Abstract

Functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) is one of the commonest digestive diseases worldwide and leads to significant morbidity and burden on healthcare resource. The putative bio-psycho-social pathophysiological model for FGID underscores the importance of psychological distress in the pathogenesis of FGID. Concomitant psychological disorders, notably anxiety and depressive disorders, are strongly associated with FGID and these psychological co-morbidities correlate with severity of FGID symptoms. Early life adversity such as sexual and physical abuse is more commonly reported in patients with FGID. There is mounting evidence showing that psychological disorders are commonly associated with abnormal central processing of visceral noxious stimuli. The possible causal link between psychological disorders and FGID involves functional abnormalities in various components of the brain-gut axis, which include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system, sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, serotonergic and endocannabinoid systems. Moreover, recent studies have also shown that psychological distress may alter the systemic and gut immunity, which is increasingly recognized as a pathophysiologic feature of FGID. Psychotropic agent, in particular antidepressant, and psychological intervention such as cognitive behavioral therapy and meditation have been reported to be effective for alleviation of gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in FGID patients. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of early detection and management of co-morbid psychological disorders on the long-term clinical outcome and disease course of FGID.

Keywords: Depression, Functional dyspepsia, Generalized anxiety disorder, Irritable bowel syndrome, Psychological disorder

Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) is one of the commonest digestive disease entities, which is characterized by recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms with no identifiable organic pathology. In recent years, a bio-psycho-social pathophysiological model has been implicated for the pathogenesis of FGID, which emphasizes the importance of biological, social, environmental and psychological factors in development of FGID.1 This paper aimed to review the epidemiology, mechanism and psychological intervention of FGIDs.

Epidemiological Association Between Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder and Psychological Disorders

The observations on the association between psychological disorders and FGID used to be considered conflicting, and it was generally regarded as biased observations that were limited to more severe patients seen in referral center setting. An early study conducted in a gastroenterology clinic reported a very high lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder of 34% in newly referred irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients.2 In another study that involved patients with anxiety or depressive disorders, IBS symptoms were found to be associated with severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms. However, patients with depression in remission had no associated IBS symptoms.3 In a study of primary care patients referred for endoscopy, however, there was no difference between patients with functional or organic dyspepsia in the prevalence or risk of mental distress as determined by questionnaire.4 Talley et al5 reported that dyspepsia patients who present for investigation were more likely to be neurotic, anxious, and depressed than non-dyspepsia controls. Using the gold standard diagnostic method with psychiatrist-conducted structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV Axis I Disorders, we have reported that anxiety disorders are diagnosed in 38% of patients with functional dyspepsia compared with 4% in the general population.6 Depression, anxiety, phobia and somatization are strongly correlated with severity of dyspeptic symptoms in a group of patients from tertiary center.7 Somatization is more commonly seen in patients with co-morbid FGID and psychological disorder.8 It has also been observed that IBS patients with psychiatric morbidity are characterized by low rectal distension pain thresholds, high rates of healthcare consultations, interpersonal problems and sexual abuse.9

In recent years, there are mounting evidence showing that similar association between FGIDs and psychological disorders also exists in the community and primary care setting, suggesting a genuine relationship between psychological co-morbidity and FGID rather than biased observations in referral centers. In a community-based study in Sweden, anxiety but not depression is linked to functional dyspepsia with postprandial distress syndrome but not to epigastric pain syndrome.10 In a population-based study in Hong Kong, the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder is significantly higher in subjects reporting IBS symptoms compared to those reporting these symptoms (16.5% vs 3.3%, P < 0.001), and IBS is associated with 6-fold increase in the likelihood of having generalized anxiety disorder.11 Anxiety is an independent factor in determining health care utilization in patients with dyspepsia and IBS.12 In general practice setting, psychological distress is a major determinant of impaired health of patients with dyspepsia.13,14 Similar to patients in referral centers, these primary care patients are also characterized by higher levels of depression and somatization.15

Putative Mechanisms That Are Involved in the Association Between Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder and Psychological Disorders

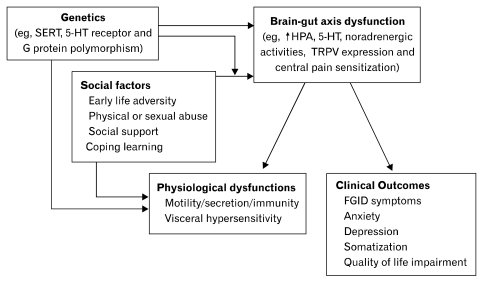

Despite the strong epidemiological association between FGID and psychological disorder, it may not imply a direct causal relationship. Yet, there are cumulating evidence showing that the pathophysiology of FGID involves abnormal processing of visceral nociceptive signals in the brain-gut axis, which leads to visceral hypersensitivity and hyperalgesia.16 Furthermore, FGID patients are also characterized by abnormalities in autonomic, neuroendocrine and immune functions (Figure). And all of these physiological functions are subjected to the influence of psychological distress in the "emotional motor system," which is comprised of the visceral motor cortex, the amygdala, the hypothalamic nuclei and the peri-aqueductal grey. This neural network involves corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) containing neuronal projections that activate both the autonomic nervous system and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. The system is involved in a wide spectrum of physiological activities such as arousal, vigilance and pain modulation. Hyperactivity of the neuroendocrine and visceral perceptual response to physiological (eg, meal) or psychological stimuli may account for the stress-induced flare of bowel symptoms in IBS patients,17,18 and administration of CRF alleviates visceral hyperalgesia and negative affective response to bowel stimulation in IBS patients.19 Increased beta-adrenergic activity is significantly correlated with visceral hypersensitivity and symptoms of hard or lumpy stools in constipation-predominant IBS.20 It has also been reported that anxiety induces gastric sensorimotor dysfunction and postprandial symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia.21

Figure.

Schematic diagram illustrating the pathophysiologic links between functional gastrointestinal disorder and psychiatric disorders. SERT, serotonin reuptake transporter; 5-HT, serotonin; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; TRPV, transient receptor potential vanilloid; FGID, functional gastrointestinal disorder.

Psychological disorders and FGID also share common genetic predispositions particularly the genes that are involved in serotonergic activities. It has been shown that homozygous G-protein beta 3 C825T polymorphism is associated with functional dyspepsia. And this G protein polymorphism has also been linked to depression.22 It has been reported that the polymorphism of serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) genes is associated with the subtypes of IBS.23 Polymorphisms in the promoter for synthesis of SERT influence response to serotonergic medications in depression as well as colonic transit response to alosetron, a serotonin receptor-3 (5-HT3) antagonist, in patients with diarrhea predominant IBS.24 A recent study has also reported that C/C genotype of the c.-42C>T polymorphism in 5-HT3A receptor, compared with T carrier status, is associated with increased anxiety and amygdala responsiveness as well as the severity of IBS symptoms.25

Early life adversity, particularly psychological stress, has been speculated to play an important role of pathogenesis of FGID. It has been shown that self-reported sexual and physical abuse are more common in community and clinic subjects with gastrointestinal symptoms such as IBS and functional dyspepsia.26-28 Other social and environmental factors, such as exposure to war time conditions, infantile and childhood trauma, and social learning of illness behavior are predictors of the IBS in adulthood.29,30 In animal models, it has been shown that early life psychological stress such as neonatal maternal separation results in the development of visceral hyperalgesia and anxiety features.31 There are a number of putative mechanisms that mediates the development of these pathophysiologic changes induced by early life stress. These include hyper-responsiveness of serotonergic system in both central and enteric nervous systems,32 increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic activities,33 increased expression of CRF type 1 receptors and transient receptor ion channel 1 (TRPV1).34,35 The resultant visceral hyperlagesia is likely related to central sensitization at both brain and spinal levels.36,37

In recent years, a positive association between psychological stress and abnormal immunity has also been implicated in the pathophysiologic mechanism of IBS. IBS patients have coexisting hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels.38 Chronic psychological stress leads to maladaptive increase in mucosal permeability and decrease in secretory response of intestinal epithelium to luminal stimuli.39 It has been shown that the change in intestinal mucosal permeability is mediated by CRF.40

Psychotropic Treatment and Psychological Intervention of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorder

There is ample evidence supporting the therapeutic role of psychotropic agents in the treatment of FGID. Most of these trials were conducted in patients with IBS and non-cardiac chest pain. Antidepressant is the most extensively evaluated psychotropic agent for treatment of FGIDs. In the recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review, there is an unequivocal beneficial effect for antidepressants over placebo for improvement of abdominal pain (54% for antidepressants compared to 37% of placebo: relative risk [RR], 1.49; 95% CI, 1.05-2.12; P = 0.03; number needed to treat [NNT] = 5), global assessment (59% for antidepressants compared to 39% of placebo: RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.23-2.00; P < 0.001; NNT = 4) and symptom score (53% of antidepressants compared to 26% of placebo: RR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.32-2.99; P = 0.001; NNT = 4).41 Tricyclic antidepressant has been shown to attenuate stress induced visceral hypersensitivity with suppressed brain activation, suggesting a mechanism of central pain modulating effect that is independent of antidepressive effect.42 In patients with functional dyspepsia, amitriptyline has been shown to be superior to placebo in reducing dyspeptic symptom score especially nausea but there is no effect on drinking capacity and postprandial symptoms in the drink tests.43

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), another class of antidepressant with superior safety and side effect profile, has been shown to reduce pain symptoms in patients with non-cardiac chest pain in addition to IBS.44 Acute administration of citalopram leads to reduction in chemical and mechanical esophageal sensitivity in healthy volunteers.45 SSRI reduces somatization and improves affective response to chronic visceral pain.46,47 These effects are independent of its anti-depressive actions but patients who have concomitant anxiety or depression and somatization tend to have better symptom response to psychotropic agents.47,48 However, its therapeutic benefit in non-depressed IBS patients has not been substantiated.49

The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, or SNRI, is a newer class of antidepressant with faster onset of action in the treatment of depression. However, the use of SNRI in the treatment of FGID is more conflicting. Its use in functional dyspepsia is limited by the lack of efficacy and gastrointestinal upset. It has been shown that venlafaxine is not superior to placebo for treating functional dyspepsia in a randomized controlled trial. Furthermore, there is a short-term worsening of dyspepsia.50 Yet, venlafaxine has been shown to be more effective than placebo in improving pain control and emotional well-being in patients with non-cardiac chest pain in a small randomized controlled trial.51

Apart from antidepressants, other psychotropic agents have also been evaluated for treatment of FGID. For example, the combination formulation of flupentixol and melitracen (Deanxit®) has been shown to be useful for acute symptom control of dyspepsia.52 Trazodone has been shown to be useful for treatment of non-cardiac chest pain due to esophageal hypersensitivity.53 Pregabalin, a new class of drug known as alpha-2-delta ligand, increases distension sensory thresholds to normal levels in IBS patients with rectal hypersensitivity.54

Despite the promising results on the efficacy, none of the above mentioned psychotropic agents have been approved by the regulatory authority such as FDA for the treatment of FGID. Therefore, these agents can only be used in patients with co-morbid psychological disorders or as off-label use with consents obtained from the patients.

In addition to the effectiveness in the management of anxiety and depressive disorders, psychological intervention alone or in combination with psychotropic agent has also been shown to be useful in treatment of patients with FGID. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been most extensively evaluated for treatment of FGID.55 Psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy has also been shown to be effective in alleviating dyspeptic symptoms, and the effects are enduring after cessation of the psychotherapy.56 Combination of sertraline and pain coping skill training has been shown to be more effective than either modality alone in the treatment of non-cardiac chest pain.57 In patients with refractory functional dyspepsia, combination of intensified medical therapy with psychological intervention yields superior long-term-outcomes. Cognitive behavioral therapy gives additional benefits to concomitant anxiety and depression.58 In a recent randomized controlled trial, mindfulness training has a substantial therapeutic effect on bowel symptom severity, health-related quality of life, and reduces distress in IBS patients.59

Conclusion

The strong association between psychological disorders and FGID has been increasingly recognized and there is mounting evidence that supports the causative relationship with biological plausibility. However, the detection and management of concomitant psychological disorder in patients with FGID remains far from satisfactory. Most patients lack the awareness of their psychological symptoms and most primary care clinicians and gastroenterologists lack the vigilance and skills in screening for these common co-morbid conditions. This invariably leads to delayed diagnosis and intervention as well as unnecessary investigations. A good doctor-patient rapport, therapeutic relationship and psychoeducation are essential so that psychological intervention can be implemented with patient's acceptance. Psychotropic agents should be judiciously used in FGID patients with co-morbid psychological conditions as intolerance and poor adherence are common owing to their lack of awareness and hypervigilance to side effects. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of early detection and management of co-morbid psychological disorders on the long-term clinical outcome and disease course of FGID.

Acknowledgements

Some publications by the author cited in this manuscript are supported by a research grant from Department of Medicine & Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lydiard RB, Fossey MD, Marsh W, Ballenger JC. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:229–234. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karling P, Danielsson A, Adolfsson R, Norrback KF. No difference in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome between healthy subjects and patients with recurrent depression in remission. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:896–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pajala M, Heikkinen M, Hintikka J. Mental distress in patients with functional or organic dyspepsia: a comparative study with a sample of the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:277–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Fung LH, Gilligan IJ, McNeil D, Piper DW. Association of anxiety, neuroticism, and depression with dyspepsia of unknown cause. A case-control study. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:886–892. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tse AW, Lai LH, Lee CC, et al. Validation of self-administrated questionnaire for psychiatric disorders in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:52–60. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, et al. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors or somatization? Gut. 2008;57:1666–1673. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.158162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie E, Creed F, Fernandes L, et al. Cluster analysis of symptoms and health seeking behaviour differentiates subgroups of patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:1616–1622. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aro P, Talley NJ, Ronkainen J, et al. Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:94–100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Wu J, Ma YL, Tsang A, Guo WJ, Sung J. Irritable bowel syndrome is strongly associated with generalized anxiety disorder: a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:643–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu WH, Wong WM, Lam CL, et al. Anxiety but not depression determines health care-seeking behaviour in Chinese patients with dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2081–2088. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quartero AO, Post MW, Numans ME, de Melker RA, de Wit NJ. What makes the dyspeptic patient feel ill? A cross sectional survey of functional health status, Helicobacter pylori infection, and psychological distress in dyspeptic patients in general practice. Gut. 1999;45:15–19. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mujakovic S, de Wit NJ, van Marrewijk CJ, et al. Psychopathology is associated with dyspeptic symptom severity in primary care patients with a new episode of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:580–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lembo T, Naliboff B, Munakata J, et al. Symptoms and visceral perception in patients with pain-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1320–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posserud I, Agerforz P, Ekman R, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered visceral perceptual and neuroendocrine response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome during mental stress. Gut. 2004;53:1102–1108. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.017962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickhaus B, Mayer EA, Firooz N, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients show enhanced modulation of visceral perception by auditory stress. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagami Y, Shimada Y, Tayama J, et al. Effect of a corticotropin releasing hormone receptor antagonist on colonic sensory and motor function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:958–964. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JH, Rhee PL, Kim HS, et al. Increased beta-adrenergic sensitivity correlates with visceral hypersensitivity in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1454–1460. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2860-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geeraerts B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holtmann G, Siffert W, Haag S, et al. G-protein beta 3 subunit 825 CC genotype is associated with unexplained (functional) dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:971–979. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pata C, Erdal ME, Derici E, Yazar A, Kanik A, Ulu O. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1780–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camilleri M, Atanasova E, Carlson PJ, et al. Serotonin-transporter polymorphism pharmacogenetics in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:425–432. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilpatrick LA, Labus JS, Coveleskie K, et al. The HTR3A polymorphism c. -42C>T is associated with amygdala responsiveness in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1943–1951. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly J, Baker GA, Rhodes J, Salmon P. The association of sexual and physical abuse with somatization: characteristics of patients presenting with irritable bowel syndrome and non-epileptic attack disorder. Psychol Med. 1999;29:399–406. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klooker TK, Braak B, Painter RC, et al. Exposure to severe wartime conditions in early life is associated with an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2250–2256. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coutinho SV, Plotsky PM, Sablad M, et al. Neonatal maternal separation alters stress-induced responses to viscerosomatic nociceptive stimuli in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G307–G316. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00240.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren TH, Wu J, Yew D, et al. Effects of neonatal maternal separation on neurochemical and sensory response to colonic distension in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G849–G856. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tillisch K, Mayer EA, Labus JS, Stains J, Chang L, Naliboff BD. Sex specific alterations in autonomic function among patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:1396–1401. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.058685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjong YW, Ip SP, Lao L, et al. Neonatal maternal separation elevates thalamic corticotrophin releasing factor type 1 receptor expression response to colonic distension in rat. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2010;31:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Malley D, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Alterations in colonic corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in the maternally separated rat model of irritable bowel syndrome: differential effects of acute psychological and physical stressors. Peptides. 2010;31:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gosselin RD, O'Connor RM, Tramullas M, Julio-Pieper M, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Riluzole normalizes early-life stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity in rats: role of spinal glutamate reuptake mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2418–2425. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung EK, Zhang X, Li Z, Zhang H, Xu H, Bian Z. Neonatal maternal separation enhances central sensitivity to noxious colorectal distention in rat. Brain Res. 2007;1153:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dinan TG, Quigley EM, Ahmed SM, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gut axis dysregulation in irritable bowel syndrome: plasma cytokines as a potential biomarker? Gastroenterology. 2006;130:304–311. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alonso C, Guilarte M, Vicario M, et al. Maladaptive intestinal epithelial responses to life stress may predispose healthy women to gut mucosal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:163–172. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallon C, Yang PC, Keita AV, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) regulates macromolecular permeability via mast cells in normal human colonic biopsies in vitro. Gut. 2008;57:50–58. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.117549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan V, Pickens D, Gautam S, Kessler R, Mertz H. Amitriptyline reduces rectal pain related activation of the anterior cingulate cortex in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:601–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braak B, Klooker TK, Wouters MM, Lei A, van den Wijngaard RM, Boeckxstaens GE. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of amitriptyline on drinking capacity and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:638–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varia I, Logue E, O'Connor C, et al. Randomized trial of sertraline in patients with unexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin. Am Heart J. 2000;140:367–372. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broekaert D, Fischler B, Sifrim D, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on oesophageal hypersensitivity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:365–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabas G, Beaves M, Wang J, Friday P, Mardini H, Arnold G. Paroxetine to treat irritable bowel syndrome not responding to high-fiber diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:914–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Creed F. How do SSRIs help patients with irritable bowel syndrome? Gut. 2006;55:1065–1067. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, et al. Reported sexual abuse predicts impaired functioning but a good response to psychological treatments in patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:490–499. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000163457.32382.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladabaum U, Sharabidze A, Levin TR, et al. Citalopram provides little or no benefit in nondepressed patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Kerkhoven LA, Laheij RJ, Aparicio N, et al. Effect of the antidepressant venlafaxine in functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:746–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee H, Kim JH, Min BH, et al. Efficacy of venlafaxine for symptomatic relief in young adult patients with functional chest pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1504–1512. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hashash JG, bdul-Baki H, Azar C, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized controlled cross-over study of flupenthixol + melitracen in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1148–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Botoman VA. Noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:6–14. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houghton LA, Fell C, Whorwell PJ, Jones I, Sudworth DP, Gale JD. Effect of a second-generation alpha2delta ligand (pregabalin) on visceral sensation in hypersensitive patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2007;56:1218–1225. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.110858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamilton J, Guthrie E, Creed F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychotherapy in patients with chronic functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:661–669. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keefe FJ, Shelby RA, Somers TJ, et al. Effects of coping skills training and sertraline in patients with non-cardiac chest pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2011;152:730–741. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haag S, Senf W, Tagay S, et al. Is there a benefit from intensified medical and psychological interventions in patients with functional dyspepsia not responding to conventional therapy? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:973–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaylord SA, Palsson OS, Garland EL, et al. Mindfulness training reduces the severity of irritable bowel syndrome in women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1678–1688. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]