Abstract

Background

A retrospective study evaluated safety, symptom resolution, patient satisfaction, and medication use 1–2 years after transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and/or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms.

Methods

Thirty-four patients with a confirmed diagnosis of GERD symptoms that were inadequately controlled by antisecretory medications, and who where either dissatisfied with their current therapy or not willing to continue taking medication, underwent TIF using EsophyX at our community-based hospital. Follow-up assessments were completed in 28 patients.

Results

Median age of the study group was 57 (range = 23–77) years, BMI was 25.7 (18.3–36.4) kg/m2, and 50% were female. All patients had documented chronic GERD for a median 5 (1–20) years and refractory symptoms to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Hiatal hernia was present in 75% (21/28) of patients, and 21% (6/28) had erosive esophagitis (LA grade A or B). TIF was performed following a standardized TIF-2 protocol and resulted in reducing hiatal hernia and restoring the natural anatomy of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction (Hill grade I). There were no postoperative complications. At a median 14-months follow-up, 82% (23/28) of patients were off daily PPIs (64% completely off PPIs), and 68% (19/28) were satisfied with their current health condition compared to 4% before TIF. Median GERD Health-Related Quality of Life scores were significantly reduced to 4 (0–25) from 26 (0–45) before TIF (P < 0.001). Heartburn was eliminated in 65% (17/26) and improved by >50% in 86% (24/28) of patients. Regurgitation was eliminated in 80% (16/20) of patients. Atypical LPR symptoms such as hoarseness, coughing, and throat clearing were eliminated in 63% (17/27) of patients as measured by Reflux Symptom Index scores.

Conclusion

Our results in 28 patients confirm the safety and effectiveness of TIF, documenting symptomatic improvement of GERD and LPR symptoms and clinically significant discontinuation of daily PPIs in 82% of patients.

Keywords: Heartburn, EsophyX, Gastroesophageal reflux, Hoarseness, Refractory symptoms, TIF-2

In a landmark article published 20 years ago, Dr. Bernard Dallemagne described the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) and reported his initial experience with the first 12 patients to undergo this procedure [1]. Since then, LNF has become the surgical gold standard for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [2]. However, despite its established long-term efficacy and safety profile, the number of procedures performed in the United States has sharply declined in the past 10 years [3]. This may be attributed to a number of factors, including reports of troublesome long-term side effects associated with LNF, such as gas bloat, dysphagia, and diarrhea [4–7], and the gradual loss of support from the GI community which remains the primary source of referrals. Another cause is surely the perceived efficacy and safety of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), a class of medication that offers healing of esophagitis and satisfactory symptomatic relief in the majority of patients with heartburn. However, several studies have demonstrated that 20–30% of patients on PPIs are not completely satisfied for a variety of reasons [8, 9]. Furthermore, the magnitude of therapeutic gain from PPI treatment for regurgitation is relatively modest [10]. There is also a growing awareness in the peer-reviewed literature and in the public at large about the potential side effects of life-long PPI acid suppression therapy, including osteoporosis and increased risks of fractures [11, 12].

The absence of a completely satisfactory modality of treatment, medical or surgical, has fueled many attempts at finding another alternative. A number of endoluminal devices and approaches to rebuild defective gastroesophageal valves have been developed but have either failed to deliver acceptable outcomes or have been plagued by unacceptable rates of morbidity and even mortalities [13]. In contrast, transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) using the EsophyX® device (EndoGastric Solutions, Redmond, WA) appears to be very promising. The recently published short term data from the United States [14, 15] supports the safety and effectiveness of TIF. Bell and Freeman [14] concluded that this technique should not be considered experimental, a claim supported by a position statement from the American Society of General Surgeons (ASGS) [16]. Additionally, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) fully endorses the appropriate use of endoluminal therapy with proven efficacy in properly selected patients [17]. However, the lack of long-term outcome data remains a barrier to adoption of TIF by the wider surgical community as a reasonable alternative in appropriately selected patients.

Our community-based surgical practice, which specializes in antireflux surgery, started performing the TIF procedure in 2008. The purpose of this single-center retrospective study was to evaluate the longer-term safety and symptom resolution after the TIF procedure in patients with chronic GERD and/or laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms. We analyzed 28 patients available for follow-up with the aim of evaluating symptom elimination, PPI usage, patient satisfaction, and safety. To our knowledge, this study is the first report of any series from the United States exceeding one-year follow-up.

Patients and methods

Patients

Thirty-four consecutive patients underwent TIF using the EsophyX-2 device at our institution between May 2008 and June 2010. Patients undergoing the same procedure at our institution after June 2010 were enrolled in a prospective study (TIF Registry) and were therefore not included. All thirty-four patients were asked to give their permission to gather their baseline, TIF, and follow-up data through a retrospective chart review and were asked to complete a detailed mail-in questionnaire. Follow-up phone calls were made and reminder notices were sent when needed. The data from the 28 patients (82%) who responded were analyzed. Three patients failed to respond, two others could not be reached (having moved out of state), and one patient was terminally ill from ovarian cancer diagnosed in the interval.

Preoperative assessment

Patients considered for surgery had persistent GERD and/or LPR symptoms, which were not controlled or only partially controlled on antisecretory medications, and who were either dissatisfied with their current therapy or unwilling to continue taking medications indefinitely. All potential candidates for antireflux surgery were subjected to our routine diagnostic protocol for surgical fundoplication; a complete history and physical examination, symptom assessment, and other relevant tests. All patients were required to have undergone the following tests: (1) a recent EGD to confirm the diagnosis of GERD and rule out the presence of other esophagogastric pathology; (2) an upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) to better delineate the GE junction anatomy and its measurements; and (3) gastroesophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) to rule out unsuspected esophageal motility abnormalities that may contraindicate surgery. Twenty-four-hour pH-metry (with either the Bravo wireless system or a catheter-based combined pH/impedance monitoring system) was administered whenever the diagnosis of GERD was uncertain, especially in patients with atypical manifestations. The TIF procedure was considered appropriate and was offered to the patients as an alternative to laparoscopic fundoplication when measurement of the axial height of the hiatal hernia did not exceed 2 cm.

TIF technique

All procedures were performed using the EsophyX device and according to the TIF-2 technique described in a white paper (Bell et al. 2009), which we coauthored. Procedures were performed in the operating room with the authors acting as cosurgeons and with the patients under general orotracheal anesthesia.

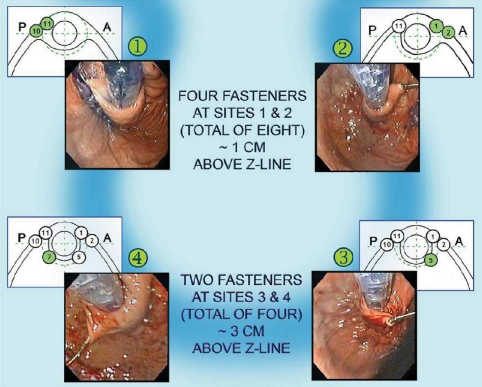

The patient is positioned in a left lateral decubitus and in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position. A preprocedure gastroscopy is performed to assess the dimensions of the hiatus, assign a Hill grade to the tightness of the GE valve, and confirm the absence of retained intragastric contents. The EsophyX-2 device is then gently introduced into the stomach transorally over the flexible endoscope while maintaining full endoscopic visualization of the lumen throughout the insertion phase. The stomach is distended using air insufflation from the gastroscope and CO2 insufflation through the working channel of the scope at a maximum pressure of 12–15 mmHg. A retroflex view is used to observe the tissue mold, elbow, and distal portion of the chassis crossing the GE junction. The back of the mold is then aligned to the lesser curvature. The scope is withdrawn inside the device, allowing for partial closure of the mold at the elbow, then readvanced into the stomach and placed in a retroflex position. The usual orientation landmarks are recognized: the lesser curve, the greater curve, and the anterior and posterior margins of the valve [18]. Three areas (and six locations) are identified for plications: the posterior corner of the valve (the 10 and 11 o’clock locations, to the left of the screen), the anterior corner of the valve (the 1 and 2 o’clock locations, to the right of the screen), and the greater curve (the 5 and 7 o’clock locations at the center of the screen). The deployment of polypropylene H-shaped fastener sets (two fasteners per set) follows the same steps at each location (Fig. 1): the helical retractor is placed into the gastric mucosa within 5 mm of the Z-line, released from the tissue mold, and used to gently retract the tissue caudad. Suction is occasionally applied to the tissue invaginator at this juncture to assist in reducing a small hiatal hernia (if present) and to insure proper positioning of the level of the fundoplication in relation to the Z-line. With gentle tension on the helical retractor, the captured tissue is manipulated into the tissue mold as the mold is closed while desufflating the stomach. The tissue mold and helical retractor are then locked into position. Stylets are then slowly advanced followed by transmural esophagogastric deployment of fasteners over the stylets, one at a time and under direct visualization. We thereby use at least 12 (range = 12–16) plications to create a 240–270° valve by building the anterior and posterior corners of the reconstructed valve and achieving 3–4 cm of vertical length by fixing the gastric fundus to the esophagus at the greater curve. If deemed necessary by visual inspection, we use up to four additional fasteners to reinforce or bolster the fundoplication at the appropriate locations.

Fig. 1.

Modified schematic drawings of the esophagogastric transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) technique with a depiction of fastener placement. A similar drawing was presented by Dr. Barnes and Dr. Hoddinott [15]

Postoperative period

Patients received perioperatively a combination of intravenous analgesics, antiemetics, and anticholinergics. Patients were discharged home the day after surgery, were given a prescription for oral narcotics, and asked to continue PPI therapy for 2 weeks. They were allowed to return to work and drive within 3–5 days. Patients were advised to follow a postoperative diet during the first 6 weeks that consisted of liquids (2 weeks), soft/pureed foods (2 weeks), and a soft low residue diet (2 weeks). Patients were asked to avoid lifting anything heavier than 10–15 lb. during the first 3–5 weeks and not to engage in vigorous sports and other strenuous activities for the first 6 weeks.

Follow-up assessment

All patients were seen back in our office approximately 10 days, 6 weeks, and 3 months after surgery and every 6 months thereafter. Patients were asked to contact us upon the return of any symptom. A request to participate in this retrospective study was mailed to all patients along with detailed, disease-specific questionnaires. Data were collected by reviewing the patients’ charts using paper case report forms and then entered into Excel spreadsheets. All data entered was monitored for accuracy and completeness against the source documents in patient charts. Continuous variables were summarized as means and standard deviations or medians and ranges.

Age, weight, height, gender, previous medical history, use of GERD medication, types of GERD symptoms, and duration of GERD were recorded through review of medical charts. GERD Health-related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL), Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptom Score (GERSS), and Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) are validated questionnaires routinely used in clinical practice for assessing typical and atypical GERD symptoms [13]. All 28 patients completed the GERD-HRQL before TIF prospectively at the time of their physical evaluation. However, all patients were asked to complete preoperative RSI and GERSS questionnaires by recall. The strength of the relationship between the retrospective responses and the prospective GERD-HRQL responses across all domains of the questionnaires was estimated by the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. There was a very strong positive correlation between the regurgitation questions (r = 0.90, P < 0.0001); a strong correlation between the abdominal distension and coughing questions (r = 0.77, r = 0.75, P < 0.001 in both cases); a moderate positive correlation between the heartburn questions (r = 0.68, P < 0.001); and a weak, not statistically significant correlation between the dysphagia questions (r = 0.26, P = 0.19). GERD medication use was recorded as “none” if medication was not taken, “occasionally” if any dose was taken 1–3 days per week, and “daily” if any dose was taken 4–7 days per week. Patient satisfaction with overall health condition was assessed as a part of the GERD-HRQL questionnaire and was recorded as “satisfied,” “neutral,” or “dissatisfied.”

Effectiveness assessment

The primary clinical effectiveness measure was GERD symptom elimination at follow-up based on score normalization. Typical symptoms were evaluated using GERD-HRQL. The GERD-HRQL is a validated disease-specific questionnaire measuring ten items (6 related to heartburn, 2 to dysphagia, 1 to bloating, and 1 to the impact of medication on daily life) on the VAS scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 5 (worst symptoms) [19, 20]. The scores were indicative of rare or eliminated symptoms if none of the abnormal scores at baseline was >2. The same six questions as those evaluating heartburn were used to evaluate regurgitation scores. The GERSS questionnaire was developed and validated to measure both typical and atypical symptoms associated with GERD: heartburn, regurgitation, abdominal distention, dysphagia, and cough [21, 22]. Each of the five symptoms was scored as a product of severity (from 0 = not at all to 3 = severely) and frequency (0 = never to 4 = daily). The item scores varied from 0 to 12 and the total scores from 0 to 60. Patients with controlled reflux symptoms by either medical or surgical therapy are expected to have a total symptom score of <18 [22]. Atypical symptoms were evaluated using RSI scores. The RSI is a nine-item questionnaire that was developed and validated to measure symptoms associated with LPR, such as hoarseness, throat clearing, excess throat mucus, dysphagia, and cough [23]. The scale for each individual item ranges from 0 (no problem) to 5 (severe problem), with a maximum total score of 45 and a normality threshold at ≤13. The follow-up consisted of symptom evaluation by questionnaires. Scores of ≤2 to each question in the GERD-HRQL, GERSS, and RSI questionnaires were indicative of eliminated symptoms. We considered a 50% or more reduction in scores at follow-up as a clinically significant improvement.

Secondary clinical effectiveness measures were PPI discontinuation and incidence of any unanticipated serious and nonserious adverse events, as a measure of safety. The use of PPIs and other GERD medications such as H2RA and antacids was recorded. A discontinuation of daily PPI use, defined as any dose taken ≤3 days per week, was considered clinically significant.

Patients were stratified into two groups based on their primary symptoms and the responses to the GERD-HRQL questionnaire: a “typical” group that included patients whose predominant symptoms were heartburn and regurgitation, and an “atypical” group, which included patients whose predominant symptoms were extraesophageal in nature, representative of LPR symptomatology.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab 15 statistical software (Minitab Inc., State College, PA). Aggregate data, including patient demographics, baseline characteristics, efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction results, were summarized by descriptive statistics. Mean and standard deviation were generally reported for continuous variables. Median and range were reported for data with skewed distribution. P values for changes at follow-up compared to those at baseline were calculated using the Mann–Whitney U test and the paired t test. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare frequencies. Values with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to identify various preoperative predictors of success and failure. Various factors included in the regression model, such as BMI (≤30 vs. >30), typical and atypical symptom scores, and presence of esophagitis, were analyzed.

Results

Patient characteristics at baseline

From the 34 patients treated, 28 patients (82%) gave their permission to access their data and were included in the study. All patients had documented chronic GERD for a median of 5 (range = 1–20) years. Median age was 57 years (range = 23–77), BMI ranged from 18.3 to 36.4 kg/m2, and only one patient was morbidly obese. Esophagitis was present in 21% of patients, and 14% of patients had short-segment Barrett’s esophagus, confirmed by biopsy. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1 and show an even distribution between males and females. The majority of the patients available to follow-up (82%) were younger than 65 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| No. patients | 28 |

| Female | 14 (50%) |

| Age (years) | 57 (23–77) |

| <50 | 12 (43%) |

| 50–65 | 11 (39%) |

| >65 | 5 (18%) |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 25.7 (18.3–36.4) |

| ≥35 kg m−2 | 1 (4%) |

| GERD symptom duration (years) | 5 (1–20) |

| PPI therapy duration (years) | 5 (1–11) |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 4 (14%) |

Values are medians (range) or counts (%)

BMI body mass index, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, PPI proton pump inhibitor

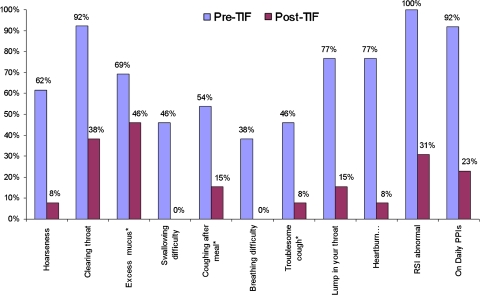

The population of GERD sufferers consisted of patients with predominant typical GERD symptoms (n = 15, 54%) and atypical symptoms (n = 13, 46%). Among patients with predominantly atypical symptoms, 92% (12/13) complained about constantly clearing their throat, 77% (10/13) experienced globus sensation, and 69% (9/13) complained about postnasal drip. However, 10/13 (77%) reported troublesome heartburn and regurgitation as a secondary complaint. All patients in the atypical subgroup had abnormal RSI scores (Fig. 2), with inadequate or partial symptom control despite being on daily (12/13, 92%) or occasional (1/13, 8%) PPI therapy. The majority of the patients were dissatisfied with their current health condition (12/13, 92%).

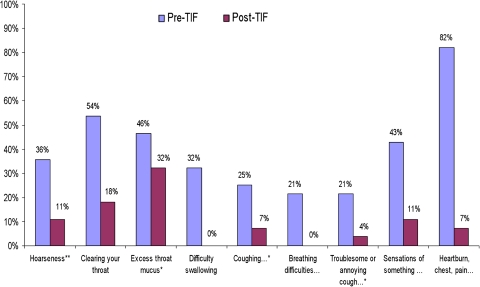

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients (n = 13) with predominant troublesome atypical GERD symptoms as evaluated by RSI questionnaires before TIF on daily PPIs and at the median of 17 (range = 3–29) months follow-up after TIF. P < 0.02 in all cases with significant differences. Associations not statistically significant are indicated by * (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test)

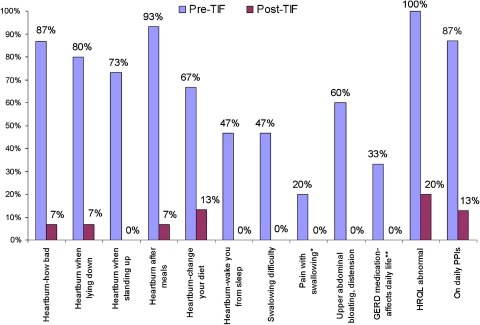

The patients stratified in the typical subgroup suffered from troublesome heartburn and regurgitation. However, 53% of the typical GERD patients reported severe or moderate atypical symptoms as a secondary complaint. Fourteen of 15 (93%) typical GERD patients were dissatisfied with their current health condition despite daily (13/15, 87%) or occasional (2/15, 13%) PPI therapy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients (n = 15) with predominant troublesome typical GERD symptoms as evaluated by GERD-HRQL questionnaires, before TIF on daily PPIs (87%) and at the median of 13 (range = 4–27) months follow-up after TIF. In all cases with significant differences, P < 0.005, except for **, where P = 0.04. Association not statistically significant is indicated by * (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test)

It appears that patients with predominant typical symptoms experienced marginally better clinical outcomes. However, this conclusion did not reach statistical significance.

Procedure and safety outcomes

All TIF procedures were completed successfully and resulted in creating full-thickness esophagogastric fundoplications with a median of a 270° (range = 240–300°) wrap around the esophagus, and a length of 3 (range = 2–4) cm above the Z-line. The average length of time from introduction of the EsophyX device to post-TIF endoscopy was 55 min. As confirmed endoscopically after TIF, the small reducible hiatal hernia (≤2 cm) present in 75% (21/28) of the patients was completely reduced in all 21 patients. Moderately deteriorated gastroesophageal junctions (Hill grades II and III) were typically corrected to Hill grade I after TIF. There were no perioperative complications, and no instances of hospital readmission or blood transfusion related to use of the EsophyX device. All 28 patients were discharged 1 day after surgery.

Clinical outcomes

GERD-HRQL

At a median of 14-months (3–29) follow-up, the median GERD-HRQL scores improved significantly to 4 (0–25) from 26 (0–45) before TIF on PPIs (P < 0.001). Typical GERD symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation were eliminated in 65% (17/26) and 80% (16/20), respectively. GERD-HRQL scores were reduced by more than half in 86% of the patients. Mean changes in the specific components of the GERD-HRQL questionnaire are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean GERD-HRQL scores before TIF on PPIs and after TIF at 14-months follow-up

| Pre-TIF | Post-TIF | |

|---|---|---|

| How bad is your heartburn? | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| Heartburn when lying down? | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| Heartburn when standing up? | 2.8 | 0.5 |

| Heartburn after meals? | 3 | 1 |

| Does heartburn change your diet? | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Does heartburn wake you from sleep? | 2.6 | 0.4 |

| Do you have difficulty swallowing? | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| Do you have pain with swallowing? | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| Do you have bloating and gassy feelings? | 2.7 | 1 |

| If you take GERD medication, does this affect your daily life? | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| How satisfied are you with your present condition?a | 93 | 11 |

aPercentage of dissatisfied patients

GERSS

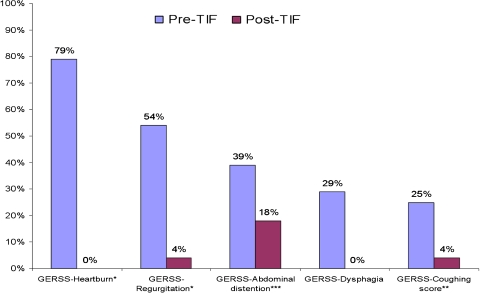

Median GERSS scores were significantly reduced from 24 (9–60) pre-TIF to 3 (0–25) post-TIF and normalized in 61% (17/28) of the patients. The number of patients who complained about troublesome heartburn (0 vs. 79%), regurgitation (4 vs. 54%), abdominal distension (18 vs. 39%), dysphagia (0 vs. 29%), and coughing (4 vs. 25 %) was significantly reduced (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of patients (n = 28) with troublesome typical and atypical GERD symptoms as evaluated by GERSS questionnaires before TIF on PPIs and at the median of 14 (range = 3–29) months follow-up after TIF. *P < 0.005; **P = 0.05; ***P = 0.13 (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test)

RSI

Median RSI scores were significantly reduced from 17 (3–42) pre-TIF on PPIs to 4 (0–22) post-TIF and normalized in 63% (17/23) of the patients. Incidences of troublesome atypical symptoms, evaluated by RSI questionnaires, were significantly reduced across the board (Fig. 5) and supported atypical symptoms resolution.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of patients (n = 28) with troublesome atypical GERD symptoms before TIF on PPIs and at the median of 14 (range = 3–29) months follow-up after TIF. Symptom scores were obtained using RSI questionnaires. In all cases with significant differences, P ≤ 0.02, except for **, where P = 0.055 (approaching significance). Association not statistically significant is indicated by * (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test)

Patient satisfaction

Postoperatively, 11% (3/28) of the patients remained dissatisfied with their current health condition compared to 92% (26/28) before TIF. GERD-specific scores before and after TIF are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

GERD health-related quality of life (GERD-HRQL), reflux symptom index (RSI), gastroesophageal reflux symptom score (GERSS) scores before esophagogastric transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) surgery while on PPIs and at a median 14 (3–29) months after surgery (n = 28)

| Pre-TIF | Post-TIF | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GERD-HRQL scores | |||

| Median (range) | 26 (0–45) | 4 (0–25) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SEM) | 26.4 (5.0) | 6.0 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal [n (%)]a | 26/28 (93%) | 7/28 (25%) | <0.001 |

| Improved by 50% [n (%)]b | 24/28 (86%) | ||

| Normalized [n (%)]c | 17/26 (65%) | ||

| RSI scores | |||

| Median (range) | 17 (3–42) | 4 (0–22) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SEM) | 19.2 (3.6) | 6.1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal [n (%)]a | 27/28 (96%) | 10/28 (36%) | <0.001 |

| Improved by 50% [n (%)]b | 22/28 (79%) | ||

| Normalized [n (%)]d | 17/27 (63%) | ||

| GERSS scores | |||

| Median (range) | 24 (9–60) | 3 (0–25) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SEM) | 26.8 (5.1) | 4.6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal [n (%)]a | 28/28 (100%) | 11/28 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Improved by 50% [n (%)]b | 27/28 (96%) | ||

| Normalized [n (%)]d | 17/28 (61%) | ||

| Regurgitation score | |||

| Median (range) | 16 (0–30) | 0 (0–15) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SEM) | 14.9 (2.8) | 2.8 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal [n (%)]a | 20/28 (71%) | 4/28 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Improved by 50% [n (%)]b | 21/28 (75%) | ||

| Normalized [n (%)]d | 16/20 (80%) | ||

| Satisfaction indexe | |||

| Satisfied [n (%)] | 1/28 (4%) | 19/28 (68%) | <0.001 |

| Neutral [n (%)] | 1/28 (4%) | 6/28 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Dissatisfied [n (%)] | 26/28 (92%) | 3/28 (11%) | <0.001 |

P < 0.05 indicates significant difference

aAbnormal if any individual score >2

bCompared to baseline on PPIs

cNormalized RSI score defined by a total score of ≤13 with each question evaluated as eliminated or rare (score ≤2)

dNormalized if none of the abnormal scores at baseline is >2 at follow-up

eSatisfaction index determined using GERD-HRQL indicates patient satisfaction with current health condition

Postoperative PPI use

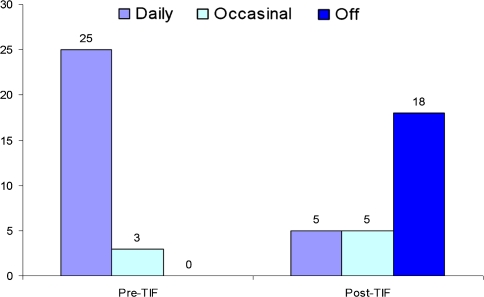

Twenty three of 28 (82%) patients were off daily PPIs after TIF compared to 89% with ineffective symptom control (25/28) on daily PPIs before the TIF procedure. Sixteen of the 25 patients (64%) who were on daily PPI therapy pre-TIF were completely off PPIs post-TIF. Of the three patients (11%) who reported taking PPIs occasionally before TIF, two were completely off PPIs and one remained on occasional PPI therapy. Post-TIF use of PPIs, at a median of 14-months follow-up, was reported by 10 patients as either daily (n = 5, 18%) or occasional (n = 5, 18%) and was completely discontinued by the remaining 18 (64%) patients (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Bars represent number of patients on daily, occasionally, and completely off PPI therapy before and after TIF. Post-TIF, only 18% (5/28) of patients remained on daily PPIs at 14-months follow-up compared to 89% (25/28) before TIF; P < 0.001

Furthermore, of the 17 patients (65%) who experienced heartburn elimination, 12 (71%) were completely off PPIs, 4 were taking PPIs occasionally (23%), and 1 was on daily PPIs (6%). Clinically significant discontinuation of daily PPI use, defined as any dose taken ≤3 days per week, was achieved in 16/17 (94%) patients that experienced resolution of their heartburn.

24-h pH

Ten of 28 patients available for follow-up underwent 24-h pH testing before TIF on PPIs because they could not tolerate discontinuation of medical therapy for testing purposes. Seven of those experienced predominant atypical symptomatology. Only two patients were willing to undergo the same test after TIF. In one case, the DeMeester score was reduced from 29 before TIF to 24.5 after TIF. In another case, the 24-h pH test off PPIs after TIF was normal compared to an abnormal test on PPIs before TIF.

Failures

One patient underwent TIF to LNF conversion 6 months after failed TIF. During the procedure, we found that the fasteners had become dislodged from the fundus of the stomach. The patient’s authentication of habitual overeating led us to conclude that the post-TIF dietary recommendations were not followed and the reconstructed valve was disrupted. This revision was easy to perform and the patient had an uneventful recovery.

Discussion

This study is the culmination of our efforts to critically evaluate the clinical outcomes of the first patients on whom we performed TIF procedures. We became interested in adding TIF to our community-based antireflux surgery practice shortly after the EsophyX device gained FDA clearance, and following publication of the first multicenter data series by Cadiere et al. [24, 25]. His data had been generated using an earlier version of the TIF technique (commonly referred to as TIF-1), which relied primarily on gastrogastric plications below the Z-Line. The data demonstrated encouraging levels of clinical reflux control and a complete absence of any post-fundoplication side effects, and confirmed the exceptional safety profile of the TIF-1, which had been previously established by the phase I single-center trials.

Most patients enrolled in our study were referred to us by gastroenterologists, ENT specialists, and pulmonologists. Generally, patients sought alternative treatments for GERD either because of symptoms refractory to medical therapy or unwillingness to accept the risks associated with lifelong use of PPIs. During office consultations, LNF was discussed and presented as a well-established and effective surgical option in treating both acid and nonacid reflux [26–29]. A significant percentage of patients had large hiatal hernias in excess of 2 cm in axial height, and subsequently underwent LNF. However, a majority of patients with hiatal hernias smaller than 2 cm and who were given a choice between the two procedures ultimately elected to undergo a TIF because of the attractiveness of an incisionless procedure, its safety profile, and the expectation of not having to suffer from any of the known post-fundoplication side effects such as dysphagia and gas bloat [7]. The available clinical effectiveness data from published TIF studies was shared with our patients for full disclosure.

All our patients underwent a TIF-2 procedure [30], a modification of the TIF-1 which entails placement of gastroesophageal plications to create a partial anterior esophagogastric fundoplication above the Z-line. By creating a more robust and more physiologic valve at the gastroesophageal junction, this technique met the expectation of improved reflux control in comparison to TIF-1 in short-term follow-up reports [14, 15].

Regarding clinical effectiveness, a remarkable improvement in both typical and atypical symptoms was noted in our postoperative patient population and reached statistical significance with all three scoring methodologies (GERD-HRQL, RSI, and GERSS). Clinical improvement by a score reduction of more than 50% occurred in 79–96%, while complete normalization was achieved in 61–65% of the cases. The pattern of antisecretory drug use was also dramatically affected in patients undergoing the TIF procedure, with fewer than 20% on daily PPI therapy following surgery. Patient satisfaction was high. Our data therefore suggest that the same level of clinical effectiveness is reproducible and durable with longer follow-up periods. In addition, we are greatly encouraged by the absence of any perioperative complications or debilitating side effects such as gas bloat or new onset of dysphagia in our series. This confirms the experience of others [14, 15] and could represent a favorable shift in the risk-benefit ratio as compared to the more traditional antireflux surgical options, and is one of the most attractive and promising aspects of the TIF procedure in our view.

Reports suggest that the normalization of esophageal acid exposure and a number of reflux episodes after TIF could be achieved in up to 61 and 89% of patients, respectively [14]. We elected to offer the TIF procedure to four patients with short-segment Barrett’s esophagus (≤2 cm) and non-neoplastic changes to alleviate their severe GERD symptoms, improve their quality of life, and ideally stop the advancement of Barrett’s. All four treated patients experienced a remarkable improvement in their symptom scores and medication use after TIF. These patients were placed on a standard Barrett’s surveillance protocol with screening EGDs by their gastroenterologists.

Our attempt to determine the preoperative predictors of success and failure did not reach statistical significance. If we consider the responders only those patients who were completely off PPIs at a median of 14-months follow-up, the patients with severe heartburn (responses 4 or 5 on the first three GERD-HRQL questions) appeared to be at a higher risk of using PPIs at least occasionally after the TIF procedure. However, this conclusion was statistically insignificant. Interestingly, a majority of patients (60%) who were on occasional or daily PPI therapy after TIF had their total GERD-HRQL and RSI scores normalized. Moreover, 90 and 70% had experienced ≥50% improvement in total HRQL and RSI scores, respectively. Although these patients remained on medical therapy, their GERD symptoms were well controlled compared to uncontrolled severe symptoms before TIF. Therefore, we were not surprised with the patients’ refusal to undergo additional testing and an alternative procedure.

Examining the time of symptom reoccurrence after TIF, we observed that nine of ten patients started occasional or daily PPI therapy less than 4 months after the procedure. One patient requested medication 8 months after TIF because of heartburn symptoms and postprandial epigastric pain. In this case, an abdominal ultrasound confirmed our suspicion of cholelithiasis. An endoscopic evaluation of the previously constructed reflux barrier revealed a completely intact, 270° omega-shaped valve in place, without the presence of a hiatal hernia. In all ten cases, the pattern of medication use after initial prescription remained the same over time. Based on these facts, we speculate that the patients off PPIs at 4 months after TIF are likely to remain off PPIs for a longer term.

We owe our strong results to thorough preoperative work-ups and adherence to stringent inclusion criteria. Still, we elected to include patients with dominant or pure LPR symptomatology and proven reflux, even though it has been shown conclusively that this patient population responds less often to conventional surgical treatment [26, 31–33]. However, the comparative effectiveness of surgery compared to medical treatment impacted our decision, supported by our belief in the safety profile of the TIF procedure.

Three patients dissatisfied with their current health condition were reevaluated. One patient had a significant history of metastatic testicular cancer considered in remission. The patient’s preoperative symptoms were mostly laryngopharyngeal, initially improved after TIF, and both EGD and UGI revealed complete reduction of his hiatal hernia after TIF. The second patient admitted lifting heavy luggage 3 weeks after the procedure and as a result experiencing sudden and severe epigastric discomfort for 24 h. The third patient became car sick on his way home (2 h away) the day after surgery and experienced violent retching and vomiting. We suspect that in these latter two cases, the freshly constructed valve was disrupted by violent shearing forces. This emphasizes the importance of refraining from strenuous physical activities and avoidance of vomiting at all costs in the early postoperative period. Five patients who remained on daily PPIs after TIF experienced reduction in their mean GERD-HRQL, GERSS, RSI, and regurgitation scores by 73, 71, 67, and 70%, respectively. This may suggest that TIF achieved a positive impact and relative success in improving the quality of life of these patients despite an unchanged pattern of PPI use.

We strongly believe that the management of chronic refractory GERD requires an interdisciplinary approach. In our community setting, patients seek help when their GERD symptoms become intolerable despite high-dose PPI therapy. Their main therapeutic goals are to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life. In three cases after TIF, we referred the patients stratified to the atypical group to a speech therapist and ENT specialist because we felt that their symptoms were no longer related to GERD.

Although our results support the clinical effectiveness and safety of the TIF procedure, we realize the limitations of this retrospective single-center study, which concerns a small number of patients and which lacks follow-up comparative pH/impedance monitoring data. We believe, however, that it is valuable because it includes all patients treated over a 2-year period, without selection bias, with a relatively long-term median follow-up of 14 months, and with a high positive proportion of responders (more than 80%).

In addition, it should be understood that this study represents our initial learning curve. The EsophyX device itself has seen improvements since we started using it, and the technique underwent modifications. As a consequence of this critical look at our early experience and its results, we feel justified in continuing to offer the TIF as an option to well-selected and appropriate surgical candidates. We are planning to report 2- and 3-year follow-up data that will include endoscopic evaluation of the same patient population at a later time. To address some of the limitations of this study, we are currently enrolling new patients in a prospective multicenter TIF Registry.

Conclusion

Our results confirm the safety profile of TIF and demonstrate its effectiveness in eliminating typical and atypical GERD symptoms at a median of 14-months follow-up. Our study supports the adoption of TIF as an alternative treatment option for selected patients with inadequate symptom control on PPI therapy.

Disclosure

Karim S. Trad, MD, FACS was on the Speakers’ Bureau of EndoGastric Solutions in 2008–2009. Emir Deljkich, Medical Affairs Manager and MSL, is a full-time employee of EndoGastric Solutions, Inc., and was responsible for study management, data analysis, and the preparation of the manuscript. He did not owe any stock at the time of the trial. Daniel G. Turgeon, MD, FACS, has no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1(3):138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos GK, Benetatos N, Tsironis D, Farantos C, Tsimoyiannis EC. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication combined with posterior gastropexy in surgical treatment of GERD. Surg Endosc. 2009;24:1303–1309. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0764-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finks JF, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. The rise and fall of antireflux surgery in the United States. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1698–1701. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funch-Jensen P, Bendixen A, Iversen MG, Kehlet H. Complications and frequency of redo antireflux surgery in Denmark: a nationwide study, 1997–2005. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:627–630. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9705-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahnloser D, Schumacher M, Cavin R, Cosendey B, Petropoulos P. Risk factors for complications of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:43–47. doi: 10.1007/s004640090119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Waring JP. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The impact of operative technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224:51–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundell L. Complications after anti-reflux surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:935–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fass R. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: putative mechanisms of failure. Drugs. 2007;67:1521–1530. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu M, Malladi V, Agha A, Abydayyeh S, Han C, Siepman N, Graham DY. Failures in a proton pump inhibitor therapeutic substitution program: lessons learned. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;2052:2813–2820. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9811-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N. Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(8):1419–1425. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locke GR, III, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., III Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewson EG, Sinclair JW, Dalton CB, Richter JE. Twenty-four hour esophageal pH monitoring: the most useful test for evaluating noncardiac chest pain. Am J Med. 1991;90:576–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madan AK, Ternovits CA, Tichansky DS. Emerging endoluminal therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: adverse events. Am J Surg. 2006;192:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell RC, Freeman KD. Clinical and pH-metric outcomes of transoral esophagogastric fundoplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(6):1975–1984. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1497-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes WE, Hoddinott KM, Mundy S, Williams M. Transoral incisionless fundoplication offers high patient satisfaction and relief of therapy-resistant typical and atypical symptoms of GERD in community practice. Surg Innov. 2011;18(2):119–129. doi: 10.1177/1553350610392067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Society of General Surgeons (2009) ASGS Position Statement on Natural Orifice Surgery and Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication. Available at www.theasgs.org. Accessed 9 Aug 2011

- 17.Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (2009) SAGES Position Statement on Endoluminal Therapies for Gastrointestinal Diseases. Available at www.sages.org/publication/id/ENDOL. Accessed 9 Aug 2011

- 18.Jobe BA, Kahrilas PJ, Vernon AH, Sandone C, Gopal DV, Swanstrom LL, Aye RW, Hill LD, Hunter JG. Endoscopic appraisal of the gastroesophageal valve after antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velanovich V. The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:130–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velanovich V, Vallance SR, Gusz JR, Tapia FV, Harkabus MA. Quality of life scale for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen JC, Parameswaran K, Belda J, Anvari M. Reproducibility, validity, and responsiveness of a disease-specific symptom questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:265–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, Goldsmith C. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: one-year follow-up. Surg Innov. 2006;13:238–249. doi: 10.1177/1553350606296389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI) J Voice. 2002;16(2):274–279. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadiere GB, Buset M, Muls V, Rajan A, Rosch T, Eckardt AJ, Weerts J, Bastens B, Costamagna G, Marchese M, Louis H, Mana F, Sermon F, Gawlicka AK, Daniel MA, Deviere J. Antireflux transoral incisionless fundoplication using EsophyX: 12-month results of a prospective multicenter study. World J Surg. 2008;32:1676–1688. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9594-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadiere GB, Van Sante N, Graves JE, Gawlicka AK, Rajan A. Two-year results of a feasibility study on antireflux transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) using EsophyX. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:957–964. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP, Wood WC. A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 1996;223:673–685. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sala E, Salminen P, Simberg S, Koskenvuo J, Ovaska J. Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease treated with laparoscopic fundoplication. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2397–2404. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker SJ, Holt S, Sanderson CJ, Stoddard CJ. Comparison of Nissen total and Lind partial transabdominal fundoplication in the treatment of gastro-oesophgeal reflux. Br J Surg. 1992;79:410–414. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westcott CJ, Hopkins MB, Bach K, Postma GN, Belafsky PC, Koufman JA. Fundoplication for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jobe BA, O’Rourke RW, McMahon BP, Gravesen F, Lorenzo C, Hunter JG, Bronner M, Kraemer SJ. Transoral endoscopic fundoplication in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: the anatomic and physiologic basis for reconstruction of the esophagogastric junction using a novel device. Ann Surg. 2008;248:69–76. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31817c9630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patti MG, Arcerito M, Tamburini A, Diener U, Feo CV, Safadi B, Fisichella P, Way LW. Effect of laparoscopic fundoplication on gastroesophageal reflux disease-induced respiratory symptoms. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:143–149. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(00)80050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.So JB, Zeitels SM, Rattner DW. Outcomes of atypical symptoms attributed to gastroesophageal reflux treated by laparoscopic fundoplication. Surgery. 1998;124:28–32. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(98)70071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wetscher GJ, Glaser K, Hinder RA, Perdikis G, Klingler P, Bammer T, Wieschemeyer T, Schwab G, Klingler A, Pointner R. Respiratory symptoms in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease following medical therapy and following antireflux surgery. Am J Surg. 1997;174:639–643. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]