Background: The transcription factor Late SV40 Factor (LSF) is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Results: LSF augments tumor angiogenesis by transcriptionally up-regulating matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9).

Conclusion: A novel target of LSF is identified contributing to its oncogenic properties.

Significance: LSF regulates a network of proteins, including osteopontin, MMP-9, and c-Met, thereby establishing the rationale for LSF inhibition as a potential therapeutic strategy for HCC.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChiP), Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP), Metastasis, Transcription, LSF

Abstract

The transcription factor late SV40 factor (LSF) is overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) fostering a highly aggressive and metastatic phenotype. Angiogenesis is an essential component of cancer aggression and metastasis and HCC is a highly aggressive and angiogenic cancer. In the present studies, we analyzed the molecular mechanism of LSF-induced angiogenesis in HCC. Employing human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) differentiation assay and chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay we document that stable LSF overexpression augments and stable dominant negative inhibition of LSF (LSFdn) abrogates angiogenesis by human HCC cells. A quest for LSF-regulated factors contributing to angiogenesis, by chromatin immunoprecipitation-on-chip (ChIP-on-chip) assay, identified matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a direct target of LSF. MMP-9 expression and enzymatic activity were higher in LSF-overexpressing cells and lower in LSFdn-expressing cells. Deletion mutation analysis identified the LSF-responsive regions in the MMP-9 promoter and ChIP assay confirmed LSF binding to the MMP-9 promoter. Inhibition of MMP-9 significantly abrogated LSF-induced angiogenesis as well as in vivo tumorigenesis, thus reinforcing the role of MMP-9 in facilitating LSF function. The present findings identify a novel target of LSF contributing to its oncogenic properties.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),3 one of the five most common cancers worldwide, is a highly aggressive disease (1). We previously documented that the transcription factor late SV40 factor (LSF), also known as TFCP2, is overexpressed in more than 90% of cases of human HCC patients compared with normal liver and a direct correlation exists between LSF expression levels and the stages and grades of the disease (2). LSF expression is low in the human HCC cell line HepG3, which do not form tumors in nude mice, while it is highly expressed in the human HCC cell line QGY-7703 that forms aggressive tumors in nude mice (2). Forced overexpression of LSF in HepG3 cells increased proliferation, colony formation, Matrigel invasion and anchorage-independent growth in vitro and resulted in highly aggressive and multi-organ metastatic tumors in nude mice. Conversely, inhibition of LSF by a dominant negative construct (LSFdn) in QGY-7703 cells significantly suppressed in vitro proliferation, colony formation, Matrigel invasion, and anchorage-independent growth and in vivo tumor growth and metastasis. LSF transcriptionally up-regulates osteopontin (OPN), a known mediator for tumor progression and metastasis, and inhibition of OPN significantly nullifies the oncogenic functions of LSF (2). OPN, induced by LSF, activates c-Met receptor, via interaction with CD44, and our recent studies document that c-Met activation also plays a crucial role in mediating aggressive properties conferred by LSF (3). We also documented that by regulating the expression of thymidylate synthase (TS), LSF contributes to cell survival and cell cycle regulation (4). Since TS is the target of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), TS up-regulation as a consequence of LSF overexpression leads to 5-FU resistance (4). Thus LSF augments HCC progression and metastasis by altering multiple physiologically important pathways.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopetidases that play a critical role in promoting extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, invasion, and metastasis by tumor cells (5). Among the MMPs, MMP-9 is overexpressed in many tumors including HCC and studies using knock-out mouse models have confirmed the role of MMP-9 in invasive, aggressive, and metastatic tumors (6–11). High serum levels of MMP-9 is linked to rapid progression, poor survival, and secondary metastasis in multiple cancer indications (12–14). Tumor-induced angiogenesis is important to sustain growth of solid tumors when they become invasive and metastatic and the functional role of MMPs in tumor angiogenesis is well established (15). MMP-9 is a major contributor to tumor-induced angiogenesis and a crucial factor triggering activation of quiescent vasculature (16, 17). MMP-9 degrades ECM allowing invasion of pericytes that stabilizes newly-formed capillaries, sustain blood flow, modulate vascular permeability, and regulate the function of endothelial cells (18). Inhibition of MMP-9 results in inhibition of expression of pro-angiogenic genes, such as VEGF and ICAM-1, further establishing the importance of MMP-9 in regulating angiogenesis (19). Accordingly, MMP-9 plays an important role in aggressive progression of cancer.

In the present studies we document that LSF transcriptionally up-regulates MMP-9, which plays a fundamental role in mediating the pro-angiogenic properties of LSF. The present results are novel and identify a unique effector of LSF function that might provide a target to counteract HCC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, Viability, Clonogenic, and Invasion Assays

HepG3 clones stably expressing LSF (LSF-1 and LSF-17) and QGY-7703 clones stably expressing LSFdn (QGY-LSFdn-8 and QGY-LSFdn-15) were generated as described (2). Human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from Lonza and maintained as recommended. The LSF-17 clone of HepG3 cells was transduced with a pool of three to five lentiviral vector plasmids, each encoding target-specific 19–25 nt (plus hairpin) shRNAs designed to knockdown MMP-9 gene expression (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Individual colonies were selected by puromycin for 2 weeks to generate the MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 clones. Control scrambled shRNA was used in a similar manner to generate the Con-11 clone in the LSF-17 background. Cell viability was determined by standard MTT assays as described (2). For colony formation assay, cells (500) were plated in 6-cm dishes and colonies >50 cells were counted after 2 weeks (2). Matrigel invasion was performed as described (2).

Cloning of Human MMP-9 Promoter

∼2 kb fragment of human MMP-9 promoter (−1936 to +24 when the translation start site was regarded as +1) was cloned by PCR using human genomic DNA as template and primers, sense: 5′-GCTAGCGCTGGAAAATGGCAGAG-3′ and antisense: 5′-CTCGAGGACCAGGGGCTGCCAGA-3′ and was cloned into the NheI and XhoI sites of pGL3-basic vector (Promega) to generate MMP-9-Prom-luc construct. N1 and N2 deletion mutants were created by PCR using MMP-9-Prom-luc as template and sense primers, 5′-GCTAGCGGAGGCTTGGCATAAGTG-3′ and 5′-GCTAGCAGACATTTGCCCGAGGTC-3′, respectively and with the aforementioned antisense primer and cloned into pGL3-basic vector.

Transfection and Luciferase Assays

Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were transfected with empty vector (pGL3-basic), MMP-9-Prom-luc or its deletion mutants and Renilla luciferase expression plasmid for transfection control (2). Luciferase assays were measured using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol and firefly luciferase activity was normalized by Renilla luciferase activity.

Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assays

CAM surface of 9-day-old chick embryos were treated with conditioned media (CM) from cells according to established protocols (20). One week after inoculation, the neovasculature was examined and photographed. Angiogenesis was quantified by counting the blood vessel branch points under a stereomicroscope. The angiogenic index was calculated by subtracting the number of branch points from the branching in the control group.

Capillary-like Tube Formation Assays

Tube formation by human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) was performed using Cultrex basement membrane extract (R&D Systems) as described (21). In some experiments, HUVEC were treated with recombinant active MMP-9 (83 kDa; EMD Chemicals, Inc.). Images were captured using an inverted microscope (Nikon) and the degree of network formation was quantified using an Image analyzer (National Institutes of Health Image).

Human Angiogenesis Array

The expression levels of 55 angiogenesis associated proteins were analyzed using conditioned media from cells cultured in serum-free condition with the Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array kit (R&D Systems, Proteome ProfilerTM) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Gelatin Zymography

MMP-9 activity was determined by gelatin zymography (22). Fifty micrograms of protein from culture supernatants were electrophoresed on a Novex® 10% Zymogram (Gelatin) Gel (Invitrogen) as recommended. The gel was stained with SimplyBlue Safe Stain (Invitrogen) and photographed.

ChIP Assays

ChIP assays were performed using a kit from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA) as described (2). The immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR using primers, sense: 5′-CGATGCCGGCTGGCTAGGAAG-3′ and antisense: 5′-AGCTTAGGATTCTTCAACTGC-3′ for fragment A; sense: 5′-GGGGAAGGCATTTACTCCAGG-3′ and antisense: 5′-GAGGCCGAGGTGGGAGGATTG-3′ for fragment B; and sense: 5′-AGGAATGAGCCACCATACCTG-3′ and antisense: 5′-TTTGAAGTGTTTCCTCAGCTG-3′ for fragment C.

ChIP-on-Chip Assay

ChIP was performed using anti-LSF antibody and lysates from LSF-17 and QGY-7703 cells and the immunoprecipitated DNA was used to screen Roche Nimblegen's ChIP-on-Chip 2.1 m tiling array according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using serum-free conditioned media which was concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore). 50 μg of protein/sample were subjected to Western blot analysis as described (2). The primary antibody for MMP-9 was obtained from Millipore (mouse monoclonal; clone 56–2A4; 1:500 dilution).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Analysis (ELISA)

The expression of IL-8 and VEGF was analyzed in conditioned media using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, QuantakineR) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Nude Mice Xenograft Studies

Subcutaneous xenografts were established in the flanks of athymic nude mice using 1 × 106 different clones of HCC cells (2). Tumor volume was measured twice weekly with a caliper and calculated using the formula π/6 × larger diameter × (smaller diameter)2. For the metastasis assays, 1 × 106 cells were intravenously injected through the tail vein in nude mice. The lungs were isolated and analyzed after 6 weeks. All experiments were performed with at least 5 mice in each group, and all experiments were repeated three times.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor sections was performed as described (2). The primary antibody was anti-CD31 (1:200, mouse monoclonal, Dako).

Statistical Analysis

Data were represented as the mean ± S.E. and analyzed for statistical significance using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Newman-Keuls test as a post hoc test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

LSF Induces Angiogenesis

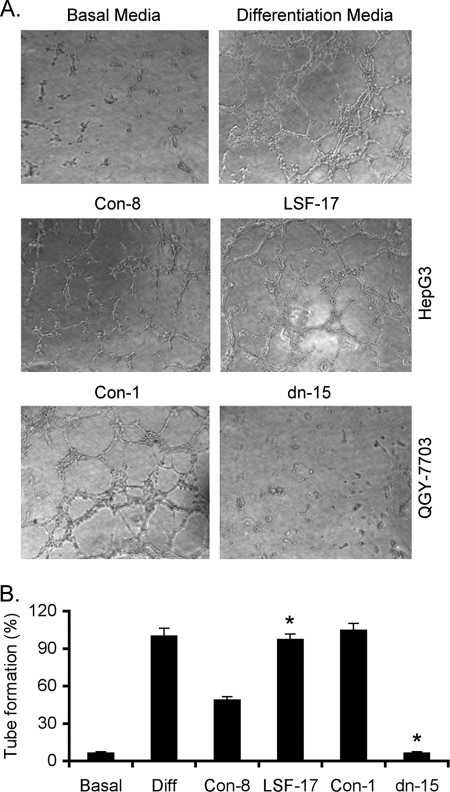

HepG3 is a human HCC cell line that is poorly aggressive, non-tumorigenic in nude mice and expresses low level of LSF (2). In contrast, QGY-7703 is a highly aggressive, metastatic human HCC cell line that expresses high levels of LSF (2). We established stable cell lines overexpressing LSF in HepG3 background (LSF-1 and LSF-17) and documented that these clones form highly aggressive, multi-organ metastatic tumors in nude mice (2). Conversely, we established stable cell lines expressing an LSF dominant negative mutant in a QGY-7703 background (LSFdn-8 and LSFdn-15) that resulted in profound inhibition in tumor growth and metastasis in nude mice when compared with control clones (2). Because angiogenesis is an integral component of aggressive and metastatic tumors, we analyzed the angiogenic potential of LSF using these established cell clones. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), cultured in the presence of differentiation media on basement membrane extract, rapidly align, extend processes into the matrix, and finally form capillary-like structures surrounding a central lumen (Fig. 1). HUVEC cultured in conditioned medium (CM) from LSF-17 clone showed significant tube formation compared with Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells (Fig. 1). As a corollary, CM from LSFdn-15 clone induced extremely poor tube formation compared with that from Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells, which induced robust HUVEC differentiation (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

LSF induces differentiation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). A, HUVECs were cultured in either basal media or differentiation media or treated with conditioned media (CM) from the indicated cells and tube formation was photographed. B, graphical representation of percentage of tube formation by HUVEC treated as in A when tube formation in differentiation media was considered as 100%. The data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

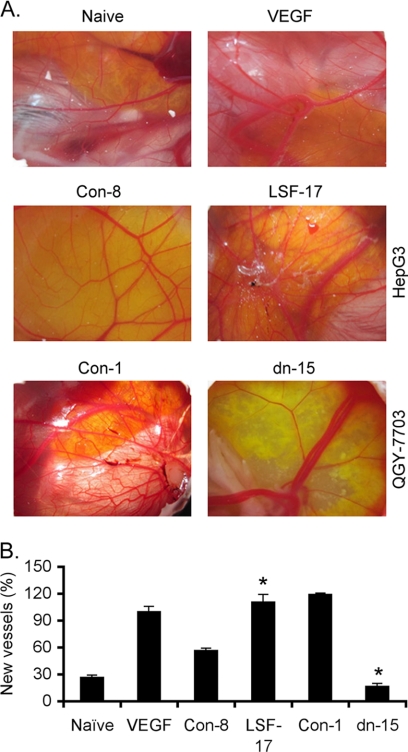

The pro-angiogenic property of LSF was further characterized by treating CAM of 9-day old chick embryos either with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as positive control or with CM from LSF-overexpressing and LSF-inhibited clones. After 1 week, neovascularization was examined, photographed and quantified. Significantly marked outgrowth of new blood vessels was observed in the presence of VEGF (Fig. 2). CM from the LSF-17 clone resulted in significant neovascularization compared with the Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells (Fig. 2). Conversely, CM from LSFdn-15 clone exhibited little induction of neovascularization compared with that from the Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells (Fig. 2). In HepG3 cells, LSF overexpression increased while in QGY-7703 cells LSF inhibition decreased the migration ability as revealed by a wound healing assay (supplemental Fig. S1). The observation that inhibition of LSF resulted in such a profound inhibition of both HUVEC differentiation and neovascularization in CAM suggests that LSF plays a pivotal role in regulating angiogenesis.

FIGURE 2.

LSF induces neovascularization in CAM assay. A, CAM was treated either with VEGF (positive control) or with CM from the indicated cells and neovascularization was photographed. B, graphical representation of percentage of new blood vessel formation in CAM treated as in A when VEGF-treated CAM was considered as 100%. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

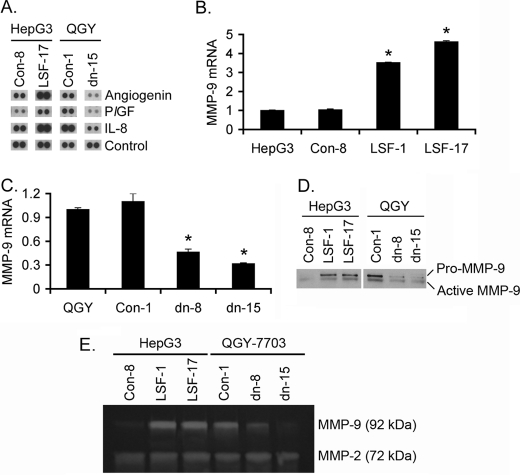

LSF Induces Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9)

To determine which angiogenic factors contribute to LSF-induced angiogenesis, we screened a human angiogenesis array using CM from Con-8 and LSF-17 clones of HepG3 cells and CM from Con-1 and LSFdn-15 clones of QGY-7703 cells. We only focused on those factors that showed increase in LSF-17 clone with corresponding decrease in LSFdn-15 clones. A significant increase in angiogenin and placental growth factor (PlGF) and a moderate increase in interleukin-8 (IL-8) were observed in LSF-17 clone compared with Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells (Fig. 3A). Corresponding decreases in angiogenin, PlGF and IL-8 were observed in LSFdn-15 clone compared with Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells (Fig. 3A). Although not evident from the array, analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level by ELISA revealed modest increase in LSF-17 clone compared with Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells and modest decrease in LSFdn-15 clone compared with Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells (supplemental Fig. S2). Analysis of the promoter region of these genes did not reveal any LSF-binding sites indicating that as a transcription factor LSF does not directly induce their expression. To identify a master regulator of angiogenesis that might be transcriptionally regulated by LSF, we performed ChIP-on-chip analysis Using Roche Nimblegen's ChIP-on-chip 2.1 m tiling array that allows identification of promoter regions to which a specific transcription factor binds. The promoter region of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) exhibited the highest statistical significance in terms of LSF binding. MMP-9 mRNA expression was significantly higher in LSF-1 and LSF-17 clones compared with Con-8 clone as well as parental HepG3 cells and was significantly decreased in LSFdn-8 and LSFdn-15 clones compared with Con-1 clone as well as parental QGY-7703 cells (Fig. 3, B and C). As a corollary Pro-MMP-9 and cleaved (active) forms of MMP-9 were significantly increased in LSF-1 and LSF-17 clones compared with Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells and was significantly decreased in LSFdn-8 and LSFdn-15 clones compared with Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells when the conditioned media were subjected to Western blot analysis (Fig. 3D). An increase in functionally active MMP-9 in LSF-1 and LSF-17 clones over Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells and a corresponding decrease in LSFdn-8 and LSFdn-15 clones over Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells were demonstrated by gelatin zymography assay (Fig. 3E). No change in MMP-2 level was detected by gelatin zymography indicating that LSF regulates MMP-9 but not MMP-2.

FIGURE 3.

LSF induces MMP-9. A, human angiogenesis array was screened using conditioned media (CM) from the indicated cells. Representative expression levels of Angiogenin, PlGF, and IL-8 are shown. MMP-9 mRNA expression was detected in parental HepG3 cells and its LSF-overexpressing clones (B) and in parental QGY-7703 cells and its LSF dominant negative-expressing clones (C) by real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. D, analysis of Pro- and active MMP-9 by Western blot analysis using conditioned media from the indicated cells. E, functionally active MMP-9 level was determined in the indicated cells by gelatin zymography.

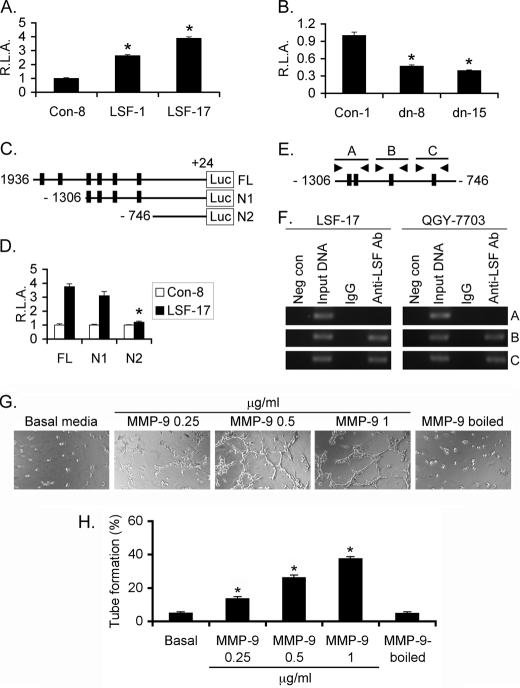

To confirm transcriptional regulation of MMP-9 by LSF, we cloned ∼2 kb region of human MMP-9 gene starting from −1936 to +24 when the translation start site was regarded as +1. A luciferase reporter construct under the control of the MMP-9 promoter was generated in the pGL3-basic vector (MMP-9-Prom-luc). MMP-9-Prom-luc was transfected into the cells along with a Renilla luciferase expression plasmid and firefly luciferase activity was normalized by Renilla luciferase activity. MMP-9 promoter activity was significantly higher in LSF-1 and LSF-17 clones when compared with the Con-8 clone of HepG3 cells while it was significantly decreased in the LSFdn-8 and LSFdn-15 clones versus the Con-1 clone of QGY-7703 cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Analysis of MMP-9 promoter region identified six potential LSF-binding sites. We generated two deletion mutants, N1 containing −1306/+24 region with removal of two LSF binding sites and N2 containing −746/+24 with removal of the remaining four LSF binding sites (Fig. 4C). The N1 construct still retained LSF-mediated induction while LSF-responsiveness was completely extinguished in the N2 construct indicating that the four potential LSF binding elements between −1306 and −746 contribute to LSF responsiveness (Fig. 4D). Two of these four elements are closely positioned to each other and as such we designed three sets of PCR primers, the first pair flanking the distal two LSF binding sites (fragment A), while the other two pairs flanked the remaining two LSF binding sites (fragments B and C, respectively), to confirm direct binding of LSF to MMP-9 promoter by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) (Fig. 4E). ChIP assay using the LSF-17 clone of HepG3 cells and QGY-7703 cells demonstrated LSF binding only to the proximal two LSF-binding sites and not to the distal sites (Fig. 4F). These results confirm that LSF transcriptionally up-regulates MMP-9.

FIGURE 4.

LSF transcriptionally up-regulated MMP-9. Control-8, LSF-1, and LSF-17 clones of HepG3 cells (A) and Control-1, LSFdn-8, and LSFdn-15 clones of QGY-7703 cells (B) were transfected with pGL3-basic vector or MMP-9-Prom-luc along with Renilla luciferase expression vector. Luciferase assay was performed 2 days later, and firefly luciferase activity was normalized by Renilla luciferase activity. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. C, schematic representation of the N1 and N2 deletion mutants of MMP-9-Prom-luc (FL) construct. The numbers represent nucleotide position when the translation initiation site was regarded as +1. D, MMP-9-Prom-luc (FL) and its N1 and N2 deletion mutants were transfected in Control-8 and LSF-17 clones of HepG3 cells, and luciferase assay was performed as in A. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. E, schematic diagram of MMP-9 promoter showing the location of potential LSF-binding sites in the promoter and primers designed for ChIP assay. Fragment A, B, and C represent 195, 192, and 204 bp fragments. F, ChIP assay to detect LSF binding to the MMP-9 promoter. G, MMP-9 induces HUVEC differentiation. HUVEC were treated with the indicated concentrations of MMP-9 or MMP-9 (1 μg/ml) that was inactivated by boiling and were subjected to tube formation assay. Photomicrographs of tube formation are shown. H, graphical representation of percentage of tube formation by HUVEC treated as in G when tube formation in differentiation media was considered as 100%. The data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

MMP-9 Mediates LSF-induced Angiogenesis

To confirm the direct role of MMP-9 in regulating angiogenesis, we treated HUVECs with increasing concentration of recombinant active (83 kDa) MMP-9 (0.25 to 1 μg/ml) and subjected to differentiation assay. MMP-9 markedly augmented HUVEC tube formation in a dose-dependent manner and this effect of MMP-9 was completely abolished when MMP-9 was inactivated by boiling (Fig. 4, G and H).

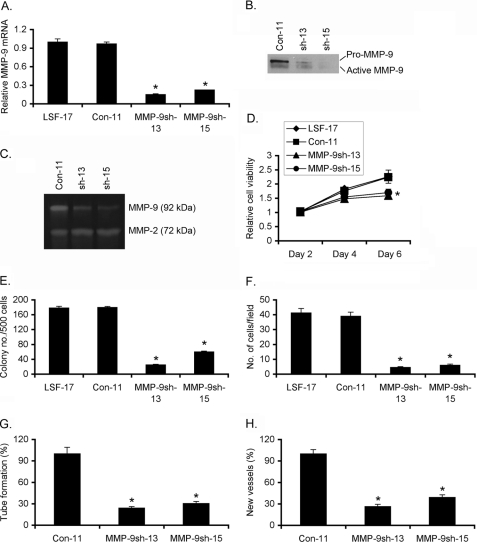

To interrogate the role MMP-9 in the oncogenic function of LSF, we generated by puromycin selection stable clones expressing MMP-9 shRNA in the background of LSF-17 clone of HepG3 cells. Two clones, MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 showed >80% reduction in MMP-9 mRNA expression compared with the parental LSF-17 cells as well as control puromycin-resistant clone (Con-11) (Fig. 5A). The decrease in mRNA level was confirmed at the protein level by Western blot analysis and by gelatin zymography using conditioned media (Fig. 5, B and C, respectively). Compared with LSF-17 cells and Con-11 clone, both MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 clones showed significant inhibition of cell growth and proliferation as revealed by MTT assay (Fig. 5D) and colony formation assay (Fig. 5E). Correlating with the function of MMP-9, MMP-9sh-13, and MMP-9sh-15 clones demonstrated profound inhibition of Matrigel invasion compared with LSF-17 cells and Con-11 clone (Fig. 5F). More importantly, CM from MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 clones poorly induced HUVEC tube formation (Fig. 5G) as well as neovascularization in CAM (Fig. 5H) when compared with CM from Con-11 clone. The CM from MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 clones contained significantly lower levels of angiogenic factors, such as IL-8 and VEGF, compared with the CM from Con-11 clone (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of MMP-9 abrogates augmentation of proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis by LSF. A, MMP-9sh-13 and MMP-9sh-15 clones with stable knockdown of MMP-9 were generated in LSF-17 clone of HepG3 cells. Con-11 is a control puromycin resistant-clone expressing scrambled shRNA. MMP-9 mRNA expression was determined by real-time PCR in the indicated cells. MMP-9 protein expression was detected by Western blot analysis (B) and gelatin zymography (C) using conditioned media from the indicated cells. Cell viability by standard MTT assay (D), colony formation assay (E), and Matrigel invasion assay (F) was performed using the indicated cells. Conditioned media from the indicated cells were subjected to HUVEC differentiation assay (G) and neovascularization assay in CAM (H). Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05.

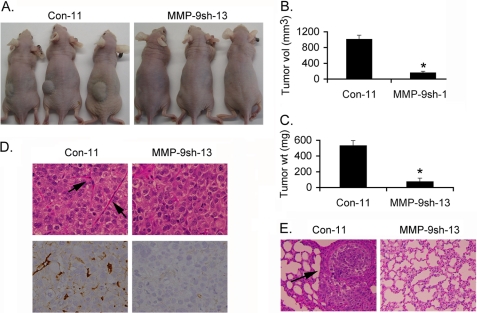

The in vitro observations were confirmed by in vivo assays. Con-11 and MMP-9sh-13 clones of LSF-17 cells were subcutaneously implanted in athymic nude mice. While Con-11 clone grew robustly, very small tumors were observed with the MMP-9sh-13 clone (Fig. 6, A–C). Tumors generated from Con-11 clone showed markedly increased angiogenesis when compared with MMP-9sh-13 clone when the sections were stained for the microvessel marker CD31 (Fig. 6D). The metastatic ability of these clones was analyzed by intravenous injection of the clones via tail vein. Analysis of lung sections indicated microscopic nodules throughout the lungs in the Con-11 clone injected animals, but no lung nodules were detected in animals receiving the MMP-9sh-13 clone (Fig. 6E).

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of MMP-9 abrogates LSF-induced tumorigenesis and metastasis. Control-11 and MMP-9sh-13 clones of LSF-17 cells were subcutaneously implanted into athymic nude mice. Animals were sacrificed after 3 weeks. A, representative photograph of tumor-bearing mice at the end of the study. Measurement of tumor volume (B) and tumor weight (C) at the end of the study. Data represent mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. D, tumor sections derived from Control-11 and MMP-9sh-13 clones were stained with H&E and for CD31. Arrows indicate blood vessels. E, indicated cells were intravenously injected into athymic nude mice and tumors were allowed to develop for 6 weeks. Sections of the lungs showing microscopic tumor nodules (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Angiogenesis is an invasive process that requires proteolysis of the extracellular matrix and proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (23). As such, MMPs play an important role in tumor angiogenesis by facilitating ECM degradation, mainly degradation of collagen in the basement membrane. MMP-9 also induces release of angiogenic factors from the ECM and/or promotes degradation of angiogenesis inhibitors that might reside in the ECM (24). The source of pro-angiogenic MMP-9 might be the tumor cells themselves. Studies from mouse models also suggest bone marrow-derived cells, neutrophils or osteoclasts as potential sources of MMP-9 facilitating tumor angiogenesis (25–28). We document that the angiogenic properties of conditioned media (CM) from MMP-9 knockdown HCC cells in an LSF-overexpression background were significantly compromised suggesting that MMP-9 plays a key role in the angiogenic function of LSF. MMP-9 contained in the CM from LSF-overexpressing cells might not only provide ECM degradation in CAM or HUVEC differentiation but also contribute to stimulation of endothelial cells by releasing angiogenic factors. The decrease in VEGF or IL-8 level in the CM of MMP-9 knockdown cells supports this hypothesis. We also observed that knocking down MMP-9 significantly impaired cell growth and proliferation, in addition to inhibition of invasion and angiogenesis, in LSF-overexpressing human HCC cells. Indeed, MMP-9 has been shown to be essential for survival of chronic leukocytic leukemia cells by inducing an anti-apoptotic signaling response and a similar mechanism might also be involved in HCC cells (29).

We previously identified OPN as a transcriptional target of LSF and demonstrated that OPN induction leading to c-Met activation plays a significant role in regulating the aggressive tumorigenic phenotype conferred by LSF (2). OPN promotes tumorigenesis via a vast array of mechanisms, one of which is induction of MMP-9 (30). Bioinformatics analysis identified six potential LSF-binding sites in the human MMP-9 promoter. The combination of deletion mutation and ChIP analyses revealed that only two of these sites are functionally relevant. Cross-talk with other transcription factors regulating MMP-9 expression might determine LSF binding to a specific site. The two most frequent transcription factors regulating MMP-9 transcription are NF-κB and AP-1. We have previously demonstrated that LSF itself can activate NF-κB and it also activates ERK signaling that might lead to AP-1 activation (2). These properties of LSF might be attributed to OPN, a known activator of NF-κB and AP-1, and OPN-induced c-Met activation. As such there might be multiple mechanisms by which LSF induces MMP-9 expression. On the other hand, MMP-9 is known to cleave OPN into specific fragments, which augment HCC cell invasion (31). Thus MMP-9 and OPN work in concert to promote hepatocarcinogenesis. The observation that LSF simultaneously regulates two important determinants of tumor progression, angiogenesis and metastasis, OPN and MMP-9, further strengthens its role in determining aggressive behavior of HCC.

Studies from mouse models provide interesting insights into the role of LSF/TFCP2 and LBP-1a/NF2d9, members of grainyhead family of transcription factors, in angiogenesis (32). An LSF knock-out mouse is viable and has a normal life expectancy suggesting that LBP1-a might compensate for LSF function. However, LBP-1a knock-out mice die at embryonic day 10.5 due to severe placental insufficiency because of an angiogenic defect in the mesodermal components of the labyrinthine layer and the yolk sac vasculature. These findings strongly suggest that this family of proteins is essential for angiogenesis. However, the underlying mechanism by which LBP-1a regulates angiogenesis is not clear. It is also not clear why LSF cannot compensate for LBP-1a deficiency, whereas LBP1-a can compensate for LSF, even though their tissue distribution is quite similar and they have a high degree of similarity in protein structure. Additionally, angiogenic factors, transcriptionally regulated by LBP-1a, have also not been identified. It might be possible that LSF has acquired more functional importance than LBP-1a in humans. Additionally, acquired tissue- and tumor-specific roles of LSF might also underlie its specialized function in regulating tumor angiogenesis. It should be noted that it is LSF, not LBP-1a, which is overexpressed in human HCC (2). The super-abundance of LSF in human HCC cells might allow it to transcriptionally regulate OPN or MMP-9, which may not happen under physiological conditions. Analysis of the role of LSF in regulating MMP-9 in inflammation- and/or wound-associated angiogenesis will provide important insight into the role of this unique transcription factor in biological processes.

In summary, our studies identify MMP-9, an important determinant of tumor progression, as a transcriptional target of LSF. It should be noted that ChIP-on-chip analysis did not identify other members of MMP family as LSF target genes establishing the central role of MMP-9 in mediating LSF-induced oncogenesis. An LSF inhibitor will inhibit OPN, c-Met, NF-κB, AP-1 and MMP-9, all intimately involved in hepatocarcinogenesis. Indeed, small molecule inhibitors of LSF significantly inhibit growth of human HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo4 thus ushering in a novel generation of anti-HCC agents with significant therapeutic potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Byoung Kwon Yoo for contribution to this manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by NCI, National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA138540 (to D. S.) and R01 CA134721 (to P. B. F.). This work study was also supported in part by grants from the Dana Foundation, the James S. McDonnell Foundation, and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation (SWCRF).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

D. Sarkar, submitted manuscript.

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- LSF

- late SV40 factor

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- OPN

- osteopontin

- HUVEC

- human vascular endothelial cell

- CAM

- chicken chorioallantoic membrane.

REFERENCES

- 1. El-Serag H. B., Rudolph K. L. (2007) Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 132, 2557–2576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoo B. K., Emdad L., Gredler R., Fuller C., Dumur C. I., Jones K. H., Jackson-Cook C., Su Z. Z., Chen D., Saxena U. H., Hansen U., Fisher P. B., Sarkar D. (2010) Transcription factor Late SV40 Factor (LSF) functions as an oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8357–8362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yoo B. K., Gredler R., Chen D., Santhekadur P. K., Fisher P. B., Sarkar D. (2011) c-Met activation through a novel pathway involving osteopontin mediates oncogenesis by the transcription factor LSF. J. Hepatol. 55, 1317–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoo B. K., Gredler R., Vozhilla N., Su Z. Z., Chen D., Forcier T., Shah K., Saxena U., Hansen U., Fisher P. B., Sarkar D. (2009) Identification of genes conferring resistance to 5-fluorouracil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12938–12943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deryugina E. I., Quigley J. P. (2006) Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25, 9–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levy A. T., Cioce V., Sobel M. E., Garbisa S., Grigioni W. F., Liotta L. A., Stetler-Stevenson W. G. (1991) Increased expression of the Mr 72,000 type IV collagenase in human colonic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 51, 439–444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Librach C. L., Werb Z., Fitzgerald M. L., Chiu K., Corwin N. M., Esteves R. A., Grobelny D., Galardy R., Damsky C. H., Fisher S. J. (1991) 92-kD type IV collagenase mediates invasion of human cytotrophoblasts. J. Cell Biol. 113, 437–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lengyel E., Gum R., Juarez J., Clayman G., Seiki M., Sato H., Boyd D. (1995) Induction of M(r) 92,000 type IV collagenase expression in a squamous cell carcinoma cell line by fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 55, 963–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe H., Nakanishi I., Yamashita K., Hayakawa T., Okada Y. (1993) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (92 kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase) from U937 monoblastoid cells: correlation with cellular invasion. J. Cell Sci. 104, 991–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arii S., Mise M., Harada T., Furutani M., Ishigami S., Niwano M., Mizumoto M., Fukumoto M., Imamura M. (1996) Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma with invasive potential. Hepatology 24, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hiratsuka S., Nakamura K., Iwai S., Murakami M., Itoh T., Kijima H., Shipley J. M., Senior R. M., Shibuya M. (2002) MMP9 induction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 is involved in lung-specific metastasis. Cancer Cell 2, 289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikkola J., Vihinen P., Vuoristo M. S., Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P., Kähäri V. M., Pyrhönen S. (2005) High serum levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and matrix metalloproteinase-1 are associated with rapid progression in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 5158–5166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakajima M., Welch D. R., Wynn D. M., Tsuruo T., Nicolson G. L. (1993) Serum and plasma M(r) 92,000 progelatinase levels correlate with spontaneous metastasis of rat 13762NF mammary adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 53, 5802–5807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hayasaka A., Suzuki N., Fujimoto N., Iwama S., Fukuyama E., Kanda Y., Saisho H. (1996) Elevated plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (92-kd type IV collagenase/gelatinase B) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 24, 1058–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergers G., Benjamin L. E. (2003) Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rundhaug J. E. (2005) Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 9, 267–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergers G., Brekken R., McMahon G., Vu T. H., Itoh T., Tamaki K., Tanzawa K., Thorpe P., Itohara S., Werb Z., Hanahan D. (2000) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chantrain C. F., Henriet P., Jodele S., Emonard H., Feron O., Courtoy P. J., DeClerck Y. A., Marbaix E. (2006) Mechanisms of pericyte recruitment in tumour angiogenesis: a new role for metalloproteinases. Eur. J. Cancer 42, 310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aalinkeel R., Nair M. P., Sufrin G., Mahajan S. D., Chadha K. C., Chawda R. P., Schwartz S. A. (2004) Gene expression of angiogenic factors correlates with metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 64, 5311–5321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfeifer A., Kessler T., Silletti S., Cheresh D. A., Verma I. M. (2000) Suppression of angiogenesis by lentiviral delivery of PEX, a noncatalytic fragment of matrix metalloproteinase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12227–12232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rocnik E. F., Liu P., Sato K., Walsh K., Vaziri C. (2006) The novel SPARC family member SMOC-2 potentiates angiogenic growth factor activity. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22855–22864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emdad L., Sarkar D., Lee S. G., Su Z. Z., Yoo B. K., Dash R., Yacoub A., Fuller C. E., Shah K., Dent P., Bruce J. N., Fisher P. B. (2010) Astrocyte elevated gene-1: a novel target for human glioma therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harper J., Moses M. A. (2006) Molecular regulation of tumor angiogenesis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. EXS. 96, 223–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stetler-Stevenson W. G. (1999) Matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis: a moving target for therapeutic intervention. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1237–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruni-Cardoso A., Johnson L. C., Vessella R. L., Peterson T. E., Lynch C. C. (2010) Osteoclast-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 directly affects angiogenesis in the prostate tumor-bone microenvironment. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 459–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bausch D., Pausch T., Krauss T., Hopt U. T., Fernandez-del-Castillo C., Warshaw A. L., Thayer S. P., Keck T. (2011) Neutrophil granulocyte derived MMP-9 is a VEGF independent functional component of the angiogenic switch in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Angiogenesis 14, 235–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuang D. M., Zhao Q., Wu Y., Peng C., Wang J., Xu Z., Yin X. Y., Zheng L. (2011) Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 54, 948–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahn G. O., Brown J. M. (2008) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for tumor vasculogenesis but not for angiogenesis: role of bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells. Cancer Cell 13, 193–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Redondo-Muñoz J., Ugarte-Berzal E., Terol M. J., Van den Steen P. E., Hernández del Cerro M., Roderfeld M., Roeb E., Opdenakker G., García-Marco J. A., García-Pardo A. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 promotes chronic lymphocytic leukemia b cell survival through its hemopexin domain. Cancer Cell 17, 160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen Y. J., Wei Y. Y., Chen H. T., Fong Y. C., Hsu C. J., Tsai C. H., Hsu H. C., Liu S. H., Tang C. H. (2009) Osteopontin increases migration and MMP-9 up-regulation via αvβ3 integrin, FAK, ERK, and NF-κB-dependent pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 221, 98–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takafuji V., Forgues M., Unsworth E., Goldsmith P., Wang X. W. (2007) An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 26, 6361–6371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parekh V., McEwen A., Barbour V., Takahashi Y., Rehg J. E., Jane S. M., Cunningham J. M. (2004) Defective extraembryonic angiogenesis in mice lacking LBP-1a, a member of the grainyhead family of transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7113–7129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.