enhanced macrophage responses were observed in FcγRII knock-out mice (1, 28). Using macrophages from mice lacking FcR γ-chain (FcRγ), we demonstrated that activation of C/EBPβ and -δ in macrophages by IgG IC stimulation is mediated, to a large extent, by activating FcγRs. Furthermore, we showed an enhanced C/EBP DNA binding activity in macrophages from FcγRII-deficient mice (data not shown). These data further suggest that activation of C/EBPβ and -δ may function as a pivotal regulatory mechanism of IgG IC-associated responses.

Perhaps one of the most interesting results reported here is that C5a enhances IgG IC-induced cytokine and chemokine production by elevating C/EBPs but not NF-κB DNA binding activities. However, the exact mechanism whereby C5a signals control C/EBP activation remains an important open question. Several proinflammatory cytokines and mediators, such as TNF, interferon-γ, and LPS have been shown to up-regulate activating FcγR (1, 28, 51). Recent studies have shown that C5a causes induction of FcγRIII and suppression of FcγRII on both alveolar macrophages and RAW264.7 cells (31, 52, 53). Furthermore, genetic ablation of C5aR expression completely abolished this regulation of FcγRs. These studies provide definite evidence that C5a plays a critical role in regulating the FcγR III/II pair to connect complement and FcγR pathways during IC-associated inflammation. Moreover, our current data suggest that the enhancement by C5a of C/EBP activity may be mediated by increased phospho-p38 and phospho-p44/42 levels. Interestingly, our finding that C5a/C5aR has no effect on IgG IC-induced NF-κB activation suggests that the C5a/C5aR pathway may have a specific role in C/EBP activation.

In summary, we report here that FcγR-mediated activation of C/EBPβ and -δ leads to cytokine and chemokine production from IgG IC-stimulated macrophages, and both MAPKs and C5a signal pathways are involved in C/EBP activation. These data support an important regulatory role of C/EBPβ and -δ in immune complex-associated inflammatory responses. Understanding the underlying roles of various transcription factors in regulating the network of inflammatory system may be a crucial step for the development of new therapeutic drugs for treatment of immune complex diseases.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Craig Gerard (Harvard Medical School) for providing C5aR−/− mice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants 5R01HL092905-04 and 3R01HL092905-02S1 (to H. G.) and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptor

- IC

- immunocomplex(es)

- C/EBP

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

- LAP

- liver-enriched activating protein

- LIP

- liver-enriched inhibitory protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2008) Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 34–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Halstead S. B., Mahalingam S., Marovich M. A., Ubol S., Mosser D. M. (2010) Intrinsic antibody-dependent enhancement of microbial infection in macrophages. Disease regulation by immune complexes. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10, 712–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fernández N., Renedo M., García-Rodríguez C., Sánchez Crespo M. (2002) Activation of monocytic cells through Fc γ receptors induces the expression of macrophage-inflammatory protein (MIP)-1 α, MIP-1 β, and RANTES. J. Immunol. 169, 3321–3328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao H., Neff T., Ward P. A. (2006) Regulation of lung inflammation in the model of IgG immune-complex injury. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1, 215–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayón Y., Alonso A., Sánchez Crespo M. (1997) Stimulation of Fc γ receptors in rat peritoneal macrophages induces the expression of nitric oxide synthase and chemokines by mechanisms showing different sensitivities to antioxidants and nitric oxide donors. J. Immunol. 159, 887–894 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmal H., Czermak B. J., Lentsch A. B., Bless N. M., Beck-Schimmer B., Friedl H. P., Ward P. A. (1998) Soluble ICAM-1 activates lung macrophages and enhances lung injury. J. Immunol. 161, 3685–3693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Descombes P., Schibler U. (1991) A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell 67, 569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tanaka T., Akira S., Yoshida K., Umemoto M., Yoneda Y., Shirafuji N., Fujiwara H., Suematsu S., Yoshida N., Kishimoto T. (1995) Targeted disruption of the NF-IL6 gene discloses its essential role in bacteria killing and tumor cytotoxicity by macrophages. Cell 80, 353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Uematsu S., Kaisho T., Tanaka T., Matsumoto M., Yamakami M., Omori H., Yamamoto M., Yoshimori T., Akira S. (2007) The C/EBP β isoform 34-kDa LAP is responsible for NF-IL-6-mediated gene induction in activated macrophages but is not essential for intracellular bacteria killing. J. Immunol. 179, 5378–5386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsumoto M., Tanaka T., Kaisho T., Sanjo H., Copeland N. G., Gilbert D. J., Jenkins N. A., Akira S. (1999) A novel LPS-inducible C-type lectin is a transcriptional target of NF-IL6 in macrophages. J. Immunol. 163, 5039–5048 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uematsu S., Matsumoto M., Takeda K., Akira S. (2002) Lipopolysaccharide-dependent prostaglandin E2 production is regulated by the glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E2 synthase gene induced by the Toll-like receptor 4/MyD88/NF-IL6 pathway. J. Immunol. 168, 5811–5816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cloutier A., Guindi C., Larivée P., Dubois C. M., Amrani A., McDonald P. P. (2009) Inflammatory cytokine production by human neutrophils involves C/EBP transcription factors. J. Immunol. 182, 563–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gorgoni B., Maritano D., Marthyn P., Righi M., Poli V. (2002) C/EBP β gene inactivation causes both impaired and enhanced gene expression and inverse regulation of IL-12 p40 and p35 mRNAs in macrophages. J. Immunol. 168, 4055–4062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cox G. W., Mathieson B. J., Gandino L., Blasi E., Radzioch D., Varesio L. (1989) Heterogeneity of hematopoietic cells immortalized by v-myc/v-raf recombinant retrovirus infection of bone marrow or fetal liver. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 81, 1492–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sterneck E., Paylor R., Jackson-Lewis V., Libbey M., Przedborski S., Tessarollo L., Crawley J. N., Johnson P. F. (1998) Selectively enhanced contextual fear conditioning in mice lacking the transcriptional regulator CCAAT/enhancer binding protein δ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10908–10913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sterneck E., Tessarollo L., Johnson P. F. (1997) An essential role for C/EBPβ in female reproduction. Genes Dev. 11, 2153–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rittirsch D., Flierl M. A., Day D. E., Nadeau B. A., Zetoune F. S., Sarma J. V., Werner C. M., Wanner G. A., Simmen H. P., Huber-Lang M. S., Ward P. A. (2009) Cross-talk between TLR4 and FcγReceptor III (CD16) pathways. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poli V. (1998) The role of C/EBP isoforms in the control of inflammatory and native immunity functions. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29279–29282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anastasov N., Bonzheim I., Rudelius M., Klier M., Dau T., Angermeier D., Duyster J., Pittaluga S., Fend F., Raffeld M., Quintanilla-Martinez L. (2010) C/EBPβ expression in ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphomas is required for cell proliferation and is induced by the STAT3 signaling pathway. Haematologica 95, 760–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lu Y. C., Kim I., Lye E., Shen F., Suzuki N., Suzuki S., Gerondakis S., Akira S., Gaffen S. L., Yeh W. C., Ohashi P. S. (2009) Differential role for c-Rel and C/EBPβ/δ in TLR-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 182, 7212–7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maitra U., Gan L., Chang S., Li L. (2011) Low-dose endotoxin induces inflammation by selectively removing nuclear receptors and activating CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ. J. Immunol. 186, 4467–4473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Widmer U., Manogue K. R., Cerami A., Sherry B. (1993) Genomic cloning and promoter analysis of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, MIP-1 α, and MIP-1 β, members of the chemokine superfamily of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 150, 4996–5012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolpe S. D., Sherry B., Juers D., Davatelis G., Yurt R. W., Cerami A. (1989) Identification and characterization of macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 612–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolpe S. D., Davatelis G., Sherry B., Beutler B., Hesse D. G., Nguyen H. T., Moldawer L. L., Nathan C. F., Lowry S. F., Cerami A. (1988) Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J. Exp. Med. 167, 570–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davatelis G., Tekamp-Olson P., Wolpe S. D., Hermsen K., Luedke C., Gallegos C., Coit D., Merryweather J., Cerami A. (1988) Cloning and characterization of a cDNA for murine macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP), a novel monokine with inflammatory and chemokinetic properties. J. Exp. Med. 167, 1939–1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolpe S. D., Cerami A. (1989) Macrophage inflammatory proteins 1 and 2. Members of a novel superfamily of cytokines. FASEB J. 3, 2565–2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oppenheim J. J., Zachariae C. O., Mukaida N., Matsushima K. (1991) Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene “intercrine” cytokine family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 9, 617–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J. V. (2007) Fc receptors as regulators of immunity. Adv. Immunol. 96, 179–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akagi T., Luong Q. T., Gui D., Said J., Selektar J., Yung A., Bunce C. M., Braunstein G. D., Koeffler H. P. (2008) Induction of sodium iodide symporter gene and molecular characterization of HNF3 β/FoxA2, TTF-1, and C/EBP β in thyroid carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 99, 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bianchi G., Montecucco F., Bertolotto M., Dallegri F., Ottonello L. (2007) Immune complexes induce monocyte survival through defined intracellular pathways. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1095, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shushakova N., Skokowa J., Schulman J., Baumann U., Zwirner J., Schmidt R. E., Gessner J. E. (2002) C5a anaphylatoxin is a major regulator of activating versus inhibitory FcγRs in immune complex-induced lung disease. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1823–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bless N. M., Warner R. L., Padgaonkar V. A., Lentsch A. B., Czermak B. J., Schmal H., Friedl H. P., Ward P. A. (1999) Roles for C-X-C chemokines and C5a in lung injury after hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. 276, L57–L63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumar V., Ali S. R., Konrad S., Zwirner J., Verbeek J. S., Schmidt R. E., Gessner J. E. (2006) Cell-derived anaphylatoxins as key mediators of antibody-dependent type II autoimmunity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 512–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Litvak V., Ramsey S. A., Rust A. G., Zak D. E., Kennedy K. A., Lampano A. E., Nykter M., Shmulevich I., Aderem A. (2009) Function of C/EBPδ in a regulatory circuit that discriminates between transient and persistent TLR4-induced signals. Nat. Immunol. 10, 437–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adelmant G., Gilbert J. D., Freytag S. O. (1998) Human translocation liposarcoma-CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (TLS-CHOP) oncoprotein prevents adipocyte differentiation by directly interfering with C/EBPβ function. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 15574–15581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akira S., Isshiki H., Sugita T., Tanabe O., Kinoshita S., Nishio Y., Nakajima T., Hirano T., Kishimoto T. (1990) A nuclear factor for IL-6 expression (NF-IL6) is a member of a C/EBP family. EMBO J. 9, 1897–1906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Y., Rom W. N. (1993) Regulation of the interleukin-1 β (IL-1 β) gene by mycobacterial components and lipopolysaccharide is mediated by two nuclear factor-IL6 motifs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 3831–3837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kinoshita S., Akira S., Kishimoto T. (1992) A member of the C/EBP family, NF-IL6 β, forms a heterodimer and transcriptionally synergizes with NF-IL6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 1473–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alam T., An M. R., Papaconstantinou J. (1992) Differential expression of three C/EBP isoforms in multiple tissues during the acute phase response. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 5021–5024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pope R. M., Leutz A., Ness S. A. (1994) C/EBP β regulation of the tumor necrosis factor α gene. J. Clin. Invest. 94, 1449–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walpen S., Beck K. F., Schaefer L., Raslik I., Eberhardt W., Schaefer R. M., Pfeilschifter J. (2001) Nitric oxide induces MIP-2 transcription in rat renal mesangial cells and in a rat model of glomerulonephritis. FASEB J 15, 571–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arnett B., Soisson P., Ducatman B. S., Zhang P. (2003) Expression of CAAT enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP β) in cervix and endometrium. Mol. Cancer 2, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramji D. P., Vitelli A., Tronche F., Cortese R., Ciliberto G. (1993) The two C/EBP isoforms, IL-6DBP/NF-IL6 and C/EBP δ/NF-IL6 β, are induced by IL-6 to promote acute phase gene transcription via different mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 289–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Trotta R., Kanakaraj P., Perussia B. (1996) Fc γ R-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in leukocytes. A common signal transduction event necessary for expression of TNF-α and early activation genes. J. Exp. Med. 184, 1027–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hillyard D. Z., Jardine A. G., McDonald K. J., Cameron A. J. (2004) Fluvastatin inhibits raft-dependent Fcγ receptor signaling in human monocytes. Atherosclerosis 172, 219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lucas M., Zhang X., Prasanna V., Mosser D. M. (2005) ERK activation following macrophage FcγR ligation leads to chromatin modifications at the IL-10 locus. J. Immunol. 175, 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Song X., Tanaka S., Cox D., Lee S. C. (2004) Fcγ receptor signaling in primary human microglia. Differential roles of PI-3K and Ras/ERK MAPK pathways in phagocytosis and chemokine induction. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 1147–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sánchez-Mejorada G., Rosales C. (1998) Fcγ receptor-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in monocytes is independent of Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27610–27619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. García-García E., Sánchez-Mejorada G., Rosales C. (2001) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and ERK are required for NF-κB activation but not for phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70, 649–658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nakano H., Shindo M., Sakon S., Nishinaka S., Mihara M., Yagita H., Okumura K. (1998) Differential regulation of IκB kinase α and β by two upstream kinases, NF-κB-inducing kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3537–3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gerbitz A., Ewing P., Olkiewicz K., Willmarth N. E., Williams D., Hildebrandt G., Wilke A., Liu C., Eissner G., Andreesen R., Holler E., Guo R., Ward P. A., Cooke K. R. (2005) A role for CD54 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1) in leukocyte recruitment to the lung during the development of experimental idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Transplantation 79, 536–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Konrad S., Engling L., Schmidt R. E., Gessner J. E. (2007) Characterization of the murine IgG Fc receptor III and IIB gene promoters. A single two-nucleotide difference determines their inverse responsiveness to C5a. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37906–37912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Konrad S., Ali S. R., Wiege K., Syed S. N., Engling L., Piekorz R. P., Hirsch E., Nürnberg B., Schmidt R. E., Gessner J. E. (2008) Phosphoinositide 3-kinases γ and δ, linkers of coordinate C5a receptor-Fcγ receptor activation and immune complex-induced inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33296–33303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]