Background: Lipin-1-deficient cells cannot differentiate into mature adipocytes.

Results: Lipin-1 phosphatidic acid phosphatase activity, but not its coactivator activity, is required for induction of the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ).

Conclusion: Lipin-1 modulation of phosphatidic acid levels is required for early steps in adipogenesis.

Significance: The levels of signaling lipids are important in adipogenesis prior to fat storage.

Keywords: Adipocyte, Cell Differentiation, Lipid Synthesis, Lipodystrophy, Phospholipid

Abstract

Adipose tissue plays a key role in metabolic homeostasis. Disruption of the Lpin1 gene encoding lipin-1 causes impaired adipose tissue development and function in rodents. Lipin-1 functions as a phosphatidate phosphatase (PAP) enzyme in the glycerol 3-phosphate pathway for triglyceride storage and as a transcriptional coactivator/corepressor for metabolic nuclear receptors. Previous studies established that lipin-1 is required at an early step in adipocyte differentiation for induction of the adipogenic gene transcription program, including the key regulator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). Here, we investigate the requirement of lipin-1 PAP versus coactivator function in the establishment of Pparg expression during adipocyte differentiation. We demonstrate that PAP activity supplied by lipin-1, lipin-2, or lipin-3, but not lipin-1 coactivator activity, can rescue Pparg gene expression and lipogenesis during adipogenesis in lipin-1-deficient preadipocytes. In adipose tissue from lipin-1-deficient mice, there is an accumulation of phosphatidate species containing a range of medium chain fatty acids and an activation of the MAPK/extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. Phosphatidate inhibits differentiation of cultured adipocytes, and this can be rescued by the expression of lipin-1 PAP activity or by inhibition of ERK signaling. These results emphasize the importance of lipid intermediates as choreographers of gene regulation during adipogenesis, and the results highlight a specific role for lipins as determinants of levels of a phosphatidic acid pool that influences Pparg expression.

Introduction

Adipose tissue plays a key role in metabolic homeostasis as evidenced by disorders of adipose tissue function, including obesity and lipodystrophy. The impaired development and lipid storage in adipose tissue (lipodystrophy), or excessive expansion and inflammation of adipose tissue (obesity), can both lead to increased risk for insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome (1–4). Adipocyte differentiation involves the induction of an ordered cascade of transcription factors and their target genes, which bring about the morphological and functional conversion of adipocyte precursors to mature lipid-filled adipocytes (reviewed in Refs. 5–7). A key player in the determination of preadipocyte differentiation to mature adipocytes is the nuclear receptor transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ).3 PPARγ (encoded by the gene Pparg) is sufficient to drive adipogenesis (8, 9), and the loss of Pparg expression impairs the ability of cells to differentiate into adipocytes (8, 9). PPARγ is also important in the function of mature adipocytes, regulating the expression of several adipocyte genes and secreted cytokines, including leptin and adiponectin (10).

Intensive study for the past 15 years has focused on mechanisms by which Pparg expression is regulated during adipocyte differentiation. Transcription factors belonging to the CAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) family, C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ, are induced very early during the differentiation of cultured preadipocytes and can induce the expression of Pparg and additional adipogenic transcription factors, including C/EBPα and the lipogenic transcription factor, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) (11, 12). However, these C/EBPs are expressed in tissues besides adipocytes, and loss of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ does not abolish Pparg expression in adipose tissue (13). Additionally, negative regulators of adipogenic gene transcription must be modulated to allow Pparg gene expression (14, 15). Thus, it is clear that several conditions must be met for the induction of Pparg gene expression and the progression of adipogenesis.

The hallmark feature of white adipose tissue is a primary function in lipid storage and release, and there is evidence that Pparg expression and PPARγ activity are regulated by the lipid milieu in developing and mature adipocytes. PPARγ activity can be modulated by endogenous lipid ligands, including activation by oxidized fatty acids, and inhibition of PPARγ activity by cyclic phosphatidic acid (10, 16, 17). In addition, recent evidence indicates that enzymes of the glycerol 3-phosphate pathway for triglyceride biosynthesis may have roles in PPARγ activation and/or adipogenic gene expression (18, 19). The activity of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases, acylglycerol acyltransferases, and the lipin phosphatidate phosphatases (PAP) sequentially convert glycerol 3-phosphate to lysophosphatidic acid (glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases), then to phosphatidic acid (acylglycerol acyltransferases), and to diacylglycerol (lipins) (reviewed in Refs. 20, 21). It has been shown that deficiency in GPAT3 (22), AGPAT2 (18), or lipin-1 (23, 24) each lead to impaired adipogenic gene expression at an early stage of adipocyte differentiation, prior to the requirement for triglyceride synthesis. This suggests a synchronization of adipogenic gene expression with the availability of glycerolipid precursors, but the mechanisms have not been elucidated.

Here, we investigate the role of lipin-1 in establishing Pparg expression levels in differentiating adipocytes. Lipin-1-deficient fld mice exhibit lipodystrophy characterized by dramatically reduced adipose tissue mass, absence of mature adipocytes, and metabolic dysregulation (reviewed in Ref. 25). In earlier studies, we determined that lipin-1 is required for induction of the adipogenic transcriptional program and that lipin-1 mRNA expression exhibits a biphasic pattern during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (24, 26). The first peak of lipin-1 expression occurs at 10 h after stimulation with adipogenic mixture, and it coincides with expression of Cebpb and Cebpd and precedes Pparg expression (24, 26). A second peak of lipin-1 expression begins 3 days after induction of differentiation (TAG) and coincides with the onset of triglyceride biosynthesis (24, 26). In addition to its role as a phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme, lipin-1 has been shown to act as a cofactor for metabolic transcription factors. Lipin-1 can coactivate PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) in liver (27), corepress the nuclear factor of activated T cells in mature adipocytes (28), and bind and activate PPARγ in adipocytes (29). Ren et al. (30) have demonstrated that PAP activity is required for both TAG biosynthesis and adipogenic gene expression, because wild-type, but not catalytically inactive, lipin-1b can restore these features to lipin-1-deficient embryonic fibroblasts. However, it is unknown whether the coactivator/corepressor function of lipin-1 has any role in modulating Pparg expression during adipocyte differentiation.

In this study, we assessed the requirement of lipin-1 PAP versus coactivator activities for the induction of Pparg expression during adipocyte differentiation. We demonstrate that PAP activity supplied by lipin-1 or its family members (lipin-2 and lipin-3), but not coactivator activity, can rescue Pparg gene expression and lipogenesis during adipogenesis in lipin-1-deficient preadipocytes. Lipin-1 PAP activity acts to prevent the accumulation of phosphatidic acid and activation of the MAPK/extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. These results emphasize the importance of lipid intermediates as choreographers of gene regulation during adipogenesis and highlight a specific role for lipins as determinants of levels of a phosphatidic acid pool that may be implicated in a variety of cellular processes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Adenovirus Constructs

To generate adenovirus vectors for the expression of lipins with the V5 epitope tag, full-length cDNAs for lipin-1a (GenBankTM accession number NM_172950), lipin-1b (NM_015763), lipin-2 (NM_00164885.1), and lipin-3 (NM_001199118.1) were PCR-amplified and subcloned into pShuttle-CMV (Stratagene/Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) by restriction digestion. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate the PAP-deficient forms of lipin-1aD679E and lipin-1bD712E, herein referred to as lipin-1a* and lipin-1b*. Recombinant adenoviruses were generated by transforming the resulting pShuttle-CMV-lipins and PAP-deficient pShuttle-CMV-lipins into AdEasier-1 cells, a derivative of BJ5183 bacteria already containing the adenovirus backbone plasmid pAdEasy-1 (Stratagene/Agilent Technologies). Positive recombinant adenoviruses were screened for resistance to kanamycin and restriction enzyme analysis using the PacI enzyme. Parvalbumin adenoviruses were amplified using HEK-293T cells and then purified as described previously (31).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Adenovirus Infection

Mice heterozygous for the Lpin1fld mutation were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and bred to generate wild-type Lpin1+/+ and lipin-1-deficient (Lpin1fld/fld, referred to simply as fld) mice used herein. Mice were housed with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle and fed standard mouse chow ad libitum. All mouse breeding and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and under the approval of the UCLA Institutional Animal Care Committee.

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were prepared from 14-day wild-type or fld mouse embryos (24). For adipocyte differentiation studies, cell were grown to confluence in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum and 1 day later were infected with replication-deficient adenovirus vectors containing cDNAs for expression of β-galactosidase (LacZ), wild-type lipin-1a, lipin-1b, lipin-2, lipin-3, or PAP-deficient lipin-1a* or lipin-1b* at a multiplicity of infection of 400. The following day, adipogenesis was induced, as described previously (24), by incubation for 2 days with differentiation mixture (0.5 mm methylisobutylxanthine, 1 μm dexamethasone, 5 μg/ml insulin) containing the thiazolidinedione rosiglitazone (1 μm). Differentiation was continued from day 2 to 6 by incubation in culture medium containing insulin and rosiglitazone.

Additional studies were performed with 3T3-F442A and 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell lines (provided by Dr. P. Tontonoz). For these studies, cells were grown to confluence in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum. 3T3-F442A cells were differentiated with the addition of 5 μg/ml insulin (3T3-F442A) (32) and 3T3-L1 cells with differentiation mixture containing insulin, methylisobutylxanthine, and dexamethasone (33). For some studies, cells were treated with 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidate (PA) or 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol (Avanti Lipids, Alabaster, AL). The PA was prepared by drying under nitrogen gas and then dissolving in phosphate-buffered saline with 5 min of bath sonication at a concentration of 5 mm (34). Some studies also used MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (Sigma) dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mm before adding to culture medium at a final concentration of 20 μm.

Transcriptional Coactivation Assay

The ability of lipin-1 to amplify PGC-1α coactivation was assessed as described previously (27, 35). Briefly, fld MEFs were transiently transfected with a PPRE-firefly luciferase reporter plasmid together with phRL-TK Renilla luciferase control vector (Promega, Madison, WI), pCMX-PPARγ, pCMX-PGC-1α, pCMX-RXR (kindly provided by Dr. Peter Tontonoz), and lipin-1a or lipin-1a* expression constructs. Two days after transfection, cells were collected, and luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI).

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells with TRIzol reagent and reverse-transcribed using Omniscript RT kit and oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). Real time qPCR was performed as described previously (36). Expression levels were normalized to the endogenous control TATA box-binding protein (TBP) and 18 S rRNA. Results were expressed as fold induction or repression by normalizing to the control condition. Primer sequences used for real time PCR are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for gene expression analysis

| Pparγ (forward) | 5′-CAAGAGCTGACCCAATGGTTGC-3′ |

| Pparγ (reverse) | 5′-CCCCACAGACTCGGCACTCAAT -3′ |

| Cebpa (forward) | 5′-GCAAAGCCAAGAAGTCGGTGGA-3′ |

| Cebpa (reverse) | 5′-TTCTGTTGCGTCTCCACGTTGC -3′ |

| Agpat2 (forward) | 5′-GCAACGACAATGGGGACCTG-3′ |

| Agpat2 (reverse) | 5′-ACAGCATCCAGCACTTGTACC-3′ |

| Dgat1 (forward) | 5′-TGCTACGACGAGTTCTTGAG-3′ |

| Dgat1 (reverse) | 5′-CTCTGCCACAGCATTGAGAC-3′ |

| Casp3 (forward) | 5′-GGATCAAAGCGCAGTGTCCTG-3′ |

| Casp3 (reverse) | 5′-GAGCGAGATGACATTCCAGTGCT-3′ |

| Casp9 (forward) | 5′-AGAGCTCTTCACGCGCGACAT-3′ |

| Casp9 (reverse) | 5′-GCCTTGGCCTGTGTCCTCTAA-3′ |

| CdKn1a (forward) | 5′-CCAACTACCAGCTGTGGGGTGA-3′ |

| CdKn1a (reverse) | 5′-AACGGCACACTTTGCTCCTGTG-3′ |

| Egr1 (forward) | 5′-AGCAGCGCCTTCAATCCTCAAG-3′ |

| Egr1 (reverse) | 5′-CCGAGTCGTTTGGCTGGGATAA-3′ |

| Myc (forward) | 5′-TTTCCTTTGGGCGTTGGAAACC-3′ |

| Myc (reverse) | 5′-AGCTCGCTCTGCTGTTGCTGGT-3′ |

| Tbp (forward) | 5′-ACCCTTCACCAATGACTCCTATG-3′ |

| Tbp (reverse) | 5′-ATGATGACTGCAGCAAATCGC-3′ |

| 18 S rRNA(forward) | 5′-ACCGCAGCTAGGAATAATGGA-3′ |

| 18 S rRNA (reverse) | 5′-GCCTCAGTTCCGAAAACCA-3′ |

Western Blot Analysis

For analysis of lipin protein levels, proteins were extracted from 6-day differentiated MEFs, electrophoresed on NuPAGE Novex Tris acetate 3–8% gradient gels (Invitrogen), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated with anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen), followed by rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Sigma), and developed with ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences). For analysis of ERK activation, blots were detected with antibodies against ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and quantified by densitometry using Quantity One-4.6.9 software (Bio-Rad).

Lipid Analyses

For quantification of cellular triglycerides, lipids were extracted from 100 μg of cell protein by a modification of the Bligh and Dyer method (37). Triglyceride concentration was determined using a colorimetric biochemical assay (L-type triglyceride M, Wako, Richmond, VA). Phosphatidate levels in 3T3-F442 cells were determined after cells were grown to confluence in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum and treated with specified PA concentrations for 10 min. Lipids were extracted, and PA was purified and quantitated with the total phosphatidic acid kit (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI) as described previously (38). For quantitation of phospholipid species in mouse tissues, lipids were extracted from inguinal adipose tissue from 5-month-old female fld and wild-type littermates and dried under a gentle stream of argon. An automated electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry approach was used, and data acquisition and analysis and acyl group identification were carried out as described previously (39) with modifications. The lipid samples were dissolved in 1 ml of chloroform. An aliquot of 15–50 μl of extract in chloroform was used. Precise amounts of internal standards, obtained and quantified as described previously (40), were added in the following quantities (with some small variation in amounts in different batches of internal standards): 0.6 nmol of di-12:0-PC; 0.6 nmol of di-24:1-PC; 0.6 nmol of 13:0-lyso-PC; 0.6 nmol of 19:0-lyso-PC; 0.3 nmol of di-14:0-PA; 0.3 nmol of di-20:0(phytanoyl)-PA; 0.196 nmol of di-18:1/14:0 Cr; 0.196 nmol of di-18:1/12:0 HexCer; and 0.196 nmol of d18:1/12:0 di-HexCer. The sample and internal standard mixture were combined with solvents, such that the ratio of chloroform, methanol, 300 mm ammonium acetate in water was 300:665:35, and the final volume was 1.4 ml. Unfractionated lipid extracts were introduced by continuous infusion into the electrospray ionization source on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (API 4000, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were introduced using an autosampler (LC Mini PAL, CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland) fitted with the required injection loop for the acquisition time and presented to the electrospray ionization needle at 30 μl/min. Finally, the data were corrected for the fraction of the sample analyzed and normalized to cellular protein.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance in studies shown in Figs. 1–3 and 5c was determined by one-way analysis of variance (Stata 11) with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Pairwise comparisons shown in Figs. 4 and 5, a and b, were performed by Student's t test.

FIGURE 1.

Wild-type, but not PAP-deficient, lipins complement adipocyte differentiation in primary MEFs from fld mice. a, schematic diagram of lipin proteins, with evolutionarily conserved domains (N-LIP and C-LIP), nuclear localization signal (NLS), PAP enzyme (DIDGT), and coactivator motifs (LGHIL) indicated. The DIDGT motif was mutated to EIDGT in lipin-1a* (1a*) and lipin-1b* (1b*) to produce proteins that are PAP-deficient but retain ability to coactivate transcription (27, 35). Representative Western blot shows the protein levels of various lipin isoforms expressed in fld MEFs using adenovirus vectors and detected with anti-V5 antibody. b, lipin-1a and lipin-1a* exhibit similar transcriptional coactivator activity in MEFs. Cotransfection of fld MEFs with a luciferase reporter containing three tandem PPAR-response elements (PPRE) and expression vectors for PGC-1α, PPARγ, retinoid X receptor α, and lipin-1a or lipin-1a* led to the relative luciferase expression levels shown (n = 4 for each condition). c, overview of experimental design. Primary MEFs isolated from wild-type or fld mice were cultured to confluence and infected with adenoviruses expressing wild-type or PAP-deficient lipin proteins or LacZ as a negative control. Cells were subsequently stimulated to differentiate into adipocytes by treating with methylisobutylxanthine (MIX), dexamethasone (DEX), insulin, and rosiglitazone (TZD) for 2 days. Terminal adipocyte differentiation was promoted by continued culture in insulin and rosiglitazone from day 2 to day 6. d, representative Oil Red O staining of mature adipocytes (day 6 of differentiation) derived from wild-type (wt) or fld MEFs infected with adenoviruses expressing LacZ, wild-type lipin-1a, or PAP-deficient lipin-1a*. e, quantitation of cellular triglyceride content in MEFs at day 6 of adipocyte differentiation. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations normalized to cellular protein. Statistically significant comparisons are identified with brackets; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

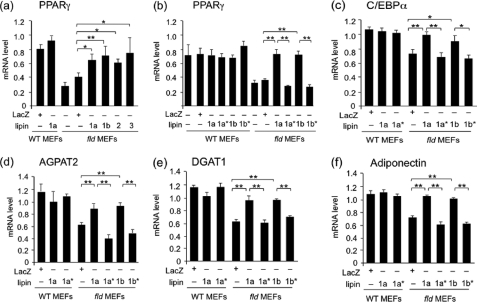

FIGURE 2.

Wild-type lipins, but not PAP-deficient coactivator-proficient lipins, complement the adipogenic gene transcription defect in primary MEFs from fld mice. qPCR was performed to determine PPARγ (a and b), C/EBPα (c), AGPAT2 (d), DGAT1 (e), and adiponectin (f) transcripts in wild-type or fld MEFs at post-differentiation day 6. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate determinations normalized to 18 S RNA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 for comparisons indicated.

FIGURE 3.

Lipin-1 overcomes PA inhibition of PPARγ and C/EBPα gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. a, 3T3-F442A preadipocytes were treated with PA at the indicated concentrations and intracellular PAP levels measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” b–d, 3T3-F442A preadipocytes were treated with insulin in the presence or absence of PA at the concentrations indicated for 2 days. qPCR was performed to determine expression levels of PPARγ (b), C/EBPα (c), and the apoptosis marker caspase-3 (d). Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate determinations normalized to TBP. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, versus no insulin treatment; #, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.01, versus insulin alone treatment. e, treatment of 3T3-F442A preadipocytes with dioleoylglycerol (DG) at the indicated concentrations did not influence Pparg expression levels. *, p < 0.05 compared with cells without insulin treatment. f and g, PA inhibition of adipogenic gene expression is reversed by expression of lipin-1a but not lipin-1a*. MEFs from wild-type mice were infected with adenovirus expressing lipin-1a, lipin-1a*, or LacZ and then stimulated to differentiate in the presence or absence of PA for 2 days. qPCR was performed to determine mRNA levels. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate determinations normalized to TBP. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 for comparisons indicated.

FIGURE 5.

Activation of ERK1/2 contributes to PA inhibition of adipocyte differentiation. a, adipose tissues from wild-type (WT) and fld mice were analyzed for the activation of ERK1/2 by Western blotting with specific antibodies recognizing ERK1/2 or the phosphorylated form (P-Erk1/2), and bands were quantitated by densitometry (n = 3). b, qPCR evaluation of the ERK1/2 effectors EGR-1 (also known as Krox-24) and c-Myc, and the ceramide-regulated genes caspase-9 and p21. c, inhibition of ERK1/2 rescues the PA inhibitory effect on PPARγ induction during 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation. Two-day postconfluent 3T3-L1 cells were stimulated with differentiation mixture in the presence or absence PA for 2 days. PPARγ mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to TBP. Data are means ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 versus WT (in a and b) or for comparisons indicated (in c). DMI, dexamethasone, methylisobutylxanthine, insulin adipogenic mixture; PD, PD98059 MEK inhibitor.

FIGURE 4.

Accumulation of phospholipid species in adipose tissue of fld mice. Electron spray ionization-mass spectrometric analysis of phospholipid species in inguinal adipose tissue of wild-type (WT) and fld mice revealed altered levels of PA (a), ceramides (b), sphingomyelin (SM), ceramide, hexosylceramide (HexCer), dihexosylceramide (DiHexCer), PC, lysophosphatidylcholine (LysoPC), and ether-linked phosphatidylcholine (ePC) (c). Right panels in a and b show molecular species of PA and ceramides indicated by total number of carbons and number of double bonds. (n = 6); *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus WT.

RESULTS

PAP Enzyme Activity Is Required for Induction of Pparg Expression during Adipogenesis

Lipin-1 is required for both TAG synthesis and the expression of Pparg and other adipogenic genes during adipogenesis in vitro (23, 24) and in vivo (23, 41). Both the enzymatic and transcriptional activities of lipin-1 may contribute to full adipogenic differentiation (30). To investigate the relative contribution of PAP and coactivator activities in the attainment of a normal adipogenic transcription program, we complemented lipin-1-deficient adipocyte precursors with either wild-type lipin-1, lipin-2, or lipin-3, or with mutant lipin-1 that retains coactivator function but lacks PAP enzyme activity (27, 35). The coactivator-proficient, PAP-deficient lipin-1 proteins were generated by mutation of the PAP catalytic motif and are referred to herein as lipin-1a* and lipin-1b* (Fig. 1a). We confirmed that the PAP-deficient lipin-1a* protein retains coactivator activity in conjunction with PGC-1α in preadipocytes derived from lipin-1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 1b, wild-type lipin-1a and mutant lipin-1a* both amplified the PGC-1α activation of PPAR response element to a similar degree as previously observed in hepatocytes (27, 35).

To assess the requirement for lipin PAP and/or coactivator functions in adipocyte differentiation, embryonic fibroblasts from fld and wild-type mice were grown to confluence, treated with adenovirus expressing the indicated forms of lipin proteins, and differentiated to adipocytes as outlined in the time line shown in Fig. 1c. The adenovirus constructs expressed similar levels of each of the wild-type and mutant lipin proteins, as demonstrated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1a, lower portion). At day 6 of differentiation, TAG accumulation and gene expression analyses were performed. As we have reported previously, wild-type MEFs exhibited robust accumulation of Oil Red O-stained neutral lipids, whereas fld MEFs exhibited dramatically attenuated lipid droplet accumulation (Fig. 1d). Expression of adenoviral lipin-1a in wild-type MEFs did not influence TAG levels compared with expression of the control adenoviral LacZ (Fig. 1e), indicating that endogenous lipin-1 present in these cells is sufficient for TAG accumulation. Complementation of fld MEFs with adenovirus expressing wild-type lipin-1a or lipin-1b substantially increased TAG levels above levels in MEFs transfected with the LacZ control (Fig. 1, d and e). Lipin-2 and lipin-3 each complemented TAG accumulation to a similar degree as lipin-1 (Fig. 1e), indicating that any of the lipin protein family members could supply PAP activity required for TAG accumulation during adipogenesis if they were expressed at sufficient levels in adipocytes. As would be predicted, lipin-1a* and lipin-1b* proteins lacking PAP activity could not increase TAG levels above those observed in uninfected fld MEFs (Fig. 1e).

We next assessed the capacity of wild-type and PAP-deficient lipin proteins to rescue the expression of Pparg and downstream adipocyte genes during adipogenesis. Cells cultured in parallel to those shown in Fig. 1 were assessed for gene expression levels by qPCR. Six days after induction of adipocyte differentiation, wild-type MEFs expressed high levels of Pparg mRNA, which were not augmented by expression of adenoviral lipin-1a (Fig. 2a). Lipin-1-deficient MEFs exhibited 60% lower Pparg expression levels than wild-type MEFs, but these levels were restored by the expression of lipin-1a, -1b, -2, or -3 (Fig. 2a). By contrast, expression of lipin-1a* or -1b* in fld MEFs did not restore Pparg expression (Fig. 2b), indicating that lipin PAP activity is critical for the induction of Pparg in differentiating adipocytes. Wild-type, but not PAP-deficient lipin-1, was also able to restore mRNA expression of the adipogenic transcription factor C/EBPα, triglyceride biosynthetic genes Agpat and diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 (Dgat1), and the adipokine adiponectin (Fig. 2, c--f). Thus, lipin PAP activity is required not only for triglyceride synthesis but also for induction of Pparg and downstream adipocyte genes during adipogenesis. By contrast, the lipin-1 coactivator function of lipin-1a* and lipin-1b* did not alleviate impaired gene expression or TAG accumulation in lipin-1-deficient adipocytes.

Lipin-1 PAP Activity Relieves the Inhibition of Pparg Induction by Phosphatidic Acid

The requirement of lipin PAP activity for Pparg gene expression during adipogenesis suggested that specific lipid species within the cell may have a regulatory effect on this process. Lipin PAP enzymes convert phosphatidate (PA) to diacylglycerol, and lipin-1-deficient mouse tissues accumulate PA (42). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that PA accumulation in Schwann cells and other cell types is associated with cell dedifferentiation and proliferation (42–44). We hypothesized that PA accumulation in lipin-1-deficient preadipocytes may inhibit their differentiation. To assess this possibility, we investigated the effect of PA on differentiation of the 3T3-F442A preadipocyte cell line.

We first demonstrated that treatment of 3T3-F442A preadipocytes with exogenous di-oleoyl-PA leads to a concentration-dependent increase in intracellular PA levels (as distinguished from lyso-PA or other species) (Fig. 3a). We next demonstrated that treatment with increasing concentrations of PA leads to reductions in adipogenic gene expression. Insulin treatment of 3T3-F442A cells to induce differentiation led to a 4-fold increase in Pparg expression (Fig. 3b). This induction of Pparg was attenuated in a dose-responsive manner in the presence of dioleoyl-PA, with concentrations of 5–50 μm producing a 40–60% inhibition (Fig. 3b). PA concentrations of 50 μm and above also substantially negated the induction of Cebpa expression during adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 3c). This was not related to an induction of genes associated with cell apoptosis, such as caspase 3 (Fig. 3d). In contrast to the effect of PA, treatment with diacylglycerol (the product of the PAP reaction) did not alter Pparg expression levels compared with insulin treatment alone (Fig. 3e).

The inhibition of Pparg and Cebpa gene expression by PA was reversed by overexpression of wild-type, but not PAP-deficient, lipin-1. Thus, 50 μm PA substantially inhibited Pparg and Cebpa gene expression in differentiating wild-type MEF cells (Fig. 3, f and g). This inhibition was abolished by expression of lipin-1a but not lipin-1a*. Taken together, our results are consistent with a role for lipin-1 in modulating the levels of the lipid signaling molecule PA during early stages of adipogenesis to allow expression of adipogenic transcription factors, in addition to its role in TAG synthesis at later stages of adipogenesis.

Accumulation of Phosphatidate, Ceramides, and Phosphatidylcholine Species in Lipin-1-deficient Adipose Tissue

To determine which species of PA, and potentially other lipid intermediates, contribute to impaired adipocyte differentiation in vivo, we quantitated phospholipid species in inguinal adipose tissue from wild-type and fld mice by tandem mass spectrometry. As expected, white adipose tissue isolated from fld mice had a 4.6-fold elevation of total PA levels compared with wild-type adipose tissue (Fig. 4a). Although the individual identities of the two fatty acid moieties present on PA were not revealed by the mass spectrometry, fld adipose tissue showed significant increases in the levels of most PA species having medium chain fatty acids (i.e. 32:1 to 38:4), whereas PA species with longer chain fatty acid species (i.e. 40:5–40:7) were similar in wild-type and fld adipose tissue (Fig. 4a).

In addition to PA, other specific phospholipid species also showed an accumulation in fld adipose tissue. Total ceramide levels were elevated 6.1-fold, which included several fatty acid species (Fig. 4b). Levels of glucose-modified ceramides (HexCer and diHexCer) were not altered in fld adipose tissue (Fig. 4c). However, sphingomyelin and some forms of phosphatidylcholine (lyso-PC and ether-linked PC) were increased in fld adipose tissue by 60–90% (Fig. 4c). Thus, in addition to the previously determined reduction in TAG content, phospholipid content of adipose tissue from lipin-1-deficient mice is substantially altered.

PA Activation of ERK1/2 Contributes to the Inhibitory Effect of Lipin-1 Deficiency on Pparg Induction

The altered phospholipid levels in fld adipose tissue described above suggest that accumulation of lipid intermediates may contribute to the impaired function of fld adipose tissue. Both PA and ceramides are known activators of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway (45–47), and ERK1/2 inhibits 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation (48). We therefore hypothesized that lipin-1 deficiency impacts adipocyte differentiation, in part, through the effects downstream of ERK1/2 activation. ERK1/2 phosphorylation on Thr-202/Thr-204 residues was significantly increased in adipose tissue of fld compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 5a). Importantly, evidence for enhanced ERK1/2 activity was apparent in fld adipose tissue in the form of 3–4-fold increases in the expression levels of ERK1/2 effector genes early growth response 1 (Egr1) and myelocytomatosis oncogene (Myc) (Fig. 5b). In contrast, genes that are known to respond to increased ceramide levels, including the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and the apoptotic gene caspase 9 (49), did not show dysregulated expression in fld adipose tissue. We therefore focused our attention on the potential effects of PA as a key lipid intermediate that may exert effects on adipogenesis in lipin-1-deficient preadipocytes.

To determine whether activated ERK1/2 plays a role in the PA-induced inhibition of Pparg expression during adipocyte differentiation, we assessed the ability of a MEK inhibitor to reverse the effects of PA on Pparg gene expression. 3T3-L1 cells were induced to differentiate into adipocytes by incubation with the adipogenic mixture, and Pparg mRNA levels were determined 2 days later. The adipogenic mixture increased Pparg expression 2-fold, but this effect was negated by treatment with PA (Fig. 5c). In contrast, when the experiment was performed in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD98058, the inhibitory effect of PA on Pparg expression was prevented. These results suggest that activation of ERK1/2 contributes to the inhibition of adipocyte differentiation by PA and suggests that one role of lipin-1 in adipogenesis is to modulate PA levels to allow the expression of the key adipogenic gene Pparg.

DISCUSSION

A role for lipin-1 in adipocyte development was first suspected upon identification of a null mutation in the Lpin1 gene as the genetic lesion in the lipodystrophic fld mouse (50). Subsequent studies demonstrated that lipin-1 is highly expressed in adipose tissue in vivo, and its expression is induced at both early and late stages of differentiation of the 3T3-L1 adipocyte cell line (24, 50). The elucidation of lipin-1 as a PAP enzyme required for TAG biosynthesis (51) and the demonstration that lipin-1 is required for PAP activity in adipose tissue (52, 53) provided an explanation for the inability of lipin-1-deficient mice to accumulate TAG in their adipose tissue. More recent studies have also demonstrated that deficiency of lipin orthologs in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster both lead to reduced TAG content (54, 55). However, it was unclear how a lack of lipin-1 also results in impaired induction of the central regulator of mammalian adipogenesis, PPARγ, which occurs prior to TAG synthesis. An attractive possibility was that lipin-1 might contribute to the induction of Pparg expression through its transcriptional coactivator function, based on its demonstrated activity as a transcriptional coactivator for PGC-1α in liver (27). However, recent work also implicated lipin-1 PAP activity in the establishment of adipogenic gene expression (30). To clarify the mechanism(s) by which lipin-1 promotes adipogenic gene expression and adipocyte differentiation, we used wild-type and PAP-deficient, coactivator-proficient lipin proteins to establish that the PAP activity of lipin-1 is required to modulate PA levels and allow attainment of normal Pparg gene expression levels in differentiating adipocytes.

Consistent with previous studies from our laboratory (23, 24) and others (30), lipin-1-deficient MEFs exhibited impaired adipocyte differentiation characterized by blunted expression levels of Pparg, Cebpa, and genes encoding enzymes of the glycerol phosphate TAG biosynthetic pathway. Lipin-1-deficient adipocytes also fail to express the adiponectin gene, a specific target of PPARγ that is not regulated by other members of the PPAR family (PPARα and PPARδ) (56). Complementation of lipin-1 deficiency by expression of wild-type lipin-1, lipin-2, or lipin-3 could restore the normal adipogenic program and TAG accumulation. However, lipin-1 containing a point mutation that alters the PA-active site motif was incapable of complementing the defect in adipogenic gene expression, despite the fact that this mutant retains coactivator activity in the cells employed in these studies. We further demonstrated that lipin-2 and lipin-3 complemented the defect in adipogenesis to a similar degree as lipin-1 despite the previous observation that various lipin proteins appear to have different PAP enzyme specific activities in an in vitro assay (lipin-1 > lipin-2 > lipin-3) (52). This may be related to differences in PAP activity of these proteins in vitro compared with their activity within a cell or to the relatively high expression levels of lipins achieved via introduction of recombinant adenovirus.

Our results are consistent with the characteristics of a rat model carrying a spontaneous mutation that produces a truncated lipin-1 protein lacking the proposed magnesium-binding site, which ablates PAP activity (57). The mutant rats exhibited reduced white adipose tissue weight, reduced adipocyte diameter, and reduced Pparg gene expression beginning at post-natal day 21. This mutation does not alter the coactivator motif, raising the possibility that the mutant lipin-1 protein in these rats may represent a coactivator-proficient, PAP-deficient lipin-1 protein. However, the authors were unable to demonstrate whether the protein possesses any coactivator activity (57), leading to an inability to attribute adipose tissue defects strictly to a lack of PAP enzyme activity. In this study, using lipin-1 proteins with known coactivator activity but lacking PAP enzyme activity, we could definitively tease apart the requirement of lipin-1 PAP activity versus intact coactivator function.

TAG biosynthesis in the adipocyte occurs primarily through the action of enzymes of the glycerol 3-phosphate pathway, including glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases, acylglycerol acyltransferases, lipins, and diacylglycerol acyltransferases (20, 21). In addition to their roles as building blocks for TAG biosynthesis, the intermediates in the glycerol phosphate pathway are bioactive lipids. A recent study on the rate-limiting enzyme of the pathway, GPAT1, demonstrated that the product of this enzyme (lysophosphatidic acid) increases PPARγ activity in Chinese hamster ovary cells, as assessed by a luciferase reporter assay (19). In contrast, overexpression of AGPAT2, the subsequent enzyme in the glycerolipid pathway, which utilizes lysophosphatidic acid as a substrate and converts it to PA, attenuated PPARγ activity. An additional manipulation to increase PA levels, expression of diacylglycerol kinase α, also attenuated PPARγ activity. The results of Stapleton et al. (19), together with results presented here, indicate the following: 1) lipid intermediates synthesized by the pathway for de novo glycerolipid synthesis have important roles in the regulation of adipogenesis, and 2) PA has an inhibitory effect on both the expression and the activity of PPARγ during adipogenesis.

Recent studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have demonstrated a critical role for the yeast lipin ortholog, Pah1, in preventing the accumulation of phospholipids and fatty acids that may be toxic to the cells, particularly during the stationary growth phase (58). Thus, in organisms ranging from single-celled eukaryotes to several mammalian tissues (e.g. Schwann cells, adipose tissue, and heart (42, 59)), phosphatidate phosphatase activity is critical for maintenance of intracellular lipid homeostasis. This suggests that the phenotype of diseases caused by mutations in members of the glycerolipid biosynthetic pathway may reflect both a lack of specific enzymatic products and the consequences of an accumulation of lipid intermediates within the cell. It will be interesting to determine, for example, whether the lipodystrophy caused by the null mutations in the gene encoding AGPAT2 in humans (60) and mice (61) is also associated with a dysregulation of signaling lipid species within adipocytes.

Finally, the results shown here raise the possibility that the modulation of PA levels by lipin-1 in tissues such as adipose tissue may impact processes beyond the synthesis of glycerolipids. Cellular PA pools exist within internal membranes of the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria, as well as the plasma membrane (reviewed in Refs. 62, 63). Although the concentration of PA in the plasma membrane and some internal membranes is largely determined by the rate of generation by phospholipase D, it is possible that lipin proteins influence the PA concentrations in the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and the nuclear membranes by catalyzing its turnover to diacylglycerol (43, 64). Although the understanding of PA pools and their cellular functions is at an early stage, numerous proteins with PA binding properties have been identified in many cellular compartments (63). A PA-binding site on lipin-1 has also been identified (30), and it has been demonstrated that lipin-1 binds to PA present on mitochondrial membranes to promote mitochondrial fission and influence mitochondrial size (64). These results and the current studies of adipocyte differentiation open the door for the further exploration of the role of lipin-1 in the regulation of PA levels.

Acknowledgments

The lipidomic analyses by mass spectrometry were performed at the Kansas Lipidomics Research Center Analytical Laboratory. Instrument acquisition and methods development at the Kansas Lipidomics Research Center were supported by National Science Foundation Grants EPS 0236913, MCB 0455318 and 0920663, and DBI 0521587, the Kansas Technology Enterprise Corp., National Institutes of Health Grant P20RR16475, K-IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence, and Kansas State University.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HL90553 and P01 HL28481 (to K. R.) and T32 HG002536 (to L. C.).

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PAP

- phosphatidate phosphatase

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PA

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidate

- TBP

- TATA box-binding protein

- C/EBP

- CAAT/enhancer-binding protein

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PA

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidate

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- TAG

- triacylglycerol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang-Doran I., Sleigh A., Rochford J. J., O'Rahilly S., Savage D. B. (2010) Lipodystrophy. Metabolic insights from a rare disorder. J. Endocrinol. 207, 245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lusis A. J., Attie A. D., Reue K. (2008) Metabolic syndrome. From epidemiology to systems biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 819–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reue K., Phan J. (2006) Metabolic consequences of lipodystrophy in mouse models. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 9, 436–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zalesin K. C., Franklin B. A., Miller W. M., Peterson E. D., McCullough P. A. (2011) Impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease. Med. Clin. North Am. 95, 919–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowe C. E., O'Rahilly S., Rochford J. J. (2011) Adipogenesis at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2681–2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vernochet C., Peres S. B., Farmer S. R. (2009) Mechanisms of obesity and related pathologies. Transcriptional control of adipose tissue development. FEBS J. 276, 5729–5737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White U. A., Stephens J. M. (2010) Transcriptional factors that promote formation of white adipose tissue. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 318, 10–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barak Y., Nelson M. C., Ong E. S., Jones Y. Z., Ruiz-Lozano P., Chien K. R., Koder A., Evans R. M. (1999) PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol. Cell 4, 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tontonoz P., Hu E., Spiegelman B. M. (1994) Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARγ2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 79, 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tontonoz P., Spiegelman B. M. (2008) Fat and beyond. The diverse biology of PPARγ. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 289–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Payne V. A., Au W. S., Lowe C. E., Rahman S. M., Friedman J. E., O'Rahilly S., Rochford J. J. (2010) C/EBP transcription factors regulate SREBP1c gene expression during adipogenesis. Biochem. J. 425, 215–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu Z., Bucher N. L., Farmer S. R. (1996) Induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ during the conversion of 3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes is mediated by C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and glucocorticoids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4128–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanaka T., Yoshida N., Kishimoto T., Akira S. (1997) Defective adipocyte differentiation in mice lacking the C/EBPβ and/or C/EBPδ gene. EMBO J. 16, 7432–7443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross S. E., Erickson R. L., Gerin I., DeRose P. M., Bajnok L., Longo K. A., Misek D. E., Kuick R., Hanash S. M., Atkins K. B., Andresen S. M., Nebb H. I., Madsen L., Kristiansen K., MacDougald O. A. (2002) Microarray analyses during adipogenesis. Understanding the effects of Wnt signaling on adipogenesis and the roles of liver X receptor α in adipocyte metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5989–5999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Villanueva C. J., Waki H., Godio C., Nielsen R., Chou W. L., Vargas L., Wroblewski K., Schmedt C., Chao L. C., Boyadjian R., Mandrup S., Hevener A., Saez E., Tontonoz P. (2011) TLE3 is a dual-function transcriptional coregulator of adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 13, 413–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Itoh T., Fairall L., Amin K., Inaba Y., Szanto A., Balint B. L., Nagy L., Yamamoto K., Schwabe J. W. (2008) Structural basis for the activation of PPARγ by oxidized fatty acids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 924–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsukahara T., Tsukahara R., Fujiwara Y., Yue J., Cheng Y., Guo H., Bolen A., Zhang C., Balazs L., Re F., Du G., Frohman M. A., Baker D. L., Parrill A. L., Uchiyama A., Kobayashi T., Murakami-Murofushi K., Tigyi G. (2010) Phospholipase D2-dependent inhibition of the nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ by cyclic phosphatidic acid. Mol. Cell 39, 421–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gale S. E., Frolov A., Han X., Bickel P. E., Cao L., Bowcock A., Schaffer J. E., Ory D. S. (2006) A regulatory role for 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate-O-acyltransferase 2 in adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11082–11089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stapleton C. M., Mashek D. G., Wang S., Nagle C. A., Cline G. W., Thuillier P., Leesnitzer L. M., Li L. O., Stimmel J. B., Shulman G. I., Coleman R. A. (2011) Lysophosphatidic acid activates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ in CHO cells that overexpress glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase-1. PloS ONE 6, e18932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bell R. M., Coleman R. A. (1980) Enzymes of glycerolipid synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49, 459–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takeuchi K., Reue K. (2009) Biochemistry, physiology, and genetics of GPAT, AGPAT, and lipin enzymes in triglyceride synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E1195–E1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shan D., Li J. L., Wu L., Li D., Hurov J., Tobin J. F., Gimeno R. E., Cao J. (2010) GPAT3 and GPAT4 are regulated by insulin-stimulated phosphorylation and play distinct roles in adipogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1971–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Péterfy M., Phan J., Reue K. (2005) Alternatively spliced lipin isoforms exhibit distinct expression pattern, subcellular localization, and role in adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32883–32889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Phan J., Péterfy M., Reue K. (2004) Lipin expression preceding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ is critical for adipogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29558–29564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Csaki L. S., Reue K. (2010) Lipins. Multifunctional lipid metabolism proteins. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 257–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phan J., Peterfy M., Reue K. (2005) Biphasic expression of lipin suggests dual roles in adipocyte development. Drug News Perspect. 18, 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Finck B. N., Bernal-Mizrachi C., Han D. H., Coleman T., Sambandam N., LaRiviere L. L., Holloszy J. O., Semenkovich C. F., Kelly D. P. (2005) A potential link between muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α signaling and obesity-related diabetes. Cell Metab. 1, 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim H. B., Kumar A., Wang L., Liu G. H., Keller S. R., Lawrence J. C., Jr., Finck B. N., Harris T. E. (2010) Lipin 1 represses NFATc4 transcriptional activity in adipocytes to inhibit secretion of inflammatory factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3126–3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koh Y. K., Lee M. Y., Kim J. W., Kim M., Moon J. S., Lee Y. J., Ahn Y. H., Kim K. S. (2008) Lipin1 is a key factor for the maturation and maintenance of adipocytes in the regulatory network with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 34896–34906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren H., Federico L., Huang H., Sunkara M., Drennan T., Frohman M. A., Smyth S. S., Morris A. J. (2010) A phosphatidic acid-binding/nuclear localization motif determines lipin1 function in lipid metabolism and adipogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3171–3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He T. C., Zhou S., da Costa L. T., Yu J., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1998) A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2509–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franckhauser S., Antras-Ferry J., Robin P., Robin D., Granner D. K., Forest C. (1995) Expression of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene in 3T3-F442A adipose cells. Opposite effects of dexamethasone and isoprenaline on transcription. Biochem. J. 305, 65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Student A. K., Hsu R. Y., Lane M. D. (1980) Induction of fatty-acid synthetase synthesis in differentiating 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 4745–4750 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kraft C. A., Garrido J. L., Fluharty E., Leiva-Vega L., Romero G. (2008) Role of phosphatidic acid in the coupling of the ERK cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36636–36645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donkor J., Zhang P., Wong S., O'Loughlin L., Dewald J., Kok B. P., Brindley D. N., Reue K. (2009) A conserved serine residue is required for the phosphatidate phosphatase activity but not the transcriptional coactivator functions of lipin-1 and lipin-2. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29968–29978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang P., O'Loughlin L., Brindley D. N., Reue K. (2008) Regulation of lipin-1 gene expression by glucocorticoids during adipogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1519–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morita S. Y., Ueda K., Kitagawa S. (2009) Enzymatic measurement of phosphatidic acid in cultured cells. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1945–1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Devaiah S. P., Roth M. R., Baughman E., Li M., Tamura P., Jeannotte R., Welti R., Wang X. (2006) Quantitative profiling of polar glycerolipid species from organs of wild-type Arabidopsis and a phospholipase Dα1 knockout mutant. Phytochemistry 67, 1907–1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Welti R., Li W., Li M., Sang Y., Biesiada H., Zhou H. E., Rajashekar C. B., Williams T. D., Wang X. (2002) Profiling membrane lipids in plant stress responses. Role of phospholipase Dα in freezing-induced lipid changes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31994–32002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Phan J., Reue K. (2005) Lipin, a lipodystrophy and obesity gene. Cell Metab. 1, 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nadra K., de Preux Charles A. S., Médard J. J., Hendriks W. T., Han G. S., Grès S., Carman G. M., Saulnier-Blache J. S., Verheijen M. H., Chrast R. (2008) Phosphatidic acid mediates demyelination in Lpin1 mutant mice. Genes Dev. 22, 1647–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brindley D. N., Pilquil C., Sariahmetoglu M., Reue K. (2009) Phosphatidate degradation. Phosphatidate phosphatases (lipins) and lipid phosphate phosphatases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 956–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Foster D. A. (2007) Regulation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid? Cancer Res. 67, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andresen B. T., Rizzo M. A., Shome K., Romero G. (2002) The role of phosphatidic acid in the regulation of the Ras/MEK/Erk signaling cascade. FEBS Lett. 531, 65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gangoiti P., Granado M. H., Wang S. W., Kong J. Y., Steinbrecher U. P., Gómez-Muñoz A. (2008) Ceramide 1-phosphate stimulates macrophage proliferation through activation of the PI3-kinase/PKB, JNK, and ERK1/2 pathways. Cell. Signal. 20, 726–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Subbaramaiah K., Chung W. J., Dannenberg A. J. (1998) Ceramide regulates the transcription of cyclooxygenase-2. Evidence for involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32943–32949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim K. A., Kim J. H., Wang Y., Sul H. S. (2007) Pref-1 (preadipocyte factor 1) activates the MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway to inhibit adipocyte differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 2294–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Patwardhan G. A., Liu Y. Y. (2011) Sphingolipids and expression regulation of genes in cancer. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 104–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Péterfy M., Phan J., Xu P., Reue K. (2001) Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat. Genet. 27, 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han G. S., Wu W. I., Carman G. M. (2006) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lipin homolog is a Mg2+-dependent phosphatidate phosphatase enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9210–9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Donkor J., Sariahmetoglu M., Dewald J., Brindley D. N., Reue K. (2007) Three mammalian lipins act as phosphatidate phosphatases with distinct tissue expression patterns. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3450–3457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harris T. E., Huffman T. A., Chi A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Kumar A., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (2007) Insulin controls subcellular localization and multisite phosphorylation of the phosphatidic acid phosphatase, lipin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Golden A., Liu J., Cohen-Fix O. (2009) Inactivation of the C. elegans lipin homolog leads to ER disorganization and to defects in the breakdown and reassembly of the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1970–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ugrankar R., Liu Y., Provaznik J., Schmitt S., Lehmann M. (2011) Lipin is a central regulator of adipose tissue development and function in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1646–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hummasti S., Tontonoz P. (2006) The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor N-terminal domain controls isotype-selective gene expression and adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1261–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mul J. D., Nadra K., Jagalur N. B., Nijman I. J., Toonen P. W., Médard J. J., Grès S., de Bruin A., Han G. S., Brouwers J. F., Carman G. M., Saulnier-Blache J. S., Meijer D., Chrast R., Cuppen E. (2011) A hypomorphic mutation in Lpin1 induces progressively improving neuropathy and lipodystrophy in the rat. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26781–26793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fakas S., Qiu Y., Dixon J. L., Han G. S., Ruggles K. V., Garbarino J., Sturley S. L., Carman G. M. (2011) Phosphatidate phosphatase activity plays key role in protection against fatty acid-induced toxicity in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29074–29085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mitra M. S., Schilling J. D., Wang X., Jay P. Y., Huss J. M., Su X., Finck B. N. (2011) Cardiac lipin 1 expression is regulated by the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ coactivator 1α/estrogen related receptor axis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 51, 120–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Simha V., Garg A. (2009) Inherited lipodystrophies and hypertriglyceridemia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20, 300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cortés V. A., Curtis D. E., Sukumaran S., Shao X., Parameswara V., Rashid S., Smith A. R., Ren J., Esser V., Hammer R. E., Agarwal A. K., Horton J. D., Garg A. (2009) Molecular mechanisms of hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in the AGPAT2-deficient mouse model of congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Cell Metab. 9, 165–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grkovich A., Dennis E. A. (2009) Phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase in the regulation of inflammatory signaling. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 49, 114–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stace C. L., Ktistakis N. T. (2006) Phosphatidic acid- and phosphatidylserine-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 913–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang H., Gao Q., Peng X., Choi S. Y., Sarma K., Ren H., Morris A. J., Frohman M. A. (2011) piRNA-associated germ line nuage formation and spermatogenesis require MitoPLD profusogenic mitochondrial surface lipid signaling. Dev. Cell 20, 376–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]